Abstract

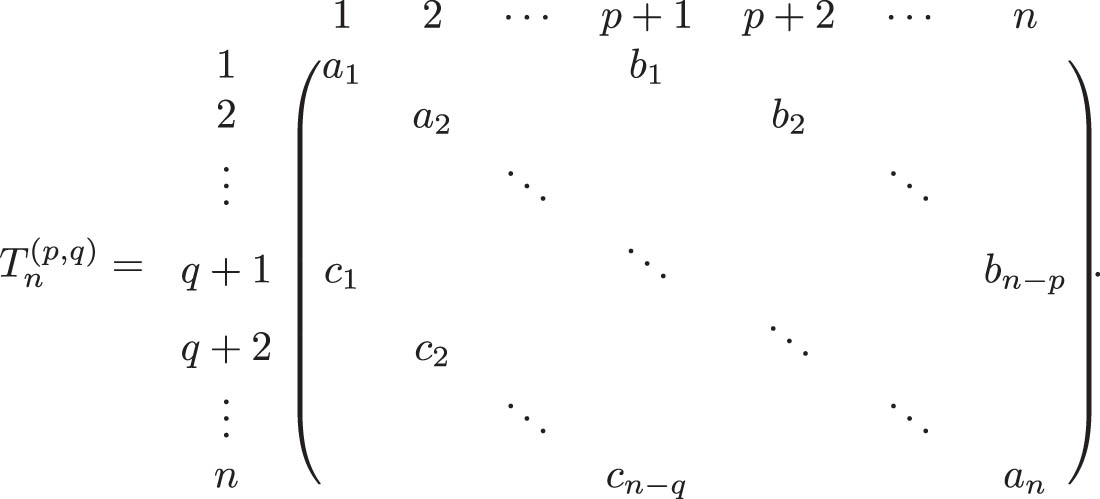

In this article, we study the block diagonalization of

1 Introduction

An

When

As an extension of

2 Notations

The greatest common divisor of two integers

3 Summary of the results

In Table 1, we summarize our results on block diagonal reduction of

Number of blocks in the block diagonal reduction of

| Condition on

|

Number of blocks | Nature of blocks |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Each block is

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

length of remaining paths depends on

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

We present an algorithm for the bidiagonal reduction of

4 Block diagonal reduction of

(

p

,

q

)

-tridiagonal matrices and their nature

Let

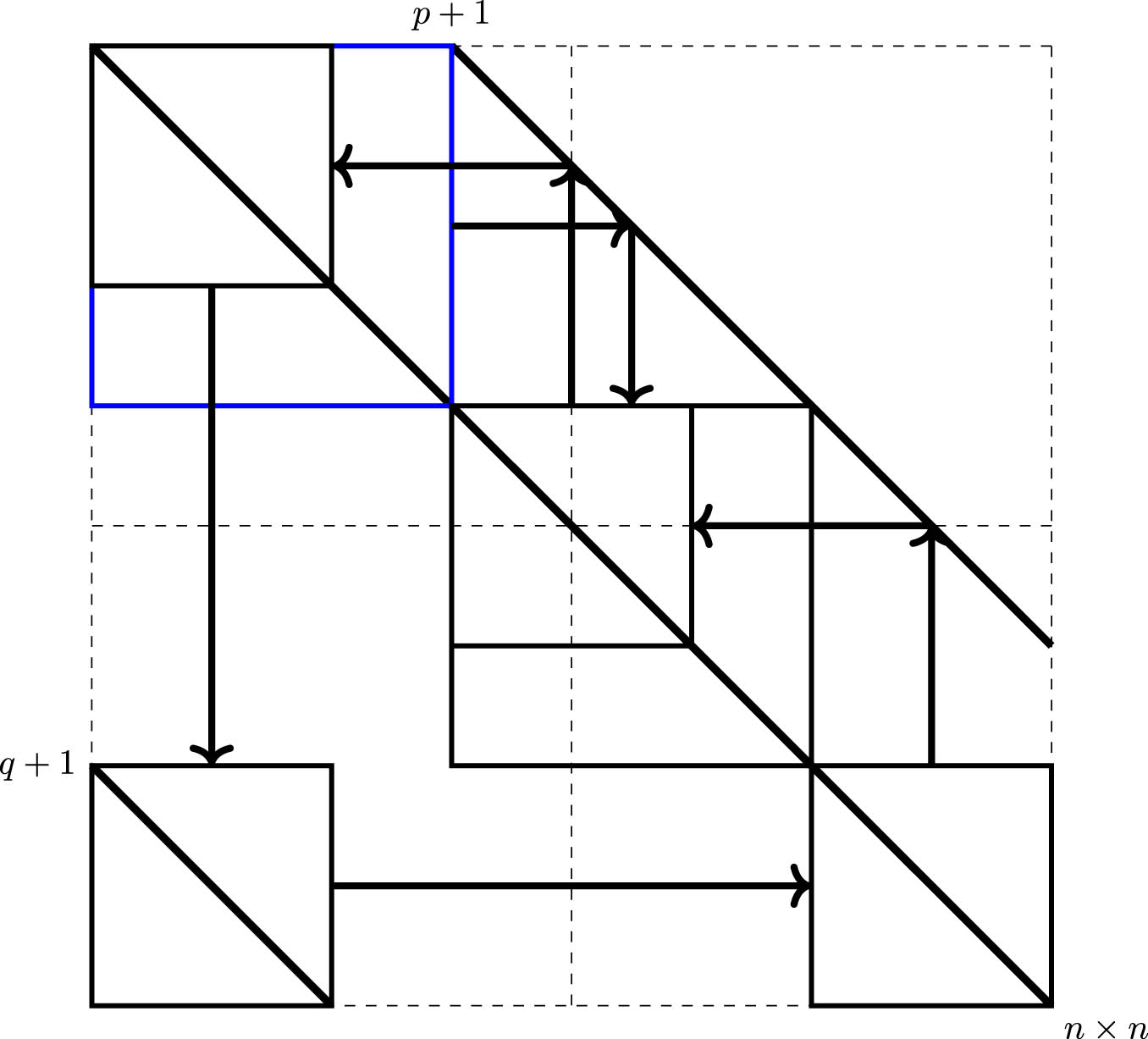

Starting with a vertex

Then, to obtain the connected component corresponding to vertex

where

Let

Then, we have the disjoint union

Let the number of equivalent classes be

Let

Let

Then, we have the following theorem.

Theorem 1

The matrix

Proof

Consider the directed graph corresponding to

Consider a situation when a connected component is a directed path. Define the “matrix order” to be the order of the vertices according to the adjacency matrix

The following Lemma 1 gives a situation when every connected component is a path.

Lemma 1

If

Proof

Since

Starting with an arbitrary vertex in a connected component, one can move right (in the direction of the arrow) or left (against the direction of the arrow). If we continue this traversal and the two ends meet, then we obtain a directed cycle. Otherwise, we obtain a directed path.

Let

This leads to a contradiction. On the other hand, if

Since we know

| Algorithm 1. Obtain connected components | |

|---|---|

| 1: | Input :

|

| 2: | Output: Connected components

|

| 3: |

while

|

| 4: |

|

| 5: |

|

| 6: |

|

| Algorithm 2. Lexicographic depth-first search (LDFS) | |

|---|---|

| 1: |

|

| 2: | Connected component

|

| 3: |

|

| 4: |

|

| 5: | push(

|

| 6: |

while Stack

|

| 7: |

|

| 8: |

|

| 9: |

|

| 10: |

|

| 11: |

|

| 12: | Sort vertices in

|

|

Algorithm 3. Neighbour

|

|

|---|---|

| 1: |

|

| 2: |

|

| 3: |

if

|

| 4: |

|

| 5: |

|

| 6: |

|

| 7: |

if

|

| 8: |

|

| 9: |

|

| 10: |

|

| 11: |

if

|

| 12: |

|

| 13: |

|

| 14: |

|

| 15: |

if

|

| 16: |

|

| 17: |

|

| 18: |

|

| 19: | Return

|

Theorem 2

When the indices

Proof

In the lexicographic Depth First Search, starting with an arbitrary vertex

Depth-first search starting at (0, 0) marks the nodes in the path along the arrow in the upper right quadrant ((0, 0) to

As a corollary of the above theorem, we have block bidiagonalization when

Corollary 1

When

Next we look at the number of diagonal blocks and their nature in the block diagonal reduction of

Remark

Unless otherwise stated, we assume

Theorem 3

If

Proof

Consider equivalence classes

Now,

From any arbitrary vertex, we can trace back to a vertex number

Let

Remark 1

The above theorem gives a simple procedure to reduce the

From Remark 1, each block diagonal matrix is

Example 1

Consider

Example 2

For the eigenvalue computation, we consider the block diagonal reduction of

For

Theorem 4

When

Proof

Start with the block

When

Theorem 5

If

Proof

The columns

Theorem 6

When

Proof

Consider the

When

Theorem 7

When

Proof

Let

If

Two cases when

Theorem 8

When

Proof

Let

When

Therefore, if

The matrix can be seen as the

Let

If

The structure of the connections when

Let

Theorem 9

For odd n, the number of blocks in the block diagonal reduction is given by

Proof

If we remove the vertex 1 in

5 Description of the algorithm for block diagonalization of

(

p

,

q

)

-tridiagonal matrix

The block diagonalization of a

This ordering is crucial: when a component forms a directed path, lexicographic traversal ensures that the corresponding submatrix becomes bidiagonal under a permutation. After processing all components, the matrix is permuted using the concatenated permutation matrices, yielding a block diagonal form. The overall time complexity of the algorithm is linear in the size of the matrix, since each vertex and edge is visited once. An open-source implementation in Octave is available at: https://github.com/HariprasadManjunath/Block-p-q.

6 Block diagonalization of

(

P

,

Q

)

-tridiagonal matrices

The extension from

Graph-based theoretical tools developed for

In general, when

and the

Let the columns of the permutation matrices

Let

Then, we have the following theorem.

Theorem 10

The matrix

Proof

The proof follows from the fact that the vertices corresponding to the indices in

Theorem 10 generalizes block diagonalization of the case of k-tridiagonal matrices. By keeping track of the equivalence classes, we can reduce the matrix into block diagonal form.

This reduces the problem size for eigenvalue and eigenvector algorithms. Thus, further speeding up the parallel computations.

6.1 Triangular reduction of

(

P

,

Q

)

-tridiagonal matrices

Note that, when we have

with diagonal matrices

When we have

Then, we have the following theorem.

Theorem 11

If

Proof

When

Since

Then,

Lemma 2

If

Proof

Starting with an arbitrary vertex

By moving left (in the opposite direction of the arrow), we obtain the sequence,

Now, if there is a directed cycle, then any two terms of the above two sequences must be equal. The term

then using

Using

Using (8) and (9) in (7), we obtain

which is a contradiction since

On the other hand, if we have

Equation (10), is a contradiction since we have

Lemma 3

When

Proof

Let

Let this sequence end at a vertex

Let this sequence end at vertex

From Lemma 2, we can conclude that the graph corresponding to

When P is constructed by keeping the columns of

Theorem 12

If

Proof

Since we keep the reverse topological order for the connected component, we obtain the lower triangular form. Let

7 Conclusion

In this article, we provide a complete characterization of the block diagonal reduction of the

These results can be leveraged to design fast numerical algorithms for computing determinants, permanents, eigenvalues, and eigenvectors by reducing large banded matrices into smaller independent subproblems. The block structure is also valuable in the context of inverse eigenvalue problems and in the spectral analysis of structured matrices.

The framework extends naturally to

Acknowledgments

The author acknowledges the editor and the anonymous referee for their suggestions in improving the manuscript. The author thanks Chanakya University, H. S. Subramanya, Bhagyashri Bhat, Srinivasa Rao for their support during the course of his research.

-

Funding information: The author states no funding involved.

-

Author contributions: The author confirms the sole responsibility for the conception of the study, presented results, and manuscript preparation.

-

Conflict of interest: The author states no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

[1] R. L. Burden and J. Douglas Faires, Numerical Analysis, Brooks Cole, Pacific Grove, CA, 2010. Search in Google Scholar

[2] R. H. Chan and K.-P. Ng, Fast iterative solvers for Toeplitz-plus-band systems, SIAM J. Sci. Comput. 14 (1993), no. 5, 1013–1019, https://doi.org/10.1137/0914061. Search in Google Scholar

[3] F. R. K. Chung and L. Lu, Complex Graphs and Networks, Vol. 107, American Mathematical Soc., Providence, 2006. 10.1090/cbms/107Search in Google Scholar

[4] C. M. da Fonseca, V. Kowalenko, and L. Losonczi, Ninety years of k-tridiagonal matrices, Studia Sci. Math. Hungar. 57 (2020), no. 3, 298–311, https://doi.org/10.1556/012.2020.57.3.1466. Search in Google Scholar

[5] C. M. da Fonseca, T. Sogabe, and F. Yilmaz, Lower k-Hessenberg matrices and k-Fibonacci, Fibonacci-p and Pell (p, i) numbers, Gener. Math. Notes 31 (2015), no. 1, 10–17. Search in Google Scholar

[6] C.M. da Fonseca and F. Yılmaz, Some comments on k-tridiagonal matrices: Determinant, spectra, and inversion, Appl. Math. Comput. 270 (2015), 644–647, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amc.2015.08.088. Search in Google Scholar

[7] Z. Du and C. M. da Fonseca, “The periodic determinantal property for (0, 1) double banded matrices”: a correction and some comments, Linear Multilinear Algebra. 72 (2024), no. 8, 1254–1258, https://doi.org/10.1080/03081087.2023.2176415. Search in Google Scholar

[8] M. Fiedler, Special matrices and their applications in numerical mathematics, Dover Publications, Mineola, New York, 2008. Search in Google Scholar

[9] C. F. Fischer and R. A. Usmani, Properties of some tridiagonal matrices and their application to boundary value problems, SIAM J. Numer. Anal. 6 (1969), no. 1, 127–142, https://www.jstor.org/stable/2156523. 10.1137/0706014Search in Google Scholar

[10] A. Fukuda, E. Ishiwata, M. Iwasaki, and Y. Nakamura, The discrete hungry Lotka-Volterra system and a new algorithm for computing matrix eigenvalues, Inverse Problems 25 (2008), no. 1, 015007, 10.1088/0266-5611/25/1/015007. Search in Google Scholar

[11] C. Gong, W. Bao, G. Tang, C. Min, and J. Liu, An efficient iteration method for Toeplitz-Plus-Band triangular systems generated from fractional ordinary differential equation, Math. Probl. Eng. 2014 (2014), no. 1, 194249, https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/194249. Search in Google Scholar

[12] J.-T. Jia, R. Xie, X.-Y. Xu, S. Ni, and J. Wang, A bidiagonalization-based numerical algorithm for computing the inverses of (p, q)-tridiagonal matrices, Numer. Algorithms 93 (2023), no. 2, 899–917, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11075-022-01446-0. Search in Google Scholar

[13] J.-T. Jia, Y.-C. Yan, and Q. He, A block diagonalization based algorithm for the determinants of block k-tridiagonal matrices, J. Math. Chem. 59 (2021), no. 3, 745–756, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10910-021-01216-8. Search in Google Scholar

[14] J. Jia, T. Sogabe, and M. El-Mikkawy, Inversion of k-tridiagonal matrices with Toeplitz structure, Comput. Math. Appl. 65 (2013), no. 1, 116–125, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.camwa.2012.11.001. Search in Google Scholar

[15] W. Kratz, Banded matrices and difference equations, Linear Algebra Appl. 337 (2001), no. 1–3, 1–20, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0024-3795(01)00328-7. Search in Google Scholar

[16] T. McMillen, On the eigenvalues of double band matrices, Linear Algebra Appl. 431 (2009), no. 10, 1890–1897, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.laa.2009.06.026. Search in Google Scholar

[17] R. Sedgewick and K. Wayne, Algorithms, Addison-Wesley Professional, Boston, MA, 2011. Search in Google Scholar

[18] T. Sogabe and F. Yılmaz, A note on a fast breakdown-free algorithm for computing the determinants and the permanents of k-tridiagonal matrices, Appl. Math. Comput. 249 (2014), 98–102, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amc.2014.10.040. Search in Google Scholar

[19] S. Takahira, T. Sogabe, and T.S. Usuda, Bidiagonalization of (k, k+1)-tridiagonal matrices, Spec. Matrices 7 (2019), no. 1, 20–26, https://doi.org/10.1515/spma-2019-0002. Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- 1-Sylvester matrices

- Lower and upper bounds for the eigenvalues of a pentadiagonal matrix arising in the Hodrick-Prescott filter

- Research Articles

- Spectral deviations of graphs

- Explicit inverse of symmetric, tridiagonal near Toeplitz matrices with strictly diagonally dominant Toeplitz part

- Matrices having a positive determinant and all other minors nonpositive

- On the permutation polytopes of some cyclic groups

- Potential counter-examples to a conjecture on the column space of the adjacency matrix

- Unit group of the ring of negacirculant matrices over finite commutative chain rings

- On the maximal Aa -index of graphs with a prescribed number of edges

- A cospectral construction for the generalized distance matrix

- Test matrices with specified eigenpairs for the symmetric positive definite generalized eigenvalue problem

- Minimum trace norm of real symmetric and Hermitian matrices with zero diagonal

- Block diagonalization of (p, q)-tridiagonal matrices

- A matrix variate inverse Lomax distribution

- The Jordan form of a triangular matrix

- Universal realizability of left half-plane spectra

- Distribution eigenvalues and temperature index of graphs

- What is a proper graph Laplacian? An operator-theoretic framework for graph diffusion

Articles in the same Issue

- 1-Sylvester matrices

- Lower and upper bounds for the eigenvalues of a pentadiagonal matrix arising in the Hodrick-Prescott filter

- Research Articles

- Spectral deviations of graphs

- Explicit inverse of symmetric, tridiagonal near Toeplitz matrices with strictly diagonally dominant Toeplitz part

- Matrices having a positive determinant and all other minors nonpositive

- On the permutation polytopes of some cyclic groups

- Potential counter-examples to a conjecture on the column space of the adjacency matrix

- Unit group of the ring of negacirculant matrices over finite commutative chain rings

- On the maximal Aa -index of graphs with a prescribed number of edges

- A cospectral construction for the generalized distance matrix

- Test matrices with specified eigenpairs for the symmetric positive definite generalized eigenvalue problem

- Minimum trace norm of real symmetric and Hermitian matrices with zero diagonal

- Block diagonalization of (p, q)-tridiagonal matrices

- A matrix variate inverse Lomax distribution

- The Jordan form of a triangular matrix

- Universal realizability of left half-plane spectra

- Distribution eigenvalues and temperature index of graphs

- What is a proper graph Laplacian? An operator-theoretic framework for graph diffusion