Abstract

Mandatory restrictions in employment law, seeking to promote the welfare of workers, are debated fiercely. Proponents argue that they protect workers. Opponents believe that they spawn inefficiency and harm workers. Yet all agree that restrictions trigger such effects only when obeyed. This Article challenges the conviction that the welfare effects of mandatory restrictions depend on obedience. We show experimentally that when restrictions are disobeyed, workers’ reservation wages rise, i. e., workers charge higher wages when offered employment that violates the restrictions. That, in turn, produces welfare effects similar in nature to those produced when restrictions are obeyed. This observation is therefore important to both proponents and opponents of employment regulation. We establish this claim experimentally by measuring the effects of disobeyed restrictions on workers’ reservation wages. We then investigate several hypotheses as to why these effects are generated. Last, we point out that our findings have important implications in other contexts of contractual regulation, such as in the domain of consumer protection.

Appendix: The Effect of Rising Reservation Wages on Welfare

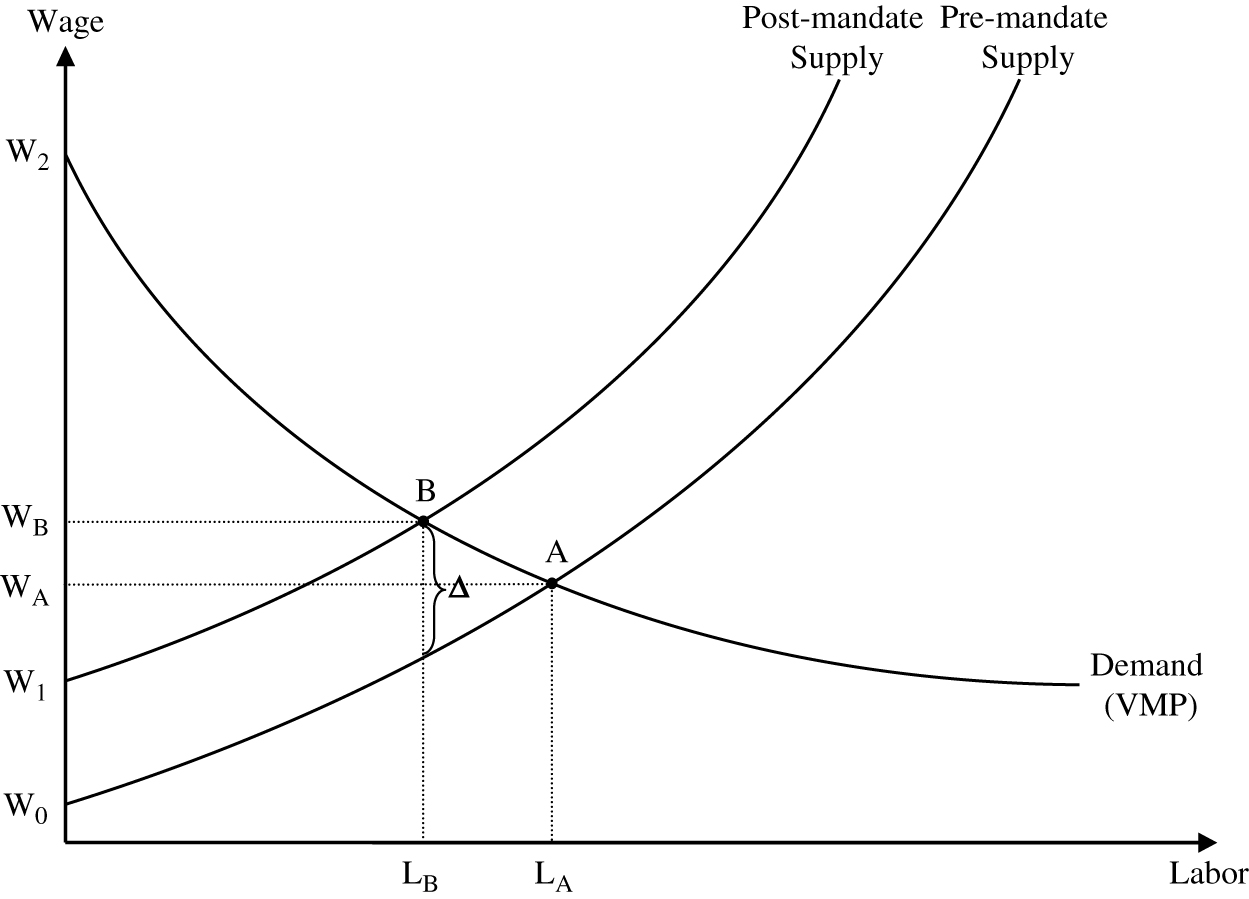

The experimental part of this paper establishes that a mandatory restriction on working hours causes workers’ reservation wages to rise, even if the restriction is unenforced. In this part we establish the economic argument that this effect will leave both workers and employers worse off.

The value of an employment relationship is given by the difference between the employer’s benefit from work, and the worker’s disutility from performing it. Rising reservation wages imply a rise in workers’ disutility, and hence a reduction in the joint value of employment. As long as neither party holds absolute bargaining power, both parties will have to bear some of the loss. Hence, as the pie becomes smaller, the welfare of both parties will fall. Similarly to the imposition of a tax, the division of losses will depend on the relative elasticities of supply and demand.

The diagram above portrays this point graphically. The notion that neither party carries absolute bargaining power is reflected in the standard assumptions of a downward sloping demand and an upward sloping supply. When workers’ disutility from work rises, supply is shifted upwards. The added disutility is represented by the vertical distance between the two curves, denoted Δ. As disutility from work rises, it is easy to verify that the joint gains from employment will fall, and so will the welfare of employers.

Less obvious is the decline in workers’ welfare: although workers’ welfare is lowered by the added disutility from work, it is also enhanced by the higher wages they extract in equilibrium. However, the rise in wages does not fully compensate for the rise in disutility. Whereas disutility rises by Δ, the wage rises merely by

To establish these points formally, consider supply and demand functions,

Notice that

As

To establish that welfare will also decline for workers who continue to be employed, we next show that wages will increase by less than the rise in reservation wages, i. e., that

.

The left-hand side is positive because

Acknowledgments

For helpful comments and discussions we wish to thank Assaf Ben Shoham, Edo Eshet, Guy Davidov and Yehonatan Givati. We are also very grateful to Stav Cohen, Haggai Porat and Shir Shrem for excellent assistance in research.

References

Andreoni, J. 1990. “Impure Altruism and Donations to Public Goods: A Theory of Warm-Glow Giving,” 100 The Economic Journal 464.10.2307/2234133Search in Google Scholar

Bernhardt, A., S. McGrath, and J. DeFilippis. 2007. Unregulated Work in the Global City: Employment and Labor Law Violations in the Global City. New York: Brennan Center for Justice, New York University School of Law.Search in Google Scholar

Bernhardt, A., and S. McGrath. 2005. “Trends in wage and hour enforcement by the US Department of Labor,” Economic Policy Brief, Brennan Center for Justice. 1975–2004.Search in Google Scholar

Bernhardt, A., M.W. Spiller, and N. Theodore. 2013. “Employers Gone Rogue: Explaining Industry Variation in Violations of Workplace Laws,” 66 Industrial Laboratory Related Reviews 808.10.1177/001979391306600404Search in Google Scholar

Boeri, T., and J. Van Ours. 2008. The Economics of Imperfect Labor Markets. Princeton: Princeton Univ. Press.Search in Google Scholar

Casari, M., and L. Luini. 2012. “Peer Punishment in Teams: Expressive or Instrumental Choice?,” 15 Experimental Economics 241.10.1007/s10683-011-9292-6Search in Google Scholar

Davidov, G. 2010. “The Enforcement Crisis in Labour Law and the Fallacy of Voluntarist Solutions,” 26 International Journal of Comparative Labour Law and Industrial Relations 61.10.54648/IJCL2010005Search in Google Scholar

Duersch, P., and J. Müller. 2010. “Taking Punishment into Your Own Hands: An Experiment on the Motivation Underlying Punishment,” Discussion Paper No. 501, University of Heidelberg, Department of Economics, Heidelberg.Search in Google Scholar

Epstein, R.A. 1994. “The Moral and Practical Dilemmas of an Underground Economy,” 103 Yale Law Journal 2157.10.2307/797043Search in Google Scholar

Falk, A., E. Fehr, and C. Zehnder. 2006. “Fairness Perceptions and Reservation Wages: The Behavioral Effects of Minimum Wage Laws,” 121 Quarterly Journal of Economics 1347.10.1093/qje/121.4.1347Search in Google Scholar

Fehr, E., and S. Gächter. 2000. “‘Cooperation and Punishment in Public Goods Experiments,” 90 American Economics Reviews 980.10.1257/aer.90.4.980Search in Google Scholar

Ford, R.T. 2011. “Discounting Discrimination: Dukes V. Wal-Mart Proves that Yesterday’s Civil Rights Laws Can’t Keep up with Today’s Economy,” 5 Harvard Law and Policy Reviews 69.Search in Google Scholar

Fox, D., and C.L. Griffin, Jr. 2009. “Disability-Selective Abortion and the Americans with Disabilities Act,” 2009 Utah Law Reviews 845.Search in Google Scholar

Frank, R.H. 2011. The Darwin Economy: Liberty, Competition and the Common Good. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Glynn, T.P. 2011. “Taking the Employer Out of Employment Law?: Accountability for Wage and Hour Violations in an Age of Enterprise Disaggregation,” 5 Employee Rights and Employment Policy Journal 101.Search in Google Scholar

Gornick, J.C., and M.K. Meyers. 2003. Families that Work: Policies for Reconciling Parenthood and Employment. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.Search in Google Scholar

Gruber, J. 1994. “The Incidence of Mandated Maternity Benefits,” 84 American Economics Reviews 622.Search in Google Scholar

Hahn, R.W., and R.N. Stavins. 2011. “The Effect of Allowance Allocations on Cap-And-Trade System Performance,” 54 Journal Law Economics 267.10.3386/w15854Search in Google Scholar

Henrich, J., R. McElreath, A. Barr, J. Ensminger, C. Barrett, A. Bolyanatz, J.C. Cardenas, M. Gurven, E. Gwako, N. Henrich, C. Lesorogol, F. Marlowe, D. Tracer, and J. Ziker. 2006. “Costly Punishment Across Human Societies,” 312 Science 1767.10.1126/science.1127333Search in Google Scholar

Jolls, C. 2006. “Law and the Labor Market,” 2 Annals Reviews Law and Social Sciences 359.10.1146/annurev.lawsocsci.2.081805.105925Search in Google Scholar

Jolls, C. 2007. “Behavioral Law and Economics,” in P. Diamond and H. Vartiainen, eds.. Economic Institutions and Behavioral Economics. Princeton: Univ. Press.10.3386/w12879Search in Google Scholar

Jolls, C., and C. Sunstein. 2006. “The Law of Implicit Bias,” 94 California Law Review 969.10.2307/20439057Search in Google Scholar

Jolls, C., C.R. Sunstein, and R. Thaler. 1998. “A Behavioral Approach to Law and Economics,” 50 Stanford Law Review 1471.10.1017/CBO9781139175197.002Search in Google Scholar

Kahneman, D. 1992. “Reference Points, Anchors, Norms, and Mixed Feelings,” 51 Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 296.10.1016/0749-5978(92)90015-YSearch in Google Scholar

Kahneman, D., J.L. Knetsch, and R. Thaler. 1986. “Fairness as a Constraint on Profit Seeking: Entitlements in the Market,” 76 American Economics Reviews 728.10.2307/j.ctvcm4j8j.13Search in Google Scholar

Kahneman, D., J.L. Knetsch, and R. Thaler. 1990. “Experimental Tests of the Endowment Effect and the Coase Theorem,” 98 Journal of Political Economy 1325.10.1086/261737Search in Google Scholar

Kahneman, D., and A. Tversky. 1979. “Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision under Risk,” 47 Econometrica: Journal of the Econometric Society 263.10.21236/ADA045771Search in Google Scholar

Kim, P. 1997. “Bargaining with Imperfect Information: A Study for Worker Perceptions of Legal Protection in an At-Will World,” 83 Cornell Law Reviews 105.Search in Google Scholar

Llewellyn, K. 1930. “A Realistic Jurisprudence: The Next Step,” 30 Columbia Law Review 431.10.2307/1114548Search in Google Scholar

Massaro, T. 1991. “Shame Culture and American Criminal Law,” 89 Michigan Law Review 1889.10.2307/1289392Search in Google Scholar

McAdams, R. 2015. Expressive Powers of Law: Theories and Limits. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univ. Press.10.4159/harvard.9780674735965Search in Google Scholar

Meyer, J., and R. Greenleaf. 2011. Enforcement of State Wage and Hour Laws: A Survey of State Regulators. New York: Columbia Law School National State Attorneys General Program.Search in Google Scholar

Mudambi, S.M. 1996. “The Games Retailers Play,” 12 Journal of Asset Management 695.10.1080/0267257X.1996.9964447Search in Google Scholar

Ostrom, E., J. Walker, and R. Gardner. 1992. “Covenants with and without a Sword: Self-Governance Is Possible,” 86 American Political Science Review 404.10.2307/1964229Search in Google Scholar

Ouss, A., and A. Peysakhovich. 2015. “When Punishment Doesn’t Pay: Cold Glow and Decisions to Punish,” 58 Journal Law Economics 625.10.1086/684229Search in Google Scholar

Palfrey, T., and J. Prisbrey. 1997. “Anomalous Behavior in Public Goods Experiments: How Much and Why?,” 87 American Economics Reviews 829.Search in Google Scholar

Poindexter, G.C. 1998. “Light, Air, or Manhattanization?: Communal Aesthetics in Zoning Central City Real Estate Development,” 78 Boston University Law Review 445.Search in Google Scholar

Schurr, A., B. Mellers, and I. Ritov. manuscript. “Selling and Buying Labor: The Effect of Reference Points on Labor Valuations.”Search in Google Scholar

Schwab, S. 1988. “A Coasian Experiment on Contract Presumptions,” 17 Journal of Legal Studies 237.10.1086/468129Search in Google Scholar

Stake, J.E. 2001. “The Uneasy Case for Adverse Possession,” 89 Georgetown Law Journal 2419.Search in Google Scholar

Summers, L.H. 1989. “What Can Economics Contribute to Social Policy?: Some Simple Economics of Mandated Benefits,” 79 American Economics Reviews 177.Search in Google Scholar

Sunstein, C.R. 2001. “Human Behavior and the Law of Work,” 87 Virginia Law Reviews 205.10.2307/1073888Search in Google Scholar

Sunstein, C.R. 2002. “Switching the Default Rule,” 77 New York University Law Review 106.10.2139/ssrn.255993Search in Google Scholar

Sunstein, C.R. 2007. “Cost-Benefit Analysis without Analyzing Costs or Benefits: Reasonable Accommodation, Balancing, and Stigmatic Harms,” 74 University of Chicago Law Review 1895.Search in Google Scholar

Sunstein, C.R., D.A. Schkade, and D. Kahneman. 2000. “Do People Want Optimal Deterrence?,” 29 Journal of Legal Studies 237.10.7208/chicago/9780226780160.003.0012Search in Google Scholar

Thaler, R.H.. 1980. “Toward a Positive Theory of Consumer Choice,” 1 Journal Economics Behavioral Organization 39.10.1017/CBO9780511803475.016Search in Google Scholar

Thaler, R.H. 1995. “Anomalies: Ultimatums, Dictators and Manners,” 9 Journal of Economic Perspectives 209.10.1257/jep.9.2.209Search in Google Scholar

Udry, C. 2006. “Child Labor,” in A. Vinayak Banerjee, R. Benabou and D. Mookherjee, eds.. Understanding Poverty. New York: Oxford Univ. Press, 243–258.10.1093/0195305191.003.0016Search in Google Scholar

Veblen, T. 1899. The Theory of the Leisure Class. New York: Macmillan.Search in Google Scholar

Verkerke, J.H. 1995. “An Empirical Perspective on Indefinite Term Employment Contracts: Resolving the Just Cause Debate,” 4 Wisconsin Law Reviews 837.Search in Google Scholar

Weil, D., and A. Pyles. 2005. “Why Complain?: Complaints, Compliance, and the Problem of Enforcement in the U.S. Workplace,” 27 Comparative Labor Law and Policy Journal 59.Search in Google Scholar

Weiss, D. 1991. “Paternalistic Pension Policy, Psychological Evidence and Economic Theory,” 58 University of Chicago Law Review 1275.10.2307/1599980Search in Google Scholar

Wittlin, M. 2011. “Buckling under Pressure: An Empirical Test of the Expressive Effects of Law,” 28 Yale Journal on Regulation 419.Search in Google Scholar

Zatz, N.D. 2008. “Working beyond the Reach or Grasp of Employment Law,” in A. Bernhardt, H. Boushey, L. Dresser and C. Tilly, eds. The Gloves-Off Economy: Workplace Standards at the Bottom of America’s Labor Market. New York: Cornell University Press, 33–64.Search in Google Scholar

© 2017 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Articles in the same Issue

- Testing the Endowment Effect for Default Rules

- Imperfect Credit Markets and Crime

- Corruption, Income and Piracy. An empirical analysis

- US Interstate Underground Trade Flow: A Gravity Model Approach

- Shrinkage Estimation in the Adjudication of Civil Damage Claims

- On the Economic Effects of Disobeyed Regulation in Employment Law

- Constitutional Judicial Behavior: Exploring the Determinants of the Decisions of the French Constitutional Council

- What Can We Make of Unsubstantiated Child Abuse Reports? A New Approach

- An Assessment of Carousel Value-Added Tax Fraud in The European Carbon Market

Articles in the same Issue

- Testing the Endowment Effect for Default Rules

- Imperfect Credit Markets and Crime

- Corruption, Income and Piracy. An empirical analysis

- US Interstate Underground Trade Flow: A Gravity Model Approach

- Shrinkage Estimation in the Adjudication of Civil Damage Claims

- On the Economic Effects of Disobeyed Regulation in Employment Law

- Constitutional Judicial Behavior: Exploring the Determinants of the Decisions of the French Constitutional Council

- What Can We Make of Unsubstantiated Child Abuse Reports? A New Approach

- An Assessment of Carousel Value-Added Tax Fraud in The European Carbon Market