Abstract

The last four decades have witnessed the flourished harvesting in optical tweezers technology, leading to the development of a number of mainstream and emerging disciplines, particularly in physico-chemical processes. In recent years, with the advancement of optical tweezers technology, the study of particle dynamics has been further developed and enhanced. This review presents an overview of the research progress in optical tweezers from the perspective of particle dynamics. It cites relevant theoretical models and mathematical formulas, delves into the principles of mechanics involved in optical tweezers technology, and analyzes the coupling of the particle force field to the optical field in a continuous medium. Through a review of the open literature, this paper highlights historical advances in research on the dynamical behavior of particles since the invention of optical tweezers, including diffusion, aggregation, collisions, and fluid motion. Furthermore, it shows some specific research cases and experimental results in recent years to demonstrate the practical application effects of the combination of particle dynamics and optical tweezers technology in several fields. Finally, it discusses the challenges and constraints facing the field of combining particle technology with optical tweezers technology and prospects potential future research directions and improvements.

1 Introduction

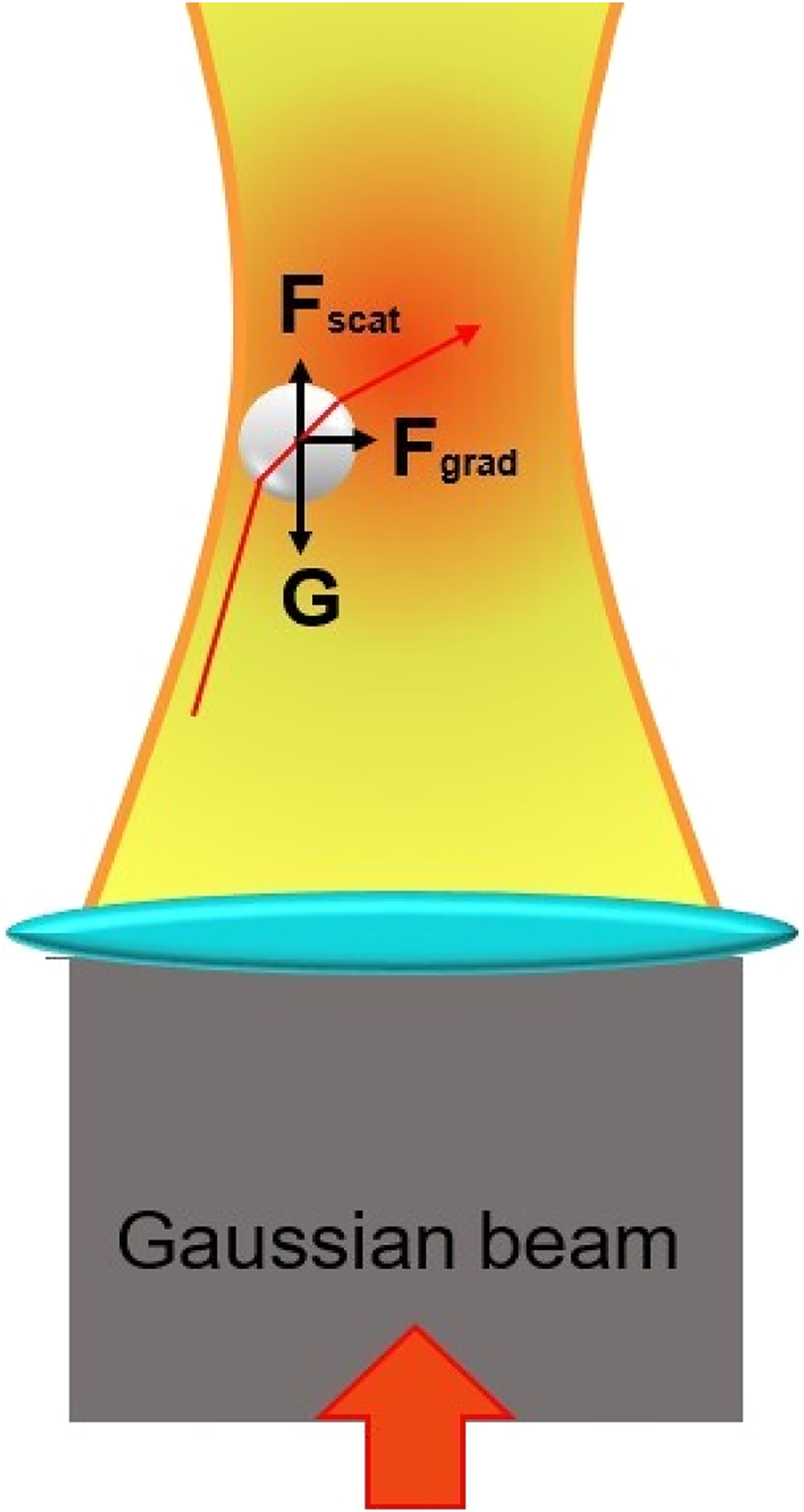

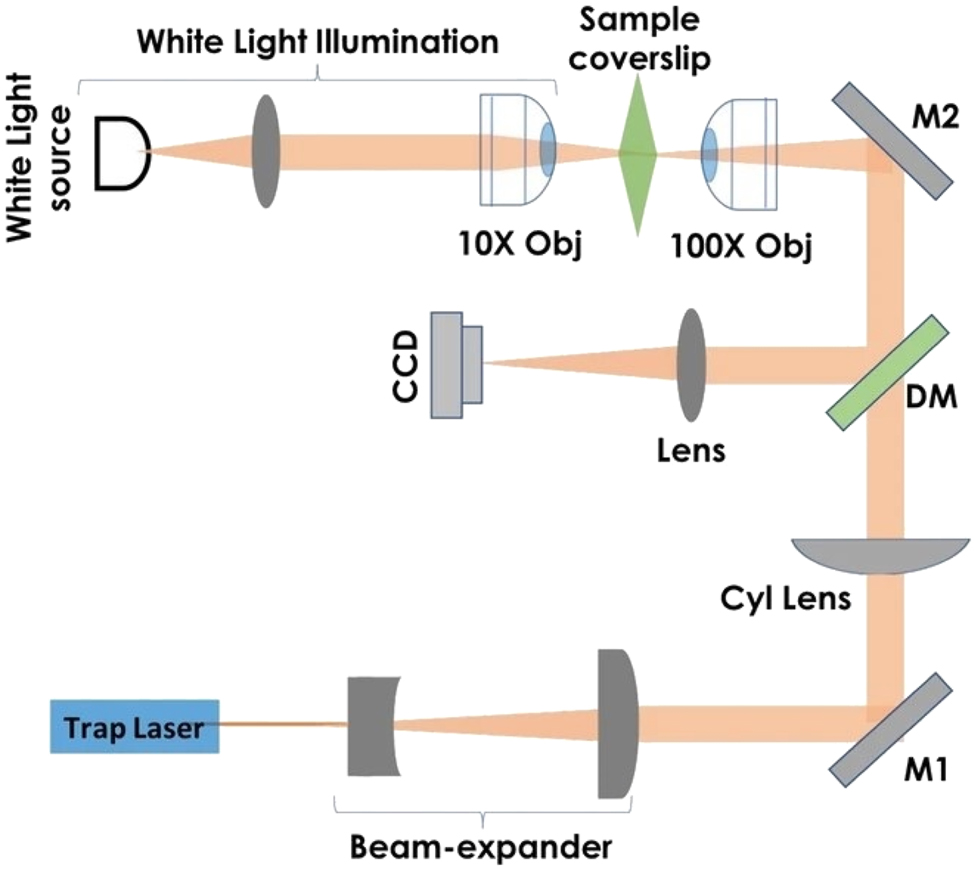

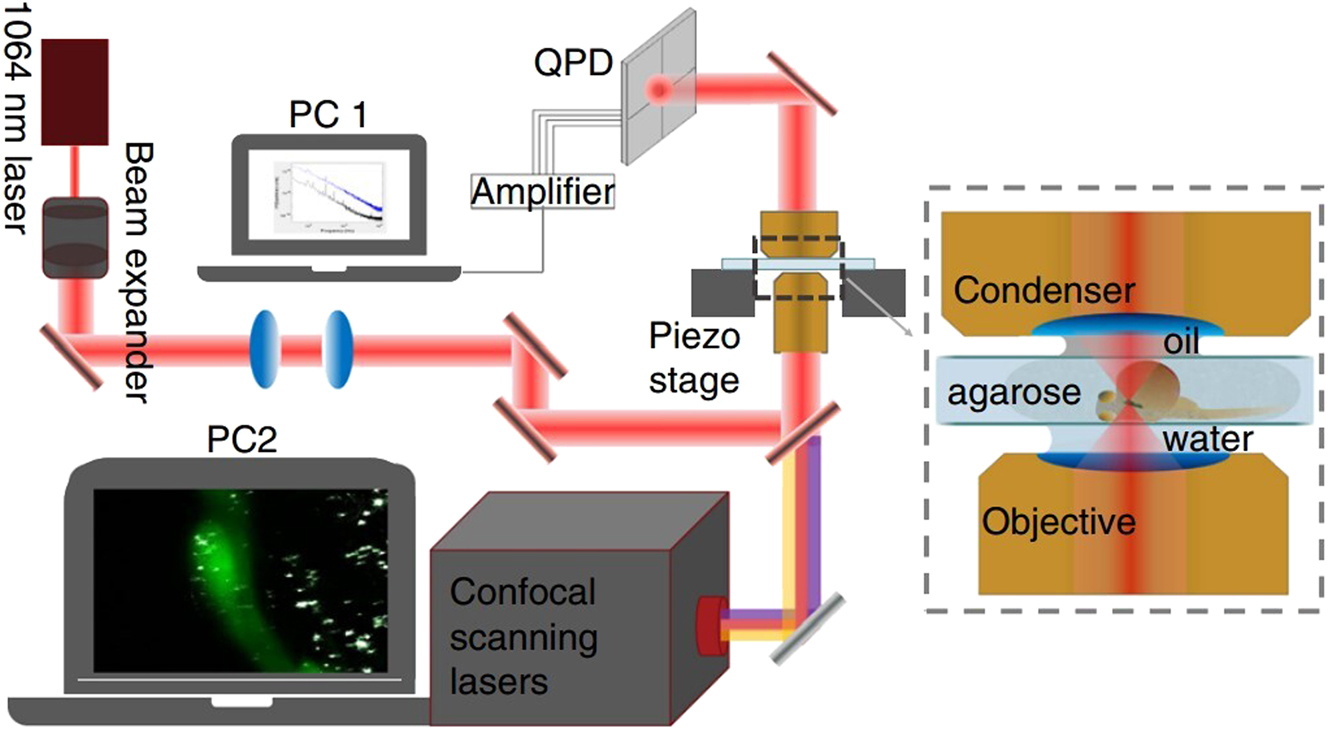

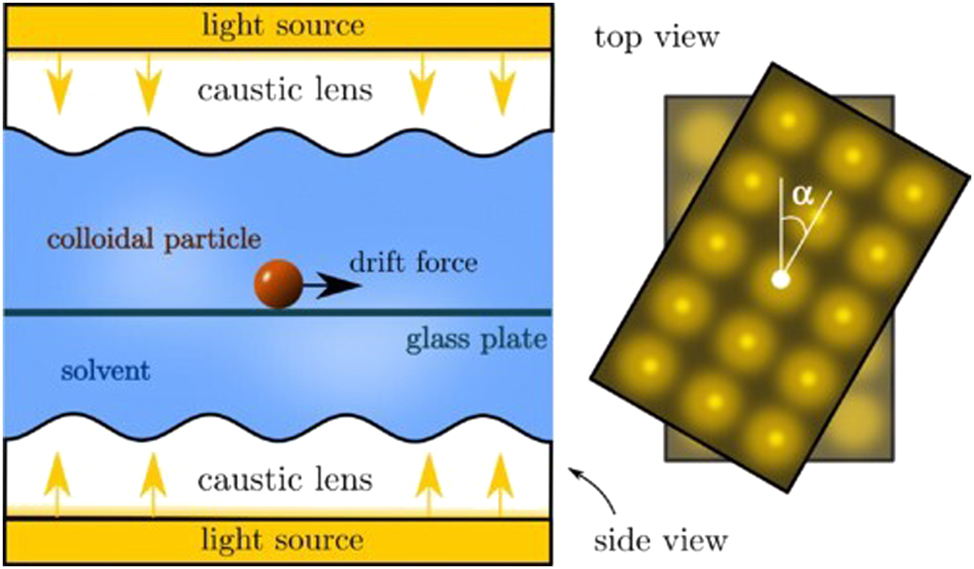

Light is an electromagnetic wave that carries energy and momentum. When light interacts with matter, it transfers not only energy but also momentum (Volpe et al. 2023). This momentum transfer is notable when light interacts with microscopic particles and results in a noncontact mechanical force. Optical tweezer technology leverages this principle to construct a light-intensity gradient potential field in three-dimensional space that can exert a binding force on tiny particles (Min et al. 2020). Unlike conventional physical tweezers that rely on direct contact and mechanical stress to grasp objects, optical tweezers can hold target particles without direct contact. As depicted in Figure 1, due to the spatial variation in light intensity, the particle is attracted to the area of maximum intensity. In a Gaussian beam, gradient force pulls the particle toward the beam’s focus, allowing it to be trapped and stabilized at the beam center. Scattering force is caused by the transfer of momentum from the photons to the particle, pushing the particle along the beam’s propagation direction. Through precise manipulation of a focused laser beam, a light field with an uneven intensity distribution is created around the particles, generating a corresponding optical pressure difference on the particles and thus enabling them to be captured and manipulated by the beam (Polimeno et al. 2018).

Schematic of optical tweezers capture.

The concept of optical tweezers was first introduced in 1970 by American physicist Arthur Ashkin during a series of experiments at Bell Laboratories (Essiambre 2021a,b). He discovered that laser beams could manipulate tiny particles, including smoke and water droplet particles, through the radiation pressure exerted by the beam on these particles. Subsequently, Ashkin used laser beams to capture and manipulate particles such as plastic balls. By 1986, Ashkin and his team had improved the design of optical tweezers to capture living cells without damaging them, thus providing a valuable tool for biological research.

Since their introduction, optical tweezers have seen widespread use and enabled rapid advancements in both physics and biology. They are used to study the dynamics of single molecules, mechanics of cells, mechanical properties and function of DNA, and motion of microscopic objects. In 2018, Ashkin, along with two other scientists, was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics for his distinguished contributions to optical tweezers and laser physics (Asplund et al. 2019). This recognition not only highlights the notable contribution of optical tweezer technology to basic science but also demonstrates its potential applications in various advanced sciences and technologies.

The interaction between light beams and particles or microstructures constitutes the core of optical tweezer technology (Lee and Padgett 2012). The mechanical concepts underpinning optical tweezer technology include the following: light pressure (such as gradient force and scattering force), Newton’s third law of motion, force and acceleration, the dynamic behavior of particles, and fluid dynamic effects. Mechanical analysis can help in understanding the mode and extent of the influence of light forces on particles (Ranha Neves and Cesar 2019); this understanding can help in selecting and adjusting light field parameters, optimizing the layout structure and control algorithm of optical components, and achieving more precise and effective optical tweezer operations (Ciarlo et al. 2024). Particles can be disturbed by various external environmental factors, including hydrodynamic effects and Brownian motion. Mechanical analysis can help evaluate the impact of these disturbances on the system’s stability and enable taking corresponding measures to minimize them.

In summary, mechanics plays a crucial role in optical tweezers technology. In particular, particles under the action of the light field are themselves in the thermal motion environment of a continuous medium. Therefore, mechanical analysis and optimization can improve the accuracy, stability, and efficiency of the manipulation of an optical tweezer system; this can promote the development and application of optical tweezer technology for manipulating microscale and nanoscale objects and in the biomedical field. This review presents the first summary of the development of optical tweezer technology over the past 50 years from the perspective of mechanical and particulate dynamics problems; the review focuses on the interactions between optical fields and mechanical fields related to particles. The rest of this paper is structured as follows. The Section 1 discusses forces acting on particles of different sizes for optical tweezers of different wavelengths and presents the corresponding theories and formulas. The Section 2 introduces novel developments related to the coupling of the particle force field and the optical field in a continuous medium from a theoretical perspective; the effects of the gradient and scattering forces, the self-rotating force, and the stiffness of the optical traps on the particles are comprehensively analyzed. The Section 3 presents validation studies on the diffusion, aggregation, and collision states of particles, in addition to discussing the Navier–Stokes equations of viscous fluid motion in the context of optical tweezers. The Section 4 describes the five major fields of molecular dynamics (MD) application in optical tweezer research: biological cytology, single-molecule biology, materials science, physics, and colloidal science. Finally, on the basis of the reviewed research, the Section 5 combines some research status quo to discuss and look forward to the possibility of further integration, precision, and intelligence in the future in the combination of molecular dynamics and optical tweezers technology.

2 Force analysis of particles in an optical tweezer scenario

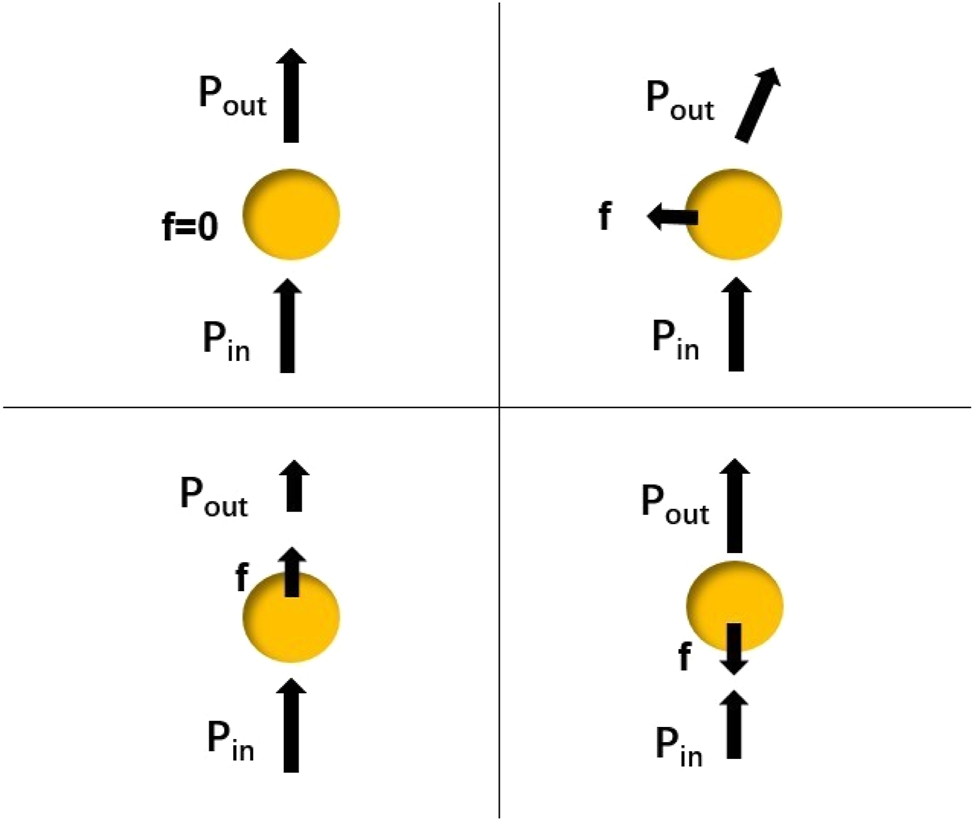

The interaction between optical tweezers and particles is governed by the law of conservation of momentum (Lepeshov and Krasnok 2020). As shown in Figure 2, when a particle is captured at the center of the field, the momentum of the light is not changed and the particle is not subjected to any force (Bowman and Padgett 2013). When the particle moves horizontally or vertically, the momentum of the light changes, and the particle experiences a restoring force. Similarly, when the incident beam changes direction or intensity distribution, its momentum change causes the particle to gain momentum in the opposite direction, producing a restoring force that captures the particle or moves it to the desired position. Essentially, optical tweezers use a high-precision focused laser beam to create a dynamic three-dimensional optical potential well (Singer et al. 2000). This well is used to capture, localize, and manipulate microscopic particles, and its utility depends on the particle size and optical wavelength parameters (Gieseler et al. 2021). The mechanics in three situations with different relative particle sizes and light wavelengths are described as follows.

A simple ray optics model of a particle.

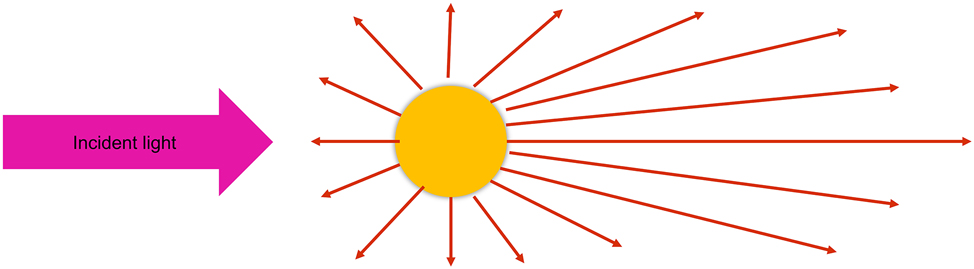

2.1 Particle radius much larger than the light wavelength

As shown in Figure 3, scattering is stronger in the forward direction of light than in the backward direction. Case in this scenario, calculating the forces applied by optical tweezers to a particle, known as a Mie particle, is complex because of the interaction between the light field and the particle (Fontes et al. 2005). This interaction depends on the material, size, and shape of the particle as well as the nature of the light field. The axial optical force exerted on a Mie particle in the path of a Gaussian beam can be calculated using geometrical optics (Campos et al. 2018). When the light beam refracts into the particle’s interior, constant reflection and transmission occur within the particle.

Schematic of Mie scattering for large particles.

The resulting force can be divided into two parts: the scattering force Fs along the direction of beam propagation and the gradient force Fg perpendicular to the direction of beam propagation (Ashkin 1992).

where P1 is the laser power, c is the speed of light in a vacuum, n0 is the refractive index of the medium surrounding the particle, α1 is the angle of incidence, and α2 is the angle of refraction. Moreover, R and T represent the reflectance and transmittance of the particle surface, respectively.

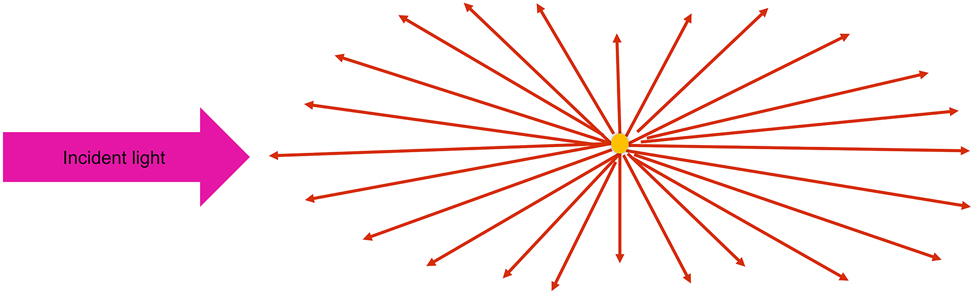

2.2 Particle radius much smaller than the light wavelength

As shown in Figure 4, Rayleigh scattering is symmetrically distributed. In this scenario, forces exerted on a particle, referred to as “Rayleigh particle,” are evaluated (Albaladejo et al. 2009). Rayleigh scattering theory can be used to approximate the forces on the particle (Lenton et al. 2017).

Schematic diagram of Rayleigh scattering of tiny particles.

The particle is considered an induced electric dipole, and its electric dipole moment is expressed as follows (Harada and Asakura 1996):

where a denotes the radius of the particle, nm denotes the refractive index of the surrounding medium, np denotes the refractive index of the particle, and m = np/nm denotes the relative refractive index.

This induced electric dipole experiences the Lorentz force, causing it to oscillate in sync with the external electric field (Bao et al. 2023). This results in the production of secondary scattered waves. When a particle scatters with a photon, it alters the photon’s momentum by a scattering force. This scattering force Fscatt can be calculated using the following equation (Ashkin et al. 1986):

where I0 represents the incident laser light intensity, r represents the radius of the particle, nb represents the refractive index of the medium, and λ represents the incident wavelength.

This formula indicates that the scattering force’s magnitude increases with the laser power, and it is aligned with the propagation direction of the incident light. A particle in the electromagnetic field experiences the gradient force Fgrad (Waterman and Pedersen 1992). This force is a result of the Lorentz force on the induced electric dipole in the electric field. Its magnitude is proportional to the light intensity gradient and is oriented in the same direction as the gradient. Fgrad can be expressed as follows (Friese et al. 1998):

where α represents the polarizability.

2.3 Similar particle radius and light wavelength

In this scenario, a phenomenon involving considerable scattering around particles is considered. The particles experience scattering forces from the light field, subjecting them to optical forces beyond light pressure alone. This particle scattering complicates the shape of the optical potential within the light field, and particles may experience complex forces as they move toward the scattering field’s edge. Hence, a sophisticated theoretical framework is required for this scenario. Several contemporary studies have attempted to describe electromagnetic scattering through numerical calculations of the electromagnetic field. Methods used in such studies include the finite-difference time-domain (FDTD) method (Hu et al. 2022), finite element method (FEM) (Pesce et al. 2020), discrete dipole approximation (DDA) method, and T-matrix method (Polimeno et al. 2019).

2.3.1 FDTD method

The FDTD method is a numerical approach in which Maxwell’s equations are used to solve problems in the time domain. First, space is discretized into a three-dimensional mesh orthogonal to the electric and magnetic field components to ensure that the differential format of Maxwell’s equations is naturally satisfied for the rotation of the electromagnetic field. The center difference method is then used to approximate the updates of the electric and magnetic fields in discrete time steps. Finally, differential operations are performed to determine the values of the electric and magnetic fields at each position and moment. The average force exerted on the particle by the light field can be considered equivalent to the time-averaged force as follows (Benito et al. 2008):

where < > denotes averaging over time, ϵ denotes the vacuum dielectric constant, μ denotes the magnetic permeability, ds denotes the area element, and dv denotes the volume element. The integration is performed over a closed space. Unlike other methods, the FDTD method uses a direct time-domain approach to solve Maxwell’s time-dependent equations. This method does not require conversion to the frequency domain or the use of Green’s function. Because the FDTD method is a direct simulation in the time domain, it is effective for calculating the optical forces exerted on particles that are of arbitrary shape and composition and are illuminated by various light beams (Fan et al. 2016). Additionally, because of its algorithmic nature, the FDTD method is inherently suitable for parallel computing and can be applied in massively parallel implementations, reducing the consumption of computational resources and time. However, this method also has issues such as high computational costs and storage demands for large-scale systems or high-frequency problems, complexities in handling boundary conditions that may introduce numerical errors, and strict stability requirements on the time step (Kuşaf and Öztoprak 2022).

2.3.2 FEM method

In general, FEM entails dividing the entire computational domain into numerous small and simple subdomains, which are typically triangles or quadrilaterals in two dimensions or tetrahedra or hexahedra in three dimensions. The field values are calculated at the vertices of these subdomains and then interpolated across the subdomain by using basis functions (Hafeez and Krawczuk 2023) or shape functions (Xiao et al. 2023). The Maxwell stress tensor

where

FEM can provide accurate numerical simulations for particles of any size, shape, or structure captured by optical tweezers. This method is particularly suitable for large-scale computations of light trapping. However, a higher number of subdomains is associated with a more computationally intensive process. FEM enables researchers to design and optimize optical tweezer traps for various applications in optical manipulation, biophysics, and cell biology (Gao et al. 2019). However, this method involves complex model setup and mesh generation, which can be time-consuming (Mishchenko 2020). Additionally, it has high computational resource consumption for large-scale problems.

2.3.3 DDA method

The DDA method is a numerical simulation approach for calculating the interaction forces between laser light and microscopic particles in optical tweezers (Ling et al. 2010). In this method, particles captured by optical tweezers are considered a collection of dipoles. These particles are divided into numerous smaller cells, each of which is assumed to contain a dipole. The force of the electromagnetic field on each particle is simulated computationally by calculating the interaction between discrete dipoles by using Maxwell’s equations and boundary conditions. The polarization degree of each dipole is determined by the material dielectric constant and the laser wavelength. The polarizability of a dipole, a measure of the dipole’s responsiveness to an electric field, is calculated. The electromagnetic field distribution of the incident light is described using an appropriate source model (e.g., the Gaussian-beam model) (Shchepakina and Korotkova 2013), and the response of a single dipole or an array of dipoles under the action of that incident field is calculated. In this framework, the interaction term can be represented by the Green function G ij (Mkrtchian and Henkel 2020), which describes the propagation of an electromagnetic wave from point j to point i. Finally, Escatter,ij can be calculated as follows:

The interactions between individual dipoles can be calculated using integral equations. Each dipole responds to the presence of a local electromagnetic field in a specific manner. The local electric field Elocal,i is the sum of the incident electric fields Einc and the scattered electric fields produced by all other dipoles (Hoekstra et al. 2001):

Because of the combined effect of the incident field and all other dipole scattering fields, each dipole is affected by the local electric field and thus acquires a dipole moment p i (Draine and Weingartner 1996):

The electromagnetic force F acting on the individual dipoles can be calculated from the electric field on the dipoles and their polarizabilities (Simpson and Hanna 2011):

Owing to the spatial gradient of the laser beam, the dipoles are subject to forces. The total force acting on a particle is the vector sum of the forces acting on each constituent dipole. The DDA method has several advantages, including its suitability for irregularly shaped particles and its flexibility in computations (Yurkin and Hoekstra 2007). However, for larger particles, the required computational resources (such as memory and processing time) increase substantially (Hui et al. 2022). Therefore, it may not be effective for some particles if computing resources are limited. Additionally, it may introduce errors for rough surfaces and complex materials (Loke et al. 2023).

2.3.4 T-matrix method

The T-matrix method can solve light-scattering problems, especially for nonspherical particles. Originally proposed by Waterman (Mishchenko and Martin 2013), a T-matrix can be used to describe the changes that occur when light waves pass through an object, including reflection, refraction, and scattering (Stratton and Chu 1939). The T-matrix is constructed using the boundary conditions of the tangential field component on the scatterer’s surface and the boundary conditions on the particle surface (e.g., the continuity of the electric and magnetic fields) (Nieminen et al. 2011):

where n is the normal vector to the surface of the scatterer. The incident electric field E inc and scattered electric field E scat can be decomposed and expanded into a spherical vector wave function (Ganesh and Hawkins 2010) as follows:

where amn and bmn are the incident field expansion coefficients, fmn and gmn are the scattered field coefficients, and Mmn and Nmn are the vector spherical harmonic functions. In the T-matrix method, the scattering problem is formulated as a boundary value problem; the T-matrix relates the physical behavior of the surface with boundary conditions to that of the far-field scattered waves (Bareil and Sheng 2013):

For capture calculations, the scattering of a given particle under different illumination conditions is repeatedly evaluated. However, the T-matrix does not depend on the position of the particle or the direction of the wave; thus, it must be calculated only once and can then be used to predict scattering characteristics under various conditions (Sekulic et al. 2021). The method enables the precise determination of the scattering and absorption characteristics of particles over the entire wavelength spectrum; by contrast, other methodologies may be applicable only at specific wavelengths or under specific conditions. The method can also be used to investigate the interactions and collective behaviors of particles in multiparticle systems (Wang and Chew 1993). Furthermore, this method is highly accurate for modeling the behavior of particles in complex light fields, such as those exhibiting high-order scattering effects (Cui et al. 2014). The T-matrix method is an approximate approach that relies on specific scattering assumptions, which may not be applicable in all situations. For certain particle geometries, it may be less accurate than FDTD (Mishchenko 2020).

3 Correlation between the particle force field and light field in a continuous medium

The correlation between the particle force field and the light field in a continuous medium can be characterized by the interaction of the gradient force and the scattering force acting on the particles. The gradient force typically arises from refraction and exerts a restoring force that pulls the particle toward the region of highest light intensity as it leaves the center (Nieminen et al. 2007). The direction of the scattering force, generated by the reflection of light, aligns with that of the Poincaré vector, which follows the direction of beam propagation. The balance of these two forces leads to the formation of stable light traps that can be used to manipulate microscopic objects, including dielectric particles (Ali et al. 2020) and living cells. Through this balance, researchers can precisely control the position and kinetic behavior of the particles in the light field, revealing the interactions and responses of the particles. The complexity and interdependence of the interactions between particles and light fields are also closely related to various factors, including the photopressure effect (Lee et al. 2022), laser-induced thermal effect (Geldhof et al. 2022), optical trap stiffness, particle optical properties, particle scattering behaviors in the light field (coherent and incoherent scattering) (Dulin et al. 2015), and dynamic feedback effects that may result from the coupling between the light field and the particles. Some of the related research is summarized in the following sections.

3.1 Gradient and scattering forces

The force exerted on a particle trapped by an optical trap is typically considered to be conservative (Huang et al. 2022a). Nonconservative scattering forces can induce near-negligible toroidal currents for liquids with high resistance. However, the effects in the regime of insufficient suppression remain largely unexplored. Amarouchene et al. from the University of Bordeaux investigated the effects of scattering forces on the nonlinear kinetic behavior of trapped nanoparticles under underdamped conditions at various air pressures. They observed that these forces lead to persistent low-frequency positional undulations (Amarouchene et al. 2019). Their experimental and theoretical results provide a reference for studying the nonequilibrium kinetic behavior of nanoparticles captured by optical tweezers under strong inertial conditions. Huang et al. from East China Normal University also recently revisited the working principle of single-beam optical tweezers and developed a method to accurately calculate these forces for particles in the Rayleigh, Mie, and geometrical optics regimes. They introduced a new concept, namely “light-trapping nucleus”. This concept states that considering particles of all scales, a particle can be stably trapped only if the conservative force in the light-trapping core region centered on the beam center exceeds the nonconservative force in this region. This suggests that the properties of the light-capturing core can be altered by adjusting the light-throwing conditions (e.g., the beam intensity, shape, and polarization state) or the properties of the particles (e.g., size, shape, and refractive index), enabling more effective and precise optical manipulation of the particles.

3.2 Self-rotating forces

Aloufi et al. from King Saud University recently analyzed the interaction between a dielectric particle and a highly concentrated circularly polarized Largangiad Gaussian beam; they focused on Rayleigh particles with sizes smaller than the light wavelength as well as the longitudinal components of the electric and magnetic fields within the beam (Aloufi et al. 2023). Their comprehensive analysis of the longitudinal components in the light field revealed that the presence of a longitudinal term significantly affects the polarization gradient in the light field. They observed that the coupling of spin angular momentum and orbital angular momentum engenders a non-negligible rotational force Fspin(r) that is comparable to the gradient and scattering forces; it can be expressed as follows:

where α″ is the part of the complex polarizability, σ is the spin of the light beam, ℓ is the winding number, ρ is the radial index, k = 2/λ, u, and Θ are the functions in a Laguerre–Gaussian mode. Although considered negligible in many studies, this self-rotational force can substantially affect the dynamics of particles trapped in optical tweezers.

3.3 Optical trap stiffness

For conventional optical tweezers, optical trap stiffness affects the balance of scattering and gradient forces required for stable trapping and manipulation (Sarshar et al. 2014). Optical trap stiffness indicates the balance between the gradient force and viscous drag; these comprise a restoring force that can be modeled with Hooke’s law F(x) = −kx, where k is the optical trap stiffness (Wulandari et al. 2021). To ensure light trap stability, the gradient force must overcome other forces, such as scattering forces, buoyancy forces, and Brownian motion. Specifically, a light trap with a higher stiffness level is more capable of manipulating the particle, resisting scattering forces, and maintaining the particle in a stable position.

Studies on standardizing optical trap stiffness have mostly focused on the stiffness calibration of continuous-wave optical tweezer systems. However, the precise calibration of optical trap stiffness for femtosecond optical tweezer systems, which fully utilize nonlinear optical effects, has received less attention. Mondal et al. from the Indian Institute of Science detailed the development of novel light-sheet optical tweezers (LOTs) (Mondal et al. 2022). As shown in Figure 5, LOTs differ from conventional optical tweezers because they use a diffraction-limited light sheet, enabling the simultaneous trapping and manipulation of multiple microscopic particles and living cells in the transverse plane. In calculating the trap stiffness, they associated the gradient force F(x) = −kx with the viscous force Fvis = −6πηr b v acting on particles moving in the fluid:

where v is the drag velocity, x is the displacement, η is the medium viscosity, and rb = d/2 is the radius. Although the trap stiffness of an LOT is lower than that of a conventional point optical tweezer, it is suitable for applications requiring mild optical forces.

Schematic of the developed lightsheet optical tweezer (LOT) system (Mondal et al. 2022; reproduced with permission from Springer Nature).

Femtosecond laser pulses are extremely short, making it difficult for traditional methods to capture rapid particle movements accurately in real-time, leading to potential calibration errors (Xu et al. 2023). The high intensity of femtosecond lasers can cause nonlinear effects like multiphoton absorption, altering the optical trap’s behavior and complicating stiffness calibration (Vorobyev and Guo 2013). Laser-induced temperature fluctuations can change the fluid’s viscosity, affecting particle resistance and introducing inaccuracies in stiffness measurements (Zhu et al. 2024). Local heating and scattering forces influence particle behavior, especially for small particles, making calibration more complex. These challenges require advanced techniques and careful experimental design to achieve reliable calibration.

On the basis of the mature theoretical model of the continuous-wave optical tweezer system, the Li Yue Corps team from the Minzu University of China successfully constructed a new theoretical model applicable to femtosecond optical tweezer systems (Li et al. 2024). Using the model and numerical simulation techniques, they calculated and comprehensively analyzed the optical trap stiffness for a gold particle with a diameter of 60 nm under various laser power conditions. In this model, the polarization strength of the particle can be expressed as follows (Huang et al. 2020):

where ε0 is the permittivity of free space, E is the electric field of light, χ1 and χ3 represent the first-order linear and third-order nonlinear polarizabilities of the captured particles, respectively, and I represents the electric field strength. This pioneering work provides a strong theoretical basis for investigating the dynamic mechanical properties of particle capture and manipulation by ultrashort pulsed lasers.

In an optical trap, the optical trap stiffness is usually proportional to the polarization strength of the particles (Lee et al. 2012). Specifically, as the intensity of the beam increases, the polarization strength of the particles increases, which causes the stiffness of the optical trap to increase as well. This is because a stronger beam produces a larger optical potential energy gradient, which exerts a greater restoring force on the particle (Chen et al. 2023). On the other hand, an increase in polarization strength means that the particles respond more strongly to the light field, and thus the overall stiffness of the light trap increases (Madadi et al. 2012). Thus, the polarization strength of the particles is an important factor affecting the stiffness of the optical trap. Overall, the relationship between the polarization strength of a particle and the stiffness of the optical trap is positively correlated, and increasing the polarization strength enhances the stiffness of the optical trap, making the optical trap more constrained to the particle.

4 Particle dynamics in optical tweezer systems

Optical tweezers can manipulate particles or fluids in microfluidic systems. They enable precise manipulation and localization, enable accurate measurements, facilitate simulations of confined environments, and enable real-time observation and monitoring, thus facilitating the study of processes such as particle diffusion, aggregation, and collision. Such studies can reveal kinetic behavior during Brownian motion and the complex behavior of fluids at the microscopic scale.

4.1 Particle diffusion

In 1986, American physicist Arthur Ashkin successfully manipulated tiny dielectric particles for the first time by using single-beam gradient force optical tweezers. He observed the motion of the particles in the light field, including Brownian motion. This pioneering work laid the foundation for the use of optical tweezer technology in particle diffusion research.

4.1.1 Diffusive behavior observed by early optical tweezers

In the early 2000s, researchers began studying the diffusion of particles by using optical tweezers. For example, in 2000, Lin et al. from the University of Chicago conducted an experiment to measure the constrained Brownian motion of an isolated sphere between two walls. They observed the diffusive motion of the sphere particles when they were hindered by the light field without interference from precipitation or electrostatic forces. The diffusion coefficients obtained from the experiment validated the use of fluid dynamics for predicting wall drag effects (Lin et al. 2000). In the same year, Wei et al. from the University of Konstanz, Germany, confined particles in a one-dimensional channel generated by scanning optical tweezers to study single-row diffusion of colloids (Wei et al. 2000). They observed that the self-diffusive behavior of the particles was non-Fickian for a long time, whereas the distribution of particle displacements was a Gaussian function. In 2002, Bubeck et al. used ring optical tweezers to study the behavior of magnetic colloidal particles in a two-dimensional circular hard-walled cavity. They found that the short-time diffusive behavior was unaffected by the presence of laser tweezers, and the angular diffusion of particles aligned in a shell layer was highly anisotropic and nonmonotonic (Bubeck et al. 2002). In 2004, Lutz et al. used scanning optical tweezers and observed that particles undergo a transition from normal diffusion to single-file diffusion (SFD), where they move through a narrow aperture and cannot pass each other, in the absence of adherent hydrodynamic conditions on the side confining walls. They determined that the mean-square displacements of the particles exhibit a t1/2 behavior and that the activity of SFD decreases with increasing particle density (Lutz et al. 2004). This finding is useful for understanding SFD and can be used to study catalytic reactions in zeolitic materials.

Early research mainly focused on validating the theory of Brownian motion, exploring the relationship between forces acting on the particles and their diffusion properties, and revealing anisotropic diffusion behavior (Pérez-García et al. 2023). Despite some progress already made, most early studies were conducted in ideal fluids. However, in more complex media (e.g., non-Newtonian fluids or biological environments), particle diffusion becomes more complicated, and this area remains largely unexplored. Meanwhile, in high-intensity laser fields, nonlinear optical effects (such as multiphoton absorption) can alter the shape of the optical trap and thus affect diffusion behavior. These effects were not fully understood or quantified in early studies (Mousavi et al. 2017).

4.1.2 Diffusion in biology

Two years after the development of optical tweezers, researchers started using them to study particle diffusion behaviors in the field of biology. For example, in 2006, Munteanu et al. from Denmark used optical tweezers and power spectroscopy to study subdiffusion phenomena for cytoplasmic and lipid particles of dividing yeast (Munteanu et al. 2006). They observed that subdiffusion was not primarily caused by actin fibers in the cytoplasm but by other membrane structures. This provided insights into the behavior of particles in living cells and actin networks. In 2009, Snijder-Van As et al. from New Zealand combined optical tweezers with total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy to study cell adhesion and membrane protein dynamics (Snijder-Van As et al. 2009). Their measured cell spreading was in excellent agreement with existing theoretical models. In the same year, Andreas Biebricher et al. from France used optical tweezers to precisely control DNA extensibility; they determined that slight overstretching of DNA led to a significant decrease in the diffusion constant of the enzyme (Biebricher et al. 2009). This demonstrates that combining optical tweezers and fluorescence tracking is a powerful tool for studying enzyme transfer along DNA. In 2012, Guo et al. from the United States used optical tweezers to observe that the diffusive movement of microinjected inert particles in living cells was due to active motion-based stress fluctuations in an elastic medium (Guo et al. 2012), further expanding the study of dynamics in living cells.

4.1.3 Microrheology and colloid science

In 2012, Julian Kirch from Germany used optical tweezers to reveal the relationship between the microstructure of lung mucus and the microscopic diffusion behavior of nanoparticles (Kirch et al. 2012). He found that in mucus, the mobility of particles depends on the size of the localized pores. This discovery filled in the missing link between microrheology and macroscopic observations about particle mobility in mucus. The following year, Shindel’s static experiments revealed that captured particles passively diffuse within the harmonic potentials of optical tweezers (Shindel et al. 2013). This enabled the calibration of capture and detection devices and the measurement of linear viscoelasticity, indicating a new area of research in the combination of rheology and colloid science.

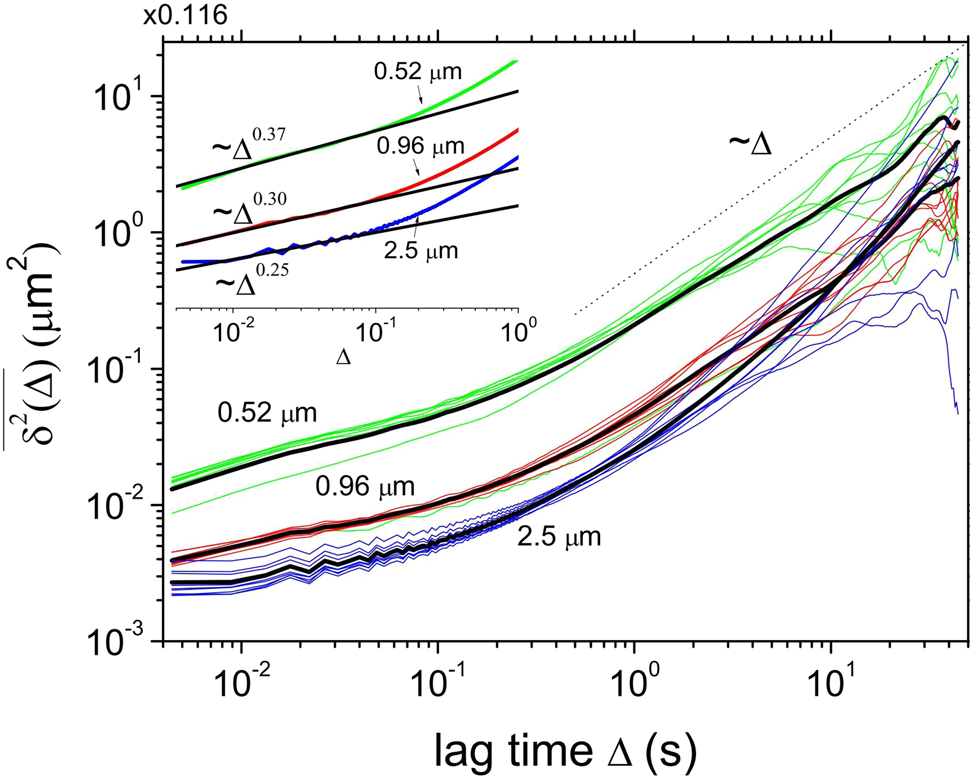

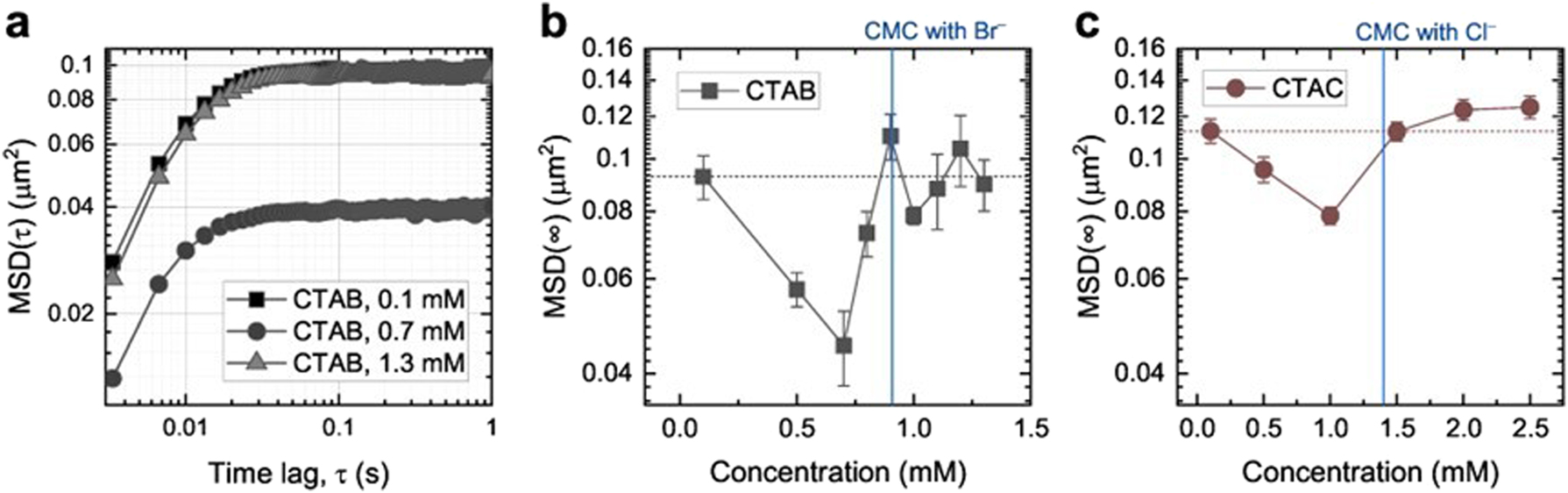

By 2013, researchers were using optical tweezers to study the diffusion behavior of particles in composite fluids. Jeon et al. from Denmark used optical tweezers and video microscopy techniques to track the diffusion behavior of micron-sized beads in worm-like micellar solutions (Jeon et al. 2013). As shown in Figure 6, the relaxation kinetics of beads captured by optical tweezers exhibited power-law decay, whereas the free diffusion of beads observed in video microscopy experiments exhibited subdiffusion with an exponent of approximately 0.3. The anomalous diffusion behavior of the beads is consistent with the behavior predicted by the fractional Langzhiwan equation. They further hypothesized that the normal and superdiffusive motions observed over longer periods may be related to the viscoelastic properties of the micellar solution.

TA MSD curves

4.1.4 Comparison of experiment and theory

Researchers have continually compared and validated experimental results with theoretical models. In 2013, Ha et al. from Pusan National University, South Korea, tested the Einstein–Stokes relational equation from a unique perspective; specifically, they employed oscillating optical tweezers to measure the viscous friction coefficient β in the relational equation, a task that was previously deemed difficult. The diffusion coefficient D was determined using the positional tracking method. The final experimental results aligned with the prediction of the Einstein–Stokes relation (Ha et al. 2013). In 2014, Pesce et al. performed experiments with standard optical tweezers, but they were limited to short timescales because of the cutoff of free particle diffusion (Pesce et al. 2014). They then used scintillation optical tweezers to measure inertial effects on timescales of up to a few seconds; they discovered that the particles’ mean-square displacements deviated from Einstein–Smoluchowski theory and diverged over time. These results were noted to be consistent with the generalized theory of fluid inertia around the periphery and demonstrated for the first time that the error in the diffusion coefficient estimation grows polynomially, not exponentially, with time. In 2016, Tränkle et al. used scanning-line optical tweezers and interferometric particle tracking to track the motion of individual particles with high precision (Tränkle et al. 2016). They measured the diffusion coefficients of two coupled particles at varying distances from one or two glass interfaces. They determined that the coupling length decreased as the second particle diffused nearby. The presence of nearby surfaces and interaction potentials both reduced diffusivity but did not significantly affect the contact time between the particles or the binding probability. The experimental results were in good agreement with the theoretical model.

Optical tweezers can affect the diffusion coefficient of particles in a solution by manipulating and regulating the particles. The diffusion coefficient describes the particles’ ability to diffuse freely in the solution and is typically given by the Stokes–Einstein equation. Optical tweezers can localize, manipulate, and control the particles, thus influencing their diffusion behavior and the overall diffusion coefficient of the solution. In 2017, Mousavi et al. proposed a nonlinear method to reconstruct the equation of motion of particle dynamics in optical tweezers (Mousavi et al. 2017). All functions and parameters of the dynamics could be directly determined from the measured sequences. Their study was the first to determine the spatial dependence of the diffusion coefficient of particles in a light trap, contrary to the main assumptions of the power spectrum calibration method commonly used in previous experiments. They demonstrated that the diffusion coefficient of the particles is not usually constant.

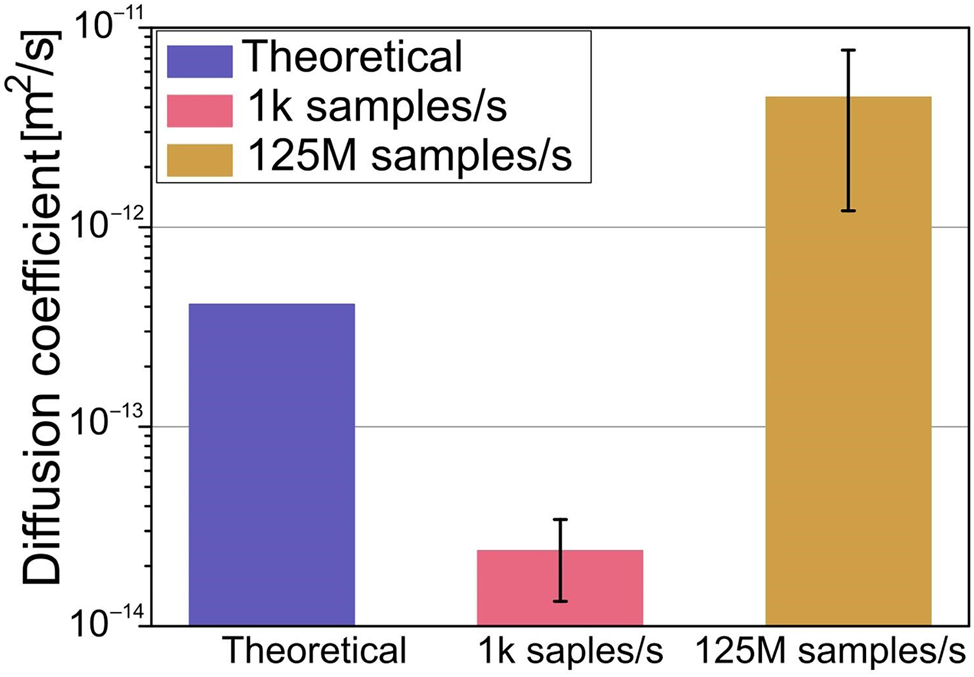

In recent years, the number of teams researching MD by using optical tweezers has increased. However, most of these teams have focused on theoretical studies; fewer have conducted experiments (Wu 2023). Zembrzycki et al. from the Institute of Fundamental Technologies of the Polish Academy of Sciences used LAMMPS software to conduct large-scale simulations of the Brownian motion of charged colloidal 50-nm particles in optical tweezers. They investigated the four most commonly used water models in MD and compared their results with experimental measurements at the same timescale (Zembrzycki et al. 2023a). They proposed a method for directly comparing the diffusion of colloidal polystyrene particles in MD simulations with experimental data on the same timescale in the ballistic state. The characteristic time τ of the ballistic state can be calculated as follows:

where m is the particle mass, mf is the mass of the fluid displaced by the particle as it moves, γ is the coefficient of friction, η is the dynamic viscosity of the fluid, and R is the particle radius. To simulate the effect of a light trap, they applied a harmonic force to the center carbon atom of the particle. At this point, the equation for the position of the particle is as follows:

where x is the position, t is time, kB is Boltzmann’s constant, T is temperature, and W(t) is white noise. They performed experimental measurements for an optical tweezer system with an acquisition rate of up to 125 MHz and determined the particle behavior. Considering electrostatic interactions, they compared the experimental and numerical simulation results for a freely moving particle at three potential field strength levels; they revealed that the results were consistent in Figure 7. Specifically, the diffusion coefficient in the ballistic state increased with the acquisition rate of the optical tweezers. Although the models were limited to simplified simulations in a two-dimensional plane, they provide valuable insights for subsequent ideal simulations and experimental measurements.

Measured diffusion of 1 μm polystyrene particle in an optical tweezers system with a 1 pN/nm trap stiffness, along with theoretical calculations for a freely moving particle (Zembrzycki et al. 2023a; reproduced with permission from MDPI AG).

Recently, Pangeni et al. from the United States combined optical tweezers and coarse-grained MD simulations to study the diffusion migration of individual replication protein A molecules on single-stranded DNA under varying tension conditions by using single-molecule confocal fluorescence microscopy (Pangeni et al. 2024). They concluded that the diffusion coefficient was highest when the tension was 3 pN and KCl concentration was 100 mM, but it decreased significantly at higher tension or salt concentrations.

4.1.5 Factors influencing proliferation behavior

Researchers also began to focus on factors influencing the diffusive behavior of particles since 2008. For example, in 2008, Evstigneev et al. from Germany investigated the diffusion of colloidal particles in a tilted periodic potential created by rotating optical tweezers (Evstigneev et al. 2008). They observed that the velocity of the particles and the diffusion coefficient as a function of rotational frequency were consistent with theoretical predictions. In a periodic potential, the diffusion of individual colloidal particles can become arbitrarily large, and the presence of geometrical constraints reduces the diffusion coefficient. They also determined the parameters of the experimental laser potential and the free thermal diffusion coefficient of the colloidal particles. Their study provided a quantitative theoretical explanation for the diffusion enhancement observed in previous experiments. In 2011, Lele et al. calculated the diffusion tensor for motion parallel to the walls of each ensemble by analyzing thousands of particle trajectories generated by holographic tweezer scintillation and dynamical simulations; they ultimately concluded that the diffusion behavior depends on the relative magnitude of the distances between the ensemble and the walls as well as the separation between particles (Lele et al. 2011).

Recently, Sushil Pangeni’s team at Johns Hopkins University, while studying the diffusional migration of individual RPA molecules on ssDNA under tension, found that the diffusion coefficient D was highest at 3 pN tension and 100 mM KCl with the aid of a single-molecule confocal fluorescence microscope coupled with optical tweezers and coarse-grained molecular dynamics simulations and decreased significantly when tension or salt concentration increased. Salt concentration increased significantly (Pangeni et al. 2024).

4.2 Particle aggregation

Optical tweezers can localize particles to a specific region in liquid or gas if the light beam’s focus and intensity are adjusted. They can precisely measure the interaction force between the particles and the degree of particle aggregation and can thus enable controlling the particle aggregation process in experiments. Moreover, they can simulate particle aggregation behavior in a controlled microenvironment. High-resolution microscopes and imaging systems can enable the real-time monitoring of particle aggregation states to understand the dynamics of the aggregation process and the mechanisms of particle interactions. In 2008, Laura Mitchem et al. used a single-beam gradient force light trap to optically process and characterize aerosol particles. They conducted a detailed study of the dynamics of particle transitions, in addition to studying the nature of the interparticle forces and coalescence (Mitchem and Reid 2008).

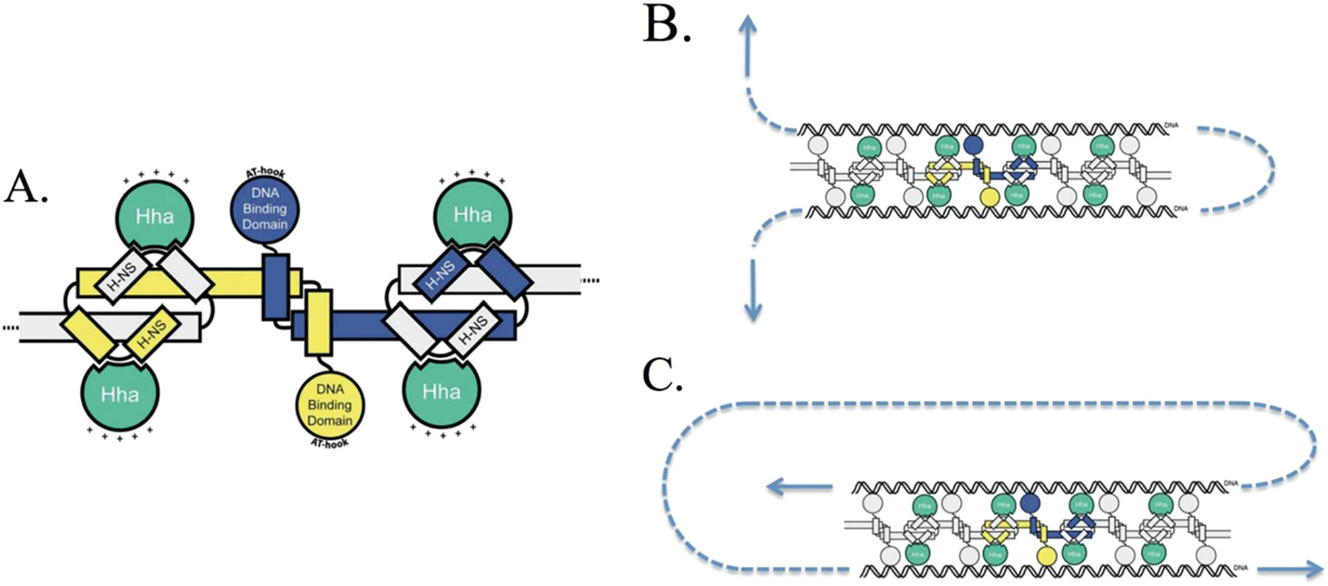

4.2.1 Single-molecule condensation

The exploration of particle aggregation or coalescence using optical tweezers is a relatively new field that was initially focused on single molecules. In 2007, Singer et al. from Australia demonstrated the use of optical tweezers to gather single molecules. Their experiments showed that optical tweezers could control and increase the concentration of polyethylene oxide molecules in a specific area; the trapping potential allowed the molecules to accumulate (Singer et al. 2007). By adjusting the trapping power, they could control the concentration of the molecules, and they confirmed that optical gradient forces are the primary mechanism for trapping polyethylene oxide molecules. This breakthrough led to the application of optical tweezers in the field of biology. In 2010, Landry et al. from the United States discovered that the TelK enzyme’s binding to DNA is a highly tension-dependent process that condenses the molecule by several nanometers (Landry et al. 2010). They observed this condensation even on nonspecific DNA. In 2014, Wang et al. from Canada observed that tension induced by optical tweezers leads to rapid DNA compaction, except in the presence of the nuclear-like structural protein H-NS alone. As shown in Figure 8, this finding demonstrates that coagulation may be triggered by the level of mechanical tension experienced along different regions of the chromosome (Wang et al. 2014).

Schematic representation of the effect of external forces on the complex. (A) Schematic of an H-NS oligomer in complex with Hha (the positively charged surface of Hha is indicated by “+”). (B) By dissociating one protein at a time, this bridging configuration should be relatively sensitive to an applied force (indicated by the arrows). (C) An alternative orientation that would be much more stable to dissociation by an applied tension (Wang et al. 2014; reproduced with permission from Oxford University Press).

4.2.2 Aggregation of red blood cells

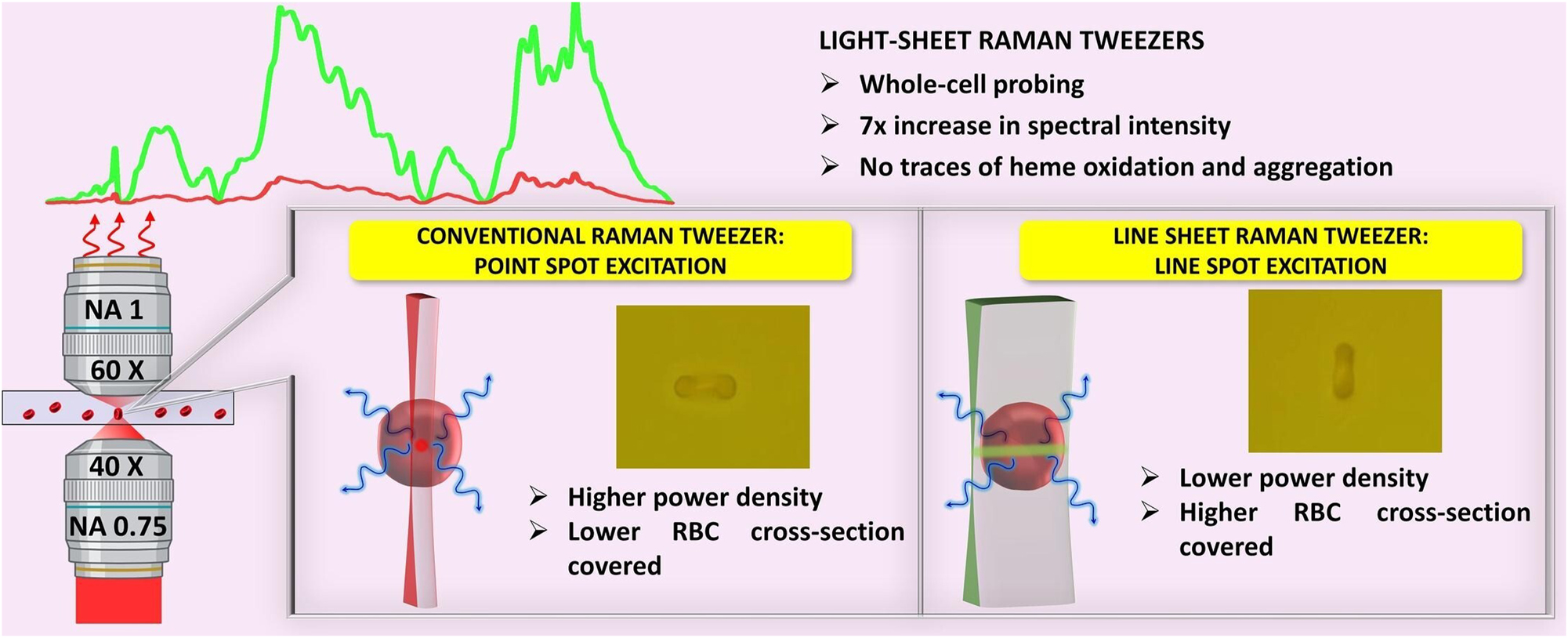

Optical tweezer technology offers a precise, real-time, and controlled method for studying the cohesion of red blood cells (RBCs), providing insights into their interactions and cohesive behavior. In 2012, Khokhlova et al. from Russia used double-trapped optical tweezers to measure the aggregation forces between RBCs in blood samples collected from healthy individuals and patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) (Khokhlova 2012). They observed significant differences in the cell aggregation rate and behavior between healthy and SLE blood samples. The aggregation force between RBCs depended on the distance between their centers and exhibited threshold behavior, and SLE blood samples had both higher aggregation forces and tighter erythrocyte rolling bodies (rouleaux). This discovery paved the way for using optical tweezers to monitor SLE and its response to drug therapies at the single-cell level. In 2013, Fernandes et al. from Brazil also used dual optical tweezers to measure erythrocyte aggregation force; they determined that erythrocytes diluted in an enhancer solution did not agglutinate in the absence of erythrocyte antibodies (Fernandes et al. 2013). In 2016, Lee et al. from Finland reported that the shear stress required to break down a pair of RBCs using dual-channel optical tweezers prevented erythrocyte aggregation (K. Lee et al. 2016). In the same year, they also discovered that spontaneous aggregation and depolymerization in a pristine-like medium are complex processes controlled by different interaction mechanisms (Kisung Lee et al. 2016). Their research provides insights into blood microcirculation processes and contributes to future monitoring and therapeutic advances. Recently, Jayraj et al. from India developed a light-sheet Raman tweezer system that combines optical tweezers with Raman spectroscopy for whole-cell biochemical analysis of RBCs (Jayraj et al. 2024). As shown in Figure 9, this system enabled the analysis of individual functional RBCs in a natural physiological environment; they directly demonstrated the potential of using optical capture and Raman spectroscopy (Jin et al. 2023) to study biochemical changes caused by cellular pathologies.

Light-sheet Raman tweezers for whole-cell biochemical analysis of functional red blood cells (Jayraj et al. 2024; reproduced with permission from Elsevier).

4.2.3 Gold and silver nanoaggregates

Optical tweezers can measure piconewton forces at the nanometer to micrometer scale and are thus suitable for investigating the dynamics of nanoparticle coalescence, particularly for gold nanoparticles (GNPs) and silver nanoparticles. In 2009, Tong from Sweden combined optical tweezers and microfluidics to overcome the challenges of uncontrolled aggregation in metal colloids; their study thus provided the foundation for a new type of lab-on-a-chip-based plasma chemical (Wang et al. 2023) or biological sensors (Tong et al. 2009). In 2010, Kumar et al. from India used asymmetric beams with inhomogeneous intensity distributions to measure piconewton forces in single-beam optical tweezers for the three-dimensional multitrapping of dielectric polystyrene beads and GNPs. They determined that the laser’s interaction with GNPs enhanced the localized surface plasmon resonance field around the GNPs, leading to remote aggregation of polystyrene beads (Kumar et al. 2010a,b); this finding has potential applications for micrometer and nanometer connectors. In the same year, they combined an optical interferometer unit with a conventional optical tweezer system to achieve simultaneous multiple capture and micromanipulation of monodispersed polystyrene spheres and single-walled carbon nanotubes aggregated in small floating clusters (Kumar et al. 2010a,b). The following year, they observed that optical tweezers embedded with a spatially featured asymmetric (SFA) laser beam with an intensity gradient could be used with sufficiently low power to capture and aggregate multiple GNPs at plasma excitation wavelengths (Kumar et al. 2011).

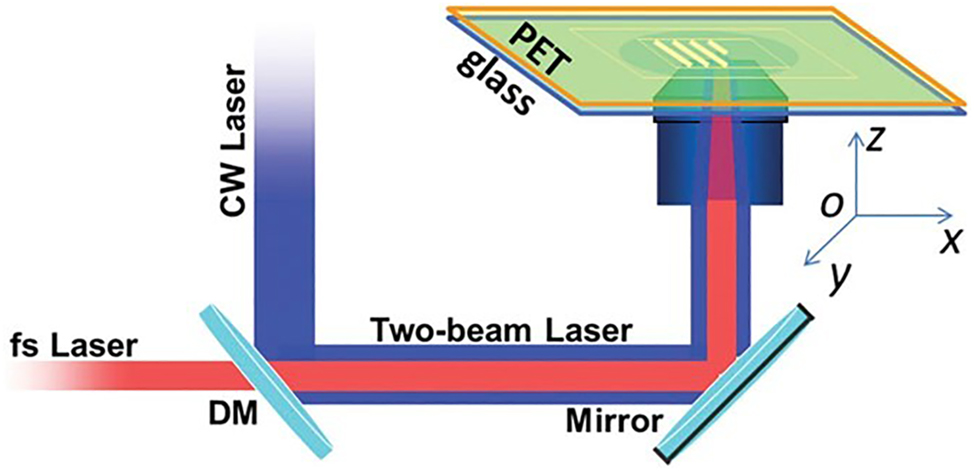

In 2017, He et al. from the Chinese Academy of Sciences used a continuous-wave laser as optical tweezers. As shown in Figure 10, when the gradient force was greater than the scattering and absorption forces, the light-trapping force caused silver nanoparticles to aggregate into a continuous silver nanowire that was both highly flexible and had stable resistivity (He et al. 2017). This method suggests new applications for dual-beam laser processing technology. In 2019, Kitahama et al. from Japan reported that the spatial fluctuations of molecules on silver nanoaggregates were suppressed by increasing the laser intensity of plasma-enhanced optical tweezers (Kitahama et al. 2019). This enhancement could further improve the safety and effectiveness of nanotechnology in medicine, photothermolysis, and surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (Li et al. 2021).

Schematic of the two-beam laser fabrication technique experiment setup (He et al. 2017; reproduced with permission from AIP Publishing).

4.2.4 Droplet aggregation

Optical tweezers have become an ideal tool for studying liquid aggregation because they can manipulate droplet particles of smaller sizes than those in other experiments. In 2019, Otazo et al. precisely manipulated the solid-state content in cream droplets through combined control of optical tweezers and temperature; this affected their properties and behavior (Otazo et al. 2019). The major finding of this study is the identification of a relationship between the adjusted solid-state content and the aggregation state of the cream droplets. As the solid-state content decreased, the coalescence state of the cream droplets gradually changed from partial coalescence to complete coalescence.

In 2020, Zhai et al. from Tianjin University discovered that droplet generation through optical tweezers involves two phases: “trapping” due to the optical force field and “aggregation” resulting from photothermal phenomena and thermal acceleration (Zhai et al. 2021). Concurrently, Chen et al. from Tsinghua University introduced a novel method to examine the interaction of polymer-stabilized micron-sized oil droplets using optical tweezers. They employed a numerical model to overcome the inapplicability of the atomic force microscopy (AFM) for the small forces measured with optical tweezers. The model was used to derive the repulsive pressure and establish a quantitative relationship between the measured force and the droplet separation distance (Chen et al. 2020). Their study provided valuable insight into the interaction mechanisms between micrometer-scale droplets and presents a new approach for quantitative force measurement in emulsion systems.

In 2021, Aarøen from the Norwegian University of Science and Technology combined optical tweezers and MD to investigate the interactions that trigger and enhance aggregation between oil-in-water emulsion droplets (Aarøen et al. 2022). He considered the impact of approach velocity and droplet size on the work required for separation and the coalescence time in unstabilized, pristine emulsion droplets. He also explored the influence of ions on the production, handling, and use of emulsions in optical traps. His contraction–extension scheme revealed that stable and typically larger droplets exhibit a sharper peak at a separation cutoff; this peak can be directly labeled as the depletion power. Furthermore, stable emulsion droplets had a longer aggregation time and approached at a fixed, lower velocity. In 2022, Tanaka et al. from Japan discovered that particles are absorbed into microdroplets formed by optical tweezers in thermoresponsive ionic liquids or water mixtures and that droplet contraction leads to the aggregation of colloidal particles (Tanaka et al. 2022). These findings have provided the groundwork for future studies on droplet interactions.

4.3 Particle collisions

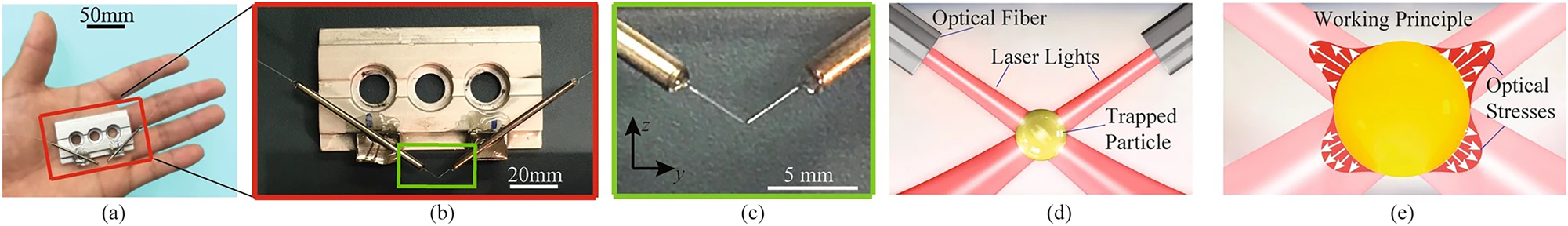

Studies on nanoparticle collisions using optical tweezer technology have focused on the precise manipulation and localization of nanoparticles through the use of optical fields and the subsequent real-time observation and monitoring of particle collision processes. These studies have provided crucial information for understanding the interactions and dynamic behaviors between nanoparticles, paving the way for a wide range of applications in various fields.

4.3.1 Collision–adhesion dynamics

Optically controlled collisions initially became popular for adhesion studies in the 1990s. In 1996, Mammen et al. from Harvard University used dual optical tweezers to control the collision of two medium-sized particles and assessed the adhesion probability between a single RBC and a single virus-coated microsphere (Mammen et al. 1996). In 2007, Xu and Sun from the Chinese Academy of Sciences employed a computerized method to more comprehensively explore the collision–adhesion dynamics of two particles confined in an optical trap; they considered various factors, including particle interactions, hydrodynamic interactions, optical trapping forces, and Brownian motion (Xu and Sun 2007). Their simulations demonstrated that the method of measuring adhesion probabilities using optical tweezers is applicable to various types of interactions and that the tweezer stiffness has minimal impact on the results. They also revealed that the transition from the compact to the relaxed state is associated with a change in the mutual positions of the particles and the direction of the laser beam. The relaxed state corresponds to the particles staying in separated equilibrium positions and is associated with a lower collision frequency compared with the compact state.

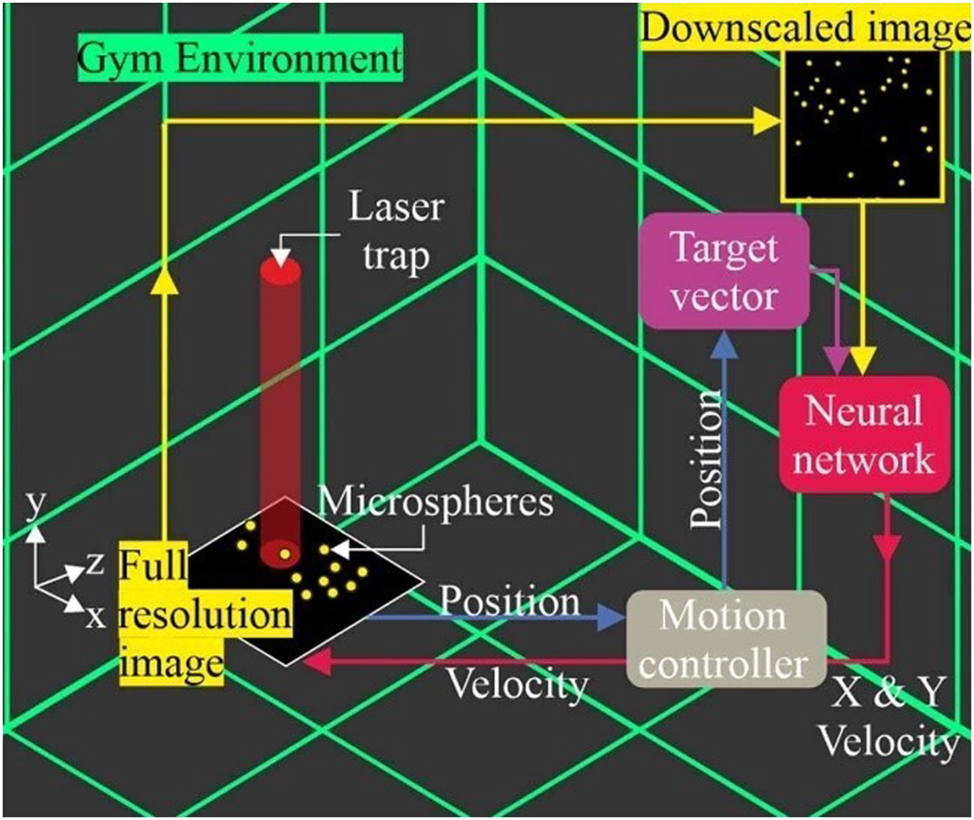

4.3.2 Toward automation

After several years of development, researchers began to focus on automation. In 2012, Chen and Sun, both PhDs from Hong Kong, used holographic optical tweezers as a unique robotic end-effector to arrange swarms of particles into a specified array while effectively preventing particle collisions (Chen and Sun 2012). The following year, Chen et al. employed automatically controlled optical tweezers to flock multiple particles without collisions (Chen et al. 2013). In 2021, Praeger et al. from the United Kingdom integrated virtual and physical environments by training a neural network that could provide limited field-of-view camera images and vectors pointing in the direction of a target (Praeger et al. 2021). As shown in Figure 11, with the neural network continuously controlling the speed of the x and y phases, the optical tweezers could move microspheres to a desired position while avoiding collisions with other free-moving microspheres. Their findings demonstrate the potential of machine learning for controlling light–matter interactions; the findings also demonstrate the potential of machine learning for automating and optimizing various nanoscopic and microscopic photonics and for optimizing engineering and biochemistry tasks.

Schematic of the virtual gym used for testing the trained neural network (Praeger et al. 2021; reproduced with permission from IOP Publishing).

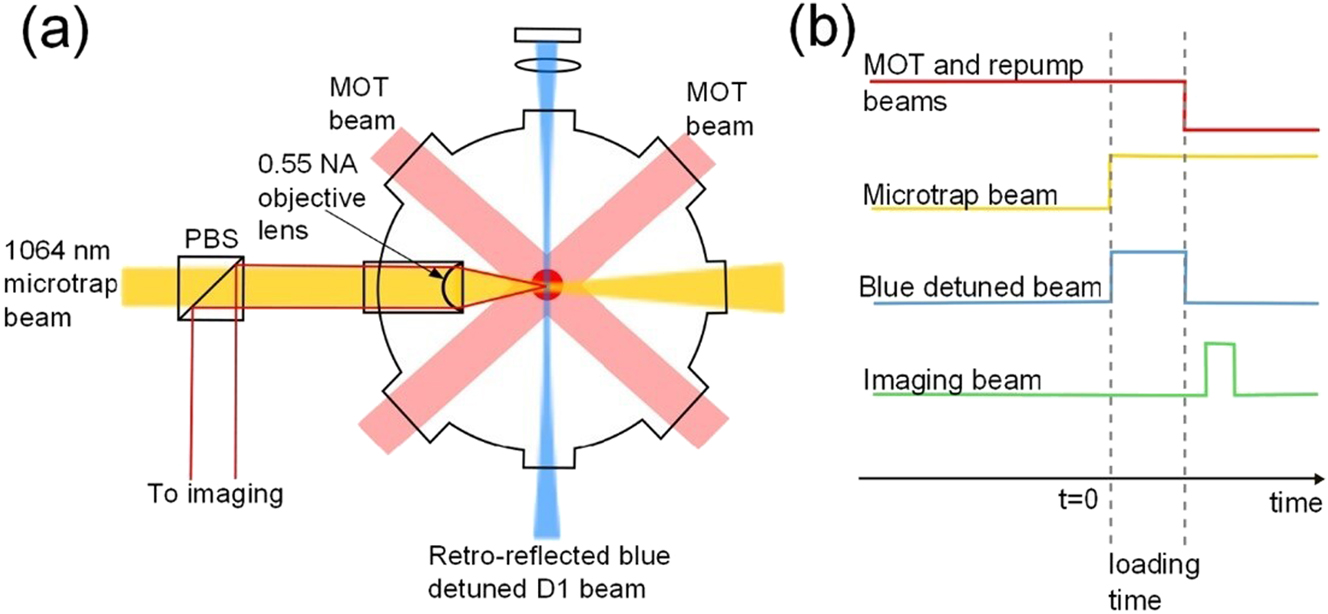

4.3.3 Toward the quantum realm

In 2015, Andersen and Fung began exploring the quantum realm using optical tweezers. They reported a method for efficiently loading individual atoms into tiny traps using controlled inelastic collisions (Fung and Andersen 2015). As shown in Figure 12, this was achieved by precisely controlling a blue detuned laser beam that generated inelastic collisions, enabling the quick removal of an atom when a second atom entered a tiny trap. This increased the efficiency of loading individual atoms into tiny traps. Accordingly, optical tweezers constitute a powerful tool for high-precision atomic manipulation, paving the way for advancements in quantum information processing and few-body physics experiments. In 2017, Thomas et al. from the University of Otago, New Zealand, developed an all-optical atomic collider for studying the collision properties of ultracold atoms at very low energies (Thomas et al. 2017). They manipulated and caused two clouds of ultracold atoms to collide at energies far greater than their thermal energies using optical tweezers. Furthermore, in 2021, Anderegg et al. from the United States produced a pair of colliding molecules by merging two optical tweezers, each containing an ultracold molecule; they performed microwave shielding against inelastic collisions in three-dimensional space (Anderegg et al. 2021). They found that the appropriate combination of microwave frequency and power produced an effective repulsive shielding that suppressed the inelastic loss rate by a factor of six. This was consistent with the results of coupled-channel calculations and the qualitative characterization of shielding theory. The microwave treatment significantly increased the predicted elastic scattering rate. This shielding mechanism can be extended to polar molecules prepared in single quantum states, such as polyatomic molecules. Three years later, Jun Zhuang’s team at CAS discovered that polarization gradients in tight optical tweezers can couple atomic spins to two-body motions, and their research suggests that this spin-motion coupling provides a new tool for the study of reactive collisions in ultracold two-body systems and has potential for more complex atomic and molecular interactions (Zhuang et al. 2024). Recently, Walraven et al. from the United Kingdom observed that collisional loss of molecules in these states could be suppressed by repeatedly loading individual molecules into optical tweezers and transferring them to storage states in rotationally excited states. Dipole blocking prevented the accumulation of multiple molecules (Walraven et al. 2024). This scheme improved the loading efficiency and reduced the time required to organize the optical tweezer array, which is crucial for achieving scalable neutral molecular quantum computers.

Experimental setup and experimental sequence. (a) Experimental setup. The MOT and microtrap are formed inside a vacuum chamber. (b) Experimental sequence. Loading of atoms into the microtrap commences when the 1,064 nm microtrap beam is turned on (Fung and Andersen 2015; reproduced with permission from IOP Publishing).

4.4 Fluid motion

The Navier–Stokes equations are fundamental descriptions of viscous flow and express the basic principles of conservation of mass, momentum, and energy. They are widely used in studying the dynamic behavior of fluids, including in analyses of fluid convection. The momentum equation is as follows (Acheson 2023):

The Continuity equation (for incompressibility) is as follows:

where v is the fluid velocity field, ρ is the fluid density, p is the pressure, μ is the dynamic viscosity, and f represents external forces (like gravity).

The Navier–Stokes equations are among the seven “Millennium Grand Prize Problems” of the Clay Mathematics Institute because of their mathematical complexity and have been the focus of numerous scientists. In 2006, Martin et al. measured the hydrodynamic coupling between a pair of colloidal spheres by using optical tweezers and validated the calculation of the hydrodynamic mobility tensor in the Navier–Stokes equations (Martin et al. 2006). The following year, Schäffer et al. used optical tweezers to measure the drag coefficient of microspheres near a flat surface. They observed that the drag coefficient was height-dependent, validating the exact and closed-form solutions of the Navier–Stokes equations (Schäffet et al. 2007). Four years later, Ueberschär et al. also used optical tweezers to reduce drag when conducting experiments on DNA grafting of individual microspheres in a dilute λ-DNA solution. The experimental results confirmed the values of the measurement uncertainty range predicted using the Navier–Stokes equations (Ueberschär et al. 2011).

In general, researchers previously believed that fluid flow in optical trapping originated from thermal convection induced by the temperature increase due to laser irradiation. However, in 2020, Hosokawa et al. experimentally observed that under the action of optical tweezers, the light scattering force could drive large-scale fluid motion through interactions with laser-induced particle motion (Hosokawa et al. 2020). Specifically, the optical force that leads to convection is the source term of the momentum conservation part of the Navier–Stokes equations. The optical force changes the momentum distribution of the fluid and leads to fluid motion, creating convection. On a macroscopic scale, this convection phenomenon aligns with the predictions of the Navier–Stokes equations.

5 Application of particle dynamics to the study of optical tweezer technology

Particle dynamics has played a major role in the development of optical tweezer technology. Optical tweezers use lasers of specific wavelengths to generate sufficient optical pressure or force to control tiny objects through a carefully designed optical system. This technology enables precise spatial manipulation of target objects on a microscopic scale through the integration of components such as light sources, lens assemblies, reflective devices, and fine micromanipulation platforms. Optical tweezers have been instrumental in solving several notable scientific problems (Chu 2020). They have been successfully applied in various research fields and demonstrated high value in confirming and progressing theories (Praveen Kamath et al. 2023), particularly in cell biology, single-molecule biology, materials science, physics, and colloid science. The noninvasive and highly adaptable nature of optical tweezers facilitates precise movement of microscopic particles or manipulation of molecules, in addition to ensuring an orderly layout for ultrasmall objects or the synthesis of new composite systems.

5.1 Biocytology

In the 1980s, Ashkin, the “father of optical tweezers,” pioneered the use of single-beam gradient-trapped optical tweezers to manipulate viruses and bacteria (Ashkin and Dziedzic 1987). This development led to the birth of a new field, biophotonics (Ilev et al. 2021), which comprises all optical technologies applied in life sciences and medicine (Fang et al. 2023). Spyratou et al. from the Physics Department of the National Technical University of Athens used optical tweezers in combination with Raman spectroscopy to characterize and monitor the physical and chemical properties of cells. For example, they monitored changes in the oxygenation state of human erythrocytes during photoforce stretching (Spyratou 2022).

Meanwhile, in the year 2022, researchers are commencing investigations into the mechanical properties of living cells, with a particular focus on mega phagocytosis, a pathway for the nonselective uptake of extracellular fluids. Mark L. Watson and his team from the University of Queensland conducted an in vivo study using high-resolution rotational geometry to trap and monitor a photonic probe within a macropinosome (Watson et al. 2022). By employing rotational optical tweezers, they measure the shear viscosity of the macropinosome lumen in a living cell at (1.01 ± 0.16) mPas. This research establishes a foundation for dynamic mechanobiological studies of intracellular vesicle processes.

The physical properties of living matter considerably affect biological functions and developmental processes. However, quantitatively measuring the material properties of internal organs in vitro without causing physiological damage remains a technical challenge. To address this, Dzementsei et al. from the Center for Stem Cell Biology of the Novo Nordisk Foundation developed a noninvasive method based on a modified optical tweezer technique complemented by fluorescent markers recently. This method enables the precise determination of the material properties of cells up to 150 µm deep inside living zebrafish embryos (Dzementsei et al. 2022). As shown in Figure 13, their experimental results revealed that these cells display unique viscoelastic properties during the early organogenesis stage and that different body parts have different mechanical properties. Viscoelastic properties describe the flow and deformability of cells and biological tissues in response to forces and are critical for cellular localization, proliferation, and differentiation. Accurate measurements of cellular mechanical properties can help in developing therapeutic approaches for specific disease conditions, such as designing more effective drug delivery systems based on the mechanical properties of cells.

Schematic of the setup for laser tracking of nanoparticles in vivo (Dzementsei et al. 2022; reproduced with permission from Springer Nature).

5.2 Single-molecule biology

In the field of life sciences, optical tweezers enable the manipulation of single cells and promote in-depth studies of biomolecules, including DNA (Bustamante et al. 2021) and RNA (Buck et al. 2022). As pioneering micromanipulation tools, optical tweezers are instrumental in investigating the dynamics, structure, and mechanical properties of proteins, particularly at the single-molecule level. Laminin is a large protein present in the extracellular matrix, which plays a crucial role in its organization and function (Goddi et al. 2021). Mukherjee et al. from the Saha Institute of Nuclear Physics (Mukherjee et al. 2021) used oscillating optical tweezers in active microrheology; a mutant protein of a sample was irradiated with laser light from the oscillating optical tweezers. The momentum of the laser light was transferred to the protein, pushing it (Wei et al. 2008). Its motion was observed to study changes in the viscoelastic parameters of mutant protein meshes. The method could potentially be used for microrheological (Hara et al. 2023) measurements of any intermediate filament protein, paving the way for diagnostic techniques for inherited diseases linked to nuclear structure and functional disorders.

Mechanoenzymes are proteins that play a crucial role in biological processes and facilitate various cellular activities, including substance transport, signaling, and cell division. Externally applied forces or mechanical movements trigger changes in the catalytic activity of these enzymes, thereby enabling chemical reactions (Hollenbach and Ochsenreither 2023). The enzymes function like microscopic engines using chemical energy (e.g., nucleoside triphosphate) to drive precise and directed motion. The rise of single-molecule technologies has enabled a full understanding and characterization of mechanoenzymes, including their force generation, force transfer, quantification, and complex cycling mechanisms. Mukherjee and colleagues from the Indian Institute of Technology conducted single-molecule measurements combined with optical tweezer force spectroscopy to elucidate parameters of enzyme motion properties, such as step distance, kinetic behavior, motion speed, directionality, blocking force, persistence, and the energy cost consumed by each process (Mukherjee et al. 2022).

5.3 Materials science

Optical tweezer technology and MD simulations play unique and complementary roles in materials science. They provide a means of studying the microscopic mechanisms and properties of materials. Optical tweezers manipulate fine particles, and MD simulations model the behavior of these systems at the atomic level. Their combination aids researchers in understanding changes in material behavior under controlled conditions. For example, optical tweezers can manipulate and reveal the properties of material surfaces, and MD simulations can elucidate the molecular mechanisms behind these properties. Understanding the mechanisms of surfactant action at interfaces is crucial for many applications in materials science and chemistry.

The combination of optical tweezer technology and trajectory analysis methods is an effective approach for studying surfactant properties. J. Kim and O. J. F. Martin’s team from the Laboratory of Nanophotonics and Metrology at the École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne in Switzerland used optical tweezers and trajectory analyses to conduct a comparative study of the behavior of cetyltrimethylammonium bromide and cetyltrimethylammonium chloride at a water–glass interface (Kim and Martin 2023). The study involved using optical tweezers to immobilize GNPs. The motion of the particles was statistically analyzed, and the results revealed that the behavior of the counterbalancing bromide ions at the interface significantly affects the surfactant behavior. As illustrated in Figure 14, this study demonstrates the potential of optical tweezers for various applications in surfactant research; the results may have implications for fields such as drug delivery and nanomaterial preparation (Jiang et al. 2023).

MSD for 150 nm gold nanoparticles optically trapped at the glass–aqueous interface in surfactant solutions. (a) Double-logarithmic plot of the MSD at three different CTAB concentrations. (b, c) Long-time limits, MSD (∞), as a function of CTAB (b) and CTAC (c) concentration near the CMC (Kim and Martin 2023; reproduced with permission from MDPI AG).

Combining optical tweezer experiments and MD simulations can enable comprehensive analyses of the thermodynamic and kinetic properties of materials, which is crucial for the design and application of novel materials. Recently, researchers from the Department of Physics of the Federal University of Viçosa, Brazil, demonstrated for the first time the successful use of Gaussian-beam optical tweezers to stably trap and manipulate polyaniline (PANI) microparticles (Oliveira et al. 2023). They characterized the stiffness of the traps for various parameters, including the particle radius size, laser power, and the distance between the particles and the sample chamber’s coverslip. They observed oscillatory dynamic behavior for semiconductors and topological insulator beads and concluded that the trap stiffness is closely related to the investigated parameters. This research demonstrates the feasibility of the optical manipulation of organic semiconductor materials such as polyaniline and provides a valuable reference for future experiments and applications.

Optical tweezers enable the manipulation of nanomaterials at the single-molecule level, and MD simulations provide detailed information on the interaction forces and energy transitions that occur during these manipulations. A variety of nanostructured materials can be formed by modulating the shape, size, and surface properties of colloidal nanocrystals and by controlling their interactions. The self-assembly behavior of these materials is usually studied under equilibrium conditions; nonequilibrium states driven by external forces are still rare. Recently, Felsted and colleagues used optical tweezers to impose an external attractive field and demonstrated the self-assembly behavior of cubic-phase yttrium sodium fluoride nanocrystals (Felsted et al. 2023). Moreover, they investigated the hydrodynamic resistance properties of these crystals and demonstrated that the roughness of the nanocrystal surface played a key role in the assembly and contact between the crystals. These findings contribute to the advancement of nanoscale manipulation techniques, which are crucial for the development of advanced materials and nanotechnology.

5.4 Physics

Optical tweezers have also proven invaluable in the field of physics. They have enabled the verification of physical laws that were previously experimentally untestable. This has enhanced our understanding of existing physical phenomena and rules. For example, optical tweezers have been used to perform experiments regarding the mechanical effects of light (Xie et al. 2016); precise measurement of force (Cheppali et al. 2022); and assessment of Brownian motion, nanotechnology, and quantum mechanics. By advancing the field of physics, optical tweezers are driving societal progress.

At the Institut d’Optique, Université de Paris-Saclayeque, a team led by Damien Bloch employed a precision optical tweezer system at a wavelength of 532 nm to prepare and monitor individual dysprosium atoms. They also employed a composite spectral line at 626 nm for clear imaging (Bloch et al. 2023). The team leveraged the unique optical anisotropy effect of lanthanides to precisely adjust the differential light shift, creating optical tweezers capable of trapping individual atoms in an almost circularly or elliptically polarized light field. This groundbreaking research provides an effective method for manipulating and controlling individual atoms, laying the groundwork for advanced physics experiments and techniques. The precise manipulation of some properties of rare earth elements opens new paths for quantum physics research.

Combining optical tweezers experiments with MD simulations can enable accurately predicting a system’s intermediate states, which is valuable for studying complex dynamic processes. Individual particles in a resonant potential well can display rich quantum states of motion in their high-dimensional state space. A quantum description of motion is crucial when controlling or exploiting the motion of trapped ions and atomic systems and when observing the quantum nature of the vibrational excitations of solid objects. Brown et al. from the University of Colorado’s Department of Physics used direct measurements of position and momentum to achieve quantum tomography of the motion states of individual captured particles (Brown et al. 2023). They used time-of-flight measurements to accurately obtain momentum information for atoms in optical tweezers, successfully accessing all orthogonal distribution states by leveraging the trap’s harmonic evolution properties. Starting from the trapped neutral atoms in nonclassical quantum states of motion, they further confirmed the existence of negative values of the Wigner function and the existence of coherence in the nondefinite domain states.