Nanocatalyst-enabled waste-to-energy systems: from material innovation to techno-economic and sustainability pathways

-

Bhanu Teja Nalla

Abstract

The accelerated proliferation of industrial, agricultural, and municipal waste, in conjunction with the escalating global demand for energy, underscores the imperative for sustainable waste-to-energy (WtE) methodologies. This review scrutinizes contemporary advancements in nano-engineered catalysts that augment the selectivity, kinetics, and energy recovery associated with the conversion of waste into hydrogen, syngas, and value-added fuels. Attention is directed towards a variety of catalyst categories, including single-atom catalysts, metal-organic framework (MOF)-derived structures, biomass-derived carbon nanomaterials, and plasmonic nanoparticles, as well as their synthesis utilizing waste precursors. Unlike previous reviews, this investigation combines nanoscale catalyst design with techno-economic evaluations, environmentally friendly synthesis methodologies, and artificial intelligence (AI)-driven optimization, thereby offering a comprehensive perspective that interconnects material innovation with system-level sustainability. Documented advancements reveal energy recovery efficiencies exceeding 80 %, hydrogen Faradaic efficiencies of over 95 %, and recyclability rates above 90 % under realistic conditions. Furthermore, life-cycle assessments, benchmark performance indicators, and comparative techno-economic analyses are provided to exemplify the scalability of nano-enhanced WtE. Constraints, including catalyst deactivation, nanoparticle toxicity, and hurdles in large-scale synthesis, are critically evaluated, alongside prospective avenues in hybrid solar-electrochemical systems and digital twin-assisted process management. This scholarly work presents a distinctive roadmap that positions nano-enabled WtE as a fundamental element of the circular hydrogen economy.

1 Introduction

The rapid accumulation of both solid and liquid waste has become one of the most pressing environmental and energy issues facing society in the 21st century. Driven by accelerated industrialization, urbanization, and intensive agricultural practices, the global generation of municipal solid waste (MSW) has already exceeded 2.1 billion tonnes annually. 1 It is projected to increase to 3.8 billion tonnes by 2050. This increasing burden of waste, predominantly composed of industrial discharges, agricultural by-products, and post-consumer plastics, is frequently inadequately managed, resulting in substantial GHG emissions, contamination of soil and water resources, and ongoing ecological degradation. 2 Concurrently, global energy consumption is projected to rise by over 25 % by 2040, especially in emerging economies that are experiencing rapid economic and infrastructural growth. Consequently, addressing these intertwined crises, waste proliferation, and escalating energy demand has thus become a fundamental prerequisite for sustainable development. 3 , 4

WtE technologies represent a promising approach to addressing these interconnected challenges by converting heterogeneous waste streams into valuable energy carriers, including hydrogen, syngas, and synthetic fuels. 5 Conventional thermochemical techniques, such as pyrolysis, gasification, and reforming, coupled with biochemical strategies like anaerobic digestion, have been thoroughly researched and demonstrated across various scales. 6 Nevertheless, their widespread implementation has been hindered by persistent obstacles, including substantial energy requirements, low fuel selectivity, catalyst deactivation, and inconsistent yields when applied to complex or contaminated feedstocks. In particular, traditional catalyst systems exhibit considerable susceptibility to sintering, coking, and poisoning, which diminish operational lifetimes and increase costs, thereby restricting industrial viability. 7

Nanotechnology presents transformative opportunities to overcome these challenges. Nano-engineered catalysts, characterized by their high surface-to-volume ratios, tunable defect structures, and tailored electronic properties, markedly enhance reaction kinetics, reduce activation energy barriers, and improve product selectivity. 8 Recent investigations have demonstrated hydrogen yields of 80–85 % and Faradaic efficiencies surpassing 95 % when employing nanocatalysts under realistic operational conditions. Beyond mere efficiency, their synthesis from waste-derived precursors such as agricultural residues, electronic waste, and biomass closely aligns with the principles of a circular economy by reducing reliance on virgin materials and promoting the valorization of resources. 9 Collectively, these advancements position nanocatalysts as both exceptionally effective and environmentally sustainable alternatives to conventional bulk catalyst systems. 10

While previous reviews have predominantly concentrated on either catalyst performance metrics or system-level assessments of WtE technologies in isolation, a notable absence persists of integrative perspectives that connect nanoscale catalyst design to broader sustainability and techno-economic frameworks. 11 This review aims to bridge the gap by integrating recent advancements in nanocatalyst engineering, green synthesis pathways, and process-level performance indicators with life cycle assessment (LCA), techno-economic analysis (TEA), and AI-assisted optimization methodologies. By contextualizing nanocatalyst-enabled WtE technologies within the evolving paradigm of the circular hydrogen economy, this article not only evaluates current accomplishments but also underscores critical limitations, including scalability, toxicity, and recyclability, while proposing forward-looking opportunities in hybrid solar-electrochemical platforms and AI-driven digital twin integration.

The corpus of literature examined in this review was meticulously gathered from the years 2019–2024, employing databases such as Scopus, Web of Science, ScienceDirect, and Google Scholar. The search terminologies encompassed “nano-engineered catalysts,” “waste-to-energy conversion,” “thermochemical nanocatalysts,” “green synthesis,” and “AI-assisted catalyst optimization.” Only peer-reviewed journal articles, conference proceedings, and seminal publications presenting quantitative findings on catalyst design, hydrogen yields, or environmental evaluations were considered for inclusion. Prior contributions that emerged before 2019 were incorporated judiciously to maintain contextual relevance. This methodical approach guarantees a thorough and equitable synthesis of both technical innovations and insights pertaining to sustainability.

2 Waste-to-energy conversion pathways

The transformation of heterogeneous waste into environmentally benign energy carriers is predicated upon a variety of complementary methodologies, each delineated by unique mechanisms, operational parameters, and resultant energy products. Conventional techniques such as combustion have been extensively utilized; however, they are beset by intrinsic limitations, notably significant GHG emissions and inadequate fuel selectivity. 12 In contrast, contemporary catalytic WtE methodologies employ thermochemical, electrochemical, and photocatalytic pathways that optimize fuel yield, reduce emissions, and facilitate integration into decentralized hybrid energy systems. 13 The ensuing subsections provide an in-depth examination of these pathways, elucidating their merits, limitations, and potential for incorporating nanocatalysts.

2.1 Thermochemical pathways

Thermochemical conversion techniques, including pyrolysis, gasification, and steam/dry reforming, constitute the foundational elements of WtE processes owing to their capacity to accommodate substantial, heterogeneous feedstocks.

Pyrolysis involves the thermal degradation of organic waste in oxygen-limited environments, yielding bio-oil, syngas, and char. The resultant product composition is heavily influenced by the nature of the feedstock and the thermal conditions applied to it. Nonetheless, traditional pyrolysis frequently encounters challenges such as tar formation and incomplete degradation of long-chain hydrocarbons. 14

Gasification is conducted at elevated temperatures (700–900 °C) with a controlled supply of oxygen or steam, converting waste into a hydrogen-rich syngas. While the process is adaptable, it is impeded by issues such as tar residues, catalyst deactivation, and substantial external energy demands. 15

Reforming reactions, encompassing steam reforming and dry reforming, are routinely applied to waste gases, plastics, and biomass-derived intermediates. These methods facilitate enhanced hydrogen yields; however, they necessitate resilient catalysts capable of withstanding sintering, coking, and halogen contamination, which are prevalent in numerous waste streams. 16

Nanocatalysts play a crucial role in mitigating these challenges by providing active sites for tar degradation, enhancing hydrocarbon reforming processes, and reducing activation energy thresholds. Their integration into thermochemical frameworks has consistently augmented syngas selectivity and hydrogen yields, while concurrently diminishing energy input requirements. 17

2.2 Electrochemical and photoelectrochemical pathways

Electrochemical methodologies offer a viable, low-temperature alternative for converting waste-derived liquids and gases into hydrogen and syngas. In electrochemical reforming, organic-rich wastewater or CO2-laden gas streams undergo catalytic reactions at the electrode interface, where nanostructured catalysts expedite hydrogen evolution reactions (HER). Documented Faradaic efficiencies frequently surpass 95 %, with current densities exceeding 200 mA/cm2 under ambient conditions. 18

Photoelectrochemical systems broaden this paradigm by integrating light absorption with electrochemical conversion, thereby facilitating solar-driven hydrogen production from wastewater and other intricate feedstocks. For instance, single-atom catalysts (SACs) affixed to nitrogen-doped carbon substrates demonstrate sustained stability while minimizing electricity consumption, underscoring the potential for scalable hydrogen generation from liquid wastes. 19

2.3 Photocatalytic pathways

Photocatalytic conversion harnesses solar radiation to directly decompose plastics, biomass, or organic waste under near-ambient conditions. Semiconductor-based photocatalysts, often enhanced with plasmonic nanoparticles such as gold or silver, utilize localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) to generate high-energy electrons. These electrons initiate the cleavage of bonds within organic polymers, thereby facilitating the evolution of hydrogen and the selective production of fuels. 20

In comparison to thermochemical methodologies, photocatalysis necessitates substantially lower external energy inputs, thereby rendering it appealing for integration with solar energy systems. Nonetheless, the efficiency of this process is constrained by limited light absorption spectra, rapid recombination of electron-hole pairs, and the exorbitant expense associated with noble metals. The utilization of carbon materials derived from waste and MOF-based supports is being increasingly investigated to enhance stability, broaden spectral absorption, and mitigate costs. 21

2.4 Hybrid and integrated pathways

Novel methodologies amalgamate the advantages of thermochemical, electrochemical, and photocatalytic processes into hybrid WtE platforms. For example, solar-assisted gasification amalgamates concentrated solar energy with nanocatalysts to diminish external heating requirements by as much as 20 %. Similarly, hybrid electrochemical-photocatalytic systems enable concurrent wastewater treatment and hydrogen generation under mild operational conditions. These integrated strategies exemplify how the coupling of multiple pathways can surmount the limitations inherent in individual processes while promoting continuous and decentralized energy production. 22

3 Nano-engineered catalysts for waste-to-energy applications

3.1 Metal and metal-oxide nanoparticles

Metal nanoparticles, comprising elements such as nickel (Ni), cobalt (Co), and iron (Fe), along with their corresponding oxides, including cerium dioxide (CeO2), play integral roles in thermochemical WtE processes, which involve pyrolysis, gasification, and reforming. At the nanoscale, these catalysts demonstrate enhanced active surface areas and optimized metal–support interactions, which facilitate increased hydrocarbon cracking rates and improved selectivity for syngas production. 23 Contemporary research highlights the significance of green synthesis methodologies that utilize precursors derived from industrial slags, red mud, or electronic waste, employing hydrothermal and ultrasound-assisted reduction techniques to mitigate environmental impacts. 24

3.2 Single-atom catalysts

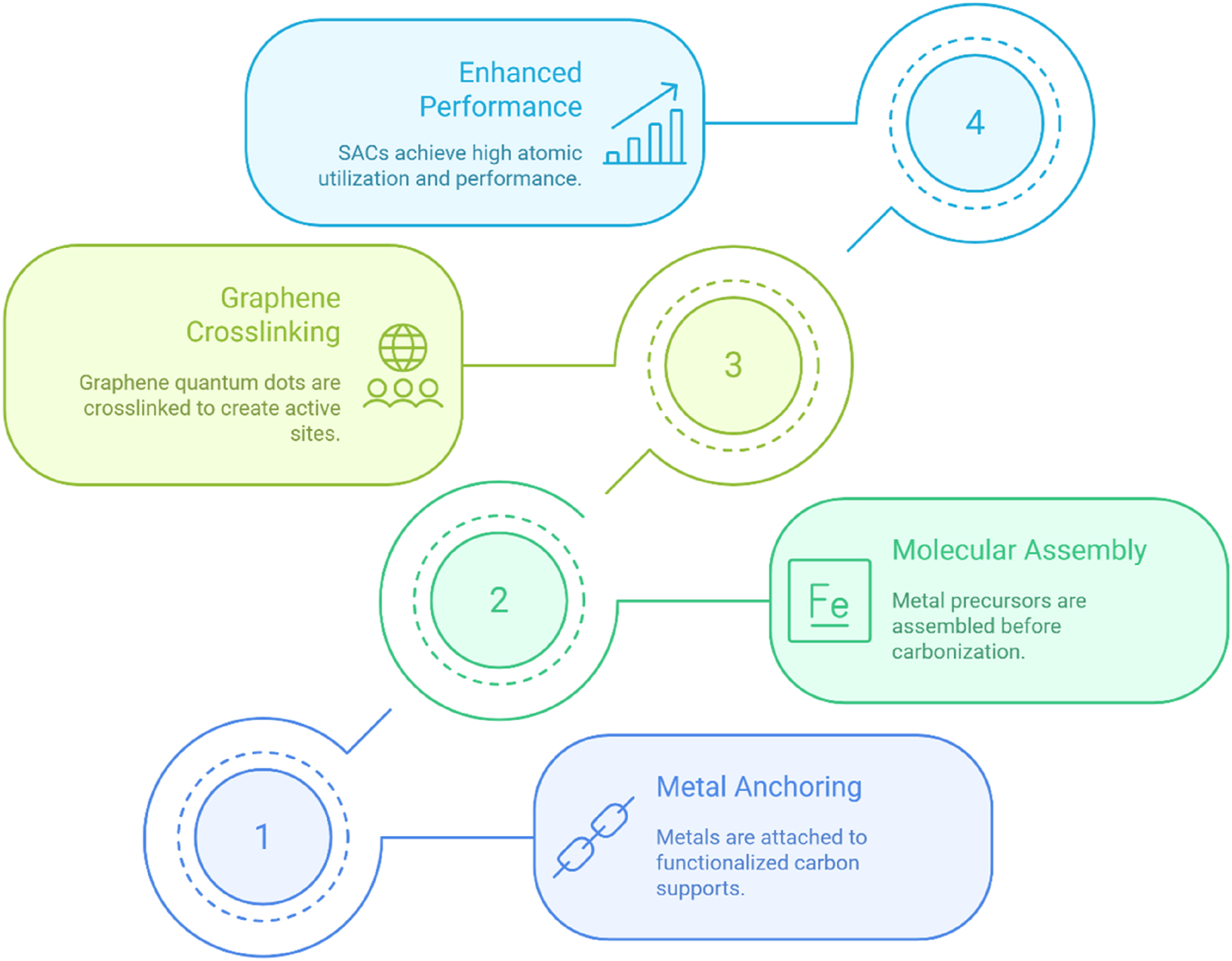

SACs achieve maximal atomic efficiency by immobilizing isolated metal atoms (such as iron (Fe), cobalt (Co), and platinum (Pt)) on nitrogen-doped carbon supports, frequently derived from agricultural waste materials. These catalysts exhibit exceptional activity in HER and carbon dioxide (CO2) reduction, attributable to their highly exposed and atomically dispersed active sites. Sustainable fabrication practices are realized through plasma-assisted deposition and electrochemical anchoring, which not only yield high-performance SACs but also contribute to the valorization of waste biomass.

Figure 1 outlines the methodologies for developing high-performance SACs synthesized from waste-derived supports. Techniques such as metal immobilization, molecular assembly, and graphene quantum dot interlinking facilitate the creation of atomically dispersed active sites. These innovations significantly enhance hydrogen selectivity, Faradaic efficiency (exceeding 95 %), and the long-term scalability required for applications involving the conversion of wastewater to hydrogen and the utilization of CO2.

Pathways to high-performance single-atom catalysts.

3.3 MOF-derived catalysts

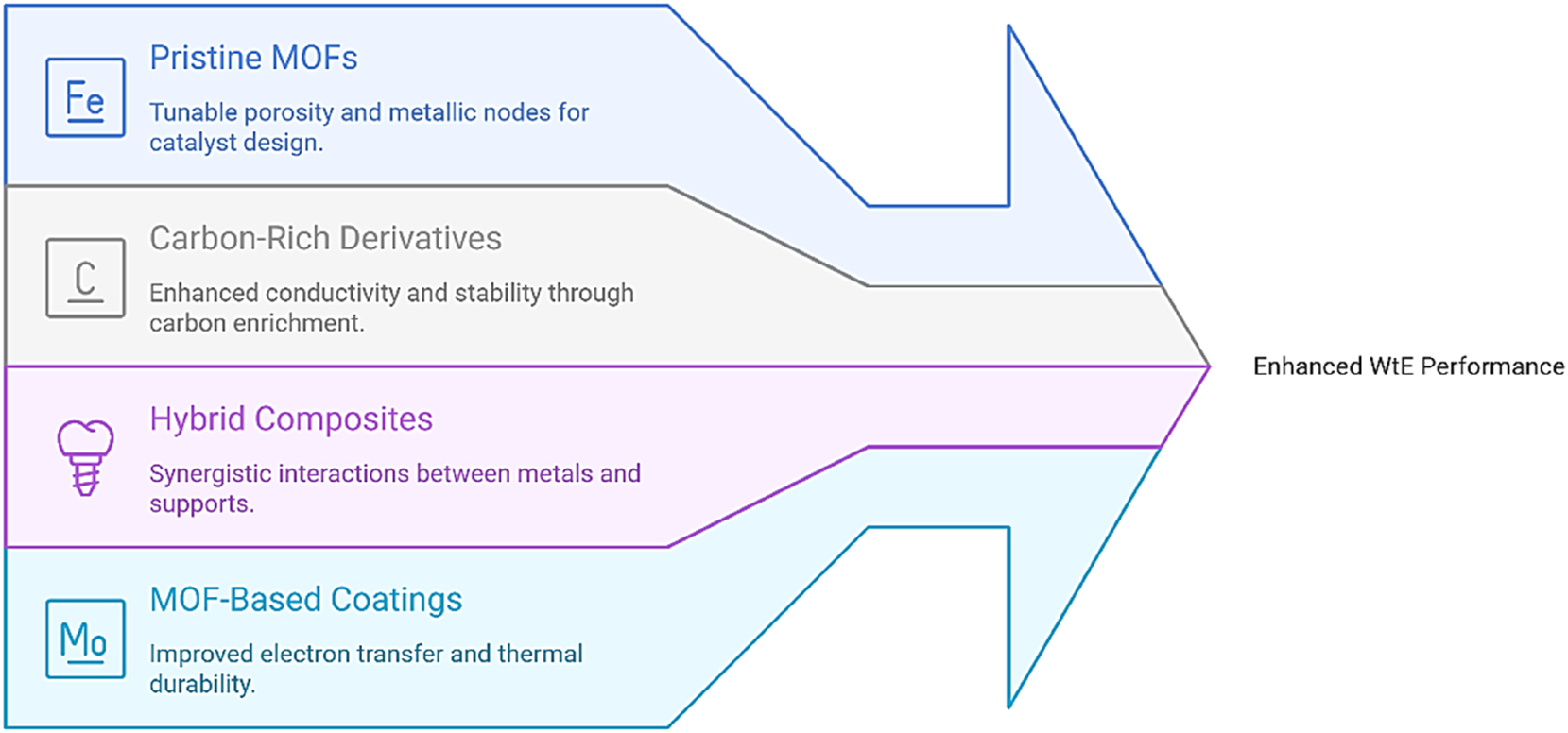

MOFs provide exceptionally porous crystalline structures that can be converted into nanostructured catalysts through meticulously controlled pyrolysis processes. Catalysts derived from MOFs exhibit substantial surface areas, uniform metal distributions, and improved conductivity, rendering them particularly effective for biomass reforming, methane dry reforming, and plastic depolymerization. The incorporation of bio-waste-derived carbons during the synthesis of MOFs further enhances sustainability while preserving catalytic efficacy. 25

Figure 2 illustrates MOF-based architectures that facilitate the enhancement of WtE catalysis. Unaltered MOFs, carbon-rich derivatives, hybrid composites, and coatings derived from MOFs offer adjustable porosity, enhanced stability, and improved electron transfer capabilities. Such architectural designs promote industrial scalability by enhancing syngas selectivity, reducing operational costs, and promoting the long-term durability of catalysts in reforming and carbon dioxide utilization pathways.

MOF-based designs for enhanced WtE performance.

3.4 Plasmonic nanoparticles

Plasmonic nanoparticles, predominantly composed of gold (Au) or silver (Ag), harness LSPR to activate visible light for low-temperature photocatalytic WtE applications. Contemporary green synthesis methodologies leverage plant extracts or fruit peels as reductants, thereby eliminating the need for toxic chemicals and diminishing environmental footprints. These catalysts facilitate the sunlight-driven degradation of plastics and organic waste materials into hydrogen and syngas under near-ambient conditions. 26

3.5 Biomass-derived carbon nanomaterials

Agricultural residues, lignocellulosic biomass, and food waste can be converted into nanoporous carbons, graphene-like nanosheets, or carbon nanotubes, which function either as economical catalyst supports or as independent electrocatalysts. Methodologies such as hydrothermal carbonization, chemical activation, and low-temperature pyrolysis yield nanocarbon materials with tunable heteroatom doping (including nitrogen (N), sulfur (S), and phosphorus (P)), thereby enhancing conductivity and catalytic performance for WtE applications. 27

3.6 Hybrid and waste-derived catalysts

Contemporary investigative trajectories underscore the significance of hybrid catalysts that amalgamate SACs, MOF-derived architectures, and biomass-derived carbonaceous materials, thereby harnessing synergistic interactions to enhance both efficacy and durability. An increasing focus is directed towards catalysts that are entirely derived from waste materials, wherein both the catalytic agents and the feedstock are sourced from waste streams, thereby facilitating a closed-loop valorization process that aligns with the principles of a circular economy. 28

Table 1 categorizes the various classes of nano-engineered catalysts pertinent to WtE applications. The summary encompasses catalyst types, precursors, synthesis methodologies, functional characteristics, applications within WtE contexts, and associated sustainability benefits. The data underscore the significance of waste-derived synthesis pathways and their congruence with the principles of the circular economy.

Classes of nano-engineered catalysts for waste-to-energy applications.

| Catalyst type | Source/precursor | Synthesis method | Active features | WtE application | Sustainability benefit | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metal/Metal oxides (Ni, Co, Fe, CeO2) | Industrial slags, red mud, e-waste | Hydrothermal, solvothermal | Oxygen vacancies, high surface area | Pyrolysis, gasification | Tar reduction, improved syngas yield | 29 |

| SACs (Fe–N–C, Pt–C) | Agricultural residues, biochar | Plasma deposition, anchoring | Atomically dispersed sites | Electrochemical reforming, HER | High atomic utilization, >95 % FE | 30 |

| MOF-derived catalysts | MOFs + waste carbons | Controlled pyrolysis | Porous carbon frameworks, metal dispersion | Reforming, CO2 utilization | Long-term stability, reduced cost | 31 |

| Plasmonic nanoparticles (Au, Ag) | Fruit peel extracts | Green synthesis, photodeposition | Hot-electron generation | Photocatalytic plastic reforming | Solar-driven, low-T processes | 32 |

| Biomass-derived carbons | Rice husk, lignocellulose, plastics | Hydrothermal, pyrolysis | N/S/P doping, porous networks | Electrocatalysis, syngas upgrading | Waste valorization, low cost | 33 |

4 Catalytic performance of nano-engineered systems

4.1 Comparative performance of bulk vs. nano-catalysts

The juxtaposition of bulk catalysts against nano-engineered counterparts unequivocally elucidates the merits inherent in nanoscale design for WtE applications. Traditional bulk catalysts, such as Ni/Al2O3 and iron-based oxides, generally yield modest hydrogen outputs, ranging from 60 to 68 %, and exhibit stability that frequently does not exceed 100 h, primarily due to rapid coking and sintering phenomena. 34 Conversely, nano-engineered systems consistently exhibit superior efficiencies, with Ni–Co nanoparticles supported on biochar derived from waste yielding energy efficiencies of 80–85 % and hydrogen concentrations of 65–70 vol%. Similarly, CeO2–NiO nanocomposites, synthesized from metallurgical byproducts, demonstrate markedly improved tar cracking capabilities and recyclability rates surpassing 90 %, thereby contributing to a reduction in replacement expenditures. The salient advantage arises from enhanced metal dispersion, the presence of defect-rich oxides, and intensified support interactions at the nanoscale, all of which collaborate to extend catalytic activity and reduce operational costs. 35

4.2 Mechanistic insights and selectivity

The enhanced efficacy of nanocatalysts is intricately linked to their ability to modulate active sites and optimize electronic environments. The engineering of defects, particularly through the introduction of oxygen vacancies in CeO2-based materials, facilitates the adsorption of oxygenated intermediates, thereby diminishing activation energy barriers pertinent to biomass reforming processes. 36 Metal–support interactions, exemplified by Ni–Fe nanoparticles incorporated within rice husk biochar, foster secondary cracking reactions that mitigate tar formation while enhancing hydrogen selectivity. SACs offer atomically dispersed Fe–N4 or Co–N4 coordination sites, resulting in nearly complete metal utilization and enabling Faradaic efficiencies ranging from 94 % to 97 % during the electrochemical reforming of wastewater streams. Similarly, plasmonic Au–Ag nanoparticles exploit LSPR to generate hot electrons that selectively cleave C–C and C–H bonds under visible light irradiation, facilitating photocatalytic hydrogen evolution rates of 120–150 μmol g−1 h−1. Collectively, these mechanisms elucidate how nanoscale control effectively translates into enhanced selectivity, reduced energy requirements, and diminished by-product formation when compared to bulk catalysts. 37

4.3 Conversion efficiencies and stability

Recent empirical investigations furnish corroborative evidence regarding the substantial efficiency enhancements attainable through the application of nano-engineered catalysts across various thermochemical, electrochemical, and photocatalytic pathways. In the context of catalytic pyrolysis of heterogeneous plastic mixtures, Ni–Co/biochar catalysts have yielded hydrogen-rich syngas with selectivity levels reaching 92–95 %, sustained activity for durations extending up to 200 h. 38 The gasification of biomedical plastics utilizing CeO2–NiO nanocomposites has resulted in hydrogen yields of 70–75 vol% while maintaining operational stability in excess of 150 h. Electrochemical reforming employing Fe–N–C SACs has established benchmarks with current densities exceeding 200 mA cm−2 at near-neutral pH values, demonstrating stable performance for over 200 h with minimal degradation. Similarly, MOF-derived Ni–Co@C catalysts have demonstrated the capability to sustain elevated hydrogen yields (80–85 vol%) over a continuous 250-h period of dry reforming, markedly outperforming bulk Ni catalysts that typically deactivate within 80–100 h. The photocatalytic degradation of polyethylene utilizing Au–Ag plasmonic nanoparticles has also evidenced stable hydrogen production over periods ranging from 100 to 120 h under solar illumination, thereby underscoring the robustness of these nanoscale systems. 39

4.4 Benchmark performance metrics

To facilitate standardized comparisons across various studies, benchmark values related to nano-enabled WtE systems can be systematically integrated. The hydrogen yields in thermochemical systems generally fluctuate between 70 and 85 vol%, in contrast to the range of 55–65 vol% observed for bulk catalyst systems. Faradaic efficiencies in electrochemical methodologies consistently achieve levels surpassing 94–97 %, while bulk systems infrequently exceed the threshold of 80 %. The efficiencies of energy recovery reach levels of 80–90 % when utilizing nanoscale catalysts, corroborated by life-cycle assessments that indicate energy return on investment (EROI) ratios ranging from 4.5:1 to 5.2:1, compared to EROI ratios of 2.5:1 to 3:1 for traditional systems. 40 The recyclability of catalysts emerges as another pivotal metric: waste-derived nanocatalysts attain recovery rates of 85–95 %, significantly exceeding the 50–60 % recovery rates typical for bulk materials. Furthermore, operational stability exhibits substantial enhancement, with nanoscale systems sustaining performance for durations of 200–250 h, compared to less than 100 h for their conventional counterparts. These consolidated performance metrics provide a pragmatic baseline for assessing novel catalyst designs and highlight the scalability associated with nano-engineered methodologies. 41

Table 2 provides a comparative evaluation of catalytic performance between bulk catalysts and nano-engineered catalysts within WtE systems. The reported metrics encompass hydrogen yields, Faradaic efficiencies, operational stability, and recyclability across thermochemical, electrochemical, and photocatalytic processes. Nano-engineered catalysts consistently demonstrate superior performance compared to bulk systems, exhibiting enhanced efficiency, prolonged stability (up to 250 h), and improved recyclability rates exceeding 90 %.

Comparative catalytic performance of bulk vs. nano-engineered catalysts.

| Catalyst type | Process | H2 yield (vol%) | Faradaic efficiency (%) | Stability (h) | Recyclability (%) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bulk Ni/Al2O3 | Gasification | 55–65 | 75–80 | <100 | 50–60 | 42 |

| Ni–Co/Biochar (nano) | Pyrolysis | 80–85 | – | 200 | 90–92 | 43 |

| CeO2–NiO (nano) | Gasification | 70–75 | – | 150 | >90 | 44 |

| Fe–N–C SAC | Electrochemical reforming | – | 94–97 | 200 | 85–90 | 45 |

| MOF-derived Ni–Co@C | Dry reforming | 80–85 | – | 250 | 90–95 | 46 |

| Au–Ag plasmonic NP | Photocatalysis | – | – | 100–120 | – | 47 |

In summary, nano-engineered catalysts facilitate groundbreaking enhancements in WtE processes. Their elevated density of active sites, customized defect structures, and electronic modifications contribute to superior hydrogen yields, improved selectivity, and prolonged operational lifespans. By incorporating waste-derived precursors into the synthesis of catalysts, both economic costs and ecological impacts are diminished, thereby aligning with principles of a circular economy. Benchmark evaluations consistently demonstrate that nanoscale catalysts outperform their bulk counterparts across key performance metrics, including stability and sustainability. These innovations position nanocatalysts as vital facilitators for the development of next-generation WtE systems that are adept at supporting decentralized, low-carbon energy networks.

5 Sustainability, green synthesis, and system integration

5.1 Green synthesis approaches for nanocatalysts

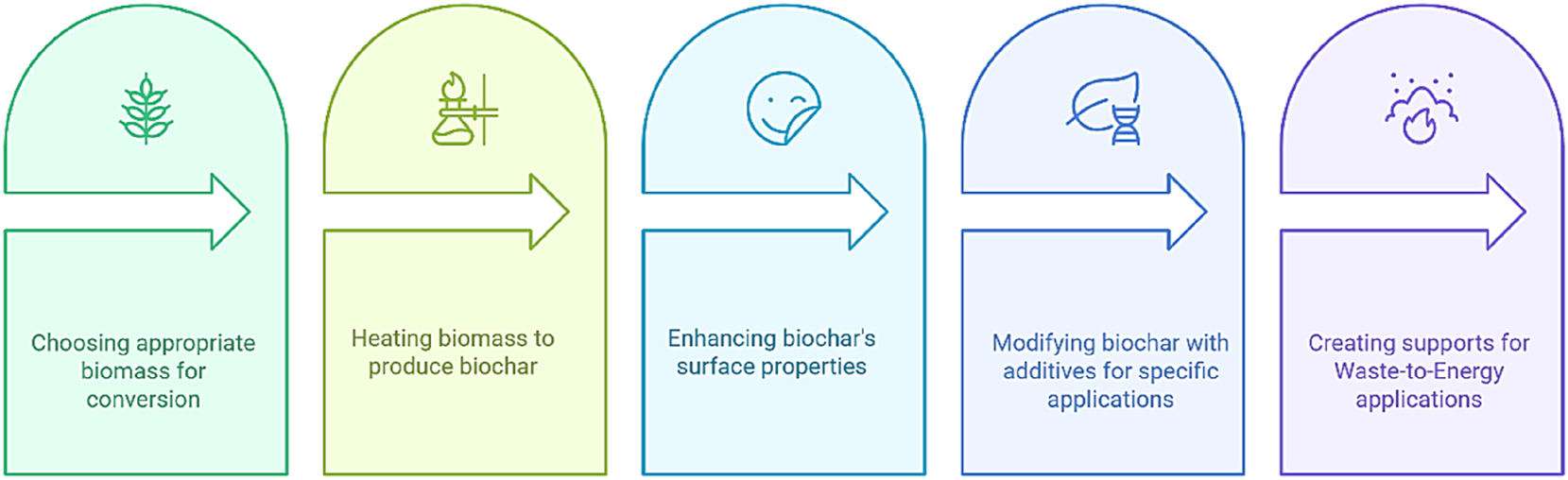

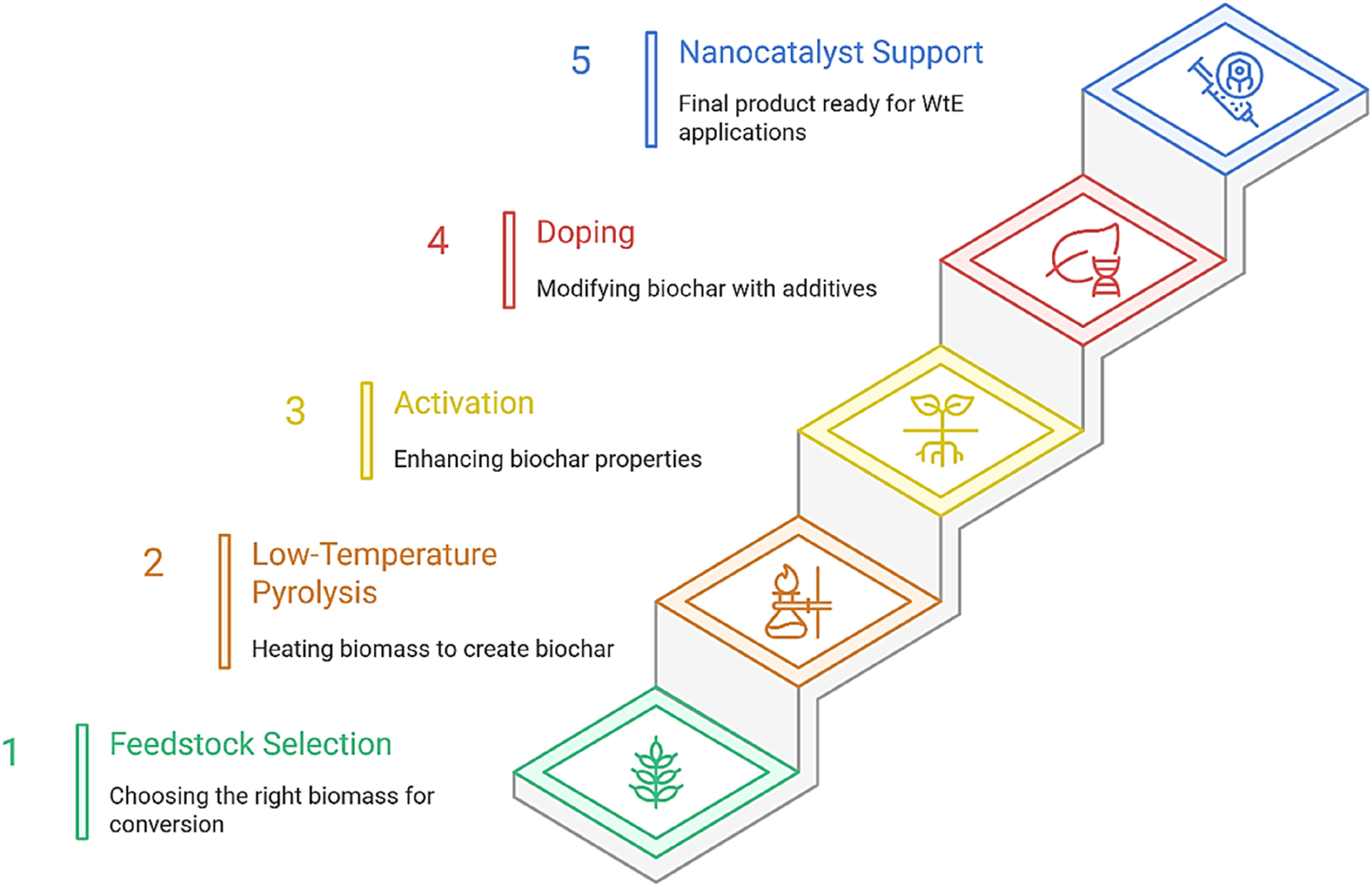

Ensuring sustainable production methodologies for nanocatalysts is crucial for achieving substantial advancements in WtE systems. Traditional catalyst synthesis processes are predominantly reliant on energy-demanding calcination and hazardous reductants, practices that may detract from the overall environmental advantages. In response to these concerns, the academic community has increasingly focused its attention on green synthesis methodologies that incorporate waste-derived precursors, environmentally benign reductants, and low-energy fabrication techniques. Agricultural by-products, industrial slags, leachates from electronic waste, and biochar derived from food waste have all been identified as feasible and cost-effective precursors, thereby diminishing the dependence on virgin materials while concurrently valorizing waste streams. 48 For instance, Ni–Fe nanoparticles extracted from electronic waste have been effectively utilized in pyrolysis processes, and nitrogen-doped carbons derived from lignocellulosic biomass have served as supports for SACs in hydrogen evolution reactions. Eco-friendly reductants, such as extracts from fruit peels, microbial metabolites, and plant saps, are increasingly being used to replace sodium borohydride and other hazardous chemicals. The adoption of water-based solvents has also replaced organic solvents to mitigate effluent toxicity. Likewise, low-energy synthesis techniques, such as hydrothermal synthesis, microwave-assisted pyrolysis, and mechanochemical milling, have resulted in a 25–40 % reduction in energy input compared to conventional calcination methods. 49

Figure 3 illustrates the production process for nanocatalyst supports derived from biochar. The sequential stages, including the selection of feedstock, execution of low-temperature pyrolysis, activation, doping, and subsequent catalyst loading, facilitate the transformation of biomass residues into highly efficient catalyst supports. This methodology effectively integrates resource valorization with the scalable fabrication of nanocatalysts for WtE applications.

Biochar-derived nanocatalyst production process.

5.2 Toxicity, safety, and recyclability of nanocatalysts

Notwithstanding their merits, nanocatalysts raise valid concerns regarding toxicity and long-term environmental safety. Unbound nanoparticles, particularly those composed of noble metals or metal oxides such as silver and ceria, have demonstrated a propensity to leach into terrestrial and aquatic systems, where they can bioaccumulate and pose significant risks to aquatic organisms and microbial communities. This concern has spurred increased scrutiny regarding immobilization strategies, which include the anchoring of nanoparticles onto biochar, MOFs, or magnetically recoverable supports, thereby enhancing catalytic stability and minimizing leaching phenomena. Magnetically recoverable Ni–Fe oxides are particularly appealing due to their capacity for facile separation utilizing external magnetic fields and their ability to be reused with minimal loss of efficiency. 49

Recyclability also holds paramount significance for both sustainability and economic viability. Empirical studies consistently indicate recovery rates exceeding 85 % for waste-derived nanocatalysts, with activity losses remaining under 5 % even after numerous reuse cycles. 50 By facilitating regeneration and reuse, these methodologies contribute to reducing both the environmental footprint and the overall costs associated with catalyst implementation. These strategies align directly with the principles of a circular economy, ensuring that nanocatalysts not only optimize energy recovery but also effectively close material loops and prevent the generation of secondary waste streams. 51

5.3 Life cycle assessment and energy return on investment

LCA offers indispensable insights into the comprehensive sustainability of nano-enabled WtE systems, thereby augmenting performance evaluation metrics. Recent investigations indicate that optimized processes assisted by nanocatalysts attain EROI ratios ranging from 4.5:1 to 5.2:1, in contrast to the 2.5:1 to 3:1 ratios observed for bulk systems. These enhancements can be primarily attributed to reduced activation energies, increased carbon conversion efficiencies, and the reuse of waste-derived catalytic supports. 52 In addition to energy assessments, LCA results reveal a 30 %–40 % decrease in CO2-equivalent emissions associated with catalytic pyrolysis when compared to thermal methods, alongside an impressive CO2 utilization efficiency exceeding 90 % in electrochemical reforming systems utilizing single-atom and MOF-derived catalysts. Furthermore, photocatalytic WtE pathways have been demonstrated to reduce water consumption by as much as 25 % relative to traditional thermal pretreatment processes, representing a significant sustainability advantage in areas confronted with water scarcity. 53

Figure 4 presents a comparative analysis of life cycle performance among traditional incineration, bulk catalyst-driven WtE systems, and nano-enabled catalytic frameworks. The metrics evaluated encompass carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions, EROI, catalyst recyclability, water conservation, and generation of solid residues. The data indicate that nano-enabled systems exhibit enhanced sustainability, which is in concordance with global decarbonization objectives.

Biomass-to-nanocatalyst support pathway.

Regional case studies underscore the applied significance of these findings. In India, the integration of catalysts derived from agricultural residues into decentralized gasification systems has enhanced energy accessibility in rural areas while concurrently mitigating open-field burning practices. Pilot facilities within the European Union utilizing MOF-based catalysts for reforming operations have achieved reductions of 20 %–25 % in operational expenditures through superior syngas selectivity. In China, life-cycle assessments of wastewater-to-hydrogen systems employing electrochemical nanocatalysts have revealed net-positive energy balances alongside a 40 % decrease in untreated wastewater discharge. These instances exemplify the adaptability of nanocatalyst-enabled WtE technologies across varied socio-economic landscapes while yielding quantifiable environmental benefits. 54

5.4 Techno-economic assessment and integration into hybrid systems

TEA is paramount for validating the scalability of WtE methodologies. Analyses suggest that nanocatalysts synthesized from waste-derived precursors can result in a 20 %–30 % reduction in catalyst costs, primarily due to reduced raw material requirements and extended catalyst lifespans. Enhanced conversion efficiencies in conjunction with lowered operational temperatures further facilitate a 10 %–15 % decrease in energy consumption within processes, thereby enhancing the financial viability of WtE facilities. Projections regarding fuel pricing indicate that syngas and bio-oil derived from nano-enabled pyrolysis and gasification can be offered at USD 1.2 to 1.6 per liter of diesel equivalent, making them competitive with fossil-derived fuels in regions with abundant waste resources. 55

Regional TEA case studies substantiate these conclusions. In Southeast Asia, catalytic pyrolysis facilities employing nickel-cobalt nanoparticles supported on rice husk biochar have successfully produced syngas at prices comparable to those of commercial fuels, benefiting from the availability of abundant local feedstocks. 56 In Europe, solar-assisted catalytic gasification utilizing plasmonic nanoparticles has demonstrated reductions of up to 30 % in CO2 emissions, along with 15 % decreases in operational costs. In North America, wastewater treatment facilities that integrate electrochemical flow cells with SACs have accomplished localized hydrogen production, thereby diminishing reliance on grid energy and achieving payback periods ranging from 5 to 7 years. 57

Table 3 outlines sustainability and techno-economic indicators associated with nano-enabled WtE pathways. The reported metrics include EROI, reductions in CO2 emissions, water savings, reductions in catalyst costs, and estimated fuel costs relative to fossil-derived alternatives. Regional case studies from Southeast Asia, North America, the European Union, and China illustrate the adaptability and scalability of these systems.

Sustainability and techno-economic indicators of nano-enabled WtE systems.

| WtE pathway | EROI ratio | CO2 reduction (%) | Water savings (%) | Catalyst cost reduction (%) | Fuel cost (USD/L diesel eq.) | Regional example | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thermochemical (nano-catalyzed pyrolysis) | 4.5–5.0:1 | 30–40 | – | 20–25 | 1.2–1.6 | Southeast Asia (rice husk) | 58 |

| Electrochemical (SAC/MOF systems) | 5.0–5.2:1 | >90 (CO2 utilization) | 10–15 | 20–30 | 1.4–1.6 | North America (wastewater H2) | 59 |

| Photocatalytic (plasmonic NP) | 4.0–4.5:1 | 25–30 | 20–25 | – | – | EU (solar-assisted demo) | 60 |

| Hybrid solar-electrochemical | 5.2–5.5:1 | >90 | 25 | 25–30 | 1.2–1.5 | China (pilot-scale WtH2) | 61 |

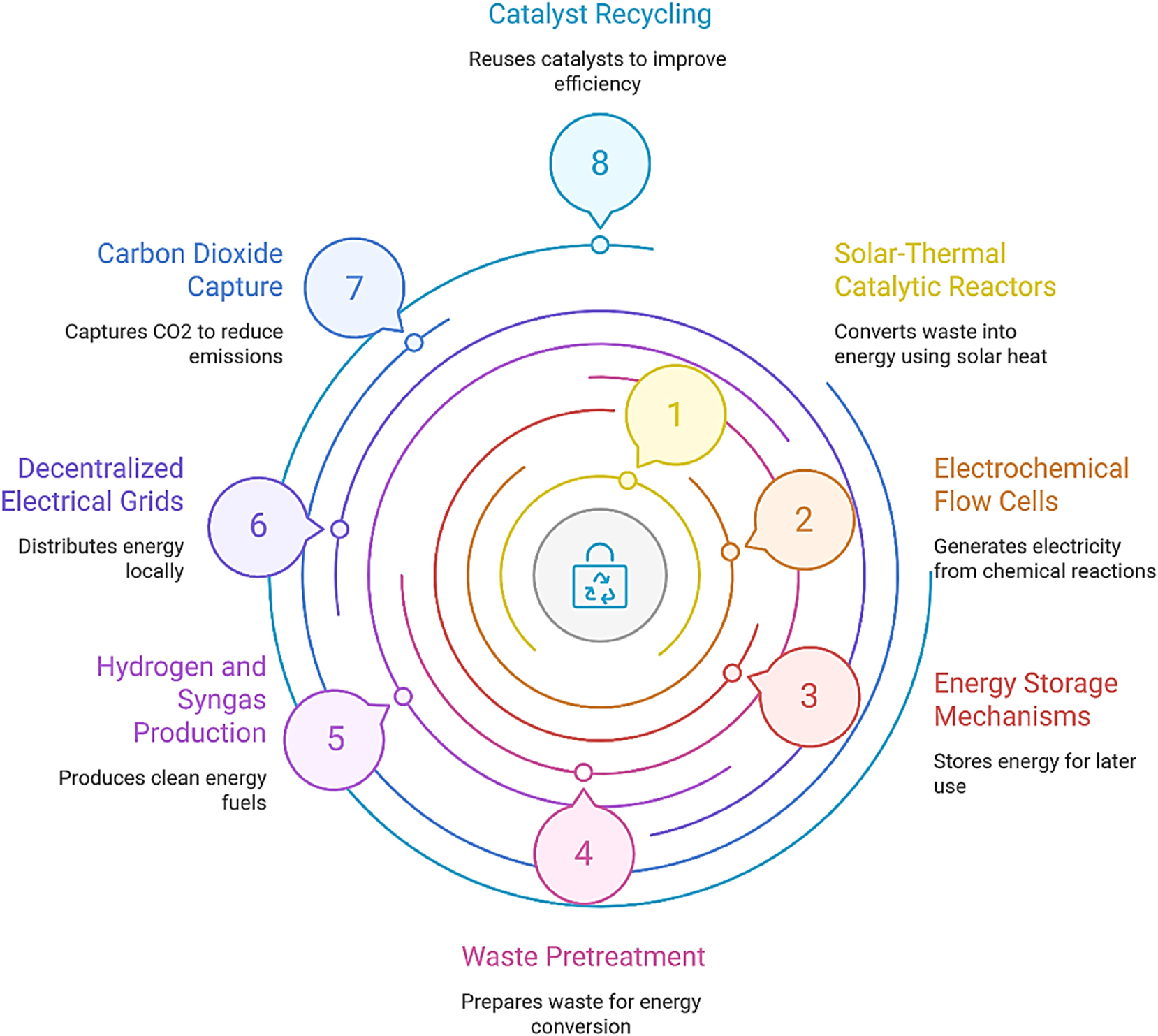

Figure 5 delineates a conceptual framework for an integrated hybrid WtE system. This framework combines solar-thermal catalytic reactors, electrochemical flow cells, energy storage mechanisms, and carbon capture modules, along with catalyst recycling initiatives, to facilitate the production of hydrogen and syngas. The model exemplifies the potential for integration of nano-enabled WtE systems with decentralized electrical grids and principles of the circular economy.

Integrated hybrid waste-to-energy system.

The sustainability of nanocatalyst-enabled WtE systems is influenced not solely by their performance efficiency but also by the environmental and economic paradigms that regulate their implementation. Innovations in green synthesis have demonstrated that precursors derived from waste and environmentally benign reductants can replace expensive and hazardous substances, thereby reducing environmental impact. LCA and TEA evaluations have consistently demonstrated that nanocatalyst-based systems outperform bulk or non-catalytic techniques in terms of energy balance, emissions, and cost efficiency. 62 Extended discussions on toxicity and recyclability underscore the necessity for the design of catalysts that pose minimal ecological threats and offer maximal potential for reuse. Regional case studies further demonstrate that these technologies can be tailored to various contexts, ranging from rural India to industrial Europe, while yielding quantifiable benefits in terms of sustainability. Collectively, these insights indicate that nanocatalyst-enabled WtE technologies, when synergized with renewable integration and circular economy initiatives, offer a formidable trajectory towards low-carbon, decentralized, and scalable energy systems. 63

6 Challenges, policy, and future outlook

6.1 Catalyst deactivation and stability

Despite significant advancements, the longevity of nanocatalysts within practical WtE systems remains a substantial challenge. The presence of heterogeneous feedstocks enriched with sulfur, chlorine, heavy metals, and halogenated polymers exacerbates catalyst deactivation mechanisms, including coking, poisoning, and nanoparticle sintering. 64 While oxidative cleaning and solvent regeneration can provide partial rejuvenation of performance, successive cycles frequently lead to structural deterioration. To address these challenges, innovative approaches are being prioritized, including bimetallic single-atom catalysts, defect-engineered supports, and self-regenerating nanocatalysts endowed with oxygen storage capabilities, all of which demonstrate enhanced resistance to deactivation and extended operational longevity under diverse feedstock conditions. 65

6.2 Scalability and standardization

The transition from nanocatalyst synthesis on a laboratory scale to an industrial scale, in terms of tonnage, presents a considerable obstacle. High-precision methodologies such as atomic layer deposition or plasma-assisted doping incur significant costs and encounter scalability challenges. 66 Emerging alternatives such as continuous flow synthesis, spray pyrolysis, and modular reactor systems offer promising avenues for achieving more uniform production of nanocatalysts. Equally significant is the absence of standardized benchmarking protocols, which hinders comparative analyses across different studies. Although metrics such as hydrogen yield, Faradaic efficiency, and EROI are frequently reported, they are often evaluated under disparate conditions that inhibit comparability. Consequently, establishing global standards for assessing nanocatalyst activity, stability, recyclability, and life-cycle impact is imperative for facilitating both scientific inquiry and industrial implementation. 67

6.3 Digitalization and AI/ML integration

The escalating complexity of WtE systems necessitates the incorporation of AI and Machine Learning (ML) methodologies for the optimization of catalyst discovery, feedstock classification, and real-time process regulation. Recent developments include artificial neural networks (ANNs) capable of predicting syngas composition and refining gasification conditions, genetic algorithms (GAs) for selecting optimal catalyst formulations, and reinforcement learning (RL) models dedicated to adaptive process management in hybrid systems. Furthermore, the use of digital twin simulations is gaining prominence, enabling the creation of virtual replicas of large-scale reactors that facilitate fault detection, predict deactivation, and extend the operational lifetimes of catalysts. 68

By integrating these advanced tools with sensor-based monitoring systems, WtE facilities can evolve into self-learning, adaptive, and exceptionally efficient operational frameworks. Nevertheless, the widespread implementation of these technologies is contingent upon the availability of open-access datasets, the establishment of standardized performance metrics, and the development of resilient cyber-physical infrastructures. 69

6.4 Policy and infrastructure alignment

The efficacy of nanocatalyst-enhanced WtE technologies is contingent not solely upon advancements in scientific research but also upon the establishment of supportive policy frameworks and adequate infrastructure. In numerous developing regions, the lack of systematic waste segregation, collection, and preprocessing significantly hampers catalytic efficiency, thereby accentuating the necessity for comprehensive governance and investment in decentralized WtE facilities. Consequently, policies should prioritize segregated feedstock streams, implement carbon credit mechanisms, and provide capital subsidies to effectively bridge the gap between laboratory innovations and their industrial applications. 70

Regional case studies exemplify the prevailing momentum in this domain. Within the European Union, the Waste Framework Directive and the Emission Trading Scheme actively promote the integration of catalytic WtE technologies with carbon capture and renewable energy sources. In India, initiatives such as the Swachh Bharat Abhiyan and the National Bio-Energy Mission promote decentralized biomass gasifiers and biochar-based catalysts to enhance rural energy accessibility. Moreover, China has established targeted subsidies for pilot projects focused on waste-to-hydrogen conversion utilizing electrochemical nanocatalysts. In contrast, in North America, renewable fuel standards provide credits for hydrogen and syngas produced from municipal waste. 71

Quantitative incentives further bolster this developmental trajectory: the EU Emission Trading Scheme assigns a value of €80–100 per ton of CO2 in carbon credits, India offers subsidies that cover 30–35 % of capital expenditures, and U.S. Low Carbon Fuel Standards provide financial benefits amounting to $180–200 per ton of CO2e mitigated. These mechanisms underscore the potential of bespoke policy instruments to facilitate the rapid scaling of nano-enabled WtE systems. 72

6.5 Future perspectives

The prospective evolution of nanocatalyst-enabled WtE technologies hinges upon multidisciplinary convergence, wherein materials science, reactor engineering, artificial intelligence, and policy frameworks collaboratively function. Anticipated next-generation WtE platforms are projected to incorporate self-regenerating catalysts derived from waste materials, hybrid solar-electrochemical systems, and AI-driven digital twins for predictive maintenance and adaptive process management. The establishment of standardized benchmarks will facilitate equitable comparisons, while robust policy frameworks will incentivize large-scale industrial deployment. 73

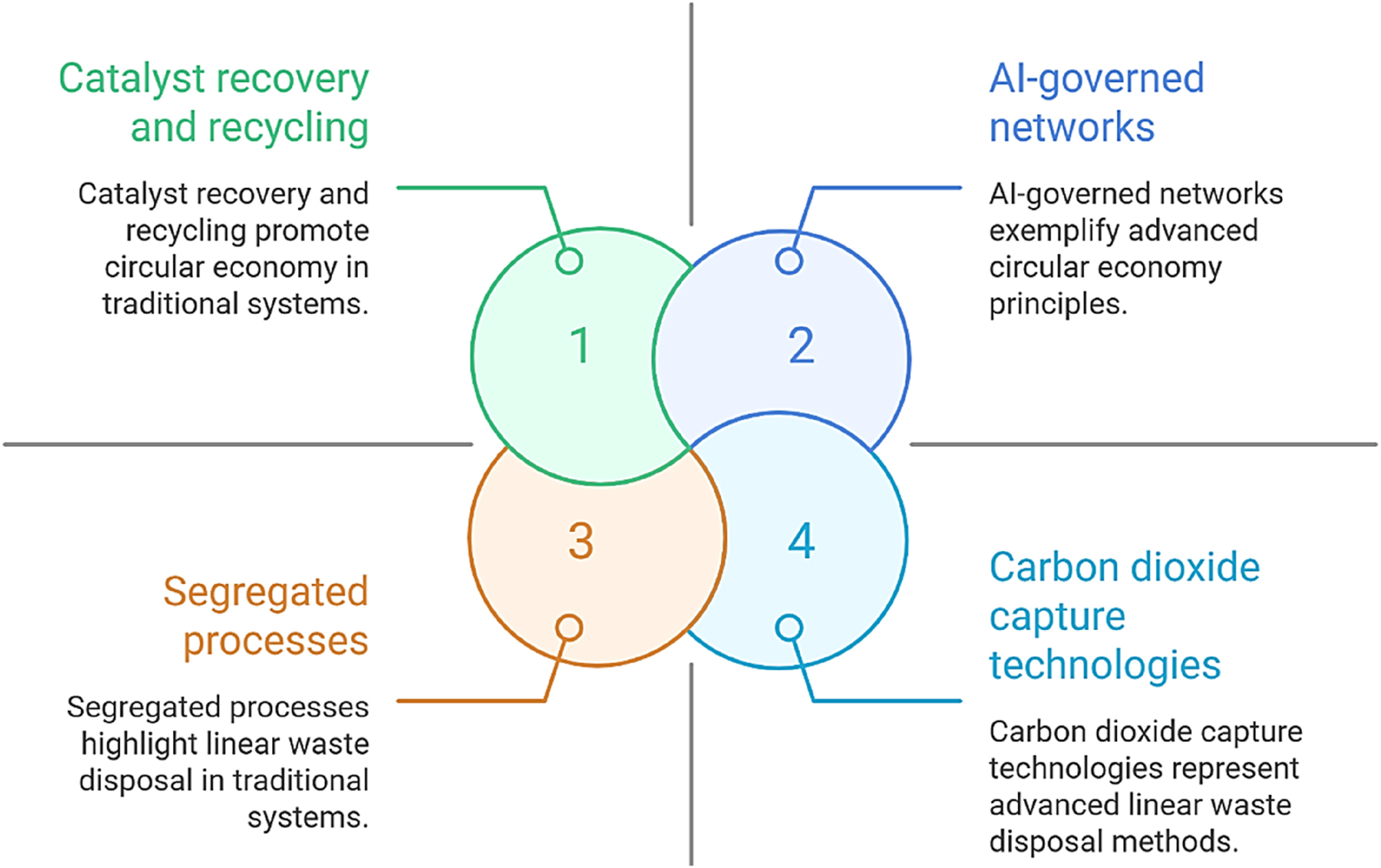

Figure 6 illustrates the evolution of WtE systems, transitioning from the current paradigm characterized by segregated, high-energy processes with frequent catalyst deactivation to future networks governed by AI that leverage solar and electrochemical methodologies, utilizing waste-derived nanocatalysts and CO2 capture technologies. This trajectory exemplifies the movement towards decentralized, intelligent, and low-carbon WtE ecosystems.

Evolution of waste-to-energy systems.

In conclusion, while nanocatalysts have already exhibited considerable advantages in terms of efficiency and sustainability within WtE conversion processes, the scaling of these technologies necessitates addressing issues of deactivation, ensuring the establishment of standardized performance metrics, and facilitating the deployment of AI-driven digitalization. Equally vital are the reforms in policy and infrastructure that cultivate conducive environments for decentralized implementation. The integration of nanotechnology, renewable energy sources, digital optimization, and supportive policy measures presents a transformative trajectory toward future-ready WtE systems that not only provide clean energy but also embed principles of circularity, resilience, and decarbonization at their core.

7 Conclusions

Nano-engineered catalysts have significantly altered the landscape of WtE technologies by facilitating the highly efficient, selective, and sustainable conversion of diverse waste streams into hydrogen, syngas, and various alternative fuels. Through advancements in surface engineering, defect modulation, and precision at the single-atom level, nanocatalysts achieve superior hydrogen yields, Faradaic efficiencies exceeding 95 %, and prolonged operational stability over extended cycles compared to traditional systems. Equally noteworthy are the strides made in green synthesis, wherein waste-derived precursors, environmentally benign reductants, and low-energy manufacturing techniques mitigate both costs and ecological impact, thereby aligning WtE systems with principles of the circular economy. Life cycle and techno-economic assessments consistently demonstrate enhanced energy returns, reduced emissions, and competitive pricing of fuels. Regional case studies conducted in India, the EU, China, and North America validate the real-world applicability of this approach.

Nevertheless, challenges persist in addressing issues related to catalyst deactivation, scalability, and the absence of standardized performance metrics. Future advancements will hinge on the integration of AI-driven catalyst discovery, digital twin-enabled process optimization, and adaptive ML frameworks, which collectively promise to deliver predictive control and expedite innovation. Concurrently, supportive policy frameworks such as carbon credit systems, waste segregation initiatives, and renewable fuel regulations are essential to ensure the widespread adoption of these technologies. Looking ahead, the amalgamation of nanotechnology, sustainability, artificial intelligence, and policy alignment is poised to revolutionize WtE systems from isolated processes into intelligent, decentralized, and low-carbon platforms, thereby positioning them as a foundational element of the circular hydrogen economy and global decarbonization strategies.

-

Research ethics: Not applicable.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Author contributions: The authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: The authors acknowledge the use of AI-assisted tools, notably Grammarly, to improve linguistic accuracy, correct grammatical errors, and increase the overall coherence of this article. The content, analytical discussion, and conclusions presented in this work are distinctly the original contributions of the author, with AI tools utilized solely to enhance the presentation and clarity of the text. The use of AI complies with the journal’s requirements for transparency and ethical norms in authorship processes.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: None declared.

-

Data availability: Not applicable.

References

1. Su, L.; Wu, S.; Fu, G.; Zhu, W.; Zhang, X.; Liang, B. Creep Characterisation and Microstructural Analysis of Municipal Solid Waste Incineration Fly Ash Geopolymer Backfill. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14 (1), 2982; https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-81426-7.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

2. Peng, X.; Jiang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Osman, A. I.; Farghali, M.; Rooney, D.; Yap, P.-S. Recycling Municipal, Agricultural and Industrial Waste into Energy, Fertilizers, Food and Construction Materials, and Economic Feasibility: a Review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2023, 21 (2), 1–37. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10311-022-01551-5.Search in Google Scholar

3. Chiang, P. F.; Zhang, T.; Joie Claire, M.; Jean Maurice, N.; Ahmed, J.; Giwa, A. S. Assessment of Solid Waste Management and Decarbonization Strategies. Processes 2024, 12 (7), 1473. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr12071473.Search in Google Scholar

4. Verma, S. K.; Singh, D.; Misra, S. Innovative Approaches to Sustainable Waste Management and Energy Generation in Developing Nations. Pract., Prog. Proficiency in Sustain. 2024, 267–300. https://doi.org/10.4018/979-8-3693-4054-7.ch010.Search in Google Scholar

5. Frantzi, D.; Zabaniotou, A. Waste-Based Intermediate Bioenergy Carriers: Syngas Production via Coupling Slow Pyrolysis with Gasification Under a Circular Economy Model. Energies 2021, 14 (21), 7366. https://doi.org/10.3390/EN14217366.Search in Google Scholar

6. Christopher Selvam, D.; Devarajan, Y.; Behera, P. R.; Manjunath, H. R.; Ajmeri, K.; Das, N.; Ramachandra, C. G. Recent Advances in Photocatalytic Plastic Waste Conversion: A Review on Renewable Energy Pathways. Rev. Inorg. Chem. 2025. https://doi.org/10.1515/revic-2025-0061.Search in Google Scholar

7. Achi, C. G.; Snyman, J.; Ndambuki, J. M.; Kupolati, W. K. Advanced Waste-to-Energy Technologies: a Review on Pathway to Sustainable Energy Recovery in a Circular Economy. Nat. Environ. Pollut. Technol. 2024. https://doi.org/10.46488/nept.2024.v23i03.002.Search in Google Scholar

8. Maripi, S. Nano Catalyst is an Efficient, Recyclable, Magnetically Separable and Heterogeneous Catalyst. Int. J. Sci. Technol. Eng. 2024, 12 (12), 2262–2265. https://doi.org/10.22214/ijraset.2024.66192.Search in Google Scholar

9. Jain, S.; Kassaye, S. Efficient Production of Platform Chemicals from Lignocellulosic Biomass by Using Nanocatalysts: A Review. React. (Auckland) 2024. https://doi.org/10.3390/reactions5040044.Search in Google Scholar

10. Fiorio, J. L.; Gothe, M. L.; Kohlrausch, E. C.; Zardo, M. L.; Tanaka, A. A.; de Lima, R. B.; Marques da Silva, A. G.; García, M. A.; Vidinha, P.; Machado, G. Nanoengineering of Catalysts for Enhanced Hydrogen Production. Hydrogen 2022, 3 (2), 218–254. https://doi.org/10.3390/hydrogen3020014.Search in Google Scholar

11. He, J.; Tian, G.; Liao, D.; Li, Z.; Cui, Y.; Wei, F.; Zeng, C.; Zhang, C. Mechanistic Insights into Methanol Conversion and Methanol-Mediated Tandem Catalysis Toward Hydrocarbons. J. Energy Chem. 2025, 1–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jechem.2025.09.007.Search in Google Scholar

12. Durak, H. Comprehensive Assessment of Thermochemical Processes for Sustainable Waste Management and Resource Recovery. Processes 2023. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr11072092.Search in Google Scholar

13. Al-Hammadi, M.; Güngörmüşler, M. From Refuse to Resource: Exploring Technological and Economic Dimensions of Waste-To-Energy. Biofuel Bioprod. Biorefining 2025. https://doi.org/10.1002/bbb.2723.Search in Google Scholar

14. Tiwari, M.; Dirbeba, M. J.; Lehmusto, J.; Yrjas, P.; Vinu, R. Analytical and Applied Pyrolysis of Challenging Biomass Feedstocks: Effect of Pyrolysis Conditions on Product Yield and Composition. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2024. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaap.2024.106355.Search in Google Scholar

15. Lysne, A.; Saxrud, I.; Madsen, K. Ø.; Blekkan, E. A. Steam Reforming of Tar Impurities from Biomass Gasification with Ni-Co/Mg(Al)O Catalysts–Operating Parameter Effects. Fuels 2024, 5 (3), 458–475. https://doi.org/10.3390/fuels5030025.Search in Google Scholar

16. Han, D.; Shin, S.; Jung, H. S.; Cho, W.; Baek, Y. Hydrogen Production by Steam Reforming of Pyrolysis Oil from Waste Plastic over 3 Wt.% Ni/Ce-Zr-Mg/Al2O3 Catalyst. Energies 2023, 16 (6), 2656. https://doi.org/10.3390/en16062656.Search in Google Scholar

17. Chen, J.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Z.; Yue, J.; Tian, Y.; Zheng, C.; Zhang, J. Highly Efficient Transformation of Tar Model Compounds into Hydrogen by a Ni-Co Alloy Nanocatalyst During Tar Steam Reforming. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.3c08857.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

18. Lopez-Ruiz, J. A.; Boruah, B.; Strange, L. E.; Riedel, N. W. Low-Temperature Wastewater Electrolysis for H2 and Clean Water Generation. Meet. Abstr. 2024, MA2024-01 (34), 1728. https://doi.org/10.1149/ma2024-01341728mtgabs.Search in Google Scholar

19. Lu, C.; Liu, P.; Tian, R.; Lin, F.; Li, J.; Li, J.; Zou, X.; Li, J.; Gu, Y.-Y. Enhanced Photocathode Performance and Stability for solar-powered Hydrogen Production Through Sinws@Nc Composite. Mater. Lett. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matlet.2023.135719.Search in Google Scholar

20. Tatsuma, T. (Invited) Plasmonic Photocatalysis and Near-Field Photocatalysis. Meet. Abstr. 2024, MA2024-02 (68), 4810. https://doi.org/10.1149/ma2024-02684810mtgabs.Search in Google Scholar

21. Sundar, D.; Liu, C.-H.; Anandan, S.; Wu, J. J. Photocatalytic CO2 Conversion into Solar Fuels Using Carbon-based Materials–A Review. Molecules 2023. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules28145383.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

22. Pornrungroj, C. Complementary and Hybrid Approaches for Enhanced Solar Utilization in Synthetic Fuel Production. Meet. Abstr. 2024, MA2024-02 (10), 4981. https://doi.org/10.1149/ma2024-02104981mtgabs.Search in Google Scholar

23. Ma’aruf, M. A.; Mustapha, S.; Giriraj, T.; Muhammad, N. S.; Habib, M.; Abdulhaq, S. G. Sustainable Synthesis Strategies: Biofabrication’s Impact on Metal and Metal Oxide Nanoparticles. Afr. J. Environ. Nat. Sci. Res. 2024, 7 (2), 229–252. https://doi.org/10.52589/ajensr-jtfpyhuk.Search in Google Scholar

24. Alam, M. W.; Ramya, A.; Nabi, S.; Nivetha, A.; Abebe, B.; Almutairi, H. H.; Sadaf, S.; Almohish, S. M. Advancements in green-synthesized Transition Metal/metal-oxide Nanoparticles for Sustainable Wastewater Treatment: Techniques, Applications, and Future Prospects. Mater. Res. Exp. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1088/2053-1591/ad86a4.Search in Google Scholar

25. Valdebenito, G.; Gonzaléz-Carvajal, M.; Santibañez, L.; Cancino, P. Metal–Organic Frameworks (MOFs) and Materials Derived from MOFs as Catalysts for the Development of Green Processes. Catalysts 2022, 12 (2), 136. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal12020136.Search in Google Scholar

26. King, M. E.; Wang, C.; Fonseca Guzman, M.; Ross, M. B. Plasmonics for Environmental Remediation and Pollutant Degradation. Chem Catal. 2022, 2 (8), 1880–1892. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.checat.2022.06.017.Search in Google Scholar

27. Ashour, B.; Ali, S. M.; Farahat, M. G.; El-Sherif, R. M. Fabrication and Detection of Carbon-based Nanomaterials Derived from Biomass Sources: Processes and Applications. Egypt. J. Chem. 2024. https://doi.org/10.21608/ejchem.2024.332694.10706.Search in Google Scholar

28. Deng, M.; Xia, M.; Wang, Y.; Ren, X.; Li, S. Synergetic Catalysis of p-d Hybridized Single-atom Catalysts: First-Principles Investigations. J. Mater. Chem. A, Mater. Energy and Sustain. 2022, 10 (24), 13066–13073. https://doi.org/10.1039/d2ta03368b.Search in Google Scholar

29. Xu, G.; Nanda, S.; Guo, J.; Song, Y.; Kozinski, J. A.; Dalai, A. K.; Fang, Z. Red mud supported Ni-Cu bimetallic material for hydrothermal production of hydrogen from biomass, 2024.10.2139/ssrn.4625504Search in Google Scholar

30. Tian, J.; Zhu, Y.; Zhao, X.; Yao, J.; Yang, L.; Du, C.-Y.; Lv, Z.; Hou, M.; Zhang, S.; Ma, X.; Cao, C. Chemical Vapor Deposition Towards Atomically Dispersed Iron Catalysts for Efficient Oxygen Reduction. J. Mater. Chem. A, Mater. Energy and Sustain. 2023, 11 (10), 5288–5295. https://doi.org/10.1039/d2ta08943b.Search in Google Scholar

31. Prabu, S. B.; Vinu, M.; Mariappan, A. S. T.; Dharman, R.; Oh, T. H.; Chiang, K. Synthesis of Cr(OH)3/ZrO2@Co-based metal-organic Framework from Waste Poly(Ethylene Terephthalate) for Hydrogen Production via Formic Acid Dehydrogenation at Low Temperature. Ceram. Int. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2024.04.159.Search in Google Scholar

32. Liao, D.; Tian, G.; Xiaoyu, F.; Li, Z.; Sun, Y.; Chang, W.; Li, Z.; Li, L.; Zeng, C.; Wei, F.; Zhang, C. Toward an Active Site–Performance Relationship for Oxide-Supported Single and Few Atoms. ACS Catal. 2025, 15 (10), 8219–8229; https://doi.org/10.1021/acscatal.5c00981.Search in Google Scholar

33. Ma, H.; Fu, P.; Zhao, J.; Lin, X.; Wu, W.; Yu, Z.; Xia, C.; Wang, Q.; Gao, M.; Zhou, J. Pretreatment of Wheat Straw Lignocelluloses by Deep Eutectic Solvent for Lignin Extraction. Molecules 2022, 27 (22), 7955; https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27227955.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

34. Basu, S.; Banik, B. K. Nanoparticles as Catalysts: Exploring Potential Applications. Current Organocatalysis 2024. https://doi.org/10.2174/0122133372285610231227094959.Search in Google Scholar

35. Choudhary, S. Role of Nano Catalysts in Green Chemistry. J. Sci. Innovat. Nat. Earth 2024, 4 (4), 08–11. https://doi.org/10.59436/jsiane.273.2583-2093.Search in Google Scholar

36. Xie, J.; Xi, Y.; Gao, W.; Zhang, H.; Wu, Y.; Yang, H.; Peng, Y.; Li, F.; Li, Z.; Li, C. Hydrogenolysis of Lignin Model Compounds on Ni Nanoparticles Surrounding the Oxygen Vacancy of CeO2. ACS Catal. 2023, 9577–9587. https://doi.org/10.1021/acscatal.3c02303.Search in Google Scholar

37. Muhammad, P.; Zada, A.; Rashid, J.; Hanif, S.; Gao, Y.; Li, C.; Li, Y.; Fan, K.; Wang, Y. Defect Engineering in Nanocatalysts: from Design and Synthesis to Applications. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.202314686.Search in Google Scholar

38. Jayabal, R. Microalgae-Bacteria Systems in Wastewater Treatment and Biofuel Production: Challenges, Advances, and Future Perspectives. Algal Res. 2025, 91, 104228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.algal.2025.104228.Search in Google Scholar

39. Jiang, F.; Xu, X.; Feng, X.; Wang, M.; Zhang, C.; Mao, Y.; Xing, M.; Li, P.; Han, Q.; Pan, H.; Wang, J. Ceramsite Catalyst Derived from Printed Circuit Board Sludge for Catalytic Ozonation Treatment of Coking Wastewater: Performance and Mechanism. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 497, 139613; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2025.139613.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

40. Jayabal, R.; Sivanraju, R. Environmental Impact of Waste Peel Biodiesel–Butylated Hydroxytoluene Nanoparticle Blends on Diesel Engine Emissions. Energy Sci. Eng. 2025, 13 (2), 742–751, Portico https://doi.org/10.1002/ese3.2033.Search in Google Scholar

41. Saravanan, T. S.; Shnain, A. H.; Sharma, H.; Naveena, S. S.; Rajurkar, A.; Sherje, N.; Nathan, S. R. Hydrogen Production via Electrolyzers: Enhancing Efficiency and Reducing Costs. E3S Web of Conf. 2024, 591, 06003. https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/202459106003.Search in Google Scholar

42. Khosravani, H.; Meshksar, M.; Koohi-Saadi, M.; Taghadom, K.; Rahimpour, M. R. Synthesis, Characterization, and Application of bio-templated Ni–Ce/Al2O3 Catalyst for Clean H2 Production in the Steam Reforming of Methane Process. J. Energy Inst. 2023, 108, 101203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joei.2023.101203.Search in Google Scholar

43. Ma, Y.; Gao, N. S.; Quan, C.; Sun, A.; Olazar, M. High-Yield H2 Production from HDPE Through Integrated Pyrolysis and plasma-catalysis Reforming Process. Chem. Eng. J. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2023.147877.Search in Google Scholar

44. Hsu, C.-Y.; Chung, W.-T.; Lin, T.-M.; Yang, R.-X.; Chen, S. S.; Wu, K. C.-W. Coking-Resistant NiO@CeO2 Catalysts Derived from Ce-MOF for Enhanced Hydrogen Production from Plastics. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2023.08.080.Search in Google Scholar

45. Kani, N. C.; Chauhan, R.; Olusegun, S.; Sharan, I.; Katiyar, A.; House, D.; Lee, S.-W.; Jairamsingh, A.; Bhawnani, R.; Choi, D.; Nielander, A. C.; Jaramillo, T. F.; Lee, H.; Oroskar, A. R.; Srivastava, V. C.; Sinha, S.; Gauthier, J. A.; Singh, M. R. Sub-Volt Conversion of Activated Biochar and Water for H2 Production near Equilibrium via biochar-assisted Water Electrolysis. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 2024, 102013. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xcrp.2024.102013.Search in Google Scholar

46. Liang, T.-Y.; Senthil Raja, D.; Chin, K. C.; Chin, K. C.; Huang, C.-L.; A, S.; Sethupathi, P.; Leong, L. K.; Tsai, D.-H.; Lu, S.-Y. Bimetallic Metal–Organic Framework-Derived Hybrid Nanostructures as High-Performance Catalysts for Methane Dry Reforming. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12 (13), 15183–15193. https://doi.org/10.1021/ACSAMI.0C00086.Search in Google Scholar

47. Meshksar, M.; Kiani, M. R.; Mozafari, A.; Makarem, M. A.; Rahimpour, M. R. Promoted Nickel–Cobalt Bimetallic Catalysts for Biogas Reforming. Top. Catal. 2021, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11244-021-01532-Y.Search in Google Scholar

48. Parapat, R. Y.; Schwarze, M.; Ibrahim, A.; Tasbihi, M.; Schomäcker, R. Efficient Preparation of Nanocatalysts. Case Study: Green Synthesis of Supported Pt Nanoparticles by Using Microemulsions and Mangosteen Peel Extract. RSC Adv. 2022, 12 (53), 34346–34358. https://doi.org/10.1039/d2ra04134k.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

49. Girotra, V.; Kaushik, P.; Vaya, D. Exploring Sustainable Synthesis Paths: a Comprehensive Review of Environmentally Friendly Methods for Fabricating Nanomaterials Through Green Chemistry Approaches. Turk. J. Chem. 2024, 48 (5), 703–725. https://doi.org/10.55730/1300-0527.3691.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

50. Pérez-Hernández, H.; Pérez-Moreno, A.; Sarabia-Castillo, C. R.; García-Mayagoitia, S.; Medina-Pérez, G.; López-Valdez, F.; Campos-Montiel, R. G.; Jayanta-Kumar, P.; Fernández-Luqueño, F. Ecological Drawbacks of Nanomaterials Produced on an Industrial Scale: Collateral Effect on Human and Environmental Health. Water, Air, Soil Pollut. 2021, 232 (10), 435. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11270-021-05370-2.Search in Google Scholar

51. Joshy, D.; Jijil, C. P.; Ismail, Y. A.; Periyat, P. Spent zinc-carbon Battery Derived Magnetically Retrievable Fenton-like Catalyst for Water Treatment - a Circular Economical Approach. J. Water Proc. Eng. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwpe.2024.104812.Search in Google Scholar

52. Damian, C. S.; Devarajan, Y.; J, R.; T, R. Nanocatalysts in Biodiesel Production: Advancements, Challenges, and Sustainable Solutions. ChemBioEng Rev. 2025, 12 (2), Portico https://doi.org/10.1002/cben.202400055.Search in Google Scholar

53. Pankhedkar, N.; Sartape, R.; Singh, M. R.; Gudi, R. D.; Biswas, P.; Bhargava, S. System-Level Feasibility Analysis of a Novel Chemical Looping Combustion Integrated with Electrochemical CO2 Reduction. Sustain. Energy Fuels 2024. https://doi.org/10.1039/d4se00770k.Search in Google Scholar

54. Wang, L; Jin, J.; Li, W.; Li, C.; Zhu, L.; Zhou, Z.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, X.; Yuan, L. Highly Selective Catalytic Oxidation of Methane to Methanol using Cu–Pd/Anatase. Energy Environ. Sci. 2025, 17 (23), 9122–9133; https://doi.org/10.1039/D4EE02671C.Search in Google Scholar

55. Rastogi, S.; Sethi, P.; Panwar, N.; Yadav, P.; Verma, R.; Мadan, А. К. Harnessing Nanotechnology to Transform Waste Reclamation for Enhanced Efficiency and Environmental Impact. Adv. Environ. Eng. Green Technol. Book Ser. 2025, 349–392. https://doi.org/10.4018/979-8-3693-7282-1.ch016.Search in Google Scholar

56. Pa, F. C.; Norazman, N. N. U.; Zaki, R. M. Preparation & Characterization of Biochar from Rice Husk by Pyrolysis Method. Int. J. Nanoelectron. Mater. 2024, 17 (December), 113–119. https://doi.org/10.58915/ijneam.v17idecember.1614.Search in Google Scholar

57. Kordouli, E.; Vourtsani, P.-I.; Mourgkogiannis, N.; Zafeiropoulos, J.; Bourikas, K.; Kordulis, C. Green Diesel Production Catalyzed by MoNi Catalysts Supported on Rice Husk Biochar. Catalysts 2024, 14 (12), 865. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal14120865.Search in Google Scholar

58. D, C. S.; Devarajan, Y.; Subbiah, G.; Ganesan, S.; Dash, A. K.; Aadiwal, V.; Gill, A. Nano-Enhanced Sodium Carbonate for Efficient Carbon Capture: a Review of Performance Advancements and Economic Viability. Rev. Inorg. Chem. 2025. https://doi.org/10.1515/revic-2025-0032.Search in Google Scholar

59. Li, X.; Liu, P.; Wang, Z.; Liu, P.; Wei, X.; Wu, Y.; Lei, T. Catalytic Cracking of Biomass Tar for Hydrogen-Rich Gas Production: Parameter Optimization Using Response Surface Methodology Combined with Deterministic Finite Automaton. Renew. Energy 2025, 241, 122368. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2025.122368.Search in Google Scholar

60. Christian, U.; Bhalerao, Y. P.; Patel, J.; Mehta, P.; Tejani, G. G.; Singh, S.; Varshney, D. A Comprehensive Review of Waste-to-energy Technologies: Pathways for Large Scale Applications. Appl. Chem. Eng. 2024, 7 (4). https://doi.org/10.59429/ace.v7i4.5578.Search in Google Scholar

61. Rahman, K. F.; Abrar, M.; Tithi, S. S.; Kabir, K. B.; Kirtania, K. Life Cycle Assessment of Hydrothermal Carbonization of Municipal Solid Waste for waste-to-energy Generation. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 370, 122850. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2024.122850.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

62. Bharathi, C.; Rajeswari, R.; Janaki, P.; Sivamurugan, A. P.; Govindan, S. K.; Sengodan, R.; Priya, R. S.; Sangeetha, M.; Thenmozhi, S.; Chiranjeevirajan, N.; Sharmila, R.; Ramya, B.; Balamurugan, R. Bio-Mediated Synthesis of Nanoparticles: a New Paradigm for Environmental Sustainability. Plant Sci. Today 2025, 12 (sp1). https://doi.org/10.14719/pst.5192.Search in Google Scholar

63. Parab, A. R.; Ramlal, A.; Gopinath, S. C. B.; Subramanıam, S. Forging the Future of Nanotechnology: Embracing Greener Practices for a Resilient Today and a Sustainable Tomorrow. Front. Nanotechnol. 2025, 6. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnano.2024.1506665.Search in Google Scholar

64. Jayabal, R. Advancements in Catalysts, Process Intensification, and Feedstock Utilization for Sustainable Biodiesel Production. Results Eng. 2024, 24, 103668. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rineng.2024.103668.Search in Google Scholar

65. Ning, H.; Jiang, B.; Yue, L.; Wang, Z.; Zuo, S.; Wang, Q. Quantitative Sulfur Poisoning of Nanocrystal PtO2/KL-NY and its Deactivation Mechanism for Benzene Catalytic Oxidation. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ces.2024.120086.Search in Google Scholar

66. Hallot, G.; Chan, Y. S.; Menard, F.; Port, M.; Gomez, C. Continuous Flow Synthesis of Bismuth Nanoparticles: a Well-Controlled Nano-Object Size Thanks to Successful Scaling-Up. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2025. https://doi.org/10.1021/acssuschemeng.4c03619.Search in Google Scholar

67. Antonietti, M.; Pelicano, C. M. Translating Laboratory Success into the large-scale Implementation of Photocatalytic Overall Water Splitting. Front. Sci. 2024, 2. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsci.2024.1507745.Search in Google Scholar

68. Zhang, D.; Jia, X.; Liu, H.; Wang, Y.; Ye, S.; Jiang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Li, W.; Yang, W.; Xu, H.; Cheng, D.; Hashimoto, Y.; Tomai, T.; Li, H. Cloud Synthesis: a Global Close-Loop Feedback Powered by Autonomous AI-Driven Catalyst Design Agent, 2024.10.26434/chemrxiv-2024-jsqqnSearch in Google Scholar

69. Wang, C.; Cheng, X.; Luo, K. H.; Nandakumar, K.; Wang, Z.; Ni, M.; Bi, X.; Zhang, J.; Wang, C. A Guided Review of Machine Learning in the Design and Application for Pore Nanoarchitectonics of Carbon Materials. Int. J. High Speed Electron. Syst. 2025, 165 (1), 101010; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mser.2025.101010.Search in Google Scholar

70. Mudofir, M.; Astuti, S. P.; Purnasari, N.; Sabariyanto, S.; Yenneti, K.; Ogan, D. D. D. Waste Harvesting: Lessons Learned from the Development of Waste-to-Energy Power Plants in Indonesia. Int. J. Energy Sect. Manag. 2025, 19, 1097–1130; https://doi.org/10.1108/IJESM-07-2024-0014.Search in Google Scholar

71. D, C. S.; Channappagoudra, M.; Samantaray, S.; Mishra, A. K.; Juneja, G.; Devarajan, Y.; Chand, K. Transforming Waste to Energy: Nanocatalyst Innovations Driving Green Hydrogen Production. Rev. Inorg. Chem. 2025. https://doi.org/10.1515/revic-2025-0016.Search in Google Scholar

72. Chen, Z. Y.; Brockway, P. E.; Few, S.; Paavola, J. The Impact of Emissions Trading Systems on Technological Innovation for Climate Change Mitigation: a Systematic Review. Clim. Policy 2024, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2024.2443464.Search in Google Scholar

73. Rani, M.; Rani, M.; Singh, S.; Gupta, A.; Kumar, R. Role of Nanotechnology in Enhancing Waste Reclamation. Adv. Environ. Eng. Green Technol. Book Ser. 2025, 153–176. https://doi.org/10.4018/979-8-3693-7282-1.ch009.Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.