Abstract

Evaluation of other cultures is a strong force in a culture’s definition of itself. Cultures are formed in encounters that include domination, conflict, and dismissal as much as appreciation and smooth exchange. In this paper, the construction of cultural identity is discussed, with reference to a Scandinavian Theme Park proposal made in cooperation between American design consultants and a local Swedish team of planners and visionaries. The image production in this design proposal, which never came to be realised in architectural production, shows that “Scandinavia” appears as a two-some dialogic construction that adopts stereotyped cultural identities, and that it was not brought to any wider public dialogue. In a semiotic account of this architectural decision-making, models of culture (Lotman. 1990. Universe of the mind: A semiotic theory of culture. London: Tauris.) are discussed in terms of the tripartition of culture into Ego-culture, Alter-culture and Alius-culture (Sonesson. 2000. Ego meets alter: The meaning of otherness in cultural semiotics. Semiotica 128(3/4). 537–559.; Cabak Rédei, Anna. 2007. An inquiry into cultural semiotics: Germaine de Staël’s autobiographical travel accounts. Lund: Lund University Press.), considered as a basic abstracted backdrop of what is meant by cultural difference. In this paper it is suggested that this tripartite view on culture, can be further discussed in reflection of post-colonial studies, notably through terms such as “mimicry” (Bhabha. 1984. Of mimicry and man: The ambivalence of colonial discourse. October 28. 125–133.) and “subalterity” (Spivak. 1988. Can the subaltern speak?. In Cary Nelson & Lawrence Grossberg (eds.), Marxism and the interpretation of culture, 271–313. Urbana & Chicago: University of Illinois Press.). The model of culture can furthermore be discussed through Peirce’s distinction between different stages and carriers of representation, adding to the cultural model an understanding of what it means, over time, for a culture to relate to an admired as well as to a neglected other cultural actor.

1 Introduction: Cultural encounters and their parties

Cultures can be seen as being formed in encounters that include domination, conflict, and dismissal as much as equality, appreciation and smooth exchange. The fact that encounters and exchange – rather than containment or essence – are seen as matters worthy of study provides us with theories that highlight reciprocity and mutual evaluation between two main parties, but also, as will be of interest here, take third parties into account, parties that play their role as being the unwanted, or neglected. Jurij Lotman (1985, 1990) discusses how certain foreign cultures may work as role models, and others not, when a home culture reflects on itself or attempts to upgrade itself. This thought, based in cultural preference and exclusion, inevitably forces the binary view of “them” and “us” into a tripartite matter of concern, made even more explicit in Sonesson (2000) and Cabak Rédei (2007). The modelling of cultural semiotics, based in Lotman’s (1990) basic idea of a culture incorporating other cultures’ ideas into its sphere, and further explicated in its parts by Sonesson (2000) and Cabak Rédei (2007) encompasses a tripartite basic relationship: an Ego-culture which turns a friendly, perhaps even admiring, eye towards an Alter-culture, at the same time as disregarding other Alius-cultures as not even worthy of consideration.

This semiotic view of culture also happens to share with post-colonial studies a concern with cultural traits as being conditioned by relations between cultures. Cultural exchange can be described as offering an explanation of how appreciation, but also conflict, and dismissal appear at the turns of geographical history, and more generally, of the way affective and value-based mutual regard of one another epitomize the actual decisive forces of what we call culture. Views from post-colonial discourse on cultural encounters, such as those of Bhabha (1984) and Spivak (1988), foregrounded what could be called the uneven reciprocities of culture, showing how mutual dependence may constitute on the one hand a working cultural relationship but also, on the other, create unfavourable conditions for less noticeable parties involved. These theories also point to the tactics needed to keep a situated culture together. To (pretend to) do as the other – as in “mimicry” (Bhabha 1984) – or to not (be able to) take part in the culture where one rightfully belongs – as in “subalterity” (Spivak 1988) – are two facets of cultural formation that imply that more than merely two positions (dominant, dominated) are needed to define a common culture, or a common view of a culture. Geographical controversy or unholy circumstances of dominance are often mediated primarily as an issue between an offender and offended, as in the case of a colonizer and a colonized, but as was articulated through Spivak’s (1988) text on subalterity, the cultural contract is actually, at least, tripartite, consisting of: a colonizing tradition, a local tradition, and the voiceless victim of the unholy merging of these traditions. In Spivak’s case the cultural tripartition was shown in light of how British colonization in India interfered with – i. e. opened up but also destroyed – ways at hand for locals to express their needs in authoritative cultural structures.

Both of these traditions, post-colonial theory and cultural semiotics, the first grounded in analyses of geo-political difference and the governance of culture, while the other aims to model the making of culture as exchange of meaning, have taken notions such as reciprocity, appreciation and disregard to be the main driving forces in how one culture is perceived by another. In what follows, I will discuss the tripartite semiotic model through some of the corner-stones of post-colonial theory and through a re-reading of Lotman’s view of otherness. In order to account for the temporality of cultural encounters, an interpretation of the Peircean sign categorisations and their dependence on time will also be added to the analysis. This will be made in reflection of the construal of culture in an architectural design vision of a theme park, proposing to represent Scandinavia.

When it comes to architecture and design – the empirical matter of this paper – reciprocal forces and cultural influences are usually present in the daily apparatus of design and architectural making: in dialogue, sketches and image-production that supports the envisioning of new environments. But this reciprocity in design dialogue is seldom analyzed in architectural theory as a matter of importance in itself, perhaps because it does not so much describe the final result, i. e. the house, the garden, or the city, but is rather located in the processes behind, and before, the effectuation of new places for human action. Sometimes, however, the production of “culture” is also the explicit objective in design, such as when local heritage is brought to the aesthetic front, or when a new museum or concert hall is supposed to be a contemporary representation of the culture it is located within. In the case addressed here, a proposed Scandinavian Theme Park, envisioned as located in Malmö close to the bridge to Copenhagen, “culture” is very much an explicit design task. This theme park vision was produced and sketched collaboratively by Swedish planning authorities and globally working American design consultants, starting in 2002. The park idea existed as a projective possibility, discussed for more than ten years, but the project was eventually dropped in 2013, when future management of the park could not be secured. The preliminary proposals and sketches of attractions reveal that American (or rather USA-based) culture is conveyed through a promise of robust amusement design, while Scandinavian culture is represented by images of Vikings and other Nordic stereotypes. The images serve in the forthcoming analysis to ask what it means to visually construe a culture. As we shall see, the images produced in this cross-cultural dialogue reflect more than one type of visual production of “otherness.”

2 The visualization of a region: Scandinavia

The idea of a future theme park to be located in Malmö, Sweden, started to appear in planning documents and the local press in 2002, and after a couple of years of developing the first sketches, the estimation was that the park would open its doors to the public in 2014. Several images supported the visionary work, but were not shown officially, until a first visual rendering of the idea appeared in public media, in the local daily paper Sydsvenskan (Ljungberg 2008). This image showed a bright and colorful visualization in a bird’s-eye view of an amusement area to be located in the flat agrarian landscape outside Malmö, carrying a set of attractions in a style of rendering reminiscent of cartoonist phantasy worlds (Figure 1).

Image labelled “Birds-eye” in the Scandinavian theme park promotion material (Publication rights accorded by the holder of the copyright, Eksploria Edutainment, April 2017).

One of the images discussed among the Malmö-based visionaries and the consultants from USA depicted the future entrance with moving structures reminiscent of giant ice blocks, representing the idea that in Scandinavian countries snow and ice is a matter of the everyday, a myth that in reality would appear quite absurd to Scandinavians (unless perhaps for the Sami population living in the very northern parts with cold climate conditions and few sun hours during winter months), and particularly so to inhabitants of Malmö, situated almost at the extreme south of Sweden, where snow is very rare. This image was labelled “Malmö Entry” in the promotion material, and the Nordic Mythology was represented by the name “Yggdrasil” placed on a giant moving ice-like entry sign (Figure 2):

Image labelled “Malmö Entry” in the promotion material (Publication rights accorded by the holder of the copyright, Eksploria Edutainment, April 2017).

The first proposed “attraction” meeting a visitor after having entered the park was named after Yggdrasil, and this name was also during the years 2009–2012 tested as the main title of the park itself. Yggdrasil, being the life tree in Nordic mythology, is reminiscent of life tree symbols in other early cultures, and it was highlighted in the proposal as symbolizing wisdom and knowledge.

In several of the promotion images (as seen in Figures 2, 3 and 4), the Yggdrasil tree is given a position as a landmark in the amusement park scenery. The identity and shaping of theme park landforms like artificial hills and mountains, including specifically designed “ride landscapes” (Brown 2002) through which visitors are taken by small boats or rail-based vehicles, is surprisingly conventional in the proposal, in that they follow a theme park aesthetics emanating from the European garden parks from primarily eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, then used in the early amusement parks in USA in the beginning of twentieth century, which later developed into the modern Disney theme parks (Brown 2002: 246). In the Scandinavian theme park proposal in Malmö the artificial landscape literally took a departure from, and physically circulated around, the Yggdrasil tree, as a visible reminder of a Nordic myth.

Visualizations of the Yggdrasil tree attraction, including a hill with glass and water formations (Publication rights accorded by the holder of the copyright, Eksploria Edutainment, April 2017).

Visualization in the design proposal of a maze concept with the Yggdrasil tree in the background (Publication rights accorded by the holder of the copyright, Eksploria Edutainment, April 2017).

Modern fictionalized depictions of Yggdrasil are often, as in this proposal, given a neo-gothic, quasi-realistic phantasy style, while historically early depictions, like the tapestry of Överhogdal (Figure 5), made btw 800 and 1100 AD and recognized in archaeology and in the history of textiles as conveying a visualization of the story of Yggdrasil, are rarely seen in popular contexts. Such iconography could in principle lend itself to other, and wider ranges of visual representations, and other life world symbolic systems, thus activating a more profound base of cultural exchange (cf. Sinha 2011: 98).

Overhogdal tapestry, fragment (Jamtli Museum, public image).

Existing visual heritage did not appear in the project’s promotion material, which was instead more devoted to what we might call cinematic effects, or Universal Studio-aesthetics. So was also the next main theme of the park, namely the obligatory Scandinavian Vikings, recalling an already existing popular imagery, often appearing in touristic events and in souvenir aesthetics. Here, the Vikings were staged as part of motion-based attractions (Figures 6 and 7).

“Viking” theme park attraction (Publication rights accorded by the holder of the copyright, Eksploria Edutainment, April 2017).

“Gods and Heroes,” one of the theme park attractions (Publication rights accorded by the holder of the copyright, Eksploria Edutainment, April 2017).

In what seems like an attempt to relate the Vikings to a larger, or general Nordic mythology, other promotion images depict phantasy-locations possible to visit, like large dark caves or indoor spaces. The historical fact that Vikings and Yggdrasil seem to have a connection did not however appear as an elaborated narrative in the visualizations or elsewhere in the promotion material.

Since the purpose of the park was, apart from amusement, also to be a place of education, interactive kinds of maps were proposed as places for exploration in the proposal’s visual material (Figure 8). This node of amusement differs substantially from the heritage stereotypes by bringing a more contemporary construal to the fabricated image of Scandinavia. Still, the aesthetics of the imagery is somewhat aligned with the rest, and as common in proposals like this, the mode of communication is a one-way presentation of possible future spaces but also of a corporate style. On the whole, not least in the verbally stated intentions by the American consultant (see chapter 4 below) the audience was supposed to be educated into a view. This type of “education” does not include any dialogic planning procedures (Healey 2007), where a potential audience would be asked what kind of views could be wished for. The notion of education was here in other words part of the disciplinary space of a management-oriented business culture, which is about as far as you can get from a view where the wills and needs of several groups steer the interest of learning (Wenger 1999), or where education takes the form of “subject-engagement” providing room for “life opportunities” (Spivak 2012: 131).

“Scandinavia Map” theme park attraction (Publication rights accorded by the holder of the copyright, Eksploria Edutainment, April 2017).

Some promotion images appear as reminiscent of fairy-tales or environmental settings (Figures 9 and 10). As regards their content, their constellation of figures and objects, and their colour schemes, they don’t seem to project any specifically Scandinavian culture, but could just as well be associated with other places, like for instance central Europe.

Fairy-tale based attraction (Publication rights accorded by the holder of the copyright, Eksploria Edutainment, April 2017).

Landscape and folklore-based attraction concept (Publication rights accorded by the holder of the copyright, Eksploria Edutainment, April 2017).

3 Emptiness in places and images

While some of the images in the promotion material depict proposed future attractions, others appear more as reflecting heritage, supposed to give a sense of the region. However, some images seem to aspire to give a more general impression of traditional landscapes and may recall for instance popular English, French or Italian castle garden representations. The style of most of the sketches have a touch of a Universal Studios kind of aesthetics, presenting situations set in motion by visitors as well as by the animatronic devices that usually show up in amusement parks. The promotion images overall convey a set of attractions densely populated, but at the same time give a generic impression of what could be called “placial emptiness.” Placial emptiness, or “non-place” was for a long-time part of what anthropologists saw as lack of “social facts” (Durkheim 1982 [1895]) in modern places. Such emptiness, it can be argued, is actually partly a disciplinary production of emptiness, created by anthropologists who do not see genuine social facts enough in new places, such as airports and shopping malls. A quite longstanding view (Relph 1976; Certeau 1984; Augé 1995 [1992]) seems to hesitate to acknowledge the fact that as soon as new places and new architectures are established, new activities are also brought about that start anchoring the place and create new placial meaning, even if that meaning is different from previous disciplinary comprehensions of what an ideal place should be (Sandin 2012; Lazzari 2012). The theme park proposal in Malmö showed a non-place anxiousness, in the sense that the vision, made to sell entertainment, convey an over-scrupulous urge to engage people, a kind of reverse emptiness as it were, expressed in the images through the urge to maximize architectural and population density. The emptiness present in these images is in other words due to the imagistic redundancy, but also to the elimination of ordinary everyday activities other than the compulsory amusement park behavior.

David Kolb (2008) points to the fact that every themed place has to be consciously and continuously maintained as such, thereby suggesting an anchoring in a lived reality beyond – or behind – the theme itself. There is, according to Kolb, always a reality acting to produce the theme, and this reality, we could say, is virtually lacking in design renderings. The general habit in architectural visualisation – of reducing away “unnecessary” stuff, or politically controversial matter, for the sake of keeping an undisturbed visionary focus – risks however, if we trust people’s ability to judge images, to become superficial to the extent that it also becomes unbeneficial for the project, because the viewer of the image may perceive the future place as too typified, too slick, or too ignorant of the lived world.

4 Stereotyping the region

The cultural construct in this case was as a joint venture between a Swedish group of visionaries close to the political leadership in Malmö, and the American design consultants BRC Imagination Arts and ERA (Economic Research Associates), specialists on amusement parks. The fact that images of the proposal represented an already existing theme park-oriented style of BRC’s was completely in line with the managerial strategy of ERA resulting in a list of possible sub-themes and attractions that were presented in the early plans, together with the City of Malmö: “Scandinavian Kingdom; Viking World; Five Worlds/Holy Wood; Human Factor/Fantastic Factory; World of the Car; Film/TV Studio Tour; Music/Music.” (ERA 2002). Also so-called “Other Attractions” were suggested in this document of the Municipality of Malmö, such as “Sky Tower; UN Plaza; Sculpture Park; World Train; International River” (ERA 2002). Both the images and the list of themes seem to emanate from the success of mid-twentieth century animation technologies originally made in relation to the Disney film industry. The visions and content of the images of the Scandinavian Theme Park proposal were however were produced in a dialogue between the American firms and the Swedish group of entrepreneurs, visionaries and politicians. A common cultural construction was made for the purpose of selling a concept about a region, and attracting an audience travelling from abroad. The local population of the region was not consulted, or heard, when the planning went on, or when the visions and images were created.

The amusement stereotypes were actually desired, conceptualized as the “familiar” and “well-known” (ERA 2002) qualities aimed at catching the interest of travelling visitors and possible financiers. On the whole, these depictions, like in vision statements in general, are not images made to present as true as possible a culture, not even as true as possible a representation of the actual future amusement environment, but they are ultimately made to promote a product by recalling fairly well-known figuration. They are, just as most visionary architectural imagery, and every depiction of an apartment for sale, made to arouse a certain desire. But the campaign in Malmö also had an objective to find examples with a typically Scandinavian figuration, and in accordance with the presumed commercial end objective, the campaign aimed for a well-known, even clichéd, cultural figuration, instead of for instance a less known, but perhaps researched heritage – which could have been another point of departure.

The concept presented in Malmö was perhaps already at the design table obsolete as regards what “amusement” connotes in a digital era dominated by fast and vast travelling of images and information. The fact that phantasy worlds with slight pedagogical intent, by the time this theme park idea was presented, had become a screen-oriented matter mainly experienced at home – first in the format of TV and video, then through internet and smart phones – rather than as a physical and theatrical public activity, was probably one of the main reasons why this themed environment never took root. Even if there has been a proliferation of parks globally in the decades since the digital and home-based amusement worlds saw the light, the balancing of the time factor in planning and its relation to change of societal needs, interests, technologies, etc., is of special importance in large scale theme park planning (Clavé 2007: 348–351). Conceptualized as late as in the early 2000s, the Malmö-based park proposal relied surprisingly much on classical types of rides and amusements.

Another reason might be that the main attractions, or sub-themes, namely Vikings and Nordic Mythology, were not original enough, or thoroughly enough researched, contextualized and staged in the proposals, to convince the common public and the companies targeted as co-financiers. It seemed like the visitor satisfaction prognosis made by ERA and the Swedish visionaries was too much focused on a general remote visitor, seen as “wanting to return” (ERA 2002) to the park. Research on visitor satisfaction and visitor attraction in relation to theme parks has pointed out that measurement scales cannot be automatically applied to visitors from different nations (cultures) (Joppe et al. 2001), nor can it be taken for granted that response style is the same regardless of culture (Dolnicar et al. 2008). These applied studies coincide with the idea in the semiotics of culture that the Ego-culture is the culture that defines the perspective through which other cultures are evaluated.

In the Malmö case the local visitors were not mentioned in their specificity and ethnical range in the preliminary descriptions in the same way as remote travelers. All in all, the local culture (in the region of Scandinavia) was treated as either fictionized clichés in the images, or as a neglected population in the negotiation about the idea of the park. The second part of this paper is devoted to an analysis of how a third party is represented in theories where one culture is seen in the light of another.

5 Mimicry, subalterity and cultural dependence

As mentioned in the beginning of this paper, cultural semiotics as we know it post-Lotman has drawn the attention to a third category in common with some postcolonial theory, despite the difference in scope, purpose and application. However, where the cultural semiotics (cf. Sonesson 2000) speaks of Alius as a non-recognized or detested culture, the post-colonial discourse dives more into the perspective of a third position and the possible consequences of an essentially incompatible, but still existing alliance between a dominating and a dominated culture. The basic figures of thought in early post-colonial theory concerned how essentially differing cultures (colonizer and colonized) are involved in a mutual, but uneven, sharing of interests, and writing of laws, and how an accepted silence, or forcefully silenced voices (Spivak 1988) become inescapable parts of the agreements or habits forming a daily living together. Forced (and sometimes fake) reciprocity as well as simulated likeness between members of differing cultures can be seen on the one hand as attempts to hide patterns of dominance (Bhabha 1984), but on the other, such mimicry also makes cultures, or individuals, get along on a daily basis, with the aim to avoid completely disrupting conflicts (or even cultural death). Even if these figures of thought emanate from severe ruler/ruled conditions and sometimes cruel upholding of cultural roles, they will here be seen as sufficiently casting light on our case of specifically architectural and tourist-oriented co-production of cultural image making. In all types of cultural encounter, initial unevenness in cultural deals, may cause further splitting of cultures (Bhabha 1984, Bhabha 2004). We can also remember that today all trading, not only that of design ideas, can be seen as part of what Bhabha (2004) in reflection of the artist Alan Sekula’s photographic work Fish Story calls “a containerized, computerized world of global trade,” where all those cultures that support trading inevitably also show how that support in itself also causes cultural discrimination and social hierarchization.

Mutual dependency is a decisive force in cultures’ definition of themselves. “Mimicry” (Bhabha 1984), or the tendency to repeat cultural behavior and artefacts, can on the one hand be seen as a desired will from a dominant culture, enacted to eliminate unproductive difference to the dominated culture. On the other hand, mimicry can, in this post-colonial context, also be a necessary counter-strategy on the part of a dominated culture to align itself to a certain degree with a dominating culture. Mimicry, seen in this way (Bhabha 1984), is “at once [an act of] resemblance and menace,” menace because mimicry, for Bhabha, means maintaining a difference which if becoming visible risks disrupting the agreed cultural relation. Mimicry, in the sense imitating through mere repetition the other’s behavior without representing the same original values and taste as the other, is not a straightforward communicational tool, but it is a mediation that works by retaining difference with a certain display of sameness. Any elimination of difference is essentially a semblance, since difference in such mutual situations paradoxically is the very fundament for co-existence (which is a basic idea also for Lotman 1990). Mimicry, says Bhabha (1984), is a matter of being “almost the same, but not really.” In the theme park negotiations, the Swedish negotiators wanted a professional, in this case American, appearance, or “look,” of the park, in order to be able to present locally an attractive proposal. The question that appears is then to what extent this desire led the Scandinavian part of the negotiation to also produce what was expected from another culture’s design process point of view.

Mimicry, whether we see it as a tactic to reach an advantage, or as less reflected behavior in learning situations, is possible only if you have the position to be part of the exchange deal. Some groups or individuals in societies, and as here, in design dialogue, are not even heard. And the subaltern – those who are not only other but moreover do not have opportunity to speak their voice (Spivak 1988), are in the contemporary land use and planning business a category that is actualized as soon as the designs are not aimed for the real users to take part in, but only concerns users as stereotyped economical figures invented to fit the ideas developed between the two main business interests. In our case the subalterns are the abstract and demographically defined visitors talked of, but also those omitted, in the interest of city branding and entertainment design.

In the Scandinavian Theme Park case subalterity was not only an effect of factual lack of user participation, but a subaltern category was also actively created already in the initial descriptions, formulated by ERA, when they – ironically in what they regard as an educational effort – try to induce their preferred feelings and response into the wills of potential users, announcing in public what the visitor wants. This kind of inducement is an intervention completely different from the kind of “subject-engagement” Spivak (2012) seeks in political-aesthetic activity.

6 Otherness in semiotic modelling of culture

Branches of cultural semiotics that see culture as a matter of exchange of values and information (Lotman 1990; Sonesson 2000) often take evaluation of another culture as a starting point, viewing appreciation as well as disregard for the other as main driving forces in how culture is perceived, modelled and construed. “Exchange” can be said to be a major conceptual base in much modern discourse, not least semiotics, and the reciprocity of exchange processes is a fundamental feature also of the notion of “semiosphere,” proposed by Jurij Lotman (1990). The idea of a semiosphere (containing known languages, behavior, concepts and values) is, despite a somewhat dichotomic (or border-line-based) first impression still a basic valid model for what happens in cultural interaction, when borders between cultures are violated and partially dismantled. Lotman (1990) also launched the idea that it is in the act of circulating a cultural product to other cultures, or extra-cultures, and getting it in return, that makes us see our own cultural act, and product, in a new light. Even if Lotman (1990) made this process known as auto-communication, or as activation of an I-I channel, a nomenclature that might lead to the thought that this type of act is merely an “internal” matter, this returning act of communication can actually be seen as containing several types of otherness, or “extra-quality.” Here, I would like to just briefly suggest a labelling of four such “othernesses”: (i) the quality of circulating in other media a message which then becomes reflected in a new light (This would be “extra” in the sense an outside influencer quality); (ii) secondary and virtually unexpected communicational effects (which would be “extra” as a surplus quality caused by the circulation); (iii) advanced communication with highly evaluated fellow cultures (or “extra” as having a prominence quality); and (iv) understanding that certain impossibilities are present in communication (meaning “extra” as an unreachability quality) (Figure 11).

Aspects of “Extra-quality” in cultural dialogue, in a diagrammatic interpretation of Lotman’s concepts of “auto-communication” and “semiosphere.” Black arrows symbolize the circulation of a cultural product (or “text,” as it were, in Lotman’s terminology).

In short, we could say in this interpretation of how cultural matter circulates, that “extra-quality” can appear as outsideness, surplus, prominence and unreachability. One aspect of auto-communication is also that it by necessity takes time (to leave the sender and come back). As we shall see further on, the impact of time is important for the recognition of other cultures, and how we categorize them. In the case of the theme park, the possibility of extra-qualities could, apart from publishing the idea as news, have appeared for instance in a public consultation process, or in regard of the areas geographically located outside of, but still close to, the area in question. Thus other, more culturally diverse types of surplus than economical ones, tied to for instance touristic effects or job opportunities, can (here and elsewhere in the culture of design and planning) be allowed more attention in evaluation of architectural plans.

In the line of thought that develops cultural semiotics after Lotman (1990), the act of becoming known to the predominant culture is primarily expressed as the idea of bringing “non-text,” or unrecognized matter, into the semiosphere of the well-known culture. This branch of cultural semiotics hence builds partly on the dichotomies of known-unknown and liked-disliked (or admired-detested), i. e. dichotomies that in many cases become somewhat too simplified. In subsequent theorization within this branch of semiotics of culture the dichotomic model has therefore been refined, either through modalizing cultural complexity into “degrees of semiotization” (Posner 2004), or by problematizing the notion of “other” by introducing the double character of “alter” (neighboring) and “alius” (unknown) cultures, both of them standing in opposite positions to the “ego” culture (Sonesson 2000, Sonesson 2014; Cabak Rédei 2007). Posner sees the category of the “extra-cultural” strictly as something “entirely unknown” and regards “counter-cultural” as “known but opposite” (Posner 2004), which together with other categories leads to a mapping of degrees of semiotization or how various types of “text” can be categorized in terms of how much they need cultural coding. The Sonesson branch of extensions of Lotman’s basic model, on the other hand, stays more explicitly with the problem of exchange, by taking into account the division between a foreign other, that can be appreciated/understood (i. e. regarded positively) as an Alter culture versus an other that is ignored/depreciated (regarded negatively) as an Alien culture.

These semiotic theories introduce the idea that cultural constructs have to include varying modes of cultivation, such as when a growing knowledge about the construed culture is the case. Also, the “cultural enforcement,” that constitute the backdrop to mimetic behavior (Bhabha) or imperative necessities (Spivak), is a dynamic process, containing a changing knowledge and deeper interpretation of each other’s symbolic cultural values. Cultural enforcements and its complement, the keeping together of cultural constructions, are, as it seems, obligatory parts of any maintained cultural encounter and merging, and they change over time, notwithstanding that an original forcing stays and lives on as a contested symbolic value.

In the theme park project that deals explicitly with a construal of a (Scandinavian) “culture,” the negotiating parties had, on the one hand, a positive view on each other’s’ capacities (i. e. they stayed in an Ego-Alter relation), but also, willingly or not, left some thematic possibilities unattended to, and some possible voices of opinion unheard (thus producing Alius). We could also see in the design project that time for development were at hand, but that subsequent refinements of the proposals were not reaching more profound levels of interpretation. This leads us to try and see what role time may have on the relationship between cultural agents.

7 The impact of time in semiosis and in cultural exchange

What cultural semiotics on the whole seem to hold more or less as an indirect or implied matter is the impact of time, or rather the fact that states of controversy, or admiration between cultures can change, which is basically what makes cultural divide a matter of politics, especially of course when someone wants to explicitly impose power in order to change established states of exchange. Even if Posner for instance (2004) brings up cultural change, appearing as augmentation or loss of cultural production, this view basically amounts to a static scheme of levels and a quantification of a qualitative relation (cf. Sonesson 2000, 2012) that regards primarily what one culture assimilates, i. e. the mechanisms describing what happens when a new culture is approached is not explicated. And even if such mechanisms and the temporal aspect of cultural encounters is given more space in Sonesson’s (2000) account of European explorers approaching America, or in Cabak Rédei’s (2007) description of reactions to Germaine de Staël during her travels between countries in Europe, time itself is not so much regarded as a component in the very models of cultural encounter. In a more temporal semiotic account, we could possibly adjust this matter, by approaching a Peircean tradition of thought, where there is an inherent line of development of meaning suggesting also a temporal quality, tied to some of his basic categories. Each cultural encounter, and each realized mutual cultural modelling, has temporal features. When one culture, or members thereof, approaches another, different aspects and qualities may be approached simultaneously, in a synchronic process, while other aspects need successive encounters, a diachronic process, to slowly make something become familiar. We can look closer into this familiarisation by applying some thought from Peirce.

In processes of cultural reciprocity and how this reciprocity develops over time, Peirce’s well-known basic constituents of representation can be seen as activated: iconicity (i. e. signification evoked by resemblance or analogy) appear as an instant recognition of something; indexicality (i. e. signification that appears by way of proximity or fragment relations) works a linking or incorporating our impressions of the other culture into our known world; and symbolicity (i. e. signification based in habits or convention) is activated when we have established the common ground needed to articulate a new cultural constructs (cf. Ståhl and Sandin 2011). These three representational faculties appear to a varying degree, and in varying order in human exchange of meaning, in line with contemporary interpretations of Peirce’s tripartite view of the sign as related to the self (Sonesson 2013; Colapietro 1989). In semiosis, i. e. in acts or processes where signification is produced, we assume, in line with Peirce, that iconicity, indexicality and symbolicity appear on the one hand simultaneously (synchronically) as distinguishable forms of signification, and on the other, in a way where they need each other to mature (diachronically).

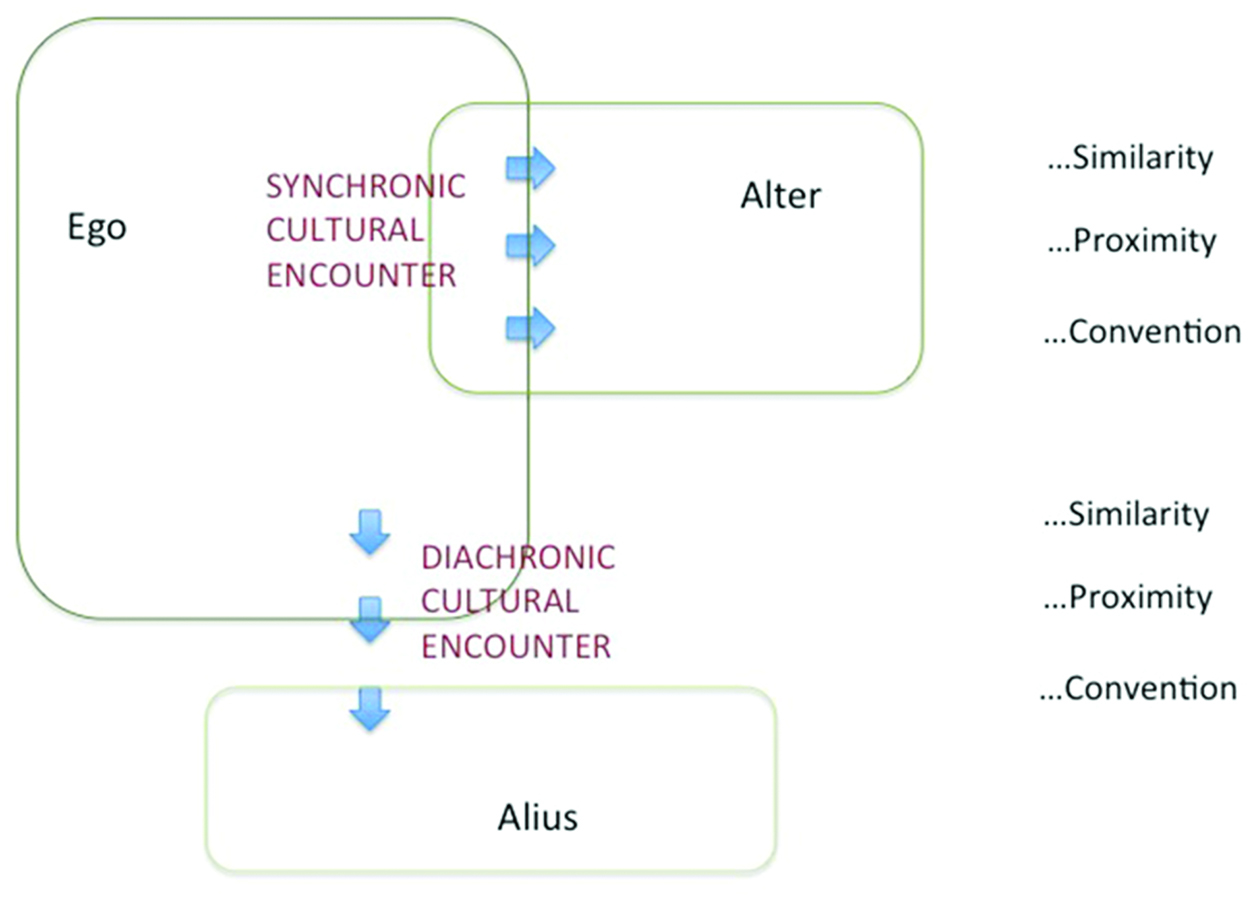

If we apply these Peircean figures of thought to the specific landscape of cultural semiotics, it is not a far-fetched hypothesis that synchronic assimilation is more prevalent when Ego assimilates Alter, whereas diachronic processes would be more likely to appear when Alius is skeptically regarded from the point of view of Ego. Even if both types of temporal processes are part of both types of cultural exchange, we may assume that when a (completely) foreign culture is approached it has to be done in successive steps. The first impressions and recognitions of sounds, forms and materialities are followed by intuitive, or rather motivated, connections to other things, only to be matured in their turn into a more reflected understanding of what it was that was recognized in the first place. In the encounter with another culture, we have, in other words, a sequence aligned with how Peirce imagined impressions maturing into full signs (Ståhl and Sandin 2011). Cultures that are already regarded as reasonably familiar, on the other hand, are rather approached with a larger immediate reliance on, and understanding of, the impressions, links and habits that are encountered. The first type of encounter, with an Alius-culture, will likely need a more substantial measure of trial and interpretational effort. It is also more likely to lead to neglect or misunderstanding, since for instance language or habits may be totally different. If we accept this basic difference between approaches towards known and unknown parties in cultural interaction, we get a description of cultural semiosis where the Ego culture engages a temporally conducted difference, between an Alter culture and an Alius culture, a difference that is partly due to how first impressions are treated (Figure 12).

A model of the separations that an Ego-culture makes between an Alter-culture and an Alius-culture, including how these two types of “otherness” are temporally construed. The model extends previous ones by Sonesson (2000) and Cabak Rédei (2007) and depicts also how the representational (basically Peircean) principles are included, synchronically and diachronically, in cultural interaction processes.

To summarize, this semiosic difference appears as a temporal factor because the representational stages need each other to mature, and this, we may presume, is done differently in approaches towards known (appreciated) and unknown (neglected) cultures respectively.

In theories about design processes and design thinking, the notion of “reflection-in-action” (Schön 2017) suggests a temporal ingredient in the conceptualization of a still unknown future design. Inspired by the American pragmatists following Peirce, and abduction as a logic principle, Schön casts light on the necessity of successive steps of alternating between reflection and making – not unlike Lotman’s autocommunication – when a design idea, and eventually a design proposal develops. What is lacking, however, in Schön’s theory, is a way to incorporate into the progress of design work the wider cultural and psychological aspects, including for instance the presence of controversy (Yaneva 2011) and the carried preconceptions (Kopljar 2016) that are part of everyday design thinking. The semiotic models of culture and the post-colonial theories have such ingredients as a fundament, but this fundament could gain from a clearer incorporation of temporal aspects.

In the architectural design case here addressed we have seen that what initially appeared as just an exposure of a set of clichéd images of Scandinavian culture being part of a likewise clichéd (in the sense of traditionalist) co-operated design proposal, could be seen more as an ongoing construal of culture, where extra-qualities and temporal effects possible in cultural negotiation were both produced and neglected. With more attention paid to other-qualities and a subsequent refinement, the design project could be seen as not only a commercial and managerial problem with some hints on learning about the Scandinavian culture, but a more profound cultural product conditioned also by the surrounding physical geographies and the nearby community, not to mention the existing research and knowledge regarding the Scandinavian heritage and imagery. In a temporal perspective, an alternative subsequent refinement of the project, thus a process with a more profound and re-iterated symbolic depth, could here be seen as opening up other possible cultural futures.

8 Conclusion

The construal of culture, including progressive as well as repressive forces of cultural encounters, conveyed through a study of a preliminary design proposal for a theme park, has here been seen as involving auto-communicative steps and temporality as important features. Architectural design and city planning have been seen as triggering the general case of cultural production, the modelling of culture, and how it can introduce thoughts of diversity as a vital part of the resulting cultural “product.” A semiotic view that emphasizes temporality and the stages of conceptualization needed in recognition of each other’s culture has a potentiality to model what happens in human encounters as these go on. In line with such a process-oriented view we have seen here, in reflection of cultural encounters and co-cultural production, that cultural analysis gains from making temporality an explicit part. This was done by reflecting on the one hand on the multiple “extra” effects that may be generated by auto-communicative acts, i. e. acts where the return of a concept alters the self-view of the sending culture.

We have also seen that both successive and simultaneous building-up of semiotic meaning can add new aspects to what it means to approach and understand another culture. Reciprocal constructs of culture are silently present in the image-production that supports the envisioning of new environments in general. In any situation where there are two or more agents that have an interest related to identity (of for instance commercial, political or projective type), a common view is often wished for, but, in reality, seldom truly made common, or negotiated on equal terms. Not only in the here rendered case of the theme park vision, where the production of “culture” is an explicit architectural task and the actual objective of the design, but in any case of co-operated image-making, more profound reflections on the reciprocity of cultural encounters, and the temporal aspects of these, would be needed to put simplified and stereotyped practical approaches in new light.

It has here been argued that a more reflected recognition of the reciprocal alterity that appears whenever cultural exchange is at hand could inform semiotic modelling of cultures in general, as well as in the specific case of physical planning of future cities and societies. A modelling of cultural formation that take reciprocal alterity into account makes it possible to encompass lateral representational aspects portraying cultural encounters more as intersubjective productions and not only as dichotomic differences or gradual patterns. Such a perspective should in other words also stand a chance to do justice to the diverse accounts of voices, like the ones of commoners, experts and observers, that actually appear in the daily practice of cultural formation.

References

Augé, Marc. 1995 [1992]. Non-places: Introduction to an anthropology of supermodernity, John Howe (trans.). London & New York: Verso.10.1007/978-1-137-12006-9_26Search in Google Scholar

Bhabha, Homi. 1984. Of mimicry and man: The ambivalence of colonial discourse. October 28. 125–133.10.1002/9781119118589.ch3Search in Google Scholar

Bhabha, Homi. 2004. The location of culture. Oxon & New York: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Brown, Brenda. 2002. Landscapes of theme park rides: Media, modes, messages. In Terrence Young & Robert Riley (eds.), Theme park landscapes: Antecedents and variations, 235–268. Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection.Search in Google Scholar

Cabak Rédei, Anna. 2007. An inquiry into cultural semiotics: Germaine de Staël’s autobiographical travel accounts. Lund: Lund University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Certeau, Michel de. 1984. The practice of everyday life, Stephen Rendall (trans.). Berkeley: University of California Press.Search in Google Scholar

Clavé, Salvador Anton. 2007. The global theme park industry. Wallingford & Cambridge: CABI.10.1079/9781845932084.0000Search in Google Scholar

Colapietro, Vincent M. 1989. Peirce’s approach to the self. Albany: State University of New York Press.Search in Google Scholar

Dolnicar, Sara, Bettina Grun & Huong Le. 2008. Cross-cultural comparisons of tourist satisfaction: Assessing analytical robustness. Research Online, University of Wollongong, Faculty of Commerce Papers Archive. http://ro.uow.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1561&context=commpapers (accessed 10 November 2019).Search in Google Scholar

Durkheim, Émile. 1982 [1895]. What is a social fact? W.D. Halls (trans.). In Steven Lukes (ed.), The rules of the sociological method, 50–59. New York: Free Press.10.1007/978-1-349-16939-9_2Search in Google Scholar

ERA. 2002. Economic Research associates memorandum report, preliminary market assessment of Malmö theme park opportunity - Phase 1. Malmö: Malmö Stad.Search in Google Scholar

Healey, Patsy. 2007. Urban complexity and spatial strategies: Towards a relational planning for our times. London & New York: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Joppe, Marion, David Martin & Judith Waalen. 2001. Toronto’s image as a destination: A comparative importance-satisfaction analysis by origin of visitors. Journal of Travel Research 39(3). 252–260.10.1177/004728750103900302Search in Google Scholar

Kolb, David. 2008. Sprawling places. Athens. Georgia & London: The University of Georgia Press.10.1353/book11441Search in Google Scholar

Kopljar, Sandra. 2016. How to think about a place not yet: Studies of affordance and site-based methods for the exploration of design professionals’ expectations in urban development processes. Lund: Lund University Dissertations.Search in Google Scholar

Lazzari, Marco 2012. The role of social networking services to shape the double virtual citizenship of young immigrants in Italy. In Gunilla Bradley, Diane Whitehouse & Angela Lin (eds.), Proceedings of the IADIS International Conference on ICT, society and human beings, 11–18. Iadis Digital Library.Search in Google Scholar

Ljungberg, Anders. 2008. Nöjespark vid Svågertorp kan locka 700 000. Sydsvenskan 12(February). 2008.Search in Google Scholar

Lotman, Iurii. M. 1985. The poetics of everyday behavior in eighteenth-century Russian culture. In Alexander D. Nakhimovsky & Alice S. Nakhimovsky (eds.), The semiotics of Russian cultural history: Essays by Iurii M. Lotman, Lidia Ia. Ginsburg, Boris A. Uspenskii, 67–94. Ithaca, New York & London: Cornell University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Lotman, Yuri M. 1990. Universe of the mind: A semiotic theory of culture. London: Tauris.Search in Google Scholar

Posner, Roland. 2004. Basic tasks of cultural semiotics. In Gloria Withhalm & Josef Wallmannsberger (eds.), Signs of power – Power of signs. essays in honor of Jeff Bernard, 56–89. Vienna: INST.Search in Google Scholar

Relph, Edward. 1976. Place and placelessness. London: Pion Limited.Search in Google Scholar

Sandin, Gunnar. 2012. The construct of emptiness in Augé’s anthropology of ‘non-places.’. In Junichi Toyota, Pernilla Hallonsten & Marina Shchepetunina (eds.), Sense of emptiness: An interdisciplinary perspective, 112–127. Newcastle-upon-Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.Search in Google Scholar

Schön, Donald. 2017. The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. London: Routledge.10.4324/9781315237473Search in Google Scholar

Sinha, Chris. 2011. Iconology and imagination in human development: Explorations in sociogenetic economies. In Armin W. Geertz & Jeppe Sinfing Jensen (eds.), Religious narrative, cognition and culture: Image and word in the mind of narrative, 97–116. Sheffield: Equinox Publishing.Search in Google Scholar

Sonesson, Göran. 2000. Ego meets alter: The meaning of otherness in cultural semiotics. Semiotica 128(3/4). 537–559.10.1515/semi.2000.128.3-4.537Search in Google Scholar

Sonesson, Göran. 2012. Between Homeworld and Alienworld: A primer of cultural semiotics. In Ernest W. B. Hess-Lüttich (ed.), Sign culture – Zeichen kultur, 315–328. Würzburg: Verlag Königshausen & Neumann.Search in Google Scholar

Sonesson, Göran. 2013. The natural history of branching: Approaches to the phenomenology of firstness, secondness, and thirdness. Signs and Society 1(2). 297–325.10.1086/673251Search in Google Scholar

Sonesson, Göran. 2014. Translation and other acts of meaning: In between cognitive semiotics and semiotics of culture. Cognitive Semiotics 7(2). 249–280.10.1515/cogsem-2014-0016Search in Google Scholar

Spivak, Gayatri C. 1988. Can the subaltern speak? In Cary Nelson & Lawrence Grossberg (eds.), Marxism and the interpretation of culture, 271–313. Urbana & Chicago: University of Illinois Press.10.1007/978-1-349-19059-1_20Search in Google Scholar

Spivak, Gayatri C. 2012. An aesthetic education in the era of globalisation. Cambridge, Massachusetts & London: Harvard University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Ståhl, Lars-Henrik & Gunnar Sandin. 2011. Grounds for cultural influence: Visual and non-visual presence of Americanness in contemporary architecture. In Tiziana Migliore (ed.), Retorica del visibile. Strategie dell’immagine tra significazione e comunicazione. 3. Contributi scelti 5, 207–220. Roma: Aracne Editrice.Search in Google Scholar

Wenger, Etienne. 1999. Communities of practice: Learning, meaning and identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511803932Search in Google Scholar

Yaneva, Albena. 2011. From reflecting-in-action towards mapping the real. In Nel Janssens & Isabel Doucet (eds.), Transdisciplinary knowledge production in architecture and urbanism, 117–128. Dordrecht: Springer Science + Business Media B.V.10.1007/978-94-007-0104-5_8Search in Google Scholar

© 2020 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Introduction: The Making of Them and Us – Cultural encounters conveyed also through pictorial means

- Research Articles

- Translation as culture: The example of pictorial-verbal transposition in Sahagún’s primeros memoriales and codex florentino

- Germaine de Staël’s Réflexions sur le procès de la reine: An act of compassion?

- Mao’s Homeworld(s) – A comment on the use of propaganda posters in post-war China

- Construing Scandinavia: A semiotic account of intercultural exchange in theme park design

- The cultural semiotics of African encounters: Eighteenth-Century images of the Other

- Intercultural parallax: Comparative modeling, ethnic taxonomy, and the dynamic object

- Early body ornamentation as Ego-culture: Tracing the co-evolution of aesthetic ideals and cultural identity

- Intercultural competition over resources via contests for symbolic capitals

- Ethical food packaging and designed encounters with distant and exotic others

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Introduction: The Making of Them and Us – Cultural encounters conveyed also through pictorial means

- Research Articles

- Translation as culture: The example of pictorial-verbal transposition in Sahagún’s primeros memoriales and codex florentino

- Germaine de Staël’s Réflexions sur le procès de la reine: An act of compassion?

- Mao’s Homeworld(s) – A comment on the use of propaganda posters in post-war China

- Construing Scandinavia: A semiotic account of intercultural exchange in theme park design

- The cultural semiotics of African encounters: Eighteenth-Century images of the Other

- Intercultural parallax: Comparative modeling, ethnic taxonomy, and the dynamic object

- Early body ornamentation as Ego-culture: Tracing the co-evolution of aesthetic ideals and cultural identity

- Intercultural competition over resources via contests for symbolic capitals

- Ethical food packaging and designed encounters with distant and exotic others