Abstract

Ketone therapies refer to metabolic interventions aimed to elevate circulating levels of ketone bodies (KB), either through direct supplementation or stimulating endogenous production via medium-chain fatty acids intake, ketogenic diets, caloric restriction, intermittent fasting, or exercise. These strategies have gained attention as potential treatments for neurodegenerative diseases by preserving neuronal function, improving metabolic efficiency, and enhancing cellular resilience to stress. KB are taken up and metabolized by various brain cell types–including neurons, astrocytes, oligodendroglia and microglia–under basal and pathological conditions. However, their cell-type-specific effects remain incompletely understood. Notably, although astrocytes play a key role in supporting neuronal metabolism and can both produce and utilize KB, research has focused predominantly on neuronal responses, leaving the impact of ketotherapeutics on astrocytes relatively unexplored. This review aims to compile and discuss current evidence concerning astrocytes responses to both exogenous and endogenous ketotherapeutic strategies. Although still limited, available studies reveal that astrocytes undergo dynamic changes in response to these interventions, including morphological remodeling, calcium signaling modulation, transcriptional and metabolic reprogramming, regulation of transporters, and neurotransmitter uptake–a crucial process for synaptic function. Astrocytes appear to actively contribute to the neuroprotective and pro-cognitive effects of ketone therapies, particularly in the context of aging and disease. However, significant gaps still remain, concerning the stage when ketone therapy should be initiated, the underlying mechanisms, regional specificity, and long-term consequences. Future research focused on astrocyte heterogeneity, activation of intracellular pathways, and metabolic and transcriptional reprogramming will enable the translational potential of astrocyte-targeted ketone therapies for neurological disorders.

1 Introduction

Ketone bodies (KB) are used in brain as an efficient alternative energy source to glucose under nutrient limiting conditions. During development, KB blood levels are up to 10 times higher than in the adult stage (Page et al. 1971), and they are used for energy metabolism as well as precursors for lipids and myelin synthesis (DeVivo et al. 1976; Krebs et al. 1971; Reichard et al. 1974; Robinson and Williamson 1980; Yeh et al. 1977). KB are produced in liver mitochondria through the β-oxidation of fatty acids in a process known as ketogenesis. They are released to the bloodstream and uptaken in target organs, as the heart, muscle and brain, where they are converted to acetyl-CoA to generate ATP through the tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA) (Camberos-Luna and Massieu 2020). KB include beta-hydroxybutyrate (BHB), acetoacetate (AcAc) and acetone, and among the three of them, BHB and AcAc are the most metabolically relevant since acetone, as a volatile molecule, is eliminated through exhalation. BHB is the main KB due to its higher concentration in blood.

Ketotherapeutics or ketogenic therapies refer to interventions aimed to elevate KB in blood to be used as cytoprotective molecules against diverse pathological conditions. Ketotherapeutics can be endogenous or exogenous, depending on the strategy used to increase KB levels. Endogenous ketotherapeutics involve stimulating KB production endogenously through dietary approaches such as the ketogenic diet (KD), caloric restriction (CR) and intermittent fasting (IF), or by exhaustive exercise. These approaches require chronic treatments to stimulate liver ketogenesis. Exogenous ketotherapeutics involve the external administration of KB via intravenous, enteral or oral intake of ketone salts or ketone esters (KE). These approaches lead to a rapid elevation of ketones but require repeated doses to sustain ketosis (Camberos-Luna and Massieu 2020).

Previous reviews have discussed the effectiveness of different ketotherapeutic approaches for the treatment of acute brain injury and neurodegenerative diseases, as well as the potential mechanisms involved (Camberos-Luna and Massieu 2020; Koppel and Swerdlow 2018). However, cell-specific responses to keto therapies have not been previously reviewed. KB are uptaken and metabolized by different cell types in brain, including neurons, astrocytes and oligodendrocytes (Andersen et al. 2022; Edmond et al. 1987; McKenna et al. 1993), under both basal and pathological conditions (Scafidi et al. 2022); however, KB effects in distinct cell populations have not been completely elucidated. Astrocytes play a key role in providing metabolic and structural support to neurons (Beard et al. 2022; H. G. Lee et al. 2022). They regulate energy metabolism (Attwell and Laughlin 2001; Pellerin and Magistretti 1994; A. Suzuki et al. 2011; Takano et al. 2006), participate in tissue repair after central nervous system (CNS) injury (Faulkner et al. 2004; Okada et al. 2006), participate in the control of extracellular K+ concentration (Hu et al. 2019), synaptic function (Adamsky et al. 2018; Chung et al. 2015; Martín et al. 2015; Yu et al. 2018), exert antioxidant actions through glutathione (GSH) production (Dringen and Arend 2025; Dringen and Hamprecht 1996, 1998), are responsible for lipid synthesis and metabolism (J. A. Lee et al. 2021; Nieweg et al. 2009) and synthesis and removal of neurotransmitters from the extracellular space (Daikhin and Yudkoff 1998; Danbolt 2001; Duan et al. 1999; Schousbe and Waagepetersen 2005). Additionally, astrocytes can produce KB further highlighting their relevance in brain energy metabolism. Thus, the aim of the present review is to compile and discuss the reported evidence on the effects of different keto therapies on astrocytes, expecting that this information will be useful for developing and improving future ketotherapeutic strategies.

2 Astrocytes as KB producers

KB production or ketogenesis primarily occurs in liver mitochondria, however, in the CNS, astrocytes can also produce KB, albeit at lower levels (Auestad et al. 1991; Puchalska and Crawford 2017). Besides KB metabolic role in ATP production, KB serve, though to a lesser extent, as precursors for the synthesis of fatty acids and cholesterol (Lopes-Cardozo et al. 1986; Nieweg et al. 2009). In hepatocytes, ketogenesis is activated when acetyl-CoA accumulates as a result of fatty acid β-oxidation, exceeding the capacity of the TCA cycle. The excess acetyl-CoA is then redirected toward the synthesis of KB or cholesterol. The classical ketogenesis pathway initiates with the condensation of two molecules of acetyl-CoA, catalyzed by the enzyme thiolase, to form acetoacetyl-CoA. A third acetyl-CoA molecule is then added by hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA synthase (HMG-CoA synthase), producing β-hydroxy-β-methylglutaryl-CoA (HMG-CoA), which is the rate-limiting step of the pathway. HMG-CoA is subsequently cleaved by HMG-CoA lyase to generate AcAc and a free acetyl-CoA molecule. AcAc can be reduced to BHB by the enzyme β-hydroxybutyrate dehydrogenase 1 (BHD1) in a NADH-dependent reaction or undergo spontaneous non-enzymatic decarboxylation to form acetone, a volatile compound excreted through the lungs (Nuwayhid et al. 1988).

Astrocytes are also capable of producing KB, particularly form oxidation of fatty acids such as palmitate. In this context, approximately 90 % of metabolic products are KB, with CO2 representing only around 10 % (Blázquez et al. 1998). Notably, more than 85 % of the total KB formed in astrocytes consist of AcAc (Auestad et al. 1991). However, unlike hepatocytes, astrocytes do not appear to rely on the canonical HMG-CoA synthase pathway. Instead, research suggests that astrocytic ketogenesis proceeds through alternative mechanisms. One proposed pathway involves the enzyme succinyl-CoA:3-oxoacid-CoA transferase (SCOT), whose expression is upregulated in astrocyte cultures treated with BHB under glucose- and serum-deprived conditions (Suzuki et al. 2009). Another potential pathway involves acetoacetyl-CoA deacylase, which acts directly on acetoacetyl-CoA – an intermediate derived from the β-oxidation – to produce AcAc (Auestad et al. 1991). Further supporting the existence of a non-canonical pathway, astrocytes derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSC) have been shown to express HMG-CoA lyase but not HMG-CoA synthase (Thevenet et al. 2016). This molecular evidence reinforces the idea that astrocytes produce KB via an alternative route that bypasses the classical hepatic enzymes.

Altogether, these findings underscore the metabolic versatility of astrocytes and their potential contribution to brain energy homeostasis. The ability to produce KB suggests an important role for astrocytes in supporting neuronal function during energy stress, with possible implications for neuroprotection and metabolic adaptations.

3 Exogenous KB exposure to astrocytes

3.1 Efficiency of KB metabolism in astrocytes compared to neurons and substrate preference

During physiological conditions, both astrocytes and neurons are capable of metabolizing KB (Figure 1(1)), but their relative efficiency has been a subject of debate. Early studies suggested that astrocytes in culture metabolize AcAc at a rate four times higher than neurons after 8 h exposure to 0.5–1.0 mM, as measured by CO2 production, but AcAc oxidation is lower than glucose. Cultured neurons also metabolize AcAc, and the CO2 production rate is two times higher than that of glucose in this type of cells (Lopes-Cardozo et al. 1986). Other studies in pure cell preparations, and cell cultures from astrocytes, neurons and oligodendrocytes, reported that the ketolytic enzymes – SCOT, acetoacetyl-CoA thiolase and BHD – exhibit higher activity in astrocytes than neurons and oligodendrocytes, particularly during early stages of development as enzyme activity decreases with maturation (Chechik et al. 1987; Poduslo 1989). These results suggest that astrocytes actively metabolize KB, as previously suggested by Lopes-Cardozo et al. 1986. In astrocytes, AcAc also serves for the synthesis of lipids and cholesterol (Lopes-Cardozo et al. 1986).

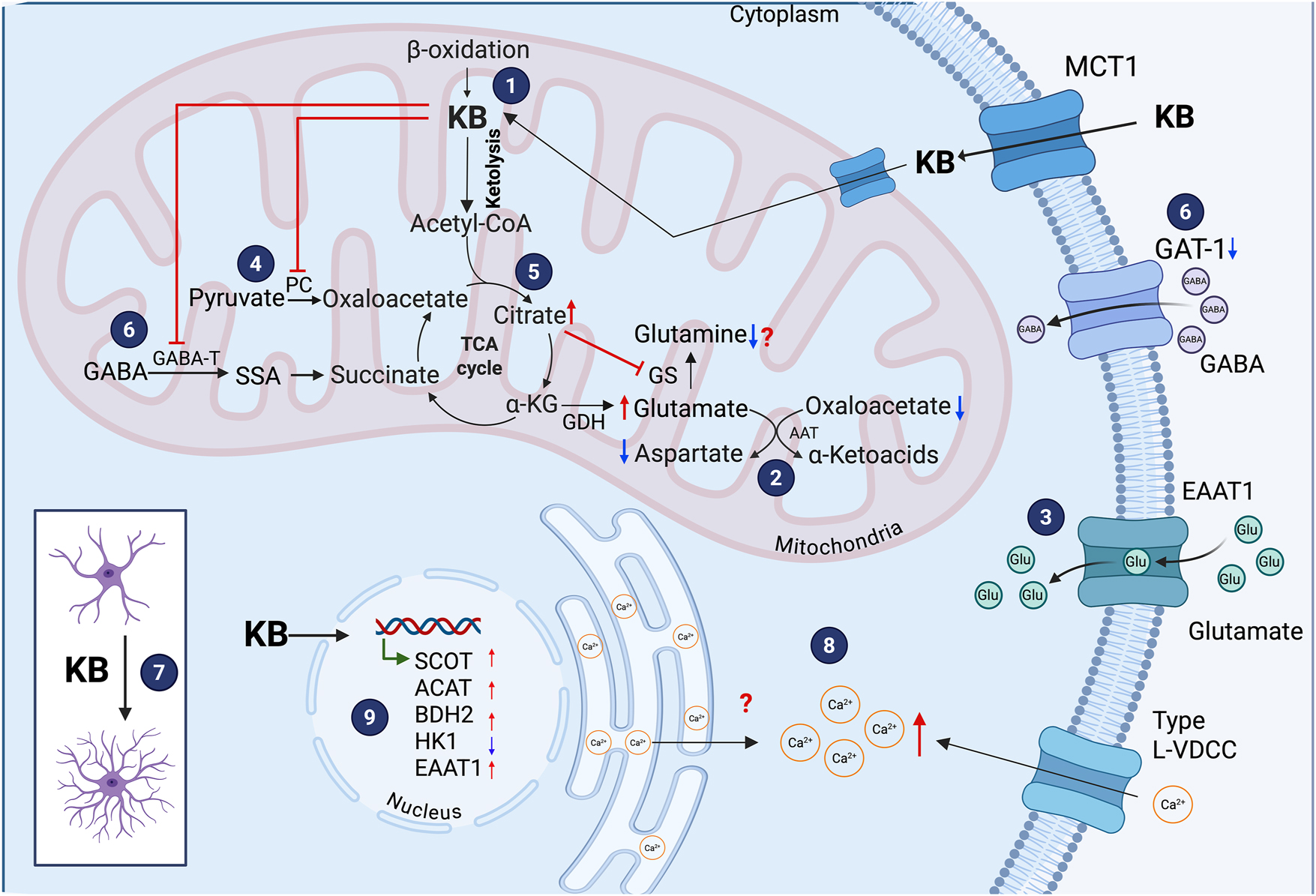

Effects of ketone bodies (KB) on astrocytes. Astrocytes can metabolize KB, although less efficiently than neurons (1). In astrocytes, β-hydroxybutyrate (BHB) decreases intracellular aspartate and increases glutamate levels due to decreased transamination reaction of aspartate (2). BHB elevates astrocytic glutamate uptake (3). KB inhibits pyruvate carboxylase (4) and reduce intracellular glutamine levels, likely due to elevated citrate concentrations (5). BHB also suppresses the expression and activity of GABA-transaminase (GABA-T), and decrease GAT-1 (6). BHB promotes a morphological transformation in astrocytes from a polygonal to a stellate shape with increased number of cellular processes (7), and elevates intracellular Ca2+ levels through Type L-VDCC (8). At the molecular level, BHB upregulates the expression of genes encoding succinyl-CoA:3-ketoacid CoA transferase (SCOT), acetoacetyl-CoA thiolase (ACAT), 3-hydroxybutyrate dehydrogenase type 2 (BDH2), and the glutamate transporter EAAT1, while downregulates hexokinase 1 (HK1) (9).

In contrast to the previously described observations, studies by Edmond et al. (1987), suggest that KB are preferentially oxidized in neurons rather than astrocytes. Using primary cultures from neurons, oligodendrocytes and astrocytes from the developing brain, their observations revealed that the three type of cells efficiently metabolize KB in the presence of glucose (incubations with 0.5 mM acetoacetate and 1.0 mM BHB for 3 h in the presence of 1.2 mM glucose), but consumption by neurons and oligodendrocytes was about three times more efficient than in astrocytes, as assessed by CO2 production. This correlated with a higher activity in neurons of the ketolytic enzyme SCOT (Edmond et al. 1987). In addition, the results from this study suggest that KB are better substrates for respiration than glucose in the three types of cells, but glucose consumption for respiration is higher in neurons and oligodendrocytes relative to astrocytes. Results also suggest that astrocytes preferentially metabolize KB rather than glucose, with no significant differences in the metabolism of AcAc and BHB. Discrepancies between these observations and those of previous studies (Chechik et al. 1987; Lopes-Cardozo et al. 1986; Poduslo 1989) might be related to differences in the preparations used and experimental conditions. In Lopes-Cardozo’s study, metabolic measurements were performed in cells attached to cultured flasks after long exposure times (8 h), while Edmond et al. (1987) used shorter incubation times (1–3 h) and measurements were performed in cell suspensions. On the other hand, the state of maturation of cells might influence their ketolytic activity as suggested by Chechik et al. (1987).

A more recent study used Föster resonance energy transfer (FRET) nanosensors for glucose and pyruvate to monitor metabolic activity in mixed neuronal/glial cultures, organotypic hippocampal slices, and acute hippocampal slices prepared from fasted ketotic mice (36 h food-deprived) (Valdebenito et al. 2016). In line with Edmond’s observations, it was reported that chronic exposure of cultured cells and brain slices to BHB (2 mM for 3 days), led to decreased glucose consumption and enhanced pyruvate oxidation in astrocytes, suggesting that KB inhibit glycolysis and stimulates mitochondrial oxidative metabolism in these cells. Furthermore, astrocytes in brain slices obtained from ketotic mice, also showed decreased glucose consumption. These results suggest that astrocytes use BHB to support mitochondrial metabolism, possibly sparing glucose for neuronal consumption. However, the effects of BHB on astrocytes were not compared to those in neurons.

A recent transcriptomic analysis showed that in human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) differentiated either to neurons or astrocytes, the mitochondrial enzymes SCOT1, SCOT2 and BDH1 are highly expressed in neurons, whereas BDH2, the cytosolic isoform, is enriched in astrocytes, suggesting that neurons possess a higher capacity for mitochondrial ketolytic metabolism (Thevenet et al. 2016). Other recent observations in mouse cortical slices using [U-13C]-BHB (1 h at 200 mM) and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry are in agreement with Edmond et al. (1987) early observations suggesting that BHB metabolism occurs preferentially in non-astrocytic cells, presumably neurons (Andersen et al. 2022). Additionally, human studies (Pan et al. 2001, 2002) previously suggested that overnight fasting resulted in increased incorporation of [2,4-13C2]-D-BHB into glutamate as compared to glutamine, suggesting a higher consumption of BHB in neurons.

A recent study by York et al. (2024) using mass spectrometry imaging (which combines chemical and spatial resolution with imaging), within the cytoarchitecture of the live hippocampal granular neuronal layer of the GD, reported that in neurons of the DG, BHB (2 mM) is more rapidly and extensively incorporated into the TCA as compared to lactate and pyruvate (2 mM each) in the presence of glucose, possibly due to its rapid conversion to Acetyl-CoA. Also, glucose and BHB are incorporated into glutamate and to a lesser extent into glutamine, although, in these experiments, the contribution of astrocytes to the changes observed could not be discarded. These results led to the conclusion that in the presence of glucose, BHB is metabolized as an energy source through the TCA and also for neurotransmitter synthesis in this hippocampal region, in agreement with the previous studies (Chowdhury et al. 2014; Jiang et al. 2011). When hippocampal slices were stimulated with a depolarizing concentration of KCl, glucose metabolism was favored relative to the other substrates, in agreement with previous studies suggesting that glucose is the main fuel under neuronal activity (Achanta et al. 2017; Chowdhury et al. 2014; Jiang et al. 2011).

Altogether, these studies suggest that KB are better substrates for respiration than glucose, and they can be used as an energy source in neurons, oligodendrocytes and astrocytes during development. Additionally, results suggest that KB are metabolized to a greater extent in neurons than in astrocytes. However, glucose is a preferred energy substrate for neurons as compared to astrocytes, while astrocytes prefer KB upon glucose relative to neurons.

The role of KB on brain metabolism has also been studied in pathological conditions, such as traumatic brain injury. It has been reported that in immature rats (21–22 days-old) BHB infusion (0.2 M) after traumatic brain injury, results in a higher KB metabolism for the synthesis of glutamate in neurons, as compared to glutamine in astrocytes, in the cortico-hippocampal formation (Scafidi et al. 2022). These results are in agreement with previous ex vivo studies suggesting that BHB is used in brain in a large proportion for acetyl-CoA production, accounting for 36–40 % of total substrate oxidation through the TCA. BHB is also used for neurotransmitter synthesis in neurons (glutamate and GABA), and to a lesser extent for glutamine synthesis in astrocytes, as measured by nuclear magnetic resonance spectrometry (NMRS) in cortical tissue from rats infused with [2,4-13C2]BHB and subjected to different protocols of activity (wakefulness, anesthetized and isoelectricity) (Chowdhury et al. 2014; Jiang et al. 2011). Results also suggested that KB do not replace glucose to sustain energy demands during increased neuronal activity (Chowdhury et al. 2014; Jiang et al. 2011). Nonetheless, during hypoglycemic conditions in cortical slices exposed to low glucose (0.4 mM [1-13C]D-glucose) and BHB (0.25–2.5 mM [U-13C]D-BHB) for 90 min, and using NMRS for metabolite determination, an increased production of neuronal neurotransmitters was observed, suggesting that KB are used in neurons to synthesize neurotransmitter during hypoglycemia (Achanta et al. 2017).

The metabolic efficiency of different energy substrates depends on their intracellular and extracellular availability, and this has been studied in competition experiments. For example, under conditions of glucose and serum deprivation, primary cultured astrocytes consume BHB as an alternative energy fuel to glucose after its chronic exposure (10 mM BHB during 5 days), preserving their viability (Y. Suzuki et al. 2009).

Under physiological conditions, when the metabolism of various substrates is evaluated individually in astrocyte primary cultures from rat brain, BHB ranked third in efficiency as compared to glucose, glutamine, lactate and malate, using CO2 production as a metabolic indicator, and a 1 mM concentration of each substrate incubated for 1 h. CO2 production from lactate and BHB was 10-11-fold higher than that of glucose, but lower than that of glutamine, which was the metabolite with the highest CO2 production in astrocytes. In contrast to astrocytes, glucose and lactate consumption was higher in synaptic terminals, and CO2 production from BHB was similar to that of glucose, but lower to glutamine and lactate (McKenna et al. 1993).

When BHB metabolism in astrocytes was assessed competitively with other substrates (glucose, glutamine, lactate and malate at 1 mM concentration each), CO2 production from labeled glutamate was the highest, suggesting its use as an energy substrate in astrocytes, and its metabolism was not altered in the presence of the other substrates. The oxidation of glutamine was higher than that of glucose, lactate, BHB and malate, and inhibited by the addition of glutamate (McKenna 2012). CO2 production from lactate and BHB was similar and substantially higher than that of glucose, and the addition of BHB did not alter CO2 production from glucose or lactate, suggesting they are metabolized in a different compartment. However, BHB consumption was substantially inhibited by glutamate and glutamine, suggesting that endogenously formed glutamate from glutamine and exogenous glutamate enter the same TCA cycle as BHB and compete (McKenna 2012). Overall, these observations suggest that astrocytes can use different substrates to produce energy through the TCA, and that glutamate and glutamine are preferred energy substrates for astrocytes over BHB and lactate.

In summary, the aforementioned observations suggest that the efficiency of KB metabolism in astrocytes is influenced by the availability of alternative substrates, their concentration and treatment duration. This flexibility highlights the metabolic adaptability of astrocytes in response to nutritional status.

On the other hand, KB influence mitochondrial function due to their role in redox balance. Since both BHB and AcAc are substrates and products of BDH, their interconversion affects the cellular NAD(P)H/NAD(P)+ ratio. In particular, it has been observed that BHB administration (at increasing concentration from 1–30 mM, during 50 min) enhances this ratio both in neurons and astrocytes derived from iPSCs, reflecting its mitochondrial oxidation to AcAc via BDH (Thevenet et al. 2016). However, the concentration of D-BHB needed to enhance NAD(P)H production was above 3 mM, which might not be reached in brain after the ketogenic diet or the intake of medium chain fatty acids (MCFA).

BHB oxidation exerts distinct – and in some cases opposite – effects on mitochondrial metabolism in astrocytes and neurons. While chronic exposure (7 days) to 4 mM BHB does not alter basal respiration, extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) or ATP production in primary cultured astrocytes, all these processes are enhanced in primary cultured neurons (Koppel et al. 2023). Additional differences are reported in mitochondrial efficiency. In astrocytes, BHB exposure reduces the proton leak and oxygen consumption, while increasing maximal respiration and the spare respiratory capacity – changes that may reflect an increase in mitochondrial mass. However, this increase does not appear to enhance energy production but may instead support anabolic functions. In contrast, neurons treated with BHB show an increased mitochondrial mass, which might enhance energy production by facilitating the throughput of the respiratory chain (Koppel et al. 2023). These findings support that energy production by BHB is more active in neurons than astrocytes, in agreement with the studies discussed above.

3.2 Astrocyte metabolic changes in response to KB exposure

3.2.1 Effect of KB on astrocytic neurotransmitter metabolism and uptake

Pioneer studies by Yudkoff et al. (1997) reported that AcAc and BHB exposure (5 mM each for 1 h) to cultured astrocytes led to a decrease in aspartate levels, an increase in glutamate content, and no modifications in glutamate uptake. These findings were attributed to a decrease in glutamate transamination, likely due to diminished oxaloacetate levels (Figure 1(2)). Hazen et al. (1997) supported this suggestion, showing that AcAc administration (5 mM) to cultured astrocytes inhibits pyruvate carboxylase (PC) (Figure 1 (4)), lowering oxaloacetate availability and thereby reducing glutamate-to-aspartate transamination (Hazen et al. 1997).

Leite et al. (2004) also found that 5 mM BHB treatment either for 1 or 24 h did not alter glutamate uptake in cultured astrocytes when it was assessed at a single time point, 7 min after BHB exposure, using a highly sensitive radiolabeled [3H] glutamate uptake assay. In contrast, Shang et al. (2024) reported increased glutamate uptake in BHB-treated primary astrocytes (2 mM for 24 h) – as indicated by lower residual glutamate levels in the culture medium at multiple time points (10, 40 and 60 min) – and using a moderately sensitive colorimetric/fluorometric assay – along with elevated mRNA and protein levels of the EAAT1/GLAST glutamate transporter (Figure 1(3, 9)). Increased expression of the glutamate transporter, EAAT1/GLAST, was confirmed in the hippocampus of mice treated with BHB (60 mg/kg for 2 days). These contrasting observations might result from differences in experimental protocols, as exposure times and detection methods. The delayed decrease in extracellular glutamate levels observed by Shang et al. (2024) suggests that BHB may induce transcriptional and translational upregulation of glutamate transporters – a response likely undetectable after 7 min BHB exposure assessed by Leite et al. (2004). However, the precise mechanism underlying the effects of BHB on astrocytic glutamate uptake remains to be elucidated.

Regarding glutamine, Yudkoff et al. (1997) reported opposite effects of AcAc and BHB (5 mM for 1 h) on glutamine levels. While AcAc led to a decrease in intracellular glutamine, attributed to elevated citrate levels, which inhibits glutamine synthetase (GS) activity, BHB incubation resulted in increased glutamine content (Figure 1 (5)).

Importantly, KB inhibit the incorporation of the GABA amino group into glutamine in astrocytes, leading to an expansion of the GABA pool (Yudkoff et al. 1997). In addition, Suzuki et al. (2009), demonstrated that BHB exposure (1–10 mM during 5 days) to astrocyte cultures (without serum and glucose) suppresses the expression and activity of GABA-transaminase (GABA-T) – the enzyme responsible for transferring the GABA amino group into glutamine (Figure 1(6)). Additionally, in the same conditions, BHB reduced the expression of the GABA transporter, GAT-1, responsible for the uptake of GABA into astrocytes and GABAergic synaptic terminals (Figure 1(6)). These findings support the hypothesis that BHB exposure, as the KD, increases GABA concentration suppressing astrocytic GABA degradation and contributing to its antiepileptic effects.

In addition to these neurotransmitter-related effects, BHB exposure may also regulate the secretion of S100β, an astrocyte-derived neurotrophic factor. Leite et al. (2004) observed an early elevation of S100β secretion 1 h after 5 mM BHB exposure to cortical primary cultures of astrocytes, which decreased below basal levels at 24 h. Given that elevated S100β abundance is associated with seizure susceptibility and neuronal damage, these changes may also contribute to the antiepileptic benefits of BHB (Leite et al. 2004).

Together, the observation described above highlight the different metabolic roles of KB in astrocytes and neurons, suggesting that BHB actions extend beyond energy production to influence neurotransmitter metabolism, mitochondrial function and bioenergetic adaptability. Further research is needed to clarify the time- and context-dependent nature of these effects, particularly in relation to neuroprotection and therapeutic applications of KB.

A limitation of the studies discussed above is the high concentrations of KB used, as in most of the studies varied between 1-5 mM or even 10 mM, which are likely not reached in the brain of individuals consuming exogenous ketones or under diet approaches to induce ketosis, as they are rapidly metabolized (Almeida-Suhett et al. 2022; Suissa et al. 2021). On the other hand, cell suspensions, primary cultured cells and cultured cells derived from human iPSCs, might exhibit metabolic differences that may account for the discrepancies observed between the different studies, and might differ from data obtained in more intact preparations as brain slices and in vivo studies.

3.3 Morphologic changes in astrocytes exposed to KB

In addition to metabolic effects, BHB can influence astrocyte morphology as it promotes the transition from a polygonal to a stellate shape characterized by the development of more cellular processes (Figure 1 (7)) (Leite et al. 2004). These changes become evident 6 h post-incubation with 2–10 mM BHB and are reversible after 24 h. This morphologic transformation is possibly mediated by the suppression of RhoA signaling, a pathway involved in cytoskeleton dynamics and the formation of stress fibers. Specifically, the small GTPase, RhoA, is inhibited by BHB (10 mM), as shown by the ability of lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) – a known RhoA activator – to block the BHB-induced morphologic changes (Leite et al. 2004). However, the mechanism involved in RhoA inhibition by BHB is unknown.

Changes in astrocyte morphology induced by BHB might reflect functional alterations, which could, in turn, influence the activity of neighboring neurons, highlighting a broader role for BHB in the regulation of neuroglial interactions. More studies are needed in order to understand the relationship between morphological changes in astrocytes and the benefits of KB in brain.

3.4 Effect of KB on astrocytic calcium concentration

Exposure of glial cells to 5 and 10 mM BHB leads to elevated cytosolic Ca2+ levels (Figure 1 (8)) (Xiao et al. 2007). This increase is observed even in Ca2+/Mg2+-free medium, indicating the contribution of intracellular Ca2+ pools to this response. However, the application of nitrendipine, an L-type voltage-dependent Ca2+ channel blocker, completely abolished the maximal calcium fluorescent signal, suggesting that BHB-induced cytosolic Ca2+ elevation is likely mediated by extracellular Ca2+ influx through these channels (Xiao et al. 2007). Further studies are required to elucidate the mechanisms and sources of intracellular Ca2+ mobilization triggered by BHB.

3.5 Gene and protein expression in astrocytes exposed to KB

There is evidence of gene and protein expression modifications in astrocytes incubated with BHB (Figure 1 (9)). In astrocyte cultures maintained under glucose- and serum-free medium, 10 mM BHB altered the expression of genes related to glycolysis and KB metabolism, decreasing hexokinase I – an enzyme that catalyzes the first irreversible reaction in glycolysis – while increasing SCOT expression (Suzuki et al. 2009). Furthermore, after a 3-h exposure to 2 mM BHB, 176 genes were differentially expressed in astrocytes, with Slc1a3 (EAAT1/GLAST) showing the most significant change. Protein analysis confirmed EAAT1/GLAST upregulation, which was also observed in vivo in BHB-treated mice (intragastric administration of 60 mg/kg for 2 days), demonstrating increased EAAT1/GLAST expression in the hippocampus (Shang et al. 2024).

Additionally, exposure of astrocytes to 2 mM BHB for 24 h was reported to support neuronal survival under conditions of glutamate toxicity in co-cultures of neurons and astrocytes (Shang et al. 2024). The upregulation of EAAT1/GLAST prompted further investigation on changes in glutamate uptake and the possible regulatory pathways. A trend toward enhanced glutamate uptake was observed, accompanied by the upregulation of EAAT1/GLAST mediated by CAMKII activation, whose phosphorylation augments after 1 h incubation with 2 mM BHB- likely through increased Ca2+ levels via L-type calcium channels. CAMKII phosphorylates EAAT1/GLAST increasing its activity (Chawla et al. 2017), thereby BHB possibly modulates both EAAT1/GLAST expression and activity (Shang et al. 2024).

3.6 Effect of KB administration on astrocytes under pathological conditions

The effect of BHB administration on astrocytes under pathologic or stressful conditions has been reported and is often related to changes in the expression of proteins involved in key astrocytic functions. In an animal model of focal ischemia, where astrogliosis is characterized by increased GFAP levels, injection of BHB (500 mg/kg i.p.) 1 h after injury reduced astrogliosis and GFAP expression in the perilesional cortex (Bazzigaluppi et al. 2018). Similarly, in a model of heat stress-induced neuroinflammation, BHB administration (200 mg/kg/day 1 h before heat stress, for 14 days) decreased the number of GFAP-positive cells in the hippocampal ventral CA1. Interestingly, BHB also increased the number of terminal astrocytic endfeet without affecting astrocyte density or area–both of which were reduced following heat stress (J. Huang et al. 2022). These observations suggest that BHB treatment might partially inhibit astrocyte reactivity under stress conditions. In another study using a rat model of painful diabetic neuropathy, BHB administration (i.p. injection of 291 mg/kg during 28 days) increased paw withdrawal, used as an index of mechanical allodynia, and restored the elevated the expression of aquaporin-4 (AQP4) in the spinal cord, a water channel protein located at astrocytes endfeet, which is involved in the glymphatic system implicated in the excretion of metabolic waste products in the nervous system (Benveniste et al. 2017). BHB treatment also restored the decreased levels of α-syntrophin (SNTA1), a protein involved in anchoring AQP4 in the plasma membrane of astrocytes facing blood vessels (Wang et al. 2022). Results suggested that BHB treatment recovered the perivascular localization of AQP4 in the spinal glymphatic system, through the upregulation of SNTA1, and the downregulation AQP4, possibly mediated by the inhibition of histone deacetylase 1 (HDAC1), as previously reported (Wang et al. 2022). These effects of BHB are suggested to be involved in the attenuation of painful diabetic neuropathy through the modulation of astrocyte function (Wang et al. 2022).

4 Endogenous ketotherapeutics in astrocytes

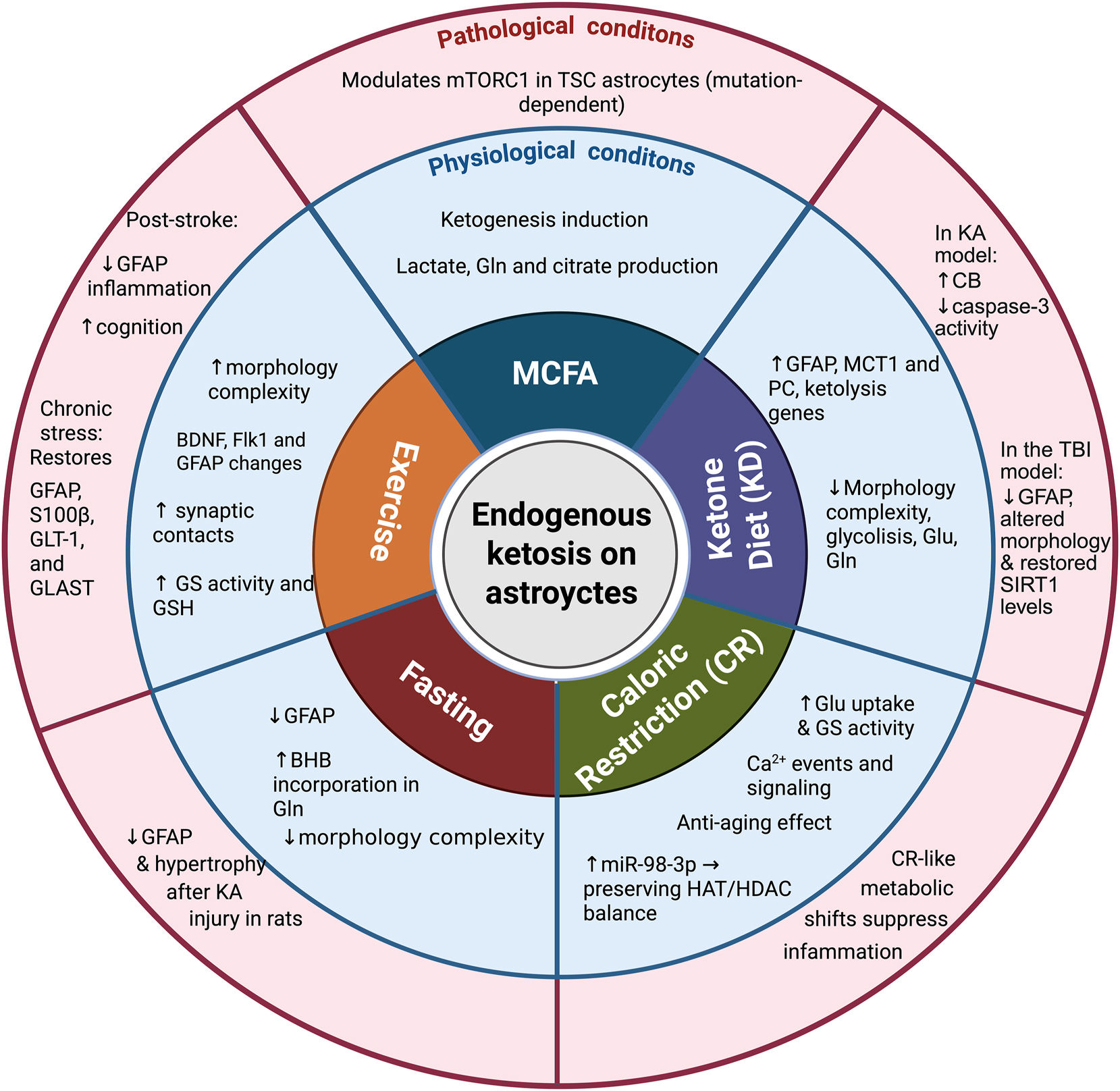

4.1 Effect of MCFA on astrocytes

4.1.1 Effect of MCFA on astrocytes under physiological conditions

A diet enriched in medium-chain triglycerides (MCTs) leads to the release of medium-chain fatty acids (MCFA) – such as caproic acid (hexanoate, C6), caprylic acid (octanoate, C8), capric acid (decanoate, C10), and lauric acid (dodecanoate, C12) – after enzymatic hydrolysis in the gastrointestinal tract (De Gaetano et al. 1994). These MCFAs are rapidly absorbed and transported via the portal vein to the liver (Qian et al. 1998), where they are preferentially oxidized to acetyl-CoA within mitochondria. The increased acetyl-CoA flux promotes hepatic ketogenesis, resulting in the elevated production of ketone bodies and enhanced mitochondrial energy output (Y. Cao et al. 2025; Jadhav and Annapure 2023; Kanta et al. 2025).

Beyond promoting hepatic ketogenesis, MCFAs have attracted attention for their potential to directly modulate energy metabolism in the CNS, since a fraction of the MCFAs can cross the blood–brain barrier and reach the brain, where they are rapidly metabolized (Ebert et al. 2003). Consequently, studies investigating the effects of MCFAs on astrocytes have mainly focused on their mitochondrial bioenergetic function and the oxidative preference among different MCFAs (Andersen et al. 2021, 2022; Nonaka et al. 2016; Thevenet et al. 2016).

In astrocytes derived from human iPSCs, exposure to the MCFAs, C8 and C10 (300 μM), decreases the NAD(P)H/NAD+ ratio, the mitochondrial membrane potential, and the mitochondria matrix ΔpH, but does not affect oxygen consumption or ATP synthesis (Thevenet et al. 2016). It was speculated that these effects might result from MCFAs acting as positive regulators of uncoupling proteins such as UPC-4, although this hypothesis has not been confirmed. In contrast, Andersen et al. (2021) reported that C8 increased OCR, while C10 increased the proton leak in mouse primary cultured astrocytes. These differences might result from variations in the experimental design. While Thevenet et al. (2016) used human iPSC-derived astrocytes, treated with 300 μM of C8 or C10 for 21 min before OCR measurement, Andersen et al. (2021) employed astrocyte cultures exposed to 200 μM of each fatty acid for 1 h prior to analysis. Further studies are required to clarify whether MCFAs consistently stimulate mitochondrial respiration in astrocytes in other preparations, including in vivo studies.

Concerning oxidative preference, studies have compared MCFA oxidation in astrocytes and neurons, and between individual MCFAs (C8 vs C10), addressing their metabolic fate and oxidation products. The study by Thevenet et al. (2016) showed that the oxidation products of C10 and C8 differ in human astrocytes. While C10 induced a rapid lactate production and had little effect on ketogenesis, C8 induced BHB production, although at a slower rate than lactate. From these results, it was suggested that MCFA oxidation in astrocytes might supply neighboring neurons with lactate and BHB. However, in vivo evidence of a lactate or BHB shuttle from astrocytes to neurons is still needed to confirm this suggestion.

In agreement with Thevenet et al. (2016), Nonaka et al. (2016) reported that exposing the KT-5 astrocyte cell line to MCFAs (C8, C12 and C18) for 4 h increased KB concentrations, with C8 being more rapidly oxidized and producing higher KB levels than C12 and C18, thereby supporting the ketogenic capacity of MCFAs.

A slower oxidation rate of C10 over C8 was supported by the results of Andersen et al. (2021) using 13C-labeled substrates in mouse astrocyte–neuron co-cultures. The authors suggested that the differential oxidation of C10 and C8 could underlie variations in their clinical efficacy; although, further validation is required, particularly regarding the specific glycolytic or ketogenic oxidation products (lactate and KB), which were not directly measured in this study (Andersen et al. 2021).

It has been hypothesized that the preferential oxidation of MCFA in astrocytes relative to neurons might be attributed to the distinct expression of a family of substrate-specific acyl-CoA dehydrogenases that oxidize fatty acids within a specific range of carbon chain lengths, leading to the formation of acetyl-CoA, the initial precursor of ketogenesis (Thevenet et al. 2016). This might also explain why C8 is a better substrate for ketogenesis than C10. However, this hypothesis remains to be confirmed, and further experiments are needed to elucidate the mechanisms governing the differential ketogenic potential of MCFA.

On the other hand, Andersen’s observations also suggested that C8 and C10 MCFAs are predominantly oxidized in astrocytes, leading to increased glutamine synthesis, while their oxidation in neurons enhances neuronal GABA formation, which might contribute to the anticonvulsant effects of MCT-based diets, although this mechanism has not yet been demonstrated in vivo.

Finally, competition experiments in cortical slices using radiolabeled C8, C10 and BHB, showed little antagonism for oxidation between MCFA and BHB. While C8 and C10 were oxidized to glutamine and citrate, indicating their metabolism in astrocytes, BHB was oxidized to glutamate, malate, aspartate, a-ketoglutarate, and GABA, suggesting their metabolism in neurons. These findings support a model where astrocytes actively metabolize MCFA, while BHB is primarily metabolized in neurons, with little competition with other substrates (Andersen et al. 2021, 2022).

Further investigations on MCFA-induced changes in mitochondrial oxidative metabolism in astrocytes is relevant to elucidate whether these effects contribute to the cognitive improvements reported in individuals with mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease receiving MCT-based interventions (Fortier et al. 2019; Henderson et al. 2009; Ohnuma et al. 2016; Rebello et al. 2015).

4.1.2 MCFA effect on astrocytes under pathological conditions

The neurodevelopmental disorder tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC), represents the pathological context in which the effect of MCFAs on astrocytes have been examined (Warren et al. 2020). Specifically, Warren et al. (2020) evaluated whether C10 modulates the mTORC1 (the mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1) signaling pathway in astrocytes derived from TSC patients, a condition resulting from mutations in TSC1 or TSC2.

Treatment with 300 μM C10 for 24 h in TSC1-mutant astrocytes reduced the phosphorylation of 4E-BP1 and S6K, two direct downstream targets of mTORC1 activity, suggesting mTORC1 inhibition. This effect was also evident in control astrocytes, but not in TSC2-mutant astrocytes, suggesting a possible heterogeneous response depending on the specific gene affected (Warren et al. 2020). Also, these findings suggest that C10 can reduce the mTORC1 signaling pathway independently of the disease. The mechanism underlying C10 inhibition of mTORC1 in human astrocytes remains unresolved. On the other hand, it remains unknown whether C10 administration increases KB levels, and C10 effects might also involve KB produced by its metabolism.

Together, these observations suggest that astrocytes may represent a cellular target of MCFAs, and that decanoic acid could modulate mTORC1 activity in the brain, possibly contributing to cognitive improvements in neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease and other neurological conditions associated with mTOR dysregulation.

4.2 Effect of the KD on astrocytes

The ketogenic diet (KD), composed by 70–80 % fat, 5–20 % carbohydrates, and 10–20 % protein, has shown positive effects against neurodegeneration and cognitive impairment in rodent models (Camberos-Luna and Massieu 2020; Rubio et al. 2025). Its effects have been attributed to multiple actions of KB, including their metabolic effect to generate ATP, anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties, epigenetic modifications, autophagy stimulation, and decreased proteotoxicity, among others (Cheng et al. 2009; Gómora-García et al. 2023; Montiel et al. 2023; Najmi et al. 2016; Zhu et al. 2022). Also, BHB can behave as a signaling molecule through its action on membrane receptors (Spigoni et al. 2022). Despite substantial evidence supporting the use of diet approaches to improve brain disease, the effects of the KD on astrocytes remain largely unknown.

4.2.1 Effect of the KD on astrocytes under physiological conditions

4.2.1.1 Astrocytic activation and morphological changes under the KD

The KD induces several adaptations in astrocytes that may contribute to its neuroprotective and antiepileptic effects. These adaptations depend largely on the astrocytic functional state, which is commonly inferred from canonical markers – glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), a structural component of the reactive cytoskeleton (Eng 1985; Lee et al. 2025; Oberheim et al. 2012), S100B, an astrocyte-derived trophic cytokine measured in tissue and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) (Emsley and Macklis 2006; Jurga et al. 2021; Lee et al. 2025), and glutamine synthetase (GS), a key enzyme of the glutamate–glutamine cycle (Anlauf and Derouiche 2013; Jurga et al. 2021; Norenberg 1979). Changes in these markers help to distinguish transient from sustained astrocytic activation (the latter often associated with inflammation) and to differentiate tissue alterations from changes in astrocytic secretion dynamics.

The effects of the ketogenic diet (KD) on the astrocytic markers GFAP and S100B appear to be transient and region-specific. In healthy Wistar rats fed a KD for 6 weeks, GFAP expression increased in the CA3 region of the hippocampus after 1 week but returned to baseline by 6 weeks (Silva et al. 2005). In contrast, S100B levels decreased only in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) after 8 weeks of KD (Vizuete et al. 2013), while remaining unchanged in hippocampal tissue at 1, 6 and 8 weeks (Silva et al. 2005; Vizuete et al. 2013), suggesting altered secretion dynamics rather than a change in cellular content. Therefore, the mechanism underlying the reduced CSF S100B levels (whether driven by diminished secretion or enhanced clearance) remains to be clarified. Likewise, hippocampal GS activity showed no significant alterations after 1 or 6 weeks of KD (Silva et al. 2005). These patterns possibly represent an early adaptive response to KD rather than pathological activation, as they are transient and not associated with inflammation.

Modifications in these markers under KD suggest coordinated adaptations in astrocytic structure, metabolism, and intracellular signaling. Notably, S100B is functionally linked to intracellular Ca2+ dynamics, as it directly binds Ca2+, acting as both a buffer and a signaling mediator (Donato 2001), suggesting that KD effect on astrocytes may extend to Ca2+-dependent processes.

In agreement, healthy male Wistar rats aged 70 days, and fed a KD for 4 months showed increased calbindin (CB; Ca2+-binding protein)-positive cells in the hippocampus and the M1 cortical area (Gzielo et al. 2019). This increase possibly contributes to the protective effect of KD by maintaining Ca2+ homeostasis, as enhanced Ca2+ buffering through CB may help to attenuate pro-apoptotic signaling. However, further research is needed to substantiate this interpretation. In vivo Ca2+ imaging of astrocytes combined with CB expression analysis could help to determine whether elevated CB levels reduce the amplitude or frequency of astrocytic Ca2+ waves, while electrophysiological recordings could clarify whether altered Ca2+ regulation mitigates excitotoxicity or seizure propagation. The quantification of apoptotic markers in parallel with the changes in CB levels in pathological models, such as kainate-induced epilepsy or ischemia–reperfusion injury, would be helpful to stablish a possible correlation between astrocytic remodeling, increased CB and reduced apoptosis by the KD.

Regarding morphology, Gzielo et al. (2019) reported that astrocytes from KD-fed healthy animals exhibit fewer intersections, smaller cell bodies, and reduced fractal dimensions compared to those from animals fed a standard diet. These changes do not appear to reflect chronic glial activation or inflammation, as markers such as GFAP, Iba1, and other astrocyte or microglial-related markers remain unchanged, likely because the animals were in a non-pathological state. Instead, these morphological simplifications possibly reflect a metabolic shift from glucose to KB metabolism (Gzielo et al. 2019).

These morphological effects contrast with the more complex astrocytic morphology reported after acute (10 mM BHB for 6 h) BHB administration in primary astrocyte cultures from newborn Wistar rats (Leite et al. 2004). These observations underscore the complexity of KD-induced astrocytic changes and suggest that both the duration and metabolic context of KB exposure influence astrocyte structure and function. Clarifying whether these KD-induced adaptations represent beneficial neuroprotective adjustments or persistent structural changes distinct from acute BHB effects will require further study.

Future investigations incorporating female and aged cohorts, energy-matched controls, and multiple time points, will increase our understanding of the KD effects on astrocyte function. Also, high-resolution techniques (such as 3D reconstruction, light-sheet, or two-photon microscopy) could better resolve fine perisynaptic processes and clarify whether KD induces subtle structural rearrangements or broader astrocytic remodeling. Elucidating KD-induced astrocytic morphological changes is particularly important to understand their interactions with neurons and the vasculature, which might also impact brain plasticity.

4.2.1.2 Metabolic adaptations in astrocytes under the KD

The administration of the KD to rats for three weeks induces adaptive changes in astrocyte metabolism. In the cerebral cortex of adult male GAERS rats (genetic absence epilepsy rat from Strasbourg), KD feeding for three weeks decreased acetate metabolism in neurons, while astrocytic acetate metabolism increased as suggested by the glutamate, glutamine, and GABA production from acetate oxidation (Melø et al. 2006).

Pyruvate carboxylase (PC) is an astrocytic enzyme that provides oxaloacetate to the TCA, which is more active in ketotic astrocytes (from KD fed rats during 3 weeks), possibly due to its allosteric activation by acetyl-CoA derived from KB (Melø et al. 2006). Also, in these animals increased pyruvate recycling through the TCA was observed in astrocytes. However, in primary cultured rat astrocytes, 5 mM AcAc exposure for 1 h inhibited PC (Hazen et al. 1997), possibly as a result of KB limiting pyruvate availability by inhibiting glucose oxidation. Alternatively, it was suggested that the KD (as well as carbonic anhydrase (CA) inhibitors) might act in part by altering astrocytic anaplerosis.

The contrasting effects of acetoacetate (AcAc) on astrocytic PC reported by Hazen et al. (1997) and Melø et al. (2006) likely result from differences in the model and the timescale used reflecting a possible acute inhibition versus chronic adaptation. The chronic in vivo study under sustained ketosis by Melø et al., suggests a shift toward enhanced anaplerosis (higher PC/PDH ratio), whereas the acute in vitro experiments reported by Hazen et al. (1997), showed that carbonic anhydrase inhibition by short-term AcAc exposure markedly reduced PC-dependent labeling, consistent with immediate substrate limitation.

Further studies are needed to clarify whether AcAc acts as a carbonic anhydrase–like inhibitor, limiting HCO3 − generation and thereby reducing PC flux. On the other hand, the apparent rise in PC activity reported by Melø should be viewed cautiously, as the higher PC/PDH ratio may reflect PDH inhibition rather than PC upregulation – since acetyl-CoA formed during ketosis both activates PC and inhibits PDH, shifting the balance upward without necessarily increasing total PC activity. Discrepant results might also be related to differences in astrocyte metabolism in in vitro and in vivo conditions, as Hazen et al. (1997) used pure astrocyte cortical cultures while Melø et al. examined the whole cortex, where mixed neuronal–astrocytic interactions, and astrocyte-specific acetate metabolism may predominate.

Another adaptation induced by the KD in astrocytes is related to the monocarboxylate transporter system. Astrocytes take up BHB through a carrier-mediated transport system as first described by Tildon et al. (1994). Their findings showed that BHB uptake is saturable (Km = 6.06 mM, V max = 32.7 nmol/30 s/mg protein), pH-dependent (with higher uptake at pH 6.2), and inhibited by metabolic blockers, suggesting H+ co-transport (symport) (Tildon et al. 1994). A direct link between KB transport and monocarboxylate transporters (MCT) was first suggested by Poole and Halestrap (1993), and later confirmed by Halestrap and Price (1999). Their study demonstrated that MCT1, MCT2, and MCT4 mediate KB transport in various tissues, including the brain, heart and muscle (Halestrap and Price 1999). MCT belong to the SLC16A solute carrier family, which comprises proton-coupled transporters responsible for facilitating the transport of monocarboxylates such as lactate, pyruvate and KB. Among the 14 known MCT isoforms, MCT1, MCT2 and MCT4 are expressed in brain (Pierre and Pellerin 2005), whereas astrocytes express MCT4 (SLC16A3) and MCT1 (SLC16A1), while MCT2 is enriched in neurons (Bröer et al. 1997; Debernardi et al. 2003; Hanu et al. 2000; Rafiki et al. 2003; Rosafio and Pellerin 2014).

Mice subjected to KD for three weeks showed an increase in brain expression and transport activity of MCT1 in cortical astrocytes. Moreover, the frequency of Ca2+ transients induced by bicuculline (a chemical inducer of epileptiform activity) was lower in cortical astrocytes from KD-fed mice than in those from control diet-fed mice. Results suggest that the increased expression and activity of MCT1 in astrocytes, and also possibly in neurons – since MCT1 has also been reported in neurons (Pierre et al. 2007) – might play a role in attenuating epileptiform activity (Forero-Quintero et al. 2017). However, further studies are needed to fully understand their contribution.

4.2.1.3 Transcription profile modifications in astrocytes under KD

The KD induces significant transcriptional and metabolic adaptations in astrocytes that collectively favor KB metabolism over glycolytic glucose utilization. Recent transcriptomic analyses in male mice have shown that KD (3 months) downregulates astrocytic insulin-signaling genes (Koppel et al. 2021), indicating a shift away from the canonical glucose-responsive pathways. Complementary proteomic and imaging studies further suggested the upregulation of β-oxidation and ketolytic pathways protein expression, together with enhanced astrocytic-mitochondrial SCOT immunofluorescence after the KD in the cortex (Düking et al. 2022). These findings highlight substantial changes in oxidative metabolism within astrocytes from KD-fed animals, exhibiting a shift from glycolysis toward oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS). This metabolic reorientation suggests that astrocytes prioritize KB oxidation while potentially sparing glucose for neuronal utilization, thereby promoting greater ketone use within the brain.

Despite overall agreement regarding metabolic remodeling, Koppel et al. (2021) and Düking et al. (2022) diverge in their observations on transcriptional regulation in astrocytes. Koppel et al. (2021) reported no statistically significant differences in gene expression within astrocytes, suggesting that KD-induced adaptations might be primarily functional and metabolic rather than the consequence of an extensive transcriptional reprogramming. In contrast, Düking et al. (2022) reported a coordinated upregulation of genes related to β-oxidation, ketolysis, TCA cycle, and OXPHOS, alongside the downregulation of glycolysis and glycogen metabolism-related genes. These apparent discrepancies likely reflect differences in experimental protocols, including species (rat vs mice), dietary fat content (90 vs 75 %), exposure duration and developmental stage at KD initiation (prenatal/perinatal vs juvenile). Such factors possibly influence astrocyte maturation and MCT1 content, circulating ketone levels, and the magnitude of transcriptional responses.

Beyond metabolic reprogramming, Koppel et al. (2021) focused on the regulation of intracellular signaling, reporting that feeding the KD downregulated astrocytic glutamate receptor pathways, consistent with a reduction in Ca2+ transients in KD-fed mice. Their analysis of pathology-associated modules revealed suppression of 14 pathology-related components, including those associated with cancer, addiction, metabolic disorders, infection, and cardiovascular disease. In contrast, Düking et al. (2022) did not specifically analyze pathology-related pathways but instead emphasized the broader metabolic flexibility of astrocytes compared to oligodendrocytes and neurons under KD conditions, underscoring their central role in cerebral energy adaptation.

Taken together, these complementary findings suggest that astrocytes respond to the KD with a shift toward ketone metabolism and mitochondrial oxidative activity while attenuating glycolytic flux. Further studies should delineate how these astrocytic adaptations might influence neuronal activity, network excitability, and disease progression, and further characterize the mechanisms underlying KD-induced transcriptional plasticity.

4.2.2 Effect of the KD on astrocytes under pathological conditions

The effect of KD on astrocytes under pathological conditions has been directly examined in a few studies, focused on excitotoxic and traumatic brain injury (TBI). In the excitotoxicity model, it has been reported that 4 weeks of KD feeding, beginning at postnatal day 21 (P21) in male ICR mice, increased astrocytic CB expression in the hippocampus following excitotoxic injury induced by an intraperitoneal injection of kainic acid (KA, 25 mg/kg), and assessed 48 h later at P50 (Noh et al. 2005). From these results it was suggested that CB upregulation might contribute to the neuroprotective effects of KD through calcium buffering, thereby limiting Ca2+-dependent activation of caspase-3 and reducing apoptotic vulnerability. Further investigation is needed to support the correlation between intracellular calcium dynamics, caspase-3 activity, and CB protein levels under the KD. Studies might also include both sexes, longer survival times and functional readouts.

In the pathological context of traumatic brain injury, it was reported that a KD administered immediately after mild controlled cortical impact (CCI) in adult male ICR mice mitigated cognitive deficits and astrocytic reactivity (Har-Even et al. 2021). Mice maintained on the KD for 30 days showed improved recognition memory in the novel object recognition (NOR) test. KD treatment also reduced astrocyte reactivity – evidenced by lower GFAP immunoreactivity in the DG – while cortical astrocyte activation remained unchanged. Additionally, the authors reported that KD feeding partially restored the levels of the NAD+-dependent histone/protein deacetylase, SIRT1, which were diminished by TBI, based on measurements from bulk cortical and hippocampal tissue. Although the study did not assess SIRT1 functional activity or its downstream targets, the authors speculated that the KD might attenuate reactive gliosis and support neuronal recovery, as SIRT1 activation has been shown to regulate key neuroprotective and metabolic pathways involving p53, nuclear factor-κB (NFκB), peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors α and γ (PPARα and PPARγ), PPARγ coactivator-1α (PGC-1α), liver X receptor, and FOXO (Martin et al. 2015). Future studies should directly examine SIRT1 activity and its downstream targets in animals treated with the KD.

Overall, the limited but consistent evidence suggests that KD effects on astrocytes under pathological conditions may contribute to neuroprotection, potentially through increased CB expression and reduced astrocytic reactivity. Nevertheless, these findings remain largely correlative, highlighting the need for mechanistic studies to elucidate how KD-induced metabolic adaptations in astrocytes translate into functional protection within neural circuits.

4.3 Effect of CR on astrocytes

4.3.1 Effect of CR on astrocytes under physiological conditions

4.3.1.1 Metabolic effects induced by CR in astrocytes

Caloric restriction (CR) refers to a sustained reduction of daily caloric intake by approximately 20–40 % below the total requirements, without altering meal frequency. Beyond its systemic metabolic benefits, CR exerts profound effects on brain metabolism and glial physiology. Early studies using adult male Wistar rats subjected to progressive caloric restriction (10 %, 20 %, and 30 % reduction in daily intake during the first, second, and subsequent ten weeks, respectively) for 12 weeks, showed increased hippocampal glutamate uptake and GS activity (Ribeiro et al. 2009; Santin et al. 2011). These findings were interpreted as indicative of enhanced astrocytic regulation of extracellular glutamate, potentially supporting neurotransmitter homeostasis under reduced energy availability. However, this interpretation remains indirect, as the conversion of glutamate into glutamine for neuronal reuse was not directly demonstrated. Santin et al. (2011) further expanded this approach by examining hippocampal redox status, and reported that CR, alone or combined with moderate exercise, elevated reduced glutathione levels (GSH), decreased protein carbonyls, and increased total antioxidant response. These results suggest that CR may not only alter astrocytic glutamate metabolism but also improve redox homeostasis, contributing to the neuroprotective profile of CR. However, the functional consequences of these biochemical changes were not evaluated and redox analyses lacked cellular resolution, thereby future work might combine astrocyte-targeted metabolic tracing with functional and redox imaging, to further understand whether CR induces coordinated metabolic and antioxidant remodeling in astrocytes to support synaptic resilience.

Increased glutamate uptake might result from changes in transporter abundance, altered trafficking dynamics, or enhanced astrocytic membrane coverage of synapses. Popov et al. (2020) examined these mechanisms in detail in adult male C57BL/6 mice aged 12–18 months subjected to short-term caloric restriction (40 % reduction in daily intake for 1 month) without altering feeding frequency. It was observed that CR enhanced glutamate clearance primarily through increased astrocytic enwrapment of synapses rather than transporter upregulation, as EAAT2/GLT-1 expression remained unchanged and GS levels were even reduced. This finding differs from the increased GS activity previously observed in younger rats after longer CR protocols (Ribeiro et al. 2009; Santin et al. 2011), likely reflecting differences in species, age, and CR duration that modulate astrocytic metabolic adaptation. Based on these findings, it was suggested that enhanced astrocytic coverage may restrict glutamate spillover and thereby reduce activation of extrasynaptic NMDA receptors, contributing to more efficient synaptic glutamate control under CR conditions (Popov et al. 2020). Whether these divergent GS responses correspond to changes in enzyme activity, post-translational regulation, or regional metabolic demands remains to be determined.

Studies on maternal CR during the pregestation and gestation periods show that it significantly impacts the astrocyte function of the offspring’s hypothalamus, particularly lipid metabolism and endocannabinoid signaling. In this model, female Wistar rats were subjected to a 20 % reduction in daily caloric intake beginning 8 weeks before mating and throughout pregnancy, while control dams were fed ad libitum. Maternal CR increases astrocytic markers (GFAP, vimentin) without affecting the microglial marker Iba1, indicating a specific astrocytic response. It also upregulates genes involved in fatty acid oxidation (Cpt1, Acox1), lipogenesis (Fasn), and lipid regulation (Srebf1, Srebf2), suggesting metabolic reprogramming of hypothalamic astrocytes. In addition, maternal CR alters astrocytic endocannabinoid signaling by increasing the expression of Dagla, the enzyme responsible for the synthesis of the endocannabinoid 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG), as well as Magl and Faah, which mediate its degradation, particularly in female offspring (Tovar et al. 2021). These changes might represent a compensatory mechanism for the reduced hypothalamic 2-AG levels previously observed (Ramírez-López et al. 2017, 2016). Notably, the expression of cannabinoid receptors type 1 (CB1) and 2 (CB2) remains unchanged, suggesting that the effects of CR are more related to endocannabinoid metabolism rather than receptor-mediated signaling (Tovar et al. 2021). Together, these findings suggest a role of hypothalamic astrocytes in long-term metabolic reprogramming in the hypothalamus induced by maternal CR, with potential implications for energy balance and feeding behavior in the offspring.

4.3.1.2 Epigenetic regulation induced by CR in astrocytes

Only a few studies have investigated the epigenetic changes regulated by CR specifically in astrocytes. Wood et al. (2015) examined the epigenetic changes in the cerebral cortex of male Fischer 344 rats maintained under CR for a lifelong duration (3–28 months). They identified miR-98-3p as the only miRNA consistently upregulated in CR and lipoic acid (LA) dietary groups. Because reduced miR-98 expression has been linked to neurodegeneration, the authors suggested a neuroprotective role for this miRNA. Although the cell type was not identified, in the cortical astrocytic cell line, CTXTNA2, miR-98-3p inhibition increased HDAC and reduced HAT activity, disturbing acetylation balance, whereas its overexpression had no effect. Based on these results, it was suggested that miR-98-3p supports HAT/HDAC homeostasis in astrocytes; however, the effect of CR-induced on inhibition of HDAC activity was not directly measured. Therefore, further studies are needed in order to understand the role of miR-98-3p upregulation in different brain cell types under CR.

On the other hand, Spencer et al. (2025) performed a transcriptomic study in human astrocytes exposed to the CR mimetic, 2-deoxyglucose (2-DG) at concentrations from 10–50 mM during 24 h, in combination with IL-1b (20 ng/ml). RNA-seq analysis revealed that 2-DG attenuated the increased expression of the pro-inflammatory cytokines, IL1-6, TNFα, CXCL10, CXCL9, IFIT2 and NOS2, induced by IL-1β. According to ATAC-seq analysis, IL-1β favored a chromatin open state and accessibility to astrocytic gene promoters, and the enrichment for DNA binding motifs of AP-1 and NfkB transcription factors involved in inflammation (Spencer et al. 2025). However, although 2-DG attenuated the inflammatory response, it had a marginal effect on chromatin accessibility in astrocytes, suggesting it does not significantly alter the epigenetic mechanisms involved in the regulation of the inflammatory response induced by IL-1β.

Overall, these observations suggest that glycolysis inhibition by 2-DG reduces inflammatory gene expression, however, the mechanisms involved remain to be elucidated, and the confirmation of these findings at the protein level is still needed. Understanding the impact of these effects on neuronal function and viability will shed light about the relevance of modulating the inflammatory response as a mechanism involved in the beneficial effects of CR.

4.3.1.3 Effect of CR on Ca2+ dynamics and aging in astrocytes

CR delays brain aging and supports synaptic plasticity, and accumulating evidence suggests that astrocytes are key mediators of these effects. Studies in male C57BL/6 mice maintained on 40 % calorie reduction for at least 6 months have shown that CR preserves astrocytic function across aging (Lalo et al. 2018, 2019). In cortical astrocytes (from cortical layers 2/3) from young (2–4 months) and aged animals (14–18 months), CR increased the frequency of Ca2+ transients, an effect more pronounced in older mice, which was associated with enhanced release of ATP and D-serine via CB1 and α1-adrenergic receptor activation. These findings suggest that CR mitigates the age-related decline in astrocyte–neuron communication (Lalo et al. 2018).

CR also appears to counteract the age-related decline in astrocytic Ca2+ signaling and purinergic responsiveness, helping to preserve receptor sensitivity and regulate ATP release. Aging reduces the efficacy of astrocytic Ca2+ signaling, partly due to decreased expression or sensitivity of P2X and P2Y receptors (Lalo et al. 2019). By maintaining Ca2+-dependent and purinergic pathways, CR may help sustain the excitatory–inhibitory balance within cortical circuits and support neuronal plasticity during aging. Consistent with this, CR enhances astrocyte–neuron communication by increasing the amplitude of glial-induced currents and restoring tonic GABAergic inhibition via PAR-1 receptor activation (Lalo et al. 2019).

There is also evidence supporting a link between CR and astrocytic Ca2-dependent modulation of synaptic plasticity. In adult mice subjected to 3 months of moderate CR (30 % reduction in intake), Lalo et al. (2020) reported that enhanced long-term potentiation (LTP) may depend on the Ca2-dependent release of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) from cortical astrocytes and the activation of neuronal MSK1 signaling. Complementary findings by Popov et al. (2020), using adult mice exposed to 1 month 30–40 % CR, showed that LTP enhancement could also result from increased hippocampal astrocytic glutamate uptake and reduced spillover, thereby limiting extrasynaptic NR2B-NMDAR activation. Although both studies were conducted in adult rather than aged animals, these findings possibly represent processes through which CR preserves or enhances astrocytic function and synaptic efficiency during aging, characterized by efficient Ca2+ signaling, balanced gliotransmission, and enhanced neurotrophic and metabolic support – thereby promoting synaptic plasticity and cognitive resilience in the aging brain.

A more detailed analysis of the effect of CR on hippocampal astrocyte Ca2+ dynamics in young mice exposed to 1 month of CR, revealed that it reduces the size, duration, and spatial spread of astrocytic Ca2+ events, likely due to a decrease in gap junction coupling, increased hemichannel activity, and changes in astrocyte morphology. Despite minimal changes in event frequency, CR enhances the amplitude and kinetics of Ca2+ transients, resulting in faster and more localized signals that may enable more precise modulation of synaptic activity and support improved neuroplasticity. Also, local Ca2+ microdomains are important for ATP synthesis, gene expression, and cell death induction in astrocytes (Denisov et al. 2021).

Additionally, CR-induced stimulation of astrocytic Ca2+ signaling has been reported to occur via inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate receptor type 2 (IP3R2), leading to ATP release and ATP neuronal signaling, which has been linked to CR antidepressant-like effects (Wang et al. 2021). This mechanism is supported by findings in IP3R2-KO mice, where exogenous ATP restored CR-induced behavioral benefits. These findings underscore the role of astrocytes in the neuroprotective and mood-stabilizing actions of CR, emphasizing astrocyte–neuron interactions as key elements in maintaining brain health and resilience to psychiatric disorders (Wang et al. 2021). Moreover, another possible mechanism underlying the antidepressant-like effects of CR could be enhanced astrocytic K+ clearance, as this process depends on K+ diffusion. This is supported by evidence showing that CR increases astrocytic K+ clearance, likely through an increased volume fraction (VF) of perisynaptic astrocytic leaflets (Popov et al. 2020).

On the other hand, the pharmacological mimetics of CR – including metformin and resveratol – were shown to produce similar enhancements in astrocytic Ca2+ signaling and synaptic modulation (Lalo and Pankratov 2021). Metformin improved mitochondrial membrane potential and adrenergic Ca2+ signaling, counteracting age-related astroglial decline, while resveratrol enhanced astrocytic Ca2+ signaling and synaptic plasticity through mechanisms requiring astroglial exocytosis and neuronal autophagy. These findings showed that CR mimetics promote astroglial remodeling and Ca2+ signaling, supporting synaptic plasticity and neuroprotection through autophagy-related pathways. These compounds promoted astrocyte function and neuron–astrocyte communication. Similarly, 2-DG, another CR mimetic, has been shown to attenuate astrocyte-mediated inflammatory response. Interleukin-1β administration increases IL-6 and other pro-inflammatory genes (IL-1β, TNFα, C3, LCN) in astrocytes, whereas 2-DG pretreatment suppresses their expression, suggesting that CR-like metabolic shifts can modulate astrocyte-driven inflammation (Vallee and Fields 2022). Collectively, both CR and CR mimetics facilitate astrocyte-driven modulation of synaptic transmission.

The effect of CR on senescence has also been addressed, specifically in senescent astrocytes from SAMP8 mice, a model of accelerated brain aging (García-Matas et al. 2015). Results showed that CR exerts cytoprotective effects by reversing age-related gene expression and restoring pathways involved in protein folding, ROS response, and ATP synthesis. While CR does not recover immune or mitotic functions, it reduces β-galactosidase levels and enhances the expression of mitochondrial, ribosomal, and antioxidant genes. It also improves mitochondrial function – elevating aconitase 2 levels, reducing the respiratory rate, and protecting against oxidative damage – though some dysfunctions, like reduced membrane potential, persist. Overall, CR partially restores a non-senescent profile (García-Matas et al. 2015).

Despite these advances, the molecular mechanisms linking CR to astrocytic Ca2+ regulation remain unclear. It is not yet known whether CR alters the expression or sensitivity of Ca2+-related receptors, or affects metabolites such as KB that could modulate astrocyte signaling. Elucidating these pathways will be essential for understanding how CR preserves glial function and synaptic homeostasis during aging.

4.3.1.4 Morphological changes induced by CR in astrocytes

CR may promote astroglial plasticity, modifying astrocyte structure and function to support synaptic activity and neuroprotection. The effects of CR on astrocyte morphology appear to be age-dependent. In aged mice (19–24 months) maintained on a long-term 60 % CR regimen that began at 14 weeks of age and was maintained until either 19 or 24 months, astrocyte size is reduced (Castiglioni et al. 1991). In contrast, in young mice (2 months old), short-term CR (1 month) increases the volume fraction (VF) of fine astrocytic processes, particularly perisynaptic leaflets, without affecting larger branches (Popov et al. 2020). This expansion might enhance astrocytic coverage of the synaptic microenvironment and improve metabolic and ionic buffering at active synapses.

Beyond these changes at the cellular level, CR also reorganizes astrocytic connectivity at the network level. It induces coordinated morphological and functional remodeling in astrocytes, enhancing network efficiency and adaptability. Popov et al. (2020) showed that CR (30 % reduction for 1 month) reduces the number of coupled astrocytes without altering gap-junction permeability, indicating preserved connexin function despite network reorganization. Specifically, C×43 expression and cluster density decrease, whereas C×30 levels remain stable with larger C×30 clusters in the soma and proximal branches, which possibly act as a reserve pool. These changes might be involved in the reorganization pattern of astrocytic interconnections and the morphological architecture of the glial network.

Further analyses are required to establish the causal relationship between astrocytic remodeling and the enhanced synaptic plasticity reported by Popov et al. (2020) and provide a mechanistic basis for these findings.

4.4 Effect of fasting on astrocytes

Intermittent fasting (IF) refers to eating patterns where the total daily caloric intake meets energy needs but is confined to specific time windows, alternating with extended periods of little or no food consumption (Johnstone 2015). Various IF protocols have been investigated and reported to increase KB production from fat, including alternate-day fasting (ADF) and time-restricted feeding (TRF), which trigger hormonal adaptations to maintain blood glucose levels and low insulin (Vasim et al. 2022). While short-term fasting increases KB blood levels from ∼0.3–1 mM, prolonged fasting can raise KB up to ∼7 mM (Camberos-Luna and Massieu 2020). The metabolic shifts induced by these interventions may shed light on our understanding of how fasting influences astrocyte function. The effects of fasting on astrocytes have been poorly explored; however, emerging studies highlight several important findings.

It has been reported that a 3 month exposure to an ADF markedly attenuates kainic acid–induced astrogliosis in rats, as evidenced by reduced GFAP levels relative to ad libitum–fed controls (Sharma and Kaur 2008). Complementary findings show that IF initiated at 24-months in rats, attenuates age-related astrocytic reactivity, as evidenced by reduced GFAP expression and diminished astrocytic hypertrophy as compared to age-matched ad libitum-fed controls. In addition, dietary restriction (DR) partially restored the age-related decline in neuronal plasticity markers, including neural cell adhesion molecule (NCAM) and its polysialylated form (PSA-NCAM). These observations suggest that DR may counteract age-associated reactive astrogliosis and help to preserve a neural environment supportive of synaptic plasticity and repair (Kaur et al. 2008).

Concerning metabolism, fasting markedly alters astrocyte energy utilization in the rat brain. It has been reported that after 36 h of fasting, BHB rapidly enters the brain and incorporates into key amino acids like glutamine, mainly synthesized by astrocytes (Jiang et al. 2011). Although neurons account for ∼70 % of BHB consumption, astrocytes contribute to about 30 %, indicating a meaningful shift in their energy utilization (Jiang et al. 2011).

On the other hand, it has been reported that overnight fasting (approximately 16 h) in mice induces morphological modifications in astrocytes within the mediobasal hypothalamus (MBH), characterized by shorter and less complex higher-order processes relative to the elongated morphology observed in the fed state (Y. Zhang et al. 2017). This remodeling was not observed in other brain regions, highlighting its importance in the hypothalamic regulation of energy balance. Although the molecular mechanism underlying fasting-induced retraction of astrocytic processes was not assessed, this structural remodeling possibly reflects a dynamic and reversible adaptation that enables the hypothalamus to respond to energy deprivation. It was suggested that such remodeling possibly involves intracellular calcium signaling or autophagy activation, both of which can influence cytoskeletal organization and cellular energy balance (Y. Zhang et al. 2017).

The molecular mechanism underlying these morphological remodeling remains unresolved. Future studies combining molecular, electrophysiological, and behavioral approaches might help to elucidate how fasting reshapes astrocyte–neuron interactions and whether similar adaptations occur under chronic or long-term fasting conditions relevant to human physiology.

4.5 Effect of exercise on astrocytes

Physical activity increases KB concentrations in blood, particularly during moderate to high-intensity exercise, regardless of whether it occurs as a single bout or as a part of long-term training regimens (Askew et al. 1975; Holcomb et al. 2021; Ohmori et al. 1990) (Table 1). However, when exercise is performed repeatedly, the magnitude of this increase appears to diminish compared to untrained individuals, who exhibit a higher rise in KB levels after exercise (Ohmori et al. 1990), suggesting that repeated exercise induces an adaptive response in KB metabolism. This adaptation possibly involves an enhanced ketolytic capacity driven by the upregulation of ketolytic enzymes, accompanied by a reduced hepatic ketogenesis (Evans et al. 2017).

Exercise protocols that increase KB levels in murine models.

| Reference | Speed description | Parameter | Ketone body blood levels (mM) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intensity | Duration | |||||

| Per session | Frequency | Total program | ||||

| Holcomb et al. (2021) | Graded treadmill test increasing speed: 10 m/min (15 min) + 12.6 m/min (15 min) + 2.4 m/min speed increase every 15 min, until exhaustion; constant 10 % grade. | Moderate to high | Variable (typically 45–90+ min) with individual performance capacity | Single acute test | Single acute test | >1 mM |

| Askew et al. (1975) | 29.5 m/min for 120 min/day, with 60s sprints at 56.5 m/min every 10 min, constant 8 % grade | Moderate to high | Long (120 min/day) | 5 days/week | Chronic training (12 week) | >1.2 mM |

| Ohmori et al. (1990) | 15 m/min, 90 min/session; tests done at weeks 14 and 28 after 2-day rest. No grade, steady pace. | Moderate | Moderate to long (90 min) | 3 days/week | Chronic (14 and 28 weeks) | >0.5 < 1.0 mM |