Abstract

The syntheses and application of M@zeolite hybrids with the structure of metal being encapsulated into zeolite crystals have attracted extensive attention due to their high activity and resistance to sintering under harsh conditions as the catalysts. Remarkable achievements have been made in the structure construction, particularly in the way of so called “one pot synthesis”. Herein, we exclusively summarize the recent advance of the metal encapsulation in the “in situ synthesis” technique, with which help the researchers constructing their metal-embedding catalysts more active and thermal resistant.

1 Introduction

Metal-based materials with high metal dispersion have been widely investigated and applied as catalysts for various chemical reactions, such as dry reforming of methane, 1 propane direct dehydrogenation, 2 , 3 methane oxidation to methanol. 4 It is acknowledged that the metal existing as atoms, clusters and the nanoparticles with small size over support surface are not only more catalytic active due to their special chemical environment, but also more efficient than the larger ones in the utilization. However, these little metal species generally suffer from rapid sintering at hush conditions due to the intrinsic property, i.e. spontaneously decreasing their surface energy via Ostwald ripening route 5 , 6 and Coalescence route. 7 , 8 To overcome this problem, two strategies have been developed by the researchers. One strategy is strengthening the interaction of the metal species with the support, by means of support-metal strong interaction “SMSI” 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 effect, to inhibit the metal species migration. The other one is encapsulating the metal species into zeolite crystals, by means of the confining effect of zeolite framework, 3 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 hindering the metal species migration.

To encapsulate metal species in zeolite crystals, two typical methods, which is called as “post-treatment” and “one pot synthesis”, respectively, have been applied in the investigations. The former one includes the steps of loading the required metals (Ms) on a now available zeolite, and the subsequent recrystallizing the resultant Ms/zeolite hybrid under hydrothermal conditions. 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 The latter one is also called as “in situ synthesis”, since it is realized by in situ encapsulating metal species into the zeolite crystals by hydrothermal synthesis (HT) from a gel containing both of silicon source and the metal source. 25 , 26 In this decade, to meet the requirement of industrial application of the catalyst in harsh reaction conditions, restraining the metal sintering, a lot of investigations concerning the encapsulation of metal species in zeolite crystals and the utilization of the metal-confined materials as catalysts have been reported in literatures. 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 Accordingly, numerous review papers concerning the metal encapsulation whereas being focused at definite reaction 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 and those being focused at the metal encapsulation but covering the “post-treatment” 26 , 54 , 55 , 56 were also published. However, to the best of our knowledge, no review paper exclusively summarizing the recent advance of the metal encapsulation in the “in situ synthesis” technology appears in the literature though remarkable performances have been gotten for the catalyst prepared by “in situ synthesis” method. 16 , 57 , 58 We noticed that, the number of papers concerning this method increased fast, which is the reason why we write this paper. Herein, we summarize the advance of metal encapsulation realized by “in situ synthesis” method in the last 4 years, with the focus on the synthesis techniques and the physicochemical structure of the product, in particular, on the metal aggregation state, the metal percentage and crystal size of the M@zeolite hybrid, as these factors significantly influence the performance of catalysts to be prepared. We hope these intensive messages would be helpful for constructing the metal-embedding catalysts with more active and thermal resistant feature.

2 Encapsulation of metal species into zeolite crystals by in situ synthesis

According to the electron structure of metal that is incorporated to the zeolites, the investigation results were individually summarized in Sections 2.1 and 2.2, where respectively deal with noble metals and non-noble metals (transition metals and main group metals). Whereas, in the case of metal encapsulation reaching to single atomic level, it will be summarized in Section 3, where deal with the heteroatom-zeolite syntheses. As for Section 2.3, it summarized the simultaneous encapsulation of noble metals and non-noble metals in the “one pot synthesis”.

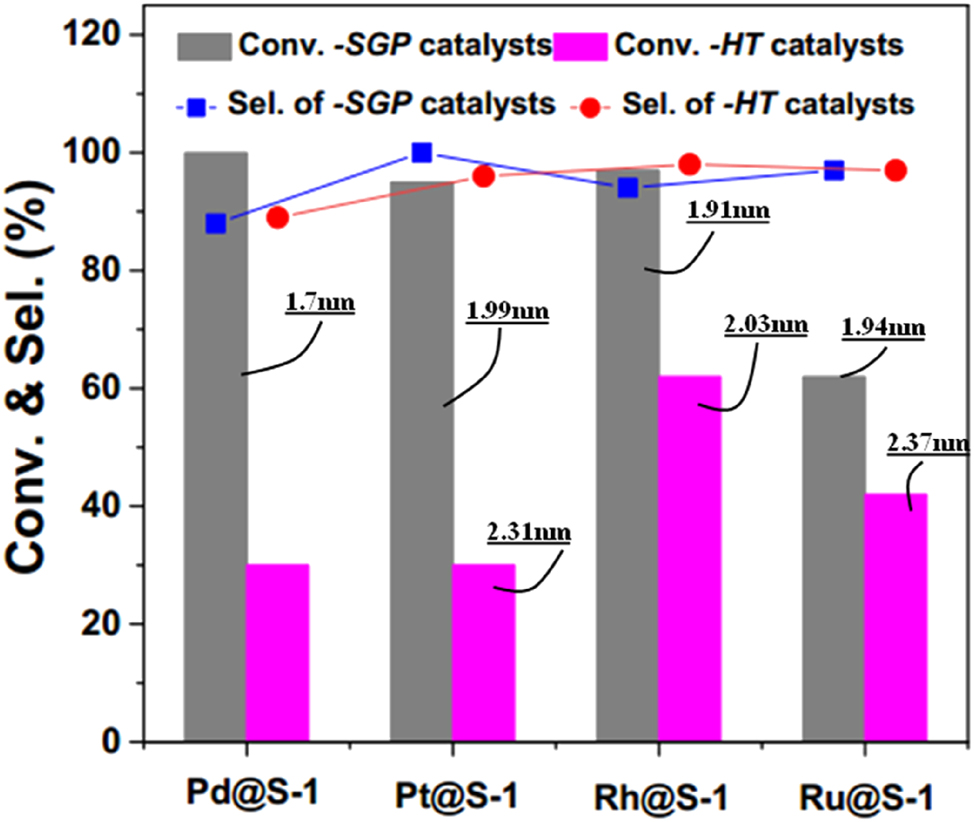

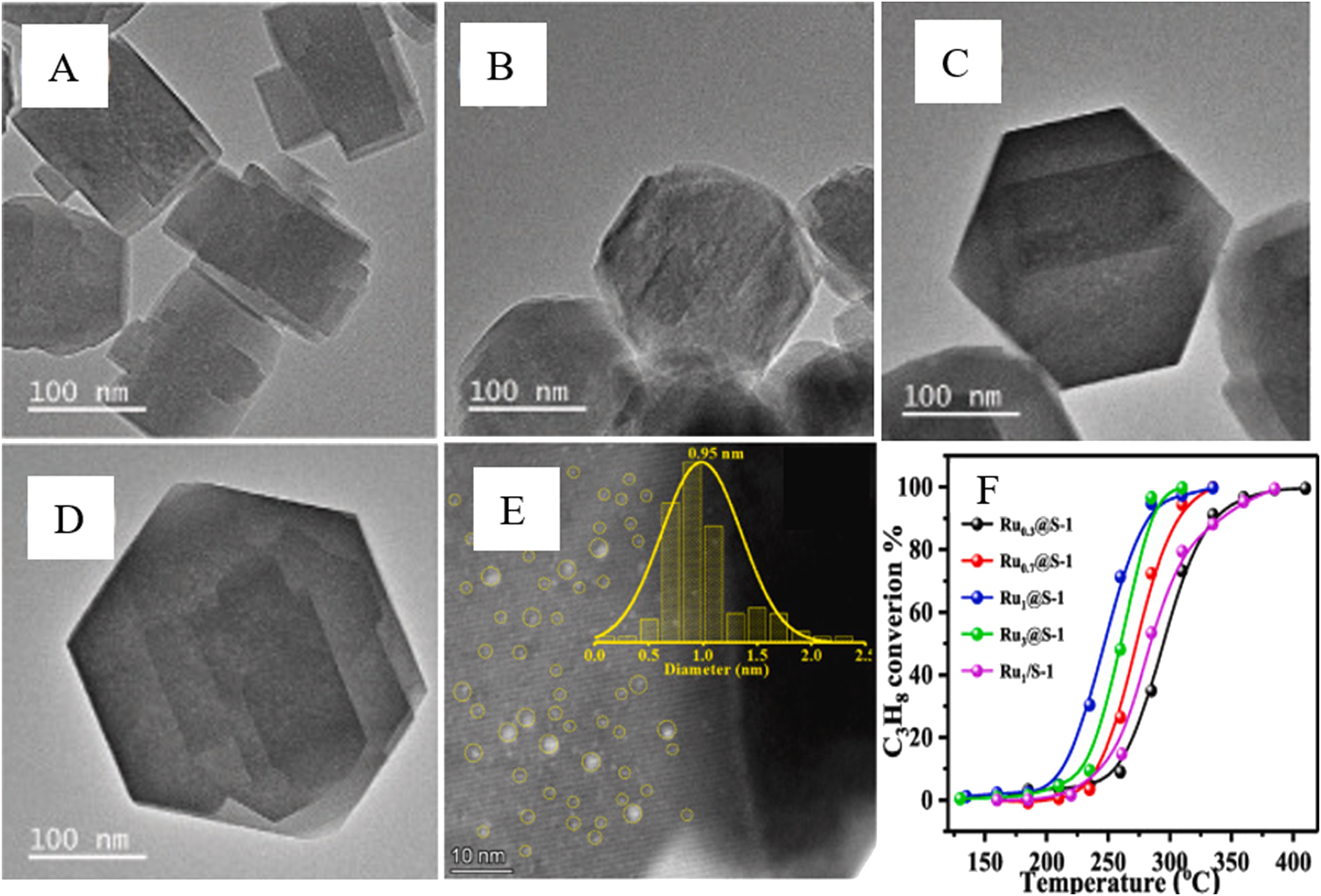

2.1 Encapsulation of noble metals

Table 1 represents the results of noble metals (Pd, Pt, Ph, and Ru) encapsulation to the S-1 zeolite crystals. It can be found that all of the syntheses encapsulating the noble metals to the zeolite crystals, applied ethylene diamine (EDA) as the organic ligand, as the latter one could stabilize the metal precursors under the hydrothermal conditions and help the metal incorporate to the zeolite. 26 To realize the noble metals encapsulation into zeolite crystals, Li et al. 59 have proposed a new strategy encapsulating the metals in a highly concentrated soft gel precursor (SGP). That is, vaporized the starting gel at 70 °C for 1 h in vacuum prior to hydrothermal crystallization, with which to remove harmful ethanol and excessive amount of water to the synthesis. They found that this method significantly improved the metal utilization with respect to the HT method. For instance, the metal utilization for the incorporation of Pd to S-1 in the SGP method is 98.7 %, which is nearly double higher than that (52.9 %) achieved in HT method. This method is also succeeded for the incorporation of noble metals to NaA, SSZ-13, and Beta zeolites. Figure 1 shows the average sizes of metal species in M@S-1 hybrids and the corresponding catalytic results for P-nitrochlorobenzene hydrogenation of the hybrids synthesized by the SGP or HT methods. Both of them indicate that the M@zeolite hybrids (M = Pd, Pt, Rh, Ru) prepared by the SGP method is superior than that prepared by the HT method. Starting from the gels with a molar ratio of 1 SiO2: 0.4 TPAOH: 35 H2O: x [Ru (NH2CH2CH2NH2)3]Cl3, where the (NH2CH2CH2NH2)3]Cl3 comes from dissolving RuCl3 into a mixture of EDA and deionized water, Tao et al. 60 incorporated different amount (0.3, 0.7, 1.0 and 3.0 wt%) of Ru to S-1 in HT, according to the literature. 61 With the Ru loading amount increasing from 0.7 to 3.0 wt%, the crystals size of their Ru x @S-1 increased from ca. 150–280 nm, as shown in Figure 2(A–D). Among the Ru x @S-1 samples, the Ru1@S-1 that possesses an average Ru species size of 0.95 nm (Figure 2E) represented the highest catalytic activity for propane oxidation (Figure 2F).

Summary of noble metals encapsulation.

| M | Method | Synthesis conditionsa | Metal content (wt%)/Average sizeb | Metal utilization (%)c | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pd | Concentrates the gel before crystallization | The gel with mole ratio of 1.0 TEOS: 0.4 TPAOH: 35 H2O:0.0057 PdCl2:0.15 EDAd was vaporized at 70 °C for 1 h to remove water and ethanol, and the resultant material was crystallized under static pressure at 240 °C for 1.5 h. The product was calcined in the air at 550 °C for 8 h and then reduced at 200 °C for 2 h by 10 % H2/Ar. | 0.44/1.7 nm in S-1; 0.44/1.9 nm in ZSM-5; 0.41/2.1 nm in SSZ-13; 0.39/2.0 nm in NaA; 0.40/1.9 nm in Beta |

98.7 for Pd@S-1; 98.7 for Pd@ZSM-5; 69.6 for Pd@SSZ-13; 66.2 for Pd@NaA; 67.9 for Pd@Beta |

Li et al. |

| Pt | The gel with mole ratio of 1.0 TEOS: 0.4 TPAOH: 35 H2O:0.0031 PtCl4:0.15 EDA was treated in the same way as that mentioned above but the calcined was done at 350 °C for 6 h. | 0.44/2.0 nm in S-1 | 98.6 for Pt@S-1 | ||

| Rh | The gel with mole ratio of 1.0 TEOS: 0.4 TPAOH: 35 H2O:0.006 RhCl3:0.15 EDA, was treated in the same way as that mentioned above but the calcined was done at 550 °C for 3 h. | 0.45/1.9 nm in S-1 | 98.8 for Rh@S-1 | ||

| Ru | The gel with mole ratio of 1.0 TEOS: 0.4 TPAOH: 35 H2O:0.006 RuCl3:0.15 EDA was treated in the same way as that mentioned above but the calcined was done at 350 °C for 2 h. | 0.30/1.9 nm in S-1 | 67.2 for Ru@S-1 | ||

| Pd | HT | Each gels was directly crystallized statically at 170 °C for 72 h. | 0.39/2.0 nm in S-1 | 52.9 for Pd@S-1 | |

| Pt | 0.38/2.3 nm in S-1 | 51.5 for Pt@S-1 | |||

| Rh | 0.29/2.0 nm in S-1 | 38.5 for Rh@S-1 | |||

| Ru | 0.27/2.4 nm in S-1 | 36.6 for Ru@S-1 | |||

| Pt | The gel with mole ratio of 1.0 TEOS: 0.4 TPAOH: 35 H2O: 0.00131 H2PtCl6 was statically crystallized at 175 °C for 72 h in the presence of EDA. | 0.41/3.3 nm in S-1 | –e | Li et al. | |

| Rh | The gel with mole ratio of 1.0 TEOS:0.4 TPAOH:35 H2O:0.004 RhCl3 was crystallized at 170 °C for 72 h in the presence of EDA, and the solid was calcined at 550 °C for 2 h. | 0.35/single-atom in S-1 | – | Zeng et al. | |

| Ru | The gel with molar ratio of 1 SiO2: 0.4 TPAOH: 35 H2O: 0.005 [Ru(NH2CH2CH2NH2)3]Cl3 was statically crystallized at 170 °C for 72 h and resultant solid was calcined at 500 °C for 4 h. | 1.0/1.0 nm in S-1 | – | Tao et al. |

-

aThe synthesis conditions given in the second column is that of encapsulating noble metals in silicalite-1 zeolite; baverage size of the metal particles being dispersed in the zeolite crystals; cthe percentage of noble metals being remained in the solid products; dethylenediamine; eunknown.

Comparison of the Pd@S-1, Pt@S-1, Rh@S-1 and Ru@S-1 catalysts prepared by SGP and HT methods in average size of metal particles and in the catalytic property for hydrogenation of P-nitrochlorobenzene. Copyright 2022 ACS Publications.

TEM images of xRu@S-1 (x = 0.3, 0.7, 1.0 and 3.0 wt%, A–D), size distribution of Ru species in Ru1@S-1 measured by STEM (E), and catalytic activity of the xRu@S-1 samples for propane oxidation (F). Copyright 2022 Elsevier.

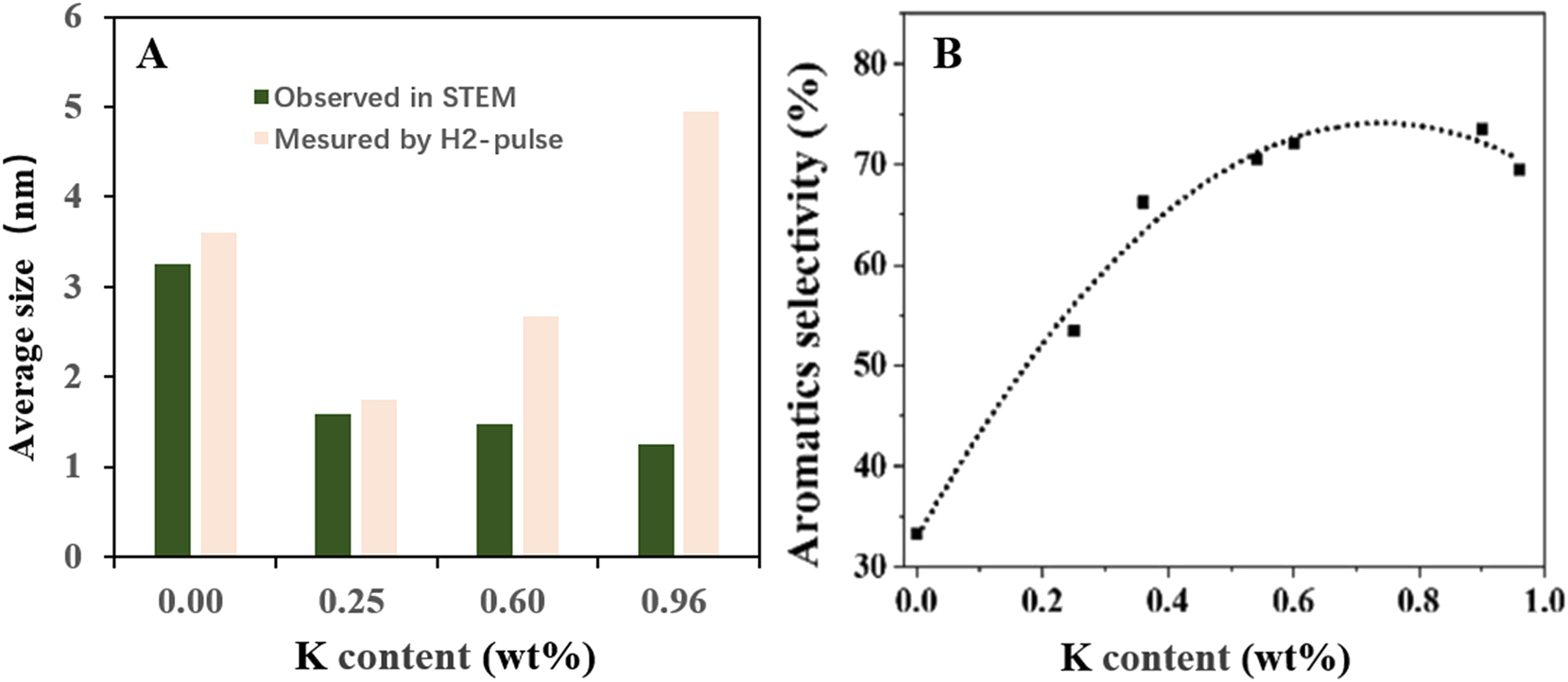

Li et al. 62 have investigated the effect of potassium addition to the gels on the Pt@S-1 synthesis. For the Pt@S-1 and KPt@S-1 composites being synthesized in HT method from the gels with mole composition 1.0 TEOS (ethyl orthosilicate): 0.4 TPAOH: 35 H2O: 0.00131 H2PtCl6: x KCl (0 < x ≤ 0.066), by characterizing the resultant synthesis products in H2-pulse chemisorption and in STEM, the authors found that the Pt dispersion is significantly influenced by the KCl addition amount to the gel. As shown in Figure 3A, with the K content increasing in the range of 0–0.96 wt%, the average Pt particle size observed in STEM in the resultant KPt@S-1 composites monotonically decreased, while those measured by H2-pulse chemisorption got minimum value for the K0.25Pt@S-1 sample containing 0.25 wt% of K (Figure 3A). May be due to other physicochemical features, the K0.60Pt@S-1 composite is more stable, active (not shown) and selective than the other samples to the n-hexane aromatization reaction (Figure 3B).

Variation of Pt particle average size (A) and the selectivity to aromatics for the KPt@S-1 catalysts with K contents (B). Copyright 2023 Elsevier.

Zeng et al. 58 encapsulated Rh inside S-1 zeolite in HT method with the assistance of EDA. According to characterization of the resultant materials by HRTM and EXAFS, it was found that the dispersion of Rh in S-1 crystals for the Rh@S-1 containing 0.35 wt% of Rh reached to single-atom level. The authors also confined series non-noble metal together with Rh inside in S-1 crystals with the one pot synthesis, which will be described in Section 2.3.

2.2 Encapsulation of non-noble metals

Like noble metals, non-noble metals with low-cost, such as Mn, Fe, Co, Ni, Cu and Zn, are also widely applied as active component catalyzing reactions, and hence how embedding them to zeolite crystals is also an important project. This section summarizes the corresponding synthesis method, crystal size of the N@S-1 hybrid and average size of metal, as shown in Table 2.

Summary of non-noble metals (N) encapsulation.

| N | Method | Synthesis conditions | Post treatment conditions | Average size of metal (nm) | Crystal size of N@S-1 (nm) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cu | HT, using tetraethylenepent-amine (TEPA) as ligand. | TPAOH, water and TEOS was stirred for 6 h, then CuSO4-TEPA was added and stirred for 30 min. The mixture was statically crystallized at 180 °C for 24 h. | The resultant solid was calcined at 600 °C for 4 h | 2–4 | 500 | Hong et al. |

| TPAOH, TEOS and water were mixed and stirred at 60 °C for 1.5 h, then Cu(NO3)2-TEPA solution was added. The mixture was statically crystallized at 170 °C for 48 h. | The resultant solid was calcined at 600 °C for 6 h, then reduced at 400 °C for 2 h by H2/N2 | 1.8 | 960 | Lin et al. | ||

| HT, using EDA as ligand. | TPAOH, TEOS and water were mixed and stirred for 1 h and then CuCl2-EDA was added. The mixture was statically crystallized at 170 °C for 24 h. | The resultant solid was calcined at 550 °C for 6 h | 1.9 | 500 | Feng et al. | |

| Zn | HT, using EDA as ligand | TPAOH, TEOS and water were mixed and stirred for 6 h, and then Zn(OAc)2-EDA was added. The mixture was statically crystallized at 170 °C for 72 h. | The resultant solid was calcined at 550 °C for 6 h | 0.8 | 930 | Xie et al. |

| HT, using Zn/SiO2 as sources without using organic amine | Zn(OAc)2 impregnated on SiO2 and then mixed with TPAOH and water for 6 h, statically crystallized at 180 °C for 4 h. | The resultant solid was calcined at 550 °C for 6 h | – | 420 | Zhang et al. | |

| Fe | HT, using dicyandiami-de (DCD) as ligand | TPAOH, EOS and water were stirred together for 6 h, [Fe(DCD)]Cl3 solution was added in and stirred for 0.5 h. The obtained mixture was statically crystallized at 170 °C for 72 h. | The resultant solid was calcined at 550 °C for 6 h | – | 500 | Guo et al. |

| Mn | HT, using TEPA as ligand | TPAOH, water and TEOS was stirred for 6 h, then [Mn-TEPA]Cl2 solution was added in and stirred for 30 min. The obtained mixture was statically crystallized at 170 °C for 72 h. | The resultant solid was calcined at 550 °C for 6 h, then reduced at 400 °C by H2 | – | 250 | Sun et al. |

| Ni | HT, using EDA as ligand | TEOS, TPAOH and water were mixed and stirred, then [Ni(EDA)](NO3)2 was added in and stirred for 6 h. The obtained mixture was statically crystallized at 180 °C for 72 h. | The resultant solid was calcined at 550 °C for 6 h | 6.8 in 5Ni@S-1; 7.3 in 7Ni@S-1; 8.5 in 10Ni@S-1 |

1,750 in 5Ni@S-1; 7,770 in 7Ni@S-1; 7,970 in 10Ni@S-1 | Xie et al. |

| Ni–Sna | HT, using EDA as ligand and precipitated silica gel as silica source | Precipitated silica gel prepared by H2SiF6 and NH3·H2O was hydrolyzed with the TPAOH solution and then Ni(NO3)2, SnCl4 and EDA were added in and stirred for 2 h. The obtained mixture was statically crystallized at 180 °C for 96 h. | The resultant solid was calcined at 550 °C for 6 h | 0.63 | 200 | Liu et al. |

-

aThe synthesis procedure of Ni@S-1 and Sn@S-1 is similar to that of Ni–Sn@S-1, except without adding SnCl4 or Ni(NO3)2.

Sun et al. 63 synthesized Mn@S-1 containing 0.25 wt% of Mn in HT method using MnCl2 as source of Mn and tetraethylenepentamine (TEPA) as organic ligand.

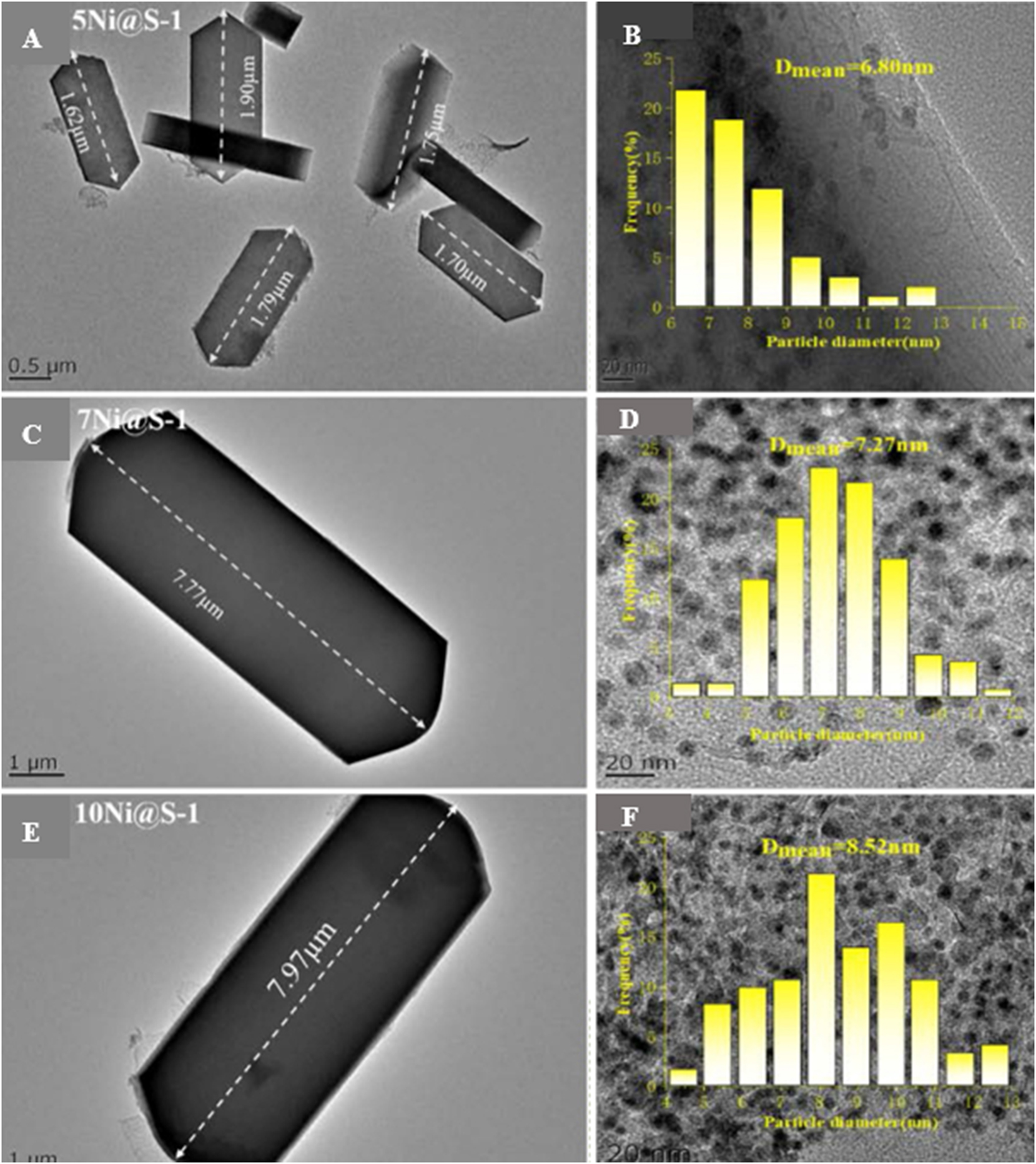

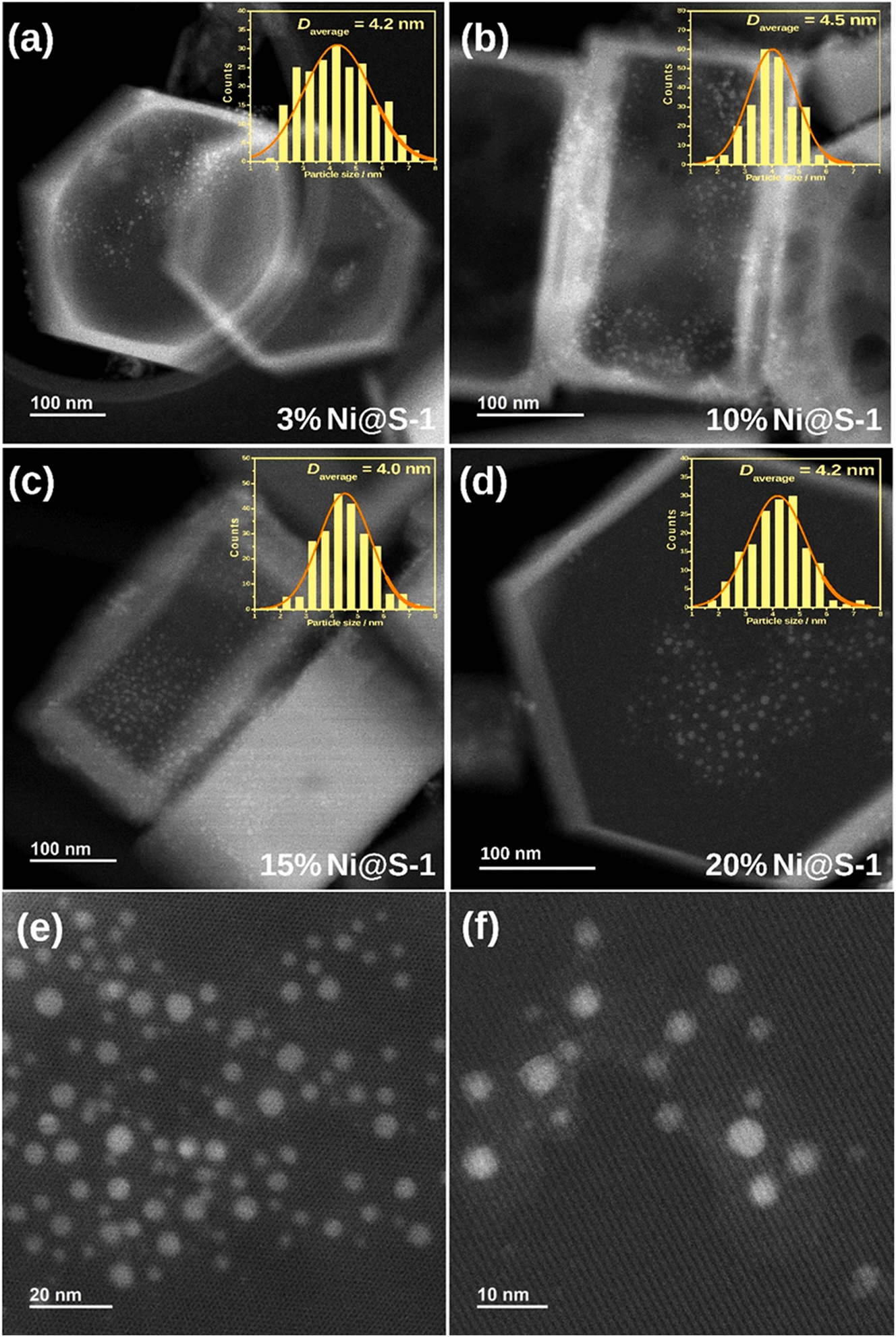

Guo et al. 64 encapsulated Fe nanoparticles within S-1 zeolite crystals using dicyandiamide (C2H4N4, DCD) as organic ligand from the gels with Fe/Si mole ratio (x) 0.005, 0.014, 0.021, and 0.029. They found that the crystal size of the resultant Fe@S-1 hybrid gradually increased from 290 nm to 500 nm with the Fe/Si mole ratio of the gel increasing. Similar phenomena also appeared in xNi@S-1 (x = 5, 7, 10) samples that is synthesized by Xie al. 65 (FT-IR) using EDA as organic ligand. It can be found that the crystal size of xNi@S-1 gradually increased from 1.79 to 7.97 μm when the Ni percentage increased from 5 to 10 in the gels. Moreover, with the Ni percentage increasing, the average particle sizes of Ni in the xNi@S-1 products increased from 6.80 nm to 8.52 nm (Figure 4).

HR-TEM images of the xNi@S-1 (x = 5, 7, 10 wt%, A, C, E), and size distribution of Ni species in the xNi@S-1 (B, D, F), calcined at 550 °C for 8 h and reduced by H2 at 200 °C for 1 h. Copyright 2023 Elsevier.

Liu et al. 66 synthesized Ni@S-1, Sn@S-1 as well as NixSny@S-1 (x = 1, 2 and y = 1, 2) using EDA as ligand. Different from other researches, their syntheses were realized using precipitated silica gel as silicon source in fluorine-containing system. It is worthy to note that just much less amount of TPAOH (SiO2: TPAOH = 1: 0.1) was used in these syntheses, which is about 1/4–1/3 of that using TEOS as the silicon source in the other literatures.

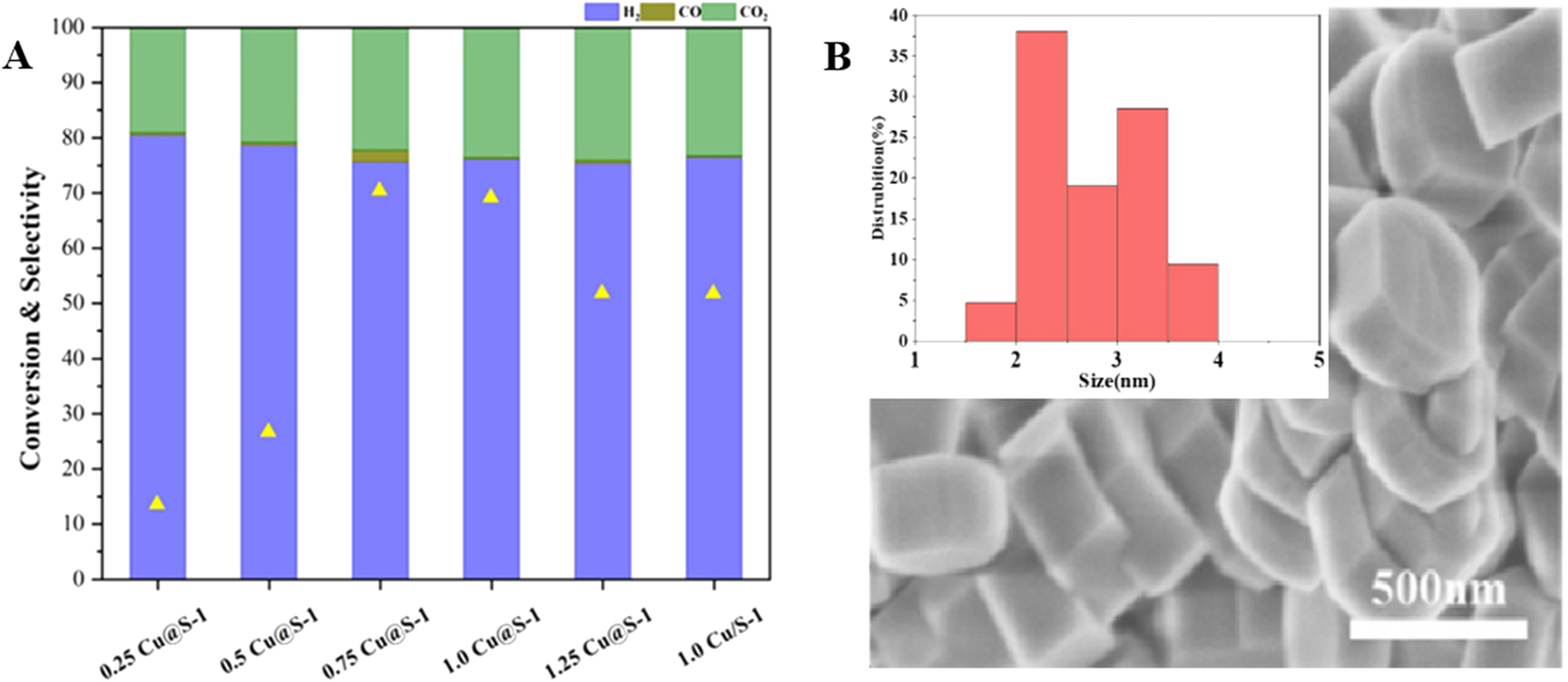

Hong et al. 67 encapsulated Cu nanoparticles in S-1 zeolite crystals in HT method using CuSO4 as source of Cu and TEPA as organic ligand. As the 1.0Cu@S-1 is more active for catalyzing methanol steam reforming (Figure 5A) than the other xCu@S-1 catalysts (x = 0.25, 0.5, 0.75 and 1.25 wt%), the authors just characterized this catalyst sample with SEM and STEM, which showed a coffin-like morphology and size of ∼500 nm for the 1.0Cu@S-1 hybrid and Cu particles being embedded into the S-1 zeolite crystals in the size ranging from 2 to 4 nm (Figure 5B). Lin et al. 68 encapsulated Cu species inside S-1 zeolite crystals in higher Cu loading amount (2.05 wt%) with HT method using Cu(NO3)2 as source of Cu and TEPA as organic ligand. For the Cu@S-1 sample synthesized in the conditions, the dispersion degree of Cu achieved 51.4 %, corresponding the Cu particles 1.8 nm in average diameter and the surface area 348.3 m2/gCu. Even after a long time (110 h) catalyzing the reaction of ethanol dehydrogenation to acetaldehyde at 523 K, the Cu@S-1 still possessed a high dispersion degree of Cu (50.0 %), high surface area of Cu (338.8 m2/gCu) and small average diameter of Cu particles (2.0 nm). Feng et al. 69 also encapsulated Cu inside S-1 crystals in HT method but using EDA as organic ligand and CuCl2 as the source of Cu. For their Cu@S-1 samples respectively containing 0.53 and 0.95 wt% of Cu after a calcination at 550 °C for 6 h, both of them showed the average Cu nanoparticles size around 2 nm. These samples displayed high thermal stability, even after a treating at 600 °C in H2 as well as at 700 °C in Ar (the treating time is not given by the authors), the nanoparticles of Cu could maintain the average size (2 nm), as shown in Figure 6.

Methanol conversion and selectivity to H2/CO/CO2 for methanol steam reforming over xCu@S-1 catalysts at 300 °C (A), SEM of the 1.0Cu@S-1 (B) and Cu statistical particle size in the 1.0 Cu@S-1(insert). Copyright 2023 Royal Society of Chemistry.

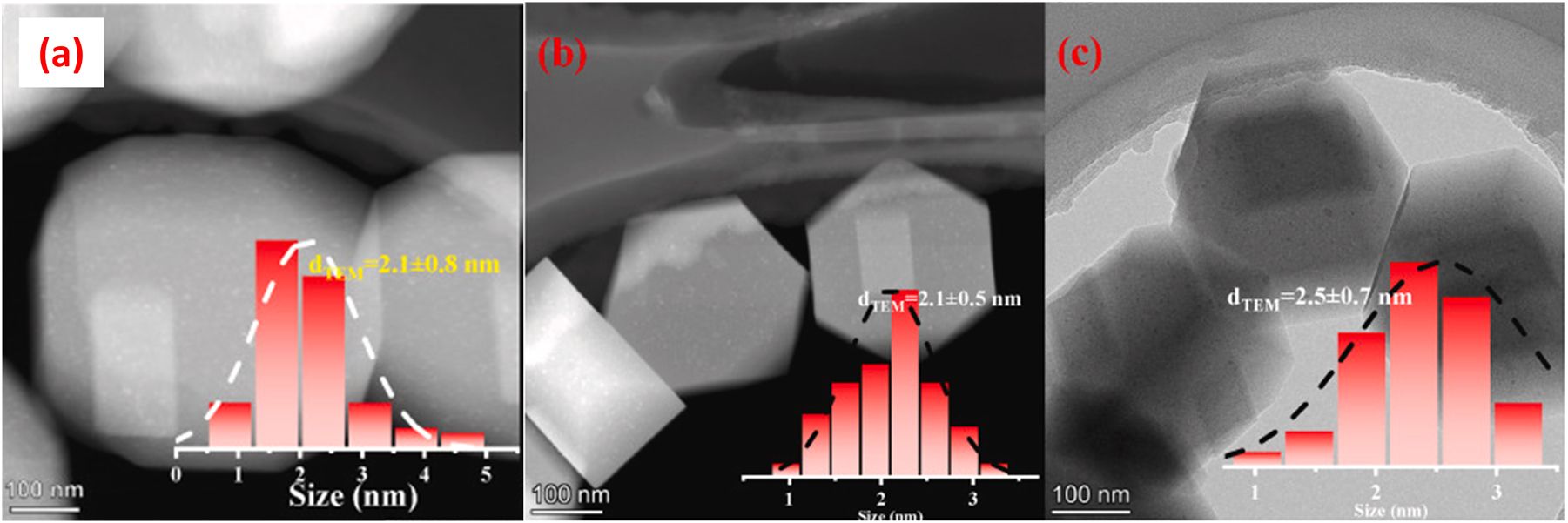

TEM images of the reduced 1 wt%Cu@S-1 (A), the 1 wt%Cu@S-1 calcined at 700 °C in Ar (B), and the 1 wt%Cu@S-1 after reduction by H2 at 600 °C (C). Copyright 2023 Elsevier.

Xie et al. 70 encapsulated Zn into S-1 zeolite crystals with nominal weight percentage (x) 2, 3, 4, 6, and 8 in HT method using Zn(OAc)2 as the source of Zn and EDA as organic ligand. Like that of Fe@S-1 64 and Ni@S-1 65 mentioned above, the crystal size of xZn@S-1 increased from ca. 400 nm–1,200 nm with the Zn loading increase. Herein, it should be particularly noted that Zhang et al. 43 succeed the Zn incorporation to S-1 zeolite without using organic ligands, by using Zn/SiO2 as the source of both silicon and zinc that is prepared by loading Zn on SiO2 support using an incipient wetness impregnation method, which is different from the metal incorporation being realized in the assistance of organic ligand.

2.3 Simultaneous encapsulation of noble and non-noble metals

In some cases, to regulate steric and electronic property of the noble metal that is encapsulated within the zeolite crystals, it is necessary to encapsulate non-noble metals together with a desired noble metal into the zeolite substrates. This section summarizes the corresponding investigation results, as shown in Table 3.

Summary of the encapsulating bimetal (M-fluorine-containing N) in zeolite crystals.

| M-N | Method | Starting gels | Post treatment | AMa (nm) |

MHb (nm) |

CMc | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pt–Sn | Fluorine-containing system | 1.0 TEOS: 0.4 TPAOH: 15 H2O, SnCl2, H2PtCl6, EDA, HF, crystallization at 170 °C for 24 h. | Reduced by H2 at 600 °C for 1 h | 2.5 | 4,000 | PtSn2 (IMC)d | Zhu et al. |

| Pt–Zn | HT, using EDA as ligand | TEOS: TPAOH: H2O: a[Pt(EDA)2]Cl2:b[Zn(EDA)3](OAc)2 = 1: 0.4: 35: a: b (a = 2.25 × 10−3, a/b = 1/1, 1/2, 1/3, 1/4, and 1/8), crystallization at 170 °C for 72 h | Calcined at different T and reduced at 400 °C for 2 h in H2 | 0.83 | 150 | PtZn4 (IMC) | Sun et al. |

| 1.0 SiO2:0.4 TPAOH:35 H2O:0.00225 [Pt(EDA)2]Cl2:0.011 [Zn(EDA)3](NO3)2 crystallization at 170 °C for 96 h | Calcined at 550 °C for 8 h | 6.1 | 450 | Pt3Zn5 (IMC) | Wang et al. | ||

| TEOS:TPAOH:H2O: n[Pt(EDA)2]Cl2:[Zn(EDA)3]·(OAc)2 = 1:0.4:35:n:1.8 × 10−2 (n = 1.12, 2.25, 4.50 and 6.75 × 10−5) crystallization at 170 °C for 48 h. |

Reduced by H2 at 550 °C for 2 h | 2.11 | 200 | Pt0.0219Zn2 (IMC) | Qu et al. | ||

| (Pt + Zn)/SiO2 for HT | [Zn(OAc)2 + Pt(NH3)2(NO2)2]/SiO2 +TPAOH + H2O, crystallization at 180 °C for 4 h. | Calcined at 550 °C for 6 h | 3.9 | 450 | PtZn0.7 (IMC) | Zhang et al. | |

| Pt–Cu | HT, using EDA and DETA as ligand | TEOS:TPAOH:H2O:[Pt(EDA)2Cl2]:Cu-DETAe:KCl = 1:0.4:35:3.2 × 10−4:0.0147:0.02, crystallization at 170 °C for 72 h. | Calcined at 550 °C for 6 h | 1.5 | 428 | PtCu4 (IMC) | Zhou et al. |

| Pt–In | HT, using EDA and EDTAf as ligand | TEOS:TPAOH:H2O:[Pt(EDA)2Cl2]:In-EDTA:KCl = 1:0.4:35:1.6 × 10−3:2.6 × 10−3:0.02, crystallization at 170 °C for 72 h. | Calcined at 550 °C for 6 h | 1.25 | 270 | PtIn (IMC) | Zhou et al. |

| Pt–Ga | HT, using EDA as ligand | TEOS: TPAOH: H2O: [Ga(EDA)3](NO3)3: [Pt(EDA)2Cl2] = 1: 1.4: 10.5: 0.41: 0.025, crystallization at 170 °C for 72 h. | Reduced by H2 at 600 °C | 5.45 | 933 | PtGa (IMC) | Wang et al. |

| Pd–Mn | HT, using EDA and TEPAg as ligand | 1.0 SiO2: 0.4 TPAOH: 35 H2O: 0.0045 [Pd(EDA)2]Cl2: x[Mn(TEPA]Cl2 (x = 0.0009, 0.0018, 0.0027, 0.0036), crystallization at 170 °C for 72 h. | Calcined at 550 °C for 6 h and then red at 400 °C | 1.8 | 250 | PdMn (IMC) | Sun et al. |

| Rh–In | HT, using EDA as ligand | TEOS: TPAOH: H2O = 1.0: 0.4: 35, H2PtCl6, In(NO3)3 crystallization at 170 °C for 96 h. | Calcined at 550 °C for 2 h | 1.25 | 400 | RhIn (IMC) | Zeng et al. |

-

aAverage size of metal particles; bmorphology of the hybrids; cintermetallic compound; dintermetallic compound; eN-[3-(trimethoxysilyl) propyl] ethylenediamine (DETA); fethylenediaminetetraacetic sodium (EDTA); gtetraethylenepentamine (TEPA). ethylenediamine (DETA);f Ethylenediaminetetraacetic sodium (EDTA); gTetraethylenepentamine (TEPA).

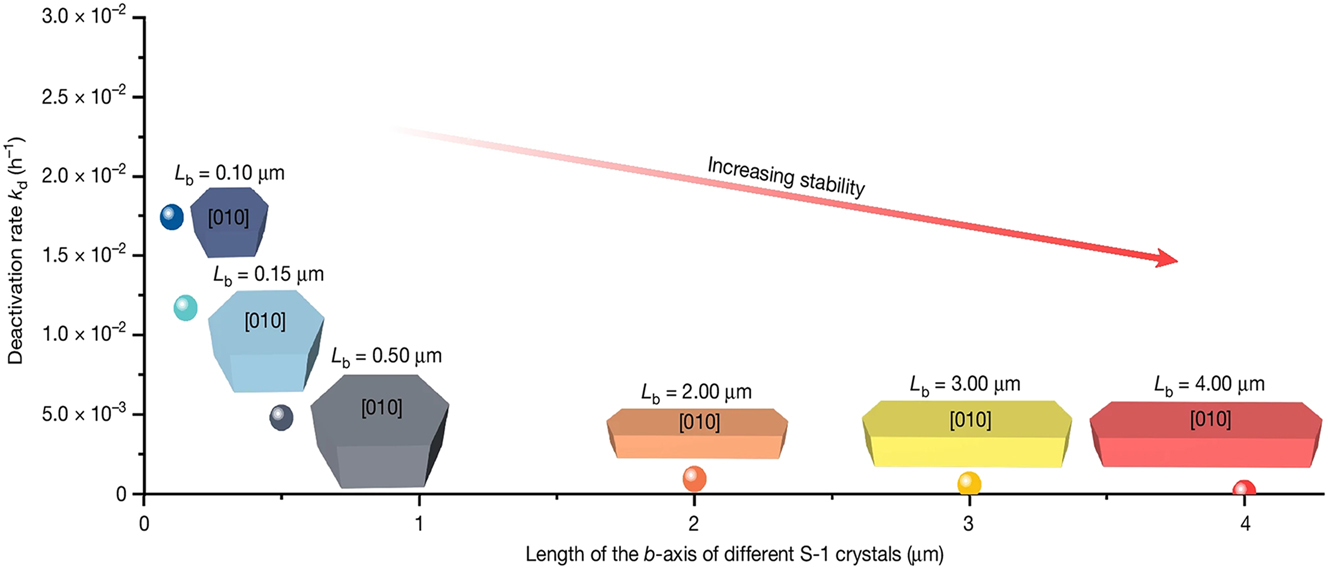

Xu et al. 71 synthesized PtSn@S-1 hybrids in fluorine-containing system (F/Si = 0.00–0.51) but also using EDA as organic ligand. They found that the length of the PtSn@S-1 hybrid crystals along b axis (Lb) could be tuned in the range of 0.10–4.00 μm by regulating the F− concentration of the starting gel, and that the deactivation constant (kd) of the Pt–Sn@S-1 catalyzing propane dehydrogenation significantly decreased with the Lb increasing, as shown in Figure 7.

Dependence of deactivation rate on the morphology for the PtSn@S-1 catalyzing propane dehydrogenation to propylene. Copyright 2022 Research Square.

Sun et al. 16 synthesized PtZnx@S-1 hybrids containing 0.72–0.77 wt% of Pt from the gels with Zn/Pt mole ratio (x = 0, 1, 2, 3, 4), and characterized the hybrids in SEM, TEM and STEM after reduction by H2 at 400 °C. Their results indicated that with the Zn/Pt ratio increasing from 0 to 4, the crystal size of the hybrids decreased from ∼200 nm to 160 nm, and all of the metal nanoclusters were uniformly encapsulated in the S-1 crystals, locating at the intersectional position of the straight channels and sinusoidal 10-ring channels of the zeolite. The authors found that the metal clusters in the PtZnx@S-1 hybrids are much sensitive to the calcination temperature of the sample. When the calcination temperature increasing from 300 to 500 °C, the average size of metal clusters in the resultant materials increased from 1.4 to 2.7 nm. Compared the other PtZnx@S-1 hybrids synthesized by themselves, the PtZn4@S-1 as catalyst is more active and stable for catalyzing propane dehydrogenation. As the zinc content increases, more bimetallic Pt–Zn alloys are formed, but the excessive Zn may partially cover the active Pt surface, resulting in a negative effect on the activity of catalyst. Wang et al. 72 have synthesized a series of xPtyZn@S-1 hybrids with nominal Pt content x and nominal Ni content y. Their ICP-OES measurement indicated that a rather large portion of metals lost to the mother liquid in the synthesis (Table 4). Qu et al. 73 have also synthesized the xPtyZn@S-1 hybrids from gels with much lower Pt and Zn content (x = 0.0036, 0.0072, 0.0146, 0.0219 wt%, y = 2 wt%). They found that the presence of Zn in the gels is helpful for the Pt dispersion within the resultant hybrid crystals. For instance, the mean size of metal nanoparticles for the 0.0219 wt%Pt@S-1 sample is 3 nm while the metal in the 0.0219 wt%Pt0.2Zn@S-1 sample are homogenously dispersed without any agglomeration. The low amount of Pt can significantly promote the activity of PtZn@S-1 catalyst in propane dehydrogenation (PDH) reactions. Zhang et al. 43 also encapsulated Pt with Zn into S-1 zeolite crystals in the synthesis but from a supporting type of material (Pt + Zn)/SiO2 without adding organic ligand, like the synthesis of xZn@S-1 from Zn/S-1, which was mentioned in the section of 2.2. The authors have pointed that Zn is beneficial to Pt dispersion in the 1PtxZn@S-1 (x = 0.3, 0.7, 1.2) hybrids. For the reaction of ethane dehydrogenation, the 1Pt0.7Zn@S-1 catalyst is more active and stable than the other two hybrids.

Metal loading amounts measured by ICP-OES for the xPtyZn@S-1.

| Samples | Pt loading (wt%) | Zn loading (wt%) |

|---|---|---|

| 0.05Pt0.5Zn@S-1 | 0.02 | 0.42 |

| 0.1Pt0.5Zn@S-1 | 0.06 | 0.43 |

| 0.15Pt0.5Zn@S-1 | 0.10 | 0.42 |

| 0.2Pt0.5Zn@S-1 | 0.14 | 0.44 |

| 0.25Pt0.5Zn@S-1 | 0.20 | 0.46 |

| 0.3Pt0.5Zn@S-1 | 0.23 | 0.42 |

| 0.35Pt0Zn@S-1 | 0.28 | 0 |

| 0.3Pt0.1Zn@S-1 | 0.21 | 0.05 |

| 0.3Pt0.3Zn@S-1 | 0.23 | 0.22 |

| 0.3Pt0.5Zn@S-1 | 0.22 | 0.42 |

| 0.3Pt0.7Zn@S-1 | 0.25 | 0.61 |

| 0.3Pt1Zn@S-1 | 0.26 | 0.83 |

| 0.3Pt1.3Zn@S-1 | 0.26 | 1.11 |

| 0.3Pt1.5Zn@S-1 | 0.23 | 1.32 |

Using N-[3-(trimethoxysilyl) propyl] ethylenediamine (DETA) as organic ligand protecting Cu and EDA protecting Pt, Zhou et al. 57 synthesized a series of 0.1PtxCuK@S-1 (x = 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, 0.5) catalysts, where x represents nominal weight percentage of Cu. The authors found that the Pt–Cu alloy species in the 0.1Pt0.4CuK@S-1 catalyst sample has an average size 1.2 nm and this sample is more active than the other 0.1PtxCuK@S-1 sample for catalyzing PDH at 550 °C. The authors also synthesized a series of 0.5PtxInK@S-1 (x = 0.1, 0.3, 0.5, 1.0) using EDTA as organic ligand protecting In, where x represents the nominal weight percentage of In. 74 They found that K significantly promotes the dispersion of Pt and In within the S-1 zeolite crystals, which is like the case of single metal Pt incorporate to S-1 zeolite, 62 mentioned in Section 2.1. For the 0.5Pt0.5InK@S-1 catalyst, the average size of Pt–In alloy species is 1.4 nm while that in 0.5Pt0.5In@S-1 is 4.0 nm.

Wang et al. 75 synthesized a series of 0.1PtxGa@S-1 (x = 0, 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 2.5, 3) and yPt1.5Ga@S-1 (y = 0.02, 0.04, 0.06, 0.08, 0.10) using EDA as organic ligand, where x and y represent the nominal weight percentage of Ga and Pt, respectively. They found that the Ga–Pt alloy species in the 0.1Pt1.5Ga@S-1 has an average size 2.6 nm and this sample has the best catalytic property for the PDH among the above hybrid samples.

Sun et al. 63 encapsulated Pd–Mn alloy species within S-1 zeolite crystals using EDA and TEPA as organic ligand protecting Pd and Mn, respectively. Among their synthesized series of PdMn x @S-1 (x = 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, and 0.8), where the x represents Pd/Mn mole ratio of the gel, the PdMn0.6@S-1 displayed the highest formate formation rate in the CO2 hydrogenation. They found that the PdMn0.6@S-1 sample possess remarkably thermal stability. After thermal treatments in various atmospheres (calcination in N2 at 700 °C, calcination in H2 at 700 °C, or five oxidation-reduction treatments at 650 °C), the morphology and crystallinity of PdMn0.6@S-1 remained intact.

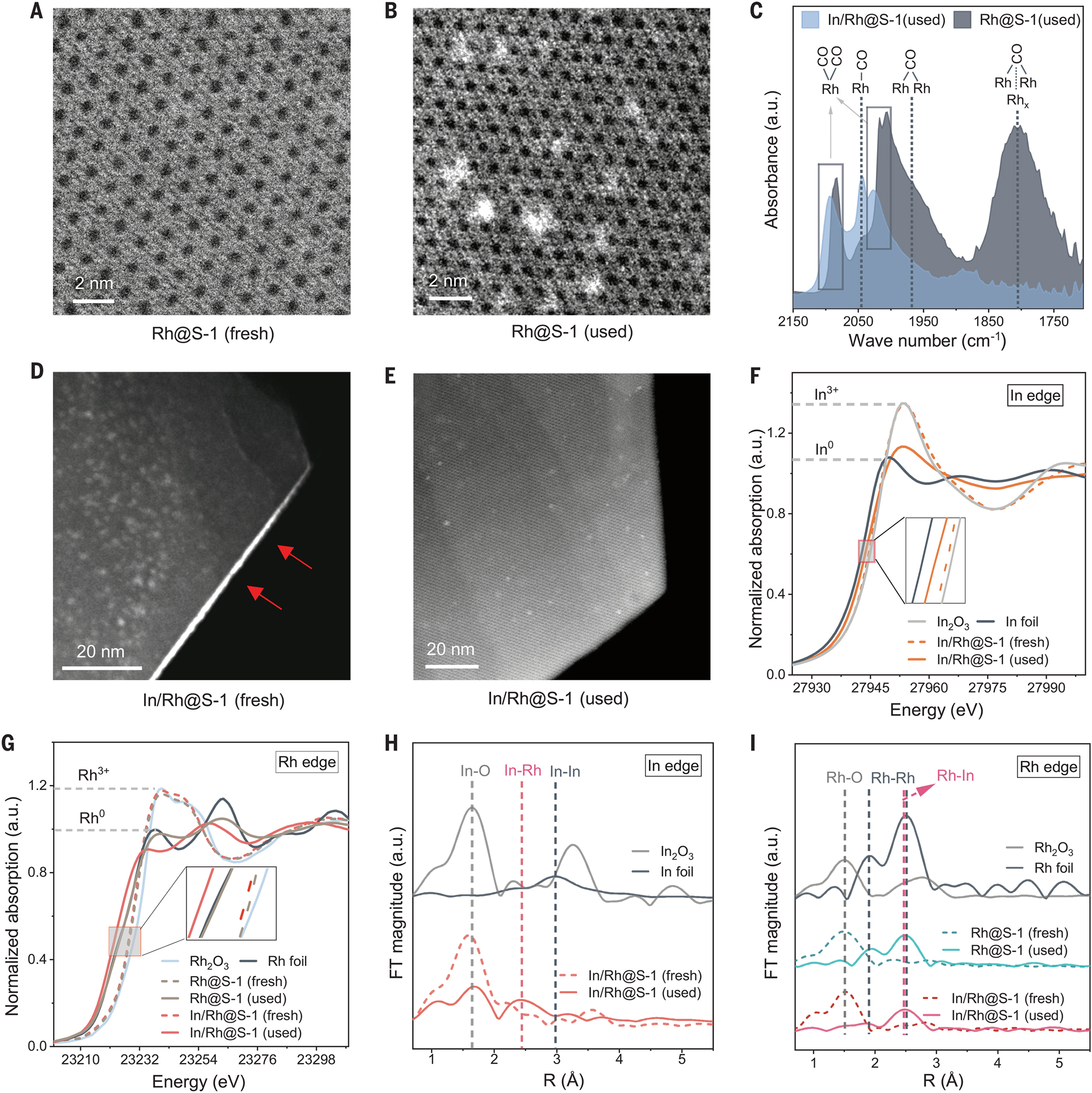

Zeng et al. 58 obtained a series of RhM@S-1 catalysts (M = In, Sn, Zn, Ga, and Cu) with nominal metal contents of 2.0 wt% for In and Sn, 1.0 wt% for Zn, Ga and Cu, using EDA as organic ligand protecting Rh in one pot synthesis. It is remarkable that, the RhIn@S-1 displayed outstanding catalytic activity for PDH. Herein, it is worthy to note that the In–Rh@S-1 catalyst being prepared by calcining a physical mixture of 0.03 g In2O3 with 0.97 g Rh@S-1 is more active and stabile than the RhIn@S-1 for catalyzing the PDH reaction.

3 The synthesis of zeolites with heteroatoms

Synthesizing of zeolites with Zn, Sn, or Co heteroatoms is one way of incorporating the metals to the zeolite. Undoubtedly, this way can be considered as the optimal ideal technique for dispersing and encapsulating the metal within the zeolite crystals as it would make the dispersion to single atomic level. Herein, we specially summarize the syntheses of zeolites with the metal heteroatoms, as shown in Table 5.

Syntheses of zeolites with non-noble metal as heteroatom.

| Hetero-atom | Synthesis method | Synthesis conditions | Post treatment | Crystal size (nm) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zn-MFI | HT | TEOS, TPAOH and water was stirred together at 60 °C for 2 h, after zinc gluconate addition, the mixture was crystalized at 170 °C for 72 h. | Calcined at 550 °C for 4 h | 180 | Su et al. |

| HT, using PDDA as porous’ template | Fumed silica, TPAOH were ground together, and then zinc acetate, S-1 (as seed), PDDA and water were successively added and ground. The mixture was statically crystalized at 180 °C for 72 h. | Calcined at 550 °C for 6 h | 1750 | Yuan et al. | |

| TPAOH, water, and TEOS stirred together at room temperature for 2 h, after PDDA, Zn(NO3)2 addition, the resultant mixture was statically crystalized at 170 °C for 72 h. | Calcined at 550 °C for 4 h | 150 | Lu et al. | ||

| Sn-MFI | HT | TEOS, TPAOH and water was stirred together at 80 °C for 2 h, after SnCl4 addition, the mixture was crystalized at 170 °C for 72 h. | Calcined at 550 °C for 6 h | –a | Liu et al. |

| SnCl4 dissolved in TPAOH was added to TEOS and stirred for 30 min, the water was added and further stirred for 24 h. The mixture was statically crystalized at 170 °C for 48 h. | Calcined at 550 °C for 12 h | 250 | Li et al. | ||

| SGP | TEOS was added to TPAOH aqueous solution and stirred for 6 h, [Sn(EDA)2]Cl2 added and stirred for 30 min, after evaporated at 70 °C, the concentrated mixture was statically crystallized at 240 °C for 2 h. | Calcined at 550 °C for 4 h | 300 | Wang et al. | |

| Co-MFI | HT | 1SiO2: nCoO: 2nEDA: 0.3TPAOH: 4IPA: 35H2O (0 < n < 0.03), statically crystallization at 170 °C for 72 h. | Calcined at 550 °C for 4 h | – | Hu et al. |

-

aNo message about the crystal size.

3.1 The synthesis of ZnS-1 zeolite

Su et al. 76 synthesized ZnS-1 zeolite with Zn atoms incorporation into S-1 zeolite framework, using zinc gluconate as zinc source without assistance of organic ligand for the first time. They have characterized the ZnS-1 zeolite samples containing 2.0 wt% Zn in the UV–vis spectroscopy, and found that all of Zn in the ZnS-1 zeolite synthesized using zinc gluconate are incorporated to zeolite framework structure, while that using Zn(OAc)2 or Zn(NO)3 as the zinc source exists as ZnO clusters or nanoparticles in some portion. The authors explained that the glucosyl groups are beneficial to the zinc incorporation into the MFI zeolite framework. The synthesized ZnS-1 zeolite possess good crystallinity and homogeneous isolated Zn sites in the MFI zeolite framework, which exhibit excellent catalytic performance for PDH.

Yuan et al. 77 have also synthesized the ZnS-1 zeolite containing 2.0–4.0 wt% Zn using Zn(OAc)2 as zinc source, but using fumed silica as silicon source in the assistance of poly(diallyldimethylammonium chloride) (PDDA). This organic ligand is proposed to be helpful for Zn2+ incorporation into MFI framework. A possible reason is that the cationic PDDA could rapidly adsorbed on negatively charged silica species via electrostatic interactions, whereby enriching silica species, Zn2+, and organic structure directing ligands (OSDAs), which are required to the synthesis. 78 Lu et al. 79 have also applied PDDA to synthesize the Zn-MFI, but the aim of them using this agent is producing mesopores in the zeolite crystals. The synthesized ZnS-1 can serve as a support for encapsulating or supporting noble metals (Rh, Pt) for catalyzing the dehydrogenation of propane.

3.2 The synthesis of SnS-1 zeolite

Liu et al. 80 synthesized SnS-1 zeolites from the gels with mole ratio of SiO2: SnO2: TPAOH: H2O = 1: (0.005/0.010/0.015): 0.2: 15 using TEOS as silicon source and SnCl4 as tin source. They found that the SnS-1 zeolite with a nominal Sn/Si ratio of 0.015 is more active and selective for the reactions of dihydroxyacetone dehydration to methyl lactate than the other SnS-1 zeolites. The high tetrahedral framework Sn amount is beneficial to improve the selectivity of the reaction.

Li et al. 81 synthesized SnS-1 with nominal Si/Sn mole ratio of 117, 195 and 282 using TEOS and SnCl4 as sources of Si or Sn. The authors confirmed the Sn incorporation to the zeolite framework by XRD, in which the diffraction peaks of the SnS-1 zeolites in the range of 7.4°–9.4° shifted to lower 2θ degree with respect to that of S-1 zeolite. 82 For the SnS-1 zeolites crystallized at 170 °C for 48 h measured by XRD, their crystallinity declined with the Si/Sn mole ratio decrease, whereas no diffraction peaks being assigned to SnO2 appeared.

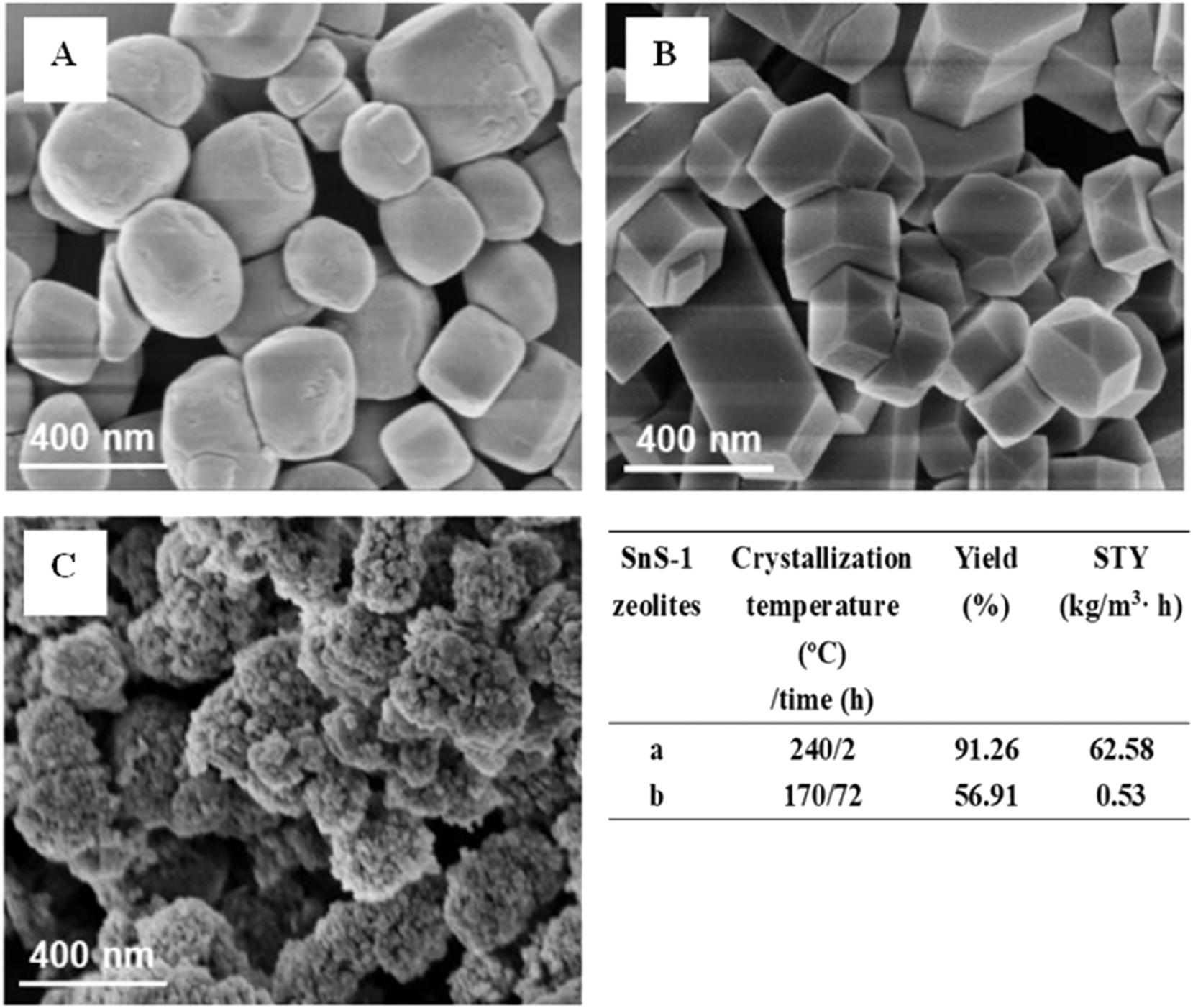

Wang et al. 83 synthesized SnS-1 zeolites with Si/Sn ratio 80, 100 and 175 in typical SGP method (refer to Section 2.1). They found that the zeolite synthesized in the presence of EDA exists as spherical crystals (200–300 nm) (Figure 8A), while that without EDA addition to the gel presents as disordered nanoscale crystals (Figure 8C) and that synthesized in HT method presents as regular crystals exposing more 101 and 200 facets (Figure 8B). On the other hand, it is remarkable, as pointed by the authors, that much higher zeolite yield and space-time yield could be achieved for the zeolite synthesis in the typical SGP condition compared to that in typical HT condition (the insert table in Figure 8).

SEM images (A–C), yield and space-time yield (table) of the SnS-1 zeolites synthesized in different conditions: (A) typical SGP condition; (B) typical HT condition; (C) SGP condition but without EDA addition. Copyright 2022 Wiley Online Library.

3.3 The synthesis of CoS-1 zeolite

Hu et al. 84 synthesized Co x S-1 zeolites (x = 0.32, 0.53, 1.12, and 2.17 wt%) from the gels with mole ratio of SiO2: nCoO: 2nETD: 0.3TPAOH: 4IPA: 35H2O (n = 0.03, 0.05, 1.0, 2.0, and 3.0). The authors did not give the relations of Co content (x) of the zeolite products with Si/Co mole ratio of the gels. Nevertheless, it can be inferred that the Co content of the Co x S-1 zeolite is much less than that of the corresponding dry gels, indicating that Co is hardly incorporated to zeolite, and most of the Co remains in the liquid phase after the crystallization. For Co1.12S-1 zeolite sample synthesized by the authors, it is confirmed by EXAFS and UV–vis that the Co is dispersed to single Co species in the zeolite crystals, and incorporated to the zeolite framework, as it delivers absorption at 529, 582 and 653 nm. 85 , 86 , 87

4 Characterization of heteroatoms in zeolites and controlling synthesis of the metal-zeolite hybrid for application

Getting information between the synthesis parameter and the catalytic product structure is of great significance for understanding the mechanism of product structure formation. On this basis, the researchers would be able to reasonably control the synthesis to obtain their product with desired structure. Concurrently, getting an information between the structure and the property of the product is also greatly significant for understanding the reaction mechanism so as to promote the rational design of high-performance catalysts toward industrial applications. Obviously, knowing the product structure via appropriate characterization is indispensable. Hence, in this section, we will make our great efforts to summarize the characterization of heteroatoms in zeolites reported in the literature and the effective strategies proposed by the authors for controlling the structure of the hybrid (Table 6).

Characterization of the metal-zeolite hybrid and the strategies for control ling the structure of the hybrid.

| Applications of the products as catalysts | Metal-zeolite hybrids | Primary characterization methods | Representative strategies for controlling the structure of the hybrid |

|---|---|---|---|

| Propane dehydrogenation 12 , 16 , 43 , 58 , 66 , 71 , 72 , 73 , 74 , 75 , 76 , 84 , 88 , 90 , 96 , 97 , 98 | PtZn@S-1

16

RhIn@S-1 58 PtSn@S-1 71 PtIn@S-1 74 PtGa@S-1 75 Co-MFI 84 PtLa@ZnBeta 97 |

UV-vis

12

SSNMR 43 CO-FTIR 58 EXAFS 58 , 84 XPS 74 , 97 , 98 EDX mapping 76 , 96 , 98 Cs-STEM 84 |

Stabilizing single Rh atoms inside S-1 by harnessing In to anchor them. 58 |

| Dry reforming of methane 19 , 65 , 99 | Ni@S-1 19 , 65 , 99 | UV-vis

19

EXAFS 19 HAADF-STEM 19 EDX mapping 65 XPS 99 FTIR 99 |

Utilizing Ni2+/S-1 as precursor in the one-pot synthesis of Ni@S-1. 19 |

| Regioselective hydroformylation 95 | Rh-MFI | EXAFS CO-FTIR HAADF-STEM XPS |

Confining Rh clusters inside S-1 crystals, using the zeolites tunnels to inhibit by-product formation. 95 |

4.1 Framework heteroatoms of zeolites

For some reactions, such as dry reforming of methane, 65 methanol steam reforming, 67 oxidative dehydrogenation of propane with carbon dioxide, 77 propane dehydrogenation, 70 , 88 , 89 NH3-SCR, 90 synthesis of thieno [2,3-d] pyrimidinones, 91 direct oxidation of methane, 92 Knoevenagel condensation of benzaldehyde with ethyl cyanoacetate, 93 conversion of cellulosic sugars into methyl lactate, 94 framework heteroatoms of zeolites were found to play a significant role in the catalytic processes. Therefore, clearly characterizing the amount and the dispersion of framework heteroatoms in the zeolite crystals have much important meaning for the investigation. In some cases, although the active sites catalyzing the reaction actually lie on the metal 95 or metal alloy states, 16 , 58 , 66 , 71 , 72 , 73 , 74 , 75 since the zeolites with framework heteroatoms act as predecessors of the catalysts, these parameters may primarily determine the catalytic structure. Hence, no matter which cases mentioned above, the significance of knowing information about the framework heteroatoms in the zeolites needless to say.

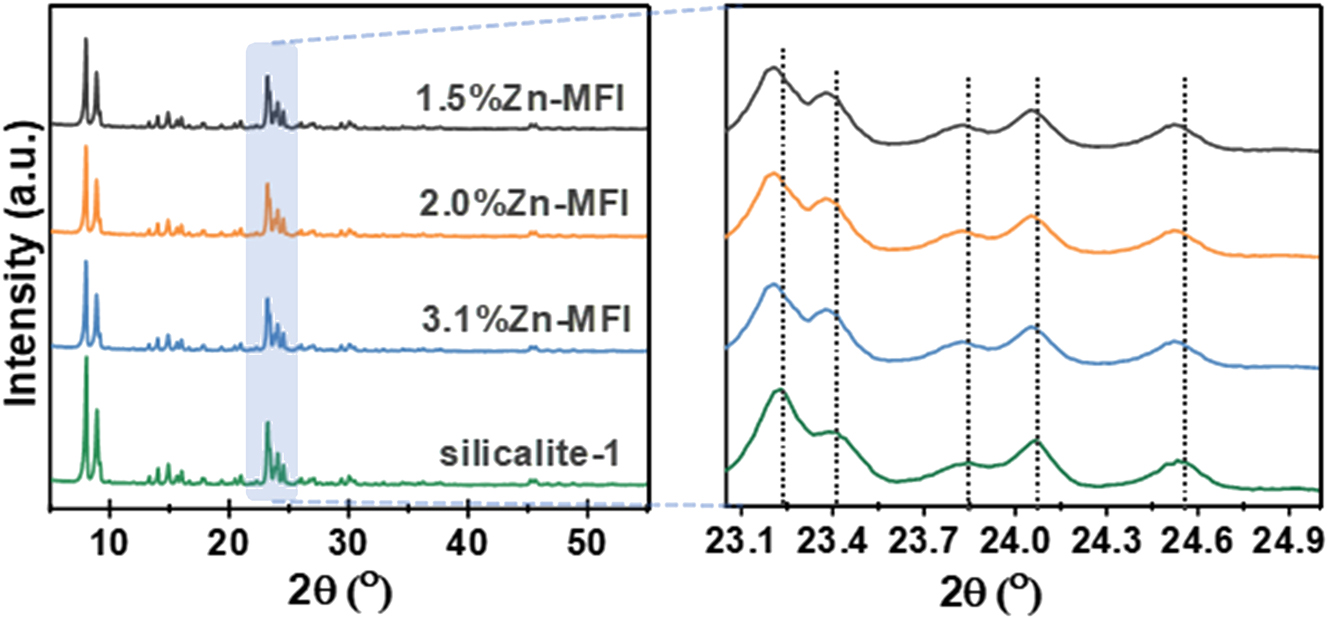

To get the information, XRD of the heteroatoms’ zeolites was favorite to be applied, 76 , 96 , 97 , 98 as the radius of the Si(IV) in the zeolite framework being replaced by the transition metal cations (Mn2+, Fe3+, Co2+, Co3+, Ni2+, Cu2+, Zn2+, Sn2+) is essentially less than the latter. For example, Su et al. 76 have proved that Zn2+ incorporated MFI zeolite framework replacing the Si(IV), as shown in Figure 9.

XRD patterns of 1.5%Zn-MFI, 2.0%Zn-MFI, 3.1%Zn-MFI, and silicalite-1. Copyright 2023 Elsevier.

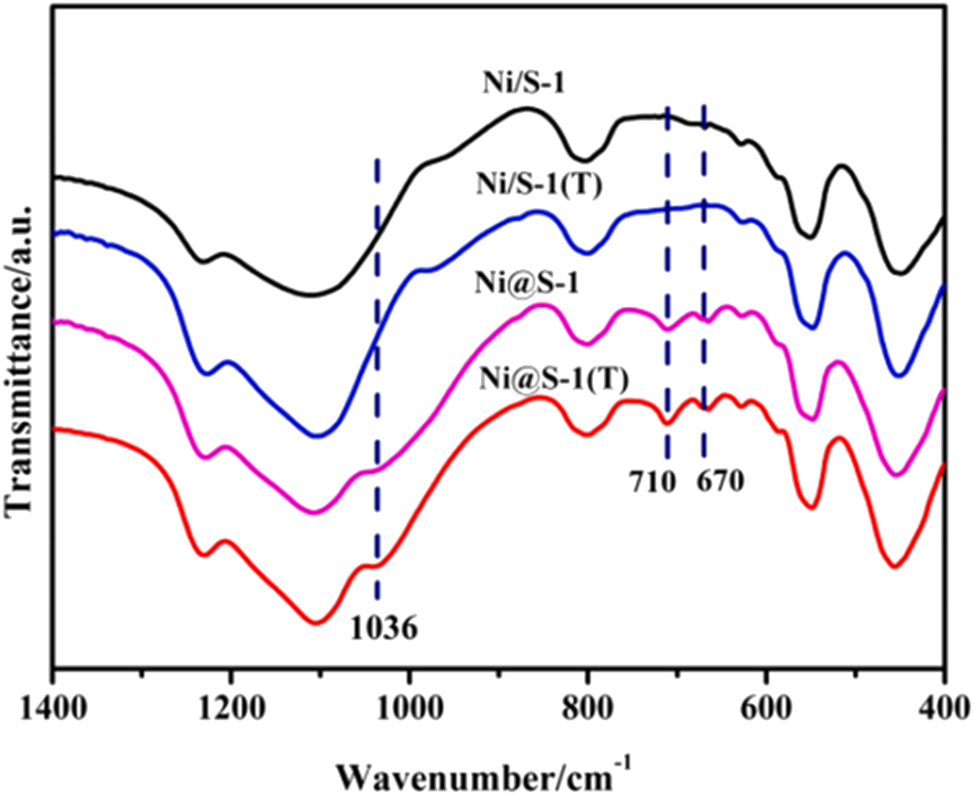

As a convenient characterization method, catalyst-skeleton FTIR was also applied by the researchers to prove heteroatoms (M) incorporating the zeolite framework, since the incorporation must be accompanied by M–Si bond formation that is sensitive to the FTIR. For instance, Han et al. 99 using the appearance of new bands at 1,036, 710, and 670 cm−1 to prove the Ni phyllosilicate formation, as shown in Figure 10.

FTIR spectra of the samples. Copyright 2024 Elsevier.

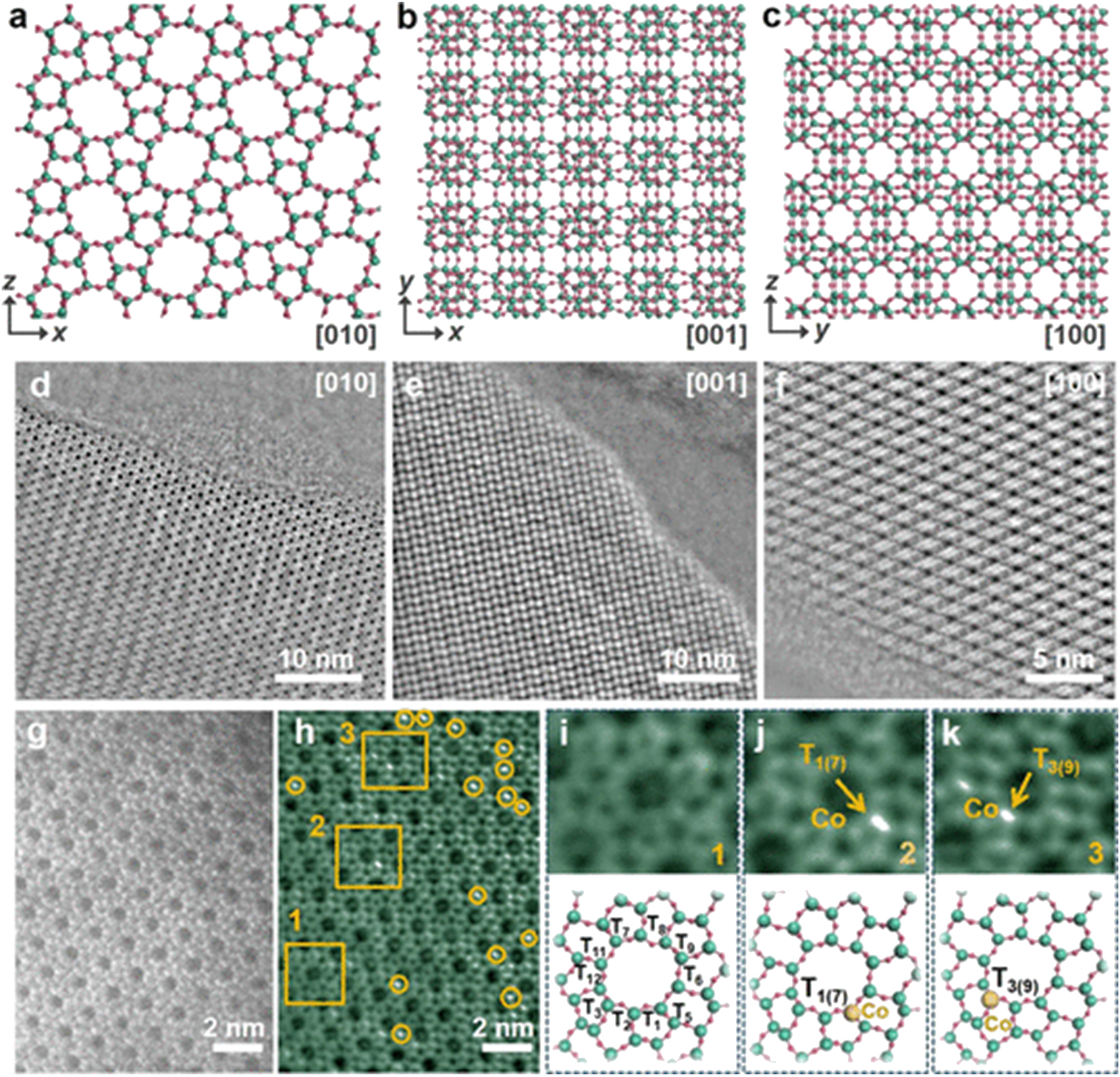

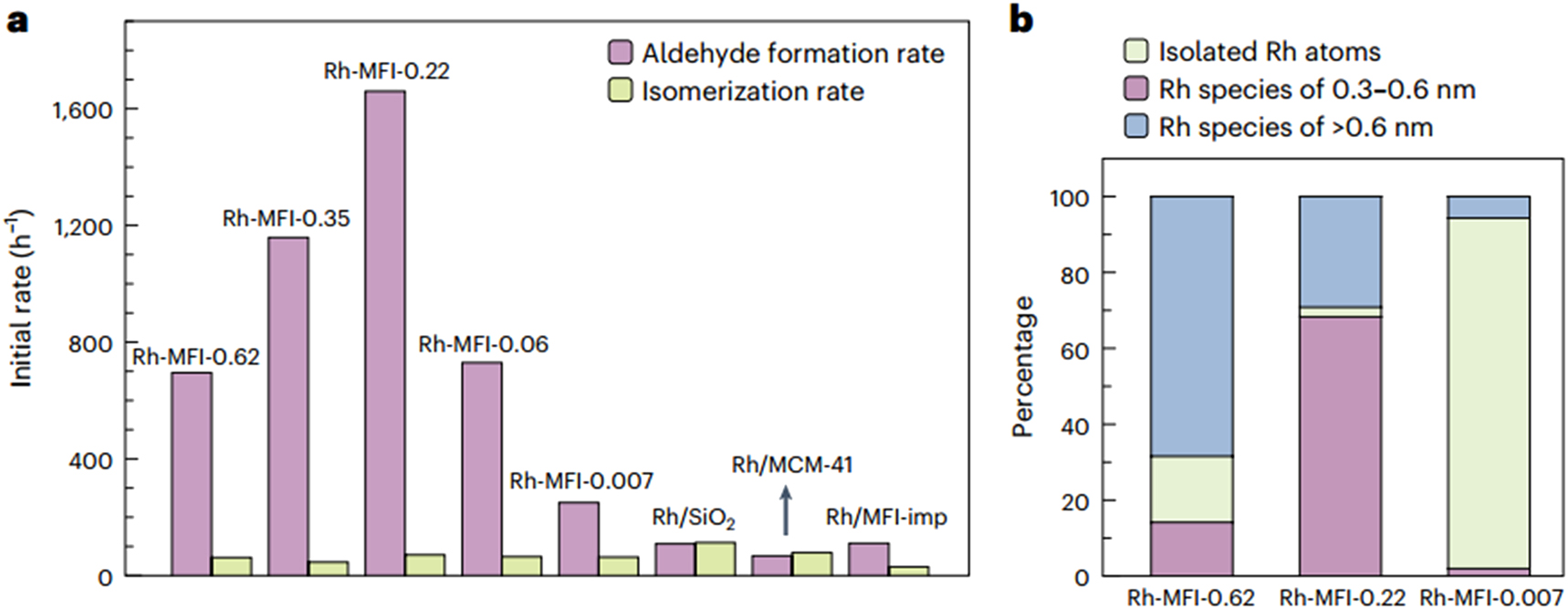

To corroborate heteroatoms’ incorporation into zeolite, Cs-corrected iDPC-STEM of the zeolites is generally required. Hu et al. 84 applied this characterization method evidencing the Co atom incorporation into MFI zeolite (Figure 11), Dou et al. 95 applied this characterization revealing Rh cluster in MFI zeolite (Figure 12).

Electron microscopy analyses of the Co-MFI zeolite with a Co content of 1.12 wt%. (A–C) Structure of the MFI-type framework. (D–F) Cs-corrected iDPC-STEM images of the Co-MFI framework were taken along the three main crystallographic axes. (G) Cs corrected HAADF-STEM image and (H) corresponding iDPC-STEM image of the Co-MFI framework. (K–M) Zoomed-in areas of 1, 2, and 3 in (H), respectively: the MFI framework without Co (I) and the MFI framework containing Co at the T1(7) site (J) and the T3(9) site(k). Copyright 2022 ACS Publications.

![Figure 12:

Structural characterization of Rh-MFI catalysts using the iDPC-STEM imaging technique. A–D, HAADF-STEM images of the Rh-MFI-0.62 (A), Rh-MFI-0.35 (B), Rh-MFI-0.22 (C) and Rh-MFI-0.007 (D) samples. Rh clusters appear as small bright particles in A–C, whereas only a few bright dots ascribed to isolated Rh atoms are observed in D. E–H, Paired HAADF-STEM (E, G) and iDPC-STEM (F, H) images of the Rh-MFI-0.35 sample along the [010] (E, F) and tilted-[010] (G, H) orientations. (I–L) Paired HAADF-STEM and iDPC-STEM images of the Rh-MFI-0.22 sample along the [010] (I, J) and tilted-[010] (K, L) orientations. (M–P), Paired HAADF-STEM and iDPC-STEM images of the Rh-MFI-0.007 sample along the [010] (M, N) and tilted-[010] (O, P) orientations. Copyright 2024 Springer Nature.](/document/doi/10.1515/revic-2024-0132/asset/graphic/j_revic-2024-0132_fig_012.jpg)

Structural characterization of Rh-MFI catalysts using the iDPC-STEM imaging technique. A–D, HAADF-STEM images of the Rh-MFI-0.62 (A), Rh-MFI-0.35 (B), Rh-MFI-0.22 (C) and Rh-MFI-0.007 (D) samples. Rh clusters appear as small bright particles in A–C, whereas only a few bright dots ascribed to isolated Rh atoms are observed in D. E–H, Paired HAADF-STEM (E, G) and iDPC-STEM (F, H) images of the Rh-MFI-0.35 sample along the [010] (E, F) and tilted-[010] (G, H) orientations. (I–L) Paired HAADF-STEM and iDPC-STEM images of the Rh-MFI-0.22 sample along the [010] (I, J) and tilted-[010] (K, L) orientations. (M–P), Paired HAADF-STEM and iDPC-STEM images of the Rh-MFI-0.007 sample along the [010] (M, N) and tilted-[010] (O, P) orientations. Copyright 2024 Springer Nature.

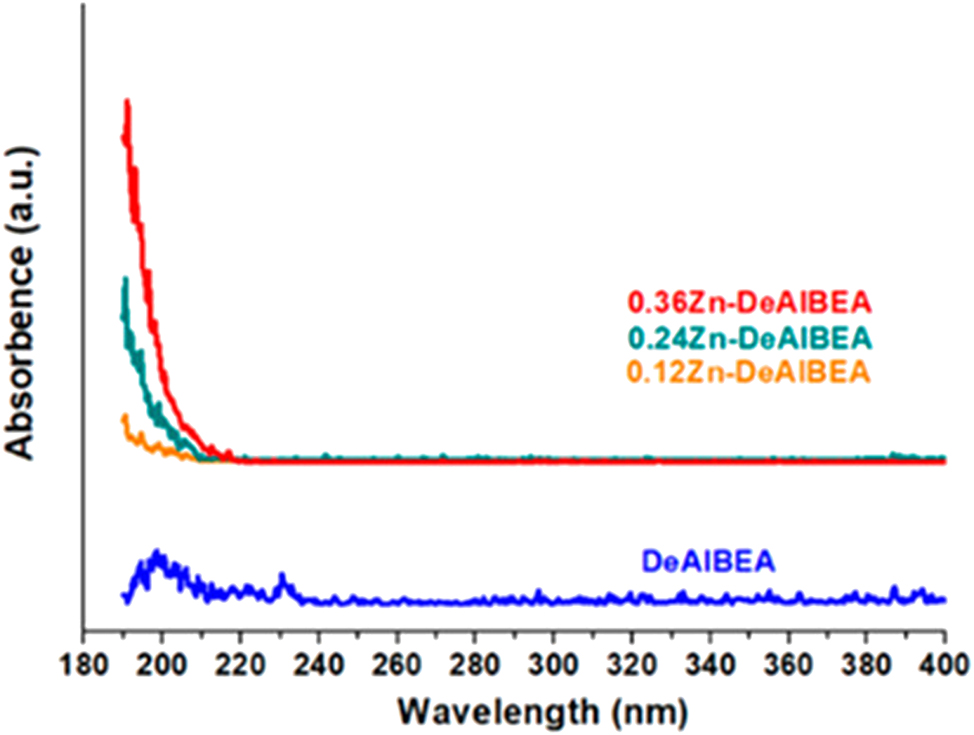

UV–vis has been frequently applied by researchers in literature, with which to simi-quantitatively reveal the heteroatoms being incorporated to zeolites framework, 12 , 96 , 97 , 98 Qi et al. applied this characterization to indicate framework Zn, as shown in Figure 13. 12

UV–vis results characterizing DeAlBEA and Zn-DeAlBEA. Copyright 2021 ACS Publications.

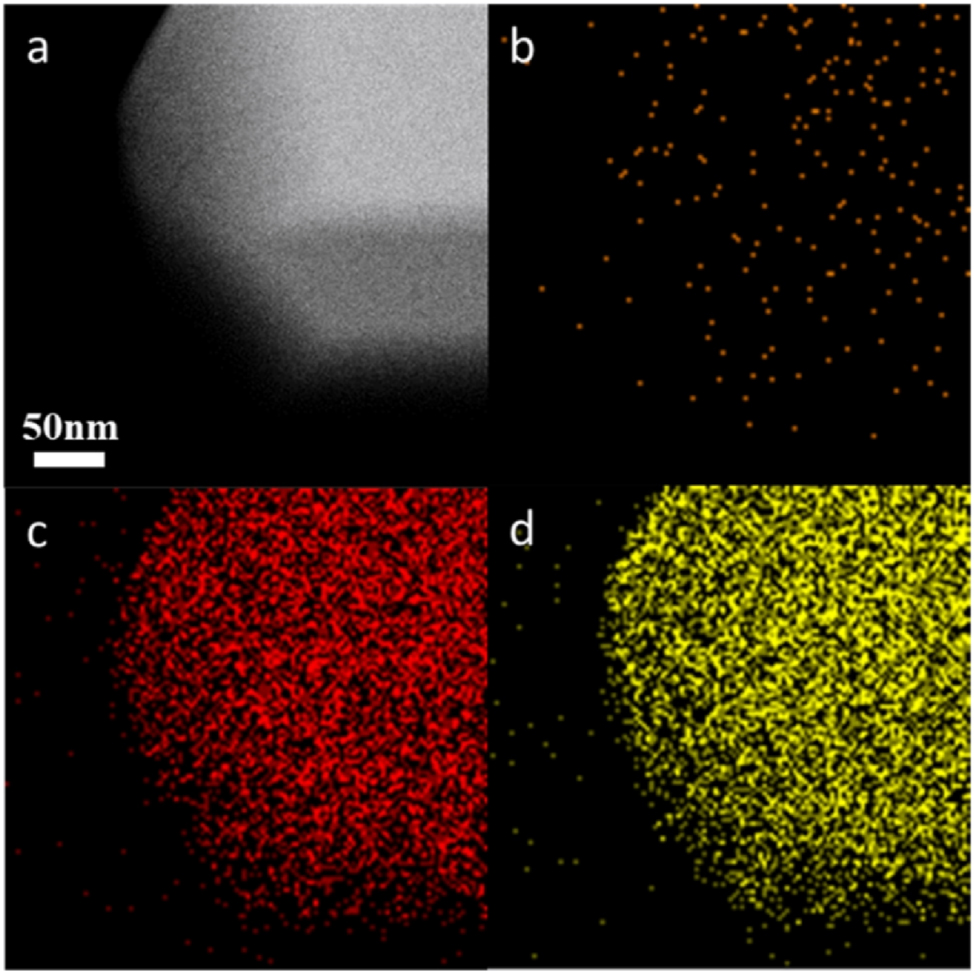

EDX mapping was frequently applied to characterize the heteroatoms dispersion situation in the heteroatom-containing zeolites. 67 , 96 , 97 , 98 For instance, Hong et al. 67 using this technique to prove the uniform distribution of the Cu species in the MFI zeolite crystals, as shown in Figure 14.

(A) HAADF-STEM image of 1.0 Cu@S-1 and corresponding EDX mapping of (B) Cu, (C) O, and (D) Si. Copyright 2023 Royal Society of Chemistry.

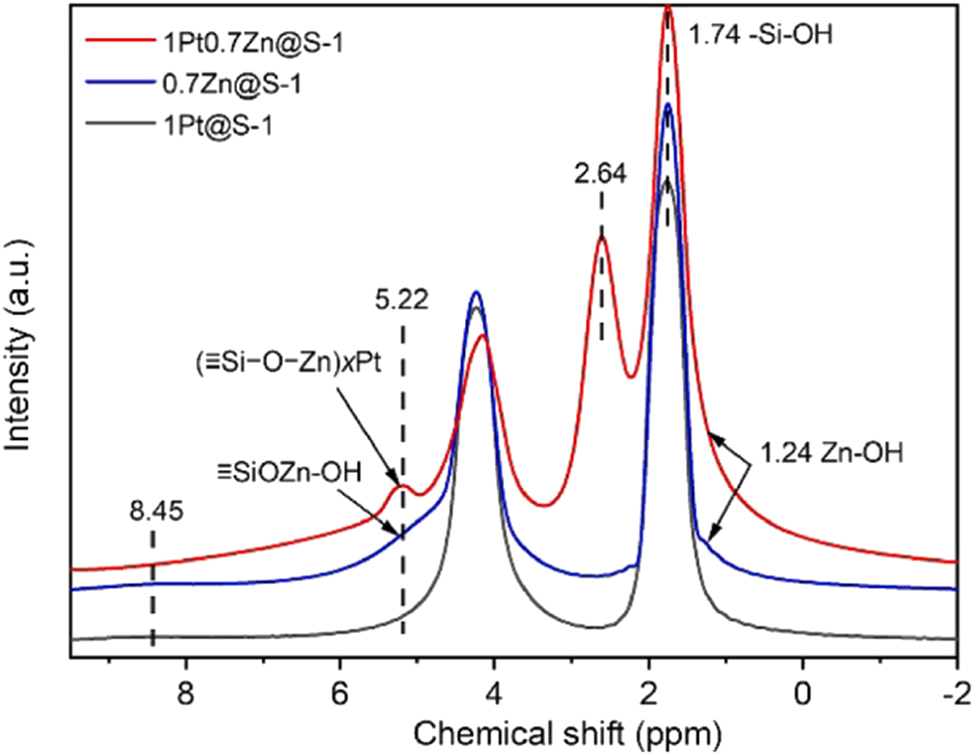

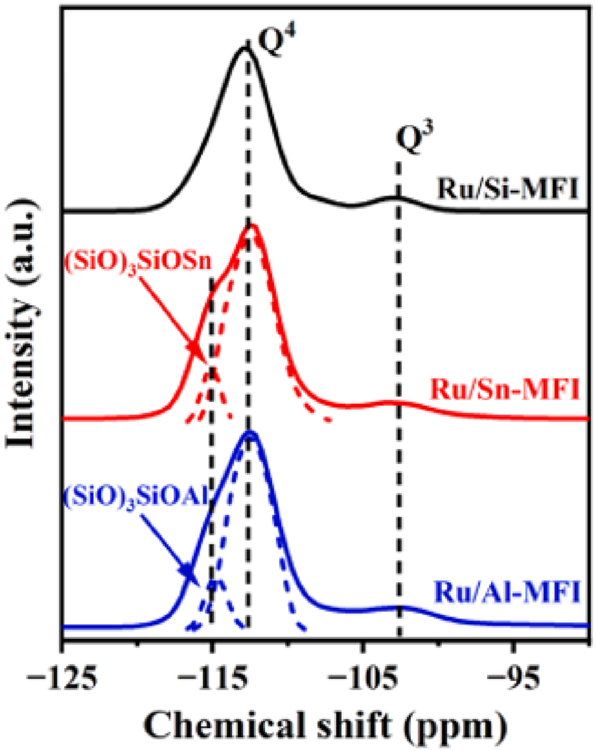

Although MAS NMR is infrequently used due to its high use-cost, it still a useful method for characterizing the framework heteroatoms in the zeolite. For instance, Zhang et al. 43 using 1H MAS NMR revealed the existence of Zn in PtZn@S-1 by means of the detection of ≡SiOZn–OH (Figure 15). Due to the incorporation heteroatoms replacing the Si(IV) in the zeolite crystals often alters the coordination environment of the Si, that is, change the ratio of (SiO)4Si (Q4), (SiO)3SiOH (Q3), (SiO)2Si(OH)2 (Q2) and (SiO)Si(OH)3(Q1) in the crystals therefore 29Si MAS NMR also comes to the characterization some times in literature. For instance, Li et al. 81 with the 29Si MAS NMR revealed the existence of Ru in the MFI zeolite crystals (Figure 16).

1H MAS NMR spectra of spent samples. Copyright 2024 Elsevier.

29Si NMR of zeolite-based catalysts. Copyright 2024 Elsevier.

Herein, it is worth to mention that, CO adsorption FTIR is a valuable method for characterizing single metal atom such as Pt dispersed by the substrate or isolated by the other metals in alloys. If Pt exists as single atoms in the catalyst samples, the sample would only deliver the band (in range of 2,000–2,150 cm−1) of liner type CO adsorption (M = CO). Otherwise, bands (in range of 1,800–1,950 cm−1) of bridge type CO adsorption would also appear over the sample, as indicated by Zeng et al. (Figure 17C). For the CO adsorption FTIR over the sample, the liner type CO adsorption band shift generally provides information of electron cloud density of M influenced by the modifier that plays as electron cloud accepter or donor. For instance, In this method, Zhou et al. 98 proved that Zn in Pt@ZnS-1 catalyst sample not only isolates Pt atoms but also provide some electron cloud density to Pt.

Migration of indium oxide and formation of RhIn clusters. (A and B) High-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy (HAADF-STEM) images of Rh@S-1 (fresh) and Rh@S-1 (used). (C) CO-adsorbed FTIR spectra for Rh@S-1 (used) and In/Rh@S-1 (used). (D and E) HAADFSTEM images for In/Rh@S-1 (fresh) and In/Rh@S-1 (used). The red arrows point to white aggregates of In2O3 species on the outer surface (edge in the image) of S-1. (F) Normalized In K-edge XANES spectra of In/Rh@S-1 and reference samples. (G) Normalized Rh K-edge XANES spectra of Rh@S-1, In/Rh@S-1, and reference samples. (H) k2−weighted In K-edge EXAFS spectra of In/Rh@S-1 and reference samples. k denotes the wave vector of the photoelectron. (I) k2−weighted Rh K-edge EXAFS spectra of Rh@S-1, In/Rh@S-1, and reference samples. Copyright 2024 AAAS.

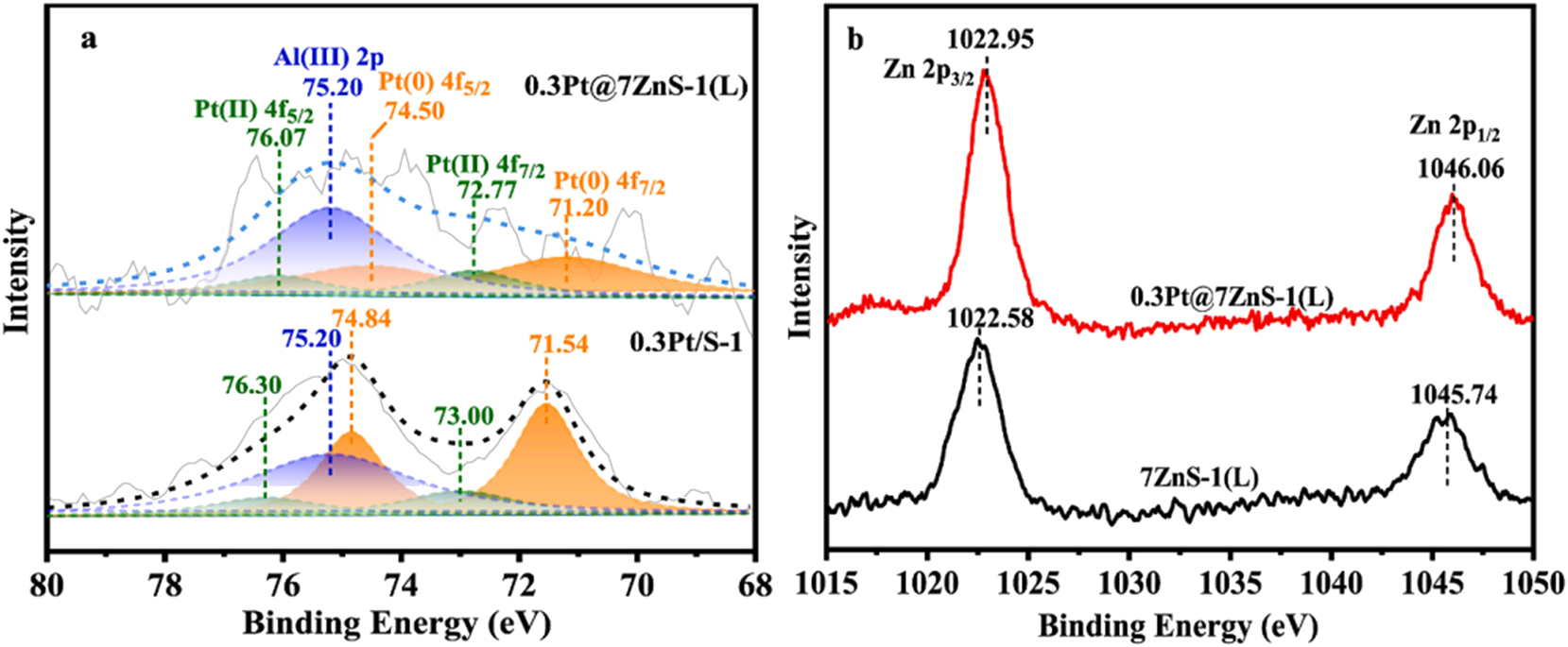

XPS is extensively applied by the researchers as well for the metal-zeolite hybrid catalysts. For instance, Zhou et al. 98 found that the Pt0 4f7/2 binding energy for 0.3Pt/S-1 is 71.54 eV, while it shifted down to 71.20 eV in the case of 0.3Pt@7ZnS-1(L); Zn 2p3/2 binding energy for the 7ZnS-1(L) sample is 1,022.58 eV, while it shifted up to 1,022.95 eV in the case of 0.3Pt@7ZnS-1, as shown in Figure 18, which indicates a donation of electron cloud from Zn to Pt in the case of 0.3Pt@7ZnS-1(L).

(A) Pt 4f XPS spectra of 0.3Pt@7ZnS-1(L) and 0.3Pt/S-1 (B) Zn 2p XPS spectra of 0.3Pt@7ZnS-1(L); and 7ZnS-1(L). Copyright 2025 Elsevier.

Of course, ICP and XRF are usually applied methods for determining the amount of framework heteroatoms, as long as no heteroatom exists as other chemical states.

4.2 Metal assembles and nanoparticles in zeolites

For some reactions, such as propane dehydrogenation, 16 , 58 , 66 , 71 , 72 , 73 , 74 , 75 n-hexane and n-heptane aromatization, 62 CO2 hydrogenation and formic acid dehydrogenation, 63 Fenton-like degradation of methylene blue, 64 regioselective hydroformylation, 95 dry reforming of methane, 19 selective catalytic reduction of NO x by CO, 100 CO oxidation, 101 the active state of metal elements in the metal-zeolite hybrid catalyst lie on metal assembles and nanoparticles. Hence, clearly indicating average coordination number or particle size of metals, whereby getting the stability information of the catalysts modified by the strategies of the authors is much important for the researchers. In this purpures, the following primary characterization methods often come into play.

The most often applied method is HAADF-STEM. As shown in Figure 17A and B, Zeng et al. revealed the In–Rh nanoparticles within S-1 zeolite.

To know the coordination number, the characterization of the hybrid sample with EXAFS is indispensable. For instance, Zeng et al. detected fresh and spent In/Rh@S-1 catalyst samples with this technique, from which the authors known that In–Rh alloy was formed in the catalyst during the reaction (Figure 17F, G, H, and I).

4.3 Effective strategies for controlling the structure of the hybrids

As mentioned before, metal-zeolite hybrids catalyst originated from one-pot synthesis were applied in a lot of reactions as catalysts. Herein, due to space limitation, we just represent the strategies being proposed by the authors to modify the property of catalyst utilized in the following three reactions.

4.3.1 Propane dehydrogenation

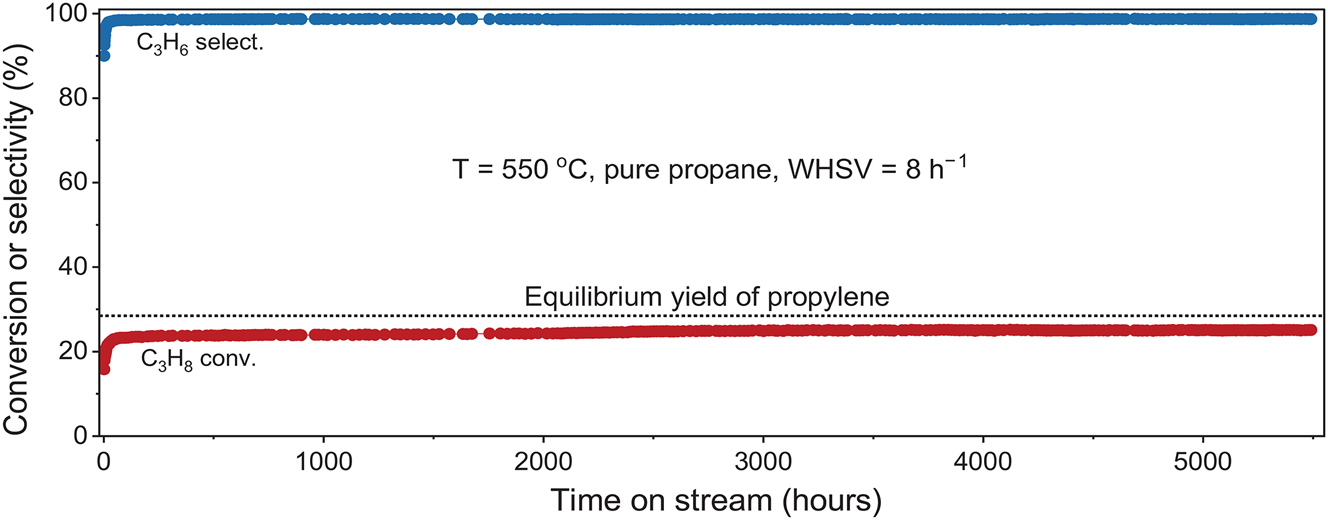

Maintaining the stability of single-atom catalysts in high-temperature reactions remains extremely challenging because of the migration of metal atoms under the hard reaction conditions (500–600 °C). Group of Wang 58 proposed a strategy of stabilizing single-atom noble metal atoms inside zeolite channels by harnessing a second metal to anchor them. The material with single-atom Rh inside S-1 zeolite was firstly obtained by one-pot synthesis, and the single-atom Rh–In cluster catalyst was obtained through subsequent in situ migration of In during alkane dehydrogenation. This catalyst demonstrated exceptional stability against coke formation for 5,500 h in continuous pure propane dehydrogenation with 99 % propylene selectivity and propane conversions close to the thermodynamic equilibrium value at 550 °C (Figure 19).

Stability evaluation of the In/Rh@S-1 catalyst for the dehydrogenation of pure propane. Reaction conditions: T = 550 °C, pure C3H8, WHSV = 8 h−1. Copyright 2024 AAAS.

4.3.2 Dry reforming of methane

For the catalysts applied in reaction of propane dry reforming of methane, embedding Ni nanoparticles (NPs) into zeolite has been widely accepted as one of solutions of Ni-based catalysts suffering from metal sintering and coke deposition at high operating temperatures (750–800 °C) that leads to rapid catalyst deactivation. Group of Shi 19 proposed a strategy of utilizing Ni2+/S-1 instead of NiO/S-1 as precursor so that preferably realized the ‘dissolution-recrystallization’ process in the one-pot synthesis. With this strategy, they made the Ni content of Ni@S-1 hybrid catalyst increased up to 20 wt% from 3 wt% but the sizes of Ni NPs maintained at ca. 4–5 nm (Figure 20). Due to the unique embedded structure, the 20 % Ni@S-1 catalyst performed a mass specific rate of 20.0 molCH4/gcat/h at 800 °C and a good stability running for 150 h.

Scanning transmission electron microscopy characterization for the Ni@S-1 catalysts. (A–D) STEM-HAADF (high-angle annular dark-field) images of the Ni@S-1 catalysts with different Ni loadings; the insets show the corresponding Ni NPs size distributions; High magnification STEM-HAADF image of 15 % Ni@S-1 on frontal view (E) and side view (F). Copyright 2022 Elsevier.

4.3.3 Regioselective hydroformylation

For indusial application of heterogeneous linear α-olefins’ hydroformylation, it suffers from quite low regioselectivity. Group of Zhang 95 proposed a strategy of confining active Rh clusters inside zeolites with special tunnels that could inhibit undesired by-product of branch-aldehyde formation to prepare the catalysts for the reaction. By one-pot synthesis method, the group obtained the Rh-MFI zeolite hybrids catalysts. They found that Rh clusters with size 0.3–0.6 nm are most active (Figure 21) and the tunnels of the zeolite plays much significant role for increasing the regioselectivity of the reaction.

Catalytic performance of the supported Rh catalysts. (A) The normalized initial reaction rates for the production of aldehydes and iso-olefins on various Rh catalysts at conversion levels below 15 %. (B) The percentage of different types of Rh species in three representative Rh-MFI catalysts: Rh-MFI-0.62, Rh-MFI-0.22 and Rh-MFI-0.007. Copyright 2024 Springer Nature.

5 Conclusions and perspectives

Confining metal species in zeolite crystals is an important way to endow the metal catalysts with the desired ability working at harsh reaction conditions. Just due to this primary reason, the M@zeolite type of metal catalyst has been extensively investigated by the researchers and the preparation has become one of hot subjects in the catalysis field in last few years. In these investigations, a lot of important and referable results have been obtained. Some important factors influencing the metal incorporation as well as the metal dispersion within the M@zeolite hybrid are listed below:

K existing in the gels largely influences the Pt dispersion within the S-1 crystals, though the optimum addition amount to the gel being indicated by TEM and/or STEM in the observable scale is different from that being detected by H2 (or CO) adsorption technique.

Organic ligands, including PDDA, TEPA, DCD, DETA, EDTA and EDA, are beneficial to the incorporation of metals into the zeolites, especially in the case of incorporating noble metals into S-1 zeolite.

ZnS-1 with Zn content up to 2 wt% could be in situ synthesized using zinc gluconate as zinc source in the case without organic ligand. Although there lack attempts synthesizing other zeolites in the absence of organic ligands, this result at least gives us a light that the metals existing in appropriate compound is favorable for incorporation to the zeolite.

For the M@S-1 hybrids obtained from the in situ metal incorporation method, with the M/Si ratio of gel increasing, the crystal size of the hybrid generally increases.

Nevertheless, there are also many challenges to be addressed. As the most important index for metal encapsulation materials, is the dispersity of the metal (little nanoparticles, metal clusters, or single-atom) within the zeolite crystals. Although the investigators aimed to achieve the possible encapsulation of single-atom metal into the zeolite crystals, most of the current syntheses still stay at the level of nanoparticles or metal clusters yet, especially in the case of encapsulating noble metal within the zeolite crystals with a larger metal loading amount.

Clearly, to increase the dispersity of the noble metal within the zeolite crystals by the in situ encapsulation synthesis, it is of importance to optimize the synthesis condition, in particular, the chose of appropriate of organic ligand. Herein, it should be noted that, the mechanism for organic ligand protecting the metals to be incorporated to the zeolites from getting into precipitate should be investigated. Although several organic ligands including PDDA, TEPA, DCD, DETA, EDTA, and EDA have been found and proposed to be beneficial for the metal incorporation, whereas no reliable principle directing the investigator reasonably chose organic ligand for incorporating their desired metal to zeolite.

For the encapsulation of the non-noble metal within the zeolite crystals, as mentioned before, synthesizing the zeolites with desired heteroatoms is an ideal way as long as desired amount of metal could be incorporated into the zeolite framework. Although the syntheses of this kind of zeolites in terms of heteroatoms Fe, Zn, Sn and Co have been succeeded, whereas the metal amount being incorporated to zeolite framework to be largely increased. Perhaps, as a primary way to address this challenge, is also relying on reasonable chose of organic ligand.

Funding source: National Natural Science Foundation of China

Award Identifier / Grant number: 22076017

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the reviewers for their insightful comments to improve the contributions in this work.

-

Research ethics: Not applicable.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Author contributions: XW: writing-original draft, data analysis, elaborated tables and figures. YC: writing-original draft, data analysis, elaborated tables and figures. JM: collecting data. HL: English proofreading. SL: supervision. All co-authors have contributed to the significant way to the final format of the review.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No 22076017).

-

Data availability: Not applicable.

References

1. Li, Z.; Lin, Q.; Li, M.; Cao, J.; Liu, F.; Pan, H.; Wang, Z.; Kawi, S. J. R. Recent Advances in Process and Catalyst for CO2 Reforming of Methane. Renewable Sustainable Energy Rev. 2020, 134, 110312; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2020.110312.Search in Google Scholar

2. Zhang, J.; Wang, L.; Zhang, B.; Zhao, H.; Kolb, U.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, L.; Han, Y.; Wang, G.; Wang, C. J. N. C.; Su, D. S.; Gates, B. C.; Xiao, F. S. Sinter-Resistant Metal Nanoparticle Catalysts Achieved by Immobilization within Zeolite Crystals via Seed-Directed Growth. Nat. Catal. 2018, 1, 540–546; https://doi.org/10.1038/s41929-018-0098-1.Search in Google Scholar

3. Ryoo, R.; Kim, J.; Jo, C.; Han, S. W.; Kim, J.-C.; Park, H.; Han, J.; Shin, H. S.; Shin, J. W. Rare-Earth–Platinum Alloy Nanoparticles in Mesoporous Zeolite for Catalysis. Nature 2020, 585, 221–224; https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2671-4.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

4. Jin, Z.; Wang, L.; Zuidema, E.; Mondal, K.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, J.; Wang, C.; Meng, X.; Yang, H.; Mesters, C. J. S.; Xiao, F. S. Hydrophobic Zeolite Modification for In Situ Peroxide Formation in Methane Oxidation to Methanol. Science 2020, 367, 193–197; https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaw1108.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

5. Hansen, T. W.; DeLaRiva, A. T.; Challa, S. R.; Datye, A. K. Sintering of Catalytic Nanoparticles: Particle Migration or Ostwald Ripening? Acc. Chem. Res. 2013, 46, 1720–1730; https://doi.org/10.1021/ar3002427.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

6. Wettergren, K.; Schweinberger, F. F.; Deiana, D.; Ridge, C. J.; Crampton, A. S.; Rötzer, M. D.; Hansen, T. W.; Zhdanov, V. P.; Heiz, U.; Langhammer, C. High Sintering Resistance of Size-Selected Platinum Cluster Catalysts by Suppressed Ostwald Ripening. Nano Lett. 2014, 14, 5803–5809; https://doi.org/10.1021/nl502686u.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

7. Dai, Y.; Lu, P.; Cao, Z.; Campbell, C. T.; Xia, Y. The Physical Chemistry and Materials Science behind Sinter-Resistant Catalysts. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2018, 47, 4314–4331; https://doi.org/10.1039/c7cs00650k.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

8. Wang, L.; Wang, L.; Meng, X.; Xiao, F. S. New Strategies for the Preparation of Sinter‐Resistant Metal‐Nanoparticle‐Based Catalysts. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, 1901905; https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201901905.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

9. Searles, K.; Chan, K. W.; Mendes Burak, J. A.; Zemlyanov, D.; Safonova, O.; Copéret, C. Highly Productive Propane Dehydrogenation Catalyst Using Silica-Supported Ga–Pt Nanoparticles Generated from Single-Sites. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 11674–11679; https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.8b05378.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

10. Xu, Z.; Yue, Y.; Bao, X.; Xie, Z.; Zhu, H. Propane Dehydrogenation over Pt Clusters Localized at the Sn Single-Site in Zeolite Framework. ACS Catal. 2019, 10, 818–828; https://doi.org/10.1021/acscatal.9b03527.Search in Google Scholar

11. Nakaya, Y.; Hirayama, J.; Yamazoe, S.; Shimizu, K.-i.; Furukawa, S. Single-Atom Pt in Intermetallics as an Ultrastable and Selective Catalyst for Propane Dehydrogenation. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 2838; https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-16693-9.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

12. Qi, L.; Babucci, M.; Zhang, Y.; Lund, A.; Liu, L.; Li, J.; Chen, Y.; Hoffman, A. S.; Bare, S. R.; Han, Y.; Gates, B. C.; Bell, A. T. Propane Dehydrogenation Catalyzed by Isolated Pt Atoms In ≡SiOZn–OH Nests in Dealuminated Zeolite Beta. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 21364–21378; https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.1c10261.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

13. Iida, T.; Zanchet, D.; Ohara, K.; Wakihara, T.; Román‐Leshkov, Y. Concerted Bimetallic Nanocluster Synthesis and Encapsulation via Induced Zeolite Framework Demetallation for Shape and Substrate Selective Heterogeneous Catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 6454–6458; https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.201800557.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

14. Liu, L.; Lopez-Haro, M.; Lopes, C. W.; Li, C.; Concepcion, P.; Simonelli, L.; Calvino, J. J.; Corma, A. Regioselective Generation and Reactivity Control of Subnanometric Platinum Clusters in Zeolites for High-Temperature Catalysis. Nat. Mater. 2019, 18, 866–873; https://doi.org/10.1038/s41563-019-0412-6.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

15. Wang, S.; Zhao, Z. J.; Chang, X.; Zhao, J.; Tian, H.; Yang, C.; Li, M.; Fu, Q.; Mu, R.; Gong, J. Activation and Spillover of Hydrogen on Sub-1 Nm Palladium Nanoclusters Confined within Sodalite Zeolite for the Semi‐hydrogenation of Alkynes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 7668–7672; https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.201903827.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

16. Sun, Q.; Wang, N.; Fan, Q.; Zeng, L.; Mayoral, A.; Miao, S.; Yang, R.; Jiang, Z.; Zhou, W.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, T.; Xu, J.; Zhang, P.; Cheng, J.; Yang, D.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Terasaki, O.; Yu, J. Subnanometer Bimetallic Platinum–Zinc Clusters in Zeolites for Propane Dehydrogenation. Angew. Chem. 2020, 132, 19618–19627; https://doi.org/10.1002/ange.202003349.Search in Google Scholar

17. Peng, H.; Dong, T.; Yang, S.; Chen, H.; Yang, Z.; Liu, W.; He, C.; Wu, P.; Tian, J.; Peng, Y.; Chu, X.; Wu, D.; Wang, Y.; Dai, S. Intra-Crystalline Mesoporous Zeolite Encapsulation-Derived Thermally Robust Metal Nanocatalyst in Deep Oxidation of Light Alkanes. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 295; https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-27828-x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

18. Chen, Y.; Zhu, X.; Wang, X.; Su, Y. A Reliable Protocol for Fast and Facile Constructing Multi-Hollow Silicalite-1 and Encapsulating Metal Nanoparticles within the Hierarchical Zeolite. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 419, 129641; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2021.129641.Search in Google Scholar

19. Liu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Gao, Z.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, L.; Wang, M.; Chen, B.; Diao, Y.; Li, Y.; Xiao, D.; Wang, X.; Ma, D.; Shi, C. Embedding High Loading and Uniform Ni Nanoparticles into Silicalite-1 Zeolite for Dry Reforming of Methane. Appl. Catal., B 2022, 307, 121202; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apcatb.2022.121202.Search in Google Scholar

20. Xu, S.; Slater, T. J.; Huang, H.; Zhou, Y.; Jiao, Y.; Parlett, C. M.; Guan, S.; Chansai, S.; Xu, S.; Wang, X.; Hardacre, C.; Fan, X. Developing Silicalite-1 Encapsulated Ni Nanoparticles as Sintering-/Coking-Resistant Catalysts for Dry Reforming of Methane. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 446, 137439; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2022.137439.Search in Google Scholar

21. Ma, Y.; Song, S.; Liu, C.; Liu, L.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, X.; Xu, H.; Guan, Y.; Jiang, J.; Song, W.; Han, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wu, P. Germanium-Enriched Double-Four-Membered-Ring Units Inducing Zeolite-Confined Subnanometric Pt Clusters for Efficient Propane Dehydrogenation. Nat. Catal. 2023, 6, 506–518; https://doi.org/10.1038/s41929-023-00968-7.Search in Google Scholar

22. Tao, P.; Wang, X.; Zhao, Q.; Guo, H.; Liu, L.; Qi, X.; Cui, W. Framework Ti-Rich Titanium Silicalite-1 Zeolite Nanoplates for Enhanced Photocatalytic H2 Production from CH3OH. Appl. Catal., B 2023, 325, 122392; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apcatb.2023.122392.Search in Google Scholar

23. Wei, X.; Cheng, J.; Li, Y.; Cheng, K.; Sun, F.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, Y. Bimetallic Clusters Confined Inside Silicalite-1 for Stable Propane Dehydrogenation. Nano Res. 2023, 16, 10881–10889; https://doi.org/10.1007/s12274-023-5953-y.Search in Google Scholar

24. Zhang, Y.; Li, S.; Fu, Y.; Zheng, L.; Li, H.; Kong, W.; Pan, B.; Li, J.; Zhang, J.; Sun, Y. Local Coordination Environment Triggers Key Ni-O-Si Copolymerization on Silicalite-2 for Dry Reforming of Methane. Appl. Catal., B 2024, 350, 123903; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apcatb.2024.123903.Search in Google Scholar

25. Wang, H.; Wang, L.; Xiao, F.-S. Metal@Zeolite Hybrid Materials for Catalysis. ACS Cent. Sci. 2020, 6, 1685–1697; https://doi.org/10.1021/acscentsci.0c01130.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

26. Liu, M.; Miao, C.; Wu, Z. Recent Advances in the Synthesis, Characterization, and Catalytic Consequence of Metal Species Confined within Zeolite for Hydrogen-Related Reactions. Ind. Chem. Mater. 2024, 2, 57–84; https://doi.org/10.1039/d3im00074e.Search in Google Scholar

27. Bo, S.; Lin, H.; Zhang, J.; Liao, W.; Yang, K.; Su, T.; Lü, H.; Zhu, Z. In Situ Encapsulation of Ultrasmall MoO3 Nanoparticles into Beta Zeolite for Oxidative Desulfurization. Green Chem. 2024, 26, 2661–2672; https://doi.org/10.1039/d3gc04808j.Search in Google Scholar

28. Chen, H.; Zhang, K.; Feng, Z.; Chen, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Peng, B.; Li, D.; Tian, Y.; Huang, R.; Li, Z. Construction of Pd@ K-Silicalite-1 via In Situ Encapsulation and Alkali Metal Modification for Catalytic Elimination of Formaldehyde at Room Temperature. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 341, 126889; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seppur.2024.126889.Search in Google Scholar

29. Cui, W.; Liu, Y.; Guo, P.; Wu, Z.; Kang, L.; Geng, H.; Chu, S.; Wang, L.; Fan, D.; Jia, Z.; Qi, H.; Luo, W.; Tian, P.; Liu, Z. High-Silica Faujasite Zeolite-Tailored Metal Encapsulation for the Low-Temperature Production of Pentanoic Biofuels. J. Energy Chem. 2024, 88, 552–560; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jechem.2023.10.009.Search in Google Scholar

30. Goto, H.; Abiru, R.; Kimura, K.; Fujitsuka, H.; Tago, T. Adsorption and Desorption Properties of Toluene on an Ni-Encapsulated Beta Zeolite Catalyst. Catal. Today 2024, 427, 114408; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cattod.2023.114408.Search in Google Scholar

31. Jiang, Y.; Lyu, X.; Chen, C.; Ren, A.; Qin, W.; Chen, H.; Lu, X. An Encapsulation Strategy to Design an In-TS-1 Zeolite Enabling High Activity and Stability toward the Efficient Production of Methyl Lactate from Fructose. Green Chem. 2024, 26, 5433–5440; https://doi.org/10.1039/d3gc05195a.Search in Google Scholar

32. Li, Y.; Du, T.; Chen, C.; Jia, H.; Sun, J.; Fang, X.; Wang, Y.; Na, H. Copper Nanoparticles Encapsulated in Zeolite 13X for Highly Selective Hydrogenation of CO2 to Methanol. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 111856; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2023.111856.Search in Google Scholar

33. Lin, F.; Zhang, L.; Du, H.; Li, Y.; Cheng, Z.; Yan, B.; Chen, G. Confinement Effect of Mn Nanoparticles Encapsulated in Zeolite for Efficient Catalytic Ozonation of S-VOCs at Room Temperature. Appl. Catal., B 2024, 349, 123908; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apcatb.2024.123908.Search in Google Scholar

34. Liu, H.; Li, J.; Liang, X.; Ren, H.; Yin, H.; Wang, L.; Yang, D.; Wang, D.; Li, Y. Encapsulation of Pd Single-Atom Sites in Zeolite for Highly Efficient Semihydrogenation of Alkynes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146, 24033–24041; https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.4c07674.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

35. Lu, Q.; Wang, H.; Sun, J.; Wei, X.-Z.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, X.; Chen, L.; Liu, J.; Chen, Y.; Ma, L. Solvent Effect in Selective Hydrogenation of Cinnamaldehyde over Pd–Ni Nanoclusters Encapsulated within Siliceous Zeolite. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2024, 367, 112979; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micromeso.2024.112979.Search in Google Scholar

36. Nie, F.; Sun, H.; Li, T.; You, Z.; Zhou, J.; Xu, W. Cobalt-Promoted Zn Encapsulation within Silicalite-1 for Oxidative Propane Dehydrogenation with CO2 by Microwave Catalysis at Low Temperature. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2024, 11, 6350; https://doi.org/10.1039/d4qi01560f.Search in Google Scholar

37. Tang, S.; Liu, H.; Li, T.; Wang, C.; Cui, Q.; Yue, Y.; Meng, X.; Bao, X. Encapsulating Platinum Nanoparticles into Multi-Hollow Silicalite-1 Zeolite for Catalytic Oxidation of Volatile Organic Compounds. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2024, 286, 119674; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ces.2023.119674.Search in Google Scholar

38. Tian, S.; Guo, H.; Zhao, Q.; Liu, L.; Wang, H.; Wang, X.; Zhang, S.; Cui, W. TS-1 Zeolite Encapsulated Pt Clusters with Enhanced Electronic Metal-Support Interaction of Pt–O(H)–Ti for Nearly-Zero-Carbon-Emitting Photocatalytic Hydrogen Production from Methanol. Appl. Catal., B 2024, 355, 124201; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apcatb.2024.124201.Search in Google Scholar

39. Velisoju, V. K.; Cerrillo, J. L.; Ahmad, R.; Mohamed, H. O.; Attada, Y.; Cheng, Q.; Yao, X.; Zheng, L.; Shekhah, O.; Telalovic, S.; Narciso, J.; Cavallo, L.; Han, Y.; Eddaoudi, M.; Ramos-Fernández, E. V.; Castaño, P. Copper Nanoparticles Encapsulated in Zeolitic Imidazolate Framework-8 as a Stable and Selective CO2 Hydrogenation Catalyst. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 2045; https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-46388-4.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

40. Ye, J.; Tang, X.; Cheng, L.; Zhang, S.; Zhan, W.; Guo, Y.; Wang, L.; Cao, X.-M.; Wang, K.-W.; Dai, S. Solvent-Free Synthesis Enables Encapsulation of Subnanometric FeOX Clusters in Pure Siliceous Zeolites for Efficient Catalytic Oxidation Reactions. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 24691–24702; https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.4c03083.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

41. Zhang, K.; Wang, N.; Meng, Y.; Zhang, T.; Zhao, P.; Sun, Q.; Yu, J. Highly Dispersed Pd-Based Pseudo-single Atoms in Zeolites for Hydrogen Generation and Pollutant Disposal. Chem. Sci. 2024, 15, 379–388; https://doi.org/10.1039/d3sc05851d.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

42. Zhang, Q.; Yang, S.; Zhang, H.; He, T.; Liu, W.; Sun, X.; Li, G.; Yu, Y.; Peng, H. Unveiling the Confinement and Interface Effect on Low Temperature Degradation of Toluene over Mesoporous Zeolite Encapsulated Pt-CeO2 Catalyst. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 485, 150004; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2024.150004.Search in Google Scholar

43. Zhang, Y.; Wang, W.; Zhou, L.; Zhang, Y. An Active and Stable Catalyst of Zn Modified Pt Nanoparticles Encapsulated within Silicalite-1 Zeolite for Dehydrogenation of Ethane. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2024, 648, 159099; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2023.159099.Search in Google Scholar

44. Zheng, Y.; Han, R.; Wang, Y.; Xu, W.; Liu, Q. High-Temperature Shock-Resistant Zeolite-Confined Ru Subnanometric Species Boosts Highly Catalytic Oxidation of Dichloromethane. Appl. Catal., B 2024, 355, 124195; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apcatb.2024.124195.Search in Google Scholar

45. Liu, Q.; Wang, Y.; Sang, X.; Bi, J.; Liu, N.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Z.; Han, Y. In-situ Encapsulation Synthesis of Fe-SAPO-34 for Efficient Removal of Tetracycline via Peroxydisulfate Activation: Highly Dispersed Active Sites and Ultra-low Iron Leaching. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 354, 129369; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seppur.2024.129369.Search in Google Scholar

46. Chen, S.; Chang, X.; Sun, G.; Zhang, T.; Xu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Pei, C.; Gong, J. Propane Dehydrogenation: Catalyst Development, New Chemistry, and Emerging Technologies. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50, 3315–3354; https://doi.org/10.1039/d0cs00814a.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

47. Dai, Y.; Gao, X.; Wang, Q.; Wan, X.; Zhou, C.; Yang, Y. Recent Progress in Heterogeneous Metal and Metal Oxide Catalysts for Direct Dehydrogenation of Ethane and Propane. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50, 5590–5630; https://doi.org/10.1039/d0cs01260b.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

48. Feng, B.; Wei, Y.-C.; Song, W.-Y.; Xu, C.-M. A Review on the Structure-Performance Relationship of the Catalysts during Propane Dehydrogenation Reaction. Pet. Sci. 2022, 19, 819–838; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.petsci.2021.09.015.Search in Google Scholar

49. Qu, Z.; Sun, Q. Advances in Zeolite-Supported Metal Catalysts for Propane Dehydrogenation. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2022, 9, 3095–3115; https://doi.org/10.1039/d2qi00653g.Search in Google Scholar

50. Yang, F.; Zhang, J.; Shi, Z.; Chen, J.; Wang, G.; He, J.; Zhao, J.; Zhuo, R.; Wang, R. Advanced Design and Development of Catalysts in Propane Dehydrogenation. Nanoscale 2022, 14, 9963–9988; https://doi.org/10.1039/d2nr02208g.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

51. Song, S.; Sun, Y.; Yang, K.; Fo, Y.; Ji, X.; Su, H.; Li, Z.; Xu, C.; Huang, G.; Liu, J.; Song, W. Recent Progress in Metal-Molecular Sieve Catalysts for Propane Dehydrogenation. ACS Catal. 2023, 13, 6044–6067; https://doi.org/10.1021/acscatal.3c00816.Search in Google Scholar

52. Sun, M.-L.; Hu, Z.-P.; Wang, H.-Y.; Suo, Y.-J.; Yuan, Z.-Y. Design Strategies of Stable Catalysts for Propane Dehydrogenation to Propylene. ACS Catal. 2023, 13, 4719–4741; https://doi.org/10.1021/acscatal.3c00103.Search in Google Scholar

53. Zhang, B.; Song, M.; Xu, M.; Liu, G. Recent Advances in Metal–Zeolite Catalysts for Direct Propane Dehydrogenation. Energ Fuel 2023, 37, 19419–19432; https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.energyfuels.3c03138.Search in Google Scholar

54. Xu, D.; Lv, H.; Liu, B. Encapsulation of Metal Nanoparticle Catalysts within Mesoporous Zeolites and Their Enhanced Catalytic Performances: A Review. Front. Chem. 2018, 6, 550; https://doi.org/10.3389/fchem.2018.00550.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

55. Chai, Y.; Shang, W.; Li, W.; Wu, G.; Dai, W.; Guan, N.; Li, L. Noble Metal Particles Confined in Zeolites: Synthesis, Characterization, and Applications. Adv. Sci. 2019, 6, 1900299; https://doi.org/10.1002/advs.201900299.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

56. Dai, C.; Du, K.; Song, C.; Guo, X. Recent Progress in Synthesis and Application of Zeolite-Encapsulated Metal Catalysts. Adv. Catal. 2020, 67, 91–133; https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.acat.2020.10.001.Search in Google Scholar

57. Zhou, J.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, H.; Xiong, C.; Hu, P.; Wang, H.; Chen, S.; Ji, H. Enhanced Performance for Propane Dehydrogenation through Pt Clusters Alloying with Copper in Zeolite. Nano Res. 2023, 16, 6537–6543; https://doi.org/10.1007/s12274-022-5317-z.Search in Google Scholar

58. Zeng, L.; Cheng, K.; Sun, F.; Fan, Q.; Li, L.; Zhang, Q.; Wei, Y.; Zhou, W.; Kang, J.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, M.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, L.; Huang, J.; Cheng, J.; Jiang, Z.; Fu, G.; Wang, Y. Stable Anchoring of Single Rhodium Atoms by Indium in Zeolite Alkane Dehydrogenation Catalysts. Science 2024, 383, 998–1004; https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adk5195.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

59. Li, T.; Wang, S.; Yu, H.; Yuan, L.; Zhang, D.; Yin, H. Encapsulation of Noble Metal Nanoclusters into Zeolites for Highly Efficient Catalytic Hydrogenation of Nitroaromatics. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2022, 61, 18762–18771; https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.iecr.2c02038.Search in Google Scholar

60. Tao, J.; Zhang, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, H.; Liu, W.; He, Y.; Yin, Y.; He, T.; Chen, J.; Wang, X.; Wu, D.; Peng, H. Elucidating the Role of Confinement and Shielding Effect over Zeolite Enveloped Ru Catalysts for Propane Low Temperature Degradation. Chemosphere 2022, 302, 134884; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2022.134884.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

61. Wang, N.; Sun, Q.; Bai, R.; Li, X.; Guo, G.; Yu, J. In Situ Confinement of Ultrasmall Pd Clusters within Nanosized Silicalite-1 Zeolite for Highly Efficient Catalysis of Hydrogen Generation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 7484–7487; https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.6b03518.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

62. Li, K.; Yan, M.; Wang, H.; Cai, L.; Wang, P.; Chen, H. Enhanced Stability of Pt@S-1 with the Aid of Potassium Ions for N-Hexane and N-Heptane Aromatization. Fuel Process. Technol. 2023, 252, 107982; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuproc.2023.107982.Search in Google Scholar

63. Sun, Q.; Chen, B. W. J.; Wang, N.; He, Q.; Chang, A.; Yang, C. M.; Asakura, H.; Tanaka, T.; Hülsey, M. J.; Wang, C. H.; Yu, J.; Yan, N. Zeolite‐Encaged Pd–Mn Nanocatalysts for CO2 Hydrogenation and Formic Acid Dehydrogenation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 20183–20191; https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.202008962.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

64. Guo, H.; Chen, L.; Zhang, X.; Chen, H.; Shao, Y. Silicalite-1 Zeolite Encapsulated Fe Nanocatalyst for Fenton-like Degradation of Methylene Blue. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 2023, 53, 251–259; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cjche.2022.03.010.Search in Google Scholar

65. Xie, X.; Liang, D.; Chen, M.; Wang, Y.; Li, W.; Wang, J.; Yuan, L. Dry Reforming of Methane over Silica Zeolite-Encapsulated Ni-Based Catalysts: Effect of Preparation Method, Support Structure and Ni Content on Catalytic Performance. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 7319–7336; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2022.11.167.Search in Google Scholar

66. Liu, M.; Sun, X.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Qin, Y.; He, B.; Mei, Y.; Zu, Y. Highly Dispersed and Stable NiSn Subnanoclusters Encapsulated within Silicalite-1 Zeolite for Efficient Propane Dehydrogenation. Fuel 2024, 357, 130069; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2023.130069.Search in Google Scholar

67. Hong, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Yan, N.; Liu, X.; Guo, P.; Liu, Z. Cu Nanoparticles Confined in Siliceous MFI Zeolite for Methanol Steam Reforming. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2023, 13, 6068–6074; https://doi.org/10.1039/d3cy01165h.Search in Google Scholar

68. Lin, L.; Cao, P.; Pang, J.; Wang, Z.; Jiang, Q.; Su, Y.; Chen, R.; Wu, Z.; Zheng, M.; Luo, W. Zeolite-Encapsulated Cu Nanoparticles with Enhanced Performance for Ethanol Dehydrogenation. J. Catal. 2022, 413, 565–574; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcat.2022.07.014.Search in Google Scholar

69. Feng, W.; Xiao, Z.; Chen, B.; Pi, Y.; Hu, C.; Zhang, W.; Meng, Q.; Wang, T. In Situ Confinement of Ultrasmall Cu Nanoparticles within Silicalite-1 Zeolite for Catalytic Reforming of Methanol to Hydrogen. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 61, 113–124; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2024.02.272.Search in Google Scholar

70. Xie, L.; Wang, R.; Chai, Y.; Weng, X.; Guan, N.; Li, L. Propane Dehydrogenation Catalyzed by In-Situ Partially Reduced Zinc Cations Confined in Zeolites. J. Energy Chem. 2021, 63, 262–269; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jechem.2021.04.034.Search in Google Scholar

71. Xu, Z.; Gao, M.; Wei, y.; Yue, Y.; Bai, Z.; Yuan, P.; Fornasiero, P.; Basset, J.; Mei, B.; Liu, Z.; Zhu, H.; Ye, M.; Bao, X. Pt Migration-Lockup in Zeolite for Stable Propane Dehydrogenation Catalyst. Nature 2025, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09168-8.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

72. Wang, Y.; Hu, Z.-P.; Lv, X.; Chen, L.; Yuan, Z.-Y. Ultrasmall PtZn Bimetallic Nanoclusters Encapsulated in Silicalite-1 Zeolite with Superior Performance for Propane Dehydrogenation. J. Catal. 2020, 385, 61–69; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcat.2020.02.019.Search in Google Scholar