Assessing data completeness in the international society for the study of pleura and peritoneum (ISSPP) PIPAC database: a multicenter evaluation from 2020–2024

-

Magnus Skov Jørgensen

, Pernille Shjødt Hansen

, Claus Wilki Fristrup

, Martin Hübner

, Peter Hewett

, Özgül Düzgün

, Francesco Casella

, Andrea Di Giorgio

Abstract

Objectives

In 2020, Pressurized Intraperitoneal Aerosol Chemotherapy (PIPAC) reached stage 2b of the IDEAL framework and a prospective international PIPAC database was launched in June 2020 by the International Society for the Study of the Pleura and Peritoneum (ISSPP). The ISSPP PIPAC database consists of six key elements, which are reported in an annual report. The ISSPP Registry Group decided to investigate data completeness within the ISSPP PIPAC Database.

Methods

Retrospective analysis of data completeness in the six key elements was performed between October 1st and 14th, 2024. This was complemented by an in-depth analysis of missing data in Response Evaluation, Complications, and Follow-up.

Results

Thirty centers, 950 patients, and 2777 PIPAC procedures were registered in the ISSPP database by October 2024. Sixteen of the 30 centers had included patients. Incomplete data were observed in four of the six key elements. Most centers (7/16) had incomplete data in Complications, followed by Response evaluation (5/16), and Follow-up (2/16). In depth analysis showed that, e.g., for complications, the date and type of the complication was registered in 88 and 89 %, respectively. Incomplete data in Response evaluation occurred mainly in the small group of patients evaluated by nonperitoneal regression grading score (non-PRGS, n=316), where no scoring was provided in 211 patients (72 %). Follow-up data, such as date of death or reasons for stopping PIPAC, were provided for 86 and 85 % of patients.

Conclusions

Overall data completeness of the ISSPP PIPAC Database was considered satisfactory at the present state, and the ISSPP Registry Group has launched several initiatives to further improve data completeness and quality, to provide solid data sets for future annual reports and other research.

Introduction

Peritoneal metastasis (PM) is a common condition in patients with gastrointestinal and gynecological cancer. Systemic chemotherapy tends to have a relatively short effect in these patients, reflected in their poor prognosis [1], 2]. A decade ago, Pressurized Intraperitoneal Aerosol Chemotherapy (PIPAC) was introduced to overcome the limitations of systemic chemotherapy during palliative treatment in patients with PM [3]. PIPAC reached stage 2b of the IDEAL framework in 2020, and a prospective international PIPAC database was launched by the International Society for the Study of the Pleura and Peritoneum (ISSPP) and is hosted by Odense Patient data Explorative Network (OPEN) [4], 5]. The ISSPP PIPAC database (PIPAC database) has been implemented using REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) [6], a web-based software solution for easy online access, and consists of six key elements: Patient, Consent, Treatment, Complications, Response evaluation, and Follow-up. The results from the PIPAC database have been described in two previously published annual PIPAC reports [4], 7], and the PIPAC database is considered essential for monitoring indications, complications, and potential clinical effect, while awaiting data from randomized controlled trials.

However, most international databases face challenges during initial construction (e.g., mode of access, implementation of an easy-to-use interface, costs) and continued operation (e.g., maintenance and monitoring costs), as well as data quality and validity (e.g., inaccurate, incomplete, or missing data). The latter may have a negative influence on the final data analyses and conclusions [8], 9]. In 2023, the second annual PIPAC database report showed missing and incomplete data on specific topics like date of death, reasons for stopping PIPAC, and nonperitoneal regression grading score (non-PRGS) response evaluation [7].

As continuous monitoring of missing and incomplete data is an important part of qualifying and improving the database reports, the ISSPP Registry Group decided to evaluate this before publication of the third annual PIPAC database report. Thus, the primary study aim was to assess data completeness within the ISSPP PIPAC database. Secondary objectives included identifying patterns of missing data and proposing improved strategies for data entry, monitoring, and reporting.

Methods

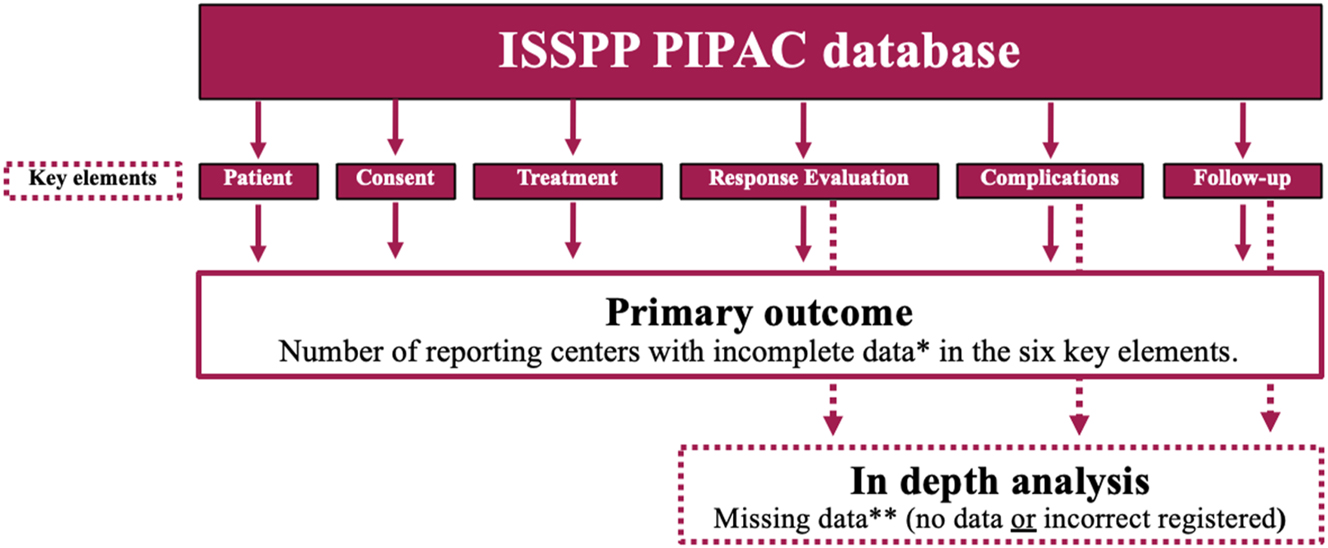

A retrospective analysis of data completeness within the ISSPP PIPAC database was performed on data exported on 14th of October 2024, which included all data entered since the official launch in June 2020. The primary outcome was to investigate the number of reporting centers with incomplete data in the six key elements. Incomplete data, for this specific purpose, was defined as missing or incorrectly registered data in more than 50 % of the recorded patients within each reporting center. Incorrect data registration was defined as data entered, but not in accordance with the guidelines provided by the ISSPP Registry Group, which are available on the official ISSPP website [10]. Based on this initial data completeness analysis, we evaluated reasons for incomplete data, including potential errors or mistakes owing to the structure and/or presentation of the database (labels, annotations, etc.), and, where relevant or possible, provided potential remedies.

Further, an in-depth analysis of Response Evaluation, Complications, and Follow-up were performed to assess the extent of missing data in these three key elements. These elements were chosen due to their significance with regard to reporting PIPAC data, and because these elements had missing data in the second annual PIPAC report [7]. Missing data were defined as no registered data due to either lack of data or incorrectly registered data (Figure 1). The in-depth analysis of complications included an examination of the centers that reported most complications and the frequency of severe complications per PIPAC center.

Primary outcome of the study and in-depth analysis of Response evaluation, Complications, and Follow-up. *Incomplete data were defined as either missing or incorrectly registered data in more than 50 % of the recorded patients. **Missing data were defined as no or incorrectly registered data.

The governance, legal aspects, ethical framework, variables, and implementation of the ISSPP PIPAC Database have been previously described in detail [4], 7] (Table 1).

A summary of the ISSPP PIPAC database. The in-depth analysis included the three key elements Response Evaluation, Complications, and Follow-up.

| Name | The ISSPP PIPAC database |

|---|---|

| Description | Web-based REDCap database solution for easy online access and consisting of six key elements: Patient, Consent, Treatment, Complications, Response evaluation, and Follow-up |

| Purpose | To monitor global PIPAC activity, perform quality assessment, and support international PIPAC benchmarking and research |

| Years of data registration | Since June 2020 |

| Method of data collection | Manual online input by PIPAC centers |

| No. of annual reports | 2 |

| No. of registered centersa | 30 |

| No. of reporting centersa | 16 |

| No. of patientsa | 950 |

| No. of PIPAC directed treatmentsa | 2,777 |

| In depth analysis | |

| Response evaluation | 2,705 histological response evaluations |

| Complications | 3,189 complications |

| Follow-up | 950 patients |

-

aAs of October 14th, 2024.

Results

Primary outcome

As of October 14th, 2024, the ISSPP PIPAC database contained data from 2,777 PIPAC procedures in 950 patients. Thirty PIPAC centers were registered in the database, and 16 (53 %) centers had actually included patients. Incomplete data were observed in four of the key elements, but not in Treatment and Patient. Most incomplete data were in Complications, Response Evaluation, and Follow-up (Table 2). Six of the 16 reporting centers (38 %) had no incomplete data, and no reporting center had incomplete data in all key elements.

Reporting centers (n=16) with incomplete dataa in the six key elements.

| Key element | Number of reporting centers with incomplete data, n (%) |

|---|---|

| Patient | 0 (0) |

| Consent | 1 (7) |

| Treatment | 0 (0) |

| Response evaluation | 5 (31) |

| Complications | 7 (44) |

| Follow-up | 2 (13) |

-

aIncomplete data were defined as missing or incorrectly registered data in more than 50 % of the recorded patients within each reporting center.

All centers had complete data in Patient, Consent, and Treatment elements – except one center where the majority of patients did not consent to having their information passed on to the database.

Reasons for incomplete data in Response Evaluation were due to missing data or incorrect registration of data, see below (5 centers).

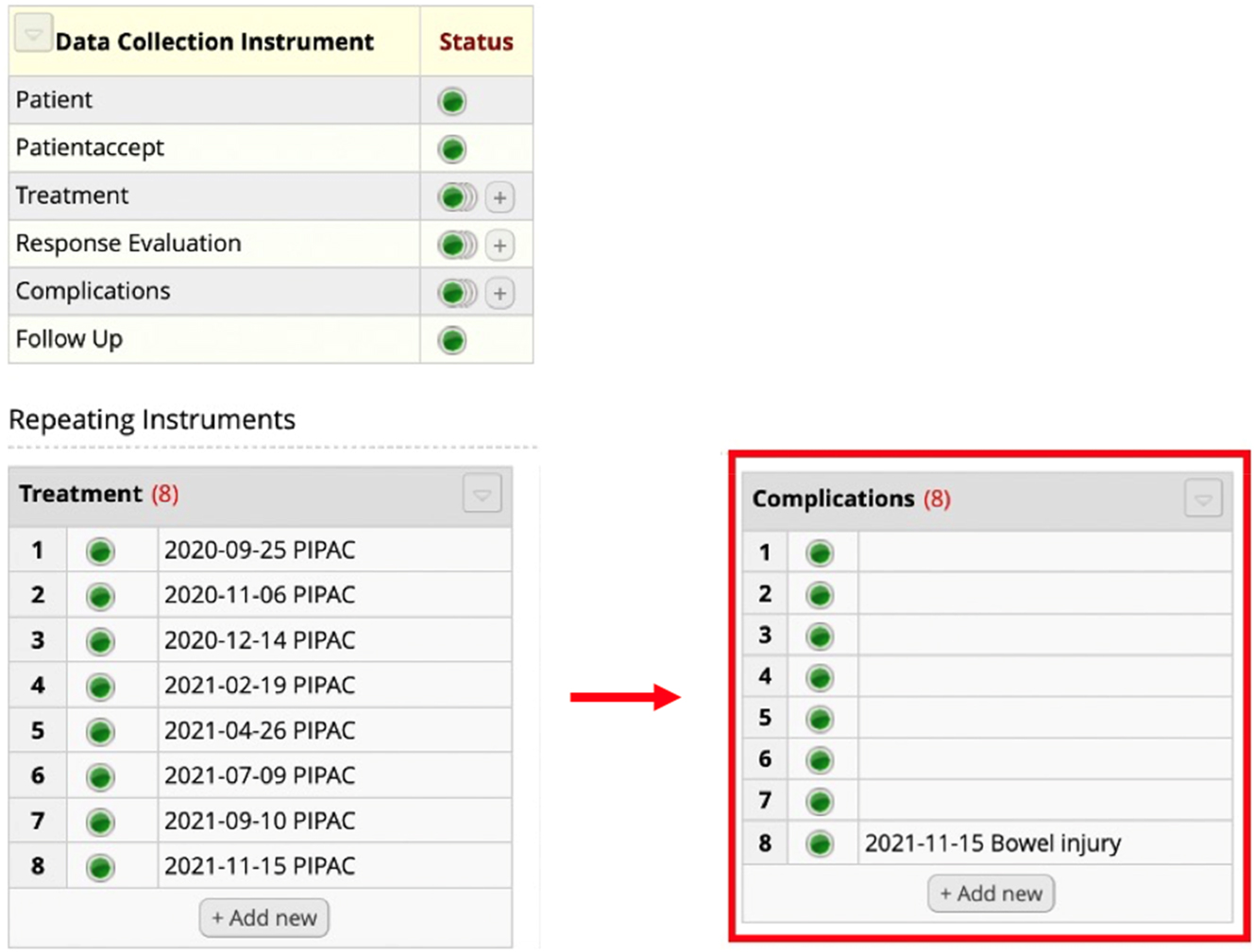

Complications had the highest amount of incomplete data (7 centers). This was due to incorrect registration of data. The major cause being centers incorrectly marking new complications without registering further data and thereby creating “empty” complication records[1] (Figure 2). For a more detailed description of this topic, please read below.

Incompleteness in the key element Complications. The patient was treated with eight PIPAC directed treatments. As highlighted in red, eight complications were registered but only one complication was provided with information as to the character of the problem (e.g., bowel injury). Seven of the complications had no registered data and are considered “empty.”

In Follow-up, incomplete data (no follow-up) were observed in two (13 %) reporting centers, only.

Results from in-depth analysis

The number of missing data in the key elements Response Evaluation, Complications, and Follow-up are listed in Table 3.

In depth analysis of missing data in Response Evaluation, Complications, and Follow-up. Missing data are divided into no data and incorrect data. No data refers to no data was registered. Incorrect data mean data were registered but not in accordance with the guidelines provided by the ISSPP Registry Group.

| Key element | Total data, n (%) | Missing data, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No data | Incorrect data | ||

| Response evaluation (n=2,705) | |||

| PRGS | 2,077 (75) | 39 (1.9) | 16 (0.8) |

| Non-PRGS | 293 (11) | 211 (72) | 1 (0.3) |

| None | 308 (11) | – | 26 (8) |

| Unknown/not specified | 27 (3.3) | – | – |

| Complications (n=3,189) | |||

| Date of complication | 3,189 (100)a | 0 (0) | 375 (12) |

| Type of complication | 3,189 (100) | 0 (0) | 360 (11) |

| Dindo-Clavien | 38 (1.2) | 6 (16) | 0 (0) |

| CTCAE | 3,151 (99) | 472 (15) | 0 (0) |

| Follow-up (n=950) | |||

| Date of follow-up | 950 (100) | 54 (5.7) | 8 (0.8)b |

| Date of death | 574 (100) | 79 (14) | – |

| Reasons for stopping PIPAC | 950 (100) | 143 (15) | 0 (0) |

-

aOne PIPAC, procedure may be accompanied by more than one registered complication, bObserved in two PIPAC, centers. PRGS, peritoneal regression grading score, CTCAE; Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events.

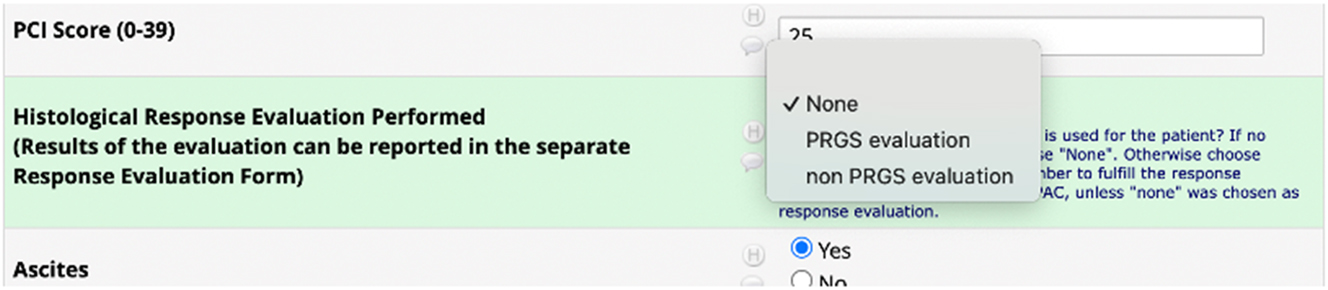

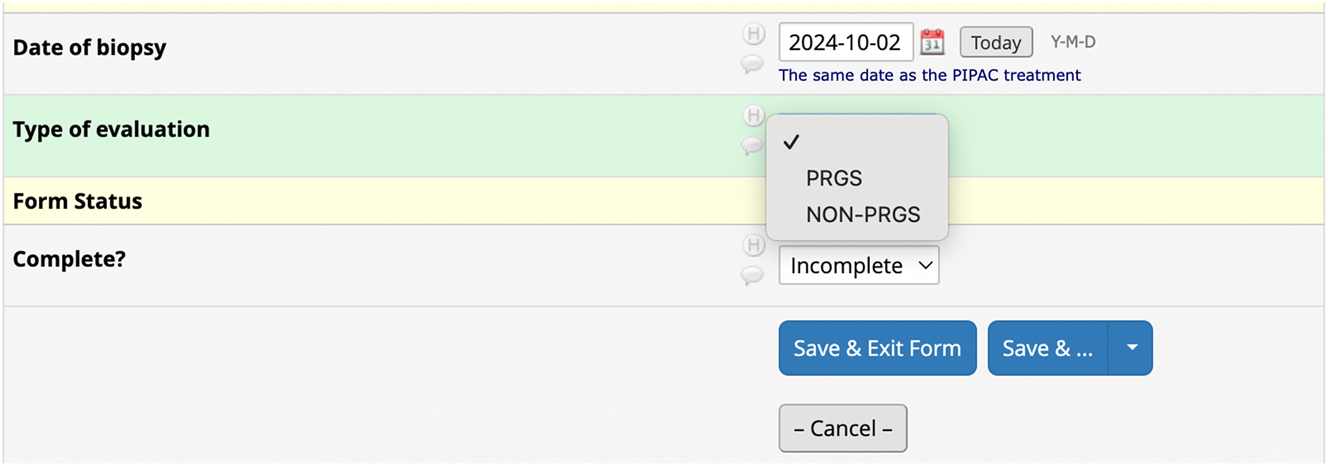

Response evaluation was registered in 2,705 out of 2,777 procedures (97 %). Evaluation by Peritoneal Regression Grading Score (PRGS)[2] had no or incorrect data in 2.7 %, only. Non-PRGS[3] was performed in 293 (11 %) procedures but the option “not available” was chosen in 211(72 %). The option “None” was chosen in 308 procedures (11 %), yet a date-matched biopsy was used for response evaluation and registered in 26 (8 %) of the procedures (i.e., incorrect data).

The complication data were noted in 88 % of all procedures and the type of complication was listed in 89 %. Dindo-Clavien (DC) and Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) classification were missing in 16 and 15 % of the complication reports, respectively. Two PIPAC centers were responsible for 84 % of the total number of registered complications. The two centers performed 68 % of all PIPAC procedures.

Frequency of complications DC≥3b and adverse events CTCAE≥3 per PIPAC varied from 0–3.3 % and 0–5.5 %, respectively, among reporting centers with more than 30 PIPACs performed (Table 4).

Frequency of Dindo-Clavien ≥ 3b and CTCAE≥3 in PIPAC procedures among centers with more than 30 PIPACs performed.

| Center | Dindo-Clavien≥3b, % | CTCAE≥3, % |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.6 | 5.5 |

| 2 | 3.3 | 0 |

| 3 | 1.9 | 2.9 |

| 4 | 0 | 3.8 |

| 5 | 0.8 | 0.8 |

| 6 | 0 | 0 |

| 7 | 0.2 | 4.6 |

| 8 | 0 | 0 |

Regarding Follow-up, 54 patients (5.7 %) had no data, while incorrect follow-up date occurred in eight patients (0.8 %) due to no follow-up performed in two centers.

Date of death was provided in 86 % of the patients reported as having died. Reasons for stopping PIPAC directed therapy were available in 85 %, but in 15 % of the patients, the reason was “other,” but not specified.

Discussion

The voluntary, noncommercial ISSPP PIPAC database has included PIPAC centers and patient data for more than 4 years and two annual reports have been published [4], 7]. Currently, 16 centers are reporting their data on PIPAC procedures to the ISSPP PIPAC database as of October 2024. Continuous monitoring of data is relevant for several reasons (e.g., database design, use, variable definitions, and reporting), and assessment of data completeness and accuracy are important criteria for this evaluation. This study assesses data completeness within the ISSPP PIPAC database and represents the first systematic audit of a prospective international PIPAC registry.

Incomplete data, when defined as either missing data in more than 50 % of the included patients or incorrectly registration of data in more than 50 %, were found in four of six key elements of the database. The key elements were Complications (7/16 reporting centers), Response Evaluation (5/16), Follow-up (2/16), and Consent (1/16). Data were complete in the key elements Patient and Treatment.

The incomplete data in Consent resulted from one center, where most patients did not consent to having their information registered in the database. Consequently, data from these patients were excluded from this study’s analysis.

Reasons for incomplete data in Complications and Response evaluation were mainly incorrect registration of data, and the reporting centers often created the same errors. In Complications, the main error was registration of complications without providing subsequent data and thereby creating “empty” complication lists. The misunderstanding seems to arise when investigators believe empty complications mean no complication has occurred. Thus, important to emphasize in the available database guidelines, that when pressing “yes” to the variable “complication (yes/no)” under the key element Treatment, the investigator must register the new complication separately under the key element Complication. If “no” is chosen, then no complications occurred, and no separate complications should be registered.

One error in registering complications have previously been a misuse of the “other”-field, with some centers listing numerous complications in the text field. However, this was not observed in this data overview.

Regarding Response evaluation, the correct method to register data is to select the type of histological response evaluation that was performed during the specific PIPAC directed treatment under the key element Treatment (Figure 3). As underlined in the guideline, the investigator should not create a separate response evaluation, if they choose “none.” On the other hand, if the investigator chooses “PRGS evaluation” or “non PRGS evaluation,” it will be necessary to create a response evaluation (Figure 4).

Under the key element treatment, the investigator should choose which kind of histological response evaluations is performed. There are three options: None, PRGS evaluation, or non-PRGS evaluation.

Creation of a new field under the key element Response evaluation. The investigator chooses whether PRGS or non-PRGS was performed and is prompted to provide additional response data.

In the Patient element, one center used initials instead of recognizable numbers as patient-ID. Thereby the center risks that two patients are included with the same initials, and therefore it cannot be recommended to use initials as patient-ID. This will be emphasized in an updated database guideline.

The in-depth analysis of Complications, Response Evaluation, and Follow-up revealed missing data in 72 % of patients with non-PRGS response evaluation. Because of overlapping between the two categories “no data” and “incorrect data,” it is difficult to differentiate whether the high number of missing data is caused only by incorrectly registration or that some investigators forget to register the non-PRGS response. The same argument applies for the missing data in Complication and Follow-up elements. However, no other variables in the in-depth analysis exceeded 16 % of missing data, which must be considered very satisfactory at the present state. In comparison, 15 out of 315 patients (4.8 %) were excluded due to “incomplete data” in a recent international registry of patients with peritoneal metastases (PM) undergoing cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) [11]. The term “incomplete data” was not further defined. Direct comparison between studies is challenging, since the present study evaluates incomplete data on a variable level, whereas the HIPEC study focused on assessment on patient level. A conservative estimate of patients excluded from the ISSPP PIPAC database due to “incomplete data” would be less than 10 %. On a variable level, one of the major databases including 492,242 patients with invasive breast cancer, the clinical stage information was missing in 29 % of the patients [12]. In that perspective, the current extent of incomplete data in the ISSPP PIPAC database seems acceptable.

It is well known that major multicenter databases must accommodate incomplete data, and that achieving a complete dataset for all included patients is unlikely [8], 13]. Missing data may have quite different clinical implications depending on the topic of the database. One study of missing data in a national health database in the United States concluded that a high prevalence of missing data was associated with differences in overall survival. This emphasizes the importance of complete documentation and registration [8]. Data completeness also depends on the dedication and resources of the involved centers, the hosting center, analysis group, and affiliated clinical societies.

Lack of data completeness is also a well-known problem in both pro- and retrospective PIPAC studies. A systematic review on quality of life in patients treated with PIPAC found moderate risk of bias due to missing data in six of nine included studies [14]. A narrative review on response evaluation in PIPAC detected a substantial amount of missing data or discontinued treatments. The review showed that missing data or discontinued treatments in more than half of patients occurred in 62 % of the included studies [15]. Similarly, this critical database evaluation detected 31 % of the reporting PIPAC centers having incomplete data in the key element Response evaluation. Absence of response evaluations may affect interpretations of PIPAC safety and efficacy, potentially biasing clinical decision-making or outcome reporting.

A retrospective study on safety of PIPAC combined with other surgical procedures reported that only 6 % of the patients have been excluded due to missing data, but this is probably due to selection [16]. Another systematic review on reasons for stopping PIPAC showed that missing data ranged from 0 to 24.4 % among the included studies [17]. These numbers are in line with the present study, where reasons for stopping PIPAC were missing in 15 % of the patients. Furthermore, the systematic review reported that one of the main limitations of the study was missing data [17]. Therefore, continued investments in data collection and correct registration remain a critical step toward more complete and trustworthy real-world data – also in the ISSPP PIPAC Database.

Limitations

Fourteen centers (47 %) registered in the ISSPP PIPAC database had not included any patients, which may introduce reporting bias. Additionally, no inter-rater reliability checks were performed in this study, potentially leading to inconsistent data interpretation across centers and compromising the accuracy and comparability of recorded outcomes. The absence of external audits may allow errors, inconsistencies, or deviations from data entry protocols to go unnoticed, thereby reducing the overall reliability and integrity of the database.

Additionally, some centers may delay data entry into the ISSPP PIPAC database, increasing the risk of missing information. To minimize this, centers are encouraged to register data in real time, while adhering to the detailed instructions provided.

New database initiatives by the ISSPP Registry Group

The high number of reporting centers with the same incorrect registration of data may reflect a fundamental error in the structure of the database, making it less intuitive and more difficult to register data correctly. To prevent this, new initiatives have been launched, based on discussions within the ISSPP Registry group during the ISSPP/PSOGI meeting in Lyon, September 2024.

The present study shows that the number of registered complications per PIPAC procedure varied across the reporting centers. Low grades of CTCAE and DC are considered less important and recent studies have only reported CTCAE≥3 or DC≥3b [1], 17], 18]. Therefore, and to reduce workload during data registration, it was decided that only CTCAE≥3 will be registered in the database in the future. However, all surgical complications will be registered using the Dindo-Clavien classification.

To minimize incomplete data in the future, Odense PIPAC Center and the ISSPP Registry Group launched an improved and individual PIPAC support program for active and new centers in 2024. An online email help desk has been established (ouh.a.pipac@rsyd.dk), which will guide both new and already reporting PIPAC centers. Also, a support team with two technical assistants has been made available by Odense PIPAC Center. Their help includes email reminders to each of the reporting PIPAC centers in need of corrections to their registered data. A new set of recommendations for registering data in the ISSPP PIPAC database has been sent to all centers, and this detailed guide is available on the ISSPP webpage as well. Furthermore, helpful text-fields are now inserted below the most difficult variables in the database to ensure more consistent data. Finally, the ISSPP Registry Group decided on a simpler approach to data from the ISSPP PIPAC Database.

Conclusions

International databases must deal with missing and inaccurate data, and this was confirmed in four of the six key elements within the ISSPP PIPAC Database. However, overall data completeness was considered satisfactory at the present state, and the ISSPP Registry Group has launched several initiatives to improve data completeness and quality to enrich future data sets and annual reports.

Acknowledgments

Martin Graversen, Sergio Gianni, Aileen Pang, Bettina Lieske, and Omar Thaher are thanked for their contribution to the ISSPP PIPAC Database.

-

Research ethics: The ISSPP PIPAC database and the study protocol were approved by the Region of Southern Denmark (GDPR, 20/18204) on April 21st, 2020, the Institutional Review Board of the University of Southern Denmark (SDU REC 20/24559) on May 5th, 2020, and by the hosting unit Odense Patient data Explorative Network (OPEN) on May 19th, 2020 (OP-114019/49984).

-

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individuals included in this study.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Conflict of interest: Marc Pocard is consultant for Thermasolutions. M. Pocard receives Research funding by Capnomed GmbH, IDImed, Thermasolutions as INSERM laboratory unit U 1275 responsible for peritoneal metastasis research. All other authors state no conflict of interest. Olivier Glehen is consultant for GAMIDA.

-

Research funding: None declared.

-

Data availability: Not applicable.

-

Previous presentation: Part of this study was presented as a poster (PO 32) at the 14th international PSOGI-ISSPP congress in Lyon the 26th of September 2024.

References

1. Di Giorgio, A, Macrì, A, Ferracci, F, Robella, M, Visaloco, M, De Manzoni, G, et al.. 10 Years of pressurized intraperitoneal aerosol chemotherapy (PIPAC): a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Cancers (Basel) 2023;15:1125. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15041125.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

2. Alyami, M, Hübner, M, Grass, F, Bakrin, N, Villeneuve, L, Laplace, N, et al.. Pressurised intraperitoneal aerosol chemotherapy: rationale, evidence, and potential indications. The Lancet Oncol 2019;20:e368–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1470-2045-19-30318-3.Search in Google Scholar

3. Solass, W, Kerb, R, Mürdter, T, Giger-Pabst, U, Strumberg, D, Tempfer, C, et al.. Intraperitoneal chemotherapy of peritoneal carcinomatosis using pressurized aerosol as an alternative to liquid solution: first evidence for efficacy. Ann Surg Oncol 2014;21:553–9. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-013-3213-1.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

4. Mortensen, MB, Glehen, O, Horvath, P, Hübner, M, Hyung-Ho, K, Königsrainer, A, et al.. The ISSPP PIPAC database: design, process, access, and first interim analysis. Pleura Perit 2021;6:91–7. https://doi.org/10.1515/pp-2021-0108.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

5. Baggaley, AE, Lafaurie, G, Tate, SJ, Boshier, PR, Case, A, Prosser, S, et al.. Pressurized intraperitoneal aerosol chemotherapy (PIPAC): updated systematic review using the IDEAL framework. Br J Surg 2022;110:10–18. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjs/znac284.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

6. Harris, PA, Taylor, R, Thielke, R, Payne, J, Gonzalez, N, Conde, JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)–a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009;42:377–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

7. Mortensen, MB, Casella, F, Düzgün, Ö, Glehen, O, Hewett, P, Hübner, M, et al.. Second annual report from the ISSPP PIPAC database. Pleura Perit 2023;8:141–6. https://doi.org/10.1515/pp-2023-0047.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

8. Yang, DX, Khera, R, Miccio, JA, Jairam, V, Chang, E, Yu, JB, et al.. Prevalence of missing data in the national cancer database and association with overall survival. JAMA Netw Open 2021;4:e211793. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.1793.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

9. Rabe, BA, Day, S, Fiero, MH, Bell, ML. Missing data handling in non-inferiority and equivalence trials: a systematic review. Pharm Stat 2018;17:477–88. https://doi.org/10.1002/pst.1867.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

10. Available from: https://isspp.org/professionals/pipac-database/.Search in Google Scholar

11. Arjona-Sanchez, A, Aziz, O, Passot, G, Salti, G, Serrano, A, Esquivel, J, et al.. Laparoscopic cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy: long term oncologic outcomes from the international PSOGI registry. Eur J Surg Oncol 2023;49:107001. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejso.2023.107001.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

12. Hoskin, TL, Boughey, JC, Day, CN, Habermann, EB. Lessons learned regarding missing clinical stage in the national cancer database. Ann Surg Oncol 2019;26:739–45. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-018-07128-3.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

13. Hunt, NB, Gardarsdottir, H, Bazelier, MT, Klungel, OH, Pajouheshnia, R. A systematic review of how missing data are handled and reported in multi-database pharmacoepidemiologic studies. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2021;30:819–26. https://doi.org/10.1002/pds.5245.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

14. Li, Z, Wong, LCK, Sultana, R, Lim, HJ, Tan, JW, Tan, QX, et al.. A systematic review on quality of life (QoL) of patients with peritoneal metastasis (PM) who underwent pressurized intraperitoneal aerosol chemotherapy (PIPAC). Pleura Perit 2022;7:39–49. https://doi.org/10.1515/pp-2021-0154.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

15. Roensholdt, S, Detlefsen, S, Mortensen, M, Graversen, M. Response evaluation in patients with peritoneal metastasis treated with pressurized IntraPeritoneal aerosol chemotherapy (PIPAC). J Clin Med 2023;12:1289. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12041289.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

16. Robella, M, Hubner, M, Sgarbura, O, Reymond, M, Khomiakov, V, di Giorgio, A, et al.. Feasibility and safety of PIPAC combined with additional surgical procedures: PLUS study. Eur J Surg Oncol 2022;48:2212–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejso.2022.05.001.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

17. Ezanno, AC, Malgras, B, Pocard, M. Pressurized intraperitoneal aerosol chemotherapy, reasons for interrupting treatment: a systematic review of the literature. Pleura Perit 2023;8:45–53. https://doi.org/10.1515/pp-2023-0004.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

18. Daniel, SK, Sun, BJ, Lee, B. PIPAC for gastrointestinal malignancies. J Clin Med 2023;12:6799. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12216799.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Review Article

- Advancements in nebulizers for pressurized intraperitoneal aerosol chemotherapy (PIPAC)

- Research Articles

- Assessing data completeness in the international society for the study of pleura and peritoneum (ISSPP) PIPAC database: a multicenter evaluation from 2020–2024

- Comparison of clinical characteristics and outcomes between patients with complicated pleural infection caused by Streptococcus anginosus group and Klebsiella pneumoniae

- Co-occurrence of peritoneal mesothelioma and genitourinary cancers: a case series with comparative outcomes

- The addition of collagenase to BromAc ® for the management of inoperable pseudomyxoma peritonei – in vitro results

- Letter to the Editor

- Adhesion obstacles effect on PIPAC patients with primary unresectable or recurrent platinum-resistant peritoneal metastasis from ovarian cancer

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Review Article

- Advancements in nebulizers for pressurized intraperitoneal aerosol chemotherapy (PIPAC)

- Research Articles

- Assessing data completeness in the international society for the study of pleura and peritoneum (ISSPP) PIPAC database: a multicenter evaluation from 2020–2024

- Comparison of clinical characteristics and outcomes between patients with complicated pleural infection caused by Streptococcus anginosus group and Klebsiella pneumoniae

- Co-occurrence of peritoneal mesothelioma and genitourinary cancers: a case series with comparative outcomes

- The addition of collagenase to BromAc ® for the management of inoperable pseudomyxoma peritonei – in vitro results

- Letter to the Editor

- Adhesion obstacles effect on PIPAC patients with primary unresectable or recurrent platinum-resistant peritoneal metastasis from ovarian cancer