Abstract

This paper reviews how different policies jointly affect employment among disabled individuals. I used Google Scholar to find literature on welfare systems, disability, health and employment. I found literature on flexicurity through snowballing. I evaluate the following hypotheses: (1) generous disability benefits constitute a disincentive to work; (2) high investments in activation policies have a positive effect on employment; (3) a flexible labour market fosters employment; (4) disabled workers are more likely to be in temporary employment in countries with a flexible labour market. Hypotheses 1 and 3 find no support in the selected literature. Literature on hypotheses 2 and 4 is inconclusive. Future research avenues are suggested.

1 Introduction

Disabled people include those who have long-term physical, mental, intellectual or sensory impairments which in interaction with various barriers may hinder their full and effective participation in society on an equal basis with others.[1] Thus, disability itself stems from the interplay between individuals with a health condition, for example cerebral palsy, Down syndrome or depression, with personal and environmental factors including negative attitudes, inaccessible infrastructure, and limited social support.[2] While some health conditions associated with disability result in poor health, others do not.[3]

Over a billion people (15%) worldwide are disabled. Disability prevalence is higher among women than men, it increases with age and decreases with income. Disabled people face a higher risk of poverty and social exclusion.[4] Concerning labour market outcomes, disability has a negative impact on employment prospects (Webber and Bjelland 2015), and earnings (Jones 2008). On average, disabled people (most of which are not employed[5]) are less educated than nondisabled individuals (World Health Organization & World Bank 2011). However, disabled workers are more educated than their nondisabled counterparts on average (Jones 2010) and often overeducated with respect to the requirements of their jobs (Jones and Sloane 2010). This is consistent with disability onset leading to downward occupational movement (Jones et al. 2014). Thus, disability is associated with reduced odds of employment and lower job quality.

2 Current Situation

Disability policy must achieve two goals at the same time: labour market integration and income security. Disabled people must be empowered to engage in gainful employment, but they must also be provided with means to achieve an adequate standard of living, even if they are less productive than their nondisabled counterparts or unable to work (OECD 2003). Disability policies have been converging since 1990. In general, benefits have been getting progressively less generous, with a tightening of eligibility criteria. Most countries have placed an increased emphasis on active labour market policies (OECD 2010; Scharle et al. 2015), even though investments in such policies as percentage of GDP remain relatively low (Pignatti and Van Belle 2021). While demand-side activation policies have received little attention and funding (Adams et al. 2019), many countries have made benefit recipience conditional on participation in job training programs (Waddington et al. 2016).

Generous disability benefits have a small but statistically significant negative impact on employment among disabled people, while tightening eligibility criteria has no effect on employment (Barr et al. 2010; McHale et al. 2020). Disabled people no longer eligible for permanent benefits do not engage in the labour market, and end up with temporary benefits or no benefits at all (Jensen et al. 2019).

Regarding active labour market policies, it must be acknowledged that they are very heterogeneous. However, a broad distinction can be made between supply-side and demand-side policies. Supply-side policies aim at making disabled individuals more employable, for example through job training programs. Demand-side activation policies aim at stimulating the demand for disabled workers. They include (but are not limited to) employment quotas, wage subsidies, funding for workplace accommodations, and sheltered employment. Clayton et al. (2012) review several activation policies in four countries (Canada, Denmark, Norway, and the UK). They find no convincing evidence that job training programs are effective, noting that some interventions favour more advantaged disabled people who are close to the labour market. On the contrary, generous wage subsidies increase employment among disabled people. The same holds for workplace accommodations and involving employers in return to work planning, which are found to be effective even though uptake is low. Regarding employment quotas, their effectiveness depends crucially on the amount of the non-compliance penalty In Austria, increasing non-compliance penalties led to better employment outcomes for disabled people (Lalive et al. 2013; Wuellrich 2010), while in Italy (Agovino et al. 2019) and France (Barnay et al. 2019) non-compliance penalties are too low to affect hiring decisions. If anything, employers may be dissuaded from hiring disabled candidates by the cost of workplace accommodations (Fuchs 2014), despite the availability of financial support to face such expenses (Bellemare et al. 2018). Moreover, employment quotas often are concentrated in low quality jobs (Fuchs 2014). The OECD (2010) considers sheltered employment an effective activation policy only if disabled individuals can easily transition to the open labour market. People employed by sheltered workshops are economically inactive, have no right to a minimum wage and cannot join trade unions, even if the workshop provides goods or services for the open market (Visier 1998). There is some evidence that sheltered workshops protect employment during economic recessions, when disabled people are more likely to lose their jobs in the open labour market (Álvarez 2012).

As can be seen, the existing literature reviews on disability policy examine either benefits or activation policies, never both at the same time. Furthermore, the role of different welfare state systems is completely neglected by reviews of literature on disability and the labour market, and so is that of flexicurity. Finally, most literature reviews focus on employment itself, with no consideration about job quality. I aim to fill these gaps in the literature.

3 Theoretical Framework

Europe is characterised by five different welfare state systems (or simply “welfare systems”), which are relatively stable over time (Esping-Andersen 1990; Ferrera 1996). The liberal (or Anglo-Saxon) welfare system characterises all English-speaking countries and Israel (Doron 2001). It has means-tested assistance schemes, with low benefits and strict eligibility criteria. Moreover, employment protection is minimal, resulting in a very flexible labour market. The conservative (corporatist or Bismarckian) welfare system has been adopted by German and French speaking European countries, where redistribution is low and benefit entitlement is determined by one’s earnings, as benefits are often provided by employers. However, the freedom of the market is curtailed, resulting a certain degree of employment protection. The social-democratic regime is characteristic of Northern European countries, which promote full employment and income protection through a high level of decommodification (i.e. generous and universalistic benefits), high investments in activation policies as a percentage of GDP, and strong employment protection.

Welfare sceptics believe that generous benefits lead to the emergence of “dependency cultures”, weakening people’s motivation to engage in employment and making it socially acceptable to live on benefits (Heinemann 2008). On the contrary, the social investment perspective posits that benefits provide individuals with the resources they would otherwise lack in order to participate in the labour market (Midgley 1999). Therefore, the welfare scepticism view would predict worse employment outcomes for disabled people living in countries characterised by generous welfare systems and high employment protection, ceteris paribus, while the social investment perspective would predict the opposite. On the one hand, if disabled workers are “last hired, first fired” (Kruse and Schur 2003), greater flexibility will result in lower employment odds, especially during economic downturns (Reeves et al. 2014). On the other hand, potential employers may be more willing to recruit disabled job applicants if can fire them easily, should they not be a good fit for the job (Heggebø 2015). The welfare scepticism view and the social investment perspective have some common ground, as they both posit that high investments in activation policies foster employment.

Flexicurity has emerged as a way to reconcile flexibility (which leads to job creation) and economic security. The concept originated in the Netherlands, where employment protection for part-time workers was increased in the mid-90s. The Danish flexicurity model, on the other hand, combines reduced employment protection with generous benefits and an increased emphasis on activation policies (Bekker and Mailand 2019). A skill component is introduced as well, with high-skilled workers being more protected than their low-skilled counterparts (Danquah 2018; Heggebø 2016). Flexicurity may provide disabled people with options for partial work while keeping them economically safe, thus improving their employment prospects (Greve 2009).

4 Methodology

I used Google scholar to find literature on welfare systems, disability, health and employment by entering relevant keywords, and found works on flexicurity through snowballing. I then screened the literature for relevance. I selected works which use quantitative and/or qualitative methods to analyse how employment commitment and different employment outcomes among disabled people are affected by one or more of the following factors:

Disability benefits and activation policies.

Flexibility/Flexicurity.

Prevalence of temporary employment in the national labour market.

There is some overlap in the literature, with eight papers analysing the impact of benefits and activation policies, three of which consider flexibility as well. One paper analyses the effect of labour market flexibility by comparing Denmark to neighbouring countries (Heggebø 2015). Temporary employment is only investigated in two papers, both focused on Scandinavia.

The literature is summarized in Table 1 and ordered chronologically. It spans thirteen years, from 2007 to 2020, with the greatest number of articles published in the years 2015, 2016 and 2019. While a few scholars only contributed one work (e.g. Blekesaune 2007), most contributed more, often with co-authors.

Synthesis of selected literature.

| Work | Main findings |

|---|---|

| Blekesaune (2007) | Generous benefits and high investments in activation policies have a positive impact on employment among disabled people, whereas labour market flexibility has a negative one. |

| Holland et al. (2011) | Employment rates of disabled people are higher in Northern than in Anglo-Saxon systems. |

| Van der Wel et al. (2011) | Generous benefits and investments in activation policies have a positive impact on employment of disabled people, the opposite holding for flexibility. |

| Van der Wel et al. (2012) | Employment rates of disabled people are highest in Northern countries, lowest in Eastern and Anglo-Saxon systems. |

| Heggebø (2015) | Disabled people fare worse in terms of employment in Denmark than in other Scandinavian countries. |

| McAllister et al. (2015) | Flexicurity does not affect the employment prospects of disabled people. |

| Van der Wel and Halvorsen (2015) | Employment commitment is higher in generous and more activating countries. |

| Backhans et al. (2016)* | Flexicurity does not affect return to work (RTW) after disability onset. |

| Heggebø (2016) | Flexicurity has no effect on the recruitment of disabled people, but they are more likely to be in temporary employment in Denmark and Sweden. |

| Kuznetsova et al. (2017) | Employment outcomes of disabled people are better in the Northern than in the Eastern welfare system. |

| Danquah (2018) | In Sweden, disabled people are more likely to be in temporary employment. |

| Geiger et al. (2019) | Disability policy reforms had no effect on disabled people’s employment. |

| Heggebø and Buffel (2019) | Flexicurity does not affect the employment prospects of disabled people. |

| Reinders Folmer et al. (2020) | Generous benefits have a positive effect on the employment chances of disabled people, while investments in activation policies have no effect. |

-

*This is the only qualitative work, and it employs a qualitative fuzzy set methodology.

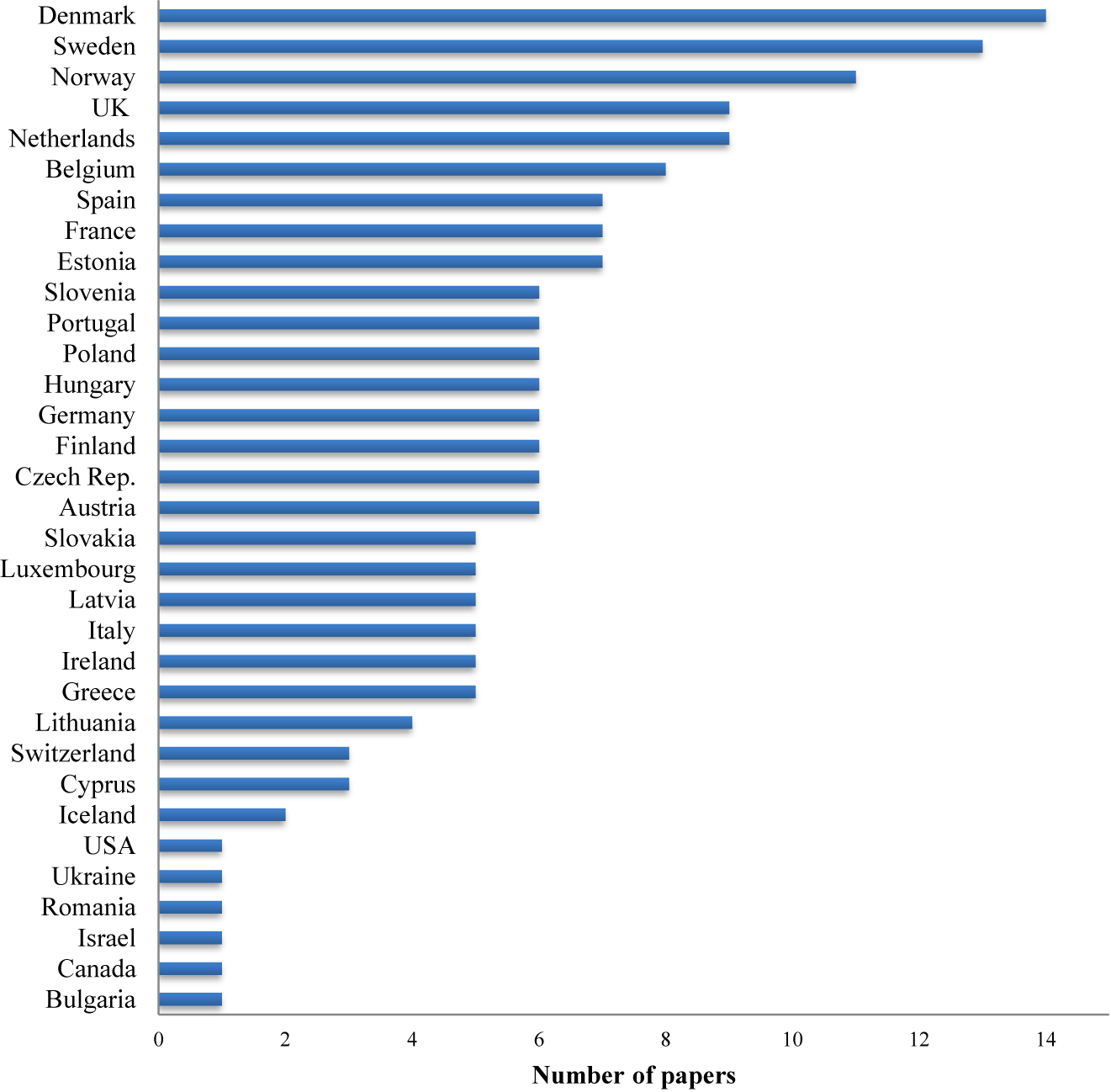

The bar chart in Figure 1 lists all the countries considered in every work reviewed. As can be seen, while Scandinavian countries appear in most papers (Denmark in all of them), followed by the UK, other countries are mentioned only in one paper. This is the case for all non-European countries, as well as Malta. Furthermore, all the works reviewed focus on the Global North. Since the selected literature is very heterogeneous, it is important to illustrate how key variables are measured.

Geographical distribution of the literature.

4.1 Disability, Poor Health, Employment and Policy

National surveys ask about disability and general health in separate questions. The exact wording of these questions changes depending on the survey and year, but usually questions about disability enquire whether the respondent has any longstanding health condition(s) limiting them in activities, while questions about general health require the respondent to rate their general health on a scale ranging from “Very good” to “Very poor”. People are in “Poor health” if they rate their health as “Fair”, “Poor” or “Very Poor”. Most of the selected literature (12 papers) identifies people as disabled if they report activity limitation due to health problems. Van der Wel and Halvorsen (2015) investigate employment commitment among disadvantaged groups, including people with poor health. Geiger et al. (2019) build their own measure of disability and health combined. The reason these two papers are included is twofold. Firstly, poor health has a negative impact on employment outcomes (García-Gómez 2011). Secondly, there is some overlap between literature on disability and literature on poor health, to the point where four papers (Danquah 2018; Heggebø 2015, 2016; Heggebø and Buffel 2019) consider the impact of poor health on employment outcomes in addition to that of disability (in separate analyses). Six papers (Heggebø 2015, 2016; Holland et al. 2011; McAllister et al. 2015; Van der Wel et al. 2011, 2012) analyse the employment outcomes of people with activity limitations due to health problems as depending on education, since disabled people with a low education face a double hurdle.

When it comes to disability policy, the joint effect of benefits and activation policies is investigated using Eurostat and/or OECD (2010) policy indicators in five papers (Blekesaune 2007; Geiger et al. 2019; Reinders Folmer et al. 2020; Van der Wel and Halvorsen 2015; Van der Wel et al. 2011), and comparing different welfare systems in three papers (Holland et al. 2011; Kuznetsova et al. 2017; Van der Wel et al. 2012), with Van der Wel et al. (2012) including GDP per capita and business cycle as country-level variables as well. The effect of flexibility/flexicurity on the employment outcomes of disabled people is analysed primarily through cross-country comparisons (Danquah 2018; Heggebø 2015, 2016; Heggebø and Buffel 2019; Holland et al. 2011; McAllister et al. 2015).

The rationale is that comparing countries with similar institutional characteristics, which only differ in terms of labour market flexibility (e.g. Denmark and Norway) makes it possible to disentangle the effect of flexibility from that of other factors (Danquah 2018; Heggebø 2015, 2016; Heggebø and Buffel 2019), thus performing a natural experiment. A few papers (Backhans et al. 2016; Blekesaune 2007; Van der Wel et al. 2011) use policy indicators to evaluate the effect of flexibility on the employment outcomes of disabled people, adding other country-level variables as controls. Backhans et al. (2016)’s is the only qualitative paper, using qualitative fuzzy-set methodology to investigate the effect of different policy indicators related to flexicurity on the percentage of individuals returning to work after disability onset.

Most of the selected literature measures labour market outcomes in terms of employment odds (Blekesaune 2007; Geiger et al. 2019; Heggebø and Buffel 2019; Holland et al. 2011; Kuznetsova et al. 2017; McAllister et al. 2015; Reinders Folmer et al. 2020), non-employment odds (Van der Wel et al. 2011, 2012) or unemployment odds (Heggebø 2015). Other outcomes of interest include job recruitment (Heggebø 2016), return to work after disability onset (Backhans et al. 2016), and temporary employment (Danquah 2018; Heggebø 2016), where temporary jobs are considered low quality, and the aforementioned employment commitment (Van der Wel and Halvorsen 2015).

With the exception of Geiger et al. (2019), the literature focuses on inequalities in employment outcomes between disabled and nondisabled people. For example, the Southern welfare system performs better than the Anglo-Saxon system even though the employment rate of disabled people is lower in Southern Europe than in Ireland and the UK. The reason is that the difference between the employment rate of nondisabled and disabled people is much smaller in Southern Europe than in English-speaking countries and in Israel.

4.2 Hypotheses

The selected literature allows us to evaluate the following hypotheses:

Generous benefits constitute a disincentive to work;

High investments in activation policies have a positive effect on employment;

A flexible labour market fosters employment;

Disabled workers are more likely to be in temporary employment in countries with a flexible labour market;

Hypotheses (1) and (3) are compatible with welfare scepticism and at odds with the social investment perspective. Hypothesis (2) is supported by both theoretical frameworks. Hypothesis (4) derives from the social investment perspective. If the employment chances of disabled people living in countries with a flexible labour market are comparatively lower, then those of them who hold a job are more likely to have a low quality job.

5 Results

Hypothesis 1 is not supported, while the social investment perspective is partially supported. Six papers (Blekesaune 2007; Holland et al. 2011; Kuznetsova et al. 2017; Reinders Folmer et al. 2020; Van der Wel et al. 2011, 2012) find that generous benefits are associated with better employment outcomes among disabled people, and one finds no effect (Geiger et al. 2019). Van der Wel and Halvorsen (2015) find that employment commitment is higher in more generous and activating welfare systems, although the difference in employment commitment between healthy people and people in poor health is greater. Therefore, the only two works which contradict the welfare investment perspective on the issue of benefits are the ones which conflate disability and poor health. This illustrates how the choice of disability model (Mont 2007) can affect results.

Evidence on hypothesis 2 is inconclusive, with half of the literature finding a positive effect of activation policies on the employment chances of disabled people, three papers finding no effect and one paper (Reinders Folmer et al. 2020) finding a negative association. Holland et al. (2011) remark that differences in employment rate between disabled and nondisabled people are smaller in Norway than in other Scandinavian countries, despite negligible investments in activation policies. Reinders Folmer et al. (2020) find that both demand-side and supply-side activation policies (taken separately) do not affect the employment odds of disabled individuals, while sheltered employment has a positive impact.[6] Thus, they argue that supply-side activation policies, which make up the majority of activation measures, are ineffective.

Hypothesis 3 is not supported. In fact, Blekesaune (2007), Van der Wel et al. (2011) and Heggebø (2015) find that labour market flexibility has a negative impact on the employment prospects of disabled individuals, while Holland et al. (2011) find it has no effect. Heggebø (2016) notes that disabled people with high education are more likely to be recruited in Denmark than in either Norway or Sweden. However, this cannot be due to a more flexible labour market, as high skill workers benefit from high employment protection. Moreover, the literature on flexicurity that considers Europe as a whole, rather than focusing on Scandinavia, agrees that flexicurity has no effect on either the employment chances of disabled people (Heggebø and Buffel 2019; McAllister et al. 2015) or the likelihood of them retaining their job after disability onset (Backhans et al. 2016).

Evidence on hypothesis 4 is inconclusive. Heggebø (2016) finds that disabled workers are twice as likely to be in temporary employment in Denmark, and the same pattern is present (to a lesser extent) in Sweden, but not in Norway. He notes that temporary employment is more prevalent in Sweden than in other Scandinavian countries. However, Danquah (2018) finds that disabled workers are more likely to be in temporary employment only in Sweden, not in neighbouring countries.

6 Conclusion

The present work reviews the literature investigating the joint effect of different disability and labour market policies on the employment outcomes of disabled individuals. I formulate four hypotheses: three encapsulate the welfare scepticism perspective, while the fourth is derived from the social investment perspective.

When disability is measured by limitation in daily activities due to health problems, generous benefits have a positive impact on employment outcomes. Regarding activation policies, evidence is mixed. Neither labour market flexibility nor flexicurity foster employment among disabled individuals. In fact, there is partial evidence that flexibility has a negative impact on the employment chances of disabled individuals. There is no conclusive evidence linking disability to a higher likelihood of temporary employment. Overall, the welfare scepticism perspective is not supported, while the social investment perspective is partially supported.

To sum up, considering different policies separately can be misleading (Heggebø and Buffel 2019; Reinders Folmer et al. 2020). Moreover, the different implementation of flexicurity across countries may make it difficult to evaluate its effectiveness (Viebrock and Clasen 2009). Furthermore, activation policies are very heterogeneous both within and especially across countries (Fuchs 2014; Visier 1998), which might explain why evidence about them is mixed.

The strength of the present work lies in the inclusion of papers using different methodologies, which lends robustness to the results. Its main limitation is the fact that three out of the fourteen papers reviewed (Holland et al. 2011; Kuznetsova et al. 2017; McAllister et al. 2015) perform cross-country comparisons between countries with different institutional characteristics, adding no country level controls. Thus, the methodology used in those particular works is rather weak. However, the results they obtain align with those obtained using a robust methodology (e.g. Blekesaune 2007, Van der Wel et al. 2011).

Future research could further explore the effect of disability policies on job quality (Danquah 2018; Heggebø 2016) by considering the earnings differential between disabled and nondisabled workers across countries and/or welfare systems. Moreover, the literature on the impact of different policies specifically on recruitment of disabled workers (Heggebø 2016) and return to work after disability onset (Backhans et al. 2016) is still scarce.

References

Adams, L., Cartmell, B., Foster, R., Foxwell, M., Holker, L., Pearson, A., and Kitching, J. (2019). Understanding self-employment for people with disabilities and health conditions. DPW Research Reports (974), Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/self-employment-for-people-with-disabilities-and-health-conditions/understanding-self-employment-for-people-with-disabilities-and-health-conditions (Accessed 28 October 2022).Search in Google Scholar

Agovino, M., Marchesano, K., and Garofalo, A. (2019). Policies based on mandatory employment quotas for disabled workers: the case of Italy. Mod. Italy J. Assoc. Study Mod. Italy 24: 295–315, https://doi.org/10.1017/mit.2019.14.Search in Google Scholar

Álvarez, V.R. (2012). El empleo de las personas con discapacidad en la gran recesión:¿ Son los Centros Especiales de Empleo una excepción? Estud. Econ. Apl. 30: 237–259.10.25115/eea.v30i1.3387Search in Google Scholar

Backhans, M.C., Mosedale, S., Bruce, D., Whitehead, M., and Burström, B. (2016). What is the impact of flexicurity on the chances of entry into employment for people with low education and activity limitations due to health problems? A comparison of 21 European countries using Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA). BMC Publ. Health 16: 842, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-3482-2.Search in Google Scholar

Barnay, T., Duguet, E., Le Clainche, C., and Videau, Y. (2019). An evaluation of the 1987 French disabled workers act: better paying than hiring. Eur. J. Health Econ. 20: 597–610, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-018-1020-0.Search in Google Scholar

Barr, B., Clayton, S., Whitehead, M., Thielen, K., Burström, B., Nylén, L., and Dahl, E. (2010). To what extent have relaxed eligibility requirements and increased generosity of disability benefits acted as disincentives for employment? A systematic review of evidence from countries with well-developed welfare systems. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 64: 1106–1114, https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2010.111401.Search in Google Scholar

Bekker, S. and Mailand, M. (2019). The European flexicurity concept and the Dutch and Danish flexicurity models: how have they managed the great recession? Soc. Pol. Adm. 53: 142–155, https://doi.org/10.1111/spol.12441.Search in Google Scholar

Bellemare, C., Goussé, M., Lacroix, G., and Marchand, S. (2018). Physical disability and labor market discrimination: evidence from a field experiment. HCEO Working Paper Series 2018(027).10.2139/ssrn.3170250Search in Google Scholar

Blekesaune, M. (2007). Have some European countries been more successful at employing disabled people than others? In: (No. 2007–23). ISER working paper series.Search in Google Scholar

Clayton, S., Barr, B., Nylen, L., Burström, B., Thielen, K., Diderichsen, F., and Whitehead, M. (2012). Effectiveness of return-to-work interventions for disabled people: a systematic review of government initiatives focused on changing the behaviour of employers. Eur. J. Publ. Health 22: 434–439, https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckr101.Search in Google Scholar

Danquah, A. (2018). Health inequalities in temporary employment. A Cross-National Comparative Study of Denmark, Norway, Sweden.Search in Google Scholar

Doron, A. (2001). Social welfare policy in Israel: developments in the 1980s and 1990s. Isr. Aff. 7: 153–180, https://doi.org/10.1080/13537120108719619.Search in Google Scholar

Esping-Andersen, G. (1990). The three worlds of welfare capitalism. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ.10.1177/095892879100100108Search in Google Scholar

Ferrera, M. (1996). The ‘southern model’ of welfare in social Europe. J. Eur. Soc. Pol. 6: 17–37, https://doi.org/10.1177/095892879600600102.Search in Google Scholar

Reinders, Folmer, C.P., Mascini, P., and Van der Veen, R.J. (2020). Evaluating social investment in disability policy: impact of measures for activation, support, and facilitation on employment of disabled persons in 22 European countries. Soc. Policy Adm. 54: 792–812.10.1111/spol.12579Search in Google Scholar

Fuchs, M. (2014). Quota systems for disabled persons: parameters, aspects, effectivity. European Centre for social Welfare policy and research, Vienna.Search in Google Scholar

García-Gómez, P. (2011). Institutions, health shocks and labour market outcomes across Europe. J. Health Econ. 30: 200–213, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2010.11.003.Search in Google Scholar

Geiger, B.B., Böheim, R., and Leoni, T. (2019). The growing American health penalty: international trends in the employment of older workers with poor health. Soc. Sci. Res. 82: 18–32, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2019.03.008.Search in Google Scholar

Greve, B. (2009). The labour market situation of disabled people in European countries and implementation of employment policies: a summary of evidence from country reports and research studies. In: Academic network of European disability experts (ANED), p. 140.Search in Google Scholar

Heggebø, K. (2015). Unemployment in Scandinavia during an economic crisis: cross-national differences in health selection. Soc. Sci. Med. 130: 115–124, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.02.010.Search in Google Scholar

Heggebø, K. (2016). Hiring, employment, and health in Scandinavia: the Danish ‘flexicurity’ model in comparative perspective. Eur. Soc. 18: 460–486, https://doi.org/10.1080/14616696.2016.1207794.Search in Google Scholar

Heggebø, K. and Buffel, V. (2019). Is there less labor market exclusion of people with ill health in “flexicurity” countries? Comparative evidence from Denmark, Norway, The Netherlands, and Belgium. Int. J. Health Serv. 49: 476–515, https://doi.org/10.1177/0020731419847591.Search in Google Scholar

Heinemann, F. (2008). Is the welfare state self-destructive? A study of government benefit morale. Kyklos 61: 237–257, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6435.2008.00400.x.Search in Google Scholar

Holland, P., Nylén, L., Thielen, K., van der Wel, K.A., Chen, W.H., Barr, B., and Uppal, S. (2011). How do macro- level contexts and policies affect the employment chances of chronically ill and disabled people? Part II: the impact of active and passive labor market policies. Int. J. Health Serv. 41: 415–430, https://doi.org/10.2190/hs.41.3.b.Search in Google Scholar

Jensen, N.K., Brønnum-Hansen, H., Andersen, I., Thielen, K., McAllister, A., Burström, B., and Diderichsen, F. (2019). Too sick to work, too healthy to qualify: a cross-country analysis of the effect of changes to disability benefits. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 73: 717–722, https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2019-212191.Search in Google Scholar

Jones, M.K. (2008). Disability and the labour market: a review of the empirical evidence. J. Econ. Stud. 35: 405–424, https://doi.org/10.1108/01443580810903554.Search in Google Scholar

Jones, M. (2010). Disability, education and training. Econ. Lab. Mark. Rev. 4: 32–37, https://doi.org/10.1057/elmr.2010.49.Search in Google Scholar

Jones, M.K. and Sloane, P.J. (2010). Disability and skill mismatch. Econ. Rec. 86: 101–114, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4932.2010.00659.x.Search in Google Scholar

Jones, M., Mavromaras, K., Sloane, P., and Wei, Z. (2014). Disability, job mismatch, earnings and job satisfaction in Australia. Camb. J. Econ. 38: 1221–1246, https://doi.org/10.1093/cje/beu014.Search in Google Scholar

Kruse, D. and Schur, L. (2003). Employment of people with disabilities following the ADA. Ind. Relat. J. Econ. Soc. 42: 31–66, https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-232x.00275.Search in Google Scholar

Kuznetsova, Y., Yalcin, B., and Priestley, M. (2017). Labour market integration and equality for disabled people: a comparative analysis of Nordic and Baltic countries. Soc. Pol. Adm. 51: 577–597, https://doi.org/10.1111/spol.12314.Search in Google Scholar

Lalive, R., Wuellrich, J.P., and Zweimüller, J. (2013). Do financial incentives affect firms’ demand for disabled workers? J. Eur. Econ. Assoc. 11: 25–58, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1542-4774.2012.01109.x.Search in Google Scholar

McAllister, A., Nylén, L., Backhans, M., Boye, K., Thielen, K., Whitehead, M., and Burström, B. (2015). Do ‘flexicurity’ policies work for people with low education and health problems? A comparison of labour market policies and employment rates in Denmark, The Netherlands, Sweden, and the United Kingdom 1990–2010. Int. J. Health Serv. 45: 679–705, https://doi.org/10.1177/0020731415600408.Search in Google Scholar

McHale, P., Pennington, A., Mustard, C., Mahood, Q., Andersen, I., Jensen, N.K., and Barr, B. (2020). What is the effect of changing eligibility criteria for disability benefits on employment? A systematic review and meta-analysis of evidence from OECD countries. PLoS One 15: e0242976, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0242976.Search in Google Scholar

Midgley, J. (1999). Growth, redistribution, and welfare: toward social investment. Soc. Serv. Rev. 73: 3–21, https://doi.org/10.1086/515795.Search in Google Scholar

Mont, D. (2007). Measuring disability prevalence, Vol. 706. Special Protection, World Bank, Washington, DC.Search in Google Scholar

OECD (2010). Sickness, disability and work: breaking the barriers: a synthesis of findings across OECD countries. OECD Publishing, Paris.10.1787/9789264088856-enSearch in Google Scholar

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (2003). Transforming disability into ability: policies to promote work and income security for disabled people. OECD, Paris, pp. 1–219.Search in Google Scholar

Pignatti, C. and Van Belle, E. (2021). Better together: active and passive labour market policies in developed and developing economies. IZA J. Dev. Migr. 12.10.2478/izajodm-2021-0009Search in Google Scholar

Reeves, A., Karanikolos, M., Mackenbach, J., McKee, M., and Stuckler, D. (2014). Do employment protection policies reduce the relative disadvantage in the labour market experienced by unhealthy people? A natural experiment created by the Great Recession in Europe. Soc. Sci. Med. 121: 98–108, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.09.034.Search in Google Scholar

Scharle, Á., Váradi, B., and Samu, F. (2015). Policy convergence across welfare regimes: the case of disability policies In: (No. 76). WWWforEurope working paper.Search in Google Scholar

Van der Wel, K.A., Dahl, E., and Thielen, K. (2011). Social inequalities in ‘sickness’: European welfare states and non-employment among the chronically ill. Soc. Sci. Med. 73: 1608–1617, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.09.012.Search in Google Scholar

Van der Wel, K.A., Dahl, E., and Thielen, K. (2012). Social inequalities in “sickness”: does welfare state regime type make a difference? A multilevel analysis of men and women in 26 European countries. Int. J. Health Serv. 42: 235–255, https://doi.org/10.2190/hs.42.2.f.Search in Google Scholar

Van der Wel, K.A. and Halvorsen, K. (2015). The bigger the worse? A comparative study of the welfare state and employment commitment. Work. Employ. Soc. 29: 99–118, https://doi.org/10.1177/0950017014542499.Search in Google Scholar

Viebrock, E. and Clasen, J. (2009). Flexicurity: a state-of-the-art review. In: REC-WP working papers on the reconciliation of work and welfare in Europe, (01–2009).10.2139/ssrn.1489903Search in Google Scholar

Visier, L. (1998). Sheltered employment for persons with disabilities. Int. Lab. Rev. 137: 347.Search in Google Scholar

Waddington, L., Pedersen, M., and Liisberg, M.V. (2016). Get a job: active labour market policies and persons with disabilities in Danish and European union policy. Dub. ULJ 39: 1.Search in Google Scholar

Webber, D.A. and Bjelland, M.J. (2015). The impact of work-limiting disability on labor force participation. Health Econ. 24: 333–352, https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.3020.Search in Google Scholar

World Health Organization & World Bank (2011). World report on disability 2011. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland.Search in Google Scholar

Wuellrich, J.P. (2010). The effects of increasing financial incentives for firms to promote employment of disabled workers. Econ. Lett. 107: 173–176, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2010.01.016.Search in Google Scholar

© 2022 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Natural Selection, Technological Progress, and the Origin of Human Longevity

- Price of a Surprise: The Effects of Election Outcomes on Stock Market Returns and Volatility

- Survey

- China’s Official Finance in the Global South: Whatʼs the Literature Telling Us?

- How Do Different Policies Jointly Affect the Employment Prospects of Disabled Individuals? A Review of the Literature

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Natural Selection, Technological Progress, and the Origin of Human Longevity

- Price of a Surprise: The Effects of Election Outcomes on Stock Market Returns and Volatility

- Survey

- China’s Official Finance in the Global South: Whatʼs the Literature Telling Us?

- How Do Different Policies Jointly Affect the Employment Prospects of Disabled Individuals? A Review of the Literature