Abstract

Korean coordination allows non-final conjuncts to appear either without a tensed verb as in gapping (aka right-node-raising or right-peripheral ellipsis) or without a verbal tense morpheme as in bare ko-coordination. This study uses an acceptability judgment experiment designed to investigate whether tense mismatches degrade the acceptability of Korean gapping and bare ko-coordination with reference to full coordination. The experimental findings of the study indicate that tense-matched gapping is preferred over tense-mismatched gapping and that tense-matched bare ko-coordination is preferred over tense-mismatched bare ko-coordination. The results of the study also demonstrate that temporal order, whether it is sequential or reverse, does not affect the acceptability of Korean gapping and bare ko-coordination because tense-mismatched violations are symmetric so that they cause to affect all conjuncts. Overall, this study discusses how the phenomena of tense-mismatches are accounted for in full coordination, bare ko-coordination, and gapping. The tense-mismatches in these constructions are due to differences in conjunct size. The conjunct size is TP in full coordination (with two overt Ts) and bare-ko coordination (with a null T in the first conjunct and an overt T in the second conjunct), while it is vP in gapping (with an overt T in the second conjunct).

1 Introduction

The sentence in (1) is an example of English gapping (the term coined by Ross 1970), which is forward ellipsis in that a gapped clause follows its antecedent clause.

| John ate natto, and Mary __ sushi. |

| ‘John ate natto, and Mary (ate) sushi.’ |

The sentence in (2) is the Korean counterpart, which seems to be backward ellipsis in that a gapped clause precedes its antecedent clause. According to Ross (1970), this elliptic phenomenon is classified as an instance of gapping:[1]

| John-i | natto-lul | __, | Mary-ka | sushi-lul | mek-essta. |

| John-Nom | natto-Acc | Mary-Nom | sushi-Acc | eat-Past | |

| ‘John (ate) natto, and Mary ate sushi.’ | |||||

Many linguists have observed that ellipsis permits agreement mismatches with respect to voice, category, and inflections (Bošković 2004; Citko 2018; Lasnik 1999; Sag 1976). For instance, Ross (1970) observes that Russian allows phi-feature mismatches in gapping as follows:

| Ivan | vod-u |

|

i | Anna | vodk-u | pil-a. |

| IvanMasc | water-Acc |

|

and | AnnaFem | vodka-Acc | drank-Fem |

| ‘Ivan (drankMasc) water, and Anna drankFem vodka.’ | ||||||

| Anna | vodk-u |

|

i | Ivan | vod-u | pil-Ø. |

| AnnaFem | vodka-Acc |

|

and | IvanMasc | water-Acc | drank-Masc |

| ‘Anna (drankFem) vodka, and Ivan drankMasc water.’ | ||||||

| (Russian, adapted from Ross 1970: 251) | ||||||

In (3a) the missing verb has a masculine ending, whereas the antecedent verb has a feminine ending, and vice versa in (3b).

With respect to agreement mismatches in ellipsis, there have been considerable debates as to whether Korean gapping allows tense mismatches, as illustrated in (4).

| John-i | caknyeney, | Mary-ka | naynyeney | mikwuk-ulo | ttena-lketa. |

| John-Nom | last.year | Mary-Nom | next.year | US-for | leave-Fut |

| ‘John (left for the US) last year, and Mary will leave for the US next year.’ | |||||

In (4) the two conjuncts are mismatched in tense; the first conjunct includes the temporal adverb caknyeney ‘last year’, which triggers a past tense interpretation of the missing verb, whereas the second conjunct includes naynyeney ‘next year’, which is compatible with a future tense verb.

Regarding tense mismatches in gapping, Ahn and Cho (2006) and others (Kim 2007; Kim and Cho 2012; Park 2009) claim that conjuncts in gapping need not match in tense, which predicts (4) to be acceptable. On the other hand, Chung (2005a) and others (Choi 2019; Kim 2019) claim that gapping does not permit tense mismatches, predicting (4) to be unacceptable. Importantly, all these claims were based purely on informal judgments. More recently, however, Park and Kim (2021) claim that tense-mismatched gapping is unacceptable via a formal experiment.

Further, the issue of whether gapping permits tense mismatches has been discussed with reference to bare ko-coordination (Kim and Cho 2012):[2]

| John-i | ecey | tochakha-ko, | Mary-ka | nayil | tochakha-lketa. |

| John-Nom | yesterday | arrive-and | Mary-Nom | tomorrow | arrive-Fut |

| ‘John arrived yesterday, and Mary will arrive tomorrow.’ | |||||

Until now, there has been no consensus in the literature regarding the level of acceptability of the bare ko-coordination in (5) and its acceptability when aiming for a tense-mismatch interpretation. One group of researchers (Chung 2005b; Kang 2013; Lee and Tonhauser 2010) argues that bare ko-coordination permits the tense mismatch between conjuncts, which predicts (5) to be acceptable; i.e., the first conjunct depicts a past event and the second conjunct depicts a future event. The other group of researchers (Kang 1988; Park 1994; Yoon 1996; Yoon 1997) argues that only the tense-match interpretation is allowed in bare ko-coordination, which predicts (5) to be unacceptable. Let us suppose, for the time being, that the bare ko-coordination in (5) allows tense mismatches; the first conjunct contains a bare verb without an overt tense morpheme, whereas the second conjunct is suffixed with an overt tense morpheme. This difference sets apart bare ko-coordination from full coordination, as in (6), where the verb in the first conjunct is suffixed with the past tense morpheme (y)ess.

| John-i | ecey | tochakha-yess-ko, | Mary-ka | nayil | tochakha-lketa. |

| John-Nom | yesterday | arrive-Past-and | Mary-Nom | tomorrow | arrive-Fut |

| ‘John arrived yesterday, and Mary will arrive tomorrow.’ | |||||

Such a mismatch between form and meaning is one of the reasons why bare ko-coordination has attracted a lot of attention.

In addition, there has been a controversy regarding the role of temporal (i.e., sequential vs. reverse) order between conjuncts on the acceptability of Korean gapping and bare ko-coordination. For example, Chung (2005b) and Lee and Tonhauser (2010) claim that bare ko-coordination with tense mismatches is allowed regardless of its temporal order. On the other hand, Park and Kim (2021) claim that the acceptability of tense-mismatched bare ko-coordination improves significantly when it is presented in the reverse order.

The rest of this paper proceeds as follows. In Section 2, we offer a brief history of tense mismatches regarding Korean gapping and bare ko-coordination. In Section 3, we report a formal experiment of tense mismatches with regard to three types of coordination: full coordination, bare ko-coordination, and gapping. In Section 4, we discuss experimental findings and propose a syntactic analysis of Korean gapping and bare ko-coordination. Finally, we conclude in Section 5.

2 Two types of tenseless coordination in Korean

English does not allow coordination in which one conjunct drops an overt tense morpheme as follows:

| *John [eat rice] and then [drank water]. |

| ‘John ate rice and then drank water.’ |

Given this, it is interesting to note that Korean tense inflection may be optional in the first conjunct of bare ko-coordination, although Korean verbal tense is usually encoded via an overt tense morpheme (Sohn 1995):[3]

| John-i | natto-lul | mek-(ess)-ko, | Mary-ka | sushi-lul | mek-essta. |

| John-Nom | natto-Acc | eat-(Past)-and | Mary-Nom | sushi-Acc | eat-Past |

| ‘John ate natto, and Mary ate sushi.’ | |||||

The first conjunct in (8), even without the past tense morpheme, may receive a past tense interpretation. That is, the two events described in each conjunct may refer to the same time reference, solely depending on the verbal tense of the second conjunct.

Taking this into consideration, Yoon (1997) and others (Kang 1988; Park 1994; Yoon 1996) argue that the tense morpheme in the second conjunct determines the temporal interpretations of both conjuncts in bare ko-coordination. Specifically, Yoon (1997) proposes that the tense morpheme takes the entire coordinate structure as its complement, rather than being suffixed only to the final verb, as schematized in (9).

| [TP | [vP John-Nom | [VP natto-Acc | eat-and | ]] | |

| [vP Mary-Nom | [VP sushi-Acc | eat | ]] | Past] |

Under this analysis, both conjuncts are equally under the scope of the same tense morpheme, predicting only tense-matched interpretations.

Meanwhile, Chung (2005b) and others (Kang 2013; Lee and Tonhauser 2010) observe that conjuncts in bare ko-coordination may receive temporally independent interpretations. For instance, Chung observes that the following examples are acceptable:

| Sequential temporal order: [past-present] | ||||

| Motwu | (ecey) | yehayngttena-ko, | ||

| all | (yesterday) | trip-and | ||

| na-man | honca | (cikum) | cip-ul | cikhi-nta. |

| I-only | alone | (now) | home-Acc | stay-Pres |

| ‘All others left on a trip (yesterday), and I am alone staying home (now).’ | ||||

| Reverse temporal order: [present-past] | ||||

| Na-man | honca | (cikum) | cip-ul | cikhi-ko, |

| I-only | alone | (now) | home-Acc | keep-and |

| motwu | (ecey) | yehayngttena-ssta. | ||

| all | (yesterday) | trip-Past | ||

| ‘I am alone staying home (now), and all others left on a trip (yesterday).’ | ||||

| (Chung 2005b: 553) | ||||

Specifically, he proposes that a phonetically null tense morpheme exists in the first conjunct, as schematized in (11).

| Sequential temporal order: [past-present] | |||||

| [TP | [TP all | (yesterday) | trip-Ø T -and] | ||

| [TP I-only | alone | (now) | home-Acc | keep-Pres]] | |

| Reverse temporal order: [present-past] | |||||

| [TP | [TP I-only | alone | (now) | home-Acc | keep-Ø T -and] |

| [TP all | (yesterday) | trip-Past]] | |||

As shown in (11), although the first conjunct does not have an overt tense morpheme, its tense does not rely on the tense morpheme in the second conjunct, predicting either tense-matched or tense-mismatched interpretations.

In sum, there have been two different views on the status of bare ko-coordination with respect to temporal interpretations. One view is that only the tense-matched bare ko-coordination is acceptable. The other is that either tense-matched or tense-mismatched bare ko-coordination is acceptable.

Turning to a brief survey of cross-linguistic studies of gapping, it has been observed that gapping does not tolerate tense mismatches. For example, gapping in English, French, Romanian, Turkish, Hungarian, Polish, and Japanese does not allow tense mismatches (Abeillé et al. 2014; Bartos 2001; Citko 2018; Griffiths and Lipták 2014; İnce 2009; Kato 2003, etc.):

| English (Abeillé et al. 2014: 240) |

| *John arrived yesterday, and Bill tomorrow. |

| French (Abeillé et al. 2014: 241) | ||||||

| *Paul | est | arrivé | hier | et | Marie | demain. |

| Paul | has | arrived | yesterday | and | Marie | tomorrow |

| ‘Paul has arrived yesterday, and Marie (will arrive) tomorrow.’ | ||||||

| Romanian (Abeillé et al. 2014: 241) | ||||||

| *Ion | a | sosit | ieri, | iar | Maria | mâine. |

| Ion | has | arrived | yesterday | and | Maria | tomorrow |

| ‘Ion has arrived yesterday, and Maria (will arrive) tomorrow.’ | ||||||

| Turkish (İnce 2009: 156) | ||||||

| *Ahmet | Ayşe-yle | dün | konuştu, | Murat | Sena-yla | yarın. |

| Ahmet | Ayşe-to | yesterday | spoke | Murat | Sena-to | tomorrow |

| ‘Ahmet spoke to Ayşe yesterday, and Murat (will speak) to Sena tomorrow.’ | ||||||

| Hungarian (Griffiths and Lipták 2014: 214) | |||||||

| *Mari | tegnap | vásárolt | a | piacon, | én | pedig | holnap. |

| Mari | yesterday | shopped | the | market.on | I | PRT | tomorrow |

| ‘Mari was shopping at the market yesterday, and I (will shop at the market) tomorrow.’ | |||||||

| Polish (Citko 2018: 24) | |||||

| *Jan | wyjechał | wczoraj, | a | Adam | jutro. |

| Jan | left | yesterday | and | Adam | tomorrow |

| ‘Jan left yesterday, and Adam (will leave) tomorrow.’ | |||||

| Japanese (Kato 2003: 56) | |||

| *John-ga | kinou | hon-o, | soshite |

| John-Nom | yesterday | book-Acc | and |

| Mary-ga | asita | CD-o | kaimasu. |

| Mary-Nom | tomorrow | CD-Acc | buys |

| ‘John (bought) a book yesterday, and Mary will buy a CD tomorrow.’ | |||

In this light, we will settle a controversy regarding tense mismatches in Korean gapping. Among others, Chung (2005a) claims that Korean gapping does not allow tense mismatches:

| ??Mary-nun | ecey | yulamsen-ul, | John-un | onul | pihayngki-lul | tha-nta. |

| Mary-Top | yesterday | cruise-Acc | John-Top | today | plane-Acc | take-Pres |

| ‘Mary (took) a cruise yesterday, and John takes a plane today.’ | ||||||

In particular, Chung claims that (19) is unacceptable because the non-past tense morpheme n(ta) in the second conjunct is not compatible with the past temporal adverbial ecey ‘yesterday’ in the first conjunct.

Meanwhile, Ahn and Cho (2006) and others (Kim 2007; Kim and Cho 2012; Park 2009) claim that Korean gapping may allow tense mismatches, as shown in (20) and (21).

| ?Ape-nim-un | caknyeney, | ||

| father-Hon-Top | last.year | ||

| eme-nim-un | cikum | pyeng-ulo | nwuwe-kyesi-nta. |

| mother-Hon-Top | now | illness-due.to | lie.in.bed-beHon-Pres |

| ‘My fatherHon (was lying in bed due to an illness) last year, and my motherHon isHon lying in bed due to an illness now.’ | |||

| (Ahn and Cho 2006: 58) | |||

| Ape-nim-un | olhay | kyothongsako-lo, | |

| father-Hon-Top | this.year | traffic.accident-due.to | |

| eme-nim-un | caknyeney | pyeng-ulo | nwuwe-kyesi-essta. |

| mother-Hon-Top | last.year | illness-due.to | lie.in.bed-beHon-Past |

| ‘My fatherHon (is lying in bed) in a traffic accident this year, and my motherHon was Hon lying in bed due to an illness last year.’ | |||

| (Kim and Cho 2012: 394) | |||

In particular, Park (2009) claims that Korean gapping allows tense mismatches insofar as the antecedent conjunct observes the proximity condition between an antecedent verb and its clause-mate temporal adverbial as in (22).

| Na-nun | caknyeney, | John-un | olhayey | thongkyehak-ul | tut-nunta. |

| I-Top | last.year | John-Top | this.year | statistics-Acc | take-Pres |

| ‘I (took statistics) last year, and John is taking statistics this year.’ | |||||

| *Na-nun | caknyeney, | John-un | olhayey | thongkyehak-ul | tul-essta. |

| I-Top | last.year | John-Top | this.year | statistics-Acc | take-Past |

| ‘I (took statistics) last year, and John is taking statistics this year.’ | |||||

| (adapted from Park 2009: 194) | |||||

As for the grammaticality of (22a), Park argues that since the tense information of the temporal adverbial olhayey ‘this year’ and that of the tensed verb tut-nunta ‘takes’ in the full clause match, a tense-mismatch interpretation is available in Korean gapping. Park judged (22b) as ungrammatical under the interpretation of John is taking statistics this year due to the tense mismatch between the temporal adverbial olhayey ‘this year’ and the tensed verb tul-essta ‘took’.[4]

Besides the TENSE (i.e., matches or mismatches) predictor, another potential predictor to be considered affecting the acceptability of Korean coordination is temporal ORDER (i.e., sequential or reverse). To be specific, Chung (2005b) and Lee and Tonhauser (2010) argue that conjuncts in bare ko-coordination can be in any temporal order without affecting acceptability. Recall that the conjuncts of (10a) are in the sequential order (i.e., past–present), while those of (10b) are in the reverse order (i.e., present–past). On the other hand, Park and Kim (2021) claim that reversely tense-mismatched bare ko-coordination is significantly more acceptable than sequentially tense-mismatched bare ko-coordination.

Since linguistic theories are ideally built on robust empirical foundations, the data merit rigorous verification. In this regard, we will launch an empirical investigation of tense mismatches in the two types of tenseless coordination (i.e., bare ko-coordination and gapping) with respect to full clause coordination in Korean.

3 Experiment

3.1 Participants, materials, and design

Sixty-four self-reported native Korean speakers (age mean (SD): 22.7 (1.63)) were recruited. All were undergraduate students at Korea University. They participated in this experiment in exchange for course credit. In general, participants completed the online experiment within 15 min. Four participants were excluded because they did not pay attention during the task (by the procedure described below). Accordingly, only the responses from 60 participants (10 participants for each of the six lists) were included in the analysis.

The primary goal of this study was to test whether Korean bare ko-coordination and gapping allow tense mismatches between conjuncts. Given that the effect of tense mismatches on acceptability may not be unique to tenseless coordination, the tense-mismatch effect in bare ko-coordination and gapping was to be compared with that in full tensed coordination. This led us to construct an experiment with a 3 × 2 design, crossing SYNTAX (Full vs. Bare (ko-coordination) vs. Gapping) and TENSE (Match vs. MisMatch). Twenty-four lexically matched sets of the six conditions were constructed, as sampled below:

| [Full | Match] | |||

| John-i | caycaknyeney | mikwuk-ulo | ttena-ss-ko, |

| John-Nom | the.year.before.last | US-for | leave-Past-and |

| Mary-ka | caknyeney | mikwuk-ulo | ttena-ssta. |

| Mary-Nom | last.year | US-for | leave-Past |

| ‘John left for the US the year before last, and Mary left for the US last year.’ | |||

| [Full | MisMatch] | |||

| John-i | caycaknyeney | mikwuk-ulo | ttena-ss-ko, |

| John-Nom | the.year.before.last | US-for | leave-Past-and |

| Mary-ka | naynyeney | mikwuk-ulo | ttena-lketa. |

| Mary-Nom | next.year | US-for | leave-Fut |

| ‘John left for the US the year before last, and Mary will leave for the US next year.’ | |||

| [Bare | Match] | |||

| John-i | caycaknyeney | mikwuk-ulo | ttena-ko, |

| John-Nom | the.year.before.last | US-for | leave-and |

| Mary-ka | caknyeney | mikwuk-ulo | ttena-ssta. |

| Mary-Nom | last.year | US-for | leave-Past |

| ‘John left for the US the year before last, and Mary left for the US last year.’ | |||

| [Bare | MisMatch] | |||

| John-i | caycaknyeney | mikwuk-ulo | ttena-ko, |

| John-Nom | the.year.before.last | US-for | leave-and |

| Mary-ka | naynyeney | mikwuk-ulo | ttena-lketa. |

| Mary-Nom | next.year | US-for | leave-Fut |

| ‘John left for the US the year before last, and Mary will leave for the US next year.’ | |||

| [Gapping | Match] | |||||

| John-i | caycaknyeney, | Mary-ka | caknyeney | mikwuk-ulo | ttena-ssta. |

| John-Nom | the.year.before.last | Mary-Nom | last.year | US-for | leave-Past |

| ‘John (left for the US) the year before last, and Mary left for the US last year.’ | |||||

| [Gapping | MisMatch] | |||||

| John-i | caycaknyeney, | Mary-ka | naynyeney | mikwuk-ulo | |

| John-Nom | the.year.before.last | Mary-Nom | next.year | US-for | |

| ttena-lketa. | |||||

| leave-Fut | |||||

| ‘John (left for the US) the year before last, and Mary will leave for the US next year.’ | |||||

The [Full | Match] condition in (23a) contained full coordination clauses where the temporal relation between the coordinated clauses was matched. Meanwhile, the [Full | MisMatch] condition in (23b) contained full coordination clauses where the temporal relation between the coordinated clauses was mismatched.

The two clauses of the [Bare | Match] condition in (23c) were coordinated via the so-called bare ko ‘and’, with no overt tense-marking of the first conjunct verb. The temporal adverbs in both clauses were matched in tense. The minimal difference of the [Bare | MisMatch] condition in (23d) from the [Bare | Match] condition in (23c) was that the temporal adverbs in (23d) were mismatched in tense.

The [Gapping | Match] condition in (23e) illustrated gapping in which the temporal relation between the coordinated clauses was matched. On the other hand, the [Gapping | MisMatch] condition in (23f) contained Korean gapping where the temporal relation between the coordinated clauses was mismatched.

There have been arguments that ellipsis tends to favor parallelism (Carlson 2002; Frazier and Clifton 2001; Kehler 2000, etc.). Kim et al. (2020), for instance, contend that the parallelism effect can be attributed to the parser’s general inclination to maintain maximum parallel structure within each conjunct in a coordination structure. In this tradition, we predicted that the [Match] condition would be more acceptable than the [MisMatch] condition in the two types of tenseless coordination, [Bare] and [Gapping]. Then, the effect of tense mismatches would be examined by measuring the amount of degradation in the [MisMatch] condition relative to the [Match] condition. If the degradation in the [Bare] and [Gapping] conditions is significantly greater than that in the [Full] condition, which will be verified by a significant two-way interaction SYNTAX × TENSE, it will indicate that the tenseless coordination, either [Bare] or [Gapping] or both, does not allow tense mismatches between conjuncts.

Our secondary goal was to examine the validity of Park and Kim’s (2021) experimental finding, according to which temporal order, whether it is sequential or reverse, affects the acceptability of bare ko-coordination but not that of gapping. For this, we divided the 24 sets of experimental items into two parts: the first 12 sets contained sequentially ordered experimental conditions in that the timing of the event depicted in the first clause precedes that depicted in the second clause; temporal order was reversed in the latter 12 sets. We planned to examine this effect by, after addressing our primary question, introducing another potential predictor ORDER (Sequential vs. Reverse) in the analyses so that we could compare the TENSE effect of the first 12 [Sequential] sets with that of the latter 12 [Reverse] sets. For each [Bare] and [Gapping], a significant two-way interaction TENSE × ORDER might indicate that the temporal order affected the amount of the tense-mismatch penalty in the tenseless coordination in Korean. The full list of test items is available online.[5]

The experimental items were counterbalanced across six lists using a Latin square design so that the items were equally distributed into each list. The items appeared in one of six pseudorandomized orders such that no consecutive items were of the same type or condition. The 72 filler items were of comparable length but with varying acceptability based on the results from our previous tests. We controlled the number of good, mid, and bad fillers in order to help create a list of stimuli that are roughly balanced in terms of acceptability, so that participants will use the full range of the response scale provided.

3.2 Procedure

We programmed the experiment with a web-based experiment platform PCIbex (Zehr and Schwarz 2018). Sentences were presented one at a time on a computer screen and participants were asked to make acceptability judgments on the basis of a 1–7 Likert scale (1 corresponding to a completely unacceptable sentence and 7 to a fully acceptable one).

In addition to test items, there were 16 “gold standard” filler items. These items comprised eight good and eight bad filler items, which demonstrated the highest or lowest acceptability most clearly in previous tests conducted on approximately 200 participants prior to the experiment. We obtained the expected value of these fillers (i.e., 1 for the bad ones and 7 for the good ones) from the results of these previous tests. For each gold standard item, we calculated the difference between each participant’s response and its expected value (i.e., 1 or 7). In order to compare the size of the differences that were either positive or negative numbers, we squared each of the differences and summed the squared differences for each participant. This gave us the sum-of-the-squared-differences value of each participant. We excluded any participants whose sum-of-the-squared-differences value was greater than two standard deviations away from the mean, suggesting that they were not paying attention during the task (cf. Sprouse et al. 2022).

3.3 Data analysis

Prior to statistical analysis, the raw judgment ratings, including both experimental and filler items, were converted to z-scores in order to eliminate certain kinds of scale biases between participants (Schütze and Sprouse 2013). This procedure corrects the potential that individual participants treat the scale differently (e.g., using only a subset of the available ratings) because it standardizes all participants’ ratings to the same scale. We analyzed the data with linear mixed-effects (regression) models estimated with the lme4 package (Bates et al. 2015) in the R software environment (R Core Team 2020). Linear mixed-effects models allow the simultaneous inclusion of random participant and random item variables (Baayen et al. 2008). In each mixed-effects model, we included the maximally convergent random effects structure (Barr et al. 2013). To estimate p-values for the fixed and random effects, we used Satterthwaite’s approximation (Kuznetsova et al. 2017) in the analysis. For pairwise comparisons, we ran a post-hoc test with Bonferroni correction using the emmeans() function (Lenth et al. 2018).

3.4 Results

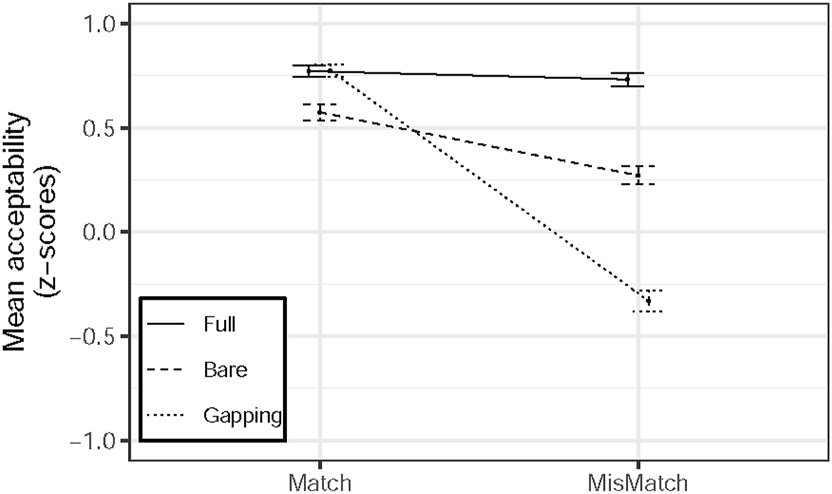

The responses of 240 tokens for each of the six conditions (N = 1,440 in total) were analyzed. Figure 1 presents the mean of the z-scored ratings for the six experimental conditions. The zero represents the overall mean acceptability rating; positive z-scores indicate that conditions are rated towards being acceptable, while negative z-scores indicate that conditions are rated towards being unacceptable. The SYNTAX effect is represented by a vertical separation between the lines, and the TENSE effect is represented by the downward slope of the lines:

Mean acceptability of 24 sets of experimental conditions (error bars indicate standard errors).

As for our main interest, we ran a 2 × 2 mixed-effects model for each of the two types of tenseless coordination, [Bare] and [Gapping]. First, to test whether bare ko-coordination allows tense mismatches, we ran a 2 × 2 mixed-effects model with SYNTAX [Full vs. Bare] and TENSE as fixed effects and the maximally convergent random effects structure (i.e., by-participant and by-item intercepts and a by-participant slope for each of the two fixed factors). The results of the model are summarized in Table 1.

Fixed effects (SYNTAX × TENSE) summary for bare ko-coordination.

| Estimate | SE | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 0.775 | 0.048 | 12.045 | *** |

| SYNTAX [Full vs. Bare] | −0.200 | 0.057 | 4.105 | *** |

| TENSE | −0.012 | 0.063 | −4.883 | 0.769 |

| SYNTAX:TENSE | −0.295 | 0.086 | −9.560 | *** |

-

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

There was a significant effect of SYNTAX [Full vs. Bare] but no significant effect of TENSE. However, there was an interaction, which revealed that the difference in acceptability between the tense-match and tense-mismatch cases in the [Bare] condition was greater than that in the [Full] condition. Post-hoc tests confirmed that the tense-mismatched [Bare] condition suffered a separate penalty: [Full | Match] versus [Full | MisMatch] (β = 0.012, SE = 0.040, t = 0.295, p = 1.000) and [Bare | Match] versus [Bare | MisMatch] (β = 0.306, SE = 0.063, t = 4.858, p < 0.001). This suggests that tense mismatches inflict a degradation in bare ko-coordination.

Second, to test if gapping allows tense mismatches, we fit a model for SYNTAX [Full vs. Gapping] crossed with TENSE. The results of the model are summarized in Table 2.

Fixed effects (SYNTAX × TENSE) summary for gapping.

| Estimate | SE | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 0.775 | 0.032 | 24.526 | *** |

| SYNTAX [Full vs. Gapping] | 0.034 | 0.038 | 0.905 | 0.369 |

| TENSE | −0.012 | 0.038 | −0.309 | 0.758 |

| SYNTAX:TENSE | −1.121 | 0.091 | −12.281 | *** |

There was neither a significant effect of SYNTAX [Full vs. Gapping] nor a significant effect of TENSE. However, there was an interaction, which revealed that the difference in acceptability between the tense-match and tense-mismatch cases in the [Gapping] condition was greater than that in the [Full] condition. Post-hoc tests confirmed that the tense-mismatched [Gapping] condition suffered a separate penalty: [Full | Match] versus [Full | MisMatch] (β = 0.012, SE = 0.038, t = 0.309, p = 1.000) and [Gapping | Match] versus [Gapping | MisMatch] (β = 1.133, SE = 0.084, t = 13.435, p < 0.001). This result indicates that tense mismatches degrade gapping.

Further, a visual inspection of the plot in Figure 1 suggests that the penalty due to tense mismatches was greater in gapping relative to bare ko-coordination. We thus ran another 2 × 2 mixed-effects model with SYNTAX [Bare vs. Gapping] and TENSE. The results of the model are summarized in Table 3.

Fixed effects (SYNTAX × TENSE) summary for bare ko-coordination versus gapping.

| Estimate | SE | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 0.575 | 0.048 | 12.045 | *** |

| SYNTAX [Bare vs. Gapping] | 0.234 | 0.057 | 4.105 | *** |

| TENSE | −0.306 | 0.063 | −4.883 | *** |

| SYNTAX:TENSE | −0.826 | 0.086 | −9.560 | *** |

There were significant effects of SYNTAX [Bare vs. Gapping] and TENSE.[6] The interaction was also significant, indicating that the difference in acceptability between the tense-match and tense-mismatch cases in the [Gapping] condition was greater than that in the [Bare] condition. Post-hoc tests confirmed that the tense-mismatched [Gapping] condition suffered a separate penalty: [Bare | Match] versus [Bare | MisMatch] (β = 0.306, SE = 0.063, t = 4.883, p < 0.001) and [Gapping | Match] versus [Gapping | MisMatch] (β = 1.133, SE = 0.084, t = 13.513, p < 0.001).

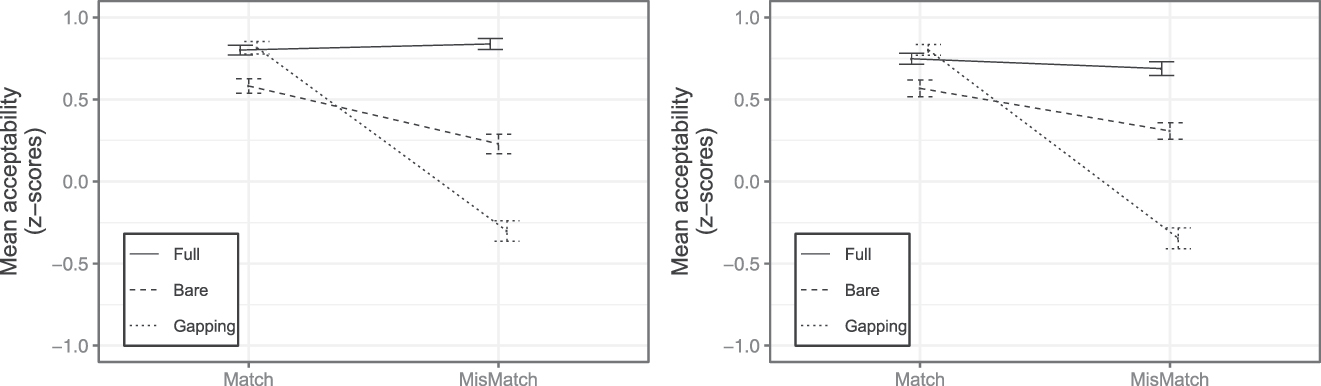

Another goal of this study was to examine whether temporal order affected the amount of penalty on acceptability due to tense mismatches in bare ko-coordination and gapping. As planned, we added ORDER (Sequential vs. Reverse) as another predictor in the analyses. Figure 2 presents the mean acceptability of the six experimental conditions split by ORDER: the left panel for the results of the [Sequential] ones (i.e., the first 12 sets) and the right panel for that of the [Reverse] ones (i.e., the latter 12 sets).

Mean acceptability of 12 sequentially ordered sets (left panel) and 12 reversely ordered sets (right panel) of experimental conditions.

Overall, the two plots of Figure 2 show very similar patterns. A visual inspection of the plots suggests that ORDER did not make much influence on the TENSE effect (i.e., the penalty due to tense mismatches) in both the [Bare] and [Gapping] conditions. While there seems to be no TENSE effect in the [Full] condition in general (i.e., their mean acceptability z-scores seem to overlap), both the [Bare] and [Gapping] conditions seem to show a clear difference between [Match] versus [MisMatch] in both the [Sequential] and [Reverse] conditions.

In order to examine the role of temporal ORDER through statistical modeling, we ran two additional sets of a 2 × 2 mixed-effects model for the effect of ORDER on the tense-mismatch penalty in the [Bare] and [Gapping] conditions. Table 4 presents the summary of the 2 × 2 mixed-effects model (TENSE × ORDER) within the [Bare] condition, and Table 5 summarizes the 2 × 2 mixed-effects model (TENSE × ORDER) within the [Gapping] condition.

Fixed effects (TENSE × ORDER) summary for bare ko-coordination.

| Estimate | SE | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 0.582 | 0.056 | 10.349 | *** |

| TENSE | −0.353 | 0.081 | −4.349 | ** |

| ORDER | −0.015 | 0.058 | −0.250 | 0.803 |

| TENSE:ORDER | 0.093 | 0.090 | 1.032 | 0.305 |

Fixed effects (TENSE × ORDER) summary for gapping.

| Estimate | SE | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 0.815 | 0.045 | 18.206 | *** |

| TENSE | −1.117 | 0.094 | −11.908 | *** |

| ORDER | −0.013 | 0.059 | −0.222 | 0.825 |

| TENSE:ORDER | −0.032 | 0.083 | −0.383 | 0.704 |

In both bare ko-coordination and gapping, the effect of TENSE was significant, but the effect of ORDER was not. Also, the effect of the two-way interaction TENSE × ORDER did not reach significance. Together, the results confirmed that temporal order did not affect the amount of penalty due to tense mismatches in both bare ko-coordination and gapping.

4 General discussion and syntactic analysis

There were two main findings from the experiments reported above. First, the acceptability of both bare ko-coordination and gapping was degraded by tense mismatches but that of full coordination was not. However, the tense-mismatch penalty was different between bare ko-coordination and gapping. As given in Table 3, tense mismatches induced a significantly greater amount of degradation in gapping than in bare ko-coordination. As a result, tense mismatches made bare ko-coordination moderately acceptable (mean: 0.268), but gapping with tense mismatches was quite unacceptable (mean: −0.324). This suggests that tense mismatches in gapping inflict a separate penalty relative to those in bare ko-coordination. This finding argues against the claim that gapping permits tense mismatches (Ahn and Cho 2006; Kim 2007; Kim and Cho 2012; Park 2009), defending the claim that gapping requires tense matches (Choi 2019; Kim 2019; Park and Kim 2021). Furthermore, the finding that tense-mismatched bare ko-coordination was moderately acceptable undermines the view that only tense-matched bare ko-coordination is allowed (Kang 1988; Park 1994; Yoon 1996; Yoon 1997), confirming the view that either tense-matched or tense-mismatched one is allowed (Chung 2005b; Kang 2013; Lee and Tonhauser 2010).

Second, temporal order, whether it was sequential or reverse, did not significantly affect the acceptability of bare ko-coordination and gapping. This finding defends the claim that bare ko-coordination can be presented in any temporal order without affecting acceptability (Chung 2005b; Lee and Tonhauser 2010), casting doubt on Park and Kim’s (2021) finding that reversely tense-mismatched bare ko-coordination is significantly more acceptable than sequentially tense-mismatched bare ko-coordination.

As pointed out by a reviewer, one might wonder why our experimental finding is different from Park and Kim’s (2021) with respect to bare ko-coordination. We want to point out that Park and Kim’s experiment had one important issue that differentiates it from the experiment reported in this paper. While the experimental design was similar, Park and Kim split their 2 × 2 × 3 design (TENSE × ORDER × SYNTAX in our terms) into two sub-experiments, treating TENSE as a between-subject factor. In other words, they ran two instances of a 2 × 3 (ORDER × SYNTAX) experiment with two different groups of participants: one group saw only the tense-matched conditions and the other group saw only the tense-mismatched conditions, in addition to fillers. In their experimental setting, the distribution of acceptability ratings could be very different between the two groups: while the responses from the group with only tense-matched conditions would be predominantly of high acceptability, the responses from the group with only tense-mismatched conditions would be predominantly of low acceptability, except for the full-tensed-coordination conditions. This issue has been referred to as an equalization strategy in response (cf. Sprouse 2009): participants tend to balance their responses throughout an entire experiment between, for example, high ratings and low ratings. As attested by experimental findings from both Park and Kim and the current study, tense-matched conditions turned out to be significantly more acceptable than tense-mismatched conditions with respect to bare-ko coordination and gapping. It was thus very likely that the overall acceptability ratings of experimental items from the two participant groups were influenced by the different proportions of high acceptable items and low acceptable items, respectively. In particular, the high acceptability of the [Reverse | Bare | MisMatch] condition (raw-score mean: 5.41) in Park and Kim’s results, which was even slightly higher than the [Reverse | Bare | Match] condition (raw-score mean: 5.35), could have been due to the participants’ equalization strategy in response. Since the participants in this group needed to give a low acceptability rating for the four conditions (i.e., the [MisMatch] conditions in [Gapping | Sequential], [Gapping | Reverse], [Bare | Sequential], and [Bare | Reverse]) out of the six conditions, which is significantly more frequent than the conditions of the other group, there is a high chance that they might have made a conscious effort to achieve balance among all of their ratings, and it might have distorted the ratings on the [Reverse | Bare | MisMatch] condition towards an unfairly higher acceptability.[7]

With the above discussion in mind, we propose that the experimental stimuli in (23) are derived in the following way:

| [Full | Match] | ||||||

| [TP | [TP John-Nom | the year before last | US-for | leave-Past-and | ] | |

| [TP Mary-Nom | last year | US-for | leave-Past | ] | ] | |

| [Full | MisMatch] | ||||||

| [TP | [TP John-Nom | the year before last | US-for | leave-Past-and | ] | |

| [TP Mary-Nom | next year | US-for | leave-Fut | ] | ] | |

| [Bare | Match] | ||||||

| [TP | [TP John-Nom | the year before last | US-for | leave-Ø T -and | ] | |

| [TP Mary-Nom | last year | US-for | leave-Past | ] | ] | |

| [Bare | MisMatch] | ||||||

| [TP | [TP John-Nom | the year before last | US-for | leave-Ø T -and | ] | |

| [TP Mary-Nom | next year | US-for | leave-Fut | ] | ] | |

| [Gapping | Match] | |||||||||

| [TP | [vP John-Nom | the year before last | [VP | Ø | ] | ] | |||

| [vP Mary-Nom | last year | [VP | US-for | leave | ] | ] | Past | ] | |

| [Gapping | MisMatch] | |||||||||

| [TP | [vP John-Nom | the year before last | [VP | Ø | ] | ] | |||

| [vP Mary-Nom | next year | [VP | US-for | leave | ] | ] | Fut | ] | |

The [Full | Match] condition in (24a) and the [Full | MisMatch] condition in (24b), both of which involve coordination of full clauses, are acceptable because they have an independent tense projection, i.e., TP, in each coordinated clause. Since there is no difference in acceptability between the two conditions, it can be concluded that tense mismatches in full coordination do not affect acceptability, as expected.

Considering the acceptability of [Bare | Match] in (24c) and [Bare | MisMatch] in (24d), we propose that the conjunct size in bare ko-coordination is TP, similar to full coordination. One minimal difference is that the first conjunct in (24c) and (24d) may have a null tense morpheme in T (Chung 2005b), which is independent from the overt tense marker in the second conjunct. This null tense is interpreted, via the congruence with a temporal cue (i.e., the year before last), as [Past] in both (24c) and (24d). This analysis thus supports the claim made by Chung (2005b), Kang (2013), and Lee and Tonhauser (2010). Since bare ko-coordination has missing tense information that the parser needs to recover for a successful interpretation, the cost of such a process will be reflected in the acceptability.[8] Regarding the slightly degraded acceptability of [Bare | Match] compared with the acceptability of [Full | Match], we suggest that identifying the null tense information via a temporal adverbial causes a processing difficulty.[9] The tense-mismatched situation will present an additional challenge to the parser. In this regard, we thus suggest that the tense-mismatch penalty further lowers the acceptability of [Bare | MisMatch] compared with that of [Bare | Match].[10]

However, tense mismatches significantly decrease the acceptability ratings of [Gapping | MisMatch] in (24f). The low acceptability of [Gapping | MisMatch] suggests that the missing tense of the gapped clause in gapping, which is coordinated at the vP level, is determined via a structural notion like c-command by the higher overt tense-marker of the antecedent clause, thus defending the claim made by Chung (2005a) and others (Choi 2019; Kim 2019; Park and Kim 2021).

Before concluding this section, we wish to answer the question, raised by a reviewer, of why tense-matched gapping (= [Gapping | Match]) was more acceptable than tense-matched bare ko-coordination (= [Bare | Match]). Although there was a statistically significant difference of acceptability ratings between [Gapping | Match] and [Bare | Match] (β = −0.234, SE = 0.054, t = −4.301, p < 0.01), it seems that the difference should be addressed from the perspective of processing, given that both were judged as well-formed (mean: [Gapping | Match] 0.809 vs. [Bare | Match] 0.575). To be specific, we suggest that [Bare | Match] places an extra processing challenge relative to [Gapping | Match], which would explain the difference in acceptability. In the case of [Gapping | Match], the tense information of two coordinated vPs was simultaneously decided by the tense marker in T of the antecedent clause, as schematized in (24e) and (24f). Thus, there was less leeway for the parser to intervene. Meanwhile, in the case of [Bare | Match], the parser needs to interpret the null tense morpheme in the first conjunct, as illustrated in (24c) and (24d), with other clause-internal temporal cues (i.e., the temporal adverbial). This would cause a processing difficulty.

5 Conclusions

In this experimental study, we showed that tense mismatches greatly lower the acceptability of bare ko-coordination and gapping, but not that of full coordination, regardless of temporal order. We thus defended the claim that tense-mismatched gapping is not acceptable in Korean (Choi 2019; Chung 2005a; Kim 2019), contra Ahn and Cho (2006), Kim and Cho (2012), and Park (2009). We also showed that the influence of temporal order on the acceptability of bare ko-coordination is not significant, contra Park and Kim (2021). In addition, unlike the previous empirical studies such as Park and Kim (2021), we provided a theoretical analysis of tense mismatches of the constructions at issue: full coordination, bare ko-coordination, and gapping. We accounted for the gradable tense-mismatched phenomena of the three constructions via the difference of conjunct sizes: For full coordination and bare ko-coordination, the conjunct size is TP since each conjunct has an independent (overt or covert) tense T. To be more specific, for full coordination, there are two independent overt Ts. For bare ko-coordination, there is a null T in the first conjunct and an independent overt T in the second conjunct. For gapping, the conjunct size is vP; there is only one T, which c-commands both conjuncts but is located only in the second conjunct. In sum, the tense-mismatch effects in three types of coordinate constructions are derived from the conjunct size (i.e., height). While full coordination and bare ko-coordination allow the tense mismatch between conjuncts, gapping does not.

Acknowledgments

We express our gratitude to the two anonymous reviewers of the journal and all the participants at the 2022 Seminar at Korea University for their valuable feedback and comments on the content presented in this work. Any remaining errors are solely our responsibility.

References

Abeillé, Anne, Gabriela Bîlbîie & François Mouret. 2014. A Romance perspective on gapping constructions. In Hans C. Boas & Francisco Gonzálvez-García (eds.), Romance perspectives on construction grammar, 227–265. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.10.1075/cal.15.07abeSearch in Google Scholar

Ahn, Hee-Don & Yongjoon Cho. 2006. A dual analysis of verb-less coordination in Korean. Language Research 42(1). 47–68.Search in Google Scholar

An, Duk-Ho. 2007. Syntax at the PF interface: Prosodic mapping, linear order, and deletion. Storrs, CT: University of Connecticut dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

Baayen, Rolf H., Douglas J. Davidson & Douglas M. Bates. 2008. Mixed-effects modeling with crossed random effects for subjects and items. Journal of Memory & Language 59(4). 390–412. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jml.2007.12.005.Search in Google Scholar

Barr, Dale J., Roger Levy, Christoph Scheepers & Harry J. Tily. 2013. Random effects structure for confirmatory hypothesis testing: Keep it maximal. Journal of Memory & Language 68(3). 255–278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jml.2012.11.001.Search in Google Scholar

Bartos, Huba. 2001. Sound-form non-insertion and the direction of ellipsis. Acta Linguistica Hungarica 48(1). 3–24.Search in Google Scholar

Bates, Douglas, Martin Mächler, Benjamin M. Bolker & Steven C. Walker. 2015. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software 67(1). 1–48. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v067.i01.Search in Google Scholar

Bošković, Željko. 2004. Two notes on right node raising. University of Connecticut Working Papers in Linguistics 12. 13–24.Search in Google Scholar

Carlson, Katy. 2002. Parallelism and prosody in the processing of ellipsis sentences. New York, NY: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Cho, Sae-Youn. 2006. Defaults, tense, and non-tensed verbal coordination. The Linguistic Association of Korea Journal 14(3). 195–214.Search in Google Scholar

Choi, YoungSik. 2019. Gapping in V+ko construction in Korean as dependent ellipsis. The Linguistic Association of Korea Journal 27(3). 75–97. https://doi.org/10.24303/lakdoi.2019.27.3.75.Search in Google Scholar

Chung, Daeho. 2004. A multiple dominance analysis of right node sharing constructions. Language Research 40(4). 791–811.Search in Google Scholar

Chung, Daeho. 2005a. Interpretation of verbal affixes in V-ed and V-less coordination and some theoretical implications. Presented at the 8th Korea Generative Grammar Conference.Search in Google Scholar

Chung, Daeho. 2005b. What does bare -ko coordination say about post-verbal morphology in Korean? Lingua 115(4). 549–568. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lingua.2003.09.015.Search in Google Scholar

Citko, Barbara. 2018. On the relationship between forward and backward gapping. Syntax 21(1). 1–36. https://doi.org/10.1111/synt.12150.Search in Google Scholar

Frazier, Lyn & Charles CliftonJr. 2001. Parsing coordinates and ellipsis: Copy α. Syntax 4(1). 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9612.00034.Search in Google Scholar

Griffiths, James & Anikó Lipták. 2014. Contrast and island sensitivity in clausal ellipsis. Syntax 17(3). 189–234. https://doi.org/10.1111/synt.12018.Search in Google Scholar

Ha, Seungwan. 2008. Ellipsis, right node raising, and across-the-board constructions. Boston, MA: Boston University dissertation.10.3765/bls.v34i1.3562Search in Google Scholar

Hirata, Ichiro. 2006. Predicate coordination and clause structure in Japanese. The Linguistic Review 23(1). 69–96. https://doi.org/10.1515/tlr.2006.003.Search in Google Scholar

İnce, Atakan. 2009. Dimensions of ellipsis: Investigations in Turkish. College Park, MD: University of Maryland dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

Kang, Beom-Mo. 1988. Functional inheritance, anaphora and semantic interpretation in a generalized categorial grammar. Providence, RI: Brown University dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

Kang, Jungmin. 2013. Temporal interpretation in the absence of TP. Language & Information Society 20. 161–202. https://doi.org/10.29211/soli.2013.20.005.Search in Google Scholar

Kato, Kumiko. 2003. On Japanese gapping in minimalist syntax. Working Papers of the Linguistics Circle 17. 55–64.Search in Google Scholar

Kayne, Richard. 1994. The antisymmetry of syntax. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.Search in Google Scholar

Kehler, Andrew. 2000. Coherence and the resolution of ellipsis. Linguistics and Philosophy 23(6). 533–575. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1005677819813.10.1023/A:1005677819813Search in Google Scholar

Kim, Jeong-Seok. 2006. Against a multiple dominance analysis of right node raising constructions in Korean and Japanese. Studies in Modern Grammar 46. 123–147.Search in Google Scholar

Kim, Jeong-Seok. 2019. Sayngnyakkwa chocem: Swuyongseng phantanul cwungsimulo [Ellipsis and focus: With special reference to acceptability judgment]. Seoul: Hankook Publishing.Search in Google Scholar

Kim, Jong-Bok & Jaehyung Yang. 2011. Symmetric and asymmetric properties in Korean verbal coordination: A computational implementation. Language & Information 15(2). 1–21. https://doi.org/10.29403/li.15.2.1.Search in Google Scholar

Kim, Nayoun, Katy Carlson, Mike Dickey & Masaya Yoshida. 2020. Processing gapping: Parallelism and grammatical constraints. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology 73(5). 781–798. https://doi.org/10.1177/1747021820903461.Search in Google Scholar

Kim, Yae-Jee & Sae-Youn Cho. 2012. Tense and honorific interpretations in Korean gapping construction: A constraint- and construction-based approach. In Stefan Muller (ed.), Proceedings of the 19th International Conference on Head-Driven Phrase Structure Grammar, 388–408.10.21248/hpsg.2012.22Search in Google Scholar

Kim, Yong-Ha. 2007. Hankwukeuy mwutongsa cepsokmwun [Korean verb-less coordination]. In Changguk Yim (ed.), Saynglyakhyensangyenkwu: Pemenecek kwanchal [Studies on elliptic phenomena: A crosslinguistic observation], 84–122. Seoul: Hankook Publishing.Search in Google Scholar

Kuznetsova, Alexandra, Per B. Brockhoff & Rune H. B. Christensen. 2017. LmerTest package: Tests in linear mixed effects models. Journal of Statistical Software 82(13). 1–26. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v082.i13.Search in Google Scholar

Lasnik, Howard. 1999. Minimalist analysis. Oxford: Blackwell.Search in Google Scholar

Lee, Jungmee & Judith Tonhauser. 2010. Temporal interpretation without tense: Korean and Japanese coordination constructions. Journal of Semantics 27(3). 307–341. https://doi.org/10.1093/jos/ffq005.Search in Google Scholar

Lenth, Russell, Henrik Singmann, Jonathon Love, Paul Buerkner & Maxime Herve. 2018. Emmeans: Estimated marginal means, aka least-squares means. R package version 1.4.6.Search in Google Scholar

Mukai, Emi. 2003. On verbless conjunction in Japanese. In Proceedings of the 33th North East Linguistic Society, 205–224.Search in Google Scholar

Park, Myung-Kwan. 1994. A morpho-syntactic study of Korean verbal inflection. Storrs, CT: University of Connecticut dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

Park, Myung-Kwan. 2009. Right node raising as conjunction reduction fed by linearization. Language Research 45(2). 179–202.Search in Google Scholar

Park, Sang-Hee & Jungsoo Kim. 2021. Temporal mismatches and the acceptability of tenseless coordinate constructions in Korean. Linguistic Research 38(2). 301–327.Search in Google Scholar

Postal, Paul M. 1974. On raising. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.Search in Google Scholar

R Core Team. 2020. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Available at: https://www.r-project.org.Search in Google Scholar

Ross, John R. 1970. Gapping and the order of constituents. In Manfred Bierwisch & Kurt Heidolph (eds.), Progress in linguistics, 249–259. The Hague: Mouton.Search in Google Scholar

Sag, Ivan. 1976. Deletion and logical form. Cambridge, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

Saito, Mamoru. 1987. Three notes on syntactic movement in Japanese. In Takashi Imai & Mamoru Saito (eds.), Issues in Japanese linguistics, 301–350. Dordrect: Foris.10.1515/9783112420423-011Search in Google Scholar

Schütze, Carson T. & Jon Sprouse. 2013. Judgment data. In Robert J. Podesva & Devyani Sharma (eds.), Research methods in linguistics, 27–50. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9781139013734.004Search in Google Scholar

Sohn, Sung-Ock. 1995. Tense and aspect in Korean. Honolulu, HI: University of Hawaii Press.Search in Google Scholar

Sprouse, Jon. 2009. Revisiting satiation: Evidence for an equalization response strategy. Journal of Linguistics 40(2). 329–341. https://doi.org/10.1162/ling.2009.40.2.329.Search in Google Scholar

Sprouse, Jon, Troy Messick & Jonathan David Bobaljik. 2022. Gender asymmetries in ellipsis: An experimental comparison of markedness and frequency accounts in English. Journal of Linguistics 58(2). 345–379. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0022226721000323.Search in Google Scholar

Tomioka, Satoshi. 1993. Verb movement and tense specification in Japanese. In Proceedings of the 11th West Coast Conference on Formal Linguistics, 482–494.Search in Google Scholar

Wexler, Ken & Peter Culicover. 1980. Formal principles of language acquisition. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.Search in Google Scholar

Yoon, James Hye-Suk. 1997. Coordination (a)symmetries. In Susumu Kuno, John Whitman, Young-Se Kang, Ik-Hwan Lee, Joan Maling & Young-Joo Kim (eds.), Harvard studies in Korean linguistics, vol. 7, 3–32. Seoul: Hanshin Publishing.Search in Google Scholar

Yoon, Jeong-Me. 1996. Verbal coordination in Korean and English and the checking approach to verbal morphology. Korean Journal of Linguistics 21(4). 1105–1135.Search in Google Scholar

Zehr, Jérémy & Florian Schwarz. 2018. PennController for internet based experiments (IBEX). Available at: https://osf.io/md832/.Search in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research Article

- Investigating the effects of late sign language acquisition on referent introduction: a follow-up study

- Review Article

- A survey of Polish ASR speech datasets

- Research Articles

- Tense mismatches in Korean gapping and bare ko-coordination: an experimental study

- “Mapping and projecting otherness in media discourse of the Russia–Ukraine war”

- “Gap” matters: reflections on the notion of “gap” of relative clauses

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research Article

- Investigating the effects of late sign language acquisition on referent introduction: a follow-up study

- Review Article

- A survey of Polish ASR speech datasets

- Research Articles

- Tense mismatches in Korean gapping and bare ko-coordination: an experimental study

- “Mapping and projecting otherness in media discourse of the Russia–Ukraine war”

- “Gap” matters: reflections on the notion of “gap” of relative clauses