Abstract

This study examines the economic and geopolitical determinants of Indonesia’s defense expenditure from 1984 to 2022 using the Autoregressive Distributed Lag (ARDL) model to capture both short-term and long-term dynamics. Recognizing the contextual relevance of Indonesia’s Total People’s Defense and Security System (SISHANKAMRATA), the analysis relies on conventional military expenditure data (% of GDP) due to the absence of consolidated multi-ministerial records. The results show that in the short run, defense spending is highly sensitive to macroeconomic shocks: inflation, exchange rate volatility, and foreign direct investment exert negative effects, while debt, trade openness, and regional military expenditure strengthen budgetary allocations. In the long run, macroeconomic fundamentals (debt, growth, inflation, and foreign investment) together with neighboring countries’ military spending drive defense expenditure, whereas regional average spending has a negative effect and U.S. military expenditure does not show a structural impact. These findings underscore the dual pressures of fiscal fragility and regional security competition in shaping Indonesia’s defense budget. Policy implications highlight the importance of inflation-adjusted and exchange rate–resilient budgeting, sustainable financing mechanisms such as defense bonds or a Defense Sovereign Wealth Fund (D-SWF), and deeper ASEAN defense cooperation to balance security needs with fiscal discipline. This study contributes a macro-level perspective on defense economics under conditions of institutional fragmentation, offering a framework for future comparative and panel-based research across decentralized security systems.

1 Introduction

In an increasingly complex geopolitical environment, defense expenditure has emerged as a critical element of national security and policy planning. As a maritime and archipelagic state, Indonesia faces strategic challenges in safeguarding sovereignty while balancing developmental priorities. Historically, Indonesia’s defense spending has remained below 1 % of GDP, highlighting significant constraints in addressing its security requirements amid evolving regional and global dynamics (Stockholm International Peace Research Institute [SIPRI], 2023).

Unlike many nations where military expenditure is consolidated under a single defense ministry, Indonesia adopts the Total People’s Defense and Security System (Sistem Pertahanan dan Keamanan Rakyat Semesta or SISHANKAMRATA), which distributes defense-related funding across multiple ministries. This unique structure implies that the frequently cited 0.7 % of GDP figure does not fully capture the true scale of defense-related spending, as significant portions of military-related expenditures are managed by non-defense institutions. Simulations suggest that the effective defense spending under SISHANKAMRATA could be closer to 6.3–7.8 % of GDP, incorporating both military (Kemenhan) and non-military (other ministries) components. These figures are indicative estimates based on aggregating budget components from the Ministry of Defense and selected non-defense ministries believed to contribute to national defense under the SISHANKAMRATA framework (e.g., ministries of transportation, state-owned enterprises, and maritime affairs). Due to the absence of a unified dataset and the lack of publicly disaggregated data by function, these estimates remain approximations and are not used in formal model estimation.

However, due to the absence of consolidated time-series data that fully captures multi-ministerial defense allocations under the SISHANKAMRATA framework, this study utilizes conventional military expenditure data (% of GDP) as reported by SIPRI and the World Bank. While this indicator may underestimate actual defense commitments, it remains the most consistent and internationally comparable metric currently available. This limitation is acknowledged explicitly in our analysis and is further discussed in the methodology and conclusion sections as an avenue for future research.

Defense expenditure is influenced by a variety of economic and geopolitical factors, including GDP growth, inflation, foreign debt, and regional security threats (Fordham and Walker 2005). The trade-offs between defense and civilian priorities are particularly pronounced in developing economies, where budgetary constraints often limit military modernization and operational readiness (Kennedy 2017). The “Guns and Butter” model illustrates this fundamental dilemma, highlighting the need for strategic allocation between security and socioeconomic development. Under this framework, governments must decide how to allocate limited fiscal resources between military spending (“guns”) and social investments such as healthcare, education, and infrastructure (“butter”). Indonesia’s SISHANKAMRATA framework serves as an adaptive mechanism within this trade-off, ensuring that national security remains a shared responsibility across different government sectors while enabling fiscal efficiency. While this framework remains institutionally important, this study does not claim to empirically capture SISHANKAMRATA’s internal budget mechanics. Instead, it provides macro-level estimates using conventional data, with SISHANKAMRATA serving as a background for interpreting fiscal fragmentation.

Prior studies suggest that defense spending in developing nations can enhance economic stability if aligned with broader fiscal and security strategies (Deger and Sen 1995). However, existing research lacks a comprehensive econometric model that captures the unique interplay of Indonesia’s economic structure, its SISHANKAMRATA framework, and evolving geopolitical challenges in shaping defense expenditure. To bridge this gap, this study employs the Autoregressive Distributed Lag (ARDL) model to analyze both short-term and long-term relationships between economic variables and military spending. The ARDL approach is particularly suitable for this study as it accommodates mixed orders of integration (I(0) and I(1)), providing robust insights into dynamic fiscal relationships (Pesaran and Smith 2016).

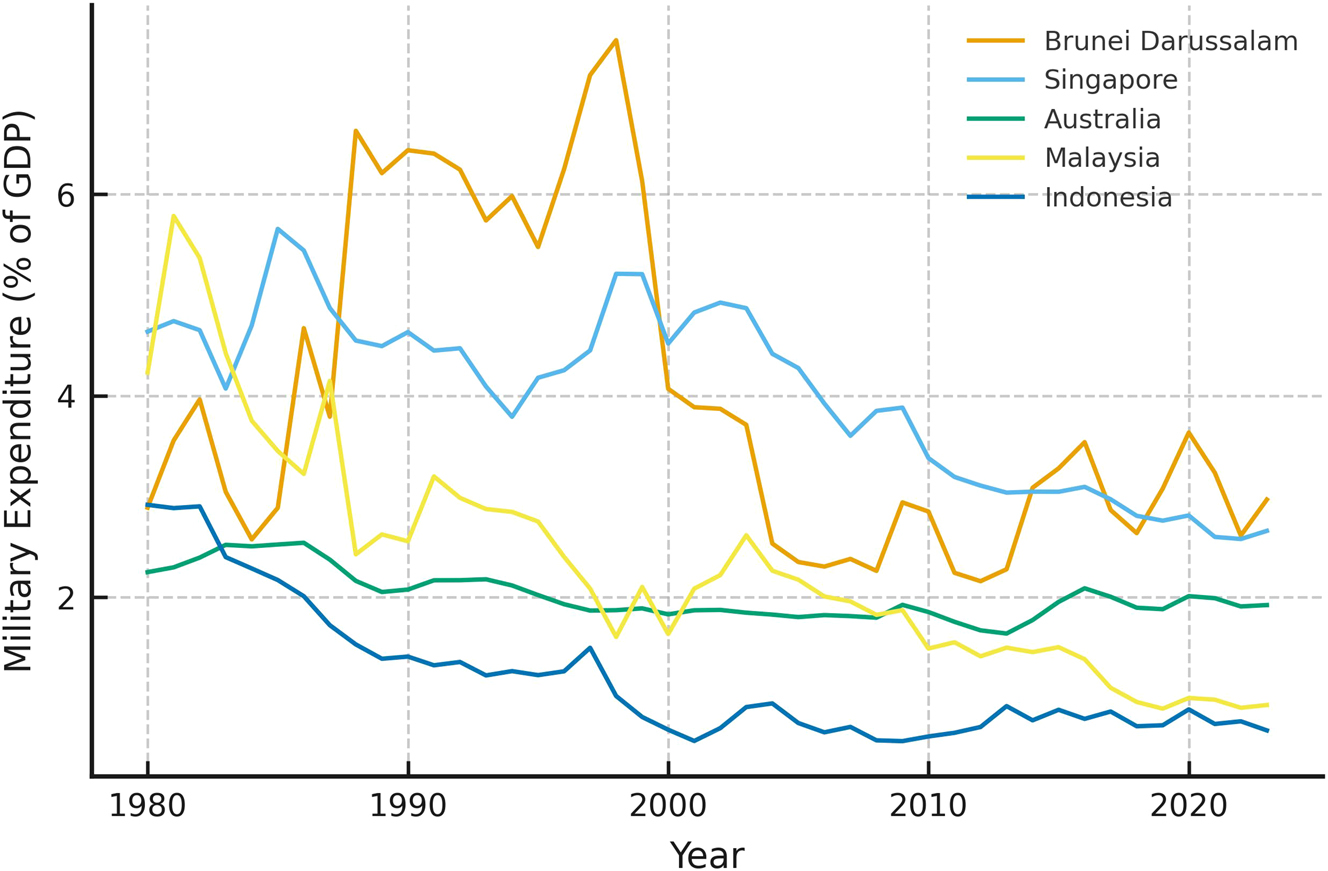

Despite Indonesia’s strategic geographical position and increasing security challenges, its defense budget has remained relatively low compared to its regional counterparts. Figure 1 presents the military expenditure of the world’s leading military powers, showing that major economies allocate a substantial percentage of their GDP to defense. In contrast, Indonesia’s spending as a percentage of GDP is notably lower than regional counterparts such as Singapore, Brunei Darussalam, Australia, and Malaysia, as illustrated in Figure 1.

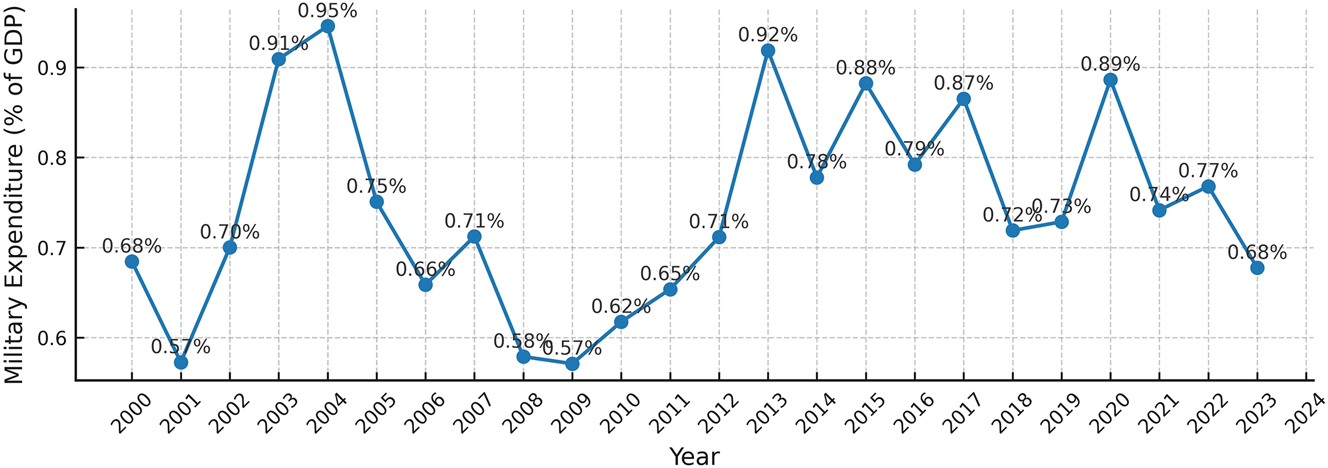

While Singapore and Australia consistently allocate between 3 and 6% of their GDP to defense, Indonesia’s military expenditure has remained below 1 % of GDP for decades. Brunei and Malaysia also tend to outspend Indonesia in relative terms, reflecting different strategic priorities and fiscal policies. This persistent gap in military expenditure raises concerns about Indonesia’s defense readiness in the face of regional security threats, maritime disputes, and military modernization efforts by neighboring countries. However, given the SISHANKAMRATA framework, it is important to reassess whether Indonesia’s defense budget is as limited as commonly perceived or if its unique security structure ensures a broader distribution of military-related spending across government institutions. Furthermore, historical trends in Indonesia’s defense budget (Figure 2) indicate a steady but relatively slow increase in absolute spending since 2000. However, this increase does not significantly alter the country’s standing in the regional defense hierarchy, as the allocation remains relatively stagnant in percentage terms. Unlike some neighboring countries that implement sharp increases in military spending in response to security concerns, Indonesia’s defense budget shows continuity rather than adaptation to evolving geopolitical dynamics.

The stagnation of Indonesia’s defense expenditure presents a critical economic and policy dilemma. Policymakers must balance military preparedness with fiscal responsibility, ensuring that defense spending remains efficient, sustainable, and strategically aligned. The SISHANKAMRATA model, while comprehensive, requires enhanced coordination to optimize the effectiveness of both military and non-military defense components.

Economic theories such as the “Guns and Butter” model underscore the inherent trade-offs in budget allocation between military and civilian priorities (Kennedy 2017). Developing nations, including Indonesia, often face budgetary constraints, making it difficult to modernize defense capabilities while simultaneously funding healthcare, education, and infrastructure development. While SISHANKAMRATA seeks to mitigate these challenges by embedding national defense across multiple institutions, the efficiency of its implementation and the clarity of its financial structure remain key concerns.

Research by Deger and Sen (1995) suggests that defense spending, if strategically aligned, can contribute positively to economic stability. However, Indonesia’s stagnant military expenditure despite its complex security needs raises concerns about its ability to address emerging security challenges while ensuring fiscal sustainability. Unlike major military powers that treat defense spending as an economic multiplier, Indonesia has prioritized developmental goals over military expansion, which raises questions about the long-term sustainability of its defense posture within an increasingly complex regional security environment. This study seeks to clarify these concerns by providing an econometric analysis of Indonesia’s defense spending within the dual constraints of economic management and security strategy, incorporating the nuances of SISHANKAMRATA into the broader policy discourse.

While the SISHANKAMRATA doctrine provides important context for understanding Indonesia’s defense structure, this study does not attempt to quantify its financial structure. Instead, the paper focuses on macroeconomic and geopolitical determinants of defense spending using conventional ARDL methods.

By applying the ARDL approach to macroeconomic and geopolitical drivers while contextualizing results within Indonesia’s institutional environment, we provide a replicable and expandable model for future studies that aim to integrate more detailed institutional data.

2 Literature Review

Research on military expenditure has grown considerably over the past two decades, reflecting increasing concern over how defense spending interacts with economic, political, and strategic variables. Seminal works such as those by Deger and Sen (1995) emphasized the dual role of defense budgets in promoting national security while potentially crowding out social investments in developing economies. More recently, Dunne and Tian (2017)offered a comprehensive overview of global military spending patterns, highlighting macroeconomic conditions, fiscal space, and external threats as key determinants.

Autoregressive Distributed Lag (ARDL) models have become popular for analyzing the short- and long-run dynamics of military expenditure. Aiyedogbon et al. (2012) applied ARDL to assess the impact of inflation on defense spending in Nigeria, finding a negative long-run relationship due to real-term erosion of budget value. Azam and Feng (2017) explored the link between military expenditure and external debt in Asian economies, indicating that higher debt ratios often accompany increased defense burdens. Pacific et al. (2017) investigated how military expenditure affects foreign direct investment and trade performance in Cameroon, again using time-series econometrics to account for dynamic interactions.

In the context of regional and geopolitical influences, Yalta and Yalta (2022) examined the Gulf region using ARDL and panel techniques, finding strong correlations between neighboring states’ military investments. Yesilyurt and Elhorst (2017) employed a dynamic spatial panel model to show that a country’s military budget is influenced by regional arms races, especially when border tensions are present. Christie (2019) focused on Europe, exploring the role of fiscal flexibility and NATO obligations in shaping military spending levels.

Despite this growing literature, few studies have incorporated institutional complexity into quantitative defense models. Most rely on unified budgeting systems, whereas Indonesia’s Total People’s Defense and Security System (Sistem Pertahanan dan Keamanan Rakyat Semesta, or SISHANKAMRATA) creates a fragmented spending structure in which multiple ministries share responsibility for defense-related expenditures. This institutional distinction has rarely been explored empirically, largely due to the lack of integrated, longitudinal data.

Moreover, while ASEAN countries like Singapore and Malaysia are often featured in defense economics literature for their relatively high defense-to-GDP ratios, Indonesia’s strategic budgeting behavior remains underexamined. The country’s relatively low official military expenditure under 1 % of GDP according to SIPRI and the World Bank – masks a broader network of defense activities funded through non-defense ministries. This study addresses this gap by using a macro-fiscal and geopolitical framework while acknowledging the institutional constraints inherent in Indonesia’s budgeting system.

In addition, studies such as Wang and Su (2021) have explored how resource wealth (e.g., oil) impacts military financing. However, these studies often assume that higher oil production correlates with higher military investment, an assumption that may not hold in countries like Indonesia, where oil revenues may be diverted toward non-defense subsidies or populist programs.

Therefore, this paper contributes to the literature by applying an ARDL model tailored to Indonesia’s macroeconomic and strategic environment, while explicitly discussing the implications of institutional fragmentation in defense spending. It also highlights the need for further research that combines econometric rigor with institutional realism, particularly in the context of emerging economies.

3 Data and Method

3.1 Research Design

This study employs a quantitative research design utilizing time-series econometric analysis to examine the determinants of Indonesia’s defense expenditure. The Autoregressive Distributed Lag (ARDL) model is used to analyze both short-term and long-term relationships between economic and geopolitical variables and military spending. The ARDL approach is particularly suitable for this study as it can handle time-series data with mixed orders of integration (I(0) and I(1)), allowing for robust estimations of dynamic relationships (Pesaran and Smith 2016). Additionally, ARDL facilitates the identification of co-integration, which helps determine whether a long-run equilibrium relationship exists between defense expenditure and its key determinants. Given the complexities of military budgeting, where economic cycles and geopolitical shifts influence allocation decisions over time, this method provides a strong analytical foundation.

The research follows a structured econometric approach, starting with stationarity testing using Augmented Dickey-Fuller (ADF) and Phillips-Perron (PP) tests to determine whether the variables are integrated at level I(0) or first difference I(1). The ARDL Bounds Test for Co-integration (Pesaran et al. 2001) is then applied to assess the presence of a long-run relationship between Indonesia’s defense budget and explanatory variables. If co-integration is confirmed, an Error Correction Model (ECM) is estimated to examine the speed at which deviations from equilibrium adjust over time. Furthermore, diagnostic tests such as Breusch-Godfrey Serial Correlation LM Test, Breusch-Pagan Heteroscedasticity Test, and Ramsey RESET Test are performed to ensure model validity, while CUSUM and CUSUMSQ tests are used to assess parameter stability over time.

3.2 Data Sources

This study relies on secondary data from authoritative national and international sources to ensure accuracy, reliability, and consistency. The dataset spans multiple decades to capture historical trends and structural shifts in Indonesia’s defense expenditure. Altough the study recognizes that defense spending under the SISHANKAMRATA doctrine involves multiple ministries, a consolidated dataset covering multi-ministerial defense-related expenditures over the full time series (1984–2022) is not publicly available. As such, the empirical model relies on official MILEX data from SIPRI/World Bank as a proxy for Indonesia’s defense budget and from the Ministry of Finance of Indonesia. This dataset provides the most consistent and internationally comparable series, allowing for econometric modeling. However, this limitation is acknowledged, and we recommend future studies to construct a SISHANKAMRATA-based defense expenditure index using cross-ministerial data.

Variable C_MILPER, which represents military expenditure as a percentage of GDP, is obtained through the World Bank’s World Development Indicators (WDI). The WDI series is derived from SIPRI data but has undergone standardization for international comparability. Macroeconomic indicators, including GDP growth rate, inflation, foreign debt, and exchange rates, are collected from the World Bank, Indonesia’s Central Statistics Agency (BPS–Statistics Indonesia), and Bank Indonesia (BI).

Given the role of external shocks and fiscal constraints in determining defense spending, these indicators provide insight into how economic conditions influence budgetary allocations. Furthermore, geopolitical variables, such as regional security tensions and conflict intensity, are derived from global risk assessment reports, ASEAN defense publications, and the Global Conflict Tracker (Council on Foreign Relations, CFR). Data on defense expenditures of neighboring countries, particularly Singapore, Malaysia, Brunei, and Australia, are obtained from SIPRI and ASEAN Defense Ministers’ Meeting (ADMM) reports to analyze regional military spending trends.

Although this study extensively discusses the SISHANKAMRATA framework as a central element of Indonesia’s defense doctrine, empirical modeling of this system presents substantial limitations. The lack of a comprehensive and longitudinal dataset that captures defense-related expenditures across non-defense ministries prevents the direct inclusion of a SISHANKAMRATA-specific variable in the ARDL framework. As such, the model relies on conventional defense expenditure data as a proxy, while the institutional logic of SISHANKAMRATA is reflected in the interpretation of results and policy recommendations.

3.3 Variables and Measurement

The analysis utilized time-series data spanning from 1984 to 2022, covering nearly four decades of Indonesia’s defense budgeting dynamics. While C_MILPER and USMIL are expressed as a percentage of GDP, NEIGH and REG are reported in constant USD terms due to the absence of standardized GDP-normalized defense data across neighboring countries. We acknowledge this inconsistency as a limitation, and encourage future studies to explore consistent unit standardization for improved model comparability. Dataset used in this research allowed for a comprehensive examination of both short-term and long-term relationships between defense expenditure and its economic and geopolitical determinants the variables included in the model are as shown in Table 1.

Summary of variables and data sources for military expenditure analysis.

| Dependent variable | Definition | Unit of measurement | Data sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| C_Milper | Military expenditure as a percentage of GDP | Percentage (Milex/GDP) | World Bank (based on SIPRI estimates) |

|

|

|||

| Indepen-dent variables | Definition | Unit of measurement | Data sources |

|

|

|||

| DEBT | International debt as a percentage of GDP | Percentage (Debt/GDP) | World Bank |

| EXC | Exchange rate (IDR/USD) | Rupiah (IDR) | World Bank |

| FDI | Foreign direct investment as a percentage of GDP | Percentage (FDI/GDP) | World Bank |

| INF | Inflation rate (%) | Percentage (%) | BPS–statistics Indonesia |

| TO | Trade openness (exports + imports/GDP) | Ratio | World Bank |

| NEIGH | Military expenditure of neighboring countries (Malaysia, Singapore, Australia) | Percentage of GDP | World Bank |

| REG | Regional average military expenditure (ASEAN) | Percentage of GDP | World Bank |

| USMIL | US military expenditure as a percentage of US GDP | Percentage of GDP | World Bank |

| OIL | Crude oil production in Indonesia | Barrels per day | World Bank |

| POP | Population | Million people | World Bank |

The variables used in this study were selected based on prior empirical research. The inclusion of debt-to-GDP ratio (Azam and Feng 2017), exchange (Khan and Imran 2023), and foreign direct invesment (Pacific et al. 2017) follows the framework established in previous studies on military expenditure determinants. The relationship between inflation and defense spending has also been explored by Aiyedogbon et al. (2012) Khan and Imran (2023), reinforcing its inclusion in this model. Meanwhile, regional and global defense expenditure influences have been documented (Christie 2019; Yalta and Yalta 2022; Yesilyurt and Elhorst 2017) supporting the relevance of NEIGH, REG, and USMIL as explanatory variables in this study.

Beyond global relevance, each variable has specific contextual rationale within the Indonesian defense and fiscal environment. Inflation is particularly important because Indonesia’s annual defense budget is often allocated in nominal terms, making it vulnerable to real-term erosion during inflationary periods. Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) is included to examine how external economic engagement may shift fiscal priorities away from defense and toward infrastructure or social spending. The inclusion of oil production reflects Indonesia’s fiscal reliance on commodity revenues. However, instead of acting as a multiplier for military spending, higher oil output in Indonesia may be absorbed into subsidized programs or non-defense sectors, consistent with resource-curse dynamics seen in other developing economies (Wang and Su 2021).

3.4 Model Specification

The model includes lagged values of both the dependent and independent variables to capture both short-term dynamics and long-term equilibrium relationships. The optimal model specification selected based on the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) is ARDL(3,2,2,2,1,2,2,2,2,2,2), where the dependent variable (C_MILPER) includes three lags, and each independent variable has one or two lags based on its significance and diagnostic performance. This lag structure allows the model to effectively capture short-term fluctuations and long-run adjustments in the relationship between military expenditure and its determinants. The general form of the estimated ARDL model can be expressed as follows:

Where:

| C_MILPER_t | :Military expenditure % GDP (dependent variable) |

| DEBT, ECG, EXC, FDI, INF, NEIGH, OIL, REG, TO, USMIL | :Independent variables |

| α | :Constant term |

| ε_t | :Error term (residual) |

| β_i and γ_j | :Coefficients of respective variables |

3.5 Estimation Procedure

The Autoregressive Distributed Lag (ARDL) bounds testing approach, as proposed by Pesaran et al. (2001), is employed to assess the presence of long-run relationships among the variables, ensuring the robustness of the model in handling mixed orders of integration (I(0) and I(1), but not I(2)). The estimation procedure begins with stationarity testing using the Augmented Dickey-Fuller (ADF) and Phillips-Perron (PP) tests, which confirm that none of the variables are integrated at order two (I(2)), a crucial requirement for ARDL estimation. Following this, the bounds test for cointegration is conducted to examine whether a long-term equilibrium relationship exists between Indonesia’s defense expenditure and its economic and geopolitical determinants, where the F-statistic exceeding the upper bound confirms the presence of cointegration. Once cointegration is established, the optimal lag length is selected based on the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) to ensure efficient model specification and capture the short-term and long-term dynamics effectively. Subsequently, diagnostic and robustness checks are performed to validate the model’s reliability, including the Breusch-Godfrey LM test for serial correlation, the Breusch-Pagan-Godfrey test for heteroscedasticity, and CUSUM and CUSUMSQ tests for structural stability, ensuring the consistency and robustness of the estimation results. All econometric analyses are conducted using EViews 12, guaranteeing computational accuracy and replicability, thereby reinforcing the validity of the findings and their policy implications regarding Indonesia’s defense expenditure.

4 Results

To provide an initial understanding of the data structure, Table 2 result of all variables used in the analysis. The dataset used in this study spans the period 1984–2022, covering nearly four decades of Indonesia’s defense spending and its relationship with key macroeconomic and geopolitical variables. The data are sourced from authoritative institutions, including the World Bank, Indonesia’s Ministry of Finance, and BPS – Statistics Indonesia, ensuring high credibility and consistency. The selection of variables is based on theoretical and empirical justifications from previous literature, focusing on factors such as debt, exchange rate, FDI, inflation, trade openness, neighboring military expenditure, regional military expenditure, US military expenditure, oil, and population, all of which are expected to influence Indonesia’s defense budget allocation.

ARDL Lagged variable estimates (Levels).

| Variable | Coefficient (prob.) |

|---|---|

| C | 10.8723 (0.0729)* |

| @TREND | −0.3494 (0.0680)* |

| C_MILPER(-1) | 2.0207 (0.0957)* |

| DEBT(-1) | −0.0494 (0.0748)* |

| ECG(-1) | −0.3027 (0.0747)* |

| EXC(-1) | 0.0006 (0.0832)* |

| FDI(-1) | −0.1174 (0.0707)* |

| INF(-1) | −0.2669 (0.0612)* |

| NEIGH_AVE(-1) | −6.0060 (0.0673)* |

| OIL(-1) | 0.0020 (0.1733) |

| REG_AVE(-1) | 0.9559 (0.0734)* |

| TO(-1) | 0.1782 (0.0648)* |

| USMIL(-1) | −0.1474 (0.2435) |

| D(C_MILPER(-1)) | −0.1020 (0.4476) |

| D(C_MILPER(-2)) | 2.9493 (0.0685)* |

| D(DEBT) | 0.0284 (0.0719)* |

| D(DEBT(-1)) | 0.1001 (0.0605)* |

| D(ECG) | −0.0270 (0.2592) |

| D(ECG(-1)) | 0.1507 (0.0670)* |

| D(EXC) | −0.0001 (0.1841) |

| D(EXC(-1)) | −0.0009 (0.0685)* |

| D(FDI) | −0.0651 (0.0733)* |

| D(FDI(-1)) | 0.0273 (0.1037) |

| D(INF) | −0.0709 (0.0511)** |

| D(INF(-1)) | 0.0360 (0.1417) |

| D(NEIGH_AVE) | −2.8523 (0.0720)* |

| D(NEIGH_AVE(-1)) | 0.2439 (0.1737) |

| D(OIL) | −0.0008 (0.1650) |

| D(OIL(-1)) | −0.0016 (0.1009) |

| D(REG_AVE) | 0.9078 (0.0807)* |

| D(REG_AVE(-1)) | −0.2665 (0.1528) |

| D(TO) | −0.0347 (0.1001) |

| D(TO(-1)) | −0.1253 (0.0664)* |

| D(USMIL) | −0.6169 (0.0612)* |

| D(USMIL(-1)) | −0.8550 (0.0805)* |

-

*, ** and *** = significant at 10 %, 5 % and 1%.

The elimination process in this study follows a systematic approach to ensure that only relevant and statistically valid variables are included in the ARDL estimation model. Initially, 23 research variables were identified, encompassing macroeconomic and geopolitical factors. However, due to data unavailability or insufficient observations, some variables were excluded, reducing the dataset to 10 variables. Next, a stationarity test (Unit Root Test) was conducted using the Augmented Dickey-Fuller (ADF) method to determine whether the remaining variables met the integration requirements for ARDL modeling. The results indicate that the dependent variable C_MILPER is stationary at level (I(0)) with a probability of 0.0321, while most independent variables, such as Debt, EXC, NEIGH, OIL, REG, and USMIL, are non-stationary at level but become stationary after first differencing (I(1)). Additionally, ECG and INF are found to be stationary at level (I(0)), while POP fails to achieve stationarity at both levels (p = 0.3204 at level, p = 0.9937 at first difference), making it unsuitable for inclusion in the ARDL model. Based on these findings, POP is excluded to ensure that all variables satisfy the stationarity requirements necessary for ARDL modelling.

To ensure the validity and robustness of the ARDL model, classical assumption tests were performed. The F-Bounds Test for cointegration confirms the presence of a long-term relationship among the variables, with an F-statistic value of 35.21413, which significantly exceeds the upper bound at all significance levels, justifying the application of the ARDL approach. The Jarque-Bera normality test confirms that the residuals are normally distributed (p-value = 0.119832), ensuring the validity of statistical inference. The Breusch-Godfrey serial correlation test reveals no autocorrelation in the residuals (p-value = 0.9227), ensuring that the model does not suffer from biased regression estimates. Furthermore, the Breusch-Pagan-Godfrey heteroscedasticity test confirms that residual variance remains constant (p-value = 0.9991), indicating the absence of heteroscedasticity, which ensures efficiency in parameter estimation. Table 2 presents the short-run estimation results of the ARDL model.

The short-run results in Table 2 show that several macroeconomic and geopolitical variables significantly influence Indonesia’s defense expenditure. Inflation (D(INF)) exhibits a strong negative effect, confirming that price increases erode the real value of military allocations in a system where defense budgets are determined in nominal terms. This finding is consistent with the literature on inflationary constraints in emerging economies’ defense spending.

Exchange rate (D(EXC(-1))) also shows a negative and significant coefficient, indicating that rupiah depreciation raises the cost of imported defense equipment and technology, thereby suppressing effective defense spending in the short run. Similarly, foreign direct investment (D(FDI)) exerts a negative influence, which may suggest that during periods of higher FDI inflows, the government prioritizes policies that maintain macroeconomic attractiveness rather than expanding military expenditure.

On the other hand, several variables demonstrate positive short-run effects. Debt (D(DEBT) and D(DEBT(-1))) is positively associated with defense expenditure, implying that borrowing may temporarily ease fiscal constraints and allow higher allocations to defense. Regional average military spending (D(REG_AVE)) and trade openness (D(TO(-1))) also show significant positive effects, suggesting that Indonesia reacts promptly to regional defense competition and international trade dynamics by adjusting its military budget.

Furthermore, U.S. military expenditure (D(USMIL) and D(USMIL(-1))) displays a negative short-run effect, indicating that a stronger U.S. presence in the Indo-Pacific may temporarily reduce Indonesia’s perceived need to increase its defense spending. This aligns with the concept of a security substitution effect in the short run. To capture Indonesia’s structural defense spending behavior, it is essential to examine the long-run estimation results presented in Table 3.

ARDL Long-run estimation results.

| Variable | Coefficient (prob.) |

|---|---|

| DEBT | 0.0244 (0.0760)* |

| ECG | 0.1498 (0.0827)* |

| EXC | −0.0003 (0.0506)** |

| FDI | 0.0581 (0.0444)** |

| INF | 0.1321 (0.0486)** |

| NEIGH_AVE | 2.9723 (0.0387)** |

| OIL | −0.0010 (0.1203) |

| REG_AVE | −0.4730 (0.0833)* |

| TO | −0.0882 (0.0404)** |

| USMIL | 0.0729 (0.2924) |

-

*, ** and *** = significant at 10 %, 5 % and 1%.

The long-run estimation results in Table 3 indicate that several macroeconomic and regional variables exert a statistically significant influence on Indonesia’s defense expenditure. Debt (DEBT), economic growth (ECG), exchange rate (EXC), foreign direct investment (FDI), inflation (INF), neighboring countries’ military expenditure (NEIGH_AVE), regional average military expenditure (REG_AVE), and trade openness (TO) are all significant determinants in the long run, though the direction of their effects varies.

Specifically, FDI, inflation, and economic growth have positive long-run effects, suggesting that improvements in macroeconomic fundamentals tend to expand fiscal space and allow greater allocation to defense. Similarly, neighboring countries’ defense spending (NEIGH_AVE) shows a strong positive impact, reinforcing the hypothesis that Indonesia responds to regional military dynamics. In contrast, trade openness (TO) and regional average expenditure (REG_AVE) exert negative effects, which may reflect fiscal trade-offs or regional burden-sharing dynamics. Exchange rate (EXC) also shows a negative relationship, consistent with the idea that depreciation increases procurement costs, thereby constraining defense spending.

Meanwhile, U.S. military expenditure (USMIL) does not appear significant in the long run, diverging from earlier short-run results. This finding suggests that Indonesia’s long-term defense allocation is shaped more by domestic macroeconomic conditions and regional security competition than by U.S. defense posture in the Indo-Pacific.

To ensure the validity and reliability of the ARDL estimations, robustness checks were performed. Table 4 presents the diagnostic test results, including normality of residuals, autocorrelation tests, and heteroscedasticity tests. The Error Correction Term (ECT) coefficient is −0.2285 and statistically significant at the 5 % level (p < 0.05), indicating that approximately 22.85 % of any deviation from the long-run equilibrium is corrected annually.

Robustness and diagnostic tests for ARDL model.

| Test name | Test statistic | p-Value | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|

| F-bounds test (cointegration) | 35.21413 | – | Cointegration exists |

| Jarque-bera normality test | 4.243329 | 0.1198 | Residuals normally distributed |

| Breusch-Godfrey serial correlation test | 0.009419 | 0.9227 | No autocorrelation |

| Breusch-Pagan-Godfrey heteroscedasticity test | 23.49823 | 0.9991 | No heteroscedasticity |

| Adjusted R-Squared | 0.997949 | – | Model explains 99.79 % of variance |

| Durbin-Watson statistic | 1.9747 | – | No autocorrelation |

| Akaike information criterion (AIC) | −6.62875 | – | Optimal model selection |

| Error correction term (ECT(-1)) | −0.2285 | <0.05 | Speed of adjustment: 22.85 % |

The findings of this study demonstrate that variables such as exchange rate (EXC) and inflation (INF) influence military expenditure in the short run, whereas external factors like US military expenditure (USMIL) have a sustained long-term impact. The presence of a significant and negative Error Correction Term (ECT) confirms the existence of a long-run equilibrium relationship. Additionally, robustness tests confirm that the model satisfies classical assumptions, ensuring the reliability of the results. These findings emphasize the importance of considering both short-term economic fluctuations and long-term strategic factors when formulating defense budget policies.

5 Discussion

5.1 Interpretation of Findings

The ARDL model results reveal several key short- and long-run drivers of Indonesia’s defense expenditure. In the short run, Indonesia’s defense budget is highly sensitive to macroeconomic fluctuations. Inflation (INF) shows a strong negative effect, indicating that rising prices erode the real value of nominally allocated defense budgets. This is consistent with Aiyedogbon et al. (2012), who found that inflationary pressures constrained military spending in Nigeria. Similarly, exchange rate volatility (EXC) has a negative impact, reflecting how rupiah depreciation raises the cost of imported military equipment and reduces effective defense capacity, in line with Khan and Imran (2023). Foreign direct investment (FDI) also exerts a negative influence, suggesting that when capital inflows rise, the government may prioritize policies that maintain macroeconomic stability and investor confidence rather than expanding military outlays, which resonates with the findings of Pacific et al. (2017).

On the other hand, debt (DEBT) demonstrates a positive short-run relationship with defense spending, implying that borrowing provides temporary fiscal space to support defense allocations, consistent with the debt–defense link highlighted by Azam and Feng (2017). Regional military expenditure (REG) and trade openness (TO) also show positive short-run effects, highlighting Indonesia’s responsiveness to regional competition and international trade dynamics. Meanwhile, U.S. military expenditure (USMIL) exerts a negative short-run influence, suggesting a temporary deterrent substitution effect whereby Indonesia reduces its own military spending in the presence of greater U.S. security engagement in the Indo-Pacific. This echoes the “security umbrella” argument observed in other regions (Christie 2019).

Overall, these short-run findings emphasize that Indonesia’s defense spending is vulnerable to macroeconomic shocks and external security signals, reflecting fiscal fragility in the face of inflation, exchange rate pressures, and geopolitical uncertainty. However, these short-term fluctuations do not necessarily determine long-term structural trends. To understand Indonesia’s sustained defense posture, it is necessary to examine the long-run dynamics.

In the long run, the results show that macroeconomic fundamentals and regional competition are more decisive drivers of defense expenditure. Debt (DEBT), economic growth (ECG), foreign direct investment (FDI), inflation (INF), and neighboring countries’ military expenditure (NEIGH_AVE) all exert significant positive effects, suggesting that stronger economic performance and regional security pressures create fiscal and strategic incentives for Indonesia to expand its defense budget. The strong positive influence of NEIGH_AVE underscores the importance of regional arms race dynamics, with Indonesia adjusting its defense posture in response to neighboring countries’ military spending. This aligns with the findings of Yesilyurt and Elhorst (2017), who documented spatial interdependence in military budgets across countries sharing contested borders.

Conversely, exchange rate (EXC), trade openness (TO), and regional average defense spending (REG_AVE) show significant negative long-run effects. Exchange rate depreciation appears to constrain long-term defense investment by raising procurement costs, while greater trade openness may reflect a structural prioritization of economic integration over defense expansion. The negative effect of REG_AVE suggests a possible burden-sharing mechanism, where Indonesia moderates its defense spending when regional military expenditure as a whole rises, relying on collective security rather than unilateral escalation.

Interestingly, U.S. military expenditure (USMIL) is not significant in the long run, diverging from its short-run influence. This indicates that while U.S. presence may temporarily affect Indonesia’s defense calculus, it does not structurally determine Indonesia’s long-term defense allocation. Instead, domestic economic fundamentals and direct regional competition remain the most important drivers of sustained defense spending.

Taken together, these results highlight a clear distinction: Indonesia’s short-run defense spending is shaped by fiscal shocks and temporary geopolitical signals, whereas its long-run trajectory is governed by macroeconomic capacity and regional security competition. This confirms earlier arguments by Deger and Sen (1995) on the dual economic–security role of military expenditure and extends them within Indonesia’s unique institutional and geopolitical context.

5.2 Robustness and Model Validation

The model’s reliability is supported by diagnostic tests conducted in the Results section, which confirmed the absence of serial correlation, heteroscedasticity, and specification error. This strengthens confidence in the stability and efficiency of the estimated coefficients, making the findings robust for policy interpretation. Rather than repeating the full test results, this section focuses on the implications of model consistency in validating the defense-economic relationships observed.

5.3 Comparasion with Previous Studies

The findings of this study are both consistent with and divergent from previous literature, offering new insights into Indonesia’s military spending behavior. For instance, the negative relationship between inflation and defense expenditure aligns with the results of Aiyedogbon et al. (2012), who identified similar constraints in Nigeria, where inflation eroded the real value of defense allocations. Likewise, Khan and Imran (2023) observed inflation’s dampening effect on defense budgets in economies with nominally fixed spending frameworks, reinforcing the structural challenges faced by fiscal planners in emerging economies.

Regarding foreign direct investment (FDI), our study finds a negative short-run relationship with defense spending. While this linkage has received limited attention, Pacific et al. (2017) observed that high defense expenditure may crowd out capital inflows in small economies due to perceptions of political risk or economic instability. Our findings extend this argument by showing that in Indonesia, rising FDI may coincide with a shift in fiscal priorities away from military outlays toward development-oriented spending. However, in the long run, FDI exhibits a positive relationship, suggesting that greater economic integration and capital inflows can eventually provide fiscal space for expanding defense budgets.

Another key finding concerns the contrast between U.S. military expenditure (USMIL) and regional military spending (REG/NEIGH). In the short run, the negative coefficient for USMIL suggests a deterrent substitution effect Indonesia may temporarily scale back its defense efforts when U.S. presence in the Indo-Pacific is perceived as a stabilizing external buffer. This contrasts with Christie (2019), who found that European countries tended to increase defense spending in line with U.S. military expansion due to alliance commitments under NATO. In the long run, however, USMIL is not significant, indicating that Indonesia’s sustained defense posture is not structurally determined by U.S. military activity.

By contrast, both regional average spending (REG_AVE) and neighboring countries’ expenditure (NEIGH_AVE) play important roles. The strong positive effect of NEIGH_AVE confirms the regional arms race hypothesis: as neighboring countries such as Singapore, Malaysia, and Australia expand their military budgets, Indonesia adjusts its own allocations upward to avoid relative strategic decline. This is consistent with Yesilyurt and Elhorst (2017), who documented spatial interdependence in military budgets across countries with overlapping security concerns. Interestingly, REG_AVE exerts a negative effect in the long run, suggesting a possible burden-sharing mechanism, where Indonesia moderates its defense spending when aggregate regional expenditure rises, relying on collective regional security rather than unilateral expansion.

Unlike earlier results, this study does not find a significant long-run effect of oil production (OIL). This diverges from findings in Gulf states, where oil revenues often drive military expansion (Yalta and Yalta 2022). In Indonesia’s case, the insignificance of oil may reflect its reduced fiscal role due to declining reserves and the diversion of resource revenues toward non-defense priorities such as subsidies and infrastructure, echoing aspects of the “resource curse” argument (Wang and Su 2021).

5.4 Theoretical Implications

The results of this study provide several theoretical implications for understanding the dynamics of defense expenditure in emerging economies such as Indonesia. The guns-versus-butter dilemma remains evident. The negative short-run effects of inflation, exchange rate depreciation, and FDI indicate that macroeconomic and fiscal constraints continue to limit the government’s ability to prioritize defense spending over socioeconomic needs. These findings echo the arguments of Deger and Sen (1995), who emphasized the trade-offs that developing countries face between maintaining security and funding development priorities. In Indonesia’s case, fiscal resources are often diverted toward stabilizing the economy and promoting growth, thereby constraining defense allocations in the short run.

The distinction between short-run and long-run drivers underscores the temporal dimension of defense budgeting. In the short run, Indonesia’s defense expenditure responds to immediate macroeconomic shocks and temporary geopolitical signals, such as inflationary pressures, exchange rate volatility, and the presence of U.S. military power in the Indo-Pacific. This aligns with the notion of deterrent substitution, whereby external security umbrellas reduce domestic defense burdens in the short term (Christie 2019). However, the insignificance of U.S. military expenditure (USMIL) in the long run suggests that Indonesia does not structurally anchor its defense strategy to U.S. presence, but instead relies on domestic fundamentals and regional dynamics.

Strong positive impact of neighboring countries’ defense spending (NEIGH_AVE) in the long run reinforces the regional arms race hypothesis. Similar to the findings of Yesilyurt and Elhorst (2017), Indonesia adjusts its defense posture in response to increases in military expenditure by its immediate ASEAN peers, highlighting the competitive and interdependent nature of security policies in Southeast Asia. At the same time, the negative long-run effect of regional average defense expenditure (REG_AVE) points to a potential burden-sharing mechanism, where Indonesia reduces unilateral defense commitments when regional collective spending increases, reflecting a pragmatic approach to balancing national and regional security needs.

Finally, the insignificance of oil production (OIL) in the long run diverges from the experience of resource-dependent states in the Gulf, where oil revenues often underpin military expansion (Yalta and Yalta 2022). This suggests that Indonesia’s fiscal trajectory has moved away from resource dependence toward broader economic drivers, with oil revenues playing a diminished role in defense budgeting. This partially resonates with the resource curse hypothesis (Wang and Su 2021), but in Indonesia’s case it reflects declining reserves and reallocation of resource revenues toward subsidies and infrastructure rather than defense.

5.5 Policy Implication

The findings of this study underline the importance of aligning Indonesia’s defense budgeting with both macroeconomic stability and regional security dynamics. The sensitivity of military expenditure to short-run shocks such as inflation and exchange rate volatility suggests the need for mechanisms that safeguard the real value of defense allocations, for instance through inflation-adjusted budgeting and strategies to mitigate currency risks in procurement. At the same time, the temporary positive role of debt indicates that borrowing can ease fiscal pressures, but reliance on this instrument must be complemented with more sustainable financing options, such as defense bonds or a sovereign wealth fund dedicated to security spending.

The results also highlight the complex relationship between defense spending and foreign direct investment. While FDI appears to constrain military allocations in the short run, it contributes positively in the long run by broadening fiscal capacity. This points to the importance of maintaining credible and transparent defense financing practices to ensure that military priorities do not undermine Indonesia’s attractiveness to investors. More broadly, the evidence that defense expenditure rises in response to neighboring countries’ military spending confirms Indonesia’s exposure to regional arms race dynamics. Yet, the negative long-run effect of regional average defense spending suggests that Jakarta also benefits from collective security arrangements, emphasizing the need to deepen cooperation within ASEAN frameworks such as the ADMM.

Another important implication is that U.S. military presence, though relevant in the short term, does not shape Indonesia’s long-run defense trajectory. This indicates that while global powers may temporarily influence regional balances, Indonesia’s sustainable defense posture depends primarily on domestic economic strength and regional cooperation. Finally, the lack of a significant long-run effect of oil revenues suggests that defense financing can no longer rely on resource rents. A broader fiscal base, economic diversification, and innovative instruments such as public–private partnerships are therefore critical to ensuring long-term stability in defense funding.

6 Conclusions

This study offers a macroeconomic ARDL analysis of Indonesia’s defense expenditure using official data. While the SISHANKAMRATA system adds institutional complexity, it is not modeled empirically in this paper. The findings indicate that macroeconomic variables such as inflation, exchange rate fluctuations, and foreign direct investment significantly influence short-term defense budgeting, while geopolitical factors such as regional military spending and US military expenditure shape long-term allocation decisions. The presence of a significant and negative Error Correction Term (ECT) confirms the existence of a long-run equilibrium relationship, demonstrating that deviations in military spending adjust toward equilibrium over time.

Given Indonesia’s fragmented defense financing system under the SISHANKAMRATA doctrine, policy formulation should recognize the hidden fiscal burden that arises when multiple ministries contribute to defense functions without consolidated oversight. Policymakers are encouraged to develop an integrated budgeting framework that transparently accounts for defense-related expenditures across all relevant institutions.

Furthermore, the ARDL model used in this study, while effective in capturing macroeconomic and geopolitical influences, may not fully reflect the institutional complexity of Indonesia’s defense posture. As such, future modeling efforts could benefit from structural or systems-based approaches, including hybrid models or qualitative-comparative analysis, to better incorporate institutional fragmentation and inter-agency dynamics.

To enhance the strategic alignment of defense budgeting, Indonesia could explore innovative financing mechanisms such as a Defense Sovereign Wealth Fund (D-SWF) or targeted public-private partnerships (PPP) for infrastructure and logistics. These mechanisms would allow the state to maintain fiscal discipline while ensuring sustained military readiness.

In this light, the study serves not only as an empirical exploration of defense spending but also as a methodological bridge between traditional macroeconomic modeling and the realities of fragmented institutional environments. The framework developed here lays the groundwork for more integrated defense economic studies in the future, particularly for countries adopting non-centralized defense doctrines.

7 Future Research Direction

Despite the robustness of the findings, this study has several limitations. One major constraint is the availability of data, as some geopolitical variables, such as military alliances and conflict intensity, were excluded due to data unavailability. Future studies could integrate geopolitical risk indices to refine military expenditure modeling. Additionally, the model does not explicitly account for military technological advancements or defense procurement cycles, both of which are crucial in long-term defense budgeting. Expanding future research to include the role of defense innovation and arms trade dependencies could provide further insights into military financing.

An important future direction is the reconstruction of a defense spending index based on SISHANKAMRATA’s structure. This could involve aggregating actual budget data from multiple defense-relevant ministries (e.g., Ministry of Defense, Ministry of Transportation, Ministry of State-Owned Enterprises, etc.) to generate a more realistic measure of Indonesia’s total defense effort. Such an index would improve empirical alignment with the conceptual framework and offer a stronger basis for model estimation.

Another limitation is the scope of this study, which focuses solely on Indonesia, limiting the generalizability of the results. Future research should conduct panel data analysis across ASEAN countries to identify broader regional trends in military expenditure. A comparative study of defense budgeting strategies across developing nations would further enhance understanding of military expenditure dynamics in resource-constrained economies.

Acknowledgement

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to all those who have supported and contributed to the completion of this research specially our colleagues at the Indonesia Defense University and Bogor Agriculture Institute.

References

Aiyedogbon, J. O., B. O. Ohwofasa, and S. E. Ibeh. 2012. “Does Military Expenditure Spur Inflation? Autoregressive Distributed Lag (ARDL) & Causality Analysis for Nigeria.” European Journal of Business and Management 4 (20).Search in Google Scholar

Azam, M., and Y. Feng. 2017. “Does Military Expenditure Increase External Debt? Evidence from Asia.” Defence and Peace Economics 28 (5): 550–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/10242694.2015.1072371.Search in Google Scholar

Christie, E. H. 2019. “The Demand for Military Expenditure in Europe: the Role of Fiscal Space in the Context of a Resurgent Russia.” Defence and Peace Economics 30 (1): 72–84. https://doi.org/10.1080/10242694.2017.1373542.Search in Google Scholar

Deger, S., and S. Sen. 1995. “Military Expenditure and Developing Countries.” In Handbook of Defense Economics, Vol. 1, 275–307. Amsterdam: Elsevier.10.1016/S1574-0013(05)80013-4Search in Google Scholar

Dunne, J. P., and N. Tian. 2017 Submitted for publication. “Military Expenditure, Economic Growth and Heterogeneity.” Defense Spending, Natural Resources, and Conflict 25–42.Search in Google Scholar

Fordham, B. O., and T. C. Walker. 2005. “Kantian Liberalism, Regime Type, and Military Resource Allocation: Do Democracies Spend Less?” International Studies Quarterly 49 (1): 141–57. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0020-8833.2005.00338.x.Search in Google Scholar

Kennedy, D. 2017. The Development of Professional Military Education at the United States Air Force Academy. Kansas State University.Search in Google Scholar

Khan, U. H., and M. D. Imran. 2023. “Relationship Between Inflation and Other Macro Economics Factors: Comparative Study of Germany, Japan and New Zealand.” Journal of Economic Impact 5 (1): 76–87. https://doi.org/10.52223/jei5012309.Search in Google Scholar

Pacific, Y. K. T., L. J. Shan, and A. A. Ramadhan. 2017. “Military Expenditure, Export, FDI and Economic Performance in Cameroon.” Global Business Review 18 (3): 577–89. https://doi.org/10.1177/0972150917692065.Search in Google Scholar

Pesaran, M. H., Y. Shin, and R. J. Smith. 2001. “Bounds Testing Approaches to the Analysis of Level Relationships.” Journal of applied econometrics 16 (3): 289–326. https://doi.org/10.1002/jae.616.Search in Google Scholar

Pesaran, M. H., and R. P. Smith. 2016. “Counterfactual Analysis in Macroeconometrics: An Empirical Investigation into the Effects of Quantitative Easing.” Research in Economics 70 (2): 262–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rie.2016.01.004.Search in Google Scholar

Wang, K. H., and C. W. Su. 2021. “Does High Crude Oil Dependence Influence Chinese Military Expenditure decision-making?” Energy Strategy Reviews 35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esr.2021.100653.Search in Google Scholar

World Bank. 2025a. Military Expenditure (% of GDP) – Indonesia. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/MS.MIL.XPND.GD.ZS?locations=ID (accessed January 1, 2025).Search in Google Scholar

World Bank. 2025b. Military Expenditure (% of GDP) – all Countries (Descending Order). https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/MS.MIL.XPND.GD.ZS?name_desc=true (accessed January 5, 2025).Search in Google Scholar

World Bank. 2025c. Total Government Debt (% of GDP). https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/GC.DOD.TOTL.GD.ZS (accessed January 10, 2025).Search in Google Scholar

World Bank. 2025d. Official Exchange Rate (LCU per US$, Period Average) – Indonesia. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/PA.NUS.FCRF?locations=ID (accessed January 15, 2025).Search in Google Scholar

World Bank. 2025e. Foreign Direct Investment, Net Inflows (% of GDP). https://databank.worldbank.org/metadataglossary/world-development-indicators/series/BX.KLT.DINV.WD.GD.ZS (accessed January 20, 2025).Search in Google Scholar

World Bank. 2025f. Trade (% of GDP) – World. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NE.TRD.GNFS.ZS?locations=1W (accessed January 30, 2025).Search in Google Scholar

World Bank. 2025g. Military Expenditure (Current US$). https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/MS.MIL.XPND.CD (accessed February 1, 2025).Search in Google Scholar

World Bank. 2025h. Military Expenditure (% of GDP) – United States. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/MS.MIL.XPND.GD.ZS?locations=US (accessed February 3, 2025).Search in Google Scholar

World Bank. 2025i. Oil Production (Million Barrels per Day). https://prosperitydata360.worldbank.org/en/indicator/IMF+MCDREO+NGDPMO_MBD (accessed February 5, 2025).Search in Google Scholar

World Bank. 2025j. Total Population. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP.TOTL (accessed February 10, 2025).Search in Google Scholar

Yalta, A. T., and A. Y. Yalta. 2022. “The Determinants of Defense Spending in the Gulf Region.” Defence and Peace Economics 33 (8): 980–92. https://doi.org/10.1080/10242694.2021.1918857.Search in Google Scholar

Yesilyurt, M. E., and J. P. Elhorst. 2017. “Impacts of Neighboring Countries on Military Expenditures: a Dynamic Spatial Panel Approach.” Journal of Peace Research 54 (6): 777–90. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343317707569.Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.