Abstract

The article provides a comprehensive analytical review of the literature on the use of nanoparticles in polymer composite materials aiming at an in-depth analysis of technological approaches to their integration and influence on the structural and functional properties of the polymer matrix. Particular attention is paid to the systematization of modern approaches to the classification of nanofillers by chemical composition and morphological features, as well as to the identification of effective ways to incorporate nanocomponents into the polymer base. This paper deals with the actual problems related to the uniform dispersion of nanoparticles, ensuring stability and effective interfacial interaction in polymer systems, which are critical for achieving the specified performance characteristics of materials. A comparative analysis of nanocomposites using carbon nanotubes, graphene, graphene oxide, nanodispersed silica, aerogels, and other nanostructured modifiers was performed. Optimal choice of nanofiller has been shown to significantly improve the mechanical, thermal, optical, electrical, conductive, and barrier characteristics of composites, which expands their application in fields such as biomedicine, electronics, energy, ecology, and construction. The technological challenges in the scaled-up production of polymer nanocomposites are generalized, and modern studies in nanochemistry and polymer synthesis are examined to outline the perspectives for their development.

1 Introduction

The use of nanoparticles in materials science significantly improves the properties of composites, such as strength, heat resistance, wear resistance, and durability, due to their high specific surface area and unique physical and chemical properties. The effectiveness depends on the technology of introduction into the matrix. Nanotechnology provides new opportunities for creating structural, protective, and functional fillers with unique characteristics. Two main areas are being developed in polymer materials science: the synthesis of polymers with specified molecular properties (linear, mesh, and block structures) and the creation of polymers capable of self-assembly due to intermolecular interactions that form supramolecular nanostructures (tubes, membranes, etc.).

The second area involves the creation of polymeric nanocomposite materials (PNCMs), compositions in which one of the phases (e.g., filler) has nanoscale characteristics (less than 100 nm). Fillers can be of carbon, metal, ceramic, or organic nature: graphene, fullerenes, nanotubes, nanofibers, nanosludge, metal and oxide nanoparticles, nanoclay, dendrimers, and polymeric nanofibers of natural origin. Due to the large specific surface area of nanoparticles and their unique physical and chemical characteristics (optical, electrical, and mechanical), even a small amount of them (1–5 %) can significantly improve the performance characteristics of the polymer matrix: strength, stiffness, thermal stability, wear resistance, barrier properties, hydrophobicity, etc.

The creation of PNCMs is accompanied by a number of technological challenges, among which the key ones are the aggregation of nanoparticles due to their high surface energy, the difficulty of their uniform distribution in the polymer volume, and the decrease in the rheological properties of the mixture (in particular, an increase in melt viscosity). Special methods of nanofiller surface functionalization, ultrasonic dispersion, mechanochemical activation, and surfactants are used to overcome these difficulties.

PNCMs are now widely used in the aerospace, automotive, electronics, medical, paint and varnish, and packaging industries. Their effective implementation depends on a deep understanding of the technology and properties of nanomaterials, including metal oxides (SiO2, TiO2, Al2O3), graphene, CNTs, and hybrid nanocomposites. In building materials, nanoadditives, particularly nanosilica, can modify the microstructure of cement stone, accelerate hydration, and increase the frost resistance of concrete, as experimentally confirmed in studies by Zhang et al. (2022) and Wang et al. (2024). Cement mixed with nanosilica (∼2 %) shows increased frost resistance under extreme weather (Wang et al. 2024). The introduction of cellulose nanofibrils reduces the weight loss of concrete after 150 freezing and thawing cycles by 73–83 % (Zhang et al. 2022). Multi-walled carbon nanotubes (CNTs) modified with polymer help to form an effective electrically conductive network in cement composites (Onthong et al. 2022).

Nanofillers increase the durability and thermal stability of polymer and metal matrices (Chan et al. 2021; Sabapathy et al. 2022; Tomin et al. 2024). Furthermore, CNTs, graphene, and other carbon nanostructures give composites functional properties, including electrical conductivity and barrier characteristics, by forming electrically conductive networks. For example, the electrical conductivity of polyurethane-based nanocomposites ranges from 10−3 to 102 S/m, making them suitable for sensors, antistatic coatings, and materials for protection against electromagnetic interference (Chang et al. 2020; Jafarzadeh et al. 2023).

The effectiveness depends on the methods of administration, stability, and distribution of nanoparticles. The inconsistency in the classification of nanomodifiers and their production technologies makes it difficult to standardize research and scale up production. The lack of a common terminology, differences in the definition of concentrations and methods of functionalization, as well as a lack of data on long-term properties and environmental impacts hinder the development of the industry. Systematization of these issues is necessary to create unified methods adapted to industry needs.

The purpose of this article is to systematize existing scientific findings and establish an analytical foundation for further applied research in the field of polymer nanocomposites. To enable the effective use of nanocomposites, it is also necessary to classify and analyze the existing challenges, which will help anticipate and mitigate potential shortcomings. These issues are the focus of the present study. Accordingly, the aim of the research is to provide a systematic overview of the properties of polymer nanocomposites based on the type of nanoparticles used, the method of their incorporation, and the characteristics of the polymer matrix, culminating in practical recommendations for reducing technological risks.

The aim is to accomplish the following tasks:

To conduct a critical analysis of the sources.

To make a comparative table of the types of nanoparticles.

To systematize the scaling issues.

To develop a generalized classification of technological barriers and ways to overcome them.

To identify perspective directions for improving nanocomposite production technologies, considering the achievements of modern nanochemistry and polymer synthesis and eliminating shortcomings.

2 Research design and analytical framework

Methodological basis of this study is the content analysis of modern scientific publications published in the international scientific databases Scopus, ScienceDirect, and Springer in the period 2018–2024. This method was used because of its effectiveness in identifying trends and structuring scientific information from a large array of sources. This study selected sources that cover the latest results of both experimental and theoretical work on the use of nanoparticles in polymer composites.

The content analysis involved studying the content of publications by a number of key variables that allow for a structured comparison of the impact of different types of nanofillers on the functional characteristics of polymer composites. This approach ensures the objectivity of generalizations and allows systematizing disparate data obtained in different research groups. The main variables included in the analysis include the chemical nature of the nanoparticles. Four main categories were considered: carbon nanoparticles (e.g., nanotubes, graphene structures), silicate (e.g., montmorillonite), metal (silver, copper, zinc, etc.), and hybrid nanoparticles that combine several types of materials. These groups each have unique properties that have different effects on the characteristics of composites.

The methods of introducing the nanofiller into the polymer matrix were also analyzed. These include mechanical mixing, ultrasonic dispersion, in situ polymerization, and other methods that determine the uniformity of nanoparticle distribution in the matrix and, accordingly, the stability of the resulting material. The types of polymer matrix, which include thermoplastics, thermosetting resins, and biopolymers, were a separate variable. Their structure, chemical activity, and thermal stability also affect the effectiveness of nanoparticle modification of composites.

The analysis also considered operational effects: changes in mechanical strength, heat resistance, barrier properties, and electrical conductivity of materials. Technological barriers accompanying the development and scaling-up nanotechnology production were also identified including particle agglomeration, low interfacial adhesion, difficulties in scaling up the process, and environmental and toxicological risks associated with the use of nanomaterials. The problems of using nanocomposites in industry and scientific research, including challenges related to economic feasibility, regulatory regulation, and assessment of long-term effects, are separately considered. This approach made it possible to identify the main patterns, summarize the results of research by different authors, and form a comprehensive view of the effectiveness of the use of nanoparticles in polymer composites in the context of modern engineering and applied problems.

3 Classification and characteristics of nanoparticles in polymer composites

PNCMs have attracted considerable scientific and applied interest in recent decades due to their ability to combine the unique properties of nanoparticles with the manufacturability and functionality of polymer matrices (Ajayan et al. 1994; Alabarse et al. 2021). The work of Japanese researchers from Toyota company, who in the late 1990s created nanocomposites based on polyamide-6 with modified nanoclays, which showed significant improvements in mechanical and thermal properties at low nanofiller content, was one of the first significant steps in this direction (Alexandre and Dubois 2000). According to a review by Ray and Okamoto (2003), nanofillers can change the morphology, crystallinity, permeability, and electrical and thermal conductivity of polymers. The literature also demonstrates fragmentation in the classification of nanoparticle types and the lack of uniform standards for their use, which makes it difficult to compare results empirically (Althobaiti et al. 2024).

Carbon nanomaterials, such as fullerenes, nanotubes, and graphene, occupy a special place in the literature. The work of Ajayan et al. (1994) proved that nanotubes have an extremely high elastic modulus, electrical conductivity, and thermal conductivity, which makes them widely used in structural and functional nanocomposites. Recent studies by Sudhindra et al. (2021) and Amjad et al. (2021) demonstrate that graphene-based nanofillers enhance the thermal conductivity of polymers depending on the lateral particle size, while Barani et al. (2020b) and Xiong et al. (2022) argue these nanofillers ensure multifunctionality, including electromagnetic shielding and heat dissipation. Graphene fillers are being examined as materials for thermal interfaces. A review by Lewis et al. (2021) shows that the introduction of graphene sheets increases thermal conductivity of polymer composites from 0.2 to 0.5 W/mK (pure polymer) to 5–12 W/mK, depending on their concentration, thickness, and dispersion. It is worth noting that graphene-based composites exhibit unique cryogenic properties: at temperatures around 77 K, they transition from thermal conductors to thermal insulators, which opens up possibilities for use in space technology and cryoelectronics (Ebrahim Nataj et al. 2023).

Ceramic nanofillers, such as titanium, aluminum, and silicon oxide nanoparticles, are used to increase the rigidity, ultraviolet resistance, and fire resistance of polymer systems (Barani et al. 2020a; Barshutina et al. 2021). The methods of intercalation and exfoliation of layered silicates described by Pinnavaia and Beall (2000) laid the foundation for the creation of organo-modified nanoclays that ensure the formation of intercalated or delaminated structures in the polymer matrix. As a generalization of these studies shows, the diversity of the chemical nature and morphology of nanofillers provides wide opportunities for targeted modification of polymer composites for specific functional tasks. This forms the basis for further research into the selection of optimal matrix-nanofiller combinations depending on the application and operational requirements. Organic nanofillers, such as dendrimers, hyperbranched molecules, and bio-based nanofibrils (e.g., cellulose), are also being intensively studied (Bin Rashid 2023). The work of Gandini and Belgacem (2008) indicates the possibility of using natural nanofillers to create biodegradable nanocomposites, which is a promising area for green chemistry and environmentally friendly materials.

Particular attention is paid to the technological challenges associated with the aggregation of nanoparticles, the need for their pre-functionalization, and ensuring a homogeneous distribution in the polymer matrix. Studies by Hussain et al. (2006) indicate the effectiveness of ultrasonic dispersing, high-temperature shear, and the use of surfactants to improve the compatibility of system components. Most studies emphasize that even with a low content of nanoparticles (1–5% wt%), a significant improvement in the performance properties of composites can be achieved, such as strength, heat resistance, electrical conductivity, optical transparency, and barrier properties (Feng et al. 2021).

Graphene nanofillers demonstrate a significant improvement in the mechanical, thermal, and electrical properties of polymer composites. The synergistic interaction of graphene with other fillers is of particular importance, as it improves the properties of the materials. Quasi-1D van der Waals fillers are a promising direction in the construction industry, as they provide for electrically conductive but flexible composites for shielding in the GHz and sub-THz ranges (Barani et al. 2021). The integration of nanoparticles into fiber-reinforced polymer (FRP) composites helps to improve mechanical properties, modify the surface, and provide sensory functions. There are various types of nanofillers, nanofibers, and nanocoatings used to strengthen, modify the surface, and improve the properties of FRP composites. Challenges associated with the integration of nanotechnology into composites are also discussed and recommendations for future research are provided.

Nanocomposites based on CNTs demonstrate improved mechanical, electrical, and thermal properties. Quantum composites with wave charge density phases are also a popular subject of modern research; these composites demonstrate new mechanisms for controlling electron transport and are promising for creating new generation functional materials (Barani et al. 2023). Particular attention is paid to the challenges associated with the uniform distribution of CNTs and the strength of the interface between the nanotubes and the polymer matrix (Shao et al. 2025). Polymeric nanocomposites (PNCs) are considered as a promising alternative to lead materials for X-ray protection (Habibi et al. 2010). Furthermore, the use of various nanofillers, such as gadolinium oxide, in polymer matrices to create effective and environmentally friendly materials for X-ray protection is analyzed. The impact of nanoparticles on composites in the construction industry, including concrete corrosion, is also considered (Jayakumar et al. 2024).

The mechanisms of interaction of nanoparticles with X-rays and the effect of particle size on shielding efficiency are also discussed. It provides a detailed analysis of polymer nanocomposite synthesis methods, such as melt intercalation, sol–gel processes, in situ polymerization, and emulsion techniques. The methods and characterization of nanocomposites, including atomic force microscopy (AFM), X-ray diffraction (XRD), scanning electron microscopy (SEM), and transmission electron microscopy (TEM), are also discussed. These methods allow studying the mechanical properties, structure, and morphology of nanocomposites (Kim et al. 2010).

These modern studies emphasize the importance of nanotechnology in improving the properties of polymer composites and open up new opportunities for their application in various fields, including aviation, medicine, and energy. However, these articles also highlight a number of shortcomings that need to be addressed or taken into account when going into production. For example, studies by Bin Rashid (2023) show that nanoparticles, due to their high surface energy, are prone to aggregation and cluster formation, which can destroy the homogeneity of the composition. Many works also describe the problem of uniform dispersion of the nanofiller, which also adversely affects the structure of the material matrix.

The articles emphasize the problem of scaling, since most studies were conducted in laboratory conditions close to ideal and these results are difficult to implement in industry due to the lack of scaling technology and empirical regulation in the regulatory framework. Ray and Okamoto (2003) also noted a deterioration in properties due to an increase in the concentration of nanofiller. Matrix instability and loss of primary properties is also inherent in some fillers, as well as a decrease in performance during repeated load tests and under environmental influences (Moosa and Saddam 2017). The lack of restraint and control of the polymer–nanofiller compound due to the destruction of ionic systems. These fillers are not all thermostable and fire-resistant, some have toxic properties, and there is a lack of a model base that would generalize nanocomposite models, which would allow predicting the properties of nanocomposites on a general scheme, without laboratories and costly tests (Muller et al. 2022; Shao et al. 2024).

The classification of nanoparticles is divided into two main classes: classification by chemical nature and classification by morphological features. The classification of nanoparticles by chemical nature allows determining the functionality for modifying polymers, while morphological features affect the dispersion method, the formation of interfacial interactions, and the final properties of nanocomposites. The research allows organizing the nanoparticles known from the analysis of sources into two author’s tables showing the features by chemical and morphological properties (Tables 1 and 2).

Classification of nanoparticles by chemical properties.

| Chemical properties | Examples of nanoparticles | Main properties | Disadvantages | Problems | Final effect | Examples of application |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon nanomaterials | Graphene, fullerene, SWCNTs, MWCNTs, nanocarbons, nanofibers | High electrical and thermal conductivity, mechanical strength | Aggregation, difficulty in dispersion | High cost, scalability | Strength, conductivity, thermal stability | Antistatic agents, EMI shields, electronics, sensors |

| Metal nanoparticles | Ag, Au, Cu, Ni, Fe, Zn, Ti | Antibacteriality, electrical conductivity, catalysis | Oxidation, toxicity (Ag, Cu) | Stabilization needs in the matrix | Antimicrobial, electrical properties | Medical coatings, packaging, flexible electronics |

| Ceramic and oxide | SiO2, TiO2, Al2O3, ZnO, Fe2O3, ZrO2, SiC, WC | Stiffness, heat resistance, dielectricity | Fragility, poor adhesion to the matrix | Need for functionalization | Increased strength and heat resistance | Heat-resistant coatings, barrier films, optics |

| Organic nanofillers | Dendrimers, polymeric nanoparticles | Functionality, biocompatibility | Mechanically weak, thermolabile | High complexity of synthesis | Structural controllability, softness | Drug release, gene carriers, hydrogels |

| Organometallic | Polysiloxanes, Si-organics | Elasticity, hydrophobicity, heat resistance | Limited reactivity | Slow polymerization | Flexible, moisture-resistant coatings | Construction sealants, electronics, flexible, moisture-resistant coatings |

| Aluminosilicates | Nanoclinoptilolite, Ag+-, Zn2+-, Cu2+-zeolites | Ionic exchangeability, thermostability, barrier properties | Low interaction with the polymer | Need for modification | Mass transfer control, stability | Eco-packaging, filters, humidity control |

| Nanocrystalline impurities | Nano-talc, nano-ZrO2, nano-oxides | Control of crystallization, morphology | Unpredictable compatibility | Poor grip | Improved structure and wear resistance | Foils, technical plastics and wear-resistant coatings |

-

Source: Compiled by the authors.

Classification of nanoparticles by morphological features.

| Type of morphology | Shape of particles | Examples | Features | Disadvantages | Problems | Final effect | Examples of application |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nanospheres (0D) | Spherical | Ag, SiO2, TiO2, polystyrene spheres | Isotropic properties, uniform dispersion | May produce agglomerates at high concentrations | Stability of the variance in the matrix | Improved mechanical and optical properties | Coatings, catalysis, optical materials |

| Nanotubes/fibers (1D) | Cylindrical, tubular | CNTs, ZnO, nanorods, nanofibers | High length-to-diameter ratio, directional conductivity | Difficulty of uniform distribution | Agglomeration, matrix compatibility issues | Increased rigidity, conductivity, functionality | Electronics, sensors, composite strengthening |

| Nanowafers (2D) | Layered structures | Graphene, nanoglue, mica, hexagonal BN | High modulus of elasticity, barrier properties | Difficult to distribute evenly, prone to agglomeration | Interfacial compatibility and stability | Increase in strength, heat resistance, barrier properties | Barrier coatings, electronics, composites |

| Nanoclusters (3D) | Aggregates or agglomerates | Assemblies of metal nanoparticles | High surface area, catalytic activity | Difficult to control the size of the mold | Uncontrolled merging of particles | Improving catalytic properties | Catalysis, medical diagnostics, sensors |

| Core–shell | Combined structures | Fe3O4 and SiO2, Ag and TiO2 | Possibility to combine different functions: magnetism + chemical stability | Complexity of synthesis, high cost | Ensuring the stability of the shell | Increased functionality, multifunctionality | Medical applications, magnetic materials, protective coatings |

-

Source: Compiled by the authors.

The classification of nanoparticles according to their chemical properties demonstrates a wide range of materials that can be used to modify polymer compositions. The main groups include carbon, inorganic (metal and ceramic), and organic polymer nanoparticles. These groups have their own unique properties, such as electrical conductivity, heat resistance, chemical activity, and high specific surface area, which allows for targeted influence on the physical, mechanical, electrical, thermal, barrier, and optical characteristics of polymeric materials, as well as for programming properties, including crystal growth.

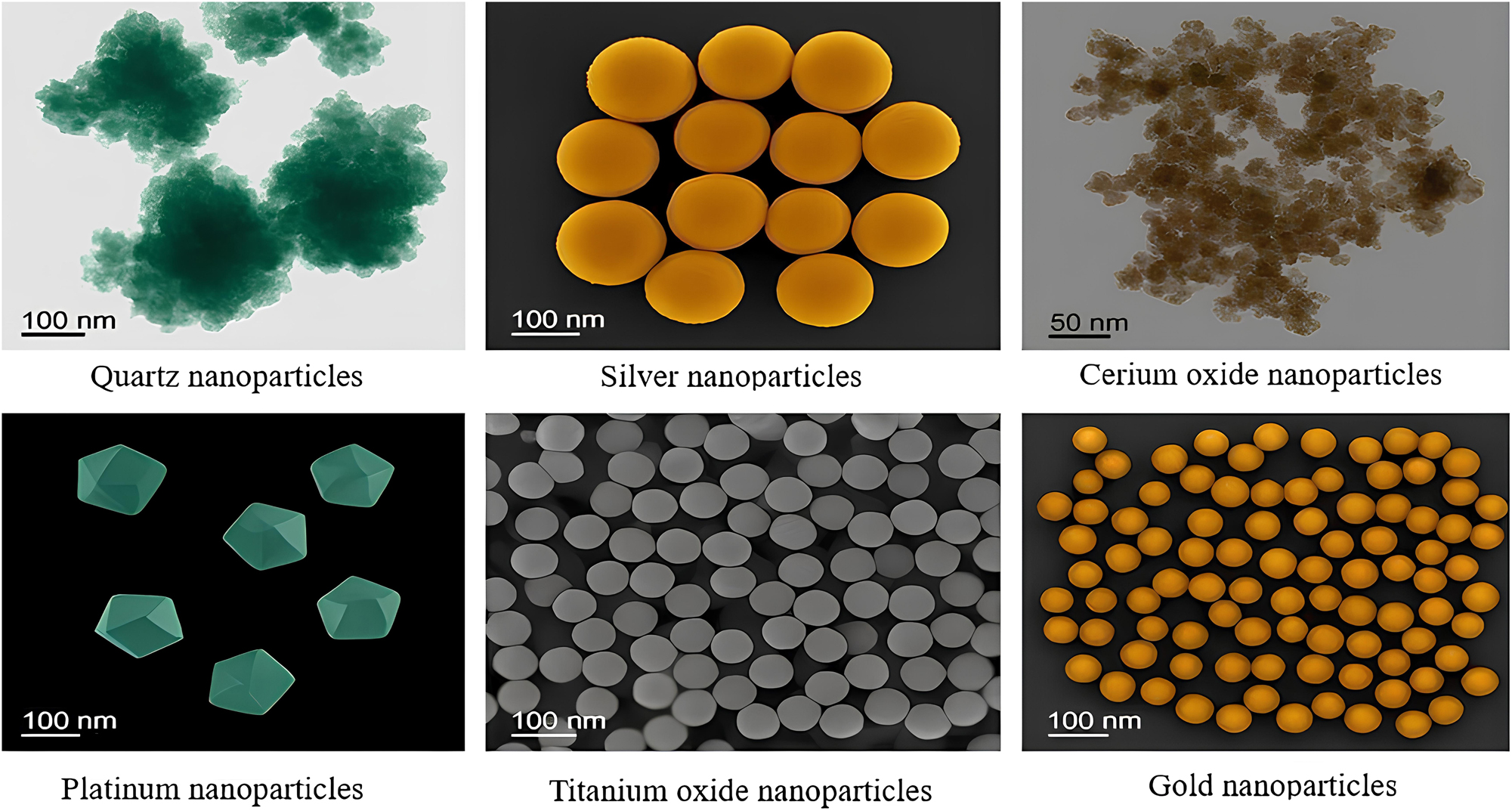

The morphological classification of nanoparticles provides a way to systematize them by shape, structure, and size, which is critical to ensure effective interaction with the polymer matrix. There are spherical (e.g., metal nanoparticles), tubular (CNTs, alumina nanotubes), lamellar (nanoscales, nanoclay), fibrous (carbon nanofibers, nanowires), and branched structures (dendrimers) (Kausar 2021; Jamil et al. 2024; Rahman et al. 2025). The morphology of nanoparticles significantly affects the mechanism of their dispersion, the degree of reinforcement, and the optical and electrical properties of the nanocomposite. Therefore, understanding the morphological features is key to optimizing the technology for obtaining PNCMs with specified performance characteristics (Figure 1).

Schematic representation of the main types of nanoparticles. Source: Developed by authors based on Jamil et al. (2024); Kausar (2021); Rahman et al. (2025).

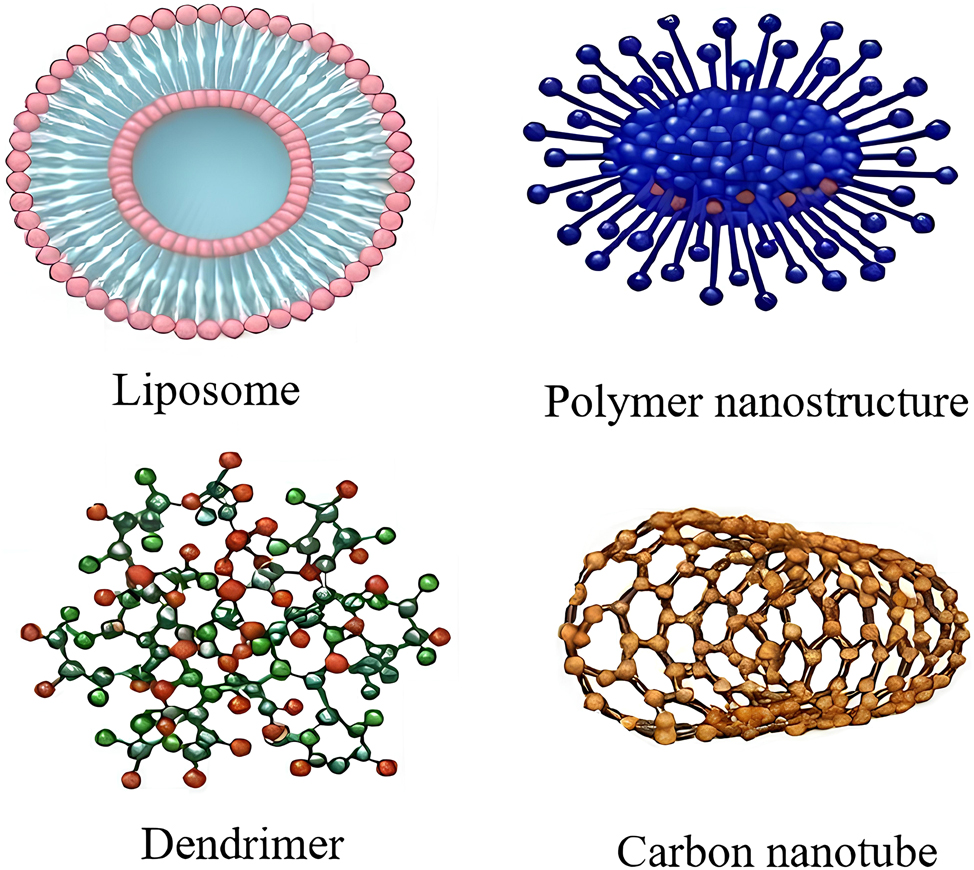

According to the size of the nanoparticles, a comparative figure was modeled, which shows that the size of the nanoparticles does not exceed 100 nm, only quartz nanoparticles are collected in cloud-like groupings of 200–400 nm, with some particles having a size of less than 50. The nanoparticles have a variety of shapes. Due to the influence of size effects, it is possible to obtain materials with unique characteristics while maintaining their atomic composition. This offers prospects for the development of ultra-strong and lightweight structures, elements of nanoelectronic devices, and the use of nanostructures in catalysis, conductive coatings, and protective barriers. Visualizations of nanostructure models were also created for a clearer understanding of the processes (Figure 2).

Schematic representation of nanostructured formations.

Fullerenes, nanotubes, and graphene materials can significantly improve the mechanical and electrophysical characteristics of composites (Njuguna et al. 2008). Metal and ceramic nanoparticles, such as gold, silver, or metal oxide nanoparticles, offer unique optical and catalytic properties. Their incorporation into polymer matrices makes it possible to create materials with specified functional characteristics. Layered silicates and galloysite nanotubes are of particular interest, as they can significantly improve the barrier properties of materials. Technological aspects of obtaining such composites include both traditional mechanical mixing methods and innovative approaches such as polymerization or self-assembly.

The main objective is to ensure an even distribution of fillers and minimize their aggregation. Methods of surface modification, in particular covalent functionalization and the use of surfactants, are actively used to solve this problem. Promising areas for the development of this industry include the development of hybrid systems combining organic and inorganic components, as well as the creation of “smart” materials with controllable properties. Biopolymer composites with natural fillers that meet modern environmental safety requirements have particular potential.

4 Technological methods for producing polymer nanocomposites

The main technological approaches to the production of PNCMs can be divided into several groups, including three methods: (1) mechanical mixing, (2) chemical synthesis, and (3) physical processes.

Mechanical mixing is the simple compounding of nanoparticles by mixing components in a molten liquid or solid state. Mechanical devices such as blenders and mills can be used. This approach allows to obtain composites with a good dispersion of fillers under appropriate process parameters. Calendering can be performed by rolling between rollers to form a thin layer. It can be used to create layers and apply films to a surface with uniform thickness. Mechanomechanical alloying is used to increase the interaction of phases, form the specified parameters in the matrix, and form an interface. Mixing is performed in a high kinetic energy planetary or ball mill.

Extrusion is performed at high temperature using a screw extruder and can be used on an industrial scale without solvents. Solvent mixing using ultrasonication is performed by pre-dispersing the nanophases in a solvent, followed by mixing the polymer for an improved dispersion of the nanoparticles. Compression molding is applied by combining pressure and temperature to molded and sheet materials. Mechanical methods are the main tool in the production of nanocomposites both in the laboratory and at industrial scale. These methods sometimes need to be combined with other approaches.

The most common method for creating polymer nanocomposites is mechanical mixing, a simple and accessible method that enables the achievement of an acceptable dispersion of nanoparticles under the right conditions. This method is used in construction, electronics, and basic polymeric materials. To create thin foils, calendering is used, which ensures uniform application but is not suitable for bulk products. The method is effective in the production of barrier films. Mechanical and chemical alloying improves the adhesion between the phases and the mechanical properties of the composite, although it requires high energy consumption. It is used in high-strength materials, in particular for aviation.

Extrusion provides high productivity and uniform mixing, but the high temperature of the process can change the nanophases. The method is widely used in industry for cable insulation. Ultrasonic mixing gives a good dispersion of nanoparticles, especially functionalized ones, although it requires solvents and drying. It is suitable for biomedical materials and nanocoatings. Compression molding, in turn, provides the desired shape and density of products, although it does not guarantee a uniform distribution of nanophases. It is used for sensors and structural elements. Extrusion and compression molding have the greatest industrial potential. These methods are well scalable, enable process automation, and form final products without significant loss of material or structure. Individual methods have specific applications. For example, calendering is effective for creating barrier films, and mechanical and chemical alloying is effective for increasing strength in compositions with high interfacial loads. Existing methods require additional improvements.

It is necessary to reduce energy consumption, optimize parameters to preserve the structure of the nanophase, minimize the use of toxic solvents, and ensure a controlled interface in the matrix. Mechanical methods are not universal, but they play an important role as a pre-treatment stage in complex technological schemes (along with chemical or plasma processing methods). Different methods are used to create polymer nanocomposites. The sol–gel method is based on the hydrolysis and condensation of metal precursors in the polymer.

In situ polymerization involves the introduction of nanoparticles into the nanomer polymerization process, which ensures their uniform distribution in the matrix. Polymerization can occur by a radical mechanism, in particular through open or closed radicals. Chemical reduction allows metal ions to be converted into nanoparticles in the presence of polymers. By precipitation, nanoparticles are formed when the dissolution conditions change. Solvothermal and hydrothermal synthesis ensure the formation of structured nanophases. Electrochemical synthesis is used to precipitate nanoparticles by electrolysis, which allows controlling the composition and structure of nanocomposites.

Plasma treatment is used to functionalize the surface of nanoparticles or matrix without chemicals, improves adhesion, and is more environmentally friendly. Physical vapor deposition (PVD) is the sputtering of nanoparticles onto a polymer surface in a vacuum. It allows controlling the purity and thickness. Sputter deposition is the formation of nanocomposites by sputtering under the influence of a magnetic field (Table 3).

Disadvantages and problems of physical processes and chemical synthesis methods.

| Method | Disadvantages | Problems | Application examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sol–gel | Slow process, need for careful control of pH and temperature | Formation of gel-like phases with low stability | Optical coatings, heat-resistant membranes |

| In situ polymerization | Difficult initiation, dependent on the type of monomer | Controlling the degree of polymerization, risk of aggregation | Conductive polymers, sensors, membranes |

| Chemical recovery | Requires controlled reaction conditions | Difficulties in stabilizing particles in a polymer | Antibacterial films, electrically conductive composites |

| Precipitation | Low reproducibility, solvent dependence | Formation of large clusters | Catalysts, porous composites |

| Solvothermal/hydrothermal synthesis | High temperature and pressure, difficult to scale | Size and uniformity control | Piezoelectric materials, photocatalysis |

| Electrochemical synthesis | Need for an electrically conductive environment | Limited compatibility with specific polymer matrices | Sensors, batteries, anti-corrosion coatings |

| Plasma treatment | Limited penetration depth | Need for expensive equipment | Adhesives, biocompatible coatings |

| Physical vapor deposition (PVD) | High cost, vacuum equipment | Difficulties in covering complex geometry | Optics, semiconductors, protective films |

| Sputter deposition | Energy consumption, sensitivity to process conditions | Heterogeneous coating over a large area | Solar cells, sensors, barrier coatings |

-

Source: Compiled by the authors based on Mittal (2009); Sabapathy et al. (2022); Tan et al. (2020).

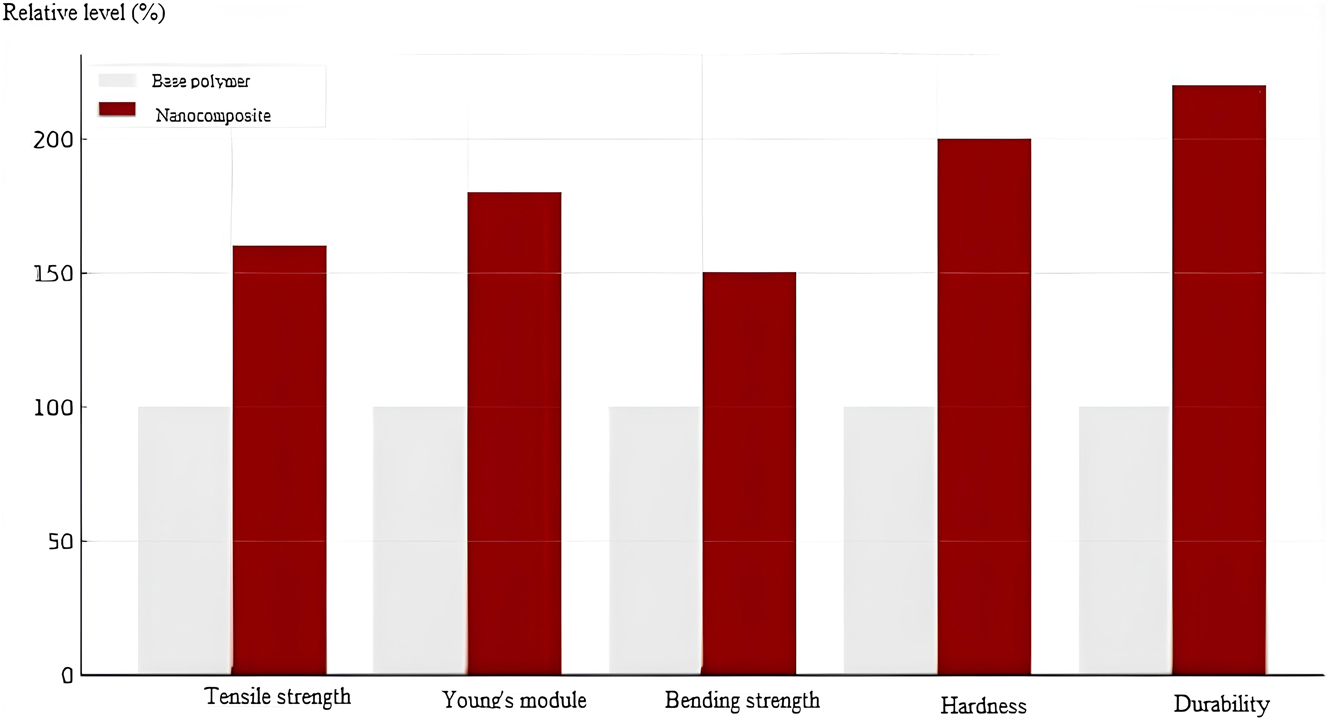

Table 3 shows that chemical synthesis methods provide a deep integration of nanoparticles into the matrix, which allows for the formation of compositions with high stability and controllable properties. The challenges remain the complexity of scaling and energy costs, which limit the commercialization of some approaches (especially PVD and sputter deposition). The combination of chemical and physical methods can significantly expand the functionality of PNCMs, for example, in situ polymerization followed by plasma treatment. Further research should focus on optimizing processes to reduce cost and improve repeatability, as well as developing new precursors and polymer matrices with improved compatibility. The properties of polymers change significantly with the addition of nanocomposites. Studies by Habibi et al. (2010), Muller et al. (2022), Usuki et al. (1993), and Jafarzadeh et al. (2023) show that tensile strength increases up to 60 %, elastic modulus (Young’s up to 80 %), bending strength up to 50 %, hardness in some cases doubles, wear resistance, and performance properties sometimes exceed 120 % (Figure 3).

Schematic generalization of the influence of nanofillers on the properties of polymeric materials. Source: Compiled by the authors based on Li et al. (2024), Saleh et al. (2020), and Wang et al. (2024).

The effect of various nanomodifiers (graphene, SiO2, TiO2, MMT clay, ZnO, and Al2O3) on heat-resistant, optical, and barrier properties is shown in Figure 4. The graph is conditional, showing the level of influence from 0 to 10 for the corresponding pair “property–nanoparticle.”

Overview of the effects of selected nanoparticles on the thermal stability, optical transparency, and barrier performance of polymer nanocomposites. Source: Compiled by the authors based on Li et al. (2024); Saleh et al. (2020); Wang et al. (2024).

These summarized data showed that nanoparticles improve the optical properties, and that transparency is maintained when properly dispersed (Mittal 2009; Saleh et al. 2020). It is also possible to adjust and reduce the transparency during the aggregation of nanoparticles (Rahman et al. 2025; Teijido et al. 2022). The absorption of ultraviolet rays is enhanced by ZnO and TiO2 nanoparticles. Barrier properties due to the influence of nanoparticles increase gas and moisture resistance due to the labyrinth effect, reduce the diffusion of oxygen and other gases and liquids, stabilize the structure of water under the influence of aggressive media, for example, nanoclays (MMT, chlorite) in PET reduce oxygen permeability by up to 70 %, and PNCM with nanoclinoptilolite improve the impermeability of packages (Ren et al. 2023).

Nanoparticles, such as metal oxides, carbonates, and organic fillers, can significantly increase the mechanical strength of polymer composites due to better load distribution and the ability to increase intermolecular interactions in the matrix. This makes it possible to create materials with improved tensile, compressive, and impact strength characteristics. Nanoparticles can increase the stiffness of a material because they can act as “reinforcers,” especially in the case of a polymer that is sufficiently elastic in nature.

Studies by Chan et al. (2021) confirm that nanofillers (SiO2, Al2O3, CNT, and graphene) introduced into polymer matrices reduce the coefficient of friction and increase wear resistance as their ability to absorb and distribute mechanical loads prevents the formation of cracks. The addition of nanoparticles, such as metal oxides (Al2O3, TiO2) or silicates, increases the thermal stability of composites due to their high melting and decomposition temperatures. Graphene and CNTs improve the thermal conductivity of polymers, which is important for high-temperature applications and electronics. Nanoparticles reduce the probability of thermal decomposition of polymers, but if the particles are unevenly distributed or aggregated, overheating can occur, which reduces the effectiveness of protection.

The addition of nanoparticles can affect the transparency of polymers. For example, oxides such as TiO2 reduce light transmission, while graphene or CNTs change color or visual effects. Light scattering depends on the type of nanoparticle: SiO2 or Al2O3 can change the transparency and reflective properties of the material. TiO2 and ZnO nanoparticles effectively block ultraviolet radiation, increasing the heat resistance and durability of polymer composites. Nanoparticles, such as graphene and metal oxides, significantly improve the barrier to gases, moisture, and other molecules, making composites effective for food and pharmaceutical packaging. They also reduce the permeability of corrosive agents such as oxygen and moisture, providing corrosion protection in aggressive environments. Nanoparticles can also serve as a barrier to toxic substances, increasing the chemical resistance of materials (Table 4).

The effect of nanoparticles on the properties of composites.

| Feature | Improvements due to nanoparticles | Limitations/disadvantages | Problems | Final effect | Application examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mechanical | +50–100 % increase in strength and stiffness | Aggregation, reduction of plasticity | Control of particle size and dispersion | Improving the bearing capacity of the material | Aircraft components, protective shells, sports equipment |

| Heat resistant | +10–30 °C to Tg, increase in Td | Difficulty of uniform distribution | Risk of phase delamination at higher temperatures | Increased operating temperature | Composites for electronics, automotive parts, heat-resistant coatings |

| Optical | Transparency preservation, UV protection | Turbidity during agglomeration | Difficult to achieve stable dispersion with high filler content | Photo-aging retardation, color protection | Packaging films, sun protection panels, optical lenses |

| Barriers | −50 % to 70 % to the permeability of gases | Dependence on the orientation of nanoparticles | Difficult to ensure a uniform orientation in the matrix | Reduced permeability to O2, CO2, H2O | Food packaging, pharmaceutical containers, filtration membranes |

Nanomodifiers impart new functional properties to composites, including electrical and thermal conductivity (Nista et al. 2023; Yarovyi et al. 2025), and enhance their dielectric and antibacterial characteristics (Li et al. 2024). The most pronounced effect is observed in the increase in mechanical strength, heat resistance, barrier, and optical characteristics. In particular, stiffness and strength can increase by 50–100 %, which is critical for structural materials. This improvement is accompanied by certain technological and morphological limitations. Mechanical strengthening is often accompanied by a decrease in ductility due to the aggregation of nanophases, and an increase in barrier properties depends on the direction of the nanoparticles, which is difficult to control.

Uniform dispersion of nanoparticles is a critical success factor. All four groups of properties (mechanical, heat-resistant, optical, and barrier) have a problem of agglomeration or uneven distribution of nanophases, which limits the potential of nanocomposites. The shape and size of nanoparticles are crucial to achieving the desired effect. For example, lamellar nanoparticles provide better barrier properties, while spherical nanoparticles provide uniformity of dispersion, which is important for optical transparency. The range of applications for nanocomposites is greatly expanding due to the ability to fine tune properties. The use of nanophases makes it possible to adapt polymers to specific operating conditions, from aircraft components and packaging to optics and heat-resistant elements (Su et al. 2021).

Despite the advantages, there is a need for further optimization of nanoparticle introduction technologies, including dispersion, interfacial interaction, and scalability, which is the subject of active research. Nanoparticles improve the performance characteristics of polymers, but they also have their disadvantages. The stability of the nanocomposite structure and control of morphology are important to avoid deterioration of transparency or brittleness, or to use hybrid composites to achieve the effect of synergism.

PNCMs are widely used in various industries due to their combination of lightness, high mechanical properties, chemical and thermal resistance, and ability to be functionalized. For example, they are used to create lighter yet stronger automotive components, which reduce vehicle weight and increase energy efficiency. Details of the car and its interior, such as bumpers, door panels, and dashboards, are where nanoclay or nanosilica is used to improve rigidity, wear resistance, and UV stability. Components such as tubes, linings, and covers that need to be heat-resistant – polyamide-based CNTs with TiO2 or Al2O3 nanoparticles – are effective here. The use of CNTs avoids the accumulation of electrical charges, which is important for electronics in cars. Polymer nanocomposites provide an optimal combination of high strength and low weight, which is critical for aviation and space applications. Structural components such as fuselage strength members and wing skins, where nanocomposites based on epoxy resins with nanocarbons or graphene, are used. Thermal insulation materials such as multilayer thermal protection systems with nanofillers provide protection for vehicles during reentry. Radiation shielding: polymers modified with B4C or Gd2O3 nanoparticles are used to protect against cosmic radiation (Teijido et al. 2022).

Nanocomposites can be used to create both conductive and insulating polymeric materials with high stability. Flexible electronics: PNCMs based on PET or polyurethanes with the addition of graphene or Ag nanoparticles are used in touch panels and flexible displays. Electrical insulating films: SiO2 or Al2O3 nanoparticles in polyamides or PVC provide high dielectric stability over a wide temperature range. Capacitors and transistors: nanocomposites with high specific capacitance are used in the miniaturization of microelectronics. Polymer nanocomposites change the properties of conventional packaging materials, making them more functional and safer. High-barrier films include nanoclay incorporated into polyethylene or polypropylene, which reduces the penetration of oxygen, moisture, and CO2. Antimicrobial coatings include polymers with silver or zinc nanoparticles that inhibit bacterial growth, which is especially important for dairy and meat products. “Smart” packaging is the use of sensor nanoparticles that change color when the pH or temperature changes, informing the consumer about the condition of the product (Trykoz et al. 2021).

PNCMs can also create more durable, lightweight, heat-resistant, and decoratively attractive building materials. Self-cleaning facades: coatings based on TiO2 demonstrate photocatalytic activity, which provides a self-cleaning effect. Polymer–cement sealants with the addition of nanosilica or graphene have increased adhesion and a longer service life. Nanoporous polymers or aerogels with nanoreinforcement have low thermal conductivity while maintaining stability at high temperatures. The use of polymer nanocomposites in construction is a promising area that can significantly improve the performance of materials, increase the durability of structures, and expand the functionality of building elements. The main areas of application are described in detail in Table 5.

The use of nanocomposites in construction.

| Application | Nanofillers | Examples of materials/objects | Main functional properties | Disadvantages | Final effect | Application examples | Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sealants and adhesives | SiO2, Al2O3, CNT, nanoclays | Polymer sealants, facade adhesives | Improved adhesion, water resistance, UV and frost resistance | Deterioration of flexibility with an excess of nanophases | More durable connection in difficult conditions | PVC bonding, sealing of joints | Alexandre and Dubois (2000), Ajayan et al. (1994), Usuki et al. (1993) |

| Protective coatings | TiO2, ZnO, graphene, Fe2O3 | Paints, varnishes, anti-corrosion coatings | Self-cleaning, anti-corrosion, hydrophobic, heat resistance | Cost of functional nanophases | Coating stability under the influence of atmospheric factors | Self-cleaning facades, pipe coatings | Iijima (1991), Ray and Okamoto (2003) |

| Thermal insulation materials | Nano-SiO2, aerogels | Insulation, heat-insulating panels | Low thermal conductivity, fire resistance, biostability | Fragility of some structures, high cost | Reduced heat loss, improved energy efficiency | Aerogel inserts in double-glazed windows | Feng et al. (2021), Yang et al. (2022) |

| Structural composites | CNT, basalt and fiber, graphene | Reinforced panels, composite reinforcement | High strength, crack resistance, chemical resistance | High cost, difficulty in linking to the matrix | Reduced weight of structures, increased durability | Bridges, facades, engineering structures | Alexandre and Dubois (2000), Iijima (1991), Pinnavaia and Beall (2000) |

| Translucent | ZnO, CeO2, Ag | Polycarbonate | UV protection | Decrease | Multifunctionality | Medical | Ajayan et al. (1994), Feng et al. (2021) |

| Сomposites | Panels, photochromic glass | Photochromic, antibacterial | Transparency in agglomeration | Interior and exterior glazing | Screens, facades and systems | Habibi et al. (2010) | |

| Floor and road surfaces | Al2O3, nano-SiO2, graphene | Polymer concrete, epoxy coatings | Wear resistance, anti-slip, chemical resistance | Material stiffness, fragility in frosty conditions | Long-term operation, minimum maintenance | Garage floors, parking lots, sidewalks | Jahangiri and Rostamiyan (2024), Iijima (1991) |

| 3D printing of structures | Nanoclay, graphene, SiO2 | Printed facades, insulating elements | High geometric accuracy, functionality, heat resistance | Mixture viscosity, nanophase settling | Fast formation of individualized elements | Wall panels, brackets, touch units | Gandini and Belgacem (2008), Pinnavaia and Beall (2000), Ray and Okamoto (2003) |

-

Source: Compiled by the authors.

PNCMs in biomedical applications allow for the creation of functional materials with biocompatible, antimicrobial, or bioactive properties. Nano-hydroxyapatite in a polymer matrix (such as PLA or PCL) provides better integration with bone tissue. Polymer nanocapsules or gels enable the controlled release of drugs into targeted areas. Wound dressings that contain silver nanoparticles accelerate healing and prevent infection (Usuki et al. 1993). The functionalization of fibers at the nanoscale opens the way to the creation of high-tech textiles, such as the use of silver, copper, or ZnO in fibers for medical and sportswear. PNCMs with fluorinated nanoparticles or hydrophobic nanostructures provide moisture protection. The inclusion of conductive nanoparticles allows for the creation of interactive fabrics (e.g., electric clothing and health monitoring).

In the energy sector, nanocomposites reduce losses, improve efficiency, and increase the durability of materials. PNCMs based on perfluorinated polymers with ZrO2 or SiO2 nanoparticles stabilize conductivity at high temperatures. Metal nanoparticles or CdSe nanopoints increase the efficiency of light conversion. The use of graphene, MnO2, CNTs in composite electrodes increases capacity and cyclic stability. PNCs are multifunctional materials that expand the boundaries of what is possible in modern industry. Their use not only improves product efficiency but also solves problems related to energy efficiency, biosecurity, lightweight construction, durability, and environmental safety, which will improve some aspects.

High mechanical and thermal properties of nanocomposites make it possible to produce stronger, more durable, and stable materials. The introduction of nanoparticles can reduce energy consumption for the manufacture of materials, as well as improve thermal and electrical properties, which is especially important in the energy sector. Nanocomposites can provide the required level of biocompatibility for medical and biotechnical applications, making them important for the manufacture of medical implants, biosensors, etc. The use of nanoparticles can significantly reduce the weight of the final material, which is important for the automotive, aerospace, and aerospace industries. Polymer nanocomposites exhibit increased resistance to corrosion, aging, and mechanical damage, which increases the service life of products.

5 Barriers and strategies for advancing polymer nanocomposite technologies

Nanoparticles have a high surface energy, which leads to their aggregation (cluster formation), worsening the homogeneity of the composite and, as a result, reducing the mechanical, thermal, and electrical properties of the composite and the formation of defects. The study conducted by Hussain et al. (2006) shows the problem of uneven distribution in the polymer matrix and shows the difficulty of uniform dispersion of nanofillers in a viscous polymer matrix. It is necessary to achieve uniform dispersion of nanofillers to overcome this phenomenon. Ultrasonic dispersing, surface functionalization, and the use of surfactants are one of the methods to overcome this problem. Ajayan et al. (1994) and Ray and Okamoto (2003) show the necessity of functionalization of nanofillers, as most nanomaterials are chemically inert or poorly compatible with polymer. As a solution to this issue, surface functionalization (oxidation, silanization, etc.) is necessary, but it adds additional stages to the production process.

The integration of nanoparticles into traditional manufacturing processes can be technically challenging, as production lines need to be adapted to the new materials. Barshutina et al. (2021) noted that the use of nanocomposites with graphene and CNTs requires specialized equipment for their processing and stability during the production process. The authors show that most effective methods (e.g., in situ polymerization or layer-by-layer deposition) are laboratory-based and difficult to scale up to industrial levels, thereby highlighting the problem of difficulty in scaling up synthesis methods. Ray and Okamoto (2003) show an insufficient increase in properties with an increased concentration of nanoparticles. The fact that an increase in the content of nanofillers beyond the optimum level (usually 3–5%) leads to a deterioration in properties.

The reason for this is the oversaturation of nanoparticles (sometimes in small volumes), which for industrial batches must be measured empirically, aggregation, and reduced processability. As a result of their small size, nanoparticles can penetrate cells and tissues, leading to unclear health effects. Wong et al. (2021) emphasize the need for a more detailed study of the possible negative effects of nanoparticles on humans and the environment, especially when using nanocomposites in medical and biotechnology applications. The instability of properties under repeated loading or aging and changes in properties over time or during operation (humidity, UV, temperature) when interacting with the environment, interface degradation occurs.

Ajayan et al. (1994) and Ray and Okamoto (2003) show insufficient control over the structure of the polymer–nanoparticle interface and the dependence of electrical properties on the quality of the interface (this issue is not sufficiently studied). Ray and Okamoto (2003) also show that not all nanofillers provide adequate thermal stability. Some nanoparticles may be toxic or have difficult disposal. This raises the issue of biocompatibility and environmental friendliness. It is also evident that there is an insufficient fundamental modeling base and that there are no generalized models for predicting the properties of nanocomposites with different types of matrices and nanofillers. Although PNCMs have extremely promising properties, the main difficulties are related to manufacturing technology, structural stability, interface control, environmental safety, and commercial scalability. The main problems and ways to overcome them are shown in Table 6.

The main problems of nanotechnology implementation in production and solutions.

| Problem | Solutions | Authors’ comments |

|---|---|---|

| Aggregation of nanoparticles | Superficial functionalization (–COOH, –OH, –NH2); ultrasonic dispersion, use of dispersants | Aggregation significantly reduces the effectiveness of nanofillers; combined dispersion methods give better results |

| Low adhesion at the matrix-filler interface | Coupling agents (silanes, maleic anhydride); surface functionalization; interfacial polymers | The contact zone is critical for strength; the use of silanes is effective for mineral nanofillers |

| Limited scalability of synthesis | Melt blending; extrusion; injection molding; minimizing the use of solvents | Process scalability is important for industrial implementation; melt blending is the most compatible with existing technologies |

| Instability of properties with time | Antioxidants; UV stabilizers; particle encapsulation; stable polymer matrices | Aging of materials is critical for long-term use; encapsulation increases the stability of nanoparticles |

| Toxicity, low biocompatibility | Biodegradable polymers (PLA, PHBV); natural nanofillers (cellulose, biogel, chitosan); green synthesis | Sustainability of materials is essential for biomedical and packaging applications |

| Insufficient hardening or thermal stability | Hybrid nanofillers; orientation of reinforcing particles; matrices with high Tg | The synergy of nanofillers (e.g., graphene + metal oxides) provides high rigidity and heat resistance |

| Limited functionality (electrical, thermal, bioactivity) | Multifunctional nanofillers (graphene, CNT, metal nanoparticles); synergistic composites | There is a growing demand for composites with integrated sensory, thermal conductive or antibacterial properties |

| Lack of unified research methods | Standardization of testing; interlaboratory validation; ISO/ASTM protocols | The unification of methods will make it possible to compare the results of different researchers and increase the reliability of conclusions |

-

Source: Compiled by the authors.

The analysis of scientific publications reveals a number of common technical and technological barriers that hinder the effective implementation of polymer nanocomposites. In recent years, a number of strategies have been proposed to overcome these difficulties, covering both chemical modification of components and optimization of processing technologies. The problem of nanoparticle aggregation can be mitigated by functionalizing the surface of nanofillers, in particular, by chemically attaching hydrophilic or reactive groups that increase their compatibility with the polymer matrix.

The use of ultrasonic dispersion, high-energy mixing, dispersants, and interface modifiers significantly improves the homogeneity of the system. Another important problem is the weak adhesion at the matrix–filler interface. It is overcome by the use of coupling agents (e.g., silanes, maleic anhydride), which promote the formation of a chemical or intermolecular bond between the phases. The key limitation is the scalability of the synthesis processes. On an industrial scale, the most promising are the methods of melt-blending, extrusion, and injection molding, which allow producing nanocomposites without the use of toxic solvents. The issues of biocompatibility and environmental compatibility are also relevant, which can be solved by introducing biodegradable polymers and natural nanofillers (cellulose, chitosan, bioglue) (Table 7).

Disadvantages of using nanoparticles.

| Research overview | Subject of the research | Disadvantages and challenges |

|---|---|---|

| The effect of graphene on the thermal and electrical conductivity of polymers | Improving the functional properties of nanocomposites | High tendency of graphene to aggregate, difficulties in scaling |

| Overview of mechanical and thermal properties of nanocomposites | Polymer reinforcement with nanoparticles | Wide variety of results, sensitivity to processing technology |

| Mechanical properties of polymers with nanofillers | Deformation characteristics of nanocomposites | Difficulty in predicting material behavior under changing conditions |

| The role of interfacial interaction in polymer composites | Analysis of the structure–property connection | Instability of interfacial bonds under prolonged loading |

| Fabrication of nanocomposites using CNTs | Nanotubes as reinforcing agents | Toxicity issues, low reactivity of the CNT surface |

| Improved fire resistance due to nanofillers | Fire resistance of polymers | Deterioration of mechanical properties when overfilled |

| Hybrid nanocomposites based on clay and oxides | Combined reinforcement to improve all groups of properties | Difficulty in controlling the homogeneity of the structure |

| Polymer nanocomposites for sensors | Optoelectronic applications of polymers | Problems of long-term stability of electrical properties |

| Estimation of nanoparticle dispersion in a polymer matrix | Methods of composite quality control | Lack of unified quality assessment methods |

| Mechanisms of reinforcement in CNT-based nanocomposites | Mechanical reinforcement at the nanolevel | Low degree of CNT adhesion to the polymer |

| Research of the texture of CNT composites | Structural organization of fillers | Difficulties in controlling the orientation of nanofillers |

| Improving the thermal characteristics of composites with nanoparticles | Thermal protection and stability of polymers | Risk of overheating due to inefficient heat distribution |

| Electrically conductive nanocomposites with graphene and CNTs | Development of conductive polymers | High resistance at phase boundaries, instability in wet conditions |

| Biodegradable nanocomposites for medical purposes | Biomedical applications of nanomaterials | Biocompatibility and toxicity of degradation products |

| Mechanisms of self-organization of PNCs | Nanostructuring without external influence | Difficulties in scaling the process |

| Stability of nanocomposites in biological environments | Medical and environmental properties of polymers | Rapid degradation, the need for stabilizers |

| Physics of polymer nanostructures | Theoretical foundations of composites behavior | The complexity of practical application of theories |

| Interfaces in clay-based nanocomposites | Microstructure and its influence on macroscopic properties | Instability when moistened and delamination |

| Functionalization of the surface of nanoparticles | Improving the adhesion and dispersion of nanofillers | High cost and complexity of chemical modification |

| Compatibility of polymer matrix and nanomaterials | Chemical interaction and interfacial bonding | Insufficient predictability when changing the composition |

| Reducing electrical resistance with CNTs | Electrical conductivity of nanocomposites | Unstable behavior when temperature and load changes |

| The effect of nanoparticle size on the properties of composites | Nanometric polymer engineering | Difficulties in obtaining a narrow size distribution |

| Mechanical properties of kaolin-based nanocomposites | Reinforcement of polymers with mineral fillers | Low reactivity of kaolin, the need for functionalization |

-

Source: Compiled by the authors.

The intensive development of nanochemistry, polymer design, and interface engineering provides new opportunities for improving the technologies for creating PNCMs. The main goal is to increase the efficiency of nanofiller dispersion, achieve structural stability, controllable properties, and scalability of production. Surface functionalization of nanofillers is one of the key areas. The use of chemical modification methods (silanization, polymer wrapping, immobilization of functional groups) can significantly improve compatibility with the polymer matrix, avoid agglomeration, and ensure the formation of a stable interfacial layer. This is critical for the realization of the properties of PNCMs in real-world applications (Yang et al. 2022).

The synthesis of nanoparticles directly in the polymer matrix is another promising direction, in particular by gel processes, intercalation, or co-precipitation. This approach allows to achieve a uniform distribution of nanophases, avoid the stage of preliminary dispersion, and form new functional nanostructures in the polymer base. The use of controlled polymerization methods, such as RAFT (Reversible Addition–Fragmentation chain Transfer), ATRP (Atom Transfer Radical Polymerization), and NMP (Nitroxide Mediated Polymerization), also plays a significant role (Yuvaraj et al. 2023). These methods allow the creation of polymers with a narrow molecular weight distribution and specific architecture (branched star-shaped, block co-polymers), which contributes to the targeted control of interfacial interaction in the composite (Jahangiri and Rostamiyan 2024).

The engineering of the interface between the polymer and the nanophase is also gaining special attention. The formation of a covalently bonded or ion-associated interfacial layer not only increases the strength of the composite but also creates an active functional zone that participates in the transfer of charge, heat, or mass. Modern processing technologies also show potential. Ultrasonic extrusion, electrospinning, high-shear mixing, and additive technologies (3D printing), for example, provide high dispersion, nanophase orientation, and precision in the formation of the composite structure. The use of 3D printing of PNCMs provides a way to create functional-gradient and structurally complex products with adaptive properties. A separate area is represented by “smart” nanocomposites that can respond to external stimuli (temperature, pH, humidity, mechanical load).

The introduction of nanoparticles with the function of a sensor or regenerative component allows the creation of composites with self-diagnostic and self-healing properties. Ecologically oriented technologies are also actively developing including the production of PNCMs based on biopolymers (PLA, PHB, chitosan) with the introduction of biocompatible nanoparticles (nanocellulose, ZnO, nanofibers). These materials meet the requirements of sustainable development and biodegradability, and are used in green construction, bio-packaging, and disposable materials. Advanced technologies for the production of PNCMs are based on the integration of nanochemical approaches, controlled polymer synthesis, interface engineering, and advanced processing methods. This ensures the creation of a new generation of materials with multifunctional and adaptive properties suitable for use in high-tech fields, including energy, electronics, construction, and medicine.

6 Conclusions

The technological aspects of the production of composite materials based on nanoparticles are analyzed, and nanoparticles are classified according to their chemical nature and morphological features used to modify polymers. The main technological approaches to the production of polymer nanocomposites and the problems associated with the dispersion of nanofillers in the polymer matrix are characterized. The influence of nanoparticles on the physical and mechanical, heat-resistant, optical, and barrier properties of composites is analyzed. The examples of application of polymer nanocomposites in various industries are provided. The problems that hinder the introduction of nanocomposites in construction are generalized and classified for the first time. The main problems are highlighted and ways to solve them are proposed. Promising directions for improving nanocomposites production technologies are identified, considering the achievements of modern nanochemistry and polymer synthesis and eliminating their disadvantages.

Nanoparticles can significantly improve the mechanical properties of materials used in various industries. CNTs and graphene nanowafers are known for their high strength and resistance to mechanical stress, and they can improve the thermal properties of materials. This makes them ideal for creating lightweight yet strong materials for the aviation, automotive, and construction industries. Nanoparticles can significantly improve the energy performance of materials. Nanocomposites with graphene can be used to create highly efficient energy-saving coatings, which is important for reducing energy consumption in construction. Nanoparticles are also used to create biosensors, biomaterials, and nanopharmaceutical systems that can improve the diagnosis and treatment of diseases. Despite all its advantages, the problematic issues were also assessed, which demonstrates that in order to fully utilize them in production, it is necessary to go through interesting ways to improve production and eliminate disadvantages both targeted and comprehensively.

The generalization of the results of the literature analysis shows a high level of scientific interest in PNCs as multifunctional materials of a new generation to the synthesis and application of biodegradable polymers. At the same time, a number of problems have been identified that hinder the further development and widespread introduction of PNCs: reduced efficiency in the aggregation of nanoparticles and the lack of a stable dispersion, weak interfacial interaction, which reduces the strength and durability of materials, complexity of chemical compatibility between components, limited scalability of laboratory methods at the industrial level, insufficient standardization of methods for assessing properties, and limited data on the long-term effects of exposure to biodiversity and the environment.

Further research should be aimed at overcoming technological barriers, improving methods of structure management at the nano- and microlevels, and assessing the environmental and biological safety of nanocomposites at all stages of their life cycle. Modern scientific challenges require the integration of interdisciplinary approaches, functionalization of both nanofillers and polymer matrices, the use of natural and secondary resources as fillers, and the development of simple, reproducible, and promising solutions. Areas related to the creation of multifunctional and green nanocomposites with adjustable properties adapted to the requirements of sustainable development.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge financial support from the Science and Technology Department of Ningxia, the Scientific Research Fund of North Minzu University (no. 2020KYQD40).

-

Research ethics: Not applicable.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Author contributions: Andrii Bieliatynskyi: investigation; resources; funding. Leila Bouziane: conceptualization; software; validation. Olena Bakulich: writing – original draft; methodology. Viacheslav Trachevskyi: visualization; formal analysis; project administration. Mingyang Ta: writing – review & editing; supervision; data curation. All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: Grammarly was used to ensure proofreading.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors declare they have no competing interests.

-

Research funding: This research project was supported by funding from the Science and Technology Department of Ningxia, the Scientific Research Fund of North Minzu University (no. 2020KYQD40).

-

Data availability: Not applicable.

References

Ajayan, P.M., Schadler, L.S., and Braun, P.V. (1994). Nanocomposite science and technology. Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, Troy.Search in Google Scholar

Alabarse, F.G., Polisi, M., Fabbiani, M., Quartieri, S., Arletti, R., Joseph, B., Capitani, F., Contreras, S., Konczewicz, L., Rouquette, J., et al.. (2021). High-pressure synthesis and gas-sensing tests of 1-D polymer/aluminophosphate nanocomposites. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 13: 27237–27244, https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.1c00625.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Alexandre, M. and Dubois, P. (2000). Polymer-layered silicate nanocomposites: preparation, properties and uses of a new class of materials. Mater. Sci. Eng. R Rep. 28: 1–63, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0927-796x(00)00012-7.Search in Google Scholar

Althobaiti, M., Belhaj, M., Abdel-Baset, T., Bashal, A., and Alotaibi, A. (2024). Structural, dielectric and electrical properties of new Ni-dopedcopper/bentonite composite. J. King Saud Univ. 34: 102127, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jksus.2022.102127.Search in Google Scholar

Amjad, A., Anjang Ab Rahman, A., Awais, H., Zainol Abidin, M.S., and Khan, J. (2021). A review investigating the influence of nanofiller addition on the mechanical, thermal and water absorption properties of cellulosic fibre reinforced polymer composite. J. Ind. Text. 51: 65–100, https://doi.org/10.1177/15280837211057580.Search in Google Scholar

Barani, Z., Mohammadzadeh, A., Geremew, A., Huang, C.-Y., Coleman, D., Mangolini, L., Kargar, F., and Balandin, A.A. (2020a). Thermal properties of the binary-filler hybrid composites with graphene and copper nanoparticles. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30: 1904008, https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.201904008.Search in Google Scholar

Barani, Z., Kargar, F., Mohammadzadeh, A., Naghibi, S., Lo, C., Rivera, B., and Balandin, A.A. (2020b). Multifunctional graphene composites for electromagnetic shielding and thermal management at elevated temperatures. Adv. Electron. Mater. 6: 2000520, https://doi.org/10.1002/aelm.202000520.Search in Google Scholar

Barani, Z., Kargar, F., Ghafouri, Y., Ghosh, S., Godziszewski, K., Baraghani, S., Yashchyshyn, Y., Cywiński, G., Rumyantsev, S., Salguero, T.T., et al.. (2021). Electrically insulating flexible films with quasi-1D van der Waals fillers as efficient electromagnetic shields in the GHz and sub-THz frequency bands. Adv. Mater. 33: 2007286, https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.202007286.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Barani, Z., Sudhindra, S., Ramesh, L., Laulhé, C., Itié, J.-P., Fertey, P., Corraze, B., Ravy, S., Zybtsev, G., and Balandin, A.A. (2023). Quantum composites with charge‐density‐wave fillers. Adv. Mater. 35: 2209708, https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.202209708.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Barshutina, M.N., Volkov, V.S., Arsenin, A.V., Yakubovsky, D.I., Melezhik, A.V., Blokhin, A.N., Tkachev, A.G., Lopachev, A.V., and Kondrashov, V.A. (2021). Biocompatible, electroconductive, and highly stretchable hybrid silicone composites based on few-layer graphene and CNTs. Nanomaterials 11: 1143, https://doi.org/10.3390/nano11051143.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Bin Rashid, M. (2023). Exploring the versatility of aerogels: broad applications in biomedical engineering, astronautics, energy storage, biosensing. Mater. Today Sustain. 10: e23102.10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e23102Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Chan, J.X., Wong, J.F., Petrů, M., Hassan, A., Nirmal, U., Othman, N., and Ilyas, R.A. (2021). Effect of nanofillers on tribological properties of polymer nanocomposites: a review on recent development. Polymers 13: 2867, https://doi.org/10.3390/polym13172867.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Chang, A., Babhadiashar, N., Barrett-Catton, E., and Asuri, P. (2020). Role of nanoparticle–polymer interactions on the development of double-network hydrogel nanocomposites with high mechanical strength. Polymers 12: 470, https://doi.org/10.3390/polym12020470.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Ebrahim Nataj, Z., Xu, Y., Wright, D., Brown, J.O., Garg, J., Chen, X., Kargar, F., and Balandin, A.A. (2023). Cryogenic characteristics of graphene composites-evolution from thermal conductors to thermal insulators. Nat. Commun. 14: 3190, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-38508-3.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Feng, Z., Adolfsson, K.H., Xu, Y., Fang, H., Hakkarainen, M., and Wu, M. (2021). Carbon dot/polymer nanocomposites: from green synthesis to energy, environmental and biomedical applications. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 29: e00304, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.susmat.2021.e00304.Search in Google Scholar

Gandini, A. and Belgacem, M.N. (2008). Monomers, polymers and composites from renewable resources. Elsevier, Oxford.Search in Google Scholar

Habibi, Y., Lucia, L.A., and Rojas, O.J. (2010). Cellulose nanocrystals: chemistry, self-assembly and applications. Chem. Rev. 110: 3479–3500, https://doi.org/10.1021/cr900339w.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Hussain, F., Hojjati, M., Okamoto, M., and Gorga, R.E. (2006). Review article: polymer-matrix nanocomposites, processing, manufacturing, and application: an overview. J. Compos. Mater. 40: 1511–1575, https://doi.org/10.1177/0021998306067321.Search in Google Scholar

Iijima, S. (1991). Helical microtubules of graphitic carbon. Nature 354: 56–58, https://doi.org/10.1038/354056a0.Search in Google Scholar

Jafarzadeh, S., Farzaneh, A., Haddadi-Asl, V., and Jouibari, I.S. (2023). A review on electrically conductive polyurethane nanocomposites: from principle to application. Polym. Compos. 44: 8266–8302.10.1002/pc.27706Search in Google Scholar

Jahangiri, A.A. and Rostamiyan, Y. (2024). Influence of clay nanoparticles on morphology and mechanical properties of rezole phenol formaldehyde resin/carbon and glass hybrid short fibers nanocomposites. Polym. Bull. 81: 909–927, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00289-023-04742-4.Search in Google Scholar

Jamil, H., Faizan, M., Adeel, M., Jesionowski, T., Boczkaj, G., and Balčiūnaitė, A. (2024). Recent advances in polymer nanocomposites: unveiling the Frontier of shape memory and self-healing properties: a comprehensive review. Molecules 29: 1267, https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules29061267.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Jayakumar, S., Saravanan, T., and Philip, J. (2024). A review on polymer nanocomposites as lead-free materials for diagnostic X-ray shielding: recent advances, challenges and future perspectives. Hybrid Adv. 4: 100100, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hybadv.2023.100100.Search in Google Scholar

Kausar, A. (2021). Poly(methyl methacrylate)/fullerene nanocomposite: factors and applications. Polym.-Plast. Technol. Mater. 61: 593–608, https://doi.org/10.1080/25740881.2021.1995422.Search in Google Scholar

Kim, H., Abdala, A.A., and Macosko, C.W. (2010). Graphene/Polymer nanocomposites. Macromolecules 43: 6515–6530, https://doi.org/10.1021/ma100572e.Search in Google Scholar

Lewis, J.S., Perrier, T., Barani, Z., Kargar, F., and Balandin, A.A. (2021). Thermal interface materials with graphene fillers: review of the state of the art and outlook for future applications. Nanotechnology 32: 142003, https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6528/abc0c6.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Li, J.W., Cheng, C.C., and Chiu, C.W. (2024). Advances in multifunctional polymer-based nanocomposites. Polymers 16: 3440, https://doi.org/10.3390/polym16233440.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Mittal, V. (Ed.) (2009). Polymer nanocomposites: advances in filler surface modification and characterization techniques. Nova Science Pub Inc, New York.Search in Google Scholar

Moosa, A.A. and Saddam, F. (2017). Synthesis and characterization of nanosilica from rice husk with applications to polymer composites. Am. J. Mater. Sci. 7: 223–231.Search in Google Scholar

Muller, O., Hege, C., Guerchoux, M., and Merlat, L. (2022). Synthesis, characterization and nonlinear optical properties of polylactide and PMMA based azophloxine nanocomposites for optical limiting applications. Mater. Sci. Eng. B. 276: 115524, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mseb.2021.115524.Search in Google Scholar

Nista, S.V.G., Alaferdov, A.V., Isayama, Y.H., Mei, L.H.I., and Moshkalev, S.A. (2023). Flexible highly conductive films based on expanded graphite/polymer nanocomposites. Front. Nanotechnol. 5: 1135835, https://doi.org/10.3389/fnano.2023.1135835.Search in Google Scholar

Njuguna, J., Pielichowski, K., and Desai, S. (2008). Nanofiller-reinforced polymer nanocomposites. Polym. Adv. Technol. 19: 947–959, https://doi.org/10.1002/pat.1074.Search in Google Scholar

Onthong, S., O’Rear, E.A., and Pongprayoon, T. (2022). Enhancement of electrically conductive network structure in cementitious composites by polymer hybrid-coated multiwalled carbon nanotubes. Mater. Struct. 55: 232.10.1617/s11527-022-02070-zSearch in Google Scholar

Pinnavaia, T.J., and Beall, G.W. (Eds.) (2000). Polymer-clay Nanocomposites. Wiley, Weinheim.Search in Google Scholar

Rahman, M.M., Khan, K.H., Parvez, M.M.H., Irizarry, N., and Uddin, M.N. (2025). Polymer nanocomposites with optimized nanoparticle dispersion and enhanced functionalities for industrial applications. Processes 13: 994, https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13040994.Search in Google Scholar