Abstract

Background

Poly-β-hydroxybutyrate (PHB) is the most important and versatile class of biodegradable polymers used successfully in the medical, agricultural and industrial field. Idea is to find the novel isolate for degradation of biodegradable plastics that can enhance the bioremediation.

Materials and methods

Thirty-one PHB and PHB depolymerase enzyme producing isolates out of 80 mesophilic bacteria from Lucknow region were further screened for PHB degradation capability by secreting extracellular PHB depolymerase enzyme in minimal salt media supplemented with PHB (0.15%). Various biodegradable plastic films were tested by soil burial method for weight loss determination.

Result

37.3% weight loss has been observed in PHB films when buried under the soil for 45 days in the presence of a novel PHB degrader identified as Paenibacillus alvei PHB28 by 16S rRNA sequencing (GenBank accession number KX886342). These Gram-negative, spore-forming, thermotolerant bacteria produce maximum PHB depolymerase (5.03 U/mL) at 45°C, pH 8.0, with 0.15% substrate concentration when incubated for 96 h with starch (0.1%) and yeast extract (0.01%) as an additional nutrient supplements.

Conclusion

To the best of our knowledge this is the first report of PHB depolymerase production by P. alvei PHB28 which may contribute successfully to combat plastic pollution and to sustain the green environment.

Öz

Amaç

Poli-β-Hidroksibutirat (PHB), tıbbi, tarımsal ve endüstriyel alanda başarıyla kullanılan, biyolojik olarak çözünebilen polimerlerin en önemli ve çok çeşitliliğe sahip sınıfıdır. Amaç, biyobozunur plastiklerin bozunması için biyoremediasyonu arttıracak yeni bir izolat bulmaktır.

Gereç ve Yöntem

Lucknow bölgesinden 80 mezofilik bakteriden elde edilen otuz bir PHB ve PHB depolimeraz enzimi üreten izolat, PHB (%0.15) ile desteklenmiş minimal tuz ortamında hücre dışına PHB depolimeraz enzimi salgılayarak PHB’yi bozundurma kabiliyeti açısından tarandı. Çeşitli biyobozunur plastik filmler, kilo kaybı tespiti için toprağa gömme metodu ile test edildi.

Bulgular

PHB filmleri 16S rRNA dizilemesine göre Paenibacillus alvei PHB28 olarak tanımlanan yeni bir PHB indirgeyici varlığında (GenBank erişim numarası KX886342) toprağın altında 45 gün süreyle gömüldüğünde %37.3 ağırlık kaybı gözlemlenmiştir. Bu Gram-negatif, spor oluşturan, termotolerant bakteriler, 45°C’de pH 8.0’de, % 0.15 substrat konsantrasyonu ile, ek besin takviyesi olarak nişasta (% 0.1) ve maya ekstraktı (%96) ile inkübe edildiğinde maksimum PHB depolimeraz (5.03 U/mL) üretmektedir.

Sonuç

Bildiğimiz kadarıyla bu, plastik kirliliğe karşı mücadeleye ve yeşil çevreyi sürdürmeye başarıyla katkıda bulunabilecek olan PHB depolimerazın Paenibacillus alvei PHB28 tarafından üretimine dair ilk rapordur.

Introduction

The intractable non-biodegradable synthetic waste [1] have led to the replacement of petrochemical-derived polyester with the production of biodegradable and eco-friendly plastic polymers. Biodegradable but water-insoluble polyesters such as poly-hydroxyalkanoate (PHA) can be originated by living microorganisms with the supplement of organic carbon source in rich amounts as an energy reservoir and intracellular storage granule. Among numerous PHA components, poly-β-hydroxybutyrate (PHB) have been investigated with a high degree of interest for commercial applications due to their unusual properties. These insoluble, semi-crystalline, denatured granules are degraded by extracellular PHB depolymerase enzymes [2].

PHB is fragmented into monomer in nutrient-limiting condition by the effect of PHB depolymerase [3]. PHB degrading microorganisms have been isolated earlier from diverse ecological aspects such as soil, water, hot spring, sea water, sewage sludge and waste effluent and agro-waste [3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8]. PHB degrading activity of PHB depolymerase has been recently reported from Streptomyces ascomycinicus, Stenotrophomonas sp. RZS7, Streptomyces sp. MG and Paucimonas lemoignei [2], [9], [10], [11]. Despite this fact, degradation of biopolymers by the microorganisms in the environment is initiated by the surface erosion and/or adsorption on the polymer surface. The rate of biodegradation is highly influenced by several changing environmental factors such as temperature, pH, moisture, alkalinity, availability of carbon and nitrogen source and heavy metal ions within the soil.

The purpose of the present study was to screen and isolate novel potential PHB depolymerase producing bacteria from waste, polluted soil that is able to perform efficient biodegradation of biodegradable plastics. The study was further extended for its production optimization input that can meet the industrial demand for enzyme utilization.

Materials and methods

Isolation of poly β-hydroxybutyrate(PHB) producing bacteria

Collection of sample

Samples were collected from different plastic polluted enriched ecological niches of Lucknow region (India) viz potato storage soil, river water, and river soil, sewage sludge, wastewater, decomposing vegetable soil. The samples were collected from 2 to 4 cm depth of the soil with a sterile spatula in sterile poly-bags while the water samples were collected in falcon tubes. The collected samples were stored at −20°C. The soil and water samples were serially diluted in sterile distilled water, followed by plating on nutrient agar medium with 1% glucose. The plates were then incubated at 35±2°C for 2–7 days and the colonies with distinct morphological features were selected for further studies. For rapid detection and isolation of PHB producing bacteria, 0.02% alcohol solution of Sudan black B staining viable colony method was used [12].

Source of poly β-hydroxybutyrate (PHB) polymer

The PHB powder used in this study was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Chemicals, Germany. The molecular weight of PHB was 470 KDa. All the experiments were performed using PHB powder.

Preparation of PHB film

PHB film was prepared by dissolving 0.3 g of PHB powder in 30 mL of chloroform with magnetic stirring for 20 min and fancied into a film by pouring into clean sterilized glass petriplate of 10 cm diameter and then chloroform was vaporized slowly. The complete plastination resulted in the formation of polymer films and allowed to stand for a further 24 h until their weights had established in the air [13].

Soil burial method for isolation of PHB degrading bacteria

The weight of each experimental piece of polymer films Polypropylene (P1), Polyethylene (P2, P3), Polystyrene (P4) PHB (P5), before and after treatment is calculated from the change in the weight for each plastic film. To screen positive strains, aliphatic PHB polyester films were buried in soil for different incubation time period (15 days, 30 days and 45 days) at ambient temperature (35–37°C). The polymer film of about 5.0×6.0 cm with an initial weight of 0.1 g was buried in pots containing about 150 g of garden soil at room temperature amended with a mineral solution to maintain the availability of mineral salts and the moisture content was maintained around 60%. The films were hanged with thread for easy follow up.

After different incubation periods, the pre-weighed films were removed from the soil medium, brushed softly, washed with distilled water several times to clean off the soil particles then dried at room temperature [13];

W1=initial weight of films, W2=final weight of buried films.

The polymer film showing maximum weight loss after doing this experiment was further analyzed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM).

The surface morphology of soil buried film via scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

The surface properties of soil buried film were investigated via SEM. Polymer film, which had been in the soil for the different incubation period were primarily fixed in 4% (v/v) glutaraldehyde in 100 mM sodium cacodylate buffer, pH 7.2. Following fixation in glutaraldehyde, the polymer was post-fixed in 20 g/L aqueous osmium tetroxide and examined under SEM after dried to critical point [14].

Screening of PHB depolymerase producing bacteria

Extracellular degradation of PHB on solid medium by PHB depolymerase

The extracellular degradation of PHB by isolated strain on solid surface medium was done with clear zone method [15]. The minimal salt media (MSM) of the following composition was prepared in g/L: NaCl-10, NH4Cl-1, CaCl2-0.015, yeast extract-0.1 K2HPO4-1.6, KH2PO4-0.2, MgSO4-0.123 supplemented with 0.15% PHB as carbon source and 6 mL of a trace element solution prepared as per the following concentration per liter (H3PO4-1.96 mg, FeSO4-56 mg, ZnSO4-29 mg, MnSO4-22 mg, CuSO4-2.5 mg, Co(NO3)2-3 mg, H3BO3-6 mg) [16]. PHB suspension was prepared by sonicating PHB powder in the mineral salt medium for 15 min in an ultrasonic water bath [17]. The solid plate was prepared with the addition of 2.0% agar in the PHB suspension [18]. The plate was incubated for 96–144 h to screen out the extracellular PHB degrading bacteria from the PHB producing positive isolates by the formation of the clear zone.

Identification of bacterial isolate

The morphological identification of isolated bacterium was done by growing on MSM. The various morphological, biochemical and physiological characteristics of the isolate was determined by using Bergey’s Manual of Determinative Bacteriology [19]. The identity was further confirmed by 16S rRNA sequencing.

Phylogenetic analysis by 16S rRNA sequencing

The 16S rRNA sequence analysis of isolate was carried out from Eurofins Genomics India Pvt. Ltd, Bangalore, India. Amplification was performed by using the forward primer sequence 5′ AGAGTTTGATCMTGGCTCAG 3′. The amplified sequence was analyzed with the nBLAST run and the evolutionary tree was further computed by using neighbor-joining method with Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis software version 7.0.21 (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov).

PHB depolymerase enzyme assay

For the determination of PHB depolymerase activity of the crude or purified enzyme, a stable suspension of PHB in 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer solution, pH 7.0 was prepared by sonication at 20 kHz for 10 min [20]. The assay was performed by the modified method of Jendrossek et al. [18]. The standard reaction mixture contained 0.9 mL of 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.0) suspended with PHB powder (150 μg/mL). The reaction was started by the addition of the crude enzyme (0.1 mL) and was incubated for 20 min at 30°C. The activity was arrested by the addition of 0.1N HCl solution to the reaction mixture. The enzyme activity was measured as a decrease in PHB turbidity by spectrophotometer at 650 nm. One unit of PHB depolymerase activity was defined as the amount of enzyme that was required to decrease the OD650 by 0.001 mL/min [9].

Optimization of PHB depolymerase production from P. alvei strain PHB 28

Effect of the incubation period and growth kinetics

The optimum incubation period for PHB depolymerase enzyme production by P. alvei strain PHB 28 was determined by inoculating the MS medium (0.1 mL of inoculated growth medium with CFU of 2×107/mL) for the different time interval (24–192 h) at 120 rpm. The enzyme activity was assayed after every 24 h of incubation for the next consecutive 8 days by standard assay procedure.

Effect of incubation temperature and pH

The temperature optima of the production medium were measured at different incubation temperatures such as 15°, 25°, 35°, 45° and 55°C for 96 h. The pH optima of the production medium were obtained by incubating the inoculated PHB containing MS media with different pH range (4.0–12.0) on a rotatory shaker at optimum growth temperature for the optimum incubation period. The activity was measured as per the standard assay procedure.

Effect of carbon/nitrogen sources on enzyme activity

To optimize the effect of carbon and nitrogen sources on enzyme production, optimized media was supplied with different carbon sources by replacing PHB as glucose, fructose, lactose, mannitol, starch and sucrose with 0.1% concentration in optimized parameters. For effect of inorganic (ammonium sulfate, ammonium nitrate, ammonium chloride) and organic nitrogen sources (urea, peptone and tryptone), enzyme production was optimized at 0.01% concentration in MS medium by replacing yeast extract (in control). The activity was measured as per the standard assay procedure.

Effect of substrate concentration on enzyme activity

Different concentration of PHB substrate was incorporated in the optimized medium ranging from 0.05 to 0.25% for continuous 192 h to optimize enzyme production from P. alvei strain PHB28. The activity was measured as per the standard assay procedure in all pre-optimized conditions.

Effect of heavy metal ions on PHB depolymerase production by P. alvei PHB28

To study the effect of heavy metal ions on the PHB depolymerase production from P. alvei PHB28, various metal ions (Mg+2, Zn+2, Cu2+, Hg2+, Co2+, Fe+3, K+) in their chloride form were assayed in the concentration of 10 mM for 96 h of incubation. The activity was measured as per the standard assay procedure in all pre-optimized conditions.

Results and discussion

PHB producing microbes

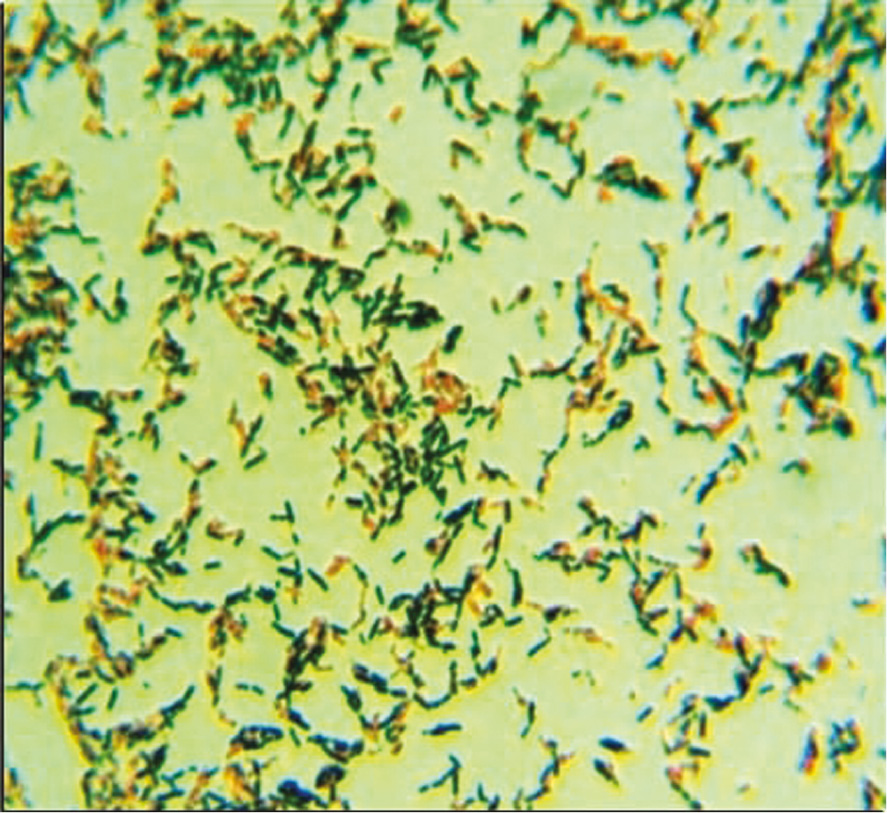

Among the soil samples collected from different locations, maximum PHB producing bacteria were observed in river soil and wastewater (Table 1). Total 80 bacterial isolates were screened for natural production of PHB. On the basis of black-blue coloration, when stained with Sudan black B (preliminary screening agent for lipophilic compounds), 26 positive isolates with distinct morphology on nutrient agar were randomly selected for having the capability of extracellular degradation on PHB enriched minimal salt medium. Colonies unable to incorporate the Sudan black B appeared white, while PHB producers appeared bluish black (Figure 1). As reported by Getachew and Woldesenbet [21] a potent PHB producer Bacillus sp., was isolated at 37°C from municipal sewage [22]. Hungund et al. [23] has reported the isolation of PHB producing Paenibacillus durus BV-1 from oil mil soil. Only one report is available showing PHB synthesis from P. alvei [24], while here for the first time P. alvei PHB28 is reported as PHB depolymerase producing strain possessing PHB synthesizing ability as well.

Screening of PHB producing microbes in the different soil sample.

| S. no. | Sample location site | CFU/mL | No. of bacteria isolated | No. of positive isolates | PHB producing bacteria (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Potato storage soil | 1.3×109 | 12 | 4 | 33 |

| 2 | River water | 1.8×109 | 15 | 5 | 30 |

| 3 | River soil | 2.0×109 | 20 | 5 | 40 |

| 4 | Sewage sludge | 1.4×109 | 10 | 3 | 30 |

| 5 | Waste water | 2.4×109 | 8 | 2 | 40 |

| 6 | Field soil | 1.5×109 | 15 | 7 | 20 |

Bold values shows the best values which were taken to explain the result.

Positive bacterial colonies showing intracellular PHB granules (bluish-black) stained with Sudan black B dye.

Weight loss determination of the soil buried plastic films

The weight of the test piece before and after treatment is calculated from the change in the weight for each plastic film (Table 2). The weight loss degradability for PHB (P5) film was found to be maximum (37.3%) at the end of treatment.

Weight loss (%) of plastic film buried in soil for an incubation period of 45 days.

| Type of polymer film | Weight of film (g) | Weight loss degradability (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Before treatment | After treatment | ||

| P1(Polypropylene) | 0.312±0.001 | 0.304±0.000 | 12.56 |

| P2 (Polyethylene) | 0.305±0.001 | 0.298±0.003 | 18.3 |

| P3 (Polyethylene) | 0.214±0.005 | 0.195±0.001 | 19.4 |

| P4 (Polystyrene) | 0.133±0.002 | 0.130±0.002 | 14.6 |

| P5 (Polyhydroxybutyrate) | 0.284±0.001 | 0.242±0.002 | 37.3 |

Bold values shows the best values which were taken to explain the result.

Surface morphology of soil buried film by SEM

The incubation of PHB film in the soil for degradation at different time period was microscopically observed using SEM. In the first 15 days of degradation under soil, the surface was observed to be smooth with no pits and grooves (Figure 2B) as compared to the control (Figure 2A) and then progressively became rough with the markedly larger grooves (Figure 2C,D) as the exposure of the film to the soil for biodegradation was increased (~45 days) [6], [9].

Scanning electron micrographs of the PHB films.

(A) Control and soil buried, (B) after 15 days, (C) after 30 days and (D) after 45 days.

Wen and Lu [25] also reported microbial degradation of PHB films buried in soil was enhanced with surface erosion process and 15% degradation was achieved with exposure of soil for 60 days when observed under SEM.

Screening of PHB depolymerase producing bacteria

From the soil burial treatment method, five potent PHB producing microbes were isolated by applying the same process of Sudan black B staining. Amongst 31 positive PHB producers (26 obtained from different locations and five from soil buried polymer film), the varying degree of PHB degradation was achieved with the colonies growing on solid plates with PHB as the sole source of carbon.

Primary screening was done on the basis of zone diameter on PHB solid plate after the incubation period of 7 days at 35±2°C, from which five strains were selected. Secondary screening was determined on the basis of PHB depolymerase enzyme activity of isolates (Table 3) in minimal medium under standard enzyme assay procedure, from which one potential isolate was further analyzed [9].

PHB depolymerase production after 72 h of incubation.

| S. no. | Culture no. | Source of isolation | Renaming | Diameter of hydrolysis zone (mm) | Enzyme assay (U/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | 2 | Waste water | PHB2 | 1.5 | 2.982 |

| 2. | 18 | Waste water | PHB18 | 0.5 | 0.220 |

| 3. | 26 | Sewage sludge | PHB26 | 0.6 | 0.882 |

| 4. | 28 | Potato soil | PHB28 | 2.0 | 4.01 |

| 5. | 67 | Potato soil | PHB67 | 0.25 | 0.280 |

Bold values shows the best values which were taken to explain the result.

Characterization of bacterial isolate

Five potential isolates were characterized by morphological, biochemical and physiological observation according to the Bergey’s Manual of Determinative Bacteriology (Table 4). Based on maximum PHB depolymerase enzyme production, PHB28 was chosen for further study.

Identification of bacterial strain

DNA sequence alignment

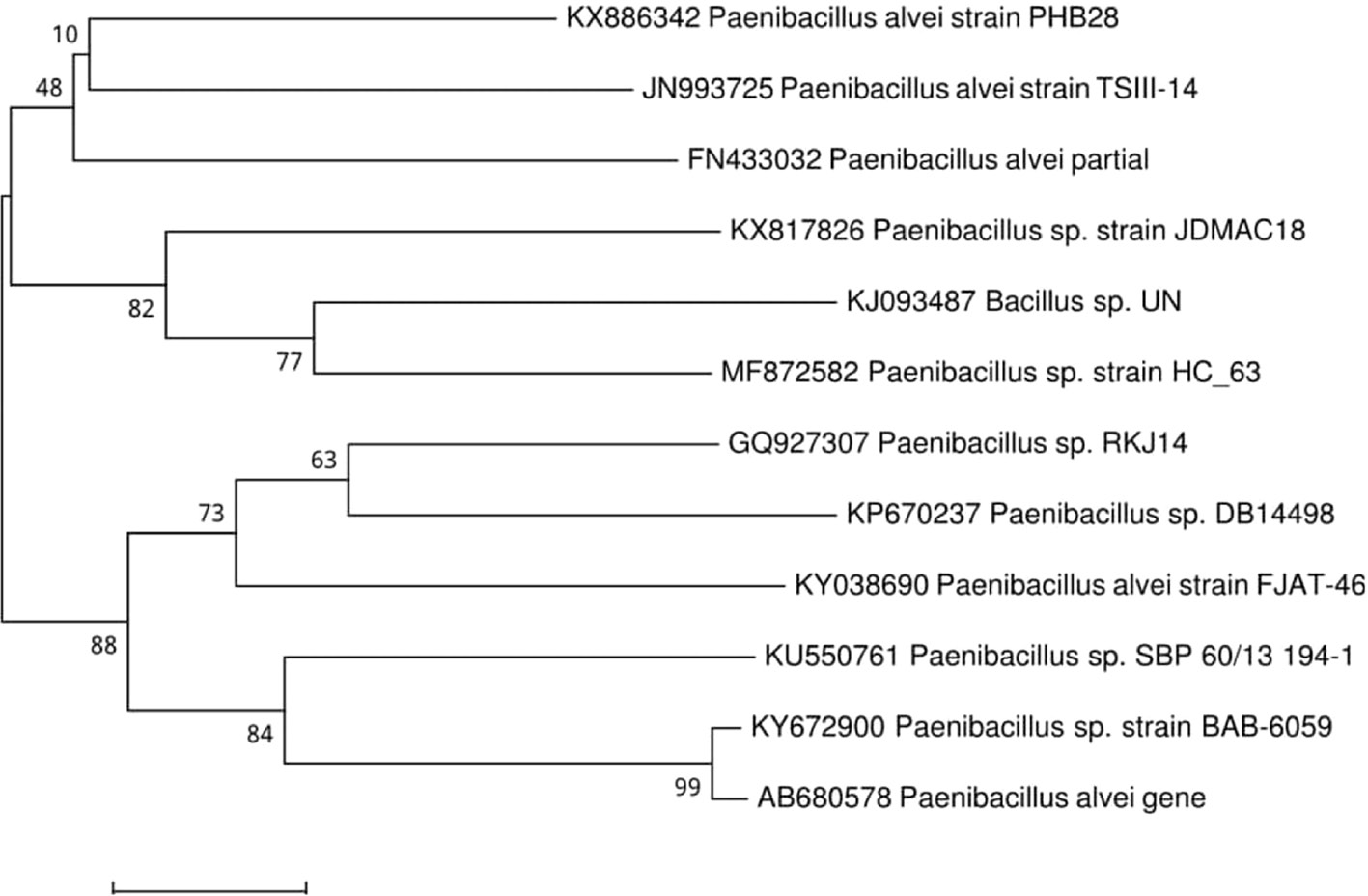

Partial homologous 16S rRNA sequences were analyzed using BLAST algorithm search tool in GenBank (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi). BLAST showed that the isolate PHB 28 which is of 614 bp has maximum homology identity (99%) with P. alvei strain FJAT-46015 (KY038690) with nucleotide base count of Adenine:163, Guanine:187, Cytisine:152, Thymine:131 through direct submission at NCBI-BLAST with an assigned GenBank accession number KX886342. Phylogenetic relationship and molecular evolution of the identified isolate was inferred by Neighbor-Joining analysis as presented in Figure 3.

Phylogenetic tree showing the homology of strain PHB 28 with P. alvei.

Optimization of PHB depolymerase production by Paenibacillus alvei strain PHB28

Effect of incubation period

The conversion of PHB (0.15% in the turbid medium) into its monomer/oligomer under the suitable growth conditions was found to be maximum (3.39 U/mL) with 96 h of incubation as shown in Figure 4A.

Optimization of PHB depolymerase production by Paenibacillus alvei strain PHB28.

(A) Effect of incubation time (B) Effect of incubation temperature (C) Effect of pH.

Biochemical characterization of PHB depolymerase producing positive isolate.

| Characteristics | PHB2 | PHB18 | PHB26 | PHB28 | PHB67 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Configuration | Entire | Flat | Undulate | Entire | Entire |

| Shape | Irregular | Irregular | Irregular | Circular | Circular |

| Surface | Smooth | Mucoid | Rough | Smooth | Mucoid |

| Pigment color | White | Orange | Greenish | Light green | Yellowish |

| Colony size (diameter in mm) | 3–4 | 2–3 | 2–4 | 1–2 | 1–2 |

| Gram’s staining | + | + | − | − | + |

| Spore formation | − | − | + | + | + |

| Biochemical tests | |||||

| Indole production | − | − | − | + | + |

| Catalase test | − | + | + | + | + |

| Citrate utilization | − | − | + | − | − |

| Starch hydrolysis | − | − | − | + | − |

| H2S production | − | − | − | − | − |

| Voges-praskeur | − | − | − | + | − |

| Methyl red | − | − | − | − | − |

| Acid production from | |||||

| Glucose | − | + | + | + | − |

| Lactose | − | − | − | + | − |

| Fructose | − | − | − | + | − |

| Mannitol | − | − | + | − | − |

| Physiological tests | |||||

| Growth at temp. | 25–40°C | 35–40°C | 25–40°C | 30–45°C | 25–35°C |

| Growth at NaCl (%) | 2–8 | 2–8 | 4–8 | 2–8 | 2–6 |

| Growth at pH | 6–7 | 6–9 | 7–9 | 6–8 | 6–8 |

| Aerobic/anaerobic condition | Anaerobic | Aerobic | Facultative anaerobic | Strictly aerobic | Aerobic |

| Agitation required for growth | + | + | + | + | + |

Effect of incubation temperature

PHB depolymerase production from P. alvei strain PHB28 was optimized in the temperature range of 15°C–65°C with 96 h of incubation period. Maximum production of PHB depolymerase was achieved at 45°C (3.92 U/mL) after which a sharp decline (1.03 U/mL) in the enzyme production was obtained with the rise in temperature (Figure 4B). Temperature optima results suggest that PHB28 is a thermotolerant strain. Aly et al. [26] found similar results where also 45°C is the most suitable temperature for PHB depolymerase enzyme production from Streptomyces lydicus MM10. A few numbers of thermotolerant (≥40°C) PHB degrading microbial strain (Aspergillus fumigatus) has been reported [27].

Effect of pH

Among different pH range (4.0–12.0), maximum degrading activity was obtained at pH 8.0 (4.76 U/mL) as shown in Figure 4C. Loss of degrading activity was observed by a sharp decline in the pH range of (10.0–12.0) as shown in the graph. Lodhi et al. [27] have reported the maximum PHB depolymerase production at pH 7.0 from A. fumigatus.

Effect of carbon sources

Among additional carbon sources, maximum hydrolytic activity was observed in the presence of Starch (4.88 U/mL) after 96 h of incubation at 45°C, pH 8.0 as shown in Figure 5A, while in the presence of Sucrose, Mannitol, Fructose, Lactose and Glucose, the PHB depolymerase activity was 1.36, 1.28, 1.08, 0.85 and 2.98 U/mL, respectively.

Optimization of PHB depolymerase production by Paenibacillus alvei strain PHB28.

(A) Effect of carbon sources, (B) effect of nitrogen sources, (C) effect of substrate concentration and (D) effect of metal ions.

Effect of nitrogen sources

Among various organic and inorganic nitrogen sources, highest activity was exhibited with yeast extract (5.03 U/mL) followed by peptone (3.23 U/mL) under the optimized condition of temperature (45°C) and pH (8.0) for 96 h of the incubation as shown in Figure 5B. Supplementation of ammonium sulfate (2.69 U/mL) and ammonium nitrate (1.62 U/mL), was found not significant for enzyme production whereas urea proved to be a potent inhibitor for PHB depolymerase production as activity goes down to just 0.55 U/mL as compared to control (3.16 U/mL) having PHB as a carbon source. On the contrary of our result, Vigneswari et al. [28] have reported that urea was found best for enzyme production from Acidovorax sp. DP5.

Effect of substrate concentration

It was observed that the activity of an enzyme is in direct proportion with the concentration of PHB, thereby, best production (3.97 U/mL) was achieved at 0.15% of PHB in minimal media (Figure 5C). A higher or lower concentration is markedly inhibiting or reducing the activity of PHB depolymerase. However, Aly et al. [26] observed the maximum production of PHB depolymerase at 0.3% after 24 h of incubation with S. lydicus MM10. Similar to our results, maximum production of PHB depolymerase was reported by with 0.1% of substrate concentration from Thermus thermophilus HB8 after 24 h of incubation [29].

Wani et al. [9] have reported the optimum yield of PHB depolymerase from Stenotrophomonas sp. RZS7 with five days of incubation period at 37°C and at pH 6.0. The two PHB depolymerase from Pseudomonas mendocina PHAase I and PHAase II have been reported previously [30]. Several thermophilic bacterial strains have been isolated for PHB depolymerase production. The presence of carbon sources other than PHB also effects or inhibits the PHB depolymerase production [6], [26]. The optimum production of PHB depolymerase was achieved with lactose while in the current study, the best PHB depolymerase activity was observed with starch in addition to PHB.

Effect of metal ions

The effect of monovalent (K+), divalent (Mg+2, Zn+2, Cu2+, Hg2+, Co2+) and trivalent (Fe+3) heavy metal ions on PHB depolymerase production was observed at 10 mM concentration under the optimized parameters of 45°C, pH 8.0, 0.1% starch, 0.01% yeast extract in enzyme production media for 96 h. The enhanced activity was observed (Figure 5D) only with Co+2 (4.30 U/mL) as compared to control (4.03 U/mL) while Mg+2 (3.84 U/mL) had no significant change over the activity while rest of the metal ions found as an inhibitor for production of the enzyme like Zn2+, Fe+3 and Hg+2 showed 3.13 U/mL, 0.77 U/mL and 0.88 U/mL activity, respectively. In support of our results, Bhatt et al. [31] also found the enhanced activity of PHB depolymerase with Mg+2, Ca+2 and Co+2 in a concentration of 5 mM while Hg+2 was proved as a potent inhibitor where activity goes down to zero. However, 85% and 81% of enzyme inactivation were observed with Fe+3 and Cu+2. Thus it can be summarized that PHB depolymerase (PHB degrading activity) producing isolate is thermostable (45°C), and an increased activity was observed in the presence of starch remarks the additional requirement of the carbon source to enhance the activity of PHB depolymerase. Further, it will be significant to characterize the amino acid sequences essential for the functioning of PHB depolymerase enzyme. Up to best of our knowledge, this is the first report of PHB degradation and PHB depolymerase production simultaneously from P. alvei PHB28 strain.

Funding source: Department of Science and Technology

Award Identifier / Grant number: IU/R&D/2017-MCN000217

Funding statement: Authors are grateful to the Department of Science and Technology (DST-SERB) for providing financial support and Integral University for providing the necessary infrastructure and manuscript communication number IU/R&D/2017-MCN000217.

Conflict of interest: All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Declarations of interest: None

References

1. Barnes DK, Galgani F, Thompson RC, Barlaz M. Accumulation and fragmentation of plastic debris in global environments. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2009;364:1985–98.10.1098/rstb.2008.0205Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

2. García-Hidalgo J, Hormigo D, Arroyo M, de la Mata I. Novel extracellular PHB depolymerase from Streptomyces ascomycinicus: PHB copolymers degradation in acidic conditions. PLoS One 2013;8:e71699.10.1371/journal.pone.0071699Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

3. Kim HJ, Nam JS, Bae KS, Rhee YH. Characterization of an extracellular medium-chain-length poly (3-hydroxyalkanoate) depolymerase from Streptomyces sp. KJ-72. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 2003;83:183–9.10.1023/A:1023395527073Search in Google Scholar

4. Tokiwa Y, Calabia BP. Review degradation of microbial polyesters. Biotechnol Lett 2004;26:1181–9.10.1023/B:BILE.0000036599.15302.e5Search in Google Scholar

5. Takaku H, Kimoto A, Kodaira S, Nashimoto M, Takagi M. Isolation of a Gram-positive poly (3-hydroxybutyrate)(PHB)-degrading bacterium from compost, and cloning and characterization of a gene encoding PHB depolymerase of Bacillus megaterium N-18-25-9. FEMS Microbiol Lett 2006;264:152–9.10.1111/j.1574-6968.2006.00448.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

6. Shah A, Hasan F, Hameed A, Ahmed S. A novel poly (3-hydroxybutyrate)-degrading Streptoverticillium kashmirense AF1 isolated from soil and purification of PHB-depolymerase. Acta Biol Hung 2008;59:489–99.10.1556/ABiol.59.2008.4.9Search in Google Scholar PubMed

7. Song JH, Murphy RJ, Narayan R, Davies GB. Biodegradable and compostable alternatives to conventional plastics. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2009;364:2127–39.10.1098/rstb.2008.0289Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

8. Nielsen C, Rahman A, Rehman AU, Walsh MK, Miller CD. Food waste conversion to microbial polyhydroxyalkanoates. Microb Biotechnol 2017;10:1338–52.10.1111/1751-7915.12776Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

9. Wani SJ, Shaikh SS, Tabassum B, Thakur R, Gulati A, Sayyed RZ. Stenotrophomonas sp. RZS 7, a novel PHB degrader isolated from plastic contaminated soil in Shahada, Maharashtra, Western India. 3 Biotech 2016;6:179.10.1007/s13205-016-0477-8Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

10. Calabia BP, Tokiwa Y. A novel PHB depolymerase from a thermophilic Streptomyces sp. Biotechnol Lett 2006;28:383–8.10.1007/s10529-005-6063-5Search in Google Scholar PubMed

11. Jendrossek D, Hermawan S, Subedi B, Papageorgiou AC. Biochemical analysis and structure determination of Paucimonas lemoignei poly- (3-hydroxybutyrate PHB) depolymerase PhaZ7 muteins reveal the PHB binding site and details of substrate–enzyme interactions. Mol Microbiol 2013;90:649–64.10.1111/mmi.12391Search in Google Scholar PubMed

12. Bhuwal AK, Singh G, Aggarwal NK, Goyal V, Yadav A. Isolation and screening of polyhydroxyalkanoates producing bacteria from pulp, paper, and cardboard industry wastes. Int J Biomater 2013;2013:1–10.10.1155/2013/752821Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

13. Gouda MK, Swellam AE, Omar SH. Biodegradation of synthetic polyesters (BTA and PCL) with natural flora in soil burial and pure cultures under ambient temperature. Res J Environ Earth Sci 2012;4:325–33.Search in Google Scholar

14. Altaee N, El-Hiti GA, Fahdil A, Sudesh K, Yousif E. Biodegradation of different formulations of polyhydroxybutyrate films in soil. SpringerPlus 2016;5:762.10.1186/s40064-016-2480-2Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

15. Wang Z, Gao J, Li L, Jiang H. Purification and characterization of an extracellular poly (3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate) depolymerase from Acidovorax sp. HB01. World J Microbiol Biotechnol 2012;28:2395–402.10.1007/s11274-012-1048-8Search in Google Scholar PubMed

16. Pantazaki AA, Tambaka MG, Langlois V, Guerin P, Kyriakidis DA. Polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) biosynthesis in Thermus thermophilus: purification and biochemical properties of PHA synthase. Mol Cell Biochem 2003;254:173–83.10.1023/A:1027373100955Search in Google Scholar

17. Nadhman A, Hasan F, Shah AA. Production and characterization of poly (3-hyroxybutyrate) depolymerases from Aspergillus sp. isolated from soil that could degrade poly (3-hydroxybutyrate). IJB 2015;7:25–8.10.12692/ijb/7.2.25-28Search in Google Scholar

18. Jendrossek D, Knoke I, Habibian RB, Steinbüchel A, Schlegel HG. Degradation of poly (3-hydroxybutyrate), PHB, by bacteria and purification of a novel PHB depolymerase from Comamonas sp. J Environ Polym Degrad 1993;1:53–63.10.1007/BF01457653Search in Google Scholar

19. Hoseinabadi A, Rasooli I, Taran M. Isolation and identification of poly β-hydroxybutyrate over-producing bacteria and optimization of production medium. Jundishapur J Microbiol 2015;8:1–10.10.5812/jjm.16965v2Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

20. Ghanem NB, Mabrouk ME, Sabry SA, El-Badan DE. Degradation of polyesters by a novel marine Nocardiopsis aegyptia sp. nov.: application of Plackett-Burman experimental design for the improvement of PHB depolymerase activity. J Gen Appl Microbiol 2005;51:151–8.10.2323/jgam.51.151Search in Google Scholar PubMed

21. Getachew A, Woldesenbet F. Production of biodegradable plastic by polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB) accumulating bacteria using low cost agricultural waste material. BMC Res Notes 2016;9:509.10.1186/s13104-016-2321-ySearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

22. Reddy SV, Thirumala M, Mahmood SK. Production of PHB and P (3HB-co-3HV) biopolymers by Bacillus megaterium strain OU303A isolated from municipal sewage sludge. World J Microbiol Biotechnol 2009;25:391–7.10.1007/s11274-008-9903-3Search in Google Scholar

23. Hungund B, Shyama VS, Patwardhan P, Saleh AM. Production of polyhydroxy alkanoate from Paenibacillus durus BV-1 isolated from oil mill soil. J Microb Biochem Technol 2013;5:013–7.10.4172/1948-5948.1000092Search in Google Scholar

24. Boyandin AN, Prudnikova SV, Filipenko ML, Khrapov EA, Vasil’ev AD, Volova TG. Biodegradation of polyhydroxyalkanoates by soil microbial communities of different structures and detection of PHA degrading microorganisms. Appl Biochem Microbiol 2012;48:28–36.10.1134/S0003683812010024Search in Google Scholar

25. Wen X, Lu X. Microbial degradation of poly-(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-4-hydroxybutyrate) in soil. J Polym Environ 2012;20:381–7.10.1007/s10924-011-0387-0Search in Google Scholar

26. Aly MM, Tork S, Qari HA, Al-Seeni MN. Poly-hydroxy butyrate depolymerase from Streptomyces lydicus MM10, Isolated from Wastewater Sample. IJAB 2015;17:891–900.10.17957/IJAB/15.0023Search in Google Scholar

27. Lodhi A, Hasan F, Abdul Z, Hameed A, Faisal S, Shah A. Optimization of culture conditions for the production of poly 3-hydroxybutyrate depolymerase from newly isolated Aspergillus fumigatus from soil. Pak J Bot 2011;432:1361–2.Search in Google Scholar

28. Vigneswari S, Lee TS, Bhubalan K, Amirul AA. Extracellular polyhydroxyalkanoate depolymerase by Acidovorax sp. DP5. Enzyme Res 2015;2015:1–8.10.1155/2015/212159Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

29. Papaneophytou CP, Pantazaki AA, Kyriakidis DA. An extracellular polyhydroxybutyrate depolymerase in Thermus thermophilus HB8. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2009;83:659–68.10.1007/s00253-008-1842-2Search in Google Scholar PubMed

30. Mao H, Jiang H, Su T, Wang Z. Purification and characterization of two extracellular polyhydroxyalkanoate depolymerases from Pseudomonas mendocina. Biotechnol Lett 2013;35:1919–24.10.1007/s10529-013-1288-1Search in Google Scholar PubMed

31. Bhatt R, Patel KC, Trivedi U. Purification and properties of extracellular poly (3-hydroxybutyrate) depolymerase produced by Aspergillus fumigatus 202. J Polym Environ 2010;18:141–7.10.1007/s10924-010-0176-1Search in Google Scholar

©2019 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Short Communication

- Acetone-water mixture is a competent solvent to extract phenolics and antioxidants from four organs of Eucalyptus camaldulensis

- Research Articles

- Proteases from Calotropis gigantea stem, leaf and calli as milk coagulant source

- A new method to quantify atmospheric Poaceae pollen DNA based on the trnT-F cpDNA region

- Expression of a functional recombinant vascular endothelial growth factor 165 (VEGF165) in Arabidopsis thaliana

- Computational exploration of antiviral activity of phytochemicals against NS2B/NS3 proteases from dengue virus

- Investigation of antioxidant, cytotoxic, tyrosinase inhibitory activities, and phenolic profiles of green, white, and black teas

- DFR and PAL gene transcription and their correlation with anthocyanin accumulation in Rhodomyrtus tomentosa (Aiton.) Hassk.

- Comparison of phenolic profiles and antioxidant activity of three Ornithogalum L. species

- Increasing the fermentation efficiency of Lactobacillus paracasei ssp. paracasei MIUG BL6 in a rye flour sourdough

- Determination of chemical composition, antibacterial and antioxidant properties of products obtained from carob and honey locust

- Chitinolytic Bacillus subtilis Ege-B-1.19 as a biocontrol agent against mycotoxigenic and phytopathogenic fungi

- Recycling fish skin for utilization in food industry as an effective emulsifier and foam stabilizing agent

- A novel, thermotolerant, extracellular PHB depolymerase producer Paenibacillus alvei PHB28 for bioremediation of biodegradable plastics

- Post-transcriptional regulation of miRNA-15a and miRNA-15b on VEGFR gene and deer antler cell proliferation

- Comparison of pendimethalin binding properties of serum albumins from various mammalian species

- Crocin (active constituent of saffron) improves CCl4-induced liver damage by modulating oxidative stress in rats

- Time dependent change of ethanol consumption biomarkers, ethyl glucuronide and ethyl sulphate, after single dose ethanol intake

- GC-MS analysis and biological activities of Thymus vulgaris and Mentha arvensis essential oil

- Immobilization and some application of α-amylase purified from Rhizoctonia solani AG-4 strain ZB-34

- Letter to the Editor

- Molecular crosstalk between Hog1 and calcium/CaM signaling

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Short Communication

- Acetone-water mixture is a competent solvent to extract phenolics and antioxidants from four organs of Eucalyptus camaldulensis

- Research Articles

- Proteases from Calotropis gigantea stem, leaf and calli as milk coagulant source

- A new method to quantify atmospheric Poaceae pollen DNA based on the trnT-F cpDNA region

- Expression of a functional recombinant vascular endothelial growth factor 165 (VEGF165) in Arabidopsis thaliana

- Computational exploration of antiviral activity of phytochemicals against NS2B/NS3 proteases from dengue virus

- Investigation of antioxidant, cytotoxic, tyrosinase inhibitory activities, and phenolic profiles of green, white, and black teas

- DFR and PAL gene transcription and their correlation with anthocyanin accumulation in Rhodomyrtus tomentosa (Aiton.) Hassk.

- Comparison of phenolic profiles and antioxidant activity of three Ornithogalum L. species

- Increasing the fermentation efficiency of Lactobacillus paracasei ssp. paracasei MIUG BL6 in a rye flour sourdough

- Determination of chemical composition, antibacterial and antioxidant properties of products obtained from carob and honey locust

- Chitinolytic Bacillus subtilis Ege-B-1.19 as a biocontrol agent against mycotoxigenic and phytopathogenic fungi

- Recycling fish skin for utilization in food industry as an effective emulsifier and foam stabilizing agent

- A novel, thermotolerant, extracellular PHB depolymerase producer Paenibacillus alvei PHB28 for bioremediation of biodegradable plastics

- Post-transcriptional regulation of miRNA-15a and miRNA-15b on VEGFR gene and deer antler cell proliferation

- Comparison of pendimethalin binding properties of serum albumins from various mammalian species

- Crocin (active constituent of saffron) improves CCl4-induced liver damage by modulating oxidative stress in rats

- Time dependent change of ethanol consumption biomarkers, ethyl glucuronide and ethyl sulphate, after single dose ethanol intake

- GC-MS analysis and biological activities of Thymus vulgaris and Mentha arvensis essential oil

- Immobilization and some application of α-amylase purified from Rhizoctonia solani AG-4 strain ZB-34

- Letter to the Editor

- Molecular crosstalk between Hog1 and calcium/CaM signaling