Abstract

How does support for civil liberties prevail in times of external threat? Simultaneously, how does internal polarisation affect how tightly citizens hold to these liberties? We argue citizens may follow partisanship in evaluating foreign threats, supporting erosion of liberties if co-partisans advocate it in favour of national security. We conduct a survey experiment on a representative sample of 3281 US citizens, treating them with vignettes of potential conflict with China attributed to randomly varying partisanship. We interact such treatments with respondents’ own partisanship, then measure support for various civil liberties. Our findings yield mixed results and we are unable to decisively demonstrate that co-partisans are better at encouraging the surrender of civil liberties. This is congruent with other recent research that also shows partisan polarisation may neither lighten nor worsen in times of external threat.

1 Introduction

With the global rise of authoritarianism, democracies around the world are once again facing increasing external threats from autocratic regimes. In Europe and East Asia, these can be as tangible as military aggression from Russia and China (Aksoy et al. 2024). Democracies at less direct risk of invasion – such as the United States, Canada, and Australia – may still be concerned with external threats in the form of cyberattacks, electoral interference and more.

The salience of foreign threats may prompt citizens to forgo some civil liberties in the interest of national security. This might be particularly relevant when threats come from autocratic states who themselves may be less shackled by such norms at home. Citizens of nominally democratic societies might consider forgoing some of their own liberties to level the playing field. This has been shown in the presence of terror threats (Huddy et al. 2005).

In this study, we further the question on citizen support for civil liberties – but give particular focus to how partisanship might moderate this connection. Previous research tells us that the beliefs of the respondents (Cohrs et al. 2005; Hetherington and Suhay 2011) or the politics of the threat perpetrator (Caton and Mullinix 2023; Jäger 2023) interact with how respondents evaluate threats and any subsequent surrender of liberties. This study expands this line of inquiry by instead varying the partisanship of the messenger of the threat. We expect that respondents will be more willing to surrender liberties when co-partisan messengers deliver the warnings.

To this end, we conduct a survey experiment in the United States. In this experiment, respondents are exposed to reports of external threats from authoritarian regimes, with the source of the reports – either co-partisan, out-partisan or non-partisan – varied randomly. We then measure respondent support for six measures of civil liberties that might be associated with a healthy, liberal democracy. Our findings are, at best, mixed and we are unable to decisively demonstrate that a co-partisan messenger better elicits a surrender of civil liberties. Whilst responses to some indicators are suggestive of partisanship intervening in the evaluation of the messages, the direction of this effect does not always follow the prediction that co-partisan messages will best prompt restrictions on liberties.

Whilst there does appear to be ample evidence that partisan cues shape public opinion (Bolsen et al. 2014; Druckman et al. 2013; Kingzette et al. 2021; Nicholson 2012), the actual downstream consequences of polarisation on political outcomes remains uncertain (Broockman et al. 2023). We contribute more specifically to the growing body of research into how partisanship and polarisation operate on a backdrop of external threats. Existing work has shown how polarisation may colour public opinion on foreign intervention (Maxey 2022), threat perceptions and the use of force (Myrick 2021; Schwartz and Tierney 2025; Yeung and Xu 2025) in this context. We turn this question away from external security matters to instead focus on public support for civil liberties. In doing so, we link this active literature on external threats to the longer standing literature on civil liberties in the presence of threats (Davis and Silver 2004; Huddy et al. 2005). Such papers have primarily focused on the threat of terrorism. This paper may also speak to preferences over civil liberties under related forms of strain, such as health security in a pandemic (Alsan et al. 2023; Vasilopoulos et al. 2023).

2 Threats, Liberties and Partisanship

Research on threats in the US gained momentum following the Patriot Act and the War on Terror – with particular emphasis on the threat of terrorism. Huddy et al. (2005) show that respondents perceiving more future terror were bigger supporters of liberty restrictions. Davis and Silver (2004) further show this to interact with trust in government, whilst Gadarian (2010) shows moderation through emotion and media framing. These findings establish a baseline assumption that liberties may be surrendered in the face of threats.

Threats are partisan experiences. Both perceiving threats and subsequent support for liberties have been shown to vary by ideology. In the terror literature, latent pro-authoritarian ideology predicts both greater terror threat perception and support for liberty restriction (Cohrs et al. 2005), but even anti-authoritarians can become more hawkish and illiberal when confronted with terror threats (Hetherington and Suhay 2011). More recently, Caton and Mullinix (2023) and Jäger (2023) focus on whether different types of terror perpetrators evoke different reactions. They find that partisanship occasionally matters, with political leaning interacting differently with “White Nationalist” versus “Islamist” terror labels to determine support for liberties.

In the selected literature, the role of partisanship in evaluating threats and liberties is focused on either the ideology of the respondent (Cohrs et al. 2005; Hetherington and Suhay 2011) or the ideology of the threat perpetrator (Caton and Mullinix 2023; Jäger 2023). Our study instead asks about how the partisanship of the messenger plays into the potential surrender of liberty.

We argue that, in politically polarised societies, the evaluation of threats and subsequent surrender of liberties may happen through partisan lenses. Increasing political polarisation in liberal democracies across the world threatens democratic institutions from within (McCoy and Somer 2019). Individual-level support for democratic principles is fragile and often overwhelmed by partisanship and ideology (Graham and Svolik 2020; Saikkonen and Christensen 2023; Svolik 2019, 2020; Svolik et al. 2023), and this can enable politicians to justify anti-democratic policies in retaliation (Haggard and Kaufman 2021; Simonovits et al. 2022). Consequently, a partisan individual may consider a threat more serious when highlighted by a co-partisan. Our expectation is that respondents are thus more likely to support suspending civil liberties when threats are communicated by a co-partisan.

To test this possibility, we move away from terrorism to instead focus on threats in the context of Great Power competition. With present day tensions in mind, recent scholarship on threats and partisanship has appropriately focused on the partisan implications of external threats. We thus look to intersect the existing literature on threats (of terror) and liberties with presently growing research on external threats. This latter literature has looked for how partisanship can condition citizen support for foreign intervention (Maxey 2022) and use of force (Myrick 2021) when primed with external threats. Schwartz and Tierney (2025) and Yeung and Xu (2025) follow the example of Myrick (2021), further studying polarisation by measuring perceptions of threat levels and support for force in the same context of US-China relations. We extend this line of inquiry, but turn away from military matters in our outcomes of interest towards implications for civil liberties.

3 Materials and Methods

We investigate the relationship between partisanship and liberties in the context of international tensions in the United States through a battery of questions included in the American Social Survey (TASS) conducted by the Weidenbaum Center on the Economy, Government and Public Policy. Wave 1 of the 2023 edition of TASS was implemented by YouGov using a national probability sample of 3281 US adults interviewed online between 16th and 20th October 2023, weighted by gender, age, race, education, party identification and past voting record.

Specific details on polling methodology and survey implementation can be found with the Supplementary Materials, but we provide brief descriptive statistics of the sample here. 63 % of respondents were White, 13 % Black and 16 % Hispanic. 51 % of the sample was female, 33 % held a college degree, 71 % were registered to vote and the mean age was just under 48 years. Partisanship was asked on a seven-point scale. For analyses where partisanship will be invoked, we exclude pure Independents and those uncertain (749 respondents) – consolidating Democratic and Republican respondents (just over 2,500 respondents).

Eight batteries of questions were part of the main body of the survey. In our battery, respondents were randomly assigned one of three variations of the following vignette as treatment.

“A recent report from a non-partisan/Democratic-leaning/Republican-leaning thinktank says that the risk of conflict between the United States and China is higher than any time since the end of the Cold War. According to the report, the experts from the non-partisan/Democratic-leaning/Republican-leaning thinktank say that:

– China is aggressively expanding its economic and military influence, as well as nuclear capabilities.

– China is using intelligence services to steal information and spy on U.S. citizens.

– China has the ability to launch cyber attacks that can disrupt critical infrastructure – such as electric grids or natural gas pipelines – in the United States.”

Our vignette builds upon the design used in study 3 of Myrick (2021), but updated to reflect the political environment at the time the survey was administered. Myrick (2021), in 2019, similarly primed respondents on the growing threat of China to US national security, but framed as statements of the Donald J. Trump administration (under some treatment conditions). Our study was conducted in late 2023 with Joseph R. Biden in the Oval Office, and thus we altered the statements to be from thinktanks. To this extent, the content of the vignettes do indeed reflect what one might read from a US-based thinktank around the time of the experiment, such as publications of the Brookings Institution (Kerry et al. 2023) or the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) (Lin et al. 2023).

A set of six questions measures support for various civil liberties, our outcome of interest, as follows

Q1 “How likely are you to support a politician that advocates banning certain social media platforms in the interest of national security?”

Q2 “To what extent do you agree or disagree with the following statement? US authorities should more frequently inspect content on social media platforms in the interest of national security.”

Q3 “To what extent do you agree or disagree with the following statement? The federal government should prosecute American citizens who use banned foreign software.”

Q4 “To what extent do you support or oppose this statement? American citizens with family or business ties with foreign governments should become ineligible for political office.”

Q5 “To what extent do you support or oppose this statement? On matters relevant to national security, the President may ignore Supreme Court decisions.”

Q6 “To what extent do you support or oppose this statement? The federal government should more strictly limit immigration from unfriendly nations, such as China.”

Responses to all six outcome questions were elicited on a seven-point scale. For each question, a response “higher” on the scale thus corresponds to a preference for greater restrictions on the highlighted civil liberty.

We understand civil liberties in the broadest sense, as a loose group of freedoms that one might normatively believe governments should not encroach upon. Our outcome items do not overtly ask about particular liberties, but rather phrase the questions to be about topics related to liberties prominent in public discussion around the time of the survey experiment and relevant to US-China relations.

The first three outcome items (Q1, Q2, Q3) were informed by national security concerns around TikTok – a social media and video sharing platform of Chinese origin – and thus ask about social media content and software usage. (Notably TikTok itself is not referenced anywhere in the treatment or survey.) Such questions touch upon ideas of privacy and freedom of expression, particularly in the digital sphere. Digital control and surveillance may well be the most realistic way in which the average contemporary citizen see their liberties encroached upon – and are therefore our primary outcomes of interest.

Q5 touches on the independence of the judiciary, which may be understood as a necessary component for the protection of civil liberties. This is particularly so in contexts of foreign threat, where the courts may stand in the way of executives wishing to suspend the liberties of certain undesirables.

The remaining two questions, Q4 and Q6, may be particularly unusual inclusions. Rather than being relevant to the immediate experience of the average American, they instead concern topics also relevant to non-Americans and are more exploratory in nature. While these might not be about civil liberties in a traditional sense, we wanted to include questions that more directly address the possibility of ‘foreign agents’ and related entities that often become the rationale for restriction of liberties in times of threat. To this end, Q4 asks about restricting the political rights of Americans with foreign connections and Q6 asks about immigration.

4 Results

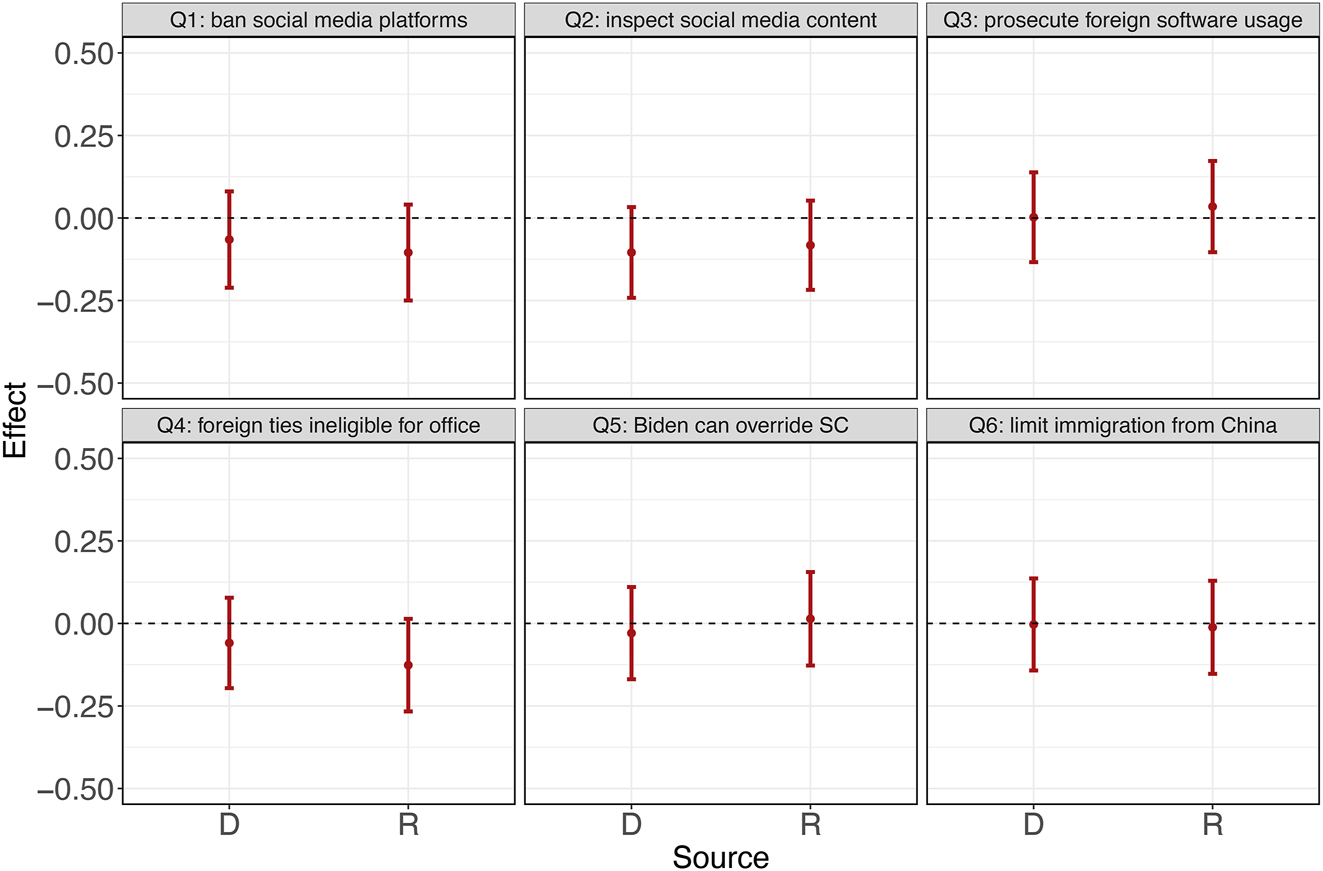

Before we consider respondent partisanship, we first present the aggregate results of receiving different treatments without accounting for respondent partisanship. Thus, Figure 1 and Table 1 show the marginal effect of receiving a Democratic-attributed and Republican-attributed vignette compared to receiving the non-partisan vignette for all respondents collectively using ordinary least squares (OLS) models with robust standard errors. Unsurprisingly, there are no significant differences in respondent preference for the restriction of civil liberties at this stage.

Marginal effects of partisan-attributed treatments on responses to outcome questions (compared to non-partisan-attributed).

Marginal effects of partisan-attributed treatments on responses to outcome questions (compared to non-partisan-attributed) using OLS with robust standard errors.

| Outcome question | Source partisanship | Mean | St. dev. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Q1: Ban social media platforms | Democratic | −0.0653 | 0.0744 |

| Republican | −0.105 | 0.0741 | |

| Intercept | 4.32 | 0.0529 | |

| Q2: Inspect social media content | Democratic | −0.104 | 0.0701 |

| Republican | −0.0825 | 0.0689 | |

| Intercept | 4.73 | 0.0487 | |

| Q3: Prosecute foreign software usage | Democratic | 0.00233 | 0.0693 |

| Republican | 0.0346 | 0.0705 | |

| Intercept | 4.30 | 0.001 | |

| Q4: Foreign ties ineligible for office | Democratic | −0.0591 | 0.0698 |

| Republican | −0.126 | 0.0715 | |

| Intercept | 4.47 | 0.0491 | |

| Q5: Biden can override SC | Democratic | −0.0294 | 0.0712 |

| Republican | 0.0141 | 0.0722 | |

| Intercept | 3.32 | 0.0501 | |

| Q6: Limit immigration from China | Democratic | −0.00309 | 0.0711 |

| Republican | −0.0117 | 0.0719 | |

| Intercept | 4.76 | 0.0507 |

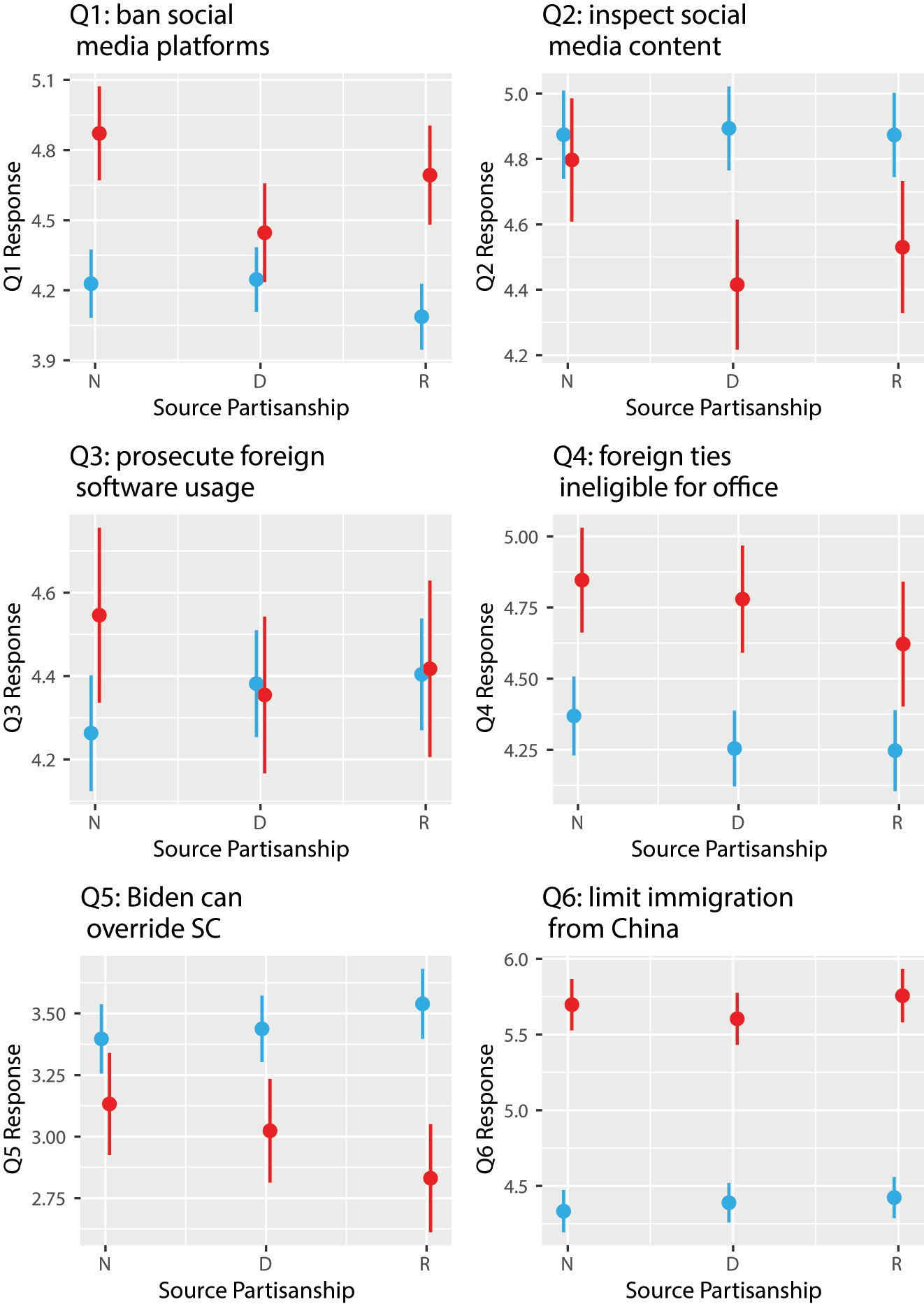

We now move to consider respondent partisanship in its interaction with receiving the various treatments in Figure 2 and Table 2, again using OLS with robust standard errors.

Responses to outcome questions disaggregated by respondent partisanship with Democratic respondents in blue and Republican respondents in red.

Interaction of source partisanship and respondent partisanship for different outcome questions using OLS with robust standard errors.

| Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic source | 0.018 | 0.019 | 0.119 | −0.114 | 0.041 | 0.056 |

| (0.103) | (0.095) | (0.096) | (0.098) | (0.099) | (0.097) | |

| Republican source | −0.142 | −0.001 | 0.141 | −0.122 | 0.142 | 0.090 |

| (0.104) | (0.095) | (0.098) | (0.101) | (0.102) | (0.099) | |

| Republican respondent | 0.643*** | −0.077 | 0.283* | 0.477*** | −0.264* | 1.365*** |

| (0.127) | (0.118) | (0.128) | (0.117) | (0.128) | (0.112) | |

| Democratic source × Republican respondent | −0.443* | −0.401* | −0.310 | 0.047 | −0.150 | −0.150 |

| (0.181) | (0.169) | (0.173) | (0.166) | (0.180) | (0.157) | |

| Republican source × Republican respondent | −0.037 | −0.266 | −0.270 | −0.103 | −0.444* | −0.031 |

| (0.181) | (0.170) | (0.181) | (0.177) | (0.185) | (0.159) | |

| (Intercept) | 4.228*** | 4.874*** | 4.263*** | 4.369*** | 3.397*** | 4.333*** |

| (0.075) | (0.069) | (0.071) | (0.070) | (0.072) | (0.071) | |

| R 2 | 0.021 | 0.011 | 0.002 | 0.019 | 0.018 | 0.133 |

| Num. obs. | 2,511 | 2,502 | 2,504 | 2,508 | 2,507 | 2,500 |

-

***p < 0.001; *p < 0.05.

Across the six outcome questions, the results are mixed, with no obvious overall support for our expectation that co-partisan messengers are more likely to elicit restrictions on liberty. Partisanship, broadly speaking, seems to be consequential in responses to Q1, Q2 and Q5 – though not in line with our expectations. Partisans could not be differentiated on Q3, Q4 and Q6. We proceed to discuss each indicator in more length.

For Q1, it can be seen that Republican respondents are significantly more in favour of social media platform bans than Democratic respondents in the non-partisan and Republican thinktank treatments. However, the significance of this effect disappears when the thinktank is labeled Democratic. Republican respondents appear to particularly support government bans of social media platforms when it is not a Democratic voice advocating for it.

As for Q2 – inspecting social media content – partisans are not of significantly different views in the non-partisan treatment. They do diverge when partisanship is introduced in the attribution, with Democratic respondents now significantly more supportive of inspections for both partisan messages.

A similar effect can be observed in Q5. In the non-partisan treatment, Democratic and Republican respondents are not significantly different in support for Executive primacy over the courts. This changes when partisanship is cued in the vignettes, with Republican respondents now significantly less supportive and Democratic respondents more supportive, regardless of which party is in attribution.

How might we interpret this outcome? Note that this survey experiment was conducted when Biden was US President. Whilst Biden was never specifically named in the vignettes nor in the outcome questions, it is reasonable to presume (and indeed we intended for) respondents to read this question as broadening Biden’s powers specifically. References to the incumbent government in earlier parts of TASS broadly also strengthen this possibility. From this perspective, it might follow that, when partisanship is cued, respondents support restriction of liberties when their co-partisans are in power and oppose such restrictions if out-partisans hold power. This is reflected in the results for Q2 and Q5. A post hoc understanding of these results might thus interpret that partisanship does matter for the evaluation of liberties, but conditional on which party holds power.

The remaining three questions do not produce partisan results across the various conditions. For Q4 and Q6, respondents of different partisanships are significantly in disagreement in these outcomes regardless of treatment. Republican respondents are always significantly more in support of restricting office for those with foreign ties and restricting immigration from “unfriendly nations” across all treatment conditions. Notably, these are the exact two exploratory questions that touch specifically on non-American foreigners. Perhaps for such topics, the partisan gap is too large to be bridged by the types of treatments we use.

On the opposite end, respondents of different partisanships cannot be significantly separated in Q3 regardless of treatment. There is no significant difference in the support for penalties for the use of banned foreign software between partisans across all treatment conditions. This is perhaps a topic that Americans cannot be moved on with the vignettes we use.

5 Discussion and Conclusion

Our results are unable to decisively support our predicted connection between partisanship and support for restricting civil liberties. On its own, it may be difficult to use our results to draw broad conclusions. Comparisons with other recent results on adjacent research questions may yet suggest some patterns, however.

The results of this paper are somewhat reflective of the broader literature set in the context of external threats. Both Myrick (2021) and Yeung and Xu (2025) concluded that external threats were not able to cause polarisation both in general and on the topic of use of force. (Note that Myrick (2021) was actually looking for threats to reduce polarisation, but nonetheless found no significant effects in either direction.) Our experiment was, of course, instead focused on civil liberties in a broad sense. The lack of any decisive results in our paper may suggest that opinions on liberties operate similar to opinions on use of force – they may not be directly related to political polarisation.

One reason our experiment may not have shown expected effects may be due to insufficiently strong stimuli. Our vignettes invoked thinktanks instead of the office of the President (Myrick 2021) or presidential candidates (Yeung and Xu 2025) – and thinktanks are certainly weaker sources of partisan opinion than actual leading party figures. Our stimuli were also not reinforced by writing tasks. Weak stimuli may thus explain our lack of decisive results. Schwartz and Tierney (2025) argue that the “vividness” of threats matter in their relation to polarisation. That said, their experiment, which varied the level of detail and specificity with which threats were primed, found that vividness of threats alone was still not able to move respondents.

Collectively, our results, in combination with results in the broader literature, seem to indicate that partisanship may not be especially important in the context of external threats. This applies to both the possibility of external threats uniting and exacerbating polarised societies. Our efforts here, focused on particular interpretations of civil liberties, add a further angle to other results on threat perceptions and use of force in similar settings. Overall, these may be lessons about modern societies that encourage optimism.

Funding source: Weidenbaum Center on the Economy, Government and Public Policy

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge support from the Weidenbaum Center on the Economy, Government and Public Policy. We also thank invaluable contributions from Taylor N. Carlson, Rex Weiye Deng, Ted Enamorado, Leonie Hong, Heidi Tang and Tony Zirui Yang.

-

Competing interests: We declare no further competing interests with regards to the authorship of this manuscript.

References

Aksoy, Deniz, Ted Enamorado, and Tony Zirui Yang. 2024. “Russian Invasion of Ukraine and Chinese Public Support for War.” International Organisation 78 (2): 341–60. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0020818324000043.Search in Google Scholar

Alsan, Marcella, Luca Braghieri, Sarah Eichmeyer, Minjeong Joyce Kim, Stefanie Stantcheva, and David Y. Yang. 2023. “Civil Liberties in Times of Crisis.” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 15 (4): 389–421. https://doi.org/10.1257/app.20210736.Search in Google Scholar

Bolsen, Toby, James N. Druckman, and Fay Lomax Cook. 2014. “Influence of Partisan Motivated Reasoning on Public Opinion.” Political Behaviour 36: 235–62. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-013-9238-0.Search in Google Scholar

Broockman, David E., Joshua L. Kalla, and Sean J. Westwood. 2023. “Does Affective Polarisation Undermine Democratic Norms or Accountability? Maybe Not.” American Journal of Political Science 67 (3): 808–28. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12719.Search in Google Scholar

Caton, Cora, and Kevin J. Mullinix. 2023. “Partisanship and Support for Restricting the Civil Liberties of Suspected Terrorists.” Political Behaviour 45: 1421–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-022-09771-9.Search in Google Scholar

Cohrs, J. Christopher, Sven Kielmann, Jürgen Maes, and Barbara Moschner. 2005. “Effects of Right-Wing Authoritarianism and Threat from Terrorism on Restriction of Civil Liberties.” Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy 5 (1): 263–76. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-2415.2005.00071.x.Search in Google Scholar

Davis, Darren W., and Brian D. Silver. 2004. “Civil Liberties Versus Security: Public Opinion in the Context of the Terrorist Attacks on America.” American Journal of Political Science 48 (1): 28–46. https://doi.org/10.2307/1519895.Search in Google Scholar

Druckman, James N., Erik Peterson, and Rune Slothuus. 2013. “How Elite Partisan Polarisation Affects Public Opinion Formation.” American Political Science Review 107 (1): 57–79. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0003055412000500.Search in Google Scholar

Gadarian, Shana Kushner. 2010. “Politics of Threat: How Terrorism News Shapes Foreign Policy Attitudes.” The Journal of Politics 72 (2): 469–83. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0022381609990910.Search in Google Scholar

Graham, Matthew H., and Milan W. Svolik. 2020. “Democracy in America? Partisanship, Polarisation and the Robustness of Support for Democracy in the United States.” American Political Science Review 114 (2): 392–409. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0003055420000052.Search in Google Scholar

Haggard, Stephan, and Robert Kaufman. 2021. Backsliding: Democratic Regress in the Contemporary World. Cambridge University Press.10.1017/9781108957809Search in Google Scholar

Hetherington, Marc, and Elizabeth Suhay. 2011. “Authoritarianism, Threat and Americans’ Support for the War on Terror.” American Journal of Political Science 55 (3): 546–60. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2011.00514.x.Search in Google Scholar

Huddy, Leonie, Stanley Feldman, Charles Taber, and Gallya Lahav. 2005. “Threat, Anxiety and Support of Anti-Terrorism Policies.” American Journal of Political Science 49 (3): 593–608. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2005.00144.x.Search in Google Scholar

Jäger, Felix. 2023. “Security Versus Civil Liberties: How Citizens Cope with Threat, Restriction and Ideology.” Frontiers of Political Science 4.10.3389/fpos.2022.1006711Search in Google Scholar

Kerry, Cameron F., Mary E. Lovely, Pavneet Singh, Liza Tobin, Ryan Hass, Patricia M. Kim, et al.. 2023. Is US Security Dependent on Limiting China’s Economic Growth? Written Debated Published by the Brookings Institution.Search in Google Scholar

Kingzette, Jon, James N. Druckman, Samara Klar, Yanna Krupnikov, Matthew Levendusky, and John Barry Ryan. 2021. “How Affective Polarisation Undermines Support for Democratic Norms.” Political Opinion Quarterly 85 (2): 663–77. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfab029.Search in Google Scholar

Lin, Bonny, Brian Hart, Matthew P. Funaiole, and Samantha Lu. 2023. China’s 20th Party Congress Report: Doubling Down in the Face of External Threats. Commentary Published by Center for Strategic and International Studies.Search in Google Scholar

Maxey, Sarah. 2022. “Finding the Water’s Edge: When Negative Partisanship Influences Foreign Policy Attitudes.” International Politics 59: 802–26. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41311-021-00354-9.Search in Google Scholar

McCoy, Jennifer, and Murat Somer. 2019. “Toward a Theory of Pernicious Polarisation and How it Harms Democracies: Comparative Evidence and Possible Remedies.” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 681 (1): 234–71. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716218818782.Search in Google Scholar

Myrick, Rachel. 2021. “Do External Threats Unite or Divide? Security Crises, Rivalries and Polarization in American Foreign Policy.” International Organisation 75 (4): 921–58. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0020818321000175.Search in Google Scholar

Nicholson, Stephen P. 2012. “Polarising Cues.” American Journal of Political Science 56 (1): 52–66. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2011.00541.x.Search in Google Scholar

Saikkonen, Inga A.-L., and Henrik Serup Christensen. 2023. “Guardians of Democracy or Passive Bystanders? A Conjoint Experiment on Elite Transgressions of Democratic Norms.” Political Research Quarterly 76 (1): 127–42. https://doi.org/10.1177/10659129211073592.Search in Google Scholar

Schwartz, Joshua A., and Dominic Tierney. 2025. “Us and Them: Foreign Threat and Domestic Polarisation.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 69 (2–3): 352–80. https://doi.org/10.1177/00220027241246539.Search in Google Scholar

Simonovits, Gabor, Jennifer McCoy, and Levente Littvay. 2022. “Democratic Hypocrisy and Out-Group Threat: Explaining Citizen Support for Democratic Erosion.” The Journal of Politics 84 (3): 1806–11. https://doi.org/10.1086/719009.Search in Google Scholar

Svolik, Milan W. 2019. “Polarisation Versus Democracy.” Journal of Democracy 30 (3): 20–32. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2019.0039.Search in Google Scholar

Svolik, Milan W. 2020. “When Polarisation Trumps Civic Virtue: Partisan Conflict and the Subversion of Democracy by Incumbents.” Quarterly Journal of Political Science 15 (1): 3–31. https://doi.org/10.1561/100.00018132.Search in Google Scholar

Svolik, Milan W., Elena Avramovska, Johanna Lutz, and Filip Milačić. 2023. “In Europe, Democracy Erodes from the Right.” Journal of Democracy 34 (1): 5–20. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2023.0000.Search in Google Scholar

Vasilopoulos, Pavlos, Haley McAvay, Sylvain Brouard, and Martial Foucault. 2023. “Emotions, Governmental Trust and Support for the Restriction of Civil Liberties During the Covid-19 Pandemic.” European Journal of Political Research 62 (2): 422–42. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12513.Search in Google Scholar

Yeung, Eddy S. F., and Weifang Xu. 2025. “Do External Threats Increase Bipartisanship in the United States? An Experimental Test in the Shadow of China’s Rise.” Political Science: Research and Methods, First View 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2024.60.Search in Google Scholar

Supplementary Material

This article contains supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/spp-2025-0047).

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.