Healthcare Workforce Shortages: Evidence from Communist and Postcommunist Bulgaria

-

Ralitsa I. Simeonova-Ganeva

Ralitsa I. Simeonova-Ganeva is an Associate Professor at the Faculty of Economics and Business Administration at Sofia University St. Kliment Ohridski, Sofia, Bulgaria. She is also the Director of the Master’s program in Applied Econometrics and Economic Modeling at the same university. Her general research interests include economic growth, labor economics and human capital, and economic history.and Kaloyan I. Ganev

Kaloyan I. Ganev is an Associate Professor at the Faculty of Economics and Business Administration at Sofia University St. Kliment Ohridski, Sofia, Bulgaria. He is also the Director of the PhD program in Applied Econometrics and Economic Modeling at the same university. His research interests include economic growth, business cycles, applied econometrics, economic forecasting, and economic history.

Abstract

This study assesses healthcare workforce shortages in Bulgaria across three periods: communism (1944–1989), transition (1990–2002), and EU integration (2003 onward). Using historical data and benchmarking against European medians, the authors analyze trends among physicians, dentists, nurses, and midwives. They find that during communism, massive investment until the mid-1970s, and restricted international mobility led to significant human capital accumulation in healthcare. For the 1980s, they identify serious issues due to reduced subsidies and low remuneration. The authors point to a substantial brain drain and care drain following the labor market opening during the transition, while they argue that the reform implemented at the end of this period exacerbated nursing staff losses. For the period of EU integration, they observe positive reversals, but also emphasize that shortages persist. This, they argue, can be explained by the inability of the educational system to overcome the shortages.

Introduction

Over the past few decades, global demand for healthcare has increased significantly (Culyer and Newhouse 2000). Both demographic and socioeconomic determinants have contributed to this trend (Fuchs 1972; Gu 2020). Higher life expectancy, population growth, and aging have been among the main demographic factors, while the socioeconomic factors have included technological progress, increases in income and welfare, better healthcare access and health culture, and rising growth of chronic illnesses (Simeonova-Ganeva and Ganev 2023). The increased demand for healthcare has led to growing pressure to provide appropriate health professionals. Training personnel for such professions is intense, lengthy, and requires high levels of financial support. The importance of public funding and policy has increased significantly, particularly regarding education and training. Simultaneously, issues related to staff retention and attracting healthcare professionals from abroad have emerged.

These issues have been recognized by the world’s leading economies who have responded by providing considerable financing for training medical staff (Frenk et al. 2022). Nevertheless, investment has still been insufficient, and today, the global demand for healthcare professionals significantly exceeds the supply. While the abovementioned factors have undoubtedly contributed to this, the decision of major economies to reduce public spending on training (He, Whang, and Kristo 2021) and attract specialists from abroad has also played a part. Consequently, countries affected by brain drain have further reduced their training expenditure.

Approximately 20 years ago, according to the World Health Organization (WHO), the estimated shortage of medical staff across all countries amounted to four million.[1] Liu et al. (2017) suggested that under the assumption of “no policy change”, by 2030, this shortage will rise to 15 million. In the United States alone, financial services company IHS Markit expected that by 2034, there would be over 48,000 unfilled vacancies for primary care physicians (Dall et al. 2021). Currently, the situation in the European Union (EU) is similar.[2]

Owing to the highly competitive global market, the regional distribution of medical staff has become increasingly uneven. As a result, these shortages have become more pronounced in countries with relatively low wages. The Covid-19 pandemic further aggravated the issue worldwide. It negatively affected people’s views about working in the health sector, as the health crisis that emerged exposed medical staff to excessive levels of stress, burnout, and life safety hazards (Simeonova-Ganeva and Ganev 2023).

The growing demand for healthcare and the increasing shortage of medical professionals suggest that the value of the latter will increase. Physicians, dentists, nurses, and midwives have already become rival goods in the international resource flow. In this setting, countries and regions offering higher remuneration, better working conditions, and opportunities for career development are at an advantage.

Some of the most unfavorable developments in this area have been seen in postcommunist countries. In general, before the fall of the Iron Curtain, these countries were characterized by significant long-term investment in medical staff training and a large number of healthcare specialists (Elmer et al. 2022). However, their earnings and quality of life were significantly lower than those of the healthcare staff working in high-income countries during the transition period (Field 1988; Afford and Lessof 2006). The opening up of the labor market following the process of democratization and EU accession and increasing EU demand for nurses and physicians accelerated the outflow of health workers (Adovor et al. 2021). Thus, investment in training the healthcare workforce in Eastern European countries was less effective.

In all these respects, developments in Bulgaria during the period of communism (1944–1989), transition (1990–2002), and EU integration (2003 and later) were not substantially different.[3] The country’s relatively low wages caused a net outflow of medical professionals during the transition period. Moreover, since Bulgarian is not a widely spoken language, attracting specialists from abroad was difficult. As a result, issues related to the inadequate number of medical specialists accumulated and the quality of health services deteriorated. Survey data show that 73 % of Bulgarians consider access to competent medical staff the leading determinant of health service quality.[4] This seems to be corroborated by the widespread perception that healthcare is relatively worse now compared to during communism (Wike et al. 2019). In addition, some studies (e.g., Iliev 2004) point out that, following the political changes of the 1990s, public health services in Bulgaria have dramatically deteriorated, resulting in more widespread illness and disease. The root of these problems appears to be a shortage of medical professionals. A reasonable solution would therefore be to generate new human capital, retain existing capital, and make efforts to encourage the specialists who emigrated to return. However, human capital formation is a long-term process, and the accumulation of stocks takes decades. Therefore, both analysis and policy actions should be strongly rooted in historical processes.

Overall, research on healthcare during both communist and postcommunist times is limited and there is insufficient evidence regarding the issues of human capital availability. Another weakness of the literature is that it treats the postcommunist period as homogeneous. Specifically for Bulgaria, two different sub-periods could in fact be clearly identified: the transition to the market economy and effective EU integration.

The aim of this study is to assess healthcare workforce shortages in Bulgaria across three periods: communism (1944–1989), transition (1990–2002), and EU integration (2003 onward). The study is structured as follows. First, a description of the indicators, data sources, and methodology is provided. Second, using the reference indicator values for a large group of European countries, the shortages of physicians, dentists, nurses, and midwives in Bulgaria are assessed. In the following two sections, a historical record of the policies implemented with regard to public healthcare and human capital is presented. Specifically, the study reviews the relevant positive, albeit insufficient, developments during communism, as well as the substantial brain and care drains during transition. Fourth, an estimate of personnel flow, particularly the extent to which the inflow of graduates corresponds to the outflow, is offered for the EU integration period. Lastly, the paper concludes by outlining a set of policy implications and recommendations.

Data and Methodology

We use data from several sources. Historical data on the aggregate numbers of physicians, dentists, midwives, and nurses in Bulgaria for the period from 1931 to 2022 (with some gaps for the late 1930s and 1940s) are available from Bulgaria’s official statistical yearbooks. They are complemented with Eurostat data available for European countries (time coverage varies by country and indicator), which contain detailed information on practicing physicians, dentists, midwives, and nurses for the period from 1960 to 2022 as well as for physicians, subdivided by category, for the period from 1985 to 2022. Data on the number of students (Bulgarian nationals and foreigners) graduating from Bulgarian medical universities and licensed to practice these four professions from 1980 to 2022 were obtained from the Bulgarian National Statistical Institute’s specialized publications on education in Bulgaria. Owing to the significant number of missing observations until 2011, we restrict our sample to the period from 2012 to 2022. Population data for the period from 1960 to 2022 are available from Eurostat. Lastly, data on life expectancy at birth in Bulgaria from 1960 to 2021 were taken from the World Bank’s World Development Indicators database.

Conceptually, shortages should be measured as the difference between supply and demand. As the demand for healthcare staff largely depends on the demand for medical services, shortage measures could be based on the extent to which the demand for health services corresponds to the supply. While the latter is relatively straightforward to quantify, there are various measures for service demand offered in the literature, for example, based on the spread of diseases or the extent to which populations are aging (Salsberg et al. 2017) and the minimum number of visits to physicians per person required (Patlak and Levit 2009). However, these measures are difficult to implement. Therefore, institutions often resort to subjective estimates (Institute of Medicine 1989), risking biased results. Alternatively, objectively defined reference values (benchmarks) that approximate the target state can be applied (Borisova and Manoilova 2020). Natural candidates for such reference values are descriptive (summary) statistics that characterize the frequency distributions of the corresponding indicators.

To identify shortages of medical staff in Bulgaria, we chose the benchmark approach, which we operationalized for this purpose. Given the geographical coverage of our sample data, we considered the frequency distributions of the indicators across the European countries for which they were available. In principle, for symmetric distributions, means (arithmetic or weighted) are appropriate benchmarks. However, the distribution of medical staff data across the countries analyzed was characterized by considerable asymmetry. Therefore, we chose to identify our benchmark values using medians instead. Specifically, we computed the year-by-year median values of the numbers of physicians, dentists, midwives, and nurses per 100,000 population. We then assessed the relative position of Bulgaria by computing the differences between its values and the corresponding median values. Negative differences were understood as shortages per 100,000 population, while positive differences were considered an indication of a relatively better situation. Lastly, we computed absolute nationwide shortages by scaling the standardized values by population size.

This choice of method could be viewed as a major limitation of our study, as alternatives might produce different results. At the same time, it has the advantage of being free from assumptions, conservative, and robust to various types of statistical distribution.

Shortages

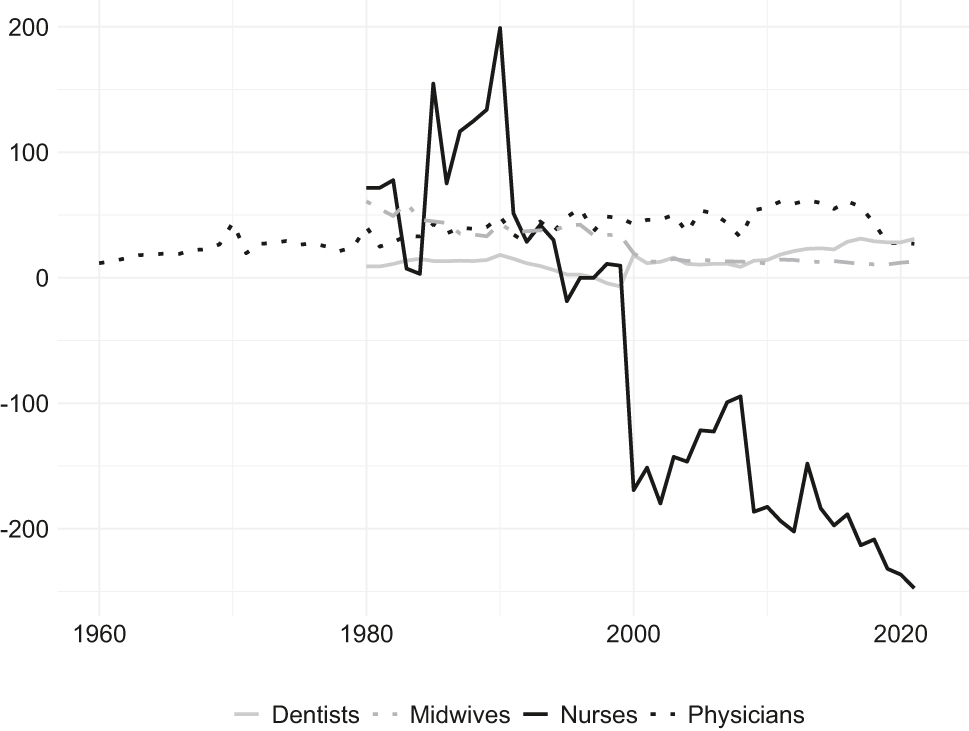

The results of our calculations show that during the period from 1960 to 2021, there was no shortage of physicians, as their number per 100,000 people was above the computed median. A similar observation applies to midwives from 1980 to 2021 (data for previous years are unavailable). Concerning dentists, only a brief period (1998–1999) of shortage was witnessed following the public sector layoffs that started in the early 1990s. The 1999 healthcare reform that allowed dentists to set up private practices put an end to the shortage. Although the number of nurses per 100,000 people was volatile before 1989, there was no shortage. At the beginning of the transition, this number fell sharply and a short-lived shortage appeared in 1995. However, the situation did not improve sustainably in the years that followed. After the 1999 healthcare reform, the situation in fact began to deteriorate dramatically, and a persistent shortage has been observed ever since (Figure 1).

Specialists per 100,000 population (deviation from benchmarks), 1960–2021. Source: Eurostat, authors’ calculations.

In 2021, the number of physicians and dentists per 100,000 population in Bulgaria ranked higher than the median (429.6 vs. 402.5 and 109.9 vs. 78.9). Although the figures superficially indicate a more favorable situation, relatively speaking, if they are broken down by specialist type, several shortages can be identified. For example, in the same year, the number of general practitioners (GPs) per 100,000 population was 57.4, while the median was 72.1. This meant an absolute shortage of 1,000 physicians or approximately one-quarter of their total number. Similarly, the number of psychiatrists per 100,000 population was 10.2 against a median of 17.0, corresponding to an absolute shortage of 460 physicians, or over 70 % of their total (Simeonova-Ganeva and Ganev 2023).

In 2021, there was a considerable shortage of nurses in Bulgaria with only 419.0 per 100,000 population compared with a median of 666.3 per 100,000 population. In absolute terms, this shortage amounted to 16,900 nurses. Given that the Bulgarian Ministry of Health considers 2:1 to be the nurse-to-physician ratio required to ensure the health system functions normally,[5] this shortage would in fact amount to approximately 29,000, a number considerably higher than the availability at the time. For midwives, the number per 100,000 population was relatively favorable (47.5 vs. a median of 34.6), but the midwives-to-gynecologists ratio was still significantly lower than the WHO recommendation of 3:1.[6] In the following sections, we review and explain the historical and policy background that has led to the present state of healthcare personnel in Bulgaria.

Creation of a Health Workforce during Communism

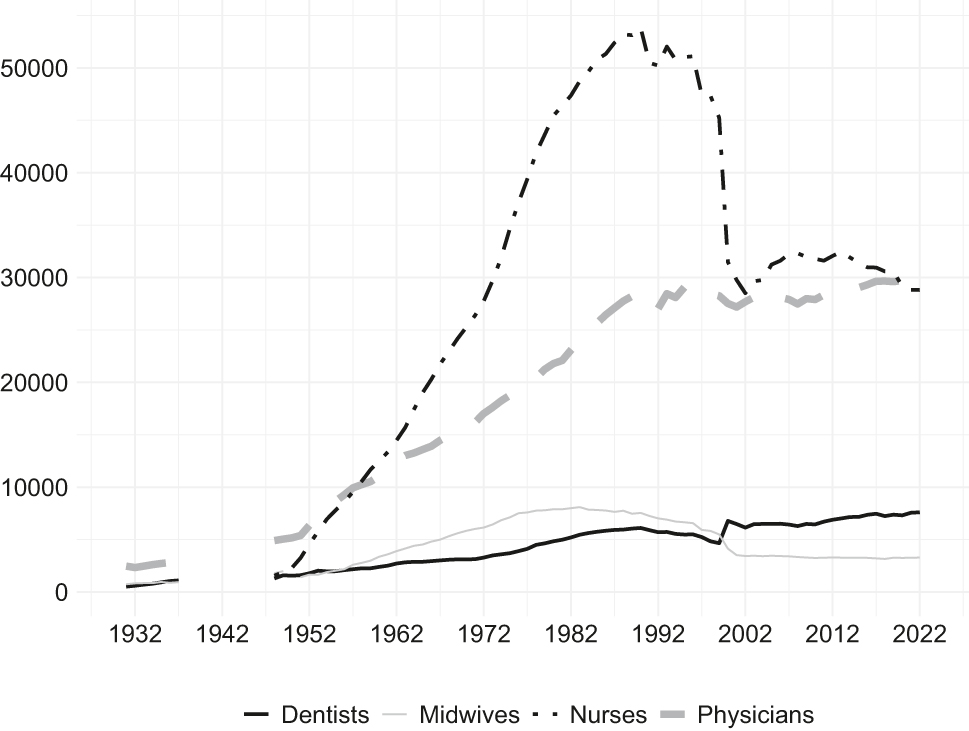

During the communist period in Bulgaria, there was a tenfold increase in the number of medical staff (Figure 2). The main explanation for this lies in massive investment in healthcare workforce training and education and intensive healthcare development policies. Most of this investment was front-loaded in the first decades of communism (until the mid-1970s), while later years largely benefited from inherited inertia.

Number of health specialists, 1931–2022. Source: General Directorate of Statistics, Central Statistical Office, National Statistical Institute.

Until the end of World War II, the penetration of healthcare services in Bulgaria was low. Correspondingly, the size of the healthcare workforce was not large enough to provide adequate access to health services. For example, in 1937, according to the General Directorate of Statistics (Glavna direkt͡sii͡a na statistikata) despite positive developments since the beginning of the 1930s, the total number of health specialists was just below 5,000 (Glavna direkt͡sii͡a na statistikata 1938). This corresponded to 0.8 health specialists per 1,000 people.[7] The social and political changes after World War II led to the adoption of the Soviet model of public healthcare, a highly centralized system based on the principles of social medicine (Angelova 2021). This was associated with a steep rise in the demand for health workers on behalf of the central planning authorities. Similar to the Soviet experience from the 1920s and 1930s (Angelova 2021), it was virtually impossible to implement health policies because of the scarcity of medical staff. Hence, the education and training of medical staff was significantly enhanced. For example, the number of medical secondary schools increased from 4 in 1944 (with fewer than 500 students) to 19 in 1952 (with over 4,000 students). According to the Bulgarian Central Statistical Office (T͡sentralno statistichesko upravlenie pri Ministerskii͡a sŭvet, CSU), in 1944, the only institute of higher education was the Faculty of Medicine at Sofia State University, which had fewer than 5,000 students. In 1950, two medical universities were established, and the number of students exceeded 7,700 (Central Statistical Office 1959). In 1948, the health workforce had already reached nearly 9,600. By 1946, four schools for nurses had been established (Stoeva et al. 2019). The policies of massive investment in human capital led to a considerable increase in the number of healthcare specialists despite the political repression of non-communist intellectuals in the post-World War II period.[8]

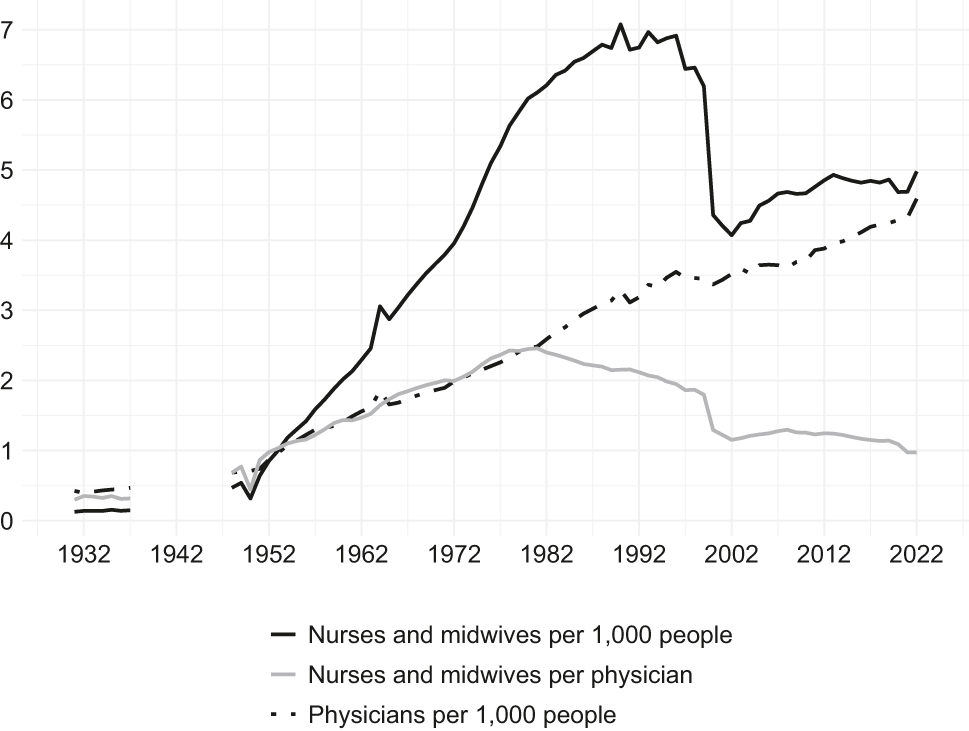

In the first two decades of communism, developments were impressive: when it came to the number of physicians, the average growth rate in the 1950s was 7.7 % and the corresponding increase for nurses was 20.4 %. Growth rates were lower over the decades that followed. Specifically, in the 1980s, the numbers of physicians and nurses increased by 2.9 % and 2.0 %, respectively. Adequate primary care coverage was achieved only in 1955–1956, when the recommended ratio of at least 2.5 physicians, nurses, and midwives per 1,000 people were achieved.[9] This ratio improved in subsequent years, reaching 9.88 in 1989. The number of nurses and midwives per physician reached the value of one in 1953–1954 (Figure 3). It exceeded the value of two in 1960 and reached the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s (OECD) average of three in 1966.[10]

Number of health specialists per 1,000 people and number of nurses and midwives per physician, 1931–2022. Source: Authors’ calculations.

The lower growth rates in the second third of the communist period were the result of the smaller number of medical students and increasing number of retiring health workers. Bulgaria’s rising external debt in the late 1970s and the 1980s and its tighter budget constraints also adversely affected investment in healthcare (Simeonova-Ganeva, Ganev, and Angelova 2022). Further, central planning authorities considered healthcare to be a sector that only absorbs funds, without generating budget revenues. Therefore, limited resources were allocated to it (Jakovljevic et al. 2018). This is indirectly evidenced by the data from 1950–1970: despite the implementation of vocational training programs along with the provision of professional placements, nurses’ wages remained relatively low. This acted as a disincentive to choose the profession. Similarly, the possibility of additional earnings from private medical practices was eliminated in 1972. The medical profession became less attractive to young people, which subsequently contributed to the declining quality of healthcare (Stoeva et al. 2019).

Despite the quantitative improvements, the scarcity of specialists was not fully overcome, and the quality of health services did not match the expectations of the ruling party. For example, in the 1980s, the communist authorities concluded that investment in human capital formation should be increased to effectively compensate for the relative dearth of medical staff. In addition, they pointed out that due to the inadequate supply of nurses and health workers with secondary school training as well as the lack of modern equipment,[11] physicians were occupied with atypical tasks, which in turn led to ineffectiveness (Apostolov and Gogov 1986). The number of medical students increased, but at the same time, the quality of their education and training could not be assured (Marcheva 2016). Nevertheless, the overall impact of the policies aimed at human capital formation in healthcare was positive due to the unfavorable starting conditions (Simeonova-Ganeva, Ganev, and Angelova 2022).

A Bumpy Transition: Inadequate Reforms, Brain Drain, and Care Drain

At the beginning of the 1990s, the former Eastern bloc countries – including Bulgaria – saw a reversal of the trends that had been observed during communism. This development is often used to justify the (not necessarily valid) claim that the health services available under central planning were better and more accessible. The poor performance of the Bulgarian economy and the inefficient management of the public sector led to severe underfunding of healthcare: budgets were small, and payment of supplies, wages, etc. were highly irregular (Iliev 2004). Private healthcare was almost nonexistent because of the meager demand for private health services. Many healthcare professionals were forced to emigrate or change their careers. At the beginning of the transition, it was difficult to access foreign labor markets, but the unfavorable pay gap and rising demand for medical labor worldwide still led to substantial emigration. This resulted in a marked brain drain and, in parallel, also a care drain. It was also mostly young health specialists who were emigrating, which further aggravated the issues related to aging human resources in healthcare. As a result, continuing to work after retirement is currently not unusual (Karanikolos, Kühlbrandt, and Rechel 2014).

Within just a year, in 1991, the number of physicians in Bulgaria dropped by 6.1 % (more than 1,700 physicians). By the end of 2002, the overall decline was 1.9 %. However, due to the substantial demographic decline, the number of physicians per 1,000 people increased from 3.29 in 1990 to 3.52 in 2002. During the same period, the number of dentists increased by 1.6 %. By the end of 2002, the most serious issues were related to the outflow of nurses and midwives. In 1990, there were 53,800 nurses but by 1991, this number had decreased by 6.2 % (3,300 nurses). Across the entire period from 1990 to 2002, the total decline was sizable (46.3 %). The largest drop of approximately 14,000 was observed in 2000 with the following year seeing an additional decline of approximately 1,700. Thus, in 2002, the total number of nurses shrank to 28,500 (Simeonova-Ganeva and Ganev 2023).

Regarding the number of midwives in Bulgaria, a steady decline began during communism (in 1984). This trend persisted throughout the transition period with the number of midwives falling by 54 % between 1990 and 2002.

Obviously, when it came to nurses and midwives, developments were much more unfavorable than those concerning physicians. This can be explained by the implementation of two major reforms (Simeonova-Ganeva and Ganev 2023). First, the 1999 health sector reform resulted in the transformation of medical institutions into commercial entities. The management of these entities faced inadequate financial resources and the need to optimize costs. A quick solution turned out to be staff cuts, predominantly nurses and midwives. There was scarcely any alternative employment for the nurses and midwives who had been laid off, since public medical institutions were quasi-monopsonies in this respect. Unlike physicians and dentists, nurses and midwives could not open private practices. Consequently, many of them left the healthcare system for good. The second reform consisted of the adoption of the Code on Compulsory Social Security (entry into force in 2000), which increased the retirement age. Many nurses and midwives had to decide whether to retire earlier under the old rules or risk not being able to retire at all. The reason for this was that, in the event of them being laid off, they would not be able to acquire the number of years of service required under the new rules.

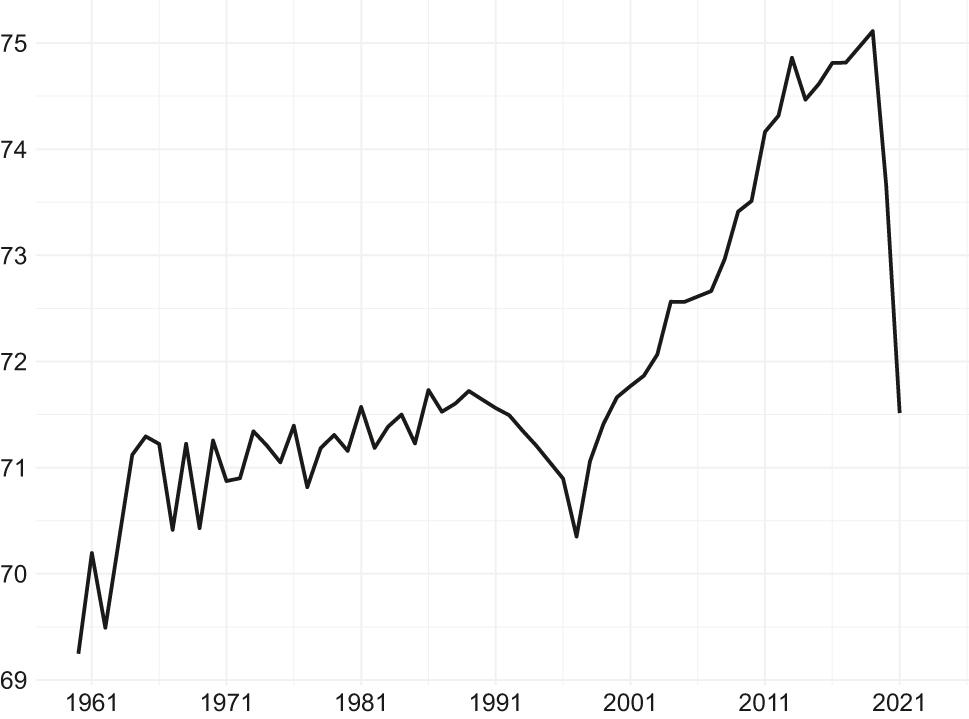

Hence, the health of the Bulgarian population was negatively affected, a finding that has also been confirmed by other studies (e.g., Romaniuk and Szromek 2016). Life expectancy declined dramatically, and its long-term upward trend was reversed. In 1997, it returned to the early-1960s level (Figure 4).

Life expectancy at birth, total (years), 1960–2021. Source: United Nations Population Division, Simeonova-Ganeva and Ganev 2023.

EU Integration: More Investment in Human Capital to Counter Outflows

During the years of EU integration, the output of the medical education and training system allowed for the maintenance of a positive, albeit relatively slow, growth in the number of graduates. This new positive trend reversal can be largely attributed to the process of convergence of Bulgaria’s income levels to EU averages, implying increased remuneration. Meanwhile, the private healthcare sector had also developed significantly.

EU integration, private healthcare development, modernization, rising remuneration, and targeted education policies positively contributed to the growth in the stocks of physicians and dentists. Their numbers increased by 6.7 % and 23.0 %, respectively, over the period from 2003 to 2021. The number of physicians reached a historical peak of over 29,700 in 2020, and the highest number of dentists (7,600) was recorded in 2021. Owing to the ongoing population decline, the number of physicians per 1,000 people increased: from 3.52 in 2002 to 4.32 in 2021. However, issues related to regional imbalances and substantial asymmetries among the medical fields remain (Dimova et al. 2018; Simeonova-Ganeva and Ganev 2023).

The number of midwives in Bulgaria became more stable during the period of EU integration. Since 2007, it has fluctuated in the range between 3,200 and 3,300 midwives. Nevertheless, the overall trend for the period from 2003 to 2021 was still negative, with a 4.9 % decline in the number of midwives.

Until recently, policymakers neglected the issue of the low wages of nurses and midwives in the public sector despite numerous protests. That said, educational incentives were introduced (lower tuition fees, higher number of state scholarships, etc.) to encourage more young people to study and practice nursing. From 2003 to 2021, the number of nurses increased by 1.1 %, reaching 28,800. This is admittedly a relatively low level, comparable with the one observed for the early 1970s. The number of nurses and midwives per physician declined from 1.15 in 2002 to 0.98 in 2021.

The dynamics of the above indicators do not fully reflect the issues related to the aging health workforce (Simeonova-Ganeva and Ganev 2023). Considerable growth in replacement demand is highly likely in the medium term, further exacerbating shortages. A key question that emerges is how to compensate for past and current outflow.

In Bulgaria, new graduates from Bulgarian medical universities have replenished the number of medical specialists. These graduates have been almost exclusively Bulgarian citizens; that is, they can be seen as contributing to the inflow into the system. Outflow is estimated as the difference between the available figures on the net change in the stocks of professionals and inflow (Simeonova-Ganeva and Ganev 2023).

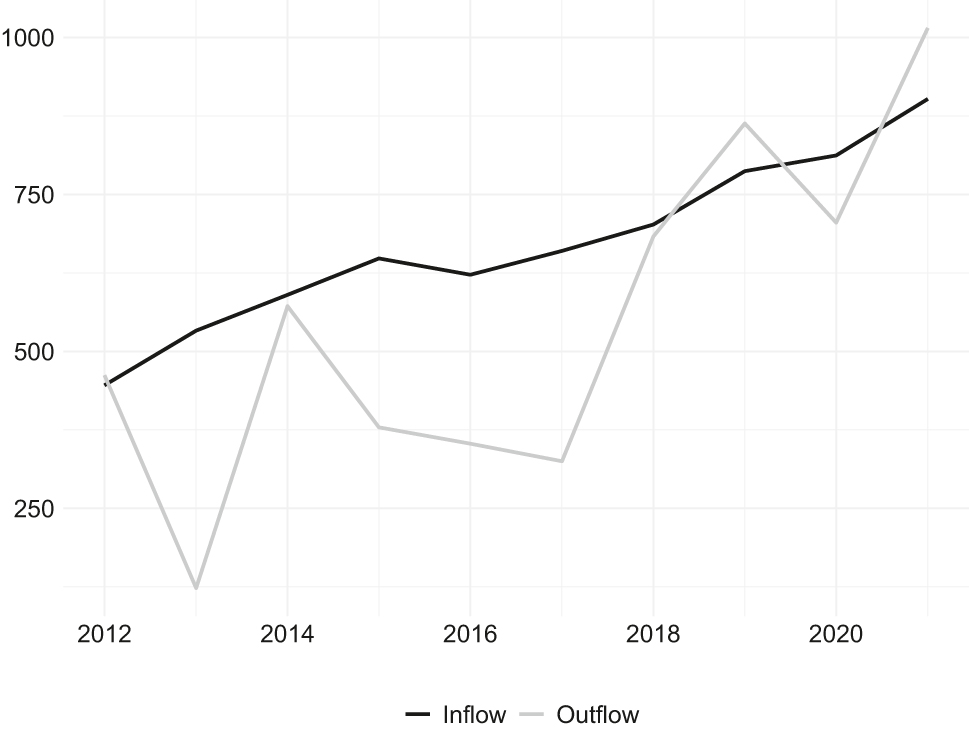

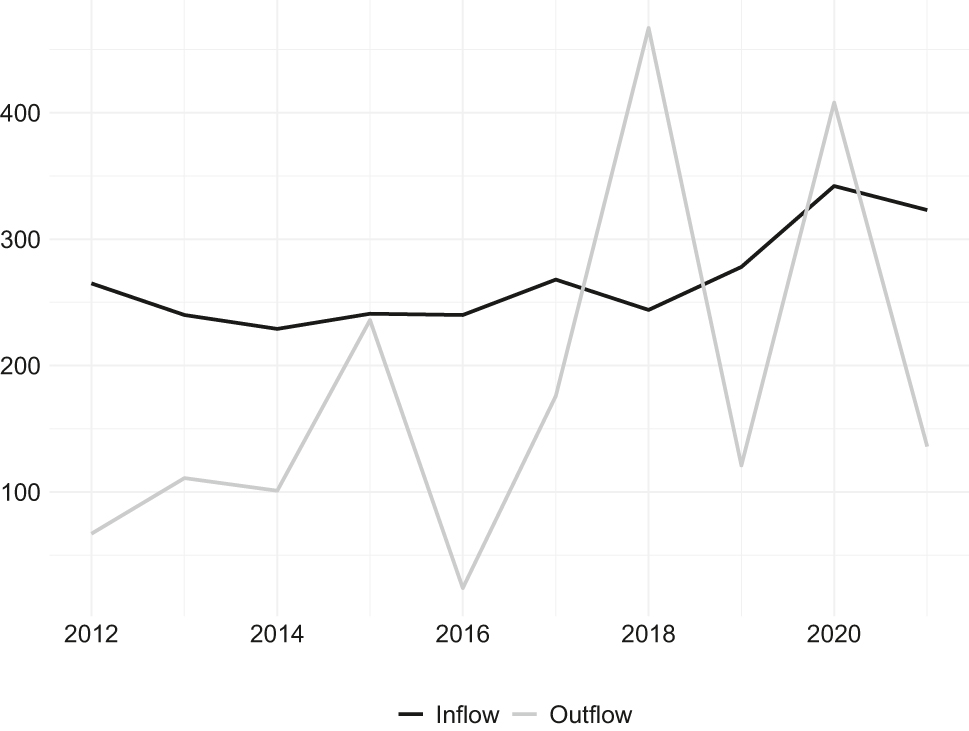

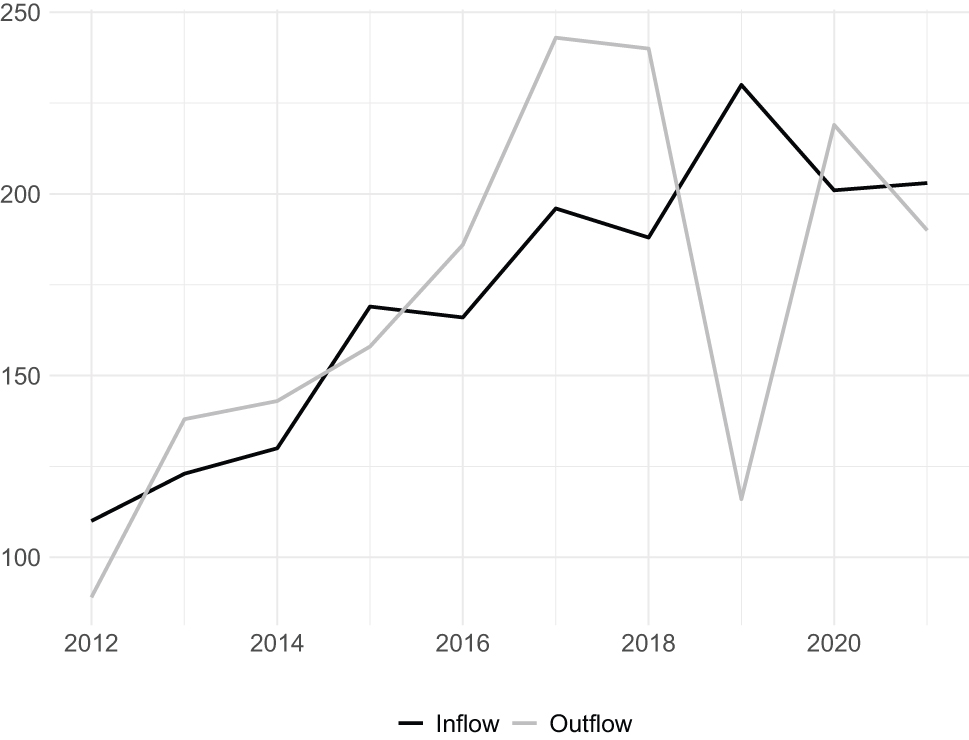

Specifically, from 2012 to 2021, an upward trend was observed for both the inflow and outflow of physicians. However, the faster rate of increase in outflow led to negative net flows after 2018 (Figure 5).[12] For some specialties, the dynamics had already been unfavorable for some years. According to the Bulgarian National Statistical Institute (NSI), the net decrease in the number of GPs over the period from 2012 to 2021 was approximately 650. This significant decline occurred despite the relatively high number of physicians specializing in general medicine (nearly 1,700 for the same period, according to the Ministry of Health).[13] The situation concerning the number of psychiatrists is similar and these negative trends are expected to continue (Simeonova-Ganeva and Ganev 2023). The policy response required to counteract this is to train a larger number of specialists. When it comes to dentists, inflows and outflows have recently offset one other; therefore, no serious issues can be identified for this group at present (Figure 6). For midwives, the outflow generally exceeded the inflow until 2018, although both had been on the rise. This is associated with the fact that it was impossible for Bulgarian medical universities to respond to the increasing replacement demand and train enough midwives (Figure 7).

Inflow and outflow of physicians (number), 2012–2021. Source: Authors’ calculations, Simeonova-Ganeva and Ganev 2023.

Inflow and outflow of dentists (number), 2012–2021. Source: Authors’ calculations, Simeonova-Ganeva and Ganev 2023.

Inflow and outflow of midwives (number), 2012–2021. Source: Authors’ calculations, Simeonova-Ganeva and Ganev 2023.

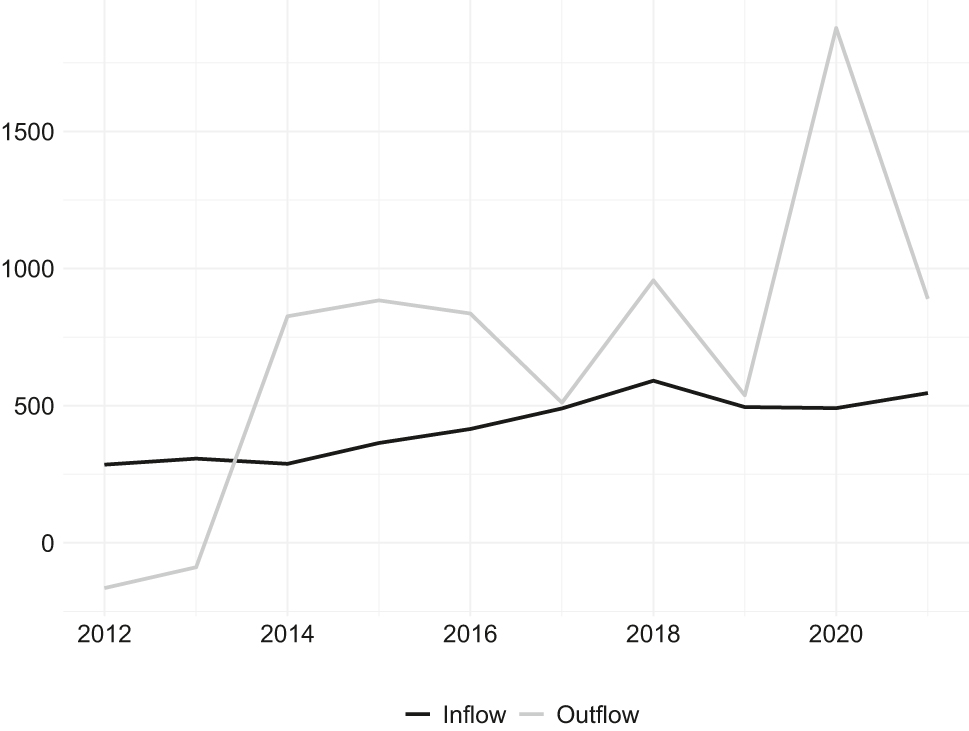

As expected, the situation concerning nurses has been the least favorable. Since 2014, the outflow of nurses has consistently exceeded the inflow (Figure 8). It is quite clear that the training system has been unable to compensate for both the current staff losses and the shortages accumulated during the transition period. If zero outflow is assumed and medical universities do not see a significant increase in the number of nurse trainees, the existing shortage of nearly 17,000 nurses would take almost 30 years to eliminate. Overall, despite some positive trends since 2002, significant shortages of medical staff remain and, in the absence of a radical policy response, these shortages are expected to persist.

Inflow and outflow of nurses (number), 2012–2021. Source: Authors’ calculations, Simeonova-Ganeva and Ganev 2023.

Discussion and Conclusion

The policies of targeted investment in the healthcare system and medical education were the main determinants of the success of human capital formation during communism. However, two other factors also contributed to this favorable development. First, the economy was closed, and a brain drain was impossible. Second, the state-owned healthcare system was a monopsony with respect to the labor of medical staff: physicians, nurses, etc. had very limited options for alternative employment in healthcare, despite the relatively low remuneration. Over time, this led to these professions (especially nursing and midwifery) becoming less attractive. Substantial brain and care drains followed once restrictions were removed at the beginning of the transition. Consequently, the availability of medical staff deteriorated substantially. At the end of the transition period, the healthcare reform that was implemented resulted in the additional loss of a large number of nurses. Following the policy of increased investment in medical education, some positive trend reversals were observed during the EU integration period only. That said, the accumulated losses have not yet been overcome. Policy success is being further challenged by demographic aging, the risk of new pandemics, and increased patient expectations (Rechel, Richardson, and McKee 2014).

Our findings emphasize the importance of matching investment in education with competitive remuneration and decent working conditions in an open international labor market. Our findings also support the requirement for future policies to guarantee alternative employment opportunities for all types of medical staff in both the public and private sectors.

When it comes to the challenge of tackling the existing shortages, policymakers must acknowledge the severity of all the relevant issues (wages, working conditions, prospects for career development, etc.) in order to successfully design and implement future policy responses. The redesign of human capital formation policies should ensure better-quality medical education and research, as well as competitive remuneration. This involves upgrading the training facilities by investing in modern technologies. The latter could contribute to a better environment for professional and career development in Bulgaria by making it more compatible with modern standards. Thus, policies would create competitive advantages that not only counteract the brain drain but also appeal to professionals from abroad. The institutional framework should be improved to foster competition and provide mechanisms to reduce specialist overload. Policies should focus on retaining healthcare workers and encouraging those who emigrated to return, attracting foreign nationals graduating from Bulgarian medical universities, and re-recruiting those who have left the system.

About the authors

Ralitsa I. Simeonova-Ganeva is an Associate Professor at the Faculty of Economics and Business Administration at Sofia University St. Kliment Ohridski, Sofia, Bulgaria. She is also the Director of the Master’s program in Applied Econometrics and Economic Modeling at the same university. Her general research interests include economic growth, labor economics and human capital, and economic history.

Kaloyan I. Ganev is an Associate Professor at the Faculty of Economics and Business Administration at Sofia University St. Kliment Ohridski, Sofia, Bulgaria. He is also the Director of the PhD program in Applied Econometrics and Economic Modeling at the same university. His research interests include economic growth, business cycles, applied econometrics, economic forecasting, and economic history.

References

Adovor, Ehui, Mathias Czaika, Frederic Docquier, and Yasser Moullan. 2021. “Medical Brain Drain: How Many, Where and Why?” Journal of Health Economics 76: 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2020.102409.Search in Google Scholar

Afford, Carl, and Suszy Lessof. 2006. “The Challenges of Transition in CEE and the NIS of the Former USSR.” In Human Resources for Health in Europe. Edited by Carl-Ardy Dubois, Martin McKee, and Ellen Nolte, 193–213. Maidenhead: Open University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Angelova, Milena. 2021. “Vizionerstvo i zdrave: modelŭt “Semashko” i sŭvetizat͡sii͡ata na obshtestvenoto zdraveopazvane v Bŭlgarii͡a (1944–1951).” Balkanistic Forum 30 (3): 74–103. https://doi.org/10.37708/bf.swu.v30i3.4.Search in Google Scholar

Apostolov, Evgeni, and Petar Gogov. 1986. Akt͡selaracii͡a na zdraveopazvaneto. Sofia: Medicina i Fizkultura.Search in Google Scholar

Borisova, Boriana, and Aneta Manoilova. 2020. “Benchmarking kato metod za osŭshtestvi͡avane na organizat͡sionna promi͡ana v zdraveopazvaneto.” Obshta Medicina 22 (3): 67–72.Search in Google Scholar

Central Statistical Office. 1959. Zdraveopazvaneto v Narodna Republika Bŭlgarii͡a. Statisticheski sbornik. Sofia: Nauka i izkustvo.Search in Google Scholar

Culyer, Anthony John, and Joseph P. Newhouse. 2000. “Introduction: The State and Scope of Health Economics.” In Handbook of Health Economics. Vol. 1A. Edited by Anthony J. Culyer, and Joseph P. Newhouse, 1–10. Amsterdam: Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1574-0064(00)80159-6.Search in Google Scholar

Dall, Tim, Ryan Reynolds, Ritashree Chakrabarti, Daria Chylak, Kari Jones, and Will Iacobucci. 2021. The Complexities of Physician Supply and Demand: Projections from 2019 to 2034. Washington, D.C.: Association of American Medical Colleges. https://digirepo.nlm.nih.gov/master/borndig/9918417887306676/9918417887306676.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

Dimova, Antoniya, Maria Rohova, Stefka Koeva, Elka Atanasova, Lubomira Koeva-Dimitrova, Todorka Kostadinova, and Anne Spranger. 2018. “Bulgaria: Health System Review.” Health Systems in Transition 20 (4): 1–256.Search in Google Scholar

Elmer, Diána, Dóra Endrei, Noémi Németh, Lilla Horváth, Róbert Pónusz, Zsuzsanna Kívés, Nóra Danku, Tímea Csákvári, István Ágoston, and Imre Boncz. 2022. “Changes in the Number of Physicians and Hospital Bed Capacity in Europe.” Value in Health Regional Issues 32: 102–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vhri.2022.07.003.Search in Google Scholar

Field, Mark G. 1988. “The Position of the Soviet Physician: The Bureaucratic Professional.” The Milbank Quarterly 66 (S2): 182–201. https://doi.org/10.2307/3349922.Search in Google Scholar

Frenk, Julio, Lincoln C. Chen, Latha Chandran, Elizabeth O. H. Groff, Roderick King, Afaf Meleis, and Harvey V. Fineberg. 2022. “Challenges and Opportunities for Educating Health Professionals after the COVID-19 Pandemic.” The Lancet 400: 1539–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(22)02092-X.Search in Google Scholar

Fuchs, Victor R. 1972. “The Growing Demand for Medical Care.” In Essays in the Economics of Health and Medical Care. Edited by Victor R. Fuchs, 61–8. Cambridge/MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.Search in Google Scholar

Glavna direkt͡sii͡a na statistikata. 1938. Statisticheski godishnik” na t͡sarstvo Bŭlgarii͡a 1937. Sofia: Glavna direkt͡sii͡a na statistikata.Search in Google Scholar

Gu, Shengyu. 2020. “A Comparative Study of Increasing Demand for Health Care for Older People in China and the United Kingdom.” World Scientific Research Journal 6 (4): 218–51, https://doi.org/10.6911/WSRJ.202004_6(4).0023.Search in Google Scholar

He, Katherine, Edward Whang, and Gentian Kristo. 2021. “Graduate Medical Education Funding Mechanisms, Challenges, and Solutions: A Narrative Review.” The American Journal of Surgery 221: 65–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2020.06.007.Search in Google Scholar

Iliev, Ivan. 2004. Ikonomika na Bŭlgarii͡a prez perioda 1949–2001. Sofia: Dimitar Blagoev Printing House.Search in Google Scholar

Institute of Medicine. 1989. Allied Health Services: Avoiding Crises. Washington/D.C.: National Academy Press.Search in Google Scholar

Jakovljevic, Mihajlo, Carl Camilleri, Nemanja Rancic, Simon Grima, Milena Jurisevic, Kenneth Grech, and Sandra C. Buttigieg. 2018. “Cold War Legacy in Public and Private Health Spending in Europe.” Frontiers in Public Health 6: Article 215. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2018.00215.Search in Google Scholar

Karanikolos, Marina, Charlotte Kühlbrandt, and Erica Richardson. 2014. “Health Workforce.” In Trends in Health Systems in the Former Soviet Countries. Edited by B. Richardson, E. Richardson, and M. McKee, 77–90. Brussels: European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies.Search in Google Scholar

Lilkov, Vili, and Hristo Hristov. 2017. Bivshi khora po klasifikat͡sii͡ata na Dŭrzhavna sigurnost. Sofia: Ciela.Search in Google Scholar

Liu, Jenny X., Yevgeniy Goryakin, Akiko Maeda, Tim Bruckner, and Richard Scheffler. 2017. “Global Health Workforce Labor Market Projections for 2030.” Human Resources for Health 15: Article 11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-017-0187-2.Search in Google Scholar

Marcheva, Iliyana. 2016. Politikata za stopanska modernizat͡sii͡a v Bŭlgarii͡a po vreme na Studenata voĭna. Sofia: Letera.Search in Google Scholar

Patlak, Margie, and Laura Levit. 2009. “Supply and Demand in the Health Care Workforce.” In Ensuring Quality Cancer Care through the Oncology Workforce: Sustaining Care in the 21st Century: Workshop Summary. Edited by Margie Patlak and Laura Levit. Washington D.C.: National Academies Press.Search in Google Scholar

Rechel, Bernd, Erica Richardson, and Martin McKee. 2014. “Introduction.” In Trends in Health Systems in the Former Soviet Countries. Edited by Bernd Rechel, Erica Richardson, and Martin McKee, 1–7. Brussels: European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies.10.1093/eurpub/cku162.088Search in Google Scholar

Romaniuk, Piotr, and Adam R. Szromek. 2016. “The Evolution of the Health System Outcomes in Central and Eastern Europe and their Association with Social, Economic and Political Factors: An Analysis of 25 Years of Transition.” BMC Health Services Research 16: Article 95. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-016-1344-3.Search in Google Scholar

Salsberg, Edward, Nicholas Mehfoud, Leo Quigley, Clese Erikson, and Afsoon Roberts. 2017. The Future Supply and Demand for Infectious Disease Physicians. Washington/D.C.: The George Washington University Health Workforce Institute. https://www.idsociety.org/globalassets/idsa/policy--advocacy/current_topics_and_issues/workforce_and_training/background/gw-the-future-supply-and-demand-for-infectious-disease-physicians-3-17-17-final.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

Simeonova-Ganeva, Ralitsa, and Kaloyan Ganev 2023. Health Workforce Shortages. BCEA Analysis No. 03/2023. Sofia: Bulgarian Council for Economic Analysis (BCEA).Search in Google Scholar

Simeonova-Ganeva, Ralitsa, Kaloyan Ganev, and Radostina Angelova. 2022. “Bulgaria: Skill Imbalances and Policy Responses.” In Skill Formation in Central and Eastern Europe: A Search for Patterns and Directions of Development. Edited by Vidmantas Tūtlis, Jörg Markowitsch, Jonathan Winterton, and Samo Pavlin, 291–314. Oxford: Peter Lang.Search in Google Scholar

Stoeva, Teodora, Dimitar Shopov, Tanya Paskaleva, and Biyanka Tornyova. 2019. “Profesii͡ata medit͡sinska sestra – minalo, nastoi͡ashte.” Meditsinski Pregled Sestrinsko Delo 51 (1): 20-6.Search in Google Scholar

Wike, Richard, Jacob Poushter, Laura Silver, Kat Devlin, Janell Fetterolf, Alexandra Castillo, and Christine Huang. 2019. European Public Opinion Three Decades After the Fall of Communism. Washington, D.C.: Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2019/10/15/european-public-opinion-three-decades-after-the-fall-of-communism/.Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter on behalf of the Leibniz Institute for East and Southeast European Studies

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Editorial

- Articles

- The United Nations General Assembly Resolution on Srebrenica and the Struggle Against Genocide Denial

- Central South Slavic Linguistic Taxonomies and the Language/Dialect Dichotomy: Rhetorical Strategies and Faulty Epistemologies

- When Drniš Came to the Sea: Croatian Nationalism, Dalmatian Regionalism, and the Politics of Identity, 1990–2001

- Healthcare Workforce Shortages: Evidence from Communist and Postcommunist Bulgaria

- Interview

- Serbia’s New Student Movement: A Conversation with Dubravka Stojanović

- Book Reviews

- Roberto Belloni: The Rise and Fall of Peacebuilding in the Balkans

- Agustín Cosovschi: Les sciences sociales face à la crise: Une histoire intellectuelle de la dissolution yougoslave (1980–1995)

- Anastasiia Kudlenko: Security Governance in Times of Complexity. The EU and Security Sector Reform in the Western Balkans, 1991–2013

- Liridon Lika: Kosovo’s Foreign Policy and Bilateral Relations

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Editorial

- Articles

- The United Nations General Assembly Resolution on Srebrenica and the Struggle Against Genocide Denial

- Central South Slavic Linguistic Taxonomies and the Language/Dialect Dichotomy: Rhetorical Strategies and Faulty Epistemologies

- When Drniš Came to the Sea: Croatian Nationalism, Dalmatian Regionalism, and the Politics of Identity, 1990–2001

- Healthcare Workforce Shortages: Evidence from Communist and Postcommunist Bulgaria

- Interview

- Serbia’s New Student Movement: A Conversation with Dubravka Stojanović

- Book Reviews

- Roberto Belloni: The Rise and Fall of Peacebuilding in the Balkans

- Agustín Cosovschi: Les sciences sociales face à la crise: Une histoire intellectuelle de la dissolution yougoslave (1980–1995)

- Anastasiia Kudlenko: Security Governance in Times of Complexity. The EU and Security Sector Reform in the Western Balkans, 1991–2013

- Liridon Lika: Kosovo’s Foreign Policy and Bilateral Relations