1 Introduction

In our target article, we made the claim, based on experimental data on gestures and ideophones, that at-issueness is not a binary notion, but rather a gradient one. We showed how various factors can cause iconic enrichments to fall at different points along a scale of at-issueness. We then proposed a formalisation of this concept of at-issueness based on relevance to the Question Under Discussion (QUD). The responses to our article are, we hope, just the beginning of an interesting discussion not only on the nature of at-issueness and how to model this in formal semantics, but also on the role and contribution of a variety of iconic enrichments in natural language meaning. We would like to thank all the authors for their replies, which have brought us new insights into our research, suggested avenues for future research and raised issues in our current model of gradient at-issueness.

This article is structured as follows; in Section 2 we will discuss the insights into iconic phenomena that have been raised by the responses to our article, before discussing how best to model iconicity in the semantics in Section 3. In Section 4, we will move on to at-issueness and reiterate why we believe at-issueness truly is gradient, before finally discussing necessary refinements to our formalism in Section 5. Section 6 concludes the paper.

2 Insights into iconic phenomena

2.1 Gestures

Both Laparle and Schlenker have suggested potential limitations or problematic aspects in our approach to gesture semantics that we would like to address here. Firstly, Laparle suggests that the analysis given in Ebert et al. (2020) may be problematic when applied to gesture types other than the iconic examples discussed in our article. However, we would argue that our preferred analysis can capture these distinctions. A key point to make here is that the exact meaning content of the co-speech gesture depends upon the expression with which it aligns. Our examples all concerned gesture aligning with parts of or the whole DP, hence the lexical meaning of the gesture was always an entity. This is not necessarily the case for alignment with all parts of speech, however. In Laparle’s example (2), repeated in (1), the most salient interpretation is that the stroke of the gesture aligns with the adjective smallest. Hence, rather than the gesture depicting a referent, it depicts a property.

| I’d like [the smallest piece of cake.]_SMALL |

| SMALL: one-handed gesture with index finger and thumb held close together as if to pinch a small object |

Laparle gives a second example, repeated in (2), arguing that the metaphorical extension of the iconic gesture BIG to the abstract concept of a problem cannot be captured by our approach.

| That is [the most important problem.]_BIG |

| BIG: two-handed gesture with hands held far apart, palms open and facing each other, as if to hold a large rectangular object |

While this is certainly true, it does not seem to be a problem that is particularly tied to the approach of Ebert et al. (2020) or semantic gesture theories in general. It is rather a matter of how metaphoric interpretations can be derived in general. This holds for the adjective big in the same way as for the gesture BIG. To capture these cases, the theory of Ebert et al. (2020) would have to be pragmatically enriched in the manner suggested by Laparle, i.e. by mapping size to importance. If the gesture is temporally aligned with the entire definite DP the most important problem, the account of Ebert et al. (2020) predicts that a non-at-issue contribution is triggered, namely that the most important problem is identical to the abstract object that is gesturally illustrated and which is big. If some pragmatic operation that maps bigness to importance is applied, then it will follow that the problem under consideration is very important. If the gesture aligns with the adjective big, and not the DP, as also seems to be the case for the gesture depicting small above, then the gesture can be assumed to depict the property of bigness. Overall, within Ebert et al.’s (2020) analysis, the interpretation of the gesture is dependent on the alignment of speech and gesture and as such, it seems perfectly possible to adapt this analysis to a range of gesture and speech combinations.

Schlenker, on the other hand, has suggested that co-speech gestures are not supplemental, providing an alternative analysis of these as cosuppositional instead. This is based on the differences between co-speech and post-speech gestures when embedded in negative environments. Schlenker provides an example illustrating this, which is repeated in (3). He argues that post-speech gestures follow the behaviour of appositives in being infelicitous in negative environments, as in (3-b) and (3-c), whereas co-speech gestures are acceptable, as in (3-a).

| a. | One/ None of these guys [helped]_UP his son. |

| b. | One/# None of these guys helped his son, which he did by lifting him. |

| c. | One/# None of these guys helped his son - UP. |

We agree with the judgements in these cases, but similarly to Laparle’s example in (1), we would like to highlight that there is a categorical difference between gestures aligned with DPs and those aligned with VPs. In (4-a), the utterance appears to be infelicitous when the co-speech gesture is aligned with the DP in a negative environment, mirroring the behaviour of the appositive in (4-b) and the post-speech gesture in (4-c). Again this is reflected in Ebert et al.’s (2020) approach to gestures; given that a gesture aligned with a DP depicts an individual referent, it would make sense that this gesture would be infelicitous when there is no referent.

| a. | One/# No philosopher brought [a bottle]_BIG to the talk. |

| b. | One/# No philosopher brought a bottle, which was big, to the talk. |

| c. | One/# No philosopher brought a bottle to the talk - BIG. |

What is more, post-speech gestures seem to display gradient at-issueness behaviour themselves (see Ebert 2017 and Ebert to appear). The more stand-alone these post-speech gestures are, the more at-issue they seem to be. Hence, the longer the pause is between the end of a sentence and a post-speech gesture, the more felicitous a direct denial to the gesture content becomes. If the gesture is interpreted as entirely independent, it contributes a propositional statement of its own comparable to the utterance it is big.

Finally, Schlenker proposes that the behaviour of gestures when combined with a demonstrative can be captured within the semantics of demonstratives themselves rather than requiring an additional analysis for the shifting impact this has on gestures. However, as Laparle correctly highlights, demonstratives are not the only means for shifting co-speech gestures towards at-issueness. Laparle describes very interesting research, which seems to suggest that speakers can shift gestures towards at-issueness by putting greater effort into the gesture, or shift certain elements of speech towards at-issueness using facial expressions such as an eyebrow raise. Using greater effort to shift gestures towards at-issueness could be explained by the effort code, as proposed by Gussenhoven (2004). Gussenhoven argues that greater articulatory precision in spoken language is associated with greater effort, and greater effort is used to convey more important information. For example, Pfau and Steinbach (2006) point out that the effort code is likely responsible for the grammaticalisation of particular intonation patterns for focus and negation. Assuming then that the effort code extends to all forms of communication, if a speaker uses greater effort to produce a gesture, then it is likely more important and therefore more relevant to the QUD and more at-issue.

Our initial intuitions seem to suggest that gestures can also be shifted by particular facial expressions, such as an eyebrow raise as in (5-a) or even particular prosody, as in (5-b) (cf. Ebert et al. 2020; Esipova 2018) all of which appear to highlight the gesture and shift its content towards at-issueness in a similar manner as demonstratives.

| a. | Cornelia brought [[a bottle]_BIG]_eyebrow raise to the talk. |

| b. | Cornelia brought [a BOTTLE]_BIG to the talk. |

Given that there are other means for shifting gestures towards at-issueness, incorporating the at-issueness shift into the demonstrative semantics would mean that we cannot account for these other means. Instead, the at-issueness shift appears to be due to the way that the demonstrative combines with the gesture and the way that the demonstrative somehow makes the gesture more prominent, as the facial expressions and prosody also do.

However, we would like to dispute the claim made by Laparle that these various alternative means of shifting gestures towards at-issueness work by drawing attention to the gesture. Experimental work by Dillon et al. (2013) showed that at-issueness is not linked to the hearer’s attention, with participants appearing to pay just as much attention to content marked as non-at-issue as they do to at-issue content. Instead, demonstratives and the other means of shifting may be linked to the salience of a gesture. For example, the results in Walter (2022) indicated that character viewpoint gestures are by default more at-issue than observer viewpoint gestures and experimental work is currently being conducted to establish whether this difference is due to the more salient nature of character viewpoint gestures.

2.2 Ideophones

Corver provides very interesting insights into the syntactic structure of ideophones. In particular, Corver highlights that understanding the role of ideophones in the syntactic structure can help us to understand the informational contribution of ideophones. For example, Corver discusses the potential syntactic structure of sentence-initial and sentence-final ideophones, with his observations leading us to consider whether cases of sentence-initial ideophones may be cases of topicalisation, which would also clearly impact upon their at-issue status.

Nevertheless, we would like to draw a distinction between what we consider to be ‘true’ ideophones and ideophonic verbs. A key feature of ideophones is the fact that their iconic component is interpreted differently depending on the context in which it occurs and how exactly it is uttered. For example, the slow repetition of plitsch platsch in (6-a) gives the impression that a frog is moving slowly up the stairs. This inference cannot, however, be invoked by repeating the ideophonic verb platscht with a slow speech rate, as indicated in (6-b), which appears to be an odd, if not infelicitous utterance. Although there is still an iconic component to this verb, it is distinct from that of a true ideophone.

| Ein | Frosch | geht | [plitsch platsch plitsch platsch]_slow | die | Treppe | hoch. |

| a | frog | goes | ideo | the | stairs | up |

| ‘A frog goes [splish splash splish splash]_ slow up the stairs.’ | ||||||

| ?? Ein | Frosch | [platscht platscht platscht]_slow | die | Treppe | hoch. | |

| a | frog | ideo verb | the | stairs | up | |

| ?? ‘A frog [splashes splashes splashes]_ slow up the stairs.’ | ||||||

2.3 Beyond gestures and ideophones

Beyond the insights into gestures and ideophones, the commentaries have also provided potential extensions of our theory to other iconic phenomena. Steinbach’s discussion of the application of our theory to elements of sign languages is very insightful, particularly his comparison of the properties of iconic enrichments across the modalities and the potential of idiomatic signs to be counterparts to spoken language ideophones. However, based on these properties, we would argue that the iconic enrichments of classifiers are better compared to iconic prosodic modulations in the spoken modality, rather than co-speech gestures. As can be seen in Table 1, classifiers and prosodic modulations are both non-conventionalised, occur in the same modality as the descriptive utterance and do not occur independently of another linguistic item. The only potential difference is that prosodic modulations are not necessarily syntactically integrated in the same manner as classifiers, however they could be argued to be syntactically integrated due to their necessary occurrence with a word that is itself syntactically integrated.

Properties of classifiers and prosodic modulations.

| Classifiers | Prosodic modulation | |

|---|---|---|

| Sign language | Spoken language | |

| Conventionalised | – | – |

| Same modality | + | + |

| Integration | + | – |

| Independent | – | – |

Nevertheless, it is promising that the analysis proposed for ideophones can be extended to classifiers, which suggests that it is well designed to semantically model a range of constructions that combine both iconic depictive content and arbitrary descriptive content. This can also be seen in Steinbach’s analysis of idiomatic signs in sign languages, which also appear to combine descriptive and depictive content.

3 Modelling iconicity

Given that our approach can be applied to a range of iconic phenomena beyond co-speech gestures and ideophones, the next question to be addressed is how exactly we want to model this iconicity. Schlenker suggests that, while our analysis for gestures and ideophones is a useful beginning, future research should aim for a more explicit semantics of iconicity that goes beyond demonstrations and a similarity relation. Similarly, Laparle proposes that instead of simply aiming to integrate multimodal forms into a semantics of natural language, we should aim to reformulate semantics as a whole. While it is clear that iconic forms such as gestures and the iconic components of ideophones add meaning on top of spoken language, we are rather more tentative to categorise this iconicity as inherently linguistic. Instead, we propose that iconic forms and enrichments receive their interpretation compositionally from their combination with standard descriptive language and are not necessarily meaningful in isolation.

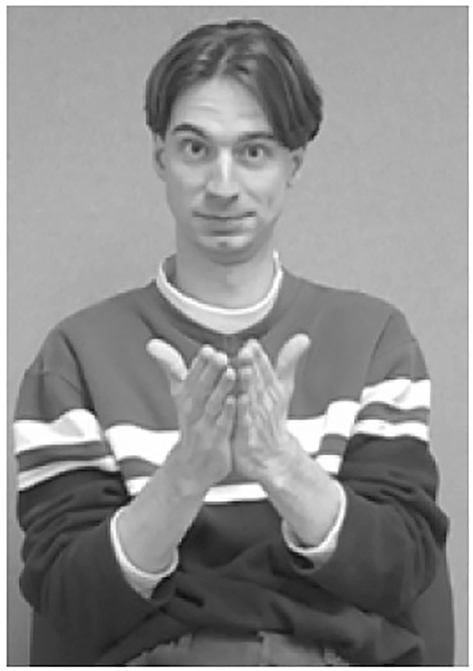

As evidence for this, consider the examples of iconicity in the lexicon of both spoken and sign languages, where this iconicity is not necessarily interpreted semantically. For example, Blasi et al. (2016) have shown that many words for body parts have iconic properties, such as the nasal consonant n in nose or the sign BOOK in American Sign Language (ASL), as in Figure 1. While both of these lexical items are transparently iconic, their iconicity is not necessarily relevant to the interpretation of their lexical semantics (see Emmorey 2001; Taub 2012 for discussion of the interpretation of iconicity in sign languages). Were we to argue for an explicit iconic semantics beyond demonstrations, then it would have to account for why iconicity is interpreted in some cases and not others. In our approach, however, we capture that it is the way that iconic forms occur alongside descriptive language that causes them to be interpreted iconically, with the interpretation of a gesture being fully dependent on its temporal alignment with the expression it co-occurs with. Similarly, the similarity relation between the utterance of an adverbial ideophone and the reported event is triggered compositionally by the utterance of the ideophone as an adverbial. As discussed in Section 2.2, this is not the case for ideophonic verbs such as platschen, although these contain potentially iconic components similar to those of ideophones.

BOOK in ASL (Taub 2001).

4 Is at-issueness gradient?

Koev and Schlenker have suggested interpretations of our experimental results, which could indicate that the effects seen are not due to gradient at-issueness but rather other factors. Koev in particular discusses how considering at-issueness and truth values as gradient may be too severe and instead suggests that the results of our experiment can be captured with an approach that models the gradiency as being due to uncertainty around a speaker’s intention to address the QUD. However, this intuition is not necessarily entirely incompatible with our proposal. While we maintain that at-issueness is indeed gradient, we need not assume that truth values are. A critical point raised here is how to interpret speakers’ ratings of the iconic enrichments in matching and mismatching environments; are these ratings representative of truth values? Or are these rather something else? Kroll and Rysling (2019), for example, argue that we should distinguish between semantic truth and speakers’ evaluations of how appropriate and felicitous a given utterance is in a particular context. Perhaps our previous analysis of such ratings as reflecting the truth values may have been too strong and it would be better to follow Kroll and Rysling (2019) and assume that speakers’ evaluations are distinct from truth values. If we were to adopt this approach, then our experimental results should be reinterpreted as reflecting the speakers’ evaluations of the truth of the utterances in the given contexts, with the prediction being that these evaluations are influenced more towards a true judgement by at-issue content than by less at-issue content. This would of course also require a reformulation of our gradient truth value calculation. Alternatively, we could adopt an approach wherein truth values, as well as at-issueness could in fact be gradient.

Turning now to Schlenker, we would like to take the opportunity to address the explanations that he proposes for our experimental results, as we believe that this discussion will yield interesting insights. Schlenker provides the following potential reasons for the reduced mismatch effect seen for gestures and ideophones in comparison to standard arbitrary content:

Modality (gesture only): gestures can be ignored due to their occurrence in the visual modality.

Semantic failure: mismatching ideophones and gestures trigger some sort of semantic failure instead of falsity.

Underspecification: the relation between the gesture or ideophone and the expression it modifies is underspecified.

Imprecision, vagueness: gestures and ideophones are less precise than their adjectival or adverbial equivalents.

Firstly, we would like to address the third point of underspecification. Schlenker suggests that participants could have interpreted the circular gesture accompanying window as some sort of prototypical gesture, for example a window, the kind of object that’s typically round. However, there was a pre-experiment conducted prior to Ebert et al.’s (2020) main experiment, which established what were seen as prototypical gestures for the objects to be used in the experiment. This then informed the gestures used in the main experiment and prototypical gestures were not included as items in the final experiment. A similar pre-experiment was conducted before the Barnes et al. (2022) experiment to establish the best adverbial equivalents for the ideophones to be used in the main experiment. Here participants were shown the target sentences to be used in the main experiment and had to select the best adverbial to replace the ideophone. While this does not mean that the ideophones have exactly the same meaning as the adverbials, it indicates that participants believe they modify the sentences in a similar manner. Hence it seems unlikely that the results are due to an underspecified relation between the gesture and/or ideophone and the modified expression.

Turning to the remaining points, the question of whether we are seeing semantic failures in the experiment as opposed to falsity (cf. 2. above) relates to what we discussed above; are the ratings measuring gradient truth values or speaker evaluations of appropriateness? If we indeed argue that what is happening in the experiments is some sort of semantic failure then it is not clear what exactly the distinction between semantic failure and falsity is; i.e. how at-issue must a meaning contribution be for it to result in falsity rather than semantic failure? One potential approach would be to assume that content which is above a certain contextual threshold of relevance to the QUD will result in falsity, whereas anything below this will be a semantic failure. For the moment, if we assume that this is the case, then we propose that the remaining explanations given by Schlenker are not incompatible with our analysis, but rather are contributing factors as to why the iconic enrichment is less at-issue and therefore results in semantic failure rather than falsity in mismatching conditions. That is to say that an iconic enrichment occurring in a different modality compared to the main utterance (cf. 1. above) or being somewhat vague and imprecise (cf. 4. above) will result in that enrichment being less at-issue and therefore having less influence on speaker evaluations of truth.

While we have previously discussed the effect of modality on at-issueness, we have not yet discussed the role of precise versus vague meaning on at-issueness. Since writing the target article, we have conducted research into ideophones in Akan, a prototypical ideophonic language, where ideophones are used frequently in every day speech and are highly conventionalised, with highly specified meanings (cf. Agyekum 2008). This experimental work indicated that in contrast to German, adverbial ideophones in Akan are no less at-issue than standard adverbials (Asiedu et al. 2023). Our proposal is that through frequent use, the descriptive meaning component of ideophones in Akan has become more conventionalised and therefore the ideophones have more specified and precise descriptive meaning components compared to ideophones in German. As to why a more precise meaning would result in a more at-issue content, our tentative proposal is that a more specified meaning component will be more informative with respect to resolving the QUD and as such will be automatically more relevant to said QUD in comparison to other alternative propositions. Therefore, while the depictive component of the Akan ideophones remains non-at-issue, the descriptive component being more at-issue causes the ideophone to shift towards at-issueness. Steinbach has also suggested that a modality specific approach to iconicity may be necessary due to iconicity playing a role in the logical core of sign languages. We argue, however, that our Akan results indicate that this is not necessarily an effect related to modality, but rather due to the presence and frequency of iconicity in a language. This is in line with what Steinbach conjectures about the at-issue status of classifiers as opposed to idiomatic signs, namely that classifiers are expected to be less at-issue since the demonstrations used in classifier constructions are less conventionalised than those in idiomatic signs. But in general, similarly to how ideophones are more at-issue in a language where they occur much more frequently and are therefore much more conventionalised, iconicity may be more at-issue in sign languages due to it being a much more pervasive and commonly occurring part of the languages.

In summary then, our experiments demonstrate the gradient nature of at-issueness. The mismatch effect is smaller for German ideophones than German adverbials because speakers do not rate their occurrence in mismatching conditions as poorly as they do for adverbials, due to them being less at-issue than said adverbials. This lower at-issue status is likely due to their imprecise descriptive meanings, which make them less informative with respect to the QUD. Iconic co-speech gestures exhibit an even smaller mismatch effect as they are even less at-issue than ideophones, not only having a less precise meaning than their adjectival equivalents, but also occurring in the visual modality while the main utterance is in the spoken modality.

5 Refining the analysis

Having reiterated our commitment to at-issueness as a gradient property, we now turn to issues raised around our formalisation of gradient at-issueness. One question posed by Gutzmann suggests an interesting future avenue for research into at-issueness; defining what exactly at-issueness is. Gutzmann’s solution is to view at-issueness as propositional prominence, which we find a very interesting proposal and definitely agree that this could be an appropriate explanation. The prominence lending properties listed by Gutzmann certainly overlap a good deal with the properties which we have described for both gestures and ideophones. In particular, Gutzmann highlights that this understanding of at-issueness as propositional prominence provides a means to overcome problems with the appropriateness condition, repeated in (7).

| Appropriateness condition for an utterance wrt. at-issueness: |

| An utterance u with content components t1, …, t n is appropriate in a context c with QUD Q, iff |

Gutzmann points out that this condition makes incorrect predictions with respect to utterances where the matrix clause alone does not answer the QUD, but only when combined with the appositive, as in (8).

| A: | Why is Alex so sad recently? |

| B: | Alex is in love with Deniz, who only loves Liva. |

Here, the question posed by A is only answered via the combination of the matrix and appositive clause and is a perfectly acceptable sentence. However, the condition in (7) would predict it to be infelicitous.

On the other hand, Koev claims that the appropriateness condition is too weak – in a situation where matrix clause and appositive propositions are the only available possible alternatives, our account would predict a sentence as in (9) to be felicitous, no matter how irrelevant both are for the QUD (because the matrix proposition would be assigned a relevance of 1 in such a situation).

| Maria, the best musician in town, came for dinner last night. |

However, as Koev admits, this is only the case if the space of alternatives is extremely limited, which we might assume will not be the case in any communicative situation. But if it were the case, i.e. there are only two possible propositional options, a minimally relevant one and one that is not relevant at all, an utterance with the minimally relevant one as matrix clause assertion seems indeed acceptable, simply because there is no other viable alternative.

Gutzmann proposes two additional principles to replace the minimum appropriateness condition, based on viewing at-issueness as propositional prominence. These are as follows:

| At-issue prominence constraint |

| For any propositional component p in an utterance u, there is no propositional component q of u such that q is more relevant to the QUD and q is less prominent than p. |

| Combined at-issueness |

| If the most prominent propositional component of an utterance u is not relevant enough to the QUD (according to some conversational threshold), then there must be a combined propositional component that includes the most prominent component and at least one other component that is relevant enough to the QUD. |

We think these new conditions combine well with the theory we originally developed and certainly seem to address most of the issues raised by Gutzmann and Koev wrt. the minimum at-issueness condition. Future research should definitely be conducted into at-issueness as propositional prominence, particularly given the overlap between prominence lending properties and properties of non-at-issue content.

However, one issue, which Gutzmann raises, cannot be resolved via these reformulations. According to Gutzmann, certain constructions simply cannot be used to address the QUD, no matter how relevant they are to said QUD, as in (12).

| A: | How do you feel about Bill? |

| B: | # How tall he is! |

| B: | # Wow! |

If Gutzmann is right and B’s reactions to A are indeed infelicitous,[1] it is true that the minimum appropriateness condition does not account for this straightforwardly, but at this point neither does propositional prominence. As of now, we have no solution to offer for such problems, but one potential way to go would be to assume that certain constructions, such as certain types of exclamatives, are simply specified for low propositional prominence. Or alternatively, that exclamatives cannot answer an explicitly given QUD, due to their non-propositional nature and they hence have no relevance for it. And even if exclamatives are defined as constructions with a low threshold of relevance, their actual relevance in a given situation might be even lower and hence not high enough to make an exclamative a felicitous reaction to a given QUD.

Aside from the minimum at-issueness condition, Koev brings forth two main concerns with respect to our theory: 1) he takes issue with the way gradient at-issueness is formally spelled out in our theory, and 2) he questions the link between at-issueness and truth and hence the gradient nature of at-issueness. Wrt. the latter, he argues that at-issueness is binary and proposes to take an alternative path where gradience arises from the fact that a listener might be uncertain about a speaker’s intention of making certain parts of their utterance at-issue. He spells this out in an interesting proposal couched in the framework of Rational Speech Act theory (Frank and Goodman 2012). As we pointed out above, in Section 4, we believe that this analysis is not necessarily incompatible with our proposal.

Concerning his criticism of our formal implementation, Koev correctly captures our picture of how alternatives determine the relevance measure for individual propositions with his calculation of the value for r in his formula (5). But we would like to point out an apparent misconception that appears to inform his criticism of our formalism. Specifically, we do not introduce the measure in (5) “with the apparent goal of ‘normalizing’ van Rooy’s measure in (4)”, as Koev writes. Crucially, it is not r that enters our computation of the joint truth value T(u), as Koev mistakenly suggests in his reformulation of it (his (9)) and in the text following it. We repeat the formula for the computation of the joint truth value given in our target article in (13).

|

|

As can be seen, it is the normalization

|

|

6 Conclusions

Overall, we believe that our article and these responses have initiated an important discussion on the nature of at-issueness, which could have important consequences for natural language semantics. The contribution of iconic enrichments in natural language is important for understanding how meaning can be contributed at different levels and in different manners within language and establishing the information status of such enrichments can not only help us to understand the difference between spoken and sign languages, but also the properties of non or less at-issue content that is not arbitrary. Conceptualising at-issueness as gradient also allows us to capture subtle differences between both iconic and arbitrary constructions and may be able to provide insight into discourse theories and management of the common ground. While our formalism likely requires further refinement and future research will be necessary to provide empirical support for the theory, we believe that this is a promising start.

References

Agyekum, Kofi. 2008. The language of Akan ideophones. Journal of West African Languages 35. 101–129.Search in Google Scholar

Asiedu, Prince, Mavis Boateng Asamoah, Kathryn Barnes, Reginald Duah, Cornelia Ebert, Josiah Nii Ashie Neequaye, Yvonne Portele & Theresa Stender. 2023. On the information status of ideophones in Akan. In Annual Conference of African Languages 45. University of Connecticut.Search in Google Scholar

Barnes, Kathryn Rose, Cornelia Ebert, Robin Hörnig & Theresa Stender. 2022. The at-issue status of ideophones in German: An experimental approach. Glossa 7(1). 1–39. https://doi.org/10.16995/glossa.5827.Search in Google Scholar

Blasi, Damián E., Søren Wichmann, Harald Hammarström, Peter F. Stadler & Morten H. Christiansen. 2016. Sound–meaning association biases evidenced across thousands of languages. In Anne Cutler (ed.), Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 113(39), 10818–10823.10.1073/pnas.1605782113Search in Google Scholar

Dillon, Brian, Charles Clifton & Lyn Frazier. 2013. Pushed aside: Parentheticals, memory and processing. Language, Cognition and Neuroscience 29. 483–498. https://doi.org/10.1080/01690965.2013.866684.Search in Google Scholar

Ebert, Christian, Cornelia Ebert & Robin Hörnig. 2020. Demonstratives as dimension shifters. Sinn und Bedeutung 24. 161–178.Search in Google Scholar

Ebert, Cornelia. 2017. Handling information from different dimensions (with special attention on gesture vs. speech). In Invited talk at Institute of Linguistics. Frankfurt am Main: Goethe-University. https://user.uni-frankfurt.de/∼coebert/talks/CE-Frankfurt-2017.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

Ebert, Cornelia. to appear. Semantics of gesture. Annual Review of Linguistics 10. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-linguistics-022421-063057.Search in Google Scholar

Emmorey, Karen. 2001. Language, cognition, and the brain: Insights from sign language research. New York: Psychology Press.10.4324/9781410603982Search in Google Scholar

Esipova, Maria. 2018. Focus on what’s not at issue: Gestures, presuppositions, appositives under contrastive focus. Sinn und Bedeutung 22(1). 385–402.10.21248/zaspil.60.2018.473Search in Google Scholar

Frank, Michael C. & Noah D. Goodman. 2012. Predicting pragmatic reasoning in language games. Science 336(6084). 998. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1218633.Search in Google Scholar

Gussenhoven, Carlos. 2004. The phonology of tone and intonation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511616983Search in Google Scholar

Kroll, Margaret & Amanda Rysling. 2019. The search for truth: Appositives weigh in. SALT 29. 180–200.10.3765/salt.v29i0.4607Search in Google Scholar

Pfau, Roland & Markus Steinbach. 2006. Modality-independent and modality-specific aspects of grammaticalization in sign languages. Linguistics in Potsdam 24. 3–98.Search in Google Scholar

Taub, Sarah F. 2001. Language from the body: Iconicity and metaphor in American Sign Language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511509629Search in Google Scholar

Taub, Sarah F. 2012. Iconicity and metaphor. In Roland Pfau, Markus Steinbach & Bencie Woll (eds.), Sign language An International Handbook, 388–412. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton.10.1515/9783110261325.388Search in Google Scholar

Walter, Sebastian. 2022. The (not-)at-issue status of character viewpoint gestures. Frankfurt: Goethe University MA thesis.Search in Google Scholar

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Target Article: Kathryn Barnes, Cornelia Ebert; Issue Editor: Hans-Martin Gärtner

- The information status of iconic enrichments: modelling gradient at-issueness

- Comments

- Some remarks on the fine structure of ideophones and the meaning of structure

- Gradient at-issueness, minimum relevance, and propositional prominence

- Gradient at-issueness versus uncertainty about binary at-issueness

- Gradient at-issueness and semiotic complexity in gesture: a response

- On the typology of iconic contributions

- At-issueness across modalities – are gestural components (more) at-issue in sign languages?

- Reply

- Iconicity and gradient at-issueness: insights and future avenues

- Reply to Comments on “Wh-questions in dynamic inquisitive semantics” (TL 49.1/2)

- Dynamic inquisitive semantics—looking ahead and looking back

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Target Article: Kathryn Barnes, Cornelia Ebert; Issue Editor: Hans-Martin Gärtner

- The information status of iconic enrichments: modelling gradient at-issueness

- Comments

- Some remarks on the fine structure of ideophones and the meaning of structure

- Gradient at-issueness, minimum relevance, and propositional prominence

- Gradient at-issueness versus uncertainty about binary at-issueness

- Gradient at-issueness and semiotic complexity in gesture: a response

- On the typology of iconic contributions

- At-issueness across modalities – are gestural components (more) at-issue in sign languages?

- Reply

- Iconicity and gradient at-issueness: insights and future avenues

- Reply to Comments on “Wh-questions in dynamic inquisitive semantics” (TL 49.1/2)

- Dynamic inquisitive semantics—looking ahead and looking back