Abstract

Burning fossil fuels has significantly worsened environmental pollution, particularly due to the release of carbon dioxide emissions. The global efforts to promote renewable energy solutions, like electrocatalytic water splitting, have gained momentum. Scientists are focusing on the development of sustainable methods like water splitting to reduce dependence on conventional fuels. Developing affordable and effective electrocatalysts is crucial for multifunctional electrochemical water splitting (ECWS). In comparison to traditional electrocatalysts, metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) exhibit favorable catalytic performance for electrochemical water decomposition because of their plentiful porosity, surface area, and topologies for enhanced production of hydrogen (H2) and oxygen (O2) gas. When combined with MOF, graphene creates a synergistic hybrid nanomaterial that is more stable, adaptable, and durable. The primary goal of this review article is to conduct an in-depth investigation of the latest advancements in MOFs and MOF-GO electrocatalysts for water electrolysis. Herein, we have covered the plausible mechanism for the overall water-splitting electrocatalytic processes and several important factors influencing their electrocatalytic response. We also discussed the recent progress in the performance and stability of MOFs and MOF-GO electrocatalysts for water-splitting reactions. Finally, the article highlights the challenges and application of MOF and MOF-GO composites and the future preference for water-splitting applications.

1 Introduction

In the modern era, producing clean, renewable, and sustainable energy is crucial for achieving a pollution-free environment. 1 With an ever-increasing population, the demand for energy rises annually, yet over 80 % of our energy production still relies on fossil fuels. The combustion of fossil fuels generates greenhouse gases, pollution, and global warming, all posing severe threats to the environment. 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 Covering more than 70 % of the Earth’s surface, the ocean has vast potential as a resource for clean energy production. Often referred to as blue energy, ocean energy serves as a significant renewable power source through water energy. 6 This water-based energy is harnessed to produce hydrogen (H₂), a promising alternative to fossil fuels, contributing to a cleaner environment while enabling high-energy output under moderate temperature and pressure conditions. 7 The investment in hydrogen production has surged in recent years, recognising hydrogen as one of the highest-energy resources available and abundantly present across the universe. Its versatility spans a wide range of applications, from energy capture to production. Perhaps the most significant advantage of hydrogen is its clean combustion, resulting in zero pollutant emissions, particularly greenhouse gases. 8 , 9

A wide range of research has been done on water splitting with electrocatalysts. The two half-cell reactions are included: the anode produces oxygen by oxygen evolution reactions (OER), while the cathode produces hydrogen by hydrogen evolution reactions (HER). 1 These are two surface reactions depending on the medium required for the electrolyte. The water-splitting hydrogen generation process can be improved by carefully selecting the suitable electrocatalyst. 2 Electrocatalysis has played a significant role in overcoming kinetic energy barriers in electrochemical cells for water splitting. The extravagant noble metals (Pt, Pd and Ru) 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 were initially used for effective electrocatalytic hydrogen production. However, the limited availability of noble metals demands the use of cost-effective, stable and sustainable water-splitting materials to cut down the use of noble metals. 7 , 8 , 9 Developing composites and hybrid catalysts has opened new avenues for improving water electrolysis. Metal-organic framework (MOF) composites have more active sites, large surface area, porosity, and crystallinity, so they are utilized as alternatives for noble metals. MOF refers to crystalline, porous organic-inorganic hybrid materials with organic linkers surrounding positively charged central metal ions. 10 In recent times, MOFs have played an emerging role in fuel cells, 11 , 12 supercapacitor devices, 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 carbon capture, 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 photochemical and electrochemical reactions for overall water splitting (HER and OER) hydrogen production. 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 MOF features are designable structures with high surface area, large surface channels and possible active sites for catalysis. They are categorized into three primary groups: MOF-derived composites, MOF-based composites, and pristine MOFs. Enormous research and reviews are being done on pristine MOF for water-splitting hydrogen production using photocatalysts, electrocatalysts, and photoelectrocatalysts.

However, pristine MOFs and simple MOF-based materials show less stability, specific surface functionalization and limited accessibility to pores. 28 , 29 To solve these issues, metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) with graphene oxide (GO) materials are being used in recent research for better hydrogen production because of their enhanced mechanical strength, high surface area, improved stability, better chemical functionality and tunable porosity as compared to pristine MOF and simple MOF-based composites. Graphene is a single-layered carbon atoms network arranged in a two-dimensional hexagonal arrangement resembling a honeycomb crystal’s layered structure. 30 , 31 Graphene exhibits remarkable thermal conductivity, mechanical strength, transparency and surface modification. These properties make it an emerging nanomaterial among all the other recently studied materials in the 21st century. Graphene exists in the form of pristine graphene, graphene oxide and reduced graphene. Graphene has versatile applications in the scientific world, such as solar cells, fuel cells, energy storage devices, and biomedical devices. Graphene acts as a pseudocapacitive material, having significantly enhanced properties when incorporated into composite material. In MOF-GO materials, when graphene oxides are coupled with MOF, they enhance their activity and open up new opportunities in energy storage, catalysis and environmental sustainability. 32 , 33 , 34 , 35

In recent years, numerous comprehensive reviews have been published on advancing environmental sustainability. While several reviews have focused on pristine metal-organic frameworks, MOF-based materials, or MOF-derived materials, MOF-GO-based and derived materials are now emerging as key players in overall water splitting. Drawing from recent research and literature, this review provides an in-depth exploration of the current significance of MOF-GO-based and derived materials as electrocatalysts for overall water splitting, specifically targeting HER and OER in hydrogen production. The roadmap of this review emphasizes the role of electrocatalysts in water splitting, highlights MOF-based materials, and underscores the recent developments in designing MOF-GO-based and derived materials for enhanced hydrogen production through water splitting. The authors have chosen this topic due to the critical and evolving role of MOF-GO-based materials in sustainable energy solutions.

2 Fundamentals of electrocatalysis in water splitting

2.1 Mechanism of electrocatalysis for HER and OER water splitting

Electrocatalysis is a unique field of electrochemistry that mainly focuses on the type of catalyst used to enhance the speed of electrochemical reactions. In recent decades, progress in electrochemistry has been crucial for the development of a sustainable environment and energy conversion, especially in fuel cells and electrocatalytic cells. 36 Electrochemistry technologies utilize electrical energy to facilitate energy-demanding reactions such as conversion of carbon dioxide to hydrocarbons, nitrate conversion reactions and water electrolysis in hydrogen fuel cells. The electrolysis of water results in oxidation for the production of oxygen gas at the anode, and hydrogen gas evolves at the cathode due to the reduction of protons, as exhibited in Figure 1a. The overall reaction results in chemical oxidation-reduction of electrical energy and water. 37 , 38 Water splitting involves two crucial processes which result in hydroxide ions (OH‾) plus hydrogen gas (H2) production at the cathodic end during the HER process when water is reduced. In the OER mechanism, the oxidation of hydroxide ions takes place at the anode to produce water (H2O) and oxygen gas (O2). In addition, the half-reaction of water electrolysis specifically in an acidic medium exhibits a polarization curve for HER and OER as shown in Figure 1b.

![Figure 1:

Overview of general experimental setup for water splitting. (a) The graphical representation of H2 and O2 generation from water dissociation; (b) polarization curve and half-reaction of water dissociation in acid electrolyte. Reproduced with permission from Ref. 39]. Copyright 2020. The Royal Society of Chemistry.](/document/doi/10.1515/revic-2024-0098/asset/graphic/j_revic-2024-0098_fig_001.jpg)

Overview of general experimental setup for water splitting. (a) The graphical representation of H2 and O2 generation from water dissociation; (b) polarization curve and half-reaction of water dissociation in acid electrolyte. Reproduced with permission from Ref. 39]. Copyright 2020. The Royal Society of Chemistry.

The oxygen evolution reaction in neutral and acidic media follows a sequence of proton-coupled electron transfer (PCET) steps, although the mechanisms differ slightly due to the environment. In a neutral medium, water molecules adsorb onto the catalyst surface, forming a hydroxyl intermediate (M–OH), which is deprotonated and oxidized to an oxo species (M = O). This oxo intermediate reacts with water to form a hydroperoxo species (M–OOH), which eventually releases oxygen (O₂) while regenerating the catalytic site. The presence of buffering species in neutral media plays a crucial role in stabilizing intermediates and facilitating proton removal. In acidic media, the reaction also progresses through similar intermediates, starting with the adsorption of a water molecule to form M–OH₂⁺. Successive PCET steps lead to the formation of M = O and M–OOH intermediates, which release oxygen and regenerate the active site. The acidic environment enhances proton transfer kinetics but requires robust catalysts, such as IrO₂ or RuO₂, to resist corrosion and maintain stability under harsh conditions. Both mechanisms underscore the importance of intermediate stabilization and efficient catalyst design for improved OER performance. 40 In an alkaline medium, HER occurs through three primary steps: the Volmer step, which involves the electrochemical reduction of water to form adsorbed hydrogen atoms (H), and hydroxide ions (OH⁻); the Heyrovsky step, combining H with another water molecule to release molecular hydrogen (H₂); or the Tafel step, where two H atoms combine to form H₂ directly. The alkaline environment introduces challenges due to slower kinetics compared to acidic media, requiring optimized catalysts with strong water-splitting and hydrogen adsorption/desorption capabilities. These mechanisms highlight the critical role of intermediate species and the need for advanced electrocatalysts for efficient water-splitting reactions. 41

2.2 Factors influencing electrocatalytic HER and OER water splitting

It is essential to understand and optimize the factors that influence electrocatalytic performance to achieve high efficiency in electrochemical water splitting for hydrogen and oxygen production. Electrocatalysts must possess specific qualities to ensure fast reaction kinetics, high catalytic activity, and stable operation under various conditions. Several key parameters, such as surface area, overpotential, pH, and Tafel slope, have a direct impact on the effectiveness and stability of electrocatalysts in HER and OER. By analyzing and optimizing these factors, researchers can enhance the reaction rate, reduce energy input requirements, and improve overall system efficiency. Below is a detailed discussion of each factor and its role in electrocatalysis:

Surface area: The surface area of the electrocatalyst highly affects the available active sites, catalytic activity and thermal stability of the material being used in an electrochemical reaction. The interaction among the active sites of the catalyst is automatically improved by the expansion of surface area. However, the larger surface areas of the supporting material increase intrinsic activity, maintain electrical conductivity, avoid agglomeration, and uniformly distribute nanomaterials.

Overpotential is a challenging yet crucial factor in electrocatalytic HER and OER water-splitting hydrogen production. The lower value of overpotential plays a significant role. Although it is challenging to maintain, it can be reduced by stabilizing electrocatalysts’ intrinsic properties and concentration polarization.

pH of the electrolyte: It is a critical factor affecting the choice of electrocatalyst, operational conditions, and the available electrolyte source. Maintaining the pH in both acidic and alkaline mediums is crucial, as it minimizes operational costs and ensures smooth electron transfer dynamics at fluctuating current densities.

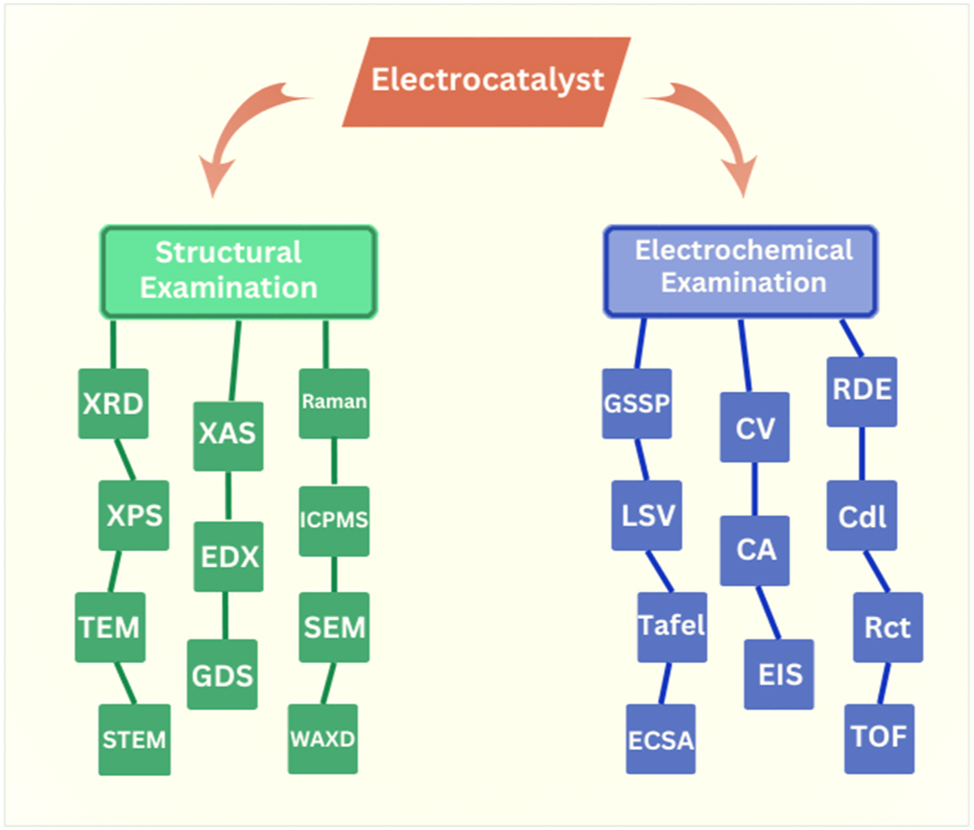

Tafel slope: One of the most critical factors in electrocatalysis is the Tafel slope. It offers essential details regarding the electrocatalysts kinetics, efficiency, and reaction mechanism. A smaller value of the Tafel slope indicates better reaction kinetics and efficiency of the electrocatalyst. A few additional parameters also influence the efficiency and structural characteristics of electrocatalysts for the production of oxygen and hydrogen gas, as shown in Figure 2.

The flow chart displays key factors and characterizations for the electrocatalytic performance of electrocatalysts.

3 Sustainable energy production for electrocatalytic HER and OER water splitting

The hydrogen economy presents a promising shift from the hydrocarbon-based model to renewable green hydrogen production through water electrolysis. Transition metal oxides, phosphides, and nitrides are used for OER and transition metal alloys, while carbides are used for HER. 42 These are some of the electrocatalysts made of non-precious metals for HER and OER that have been the subject of recent research advances. 43 , 44 John Bockris proposed the term hydrogen economy in the 1970s. 45 Hydrogen energy is recognized as a clean and highly promising energy generated through water electrolysis by renewable sources most likely wind, geothermal, and solar energy. The generated green hydrogen is now utilized in various applications, including fuel cells, petroleum refining, and electric vehicles. 46 , 47 One environmentally acceptable and sustainable way for producing hydrogen is water splitting. It uses water as a source to maintain a closed hydrogen cycle with no carbon emission. 48 Water electrolysis holds the potential to convert excess energy to chemical fuels with improved efficiency and cost-effective hydrogen production. However, high-cost energy production in recent years hinders the adaptation of strategy on a large scale. 49 , 50 Researchers are actively synthesizing cost-effective HER/OER pristine MOFand MOF-GO electrocatalysts with enhanced active sites. The number of publications in this field is significant evidence of research progress. 51 , 52

3.1 Electrocatalytic water splitting by MOFs and MOF-GO composites

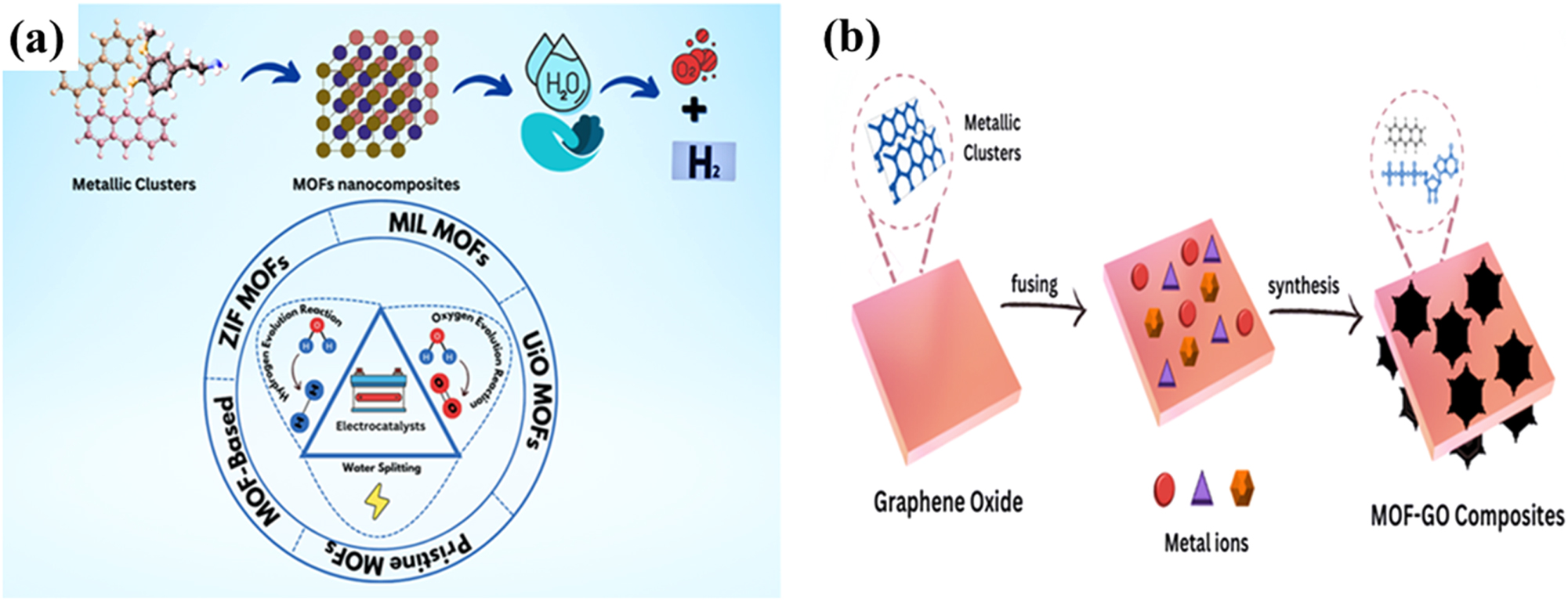

In recent years, MOF based electrocatalysts have gained significant attention to enhance the efficiency of water-splitting reactions. Many types of research have been done on electrocatalytic water splitting processes, such as the alteration of the core metallic framework of MOF, introducing variable functionalizable linkers and integration of additional metal atom/substrate to the MOF structure. 53 , 54 , 55 , 56 , 57 As a result, desirable materials electronic structures altered. This trend reveals the emergence of novel MOF materials for electrocatalytic water splitting, such as pure, bimetallic composites, MOF-based materials, and MOF-derived materials. 58 , 59 , 60 , 61 Incorporating graphene oxide into a MOF results in a hybrid (MOF-GO) composite, exhibiting nanosheets-like morphology for improving electron and mass transmission and enabling prominent exposure to catalytic active sites. Ultimately, this leads to an electrochemical reaction that improves the production of hydrogen (H2) as well oxygen (O2) via water splitting.

3.2 Plausible mechanism of electrocatalytic water splitting by MOF and MOF-GO composites

The MOF-based electrocatalytic water splitting plays a pivotal role due to the remarkable structural properties of MOFs, such as high porosity, specific surface area, functionalizable linkers and tunable pore structures. 62 , 63 This mechanism promotes the most directed means of hydrogen production at a given voltage of 1.23 V at standard conditions (25 °C and 1 atm) by absorbing water molecules onto the surface of MOF electrocatalyst. 64 Additionally, transition metal nitrides, carbides, phosphides and sulfides exhibit cost-effective and efficient electrocatalytic HER and OER water splitting across the suitable electrolytic system. 65 , 66 , 67 Moreover, the intrinsic electrocatalytic properties of electrocatalysts can be enhanced through the introduction of additional metal atoms or substrates. This addition modulates the electronic structures, facilitating enhanced charge transfer and active sites of electrocatalysts for hydrogen and oxygen generation, as shown in Figure 3a. The synthesis of clean energy materials addresses global energy needs for sustainability. 68 , 69 , 70 , 71 Nowadays, metal-organic frameworks excel in catalytic activity with the combined effect of graphene in the form of graphene oxides (GO) or reduced graphene (rGO), as depicted in Figure 3b, with enhanced electrochemical performance through efficient electron transfer, including active site exposure, catalyst dispersion, charge mobility and stability. 72 The introduction of GO increases both HER and OER exchange current density and reduces electrochemical resistance. 73 , 74

The graphical illustration of a plausible mechanism of electrocatalytic water splitting (a) metal-organic framework nanocomposites; (b) metal-organic framework clusters on graphene oxides for MOF-GO nanocomposites.

3.3 MOFs and MOF-GO electrocatalysts for HER

The creation of electrocatalysts with improved efficiency plays a pivotal role in a green environment for HER water splitting. Some recent electrocatalysts have been mentioned, which explore the catalytic activities of highly efficient MOF and MOF-GO-dependent HER electrocatalysts listed in Table 1. Jiang et al. presented electrodeposited nickel-phosphorus (Ni–P) film, which exhibits remarkable overpotential values −93 mV (at 10 mA/cm2). 75 The remarkable activity of Ni–P film is due to the amazing performance of Pt and IrO2. Zheng et al. reported the material’s significant current density HER activity is demonstrated by the nanofoam catalyst, which employs its trifunctional layer and contains selenium on the surface and cobalt (Co/Se–MoS2–NF) on the inner layer. 76 The lower overpotential value of 382 mV reveals that cobalt atoms are confined in inner layers to stimulate neighboring sulphur atoms. Dai et al. proved the chemical interaction of a one-pot solvothermal technique for the hydrogen evolution process to create molybdenum polysulfide (MoSx) embedded over a porous Zr-based MOF (Zr-MOF/UiO-66-NH2). 77 Under acidic conditions, the stabilized electrolytic HER performance displays an extraordinary Tafel slope with 59 mV dec−1 and an overpotential of 200 mV. These results show the versatility of Mo-based HER electrocatalysts, which offer faster and less expensive proton-transfer electrocatalysts. An alternative method to create cobalt diselenide (MOF-CoSe2) nanoparticles formed from metal-organic frameworks is to use the in-situ selenium of Co-based MOFs to attach the particles on nitrogen-doped graphitic carbon. 78 MOF-CoSe2 electrocatalytic performance is less significant than that of the MoS2/CoSe2 hybrid catalyst, created with identical 0.5 M H2SO4 conditions, as shown in Figure 4a. 79 The significant part of the MoS2/CoSe2 hybrid catalyst was confirmed by the high-resolution STEM-EDX elemental mapping (Figure 4b). Although molybdenum disulfide and cobalt diselenide materials work synergistically, MoS2/CoSe2 has high HER performance, as evidenced by binding energy XPS spectra (Figure 4c) overpotential of 68 mV. This suggests that MoS2/CoSe2 exhibits a superior activity surface area and many active sites as shown in the Volmer-Tafel pathway for hydrogen evolution reaction (Figure 4d).

Electrocatalytic H2 production by recent publications of MOFs/MOF-GO electrocatalysts.

| Catalysts | Electrolyte | Overpotential (mV) | Tafel slope (mV dec−1) | Stability | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ni–P | 1 M KOH | −93 | 43 | 24 h | 75 |

| Co/Se–MoS2–NF | 0.5 M H2SO4 | 382 | 67 | 360 h | 76 |

| Zr-MOF/UiO-66-NH2 | 0.5 M H2SO4 | 59 | 200 | 7 h | 77 |

| MOF-CoSe2 | 0.5 M H2SO4 | 150 | 42 | 2,000 cycles | 78 |

| MoS2/CoSe2 | 0.5 M H2SO4 | 68 | 36 | 24 h | 79 |

| Co–Cl4-MOF | 0.1 M KOH | 283 | 86 | 24 h | 80 |

| 3D-Ni(fcdHp)n | 0.5 M H2SO4 | 60 | 350 | 10,000 cycles | 81 |

| ZnfcdHp | 0.5 M H2SO4 | 340 | 110 | 1,000 cycles | 82 |

| UU-100(Co) | 0.1 M NaClO4/0.2 M acetate | N/A | 250 | 18 h | 83 |

| Ni@NCS-800 | 1 M KOH | 366 | 93 | 200 cycles | 84 |

| Ni X Ru-TDA/NF | 1 M KOH | 35 | 49 | 60 h | 85 |

| COP/rGO-400 | 1 M KOH | 38 | 150 | 22 h | 86 |

| CoNi-MOF-PCG | 1 M KOH | 265 | 44.5 | Over 3,000 s | 87 |

| Ni2P/rGO | 1 M KOH | 142 | 58 | 20 h | 88 |

| V-NixFey-MOF/GO | 0.5 M H2SO4 | 90 | 150 | Over 20 h | 89 |

| GO/Cu-MOF | 0.3 M H2SO4 | N/A | 125 | N/A | 91 |

![Figure 4:

Effect of structural characteristics and synthesis methods on the HER performance of the MoS2/CoSe2 hybrid catalyst. (a) The synthesis route of MoS2/CoSe2 hybrid catalyst; (b) STEM-EDX elemental mapping; (c) XPS spectra; (d) reaction route of HER according to Volmer-Tafel pathway. Reproduced with permission from Ref. 79]. Copyright 2015. Nature Communications.](/document/doi/10.1515/revic-2024-0098/asset/graphic/j_revic-2024-0098_fig_004.jpg)

Effect of structural characteristics and synthesis methods on the HER performance of the MoS2/CoSe2 hybrid catalyst. (a) The synthesis route of MoS2/CoSe2 hybrid catalyst; (b) STEM-EDX elemental mapping; (c) XPS spectra; (d) reaction route of HER according to Volmer-Tafel pathway. Reproduced with permission from Ref. 79]. Copyright 2015. Nature Communications.

Li et al. revealed that halogen atoms enhance the catalyst activity via the desorption of hydrogen from cobalt sites via synthesizing 2D polyhalogenated Co(II)-based MOF (Co–Cl4-MOF) to explore the effect of substituted halogen for electrochemical HER with the resulting yield of 81 % based on Cl4–H2pta and lower overpotential (283 mV). 80 Khrizanforova et al. prepared a 3D Ni redox active MOF as an efficient electrocatalyst, which is based on 4,4′-Bipyridine and Ferrocenyl Diphosphinate ligands for HER. 81 The addition of a 4,4′-bipyridine linker enhances Ni-MOF HER kinetic properties in both an organic and aqueous environment. The electrochemical studies demonstrate that Ni-MOF has superior HER efficiency due to a small overpotential of 350 mV and excellent durability (∼10,000 cycles). Shekurov et al. synthesized a novel 1D helical Zn redox active coordinated ZnfcdHp polymer as an efficient electrocatalyst for HER based on ferrocenylenbis (H-phosphinic) acid (H2fcdHp) ligand and the Zn nitrate salt, as depicted in Figure 5a. Figure 5b depicts the Helical chain’s chirality (R-enantiomer, S-enantiomer). The ZnfcdHp catalyst’s hydrogen evolution reaction shows an overpotential of 340 mV and Tafel slope of 110 mV dec−1 with linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) polarization curve for extended stability (Figure 5c and d). Furthermore, these catalysts were considered superior substitutes for Pt-catalysts in hydrogen evolution reactions. 82

![Figure 5:

Synthesis and structural features of the 1D helical ZnfcdHp polymer catalyst and its HER performance. (a) The graphical illustration for synthesis route of 1D helical Zn redox active coordinated ZnfcdHp polymer; (b) helical chains chirality (R-enantiomer, S-enantiomer) and, (c) LSV polarization curves with corresponding (d) Tafel slopes. Reproduced with permission from Ref. 82]. Copyright 2019. Royal Society of Chemistry.](/document/doi/10.1515/revic-2024-0098/asset/graphic/j_revic-2024-0098_fig_005.jpg)

Synthesis and structural features of the 1D helical ZnfcdHp polymer catalyst and its HER performance. (a) The graphical illustration for synthesis route of 1D helical Zn redox active coordinated ZnfcdHp polymer; (b) helical chains chirality (R-enantiomer, S-enantiomer) and, (c) LSV polarization curves with corresponding (d) Tafel slopes. Reproduced with permission from Ref. 82]. Copyright 2019. Royal Society of Chemistry.

Roy et al. introduced the metal-organic frameworks composed of cobaloximes-based catalyst UU-100(Co), which act as metallo-linkers in the clusters of hexanuclear zirconium for efficient hydrogen evolution catalytic activity. 83 The obtained Tafel slope value (250 mV dec−1) claims better HER activity with 309 µmol H2 cm−2 generation with 18 h of electrolysis. The study reveals that cobaloximes have enhanced structural integrity with MOFs, leading to at least 50–200 times increase in turnover numbers with high porosity and redox-active metallo-linkers than traditional cobaloximes for hydrogen generation. B. Patel et al. presented the development of an effective self-sacrificial Nickel-based metal-organic framework (Ni@NCS) bifunctional electrocatalyst by facile pyrolysis method. 84 The remarkable catalytic qualities of the Ni@NCS-800 nanomaterial, Ni@NCS-800 displays an overpotential of 366 mV for HER while reaching a current density of 10 mA cm−2 and a Tafel slope value of 93 mV dec−1 supported by the exceptional catalytic properties of Ni@NCS-800 nanomaterial. The stability of the catalyst assures that it is a simple, non-precious and stable catalytic material for HER activity. Lin et al. synthesized Ru-doped Nickel thiophene dicarboxylic acid (NiXRu-TDA/NF) composites using a one-pot solvothermal method, as shown in Figure 6a. 85 The morphological structure and elemental analysis of NiXRu-TDA/NF were present in TEM images and EDX mapping (Figure 6b). However, the LSV curves with histograms overpotential of the catalyst’s HER performance reported, showing a Tafel slope around 49 mV dec−1 (Figure 6c and d) and a charge transfer resistance (Rct) of 5.9 Ω for hydrogen generation by water splitting. Additionally, the catalyst performs more effectively when the cathode and anode are submerged in a water electrolysis system, achieving a cell voltage of 1.53 V with a current density of 10 mA cm−2.

![Figure 6:

Synthesis, structural analysis, and HER performance of NiXRu-TDA/NF catalyst. (a) The schematic diagram for synthesis of Ru-doped Nickel thiophene dicarboxylic acid (Ni

X

Ru-TDA/NF); (b) TEM images; (c) LSV curves, histograms overpotentials and (d) Tafel slopes of material. Reproduced with permission from Ref. 85]. Copyright 2023. Elsevier.](/document/doi/10.1515/revic-2024-0098/asset/graphic/j_revic-2024-0098_fig_006.jpg)

Synthesis, structural analysis, and HER performance of NiXRu-TDA/NF catalyst. (a) The schematic diagram for synthesis of Ru-doped Nickel thiophene dicarboxylic acid (Ni X Ru-TDA/NF); (b) TEM images; (c) LSV curves, histograms overpotentials and (d) Tafel slopes of material. Reproduced with permission from Ref. 85]. Copyright 2023. Elsevier.

Emerging research has been performed for the development of innovative MOF-GO-based composites and promising applications of MOF-GO materials as electrocatalysts owing to their specialized topologies and diverse functional groups and central metal atoms, as listed in Table 1. Jiao et al. prepared a layered metal-organic framework CoP/reduced graphene oxide composite (COP/rGO-400) followed by pyrolysis and subsequent phosphating process for overall water splitting (Figure 7a) in an alkaline environment of 1 M KOH demonstrated the HER performance at an overpotential of 150 mV having Tafel slope value 38 mV dec−1 and LSV polarization curves with 100 % faradaic efficiency (Figure 7e–g). The morphological structure of COP/rGO-400 was present in SEM and TEM images (Figure 7b–d). This work describes how graphene oxide and metal-organic frameworks can be integrated with MOF to create effective electrocatalysts for various applications. 86

![Figure 7:

Synthesis, structural analysis, and HER performance of CoP/rGO-400 composite catalyst. (a) Graphical illustration for synthesis route of CoP/reduced graphene oxide composite (COP/rGO-400); (b) scanning electron microscope (SEM) image; (c) TEM, and (d) high resolution TEM image of COP/rGO-400; (e) LSV curve, (f) Tafel slope, and (g) time-dependent current density curves at 1 M KOH solution. Reproduced with permission from Ref. 86]. Copyright 2016. Royal Society of Chemistry.](/document/doi/10.1515/revic-2024-0098/asset/graphic/j_revic-2024-0098_fig_007.jpg)

Synthesis, structural analysis, and HER performance of CoP/rGO-400 composite catalyst. (a) Graphical illustration for synthesis route of CoP/reduced graphene oxide composite (COP/rGO-400); (b) scanning electron microscope (SEM) image; (c) TEM, and (d) high resolution TEM image of COP/rGO-400; (e) LSV curve, (f) Tafel slope, and (g) time-dependent current density curves at 1 M KOH solution. Reproduced with permission from Ref. 86]. Copyright 2016. Royal Society of Chemistry.

Khiarak et al. prepared a CoNi MOFon incredibly porous conductive graphene (PCG) for HER by using the high-quality template-assisted chemical vapour deposition (CVD) graphene and solvothermal production deposition of bimetallic CoNi metal-organic framework (CoNi-MOF-PCG) particles over a graphene substrate. 87 The electrocatalyst shows excellent results in a highly alkaline solution (1 M KOH), demonstrating a 12-fold increase in Electrochemical Surface Area (ECSA) and an active catalytic site for HER exhibiting an overpotential of 265 mV and improved rate of diffusion and charge transfer efficiency. Yan and colleagues created a hybrid composite that splits electrocatalytically by introducing a nickel organic framework onto reduced graphene oxide (Ni2P/rGO), allowing it to undergo a low-temperature phosphorization procedure, as shown in Figure 8a. 88 The electrocatalyst shows excellent results in a highly alkaline solution (1 M KOH) with the current-time curve and Tafel slope (Figure 8c) of 58 mV dec−1 with LSV polarization curves (Figure 8c). The composite provides improved HER catalytic capabilities with an overpotential of 142 mV, a greater surface area and an average particle size of roughly 2.6 nm.

![Figure 8:

Synthesis, structural analysis, and HER performance of Ni2P/rGO composite catalyst. (a) Graphical illustration for the synthesis of Ni2P/rGO; (b) Tafel slopes of HER; (c) polarization curves of Ni2P/rGO in 1.0 M KOH. Reproduced with permission from Ref. 88]. Copyright 2018. The Royal Society of Chemistry.](/document/doi/10.1515/revic-2024-0098/asset/graphic/j_revic-2024-0098_fig_008.jpg)

Synthesis, structural analysis, and HER performance of Ni2P/rGO composite catalyst. (a) Graphical illustration for the synthesis of Ni2P/rGO; (b) Tafel slopes of HER; (c) polarization curves of Ni2P/rGO in 1.0 M KOH. Reproduced with permission from Ref. 88]. Copyright 2018. The Royal Society of Chemistry.

Additionally, Gopi et al. developed the bimetallic VeNixFeyMOF/GO composite using solvothermal synthesis to create a carbon-supported architecture. 89 The reduced Rct value of 12 Ω and the tafel slope of 150 mV/dec indicated a high-speed transfer of electrons for hydrogen generation with an overpotential of 90 mV in a very acidic solution. Makhafola et al. prepared an effective electrocatalyst Pd@GO/MOF nanocomposite by loading the MOF and Pd@GO through an impregnation process. The stability was enhanced because the Pd interacted with GO and MOF, limiting the loss of those functional groups. The turn over frequency (TOF) value of 4.71 mol·H2 s−1 and a Tafel slope of 169 mV dec−1 exhibits that the Pd@GO/MOF application performance was discovered as an H2-evolving catalyst, demonstrating the composite’s outstanding conductivity that results from the presence of Pd@GO. 90 Another unique electrocatalytic composite can be found in Makhafola’s study. Specifically, the authors prepared GO/Cu-MOF composite for hydrogen production via the impregnation method, as shown in Figure 9a. 91 The morphological structure of GO/Cu-MOF composites was present in SEM and TEM images (Figure 9b–d). The TOF value (4.57 mol·H2 s−1) with the concentration of 0.3 M H2SO4 resulted in higher Hydrogen generation. The synergistic interaction between GO with the MOF crystals is responsible for the enhanced performance in HER studies and better log current pH with the Pourbaix diagram reported after GO was added, as depicted in Figure 9e and f.

![Figure 9:

Synthesis, structural analysis, and HER performance of GO/Cu-MOF composite catalyst. (a) Graphical illustration for GO/Cu-MOF synthesis route; (b–d) SEM and TEM images of catalyst; (e) log current of pH of solution, and (f) Pourbaix diagram of HER. Reproduced with permission from Ref. 91]. Copyright 2020. Electrochemical Science Group.](/document/doi/10.1515/revic-2024-0098/asset/graphic/j_revic-2024-0098_fig_009.jpg)

Synthesis, structural analysis, and HER performance of GO/Cu-MOF composite catalyst. (a) Graphical illustration for GO/Cu-MOF synthesis route; (b–d) SEM and TEM images of catalyst; (e) log current of pH of solution, and (f) Pourbaix diagram of HER. Reproduced with permission from Ref. 91]. Copyright 2020. Electrochemical Science Group.

3.4 MOFs and MOF-GO electrocatalysts for OER

Depending on unique approaches, several metal-dependent electrocatalysts were reported for electrochemical water splitting for oxygen evolution reactions, as listed in Table 2. Jiang et al. presented electrodeposited nickel-phosphorus (Ni–P) film, which exhibits remarkable progress for OER with an overpotential value of 344 mV. 75 The increased OER performance was attributed to the high catalytic activity of Ni–P film. Maity et al. introduced the nanoporous bimetallic phosphide (Ni0.2Co0.8P) catalyst with a 3D network structure and an enhanced surface area. 92 The resulting catalyst Ni0.2Co0.8P displays exceptional performance under alkaline OER conditions having an overpotential of 230 mV and a Tafel slope of 44 mV dec−1. These results revealed that there is a synergetic effect between d and p bands with rapid mass transfer properties by providing a three-dimensional network morphology of Ni0.2Co0.8P catalyst. Ni exhibits highly efficient, durable and cost-effective electrocatalysts that take part for the large-scale water splitting. Wang et al. presented tricomponent metal phosphide with a hollow structure synthesized from cobalt-containing MOFs (ZIF-67) followed by high-temperature reduction at a lower overpotential value of 329 mV. 93 The greatly enhanced water oxidation performance presents it as a versatile approach to utilize MOFs as a precursor to synthesize highly effective water-splitting electrocatalysts. Xu et al. used a simple hydrothermal surfactant-assisted method to synthesize an ultrathin two-dimensional cobalt metal-organic framework nanosheets [Co2(OH)2BDC] (Figure 10a). The resultant 2D Co-MOFs were applied as working electrode. The LSV curves of electrodes observed at a slow scan rate of 5 mV s−1 are shown in Figure 10b. Moreover, the 2D Co-MOFs material shows a low overpotential of 263 mV at 10 mA cm−2 and a Tafel slope of 74 mV dec−1 in 1.0 M KOH (Figure 10c and d). 94 The superior catalytic kinetics, reflected by the LSV polarization curves and the Tafel slope of 74 mV dec⁻1, highlight the material’s ability to target more active sites, resulting in enhanced durability and improved OER performance.

Electrocatalytic O2 production by recent publications of MOFs/MOF-GO electrocatalysts.

| Catalysts | Electrolyte | Overpotential (mV) | Tafel slope (mV dec−1) | Stability | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ni–P | 1 M KOH | 344 | 49 | 24 h | 75 |

| Ni0.2Co0.8P | 0.1 M KOH | 230 | 44 | N/A | 92 |

| Ni/Fe(ZIF-67) | 1 M NaOH | 329 | 48.2 | 10 h | 93 |

| Co2(OH)2BDC | 1 M KOH | 263 | 74 | 12,000 s | 94 |

| Co3O4@Ni2P–CoP/NF | 1 M KOH | 298 | 75 | 40 h | 95 |

| NiFeZn-MOF | 1 M KOH | 350 | 51 | 120 h | 96 |

| NiCo-BTC-KB | 1 M KOH | 347 | 70 | 24 h | 97 |

| 2D MOF-Fe/Co | 1 M KOH | 238 | 52 | 50,000 s | 98 |

| Ni–Cu@Cu–Ni-MOF-74 | 1 M KOH | 624 | 98 | 30,000 s | 99 |

| Co/Ce-MOFs | 0.1 M KOH | 308 | 107 | 25 h | 100 |

| COP/rGO-400 | 1 M KOH | 66 | 340 | 22 h | 86 |

| Ni2P/rGO | 1 M KOH | 260 | 62 | 2,000 cycles | 88 |

| V-NixFey-MOF/GO | 1 M KOH | 210 | 97 | Over 20 h | 89 |

| Co BTC-rGO | 1 M KOH | 0.29 | 71.4 | 3,600 s | 101 |

| Fe–Ni–P/rGO | 1 M KOH | 63 | 240 | 5 h | 102 |

| R@FeNi | 1 M KOH | 264 | 62 | Over 1,000 cycles | 103 |

| 3D Gr/Ni-MOF | 0.1 M KOH | 370 | 93 | 20 h | 104 |

![Figure 10:

Synthesis, structural characterization, and OER performance of ultrathin 2D Co-MOF nanosheets. (a) Graphical illustration of ultrathin 2D Co-MOF synthesis; (b) LSV curve; (c) Tafel slopes; (d) durability test for 1,000 cycles, and (e) Chronoamperometric testing of ultrathin 2D Co-MOF at 1.0 M KOH electrolyte. Reproduced with permission from Ref. 94]. Copyright 2018. Royal Society of Chemistry.](/document/doi/10.1515/revic-2024-0098/asset/graphic/j_revic-2024-0098_fig_010.jpg)

Synthesis, structural characterization, and OER performance of ultrathin 2D Co-MOF nanosheets. (a) Graphical illustration of ultrathin 2D Co-MOF synthesis; (b) LSV curve; (c) Tafel slopes; (d) durability test for 1,000 cycles, and (e) Chronoamperometric testing of ultrathin 2D Co-MOF at 1.0 M KOH electrolyte. Reproduced with permission from Ref. 94]. Copyright 2018. Royal Society of Chemistry.

Besides, mixing MOF with heterometallic atoms resulted in exceptional catalysts through phosphidation, carbonation and oxidation. Guo et al. developed a well-controlled Co3O4@Ni2P–CoP/NF bimetallic electrocatalyst through phosphating and carbonation of Co3O4 nanowires by template-directed construction of MOF arrays. 95 The resulting hierarchal Co3O4@Ni2P–CoP/NF nanomaterials exhibit exceptional OER electrocatalytic properties at an overpotential of 298 mV and the long-term durability of 40 h in 1 M KOH solution, suggesting high catalytic bimetallic electrocatalyst for water oxidation reaction, high porosity, and N, P-codoping. Wei et al. introduced ultrathin NiFeZn-MOF nanosheet fabrication on nickel foams for electrocatalytic production of oxygen with a durability of 120 h. 96 The recorded BET surface area of 227.1 m2 g−1 indicates the relative gap between the pores on the surface of the catalyst material, exhibiting the Tafel slope value of 51 mV dec−1 for better OER electrochemical performance and water decomposition. Sondermann et al. synthesized the combination of NiCo-BTC (1,3,5-benzene dicarboxylate) MOF with highly conductive carbon material ketjenblack (KB) through a solvothermal reaction. 97 The overpotential value shifts from 366 mV to 347 mV when KB is linked with NiCo-BTC (MOF), exhibiting higher rate kinetics of OER catalyst. Ge et al. demonstrated the facile 2D bimetallic MOF-Fe/Co synthesis (Figure 11a) via stirring with a significant overpotential value of 238 mV, which exhibits that the addition of Fe in 2D MOF-Co modifies Co electronic states and reduces the free energy of oxygen evolution reaction for using on industrial level. 98 The energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) elemental mapping (Figure 11b) and the LSV polarization curves are shown in Figure 11c. The lower charge transfer resistance (Rct) value of 3.3 Ω of the catalyst between the electrode and electrolyte exhibited charge transfer on the catalyst’s surface.

![Figure 11:

Synthesis, structural characterization, and OER performance of ultrathin 2D MOF-Fe/Co ultrathin nanosheets. (a) The graphical representation of ultrathin 2D MOF-Fe/Co synthesis route; (b) EDS elemental mapping and, (c) LSV polarization curve of 2D MOF-Fe/Co nanosheets. Reproduced with permission from Ref. 98]. Copyright 2021. Wiley.](/document/doi/10.1515/revic-2024-0098/asset/graphic/j_revic-2024-0098_fig_011.jpg)

Synthesis, structural characterization, and OER performance of ultrathin 2D MOF-Fe/Co ultrathin nanosheets. (a) The graphical representation of ultrathin 2D MOF-Fe/Co synthesis route; (b) EDS elemental mapping and, (c) LSV polarization curve of 2D MOF-Fe/Co nanosheets. Reproduced with permission from Ref. 98]. Copyright 2021. Wiley.

Ma et al. reported the in-situ synthesis of bimetallic nanoparticles encapsulated within metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) by fabricating nanoparticles of Ni–Cu alloy. 99 The Ni–Cu@Cu–Ni-MOF-74 exhibits 71.18 times higher OER activity at overpotential 624 mV and 98 mV dec−1, which results in an enhancement ofECSA and more catalytic active sites. Ai et al. presented an imperative approach for the synthesis of cobalt/cerium-based metal-organic frameworks (Co/Ce-based MOFs) via a simple solvothermal method which promotes OER electrocatalysis due to the presence of catalytically inert Ce-BTC as an OER promoter, as visualized in Figure 12a. 100 The LSV polarization curves and comparisons of OER current densities are presented in Figure 12b and c. The synthesized Co/Ce-based MOFs exhibit remarkable OER activity with a low overpotential value of 308 mV and prolonged electrocatalyst stability over 25 h compared to commercial catalysts.

![Figure 12:

Synthesis, structural characterization, and OER performance of Co/Ce-based MOFs. (a) The schematic representation for crystal growth of Co/Ce-based MOFs; (b) polarization curves and (c) comparisons of OER current densities and enhancement factor for Co/Ce-based MOFs. Reproduced with permission from Ref. 100]. Copyright 2022. Elsevier.](/document/doi/10.1515/revic-2024-0098/asset/graphic/j_revic-2024-0098_fig_012.jpg)

Synthesis, structural characterization, and OER performance of Co/Ce-based MOFs. (a) The schematic representation for crystal growth of Co/Ce-based MOFs; (b) polarization curves and (c) comparisons of OER current densities and enhancement factor for Co/Ce-based MOFs. Reproduced with permission from Ref. 100]. Copyright 2022. Elsevier.

Numerous investigations have highlighted (Table 2) that the efficiency of these electrocatalysts has remarkable intrinsic properties when graphene or reduced graphene oxides are templated to emphasize their potential. The excellent OER performance of a layered metal-organic framework CoP/reduced graphene oxide composite (COP/rGO-400) at an overpotential of 340 mV exhibits a stable electron transfer process displayed superior activity to that of the integrated Pt/C and IrO2 catalyst couple. Additionally, COP/rGO-400 was reported for the very first time as a bifunctional catalyst due to the sandwiched layer of reduced graphene oxide. 86 Yaqoob et al. investigated the OER electrocatalytic maintenance of cobalt benzene tricarboxylic acid-based metal-organic frameworks with reduced graphene oxide (Co BTC-rGO) in alkaline conditions by solvothermal methods. 101 The overpotential of 290 mV exhibits a Tafel slope value of 71.4 mV dec−1 due to the π–π interaction between the MOF and reduced graphene oxide. This results in long-term stability and excellent OER catalytic activity. Yan et al. synthesized an electrocatalytic hybrid composite through the implantation of a nickel organic framework on graphene oxide (Ni2P/rGO) with an enhanced oxygen evolution reaction. 88 This resulted in an overpotential of 260 mV for OER and dispersion of ultra-small Ni2P active sites adjacent to graphene oxide. Gopi et al. synthesized bifunctional water-splitting electrocatalysts from a bimetallic V-doped NixFeyMOF@Graphene oxide composite, which was created by solvothermal synthesis on a carbon-supported architecture, as presented in Figure 13a. 89 Furthermore, our results showed that vanadium doping might work well with Ni/Fe to produce a modest overpotential for OER of 210 mV at 10 mA cm−2. The morphological structures in TEM images (Figure 13b–d) along with the LSV curves (Figure 13e) and Tafel slopes comparisons with overpotential are shown in Figure 13g. The positive shift from Ni2+ to Ni3+ in the catalyst V-NixFey-MOF/GO resulted in the smallest Tafel slope of 97 mV/dec, indicating the faster flow of electrons for the oxygen evolution reaction.

![Figure 13:

Synthesis, structural characterization, and OER performance of V-NixFey-MOF/GO catalyst. (a) Synergistic route illustration to synthesize V-NixFey-MOF/GO catalyst; (b–d) TEM images; (e) LSV curve and (f) Tafel slopes; (g) Tafel slope and overpotential comparison for the synthesized catalyst with different ratio of Ni and Fe metal. Reproduced with permission from Ref. 89]. Copyright 2022. Elsevier.](/document/doi/10.1515/revic-2024-0098/asset/graphic/j_revic-2024-0098_fig_013.jpg)

Synthesis, structural characterization, and OER performance of V-NixFey-MOF/GO catalyst. (a) Synergistic route illustration to synthesize V-NixFey-MOF/GO catalyst; (b–d) TEM images; (e) LSV curve and (f) Tafel slopes; (g) Tafel slope and overpotential comparison for the synthesized catalyst with different ratio of Ni and Fe metal. Reproduced with permission from Ref. 89]. Copyright 2022. Elsevier.

Abazari et al. reported a cost-effective Fe–Ni–P/rGO composite through the solvothermal method in an alkaline medium, revealing a lower overpotential of 264 mV with a Tafel slope of 62 mV dec−1. 102 The development of a bimetallic FeNi catalyst facilitates (–OH) transfer through its non-porous structure and exhibits amazing OER performance. Fang et al. used a novel rational strategy to synthesize a bimetallic iron-nickel phosphide reduced graphene oxide (R@FeNi) composite by pyrolysis and subsequent phosphidation process, as shown in Figure 14a. 103 The catalyst presents superior OER activity by achieving a low overpotential value of 240 mV at a current density of 10 mA cm−2. The morphological structures in the form of TEM images and water contact angle of the R@FeNi composite is shown in Figure 14b and c. Additionally, the R@FeNi composite exhibits exceptional OER kinetics with a LSV curves and Tafel slope (63 mV dec−1) compared to other non-noble MOFs due to the high conductance of the reduced graphene oxide (Figure 14d and e). Xie et al. reported a novel three-dimensional graphene oxide nickel-based metal-organic framework (3D Gr/Ni-MOF) composite synthesized by combining freeze drying and ultrasonic technique. 104 The OER electrochemical performance of 3D Gr/Ni-MOF catalyst exhibits a lower overpotential of 370 mV due to exposed Ni active sites with enhanced charge and mass transfer, resulting in improved OER performance.

![Figure 14:

Synthesis, structural characterization, and OER performance of R@FeNi composite. (a) Graphical illustration for preparation of R@FeNi composite; (b) TEM images; (c) water contact angle of R@FeNi and, (d) LSV curves and (e) Tafel slopes for OER performance of R@FeNi composite Reproduced with permission from Ref. 103]. Copyright 2022. American Chemical Society.](/document/doi/10.1515/revic-2024-0098/asset/graphic/j_revic-2024-0098_fig_014.jpg)

Synthesis, structural characterization, and OER performance of R@FeNi composite. (a) Graphical illustration for preparation of R@FeNi composite; (b) TEM images; (c) water contact angle of R@FeNi and, (d) LSV curves and (e) Tafel slopes for OER performance of R@FeNi composite Reproduced with permission from Ref. 103]. Copyright 2022. American Chemical Society.

4 Conclusion and future perspectives

Nanotechnology offers diverse applications in green energy generation and storage, including supercapacitors, fuel cells, batteries, biosensors, and water splitting for hydrogen storage. Nanomaterials hold substantial promise in green hydrogen production through innovative composite synthesis for efficient energy utilization and enhanced structural properties. Researchers have advanced hydrogen storage by leveraging remarkable electrocatalysts, photocatalysts, and photo-electrocatalysts. This review focuses on recent developments in the use of MOF and MOF-GO-based electrocatalysts and their applications in electrocatalysis for the OER and HER.

MOF-GO-based electrocatalysts are highly conductive, stable, tunable, and multifunctional materials. They provide more active sites through graphene oxide sheets compared to traditional MOFs. Nanostructures of MOFs and MOF-GO-based materials have been synthesized by methods such as hydrothermal, solvothermal, in-situ growth, and microwave-assisted techniques. These methods enhance electrocatalytic performance, including improved Tafel slope, stability, overpotential, surface area, current density, and charge transfer resistance, making them promising materials for overall water splitting.

Researchers are developing covalent organic frameworks (COFs) with improved characteristics for water splitting. While MOFs and MOF-GO-based materials demonstrate significant potential, they pose distinct future challenges alongside COFs to achieve a green, sustainable environment. The future perspectives of MOF and MOF-GO materials as electrocatalysts offer promising directions for enhancing efficiency and expanding applications.

Enhanced Conductivity: Future research should prioritize developing highly conductive MOFs by modifying their intrinsic structures or integrating conductive components.

Structural Stability: Developing robust MOFs and MOF-GO composites resistant to structural degradation during catalytic processes is essential.

Single-Atom Catalysts: Research into single-atom MOF-based catalysts can maximize catalytic activity by enhancing the exposure of active sites.

Computational Integration: Utilizing computational techniques like quantum chemistry and machine learning will be invaluable in designing and optimizing MOF and MOF-GO materials.

Application Expansion: Beyond electrocatalysis, MOFs and COFs offer opportunities in fields like CO₂ reduction and artificial photosynthesis.

Electrical Conductivity: MOFs and their derivatives generally have limited electrical conductivity compared to COFs, which exhibit semiconducting and metallic properties.

In summary, developing cost-effective electrocatalysts is essential for addressing environmental challenges, including water splitting, batteries, supercapacitors, and energy storage. The primary objective of this review is to assess recent advancements in MOF and MOF-GO materials for electrocatalytic water splitting.

Funding source: Deanship of Research and Graduate Studies at King Khalid University

Award Identifier / Grant number: RGP2/169/45

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Research and Graduate Studies at King Khalid University for funding this work through Large Research Project under grant number RGP2/169/45.

-

Research ethics: Not applicable.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Author contributions: All the authors contributed equally to the current research. The authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Conflict of interest: The author states no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: The authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Research and Graduate Studies at King Khalid University for funding this work through Large Research Project under grant number RGP2/169/45.

-

Data availability: None declared.

References

1. Zhang, M.; Chang, S.; Chen, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Xue, H.; Deng, Y.; Jiang, Y. Regulating Electron-Spin State Enables Enhanced Electrocatalytic Water Splitting Properties in Bimetallic Sulfides. Fuel 2024, 362, 130941; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2024.130941.Search in Google Scholar

2. Ahmed, I.; Biswas, R.; Iqbal, M.; Roy, A.; Haldar, K. K. NiS/MoS2 Anchored Multiwall Carbon Nanotube Electrocatalyst for Hydrogen Generation and Energy Storage Applications. ChemNanoMat 2023, 9 (6), e202200550; https://doi.org/10.1002/cnma.202200550.Search in Google Scholar

3. Li, Y.; Miao, Y. C.; Yang, C.; Chang, Y. X.; Su, Y.; Yan, H.; Xu, S. Ir Nanodots Decorated Ni3Fe Nanoparticles for Boosting Electrocatalytic Water Splitting. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 451, 138548; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2022.138548.Search in Google Scholar

4. Spătaru, T.; Preda, L.; Osiceanu, P.; Munteanu, C.; Anastasescu, M.; Marcu, M.; Spătaru, N. Role of Surfactant-Mediated Electrodeposited Titanium Oxide Substrate in Improving Electrocatalytic Features of Supported Platinum Particles. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2014, 288, 660–665; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2013.10.092.Search in Google Scholar

5. Bai, J.; Xing, S. H.; Zhu, Y. Y.; Jiang, J. X.; Zeng, J. H.; Chen, Y. Polyallylamine-Rh Nanosheet Nanoassemblies− Carbon Nanotubes Organic-Inorganic Nanohybrids: A Electrocatalyst Superior to Pt for the Hydrogen Evolution Reaction. J. Power Sources 2018, 385, 32–38; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpowsour.2018.03.022.Search in Google Scholar

6. Rutkowska, I. A.; Zoladek, S.; Kulesza, P. J. Polyoxometallate-assisted Integration of Nanostructures of Au and ZrO2 to Form Supports for Electrocatalytic PtRu Nanoparticles: Enhancement of Their Activity toward Oxidation of Ethanol. Electrochim. Acta 2015, 162, 215–223; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electacta.2014.12.098.Search in Google Scholar

7. Li, C.; Baek, J.-B. Recent Advances in Noble Metal (Pt, Ru, and Ir)-Based Electrocatalysts for Efficient Hydrogen Evolution Reaction. ACS Omega 2019, 5 (1), 31–40; https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.9b03550.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

8. Li, Y.; Zhou, L.; Guo, S. Noble Metal-free Electrocatalytic Materials for Water Splitting in Alkaline Electrolyte. EnergyChem 2021, 3 (2), 100053; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enchem.2021.100053.Search in Google Scholar

9. Li, A.; Sun, Y.; Yao, T.; Han, H. Earth‐abundant Transition‐metal‐based Electrocatalysts for Water Electrolysis to Produce Renewable Hydrogen. Chem. Eur. J. 2018, 24 (69), 18334–18355; https://doi.org/10.1002/chem.201803749.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

10. Qin, Y.; Hao, M.; Li, Z. Metal–organic Frameworks for Photocatalysis. In Interface Science and Technology; Elsevier, 2020; pp 541–579.10.1016/B978-0-08-102890-2.00017-8Search in Google Scholar

11. Sanad, M. F.; Sreenivasan, S. T. Metal-organic Framework in Fuel Cell Technology: Fundamentals and Application. In Electrochemical Applications of Metal-Organic Frameworks; Elsevier, 2022; pp 135–189.10.1016/B978-0-323-90784-2.00001-0Search in Google Scholar

12. Ren, Y.; Chia, G. H.; Gao, Z. Metal–organic Frameworks in Fuel Cell Technologies. Nano Today 2013, 8 (6), 577–597; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nantod.2013.11.004.Search in Google Scholar

13. Sahoo, R.; Ghosh, S.; Chand, S.; Chand Pal, S.; Kuila, T.; Das, M. C. Highly Scalable and pH Stable 2D Ni-MOF-Based Composites for High Performance Supercapacitor. Compos. B Eng. 2022, 245, 110174; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compositesb.2022.110174.Search in Google Scholar

14. Zhang, J.; Huang, J.; Wang, L.; Sun, P.; Wang, P.; Yao, Z.; Yang, Y. Coupling Bimetallic NiMn-MOF Nanosheets on NiCo2O4 Nanowire Arrays with Boosted Electrochemical Performance for Hybrid Supercapacitor. Mater. Res. Bull. 2022, 149, 111707; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.materresbull.2021.111707.Search in Google Scholar

15. Xu, W.; Wang, L. H.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Y. Flexible Carbon Membrane Supercapacitor Based on γ-cyclodextrin-MOF. Mater. Today Chem. 2022, 24, 100896; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mtchem.2022.100896.Search in Google Scholar

16. Zhao, W.; Zeng, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Wu, X. Recent Advances in Metal-Organic Framework-Based Electrode Materials for Supercapacitors: A Review. J. Energy Storage 2023, 62, 106934; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.est.2023.106934.Search in Google Scholar

17. Tao, Y.; Xu, H. A Critical Review on Potential Applications of Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) in Adsorptive Carbon Capture Technologies. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2023, 236, 121504; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2023.121504.Search in Google Scholar

18. Mohan, B.; Virender; Kadiyan, R.; Kumar, S.; Gupta, V.; Parshad, B.; Solovev, A. A.; Pombeiro, A. J.; Kumar, K.; Sharma, P. K. Carbon Dioxide Capturing Activities of Porous Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs). Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2023, 366, 112932; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micromeso.2023.112932.Search in Google Scholar

19. Daud, N. CO2 Adsorption Performance of AC and Zn-MOF for the Use of Carbon Capture and Sequestration (CCS). Mater. Today Proc. 2023; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2023.03.231.Search in Google Scholar

20. Xv, J.; Zhang, Z.; Pang, S.; Jia, J.; Geng, Z.; Wang, R.; Li, P.; Bilal, M.; Cui, J.; Jia, S. Accelerated CO2 Capture Using Immobilized Carbonic Anhydrase on Polyethyleneimine/dopamine Co-deposited MOFs. Biochem. Eng. J. 2022, 189, 108719; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bej.2022.108719.Search in Google Scholar

21. Gaikwad, S.; Han, S. Shaping Metal-Organic Framework (MOF) with Activated Carbon and Silica Powder Materials for CO2 Capture. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11 (2), 109593; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2023.109593.Search in Google Scholar

22. Do, H. H.; Nguyen, T. H. C.; Nguyen, T. V.; Xia, C.; Nguyen, D. L. T.; Raizada, P.; Singh, P.; Nguyen, V. H.; Ahn, S. H.; Kim, S. Y.; Le, Q. V. Metal-organic-framework Based Catalyst for Hydrogen Production: Progress and Perspectives. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47 (88), 37552–37568; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2022.01.080.Search in Google Scholar

23. Cui, H.; Gong, L.; Wang, J.; Dong, L.; Zhang, J.; Mu, Y.; Yang, B.; Wang, M.; Gu, Y.; Li, H. POM@ TM-MOFs Prism-Structures as a Superior Bifunctional Electrocatalyst for Overall Water Splitting. J. Solid State Chem. 2024, 331, 124550; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jssc.2024.124550.Search in Google Scholar

24. Zhang, Y.; Zheng, X.; Guo, X.; Zhang, J.; Yuan, A.; Du, Y.; Gao, F. Design of Modified MOFs Electrocatalysts for Water Splitting: High Current Density Operation and Long-Term Stability. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2023, 336, 122891; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apcatb.2023.122891.Search in Google Scholar

25. Cui, X.; Lin, L.; Xu, T.; Liu, J.; Tang, M.; Wang, Z. In-situ Fabrication of MOF@ CoP Hybrid Bifunctional Electrocatalytic Nanofilm on Carbon Fibrous Membrane for Efficient Overall Water Splitting. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 49, 1446–1457; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2023.10.066.Search in Google Scholar

26. Liu, T.; Guan, Y.; Wu, Y.; Chu, X.; Liu, B.; Zhang, N.; Liu, C.; Jiang, W.; Che, G. Ru Nanoparticles Immobilized on Self-Supporting Porphyrinic MOF/nickel Foam Electrode for Efficient Overall Water Splitting. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 57, 408–419; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2024.01.026.Search in Google Scholar

27. Chen, C.; Li, J.; Lv, Z.; Wang, M.; Dang, J. Recent Strategies to Improve the Catalytic Activity of Pristine MOFs and Their Derived Catalysts in Electrochemical Water Splitting. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48 (78), 30435–30463; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2023.04.241.Search in Google Scholar

28. Liu, Y.; Yang, X.; Guo, R.; Yao, Z. Engineering MOF-Based Nanocatalysts for Boosting Electrocatalytic Water Splitting. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47 (92), 39001–39017; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2022.09.077.Search in Google Scholar

29. Zhou, P.; Lv, J.; Huang, X.; Lu, Y.; Wang, G. Strategies for Enhancing the Catalytic Activity and Electronic Conductivity of MOFs-Based Electrocatalysts. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2023, 478, 214969; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccr.2022.214969.Search in Google Scholar

30. Lingamdinne, L. P.; Koduru, J. R.; Karri, R. R. A Comprehensive Review of Applications of Magnetic Graphene Oxide Based Nanocomposites for Sustainable Water Purification. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 231, 622–634; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2018.10.063.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

31. Singh, B.; Gupta, H. Metal–organic Frameworks (MOFs) for Hybrid Water Electrolysis: Structure–Property–Performance Correlation. Chem. Commun. 2024, 60 (62), 8020–8038; https://doi.org/10.1039/d4cc02729a.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

32. Hanan, A.; Lakhan, M. N.; Bibi, F.; Khan, A.; Soomro, I. A.; Hussain, A.; Aftab, U. MOFs Coupled Transition Metals, Graphene, and MXenes: Emerging Electrocatalysts for Hydrogen Evolution Reaction. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 482, 148776; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2024.148776.Search in Google Scholar

33. Jia, L.; Wagner, P.; Chen, J. Electrocatalyst Derived from NiCu–MOF Arrays on Graphene Oxide Modified Carbon Cloth for Water Splitting. Inorganics 2022, 10 (4), 53; https://doi.org/10.3390/inorganics10040053.Search in Google Scholar

34. Nazir, M. A.; Javed, M. S.; Islam, M.; Assiri, M. A.; Hassan, A. M.; Jamshaid, M.; Najam, T.; Shah, S. S. A.; Rehman, A. u. MOF@ Graphene Nanocomposites for Energy and Environment Applications. Compos. Commun. 2023, 45, 101783; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coco.2023.101783.Search in Google Scholar

35. Li, J.; Zhao, Z.; Ma, Y.; Qu, Y. Graphene and Their Hybrid Electrocatalysts for Water Splitting. ChemCatChem 2017, 9 (9), 1554–1568; https://doi.org/10.1002/cctc.201700175.Search in Google Scholar

36. Banoth, P.; Kandula, C.; Kollu, P. Introduction to Electrocatalysts. In Noble Metal-Free Electrocatalysts: New Trends in Electrocatalysts for Energy Applications; ACS Publications, Vol. 2, 2022; pp 1–37.10.1021/bk-2022-1432.ch001Search in Google Scholar

37. Munir, S.; Baig, M. M.; Zulfiqar, S.; Saif, M. S.; Agboola, P. O.; Warsi, M. F.; Shakir, I. Synthesis of 2D Material Based Bi2O3/MXene Nanohybrids and Their Applications for the Removal of Industrial Effluents. Ceram. Int. 2022, 48 (15), 21717–21730; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2022.04.148.Search in Google Scholar

38. Sinar Mashuri, S. I.; Ibrahim, M. L.; Kasim, M. F.; Mastuli, M. S.; Rashid, U.; Abdullah, A. H.; Islam, A.; Asikin Mijan, N.; Tan, Y. H.; Mansir, N.; Mohd Kaus, N. H.; Yun Hin, T. Y. Photocatalysis for Organic Wastewater Treatment: From the Basis to Current Challenges for Society. Catalysts 2020, 10 (11), 1260; https://doi.org/10.3390/catal10111260.Search in Google Scholar

39. Jiang, Y.; Lu, Y. J. N. Designing Transition-Metal-Boride-Based Electrocatalysts for Applications in Electrochemical Water Splitting. Nanoscale 2020, 12 (17), 9327–9351; https://doi.org/10.1039/d0nr01279c.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

40. Plevova, M.; Hnat, J.; Bouzek, K. Electrocatalysts for the Oxygen Evolution Reaction in Alkaline and Neutral Media. A Comparative Review. J. Power Sources 2021, 507, 230072; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpowsour.2021.230072.Search in Google Scholar

41. Su, L.; Zhang, S.; Wu, H.; Zhou, S.; Cui, C.; Pang, H. Mechanism Insights and Design Strategies for Metal-Organic Framework-Based Alkaline Hydrogen Evolution Reaction Electrocatalysts. Nano Energy 2024, 130, 110177; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nanoen.2024.110177.Search in Google Scholar

42. Biswas, R.; Dastider, S. G.; Ahmed, I.; Barua, S.; Mondal, K.; Haldar, K. K. Unraveling the Role of Orbital Interaction in the Electrochemical HER of the Trimetallic AgAuCu Nanobowl Catalyst. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2023, 14 (13), 3146–3151; https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpclett.3c00011.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

43. Yu, Z. Y.; Duan, Y.; Feng, X.; Yu, X.; Gao, M.; Yu, S. Clean and Affordable Hydrogen Fuel from Alkaline Water Splitting: Past, Recent Progress, and Future Prospects. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33 (31), 2007100; https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.202007100.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

44. Wang, Y. Z.; Yang, M.; Ding, Y.; Yu, L. Recent Advances in Complex Hollow Electrocatalysts for Water Splitting. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32 (6), 2108681; https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.202108681.Search in Google Scholar

45. Bockris, J. O. ’M. The Origin of Ideas on a Hydrogen Economy and its Solution to the Decay of the Environment. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2002, 27 (7–8), 731–740; https://doi.org/10.1016/s0360-3199(01)00154-9.Search in Google Scholar

46. Marbán, G.; Valdés-Solís, T. Towards the Hydrogen Economy? Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2007, 32 (12), 1625–1637; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2006.12.017.Search in Google Scholar

47. Barreto, L.; Makihira, A.; Riahi, K. The Hydrogen Economy in the 21st Century: A Sustainable Development Scenario. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2003, 28 (3), 267–284; https://doi.org/10.1016/s0360-3199(02)00074-5.Search in Google Scholar

48. Abbasi, T.; Abbasi, S. Renewable’ Hydrogen: Prospects and Challenges. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2011, 15 (6), 3034–3040; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2011.02.026.Search in Google Scholar

49. Marini, S.; Salvi, P.; Nelli, P.; Pesenti, R.; Villa, M.; Berrettoni, M.; Zangari, G.; Kiros, Y. Advanced Alkaline Water Electrolysis. Electrochim. Acta 2012, 82, 384–391; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electacta.2012.05.011.Search in Google Scholar

50. Morales-Guio, C. G.; Hu, X. Amorphous Molybdenum Sulfides as Hydrogen Evolution Catalysts. Acc. Chem. Res. 2014, 47 (8), 2671–2681; https://doi.org/10.1021/ar5002022.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

51. Tong, Y.-J.; Yu, L. D.; Zheng, J.; Liu, G.; Ye, Y.; Huang, S.; Chen, G.; Yang, H.; Wen, C.; Wei, S.; Xu, J.; Zhu, F.; Pawliszyn, J.; Ouyang, G. Graphene Oxide-Supported Lanthanide Metal–Organic Frameworks with Boosted Stabilities and Detection Sensitivities. Anal. Chem. 2020, 92 (23), 15550–15557; https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.analchem.0c03562.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

52. Seh, Z. W.; Kibsgaard, J.; Dickens, C. F.; Chorkendorff, I.; Nørskov, J. K.; Jaramillo, T. F. Combining Theory and Experiment in Electrocatalysis: Insights into Materials Design. Science 2017, 355 (6321), eaad4998; https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aad4998.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

53. Hu, L.; Xiong, T.; Liu, R.; Hu, Y.; Mao, Y.; Balogun, M. J. T.; Tong, Y. Co3O4@ Cu‐Based Conductive Metal–Organic Framework Core–Shell Nanowire Electrocatalysts Enable Efficient Low‐Overall‐Potential Water Splitting. Chem. Eur. J. 2019, 25 (26), 6575–6583; https://doi.org/10.1002/chem.201900045.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

54. Patil, S. J.; Chodankar, N. R.; Hwang, S. K.; Shinde, P. A.; Seeta Rama Raju, G.; Shanmugam Ranjith, K.; Huh, Y. S.; Han, Y. K. Co-metal–organic Framework Derived CoSe2@ MoSe2 Core–Shell Structure on Carbon Cloth as an Efficient Bifunctional Catalyst for Overall Water Splitting. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 429, 132379; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2021.132379.Search in Google Scholar

55. Cai, G.; Zhang, W.; Jiao, L.; Yu, S. H.; Jiang, H. L. Template-directed Growth of Well-Aligned MOF Arrays and Derived Self-Supporting Electrodes for Water Splitting. Chem 2017, 2 (6), 791–802; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chempr.2017.04.016.Search in Google Scholar

56. Liang, X.; Zheng, B.; Chen, L.; Zhang, J.; Zhuang, Z.; Chen, B. MOF-Derived Formation of Ni2P–CoP Bimetallic Phosphides with Strong Interfacial Effect toward Electrocatalytic Water Splitting. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9 (27), 23222–23229; https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.7b06152.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

57. Ali, M.; Pervaiz, E.; Rabi, O. Enhancing the Overall Electrocatalytic Water-Splitting Efficiency of Mo2C Nanoparticles by Forming Hybrids with UiO-66 MOF. ACS Omega 2021, 6 (50), 34219–34228; https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.1c03115.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

58. Wang, X. L.; Dong, L.; Qiao, M.; Tang, Y.; Liu, J.; Li, Y.; Li, S.; Su, J.; Lan, Y. Exploring the Performance Improvement of the Oxygen Evolution Reaction in a Stable Bimetal–Organic Framework System. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 57 (31), 9660–9664; https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.201803587.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

59. Xie, M.; Ma, Y.; Lin, D.; Xu, C.; Xie, F.; Zeng, W. Bimetal–organic Framework MIL-53 (Co–fe): An Efficient and Robust Electrocatalyst for the Oxygen Evolution Reaction. Nanoscale 2020, 12 (1), 67–71; https://doi.org/10.1039/c9nr06883j.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

60. Shabbir, B.; Jabbour, K.; Manzoor, S.; Ashiq, M. F.; Fawy, K. F.; Ashiq, M. N. Solvothermally Designed Pr-MOF/Fe2O3 Based Nanocomposites for Efficient Electrocatalytic Water Splitting. Heliyon 2023, 9 (10); https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e20261.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

61. Wang, Q.; Yang, R.; Li, J.; Yang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Zhou, X.; Ma, G.; Ren, S. 2D DUT-8 (Ni)-Derived Ni@ C Nanosheets for Efficient Hydrogen Evolution. J. Solid State Electrochem. 2020, 24, 2461–2467; https://doi.org/10.1007/s10008-020-04743-7.Search in Google Scholar

62. Zhou, H.; Yu, F.; Zhu, Q.; Sun, J.; Qin, F.; Yu, L.; Bao, J.; Yu, Y.; Chen, S.; Ren, Z. Water Splitting by Electrolysis at High Current Densities under 1.6 Volts. Energy Environ. Sci. 2018, 11 (10), 2858–2864; https://doi.org/10.1039/c8ee00927a.Search in Google Scholar

63. Abbas, Z.; Hussain, N.; Ahmed, I.; Mobin, S. M. Cu-Metal Organic Framework Derived Multilevel Hierarchy (Cu/Cu X O@ NC) as a Bifunctional Electrode for High-Performance Supercapacitors and Oxygen Evolution Reaction. Inorg. Chem. 2023, 62 (23), 8835–8845; https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.inorgchem.3c00308.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

64. Wang, M.; Wang, Z.; Gong, X.; Guo, Z. The Intensification Technologies to Water Electrolysis for Hydrogen Production – A Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 29, 573–588; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2013.08.090.Search in Google Scholar

65. Guoqing, L.; Zhang, D.; Qiao, Q.; Yu, Y.; Peterson, D.; Zafar, A.; Kumar, R.; Curtarolo, S.; Hunte, F.; Shannon, S.; Zhu, Y.; Yang, W.; Cao, L. All the Catalytic Active Sites of MoS2 for Hydrogen Evolution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138 (51), 16632–16638; https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.6b05940.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

66. Xiao, X.; Tao, L.; Li, M.; Lv, X.; Huang, D.; Jiang, X.; Pan, H.; Wang, M.; Shen, Y. Electronic Modulation of Transition Metal Phosphide via Doping as Efficient and pH-Universal Electrocatalysts for Hydrogen Evolution Reaction. Chem. Sci. 2018, 9 (7), 1970–1975; https://doi.org/10.1039/c7sc04849a.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

67. Deeksha; Kour, P.; Ahmed, I.; Sunny; Sharma, S. K.; Yadav, K.; Mishra, Y. K. Transition Metal‐based Perovskite Oxides: Emerging Electrocatalysts for Oxygen Evolution Reaction. ChemCatChem 2023, 15 (6), e202300040; https://doi.org/10.1002/cctc.202300040.Search in Google Scholar

68. Yang, J.; Zhu, G.; Liu, Y.; Xia, J.; Ji, Z.; Shen, X.; Wu, S. Fe3O4‐decorated Co9S8 Nanoparticles In Situ Grown on Reduced Graphene Oxide: a New and Efficient Electrocatalyst for Oxygen Evolution Reaction. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2016, 26 (26), 4712–4721; https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.201600674.Search in Google Scholar

69. Wang, D.-Y.; Gong, M.; Chou, H. L.; Pan, C. J.; Chen, H. A.; Wu, Y.; Lin, M. C.; Guan, M.; Yang, J.; Chen, C. W.; Wang, Y. L.; Hwang, B. J.; Chen, C. C.; Dai, H. Highly Active and Stable Hybrid Catalyst of Cobalt-Doped FeS2 Nanosheets–Carbon Nanotubes for Hydrogen Evolution Reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137 (4), 1587–1592; https://doi.org/10.1021/ja511572q.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

70. Tian, X.; Luo, J.; Nan, H.; Zou, H.; Chen, R.; Shu, T.; Li, X.; Li, Y.; Song, H.; Liao, S.; Adzic, R. R. Transition Metal Nitride Coated with Atomic Layers of Pt as a Low-Cost, Highly Stable Electrocatalyst for the Oxygen Reduction Reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138 (5), 1575–1583; https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.5b11364.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

71. Lin, H.; Shi, Z.; He, S.; Yu, X.; Wang, S.; Gao, Q.; Tang, Y. Heteronanowires of MoC–Mo2C as Efficient Electrocatalysts for Hydrogen Evolution Reaction. Chem. Sci. 2016, 7 (5), 3399–3405; https://doi.org/10.1039/c6sc00077k.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

72. Rajasekaran, S.; Reghunath, B. S.; Devi, K. R. S.; Saravanakumar, B.; William, J. J.; Pinheiro, D. Bi Functional Manganese-Pyridine 2, 6 Dicarboxylic Acid Metal Organic Frameworks with Reduced Graphene Oxide as an Electroactive Material for Energy Storage and Water Splitting Applications. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2023, 170 (3), 036505; https://doi.org/10.1149/1945-7111/acbfe3.Search in Google Scholar

73. Qin, X.; Ola, O.; Zhao, J.; Yang, Z.; Tiwari, S. K.; Wang, N.; Zhu, Y. Recent Progress in Graphene-Based Electrocatalysts for Hydrogen Evolution Reaction. Nanomaterials 2022, 12 (11), 1806; https://doi.org/10.3390/nano12111806.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

74. Choi, S.; Kim, C.; Suh, J. M.; Jang, H. W. Reduced Graphene Oxide‐based Materials for Electrochemical Energy Conversion Reactions. Carbon Energy 2019, 1 (1), 85–108; https://doi.org/10.1002/cey2.13.Search in Google Scholar

75. Jiang, N.; You, B.; Sheng, M.; Sun, Y. Bifunctionality and Mechanism of Electrodeposited Nickel–Phosphorous Films for Efficient Overall Water Splitting. ChemCatChem 2016, 8 (1), 106–112; https://doi.org/10.1002/cctc.201501150.Search in Google Scholar

76. Zheng, Z.; Yu, L.; Gao, M.; Chen, X.; Zhou, W.; Ma, C.; Wu, L.; Zhu, J.; Meng, X.; Hu, J.; Tu, Y.; Wu, S.; Mao, J.; Tian, Z.; Deng, D. Boosting Hydrogen Evolution on MoS2 via Co-confining Selenium in Surface and Cobalt in Inner Layer. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11 (1), 3315; https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-17199-0.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

77. Dai, X.; Liu, M.; Li, Z.; Jin, A.; Ma, Y.; Huang, X.; Sun, H.; Wang, H.; Zhang, X. Molybdenum Polysulfide Anchored on Porous Zr-Metal Organic Framework to Enhance the Performance of Hydrogen Evolution Reaction. J. Phys. Chem. C 2016, 120 (23), 12539–12548; https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpcc.6b02818.Search in Google Scholar

78. Lin, J.; He, J.; Qi, F.; Zheng, B.; Wang, X.; Yu, B.; Zhou, K.; Zhang, W.; Li, Y.; Chen, Y. In-situ Selenization of Co-based Metal-Organic Frameworks as a Highly Efficient Electrocatalyst for Hydrogen Evolution Reaction. Electrochim. Acta 2017, 247, 258–264; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electacta.2017.06.179.Search in Google Scholar

79. Gao, M.-R.; Liang, J. X.; Zheng, Y. R.; Xu, Y. F.; Jiang, J.; Gao, Q.; Li, J.; Yu, S. H. An Efficient Molybdenum Disulfide/cobalt Diselenide Hybrid Catalyst for Electrochemical Hydrogen Generation. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6 (1), 5982; https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms6982.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

80. Li, Y.-S.; Yi, J. W.; Wei, J. H.; Wu, Y. P.; Li, B.; Liu, S.; Jiang, C.; Yu, H. G. Three 2D Polyhalogenated Co (II)-based MOFs: Syntheses, Crystal Structure and Electrocatalytic Hydrogen Evolution Reaction. J. Solid State Chem. 2020, 281, 121052; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jssc.2019.121052.Search in Google Scholar

81. Khrizanforova, V.; Shekurov, R.; Miluykov, V.; Khrizanforov, M.; Bon, V.; Kaskel, S.; Gubaidullin, A.; Sinyashin, O.; Budnikova, Y. 3D Ni and Co Redox-Active Metal–Organic Frameworks Based on Ferrocenyl Diphosphinate and 4, 4′-bipyridine Ligands as Efficient Electrocatalysts for the Hydrogen Evolution Reaction. Dalton Trans. 2020, 49 (9), 2794–2802; https://doi.org/10.1039/c9dt04834k.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

82. Shekurov, R.; Khrizanforova, V.; Gilmanova, L.; Khrizanforov, M.; Miluykov, V.; Kataeva, O.; Yamaleeva, Z.; Burganov, T.; Gerasimova, T.; Khamatgalimov, A.; Katsyuba, S.; Kovalenko, V.; Krupskaya, Y.; Kataev, V.; Büchner, B.; Bon, V.; Senkovska, I.; Kaskel, S.; Gubaidullin, A.; Sinyashin, O.; Budnikova, Y. Zn and Co Redox Active Coordination Polymers as Efficient Electrocatalysts. Dalton Trans. 2019, 48 (11), 3601–3609; https://doi.org/10.1039/c8dt04618b.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

83. Roy, S.; Huang, Z.; Bhunia, A.; Castner, A.; Gupta, A. K.; Zou, X.; Ott, S. Electrocatalytic Hydrogen Evolution from a Cobaloxime-Based Metal–Organic Framework Thin Film. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141 (40), 15942–15950; https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.9b07084.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

84. Patel, K. B.; Parmar, B.; Ravi, K.; Patidar, R.; Chaudhari, J. C.; Srivastava, D. N.; Bhadu, G. R. Metal-organic Framework Derived Core-Shell Nanoparticles as High Performance Bifunctional Electrocatalysts for HER and OER. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2023, 616, 156499; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2023.156499.Search in Google Scholar

85. Lin, J.; Wang, H.; Wang, C.; Guo, L.; Wang, Y. Ru-modulated Morphology and Electronic Structure of Nickel Organic Framework Bifunctional Electrocatalyst for Efficient Overall Water Splitting. Electrochim. Acta 2023, 470, 143300; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electacta.2023.143300.Search in Google Scholar

86. Jiao, L.; Zhou, Y.-X.; Jiang, H.-L. Metal–organic Framework-Based CoP/reduced Graphene Oxide: High-Performance Bifunctional Electrocatalyst for Overall Water Splitting. Chem. Sci. 2016, 7 (3), 1690–1695; https://doi.org/10.1039/c5sc04425a.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

87. Khiarak, B. N.; Hasanzadeh, M.; Simchi, A. Electrocatalytic Hydrogen Evolution Reaction on Graphene Supported Transition Metal-Organic Frameworks. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2021, 127, 108525; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inoche.2021.108525.Search in Google Scholar

88. Yan, L.; Jiang, H.; Xing, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, D.; Gu, X.; Dai, P.; Li, L.; Zhao, X. Nickel Metal–Organic Framework Implanted on Graphene and Incubated to Be Ultrasmall Nickel Phosphide Nanocrystals Acts as a Highly Efficient Water Splitting Electrocatalyst. J. Mater. Chem. A 2018, 6 (4), 1682–1691; https://doi.org/10.1039/c7ta10218f.Search in Google Scholar

89. Gopi, S.; Panda, A.; Ramu, A.; Theerthagiri, J.; Kim, H.; Yun, K. Bifunctional Electrocatalysts for Water Splitting from a Bimetallic (V Doped-NixFey) Metal–Organic Framework MOF@ Graphene Oxide Composite. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47 (100), 42122–42135; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2021.05.028.Search in Google Scholar