Abstract

When multi-product firms make simultaneous price-fixing agreements in different markets, they may compartmentalize these agreements by having different individuals manage them so as to avoid the contagion of antitrust authority investigations. Leniency programs can overcome this strategy but may also lead to procollusive effects for centralized firms. The introduction of US amnesty plus programs can have different competitive effects, and leniency programs may modify firms’ choice of internal structure.

Acknowledgements

We received useful feedback during conferences or seminars at the Association Française de Sciences Economiques (Lyon 2014), European Association for Research in Industrial Economics (Lisbon 2016), external seminar in Paris Ouest Nanterre (Paris 2016), International Industrial Organization Conference (Boston 2017) and Société Canadienne de Sciences Economiques (Ottawa 2017). We thank participants for helpful comments and discussion. We thank the anonymous reviewer and editor for their comments and suggestions. We have benefited from discussions with Richard Ruble. This article supersedes an unpublished working paper Dargaud and Jacques (2015a). The usual disclaimer applies.

Appendix A: Computations related to sustainability conditions

We set

Threshold values of fines under the different scenarios are reported in the Tables 1 and 2.

Threshold values of fines – Scenarios No leniency, SL-S and SL-L.

| No leniency | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| F2 | |||

| [3mm] F3 | |||

| [3mm] | |||

| [3mm] FMs | |||

| [3mm] | |||

| [3mm] Freport | |||

| [3mm] FMc | |||

| [4mm] FUseq | |||

| [4mm] F1 |

Threshold values of fines -Scenarios AP-S + and AP-L +.

| F2 | ||

| [3mm] F3 | ||

| [3mm] | ||

| [3mm] FMs | ||

| [3mm] | ||

| [3mm] Freport | ||

| [3mm] FMc | ||

| [4mm] FUseq | ||

| [3mm] F1 |

Appendix B: Computations related to imperfect compartmentalization (Section 3.4)

Without leniency and considering µ3 > 0 expected profits and sustainability conditions are reported in the Table 3. Note that

Imperfect compartmentalization.

| Strategy | Expected profit | Sustainability conditions |

|---|---|---|

| Ms | ||

| [3mm] Mc | ||

| [3mm] | ||

| [3mm] Seq |

Scenario L – Expression of

Appendix C: Graphical representation for decentralized firms

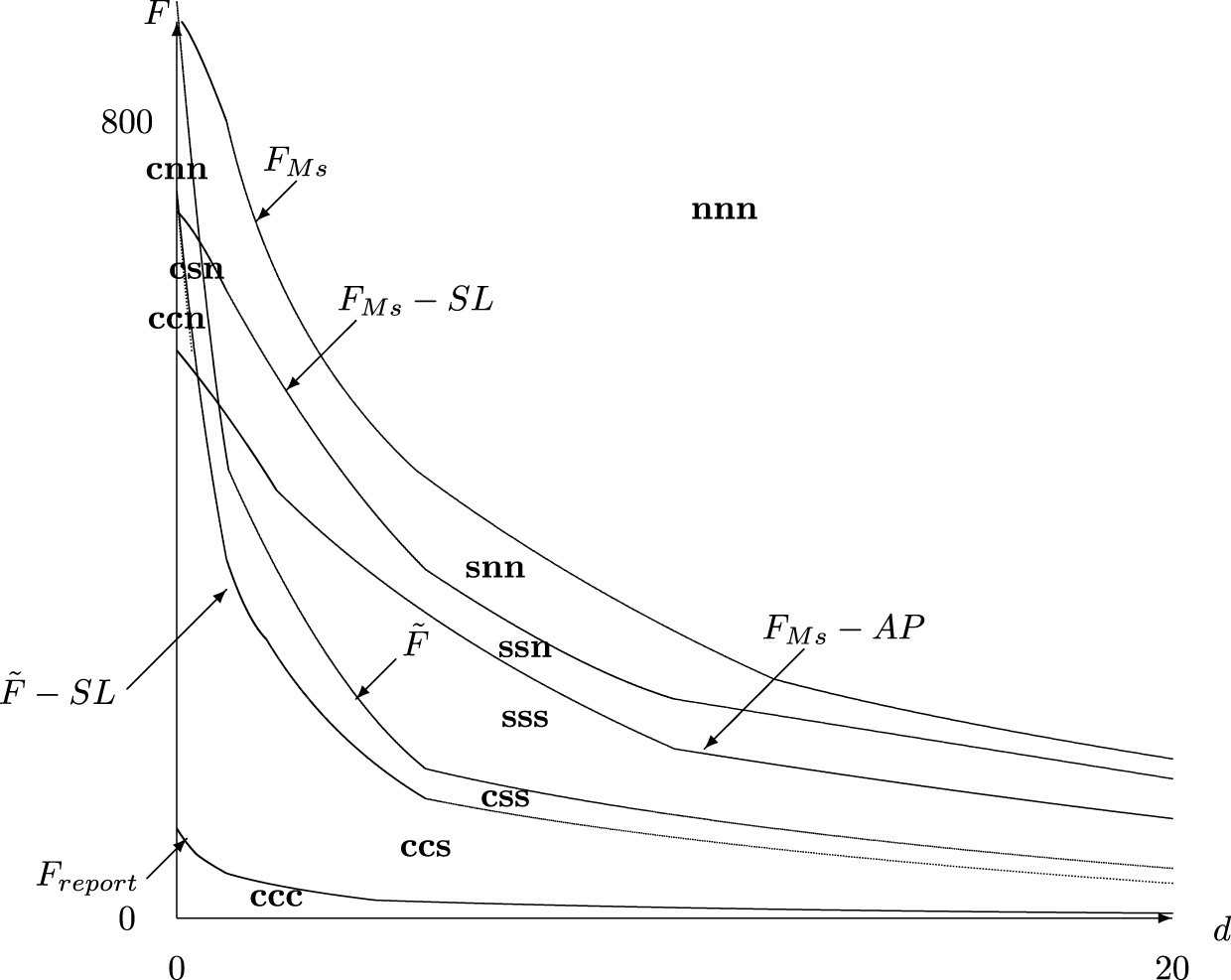

Figure 7 displays collusive strategies of decentralized firms considering µ3 = 0: n: no collusion; s: strategy Ms; c: strategy Mc. The first letter is the strategy without leniency, the second one is the strategy under scenarios S and L and the last one is the strategy under scenarios S + and L +. We plot the border lines without leniency, with simple leniency (-SL) and with amnesty plus (-AP).

Impact of SL and AP on collusive strategies for decentralized firms.

If we focus on the first two letters we identify the following shifts c

Appendix D – Discrepancies between CEO and managers and internal audits

Robustness of previous results Concerning the Mc strategy, each CEO has to decide between applying for leniency (with an immediate decrease in fine of

If a CEO does not intend to request leniency then managers of each division has no reason to do so because they can keep colluding if they don’t cheat and obtain

If

Ineffective audits If

and:

Costly audits If k = 0 firms playing the Ms strategy systematically apply for leniency once the first cartel has been detected. If k > 0 and the other firm does not apply for leniency then firm applies only if

Under the Mc strategy and facing the other firm not applying for leniency a CEO launches an internal audit and applies for leniency if:

An higher value of k yields to an increased value of Freport and makes the Mc strategy easier to sustain.

It is straightforward to see that if a firm benefits from applying for leniency then the other firm benefits too.

This inequality is always checked.

Appendix E – Imperfect detection in the centralization case (

Note that

About the

Threshold values of fines under the different scenarios are reported in the Tables 4 and 5.

Threshold values of fines – Scenarios No leniency, SL-S and SL-L.

| No leniency | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| F2a | |||

| [4mm] F2b | |||

| [4mm] F3 | |||

| [4mm] FUs | |||

| [4mm] FUc | |||

| [4mm] | |||

| [4mm] Freport |

Threshold values of fines – Scenarios AP-S + and AP-L +.

| F2a | ||

| [3mm] F2b | ||

| [3mm] F3 | ||

| [3mm] FUs | ||

| [3mm] FUc | ||

| [3mm] Freport |

References

Aubert, Cécile, Patrick Rey and William E. Kovacic. 2006. “The Impact of Leniency and Whistle-Blowing Programs on Cartels,” 24 International Journal of Industrial Organization 1241–1266.10.1016/j.ijindorg.2006.04.002Search in Google Scholar

BACCARA Mariagiovanna and Heski BAR-ISAAC. 2008. “How to Organize Crime,” 75 Review of Economic Studies 1039–1067.10.1111/j.1467-937X.2008.00508.xSearch in Google Scholar

Bageri Vasiliki, Yannis Katsoulacos and Giancarlo Spagnolo. 2013. “The Distortive Effects of Antitrust Fines Based on Revenue,” 123 Economic Journal 545–557.Search in Google Scholar

Baker Wayne E. and Robert R. Faulkner. 1993. “The Social Organization of Conspiracy: Illegal Networks in the Heavy Electrical Equipment Industry,” 58 American Sociological Review 837–860.10.2307/2095954Search in Google Scholar

Brenner Steffen. 2009. “An Empirical Study of the European Corporate Leniency Program,” 27 International Journal of Industrial Organization 639–645.10.1016/j.ijindorg.2009.02.007Search in Google Scholar

Choi Jay Pil and Heiko Gerlach. 2013. “Multi-Market Collusion with Demand Linkages and Antitrust Enforcement, 61 Journal of Industrial Economics 987–1022.10.1111/joie.12041Search in Google Scholar

Connor John M. 1997. “The Global Lysine Price-Fixing Conspiracy of 1992–1995,” 19 Review of Agricultural Economics 412–427.10.2307/1349749Search in Google Scholar

Dargaud Emilie and Armel Jacques. 2015a. “Endogenous Firms’ Organization, Internal Audit and Leniency Programs,” WP Gate 1524, September.10.2139/ssrn.2660777Search in Google Scholar

Dargaud Emilie and Armel Jacques. 2015b. “Hidden Collusion by Decentralization: Firm Organization and Antitrust Policy,” 114 Journal of Economics 153–176.Search in Google Scholar

Garoupa Nuno. 2007. “Optimal Law Enforcement and Criminal Organization,” 63 Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 461–474.10.1016/j.jebo.2004.04.010Search in Google Scholar

Hammond Scott D. 2009. “Cornerstones of an Effective Leniency Program, Address at an International Competition Network workshop,” Sydney, Australia (November 22–23, 2004).Search in Google Scholar

Harrington Joseph E.Jr. 2004. “Cartel Pricing Dynamics in the Presence of an Antitrust Authority,” 35 Rand Journal of Economics 651–673.10.2307/1593766Search in Google Scholar

Harrington Joseph E.Jr. 2005. “Optimal Cartel Pricing in the Presence of an Antitrust Authority,” 46 International Economic Review 145–169.10.1111/j.0020-6598.2005.00313.xSearch in Google Scholar

Harrington Joseph E.Jr. 2008. “Optimal Corporate Leniency Programs,” 56 Journal of Industrial Economics 215–246.10.1111/j.1467-6451.2008.00339.xSearch in Google Scholar

Harrington Joseph E.Jr. 2011. “When is an Antitrust Authority not Aggressive Enough in Fighting Cartels?,” 7 International Journal of Economic Theory 39–50.10.1111/j.1742-7363.2010.00148.xSearch in Google Scholar

Harrington Joseph E.Jr. 2013. “Corporate Leniency Programs When Firms Have Private Information: The Push of Prosecution and the Pull of Pre-emption,” 61 Journal of Industrial Economics 1–27.10.1111/joie.12014Search in Google Scholar

Harrington Joseph E.Jr. et Myong-Hun Chang. 2015. “When Can We Expect a Corporate Leniency Program to Result in Fewer Cartels?,” 58 Journal of Law and Economics 417–449.10.1086/684041Search in Google Scholar

Houba Harold, Evgenia Motchenkova and Quan Wen. 2012. “Competitive Prices as Optimal Cartel Prices,” 114 Economics Letters 39–42.10.1016/j.econlet.2011.08.021Search in Google Scholar

Katsoulacos Yannis, Evgenia Motchenkova and David Ulph. 2015. “Penalizing Cartels: The Case for Basing Penalties on Price Overcharge,” 42 International Journal of Industrial Organization 70–80.10.1016/j.ijindorg.2015.07.007Search in Google Scholar

Lefouili Yassine and Catherine Roux. 2012. “Leniency Programs for Multimarket Firms: The Effect of Amnesty Plus on Cartel Formation,” 30 International Journal of Industrial Organization 624–640.10.1016/j.ijindorg.2012.04.004Search in Google Scholar

Marx Leslie M., Claudio Mezzetti and Robert C. Marshall. 2015. “Antitrust Leniency with Multiproduct Colluders,” 7 American Economic Journal: Microeconomics 205–240.Search in Google Scholar

Miller Nathan H. 2009. “Strategic Leniency and Cartel Enforcement,” 99 American Economic Review 750–768.10.1257/aer.99.3.750Search in Google Scholar

Motta Massimo and Michele Polo. 2003. “Leniency Programs and Cartel Prosecution,” 21 International Journal of Industrial Organization 347–379.10.1016/S0167-7187(02)00057-7Search in Google Scholar

Persico Nicola. 2002. “Racial Profiling, Fairness, and Effectiveness of Policing,” 92 American Economic Review 1472–1497.10.1257/000282802762024593Search in Google Scholar

Roux Catherine and Thomas Von Ungern-Sternberg. 2007. Leniency Programs in a Multimarket Setting: Amnesty Plus and Penalty Plus. Cahiers de Recherches Economiques du Département d’économie 07.03, Université de Lausanne, Faculté des HEC, Département d’économie.Search in Google Scholar

Sauvagnat Julien. 2014. “Are leniency Programs Too Generous?,” 123 Economics Letters 323–326.10.1016/j.econlet.2014.03.015Search in Google Scholar

Sauvagnat Julien. 2015. “Prosecution and Leniency Programs: The Role of Bluffing in Opening Investigations,” 63 Journal of Industrial Economics 313–338.10.1111/joie.12072Search in Google Scholar

Snyder Christopher M. 1996. “A Dynamic Theory of Countervailing Power,” 27 Rand Journal of Economics 747–769.10.2307/2555880Search in Google Scholar

Souam Saïd. 2001. “Optimal Antitrust Policy Under Different Regimes of Fines, 19 International Journal of Industrial Organization 1–26.10.1016/S0167-7187(99)00007-7Search in Google Scholar

Spagnolo Giancarlo. 2004. Divide et impera: Optimal Leniency Programs. CEPR Discussion Paper, No. 4840.Search in Google Scholar

Spagnolo Giancarlo. 2008. “Leniency and Whistleblowers in Antitrust,” in Paolo Buccirossi, ed. Handbook of antitrust economics. Cambridge, MA, MIT Press.Search in Google Scholar

© 2020 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Articles in the same Issue

- Articles

- Two Advantages of the Negligence Rule Over Strict Liability when the Parties are Risk Averse

- Is a ‘Bad Individual’ more Condemnable than Several ‘Bad Individuals’? Examining the Scope-severity Paradox

- Leniency Programs and Cartel Organization of Multiproduct Firms

- Fairness Vs. Economic Efficiency: Lessons from an Interdisciplinary Analysis of Talmudic Bankruptcy Law

- Individual or Enterprise Liability? The Roles of Sanctions and Liability Under Contractible and Non-contractible Safety Efforts

- US State Tort Liability Reform and Entrepreneurship

Articles in the same Issue

- Articles

- Two Advantages of the Negligence Rule Over Strict Liability when the Parties are Risk Averse

- Is a ‘Bad Individual’ more Condemnable than Several ‘Bad Individuals’? Examining the Scope-severity Paradox

- Leniency Programs and Cartel Organization of Multiproduct Firms

- Fairness Vs. Economic Efficiency: Lessons from an Interdisciplinary Analysis of Talmudic Bankruptcy Law

- Individual or Enterprise Liability? The Roles of Sanctions and Liability Under Contractible and Non-contractible Safety Efforts

- US State Tort Liability Reform and Entrepreneurship