Abstract

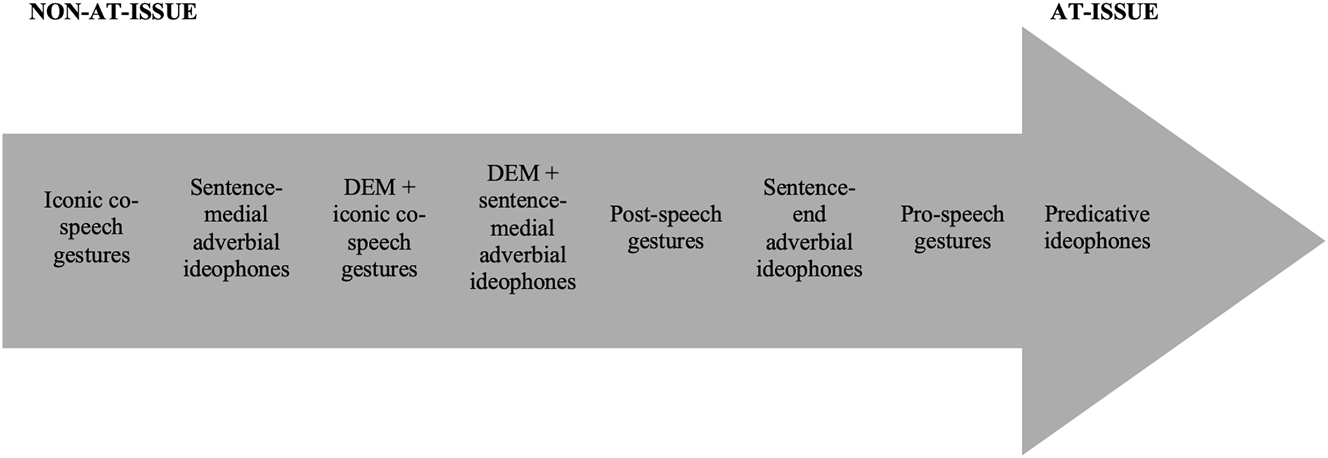

Linguistic structures can contribute different types of meaning alongside standard assertions, such as conventional implicatures and presuppositions, which have long been described as being non-at-issue meaning contributions. Although information status has long been handled as a binary opposition between non-at-issue and at-issue content, recent research suggests that a gradient approach may be more appropriate. Building on new – and in the formal linguistic framework so far mostly neglected – data targeting spoken and gestural iconicity, specifically iconic gestures and ideophones, this paper investigates the information status of such iconic contributions in spoken language and suggests a new theoretical concept of at-issueness by spelling it out as a gradient category. The paper highlights a range of factors which can affect the information status of iconic contributions, proposing a scale for iconic phenomena based on these factors. To formally model this scale, we propose an approach in which at-issueness is analysed as a gradient property based on a given structure-inherent at-issueness status and the corresponding proposition’s relevance to a Question Under Discussion in a given context. This analysis accounts for the variations in information status observed between different iconic enrichments and their impact on truth conditions and paves the way for an approach to Common Ground updates using this model. The analysis outlined here allows for a more nuanced understanding of non-at-issue content and its interaction with at-issue content and provides predictions which can guide further experimental work on information status and the factors that influence it.

1 Introduction

Linguistic structures can contribute different types of meaning alongside standard assertions, such as conventional implicatures and presuppositions, which have long been described as being non-at-issue meaning contributions. As semantic research has turned towards investigating the meaning contributions of iconic enrichments such as iconic gestures and ideophones, there has been particular interest in the at-issueness status of these iconic enrichments as compared to arbitrary items. While experimental work has shown that iconic enrichments appear to be predominantly non-at-issue (cf. Ebert et al. 2020 for gestures and Barnes et al. 2022 for ideophones), there is also evidence that at-issueness may not necessarily be a binary category, but rather a gradient one. The gradient nature of at-issueness has also been indirectly shown for other non-at-issue items by Tonhauser et al. (2018), in experimental work on projectivity. This paper therefore proposes a new approach to at-issueness, whereby it is analysed as a gradient property based on a given structure-inherent at-issueness status and the corresponding proposition’s relevance to a Question Under Discussion in a given context.

Building on new – and in the formal linguistic framework so far mostly neglected – data targeting spoken and gestural iconicity, this paper investigates the information status of iconic contributions in spoken language and suggests a new theoretical concept of at-issueness by spelling it out as a gradient category.

The article is structured as follows. Section 2 will provide background on iconicity, at-issueness and research into the at-issueness status of iconic enrichments in language. Section 3 will discuss semantic theories of gestures and experimental research conducted on the at-issueness status of co-speech gestures, while Section 4 will outline semantic analyses of ideophones and what we believe to be the only study on the at-issueness status of ideophones. Section 5 will discuss factors which can impact upon the at-issueness status of iconic enrichments and in doing so highlight the problems with a binary categorisation of at-issueness and propose an alternative gradient understanding of at-issueness. Section 6 will then present our formal analysis of gradient at-issueness and discuss how this relates to previous analyses of at-issueness status. Section 7 will conclude the paper.

2 Background

As part of the renewed interest in iconicity in language in recent years, semanticists have begun to explore the meaning contributions of iconic components in natural language. Some of this research has focused on the pragmatic status of iconic enrichments and in particular, whether they are at-issue or not. In this section, we will briefly outline the renewed interest in iconicity in linguistics, before discussing the theoretical viewpoints regarding at-issueness and its analyses.

2.1 Iconicity

Following de Saussure (1916), who stressed the importance of the arbitrariness of the linguistic sign, formal linguists have generally assumed an arbitrary relation between form and meaning. There is no logical or intrinsic connection between the word chair and the physical object that it denotes. So-called iconic forms, such as onomatopoeic words like bang and ideophones like splish-splash were considered the exception that proves the rule.

Recently, however, linguists have begun to re-examine the role of iconicity in both sign and spoken languages. While sign languages have traditionally been considered more iconic than spoken languages, recent research suggests that iconicity may play a more prominent role in spoken language than previously thought. Perniss et al. (2010) found, in reviewing iconic mappings in signed and spoken language, that both signers and speakers employ iconic mappings and exploit iconicity in language processing and acquisition. Similarly, Goldin-Meadow and Brentari (2017) and Schlenker (2018c) have argued that in order to properly compare the iconicity between the two modalities, sign languages should be compared to speech + gesture, as gesture may allow speakers a similar level of visual expressivity as is available to signers. In terms of lexical iconicity, Blasi et al. (2016), who analysed lists of 100 basic vocabulary items from over two-thirds of the world’s languages, found iconic biases in the selection or avoidance of particular sound segments. For example, items denoting the tongue are often associated with the lateral “l” and those denoting the nose with the alveolar nasal “n”, which indicates that iconicity may be more prevalent in languages’ lexicons than previously thought. These biases also appear to arise independently rather than due to shared linguistic origins, suggesting that languages share preferences for iconic encodings. Perniss et al. (2010) argue that iconicity should be considered as a general property of language, alongside arbitrariness, whereas Flaksman (2017) goes further and proposes that there is a general requirement for expressivity in language, which iconic words help to satisfy. The pressure of the overall arbitrary system, however, means that iconic words gradually become more arbitrary and lose their expressivity. Flaksman argues that this process of deiconization can come about through changes in an iconic item’s form, such as sound changes, or its meaning, for example metaphor or metonymy extending the meanings of forms away from their iconic roots (see Flaksman 2020 for detailed discussion of different types of deiconization). This, in turn, forces the introduction of new iconic words, a process which Flaksman calls the “iconic treadmill” and argues that this cycle explains the ongoing emergence of new iconic words across languages.

Formal sign language research has also begun to explore iconicity from a new angle after historically avoiding overemphasising the role of iconcity and instead attempting to highlight similarities to spoken language. Schlenker (2018c), for example, provides an extensive overview of the ways in which iconicity in sign language appears to interact with the logical core of the languages, while also making overt semantic processes that are not visible in spoken language.[1]

As previously mentioned, much of the semantic research into iconicity has been focused on the at-issueness status of iconic enrichments in both sign and spoken languages. The next section will explore definitions of at-issueness, as well as the major theoretical approaches to the at-issue/non-at-issue distinction.

2.2 (Non-)at-issueness

It has long been recognised that certain types of linguistic items and structures, such as presuppositions and conventional implicatures (hereafter CIs), contribute meaning in a different way to standard asserted material; they are generally considered to be not at-issue (see Koev 2018 for a recent overview). One of the most commonly used diagnostics for non-at-issue content is whether it can be directly assented or dissented to in discourse (cf. Tonhauser 2012 for example diagnostics for at-issue content). As can be seen in (1), presuppositions, appositives and expressives cannot be directly denied by an interlocutor.[2] Instead, these structures must be targeted by a discourse interrupting interjection such as Hey, wait a minute!.[3]

| A: The King of France is bald. |

| B: # No, that’s not true. There is no king of France! |

| B’: Hey, wait a minute! There is no king of France! |

| A: Maria, the best musician in town, came for dinner last night. |

| B: # No, that’s not true. Lisa is the best musician in town. |

| B’: Hey, wait a minute! Lisa is the best musician in town! |

| A: Ed refuses to look after Sheila’s damn dog. |

| B: # No, that’s not true. Sheila’s dog is lovely. |

| B’: Hey, wait a minute! Sheila’s dog is lovely. |

Simons et al. (2010) have argued that projection under negation and other logical operators is a defining characteristic of non-at-issue content of all kinds. They define at-issue content using relevance to the Question Under Discussion (QUD) and provide the following formal definition (p. 323).[4]

| A proposition p is at-issue iff the speaker intends to address the Question Under Discussion (QUD) via ?p. |

| An intention to address the QUD via ?p is felicitous only if: |

|

Simons et al. (2010) define relevance to the QUD using the yes/no question associated with a proposition, where ?p or whether p denotes the partition of the set of worlds into p and ¬p. A question is relevant to the QUD if it has an answer which contextually entails a complete or partial answer to the QUD, hence ?p must have such an answer. This then explains why the non-at-issue content in (1) cannot be directly denied; speaker A did not intend to address the QUD via this content and speaker B′ recognises this intention. Thus in order to felicitously address the non-at-issue content, speaker B′ must use a discourse interrupting interjection and propose a new QUD.

There are alternative definitions of (non)-at-issue content. Esipova (2019, 2021 for example, defines at-issue content as restrictive and non-at-issue content as non-restrictive. In this paper, however, we adopt the definition of at-issueness given by Simons et al. (2010). Nevertheless, in contrast to Simons et al. (2010), we do not take not-at-issueness to be a monolithic category, but instead argue that non-at-issue content is greatly varied and that there are significant differences in behaviour between different kinds of non-at-issue content, for example the projection behaviour of presuppositions and appositives. This raises questions about how and whether to develop a unified approach to categorising and analysing non-at-issue content. This, however, is beyond the scope of this paper. Here, we choose to focus instead on one particular type of CI, namely supplements (cf. Potts 2005, see ex. (3) below), as we argue that most iconic enrichments demonstrate similar behaviour to these.

| Maria, the best musician in town, came for dinner last night. |

The supplemental appositive in (3) contributes the propositional content that (the speaker thinks that) Maria is the best musician in town. Intonation plays a crucial role here. The appositive is intonationally marked as non-integrated into the main clause. Potts (2005) calls this the ‘comma intonation’ (based on Emonds 1976) and assumes that this is the trigger for opening a second non-at-issue layer next to the at-issue semantics that the sentence has.

The contribution of CIs to truth conditions has been somewhat disputed in the literature. In addressing this question, traditional literature on CIs focused on the multi-propositionality of such structures. Bach (1999), for instance, argued that sentences containing CIs, as in (4), contribute multiple propositions, one for the asserted material and one for the CI, and that the varying degrees of prominence of these CI propositions explain why they are difficult to target through negation or direct denial. He further argued that speakers would struggle to judge the truth value of a sentence with a false CI, but true asserted content and that instead, truth conditions should be considered for each proposition independently.

Similar arguments have been given by researchers such as Dever (2001). In his seminal work, Potts (2005) built upon these ideas and developed a multidimensional model and a new logic to account for different kinds of CIs. Within this framework, Potts (2005) argues that CIs are logically and compositionally independent of at-issue entailments and hence they are not at-issue. Potts argues that all CIs share the following basic properties, which are here illustrated by means of supplements (cf. Potts 2007b):

nondeniability. Supplements cannot be directly denied.

For example, in (4), the appositive structure cannot be directly denied, but must be addressed by a discourse interrupting interjection as in (4-d).

| Nondeniability: | |

| a. | Maria, the best musician in town, came for dinner last night. |

| b. | No, that’s not true. Maria went to the Smiths’ for dinner last night. |

| c. | #No, that’s not true. Lisa is the best musician in town. |

| d. | Hey, wait a minute! Lisa is the best musician in town! |

scopelessness. Supplements cannot appear in the scope of logical operators such as negation.

This can be seen in (5), where the inference from the appositive (highlighted in (5-a)) projects from under negation and the implication that Maria is the best musician in town is not affected.

| Scopelessness: | |

| a. | It is not the case that Maria, the best musician in town, came for dinner last night. |

| b. | ⇒ Maria is the best musician in town. |

antibackgrounding. Supplements can only contribute new information and not information that is already established in the conversation.[5]

In (6-a), the information in the appositive appears odd because it is already given in the preceding utterance and therefore the appositive does not provide new information.

| Antibackgrounding: | |

| a. | Maria is the best musician in town. # Maria, who is the best musician in town, came to dinner last night. |

nonrestrictiveness. Supplements cannot restrict the meaning contribution made by the at-issue part of the utterance.

| Nonrestrictiveness: |

| # If a musician, a famous one, releases an album, they will make a lot of money, but if a musician, an unknown one, does so, they will make nothing. |

In (7), the nominal appositive a famous one is used as to give a restrictive reading of a musician, which renders the sentence odd as appositives cannot be used restrictively (but see Nouwen 2007, based on observations by Wang et al. 2005, for counterexamples such as If a professor, a famous one, writes a book, he will make a lot of money, where the one-appositive actually does act restrictively).

Since the analysis given in Potts (2005), there have been many semantic analyses which develop the original concepts proposed by Potts. These include, among others, Gutzmann (2015) and the dynamic approach proposed by Anderbois et al. (2015), based on the proposal for at-issue content given by Farkas and Bruce (2010). Farkas and Bruce (2010) argue that assertive at-issue content is a proposal by a speaker to update the Common Ground (CG); the proposal is ‘put on the table’ for discussion, so to speak, until all the interlocutors confirm the proposal and it enters the CG, or it is rejected. Non-at-issue content, however, is not put on the table for discussion. Anderbois et al. (2015) therefore propose a unidimensional approach to appositives, where both the main clause and supplemental content are propositional updates to the CG; the difference is that at-issue content proposes an update of the CG, as in Farkas and Bruce (2010), whereas non-at-issue contributions such as appositives impose their content on the CG. Anderbois et al. (2015) also introduce two propositional variables, which we refer to as p and p*, to mark at-issue and non-at-issue content, respectively; propositions designated by p are proposals to update the context set, whereas those designated by p* are silently imposed on the context set.

Anderbois et al. (2015) argue that this approach allows for anaphora between an appositive clause and the main clause, as in (8), where there is an anaphoric link between a woman and her.

| John, who played tennis with a woman, played golf with her too. |

This anaphora is not possible within Potts’ framework, as it does not allow for interaction between the at-issue and the non-at-issue dimension. Hence, Anderbois et al. (2015) argue that their unidimensional set-up is preferable to the system proposed in Potts (2005), as it allows for such interactions between at-issue and non-at-issue content.

The majority of approaches to at-issueness assume a binary relationship between at-issue and non-at-issue content, where propositions are defined categorically as either one or the other. Recent research has, however, provided evidence for a more nuanced approach to at-issueness. Anderbois et al. (2015) and Nouwen (2007), for example, propose that appositives can be interpreted as at-issue when they occur at the end of a sentence rather than sentence medially. Syrett and Koev (2014) have also given experimental evidence for this shift towards at-issueness in appositives. Furthermore, while Tonhauser et al. (2018) did not directly investigate the gradient nature of at-issueness, their experimental work on the Gradient Projection Principle, which predicts that content under an entailment cancelling operator will project to the extent that it is not at-issue, showed that the at-issueness of projective content predicts how much it will project, indicating that at-issueness, alongside projectivity, can also be gradient. In a recent presentation, Gutzmann (2017) also argues for at-issueness as a phenomenon of prominence, comparable to salience. The propositions of one and the same utterance compete for prominence depending on different factors such as structural position, prosodic integration and the like. The most prominent among these propositions will be what is usually seen as the at-issue proposition.

2.3 Iconicity and (non-)at-issueness

As discussed in Section 2.1, recent research into iconic enrichments in sign and spoken languages has aimed to address the at-issueness status of these enrichments. In sign language research, Schlenker (2018b) gives a thorough discussion of iconic enrichments in sign language and their at-issueness status, while research by Kuhn and Aristodemo (2017) has also explored the iconic mapping in pluractional markers in French sign language (LSF), arguing for the at-issue contribution of this iconicity. In spoken language, research into iconic speech-accompanying gestures has shown that they are generally non-at-issue and several semantic approaches have been developed in recent years to account for the meaning contributions of iconic gestures in spoken language, with co-speech gestures being compared to supplements (cf. Ebert and Ebert 2014; Ebert et al. 2020), a specialised form of presupposition or cosupposition (cf. Schlenker 2018a) and non-restricting modifiers (cf. Esipova 2019).

| Cornelia brought [a bottle]−BIG. |

In this example from Ebert et al. (2020), the iconic gesture BIG (indicating the upper and the lower bound of a bottle using two hands with the palm of the upper hand facing downwards and the palm of the lower hand facing upwards) is performed in parallel with the speech signal and temporally aligned with the constituent it is semantically associated with, here: the indefinite a bottle. It then makes a contribution about the size of the bottle Cornelia brought along. This contribution is usually interpreted as non-at-issue information and analysed as supplemental, cosuppositional, or non-restrictive. Note that due to the fact that the gestural information comes in a mode that is different from the oral modality, it is independent from the speech segment and less integrated than the spoken material that constitutes the sentence. The sentence would be grammatical and complete without the gestural addition.

Attention is now also being paid to the meaning contributions of lexicalised iconic forms in spoken language, and in particular ideophones. Experimental work by Barnes et al. (2022) indicates that sentence-medial adverbial ideophones in German, such as plitsch-platsch in the following example, are also not at-issue.

| Der | Frosch | geht | plitsch-platsch | die | Treppe | hoch. |

| the | frog | goes | plitsch-platsch | the | stairs | high |

| ‘The frog goes splish-splash up the stairs.’ | ||||||

Although the ideophone is of the same modality as the rest of the sentence, it shares certain properties with the co-speech gesture in (9). It is not an integral part of the sentence, which would be grammatically complete without the ideophone and it feels less integrated than the other material. This is supported by the fact that it is realized with a specific non-integrational intonation, somewhat parallel to the comma intonation of appositives.

Henderson (2016) has provided a semantic account of ideophones in Tseltal, which is built on the demonstration analysis of Davidson (2015), whereas Kawahara (2020) proposes an analysis for ideophones in Japanese as subjective predicates per Kennedy and Willer (2016).

We believe that these phenomena, which deal with the interplay of ordinary descriptive – and arbitrary – meaning contributions on the one hand and depictive – and hence iconic – contributions on the other, are canonical cases of at-issue information interacting with non-at-issue information. Generally, in natural language, meaning is contributed by using language to describe what one intends to convey. Depictive enrichments add another layer. Since this meaning is of a different nature and often occurs simultaneously with what is being transmitted in the main channel (descriptively used speech), it brings in information of a different dimension, which is usually subordinated. For co-speech gestures this can be seen particularly clearly. Information contributed by gestures is transmitted simultaneously with what is said in the main, verbal, channel, and it is often depictive and iconic and hence of a different nature. Standardly, verbal information then transmits the main, at-issue information part of an utterance, and gesture the non-at-issue pieces of information.

Although ideophones are also verbalized information they are still depictive by nature. They are not given simultaneously with some other verbal information, but add information of a different nature, i.e. iconic information, which cannot be combined straightforwardly with the ordinary descriptive information from the speech channel. This is why ideophones are also usually interpreted as transmitting non-at-issue information (unless they contribute information that is an integral component of an otherwise incomplete utterance, see below).

In the following we will further discuss the gradient nature of at-issueness. We argue that the timing of the information pieces with respect to each other, the nature of this information and the modality involved, alongside other factors heavily influence the degree of at-issueness of a given piece of information. Ebert (2017), for example, claims that information competes for at-issueness status, with more standalone items being more likely to be at-issue due to a lack of competition. For example, under this approach post-speech gestures would be more at-issue than equivalent co-speech gestures due to the lack of competing speech.

Under this view, appositives are the non-canonical, derived, case of non-at-issue information. They are neither presented simultaneously with other pieces of information that are transmitted nor are they depictive. Yet, we believe that the comma intonation, which Potts (2015) argues is crucial for them, indicates their non-integration into the semantics of the remaining part of the utterance. This can be seen as a means to indicate that what is described in the appositive is of a different nature than the rest. Ideally, this information would be presented simultaneously with other parts of the utterance and hence would compete for at-issueness. However, this is, of course, impossible due to the linear nature of spoken language.

Having discussed the research background on both iconicity and at-issueness, we can now explore research on the at-issueness status of iconic gestures and ideophones in more detail, before discussing how these provide evidence for the gradient nature of at-issueness.

3 Gestures

In seminal work exploring the communicative value of gestures, both Kendon (1980) and McNeill (1992) highlighted that gestures can contribute additional information on top of the speech signal, with gesture and speech often working together to convey one thought. Gestures in this sense can be defined as communicative movements of the head, body and limbs transporting emotions, intentions, and thoughts. While we acknowledge that many bodily movements, as well as facial expressions can be considered gestural, for the time being we restrict our analysis to manual gestures. There are a variety of different manual gestures, such as beat, regulatory/discourse, metaphorical, emblematic, pointing and iconic (cf. McNeill 1992).[6] While gesture has long been of interest in semiotics, psychology and cultural studies, its communicative impact has generally not been explored from the perspective of contemporary linguistic semantics. However, as noted in Section 2, semanticists have recently begun to explore the meaning contributions of gestures in spoken language, with particular focus on iconic and pointing gestures. Here, we will only discuss iconic gestures.

McNeill (1992) noted that the temporal alignment of gesture and speech has a significant impact on the interpretation of the gesture, an idea also adopted in semantic research, where iconic gestures have been classified into the following categories according to their positioning with respect to speech: pre-speech, co-speech and post-speech, with Schlenker (2018b) also coining the term pro-speech gesture for gestures which replace speech completely. As discussed in Section 2.3 there are currently three prominent formal semantic theories of iconic gestures in spoken language. These theories focus predominantly on co-speech gestures, while also making some predictions for gestures with different temporal alignments. Ebert et al. (2020) (based on Ebert and Ebert (2014)) analyse co-speech gestures as Pottsian supplements, while Schlenker (2018a) provides an analysis of these gestures as cosuppositions and Esipova (2019) takes an alternative approach and proposes that co-speech gestures are a form of modifier. In this section, we will discuss each of these three approaches in turn, before turning to experimental work conducted on the at-issueness status of iconic co-speech gestures.

3.1 Theory

3.1.1 Ebert et al. (2020)

Ebert et al. (2020) (hereafter EEH), spelling out and experimentally validating earlier work of Ebert and Ebert (2014), provide a supplemental analysis of iconic co-speech gestures, in which they contribute meaning in a similar manner to appositives, and argue, based on experimental data (see Section 3.2.1), that co-speech gestures are by default not at-issue. In order to provide a formal semantics for co-speech gestures, they adapt the approach to appositives developed by Anderbois et al. (2015) and employ the propositional variables p and p* to mark at-issue and non-at-issue content, respectively. Consider example (9) again, repeated below in (11).

| Cornelia brought [a bottle]−BIG. |

Crucially, EEH argue that iconic gestures such as the BIG gesture introduce individuals or individual concepts, just like pointing gestures do. In other words, the gesture does not represent the size of the bottle, but the bottle itself.[7] The gesture represents the bottle, but abstracted away from irrelevant properties and representing in particular the relevant one in the given context, which is the size property. Hence in this case, the iconic gesture BIG represents a big bottle. Formally, we argue that by producing the gesture, this act ‘lexically’ introduces this bottle as an individual concept, comparable to when uttering a name in spoken language. The gesture directly refers to an object or an individual, represented as the gesture referent g. By producing the gesture, an individual concept for this gesture referent is introduced. This is captured formally by introducing a novel discourse referent for a rigid designator I g to the gesture referent g (see Ebert et al. 2020 for details).

| [z] ∧ z = I g where for all w ∈ W: 〚I g 〛(w) = g |

Within this account the interpretation of the gesture is highly dependent on the temporal alignment of gesture and speech; EEH argue that the interpretation of an iconic co-speech gesture depends on how it aligns with the noun phrase and article of a given referent. They give the following analyses of co-speech gestures aligned with a noun phrase, an indefinite article and a definite article.

noun phrase. The relation between a gesture and a temporally aligned noun phrase is one of exemplification. This simply means that the individual gestural concept z must also have the property expressed by the noun phrase, i.e.

indefinite article. When the gesture aligns with an indefinite article, the conveyed, non-at-issue meaning indicates similarity between the gestural and verbal concept. This is expressed via the two place predicate SIM,[8] such that there is a non-at-issue predication

|

|

Here the at-issue contribution of the utterance is that Cornelia brought a bottle, while the non-at-issue contribution is that this bottle is similar to the gesture referent in the relevant dimension (this is the non-at-issue contribution triggered by the temporal alignment of the gesture with the indefinite article) and that the gesture referent also has the property of being a bottle (this is the non-at-issue contribution triggered by the temporal alignment of the gesture with the noun phrase). The non-at-issue contribution hence is that what is gestured represents a bottle and that what is talked about, i.e. the referent that Cornelia brought, has to be similar to what is gestured. Since what is gestured is a bottle that is big in size, the contribution of the gesture (and its alignment with speech) eventually comes down to claiming that the bottle Cornelia brought is big.

definite article. The alignment of a gesture and a definite article conveys a strengthened relation between gestural and verbal referent, namely one of (relativised) identity or

| Cornelia brought [the bottle]−BIG. |

|

|

In this case, alongside the at-issue and non-at-issue contributions, there is an additional presupposition which requires that there be a unique, contextually salient bottle. The at-issue contribution is that Cornelia brought this unique bottle. The non-at-issue meaning conveys that the gesture referent is the same object as this bottle and is itself also a bottle.[10] Hence the non-at-issue inference is that the unique, contextually salient bottle that Cornelia brought is the same as the one indicated via the iconic gesture and hence big.

While EEH argue that co-speech gestures are non-at-issue by default, they also highlight that they can be shifted towards at-issueness status, when accompanied by a dimension shifter, such as a demonstrative, or particular types of focus, prosody and even facial expressions. They show that the German demonstrative SO,[11] for example, shifts the non-at-issue content contributed by the gesture in (16) towards at-issueness status.

| Cornelia | hat | [SO | eine | Flasche] − BIG | mitgebracht. |

| Cornelia | has | dem | a | bottle | with.brought |

| ‘Cornelia brought [a bottle like this]−BIG with her.’ | |||||

EEH provide an analysis of demonstratives as dimension shifters for co-speech gestures, where the demonstrative simply shifts the proposition of evaluation from p* to p. Hence the utterance in (16) can be analysed as in (17).

|

|

Now what is at issue is that Cornelia brought a large bottle, as the previously non-at-issue contribution that this bottle is similar to the gesture referent in size has been shifted to the at-issue dimension. The utterance would be false in the case that Cornelia brought a small bottle. However, the additional contribution that the gesture referent also has the property of being a bottle remains non-at-issue.

While EEH do not directly discuss iconic gestures outside of co-speech gestures, Ebert (2017) has made predictions concerning post-speech gestures. She argues that as post-speech gestures are more standalone than co-speech gestures and do not occur simultaneously with speech, they may be more likely to be at-issue than co-speech gestures.

3.1.2 Schlenker (2018a)

Schlenker (2018a) presents an alternative analysis to Ebert et al. (2020), where co-speech gestures are a specialised form of presupposition. Schlenker highlights that the projection patterns of iconic co-speech gestures and presuppositions are highly similar; and argues that a co-speech gesture triggers a presupposition which requires its content to be entailed by the content of the expression it modifies. Hence presuppositions triggered by co-speech gestures are conditionalised on the at-issue content of the assertion. Schlenker gives the following definition of presuppositions triggered by co-speech gestures (p. 316–317):

| Cosuppositions triggered by co-speech gestures [12] |

| Let G be a co-speech gesture co-occurring with an expression d’ whose type ‘ends in t’, and let g be the content of G. Then G triggers a presupposition d’ ⇒ g, where ⇒ is generalized entailment (among expressions whose type ‘ends in t’). |

Given the utterance in (19), Schlenker argues that the gesture triggers the cosupposition that if Johnny’s mother helped him, this involved some lifting.

| Johnny’s mother [helped]−UP him. |

Assuming that the asserted, at-issue proposition is true, i.e. that Johnny’s mother did indeed help him, and if the cosupposition holds, then Johnny’s mother must have helped him in a way that involved some lifting. Importantly Schlenker notes that, in order to prevent this analysis from overgenerating inferences, for example by positing that helping always entails lifting, the content of the co-speech gesture should be entailed by its local context and not the global context. We can therefore see that in a given situation, such as a gymnastics competition, for example, helping would entail some kind of lifting, but that this need not always be the case. Schlenker (2018a) further argues that co-speech gestures are comparable to weak presupposition triggers such as realise and can therefore be easily locally accommodated. In the case of cosuppositions triggered by co-speech gestures, local accommodation results in the content of the gesture being treated as an at-issue contribution, if the sentence is true and if the speaker is not in a context where the cosupposition is already known to hold.

Crucially, Schlenker furthermore argues that it is empirically adequate to state that the cosupposition also holds in cases of negation or subordination under a modal operator and discusses examples as the following ones.

| Johnny’s mother did not [help]−UP him. |

Here, it is stated that Jonny’s mother did not help him. But additonally, the gesture triggers the (cosuppositional) inference that had she helped him it would have been via lifting.

Finally, Schlenker (2018b) has also argued that pro-speech gestures, as in (21) are by default at-issue.

| Your brother, I am going to SLAP. |

This claim seems to be intuitive because the gesture stands in for crucial lexical material, which would be at-issue and therefore if the gesture were to be non-at-issue, then the sentence would be incomplete and infelicitous.

3.1.3 Esipova (2019)

Esipova (2019) provides an alternative approach to both EEH and Schlenker (2018a), arguing that co-speech gestures are neither inherently at-issue nor non-at-issue, and that their interpretation is not dependent on temporal alignment with speech. Her approach rests upon the idea that narrow syntax and semantics proper are both modality-blind, meaning that gestures compositionally integrate in the same manner as spoken items. Not all gestures can necessarily be compositionally integrated, however. Esipova argues that this is not a problem if we do not assume a uniform analysis for all gestures.

Giving the gesture LARGE as an example, Esipova claims that gestures are “non-lexicalized and [carry] little morphosyntactic information” (p. 92), hence they can either be property-like, in this case similar to the adjective large, and act as modifiers, or they can be nominal-like, in this case similar to the nominal phrase a large one, and be supplements. As modifiers, they can either be restricting and therefore at-issue or non-restricting and therefore non-at-issue. Supplements, per Potts (2005), cannot be restricting and therefore nominal-like gestures are non-at-issue. Supplemental gestures project as supplements, whereas only non-restricting modifier gestures project in the same manner as other non-restricting modifiers.

Esipova further points out that restricting modifier gestures tend to be dispreferred by speakers and argues that this is likely not due to constraints on restricting co-speech gestures in semantics or narrow syntax, but rather constraints in the phonology or pragmatics. She highlights that one potential explanation for this degradedness comes from Schlenker (2018a), who notes that there is a general preference for gestures to be semantically vacuous, i.e. making a redundant contribution, as when there are meaning contributions from two modalities within one utterance, the contribution in the secondary modality should be redundant.

In terms of pro-speech gestures, Esipova (2019) argues that these should be theoretically acceptable as restricting modifiers, but they are often degraded in English due to linearisation and prosodic grouping, which are to some extent language-specific. She does, however, provide examples of pro-speech gestures with restricting interpretations in French, as in (22), and Russian.

| Si | Mélanie | amène | son | chien − SMALL, | ça | ira. | Mais | si |

| if | Mélanie | brings | her | dog−SMALL | it | will.go | but | if |

| elle | amène | son | chien − LARGE, | ce | sera | un | problème. | |

| she | brings | her | dog−LARGE, | it | will.be | a | problem | |

| ‘If Melanie brings her dog−SMALL, then it will be OK. But if she brings her dog−LARGE, it will be a problem.’ | ||||||||

Overall, all three approaches observe that post-speech gestures and pro-speech gestures have an at-issueness status that is, at least by default, different from that of co-speech gestures. While Schlenker claims that co-speech gestures and post-speech gestures are non-at-issue, with pro-speech gestures being at-issue, he also argues that co-speech gestures give rise to cosuppositions, a special kind of presupposition, whereas post-speech gestures act as supplements. Esipova, on the other hand, argues that the at-issueness status depends on whether the gestures are restricting or not. However, likely due to the fact that they are performed at the same time as the verbal material they accompany, co-speech gestures are often not at-issue, which is not the case for pro- or post-speech gestures. Finally, EEH account for the default non-at-issueness status of co-speech gestures, with Ebert (2017) furthermore arguing that the more standalone a gesture is, the more at-issue it tends to be. This then makes the prediction that pro- and post-speech gestures are more at-issue than co-speech gestures.

3.2 Experimental work

While semantic theories on gestures are becoming more and more prominent in the literature, there is still little empirical research being conducted on gestures within semantics. In the remainder of this section, we will present one of the main studies providing evidence for the at-issueness status of iconic co-speech gestures (see also Tieu et al. 2017, 2018 for further experimental work on the information status of gestures).

3.2.1 Ebert et al. (2020)

In an experiment conducted with native speakers of German, Ebert et al. (2020) found empirical evidence for the non-at-issueness status of iconic co-speech gestures. The experiment consisted of a sentence-picture matching task, using a 2 × 2 design, which crossed two mode conditions, iconic co-speech gestures and adjectives, with two match conditions, match and mismatch, in a Latin square design. The two mode conditions were realised through 24 target sentences and the variation between gesture and adjective was realised as in (23) and (24).

| Gesture: | |||||||

| Auf | diesem | Bild | ist | [ein | Fenster]−ROUND | zu | sehen |

| on | this | picture | is | [a | window]−ROUND | to | see |

| ‘In this picture, you see [a window]−ROUND.’ | |||||||

| Adjective: | ||||||||

| Auf | diesem | Bild | ist | ein | rundes | Fenster | zu | sehen. |

| on | this | picture | is | a | round | window | to | see |

| ‘In this picture, you see a round window. | ||||||||

The variation in the match condition was implemented with two pictures, where one picture matched the conditions in the target sentence, while the other did not. An example item can be seen in Figure 1.

Sample item (Ebert et al. 2020).

Overall, there were 24 target sentences, each paired with one matching and one mismatching picture. The procedure for the experiment was as follows; participants were shown a video of a female speaker uttering a sentence. In the target sentences, the speaker also produced a gesture in the gesture condition. All videos were accompanied by a picture. Participants were asked to rate how well the description given by the speaker in the video matched the image using a scale from 1 to 5 with 5 being the sentence perfectly matches the circumstances in the picture and 1 being that it does not match at all.

The experiment was designed as an indirect test of at-issueness. The goal was to have participants evaluate the truth of the target sentence in relation to the situation given by the picture. These truth judgements were gathered via the participants’ response to the meta-question of how well the description in the video matched the picture. The use of a meta-question and rating scale also allowed for participants to express subtleties of judgements with respect to sentences where the information appears to be partly false and partly true. As per research conducted by Kroll and Rysling (2019), which showed that speakers’ truth value judgements are less impacted by information deemed irrelevant to the QUD, i.e. non-at-issue information, the specific hypothesis was that, if co-speech gestures were non-at-issue, there would be a significant interaction of the factors mode and match, such that the mismatch effect (the difference between ratings in the matching and mismatching conditions) would be significantly larger for target sentences containing adjectives than those with speech accompanying gestures. Since no overt QUD was given it was assumed that participants would construe a very generalised QUD matching their understanding of what is at-issue and what is not.

The results of the experiment supported the hypothesis, with the mismatch effect being significantly greater for adjectival target sentences than for co-speech gesture sentences (see Figure 2). EEH therefore argue that these findings corroborate the claim that adjectives contribute at-issue information, whereas co-speech gestures contribute non-at-issue content.

Results of experiment 1 (Ebert et al. 2020, p. 173).

In a second variation of this experiment, EEH repeated the above experiment with the same materials and procedure, but an additional third mode condition, where iconic co-speech gestures were accompanied by the German demonstrative SO. The same target sentences were used as in the iconic co-speech gesture condition, except that the noun phrase was accompanied by the demonstrative SO and the condition was also realised with a video of a speaker uttering the sentence and simultaneously producing the gesture. The onset of the gesture was aligned with the onset of the German demonstrative SO. An example item can be seen in (25).

| Gesture + dem: | ||||||||

| Auf | diesem | Bild | ist | [SO | ein | Fenster]−ROUND | zu | sehen |

| on | this | picture | is | [such | a | window]−ROUND | to | see |

| ‘In this picture, you see a window like that−ROUND.’ | ||||||||

The hypothesis in this variant was that the demonstrative would shift the gesture towards at-issueness status and that the mismatch effect for demonstrative target items would therefore be closer to that of the adjective target sentences. This claim was supported by the results of the experiment, with the mismatch effect being larger for sentences with gestures accompanied by demonstratives than for sentences with gestures not accompanied by demonstratives (see Figure 3). However, this mismatch effect was still not as strong as for adjectives, indicating that while the demonstrative did shift the gesture towards at-issueness, it was still not as at-issue as the adjectives. This provides evidence for not viewing at-issueness as binary, but rather gradient, as was discussed in Section 2.2.

Results of experiment 1 (Ebert et al. 2020, p. 174).

Having discussed gestures as one prominent type of iconic meaning in natural language, we will now turn to another class of iconic phenomena: ideophones. While gestures use the visual modality, ideophones use the same modality as other spoken language phenomena.

4 Ideophones

Ideophones have long been of interest in fields such as cultural studies and within areas of linguistics such as crosslinguistic typology and phonology, where aspects such as the semantic categories they are able to express and their sound-symbolism have been key areas of study (cf. Dingemanse 2012 for an overview of this research). While they are somewhat lacking in Western European languages, ideophones are prolific in languages such as Japanese, the Bantu languages of South Africa and Pastaza Quichua and they have been argued to be a universal or near-universal feature of human language (Diffloth 1972; Kilian-Hatz 1999).

Dingemanse (2019, p. 16) defines ideophones as “[…] an open lexical class of marked words that depict sensory imagery”. Here, we will provide a brief overview of each aspect of this definition, using examples from German (see Barnes et al. 2022 for a detailed argument for the existence of ideophones in German).

open lexical class. Dingemanse argues that the size of the class of ideophones in Japanese is comparable to other open lexical classes in many languages and as such they should be considered one. This does not necessarily mean that all the ideophones must belong to one syntactic class, though. While it may be argued that some languages do not have the same range of ideophones as Japanese, Dingemanse also points out that examples of ideophone creation and ideophonisation in a language indicate an open lexical class. Ćwiek (2022), for example, has shown evidence of idiosyncratic ideophone manipulation and creation in German.

marked. Ideophones are always marked with respect to the morphology and phonology of the language in which they occur. In German this markedness often occurs as reduplication, as in zack-zack and husch-husch, or in the unusual morphology of ideophones such as hopplahopp and holterdiepolter.[13]

words. Ideophones must also be conventionalised forms with specifiable meanings.

depict. Dingemanse furthermore argues that ideophones depict rather than describe. In Dingemanse (2013) he illustrates this with the ideophone tyádityadi, from Ewe, which roughly means “be walking with a limp”. An example from English would be splish splash, which generally describes some kind of movement involving water or wetness which results in splashing sounds. Dingemanse (2013) argues that while the translated expression “be walking with a limp” describes an event of walking with a limp using arbitrary signs that must be interpreted according to a conventionalised linguistic system, tyádityadi depicts the event iconically, using a combination of speech rate, loudness and phonation type, which would likely also be accompanied by expressive intonational foregrounding and gesture, as well as being reduplicated. Similarly, splish splash, when used in a sentence such as the The frog went splish splash up the stairs iconically depicts how the frog’s wetness and movement up the stairs produced splashing sounds, whereas a sentence such as The frog went up the stairs, making splashing sounds gives an arbitrary description of the frog moving up the stairs. As argued by Barnes et al. (2022) (and in Section 2.3), we take the fact that ideophones are depictive and not descriptive as indicative of them contributing meaning in a different manner to other linguistic items.

sensory imagery. Dingemanse (2012) claims that ideophones rely on “perceptual knowledge that derives from sensory perception of the environment and the body”. Nuckolls (2019) notes that onomatopoeic ideophones have often been viewed as simplistic and downgraded compared to other ideophones. However, she highlights phonetic research that shows that producing sound-symbolic vocalisations requires significant effort in vocal manipulation, as well as neurolinguistic evidence that sound is important in cross-modal relations with other sensory perceptions. As an example, Ćwiek (2022) found evidence for the multisensory nature of German ideophones such as holterdiepolter, which could initially be taken as simply sound-symbolic.

It is also worth pointing out that a great deal of literature on ideophones has noted the common co-occurrence of ideophones and iconic gestures. In research conducted using a corpus of Japanese speakers retelling Tweety cartoons, Kita (1993, 1997 found that 94 % of ideophones were accompanied by a gesture. Dingemanse (2013) argues that as spoken narratives are more likely to produce ideophone and gesture combinations, this study may overestimate their prevalence. However, he does claim that as iconic gestures and ideophones are both depictive, it makes sense that speakers would use the two together in order to fully exploit the multimodal nature of the iconic performance. In Dingemanse (2015), he also highlights that speakers in Siwu, when asked to define ideophones, often use iconic gestures to clarify meaning aspects of the ideophones, which may be difficult to express using ordinary vocabulary items. For certain ideophones, very similar gestures were used across speakers, which suggests that these ideophone-gesture pairs may be somewhat conventionalised. Furthermore, Nuckolls (2019) highlighted that in Pastaza Quichua, ideophones encoding movement often co-occur with iconic gestures that contribute additional information. She argues that these gestures act as pragmatic embellishments of the ideophone content. In their research on the morphosyntactic integration, Dingemanse and Akita (2016) also found that less morphosyntactically integrated ideophones in Japanese are more likely to be accompanied by iconic gestures, which appear to enhance the expressiveness of the ideophones and correlate with other expressive modifications of the ideophones such as expressive morphology and intonational foregrounding. Multimodal performances seem to be common place in iconic structures and can also be seen in the combination of facial gestures and manual signs in sign languages. Hence any investigation of the at-issueness status of iconic enrichments must also consider the meaning contributions of combined iconic items, such as ideophones and gestures.

Although there has been much research conducted into ideophones in other areas of linguistics, there has been little semantic work conducted on them. The remainder of this section will first lay out two of the semantic accounts so far provided for ideophones, before proposing a supplemental analysis of the meaning contribution of ideophones. We will then discuss what we believe to be the only experimental work on the at-issueness status of ideophones.

4.1 Theory

4.1.1 Kawahara (2020)

Kawahara (2020) argues that Japanese predicative ideophones are subjective predicates and claims that they have both a core at-issue meaning and a subjective meaning, which encodes their sound-symbolic nature, adapting the counterstance analysis of subjective attitude verbs given by Kennedy and Willer (2016) in order to account for this subjective nature.

Kennedy and Willer (2016) argue that subjective predicates differ from objective ones based on the pragmatic distinction speakers make between objective facts and arbitrary matters of linguistic practice. They give an example where two speakers agree on the objective fact that Lee eats oysters, but not meat, but disagree on whether eating oysters makes him a non-vegetarian or not and hence whether Lee is in the extension of vegetarian. In order to model this formally, they introduce information states, s ⊆ W, which are sets of possible worlds and the set of all information states, S = ℘(W). They furthermore assume that the context c gives a context set of s

c

of what is in the common ground, as well as two functions: κ

c

and

| κ c : ℘(W)↦ p ℘(℘(W)) maps selected s ⊆ W to the set of worlds just like s except for contextually salient decisions about how to resolve indeterminacy of meaning; every s′ ∈ κ c (s) is a counterstance s with respect to c. |

| (Kennedy and Willer 2016, p. 921) |

These counterstances agree with the information state with respect to all objective facts, but disagree on how to resolve matters of linguistic practices. For example, in all counterstances Lee does not eat meat, but does eat oysters, however, in these counterstances vegetarian is a property of individuals who don’t eat meat, but either a) includes or b) does not include those who eat oysters. A proposition such as Lee is vegetarian is therefore subjective, or counterstance contingent,[14] if there is at least one counterstance within the set of generated counterstances κ c (s) where the proposition is not true, i.e. if there is at least one counterstance where Lee is not within the extension of vegetarian. Counterstance contingency can be defined formally as in (27).

| A proposition p ⊆ W is counterstance contingent in context c iff ∃s ∈ S ∃s′ ∈ κ c (s): s ⊆ p & s′ ⊈ p. (Kennedy and Willer 2016, p. 921) |

Kennedy and Willer (2016) argue that speakers can make certain stipulative discourse moves which act to fix certain contextual parameters and therefore help to resolve uncertainties in meaning in discourse. For example by determining the kinds of eating habits that should be considered when deciding if someone is a vegetarian. They term this COORDINATION BY STIPULATION. However not all contextual parameters can be naturally fixed, for example what makes something tasty or what characteristics make someone fascinating. They highlight this distinction with the examples in (28) and (29). According to Kennedy and Willer (2016) the examples in (28) seem natural, whereas those in (29) appear odd.

| For the purposes of this discussion … | |

| a. | … let’s count Lee as vegetarian, since the only animals he eats are oysters. |

| b. | … let’s count these oysters as expensive, because they cost $36 per dozen. |

| For the purposes of this discussion … | |

| a. | ??… let’s count Lee as fascinating, since he is an expert on oysters. |

| b. | ??… let’s count these oysters as tasty, because of their texture and brine. |

Formally, this difference is modelled using the second function provided by the context set,

|

|

| (Kennedy and Willer 2016, p. 921) |

As such, propositions with predicates such as tasty are said to be radically counterstance contingent meaning that no matter how the counterstance space is partitioned, within each partition there will always be one counterstance where the proposition is false. The definition for radically counterstance contingent propositions is given in (31).

| A proposition p ⊆ W is radically counterstance contingent in context c iff

|

| (Kennedy and Willer 2016, p. 922) |

Adopting this approach, Kawahara (2020) then argues that propositions with predicative ideophones in Japanese such as karikari, sakusaku, paripari (Engl: crispy) are radically counterstance contingent. However, according to Kawahara (2019, 2020 these ideophones are gradable and related to a subjective scale, meaning that, although they cannot combine with measure phrases, they can be compared when related to the same subjective scale. This means that these ideophones differ from other subjective predicates, as they can be sorted into sets based on the shared standard for their scales. Speakers can therefore select different ideophones from among this set based on their stance. Formally, this can be expressed as in (32).

| 〚P(x)〛c,w is defined only if 〚P(x)〛 c is radically counterstance contingent in context c. If defined, then 〚P(x)〛c,w = 〚CRISPY(x)〛c,w, where |

| P = predicative ideophones (based on the scale of crispiness): karikari, sakusaku, paripari, etc. |

Kawahara argues therefore, that for a sentence such as (33-a), a speaker may respond as in (33-b). Here the speakers both agree that the pie has the general property of being crispy, but disagree on the exact properties of the pie that make it crispy.

| Kono | pai-wa | karikari | da. |

| this | pie-top | ideo | cop |

| ‘This pie is karikari (crispy).’ | |||

| Iya, | karikari | dewa | nai. | (Sakusaku-da.) |

| no | ideo | cop | neg | ideo-cop |

| ‘No, this pie is not karikari (crispy). (It is sakusaku (crispy).)’ | ||||

Kawahara claims that this is where the sound symbolic nature of ideophones comes into play; the speaker of (33-b) may feel that sakusaku better depicts the crispiness of the pie, for example, due to its form better representing the manner in which the layers of the pie break. The approach proposes then that the ideophones encoding the core meaning of crispiness in Japanese form a set and that speakers may choose from the ideophones in this set based on their subjective view of which ideophone best depicts a given referent.

This analysis is intuitive, as it is likely that speakers interpret the iconicity of ideophones in idiosyncratic and subjective ways and may therefore have a preference for one ideophone over another. The examples Kawahara uses are, though, all predicative ideophones, which we argue necessarily have an at-issue contribution.[15] Nevertheless, we believe that Kawahara’s account provides a good analysis of the dual nature of predicative ideophones where part of the meaning is at-issue,[16] but the iconic component of the ideophone remains non-at-issue (see Section 4.1.3 for further discussion of this point).

4.1.2 Henderson (2016)

Henderson (2016) provides an account of ideophones as demonstrations based on data from Tseltal. To do this, he adapts and formalises the analysis of quotation as demonstration given by Davidson (2015). The basic ideophone construction in Tseltal is formed by combining the verbal stem of the ideophone with the reportative speech marker chi. However, Henderson argues that ideophones are not simply quoted in Tseltal, but that the basic ideophone construction represents an ideophone-specific form of demonstration. He analyses ideophone stems (without the reportative marker) as predicates of events, as in (34) and introduces an operator ideo-demo,[17] which is included in the basic ideophone construction. Just as Davidson (2015) argues that the demonstration argument in spoken quotations in English is introduced by the be like construction, ideo-demo is introduced through the use of the ideo + chi construction in Tseltal.

| 〚ideo〛 = λe[ideo(e)] |

| ideo-demo: λuλdλe[TH δ (d) = u ∧ struc-sim ⌞u⌟ (d, e)] |

This operator selects for ideophone stems in the syntax and in the semantics gives an expression that can be embedded under chi; in other words, ideo-demo “[…] takes a linguistic expression […] and derives a relation between demonstrations and events” (p. 673). Henderson furthermore argues that the ideophone satisfies the theme argument of the basic ideophone construction with the reported speech marker chi, similarly to how the quoted utterance would satisfy the theme argument in a be like construction. In order to become the theme of the basic ideophone construction, the ideophone must therefore be of a particular type, namely a linguistic entity. Henderson (2016) simplifies Potts (2007a) and takes linguistic entities as pairs, ⟨string, semantic representation⟩, where the string is the orthographic/phonological representation of the natural language expression and the semantic representation is the lambda term denoting the appropriate function. For example, the unquoted natural language expression woman is translated to the lambda term as in (36), whereas the quoted natural language expression “woman” is translated as the constant of type μ[18] whose denotation is the pair of the unquoted string and its denotation, as in (37).

| λx e [WOMAN(x)] |

| 〚woman μ 〛 =⟨woman, λx e [WOMAN(x)]⟩ |

The ideo-demo operator therefore requires that the utterance of an ideophone is itself a demonstration and that there be a structural similarity between the ideophone utterance event and the event it depicts. Davidson (2015) intentionally underspecifies the relation between demonstrated and demonstration event, requiring only that the demonstration reproduce salient aspects of the demonstrated event. However, Henderson (2016) argues that the event depicted by the ideophone must satisfy the relevant aspects of the ideophone’s lexical content. For example, only events including an inhaling sound can be depicted by the ideophone jik’. The struc-sim ⌞u⌟ relation provides this condition. struc-sim ⌞u⌟ ensures that the “utterance of an ideophone as a linguistic object” stands for an event that satisfies the ideophone predicate. Formally, this is the case if the demonstrated event can be partitioned so that:

all subevents satisfy the relevant aspects of the ideophone predicate’s lexical content;

the cardinality of the partition is equal to or greater than the number of atomic parts of the demonstration;

there is a temporal similarity between the partition and the atomic parts of the demonstration.

Henderson gives an example using the Tseltal ideophone tsok’, which encodes the sound of something frying in oil, seen in (38).

| Tsok’ | x-chi- ∅ | ta | mantekat |

| ideo | say | in | lard |

| ‘It goes “tsok” in the lard.’ | |||

Henderson (2016) gives the truth conditions of (38) as:

there is an event e that takes place in the lard and the agent is x1 (an individual given by the context or variable assignment).

the demonstration event has the linguistic object tsok’ as its theme.

the demonstration event is structurally similar to e:

As d13 is an atomic event, e must also be partionable into an atomic event (trivial partition).

e must satisfy the predicate λe[TSOK′(e)], i.e. it must be an event of frying sound emission.

This is shown formally in (39).

| ∃e[AG(e) = x1 ∧ THδ(d13) = tsok′ ∧ struc−sim⌞tsok′⌟(d13, e) ∧ LOC(e) = σx[LARD(x)]] |

This approach directly integrates the ideophone into the truth conditions of the sentence, and while Henderson (2016) does not make explicit reference to the at-issueness status of these ideophones, we argue that in these cases the ideophone is predicative and is therefore necessary for both the well-formedness of the sentence and its semantics and is hence used for the computation of the at-issue semantics. Similarly, the combination of the ideophone with the reported speech particle clearly marks the ideophone as part of a quotational or demonstration structure, which as we argue in the next section, also renders the ideophone necessarily at-issue.

4.1.3 A supplemental approach

Here we present an initial, supplemental analysis for adverbial and predicative ideophones which draws upon parts of the approaches in Kawahara (2020) and Henderson (2016) and is based upon data from ideophones in German. However, before we discuss the formal details of the approach, we would like to highlight three factors which appear to impact on the at-issueness status of ideophones (see Barnes et al. 2022 for a more detailed discussion of these factors).

morphosyntactic integration. Crosslinguistically, it has been noted that ideophones demonstrate different behaviour depending on their syntactic category (cf. Kita 1997, 2001; Toratani 2016). For example, Dingemanse (2017) argues that more morphosyntactically integrated ideophones in Siwu, such as predicative ideophones, are, in contrast to adverbial ideophones, able to be negated, used in questions and can contribute old information. These properties appear to indicate more at-issue behaviour and indeed, we argue that predicative ideophones must be partly at-issue; they are essential to the integrity of the sentence and must make some at-issue contribution in order for the sentence to be interpretable. However, we claim that predicative ideophones are mixed items (cf. Gutzmann 2011; McCready 2010), similar to Pottsian expressives such as Köter ‘mutt’, which has the at-issue contribution of denoting a dog and the non-at-issue contribution that the speaker has a negative attitude towards said dog.

Dingemanse (2017) furthermore argues that there may be a typological scale of morphosyntactic integration of ideophones, where in languages with more integrated ideophones, such as Somali, the ideophones tend to be less expressive, while in languages where ideophones are less integrated, as in Semai, the ideophones are more expressive. Seeing as we predict that more integrated ideophones are also more at-issue, we could then also predict, based on this scale, that languages with more integrated ideophones will be more likely to have more at-issue ideophones than those with a lesser degree of morphosyntactic integration.

quotation and demonstration with ideophones. Drawing upon the analysis of ideophone demonstration in Henderson (2016), we propose that ideophones which are quoted or used in demonstrations are also shifted towards at-issueness status. When an ideophone is accompanied by a quotation or demonstration marker, it is directly referred to in the speech and must therefore be partly at-issue in order for the sentence to be felicitous. We furthermore argue, in line with Davidson (2015) and Ebert and Hinterwimmer (2022), that demonstratives such as like in English or so in German can act as quotation/demonstration markers and therefore an ideophone accompanied by a demonstrative will also be shifted towards at-issueness status.

alignment and timing. Dingemanse (2013) notes that ideophones at clause edges generally have more prosodic foregrounding and expressive morphology than those embedded within other constructions, which would likely make them more prominent prosodically and semantically and therefore could indicate that they are more at-issue.

Recall that we find the same tendency as discussed here for ideophones also with gestures: both tend to be more at-issue towards the end of a sentence or the more standalone they appear to be. Both also appear to be shifted towards at-issueness by way of demonstratives. And both are interpreted as at-issue when they form an integral component of an otherwise incomplete utterance.

In general, the crosslinguistic literature indicates several properties of ideophones which are similar to those of non-at-issue content and in particular, co-speech gestures and Pottsian supplements. This includes the fact that ideophones are generally not negated, nor used in questions and that they tend to provide background information (cf. Dingemanse 2017; Kita 1997, 2001; Toratani 2016). These properties are mostly true of adverbial ideophones, which appear to be the most common realisation of ideophones crosslingusitically (cf. Akita 2009).

We propose, therefore, that adverbial ideophones have a similar meaning contribution to co-speech gestures as per the supplemental approach outlined in EEH. While there has been little semantic work on ideophones, other linguistic research provides some evidence to support an analysis of adverbial ideophones as supplements. Kita (1997, 2001 in fact provides an analysis of ideophones in Japanese that closely resembles the multidimensional approach to CIs given by Potts (2005), where he argues that standard linguistic information occurs in the ‘analytic’ dimension and ideophones in the ‘affecto-imagistic’ dimension. The following examples illustrate how the four key properties of supplements as described by Potts (2005) seem to apply to most cases of adverbial ideophones.

nondeniability. Similarly to appositives and other non-at-issue content, it appears that adverbial ideophones cannot be directly denied, but should rather be addressed via a discourse interrupting interjection, such as in the Hey, wait a minute! test. This is shown in (40).

| Der | Frosch | geht | plitsch-platsch | die | Treppe | hoch. |

| the | frog | goes | plitsch-platsch | the | stairs | high |

| ‘The frog goes splish-splash up the stairs.’ | ||||||

| Nein, | das | stimmt | nicht. | Der | Frosch | geht | die | Treppe | runter. |

| no | that | is.right | not | the | frog | goes | the | stairs | down |

| ‘No, that’s not true. The frog goes down the stairs.’ | |||||||||

| # Nein, | das | stimmt | nicht. | Der | Frosch | geht | doch | völlig |

| no | that | is.right | not | the | frog | goes | but | completely |

| geräuschlos | die | Treppe | hoch. | |||||

| silently | the | stairs | high | |||||

| ‘No, that’s not true. The frog goes up the stairs in complete silence.’ | ||||||||

| Hey, | warte | mal. | Der | Frosch | geht | doch | völlig | geräuschlos |

| hey | wait | once | the | frog | goes | but | completely | silently |

| die | Treppe | hoch. | |||||||||

| the | stairs | high | |||||||||

| ‘Hey, wait a minute! The frog goes up the stairs in complete silence.’ | |||||||||||

scopelessness. Adverbial ideophones, like appositives, also appear to be odd when they appear in the scope of negation, as in (41) and (42), where we argue that they are only acceptable as part of meta-linguistic utterances, used in response to a previous utterance.

| ?? | Der | Frosch | geht | nicht | plitsch-platsch | die | Treppe | hoch. |

| the | frog | goes | not | plitsch-platsch | the | stairs | high | |

| ‘The frog does not go splish-splash up the stairs.’ | ||||||||

| ? | Niemand | geht | plitsch-platsch | die | Treppe | hoch. |

| nobody | goes | plitsch-platsch | the | stairs | high | |

| ‘Nobody goes splish-splash up the stairs.’ | ||||||

Other researchers have also noted that adverbial ideophones cannot appear in the scope of logical negation, including Dingemanse and Akita (2016) for Siwu and Kita (1997, 2001) and Toratani (2016) for Japanese.

antibackgrounding. Supplements are said to generally contribute new information, as was pointed out above, where we also critically discussed this claim (see footnote 5). Likewise, it has often been noted that adverbial ideophones tend to only contribute new information (see Dingemanse 2017).

However, as in the case of supplements, it is at least debatable whether this holds in general. Consider the following example.

| Der | Frosch | ist | ganz | nass | und | macht | laut | platschende |

| the | frog | is | completely | wet | and | makes | loud | splashing |

| Geräusche, | als | er | voran | springt. | Schnell | springt | er |

| noises | as | he | forward | jumps | quickly | jumps | he |

| plitsch-platsch | die | Treppe | hoch. |

| plitsch-platsch | the | stairs | high |

| ‘The frog is completely wet and makes loud splashing noises as he jumps along. Quickly, he jumps splish-splash up the stairs.’ |

Although the continuation in example (43) seems a bit odd with the redundant ideophonic information about how the frog went up the stairs, it is certainly not illicit.[19] We leave the discussion about the antibackgrounding condition for supplements and ideophones for future research.

nonrestricting. Supplements cannot be used to restrict the at-issue content of the utterance in which they occur. (44) appears to make little sense unless a very specific context is set up, for example one where boxes are on the stairs in such a way that Peter would need to zig-zag between them to get down the stairs. However, in this case we argue that the ideophones would be somewhat meta-linguistic and this would therefore not be a true example of restriction.

| ??Wenn | Peter | die | Treppe | holterdiepolter | runterläuft, | dann | wird |

| if | Peter | the | stairs | ideo | down.runs | then | will |

| er | sich | verletzen. | Wenn | er | aber | die | Treppe | zickzack |

| he | himself | injure | if | he | but | the | stairs | ideo |

| runterläuft, | wird | er | nicht | stolpern. |

| down.runs | will | he | not | stumble |

| ‘If Peter runs helterskelter down the stairs, then he will hurt himself. But if he runs down the stairs in a zigzag, he won’t stumble.’ |

Given these properties of ideophones and based on the evidence gathered in experimental work by Barnes et al. (2022) (see Section 4.2.1), we present a formal analysis of adverbial ideophones building upon both the analysis that EEH give for iconic co-speech gestures and the analysis of gestural-quotational demonstration by Ebert and Hinterwimmer (2022). Here, we still adopt a binary view on at-issueness, which we will refine in Section 6 below.

We argue that ideophones have two meaning components, like mixed items such as Köter ‘mutt’ do. The first is the ideophone’s conventionalised meaning. In contrast to ordinary mixed items, however, both meaning components of ideophones contribute non-at-issue information, while for Köter it is assumed that the meaning that the individual in question is a dog is at-issue.[20] Hence, the conventionalised meaning contribution of an adverbial ideophone is the same as that of a standard adverbial, namely an event modifier. For example, the use of plitsch-platsch in (45) indicates that the frog went up the stairs in a splashing manner. The second meaning contribution is the iconic meaning of the ideophone. Dingemanse (2013) argues that varying aspects of the ideophone’s utterance contribute to its iconicity, including phonology, prosody and gesture. In order to capture the iconic nature of the ideophone, we follow Henderson (2016) and model the utterance of an ideophone as a demonstration, per Davidson (2015). This enables us to capture all elements of the utterance which contribute to the iconic mapping of the ideophone to the event. Unlike Henderson (2016), however, we do not attempt to specify the exact iconic relation between the event and the ideophone utterance or to integrate this into the truth conditions. Instead, we argue that the utterance of an ideophone alongside a report of an event results in the default non-at-issue inference that the ideophone utterance iconically depicts the event described by the main assertion. We choose to model this using the SIM predicate, which allows for these varying aspects to contribute to the iconic depiction in differing manners depending on the individual utterance and the context in which it occurs.

Applying this to the previous examples, we can then give an analysis of the form of (46) for an utterance such as (45). We again adopt the propositional variables p and p* to mark at-issue and non-at-issue content respectively.[21]

| Ein | Frosch | geht | plitsch-platsch | die | Treppe | hoch. |

| a | frog | goes | splish-splash | the | stairs | high |

| ‘A frog goes splish-splash up the stairs.’ | ||||||

| [e] ∧ goes-up-the-stairs

p

(e) ∧ [x] ∧ agent

|

The at-issue contribution of the utterance then says that there is an event of a frog going up the stairs. The non-at-issue contribution is that this event has the property of being a splashing event and that there is a demonstration, namely the utterance of plitsch-platsch, which is similar in the relevant dimensions to the event of the frog going up the stairs.

As in the cases of co-speech gestures, adverbial ideophones accompanied by a demonstrative also appear to shift towards at-issueness, as in (47). While a plain ideophone seems to be odd as an answer to a wh-question as in (47-b) (see (47-c)) due to its non-at-issueness status, shifting at-issueness via a demonstrative improves the ideophone as an answer (see (47-d)).

| Der | Frosch | geht | plitsch-platsch | die | Treppe | hoch. |

| the | frog | goes | plitsch-platsch | the | stairs | high |

| ‘The frog goes splish-splash up the stairs.’ | ||||||

| Wie | geht | der | Frosch | die | Treppe | hoch? |

| how | goes | the | frog | the | stairs | high |

| ‘How does the frog go up the stairs?’ | ||||||

| # | Plitsch-platsch. |

| plitsch-platsch | |

| ‘Splish-splash.’ | |

| So | plitsch-platsch. |

| dem | plitsch-platsch |

| ‘Like splish-splash.’ | |

We therefore analyse (48) as in (49).