Can and Should the New Third-Party Litigation Financing Come to Class Actions?

-

Brian T. Fitzpatrick

Abstract

In the United States, there has been tremendous growth in a form of third-party litigation financing where investors buy pieces of lawsuits from plaintiffs. Many scholars believe that this new financing helps to balance the risk tolerance of plaintiffs and defendants and thereby facilitates the resolution of litigation in a way that more closely tracks the goals of the substantive law. In this Article, I ask whether these risk-balancing virtues of claim investing carry over into class action cases. This is a question that has not yet been addressed by scholars because many think it is not possible for financiers to buy pieces of class action lawsuits in the United States. But I show that such investments are neither impractical nor unethical; indeed, it appears that they are already here. It is therefore worth considering whether the investments confer the same social benefits they do in other cases. I argue that although class members do not need a risk transfer device in class action cases because they are almost always risk-neutral in light of their small losses, their lawyers do need such a device. Although this does not necessarily mean that claim investing is socially desirable overall in class actions, the social costs that have thus far been identified with claim investing seem modest compared to the benefits.

Introduction

In a brilliant article in 2010 entitled Litigation Finance: A Market Solution to a Procedural Problem,[1] Jonathan Molot made a compelling case for third-party financing of lawsuits: in a world where plaintiffs and defendants sometimes have different risk constraints, selling some or all of legal claims and defenses to unconstrained third parties offers us a more promising way to ensure that lawsuits are resolved at the right “price” than procedural reforms to our legal system. Professor Molot’s article has been incredibly influential, and has contributed significantly to the tremendous rise over the last few years of a new form of litigation financing in the United States where plaintiffs sell a portion of their claims to third parties in exchange for upfront cash compensation.

In this Article, I ask whether the risk-balancing virtues of this new claim investing carry over into class action cases. This is a question that has not been much addressed by scholars because many commentators think it is not possible for financiers to buy a piece of a class action lawsuit.[2] Some commentators think it is impractical, others unethical. But in this Article I try to show that it is neither impractical nor unethical for financiers to buy into class action cases. Indeed, it appears that modified forms of this new financing are already there. And I doubt these modifications are even necessary: I think there are practical and ethical ways for financiers to buy portions of class claims just as they do other claims.

For this reason, I think it is worth asking whether the social benefits of claim investing identified by Professor Molot carry over to class action cases. If not, perhaps we should foreclose any expansion of the new financing into those cases. Indeed, given that plaintiffs are not often risk-averse in class actions because they have so little at stake, it is hard to see what risk disparity exists for financing to mitigate. However, this view overlooks the role that lawyers play in class litigation; in many ways, the lawyers are the real parties in interest. Class action lawyers are the parties who decide to bring litigation and who decide when to settle it. These decisions are driven by the fee awards (usually a percentage of the recovery) they stand to gain from their cases. If they decide to settle too early because they are more risk averse than defendants, then there may indeed be risk-balancing gains when they can sell some or all of their stakes to third parties.

This does not necessarily mean that we should continue to permit the claim investing in class action cases. Some commentators have identified social costs to the new financing as well as social benefits. Thus far, however, these costs seem modest and unlikely to outweigh the benefits.

In Part I, I set forth a brief overview of the old and new forms of third-party financing in the United States. I then recount the risk-balancing virtues most scholars believe the new, claim-investing financing brings to American litigation. In Part II, I discuss whether these virtues carry over to class action litigation as well as show how the new financing can be — and, in some respects, already is — used in class action litigation. In light of the riskbalancing benefits financing can bring to class action lawyers, the benefits of financing may very well outweigh the costs even in class action litigation.

I The Old and New Third-Party Litigation Financing in the United States

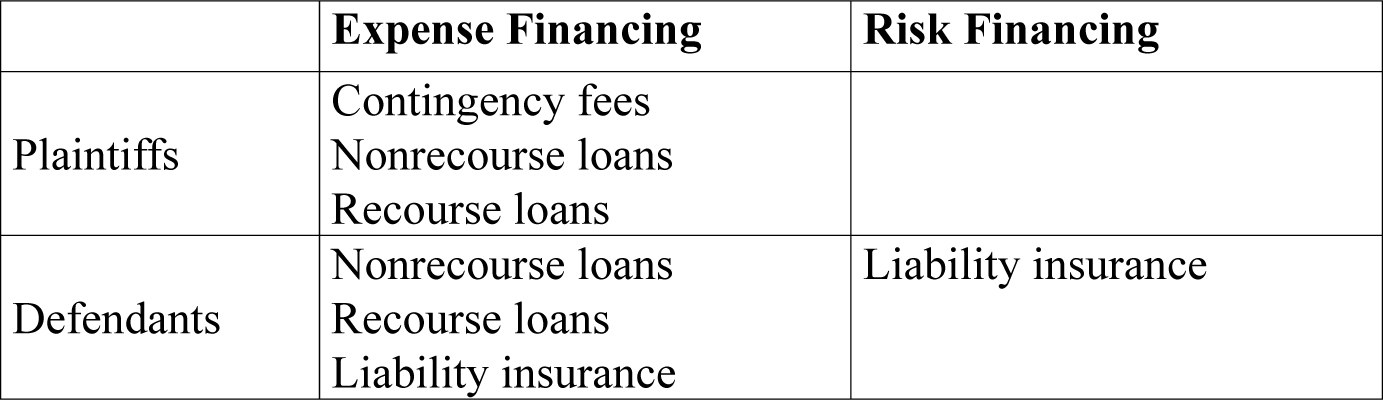

Lawsuits in the United States can be both expensive and risky, and litigants have long mitigated these exigencies by turning to third parties to pay their litigation expenses and to shift their litigation risk. Traditionally, these third parties have been a litigant’s lawyer (i.e., contingency fees), a liability insurer, or a recourse or nonrecourse lender. In Figure 1, I organize the traditional sources of financing expenses and risk.

A Typology of Old Litigation Financing

As Figure 1 shows, both sides to a lawsuit have long had access to various forms of expense financing; I will not dwell on them much in this Article. But this has not been so with regard to risk financing. Here, it has been thought that plaintiffs have not had access to mechanisms to shift the risk that they might lose a lawsuit.[3] Defendants, by contrast, have liability insurance. Not only do liability insurers help defendants by paying their litigation expenses, but they assume much of the risk of adverse judgments as well.

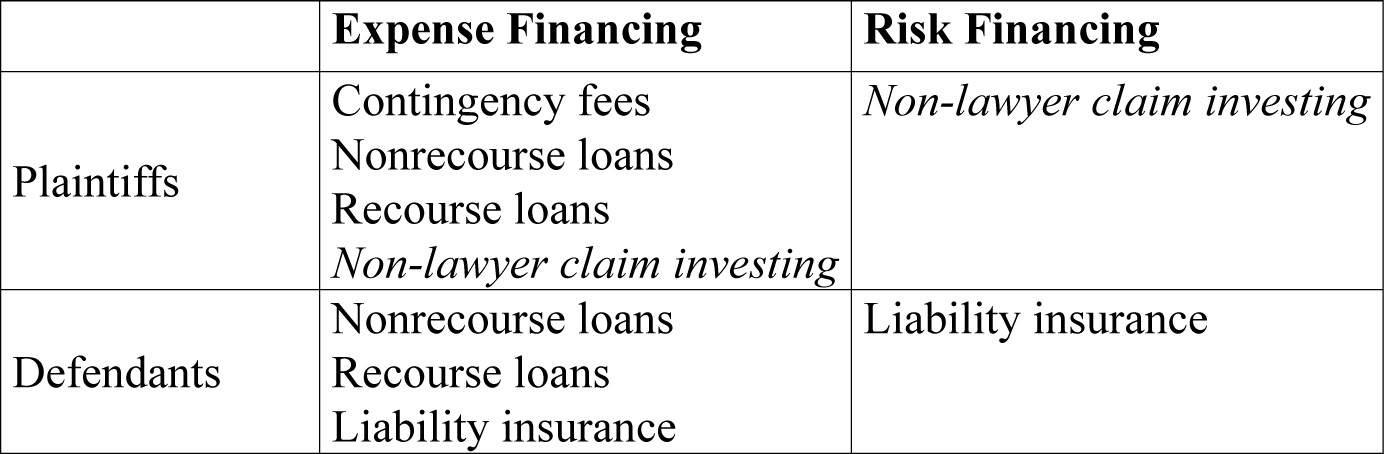

However, this disparity has now been overcome. With the recent relaxation of laws against champerty and maintenance,[4] plaintiffs can now sell portions of their recoveries to non-lawyer investors.[5] These investors — investment banks and hedge funds like Burford Capital[6] and Bentham IMF[7] — pay plaintiffs cash up front in exchange for a percentage of their eventual recoveries (if any).[8] The plaintiffs often use the money to pay their lawyers by the hour and to pay for other litigation expenses — so claim investing can be a new form of expense financing — but, for the first time, they can also use the money to transfer the risk of an adverse judgment: they can book a certain gain now and make the investor shoulder the risk instead. For this reason, in the eyes of many commentators, the new financing is the functional equivalent of liability insurance on the plaintiff-side of litigation.[9] I depict this in Figure 2 by adding claim investing to the plaintiffs’ columns in Figure 1.[10]

A Typology of Old and New Litigation Financing

Why does it make a difference whether plaintiffs have a risk-financing device as defendants do? To see why, consider the all-too-common lawsuit where the plaintiff is more risk-averse than the defendant. Without risk financing available to the plaintiff, the plaintiff will be inclined to settle the case for less than its expected value because the plaintiff is willing to trade more money to avoid the risk of an adverse jury verdict than the defendant is.[11] As Professor Molot argued, this means that such a lawsuit is therefore not resolved according to its “merits,” but, rather, according to the arbitrariness of which side is more risk-averse.[12] This is socially undesirable because, when lawsuits are not resolved according to their merits, plaintiffs are not compensated and defendants are not deterred as prescribed by the substantive law.[13]

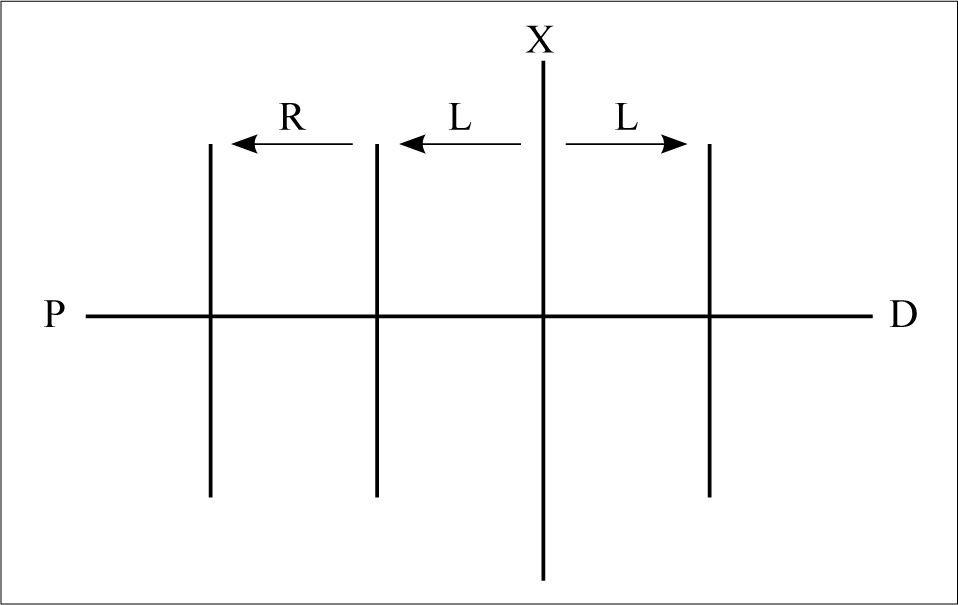

I depict this in Figure 3, which is a common schematic that law-and-economics scholars use to demonstrate at what price litigation settles. On the left side of the schematic is the plaintiff’s economic position (“P”), and on the right side is the defendant’s economic position (“D”). In the middle, the line “X” depicts how much money the average jury would award the plaintiff in this lawsuit — what Professor Molot called the “merits.” The lines “L” depict what each party expects to pay in litigation expenses to get to the jury verdict. If we ignore risk preferences (i.e., ignore line “R” in Figure 3), the settlement range — the range where each party is made better off by settlement rather than by expending litigation expenses to go to the jury — is the area from X-L to X+L; the plaintiff is willing to settle for any amount above what it expects to win before the jury minus how much it would cost to get there, and the defendant is willing to settle for any amount below what it expects to lose at trial plus how much it would cost to get through it. In an ideal world, the lawsuit would settle at the “X” line because we assume that is the level of compensation and deterrence the substantive law has determined we need.[14] Because the settlement range is symmetrical around “X” in this example, if the parties are equally strong negotiators, that’s exactly where we might expect the settlement to fall. If it does, then the lawsuit resolves at the “right” price without wasting resources on trial. That is what economists call Pareto efficient.

A Model of Settlement

But many things can disrupt this happy story. The parties may not agree on what the expected value of the case is.[15] The parties may not have equal litigation expenses.[16] Either of these things can skew settlement away from “X.” Or, as relevant here, the parties may have different risk preferences. I have depicted this in Figure 3 with the line “R” — a line that shows how much the plaintiff is willing to pay to avoid running the risk of losing the trial. If the defendant is risk-neutral and therefore has no “R” line, then, as the Figure shows, the settlement range becomes X-L-R to X+L. Because this range is asymmetrical around “X,” even when the parties are equally strong negotiators, we would expect the settlement to fall somewhere short of “X.” This means we would not expect the plaintiff to receive all the compensation prescribed by the substantive law nor expect the defendant to face the right level of deterrence.

The virtue of the new, claim-investing financing is that it mitigates the problem of risk imbalance. Now, the risk-averse plaintiff can simply sell some or all of its claim to a third-party financier who is risk-neutral. It is true that the plaintiff does not receive quite the compensation the substantive law prescribed because it must pay some sort of premium to the third-party financier, but the plaintiff gets much closer than if it had to do it alone. And, although the defendant may or may not face the deterrence that the substantive law prescribed, depending on whether the plaintiff transfers enough risk to reduce “R” in Figure 3 to zero, again, things are better in that regard than they would be without financing.

II What About Class Actions

Do the risk-balancing virtues of claim investing carry over to class action litigation? Commentators have not yet addressed this question because it is thought that it is not possible for financiers to buy a piece of a class action lawsuit. Indeed, the major claim-investing financiers say they have eschewed any interest in funding class action cases in the United States. Part of this is no doubt to stave off political controversy — class actions are as controversial in their own right as the new financing is; combining the two would bring a world of trouble. But part of this is also because it is thought difficult to put together the financing deals in class action cases. In these deals, investors buy a portion of a plaintiff’s recovery; the investor enters into a contract directly with the plaintiff. Thus, in a class action case, the investor would have to find each and every class member and enter into an agreement with them in order to receive a share of the class’s recovery. This is obviously difficult to do and many people think it is completely impractical.

On the other hand, it is how things are done in other countries. In Australia, for example, investors who want to fund securities fraud classes find shareholders and sign them up one by one. What happens if they don’t get everyone signed up? The class action proceeds only with the shareholders who did.[17] There is nothing to stop financiers in the United States from doing this, too, but it comes at a high price: it converts our opt-out class action into an opt-in one because only the class members who opt in to the financing agreement stay in the class.[18] Whatever attraction this has had to investors in Australia, it has not proved attractive to financiers in America.

What about the class action lawyer? Couldn’t the financier buy a share of the lawyer’s portion of the class’s recovery, thereby indirectly buying a share of the class’s recovery? For example, class action lawyers are usually awarded 25% of any class recovery they win in the United States;[19] why couldn’t the financier buy half of that and thereby take what will probably be a 12.5% stake in the case? The problem here is not a practical one, but an ethical one: lawyers cannot split their fees with non-lawyers.[20]

But I have seen lawyers do it nonetheless, by converting fee-splitting contracts into graduated, nonrecourse loans or into firm-wide, revenue-splitting contracts. Consider first the graduated, nonrecourse loan. In a common nonrecourse loan contract, the borrower pays nothing if the lawsuit fails, but pays back a multiple of the loan if the lawsuit is successful. It is routine for such contracts to require the borrower to pay back higher multiples the longer it takes to resolve the lawsuit. But what if the contract graduated the multipliers based on the amount the lawsuit recovered rather than the duration of the lawsuit (e.g., 1.5x if the plaintiff recovered one million dollars or less; 2x if the plaintiff recovered between one and two million dollars; 3x if the plaintiff recovered above two million dollars)? It would approximate a contract whereby the lender received a percentage of the recovery; the greater the number of partitions, the closer the two contracts would come to one another.[21] But if that is too complicated for you, there is an even easier way to evade the ethical rule: lenders are often allowed to recover a percentage of a lawyer’s fees from his portfolio of cases (i.e., firm-wide gross revenues), even though they are not allowed to do so from a single case.[22] It is therefore not surprising that one of the most popular courts for class action filings has now entered a standing order requiring “disclosure [of] any person or entity that is funding the prosecution of any claim or counterclaim” in a class action.[23]

Thus, modified versions of the new financing are already afoot in class action cases. But could the modifications be dropped and investors find some way to buy a share of the class’s recovery directly, without losing the power of the opt-out class action? I think they can. In my view, we already have a mechanism at our disposal to force class members to pay financiers even when they do not affirmatively consent to doing so; it is the same mechanism we use to force class members to pay class action lawyers when they do not consent to doing so: unjust enrichment doctrine.[24]

The lawyers who file and prosecute class actions create benefits for class members equal to whatever class members recover in the class actions; under this doctrine, it is unjust for the class to take the benefits and not pay the lawyers for creating it.[25] This is also sometimes called the “common benefit” doctrine.[26]There is nothing in this doctrine that limits its application only to efforts by lawyers who create benefits for others; indeed, its earliest application was to efforts by one of several trust beneficiaries to improve trust assets; the other trust beneficiaries were forced to pay their fair share for these efforts.[27] If third-party financiers likewise provide the class with help, there is no reason why the class should reap the benefit of the help without paying for it. When a class action settles or ends in a verdict, a court could give a portion of any judgment to the financiers, just as it does now to the lawyers. Apparently, Canadian courts have already adopted this approach to accommodate financing in class actions,[28] and Australian courts are considering it as well.[29] I see no reason why it cannot be done in the United States, too.

How might all of this work in practice in the United States? It might work in one of two ways. First, a financier could appear before the court at the outset of a case — presumably with the support of the class representatives or class counsel — and ask the court to permit it to pay the litigation expenses in the case, to pay the class upfront compensation, or both, in exchange for some percentage of the recovery should there be one. Although it would be unusual to make such an arrangement before the case is over,[30] courts have done it for attorneys’ fees[31] and there is no reason they could not for a financier. Indeed, not only has it been done for fees, but scholars think the best way to set fees is at the outset of the case;[32] the same is true for third-party financing.[33] (Even better still would be to auction off financing[34] — or to auction off the entirety of the class’s claims[35] — at the outset of the case.)

Second, the court could pay the financier at the end of a case much as it does now the class action lawyer. In this scenario, the financier could strike a deal with the class representative or the lawyer at the outset of the case to pay the litigation expenses in the case (i.e., class counsel’s fees by the hour and costs for experts and the like) in exchange for support from the class representative or the lawyer at the end of the case for a request to the court to pay to the financier the common-benefit award that would otherwise have gone to the lawyer. It will obviously be riskier for the financier to wait until the end of the case to learn how much of the class’s recovery the court is willing to pay it, but class action lawyers routinely endure the same risk and they still bring class action cases. Although the back-end scenario may make financing more expensive, it should not make it impossible.

Thus, I think the new financing is already in our class action cases in some form and may very well expand in the future. If so, then it is worth asking whether the same risk-balancing virtues of the new financing discussed in the previous Part can be found as well in class action cases. If not, perhaps we should foreclose any expansion of the new financing into those cases.

On the one hand, it is hard to see any benefit to permitting the plaintiffs in class action lawsuits to access risk financing. As Professor Molot himself has noted, the vast majority of class actions are comprised wholly or at least mostly of persons with only a small stake in the lawsuit;[36] that is, class members are typically not risk-averse at all over the small losses that class actions usually seek to redress.[37] This is, of course, one of the primary reasons why we have the class action to begin with: to aggregate into a viable litigation vehicle claims that are too small to bring on their own.[38] If the principal benefit of the new financing is to permit the plaintiff side to draw even with the risk profile of the defendant side, then there is no such benefit to realize through financing to class members.

However, as noted above, the financing can also take place (and is already taking place in some form) vis-á-vis the class action lawyer. And, indeed, even more so than in individual cases, the lawyers are the real parties in interest in class action cases; they are the ones making the decisions whether to settle and for how much.[39] If we are concerned about risk aversion skewing settlements, then, in class action cases, we should be focused on the lawyer and not the class member anyway. If class action lawyers under-settle cases due to risk imbalances, then class members get too little compensation and defendants face too little deterrence in exactly the same way that we worry plaintiffs and defendants do when there are risk imbalances in individual cases. And unlike class members, class action lawyers are risk-averse; they have a lot of time and money on the line in class action cases and even the largest firms with vast portfolios of cases are not risk-neutral in their largest cases. Thus, it seems to me that the new third-party financing can do work even in class action cases to the extent that the financiers buy some or all of the lawyers’ stakes.

It is true that claim investing might sometimes exacerbate rather than ameliorate risk imbalances in class action litigation. This is the case because the class action device has the effect of increasing risk to the defendant. If a class action case goes to trial, a single jury might resolve thousands or even millions of claims. This makes the defendant’s worst-case scenario — losing every single case — a realistic possibility (perhaps the same probability of losing any single case).[40] For this reason, class action lawyers sometimes may be less risk-averse than defendants once a class is certified.[41] If we add claim investing on the plaintiff side, too, we arguably make the risk disparity worse, not better.

Of course, defendants already have access to liability insurance to shift this risk. But if the worst-case scenario is big enough — i.e., beyond the abilities of corporations to buy liability insurance — even rich corporations might be willing to pay a risk premium to avoid trial.[42] In my view, however, there are better ways to deal with the trial risk that class actions impose on defendants than to neuter third-party financing: stop letting one jury decide the entire class action case. I have long proposed sampling to resolve class action trials for this very reason.[43] To borrow Professor Molot’s formulation: sometimes the best solution to a procedural problem may still be a procedural one.[44]

This does not mean that claim investing is necessarily socially desirable in class action cases. Some commentators have identified social costs associated with claim investing. Any serious inquiry into the desirability of claim investing in class actions must assess these potential costs, and, in the paragraphs below, I attempt to do so briefly.

Perhaps the most popular complaint about claim investing is that it leads to more litigation.[45] This might be bad insofar as litigation increases the costs of undertaking activities in our society. But if financing leads to more litigation, it would seem to do so only because, as I explained, the financing disadvantages of plaintiffs have led them to file too few cases now. Thus, this is really not a cost of claim investing, but a benefit. The same is true of the worry that claim investing will cause litigation to last longer, thereby consuming greater resources of the parties and the court system.[46] Although other scholars dispute this notion,[47] even if it is true, again, it would seem to do so only because a world without claim investing led parties to settle cases too quickly for lack of resources or lack of risk tolerance.

Some scholars have been concerned that claim investing could increase agency costs because now there are two agents who might have interests that diverge from the litigant’s: the lawyer and the investor.[48] Other scholars dispute this notion, too,[49] but, even if it is true, it seems to me the problem is solvable by contract: why wouldn’t a financier write the financing contract to align the lawyer’s interests as closely as possible with its own? Of course, this will not eliminate the preexisting lawyer-client agency costs in class action litigation, but I see no reason why claim investing should exacerbate them.

Finally, some scholars worry that the new financing will skew the types of cases that are litigated.[50] For example, some scholars note that it is difficult for financiers to make money on suits seeking only injunctive relief; thus, financing will shun such cases.[51] Others worry that financiers will be drawn most particularly to low-probability cases (because here the risk-tolerance differentials between financiers and litigants are the greatest).[52] As an empirical matter, these scholars may very well be correct (though others scholars think investors will finance the most meritorious rather than the least meritorious cases[53]), but I have a hard time understanding these concerns as “costs.” That is, it seems to me that financing is only additive: it does not depress the litigation of injunctive or high-probability cases; it only adds the litigation of other cases. The only objection that can be made here, it seems to me, is that it is not the highest use of court resources to litigate the sorts of cases that will be financed, and this will deprive higher-priority cases of those resources. This strikes me as a sound objection only for low-probability cases, and, even if financing leads to more of these cases, it strikes me as a vanishingly small cost compared to the financing benefits described above.

For all these reasons, even in class actions the case against claim investing strikes me as weaker than the case for it.

Conclusion

I think the day when financiers buy up pieces of class action cases may already be upon us in the United States. Moreover, whatever practical or ethical hurdles do still stand in the way may soon be toppled. It is therefore worth asking whether claim investing offers the same risk-balancing benefits in class action cases that it does in other cases. I think it does, but not because plaintiffs need risk transfer devices; rather, it is because their lawyers do. This does not necessarily mean that this new financing is socially desirable overall in class actions, but the social costs that have thus far been identified with the new financing seem modest compared to the social benefits.

© 2018 by Theoretical Inquiries in Law

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Introduction

- Keynote Address

- The American Class Action: From Birth to Maturity

- Publicly Funded Objectors

- Tiered Certification

- Can and Should the New Third-Party Litigation Financing Come to Class Actions?

- The Global Class Action and Its Alternatives

- Class Actions in the United States and Israel: A Comparative Approach

- Regulation Through Litigation — Collective Redress in Need of a New Balance Between Individual Rights and Regulatory Objectives in Europe

- Towards Collaborative Governance of European Remedial and Procedural Law?

- Class Action Value

- When Pragmatism Leads to Unintended Consequences: A Critique of Australia’s Unique Closed Class Regime

- Rethinking the Relationship Between Public Regulation and Private Litigation: Evidence from Securities Class Action in China

- The Regime Politics Origins of Class Action Regulation

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Introduction

- Keynote Address

- The American Class Action: From Birth to Maturity

- Publicly Funded Objectors

- Tiered Certification

- Can and Should the New Third-Party Litigation Financing Come to Class Actions?

- The Global Class Action and Its Alternatives

- Class Actions in the United States and Israel: A Comparative Approach

- Regulation Through Litigation — Collective Redress in Need of a New Balance Between Individual Rights and Regulatory Objectives in Europe

- Towards Collaborative Governance of European Remedial and Procedural Law?

- Class Action Value

- When Pragmatism Leads to Unintended Consequences: A Critique of Australia’s Unique Closed Class Regime

- Rethinking the Relationship Between Public Regulation and Private Litigation: Evidence from Securities Class Action in China

- The Regime Politics Origins of Class Action Regulation