Abstract

Tourism organisations are particularly exposed to crises and disasters. Effective crisis management requires collaboration among diverse stakeholders, including local businesses, public authorities, emergency units, and actors in source markets such as tour operators and government agencies. However, communication barriers and fragmented responsibilities hinder cooperation. This study investigates stakeholder collaboration in destination tourism crisis management by identifying key actors, analysing their interactions, and exploring ways to enhance collaboration using stakeholder theory. Findings highlight the need for cross-border collaboration, emphasising the role of tourism associations as coordinating entities. The study suggests that proactive inter-agency cooperation, trust-building, and structured crisis planning improve resilience. Theoretical and practical implications underscore the necessity for clear leadership and structured communication networks to strengthen crisis response in tourism destinations.

1 Introduction

The scientific community agrees on the particular vulnerability of tourism organisations to crises and disasters (e. g. Goktepe et al. 2024): (1) The tourism sector is mostly affected by externally induced, unpredictable and inevitable crises (e. g. Xu and Grunewald 2009). These include natural disasters such as tropical storms, earthquakes, forest fires or flooding caused by extreme weather events or man-made crises such as terrorist threats or epidemics (e. g. Filimonau and Coteau 2020). (2) It is essential to acknowledge the customers of tourism organisations and destinations – namely, the tourists – who constitute a vulnerable group in unfamiliar locations and consequently require special assistance during crises (e. g. Berbekova, Uysal, and Assaf 2021). (3) The tourism industry is characterised by a fragmented small-scale structure, comprising numerous stakeholders who contribute to the tourism product and may be geographically widely distributed (e. g. Pavlovich 2003). Conversely, tourism destinations are complex and dynamic systems, encompassing multiple stakeholders with heterogeneous structures and objectives which pose significant challenges for effective management (e. g. Pyke et al. 2018).

The obvious actors in a destination may be hotels, airlines, destination management companies (DMC, also called incoming agencies), emergency units and public authorities on state, federal and local level. But does stakeholder collaboration end here, in the destination’s ‘front yard’? Shouldn’t actors in the source markets also be considered? As intermediaries between destination and tourists and considering their economic impact, they play a determining role in the destination (e. g. Becken et al. 2014). Other important actors in the source markets include public authorities, particularly the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, which oversees travel and security advisories for destinations, and diplomatic missions within the destination, responsible for assisting their nationals during emergencies.

Effective collaboration and coordination among the numerous stakeholders within a destination remains a persistent challenge in daily operations (e. g. Zemla 2016). Hierarchical and fragmented structures in both the public and private sectors complicate communication (e. g. Morakabati, Page, and Fletcher 2017). During crises, stakeholder pressure intensifies, making collaboration crucial for the survival of both the organisations and the destination (e. g. Mistilis and Sheldon 2006). While scholars recognise the gap between stakeholders (e. g. van der Zee and Vanneste 2015), understanding their perspectives and strategies to bridge this divide – particularly between public and private actors in tourism crisis management – remains an area for further research (e. g. Nguyen, Imamura, and Iuchi 2017).

This article therefore aims to improve the collaboration of stakeholders in tourism destination crisis management by shedding light on their level of collaboration. The following research questions are designed to support this objective:

Who are the stakeholders influencing the outcome of a crisis in a destination and with which parties do they interact during a crisis?

What impact do they have on the destination during a crisis?

How can stakeholder theory improve the collaboration between designated stakeholders in tourism destination crisis management?

The subsequent literature review in Section 2 provides a brief theoretical introduction to crisis management in tourism, stakeholder collaboration and theories. The methodology Section 3 describes the four research steps conducted, the results of which are presented in Section 4 along the lines of the research questions. Section 5 compares the results with scientific literature. Section 6 addresses the study’s limitations and future research directions before concluding with theoretical and practical implications to improve stakeholder collaboration in tourism destination management.

2 Literature review

2.1 Crisis management in tourism destinations and its actors

Crises and disasters have been defined extensively but without consensus in academic literature. Faulkner (2001) distinguishes both terms by their origin stating that crises are inflicted internally while disasters are externally induced. For this study, one common definition is used encompassing both crises and disasters, considering the destination as a system: A crisis is a “disruption that physically affects a system as a whole and threatens its basic assumptions, its subjective sense of self, its existential core” (Pauchant and Mitroff 1992, 15). Crisis management encompasses the set of tasks that enable an organisation to effectively navigate a crisis, including mitigation, preparedness, response, and recovery (Fink 1986). Research in tourism crisis management gained significant momentum following the terrorist attacks of 9/11 in the United States in 2001 (e. g. Wut, Xu, and Wong 2021). Among the numerous crisis management models elaborated in tourism, crisis management of destinations is the number one contextual focus (Khardani and Schmude 2024).

Destinations have been defined, described and researched extensively in the tourism literature. As defined by Becken (2013), they are geographical areas where tourism significantly contributes to the economy. From an economic perspective, a tourism destination integrates essential elements for a tourist’s experience, including a diverse range of attractions – such as natural landscapes, climate, and cultural sites – along with necessary infrastructure like transport, accommodations, food and recreational facilities (Buhalis 2000). The product is either part of a package vacation sold by outbound tour operators and (online) travel agencies, or it is booked independently by the tourists.

Tourism destinations consist of a heterogeneous composition of public (e. g. governments), private (tourism industry, hospitality, retail, transportation) or hybrid (tourism associations) actors who are engaged in tourism either directly or indirectly (e. g. Hartman, Wielenga, and Heslinga 2020). These stakeholders differ from other networks due to their role as productive coalitions within a highly fragmented supply structure, necessitating collaboration (e. g. Pavlovich 2003) as they rely on mutual interdependence (e. g. Berbekova, Uysal, and Assaf 2021). According to Zemla (2016, 9) “this spatial embeddedness changes radically the rules of cooperation”, which applies particularly to crisis events. Adding to the complexity, tourists actively engage with their host destination during their visit, making them an additional stakeholder group within the destination (e. g. van der Zee and Vanneste 2015). It is therefore crucial to consider both the tourists' host destination and the source market, including tourism service providers and local authorities. Tour operators should be key partners, as they play a significant role in the destination’s economic development, before, during and after a crisis (e. g. Becken 2013). With their package holidays as a popular form of travel in Europe, they exert significant influence on destinations which grants them substantial bargaining power regarding rates and allotment contracts, especially in traditional sun-and-beach destinations such as Spain, Greece, Turkey, Egypt or the Dominican Republic (Picazo and Moreno-Gil 2018). Large, vertically integrated tour operators, controlling transport connections and their own tourism services, can shape and even close destinations to international tourists, creating a high dependency of destinations.

2.2 Stakeholder collaboration

Cooperation and collaboration are usually used interchangeably. While cooperation refers to “working together towards the same purpose” (Oxford English Dictionary 2023), collaboration, as defined by Jamal and Getz (1995) involves joint decision-making among stakeholders to address destination-related issues such as crises.

The role of stakeholders in strategic management was first discussed by Freeman (1984, 46), who defines stakeholders as “any group or individual who can affect or is affected by the achievement of the organization’s objectives”. While traditionally linked to organisations, the concept also applies to destinations, which share similar characteristics but are often more complex, as described previously. Stakeholder collaboration has been widely studied across disciplines (e. g. Phillips, Freeman, and Wicks 2003), originating in business administration and later expanding to corporate social responsibility (e. g. Clarkson 1995) and marketing (e. g. Podnar and Jancic 2006). Scholars started to integrate stakeholder theory in tourism management in the early twentieth century (e. g. van der Zee and Vanneste 2015). There, it has been further applied to sustainable tourism (e. g. McComb, Boyd, and Boluk 2017), community-based tourism planning (e. g. Jamal and Getz 1995) and tourism crisis and disaster management (e. g. Jiang and Ritchie 2017).

The core of stakeholder theory tries to group the identified stakeholders into certain categories, so that the organisation can relate to and deal with them effectively (e. g. Freeman 1984). It can serve as an instrument to understanding the perceptions and roles of tourism stakeholders in destinations (e. g. Beritelli 2011). Stakeholder crisis management aims to elaborate instruments for management of the diverse groups in the destination by identifying the stakeholders, analysing their impact and developing an appropriate disaster mitigation plan (e. g. Morakabati, Page, and Fletcher 2017). Stakeholders who are aware of the destination’s needs and who collaborate before, during and after a crisis are key for successful crisis handling in the destination (e. g. Morakabati, Page, and Fletcher 2017).

2.3 Stakeholder theories

As discussed in the previous subsection, identifying and categorising stakeholders is a prerequisite to dealing successfully with them. In the following, the approaches applied to this study are briefly described. Stakeholders can be systematically classified, based on their level of influence, into primary and secondary stakeholders. For Clarkson (1995), an organisation’s survival depends on the participation of its primary stakeholders such as shareholders, employees, customers, suppliers or investors. Secondary stakeholders do not engage directly with the organisation but can influence or be affected by it. While not essential for its survival, they may still be damaging. Examples are the media or special interest groups causing a so-called ‘shitstorm’ which can harm the organisation’s reputation. A further distinction can be made according to the type of stakeholders, allocating them to institutions, businesses or individuals (Beritelli 2011). Podnar and Jancic (2006) introduce a three-level model of exchange and communication with stakeholders. In this model, an organisation maintains inevitable relationships with core stakeholders (shareholders, employees, customers, suppliers, competitors), who hold the most power and are critical to its operations. Necessary relationships exist with entities such as trade organisations, unions, media, financial institutions, and the local community, which have moderate but notable influence. The largest group, including foundations, employees' families, political parties, pressure groups, and civil initiatives, holds a desirable but limited degree of power over the organisation. The most detailed stakeholder typology is conducted by Mitchell, Agle, and Wood (1997) and applied by several researchers (e. g. Mojtahedi and Oo 2017; Nogueira and Pinho 2015). Through an extensive literature review, Mitchell, Agle, and Wood (1997) combine the central attributes of power, legitimacy, and urgency with the stakeholders’ attitude towards the organisation (latent, expectant, definitive) and their salience (low, moderate, high). The result are seven types of stakeholders, namely dormant, discretionary, demanding, dominant, dangerous, and definitive. They are presented in Section 3, Table 1 and are discussed in the context of this research in Sections 4.4 and 5.3.

3 Methodology

A mixed-methods approach was used, combining several qualitative methods to generate knowledge and deepen understanding of the research problem.

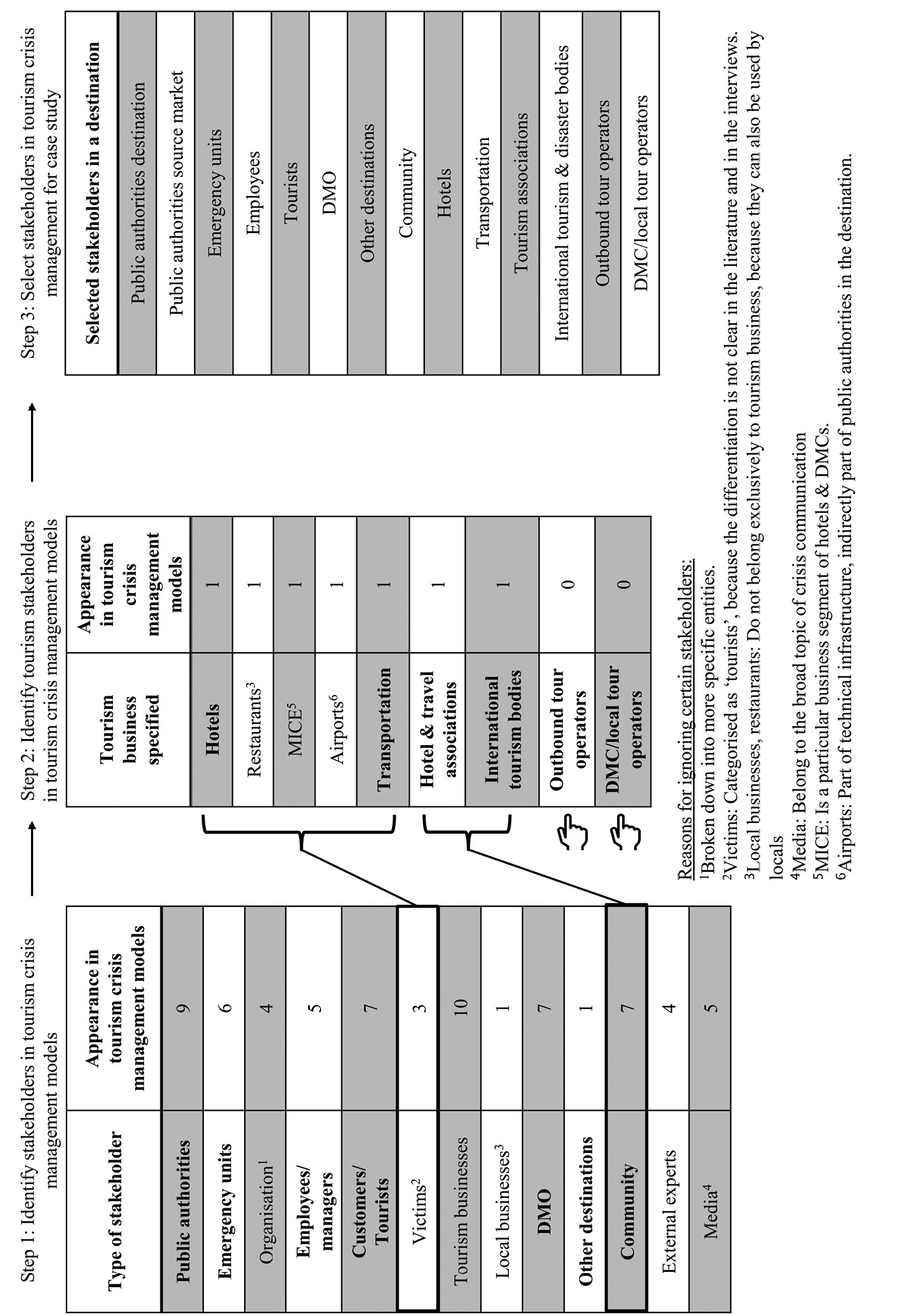

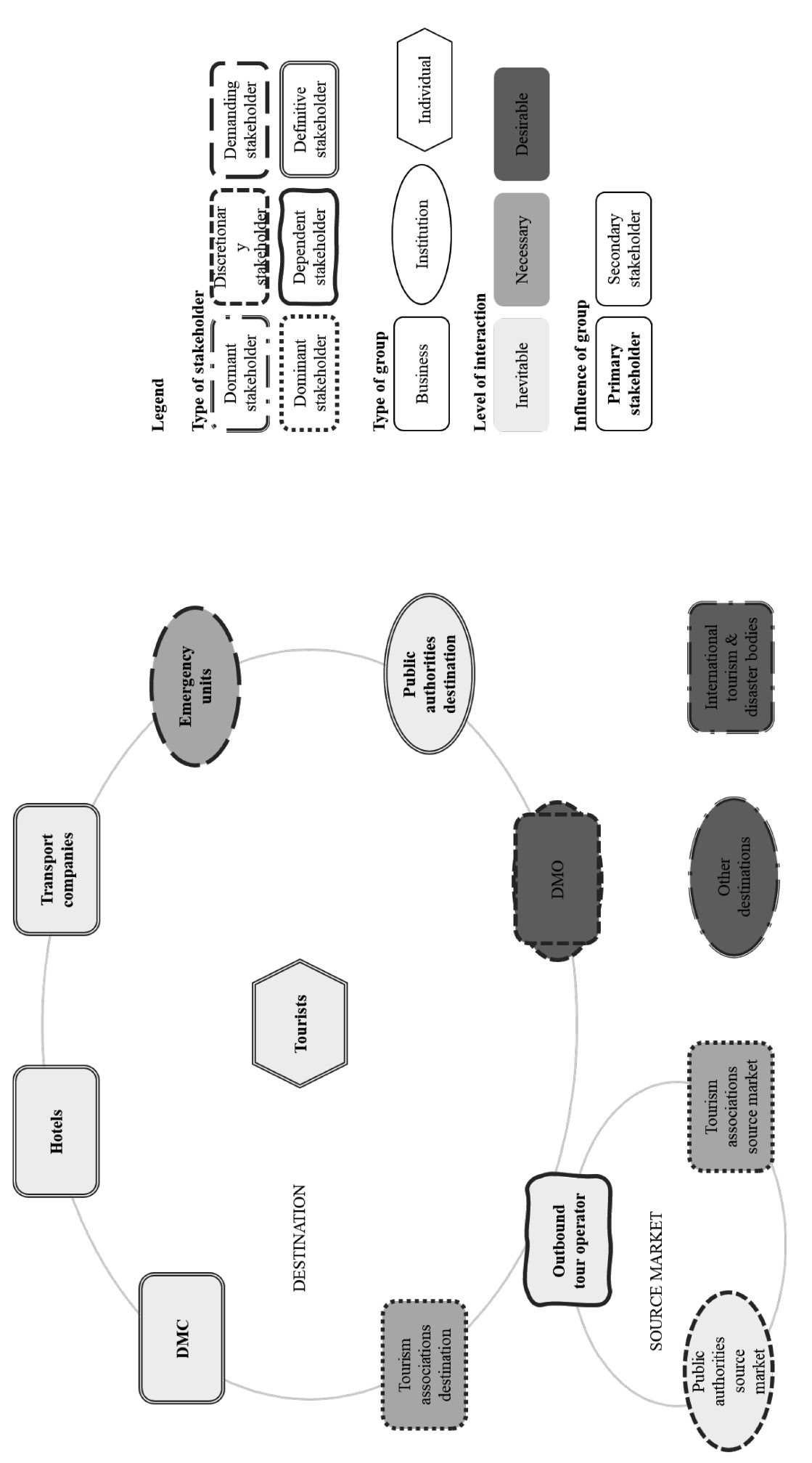

A pre-study was conducted to identify the stakeholders (Research Step 1, Figure 1) in a tourism destination during a crisis by examining 15 tourism crisis management models between 1999 and 2019 via a systematic literature review (Khardani and Schmude 2024). Figure 1 shows the identification and selection process of examined stakeholders in this article: First, all stakeholders mentioned in the tourism crisis management models in the study above were listed. Then, tourism stakeholders were further refined based on the models of Stafford, Yu, and Kobina Armoo (2002) and Paraskevas and Arendell (2007). Lastly, stakeholders were eliminated and refined.

Desk research conducting an extensive literature review on stakeholder theories suitable for the context of destinations is presented in Section 2.3 and applied to the selected stakeholders (Research Step 2, Table 1).

To validate the selected stakeholders and their attributes, a qualitative multiple case study was conducted using semi-structured explorative interviews (Research Step 3, Tables 2 and 3). Case studies go beyond quantitative data by exploring the reasons and processes behind organisational, individual, or institutional responses to specific conditions. They are a suitable method for in-depth investigation within real-world contexts, supported by prior theoretical propositions (e. g. Yin 2018). The Caribbean is ranked as the most tourism-dependent region globally. Consequently, tourism is a valuable source of income in this region (e. g. Mackay and Spencer 2017). Given the Caribbean’s vulnerability to natural disasters, enhancing disaster resilience is essential for the region’s tourism industry (e. g. Filimonau and Coteau 2020) to effectively address the substantial challenges faced by its island destinations (e. g. Becken et al. 2014). Therefore, the Dominican Republic and the Commonwealth of Dominica were chosen for the multiple-case study (e. g. Creswell 2013) based on their afore-mentioned similarities as well as their decisive difference in the type of tourism as per Table 2.

Research Step 1: Identification and selection process of stakeholders to be examined based on Khardani and Schmude (2024).

Research Step 2: Form sheet with applied stakeholder theories & stakeholders in tourism destination crisis management based on Clarkson 1985, 106–107; Beritelli 2011, 613; Podnar and Jancic 2006, 301; Mitchell, Agle, and Wood 1997, 874.

|

|

Influence of group |

Type of group |

Level of interaction |

Core |

Dormant |

Discretionary |

Demanding |

Dominant |

Dangerous |

Dependent |

Definitive |

|

|

Primary stakeholder |

Institution |

Inevitable |

Attribute |

Power |

Legitimacy |

Urgency |

Power + legitimacy |

Urgency + power |

Legitimacy + urgency |

Power + legitimacy + urgency |

|

|

Secondary stakeholder |

Business |

Necessary |

Attitude |

Latent |

Latent |

Latent |

Expectant |

Expectant |

Expectant |

Definitive |

|

|

|

Individual |

Desirable |

Salience |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Moderate |

Moderate |

Moderate |

High |

|

Public authorities source market |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Tourism associations soure market |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Outbound tour operators |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Public authorities destination |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Tourism associations destination |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Hotels |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

DMCs |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Transportation companies |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

DMOs |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Emergency units |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

International tourism & disaster bodies |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Other destinations |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Employees |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Tourists |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Community |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Research Step 3: Selected characteristics of multiple case study areas Dominican Republic and Commonwealth of Dominica.

|

|

Dominican Republic |

Commonwealth of Dominica |

|

Touristic map |

Figure 2: Touristic map of Dominican Republic (Asonahores 2024, 2)

|

Figure 3: Touristic map of Dominica (Discover Dominica Authority, n. d., 6)

|

|

Location |

Eastern part of Hispaniola, (Western part Republic of Haiti) |

Lesser Antilles |

|

Size in km2 |

49 967 |

712 |

|

Inhabitants |

10 500 000 |

68 000 |

|

International tourist arrivals in 2023 |

10 317 612 with 22 % cruise ship passengers (Departamento de Cuentas Nacionales y Estadísticas Económicas de la República Dominicana, 2024, 19, 25) |

401 297 with 78 % cruise ship passengers (Eastern Caribbean Central Bank & Eastern Caribbean Currency Union (ECCU) Central Statistical Offices, 2025) |

|

Type of tourism |

Classical sun & beach package holidays, cruise visitors |

Cruise visitors, foreign independent travellers (FITs) |

A semi-structured interview format was selected to examine the complex relationships and dependencies among stakeholders during Hurricane Maria in September 2017. When participants had not personally managed this crisis, they referred to similar hurricanes or the Covid-19 pandemic. This approach aligns with Patton (2015), who views interviewees as key to understanding system dynamics. All participants were required to hold a management position during the referenced crisis and have prior crisis management experience, following Creswell’s (2013) emphasis on selecting participants based on expertise. A total of 26 interviews with 28 stakeholders from Dominica (8), the Dominican Republic (14), and Germany (4) were conducted by a single interviewer between July 2023 and April 2024 via recorded Zoom calls (granted by the interviewees) in English, Spanish, and German. The sample size follows the concept of data saturation in qualitative research (e. g. Boddy 2016), as interviews revealed no new insights from additional stakeholders within the same group. Table 3 provides the labelling and details of the interview partners. The labelling ‘InterviewnumberStakeholdergroup_country’ provides direct insight into the interviewees’ stakeholder group and their organisations’ seat. The interviews began with a narrative icebreaker, followed by fifteen guiding questions, and concluded with an open-ended question. Topics included (1) organisational actions before, during, and after the crisis, (2) stakeholder involvement and extent of engagement, (3) information flow and instructions, (4) strengths and weaknesses in stakeholder collaboration, and (5) key factors for effective crisis management. Transcriptions and translations from Spanish and German to English were realised with Whisper AI Open Source. The interviews were checked for spelling and correct technical terms and anonymised.

Research Step 3: Interview partners with organisations’ seat and type and interviewees’ position and nationality.

Academic expert (n=1) + airline (n=1) + DMO (n=1) + tourism association (n=1) + public authorities destination (n=2) + tour operator (n=4) + DMC (n=8) + hotel (n=8) = n(I)=26.

|

Interview label |

Organisation |

Interviewee |

Contact based on |

||

|

Seat |

Type |

Position |

Nationality |

||

|

1TA_DR |

Dominican Republic (DR) |

Tourism association (TA) |

Director |

Dominican Republic |

Recommended by academic expert |

|

2DMO_D |

Dominica (D) |

DMO |

Director |

Dominica |

Researcher’s academic network |

|

3TO_GE |

Germany (GE) |

Tour operator (TO) |

Head of |

Germany |

Excel list sent by e-mail from DMO Discover Dominica Authority in 2023 |

|

4H_D |

Dominica (D) |

Hotel (H) |

Director |

Dominica |

DMO homepage Discover Dominica (2024) |

|

5DMC_DR |

Dominican Republic (DR) |

DMC |

Operations Manager |

Dominican Republic |

Excel list from OPETUR sent via WhatsApp in 2024 |

|

6DMC-H_D |

Dominica (D) |

DMC, Hotel (H) |

Owner |

Dominica |

DMO homepage Discover Dominica (2024) |

|

7H_D |

Dominica (D) |

Hotel (H) |

Owner |

Netherlands |

DMO homepage Discover Dominica (2024) |

|

8H_D |

Dominica (D) |

Hotel (H) |

Head of |

Dominica |

DMO homepage Discover Dominica (2024) |

|

9DMC_D |

Dominica (D) |

DMC |

Owner |

Dominica |

DMO homepage Discover Dominica (2024) |

|

10H_DR |

Dominican Republic (DR) |

Hotel (H) |

Director |

Dominica |

Recommended by academic expert |

|

11DMC_DR |

Dominican Republic (DR) |

DMC |

Director |

Dominica |

Excel list from OPETUR sent via WhatsApp in 2024 |

|

12H_DR |

Dominican Republic (DR) |

Hotel (H) |

General Manager |

Dominican Republic |

Researcher’s academic network |

|

13DMC_DR |

Dominican Republic (DR) |

DMC |

Operations Manager |

Dominican Republic |

Researcher’s professional network |

|

14A_DR |

Dominican Republic (DR) |

Airline (A) |

Director |

France |

Researcher’s professional network |

|

15AE_DR |

Dominican Republic (DR) |

Academic expert (AE) |

Lecturer, researcher |

Dominican Republic |

Researcher’s professional network |

|

16H_DR |

Dominican Republic (DR) |

Hotel (A) |

General Manager |

Dominican Republic |

Researcher’s professional network |

|

17TO_GE |

Germany (GE) |

Tour operator (TO) |

Head of |

Germany |

Excel list sent by e-mail from DMO Discover Dominica Authority in 2023 |

|

18H_D |

Dominica (D) |

Hotel (H) |

Owner |

Swizerland |

DMO homepage Discover Dominica (2024) |

|

19TO_GE |

Germany (GE) |

Tour operator (TO) |

Director |

Germany |

Researcher’s professional network |

|

20TO_GE |

Germany (GE) |

Tour operator (TO) |

Destination Manager |

Germany |

Researcher’s professional network |

|

21PA_DR |

Dominican Republic (DR) |

Public authority government level (PA) |

Former vice Minister of Tourism |

Dominican Republic |

Recommended by academic expert |

|

22PA_DR |

Dominican Republic (DR) |

Public authority local level (PA) |

Tourism Specialist & Coordinator |

Dominican Republic |

Recommended by academic expert |

|

23DMC_DR |

Dominican Republic (DR) |

DMC |

General Manager |

Dominican Republic |

Excel list from OPETUR sent via WhatsApp in 2024 |

|

24H_DR |

Dominican Republic (DR) |

Hotel (H) |

General Manager |

Spain |

Researcher’s professional network |

|

25DMC_D |

Dominica (D) |

DMC |

Owner |

Dominica |

DMO homepage Discover Dominica (2024) |

|

26DMC_DR |

Dominican Republic (DR) |

DMC |

Incoming Director & Key Account Manager |

Bulgaria & Germany |

Excel list from OPETUR sent via WhatsApp in 2024 |

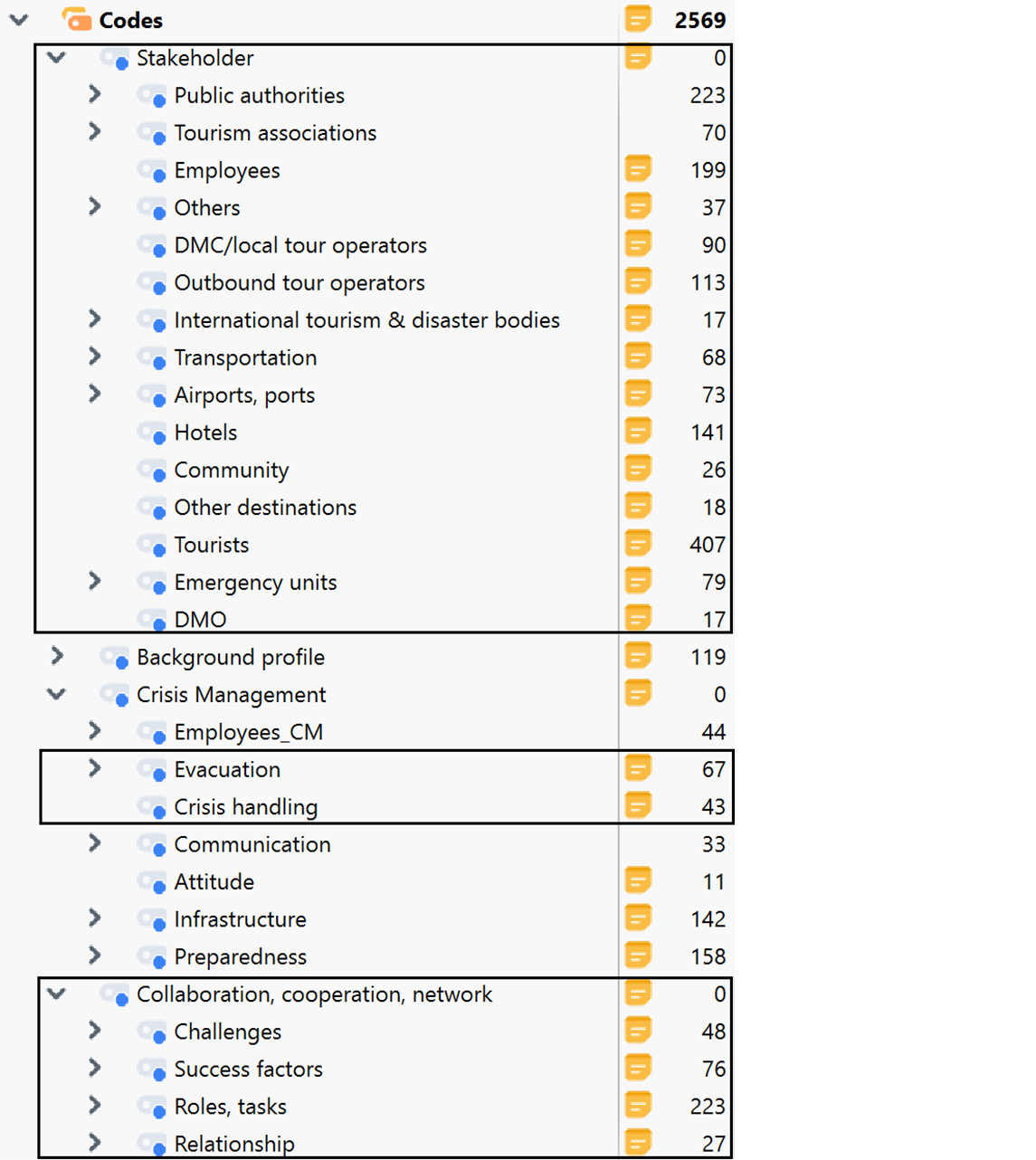

For the data analysis, a structuring qualitative content analysis with MAXQDA 24 (Research Step 4, Figure 4) was chosen (Kuckartz and Rädiker 2023) and applied as follows:

Concept-driven, deductive coding by category formation using the guiding interview questions and the stakeholder categorisation.

The codes were checked for clarity and alignment to the code descriptions, sorted, merged and subcodes were introduced by inductive coding.

Following the research questions as guiding instrument, the codes were sorted and merged a third time.

Figure 4 shows the theme- and stakeholder-based code structure. For this article, the highlighted codes are analysed.

Research Step 4: Coding scheme in MAXQDA 24

4 Results

4.1 Who are the stakeholders influencing the outcome of a crisis in a destination and with which parties do they interact during a crisis?

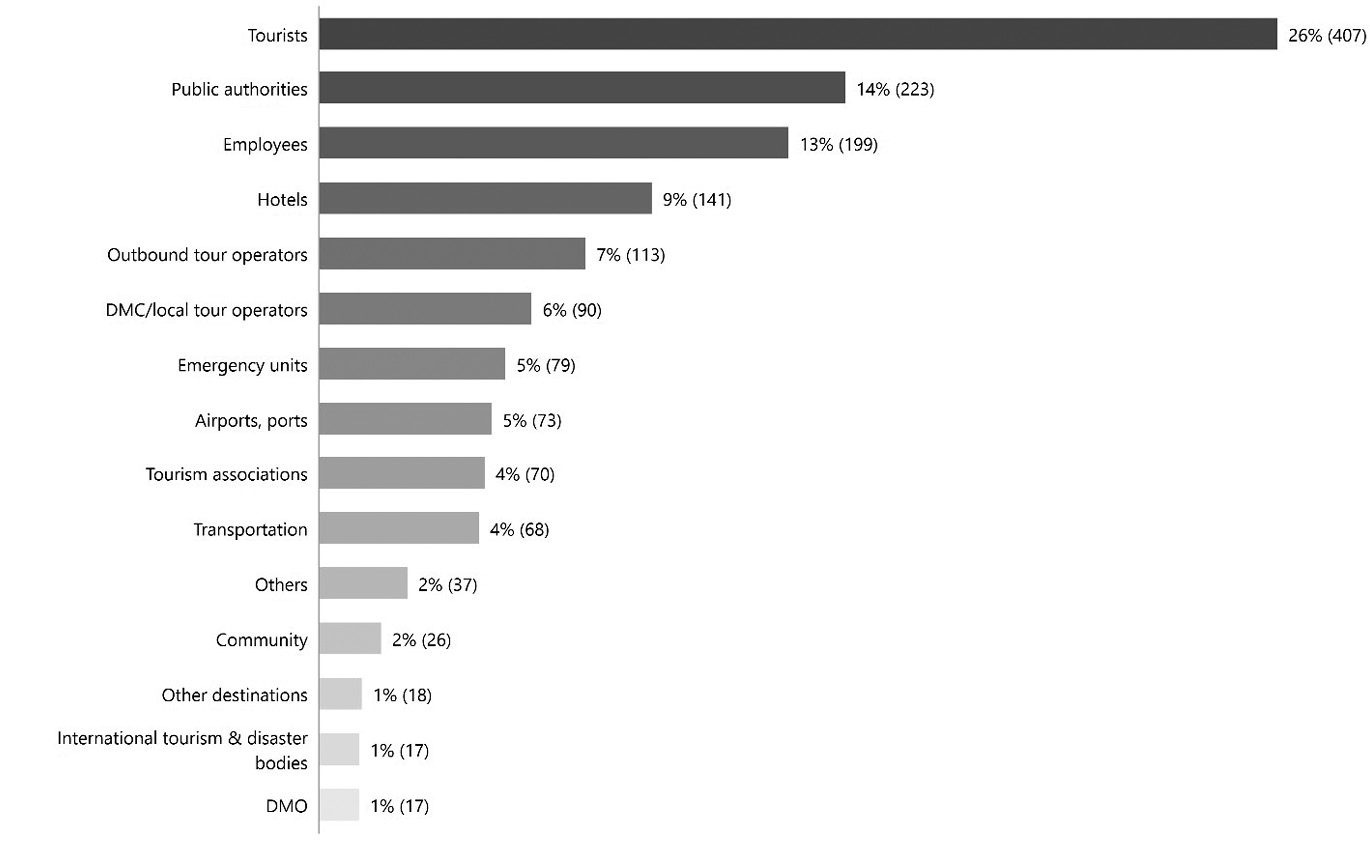

The stakeholders mentioned by the interviewees were coded using MAXQDA 24 text search and auto code. All codes were manually verified to ensure stakeholders were referenced exclusively in crisis-related contexts. To prevent duplicate counts, stakeholders mentioned multiple times within a single phrase were coded only once. Additionally, stakeholders belonging to the same group as the interviewees were coded only when referring to competitors. With fourteen actors (plus ‘others’), Figure 5 confirms the complexity of the destination’s stakeholder structure as discussed in Section 2.1. Tourists constitute the largest stakeholder group, with a value nearly double that of public authorities, the second-largest group. They are followed by the organisations’ employees and the two tourism suppliers, hotels, and outbound tour operators. Although Figures 5 and 6 show that employees are of significant importance to all stakeholders, they are not further considered for the research questions RQ2 and RQ3, because there, the focus lies on the connections of external actors inside and outside of the destination during a crisis.

Stakeholders in tourism destination crisis management: Subcode statistics of stakeholders in percent and absolute numbers (n=1578).

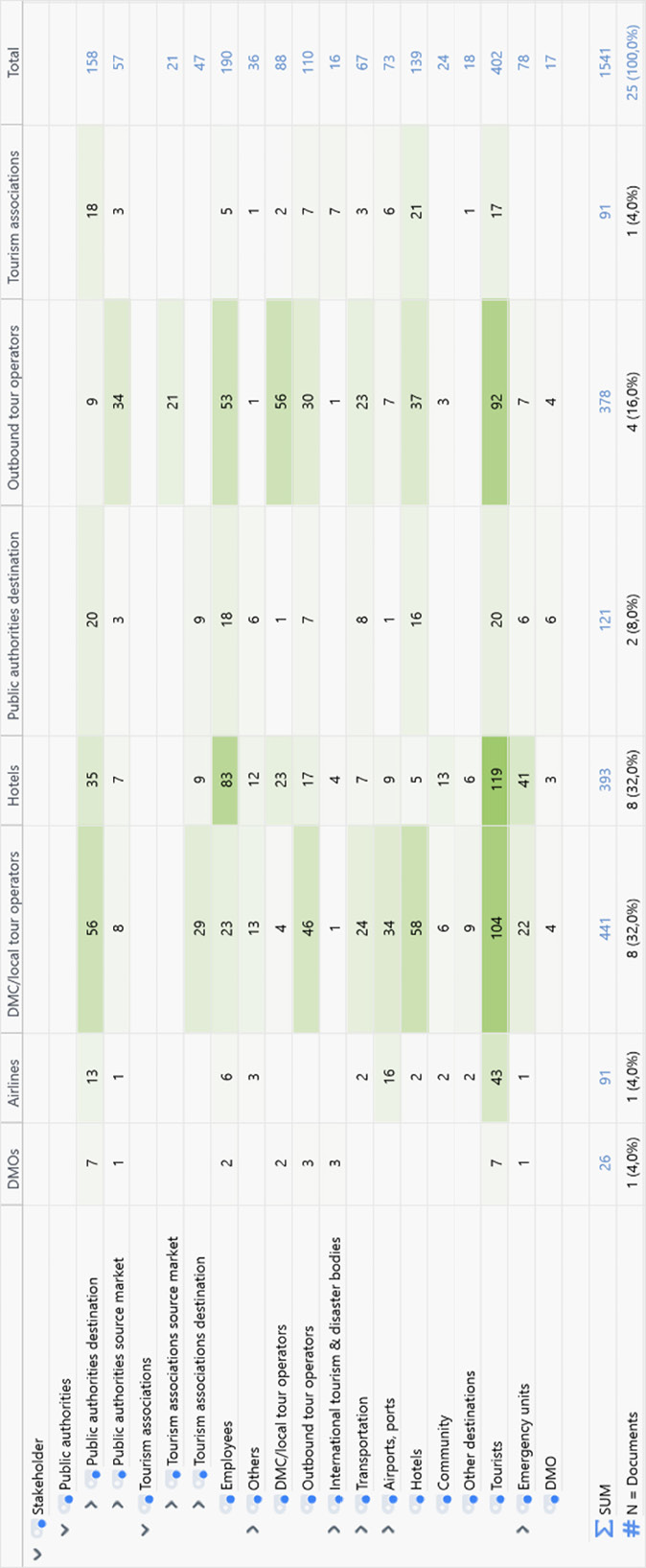

The Code Matrix Browser in Figure 6 shows with which actors (rows) the interviewed stakeholder groups (columns) interact during a crisis. The academic expert was excluded due to their advisory function in this case. The higher frequency of mentions from DMCs, hotels, and outbound tour operators reflects their larger representation in the interviews. However, the observed trend remains valid. A top five list of stakeholder groups gives a better overview of the matrix. It shows that tourists and public authorities appear among the top five of all groups. Public authorities in the destination play a vital role for the tourism businesses and association in the destination, while the public authorities in the source market are of foremost importance for the outbound tour operators. Together with tourists, public authorities rank first among public authorities in the destination, which is caused by the multiple local, regional, and national entities within the governmental agencies. Among the top five, employees appear in six out of seven stakeholder groups, which highlights their stake in tourism destination crisis management. With +/ – 100 counts, tourists are mentioned particularly frequently by hotels, DMCs and outbound tour operators. This hints at a strong connection between these four stakeholders.

Interaction of stakeholders in tourism destination crisis management: Code matrix browser of coded stakeholders per interviewed stakeholder group in absolute numbers (n=1541).

4.2 What impact do the stakeholders have on the destination?

Summary grids were generated in MAXQDA 24 for the codes Collaboration, Cooperation, Network – Roles, Tasks, Crisis Management – Evacuation, and Crisis Management – Crisis Handling. The data were aggregated, condensed, and categorised by stakeholder group, with detailed results presented in the following subsections. Table 4 provides a quantitative overview, indicating the number of tasks mentioned for each stakeholder. Rows represent active stakeholders providing tasks or information to those listed in the columns. Areas with three or more tasks are highlighted in bold and grey to identify stakeholders most involved in task execution or information exchange. The pattern indicates that public authorities hold a dominant role within the destination, primarily distributing tasks and information. Tourism associations follow in frequency, demonstrating a strong connection with both public authorities and hotels. While hotels predominantly receive tasks or information, DMCs and outbound tour operators maintain a more balanced position, both actively providing and receiving information and tasks.

4.2.1 Impact of stakeholders from the source markets

The Ministry of Foreign Affairs adjusts travel advisories for destinations (3TO_GE, 17TO_GE). While tour operators are not legally bound to follow them, they are requested to prioritise citizen safety (3TO_GE, 17TO_GE, 19TO_GE). In crises, they communicate directly with the Ministry or coordinate through the German Travel Association (DRV) (3TO_GE, 17TO_GE, 19TO_GE). Tour operators engage with market participants,

“because of course, as a tour operator, you never act alone

in a situation like this but as a market participant (19TO_GE, Pos. 81)”.

They are part of the Ministry’s crisis committee, which also liases with destination authorities (3TO_GE, 17TO_GE, 19TO_GE, 21PA_DR). Diplomatic missions are contacted by local stakeholders, including hotels (12H_DR, 16H_DR, 17TO_GE, 19TO_GE, 24H_DR), DMCs (5DMC_DR, 6DMC-H_D, 19TO_GE, 20TO_GE, 13DMC_DR), transport providers (6DMC-H_D, 12H_DR, 24H_DR), and tourism associations (1TA_DR). Tour operators request updates from DMCs and hotels and instruct suppliers to assist guests (3TO_GE, 5DMC_DR, 11DMC_DR, 19TO_GE). They organise repatriation flights with hotels, DMCs, airlines, public authorities, and their tourism association, requiring swift action due to limited flight seating capacity (3TO_GE, 5DMC_DR, 17TO_GE, 19TO_GE, 20TO_GE). They also arrange evacuations to alternative accommodations (10_DR). In the recovery phase, they support DMOs through funding, investments, and promotions (3TO_GE).

Impact of stakeholders in tourism destination crisis management: Number of tasks and responsibilities mentioned by the interviewees (n=26). Rows → Giving information/instructions. Columns ↓ Receiving information/instructions.

|

Stakeholder |

Public authorities source market |

Tourism associations source market |

Outbound tour operator |

Public authorities destination |

Tourism associations destination |

Hotel |

DMC |

Transpor-tation companies |

DMO |

Emergency units |

International tourism & disaster bodies |

Other destinations |

|

Public authorities source market |

1 |

|

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

Tourism associations source market |

1 |

|

3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Outbound tour operators |

3 |

|

4 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

4 |

2 |

1 |

|

|

|

|

Public authorities destination |

3 |

|

1 |

10 |

5 |

6 |

5 |

5 |

4 |

4 |

1 |

|

|

Tourism associations destination |

1 |

|

|

11 |

|

9 |

2 |

2 |

|

|

|

|

|

Hotels |

1 |

|

2 |

2 |

1 |

|

3 |

1 |

|

1 |

|

|

|

DMCs |

1 |

|

4 |

1 |

|

5 |

|

3 |

1 |

1 |

|

|

|

Transportation companies |

|

|

3 |

|

|

|

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

DMOs |

|

|

2 |

2 |

|

2 |

2 |

|

|

1 |

|

|

|

Emergency units |

|

|

|

|

|

6 |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

International tourism & disaster bodies |

1 |

|

1 |

3 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

|

|

Other destinations |

|

|

|

2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

4.2.2 Impact of stakeholders in the destination

Hotels play a key role in crisis management due to their direct contact with tourists. They ensure guest safety, provide essential services, and coordinate with diplomatic missions, medical services, emergency units, tourism associations (Asonahores, DHTA), DMCs, and tour operators (12H_DR, 16H_DR, 17TO_GE, 19TO_GE, 24H_DR). Hotels manage evacuations (10H_DR, 12H_DR, 16H_DR) and repatriations with airlines (15AE_DR) while remaining largely self-sufficient in the recovery phase (11DMC_DR, 12H_DR). DMCs function as intermediaries between tour operators, diplomatic missions, hotels, and public authorities (5DMC_DR, 6DMC-H_D, 19TO_GE, 20TO_GE, 13DMC_DR). Following tour operator instructions (3TO_GE, 11DMC_DR, 19TO_GE), they update pax lists (3TO_GE, 13DMC_DR, 14A_DR, 26DMC_DR), check hotel conditions (20TO_GE), and arrange evacuations (3TO_GE, 10H_DR, 26DMC_DR) and repatriations (13DMC_DR, 14A_DR, 23DMC_DR, 26DMC_DR). They evaluate infrastructure damage and coordinate with emergency units and the Association of Incoming Tour Operators of the Dominican Republic (OPETUR) (6DMC_D, 13DMC_DR, 16H_DR, 25DMC_D, 26DMC_DR). Airlines assist in crisis response by coordinating with tour operators (19TO_GE, 20TO_GE), providing flight seats (14A_DR, 17TO_GE, 20TO_GE), transporting relief supplies and staff (14A_DR, 19TO_GE), and handling repatriation (3TO_GE, 5DMC_DR, 17TO_GE, 19TO_GE, 20TO_GE). Tourism associations play a key role in crisis management, informing members, coordinating responses (5DMC_DR, 26DMC_DR), and linking them to diplomatic missions (1TA_DR, 11DMC_DR). The Association of Hotels and Tourism of the Dominican Republic (Asonahores), OPETUR and the Dominica Hotel and Tourism Association (DHTA) act as intermediaries between hotels, DMCs, and public authorities, similar to the DRV in Germany. Asonahores and OPETUR hold key positions in the Tourism Cabinet and Emergency Operations Centre (COE) (1TA_DR, 21PA_DR, 22PA_DR, 16H_DR) and were instrumental in the government’s Covid-19 recovery plans (5DMC_DR, 22PA_DR). Asonahores and DHTA also coordinate evacuations and repatriation efforts between hotels and public authorities (4H_D, 15AE_DR, 24H_DR). Asonahores aims to ensure business continuity, minimise financial and reputational damage, and support post-crisis recovery (1TA_DR). It assigns regional zone owners as communication channels and intermediaries for hotel members (1TA_DR, 13DMC_DR). The Dominican Republic’s tourism cluster provides crisis training, documentation, and preparation for service providers while consulting with public authorities (11DMC_DR). In daily business, the DMO is responsible for the promotion (17TO_GE) of the destination, which is intensified in the recovery phase of a crisis. During a crisis, it informs outbound tour operators about the destination’s status (2DMO_D, 21PA_DR). As a member of the National Emergency Operations Centre in Dominica (NEOC) (2DMO_D), the DMO is responsible for the damage assessment of touristic infrastructure including tourism providers (2DMO_D) and assists the latter in clearing the infrastructure and in organising concessions for tax-free imports of goods (6DMC-H_D). As the executive arm of public authorities, emergency units are per definition a central part of destination crisis management (6DMC-H_D, 12H_DR, 11DMC_DR). Public authority directives are binding (3TO_GE, 19TO_GE). NEOC in Dominica manages crisis response, including evacuation and infrastructure assessment (2DMO_D, 8H_D). The COE in the Dominican Republic, comprising government ministries, emergency units, and tourism associations (21PA_DR, 22PA_DR), issues alerts, organises evacuations, and controls (air)port operations (12H_DR, 14A_DR, 16H_DR, 19TO_GE, 20TO_DE, 21PA_DR, 22PA_DR). The Ministry of Tourism promotes the Dominican Republic, prioritises tourist well-being, assigns regional coordinators (22PA_DR), and collaborates with Asonahores, OPETUR, and airlines on crisis response and repatriation (11DMC_DR, 14A_DR, 20TO_GE, 24H_DR). It introduced e-tickets to track tourists (22PA_DR) and led Covid-19 recovery efforts, covering flight and hotel costs, supporting unemployment, and providing international insurance (5DMC_DR, 22PA_DR). The Tourism Cabinet unites public and private sectors, including ministries, Asonahores, and OPETUR, for coordinated crisis management (1TA_DR, 21PA_DR, 22PA_DR).

4.2.3 Impact of other stakeholder groups

Among the international tourism and disaster bodies, the National Hurricane Centre (NHC) in the US is mentioned several times as a source of information (4H_D, 8H_D, 12H_DR). The certifier Crystal International, well-known within the tourism industry, assisted in setting up health protocols during the Covid-19 pandemic (22PA_DR). The World Bank reviewed its investment programmes after hurricane Maria (2DMO_D), and the Caribbean Disaster Emergency Management Agency (CDEMA) acts as umbrella agency for crises in the Caribbean by providing documents and staff (2DMO_D). Other destinations are assigned two tasks supporting public authorities in Dominica, highlighting the support which is contractually guaranteed among the small Caribbean islands (2DMO_D, 8H_D, 25DMC_D).

4.3 How can stakeholder theory improve the collaboration between designated stakeholders in tourism destination crisis management?

Figure 7 synthesises relevant academic literature (research step 2) and findings from the research questions RQ1 and RQ2 (Research Step 4), illustrating stakeholders involved in a crisis both within and outside the affected destination. Figures 5, 6, and Table 5 highlight the central concern: the well-being of tourists experiencing a crisis while on holiday. Accordingly, Figure 7 positions tourists as primary and definitive stakeholders. Definitive stakeholders – including DMCs, hotels, transport companies, and public authorities – are both inevitable and primary actors. Dormant stakeholders, such as other destinations and international tourism and disaster organisations, are desirable but secondary. Public authorities in the source market, while discretionary, are inevitable secondary stakeholders; though not active in the destination, their travel and security advisories directly influence outbound tour operators. The latter, despite their dependency, remain inevitable primary stakeholders. Emergency units are demanding, necessary, and primary stakeholders, while the DMO is discretionary yet desirable and secondary. Notably, tourism associations hold a dominant yet secondary role in both the destination and source market.

Effective stakeholder collaboration requires an understanding of both challenges and success factors. To analyse this, MAXQDA 24 summary grids were created for the codes Collaboration, Cooperation, Network – Challenges, Success Factors, and Relationship. The aggregated and condensed results are detailed in Table 5, which outlines current challenges, perceived success factors, and recommendations for improvement. Six key themes emerged: relationship, collaboration/cooperation, and professional handling are relatively balanced in terms of challenges and successes, while communication seems to face the most difficulties. Processes show slightly more challenges than success factors, whereas support is predominantly viewed positively. The findings highlight the complex interconnections between stakeholders in both the destination and source market, emphasising the crucial role of networks, cooperation, communication, and trust between tourism businesses, associations, emergency units, and public authorities.

Applied stakeholder criteria mapped to stakeholders in tourism destination crisis management based on Clarkson 1985; Beritelli 2011; Podnar and Jancic 2006; Mitchell, Agle, and Wood 1997.

Challenges of, success factors and recommendations for stakeholder collaboration in tourism destination crisis management.

|

Challenges |

Success factors |

Recommendations |

|

|

Relationship |

Volatility of actors of public authorities source market & tour operators (3TO_GE, 19TO_DE) Dependence of actors of tourism association source market (3TO_GE) Conflicting tour operator interests across destinations hinder cooperation (19TO_GE) DMO lacks independence from government (7H_D) Passive approach of emergency units (25DMC_D) |

Relationship between hotels, tour operators & DMC (12H_DR, 24H_DR), emergency units & supply companies (8H_D, 10H_DR, 24H_DR), public authorities (5DMC_DR, 15AE_DR) & other hotel managers (10H_DR) Monthly meetings of tourism associations, Ministry of Tourism, Ministry of Transport & suppliers (26DMC_DR) DMCs or tour operator representatives as trusted key contacts for tourists (20TO_GE, 24H_DR) |

Constant contact between tourism associations destination & hotels (18H_DR) Personal relationship & trust (5DMC_DR, 12H_DR, 14A_DR, 17TO_GE) Networking (1TA_DR, 5DMC_DR, 6DMC-H_D, 11DMC_DR) |

|

Collaboration/cooperation |

Cooperation between tour operators & DMC depends on training (3TO_GE) Lack of cooperation among DMCs (3TO_GE) Limited tourism association activities in the destination (6DMC-H_D) Poor cooperation between emergency units & hotels due to bribery (24H_DR) Competition & lack of cooperation between ministries; centralised presidential power (15AE_DR) Public authorities destination lack cooperation with tourism associations (1TA_DR, 7H_D), hotels (1TA_DR, 7H_D, 24H_DR), DMCs (19TO_GE, 25DMC_D), airlines (14A_DR) Weak network among tourism suppliers (23DMC_DR, 25DMC_D) |

Tour operators with DMC (12H_DR, 24H_DR), emergency units & suppliers (8H_D, 10H_DR, 24H_DR), public authorities & other hotel managers (10H_DR) DMCs with hotels (14A_DR, 24H_DR) & airlines (14A_DR, 23DMC_DR) Tourism associations and public authorities destination (1TA_DR, 5DMC_DR) Hotels with public authorities destination (1TA_DR, 10H_DR) & tourism associations destination (1TA_DR): Monthly meetings & informal meetings to maintain network (10H_DR) Local network of tour operators (19TO_GE, 20TO_GE) Informal networking in Dominica due to small size (9DMC_D) Ongoing networking with all tourism stakeholders (19TO_GE, 20TO_GE) |

Cooperation (1TA_DR, 5DMC_DR, 6DMC-H_D, 11DMC_DR): – among tour operators as priority for the guests' well-being (19TO_GE) – between hotel & DMO, public authorities, tourism businesses, tourism associations and port authorities (6DMC-H_D) |

|

Communication |

Measures cannot be implemented by DMC due to slow communication of tour operators (20TO_GE) Slow (4H_D) & too little (2DMO_D) communication of public authorities destination Missing communication between tour operators & airlines (20TO_GE) & public authorities destination (19TO_GE) Unclear tasks & roles of public authorities destination lead to different communication of the ministries, causing confusion among private sector (2DMO_D, 15AE_DR) |

Constant communication flow among tour operators & with all tourism stakeholders including service providers (19TO_GE, 20TO_GE) |

Better communication between public & private sector (12H_DR, 2DMO_D) Communication between hotel & DMO, public authorities, tourism businesses, tourism associations and port authorities (6DMC-H_D) |

|

Processes |

Unclear use of travel warning of public authorities source market as safety instrument during Covid-19 pandemic (17TO_GE, 19TO_GE) Lack of transparency of public authorities source market regarding assessment of security situation in a country (19TO_GE) No defined process between public authorities source market and tour operators & tourism association source market (3TO_GE) Missing debriefings of tourism association source market with tour operators (19TO_GE) Hesitant decision-making by tourism association source market (17TO_GE) Lack of process continuity in public authorities due to government changes (11DMC_DR) Unclear roles of public authorities destination cause inconsistent ministry communication & private sector confusion (2DMO_D, 15AE_DR) |

Quick response time of emergency units & availability of medical service, standard procedures between DMCs & medical service & police (9DMC_D) Planned processes of international tourism & disaster bodies with Dominica (2DMO_D) Integration of DMO into emergency unit of public authority NEOC (2DMO_D) Defined roles for & close alignment of departments of public authorities destination due to Dominica’s geographical size (8H_D) Coordination of tourism association source market with public & private sector (3TO_GE, 19TO_GE) Coordination between public authorities destination & DMCs (26DMC_DR) |

Preparation between tour operators & DMCs in advance (19TO_GE) One contact person in public authorities destination per destination for tourism businesses (25DMC_D) One coordination centre per destination (3TO_GE, 19TO_GE, 23DMC_DR) & one per source market (3TO_GE, 19TO_GE) Aligned actions following crisis plan (11DMC_DR, 13DMC_DR More coordination of public authorities destination between stakeholders (4H_D) |

|

Professional handling |

Missing professional crisis management among some tour operators (19TO_GE) Topic of crisis management lacks priority in the travel industry (19TO_GE) |

Professional handling of DMCs to assist tourists (26DMC_DR) Professional handling of police & military to assist tourists (26DMC_DR) Dedication & availability of people involved (19TO_GE) |

Tour operators need to know destination’s infrastructure & language (20TO_GE) Assisting tourists as national priority of public authorities destination (23DMC_DR) Task force of public authorities destination to assist tourism businesses in remote areas (6DMC-HD) Holistic approach & hands-on mentality (1TA_DR) |

|

Support |

Missing assistance from other countries (14A_DR) |

Support of cruise companies & cruise ship guests for DMCs to restart tourism (9DMC_D) Support of international tourism & disaster bodies regarding Covid-19 restart programme (1TA_DR) Financial support of DMO for DMC promotion activities after crisis (6DMC-H_D) Resources from other islands (7H_D, 2DMO_D) Support within the community, among neighbours (9DMC_D) |

Integration of other sub-sectors e. g. insurance companies (1TA_DR) |

5 Discussion

5.1 Stakeholders’ role in tourism destination crisis management

The results indicate that tourists play a vital role in destination crisis management, which is summarised by the following interviewee’s statement regarding successful crisis management.

“If you saved the tourists, put them in a safe place, gave them importance, communicated what happened, gave them follow-up if there was an affected person. It is how the crisis is handled that will tell you if it has really been successful or not” (21PA_DR, Pos. 133).

Interestingly, this stakeholder group has been widely ignored by crisis and disaster research in tourism (e. g. Pyke et al. 2018). It is therefore important to design a network around them which aims to offer the most suitable options for the tourists before, during or after a crisis which are, if necessary:

Appropriate medical treatment,

Evacuation to alternative hotels or public shelters,

Repatriation,

Continuation of the holiday either in the original or in an alternative hotel (see Table 5).

Hotels rank 4th among the most mentioned stakeholders (Figure 5). This aligns with the findings of Sheehan and Ritchie (2005), who name public authorities, hotels and their associations as the most important stakeholders for DMOs. Hotels are the core of the tourism product and have therefore the closest contact with tourists, being experts in customer service. Their tasks before, during and after a crisis are numerous, as they must take care of the tourists directly and immediately (see Table 5). As reported by the hotels interviewed for this study, safety regulations are high, crisis plans are usually specified by the mother companies (8H_D, 10H_DR) and there is usually designated space for evacuation (12H_DR, 16H_DR). In the Dominican Republic, hotels are usually regarded as safe havens for tourists (12H_DR, 16H_DR). Findings from several scholars (e. g. Muskat, Nakanishi, and Blackman 2015; Nguyen, Imamura, and Iuchi 2017) and the UNESCO (2012) state that hotel buildings are usually high with a sturdy structure and room capacity as well as food provision and (often independent) energy and water supply. They therefore propose a closer collaboration between hotels and public authorities because hotels can also serve as evacuation shelters for the local community on a short-term basis, given the fact that hotels have an average occupancy rate of between 60 and 70 percent – the average occupancy rate in Caribbean hotels was 66.6 percent in 2024 (Britton 2025).

The findings indicate that tourism associations should assume a leading role in developing collaborative crisis management strategies. This aligns with research suggesting that such involvement supports small and micro enterprises in overcoming resource limitations (e. g. Jiang and Ritchie 2017). As industry representatives, tourism associations can enhance sector-wide engagement in crisis management (e. g. Jiang and Ritchie 2017).

While ignored in tourism crisis management models, the present results assign outbound tour operators a substantial role in the destination, which is reflected in the following statement:

“Well, as the tour operator, we are the most important authority for our guests, because they have a contract with us and we are the ones who speak the language. We have to remain approachable for the guest and also remain professional and calm and somehow put the guest and their needs at the centre (20TO_GE, Pos. 113–115)”.

For tour operators located in the European Union, this is legally prescribed by EU Package Travel Directive 2015/2302, which requires them to offer prompt and appropriate assistance to customers. This obligation includes arranging accommodation, alternative travel plans at the tour operator’s expense and providing essential information which is in line with the results. Morakabati, Page, and Fletcher (2017) argue that tourism actors in the destination are often well-prepared for crises, partly due to support from outbound tour operators. The results further confirm that tour operators depend heavily on external information because they usually do not have offices in the destination and consequently receive delayed or inaccurate information (e. g. Derham, Best, and Frost 2022).

Public authorities shape the operational framework for tourism organisations in the destination as well as in the source markets, as supported by the findings. Given this interdependence, aligning crisis management strategies between the public and private sectors is essential for fostering a more resilient tourism industry (e. g. Goktepe et al. 2024). Consequently, it is essential for the tourism sector to be recognised by the public authorities to effectively incorporate the industry’s specific needs into their crisis management plans (e. g. Filimonau and Coteau 2020). Interviewee 5DMC_DR, Pos. 75 emphasises:

“Because many times, yes, the private sector has its thing,

but you need the support of the government.”

A key challenge lies in the fragmented political landscape, characterised by multiple governance layers and competing interests, which leads to an overload of public authorities involved in crisis response (e. g. Pennington-Gray, Schroeder, and Gale 2014). In this study, attempts to integrate the needs of the tourism industry can be registered in the Dominican Republic. However, the previously addressed overload of responsible entities can also clearly be detected by reading through the sheer number of organisations involved (see Section 4.2). Generally, cooperation between public authorities and tourism actors is influenced by the political system, economic conditions, and country-specific factors (e. g. Jiang and Ritchie 2017). To enhance crisis response, public authorities should leverage their political power to foster collaboration among tourism organisations (e. g. Jiang and Ritchie 2017). Morakabati, Page, and Fletcher (2017) provide an interesting approach for tourism destination crisis management by distributing the responsibilities in a crisis between public and private sector entities. They assign crisis prediction, warning, and response to public authorities, while activities directly related to tourists (repatriation, alternative accommodation, taking care of tourists) seem to be clearly assigned to the tourist sector. These results can be confirmed by the present study.

Filimonau and Coteau (2020) argue that, especially for small island states in the Caribbean with limited resources, collaboration is essential during crisis, as one island currently not affected may support another island and vice versa. The importance of other destinations aligns with the findings of the present study as well as with Arslan et al. (2021), who assign global partnerships an important role, especially for emerging and developing markets.

The present study reveals interesting findings about the role of DMCs and DMOs in tourism destination crisis management: As intermediators between the source market and the destination, the DMCs have numerous tasks during a crisis and are also represented in the governmental structures of the Dominican Republic with their tourism association. Interviewee 26DMC_DR, Pos. 20 puts their importance in a nutshell:

“We are the eyes here in the destination to report how serious the situation is and what is recommended. We are responsible. It means that if we do not

take the right measure, the problem is always ours.”

To the author’s knowledge, DMCs are not mentioned in the context of crisis management in academic literature. The opposite is true for DMOs: While the interviewees do not attach great importance to them, scholars (e. g. Basurto-Cedeño and Pennington-Gray 2016; Beirman 2018; Beritelli 2011) emphasise their potential strategic relevance in destination crisis management, highlighting their established networks and credibility as intermediator between public and private actors during a crisis.

5.2 Key factors for stakeholder collaboration in tourism destination management

Relationship is key for stakeholder collaboration, particularly during crises. As shown in Table 5, interviewees emphasise the need for consistent contact persons with whom they engage regularly, even before a crisis occurs – a recommendation also supported by Pennington-Gray, Schroeder, and Gale (2014) and Jiang and Ritchie (2017). However, research on tourism networks suggests that relational ties between stakeholders are limited, which limits resource availability and the flow of information within a destination (e. g. Pavlovich 2003). Pennington-Gray, Schroeder, and Gale (2014) highlight the importance of strengthening partnerships between public and private actors across various spatial levels, from local to international, to enhance crisis management in tourism destinations.

Table 5 highlights that collaboration is a primary concern for stakeholders, particularly between the public and private sectors. The already discussed fragmented and interwoven structures of tourism destinations are recognised as challenging (“It’s actually a spider’s web that’s spun out of it” (19TOGE, Pos. 51).), particularly complicating collaboration between the public and private sector. Academic research confirms the importance of inter-agency cooperation (e. g. Filimonau and Coteau 2020), pointing out that the different level of damaging impact which the stakeholders face may lead to different goals, which impedes collaboration (e. g. Jiang and Ritchie 2017). Filimonau and Coteau (2020) stress the need for the public sector to adopt best practices at a regional level, such as within the Caribbean, to enhance crisis resilience. The concept of cross-border cooperation, as suggested by this article’s title, is supported by both interviewees and scholars (e. g. Sheehan and Ritchie 2005). A relevant example is the assistance provided by the Caribbean Disaster Emergency Management Agency (CDEMA) to Dominica following Hurricane Maria in 2017 (2DMO_D).

Communication is fundamental in building crisis management networks and strengthening destination resilience (e. g. Pennington-Gray, Schroeder, and Gale 2014). Since collaboration relies on communication, it is unsurprising that stakeholders identify this as a major challenge, with only one successful communication flow reported between tour operators and service providers (see Table 5). During crises, timely and accurate information is crucial for decision-making. Pyke et al. (2018) see a weakness in the limited communication and the lack of tourism industry involvement in public authorities’ crisis planning, a concern also reflected in the interviewees' responses (Table 5). However, both case studies – Commonwealth of Dominica and the Dominican Republic – have taken initial steps by integrating public and private tourism entities into their crisis units. Nevertheless, findings indicate that further progress is needed.

Crisis planning, including processes and plans, is a substantial part of crisis management (e. g. Wut, Xu, and Wong 2021). This becomes even more apparent in tourism destination crisis management, where stakeholders are forced to interact (e. g. Mistilis and Sheldon 2006). Table 5 shows that the interviewees struggle most with a lack of transparency, roles, tasks, and processes which they expect from the public authorities. In contrast, the coordinating role of tourism associations both in the destination as well as in the source market is praised. Interestingly, suggestions from practice and theory align here: Both call for a central entity which takes the lead in coordinating crisis management between the different stakeholder groups in a destination (e. g. Hartman, Wielenga, and Heslinga 2020).

5.3 Contribution of stakeholder theory to stakeholder collaboration in tourism destination crisis management

To successfully collaborate in a crisis, stakeholders need to accept their mutual interdependence (e. g. Jamal and Getz 1995), which is illustrated in Figure 7. The Figure applies different typologies to stakeholders in tourism destination crisis management. Firstly, to make them visible for scholars and practitioners and secondly, to improve crisis preparedness in destinations. Those steps for successful stakeholder collaboration are also suggested by scholars (e. g. Mojtahedi and Oo 2017). Figure 7 indicates that tourists, the tourism businesses, and the public authorities in the destination are key stakeholders identified as primary and inevitable. Being a definitive stakeholder assigns them the attributes power, legitimacy, and urgency. Mojtahedi et al. (2017) suggest that by systematically increasing those attributes among the specific stakeholders, proactive approaches and the influence on crisis management processes increase as well. Power enables stakeholders to exert social and political influence, legitimacy ensures adherence to norms and mandates, and urgency facilitates prompt coordination of response and recovery efforts (e. g. Mojtahedi and Oo 2017). Jamal and Getz (1995) argue that power and legitimacy are necessary to successfully implement joint decisions. Power, legitimacy and influence are fostered by a collaborative approach (e. g. Berlin and Carlström 2008) which relies on protecting proprietary knowledge, building trust-based relationships, integrating into established networks, and ensuring active stakeholder participation with a shared commitment to mutual benefit (e. g. Fyall, Garrod, and Wang 2012).

6 Conclusion

6.1 Limitations and future research

Finding participants from public authorities and DMOs who agreed to be interviewed proved challenging, which leads to their underrepresentation in this sample. The recruitment process was demanding and lengthy and relied on snowball sampling, where previous respondents recommended interview partners. This method assumes familiarity among stakeholders, potentially causing selection bias (e. g. Jiang and Ritchie 2017). However, this risk was mitigated by the small size of the tourism communities in Dominica and the Dominican Republic, as the same interviewee suggestions emerged repeatedly. The research was conducted by a single researcher, which might limit the perspective of the collected, coded and analysed data and the conclusions drawn.

Future research could build on this qualitative work by further exploring the connections and impacts of the stakeholders interviewed. With stakeholders identified, a quantitative approach, such as social network analysis, could empirically assess their connectivity. This method has been widely applied in tourism research (e. g. Hartman, Wielenga, and Heslinga 2020).

6.2 Theoretical implications to improve stakeholder collaboration

Constant and honest communication, trust and shared understanding are identified as key elements for successful stakeholder collaboration by Jiang and Ritchie (2017). This article’s claim that stakeholder collaboration should cross borders is demonstrated in the results which show the numerous tasks, connections, and impact of stakeholders from outside the destination. Be it the actors in the source market such as tour operators and public authorities, be it neighbouring destinations or international tourism and disaster bodies such as CDEMA in the Caribbean. The latter approach is already studied and confirmed by scholars (e. g. Filimonau and Coteau 2020). Despite their critical roles, the involvement of tour operators and public authorities in source markets, as well as DMCs at the destination level, remains underexplored within the context of tourism crisis management. This study addresses this research gap by offering nuanced insights into the functions and responsibilities of these stakeholders during crisis scenarios. Moreover, the integrative methodological approach – linking multiple stakeholder criteria to the identified actors – enables a more precise characterisation of stakeholder roles. Such clarity holds the potential to foster more effective stakeholder collaboration by aligning actions more closely with specific stakeholder needs, ultimately contributing to enhanced crisis management practices in tourism destinations.

6.3 Practical implications to improve stakeholder collaboration

The stakeholder mapping presented in Figure 7 provides practitioners with a structured framework for systematically identifying and evaluating the relevance of key actors in effective destination crisis management. The figure reveals the central position of tourists, tourism businesses and public authorities as definitive, primary and inevitable stakeholders. A central organisational unit possessing legitimacy, power, expertise and resources is necessary to coordinate the collaboration process among stakeholders in a crisis (Jamal and Getz 1995). The results of this study suggest that tourism associations are particularly well-suited to assume this coordinating role. Consequently, they should be formally recognised and adequately empowered by other actors within the destination governance framework. To serve as a central unit for crisis planning and response in the destination, public authorities need to provide tourism associations with the power and legitimacy. The results further indicate that inter-agency collaboration needs to be conducted in advance to function successfully in a crisis. This could be done by workshops and regular meetings to strengthen the network between all stakeholder groups (e. g. Filimonau and Coteau 2020), which is particularly necessary in view of the fact that the tourism industry consists mainly of small companies (e. g. Jiang and Ritchie 2017). As interviewee 21PA_DR, Pos. 129 points out: “A tourist destination can fail due to a poor handling of a crisis”. This should motivate practitioners to further engage in the topic of crisis management and stakeholder collaboration during crisis prioritising inclusive, trust-based collaboration among key stakeholders.

About the author

Economic Geography Group

Declaration of interest statement

The author reports there are no competing interests to declare.

References

Arslan, Ahmad, Ismail Golgeci, Zaheer Khan, Omar Al-Tabbaa, and Pia Hurmelinna-Laukkanen. 2021. “Adaptive Learning in Cross-Sector Collaboration during Global Emergency: Conceptual Insights in the Context of COVID-19 Pandemic.” Multinational Business Review 29 (1): 21–42. https://doi.org/10.1108/MBR-07-2020-0153.10.1108/MBR-07-2020-0153Search in Google Scholar

Asonahores, G. D. R., ed. 2024. Hotels Directory. https://www.godominicanrepublic.com/media/media-kit/material-downloads/Search in Google Scholar

Basurto-Cedeño, Estefania Mercedes, and Lori Pennington-Gray. 2016. “Tourism Disaster Resilience Scorecard for Destinations (TDRSD): The Case of Manta, Ecuador.” International Journal of Tourism Cities 2 (2): 149–63. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJTC-01-2016-0002.10.1108/IJTC-01-2016-0002Search in Google Scholar

Becken, Susanne. 2013. “Developing a Framework for Assessing Resilience of Tourism Sub-Systems to Climatic Factors.” Annals of Tourism Research 43: 506–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2013.06.002.10.1016/j.annals.2013.06.002Search in Google Scholar

Becken, Susanne, Roché Mahon, Hamish G. Rennie, and Aishath Shakeela. 2014. “The Tourism Disaster Vulnerability Framework: An Application to Tourism in Small Island Destinations.” Natural Hazards 71 (1): 955–72. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-013-0946-x.10.1007/s11069-013-0946-xSearch in Google Scholar

Beirman, David. 2018. “Thailand’s Approach to Destination Resilience: An Historical Perspective of Tourism Resilience from 2002 to 2018.” Tourism Review International 22 (3): 277–92. https://doi.org/10.3727/154427218X15369305779083.10.3727/154427218X15369305779083Search in Google Scholar

Berbekova, Adiyukh, Muzaffer Uysal, and A. George Assaf. 2021. “A Thematic Analysis of Crisis Management in Tourism: A Theoretical Perspective.” Tourism Management 86: 104342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2021.104342.10.1016/j.tourman.2021.104342Search in Google Scholar

Beritelli, Pietro. 2011. “Cooperation among Prominent Actors in a Tourist Destination.” Annals of Tourism Research 38 (2): 607–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2010.11.015.10.1016/j.annals.2010.11.015Search in Google Scholar

Berlin, Johan M., and Eric D. Carlström. 2008. “The 90‐Second Collaboration: A Critical Study of Collaboration Exercises at Extensive Accident Sites.” Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management 16 (4): 177–85. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5973.2008.00548.x.10.1111/j.1468-5973.2008.00548.xSearch in Google Scholar

Boddy, Clive Roland. 2016. “Sample Size for Qualitative Research.” Qualitative Market Research: An International Journal 19 (4): 426–32. https://doi.org/10.1108/QMR-06-2016-0053.10.1108/QMR-06-2016-0053Search in Google Scholar

Britton, Guy. 2025. “Caribbean Hotel Rooms Are Filling Up, Following a Strong Finish to 2024.” https://www.caribjournal.com/2025/02/02/caribbean-hotel-occupancy-rooms-filling-up/Search in Google Scholar

Buhalis, Dimitrios. 2000. “Marketing the Competitive Destination of the Future.” Tourism Management 21 (1): 97–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0261-5177(99)00095-3.10.1016/S0261-5177(99)00095-3Search in Google Scholar

Clarkson, Max B. E. 1995. “A Stakeholder Framework for Analyzing and Evaluating Corporate Social Performance.” The Academy of Management Review 20 (1): 92. https://doi.org/10.2307/258888.10.2307/258888Search in Google Scholar

Creswell, John W. 2013. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.Search in Google Scholar

Departamento de Cuentas Nacionales y Estadísticas Económicas de la República Dominicana, ed. 2024. Estadisticas Turisticas 2023.Search in Google Scholar

Derham, Jess, Gary Best, and Warwick Frost. 2022. “Disaster Recovery Responses of Transnational Tour Operators to the Indian Ocean Tsunami.” International Journal of Tourism Research 24 (3): 376–84. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.2508.10.1002/jtr.2508Search in Google Scholar

Discover Dominica Authority, ed. n.d. Discover Dominica Travel Brochure. https://cdn.discoverdominica.com/production/20190820122951-discoverdominicatravelbrochure-english.pdfSearch in Google Scholar

Discover Dominica Authority, ed. 2024. Discover Dominica: Experiences, Food & Lodging. https://discoverdominica.com/enSearch in Google Scholar

Eastern Caribbean Central Bank, and Eastern Caribbean Currency Union (ECCU) Central Statistical Offices, eds. 2025. Selected Tourism Statistics: Annual Visitors Dominica from 2019–2023. https://www.eccb-centralbank.org/statistics-category/external-sector/selected-tourism-statisticsSearch in Google Scholar

Faulkner, Bill. 2001. “Towards a Framework for Tourism Disaster Management.” Tourism Management 22 (2): 135–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-5177(00)00048-0.10.1016/S0261-5177(00)00048-0Search in Google Scholar

Filimonau, Viachaslau, and Delysia de Coteau. 2020. “Tourism Resilience in the Context of Integrated Destination and Disaster Management (DM 2).” International Journal of Tourism Research 22 (2): 202–22. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.2329.10.1002/jtr.2329Search in Google Scholar

Fink, Steven. 1986. Crisis Management: Planning for the Inevitable. New York: Amacom American Management Association.Search in Google Scholar

Freeman, R. Edward. 1984. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach. Boston: Pitman.Search in Google Scholar

Fyall, Alan, Brian Garrod, and Youcheng Wang. 2012. “Destination Collaboration: A Critical Review of Theoretical Approaches to a Multi-Dimensional Phenomenon.” Journal of Destination Marketing & Management 1 (1–2): 10–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2012.10.002.10.1016/j.jdmm.2012.10.002Search in Google Scholar

Goktepe, Sevinc, Gurel Cetin, Arta Antonovica, and Javier de Esteban Curiel. 2024. “The Impact of Government Legitimacy on the Tourism Industry during Crises.” European Research on Management and Business Economics 30 (3): 100259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iedeen.2024.100259.10.1016/j.iedeen.2024.100259Search in Google Scholar

Hartman, Stefan, Ben Wielenga, and Jasper Hessel Heslinga. 2020. “The Future of Tourism Destination Management: Building Productive Coalitions of Actor Networks for Complex Destination Development.” Journal of Tourism Futures 6 (3): 213–18. https://doi.org/10.1108/JTF-11-2019-0123.10.1108/JTF-11-2019-0123Search in Google Scholar

Jamal, Tazim B., and Donald Getz. 1995. “Collaboration Theory and Community Tourism Planning.” Annals of Tourism Research 22 (1): 186–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(94)00067-3.10.1016/0160-7383(94)00067-3Search in Google Scholar

Jiang, Yawei, and Brent W. Ritchie. 2017. “Disaster Collaboration in Tourism: Motives, Impediments and Success Factors.” Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management 31 (4): 70–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2016.09.004.10.1016/j.jhtm.2016.09.004Search in Google Scholar

Khardani, Christin, and Jürgen Schmude. 2024. “A Micro‐Level Model for Crisis Management in Tourism Destinations: An Interdisciplinary Approach.” Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management 32 (3): e12619. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-5973.12619.10.1111/1468-5973.12619Search in Google Scholar

Kodijat, Ardito. 2012. A Guide to Tsunamis for Hotels: Tsunami Evacuation Procedures. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000226428Search in Google Scholar

Kuckartz, Udo, and Stefan Rädiker. 2023. Qualitative Content Analysis: Methods, Practice and Software. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.10.4324/9781003213277-57Search in Google Scholar

Mackay, Elizabeth A., and Andrew Spencer. 2017. “The Future of Caribbean Tourism: Competition and Climate Change Implications.” Worldwide Hospitality and Tourism Themes 9 (1): 44–59. https://doi.org/10.1108/WHATT-11-2016-0069.10.1108/WHATT-11-2016-0069Search in Google Scholar

McComb, Emma J., Stephen Boyd, and Karla Boluk. 2017. “Stakeholder Collaboration: A Means to the Success of Rural Tourism Destinations? A Critical Evaluation of the Existence of Stakeholder Collaboration within the Mournes, Northern Ireland.” Tourism and Hospitality Research 17 (3): 286–97. https://doi.org/10.1177/1467358415583738.10.1177/1467358415583738Search in Google Scholar

Mistilis, Nina, and Pauline Sheldon. 2006. “Knowledge Management for Tourism Crises and Disasters.” Tourism Review International 10 (1): 39–46. https://doi.org/10.3727/154427206779307330.10.3727/154427206779307330Search in Google Scholar

Mitchell, Ronald K., Bradley R. Agle, and Donna J. Wood. 1997. “Toward a Theory of Stakeholder Identification and Salience: Defining the Principle of Who and What Really Counts.” The Academy of Management Review 22 (4): 853–86. https://doi.org/10.2307/259247.10.2307/259247Search in Google Scholar

Mojtahedi, Mohammad, and Bee Lan Oo. 2017. “Critical Attributes for Proactive Engagement of Stakeholders in Disaster Risk Management.” International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 21: 35–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2016.10.017.10.1016/j.ijdrr.2016.10.017Search in Google Scholar

Morakabati, Yeganeh, Stephen J. Page, and John Fletcher. 2017. “Emergency Management and Tourism Stakeholder Responses to Crises: A Global Survey.” Journal of Travel Research 56 (3): 299–316. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287516641516.10.1177/0047287516641516Search in Google Scholar

Muskat, Birgit, Hitomi Nakanishi, and Deborah Blackman. 2015. “Integrating Tourism into Disaster Recovery Management.” In Tourism Crisis and Disaster Management in the Asia-Pacific, edited by B. W. Ritchie, 97–115. CABI Tourism Management Research Series, vol. 1. Wallingford: CABI.10.1079/9781780643250.0097Search in Google Scholar

Nguyen, David N., Fumihiko Imamura, and Kanako Iuchi. 2017. “Public-Private Collaboration for Disaster Risk Management: A Case Study of Hotels in Matsushima, Japan.” Tourism Management 61: 129–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2017.02.003.10.1016/j.tourman.2017.02.003Search in Google Scholar

Nogueira, Sónia, and José Carlos Pinho. 2015. “Stakeholder Network Integrated Analysis: The Specific Case of Rural Tourism in the Portuguese Peneda‐Gerês National Park.” International Journal of Tourism Research 17 (4): 325–36. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.1989.10.1002/jtr.1989Search in Google Scholar

Oxford English Dictionary. 2023. “Cooperation, n.” In Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/OED/5240065687.10.1093/OED/5240065687Search in Google Scholar

Paraskevas, Alexandros, and Beverley Arendell. 2007. “A Strategic Framework for Terrorism Prevention and Mitigation in Tourism Destinations.” Tourism Management 28 (6): 1560–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2007.02.012.10.1016/j.tourman.2007.02.012Search in Google Scholar

Patton, Michael Quinn. 2015. Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods: Integrating Theory and Practice. 4th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.Search in Google Scholar

Pauchant, Thierry C., and Ian I. Mitroff. 1992. Transforming the Crisis-Prone Organization: Preventing Individual, Organizational and Environmental Tragedies. 1st ed. Jossey-Bass Management Series. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. https://permalink.obvsg.at/AC00682130.Search in Google Scholar

Pavlovich, Kathryn. 2003. “The Evolution and Transformation of a Tourism Destination Network: The Waitomo Caves, New Zealand.” Tourism Management 24 (2): 203–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-5177(02)00056-0.10.1016/S0261-5177(02)00056-0Search in Google Scholar