Abstract

Chemical synthesis has its roots in the empirical approach of alchemy. Nonetheless, the birth of the scientific method, the technical and technological advances (exploiting revolutionary discoveries in physics) and the improved management and sharing of growing databases greatly contributed to the evolution of chemistry from an esoteric ground into a mature scientific discipline during these last 400 years. Furthermore, thanks to the evolution of computational resources, platforms and media in the last 40 years, theoretical chemistry has added to the puzzle the final missing tile in the process of “rationalizing” chemistry. The use of mathematical models of chemical properties, behaviors and reactivities is nowadays ubiquitous in literature. Theoretical chemistry has been successful in the difficult task of complementing and explaining synthetic results and providing rigorous insights when these are otherwise unattainable by experiment. The first part of this review walks the reader through a concise historical overview on the evolution of the “model” in chemistry. Salient milestones have been highlighted and briefly discussed. The second part focuses more on the general description of recent state-of-the-art computational techniques currently used worldwide by chemists to produce synergistic models between theory and experiment. Each section is complemented by key-examples taken from the literature that illustrate the application of the technique discussed therein.

1 Introduction

Since the days of Galileo Galilei, science has been approached using the scientific method. The routine of “curiosity sparking observation, formulation and testing of new hypotheses and birth of new theories” represents the first rudimentary iterative block-diagram algorithm to approach “scientifically” any natural phenomenon. Both the predictive and explanatory power of science, and so its evolution, reside in the use of models. Models are rescaled and simplified visions of reality that scientists create to afford an explanation and prediction of phenomena within certain levels of confidence. Leonhard Euler himself commented on the power of the model with his famous maxim: “Although to penetrate into the intimate mysteries of nature and thence to learn the true causes of phenomena is not allowed to us, nevertheless it can happen that a certain fictive hypothesis may suffice for explaining many phenomena”. Euler’s “fictive hypothesis” is an approximated, yet powerful tool to account for and, ultimately, influence or even control phenomena to the benefit of humanity. Nowadays, mathematical models are routinely employed to predict events in physics, engineering and natural sciences [1, 2].

What could be inferred about chemistry, then? Any dedicated scholar sooner or later stumbled upon the uncomfortable question: Can complex chemical reactions be predicted by rational models? Chemical sciences are intrinsically more bound to their empirical nature than other scientific disciplines, given the fact that the ultimate goal of chemistry is to make new molecules for market, technology, society or simply for scientific interest [3]. The construction of a priori models of complete reactions is currently regarded over-ambitious, given the extreme difficulty to characterize accurately Avogadro’s numbers of solvated molecules, predict their reactive events in such environment and simulate the course of n-parallel and competitive channels during a desired interval of time. While such search for rationality poses unparalleled challenges, it would also represent, if successful, the pinnacle of chemical manipulation and establish an evolved concept of understanding and doing chemistry. This evolution will lead to a new level of rational design of target compounds and transform chemistry into a discipline scientists can fully control, rather than merely observe and improve through trial-and-error strategy. The structure of the chapter has been organized in a way that the reader will receive a general, yet detailed, wide-angle history of chemistry, followed by a more specific treatment of theoretical disciplines. Each section will be integrated with interesting examples singled out from a massive multidisciplinary pool of excellent scientific works. The selection criteria were not only based on relevance, impact factor and citations of the works but also on the diversity of the field and author’s interests and familiarity with the works. The common trait d’union of these works is represented, however, by the synergistic interdisciplinary approach between theory, spectroscopy and experiment. The use of theoretical assets in solving chemical problems, whether a priori or a posteriori, serves as a proof of concept of rational chemistry. The author wishes to convey the idea that chemistry is a multifaceted scientific ground where experimental and theoretical approaches are far from being rivals; on the contrary, they imparted together an evolutionary rational momentum to the discipline.

This momentum allowed chemistry to blossom into a modern science during the last 400 years, from nothing more than a collection of esoteric notions. We could say that chemistry is a relatively young discipline since a scientific, systematic and non-serendipitous approach to this field has been introduced not earlier than the sixteenth century. Technological advances in synthetic methodologies, spectroscopy and data sharing allowed chemistry to reach unprecedented goals and successes. The development of computers carved an important role for theory into the full landscape of chemical disciplines. This chapter reviews the synergistic integration between practical and theoretical fields for the betterment of rational principle underlying chemistry. In line with the guiding philosophy of this project, there is not a preferred target audience for this chapter. The author simply hopes that it will be descriptive enough to interest theoreticians of any level and useful enough to show spectroscopists and experimentalists “what they can actually do” with theoretical methods, should they decide to use them as a viable first term of comparison in their researches.

2 The past: Birth of a discipline

In ancient Egypt the idea of a rational principle behind natural transformations was associated to the existence of Thoth, the god of wisdom, magic and writing. Back then, and for the rest of the ancient history, the use of simple chemical transformations was mostly relegated to common life activities, like metallurgy [4]. At the turn of the first millennium, the first sparkle of “scientific” approach made its entrance in history, with the work of the Persian mathematician and astronomer Ibn al-Haytham on light and optic [5]. Some decades later on, a new discipline grew strong in continental Europe, drenched in all the esoteric mysticism and symbolism that Medieval Age could spawn: alchemy [4]. The word from Greek-influenced Arabic language, al-kīmiyā, means the art of transmuting metals. Alchemic cult of the four natural elements (water, air, fire and earth) and the two philosophical elements (sulfur and mercury) rooted back to Hellenistic [4] and Arabic beliefs, like those of the Persian alchemist Jābir ibn Hayyān [6]. The alchemic period (Figure 1) lasted more or less until the Seventeen Century and was characterized by bizarre individuals like Paracelsus or N. Flamel, whose mysterious vaunted powers failed to achieve the envisioned goals, given the fact that neither the philosopher’s stone nor the elixir of eternal life has ever become solid realities. Alchemy incurred often in the wrath of the religious authorities, since it was regarded as a practice inspired by the Devil itself; ironically enough, it is exactly the art of combining substances that provided the Church with the most beautiful heritage for posterity, like the exceptional stained glasses we can still admire in Chartres cathedral.

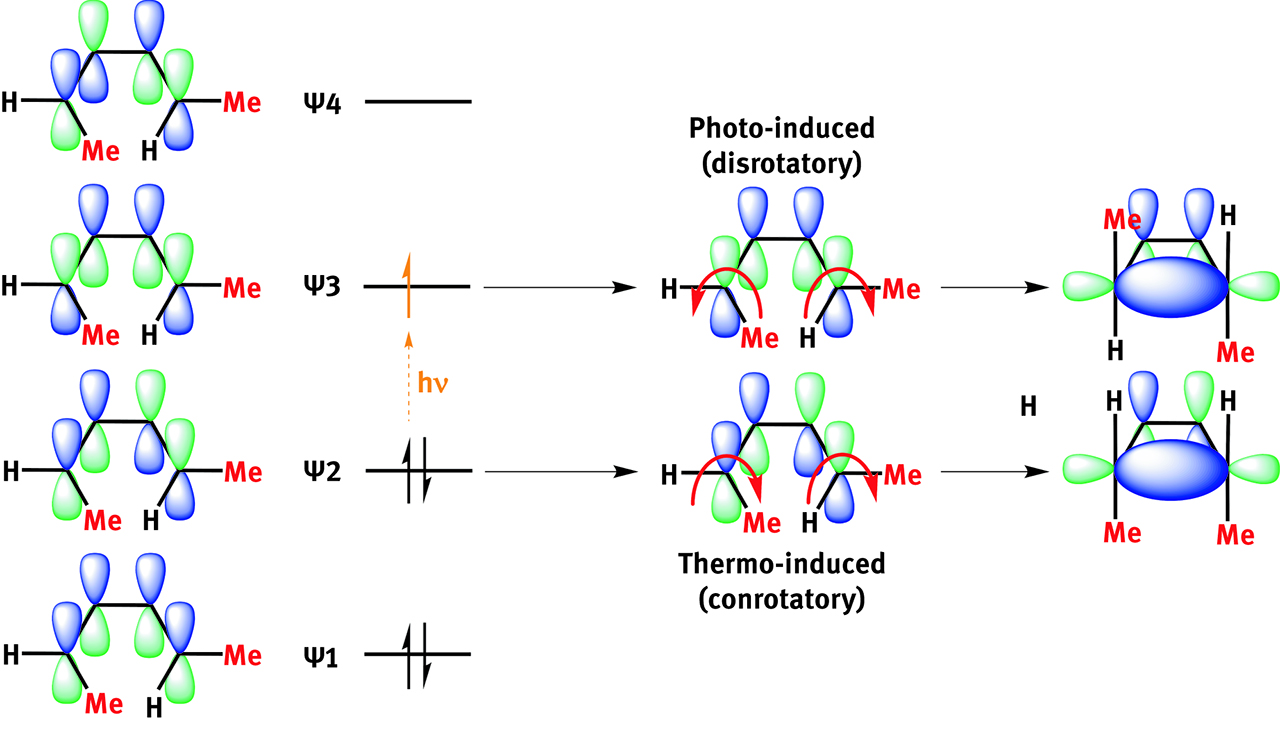

Electrocyclic reactions can be predicted through simple Huckel diagrams. (E,Z)-2,4-hexadiene can cyclize giving either cis- or trans-dimethylcyclobutene (on the right) depending on orbital control (and vice-versa for the ring-opening reaction).

Modern chemistry, as we intend it, was born in the late sixteenth century. The recognized fathers of modern chemistry are R. Boyle and A.L. Lavoisier [4]. They introduced a rational and scientific approach to chemistry that led them to an unprecedented understanding in the chemistry of gases, air and combustions and to the definitive destruction of the J.J. Becher’s phlogiston theory [4]. Lavoisier has been also credited for the first attempt in dissemination of chemistry by writing the first chemical book, Traité Elémentaire de Chimie (1789) [4]. As the years went by, J.L. Proust, J. Dalton and A. Avogadro postulated three famous laws that still carry their names and are taught to our freshmen within the first week of a general chemistry course: the law of constant composition, the law of partial pressures and Avogadro’s principle, respectively [4]. The interaction of electrical current with chemicals and solutions was pioneered by H. Davy, J.J. Berzelius and M. Faraday [4], who started the field of modern electrochemistry. The first statistical ordering of the properties of the elements by their atomic weight and valence was attempted independently by J.L. Meyer and D.I. Mendeleev through the construction of the first periodic tables. The power of such embryonic models was suddenly clear. A few elements and related properties could be predicted by Mendeleev in 1869–1871 (Table 1): for instance, Mendeleev’s eka-boron, eka-aluminium and eka-silicon were discovered in 1879, 1875 and 1886, respectively, and renamed scandium (1879), gallium (1875) and germanium (1886) [7]. It is finally with F. Wöhler and H. Kolbe that the word “chemical synthesis” starts to assume the meaning we ascribe to it today. Wöhler and Kolbe contributed to destroy vitalism demonstrating that organic molecules can be made from “anorganisch” compounds [8, 9]. The nineteenth century was a golden century for chemistry. F.A. Kekule’s studies on the structure of hydrocarbons and benzene opened the way for a systematic pursuit of organic chemistry. H.L. Le Chatelier, J.H. Van’T Hoff, W. Ostwald, J.W. Gibbs, S.A. Arrhenius and W. Nernst set the bases for the modern interpretation of thermodynamics, kinetics and electrochemical processes. L. Boltzmann recognized the strong connection between probability and thermodynamics and founded statistical thermodynamics.

Mendeleev’s early periodic table shows the power of prediction of a simple model.

| Chemical properties | Mendeleev’s prediction in 1871: Eka-silicon | Element properties: Germanium |

|---|---|---|

| Atomic weight | 72 | 72.61(2) |

| Density/g∙cm−3 | 5.5 | 5.323 |

| Molar volume/cm3∙mol−1 | 13.1 | 13.64 |

| MP/˚C | high | 945 |

| Specific heat/J∙g−1∙K−1 | 0.305 | 0.309 |

| Valence | 4 | 4 |

| Color | Dark grey | Greyish-white |

H.E.L. Fischer initiated the interest in biological chemistry with his studies on sugars, their reactivity and structural properties (i. e. stereochemistry); he also proposed the “lock and key” model to explain enzyme-substrate interactions. J.C. Maxwell formulated the classical theory of electromagnetism that holds together electricity, magnetism and light [5] and inspired the successive two greatest theories, relativity and quantum mechanics. At the end of nineteenth century and beginning of twentieth century new discoveries shed light on the structure of the atom. The fundamental particles that compose atoms were discovered by J.J. Thomson (electron in 1897), E. Rutherford (nucleus in 1911 and proton in 1919) [4], J. Chadwick (neutron, in 1932). In 1913, H.G.J. Moseley proved by x-ray spectra that Z, the number of protons in an element, defines its position in the periodic table [4]. Another meaningful example of simple models laid out to rationalize more complex phenomena is provided by Blomstrand-Jørgensen-Werner diatribe which arose in the late nineteenth century hoping to explain the peculiarity of the bond in metal-containing compounds. Some of these compounds, like Prussian blue, KFe[Fe(CN)6], and aureolin, K3[Co(NO2)6]0.6H2O, have been known since ancient times and used as pigments for their intense colors. The developing analytic techniques provided molecular formulas for these compounds; hence the need for a clear explanation about the nature of the bonding in these compounds, since they formally exceeded their valence or the concept of allowed valence developed until that point. Two models responded the call: Werner’s and Blomstrand-Jørgensen’s. A. Werner can be considered the father of modern coordination chemistry. His model consisted of metal centers able to expand their valence to bind extra “ligands”. In the case of the compounds that cobalt(III) trichloride forms with ammonia he hypothesized that the cobalt was in an octahedral environment surrounded by ammonia molecules (Table 2). According to different stoichiometries, the chloride ions could have been tightly bound (those primarily connected to the cobalt) or loosely bound (highlighted in red in Table 2). C.W. Blomstrand and later S.M. Jørgensen tried to explain the bonding mode of such cobalt compounds using a conventional model, the chain theory, more akin to the developing tetravalent carbon chemistry. They supposed that the loosely bound chlorides were those connected to NH3 moieties. Interestingly both models afforded the same answer in the rationalization of the ionic nature of some chloride ligands present in these complexes, as seen in Table 2. No evidence could put the final word to Werner-Jørgensen’s long-lasting rivalry until Blomstrand-Jørgensen’s model was finally disproved in 1907 when Werner synthesized two isomeric forms of [Co(NH3)4Cl2]+, one called (later on) cis, showing a violet color and one called trans, showing an intense green color. The chain theory was unable to explain this simple differentiation within the same molecular formula.

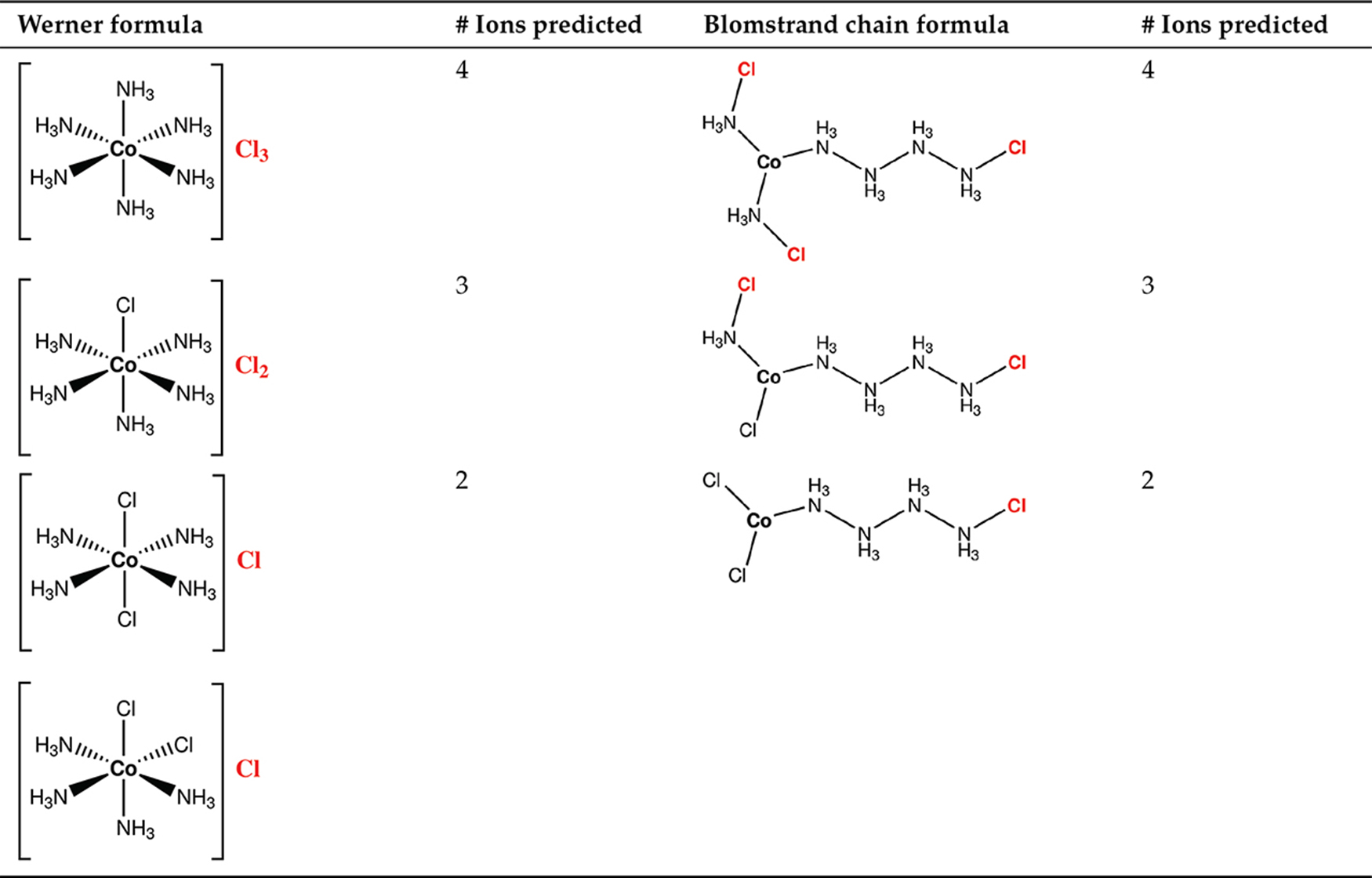

The first hypotheses on the structure of cobalt coordination compounds: Werner versus Blomstrand.

The twentieth century will be remembered as the century that saw the birth of quantum mechanics and relativity, two theories that challenged classical mechanics. N. Bohr [10], A. Sommerfeld, M. Planck and L. De Broglie fathered this early quantum theory. It rose to explain theoretically the position of line spectra in the Balmer series of hydrogen [4]. The first fundamental notion embedded in this new theory was that the energy state of any system is discreetly expressed in integer multiples of a constant, h (Planck’s constant). This managed to satisfactorily explain hitherto unexplained phenomena like black body radiation, the photoelectric effect and the Compton effect [11]. The second assumption was that particles have both matter and wave-like properties, having associated wave-lengths inversely proportional to their masses (λ ∝ m−1, de Broglie) [4]. The new quantum theory acquired the foundation of the early theory and expanded it with the new notion of wave-mechanics. E. Schrodinger formulated the famous eigenvalue equation that still bears his name and is at the foundation of modern quantum theory. Among several contributions, M. Born proposed the interpretation of the square of the wavefunction as the probability amplitude to find an electron in the r space and P. Erhenfest proposed his theorem on the behavior of expectations values for momentum and position operators. These theoretical insights brought about the famous three atomic quantum numbers (s, l, ml). A fourth quantum number, ms, was proposed by W. Pauli in 1924, after his famous formulation on the exclusion principle of two electron in the same quantum state [4]. The existence of the electronic spin was discovered by the Stern-Gerlach experiment in 1921 [4]. In 1927 W. Heisenberg formulated his uncertainty principle (λp∙λx ≥ ħ/2) on the impossibility to determine with absolute precision both momentum and position of a particle. These principles proposed by quantum mechanics struck a hard blow at the heart of the classical theories, whose principal aspect was the determinism of all the properties in a system. This was difficult to accept for many physicists. A. Einstein, for instance, regarded quantum mechanics as an “incomplete” theory in his famous Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen principle [12]. Supporting proofs of the consistency of the new theory, however, came with the discovery of particle tunneling through potential energy barriers and particle diffraction, typical aspects of wave-like behavior. The first phenomenon is known as radioactivity and deals with unstable nuclei expelling α-particles and internal β-electrons (both discovered by E. Rutherford in 1899, albeit the latter were erroneously believed to be rays). Radioactivity was discovered by the pioneering studies of H. Becquerel, W. Crookes, W. Rontgen, P. and M. Curie. The second phenomenon is electron diffraction, proved independently by G.P. Thomson and C.J. Davisson with L.H. Germer, which is the base of modern transmission electron microscopy (TEM) [13] and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) [14]. In the same years, P. Dirac, the founder of quantum electrodynamics, formulated his relativistic version of the Schrödinger equation [11, 15]. One of the final supporting proof on the non-locality nature of quantum entanglement, in violation of Bell inequality and EPR principle, came from experiments performed by R. Hanson’s group in 2015 [16].

All these discoveries sealed a definitive connection between physics and chemistry: the common ground allowed the development of a new theoretical body of investigation that will be treated at length in the next section. The Physics-chemistry partnership also lead to the development of new spectroscopic techniques that, in turn, provided structural insights as well as new chemical synthetic strategies, analysis and planning; nowadays, chemists can use powerful spectroscopic tools to characterize their products or test ongoing reactions in situ in a fast and efficient manner. Together with the improvement of laboratory technology and equipment, detection techniques like ionization mass spectrometry [17] and purification/separation techniques like high-performance liquid chromatography [18] or gas-chromatography [19] contributed to non-trivial betterments in the field of synthesis. In the Sixties, the process of rationalization of chemistry took a further step ahead with E. Corey’s retrosynthesis, a new way to look at and plan organic total syntheses [20]. Another fundamental improvement in the scientific community, often disregarded, came from the creation of the scientific literature, a platform for data-mining, dissemination and exchange of scientific peer-reviewed results. H. Oldenburg is the father of peer-reviewing mechanism and founding editor of the oldest and still active scientific journal The Philosophical Transactions of The Royal Society (1665) [21]. Thanks to the improvement of social media and the invention of cyberspace (i. e. Internet), scientific literature is a globally-accessible tool, essential for any starting and developing research project. Despite all this development, modern synthetic research still relies heavily upon serendipitous discoveries and empirical “trial-and-error” methodology to obtain target compounds. These combined approaches have brought chemistry to sensational discoveries throughout the years, but also contributed to generate chemical waste like volatile organic compounds (VOCs) [22, 23]. In the Nineties, Green Chemistry concept was proposed mainly in reply to the US Pollution Prevention Act and was codified into twelve rules by P. Anastas and J. Warnet [24]. Green chemistry provides a list of strategies to mitigate the environmental impact of large preparations and manufactures. In two centuries, von Liebig’s bulky glassware has been more and more replaced by fine glassworks, microreactors, pumps and robotics; new ways of doing chemistry have been developed, like flow chemistry [25] and combinatorial chemistry [26].

The ninth statement of Green Chemistry suggests that catalytic, rather than stoichiometric, protocols should be implemented [24], igniting the spark of an unprecedented “catalyst” rush; ever since, more and more efficient catalysts have been designed experimentally and trial-and-errored to assess their activity or lack of it. Nature exerts the same trial-and-error strategy in designing biologically active molecules to achieve efficiency, improved selectivity and durability. This endless process is called evolution and, unlike our methodologies so far, it is always economic and clean. The fourth statement suggests that chemicals should be designed to improve their desired function, while minimizing toxicity [24]. This is precisely where theoretical disciplines supported by computational methods make their grand entrance.

3 The present: Rise of a rational discipline

Early models based on the newly discovered atomic theories have been effectively used to solve experimental issues during the last century. Few very famous examples include:

Lewis Structures proposed by G.N. Lewis [27] to rationalize the nature of the chemical bond.

Valence Shell Electron Pair Repulsion (VSEPR) theory by R.J. Gillespie and R. Nyholm [28] to rationalize the nature of chemical bond and the shape of molecules.

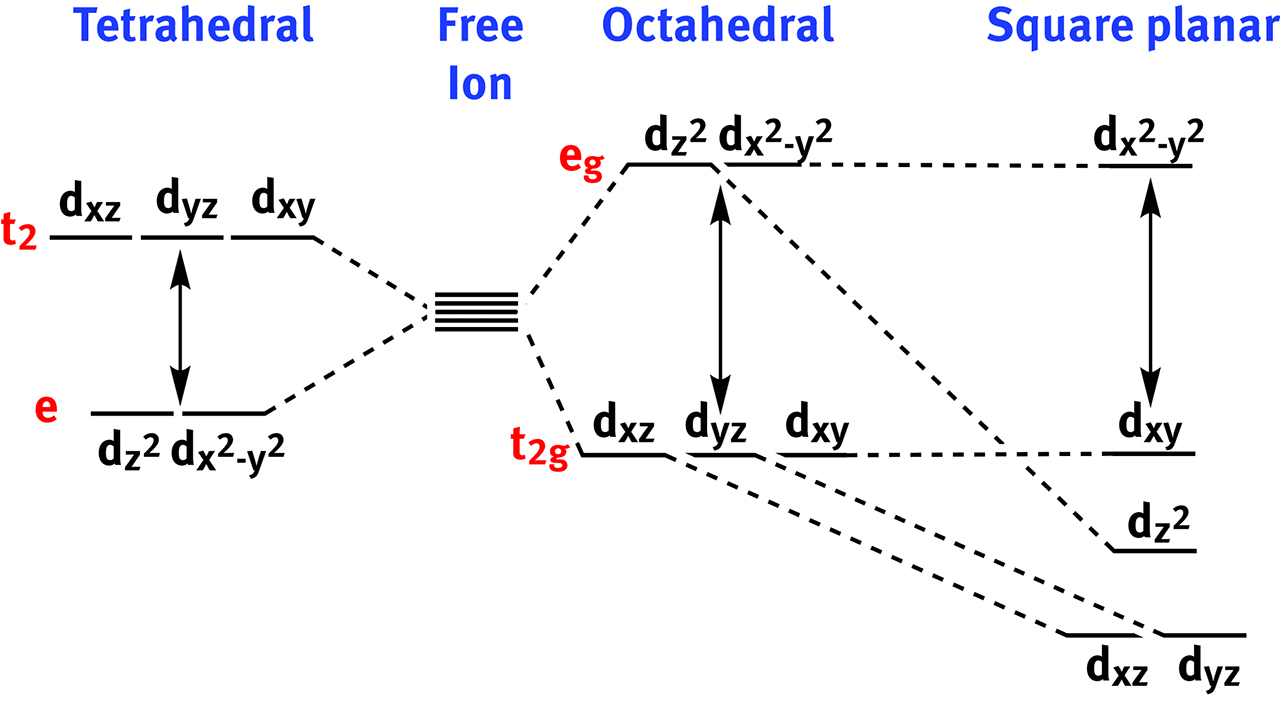

Crystal Field Theory (CFT) proposed by H. Bethe and J.H. Van Vleck [32] to rationalize the bond in complexes between metal ions and simple ligands. The interactions were treated as simple fields of electrostatic repulsions between the ligands and the d orbitals of the metal pointing in the same direction (Figure 2). Crystal field theory and Racah parameters [33] gave birth to Tanabe-Sugano diagrams [34, 35, 36], powerful tools to explain and predict spectroscopic and magnetic properties of coordination complexes.

Molecular Orbital Theory (MO), also called Hund-Mulliken theory, originally proposed by F. Hund, R. Mulliken, J.C. Slater and J. Lennard-Jones [37] in the late Twenties to rationalize the nature of the chemical bond (localized and delocalized), in light of the new quantomechanical findings. It successfully predicted in 1929 the paramagnetism of molecular O2 in its ground state [37]. Mulliken predicted the existence of two excited states, above the ground state, 3Σg−[38]. 1Δg is commonly referred as singlet oxygen and it is 94.7 kJ/mol higher in energy than 3Σg−, while 1Σg+ is 157.8 kJ/mol higher than 3Σg-[39]. Molecular orbitals are expanded as linear combination of atomic orbitals (LCAO) to generate bonding, non-bonding and anti-bonding orbitals (Figure 3).

The destabilization of the orbitals of the metal, hence the crystal field splitting energy, depends upon the geometric arrangements of the ligands around it. The main classes of crystal fields are represented in this figure.

Molecular orbital sketch of O2. The simplest prediction extrapolated from it is that the triplet state is the most stable since it fully complies with Hund maximum multiplicity rule.

Though some of these models are still invoked by experimentalists to justify phenomena, chemistry has evolved and so did the challenges, goals and problems connected to it. Luckily, advanced quantum mechanics coupled to increased computational power (Figure 2), made possible by the development of hardware (e. g., J. Bardeen’s transistors in 1940–1950) and software (e. g., Gaussian 70 in the Seventies), triggered the construction of more powerful and descriptive in silico models in this last two decades. The next section covers the state-of-the-art in modern theoretical computation.

3.1 Electronic structure

Hartree–Fock (HF) theory uses a single Slater determinant in its wavefunction definition to comply with the anti-symmetric nature of electron spin. Initial trial molecular spinorbitals are expressed as linear combinations of atomic orbitals and optimized through the Fock operator (Roothaan-Hall equations) and an iterative process known as self-consistent field [43]. The limit of HF resides in its inexistent treatment of electron correlation. Atomic orbitals can be constructed using Slater functions (STO),

The early alternative to HF-based methods for large systems was represented by semi-empirical methods: they feature minimal quantum-mechanical treatment of the atomic valences through small basis sets, combined with zero differential overlap (ZDO) approximation [15] and parameterization with terms derived from experimental reference data [15]. Today neglect of diatomic differential overlap (NDDO) methods like PM7 [46] are excellent and inexpensive way to obtain semi-quantitative information on a system, particularly useful when conformational analysis is required. The second alternative is represented by density functional theory (DFT) methods. DFT theory has its roots in the work of W. Kohn, P. Hohenberg and L.J. Sham [47, 48]. Kohn–Hohenberg theorems bind the ground state electron-density of a molecular system,

Average of mean unsigned errors (in kcal/mol) for all DFT functionals tested in Truhlar’s database CE345 and grouped according to their year of publication. This database includes 15 subgroups of different chemical properties.

Summary of DFT methods, definitions, dependencies and place on the Jacob’s ladder. PT2 stands for perturbational theory truncated at the 2nd term.

| Functionals combination | Type (# rung in Jacob’s ladder) | Dependencies |

|---|---|---|

| SVWN, PZ81, CP, PW92 | LDA (#1) | ρ(r) |

| BLYP, BP86, PBE, B97D | GGA (#2) | ρ(r), |∇ρ(r)| |

| t-HCTH, TPSS, VS98, VSXC, M06L | Meta-GGA (#3) | ρ(r), |∇ρ(r)|,∇2ρ(r) (τ) |

| B3LYP, B3PW91, B3P86, PBE0, mPW1PW91, BMK | Hybrid GGA (#4) | ρ(r), |∇ρ(r)|, %HF exchange |

| B1B95, BB1K, MPW1B95, MPW1KCIS, PBE1KCIS, TPSS1KCIS, TPSSh, M06, M06-2X, M11, MN12-SX | Hybrid Meta-GGA (#4) | ρ(r), |∇ρ(r)|, ∇2ρ(r) (τ), %HF exchange |

| MC3BB, MC3MPW, B2PLYP, B2KPLYP, B2TPLYP, mPW2PLYP, XYG3 | Double hybrid (#5?) | ρ(r), |∇ρ(r)|, %HF exchange, PT2 corrections to the correlation functional |

Heavy metals of the third row, especially Au [70], display electrons moving at nearly-relativistic speeds due to a high Z number. The moving mass of these fermions undergoes relativistic increment given by the equation

Effective core potential, ECP, like LAN [72], SDD [73, 74] and CEP [75]. Basis functions are replaced by potential functions at the core and the extent of the replacement defines large-core (frozen core and valence), medium-core or small-core (frozen core + valence treated by basis set) pseudopotentials. Accurate results are more likely to be obtained using small-core ECPs [76]. The basis sets complementing medium and small-core ECPs are designed to fit the pseudopotential used, generally through appropriate primitive contractions [77].

Relativistic Hamiltonians coupled with full-electron basis sets. Relativity can be brought into the Schrodinger equation through the Dirac equation. Douglas–Kroll–Hess (DKH) transformation is commonly used for its accuracy, efficiency and effectiveness [78]. Appropriate basis sets are built by contracting primitives [77].

The goal of electronic structure calculations is to generate potential energy hypersurfaces, alias “mapped” polydimensional surfaces that correlate the potential energy in function of the nuclear coordinates of the atoms. Wells or minima on these surfaces represent stable structures. Calculated metric parameters for these minima provide useful information to synthetic chemists because they can be compared with metric parameters derived from phase scattering of x-ray or neutron single-crystal diffraction experiments [79]. Vice versa, this is also an approach used by theoreticians to validate bona fide the goodness of their calculations. This approach is, however, a risky procedure and must be done carefully for two reasons: the maxima in scattering amplitudes may not coincide with nuclear positions in light atoms and structures in solid state are affected by crystal packing and dielectric fields, not present in the isolated calculated counterparts [80].

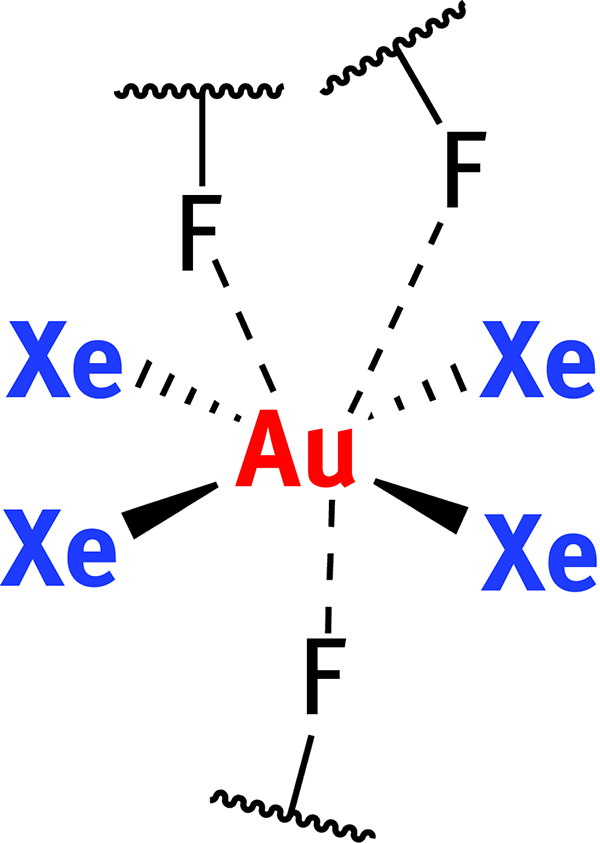

Seidel-Seppelt unique compound. Au•••F contacts with the counterions are shown.

Electronic structures predicted the existence of “impossible” compounds like AuXe+ and XeAuXe+ in 1995 [81]. The calculations were carried out by P. Pyykkö et al. using methods like MP2, MP4 and CCSD(T): the bond distance Au-Xe calculated at MP2 level was found to be 2.691 Å for AuXe+ and 2.66 Å for XeAuXe+. The stability of these compounds was attributed to the high electronegativity of gold, due to relativistic effects; the bond dissociation energy for AuXe+ decreases from 0.910 to 0.376 eV when relativistic effects are omitted at CCSD(T) level [81]. The existence of AuXe and XeAuXe+ was confirmed experimentally in 1998 by Schröder, Pyykkö et al. [82]. Finally, Seidel and Seppelt isolated the first stable gold compound with xenon, [AuXe4][Sb2F11]2 (Figure 5), in 2000[83]. The compound confirmed the stability postulated for this class of compounds being stable up to 40˚C. Metric parameters for Au-Xe bond distance, 2.728(1)-2.750(1) Å, extracted from X-ray diffraction agrees well with distances calculated at MP2 level, 2.787 Å [83]. Electronic structures and enthalpy of formation predicted also the existence of another “impossible” compound in the solid state, Na2He. The predicting algorithm in the USPEX code [84] suggested the existence of a cubic-phase structure of Na2He, stable at pressures above 160 GPa. The structure was effectively isolated as a cubic-phase, stable from 113GPa up to 1000 GPa, and characterized in matrix by A.R. Oganov et al. [85]. The electronic structure of the solid was studied by density of states, ELF and Bader’s analysis [85].

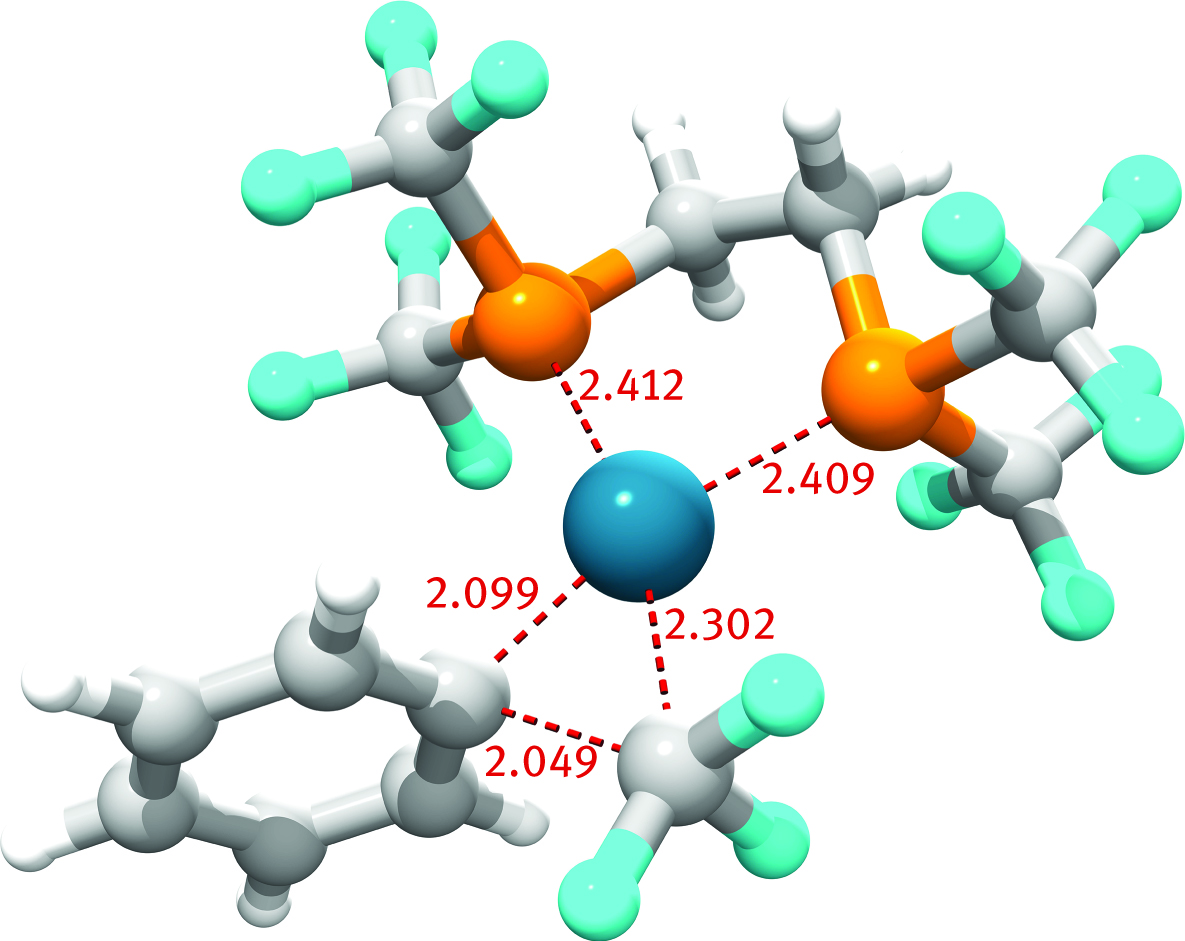

Electronic structures can be directly linked to magnetic spectroscopies based on the Zeeman effect [86]. In nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR)[87] and electronic paramagnetic resonance (EPR)[88], low frequencies waves (radiofrequencies for NMR and microwaves for EPR) are pulsed to make net nuclear (NMR) or electronic (EPR) spin magnetization process about an axis in a magnetic splitting field B0[89]. This precession is sensitive upon the chemical environment of each nuclear or electronic spin. NMR spectra (shift and spin-spin coupling) can be efficiently simulated in gas or in solvent phase by calculating 1D-NMR shielding tensor and susceptibilities using Gauge-Independent Atomic Orbital (GIAO) [90, 91, 92] or Continuous Set Of Gauge Transformations (CSGT)[92, 93, 94] methods. Accurate results versus experiment can be achieved by using high level of theory, usually DFT or MP2[92, 95, 96], in conjunction with large, polarized and diffused basis sets. Similarly, hyperfine coupling constants for EPR spectra can be calculated using EPR-II and EPR-III basis sets [97]. GIAO calculations using a pure GGA functional, BP86 (implemented in G03[98]), in conjunction with SBK basis [99] for metals and 6–311++G(d,p) for carbons and hydrogens have been employed by H.V.R. Dias and T.R. Cundari et al. to provide a comparison to experimental 1H and 13C{1H} NMR spectra in exceedingly rare adducts of ethane with coinage metals [100, 101], Table 4. A further model [102] was generated using a hybrid GGA, B3PW91, in conjunction with SDD pseudopotential and K.A. Peterson’s correlation consistent basis sets [77]. Theoretical values shown in Table 4 for both models along the homoleptic series [M(η2-C2H4)3][SbF6] (for M = Cu, Ag, Au) show amazing structural and spectroscopic reproduction of the studied species. Similar computational studies were carried out to explain the NMR and bonding patterns of a peculiar complexation between trans,trans,trans-1,5,9-cyclododecatriene, CuSbF6 and carbon monoxide [102, 103].

Theoretical computation can be used to validate experimental results, as in the case of reactive coinage wheels. Reference temperature for NMR data is 298 K.

| Compound | Data | 1H NMR, δ | 13C{1H} NMR, δ | M-C, C=C bond distances (Å) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [Cu(η2-C2H4)3][SbF6] | Exp. | 5.44 (CD2Cl2) | 109.6 (CD2Cl2) | 2.193(6),1.359(8) average |

| Comp. | 5.2 (gas) | 100.0 (gas) | 2.172, 1.374 (D3h) | |

| [Ag(η2-C2H4)3][SbF6] | Exp. | 5.83 (CD2Cl2) | 116.9 (CD2Cl2) | 2.410(9), 1.323(14) average |

| Comp. | 5.6 (gas) | 110.9 (gas) | 2.408, 1.367 (D3h) | |

| [Au(η2-C2H4)3][SbF6] | Exp. | 4.94 (CD2Cl2) | 92.7 (CD2Cl2) | 2.268(5), 1.364(7) average |

| Comp. | 5.0 (gas) | 92.6 (gas) | 2.308, 1.388 (D3h) |

Electronic structures can clarify the dynamic behavior of molecules whose potential energy surfaces change upon the absorption of photons of visible or ultra-violet light. Organic chromophores fall under this category, since light can cause transitions from bonding to antibonding orbitals [104]. Heavy metal complexes show also spin-allowed, Laporte-allowed transitions, ligand-to-metal (LMCT) and metal-to-ligand (MLCT) charge transfers [32]. The transition momentum from ψ1 to ψ2 eigenstate, M2,1 = <ψ2|μ|ψ1>, can be calculated for vertical excitations (complying with Born-Oppenheimer approximation) to provide transition energies, multiplicities, symmetry and oscillator strengths, thus simulate UV-Vis and circular dichroism spectra. UV-Vis spectroscopy [89] is used by experimental chemists to identify and quantify an active substance through absorbance and Beer-Lambert law; the description of this approach and its limits are well known [105]. Time dependent density functional theory (TDDFT) coupled with medium-to-large basis sets generally provides reasonably accurate results (i. e., within 0.4 eV from experimental transitions) at a very affordable cost, but it has limitations like the absence of double excitations [106]. Most used DFT functionals are B3LYP and PBE0, although the popularity of functional including long-range corrections to the Coulomb term (e. g., cam-B3LYP, LC-ωPBE and ωB97XD) is rising. More refined and resource-consuming alternatives to TDDFT feature CASSCF and CASPT2, techniques based on the complete active orbital space (including PT2 corrections in the latter) [107]. Modeling excited states encompasses the study of the reorganization energy of the molecule and the solvation layer after the absorption of light; bathochromic shifts can be obtained this way to simulate experimental fluorescence spectra. Study of intersystem crossing phenomena (i. e., conical intersections between different spin potential surfaces) can be valuable to study phosphorescence [108]. Intersystem crossings are more common for heavy metal complexes with strong spin-orbit coupling. Diffuse functions and long-range corrected functionals might be mandatory when studying excited states of higher energy (i. e. other than the first one). Photo-induced single transfer redox reactions via outer sphere mechanism involve bimolecular events between oxidants (electron acceptor) and reducing species (electron donor); Marcus theory was designed to calculate the barrier of activation in terms of free energy difference for such processes, ΔG‡ = (ΔG+λ)2/4λ (λ is the reorganization energy of all the atoms involved in the reaction)[109, 110]. The thermodynamic function that expresses quantitatively the propensity for the transfer of electron(s) is the standard reduction potential; it can be measured experimentally by cyclic voltammetry and calculated using a variety of methods involving implicit, explicit or mixed solvation schemes [111]. Mean unsigned errors of computed values versus experimental ones are reported in the range of 64 mV (~ 6 kJ·mol−1) and as low as 50 mV for selected classes of compounds [111]. Electrochemical methodologies are fundamental in processes like artificial photosynthesis and water splitting [112, 113].

3.2 Solvation schemes

The solvent influences kinetic and thermodynamic aspects of a chemical reaction, thus the accurate evaluation of solvation effects should be brought into the calculations. Several different solvation schemes are available: implicit, explicit or mixed implicit-explicit. Implicit methods allow for quanto-mechanical treatment of the solute and for bulk treatment of solvents as continuous envelopes around solutes, characterized by macroscopic properties like dielectric constants and microscopic properties like solvent radii. Usually computationally very affordable for spectator solvents and reasonably accurate, implicit solvation models are listed below:

Explicit methods allow for quantum mechanical treatment of the solute and treat solvents as discrete entities around the solute. They are strongly suggested when interactions between solvent and solute need to be characterized, as in the case of strong hydrogen bonds or coordination to heavy metals, but demanding in terms of resources. The nuclear motion of the solute can be simulated using molecular dynamics or multi-scale models [111]. Mixed methods are probably the best chemical option, although they should be chosen and set-up wisely to provide accurate results at affordable costs.

3.3 Ensemble properties

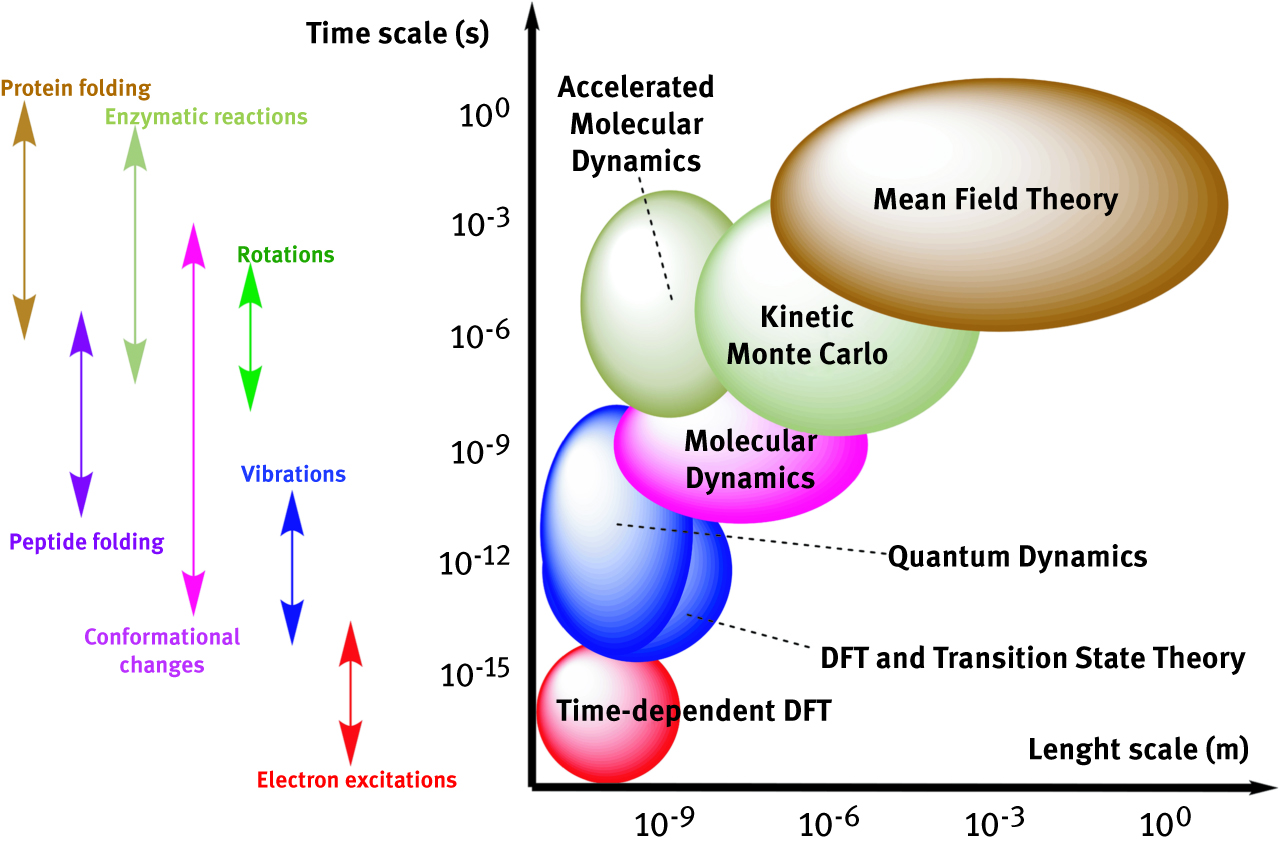

Physical observables represent macroscopic bulk properties of a chemical sample. Simulating those properties at microscopic level requires the average of all the possible states of a chosen ensemble. The taxonomy of statistical thermodynamics encompasses some notable ensembles for N-particle systems: microcanonical or NVE (constant N, volume and energy), canonical or NVT (constant N, volume and temperature), grand canonical or μVT (constant chemical potential, volume and temperature), isoenthalpic-isobaric or NPH (constant number of particles, pressure and enthalpy), isothermal-isobaric or NPT (constant N, pressure and temperature of the system). Calculating all the possible states within an ensemble is impossible, thus few clever simplifications are normally introduced, in order to combine accuracy with computational feasibility. Dynamics methods listed below are excellent examples of methods working on ensemble properties of many-particle systems. Molecular Dynamics, Langevin Dynamics and Quantum Dynamics are particularly suitable for heterogeneous systems, since they are composed of different phases, thus tend to be more affected than homogeneous systems by the multi-scale complexity of the system: the kinetics of diffusion-controlled reaction, for instance, is controlled by particle transport phenomena like diffusion, convection, migration, adsorption and desorption. Chemical reaction happening at the surface of metals, alloys or minerals are many and diverse. The knowledge of the principles ruling transformations in heterogeneous catalysis will allow one to “tailor” a catalyst to carry out the target transformation sought [124]. Figure 6 relates schematically the dimensionality of chemico-physical phenomena to the length/time scale of computational methods [125]

Multi-scale computational methods most frequently used associated to time-scales of chemico-physical phenomena.

3.3.1 Statistical thermodynamics

The calculation of the Hessian matrix (second derivative of energy with respect to atomic coordinates) leads to the recovery of force constants, that can be used to the simulate infrared (IR) spectra [89] and intensities; Raman spectra [89] can be obtained this way when Raman intensities are calculated for differentiation of dipole terms with respect to an external electric field (E). Clearly, obtaining first derivatives is less time-consuming than calculating superior orders in the expansion. MP2 and some DFT methods (e. g., GGA like BP86, B97D) in combination with medium-to-large basis sets usually simulate vibrational spectra with a maximum average error of 10–50 cm−1 versus spectroscopic experiment, while techniques like CCSD(T) can deliver much better results [49]. Simulations can also include the solvation effect through the methods seen before. These simulations might help synthetic chemists to explain the structure of unknown compounds through selection rules and fingerprint matching and assign calculated atomic motions to experimental fundamental or overtone bands of known compounds. In addition, vibrational analysis of harmonic modes and statistical thermodynamics afford a straightforward and convenient link from single-molecule electronic structure and potential energy to molar thermodynamic properties (zero-point energy (ZPE), thermal energy (E), enthalpy (H), entropy (S) and Gibbs free energy (G)) through partition functions [15]. Since most methods to calculate electronic structures feature analytic second derivatives, this is also a computationally advantageous approach [45]. Partition functions are generated in the framework of the ideal gas approximation as functions of the temperature (T) and volume (V) for the translational partition function. q(V,T) = qele(T)·qtra(V,T)·qrot(T)·qvib(T). In solvent phase rotations are substituted with liberation contributions and translations with liberational contributions [111]. Quantum harmonic oscillator [89] is an approximation that holds in most of the cases. When an accurate thermochemistry is expected, however, anharmonic corrections to zero-point energy (ZPE) and roto-vibrational coupling [89] are strongly recommended, since the Morse potential curve deviates sensibly from the harmonic curve at higher internuclear distances, near bond-breaking region [89]. Also, floppy molecules that have low-barrier torsions (hindered rotors) and vanishing-barrier vibrations (free rotors) show a dynamic behavior that falls far from HO approximation. Thus, without correction, large errors would be brought into the entropic partition function (consequently, into Gibbs free energies). Few different correction schemes for low frequency vibrations are available in the literature such as the Pitzer-Gwinn [126], Truhlar [127], McClurg [128] and quasi-harmonic approximations [129, 130, 131].

3.3.2 Mean field theory

Mean field theory is an important branch of condensed matter physics. “Mean field” definition applies to all those theories where the study of a multi-body network of interactions is reduced to an average interaction acting upon the individual under study [44]. In all but the simplest situations (like the Ising model [132]), the mean field simplification is very convenient. Without it, for instance, the calculation of the configuration integral ZN, thus the estimation of the potential energy term U(r) between particles, would become cumbersome in the study of dense fluids [44]. Mean field theory has been originally applied to fluid model (Van der Waals equation)[44], phase transitions, phase transition and ferromagnetism [133], alloys and superconductivity [134, 135]. Similar theoretical treatments were developed for game [136] and queueing theories [137].

3.3.3 Molecular dynamics

Molecular dynamics is a very popular and largely used technique among researchers in many fields. A many-particle system is left evolved in time through phase-space trajectories that respond to classical laws of motion (Newton):

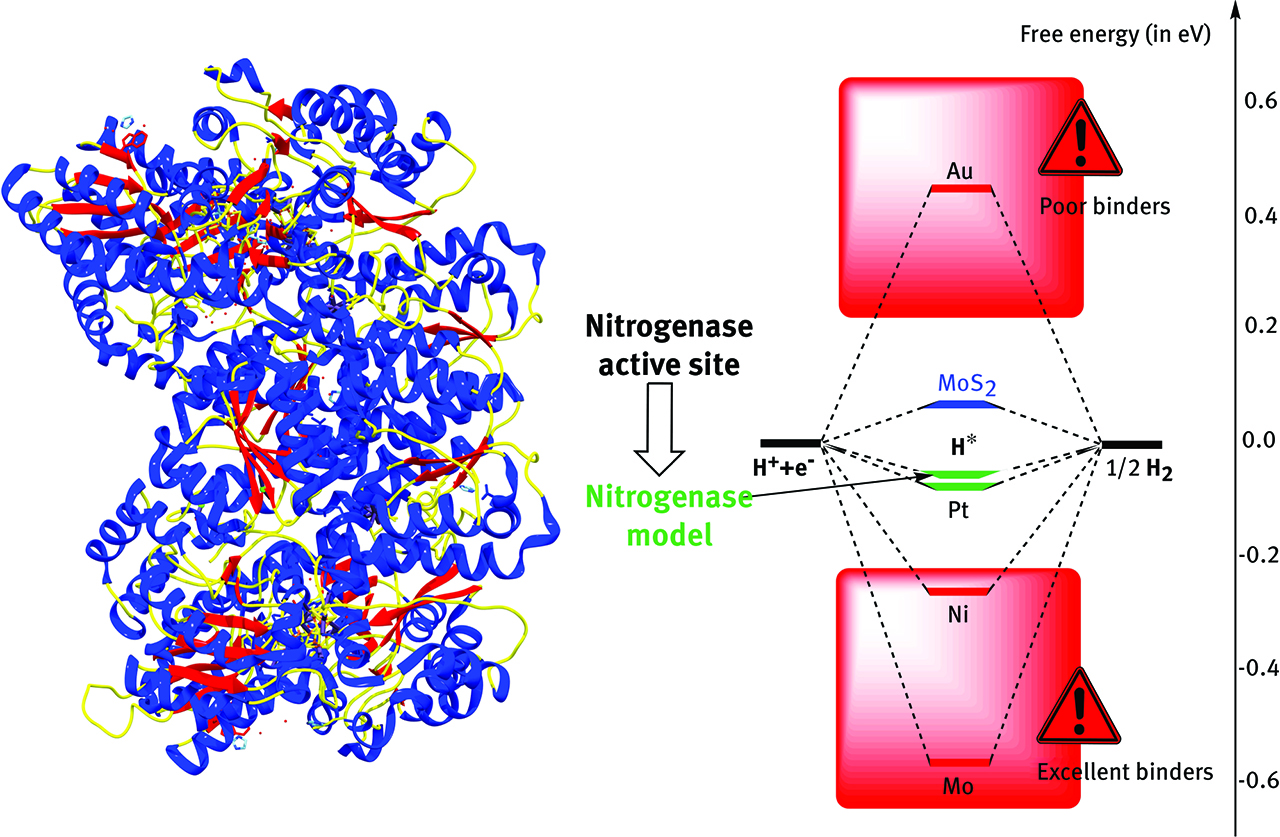

Learning from Nature. Mimicking the active site of enzymes like nitrogenase FeMo cofactor (left) leads to rational design of surfaces evolving H2, like nanosized MoS2.

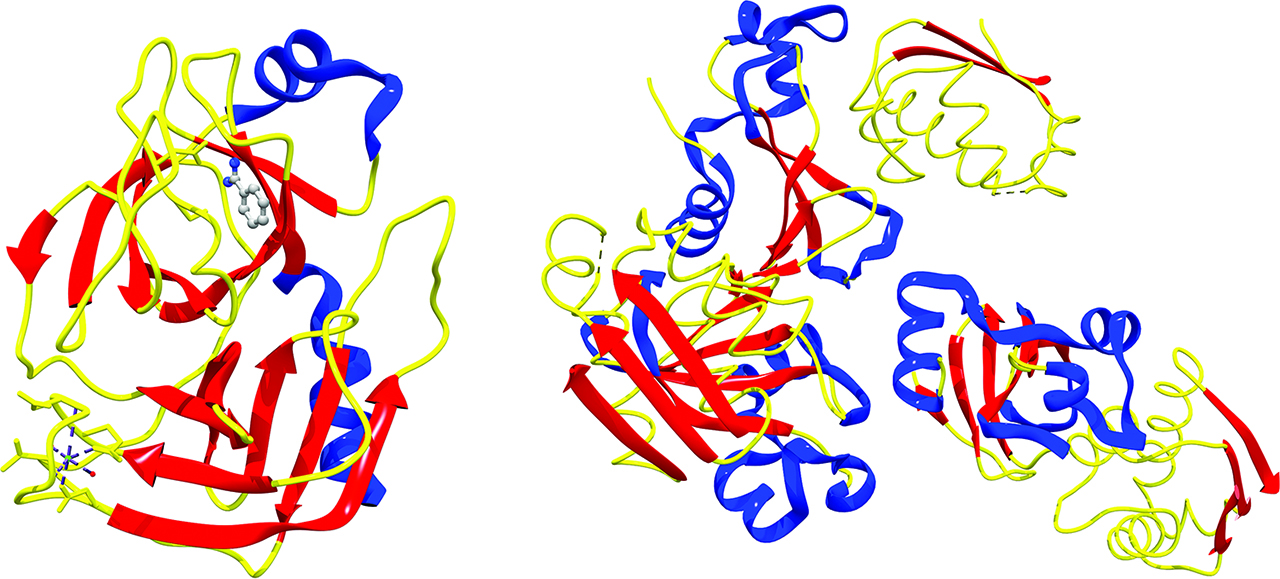

Molecular dynamics, coupled with other techniques like umbrella sampling, conformational flooding, metadynamics, and adaptive force bias, plays a pivotal role in drug discovery as well [148]. Drug discovery deals with the energetics, affinity and selectivity of binding/unbinding events between naturally occurring biological receptors and synthetic inhibitors [148]. These events, however, span microseconds to milliseconds, while ab initio molecular dynamics can effectively sample a few femtoseconds at best [149]. G. de Fabritiis et al. published a paper [150] on the quantitative reconstruction of the binding process between β-trypsin and benzamidine using a Markov state model (MSM) [151]. High-throughput classical molecular dynamics parallelized on clusters of graphical processor units (GPUs) [152] allowed 495 simulations of this binding event of 100 ns each. 187 simulations gave productive bindings with root-mean-square deviation of atomic positions within 2Å compared to the crystal structure [153], Figure 8 left. The estimation of the standard free energy of binding is within 1 kcal/mol from the experimental value [150]. Similar routines are employed to screen and/or improve allosteric drugs (drugs that does not bind the orthosteric pocket of the receptor) and numerous methods to predict allosteric sites and their druggability are described and reviewed in literature [154].

Left, X-ray crystal structure of the Ca2+-enzyme-inhibitor complex between benzamidine and serine protease β-trypsin (PDB ID: 3PTB). Right, X-ray crystal structure of the complex barnase-barstar (PDB ID: 1BRS).

3.3.4 Brownian and Langevin dynamics

Brownian dynamics (BD) is another method used to sample the binding/unbinding pathway of associative events [155, 156, 157]. The motion of molecules of interest is assumed to be Brownian [158, 159, 160], while the solvent is treated stochastically. BD is less time consuming than MD, though its accuracy in reproducing observables strongly depends upon the use of supportive models [161]. An interesting study using BD on the formation of complex barnase-barstar (a ribonuclease and its inhibitor) has been published by A. Spaar et al. in 2006[162]. The complex barnase-barstar is a well-known case for quantitative studies of protein–protein interactions (wild-type and mutant alike). The computational study focused on the characterization of the electrostatic binding region from diffusional regime to enzyme-inhibitor encounter region. The encounter region was modeled after the X-ray crystal structure [163], Figure 8 right. Two regions of preferential binding were authenticated and it was demonstrated that enzymatic mutations alter significantly the populations around these two minima [162]. A particular case of BD is represented by Langevin dynamics. LD complements molecular dynamics calculations with a stochastic treatment of solvent lighter particles perturbing solute heavier particles by the means of averaged frictional forces and collisions [139]. The equation of motion can be written in this case as:

3.3.5 Monte Carlo methods

These methods own their exotic name to the city of Monte Carlo in Monaco, renowned place where stochastic bets play a huge role in the casinos. MC simulations rely on the simulation of a system based on random or quasi-random numbers and can be divided into three main types: direct Monte Carlo, Monte Carlo integration and Metropolis Monte Carlo [139]. Direct MC uses random numbers to simulate events. MC integration calculates integrals on random numbers. Metropolis MC is based on building statistically- dependent configurations through Markov chains. The probability of each new configuration is built upon the probability of the previous configuration. Markov chains are normally ergodic: the conditions of irreducibility (every configuration can be accessed from any other configuration within a finite number of steps) and non-periodicity the same configuration does not repeat except after a fixed number of steps) are satisfied [139]. The functions p(X,t) that correlate the probability of occurrence of a certain configuration (X) at time t are called master equations [139]. MC simulations are usually carried out in NVT ensembles, but Metropolis MC can be used in NPT [165] or μVT [166] ensembles as well. MC methods are mostly used to calculate static properties of a system under study. Monte Carlo methods including quantomechanical treatments are called variational Monte Carlo, diffusion Monte Carlo, path-integral Monte Carlo [139]. Another interesting example is represented by Schaupen and Lewis’s work on molecular imprinted polymers (MIPs). MIPs are artificial polymeric receptors (“plastic antibodies”) synthesized using monomeric units assembled via cross-linkers and template effect [167]. They have antimicrobial, antiviral and anticancer applications [167]. Schaupen and Lewis employed the software ZEBEDDE (zeolites by evolutionary de novo design) to simulate an evolutionary growth of a MIP around selected templating molecules [168]. Nicotine and theophylline were chosen as templating agents. Random combinations of monomers/cross-linkers were allowed to grow around the templates only if their interactions with them were favorable (Figure 6). The results of these growths were optimized using molecular dynamics. Canonical Monte Carlo simulations were performed with the Sorption software included in Materials Studio and used to characterize various grown imprints and their bindings specificity [168]. The calculations showed that the imprints built this way show a remarkable preference to bind theophylline over similar substrates.

3.4 Transition state theory

H. Eyring, M.G. Evans and M. Polanyi proposed this theory in 1933 [169]. Transition structures are mathematical constructs of dynamical instability, dividing surfaces between short-time intrastate (within basin) from long-time interstate dynamics (basin to basin). They possess 3N-7 vibrational degrees of freedom, where the missing degree represents the reaction coordinate. Thus, transition states (TS) are not real structures and many scientists refers to TS-derived thermodynamics as talking of transition state-derived thermodynamics as quasi-thermodynamics [170]. Fundamental requirement of TST is that reactants (or products) and connected transition structures are thermally equilibrated [170]. Several minimization algorithms are available to locate transition structures: steepest descent, Newton-Raphson, rational function optimization, direct inversion of iterative space (GDIIS and GEDIIS) and synchronous transit-guided quasi-Newton (STQN) [171]. The immediate purpose of Eyring-Polanyi equation is to calculate (or estimate at the very least) rate constants for chemical reactive events. Conventional Transition State Theory (CTST) usually provides an upper-bound estimate of experimental reaction rate constants [170, 172]. Within this approach, the transition surface is placed at the saddle point and 100 % crossing-over efficiency is assumed between reactants and products. The variational optimization of the dividing surface in order to minimize re-crossing leads to the Variational Transition State Theory (VTST) [170, 173, 174, 175, 176]. VTST and its variants usually produce much better agreement with experimental kinetics than CTST [172]. The program POLYRATE [177] implements several variational approaches (e. g., Canonical VTST, Improved Canonical VTST, Microcanonical VTST), as well as several quantum tunneling corrections for light atoms. As a consequence of the dual particle-wave nature of matter, light particles like electrons or protons can “tunnel” through potential energy barriers [178, 179]. De-Broglie equation predicts a wavelength of ~27 Å associated to an electron and a ~0.6 Å wavelength associated to a proton moving with kinetic energy of 20 kJ/mol. Experimental signs of tunneling effect usually entail strong H/D isotopic effect, non-linear behaviors of the Arrhenius equation and temperature independence of the reaction rate. Examples of electron tunneling can be found in semiconductivity, superconductivity, scanning microscopy and biological phenomena related to charge transfer [180]. The first experimental proof of tunneling in a chemical reaction came from F. Williams’s work [181]. There are many experimental evidences claiming tunneling effects of light atoms like protons in elimination reactions [182]. Heavier atoms like carbon or nitrogen or systems with small reduced masses can experience tunneling effect as well, in reactions like conformational changes [183], isomerizations [184] and ring expansions [185]. The computation of tunneling effects is generally accomplished with accurate multidimensional derivations of WKB method [186], like the small-curvature (SCT), the large-curvature (LCT), the optimized multidimensional and the least-action tunneling approximations [170, 187]. The inclusion of a multiplicative factor, αT, called transmission coefficient, takes care of the corrections to the Eyring equation that relate to effects like tunneling, for instance. The inclusion of the transmission factor into the calculation of rate constants (therefore reaction equations) improves the goodness of calculated reaction rates versus experimental [170, 172, 188]. The following equations show the analogy between transition state theory and experimental kinetic laws in calculating rate constants (for standard state of 1 mol/L): (a) Eyring-Polanyi equation, (b) E-P equation with separated enthalpic and entropic terms and (c) Arrhenius law.

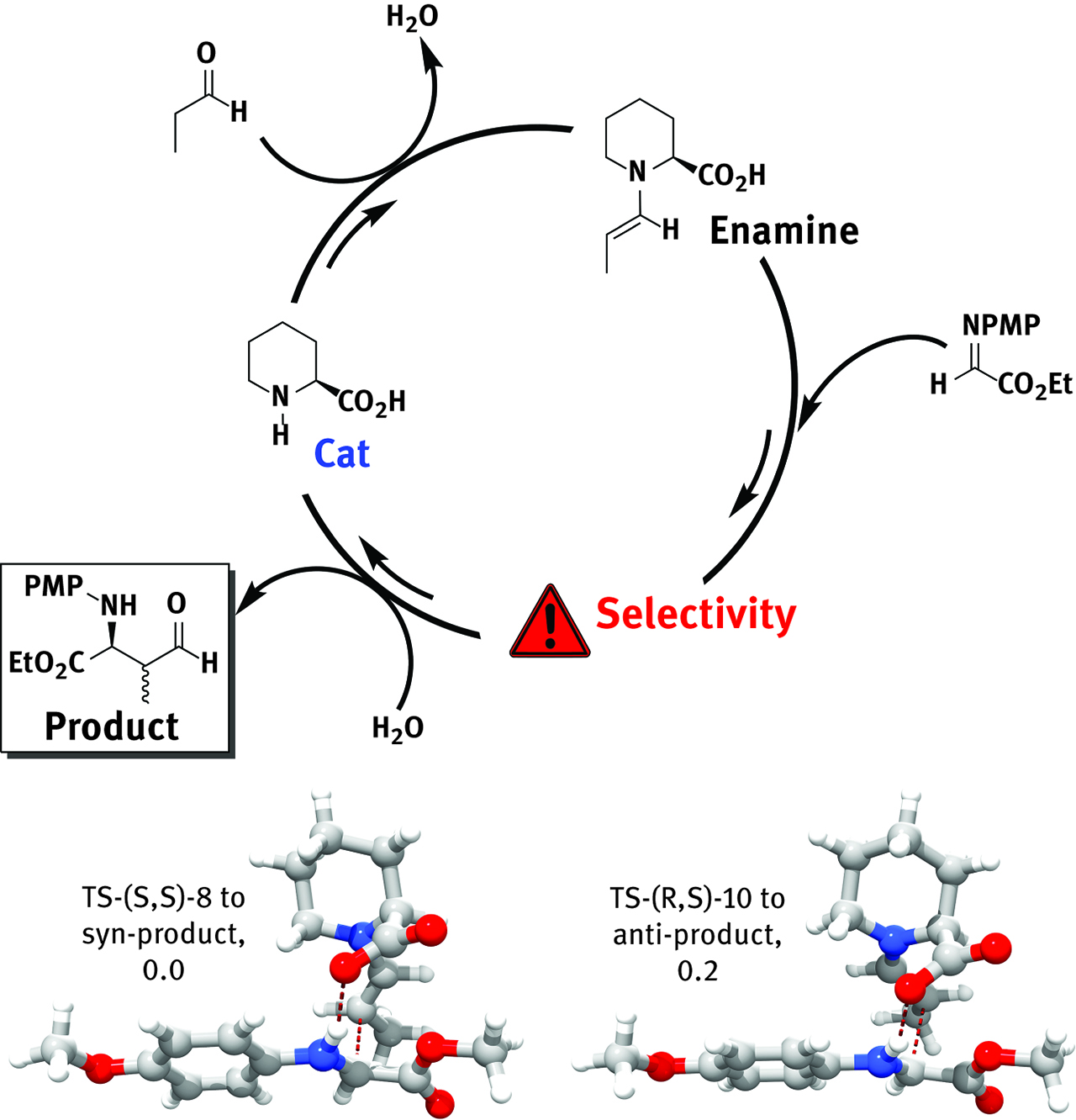

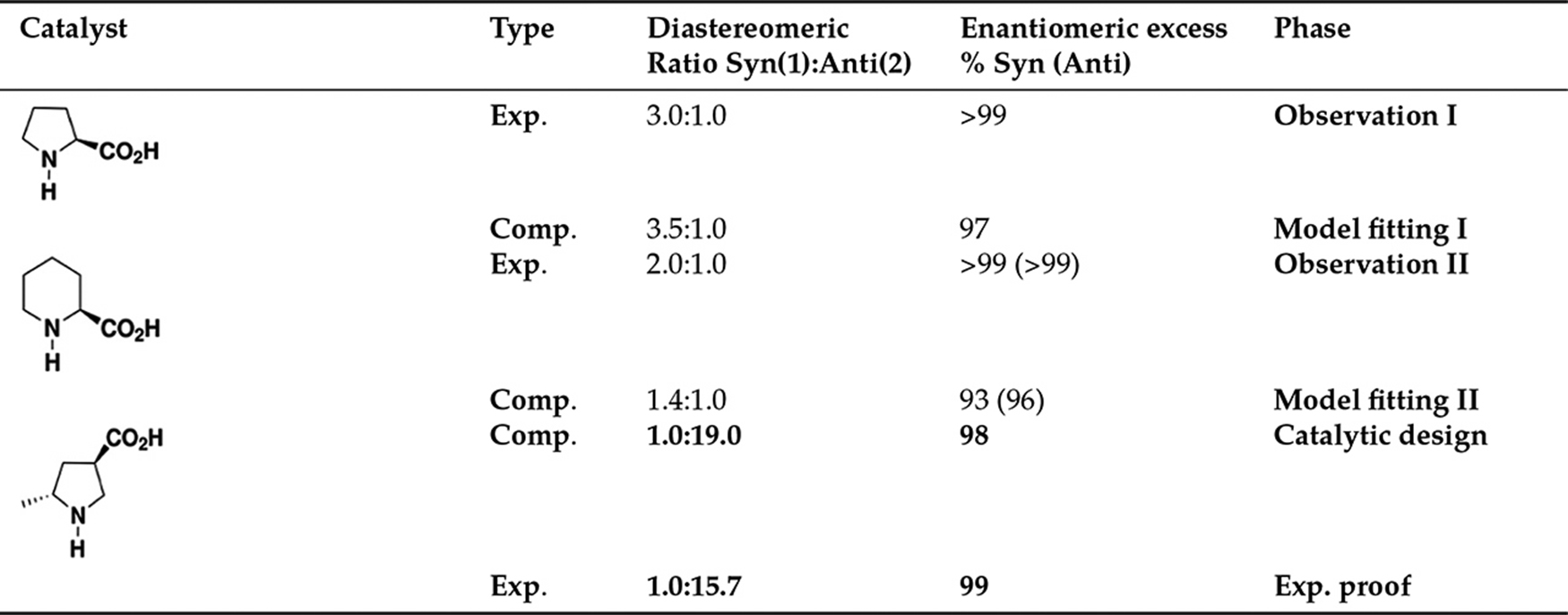

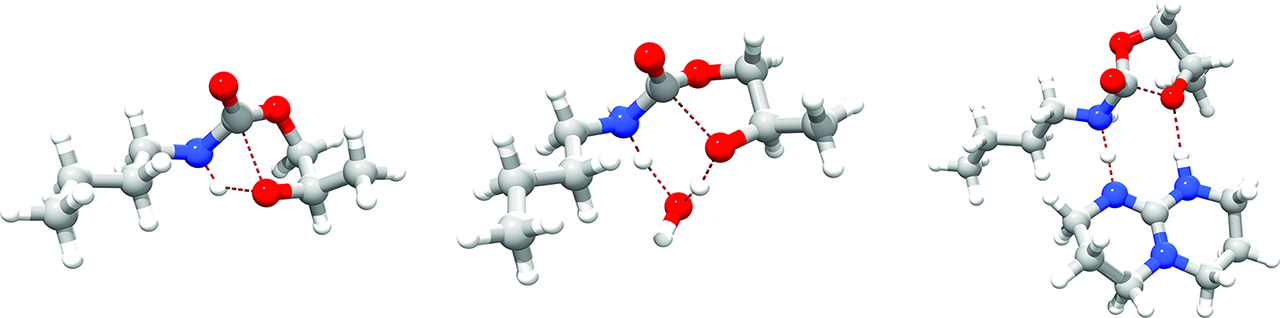

Transition state theory provides valuable kinetic discrimination of reaction-controlled events, alias events that need to cross an energy barrier. The first predictive use of transition state theory in organic chemistry involved the electro-cyclic ring opening of 3-formylcyclobutene; computational insights predicted for the latter system an unusual reactivity compared to its congener 3-methylcyclobutene [189]. The Hajos-Parrish reaction was the first organocatalysis to be studied from first principles [190, 191, 192]; yet again transition state theory proved to be an invaluable tool in uncovering the energetic of the stereoselection between the more stable s-trans geometry (3.5 kcal/mol) and the less stable s-cis [193]. The first example of computational design was applied to selective Mannich-type reactions. The reaction between propionaldehyde and N-PMP-protected α-iminoethyl glyoxylate is catalyzed by (S)-proline and affords Mannich products of syn configuration (syn:anti 3:1, 99 % enantiomeric excess, entry #1 in Table 5). K.N. Houk, C. Barbas et al. produced a computational model of the reaction at HF/6–31G* level in 2006. Transition state theory provided an excellent estimation of the observed diastereoselectivity, 3.5:1, and enantiomeric excess, ~95%[193]. They produced a second computational model where (S)-pipecolic acid replaced (S)-proline as active catalyst of the reaction (Figure 9 and entry #2 in Table 5) and noticed that a loss of diastereoselectivity in Syn(1) product was taking place in favor of Anti(2) product. Targeted catalytic design, based on the insight built during this strategic approach, lead to the first computational design of an organocatalyst in 2006. The catalyst, an artificial aminoacid (entry #3 in Table 5), was designed at HF/6-31G* level of theory to afford selective anti-Mannich reactions, a completely opposite reactive pathway in this type of systems. The predicted outcome of the reaction, 5:95 syn:anti and 98 % ee, were perfectly matched by the successive experimental findings, 6:94 syn:anti and 99 % ee.

Schematic representation of Barbas-Houk’s Mannich-type reaction discussed in this section (top). Transition state theory lead to crucial observations (bottom) concerning structures and energetics that sparked computational design of a new catalyst with desired properties.

The strategy to catalytic design. Entry #1 shows the data for the Mannich-type reaction catalyzed by (S)-proline, entry #2 shows those for the reaction catalyzed by (S)-pipecolic acid. Computation designs experiment in entry #3.

While many other excellent examples of synergistic theory-synthesis approaches in chemistry can be found in literature [194, 195, 196, 197, 198, 199, 200, 201, 202, 203, 204, 205, 206, 207, 208], we report here a very interesting paper published by A. Kleij, C. Bo et al. on the use of triazabicyclodecene (TBD) as a organocatalyst of chemoselective ring-opening of cyclic carbonates to afford N-aryl carbamates in cheap and mild conditions [209]. Carbamates are products of CO2-incorporation. Greenhouse gases (GHG) like CO2 derived from anthropogenic activities are held responsible for the global warming scenario [210, 211, 212, 213, 214]. Sequestrating these gases from the atmosphere and incorporating them in building blocks for fine chemistry is highly sought after [215, 216, 217]. DFT-based (B97-D3/6-311G**/SMD) methods as implemented in G09[98] helped to uncover a favorable proton-relay mechanism as the main source of the fast catalytic effect of TBD at room temperature (Figure 10); two hydrogen bonds imprint a 8-membered ring transition state and lower considerably the barrier of activation at the rate-determining step. Two competitive pathways, namely the direct nucleophilic attack of the amine onto the cyclic carbonate and water-assisted pathway, are either kinetically unfeasible or not as effective as TBD (Figure 10). The crucial contribution of this proton-relay switch has been counter-checked by experiment: replacing TBD by methylated TBD (MTBD) leads to much poorer catalytic effect [209].

Transition structures for ring-opening of a cyclic carbonate enhanced by n-butylamine: left, non-catalyzed (ΔG‡ = 33.3 kcal/mol), center, H2O-catalyzed (ΔG‡ = 24.2 kcal/mol) and right, TBD-catalyzed (ΔG‡ = 18.2 kcal/mol).

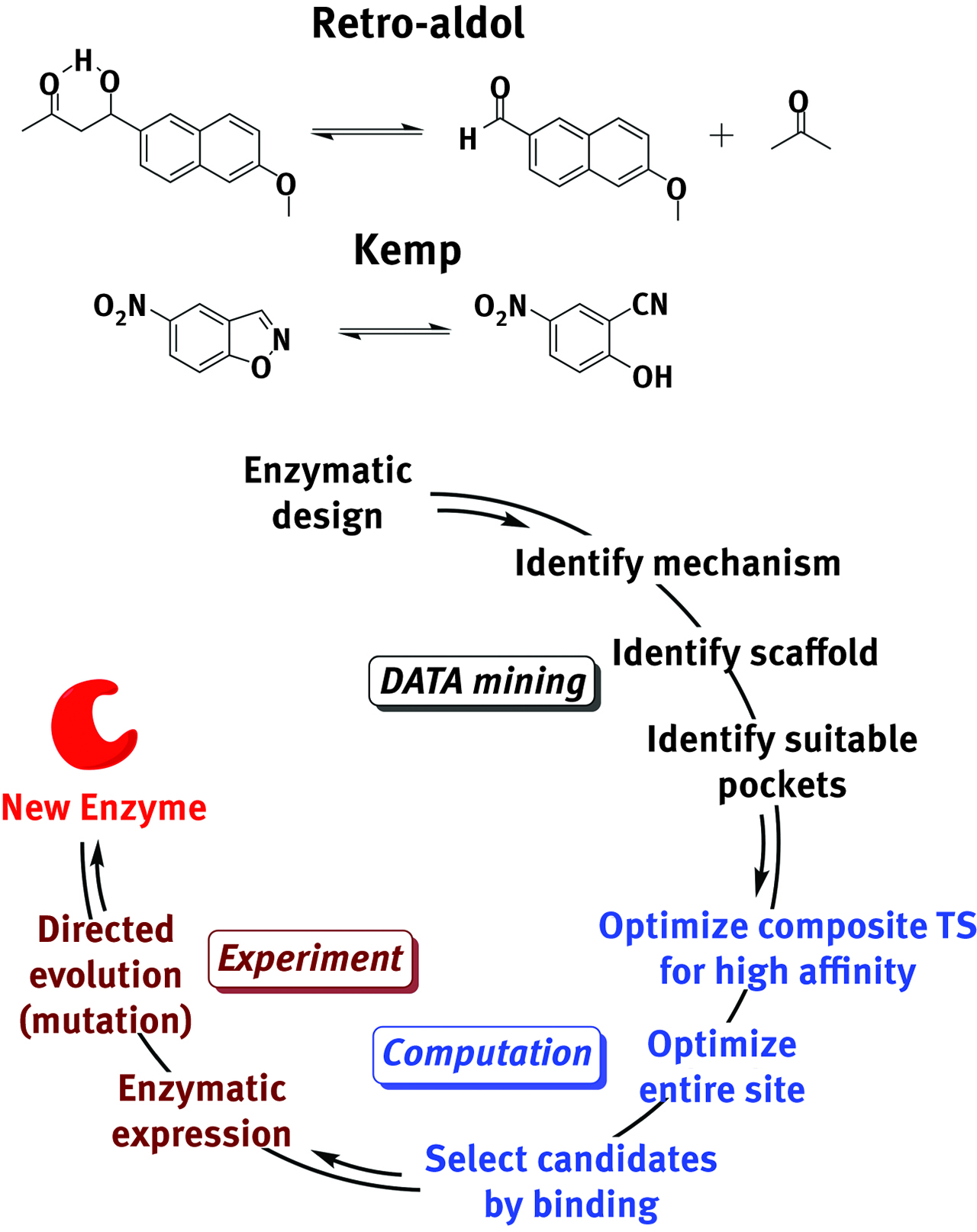

A priori design of enzymatic pockets relies on transition state theory as well. Theozymes are theoretical catalysts tailored by optimizing the transition state of the reactants in a non-catalyzed reaction [218]. Though natural enzymes are molecular machines of unmatched efficiency in binding and transforming several substrates with high selectivity, synthetic enzymes can be designed to catalyze reactions unknown to natural enzymes. This is the case of the retro-aldol dissociation reaction of 4-hydroxy-4-(6-methoxy-2-naphthyl)-2-butanone [219], the Kemp rearrangement reaction of a benzisoxazole [220] and the Diels-Alder condensation between 4-carboxylbenzyl trans-1,3-butadiene-1-carbamate and N,N-dimethylacrylamide [221]. The group employed a sequential methodology involving data-mining, predictive design (Rosetta hashing algorithm [222]), transition state optimizations, selection of best leads and finally expression and directed evolution to generate synthetic enzymes. The strategic approach and the exceptional results of such computationally-assisted design are reported for the first two reactions in Figure 11 and Table 6, respectively. An experimental technique that could be conceptually linked to transition state theory is femtosecond spectroscopy. This technique allows pulsing wave-packets on a molecule by the means of an ultrafast laser. A vibrational normal mode of interest is excited and the structure rearranges trough an activated complex to the formation of the desired product. This spectroscopy allows the accurate mapping of the entire surface and its dynamics from the reactants to the products, thus providing important experimental details on the characteristics of the “near transition” region [11].

Nature does it better, but scientists are closing the gap. The route to “artificial” enzymes is an interplay ground for statistical techniques, theoretical computation and targeted synthesis.

Experimental activity and kinetic parameters of mutated artificial enzymes designed by computational methods.

| Design | Reaction | kuncat | kcat | KM (mM) | kcat/KM (M−1s−1) | kcat/kuncat |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RA60 | Retro-aldol | 3.9·10–7 min−1 | (9.3 ± 0.9)·10–3 min−1 | 510 ± 33 | (0.30 ± 0.06)·10–3 | 2.4·104 |

| RA61 | Retro-aldol | 3.9·10–7 min−1 | (9.0 ± 1.0)·10–3 min−1 | 210 ± 50 | (0.74 ± 0.11)·10–3 | 2.3·104 |

| R7 2/5B | Kemp | 1.16·10–6 s−1 | (1.20 ± 0.08) s−1 | 0.86 ± 0.08 | 1.388 ± 44 | 1.03·106 |

| R7 10/11 G | Kemp | 1.16·10–6 s−1 | (1.37 ± 0.14) s−1 | 0.54 ± 0.12 | 2.590 ± 302 | 1.18·106 |

3.5 Kinetic models

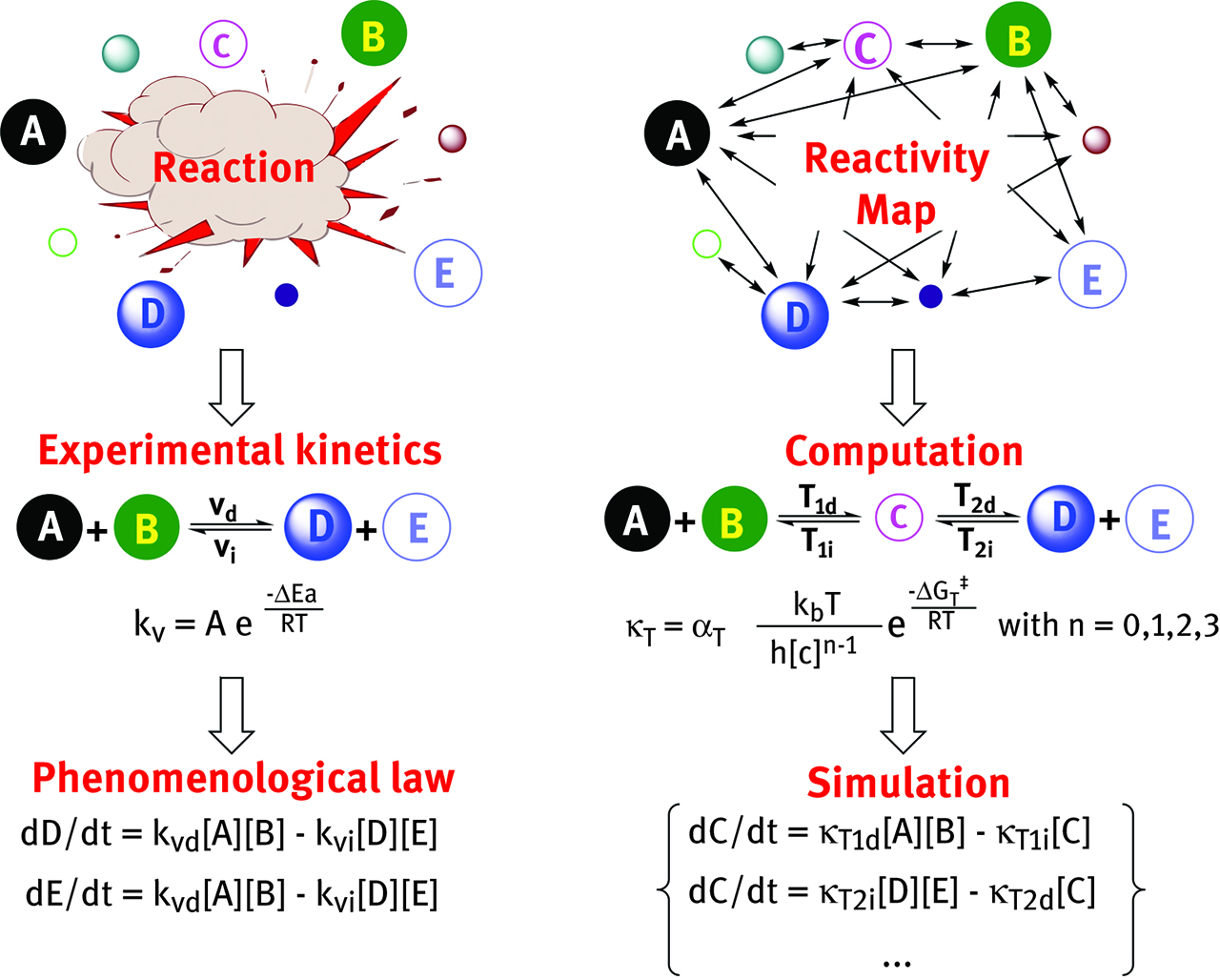

Complex multi-step chemical reactions are the direct result of parallel, competitive and consecutive events establishing an intricate network of simultaneous equilibria in the medium: within this network, species appear and disappear following (sometimes) complex phenomenological laws [223]. Experimental kinetic laws use rate constants derived from macroscopic quantities like activation energies (e. g., Arrhenius [223] law) to average microscopic quantities deriving from particle transport and collisions (continuum → microscopic, Figure 12).

The different approach of experimental kinetics versus kinetic model.

A kinetic model uses integrated system concentrations over time of microscopic quantities (i. e. transition state thermodynamics) on elemental events to simulate the macroscopic reaction (microscopic → continuum, Figure 12): it is used to complement and corroborate mechanistic proofs derived from potential and free energy surfaces. In principles, a kinetic model should allow the accurate recovery of information on selectivity, turnover number and kinetics ↔ reactivity ↔ structure relation in conditions where Curtin-Hammett principle [224], Winstein-Holness equation [224] and steady-state approximation [223] are not always so easily applicable.

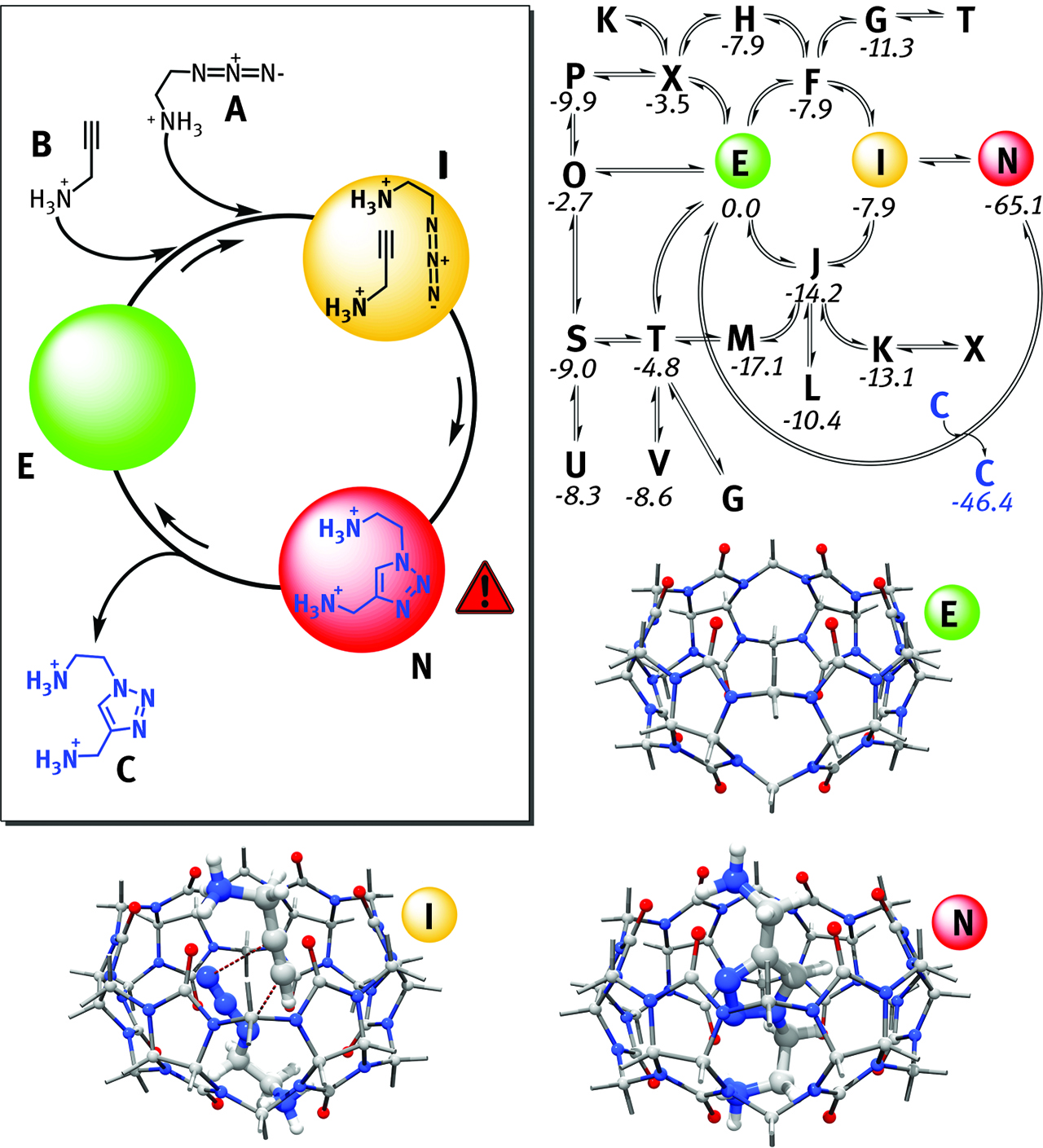

Kinetic models abide the principle of microscopic reversibility and represent a strong direct link between pure theory and experiment since they can be compared straightforwardly with plots obtained by experimental kinetics [225]. The higher the number of kinetic equations included in the simulation, the better the agreement of the model versus experiment. Kinetic models are particularly useful to model catalytic reactions, where the rate limiting step(s) may change throughout the reaction following the change in concentrations of the reactants/intermediates [223]. Analytical integration is prohibitive on large systems; therefore one should resort to robust numerical algorithms like Euler, 4th-order Runge-Kutta, Runge-Kutta-Fehlberg, Runge-Kutta-Cash-Karp, Runge-Kutta-Dormand-Prince, Bader-Stoer and Adams’ methods [223]. “Stiff” equations can be efficiently treated with Bader-Deuflhard algorithm [226]. An elegant example of kinetic models has been reported by F. Maseras et al. It concerns the computational study at B97-D3/6-311G(d)/SMD level of theory of a known 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition between propargylamine and azidoethylamine [227], Figure 13. The computed thermodynamic parameters reproduced successfully the experimental findings (ΔG‡ = 27.1 versus 27.3 kcal/mol, for the rate limiting step of the reaction) and the kinetic model helped to re-interpret the experimental mechanism of the reaction in light of the catalytic effect of host-guest encapsulation provided by cucurbit[6]uril (CB6) [227]. Another excellent example has been reported by Maseras et al. The work encompasses the use of non-adiabatic DFT calculations (ωB97X-D) supported by kinetic model in explaining the outcome of photo-activated aromatic perfluoroalkylations [228].

Schematic representation of the dipolar cycloaddition discussed in this section, top-left. Maseras’s pruned network of calculated competing events proves the “combinatorial” approach behind kinetic model, top right. Molecular structures of the most important intermediates in the reaction (bottom).

3.6 Multi-scale models

The idea of a consistent force-field was born in 1968 [229]. The total potential energy of a molecule can be calculated as a function of simple classical laws involving Hooke’s spring law for bonds, periodic laws for dihedral torsions, Lennard-Johns equation for Van der Walls interactions and Coulomb law for charge interactions [230]. The potential energy can be further related to energy minimization, intrastate and interstate dynamics and random moves (Monte Carlo)[230]. Multi-scale models were originally proposed in 1976. They allow the optimization and calculation of properties of very large systems (encompassing hundreds of thousands of atoms); thus they have been very useful in the calculations of large peptides, proteins and enzymes like lysozyme [231]. The general idea behind this method is that the chemical system under study can be divided into different layers, calculated separately using different methods. Larger areas that do not take direct part in the reaction (e. g., protein side chains) are calculated using inexpensive classical treatments like molecular mechanics (MM), while active site of reaction can be treated with higher-level quanto-mechanical theory (QM). For such reason these methods are called QM/MM methods. The energy of a total system, ESys, can be defined as:

ESys = EQMQM + EMMMM + EQMinterQM/MM + EMMinterQM/MM

The steric and polarization effects of the classically-treated low-level layer are contained in the term EMMMM, while EQMQM contains the quantum mechanics energy of the high-level layer. EQMinterQM/MM is called electronic embedding, while EMMinterQM/MM is called mechanical embedding. Different methods have different ways to calculate the latter two parameters. Two of these QM/MM methods are available and implemented in computational software: IMOMM [232] and ONIOM [233] methods.

There are excellent reviews [234, 235] and highlights [236] and commentaries [194] on QM/MM calculations in asymmetric catalysis via organometallic species; these works include reactions like hydrogenation, hydroboration, epoxidation and hydroformilation. F. Schoenebeck et al. used ONIOM(B3LYP/6-31+G(d)/LANL2DZ:HF/LANL2MB) level of theory to design a new small-bite phosphine ligand able to enhance the reductive elimination of PhCF3 from Pd(II) complexes. Contrarily to accepted knowledge, the group demonstrated computationally that the reactivity was not correlated with the bite-angle of the phosphine, rather with the repulsive electrostatic interactions between the phosphine and the leaving group (namely CF3) [237]. Calculations provided a good estimate of the activation enthalpy for elimination of PhCF3 in [(Xantphos)Pd(CF3)(Ph)], 25.1 kcal/mol versus the experimental value of 25.9 ± 2.6 kcal/mol [238]. Schoenebeck’s new complex [(dfmpe)Pd(CF3)(Ph)] (Figure 14), afforded an activation enthalpy range of ΔH‡ = 20.7–23.5 kcal/mol, depending on various theories [237]. Driven by the successful computational design, the group synthesized [(dfmpe)Pd(CF3)(Ph)] and demonstrated that the elimination of PhCF3 is complete after 3 hours at 80 °C after 100 min. Kinetic experiments by NMR measured the activation enthalpy as ΔH‡ = 27.9 ± 1.6 kcal/mol [237]. Another challenge for QM/MM methods is represented by designing chemotherapeutic agents with in vivo high affinity and selectivity towards target DNA helix. A synergistic approach between molecular dynamics simulations, QM/MM calculation, force fields and experimental resources (i. e., high-resolution structures of nucleosome-drug adduct) has been applied to further the knowledge on binding location, binding modes and selectivity of metallo-drugs versus DNA and proteins during these last years [239].

Bite-angle is not the issue, says theory. Schoenebeck’s designed palladium complex reductive-eliminates PhCF3, despite its small bit-angle phosphine. The figure shows the transition structure for such elimination (bond distances in Å).

3.7 Wavefunction analysis

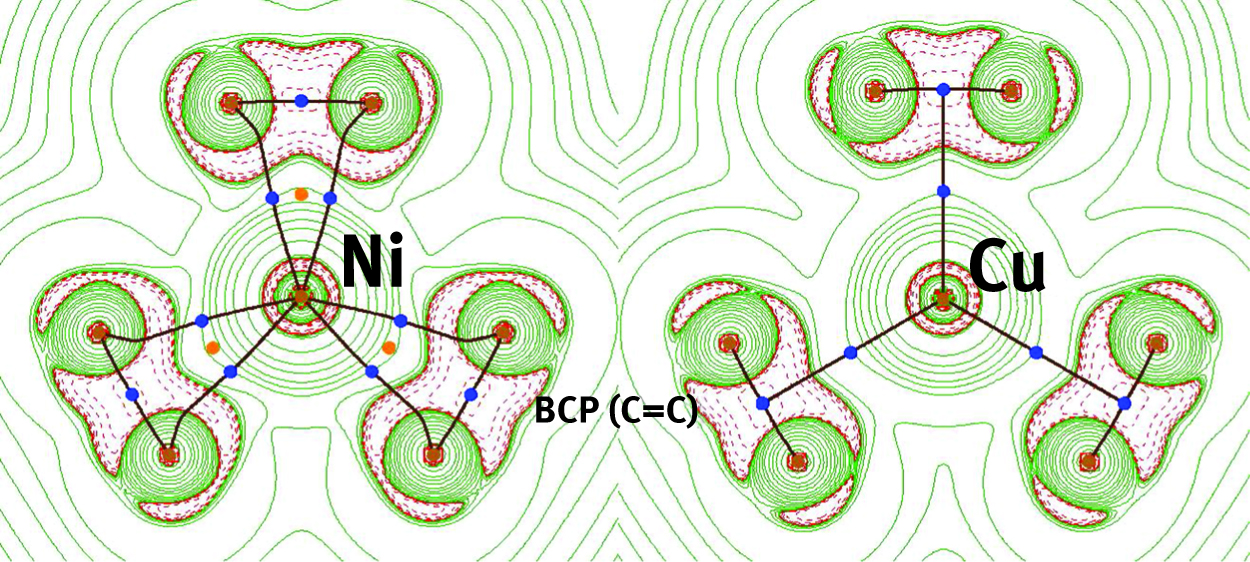

Optimized wavefunctions at the stationary points,

Molecular graphs of Ni(η2-C2H4)3, left, and Cu(η2-C2H4)3+, right, overlaid with their respective Laplacian maps, ∇2ρ(r). The structures have been calculated using B3PW91 in conjunction with the non-relativistic full-electron DGDZVP basis set. Blue dots represent bond critical points, or BCP (3,-1), orange dots represent ring critical points, or RCP (3,+1), and brown dots represent nuclear attractors (3,-3). Within green zones kinetic energy density dominates and the electron density is depleted {∇2ρ(r) > 0}. Within red zones potential energy dominates and the electron density is concentrated {∇2ρ(r) < 0}.

Among others, topological analysis functions are very useful and routinely used by chemists: electron localization function (ELF) [250, 251], localized orbital locator (LOL) [252, 253], reduced density gradient (RDG) [254] and source function [255]. ELF was used by M. Kaupp et al. to explain the bond in another uncommon compound, HgF4 [256]. The bond pattern, consistent with the representation of a low-spin d8 complex, defines mercury as real transition metal, rather than a post-transition element. Mercury in high oxidation state was theoretically predicted by Kaupp et al. to be stable as HgF4 since 1993[257, 258, 259], with weakly-coordinating ligands like SbF6- [260] and as HgH4 by P. Pyykkö et al. [261] and finally isolated and characterized spectroscopically in matrix in 2007 [256].

3.8 Chemoinformatics and machine-learning

Under the name of chemoinformatics falls a large and diverse number of different disciplines spanning from computational chemistry, mathematics, and statistics, data-mining to informatics. The accepted goal of chemoinformatics is to fabricate Hit-to-Lead-to-Candidate [262] predictions on unknown molecular systems using validated and statistically significant data obtained from libraries of known properties and chemical behaviors. Computational chemistry is primarily used in pharmaceutical industries to complement, integrate or prioritize targeted drug synthesis via virtual libraries and virtual screening [263]. Virtual libraries are collections of virtual molecules that can be studied to generate new molecule or to hypothesize chemical properties. Such libraries should be composed of large and fitting populations. These libraries can be increased using “trained” Markov chains like in fragment optimized growth (FOG) algorithm [264]. Virtual screening is the analysis of database of chemical compounds to identify viable candidates. Virtual screening uses in silico techniques like molecular docking [263]. Combinatorial and high-speed syntheses are used as lead or complementary synthetic methods to chemoinformatics, since they are designed to generate or screen large libraries of compounds [263]. High-throughput computational modeling uses languages like the Chemical Markup Language (CML) and the Simplified Molecular-Input Line-Entry System (SMILES). Physico-chemical properties are normally represented by descriptors: a descriptor is a compact transcription of a certain property within a sample or library of species into mathematical language. The goal of a descriptor is to convey the essence of the quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) [265]. The complexity of the property described by the descriptor increases with the dimensionality of the descriptor itself: 1D-descriptors deal with simple macroscopic bulk properties like molecular weight, while 3D-descriptors capture the essence of the donor-acceptor interaction and binding affinity (polar surface area for instance). 1D-descriptors are used as first-approach filters, while 2D-descriptors (also called fingerprints) seem to work well in reproducing many chemical properties [266]. GRID is an interesting program for drug discovery applications and ADME predictions related to pharmacokinetics [43]. QSAR approach is used extensively in pharmaceutical chemistry [267, 268], but its use in catalytic applications involving small molecules results to be still sparse. An excellent example of QSAR, or in this case QSSR (quantitative structure-selectivity relationship), is represented by M.C. Kozlowski et al.’s work [269, 270]. The group aimed to correlate the structure of in situ-generated zinc catalysts (ZnBr2 + β-aminoacids) with the enantioselectivity of the asymmetric reduction of benzaldehyde to related alcohol. The group generated a grid-based QSAR approach whose descriptors provided a correct replica of the enantioselective footprint of catalysts under study. Since every transition structure have been generated using computationally low-demanding PM3 theory, this model provides important insight at very affordable costs [269].

Machine learning is a branch of computer science that deals with “supervised” or “unsupervised” learning of a machine. The goal of this discipline is the development of artificial intelligences, networks that mimic the human mind’s capability to learn, store and relay data using electrochemical signals [271]. Network analysis, for instance, has been applied in organic synthesis since the Sixties, when E. Corey created software called Logic and Heuristics Applied to Synthetic Analysis (LHASA). The software was meant to suggest the sequences of postulated steps in a de novo synthesis, based on a database of retrosynthetic rules [272]. In 2005, B. A. Grzybowski et al. developed in 2005 a revolutionary concept of a network connecting molecules (“nodes”) by chemical reactions (“arrows”)[273]. The network contains about 6 million organic compounds interrelated by 30,000 retrosynthetic rules. The group focused on the evolution of this network, the relations between connections in the network and reactivity and optimization/pruning of the network itself. The software developed after this network was called Chematica. It can successfully generate and optimize synthetic pathways [274, 275] and detect synthetic pathways leading to dangerous chemicals [276]. Other interesting examples on chemoinformatics and machine learning (i. e., artificial neural networks) can be found in literature [277].

4 The future: Conclusions and author’s perspectives

A brief evolution of the rational way of doing chemistry has been presented throughout this chapter. General principles and descriptions of rational improvements to chemistry have been introduced and described to provide the reader with a general background on this topic. Paradigmatic examples on the synergistic use of theory, spectroscopy and synthesis have been provided to show how the rational approach is more than advantageous in understanding, developing and planning new chemistry. It is certain that the evolution of transistors, semi-conductors and miniaturized circuits will provide a boost in the hardware performances (thus an incentive to study large and more complex systems raising the bar of the overall accuracy) in the next few decades, provided that Moore’s law will still be followed faithfully [278]. Furthermore, once the binary code will no longer hold sway, quantum-bits-based architectures might boost computational power and speed to new, far higher plateaus. At the present days, there are reports of commercialization of quantum architectures (e. g., D-Wave 2X) by Canadian company D-Wave System Inc. [279], but still, room is left for scientific debate and criticism [280, 281, 282, 283, 284]. Software improvements (i. e., implementation of improved routines, compilers, libraries, parallelization and so on) in commercialized computational programs (an extensive list of the major computational software used in chemistry, physics and material science can be found online [285, 286], as well as a list of the programs and suites to prepare input files and visualize output files [287]) will also play a protagonist role in speeding up the chemistry on screen. Technological improvements may also help experimentalists to keep a better and more functional record of their lab experiments; for instance, electronic laboratory notebooks (ELNs) [288] will become excellent platforms to track and share successful and failed synthetic attempts. These data, particularly the failures, when available on electronic supports for unrestricted mining and sharing, will be of tremendous importance in the validation, refinement and improvement of theoretical models on real systems.

Thus, all these betterments will surely contribute to keep the rational momentum of chemistry evolving in the near future. Truth is, the impact of a higher degree of rationality might profoundly influence the way chemistry is taught, discussed and disseminated as well. One of the greatest limitations in scientific fields is that specialized professionals speak different languages [289]. This loss in translation can sometimes be the cause of scientific misunderstandings, disagreements and loss or disregard of crucial snippets of information in shared projects and assignments. Thus, scientific team-work and collaborations [289] will benefit in efficiency from a new breed of chemist, groomed from early academic stages to blend theory, spectroscopy and synthesis (understanding powers and limits embedded in different approaches!) to pursue research duties and interests. Such a figure may deliver more powerful performances than his/her predecessors in academic and industrial environments alike.

Secondly, rational chemistry might lead to a positive relief of the environmental footprint that is a great concern in the modern era. Chemistry can be a double-edged sword: while in the past it has shown that it can improve the quality of life and fuel technology, it has also contaminated nature and its living creatures. The current drive in research funding is to push for the former without creating the latter as a deleterious effect. Though regulated by national agencies, chemical pollution is a transnational problem that leads inexorably to problems like endocrine disruption due to chronic exposure [290]. Paradoxically, since a clean man-made chemical reaction is a reaction that never took place, the concepts of atom-economy and solvent preservation need to be implemented to their fullest. Validated computational techniques could represent a greener and more sustainable way to design catalysts (or electrodes, membranes, polymers and so on) and tune catalytic effects than indiscriminate trial-and-error synthesis. Finally, there is the issue of the economic sustainability. Pharmaceutical companies are already incorporating some of the computational tools [267] presented in this chapter to design new bioactive molecules and pre-screen their biological activity. High-quality computation techniques are indeed less impacting on R&D budgets compared to trial-and-error synthesis. Furthermore, rational design of reagents could shield enterprises from legal internal liabilities deriving from the use and storage of harmful reagents and the stock and disposal of dangerous waste.

References

1 Fowler AC. Mathematical models in the applied sciences. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2004.Search in Google Scholar

2 Melnick R, editor. Mathematical and computational modeling: with applications in natural and social sciences, engineering, and the arts. New York, USA: John Wiley & Sons Inc; 2015.10.1002/9781118853887Search in Google Scholar

3 Ball P. Chemistry: why synthesize? Nature. 2015;528:327–329.10.1038/528327aSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

4 Mortimer CE. Chemistry: a conceptual approach. Belmont, CA, USA: Wadsworth Publishing Co. Inc; 1983.Search in Google Scholar

5 Francl M. The enlightenment of chemistry. Nat Chem. 2015;7(10):761–762.10.1038/nchem.2354Search in Google Scholar PubMed

6 Norris JA. The mineral exhalation theory of metallogenesis in pre-modern mineral science. Ambix. 2006;53(1):43–65.10.1179/174582306X93183Search in Google Scholar