Abstract

Publication of a new gold epistomion unearthed during rescue excavations in the property of IRIS Hotel Inc. in the Sfakaki region near Rethymno. The new epistomion from Grave 7 belongs to category E, the so-called chaire-texts, and is identical to that incised on E4, bringing the total number of epistomia from Crete to sixteen (see Appendix).

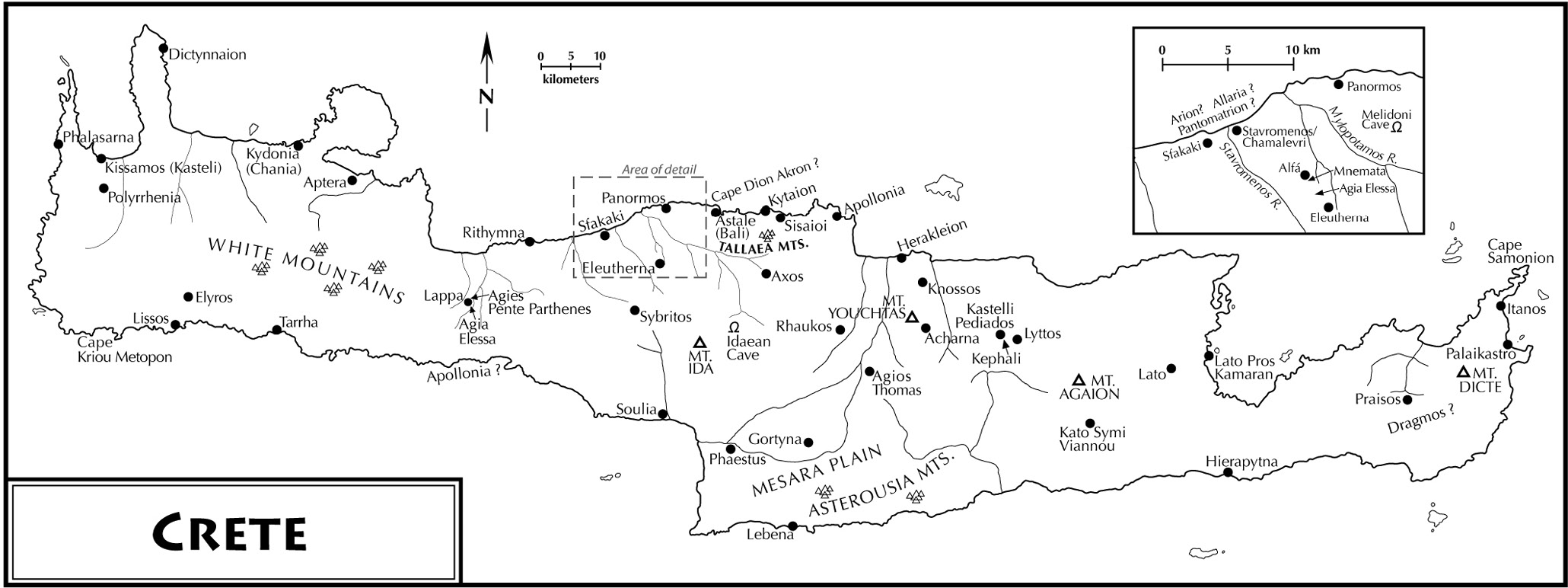

During rescue excavations by the Ephorate of Antiquities in Rethymno in the property of the IRIS Hotel Inc. in the region of Sfakaki, thirty-eight graves came to light. In the same area and to the west of this property, earlier rescue excavations in the properties of Markos Polioudakis and Michalis Pyrgaroussis revealed twenty-seven and thirty graves respectively, apparently all part of a cemetery by the seashore to the N of the modern highway. The region Sfakaki, ca 8 km east of Rethymno and 10 km north from ancient Eleutherna, is in close proximity to the archaeologically better-known sites of Stavromenos and Chamalevri, where thanks to the excavations by the Rethymno Ephorate of Antiquities extensive settlement(s) and burial sites have come to light.[1] The area of Sfakaki-Stavromenos-Chamalevri probably constitutes the territory of an ancient city-state, whose name is uncertain, but its existence is confirmed by a 2nd century BCE inscription that refers to the institution of a city’s kosmoi who were in charge of a sanctuary’s renovation.[2] Unfortunately, evidence from Sfakaki is still too inconclusive to support its identification with one of Eleutherna’s seaports in the north shore or some other settlement by the sea (fig. 1).

Context and Chronology. The thirty-eight graves in the property of IRIS Hotel Inc. are cut at two different levels and belong to four different types: sixteen are tile-graves, twenty-one cist-graves (fourteen simple and seven built) and one is a pit-grave (fig. 2). All graves were oriented on the E-W axis and eight extended to the eastern adjacent property where more were buried. Although most skeletal remains were found decomposed due to sea-corrosion, the deceased were in a supine position with head to the E with only one exception of a skull to the W in grave 20. Most of the grave-goods are 233 closed and small clay vessels of very few types (unguentaria, small amphorai and phialai, ladles, wine-jars, loom-weights), but also glass vessels, objects and beads, a pin, metal objects and jewelry (mainly bronze but a few of gold, iron, and lead), a number of silver and bronze coins, bone and stone objects, an obsidian flake, and an incised gold epistomion.

Based on the type of the graves and their grave-goods, the chronology for the thirty-eight graves covers the Hellenistic period to the middle of the 1st century CE, with the earliest burial belonging to the early 3rd BCE.

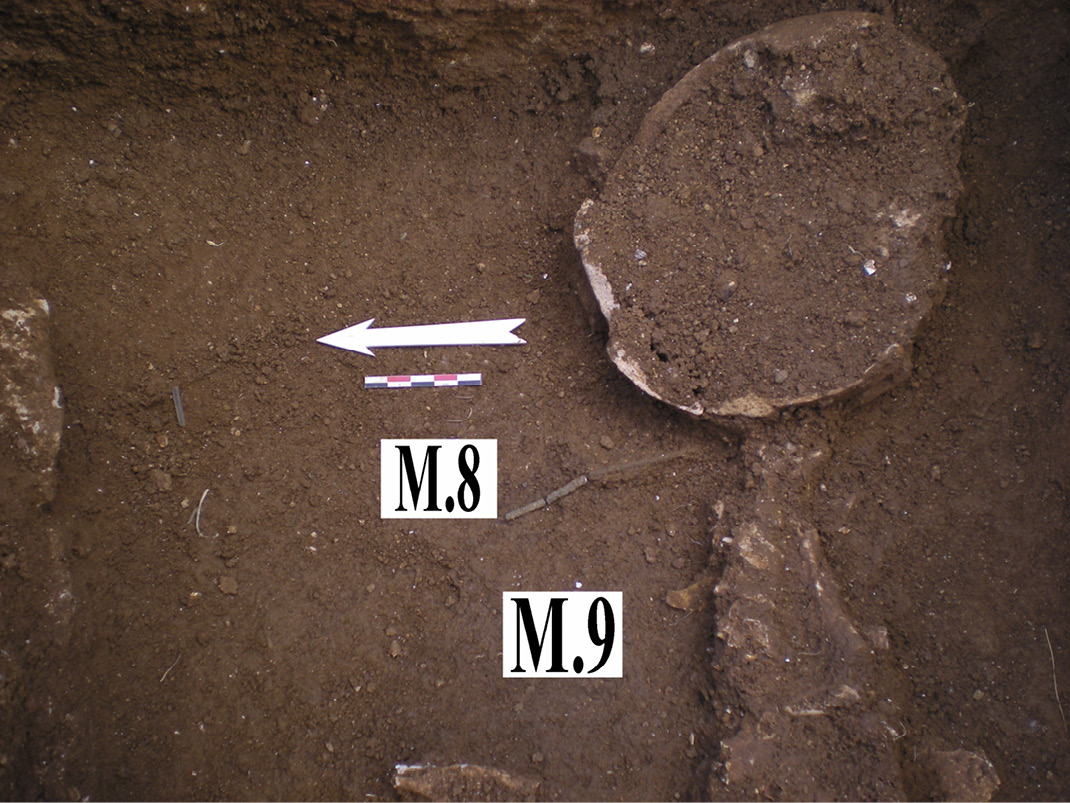

Grave 7 (figs. 3 and 4). Cist-grave 7 was found intact covered with limestone slabs in second use. The grave is oriented W-E measuring 2,00 m x 0,88 m. Its floor consists of the local yellowish earth and its dimensions after the excavation are 1,50 m. x 0,51 m. (east) and 0,45 m. (west). The deceased was placed in a supine position with head to the E and hands parallel to the body. The epistomion was found under the lower jaw and spinal vertebrae and must have been placed on the lips of the deceased during the burial rites (fig. 5). The deceased’s grave-goods include clay, glass and metal objects, among them: four clay bulbous unguentaria (fig. 6), similar to those found in Grave 1 of Polioudakis’ plot at Sfakaki and dated to the last quarter of the 1st century BCE and the first half of the 1st century CE;[3] a lead pyxis with its lid (fig. 7),[4] similar to the one from Grave 3 in Polioudakis’ plot; a pair of gold earrings with tiny fayence beads (fig. 8); a gold ring with a standing female in the type of Aphrodite Anadyomene; and the unfolded gold epistomion (figs. 9 and 10). The types of grave goods indicate that the deceased was probably a female.

The grave-goods are quite similar to the ones from Grave 1 of Polioudakis’ property wherefrom epistomion E4 and Grave I of Pyrgaroussis’ property wherefrom epistomion B12 (Grave I in Pyrgaroussis’ plot is dated to the 2nd or early 1st century BCE on the basis of its unguentaria).[5]

Inscription (Rethymno, Archaeological Museum, inv. no. Μ 5596, fig. 10). The incised gold epistomion in the shape of the mouth is preserved in excellent condition with only minor wrinkles and tears. As can be surmised, there are no holes through which would pass a string for fastening. It is almost identical to E4, except that instead of being rounded the edges are cut as in the unincised G2,[6] both from graves in Polioudakis’ property.

Bibliography: Tsatsaki/Flevari 2015, 348–350, figs.7–10.

Dimensions: H. 0.09 m, W. 0.052 m, Th. less than 0.001 m, LH. 0.001–0.002 m.

25 BCE–50 CE

Πλούτωνι

Φερσεφόνῃ.

(Greetings) to Plouton and Persephone.

In line 2 the spelling of Persephone’s name with iota omitted in the dative is identical to that in E4. The letters are carefully engraved, although as in E4 they appear pressed, and their shapes are similar to that of other Cretan epistomia, especially E4: rectangular epsilon, small ‘hanging’ omicron, four-bar sigma, and closed omega.[7]

Commentary. The new epistomion is the sixth from the Sfakaki cemetery (two of them E4 and B12 incised and three unincised G2–4; see Appendix). According to the proposed classification, the new epistomion is E6, namely belongs to the category of texts in which the chaire-formula is employed or implied in addressing the Underworld deities, either Plouton or Persephone by name or epithet, or both.[8]

This new text brings the total number of Cretan epistomia to sixteen (16) (see Appendix): ten deceased buried with an epistomion (B3–8, B13–15, E1) in the site Mnemata near the village Alphá – rougly at the midpoint of the approximately 10 km distance from Eleutherna to the north shore – were active from the 3rd to the 1st centuries BCE; and six buried with an epistomion in the cemetery at Sfakaki/Stavromenos from the late 2nd century BCE to the middle of the 1st century CE (E4, B12, E6 and the unincised G2–4).[9] What these sixteen burials highlight in a remarkable way is that within a distance of ca 10 km north of ancient Eleutherna and in a period of three centuries the initiates in an otherwise homogeneous bachchic-orphic cult did not all conform to identical ways:[10] ten incised ‘extracts’ of the so-called ‘Mnemosyne’– or Underworld-topography-texts (B3–8 and B13–15 from Mnemata, and B12 from Sfakaki), among which three epistomia (B6, B12, and B15) betray more or less important differences (see Appendix): whether these three ‘deviations’ from the norm of texts in category B are due to the engraver’s mistake or to the choice of text by the three deceased cannot be answered definitively; three decided not to incise anything (G2–4 from Sfakaki); and three chose the chaire-formula in addressing the Underworld deities (E1 most likely from Mnemata, and E4 and E6 from Sfakaki). The new sixth epistomion (E6) of probably a female deceased from the Sfakaki cemetery – identical to epistomion E4 of a male from the same cemetery and dated approximately to the same period (could both deceased have been from the same family?) – is a welcome addition to the ever growing orphic-dionysiac corpus of epistomia in Crete.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Loukia Flevari for her collaboration and to the staff in the Archaeological Museum at Rethymno for facilitating the study; for their constructive suggestions and improvements we are indebted to the editors Franco Montanari and Antonios Rengakos and the staff of Trends in Classics, and the anonymous readers.

Bibliography

Bernabé, A./Jiménez San Cristóbal, A. (2008), Instructions for the Netherworld: The Orphic Gold Tablets, with iconographical appendix by R. Olmos and illustrations by S. Olmos, trans. M. Chase (Religions in the Graeco-Roman World 162), Leiden.10.1163/ej.9789004163713.i-379Search in Google Scholar

Bremmer, J.N. (2016), “The Construction of an Individual Eschatology: The Case of the Orphic Gold Leaves”, in: Burial Rituals, Ideas of Afterlife, and the Individual in the Hellenistic World and the Roman Empire, ed. K. Waldner/R. Gordon/W. Spickermann (Potsdamer Altertumswissenschaftliche Beiträge 57), Stuttgart, 31–51.Search in Google Scholar

Chrysanthou, A. (2020), Defining Orphism: the Beliefs, the Teletae and the Writings (Trends in Classics – Supplementary Volumes 94), Berlin-Boston.10.1515/9783110678451Search in Google Scholar

Edmonds III, R.G. (ed.) (2011), The ‘Orphic’ Gold Tablets and Greek Religion: Further Along the Path, Cambridge.10.1017/CBO9780511730214Search in Google Scholar

Edmonds III, R.G. (ed.) (2013), Redefining Ancient Orphism. A Study in Greek Religion, Cambridge.10.1017/CBO9781139814669.013Search in Google Scholar

Gavrilaki, I. (1995), “Σφακάκι Παγκαλοχωρίου. Οικόπεδο Πολιουδάκη” (“Sphakaki Pagkalochōriou. Oikopedo Polioudakē”), in: ΑΔ 44, Χρονικά Β2, 457–460, pl. 253–254.10.1007/BF02547151Search in Google Scholar

Gavrilaki, I./Tzifopoulos, Y. (1998), “An ‘Orphic-Dionysiac’ Gold Epistomion from Sfakaki near Rethymno”, in: BCH 122, 343–355.10.3406/bch.1998.7175Search in Google Scholar

Graf, F./Johnston, S. I. (2013), Ritual Texts for the Afterlife: Orpheus and the Bacchic Gold Tablets, London-New York.10.4324/9780203564240Search in Google Scholar

Herrero de Jáuregui, M. (2015), “The Construction of Inner Religious Space in Wandering Religion of Classical Greece”, in: Numen 62, 667–697.10.1163/15685276-12341395Search in Google Scholar

Janko, R. (2016), “Going Beyond Multitexts: the Archetype of the Orphic Gold Leaves”, in: CQ 66, 100–127.10.1017/S0009838816000380Search in Google Scholar

Martínez Fernández, Á./Tsatsaki, N./Kapranos, Ep. (2008), “Μια ελληνιστική δημόσια επιγραφή από το Χαμαλεύρι Ρεθύμνου”, in: Κρητική Εστία 12, 2007–2008, 33–51 (“Mia ellēnistikē dēmosia epigraphē apo to Chamaleuri Rhethumnou”, in: Krētikē Estia 12, 2007–2008, 33–51).Search in Google Scholar

Meisner, D.A. (2018), Orphic Tradition and the Birth of the Gods, Oxford.10.1093/oso/9780190663520.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Tegou, E./Tzifopoulos, Y.Z. (2021), “New Epistomia from Eleutherna”, in: TiC 13, 418–436.10.1515/tc-2021-0014Search in Google Scholar

Tsatsaki, N. (2020), “Numismatic Evidence from Hellenistic Burials at Sfakaki, Rethymnon”, in R. Cantilena/F. Carbone (eds.), Monetary and Social Aspects of Hellenistic Crete, ASAtene, Supplemento 8, 377–383.Search in Google Scholar

Tsatsaki, N./Flevari, L. (2015), “Σωστική ανασκαφική έρευνα στο Σφακάκι Παγκαλοχωρίου, Δήμου Ρεθύμνου”, in: Αρχαιολογικό έργο Κρήτης 3: Πρακτικά της 3ης συνάντησης, Ρέθυμνο, 5–8 Δεκεμβρίου 2013, ed. P. Karanastasi/A. Tzigounaki/Ch. Tsigonaki, Rethymno, 343–352 (“Sōstikē anaskaphē ereuna sto Sphakaki Pagkalochōriou, Dēmou Rhethumnou”, in: Archaiologiko ergo Krētēs 3: Praktika tēs 3ēs sunantēsēs, Rhethumno, 5–8 Dekembriou 3013, ed. P. Karanastasi/A. Tzigounaki/Ch. Tsigonaki, Rethymno, 343–352).Search in Google Scholar

Tzifopoulos, Y.Z. (2010), ‘Paradise Earned’: the Bacchic-Orphic Gold Lamellae of Crete, (Center for Hellenic Studies, Hellenic Series 23), Washington, DC-Cambridge, MA. https://chs.harvard.edu/CHS/article/display/5109.yannis-tzifopoulos-paradise-earned-the-bacchic-orphic-gold-lamellae-of-crete.Search in Google Scholar

Tzifopoulos, Y.Z. (2010–2013), “Χρυσά ενεπίγραφα επιστόμια, νέα και παλαιά” (“Chrusa enepigrapha epistomia, nea kai palaia”), in: Horos 22–25, 351–356.Search in Google Scholar

Appendix: The Sixteen Cretan Epistomia

|

Provenance |

Date |

Gender |

Shape |

Position in grave |

Coin |

Burial and Grave-goods |

||

|

B3 |

Eleutherna, Crete |

III–I c. |

not known |

rectangular, folded |

not known |

not known |

not known |

δίψαι αὖος ἐγὼ καὶ ἀπόλλυμαι· ἀλλὰ πιε̑<μ> μοι | κράνας αἰειρόω ἐπὶ δεξιά· τῆ, κυφάριζος. | τίς δ’ ἐζί; πῶ δ’ ἐζί; Γᾶς υἱός ἠμι καὶ Ὠρανῶ | ἀστερόεντος. |

|

B4 |

Eleutherna, Crete |

III–I c. |

not known |

rectangular, folded |

not known |

not known |

not known |

δίψαι αὖος ἐγὼ καὶ ἀπόλλυμα{μα}ι· ἀλλὰ πιε̑<μ> μοι | κράνας αἰειρόω ἐπὶ δεξιά· τῆ, κυφάριζος. | τίς δ’ ἐζί; πῶ δ’ ἐζί; Γᾶς υἱός ἠμι καὶ Ὠρανῶ | ἀστερό<ε>ντος. |

|

B5 |

Eleutherna, Crete |

III–I c. |

not known |

rectangular, folded |

not known |

not known |

not known |

δίψαι αὖος {ααυ̣οσ} ἐγὼ καὶ ἀπόλλυμαι· ἀλλὰ πιε̑μ μου̣ | κ̣ράνας <α>ἰενάω ἐπὶ δε[ξ]ιά· τῆ, κυφάρισζος. | τίς δ’ ἐζί; πῶ δ’ ἐζί; Γᾶς υἱός ἠμ<ι> καὶ Ὠρανῶ | ἀστερόεντ[ο]ς. |

|

B6 |

Eleutherna, Crete |

III–I c. |

not known |

epistomion, folded? |

not known |

not known |

not known |

δίψᾳ δ’ ἠμ’ αὖος καὶ ἀπόλ<λ>ομαι· ἀλ<λ>ὰ | πιε̑ν μοι κράνας ΑIΓIΔΔΩ ἐπὶ | δεξιά· τε̑, κυπ<ά>ριζος. τίς δ’ ἐζί; π|ῶ δ’ ἐζί; Γᾶς ἠμι Γ̣ΥΑ̣ΤΗΡ καὶ | Ὠρανῶ ἀστερόεντος. |

|

B7 |

Eleutherna, Crete |

III–I c. |

not known |

rectangular, rolled in cylinder? |

not known |

not known |

not known |

δίψαι αὖος ἐγὼ καὶ ἀπόλλυμαι· ἀλ<λ>ὰ πιε̑μ {ε} μοι | κράνα<ς α>ἰ<ε>ιρ<ό>ω ἐπ<ὶ> δεξιά· τῆ, κυφάριζος, | τίς δ᾽ ἐ{δε}ζ<ί>; πῶ δ’ ἐζί; Γᾶς υἱός ἠμι κα<ὶ Ὠ>ρανῶ | ἀστερόεντος. |

|

B8 |

Eleutherna, Crete |

III–I c. |

not known |

rectangular, rolled in cylinder? |

not known |

not known |

not known |

δίψᾳ {α} αὖος ἐγὼ καὶ ἀπόλ<λ>υμαι· ἀλ|λὰ π<ι>ε̑μ μο<ι> κράνας αἰενάω ἐπὶ δ|<ε>ξιά· τῆ, κυφάριζος. τίς δ’ ἐζί; πῶ | δ’ <ἐ>ζί; Γᾶς υἱός ἰμι καὶ Ὠρανῶ ἀστερό|εντος {σ}. |

|

B12 |

Sfakaki, Crete |

late III – early I c. |

not known |

rectangular, unfolded |

not known |

not known |

Inhumation in tile(?)-grave I, looted. Thirty-two clay unguentaria, fragments of glass, a bronze mirror, small bronze and gilt fragments |

δίψαι τοι <α>ὖος. παρ<α>π<ό>λλυται. | ἀλλ<ὰ> π{α}ιε̑ν μοι κράνας <Σ?>αύ|ρου ἐπ᾽ ἀ{α}ρι<σ>τερὰ τᾶς κυφ̣α{σ}|ρίζω. τ<ί>ς δ᾽ εἶ ἢ πῶ δ᾽ εἶ; Γᾶ|ς ἠμ{ο}ὶ, μάτηρ· πῶ; τί ΑΕΤ | [κ]α̣ὶ̣ <Ο>ὐρανῶ̣ <ἀ>στε<ρόεντος>. τίς; δίψαι το|. Λ̣ΤΟΙΙΥΤΟΟΠΑΣΡΑΤΑΝΗΟ. |

|

B13 SEG 52.644 |

Eleutherna, Crete |

III–I c. |

not known |

rectangular |

not known |

not known |

not known |

δίψαι το̣ι̣ Ε Ι̣ΤΟΣ παρα- πόλλυται. ἀλ<λ>ὰ πιε̑ν ἐ(μοὶ) (vel πιένε < πιέναι) κράνας ἄ̣π̣ο̣?. |

|

B14 |

Eleutherna, Crete |

late 2nd – early 1st c. |

not known |

rectangular folded |

affixed to tooth |

no |

Inhumation in cist-grave. Few ostraca from two unguentaria |

δίψαι αὖος ἐγὼ καὶ ἀπόλλυμαι· ἀλλὰ πιε̑μ <μ>οι | κράνας αἰειρόω ἐπὶ δεξιά· τῆ, κυφάριζος. | τίς δ᾽ ἐζί; πῶ δ’ ἐζί; Γᾶς υἱός ἠμι κ<α>ὶ Ὠραν{ι}ῶ | ἀστερ<όε>ντος. |

|

B15 |

Eleutherna, Crete |

end of 4th – early 3rd c. |

not known |

rectangular unfolded |

not known |

no |

Inhumation in cist-grave. Clay hydria and eight unguentaria |

δίψαι ΑΤΟΙΥΤΟΣ παρα{π}- πόλλυται. ἀλλὰ πιε̑ν {μ} μοι κρ{ω}άνα<ς> ἀϊρό[ω] ἐπ’ ἀριστερ<ὰ> τᾶς κυφ̣[αρίζ]- ω. τίς δ᾽ εἶ ἢ πῶ δ᾽ [εἶ; Γᾶ?] Μ . . . ΜΑΤΡΗΔΕΜ[ . . 4 . . ]. |

|

E1 |

Eleutherna, Crete |

III–I c. |

not known |

rectangular |

not known |

not known |

not known |

[Πλού]τωνι καὶ Φ- [ερσ]οπόνει χαίρεν. |

|

E4 |

Sfakaki, Crete |

25 BCE -40 CE |

male? |

epistomion |

on the mouth |

bronze on chest |

Inhumation in cist-grave (above no. 8). Clay and bronze prochous, clay unguentarium, lekythion, two glass phialae, a bronze strigil, obsidian flake |

Πλούτωνι Φερσεφόνῃ. |

|

E6 |

Sfakaki, Crete |

25 BCE -50 CE |

female? |

epistomion |

cranium |

no |

Inhumation in cist-grave. Clay, glass and metal objects: clay unguentaria, a lead pyxis, a pair of gold earrings with tiny fayence beads, a gold ring with a standing female in the type of Aphrodite Anadyomene |

Πλούτωνι Φερσεφόνῃ |

|

G2 |

Sfakaki, Crete |

1–50 CE |

male? |

epistomion |

cranium |

silver coin |

Inhumation in Cist-grave 9. Around the feet from the knees down: clay prochous, four glass cups, glass phiale, bronze lekythion, and bronze strigil |

unincised |

|

G3 |

Sfakaki, Crete |

50–100 CE |

female? |

rectangular epistomion |

cranium |

no |

Inhumation in Cist-grave 4. Around the feet: a clay kylix, a clay prochous, four clay unguentaria, glass cup, bronze mirror, lead pyxis, and bronze nails |

unincised |

|

G4 |

Sfakaki, Crete |

I c. CE |

female? |

rectangular epistomion |

cervix bones |

no |

Inhumation in Cist-grave 20. Deceased A buried later than deceased B to the N, and B (an older burial probably of a female) to the S. Around the feet of both: a clay prochous, three aryballos-shaped lekythia, a clay unguentarium, a clay cup, and a glass phiale; deceased A also a bronze coin; deceased B also epistomion, and between the legs bronze foils (from a wooden pyxis?) |

unincised |

Figures

Map of Crete and excavation area (after Tzifopoulos 2010)

Sfakaki, plot of IRIS Hotel Inc.

Sfakaki, plot of IRIS Hotel Inc., Grave 7.

Sfakaki, plot of IRIS Hotel Inc., Grave 7 after completion of the excavation.

Sfakaki, plot of IRIS Hotel Inc., Grave 7, skeletal remains and the gold epistomion (M9).

Sfakaki, plot of IRIS Hotel Inc., Grave 7, bulbous unguentaria.

Sfakaki, plot of IRIS Hotel Inc., Grave 7, lead pyxis.

Sfakaki, plot of IRIS Hotel Inc., Grave 7, gold earrings.

The gold epistomion (M9) of Grave 7 as found

The gold epistomion (M9) of Grave 7 after its cleaning.

© 2022 the author(s), published by De Gruyter.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Titelseiten

- Variations on Violence in Greek and Akkadian Succession Myths

- Introductory Formulas in the Catalogue of Men of Odyssey 11

- Timocreon of Ialysos, frr. 5–8 PMG and 7, 9, and 10 IEG

- Religion on the Rostrum: Euchomai Prayers in the Texts of Attic Oratory

- A New Epistomion from Sfakaki, near Rethymno

- Mapping the stars on the revolving sphere and reckoning time: star catalogues, astronomical popularization, and practical functions

- Prometheus Bound Reappropriated: A Modern Greek Promethean ‘Palimpsest’ by Νikiforos Vrettakos

- List of Contributors

Articles in the same Issue

- Titelseiten

- Variations on Violence in Greek and Akkadian Succession Myths

- Introductory Formulas in the Catalogue of Men of Odyssey 11

- Timocreon of Ialysos, frr. 5–8 PMG and 7, 9, and 10 IEG

- Religion on the Rostrum: Euchomai Prayers in the Texts of Attic Oratory

- A New Epistomion from Sfakaki, near Rethymno

- Mapping the stars on the revolving sphere and reckoning time: star catalogues, astronomical popularization, and practical functions

- Prometheus Bound Reappropriated: A Modern Greek Promethean ‘Palimpsest’ by Νikiforos Vrettakos

- List of Contributors