Abstract

Background and aims:

Individuals with non-acute pain are challenged with variable pain responses following surgery as well as psychological challenges, particularly depression and catastrophizing. The purpose of this study was to compare pre- and postoperative psychosocial tests and the associated presence of sensitization on a cohort of women undergoing elective laparoscopic surgery for non-acute pain defined as pain sufficient for surgical investigation without persistent of chronic pain.

Methods:

The study was a secondary analysis of a previous report (Am J Obstet Gynecol 2014 Oct;211(4):360–8.). The study was a prospective cohort trial of 77 women; 61 with non-acute pain and 16 women for a tubal ligation. The women had the following tests: Pain Disability Index, Pain Catastrophizing Scale, CES-D (Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale) depression scale and the McGill Pain Scale (short form) as well as their average pain score and the presence of pain sensitization. All test scores were correlated together and comparisons were done using paired t-test.

Results:

There were reductions in pain and psychosocial test scores that were significantly correlated. Pre-operative sensitization indicated greater changes in psychosocial tests.

Conclusions:

There was a close association of tests of psychosocial status with average pain among women having surgery on visceral tissues. Incorporation of these tests in the pre- and postoperative evaluation of women having laparoscopic surgery appears to provide a means to a broader understanding of the woman’s pain experience.

1 Introduction

Operative laparoscopy is a very common procedure undertaken for a wide variety of gynecological disorders [1]. While initially developed as diagnostic procedure it now is associated with minor (tubal ligation) and complex operative procedures (hysterectomy, pelvic floor reconstruction and extensive cancer surgery) [2], [3], [4]. The more common operative procedures for non-acute pain are directed to the diagnosis and treatment conditions of endometriosis, adhesions, pelvic inflammatory disease, and various ovarian disorders [5], [6], [7], [8].

Postsurgical chronic pain (PSCP) is being recognized as a common condition that requires improved approaches for a better understanding and treatment [9]. One of the proposed approaches is the use of both pain testing and psychological testing strategies. A recent study of the postoperative pain outcomes in several surgical conditions has emphasized the importance of pain sensitization as a predictor of clinical pain [10]. Recently a decision has been made to include chronic postsurgical pain (CPSP) in the new version of The International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11 that will be released in 2018) [11].

Pain sensitization can be defined as “Increased responsiveness of nociceptive neurons to their normal input, and/or recruitment of a response to normally sub-threshold inputs” [12]. Peripheral sensitization is considered to be increased responsiveness and reduced threshold of nociceptive neurons in the periphery while central sensitization is increased responsiveness of nociceptive neurons in the central nervous system to their normal or sub-threshold afferent input [12]. The subject has been extensively reviewed, recently in the transition from acute to chronic pain after surgery [10], [13]. Clinically, sensitization may only be inferred indirectly from measureable phenomena such as hyperalgesia or allodynia [12]. Pain sensitization influences the outcomes of surgery in a number of clinical situations [10], [14], [15], [16].

The detection of sensitization among women with chronic pelvic pain is established by the presence of allodynia and reduced pain thresholds in the dermatomes that supply the innervations to the pelvic structures. Among women with chronic pelvic pain, such sensitization has been shown to be frequent and detectable at the bedside and importantly can discriminate somatic from visceral disease [14]. Mechanosensory testing of women having hysterectomy indicated positive testing detected greater postoperative pain [17]. Pain sensitivity testing pre- and post-operatively predicted post-operative heat pain and pain with movement when tested 10 days after a laparoscopic tubal ligation [18]. In a cross sectional study of women with biopsy proven endometriosis, pelvic pain and control volunteers, and sensitization was common in those with pain whether or not they had endometriosis [15]. A prospective study of women with non-acute pain reported that pain sensitization as defined by the presence of allodynia, preoperative average pain and catastrophizing could predict the post-operative pain experience [19]. The surgery resulted in an overall reduction in pain associated with a reduction in allodynia, possibly due to the removal of a nociceptive focus as a source off the pain [19].

The current literature also supports psychosocial testing as part of the biopsychosocial framework of care for pelvic pain [20–22]. Consistently problematic areas that affect the outcome of surgery are depression, catastrophizing and disordered quality of life measures [23]. Psychosocial testing of women prospectively treated for endometriosis was shown to have a reduced probability of improvement in the presence of nulliparity and catastrophizing [24], [25]. Lower quality of life scores among women with chronic pelvic pain were shown to correlate directly with pain scores and there was no added impact of a diagnosis of endometriosis [26]. Women with chronic pelvic pain and endometriosis were commonly shown to have pain sensitization in association with elevated levels of anxiety and depression [20]. Anxiety and reduced coping skills have been shown to be associated with women with endometriosis with disorders of the hypothalamic pituitary adrenal axis [27]. Women with persistent pain after surgery for endometriosis were found to be younger and higher levels of catastrophizing [21].

The specific purpose of this study was to explore the change in pre- and post-operative psychosocial tests among women having operative laparoscopy for non-acute pain, determine if the tests correlated with one another and if these changes were sensitive to the presence of sensitization. Non-acute pain referred to women requiring surgical investigation or treatment that have not developed persistent chronic pain.

2 Methods

The study was done at Foothills Hospital, a regional tertiary center in a clinic specifically directed to the diagnosis and management of gynecological pain. The study was done between June 27, 2010 and June 30, 2012. The details of this study have been previously reported indicating the variables associated with the prediction of postoperative pain [19]. It was a prospective longitudinal cohort study comprising 16 women having tubal ligations for contraception without non-acute pain and 61 women having operative laparoscopies to evaluate and treat non-acute pain. Women were eligible to enter the study between the ages of 18 and 50 who either had requested a sterilization procedure or had sufficient pelvic pain to warrant investigation and treatment. Women with serious additional medical or psychological illnesses or pregnancy were excluded. All women were recruited and followed up by a study nurse assigned to the clinic. Follow-up at a 6 month clinic visit was arranged by the study nurse. Attempts to complete follow-up were undertaken by telephone, email and in person and where required the questionnaires were completed verbally on the telephone.

Women had psychosocial tests of distress (McGill Pain Score (SF-MPQ) [15], [16], the CES-D depression scale (CES-D) [28], the Pain Disability Index (PDI) [29] and the Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS) [30] and tests of sensitization (cutaneous allodynia) before and 6 months following surgery for non-acute pain. Average reported pain for the past week was recorded on a 0–10 numeric scale. The assessment of pain sensitization was based on the presence or absence of cutaneous allodynia on the lower abdomen [17], [20]. Briefly the test consists of a cotton tipped applicator drawn down the abdomen initially in the mid clavicular line while the patient is asked if there is a sudden change in the sensation or a painful experience. The area is tested bilaterally and the direction is modified so that principally the region of T 12 and L1 dermatomes are evaluated. This test has been shown to be significantly associated with the presence of previous or contemporaneous visceral pelvic disease [14]. A sample of 60 women with measurements before and after surgery would have >80% power to detect a medium effect size of 0.5 standard deviations of change in subjective pain level ratings, assuming α=0.05. For example, if the standard deviation of the difference in pain level was 3, then 60 women would allow us to detect a 1.5-point change in pain levels, with α=0.05 and power >0.80. A convenience sample of a second group of 16 women who underwent tubal ligation was included to explore whether laparoscopy induced a painful postoperative response in women without preoperative pain.

The study received renewal ethics approval from the University of Calgary Conjoint Medical Ethics Committee (REB15-1178 REN3). All subjects provided written informed consent after ethics approval was granted.

The differences in baseline scores between groups were compared using the Mann-Whitney U-test and 95% confidence intervals for the Hodges-Lehmann estimation of median differences were reported. Differences in change in scores from baseline to 6 months postoperatively were assessed using the paired t-test. The relationship of these tests in relation to themselves and to the average pain reported at baseline and change in scores of tests was assessed by Spearman and Pearson correlation coefficient analysis. The effect size of the difference in scores was calculated with Cohen’s d [31], [32]. Missing values were considered missing completely at random and were excluded from the analysis.

3 Results

The demographics of the subjects in the study have been previously reported [19]. The number of individuals with missing data for each of the tests is presented in the accompanying tables (Tables 1–3).

Comparison of sensitization, average pain, and psychosocial tests at baseline between the tubal ligation and non-acute pain groups.

| Tubal ligation (n=16) | Non-acute pain (n=61) | Risk difference or median differenceb (95% CI) | p-Valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitization | 2 (12.5%) | 31 (52.5%) | 40.0% (19.4%–60.7%) |

0.004 |

| Average pain, median (IQR) | 0.5 (3.25) (missing=4) |

5 (3) (missing=2) |

4 (2–5) |

<0.001 |

| CESD score, median (IQR) | 12.5 (13) | 19.5 (22) (missing=1) |

7 (0–14) |

0.071 |

| PCS score, median (IQR) | 8 (18) (missing=2) |

22 (24) (missing=4) |

12 (5–20) |

0.002 |

| PDI score, median (IQR) | 1 (3) (missing=2) |

36 (24) (missing=2) |

32 (21–39) |

<0.001 |

| SFMPQ score, median (IQR) | 0.2 (0.3) (missing=2) |

2.7 (3.2) (missing=3) |

2 (1–3) |

<0.001 |

-

a χ 2-test comparing proportion sensitized; Mann-Whitney U-test comparing the two groups for all other variables. bRisk difference (95% confidence interval) between groups for sensitization; Hodges-Lehmann estimation of median difference (95% confidence interval) between groups for all others.

Correlation of psychosocial tests with average pain level at baseline.

| Baseline CESD | Baseline PCS | Baseline PDI | Baseline SFMPS | Baseline average pain | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline CESD | |||||

| r | 1 | 0.587 | 0.381 | 0.474 | 0.322 |

| 95% CI | 0.406–0.719 | 0.163–0.560 | 0.269–0.634 | 0.093–0.514 | |

| Sig | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.006 | |

| n | 76 | 71 | 73 | 72 | 71 |

| Baseline PCS | |||||

| r | 0.587 | 1 | 0.592 | 0.547 | 0.463 |

| 95% CI | 0.406–0.719 | 0.410–0.725 | 0.352–0.691 | 0.248–0.631 | |

| Sig | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| n | 71 | 71 | 69 | 69 | 67 |

| Baseline PDI | |||||

| r | 0.381 | 0.592 | 1 | 0.745 | 0.621 |

| 95% CI | 0.163–0.560 | 0.410–0.725 | 0.615–0.832 | 0.445–0.746 | |

| Sig | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| n | 73 | 69 | 73 | 70 | 68 |

| Baseline SFMPQ | |||||

| r | 0.474 | 0.547 | 0.745 | 1 | 0.709 |

| 95% CI | 0.269–0.634 | 0.352–0.691 | 0.615–0.832 | 0.561–0.809 | |

| Sig | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| n | 72 | 69 | 70 | 72 | 67 |

| Baseline average pain | |||||

| r | 0.322 | 0.463 | 0.621 | 0.709 | 1 |

| 95% CI | 0.093–0.514 | 0.248–0.631 | 0.445–0.746 | 0.561–0.809 | |

| Sig | 0.002 | 0.003 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| n | 71 | 67 | 68 | 67 | 71 |

-

Spearman correlation coefficients.

Correlation of changes to psychosocial test scores after 6 months.

| Change CESD | Change PCS | Change PDI | Change SFMPQ | Change average pain | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Change CESD | |||||

| r | 1 | 0.184 | 0.501 | 0.421 | 0.446 |

| 95% CI | −0.073 to 0.415 | 0.281–0.666 | 0.187–0.604 | 0.209–0.630 | |

| Sig | 0.156 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.000 | |

| n | 66 | 61 | 61 | 62 | 58 |

| Change PCS | |||||

| r | 0.184 | 1 | –0.036 | 0.189 | –0.086 |

| 95% CI | –0.073 to 0.415 | –0.293 to 0.227 | –0.075 to 0.425 | –0.343 to 0.184 | |

| Sig | 0.156 | 0.792 | 0.156 | 0.532 | |

| n | 61 | 62 | 57 | 58 | 55 |

| Change PDI | |||||

| r | 0.501 | –0.036 | 1 | 0.492 | 0.478 |

| 95% CI | 0.281–0.666 | –0.293 to 0.227 | 0.266–0.662 | 0.244–0.654 | |

| Sig | 0.000 | 0.792 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| n | 61 | 57 | 65 | 59 | 57 |

| Change SFMPQ | |||||

| r | 0.421 | 0.189 | 0.492 | 1 | 0.611 |

| 95% CI | 0.187–0.604 | –0.075 to 0.425 | 0.266–0.662 | 0.410–0.751 | |

| Sig | 0.001 | 0.156 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| n | 62 | 58 | 59 | 63 | 56 |

| Change average pain | |||||

| r | 0.446 | –0.086 | 0.478 | 0.611 | 1 |

| 95% CI | 0.209–0.630 | –0.343 to 0.184 | 0.244–0.654 | 0.410–0.751 | |

| Sig | 0.000 | 0.532 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| n | 58 | 55 | 57 | 56 | 64 |

-

Pearson correlation coefficients.

3.1 Surgical procedures

The procedures included tubal ligation (n=16), laparoscopic hysterectomy (n=5), endometriosis procedures (excision and cautery) (n=21), adnexal procedures (salpingectomy, cystectomy, oophorectomy, salpingo-oophorectomy) (n=30), adhesion procedures (n=13). Of the total procedures reported 53.1% had one procedure, 34.7% had two procedures, 10.2% had three procedures and 2.0% had four procedures in the same operation.

3.2 Surgery effects

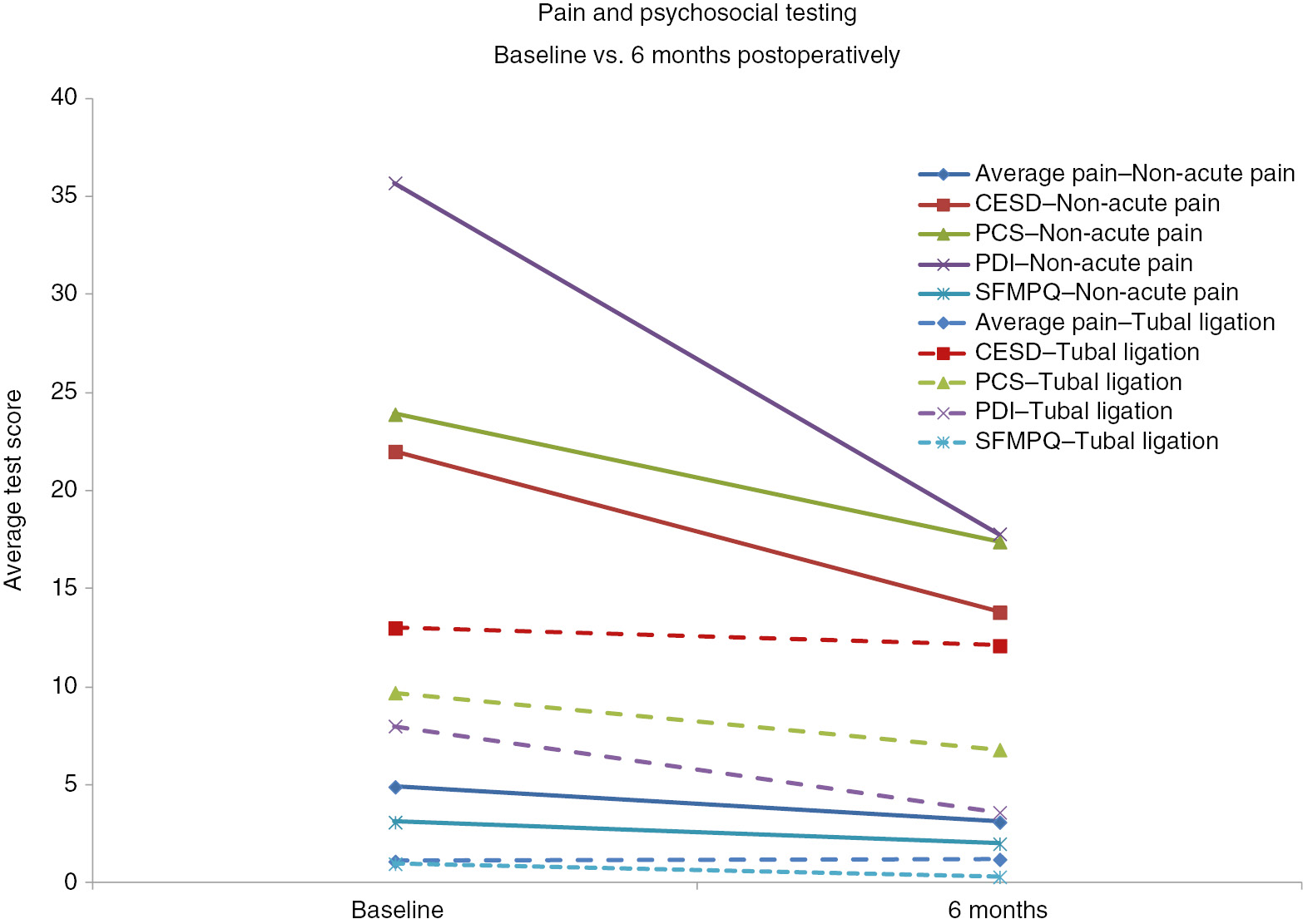

Laparoscopic surgery in the entire cohort significantly reduced average pain (p<0.001) and all tests of psychosocial distress; CESD (p<0.001), PCS (p=0.001), PDI (p<0.001), SFMPQ (p<0.001) (Fig. 1). These differences were significant for all tests when the comparisons were done on women having surgery for non-acute pain. Of these women, 33 women, 43% of the entire cohort was found to be sensitized (Table 1). Women having laparoscopic surgery for non-acute pain had significantly greater average pain levels (median 5, IQR 3 vs. median 0.5, IQR 3.25) and rates of sensitization [31 (52.5%) vs. 2 (12.5%)] than women having surgery for a tubal ligation (p<0.001) (Table 1).

Comparison of pre- and postoperative average pain and psychosocial scores among all women having operative laparoscopic surgery. All tests differ at p<0.001 excepts PCS – p=0.001.

3.3 Baseline and 6 month tests

The baseline psychosocial tests correlated significantly with baseline average pain (Table 2). The baseline test scores of psychosocial tests indicated greater distress among women with an indication for surgery related to non-acute pain than tubal ligation: average pain (p<0.001), PCS (p=0.002), PDI (p<0.001) and SFMPQ (p<0.001) (Table 1). At 6 months all tests of psychosocial distress correlated significantly with changes in average pain with the exception of catastrophizing (Table 3).

3.4 Sensitization effects

At baseline pain sensitization was associated with greater pain and distress scores in the entire cohort: average pain (p=0.004), CES-D (p=0.055), PCS (p=0.011), PDI (p=0.003) and SFMPQ (p=0.017) (Table 3). The pattern was similar for those having surgery for non-acute pain (Fig. 2).

Baseline psychosocial test scores of women having pelvic laparoscopic surgery: association with pain sensitization.

3.5 General results

There was no difference in sensitization rates among those who had previous pelvic surgery or hysterectomy. The rates of sensitization and durations of pain were similar for women experiencing cyclic, sporadic, intermittent and continuous pain. In terms of pain duration, only the CESD indicated a relationship between the duration of pain and change in scoring at 6 months (p<0.025). Women who had pain for less than 5 years had a greater reduction in the CESD score (p<0.004) while there was no effect of duration of pain on the other tests. There were no differences in the use of anti-depressants, anti-inflammatory drugs, opiates or hormonal medication between those with and without sensitization.

4 Discussion

This study indicated laparoscopic surgery involving visceral trauma resulted in a reduction in average reported pain and all tests of psychosocial tests. When the indication for surgery was non-acute pain the pattern of change was less dramatic; differences were significant for changes in average pain and PDI although the trend was similar for the other tests [32]. In terms of achieving minimally clinically significant changes, the results appeared to favor the PDI [15] while falling short for Pain Catastrophizing [16] and Short Form McGill Pain [28], [29] score. The subjects appeared to have sub-depression threshold values on the CES-D test [30].

There were significant correlations of baseline pain and psychological measures of distress pre-operatively. Women having surgery for pain had greater measures of distress than those having a tubal ligation indicating the importance of pre-operative pain in assessing psychological distress [33].

The rate of pain sensitization was greater among those having surgery for non-acute visceral source of pain than women having tubal ligations [34]. The presence of sensitization was associated with trends to greater baseline and 6 month postoperative changes in average pain and measures of psychological distress. These were statistically significant when the entire cohort was considered. The close correlation of average pain and tests of psychological distress continued after surgery as has been reported in other postoperative studies [21], [35].

The objective of the surgery in women with non-acute pain was to reduce visceral pain. This differs from much of the literature on CPSP in several ways. First, the target is visceral tissues. Second, the criteria originally proposed by Macrae, as recently modified for ICD-11 still excludes of other possible causes for the pain [11], [36]. This criterion is difficult to meet in relation to gynecological literature as many women suffer from recurrent disease processes, particularly endometriosis [19], [37]. Further, women can undergo surgery for conditions that have initiated pain sensitization that remains after the operation has been undertaken.

The limitations of the study include the modest sample size and missing data due to loss to follow-up at 6 months or incomplete questionnaires at baseline or 6 months. As this was exploratory secondary analysis of existing data [19], the sample size was not powered to compare the tubal ligation and non-acute pain group nor the impact of sensitization within each group. Although missing data was treated as missing completely at random, we had no way of knowing whether this was truly the case.

In summary, psychosocial testing correlated well with reductions in average pain pre- and postoperatively. Women having surgery for pre-existing pain had greater degrees of distress than those having surgery for non-acute pain. When all subjects were considered, baseline and postoperative average pain correlated significantly with tests of psychosocial distress. Also when all subjects were considered, women with pain sensitization had significant decreases in average pain and pain disability although all tests showed a similar trend. Incorporation of these tests in the pre- and postoperative evaluation of women having laparoscopic surgery provide a broader understanding of the woman’s pain experience.

-

Authors’ statements

-

Research funding: Supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Ottawa, Canada (Grant Funding no. 102816).

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Informed consent: All subjects provided written informed consent after ethics approval was granted.

-

Ethical approval: The study received renewal ethics approval from the University of Calgary Conjoint Medical Ethics Committee (REB15-1178 REN3).

References

[1] Howard FM. The role of laparoscopy as a diagnostic tool in chronic pelvic pain. Baillieres Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2000;14:467–94.10.1053/beog.1999.0086Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[2] Baekelandt J, De Mulder PA, Le Roy I, Mathieu C, Laenen A, Enzlin P, Weyers S, Mol BW, Bosteels JJ. Postoperative outcomes and quality of life following hysterectomy by natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery (NOTES) compared to laparoscopy in women with a non-prolapsed uterus and benign gynaecological disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2017;208:6–15.10.1016/j.ejogrb.2016.10.044Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[3] Rosati M, Bramante S, Conti F. A review on the role of laparoscopic sacrocervicopexy. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 2014;26:281–9.10.1097/GCO.0000000000000079Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[4] Bennich G, Rudnicki M, Lassen PD. Laparoscopic surgery for early endometrial cancer. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2016;95:894–900.10.1111/aogs.12908Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[5] Candiani M, Izzo S, Bulfoni A, Riparini J, Ronzoni S, Marconi A. Laparoscopic vs vaginal hysterectomy for benign pathology. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2009;200:368.e1–7.10.1016/j.ajog.2008.09.016Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] Jacobson TZ, Duffy JM, Barlow D, Koninckx PR, Garry R. Laparoscopic surgery for pelvic pain associated with endometriosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009:CD001300.10.1002/14651858.CD001300.pub2Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[7] Cibula D, Kuzel D, Fucikova Z, Svabik K, Zivny J. Acute exacerbation of recurrent pelvic inflammatory disease. Laparoscopic findings in 141 women with a clinical diagnosis. J Reprod Med 2001;46:49–53.10.1097/00006254-200105000-00017Search in Google Scholar

[8] Uncu G, Kimya Y, Bilgin T, Ozan H, Tufekci M. Laparoscopic treatment of benign adnexial cysts. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol 1997;24:98–100.Search in Google Scholar

[9] Lavand’Homme P. Transition form acute to chronic pain after surgery. Pain 20177;158:S50–4.10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000809Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] Woolf CJ. Central sensitization: implications for the diagnosis and treatment of pain. Pain 2011;152(3 Suppl):S2–15.10.1016/j.pain.2010.09.030Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[11] Treede RD, Rief W, Barke A, Aziz Q, Bennet M, Bencliel R, Cohen M, Evers S, Finnerup NB, First MB, Giamberardino MA, Kaasa S, Kosek E, Lavand’homme P, Nicholas M, Perrot S, Scholz J, Schug S, Smith BH, Svensson P, et al. A Classification of Chronic Pain For ICD-11. Pain 2015;158:1003–7.10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000160Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[12] IASP. International Society for the Study of Pain 2016. Available at: http://www.iasp-pain.org/Taxonomy-Sensitization.Accessed on December 14, 2017.Search in Google Scholar

[13] Latremoliere A, Woolf CJ. Central sensitization: a generator of pain hypersensitivity by central neural plasticity. J Pain 2009;10:895–926.10.1016/j.jpain.2009.06.012Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[14] Jarrell J, Giamberardino MA, Robert M, Nasr-Esfahani M. Bedside testing for chronic pelvic pain: discriminating visceral from somatic pain. Pain Res Treat 2011;2011:692102.10.1155/2011/692102Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[15] Soer R, Reneman MF, Vroomen PC, Stegeman P, Coppes MH. Responsiveness minima; clinically important change in Pain Disability Index in patients with chronic back pain. Spine 2012;37:711–5.10.1097/BRS.0b013e31822c8a7aSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[16] Scott W, Wideman TH, Sullivan MJ. Clinically meaningful scores on pain catastrophizing before and after multidisciplinary rehabilitation: a prospective study of indiviual with subacute pain after whiplash. Clin J Pain 2014;30:183–90.10.1097/AJP.0b013e31828eee6cSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[17] Brandsborg B. Pain following hysterectomy: epidemiological and clinical aspects. Dan Med J. 2012;59:B4374.Search in Google Scholar

[18] Rudin A, Wolner-Hanssen P, Hellbom M, Werner MU. Prediction of post-operative pain after a laparoscopic tubal ligation procedure. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2008;52:938–45.10.1111/j.1399-6576.2008.01641.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[19] Jarrell J, Ross S, Robert M, Wood S, Tang S, Stephanson K, Giamberardino MA. Prediction of postoperative pain after gynecologic laparoscopy for nonacute pelvic pain. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2014;211:360–8.10.1016/j.ajog.2014.04.010Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[20] Stratton P, Khachikyan I, Sinaii N, Ortiz R, Shaw J. Association of chronic pelvic pain and endometriosis with signs of sensitization and myofascial pain. Obstet Gynecol 2015;125:719–28.10.1097/AOG.0000000000000663Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[21] Carey ET, Martin CE, Siedhoff MT, Bair ED, As-Sanie S. Biopsychosocial correlates of persistent postsurgical pain in women with endometriosis. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2014;124:169–73.10.1016/j.ijgo.2013.07.033Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[22] Yosef A, Allaire C, Williams C, Ahmed AG, Al-Hussaini T, Abdella MS. Multifactorial contributors to the severity of chronic pelvic pain in women. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2016;215:760.10.1016/j.ajog.2016.07.023Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[23] Bryant C, Cockburn R, Plante AF, Chia A. The psychological profile of women presenting to a multidisciplinary clinic for chronic pelvic pain: high levels of psychological dysfunction and implications for practice. J Pain Res 2016;9:1049–56.10.2147/JPR.S115065Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[24] Martinez B, Canser E, Gredilla E, Alonso E, Gilsanz F. Management of patients with chronic pelvic pain associated with endometriosis refractory to conventional treatment. Pain Pract 2013;13:53–8.10.1111/j.1533-2500.2012.00559.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[25] Martin CE, Johnson E, Wechter ME, Leserman J, Zolnoun DA. Catastrophizing: a predictor of persistent pain among women with endometriosis at 1 year. Hum Reprod 2011;26:3078–84.10.1093/humrep/der292Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[26] Souza CA, Oliveira LM, Scheffel C, Genro VK, Rosa V, Chaves MF, Cunha Filho JS. Quality of life associated to chronic pelvic pain is independent of endometriosis diagnosis–a cross-sectional survey. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2011;9:41.10.1186/1477-7525-9-41Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[27] Quinones M, Urrutia R, Torres-Reveron A, Vincent K, Flores I. Anxiety, coping skills and hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis in patients with endometriosis. J Reprod Biol Health 2015;3:2.10.7243/2054-0841-3-2Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[28] https://www.sralab.org/rehabilitation-measures/mcgill-pain-questionnaire-short-form.Search in Google Scholar

[29] Hawker GA, Mian S, Kendzerska T, French M. Measures of Pathology and Symptoms: Measures of adult pain: Visual Analog Scale for Pain (VAS Pain), Numeric Rating Scale for Pain (NRS Pain), McGill Pain Questionnaire (MPQ), Short-Form McGill Pain Questionnaire (SF-MPQ), Chronic Pain Grade Scale (CPGS), Short Form-36 Bodily Pain Scale (SF-36 BPS), and Measure of Intermittent and Constant Osteoarthritis Pain (ICOAP). Arthritis Care Res 2011;S11:S240–52.10.1002/acr.20543Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[30] Raad J. Rehab Measures: Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D). 2013.Search in Google Scholar

[31] Coe R. Its The Effect Size, Stupid. What effects size is and why it is important. 1–13. 2017. https://www.leeds.ac.uk/educol/documents/00002182.htm.Search in Google Scholar

[32] Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. New York: Academic Press, 1969.Search in Google Scholar

[33] Hernandez C, Diaz-Heredia J, Berraquero ML, Crespo P, Loza E, Ruiz Iban MA. Pre-operative predictive factors of post-operative pain in patients with hip or knee arthroplasty: a systematic review. Reumatol Clin 2015;11:361–80.10.1016/j.reumae.2014.12.011Search in Google Scholar

[34] Aredo JV, Heyrana KJ, Karp BI, Shah JP, Stratton P. Relating Chronic pelvic pain and endometriosis to signs of sensitization and myofascial pain and dysfunction. Semin Reprod Med 2017;35:88–97.10.1055/s-0036-1597123Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[35] Hinrichs-Rocker A, Schulz K, Jarvinen I, Lefering R, Simanski C, Neugebauer EA. Psychosocial predictors and correlates for chronic post-surgical pain (CPSP) – a systematic review. Eur J Pain 2009;13:719–30.10.1016/j.ejpain.2008.07.015Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[36] Crombie IK, Davies HT, Macrae WA. Cut and thrust: antecedent surgery and trauma among patients attending a chronic pain clinic. Pain 1998;76:167–71.10.1016/S0304-3959(98)00038-4Search in Google Scholar

[37] Browne HN, Sherry R, Stratton P. Obturator hernia as a cause of recurrent pain in a patient with previously diagnosed endometriosis. Fertil Steril 2008;89:962–3.10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.07.1381Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

©2018 Scandinavian Association for the Study of Pain. Published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston. All rights reserved.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Good news in the new year – New publisher of the PubMed-indexed Scandinavian Journal of Pain

- Systematic review

- Efficacy and safety of epidural, continuous perineural infusion and adjuvant analgesics for acute postoperative pain after major limb amputation – a systematic review

- Clinical pain research

- Low dose ketamine versus morphine for acute severe vaso occlusive pain in children: a randomized controlled trial

- Mycophenolate for persistent complex regional pain syndrome, a parallel, open, randomised, proof of concept trial

- Observational study

- What are the similarities and differences between healthy people with and without pain?

- Pain, psychosocial tests, pain sensitization and laparoscopic pelvic surgery

- Psychosocial factors partially mediate the relationship between mechanical hyperalgesia and self-reported pain

- Physical activity during work and leisure show contrasting associations with fear-avoidance beliefs: cross-sectional study among more than 10,000 wage earners of the general working population

- Cognitive behavioral therapy for irritable bowel syndrome: the effects on state and trait anxiety and the autonomic nervous system during induced rectal distensions – An uncontrolled trial

- Original experimental

- The MMP9 rs17576 A>G polymorphism is associated with increased lumbopelvic pain-intensity in pregnant women

- The validity of pain intensity measures: what do the NRS, VAS, VRS, and FPS-R measure?

- Effects of activity interruptions by pain on pattern of activity performance – an experimental investigation

- Educational case report

- A case report of a thalamic stroke associated with sudden disappearance of severe chronic low back pain

- Repetitive nerve block for neuropathic pain management: a case report

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Good news in the new year – New publisher of the PubMed-indexed Scandinavian Journal of Pain

- Systematic review

- Efficacy and safety of epidural, continuous perineural infusion and adjuvant analgesics for acute postoperative pain after major limb amputation – a systematic review

- Clinical pain research

- Low dose ketamine versus morphine for acute severe vaso occlusive pain in children: a randomized controlled trial

- Mycophenolate for persistent complex regional pain syndrome, a parallel, open, randomised, proof of concept trial

- Observational study

- What are the similarities and differences between healthy people with and without pain?

- Pain, psychosocial tests, pain sensitization and laparoscopic pelvic surgery

- Psychosocial factors partially mediate the relationship between mechanical hyperalgesia and self-reported pain

- Physical activity during work and leisure show contrasting associations with fear-avoidance beliefs: cross-sectional study among more than 10,000 wage earners of the general working population

- Cognitive behavioral therapy for irritable bowel syndrome: the effects on state and trait anxiety and the autonomic nervous system during induced rectal distensions – An uncontrolled trial

- Original experimental

- The MMP9 rs17576 A>G polymorphism is associated with increased lumbopelvic pain-intensity in pregnant women

- The validity of pain intensity measures: what do the NRS, VAS, VRS, and FPS-R measure?

- Effects of activity interruptions by pain on pattern of activity performance – an experimental investigation

- Educational case report

- A case report of a thalamic stroke associated with sudden disappearance of severe chronic low back pain

- Repetitive nerve block for neuropathic pain management: a case report