Abstract

Objectives

Gastric carcinoma (GC) remains a high-mortality malignancy that needs efficient ways for the prognosis and therapy of the disease. LncRNAs are biomolecules that participate in cancer progression by regulating gene expression. This study thus investigated the role of lncRNA LINC01711 in GC progression and the underlying mechanisms.

Methods

GC tumor and normal tissues were collected from 150 GC patients. qRT-PCR was used to test the expression of biomolecules. LncBook, Miranda, and starBase databases were employed to explore miRNAs that interact with LINC01711. The association between the biomolecules was validated via a dual luciferase reporter assay. Biological functions of biomolecules in GC cells were measured by the Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) and the transwell migration and invasion assays.

Results

This study found an upregulation of LINC01711 in GC tumor tissues compared to normal tissues. The upregulation of LINC01711 was an indicator of adverse clinical outcomes in GC patients. The miRNA that interacted with LINC01711 in GC was hsa-miR-140-3p. There was a negative correlation between the expression levels of LINC01711 and hsa-miR-140-3p in both GC tumor tissues and cells. LINC01711 promoted GC tumor cell proliferation, migration, and invasion by sponging hsa-miR-140-3p.

Conclusions

LINC01711 might be an ideal prognostic marker and treatment target for GC. The upregulation of LINC01711 was a negative prognostic indicator for GC patients. LINC01711 facilitated GC tumor cell activities related to GC progression by sponging hsa-miR-140-3p.

Introduction

As a prevalent malignancy of the digestive system, gastric cancer (GC) develops through the malignant transformation of gastric mucosal epithelial cells [1]. Most patients in the early stage of GC do not exhibit apparent symptoms and often present with symptoms similar to those of gastritis and gastric ulcer, leading to a relatively low early diagnosis rate for the disease [2]. In advanced stages of GC, the benefits of surgical intervention are significantly diminished, which consequently compromises patient survival rates. At present, the optimal treatment for advanced GC is sequential lines of chemotherapy [3]. Although chemotherapy has increased patient survival, the 5-year survival rate for GC patients in the advanced stage is still below 30 % [3]. While the emergence of molecular targeted therapies and immunotherapies based on molecular mechanisms has opened new avenues, their clinical application remains suboptimal and requires deeper exploration of network-based biomarkers. Exploring potential molecular targets for prognosis and treatment, therefore, holds significant clinical value for improving the overall survival of GC patients.

Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), a subclass of non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs), are defined as transcripts longer than 200 nucleotides [4]. LncRNAs have been reported as a crucial player in gene regulation, making them involved in the development of cancers [4], 5]. In the study by Yue et al., LINC01711 was reported as a driver of GC progression [6]. LINC01711 could coordinate the localization of the lysine acetyltransferase 7 (HBO1)/lysine-specific demethylase 9 (KDM9) complex, which enables LINC01711 to specify the pattern of histone modification and subsequently promotes cholesterol synthesis, thereby facilitating GC progression [6]. Emerging evidence indicates that lncRNAs modulate microRNAs (miRNAs) expression by functioning as competing endogenous RNAs (ceRNAs), thereby influencing gene expression and impacting cancer progression [7]. In the published literature, however, there is no valid information regarding the miRNAs that interact with LINC01711 in GC. Investigating the miRNA that interacts with LINC01711 in GC could not only contribute to the exploration of methods for managing GC but also broaden the understanding of how LINC01711 accelerates cancer aggravation.

MiRNAs are ncRNAs that are 21–23 nucleotides in length [8]. MiRNAs can bind to their target mRNA and block translation, leading to the downregulation of the corresponding gene [8]. miRNAs represent essential regulatory biomolecules that modulate GC progression through diverse molecular mechanisms. For instance, miR-105 was validated as a regulator of the transcription factor protein SRY-Box 9 (SOX9), which in turn altered the GC cell activities and consequently facilitated the advancement of GC [9]. In addition, hsa-miR-129-2, hsa-miR-143, and hsa-miR-145 were also reported to modulate GC cell proliferation and affect GC tumor growth, giving them the possibility of being targets for managing GC tumor development [10], 11]. Considering the importance of miRNA in regulating GC progression, identifying GC-development-related miRNAs and their upstream regulators is vital for the exploration of therapeutic options and targets for GC.

Through comparative analysis of malignant and normal gastric tissues from GC patients, the prognostic value of LINC01711 in GC was investigated in this work. Furthermore, LncBook, miRanda, and starBase databases were used to explore the potential miRNAs that interact with LINC01711 in GC, from which this study obtained a LINC01711-related miRNA for the in vitro study to explore the mechanism by which LINC01711 participates in GC pathogenesis. The objective of this study was to uncover the value of LINC01711 as a prognostic biomarker and therapeutic target for GC and to further explore the underlying mechanism.

Materials and methods

Study subjects

This study was performed in full compliance with the ethical guidelines established by the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the Ethics Committee of the author’s institution before the study began (No. 2019162, dated 2019.03.05). A cohort of 150 GC patients was recruited from the author’s institution between 2019 and 2020. The enrollment criteria were defined as follows:

Patients histopathologically confirmed to have GC were enrolled.

Patients or their legal guardians who were fully informed about research procedures and signed the informed consent were enrolled.

Patients who had received no prior antitumor therapy were enrolled.

Patients with complete follow-up data and comprehensive medical records were enrolled.

Patients without serious complications were enrolled.

Patients who presented with no acute or chronic comorbidities that might confound the study outcomes were enrolled.

Female patients who were not pregnant or breastfeeding were enrolled.

Follow-up survey

Postoperative follow-up was conducted for all enrolled patients for a period of 3–60 months to evaluate both functional recovery and long-term survival outcomes. The study endpoints included disease recurrence, metastasis, and mortality attributable to GC.

Sample collection

The tumor and normal gastric tissues were obtained during the surgical resection. Collected tissues were histologically evaluated and confirmed by at least two pathologists to ensure diagnostic consensus. Following pathological verification, the tissues were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and subsequently stored at −80 °C.

Cell culture and transfection

In this study, human gastric epithelial cells (GES-1, SNL-304, SUNNCELL, China) and GC cells (AGS, SNL-103, SUNNCELL, China; MKN45, SNL-173, SUNNCELL, China; MKN74, SNL-176, SUNNCELL, China; HGC-27, SNL-104, SUNNCELL, China; and SNU-16, SNL-538, SUNNCELL, China) were chosen for testing LINC01711 expression characteristics in GC cells. Cells were cultured using Roswell Park Memorial Institute Medium (RPMI 1640, SNM-001B, SUNNCELL, China) containing 10 % fetal bovine serum (FBS, 164210, Pricella, China) and 1 % penicillin-streptomycin solution (PB180120, Pricella, China) at 37 °C in a 5 % CO2 incubator.

HGC-27 and SNU-16 cell lines were selected for further cell experiments because LINC01711 was the most up-regulated in the two types of cells. After seeding in 24-well plates, cells were cultured overnight in complete growth medium (RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10 % FBS). Following medium removal, the cells were transfected in Opti-MEM I medium (31985070, Biolead, China) using Lipofectamine 3000 (L3000001, Invitrogen, USA) for 6 h with the following constructs: hsa-miR-140-3p mimic (B01001, GenePharma, China), LINC01711-targeting small interfering RNA (si-LINC01711; A01001, GenePharma, China), hsa-miR-140-3p inhibitor (B03001, GenePharma, China), mimic NC (B04001, GenePharma, China), si-NC (A06001, GenePharma, China), and inhibitor NC (B04003, GenePharma, China). The transfection efficiency was detected via qRT-PCR.

Prediction and validation of LINC01711-hsa-miR-140-3p interaction

The potential miRNAs that interact with LINC01711 in GC were screened across multiple databases using the LncBook (https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/lncbook/), miRanda (http://www.bioinformatics.com.cn/local_miranda_miRNA_target_prediction_120; score ≥160, ΔG ≤ −25 kcal/mol), and starBase (http://starbase.sysu.edu.cn/index.php) databases. The DIANA bioinformatics suite was employed to investigate putative binding sites between LINC01711 and hsa-miR-140-3p.

To experimentally validate this interaction, wild-type (WT-LINC01711) and mutant (MUT-LINC01711) sequences of LINC01711 were cloned into the luciferase reporter plasmid.

HGC-27 and SNU-16 cells, cultured in RPMI 1640 medium with 10 % FBS, were plated in 48-well culture plates upon reaching 80 % confluence. The cells were then co-transfected with either WT-LINC01711 or MUT-LINC01711 constructs, along with a Renilla luciferase plasmid (for normalization; 11402ES60, YEASEN, China). At 24 h post-transfection, luciferase activity was measured using a Multiskan FC microplate reader (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) following the addition of a luciferase substrate. Firefly luciferase signals were normalized to Renilla luciferase fluorescence intensity to account for transfection efficiency.

Cell proliferation assay

HGC-27 and SNU-16 cell proliferation was tested using the CCK-8 assay. Following plating in 96-well culture plates, cell proliferation was monitored at 24 h intervals (0–72 h) by measuring the optical density at 450 nm (OD450). At each time point, cells were incubated with the CCK-8 reagent (C0038, Beyotime, China) for 2 h at 37 °C, followed by absorbance measurement at 450 nm.

Cell migration and invasion assay

Cell migration ability was examined using a Transwell chamber assay. The permeable membrane (FTW064-12Ins, Beyotime, China) was rehydrated with the serum-free medium at 37 °C for 30 min. Cells were serum-starved for 12 h, trypsinized, washed twice with PBS, and resuspended in serum-free medium. Then, the cell suspension was added to the upper chamber, while the lower chamber was filled with complete medium (RPMI 1640 medium containing 10 % FBS). Following a 24 h incubation, the upper membrane surface was washed with calcium-free PBS to remove non-migrated cells. Migrated cells were fixed with 4 % paraformaldehyde for 30 min, stained with 0.1 % crystal violet (20 min), and washed with PBS. Cells were counted under an inverted light microscope (Olympus, USA).

The invasive potential of cells was determined using the Transwell assay with membranes that were pre-coated with Matrigel. Matrigel (50 mg/L, 1:8 dilution; C0372-1 ml, Beyotime, China) was used to coat the upper chamber membrane. The subsequent steps were performed identically to the migration assay.

Total RNA extraction

RNA extraction was performed using TRIzol reagent (15596026CN, Invitrogen, USA).

Tissue RNA Extraction: Fresh tissue samples were minced into 1–3 mm fragments and homogenized in 1 mL of TRIzol reagent using a sterile pestle. Chloroform (C0761520275, Nanjing Reagent, China) was added to promote the isolation of RNA from the samples. The mixture was centrifuged, and the upper aqueous phase was mixed with isopropanol (C0690546005, Nanjing Reagent, China) to pellet RNA. The pellet was washed with 75 % ethanol (C0691560024, Nanjing Reagent, China), and the RNA was air-dried and resuspended in RNase-free water.

Cell RNA Extraction: The procedure for cell RNA extraction was identical to tissue RNA extraction, but omitted the step of grinding cells. Only RNA samples with OD260/280 ratio of 1.8–2.0 and concentration greater than 40 μg/mL were used for further study.

Real-time quantitative PCR

PrimeScript RT Master Mix kit (RR037Q, Takara, Japan) was used for the cDNA synthesis with 2 μg of the obtained RNA. MX3000P system (Stratagene, Germany) performed quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) with the following reaction parameters: initial denaturation: 94 °C for 3 min; denaturation: 94 °C for 20 s; annealing/extension: 62 °C for 40 s; amplification cycles: 40. Gene-specific primers for LINC01711 (forward 5′-GATCTGCTCCATGTCGTGTGATG-3′, reverse 5′-ACTGGCTGAGAACCACAGGTCT-3’; QH51305S, Beyotime, China) and hsa-miR-140-3p (forward 5′-GCGCGTACCACAGGGTAGAA-3′, reverse 5′-AGTGCAGGGTCCGAGGTATT-3’; QH77781S, Beyotime, China), as well as 0.3 μL of LINC01711/hsa-miR-140-3p cDNA were included in qRT-PCR. All samples were run in triplicate, and mean Ct values were determined for each experimental group. Relative expression levels were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method with appropriate normalization controls.

Statistical analysis

Multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression was used to assess the independent prognostic value of clinical characteristics (performed in SPSS). The Kaplan–Meier Plotter database, combined with the Kaplan–Meier survival curve analysis (in SPSS), was further used to explore the predictive value of LINC01711 for GC patient survival probability. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). All datasets underwent normality testing using the Shapiro–Wilk test (in SPSS) before statistical analysis. The independent-sample t-test (two groups, normally distributed data), Wilcoxon rank-sum test (two groups, non-normally distributed data), one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test (more than two groups, normally distributed data), and Kruskal–Wallis test with Dunnett’s test (more than two groups, non-normally distributed data) were performed in SPSS to test the differences of data between groups. The association between the expression of LINC01711 and hsa-miR-140-3p was assessed using the Pearson correlation coefficient analysis. The figures in this study were drawn using GraphPad Prism.

Results

The expression of LINC01711 in GC and its impact on GC patients

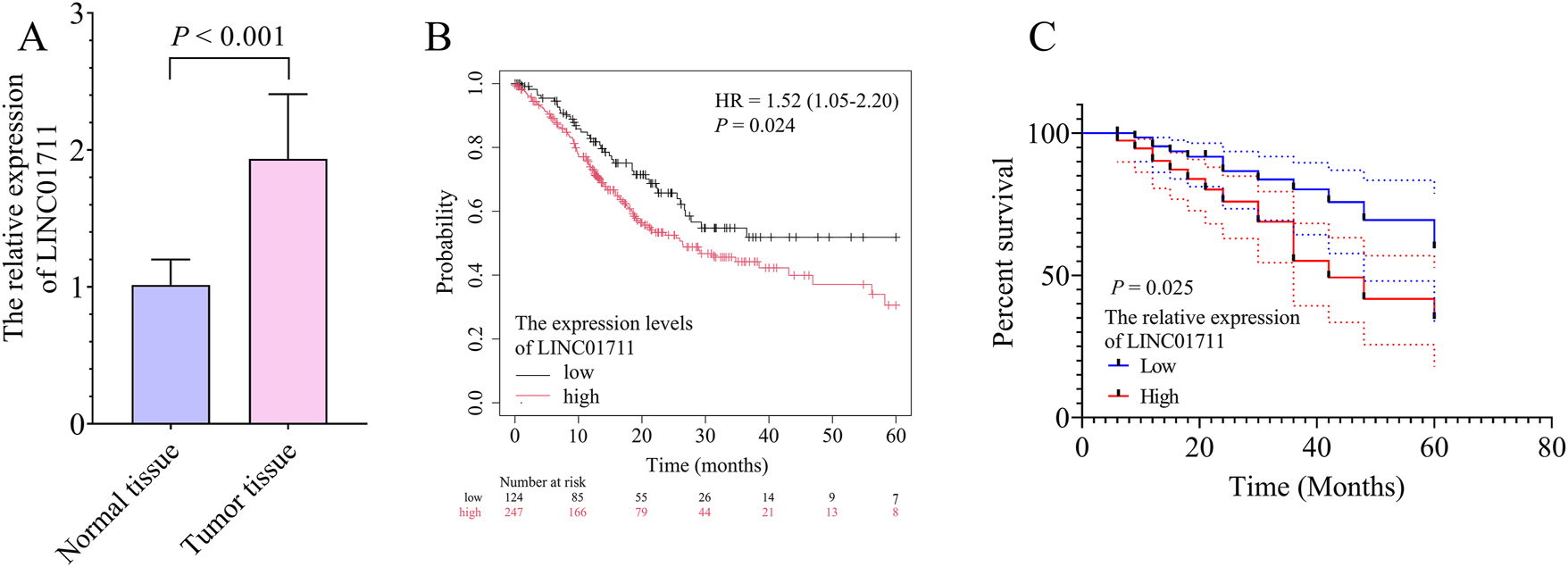

Compared with normal tissues, the expression of LINC01711 was upregulated in GC tissues (Figure 1A). A high LINC01711 expression level (≥1.93) was associated with advanced tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) stage (p = 0.016, Table 1), larger tumor size (p = 0.049, Table 1), and positive lymph node metastasis (p = 0.026, Table 1). Furthermore, compared with the low LINC01711 expression level, both the Kaplan–Meier Plotter database (Figure 1B, hazard ratio (HR): 1.52, 95 % confidence interval (CI): 1.05–2.20, p = 0.024) and Kaplan–Meier survival curve (Figure 1C, p = 0.025) showed a significant correlation between the high LINC01711 expression and a lower survival probability in GC patients.

The significance of LINC01711 expression for the survival probability of gastric cancer (GC) patients. A, the bar chart showed the expression levels of LINC01711 in normal and GC tumor tissues. B, the Kaplan–Meier plotter database demonstrated the association between LINC01711 expression levels and GC patient survival probability. C, the Kaplan–Meier survival curve showed the association between LINC01711 expression levels and GC patient survival probability in this study.

The association between LINC01711 expression level and clinical features in gastric carcinoma patients.

| Cases (n=150) | LINC01711 expression | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low (<1.93) | High (≥1.93) | |||

| Age (years) | 0.440 | |||

| <60 | 82 | 38 | 44 | |

| ≥60 | 68 | 36 | 32 | |

| Sex | 0.168 | |||

| Male | 93 | 42 | 51 | |

| Female | 57 | 32 | 25 | |

| TNM stage | 0.016 | |||

| I-II | 94 | 53 | 41 | |

| III | 56 | 21 | 35 | |

| Tumor size (cm) | 0.049 | |||

| <3 | 80 | 46 | 34 | |

| ≥3 | 70 | 28 | 42 | |

| Lymph node metastasis | 0.026 | |||

| Negative | 98 | 55 | 43 | |

| Positive | 52 | 19 | 33 | |

| Differentiation | 0.198 | |||

| Well/mode | 92 | 50 | 42 | |

| Poor | 58 | 24 | 34 | |

-

TNM, tumor-node-metastasis. p<0.05 is significant.

The Cox proportional hazards model further confirmed high LINC01711 expression as an independent risk factor for the low survival probability of GC patients (Table 2, HR: 2.446, 95 % CI: 1.108–5.399, p = 0.027). In addition, the TNM stage (Table 2, HR: 2.227, 95 % CI: 1.071–4.632, p = 0.032) and lymph node metastasis status (Table 2, HR: 2.064, 95 % CI: 1.036–4.111, p = 0.039) were also independent risk factors for the low survival probability of GC patients.

Association between clinical features and overall survival in gastric carcinoma patients.

| HR factor | 95 % CI | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| LINC01711 | 2.446 | 1.108–5.399 | 0.027 |

| Age | 1.623 | 0.828–3.179 | 0.158 |

| Sex | 1.486 | 0.715–3.089 | 0.288 |

| TNM stage | 2.227 | 1.071–4.632 | 0.032 |

| Differentiation | 1.580 | 0.812–3.076 | 0.178 |

| Lymph node metastasis | 2.064 | 1.036–4.111 | 0.039 |

| Tumor size | 1.449 | 0.720–2.915 | 0.299 |

-

CI, confidence interval; TNM, tumor-node-metastasis; HR, hazard ratio. p<0.05 is significant.

The miRNA that interacts with LINC01711 in GC

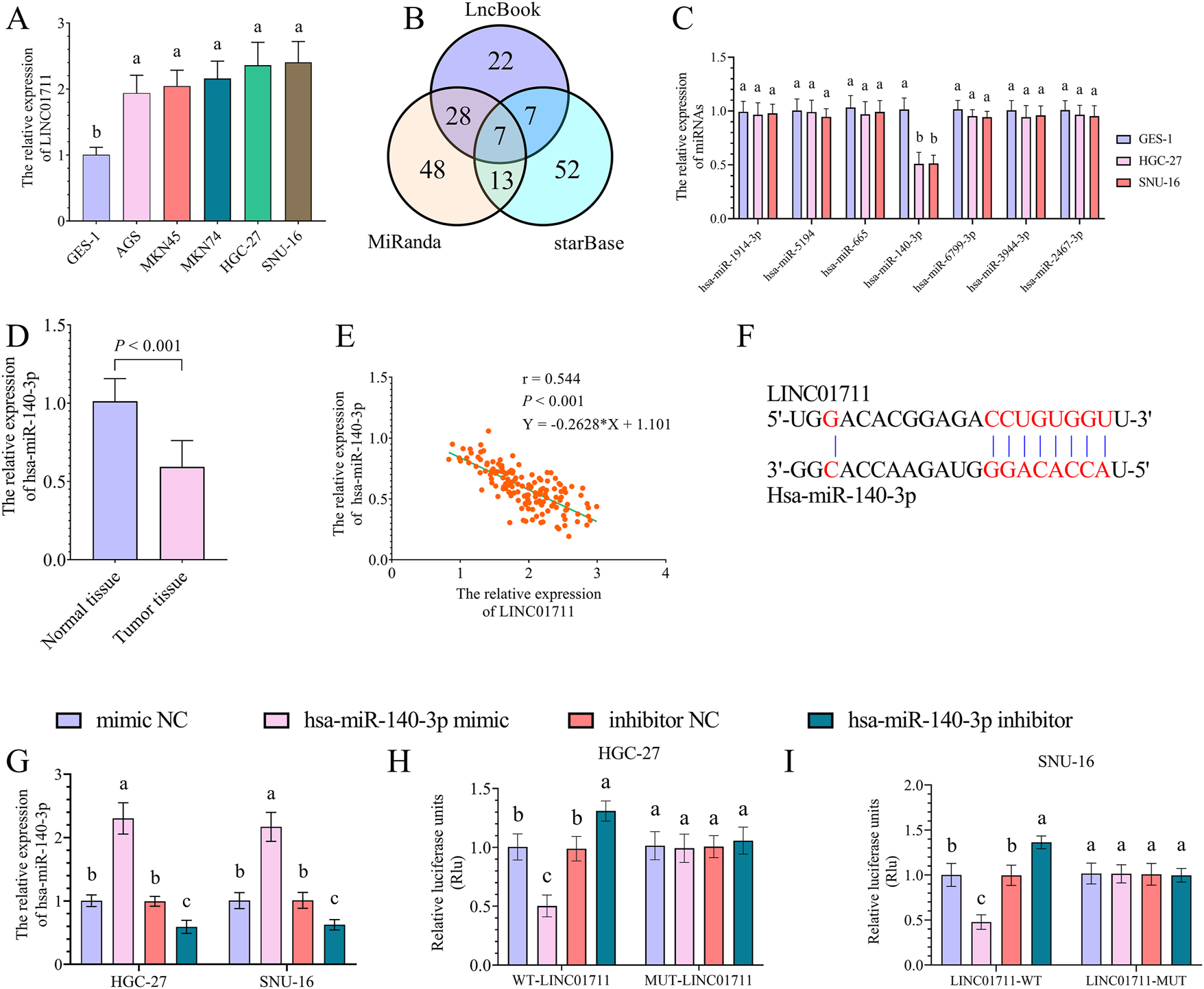

Compared with gastric epithelial cells, there was an upregulation of LINC01711 in GC cells (Figure 2A). The HGC-27 and SNU-16 cell lines were chosen for further cellular experiments as they showed the highest LINC01711 expression levels among all GC cell lines analyzed in this study (Figure 2A). To explore the miRNAs that interacted with LINC01711, the LncBook, miRanda, and starBase databases revealed 64, 96, and 79 potential miRNA interactions, respectively (Figure 2B). Intersection analysis of these datasets yielded seven common miRNAs, including hsa-miR-1914-3p, hsa-miR-5194, hsa-miR-665, hsa-miR-140-3p, hsa-miR-6799-3p, hsa-miR-3944-3p, and hsa-miR-2467-3p (Figure 2B and C). The characteristics of these seven miRNAs expression in GC cells showed that the expression of hsa-miR-140-3p was significantly downregulated in both HGC-27 and SNU-16 cells than in GES-1 cells (Figure 2C). Hsa-miR-140-3p has been proven to be an inhibitor of the progression of GC [12]. Therefore, this study further explored the association between LINC01711 and hsa-miR-140-3p, as well as the effect of the LINC01711/hsa-miR-140-3p on GC cell activities.

The target miRNA of LINC01711 in GC. A, the bar chart showed the expression levels of LINC01711 in gastric epithelial and GC cells. B, the Venn plot showed the number of LINC01711-targeted miRNAs due to the LncBook, miRanda, and starBase databases. C, the bar chart showed the expression levels of LINC01711-targeted miRNAs in gastric epithelial and GC cells. D, the bar chart showed the expression levels of hsa-miR-140-3p in normal and GC tumor tissues. E, Pearson’s correlation analysis showed a negative correlation between the expression of LINC01711 and hsa-miR-140-3p in GC tumor tissues. F, DIANA tools probed the binding site between LINC01711 and hsa-miR-140-3p. G, the bar chart showed the expression levels of hsa-miR-140-3p in hsa-miR-140-3p mimic or inhibitor transfected GC cells. H–I, dual luciferase assay showed the luciferase activity in WT-LINC01711 and MUT-LINC01711 groups with up- or downregulation of hsa-miR-140-3p in HGC-27 (H) and SNU-16 (I) cells. Different letters (a, b, c) represent significant differences (p < 0.05) from one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test or the kruskal–Wallis test with the Dunnett test.

The expression of hsa-miR-140-3p was downregulated in GC tumor tissue compared with normal tissues (Figure 2D) and was negatively correlated with the expression of LINC01711 (Figure 2E, r = −0.544, p<0.001). The molecular interaction interface of LINC01711 with hsa-miR-140-3p was investigated using the DIANA tools (Figure 2F). The LINC01711-hsa-miR-140-3p interaction was functionally validated by a dual-luciferase reporter assay. The transfection of hsa-miR-140-3p mimic and inhibitor significantly upregulated and downregulated hsa-miR-140-3p expression levels in both HGC-27 and SNU-16 cells, respectively (Figure 2G). In the WT-LINC01711 group, the upregulation of hsa-miR-140-3p led to a significant diminish in luciferase activity, while the downregulation of hsa-miR-140-3p led to a significant increase in luciferase activity (Figures 2H and I). However, in the MUT-LINC01711 group, changes in hsa-miR-140-3p expression did not affect luciferase activity.

Hsa-miR-140-3p mediated the effect of LINC01711 on GC cells

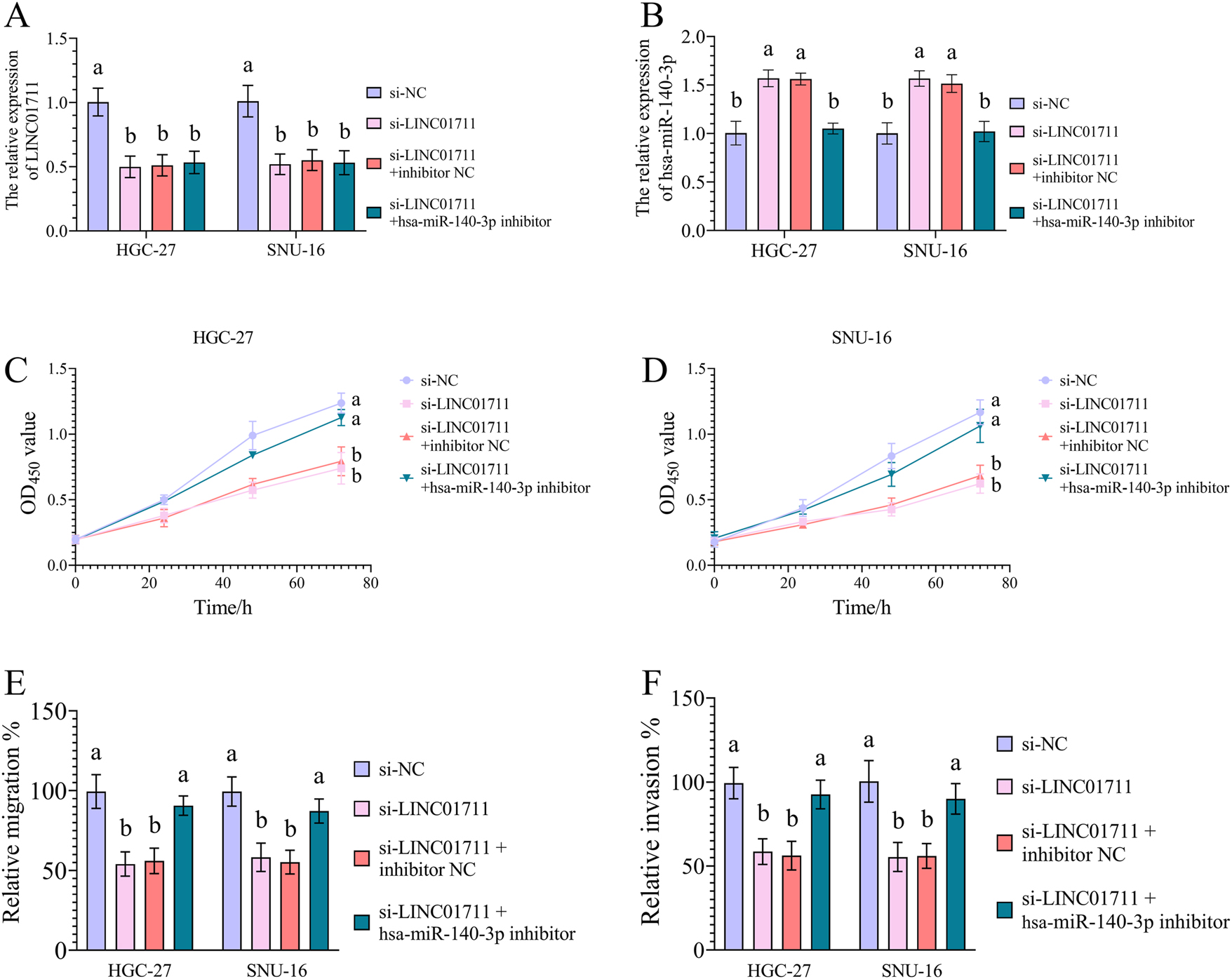

In this study, siRNA-mediated knockdown of LINC01711 resulted in significant downregulation in both HGC-27 and SNU-16 cells (Figure 3A). In contrast, hsa-miR-140-3p inhibition showed no significant effect on LINC01711 expression levels in either cell line (Figure 3A). The downregulation of LINC01711 led to an upregulation of hsa-miR-140-3p (Figure 3B). However, the upregulated hsa-miR-140-3p expression was further suppressed by transfection with the hsa-miR-140-3p inhibitor (Figure 3B).

The effect of LINC01711/hsa-miR-140-3p axis on GC cell activities. A, the rescue experiments showed that hsa-miR-140-3p could not regulate LINC01711 expression in GC cells. B, the rescue experiments showed that LINC01711 downregulated hsa-miR-140-3p expression in GC cells. C–F, the rescue experiments showed that LINC01711 promoted GC cell proliferation (C, D), migration (E), and invasion (F) by downregulating hsa-miR-140-3p. Different letters (a, b) represent significant differences (p < 0.05) from one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test or the kruskal–Wallis test with the Dunnett test.

For the GC cell activities, the downregulation of LINC01711 inhibited cell activities in both HGC-27 and SNU-16 cells, which included cell proliferation (Figure 3C and D), migration (Figure 3E), and invasion (Figure 3F) abilities. Notably, hsa-miR-140-3p knockdown attenuated the anti-proliferative (Figures 3C and D), anti-migratory (Figure 3E), and anti-invasive (Figure 3F) effects mediated by LINC01711 silencing in GC cells, suggesting hsa-miR-140-3p acts as a crucial downstream effector of LINC01711.

Discussions

GC remains its position as the fifth most prevalent malignancy worldwide and ranks third in global cancer mortality owing to the late diagnosis [13]. The emerging cancer therapeutic strategies, including targeted therapy, immunotherapy, and radiation therapy, have shown promising efficacy for treating GC [14], [15], [16]. Among the new therapeutic strategies, the development of targeted therapy and immunotherapy requires more detailed information on the biomolecular interactions in GC tumor cells [16], 17]. Therefore, it was necessary for researchers to explore biomolecules involved in the development of GC tumor progression. LncRNAs have been functionally characterized as master regulators of gene expression networks and protein activity, with growing recognition of their clinical relevance as prognostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets in oncology [4], 18]. This study also found that lncRNA LINC01711 showed a great prognostic value in GC patients. The result was consistent with previous studies, which have proven that LINC01711 was responsible for the GC progression through the epigenetic regulation of cholesterol metabolism via histone modifications [6]. Emerging evidence indicates that LINC01711 plays an important role not only in GC but also contributes to the pathogenesis of multiple malignancies, including esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) [19], cutaneous melanoma (CM) [20] and breast cancer (BC) [21]. This study demonstrated that LINC01711 upregulation significantly correlated with advanced TNM stage, larger tumor diameter, and positive lymph node metastasis in GC, suggesting its potential in contributing to the GC tumor growth and metastasis. These findings highlight the clinical relevance of LINC01711 as a prognostic indicator and its involvement in GC progression.

The way LINC01711 contributes to the aggravation of cancers includes modifying tumor cell metabolism and activities by interacting with miRNAs [19], 21]. This study identified a direct interaction between hsa-miR-140-3p and LINC01711 in GC, with LINC01711 exerting a suppressive effect on hsa-miR-140-3p expression. The mechanism of the interaction between miRNA and lncRNA includes several modes of regulation, such as lncRNAs acting as miRNA sponges, lncRNAs competitively binding to mRNAs along with miRNAs, miRNAs mediating lncRNA degradation, and lncRNAs serving as precursors for miRNA biogenesis [7], 22]. When lncRNA acts as the sponge for an miRNA, it binds to miRNA through complementary base pairing of miRNA recognition elements (MREs), leading to the downregulation of the miRNA [7], 23]. This indicates that LINC01711 sponges hsa-miR-140-3p in GC in this study. Notably, hsa-miR-140-3p is a multifaceted regulator known to modulate key cellular processes, including proliferation, apoptosis, cellular senescence, and inflammatory responses [24]. On account of its regulatory effect on cell activities, hsa-miR-140-3p becomes a modulator of tumor aggravation. In GC, hsa-miR-140-3p functioned as a tumor suppressor by regulating B-cell lymphoma-2 (BCL2)/coiled-coil myosin-like BCL2-interacting protein (BECN1)-dependent autophagy [12]. Furthermore, hsa-miR-140-3p-mediated small nucleolar host gene 12 (SNHG12) downregulation impaired Human antigen R (HuR) nuclear translocation and subsequent family with sequence similarity 83 member B (FAM83B) transcriptional activation, collectively contributing to the inhibition of GC progression [25]. This study uncovered the essential regulatory relationship between LINC01711 and hsa-miR-140-3p. The LINC01711/hsa-miR-140-3p regulatory axis might be one of the mechanisms for LINC01711 influencing GC progression.

To validate the role of the LINC01711/hsa-miR-140-3p axis in GC progression, cell experiments were conducted in this study using the GC cell lines HGC-27 and SNU-16 [26]. The results demonstrated that hsa-miR-140-3p mediated the promotive effects of LINC01711 on GC cell proliferation, migration, and invasion, which means the LINC01711/hsa-miR-140-3p axis drives GC tumor growth and metastasis [27], [28], [29]. The results explain why the LINC01711 remains a significant prognostic value in GC. It has been reported that hsa-miR-140-3p affects tumor cell activities by regulating the expression levels of genes that are involved in cell cycle regulation and tumorigenesis, such as forkhead box protein Q1 (FOXO1) and mitogen-activated protein kinase 1 (MAPK1) [30], 31]. Therefore, this study speculates that the reason why hsa-miR-140-3p acted as a mediator of LINC01711 in influencing GC cell activities was that hsa-miR-140-3p could modulate the expression of tumor development-related genes in GC. The LINC01711/hsa-miR-140-3p axis showed strong potential in the therapy of GC. Modulation of the expression levels of LINC01711 and hsa-miR-140-3p may help control tumor aggressiveness in GC.

The investigation of lncRNAs and miRNAs as diagnostic and therapeutic targets represents a prominent area of biomedical research [32], 33]. This study demonstrated that examining serum LINC01711 could be an efficient method to diagnose GC. Moreover, current strategies for lncRNA knockdown primarily involve: designing antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) to complementarily bind to the target lncRNA [34], 35]; designing small interfering RNAs (siRNAs/shRNAs) to degrade the lncRNA or block its function [35]; and editing lncRNA gene through CRISPR-Cas9 [35], 36]. This study further demonstrated that targeting LINC01711 through ASO (ASO-LINC01711), siRNA (si-LINC01711), or CRISPR-Cas9-based gene editing may hold therapeutic potential for GC therapy. For the miRNA, the main methods that can increase miRNA levels are designing miRNA mimics and designing suitable vectors to deliver miRNAs to target organs and tissues [35], 37]. In GC, the administration of hsa-miR-140-3p mimics and the development of tumor tissue-specific delivery systems for hsa-miR-140-3p may have clinical benefits in GC management. In addition to LINC01711/hsa-miR-140-3p, emerging evidence highlights the roles of other lncRNAs and miRNAs in GC pathogenesis. For example, lncRNA NEAT1 modulates GC cell proliferation and metastasis by sponging hsa-miR-500a-3p [38]. LncRNA TDRG1 is a promoter of GC aggressiveness by sponging hsa-miR-873-5p [39]. These findings demonstrated the importance of systematically screening for dysregulated ncRNAs that significantly influence GC progression. Further investigation of their diagnostic potential and therapeutic applications in GC could be meaningful for controlling the disease progression and improving patient survival. For the two biomolecules investigated in this study, it was shown broad therapeutic potential across multiple cancer types. LINC01711 exhibits significant regulatory effects on breast cancer (BC) and glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) progression [21], 40]. Hsa-miR-140-3p is an inhibitor of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), colorectal cancer (CC), and BC [40], [41], [42]. Exploring the molecular mechanisms underlying their cancer-modulating activities, particularly their tissue-specific regulatory networks and downstream effectors, could yield valuable insights for developing novel therapeutic strategies for many cancers.

However, despite its valuable insights into GC prognosis and treatment, this study still has limitations. This study only investigated the influence of the LINC01711/hsa-miR-140-3p axis on the GC progression without exploring downstream genes regulated by hsa-miR-140-3p. Identification of hsa-miR-140-3p targets in GC would deepen our knowledge of GC pathogenesis and provide information necessary for investigating targeted treatment approaches for the disease. Moreover, since the results of this study implicated LINC01711 as a ceRNA of hsa-miR-140-3p, further investigation into the genes regulated by the LINC01711/hsa-miR-140-3p axis would confirm that the phenotype is consistent with a ceRNA mechanism [22]. In addition, this study focused only on the interaction between LINC01711 and hsa-miR-140-3p. Considering that an lncRNA typically functions as a sponge for various types of miRNAs [43], we acknowledge that a comprehensive investigation of the complete ceRNA network involving LINC01711 in GC with advanced bioinformatics analyses based on GEO and TCGA databases, and systematic experimental validation including crosslinking and immunoprecipitation (CLIP), fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), and high-throughput sequencing, could provide crucial information on understanding GC pathogenesis and managing the disease. Future studies need to be conducted to address this deficiency.

Conclusions

In this study, the upregulation of LINC01711 was identified as a prognostic biomarker for GC. LINC01711 could downregulate the expression of hsa-miR-140-3p in GC. Hsa-miR-140-3p mediated the effects of LINC01711 on GC tumor cell activities.

-

Research ethics: The study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the Ethics Committee of the Seventh Medical Center of Chinese PLA General Hospital before the study began (No. 2019162, on 2019.03.05).

-

Informed consent: The written informed consent has been obtained from the participants involved.

-

Author contributions: Conceptualization, W.S., J.W., Y.S., X.W. and C.W., L.L.; Data curation, W.S., J.W., Y.S., X.W. and C.W., L.L.; Formal analysis, W.S., J.W., Y.S., X.W. and C.W.; Funding acquisition, C.W.; Investigation, Y.S. and X.W.; Methodology, Y.S., X.W. and C.W.; Project administration, C.W., L.L.; Resources, Y.S. and X.W.; Software, W.S., J.W., Y.S. and X.W.; Supervision, C.W., L.L.; Validation, Y.S. and X.W.; Visualization, W.S., J.W., Y.S. and X.W.; Roles/Writing—original draft, Y.S. and X.W.; Writing— review and editing, W.S., J.W., C.W., L.L.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: Artificial intelligence (AI) and/or machine learning tools were not used in the writing of this article.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

-

Research funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

-

Data availability: The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

1. Waldum, HL, Fossmark, R. Types of gastric carcinomas. Int J Mol Sci 2018;19:4109. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms19124109.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

2. Hoshi, H. Management of gastric adenocarcinoma for general surgeons. Surg Clin 2020;100:523–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.suc.2020.02.004.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

3. Smyth, EC, Nilsson, M, Grabsch, HI, van Grieken, NC, Lordick, F. Gastric cancer. Lancet 2020;396:635–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(20)31288-5.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

4. Statello, L, Guo, CJ, Chen, LL, Huarte, M. Gene regulation by long non-coding RNAs and its biological functions. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2021;22:96–118. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41580-020-00315-9.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

5. Badowski, C, He, B, Garmire, LX. Blood-derived lncRNAs as biomarkers for cancer diagnosis: the good, the bad and the beauty. npj Precis Oncol 2022;6:40. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41698-022-00283-7.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

6. Yue, B, Chen, J, Bao, T, Zhang, Y, Yang, L, Zhang, Z, et al.. Chromosomal copy number amplification-driven Linc01711 contributes to gastric cancer progression through histone modification-mediated reprogramming of cholesterol metabolism. Gastric Cancer 2024;27:308–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10120-023-01464-4.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

7. Paraskevopoulou, MD, Hatzigeorgiou, AG. Analyzing MiRNA-LncRNA interactions. Methods Mol Biol 2016;1402:271–86. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-3378-5_21.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

8. Cannell, IG, Kong, YW, Bushell, M. How do microRNAs regulate gene expression? Biochem Soc Trans 2008;36:1224–31. https://doi.org/10.1042/bst0361224.Search in Google Scholar

9. Jin, M, Zhang, GW, Shan, CL, Zhang, H, Wang, ZG, Liu, SQ, et al.. Up-regulation of miRNA-105 inhibits the progression of gastric carcinoma by directly targeting SOX9. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2019;23:3779–89. https://doi.org/10.26355/eurrev_201905_17804.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

10. Takagi, T, Iio, A, Nakagawa, Y, Naoe, T, Tanigawa, N, Akao, Y. Decreased expression of microRNA-143 and -145 in human gastric cancers. Oncology 2009;77:12–21. https://doi.org/10.1159/000218166.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

11. Shen, R, Pan, S, Qi, S, Lin, X, Cheng, S. Epigenetic repression of microRNA-129-2 leads to overexpression of SOX4 in gastric cancer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2010;394:1047–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.03.121.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

12. Chen, J, Cai, S, Gu, T, Song, F, Xue, Y, Sun, D. MiR-140-3p impedes gastric cancer progression and metastasis by regulating BCL2/BECN1-mediated autophagy. OncoTargets Ther 2021;14:2879–92. https://doi.org/10.2147/ott.s299234.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

13. López, MJ, Carbajal, J, Alfaro, AL, Saravia, LG, Zanabria, D, Araujo, JM, et al.. Characteristics of gastric cancer around the world. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2023;181:103841. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.critrevonc.2022.103841.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

14. Pasechnikov, V, Chukov, S, Fedorov, E, Kikuste, I, Leja, M. Gastric cancer: prevention, screening and early diagnosis. World J Gastroenterol 2014;20:13842–62. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i38.13842.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

15. Digklia, A, Wagner, AD. Advanced gastric cancer: current treatment landscape and future perspectives. World J Gastroenterol 2016;22:2403–14. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v22.i8.2403.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

16. Song, Z, Wu, Y, Yang, J, Yang, D, Fang, X. Progress in the treatment of advanced gastric cancer. Tumour Biol 2017;39:1010428317714626. https://doi.org/10.1177/1010428317714626.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

17. Guan, WL, He, Y, Xu, RH. Gastric cancer treatment: recent progress and future perspectives. J Hematol Oncol 2023;16:57. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13045-023-01451-3.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

18. Bhan, A, Soleimani, M, Mandal, SS. Long noncoding RNA and cancer: a new paradigm. Cancer Res 2017;77:3965–81. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.can-16-2634.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

19. Xu, ML, Liu, TC, Dong, FX, Meng, LX, Ling, AX, Liu, S. Exosomal lncRNA LINC01711 facilitates metastasis of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma via the miR-326/FSCN1 axis. Aging (Albany NY) 2021;13:19776–88. https://doi.org/10.18632/aging.203389.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

20. Zhang, M, Zuo, Y, Guo, J, Yang, L, Wang, Y, Tan, M, et al.. A novel signature for predicting prognosis and immune landscape in cutaneous melanoma based on anoikis-related long non-coding RNAs. Sci Rep 2023;13:16332. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-39837-5.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

21. Tao, S, Gao, Y, Wang, X, Wu, C, Zhang, Y, Zhu, H, et al.. CAF-derived exosomal LINC01711 promotes breast cancer progression by activating the miR-4510/NELFE axis and enhancing glycolysis. FASEB J 2025;39:e70471. https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.202402024rrr.Search in Google Scholar

22. Ma, B, Wang, S, Wu, W, Shan, P, Chen, Y, Meng, J, et al.. Mechanisms of circRNA/lncRNA-miRNA interactions and applications in disease and drug research. Biomed Pharmacother 2023;162:114672. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2023.114672.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

23. Salmena, L, Poliseno, L, Tay, Y, Kats, L, Pandolfi, PP. A ceRNA hypothesis: the Rosetta stone of a hidden RNA language? Cell 2011;146:353–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2011.07.014.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

24. Toury, L, Frankel, D, Airault, C, Magdinier, F, Roll, P, Kaspi, E. miR-140-5p and miR-140-3p: key actors in aging-related diseases? Int J Mol Sci 2022;23:11439. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms231911439.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

25. Wang, Z, Chen, K, Li, D, Chen, M, Li, A, Wang, J. miR-140-3p is involved in the occurrence and metastasis of gastric cancer by regulating the stability of FAM83B. Cancer Cell Int 2021;21:537. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12935-021-02245-8.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

26. Liu, K, Liu, B, Zhang, Y, Wu, Q, Zhong, M, Shang, L, et al.. Building an ensemble learning model for gastric cancer cell line classification via rapid raman spectroscopy. Comput Struct Biotechnol J 2022;21:802–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csbj.2022.12.050.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

27. Gaglia, G, Kabraji, S, Rammos, D, Dai, Y, Verma, A, Wang, S, et al.. Temporal and spatial topography of cell proliferation in cancer. Nat Cell Biol 2022;24:316–26. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41556-022-00860-9.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

28. Krakhmal, NV, Zavyalova, MV, Denisov, EV, Vtorushin, SV, Perelmuter, VM. Cancer invasion: patterns and mechanisms. Acta Naturae 2015;7:17–28. https://doi.org/10.32607/20758251-2015-7-2-17-28.Search in Google Scholar

29. Novikov, NM, Zolotaryova, SY, Gautreau, AM, Denisov, EV. Mutational drivers of cancer cell migration and invasion. Br J Cancer 2021;124:102–14. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41416-020-01149-0.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

30. Wang, Y, Chen, J, Wang, X, Wang, K. miR-140-3p inhibits bladder cancer cell proliferation and invasion by targeting FOXQ1. Aging (Albany NY) 2020;12:20366–79. https://doi.org/10.18632/aging.103828.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

31. Wang, J, Zhu, M, Zhou, X, Wang, T, Xi, Y, Jing, Z, et al.. MiR-140-3p inhibits natural killer cytotoxicity to human ovarian cancer via targeting MAPK1. J Biosci 2020;45:66. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12038-020-00036-3.Search in Google Scholar

32. Arun, G, Diermeier, SD, Spector, DL. Therapeutic targeting of long non-coding RNAs in cancer. Trends Mol Med 2018;24:257–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molmed.2018.01.001.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

33. Li, Z, Rana, TM. Therapeutic targeting of microRNAs: current status and future challenges. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2014;13:622–38. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrd4359.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

34. Chen, Y, Li, Z, Chen, X, Zhang, S. Long non-coding RNAs: from disease code to drug role. Acta Pharm Sin B 2021;11:340–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsb.2020.10.001.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

35. Winkle, M, El-Daly, SM, Fabbri, M, Calin, GA. Noncoding RNA therapeutics—challenges and potential solutions. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2021;20:629–51. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41573-021-00219-z.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

36. Xiao, G, Yao, J, Kong, D, Ye, C, Chen, R, Li, L, et al.. The long noncoding RNA TTTY15, which is located on the Y chromosome, promotes prostate cancer progression by sponging let-7. Eur Urol 2019;76:315–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2018.11.012.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

37. Traber, GM, Yu, AM. RNAi-based therapeutics and novel RNA bioengineering technologies. J Pharmacol Exp Therapeut 2023;384:133–54. https://doi.org/10.1124/jpet.122.001234.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

38. Zhou, Y, Sha, Z, Yang, Y, Wu, S, Chen, H. lncRNA NEAT1 regulates gastric carcinoma cell proliferation, invasion and apoptosis via the miR-500a-3p/XBP-1 axis. Mol Med Rep 2021;24:503. https://doi.org/10.3892/mmr.2021.12142.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

39. Ma, Y, Xu, XL, Huang, HG, Li, YF, Li, ZG. LncRNA TDRG1 promotes the aggressiveness of gastric carcinoma through regulating miR-873-5p/HDGF axis. Biomed Pharmacother 2020;121:109425. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2019.109425.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

40. Shree, B, Sengar, S, Tripathi, S, Sharma, V. LINC01711 promotes transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) induced invasion in glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) by acting as a competing endogenous RNA for miR-34a and promoting ZEB1 expression. Neurosci Lett 2023;792:136937. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neulet.2022.136937.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

41. Jiang, W, Li, T, Wang, J, Jiao, R, Shi, X, Huang, X, et al.. miR-140-3p suppresses cell growth and induces apoptosis in colorectal cancer by targeting PD-L1. OncoTargets Ther 2019;12:10275–85. https://doi.org/10.2147/ott.s226465.Search in Google Scholar

42. Zhou, Y, Wang, B, Wang, Y, Chen, G, Lian, Q, Wang, H. miR-140-3p inhibits breast cancer proliferation and migration by directly regulating the expression of tripartite motif 28. Oncol Lett 2019;17:3835–41. https://doi.org/10.3892/ol.2019.10038.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

43. Su, K, Wang, N, Shao, Q, Liu, H, Zhao, B, Ma, S. The role of a ceRNA regulatory network based on lncRNA MALAT1 site in cancer progression. Biomed Pharmacother 2021;137:111389. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2021.111389.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.