Abstract

Background

Social robots have been used in different roles, for example, in caregiving, companionship, and as a therapy tool, in recent years – with growing tendency. Although we still know little about factors that influence robots’ acceptance, studies have shown that robots are possible social companions for humans that help overcome loneliness, among other use cases. Especially in the given situation of forced social isolation, social companions are needed. This social gap might be filled by robots. We hypothesized that loneliness and the need to belong increase acceptance of social robots.

Methods

One hundred forty participants were asked to fill out an online survey on social robots and their acceptance in society. Questions on robots, demographical factors, and external factors (lockdown length) were asked and personal traits were also assessed.

Results and interpretation

As expected, among other findings, loneliness of participants was positively linked to robots’ acceptance. Nevertheless, need to belong was not. We conclude from these results that social robots are a possible social instrument to overcome loneliness and that interaction with a robot cannot replace belonging to a social group because robots lack needs that humans or animals have. Also, personality traits and demographic factors were linked to robots’ acceptance. This means that, even though there are generalizable connections between robots’ acceptance and factors as loneliness, personal traits are at least of similar importance.

Discussion

Our results provide important new insights into relationships between humans and robots and their limitations. Robots can ease our loneliness but are not seen as human. Future research needs to investigate factors that influence perception and acceptance of robots. Future lab-based studies with realistic human–robot interactions will deepen our insights of human understanding, perception, and acceptance of robots.

1 Introduction

1.1 Roles of social robots

At the present moment, robots are already used in public places, such as libraries, hotels, and shopping centers, as well as in hospitals [1,2,3,4] mostly as advisers and assistants. Unlike technically assistive robots, a social robot is defined as a robot with a physical body that interacts with humans by following the behavioral norms expected by the humans [5]. It has a human-like body shape, including a head, two arms, and two legs [6].

To date, there are attempts to adapt social robots to be human companions in purely social activities, such as education and special needs [7,8,9], elderly and patient care [6,10,11,12,13], as well as personal and even intimate relationships [14,15]. There are even several examples of human relationships with robots and other artificial agents as intimate companions: The Gatebox (gatebox.ai) is a virtual anime girl appearing in a small glass-box who manages the smart home and is “in love” with her “master” [16]. Recently, there have even been a few marriages with robots, self-explained by an inability to find a partner and by extreme loneliness. Some researchers go so far as to claim that a marriage with a robot will become routine by the year 2050 [17]. These examples, however, remain an exception. Also, other studies found mixed responses to robots in intimate (not only sexual) relationships [18,19]. Nonetheless, although this field is only emerging, the bets are placed on social robots as quasi a Jack of all trades.

Especially, the prevailing situation of the COVID-19 pandemic provides opportunities to investigate roles of social robots. We believe that in such a situation of social isolation, social robots could provide both a social bond and assistance to humans. The aims of the study are twofold. First, we examine the contribution of human-related (age, gender, personality traits, loneliness and need to belong, attitudes toward robots) and contextual factors (lockdown) to acceptance of social robots. Second, we explore possible roles and qualities of social robots in private and public sectors of human lives. In Section 1.2, we elaborate our research hypotheses by providing a short literature review.

1.2 Factors influencing the acceptance of social robots

Despite vast research in this area, factors that impact robots’ acceptance and avoidance are not well understood. Although research in general has made great progress in understanding separate factors influencing robots’ acceptance, their interplay in terms of possible moderation or mediation relationships is not well studied yet.

In 2008, Nomura et al. [20] developed a seminal scale for measuring negative attitudes toward robots (NARS). Since then, this scale has been used in various contexts and has proven to be an excellent measure of participants’ attitudes toward interaction with and influence of social robots. Closely related to NARS is Robot anxiety [20] as a feeling of dread and an avoidance impulse in the presence of robots. Both measurements were found to predict avoidance behavior toward robots [20,21]. We postulate that NARS and Robot anxiety are negative predictors of a Wish to see a robot both at home and in public places (H1a and H1b).

As for further factors influencing the acceptance of social robots, the current evidence is contentious and might be context dependent [22,23]. A recent review identified controversial evidence concerning factors related to both potential users and robots, such as age or exposure [24].

Several studies have evaluated the acceptance of social robots among the elderly [25,26,27], as teaching assistants [28,29,30,31], and in medical care [32,33]. Although in some studies age and female gender were negatively related to acceptance and willingness to use a robot [23,34,35,50,53], other investigations have found no associations of acceptance of social robots with these variables [21,36,37,38], but rather with psychological factors such as loneliness and life satisfaction [26,39]. However, an interaction study indicated that women responded more positively toward the robots and their communication [38]. As for special applications of social robots as a partner or a sex partner, there is evidence that females have a less positive view on them than males [40]. Reasons for these discrepancies are currently unclear. In line with the existing literature, we postulate that age and female gender are negatively linked to Wish to have a robot at home, especially as a partner and a sex partner, and Wish to see robots in public places (H2a and H2b). Moreover, we expect that gender moderates the relationship between the NARS and a Wish to have a robot as a partner (H3).

Further studies demonstrated that education level could also play a role in forming attitudes toward robots. Also here, previous research results are mixed: Although one study showed a negative link of education and perception of robots as a social entity [41], other research did not find such a relation [41]. Crucially, higher levels of personal experience with robots and exposure to them were shown to be linked to higher robots’ acceptance [36]. We posit that Level of education (H4a), Interest in robots (H4b), and Exposure to social robots (H4c) are positively associated with a Wish to have a robot at home and in public places.

Personality factors, in particular, conscientiousness, extroversion, and neuroticism, were found to be predictors to positive attitudes toward robots [42]. However, a recent meta-analysis indicated that agreeableness, extroversion, and openness are positively correlated with robots’ acceptance, whereas conscientiousness and neuroticism did not play any role [43]. In the current study, we aim to explore the role of personality factors (Big Five) on the Wish to have social robots in different roles (friend, companion, partner, and sex partner) at home and also in public areas (EH1).

Importantly, the roles of social robots in a human society differ in different countries and cultures [44]. So, Haring et al. [45] found that, besides some similarities in robots perception, Japanese people prefer human-like robots and even trust them to do more personal tasks such as a massage, whereas Europeans see them rather as utilitarian machines. Japanese people have also shown a heightened sensitivity to anthropomorphism [46]. Koreans were even reported to perceive robots as part of society [47]. Earlier studies pointed out that Europeans are both fascinated and afraid of robots because they define humans similar to machines and perceive technology as challenging for their own nature [48]. Interestingly, there is evidence that European people perceive social robots more positively than Easterners after interacting with them [47]. The present study does not aim to test intercultural differences in robot perception, although one needs to keep in mind that the findings could differ in participants with different cultural backgrounds.

1.3 The COVID-19 pandemic and robots as a solution

Loneliness was identified as one of the possible factors influencing acceptance of social robots [49]. Now that because of the COVID-19 pandemic we are facing a drastic change in social reality all over the world, loneliness is a ubiquitous topic. Humanity faces challenges in both the private domain (at home), in terms of loneliness and isolation, and the public domain in terms of contamination risk.

Closely related to Loneliness is the Need to belong as a wish to be connected to others. A considerable body of literature has considered aspects of belonging and loneliness together. Both factors were found to be related to social and psychological functioning [50] and health outcomes [51]. Traditionally, the Need to belong has been conceptualized as a predictor of Loneliness [52]. Although the two terms are often used interchangeably [47], some studies found that they must not necessarily be interrelated [53]. The novel Dual Continuum Model of Belonging and Loneliness proposed by Lim et al. [54] strives to combine the two constructs in one model on a continuum, as independent constructs, with each contributing to the complexity of human social needs.

Social isolation might drive people to search at least some contact – even if the social agent is a machine rather than a human being. Employing social robots as social partners and companions to fight loneliness, especially in a situation of forced social isolation, could be one of the possible solutions. Moreover, these days, robots are especially advantageous because they are immune to infections and less prone to spreading infections than humans are, thus being safer than other humans as interaction partners. In its turn, a feeling of loneliness might boost acceptance of robots in different roles at home. Research with elderly people shows that a robot might help reduce isolation, improve the moods when a person feels lonely [11], and ameliorate the psychological condition of the participants [55,56]. Also, in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, there is evidence that social robots can help overcome loneliness [57] and satisfy our Need to belong. We predict that Loneliness and the Need to belong are positively associated with participants’ Wish to have a social robot at home, especially as a companion and as a friend (H5a and H5b). We also predict that the Length of the lockdown will be positively related to the Wish to have a robot at home, especially as a friend, a companion, and a sex partner (H6a). This relationship will be mediated by Loneliness (H6b).

Importantly, overcoming loneliness presupposes a certain amount of physical closeness and contact. This is of particular interest when researching social robots as a possible social agent that helps overcome a feeling of loneliness. A preferred distance can depend on the interaction and the qualities, such as emotional impact, of the robot [58]: Although little is known about a comfortable distance to a robot in an intimate relationship or at home, participants reported that in public corridors, robots entering the intimate zone of about 45 cm is considered uncomfortable [59]. And when cooperating with social robots, a comfortable distance of about 80 cm was found [60]. Therefore, we aim at exploring a comfortable Distance to a robot (EH2) and Time participant wish to spend with a robot (EH3).

Finally, earlier surveys indicated that robots were generally perceived as helpful devices and that they ought to be reliable and assistive [61,70,71]. To obtain a more global view on requirements for robots, we also explore the Roles and Tasks robots could have at home and in public places (EH4) and what Qualities robots should have (EH5).

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Participants and procedure

One hundred forty participants (11 native English speakers, 109 native German speakers, 19 participants with another native language, one did not answer this question) filled out an online survey (28 males, 111 females, 1 nonbinary; mean age = 26.06 years, SD = 8.33; 40.7% with university qualification [bachelor and above]; the majority [about 97%] of the participants came from Germany or another European country). The survey was conducted in both German (for German native speakers) and English (for others). All non-native English-speaking participants were fluent in English by self-report. The participants were recruited in social networks such as Facebook® and Linkedin® and via the subject pool system SONA at the University of Potsdam during a 6-week period between April 2020 and May 2020.

Before commencing the study, the experimental procedures were reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee at the University of Potsdam (approval number 25/2020). All participants submitted their informed consent at the beginning of the survey by clicking the relevant online link and were reimbursed with course credits for their participation if required. Participants could also enter their email address to take part in a raffle of one of two vouchers.

The questionnaire was created and hosted with SoSci Survey [62]. Participants were told that the study was dedicated to social robots and their acceptance in the society. They were instructed to answer the survey questions honestly and spontaneously. At the end of the survey, participants were debriefed and given a link to leave their internal subject pool ID for receiving a credit or entering an email address to take part in the raffle.

2.2 Measures

The following variables were measured: (1) Human-related factors: Demographic factors (age, gender, native language, education, country of residence at the moment of the survey conduction), Personality, Loneliness, Need to belong; (2) Attitude factors: NARS, Robot anxiety (to a robot at home and on public places), Wish to have a robot in different spheres of life (at home as a friend, companion, partner, sex partner; in public places), Distance to a robot, Time spent with a robot at home and in public places, Interest in robots, Exposure to social robots; (3) Robot-related factors: Roles and Tasks robots could fulfill at home and in public places, Qualities robots should have at home and in public places; (4) Context-related factors: Whether there was a Lockdown in the country/federal state they lived in, and if yes, for how long (Length of Lockdown).

The variables are summarized in Table 1.

Overview of the variables in the study

| Independent variables | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human-related factors | Context-related factors | |||||||

| Demographic factors | Personality factors | Loneliness | Need to belong | Attitudes toward robots | Robot anxiety | Lockdown | ||

| Age, gender, native language, education, and the country of residence at the moment of the survey conduction | Big-Five-Inventory-10 [63] (English and German versions) | Revised Loneliness Scale [65] (the German version by Döring and Borzt [66]) | Need to belong scale [68], formal back translation | Negative attitudes toward robots scale [20] (the German version adapted from Wullenkord [69]) | Robot Anxiety Scale [20] (the German version adapted from Wullenkord [69]) | If there was a Lockdown in the country/federal state | Lockdown length | |

| Dependent variables | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human-related measures | Robot-related measures | |||||||

| Demographic factors | Personality factors | Loneliness | Need to belong | Attitudes toward robots | Robot anxiety | Lockdown | ||

| Wish to have a robot | Distance to a robot | Time spent with a robot | Interest in social robots | Exposure to social robots | Roles of robots | Tasks of robots at home | Tasks of robots in public places | Qualities of robots |

| Modified items from the Acceptability survey [61] | Single item: How close should a robot come to you? On a scale from 1 (very far) to 5 (very close) | Single item: How much time would you spend together with a robot? On a scale from 1 (no time at all) to 5 (very much time) | Single item: How much are you interested in human–robot interaction? On a scale from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much) | Single item: How much exposure to social robots do you have? On a scale from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much) | Modified items from the Cognition questionnaire [72], the Views about robots questionnaire [73]. Options: Assistant, helper, servant, companion, partner, friend, or others | Modified items from the Cognition questionnaire [72], the Views about robots questionnaire [73]. Options: Healthcare, childcare, cooking, cleaning, shopping, entertainment, friendship, intimate, or others | Modified items from the Cognition questionnaire [72], the Views about robots questionnaire [73]. Options: Health, childcare, transportation, cleaning, shopping assistance, entertainment, guidance, no task, or others | Modified items from the Cognition questionnaire [72]. What qualities a companion robot and a robot in public places should have? On a scale from 1 (not at all) to 5 (to a great extent): Controllable, predictable, considerate, efficient, human-like, reliable, agreeable, trustworthy, compassionate, talkative, breakable, empathic, emotional |

2.2.1 Independent variables

2.2.1.1 Human-related factors

2.2.1.1.1 Demographic factors

Following factors were measured: Age, gender, native language, education, and the country of residence at the moment of the survey conduction.

2.2.1.1.2 Personality factors

Participants’ personality traits were measured with the Big-Five-Inventory-10 [63] (English and German version). The inventory assesses five most widely accepted personality dimensions: Openness, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness, and Neuroticism [64]. The short version of the personality inventory was chosen for time reasons. The validity of the short version was proven to be sufficiently good: With only 25% of the full The Big Five Inventory (BFI)-44 scale items, it still predicts 70% of its variance [63]. Because of a very small number of items per scale, test–retest reliability is a better measure for the scale reliability than Cronbach’s alpha [63]. The test–retest reliability of the BFI-10 was estimated as r tt = 0.56.

Each personality dimension was measured with two items, rated on a five-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Sample items were as follows: “I see myself as someone who has few artistic interests” (Openness, reversed-scored), “I see myself as someone who does a thorough job” (Conscientiousness), “I see myself as someone who is reserved” (Extraversion, reversed-scored), “I see myself as someone who is generally trusting” (Agreeableness), and “I see myself as someone who is relaxed, handles stress well” (Neuroticism, reversed-scored).

2.2.1.1.3 Loneliness

Loneliness was assessed with 20 items of the revised Loneliness scale developed by Russell et al. [65] (the German version by Döring and Bortz [66]), rated on a five-point Likert scale from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely). Sample items included: “My interests and ideas are not shared by those around me,” “I can find companionship when I want it” (reversed-scored), and “People are around me but not with me.” Internal consistency of the English scale was reported to be excellent: 0.92 [67].

2.2.1.1.4 Need to belong

Need to belong was measured by the Need to belong scale with ten items [68]. The items were obtained using formal back translation. The answers were given on a five-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Sample items included the following: “I need to feel that there are people I can turn to in times of need,” “I want other people to accept me,” and “It bothers me a great deal when I am not included in other people’s plans.” Cronbach’s alpha was reported to range from 0.78 to 0.87 [67].

2.2.1.1.5 Attitudes toward robots

The Attitudes toward robots was measured by the NARS scale by Nomura et al. [20] (the German version adapted from Wullenkord [69]), rated on a five-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The scale consists of 14 items and includes three subscales: Negative attitude toward interaction with robots (S1), Negative attitude toward social influence of robots (S2), and Negative attitude toward emotional interactions with robots (S3). Sample items included: “I would feel uneasy if I were given a job where I had to use robots” (S1), “I would feel uneasy if robots really had emotions” (S2), and “I would feel relaxed talking with robots” (S3, reversed-scored).

As reported by Nomura et al. [20] with Japanese samples, the Cronbach’s alphas of the scales were acceptable: 0.750 (S1), 0.0782 (S2), and 0.648 (S3) [70]. Syrdal et al. [71] conducted a reliability analysis of the English version of the scale and after removing three items (“I would feel nervous operating a robot in front of others” (S1), “The word ‘robot’ means nothing to me” (S2), and “I feel that in the future, society will be dominated by robots” (S2)) reported a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.80 of the whole revised scale. Wullenkord [69] reported similar Cronbach’s alphas in her experiments (0.76–0.84) for a German sample. However, factor analysis by Syrdal et al. [71] also showed that the English version had subtle differences to the Japanese scales. These discrepancies with the original scale are in line with the assumption of Nomura et al. [20] that Attitudes toward robots are subject to cultural differences and artifacts. In the present study, scales were adopted from the original study. In the Analysis section of 2.3.3 Scales characteristics this article, results of the reliability analysis conducted for this particular sample are reported.

2.2.1.1.6 Robot anxiety

Robot anxiety was measured separately for a companion robot and a robot in public places by the slightly simplified 11 items of the robot anxiety scale (RAS) by Nomura et al. [20] (German version adapted from Wullenkord [69]), rated on a six-point Likert scale from 1 (I do not feel anxiety at all) to 6 (I feel very anxious). It includes three subscales: Anxiety toward communication capability of robots (S1), Anxiety toward behavioral characteristics of robots (S2), and Anxiety toward discourse with robots (S3). It was measured for both a robot at home and in public places. The items were preceded by a question: “Imagine a robot at home (in a public place, respectively). Please state how anxious you feel when thinking about the following things.” Sample items included: “Robots might talk about something irrelevant during the conversation” (S1), “I wonder what the robot will do” (S2), and “I wonder whether the robot will understand what I am talking about” (S3). With a Japanese sample, Cronbach’s alphas of the scales were good: 0.840 (S1), 0.844 (S2), and 0.796 (S3) [20]. For a German sample, similar Cronbach’s alphas were found (0.80–0.85) [69]. In the Analysis section of 2.3.3 Scales characteristics this article, results of the reliability analysis of the RAS for this particular sample are reported.

2.2.1.2 Context-related factors

The participants were also asked if there was a Lockdown in the country/federal state they lived in, and if yes, for how long (Length of lockdown).

2.2.2 Dependent variables

2.2.2.1 Human-related measures

2.2.2.1.1 Acceptance of social robots

To examine robots’ acceptance, we used modified items from the Acceptability survey by Nomura et al. [61].

In particular, our participants were asked about their Wish to see a robot at home, as a companion, as a friend, as a partner, as a sex partner, at the counter, at school, in a hospital, in other public places or if they did not wish to see any robots at all (please state to what extent you agree with the following statements. “I would like to see a robot”: At home; as my companion; as my friend; as my partner; as my sex partner; at the counter; at school; in a hospital; in other public places; no robots at all). Furthermore, participants were asked to what extent they could imagine a robot to be their companion and to work in public places, respectively (“To what extent can you imagine a robot to” 1. be your companion? 2. work in public places?). All the answers were given on a five-point Likert scale from 1 (not at all) to 5 (to a great extent).

2.2.2.1.2 Distance to a robot, time spent with a robot

For both companion robots and robots in public places, participants were also asked how close a robot should come to them, from 1 (very far) to 5 (very close) and how much time they would spend together with a robot, from 1 (no time at all) to 5 (very much time).

2.2.2.1.3 Interest in and exposure to social robots

In addition, our participants were asked if they were interested in socials robots and familiar with them.

2.2.2.2 Robot-related measures

Various expectations of robots were assessed using a combination of modified items from the Cognition questionnaire by Dautenhahn et al. [72] and the Views about robots questionnaire by Ezer et al. [73].

2.2.2.2.1 Roles of robots

Participants were asked what role a robot at their home should have: assistant, helper, servant, companion, partner, friend, or others. They could state that they did not want to have a robot a home at all or enter an answer into a free-text field.

2.2.2.2.2 Tasks of robots

In the next question, they were asked about tasks a robot in public places should be able to carry out: health, childcare, transportation, cleaning, shopping assistance, entertainment, guidance, no task, or others. Here, it was also possible to add a free-text answer. Further, it was inquired what tasks a robot at home should be able to carry out: healthcare, childcare, cooking, cleaning, shopping, entertainment, friendship, intimate, or others.

2.2.2.2.3 Qualities of robots

Finally, our participants had to state the qualities a companion robot and a robot in public places should have on a five-point Likert scale from 1 (not at all) to 5 (to a great extent). The items included: controllable, predictable, considerate, efficient, human-like, reliable, agreeable, trustworthy, compassionate, talkative, breakable, empathic, and emotional.

Table 1 provides an overview of the variables in the study. Specific questions administrated to the participants can be found on the open Science framework (OSF) under the following link: https://osf.io/um7t8/.

2.3 Data preparation

2.3.1 Data cleaning

Statistical analyses were done with SPSS Version v.25 software package. Five participants were excluded from the analyses because of extreme survey accomplishment time (less than 4.2 min, whereas the mean time to accomplish the survey was approximately 14 min; in addition, two of them had more than eight missing answers, which might point to an unserious attitude to the survey). This yielded the final sample size of N = 135. A dummy variable was calculated for gender, with values: 0 = “male,” 1 = “female.” Another dummy variable was calculated for education, with values: 0 = “lower than university level,” 1 = “university level (at least bachelor).” Finally, a dummy variable was calculated for native language, with values: 0 = “German,” 1 = “any other.”

2.3.2 Analysis strategies

Normality of the data was first checked using a Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. The majority of the variables were not normally distributed except for NARS, NARS S1, and RAS (both public and companion). Therefore, nonparametric tests were used for the analyses. Three types of statistical analyses were then conducted to answer predictions of the study: Correlation, regression, and moderation/mediation analyses. Statistical significance was assumed at the 5% level.

2.3.2.1 Correlation analysis

Correlative relationships between the variables (human-related factors, attitude factors, and robot-related factors) were assessed with the Spearman’s correlation test.

2.3.2.2 Regression analysis

First, we investigated what factors predict a Wish to have a robot in private contexts: (1) as a friend, (2) as a companion, (3) as a sex partner, (4) at home, and (5) as a partner. We regressed age, gender, education, language, Lockdown, Loneliness (Intimate, Social other, Affiliative), Need to belong, NARS (S1–S3), RAS for robot as a companion (S1–S3), Exposure to social robots, and Interest in social robots on the outcomes (1)–(5).

Second, we investigated what factors predict a Wish to have a robot in public contexts: (6) at the counter, (7) at school, (8) in a hospital, (9) in other public places, as well as (10) to have no robots at all. We regressed age, gender, education, language, Lockdown, Loneliness (Intimate, Social other, Affiliative), Need to belong, NARS (S1–S3), RAS for public places (S1–S3), Exposure to social robots, and Interest in social robots on the outcomes (6)–(10).

Before doing the multiple regression analysis, the distributional assumptions for the multiple regression were checked and imposed.[1]

2.3.2.3 Moderation and mediation analyses

Moderation was calculated using PROCESS Macro, Model 1, and mediation was calculated using PROCESS Macro, Model 4 [74]. In mediation, one variable influences another variable through a mediator variable. In moderation, one variable (moderator) affects the direction and/or strength of the relation between two other variables.

2.3.3 Scales characteristics

The Big Five scores were calculated according to Rammstedt and John [63]. The respective items of the Loneliness, Need to belong, and NARS scales were inverted for the analysis. The reliability of the scales was tested for the whole sample (N = 135).

2.3.3.1 Loneliness

Cronbach’s alpha of the Loneliness scale was very good: 0.92. Previous research showed, however, a tendency for higher reliability estimates in samples of people who are separated from their social networks, such as immigrants [75]. Previous studies as well demonstrated that Loneliness, besides a general factor, can be explained by three sub-factors: Intimate others, Social others, and Affiliative environment [76,77]. Cronbach’s alphas of the subscales were good to acceptable (Intimate others 0.89, Social others 0.84, and Affiliative environment 0.75). Further in the present article, Loneliness is treated as both a monofactorial and a polifactorial construct with three dimensions (Intimate others, Social others, and Affiliative environment), built following McWhirter [77].

2.3.3.2 Need to belong

Cronbach’s alpha of the Need to belong scale was good: 0.84. Because the Need to belong scale was translated by the authors into German, its characteristic for the German sample (n = 103) was further scrutinized. Cronbach’s alpha of the German Need to belong scale was good: 0.83.

2.3.3.3 NARS

Cronbach’s alpha of the NARS scale was good: 0.86; Cronbach’s alphas of the subscales were ranging from acceptable (S1, 0.75, S2 0.76) to minimally acceptable (S3 0.68) [70].

2.3.3.4 RAS

Robot Anxiety was calculated separately for a robot in public places and a companion robot. Cronbach’s alpha of the former was good: 0.87, and of the latter excellent 0.89 [70]. For the subscales, Cronbach’s alpha was ranging from acceptable to excellent: 0.72 and 0.80 (S1), 0.91 and 0.92 (S2), and 0.85 and 0.90 (S3).

Results of the reliability (internal consistency) of all scales used in the study are summarized in Table 2.

Results of the reliability (internal consistency) of all scales used in the study

| Scale | Cronbach’s alpha |

|---|---|

| Loneliness scale | 0.92 |

| Need to belong scale | 0.84 |

| NARS | 0.86 |

| RAS | 0.87 (public spaces), 0.89 (companion robot) |

3 Results

3.1 H1, H2, H4, H6 correlation analyses

Spearman’s rank correlation was calculated separately between (1) NARS and RAS, (2) Personality variables, and (3) Loneliness and Need to belong and Wish to see a robot at home and in public places in different roles. The results are summarized in Tables 3–5.

Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients (r s) between NARS, RAS, and Wish to see a robot at home/in public places

| At home | As a companion | As a friend | As a partner | As a sex partner | No robot | At the counter | At school | In a hospital | In other public places | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NARS | −0.461** | −0.440** | −0.365** | −0.184* | −0.179* | 0.330** | −0.387** | −0.394** | −0.335** | −0.458** |

| NARS_S1 | −0.366** | −0.334** | −0.219* | −0.101 | −0.090 | 0.355** | −0.346** | −0.346** | −0.357** | −0.461** |

| NARS_S2 | −0.381** | −0.361** | −0.310** | −0.165 | −0.135 | 0.229* | −0.325** | −0.326** | −0.232* | −0.305** |

| NARS_S3 | −0.470** | −0.515** | −0.483** | −0.248* | −0.298** | 0.227* | −0.286** | −0.313** | −0.227* | −0.384** |

| RAS Public | −0.153 | −0.146 | −0.109 | −0.069 | −0.129 | 0.200* | −0.097 | −0.069 | −0.129 | −0.147 |

| RAS Public S1 | 0.037 | 0.033 | 0.097 | 0.031 | 0.001 | 0.042 | −0.027 | 0.086 | 0.026 | 0.036 |

| RAS Public S2 | −0.212* | −0.199* | −0.175* | −0.105 | −0.168 | 0.237* | −0.135 | −0.066 | −0.129 | −0.245* |

| RAS Public S3 | −0.112 | −0.115 | −0.110 | −0.064 | −0.093 | 0.160 | −0.076 | −0.109 | −0.144 | −0.103 |

| RAS Companion | −0.145 | −0.168 | −0.121 | −0.164 | −0.169* | 0.173* | −0.056 | −0.040 | −0.100 | −0.098 |

| RAS Companion S1 | 0.002 | 0.005 | 0.053 | −0.094 | −0.078 | 0.099 | 0.062 | 0.114 | 0.048 | 0.054 |

| RAS Companion S2 | −0.282** | −0.221* | −0.200* | −0.220* | −0.233* | 0.197* | −0.107 | −0.086 | −0.148 | −0.191* |

| RAS Companion S3 | −0.083 | −0.126 | −0.114 | −0.086 | −0.103 | 0.104 | −0.067 | −0.086 | −0.101 | −0.063 |

Note. NARS = Negative Attitudes toward robots. RAS = Robot Anxiety. *p < 0.05. **p < 0.001. Significant correlations are marked in bold.

Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients (r s) between personal and demographic qualities and acceptance of robots at home/in public places in different roles

| At home | As a companion | As a friend | As a partner | As a sex partner | No robot | At the counter | At school | In a hospital | In other public places | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extraversion | −0.097 | −0.130 | −0.038 | 0.007 | −0.064 | 0.002 | −0.005 | 0.034 | 0.001 | −0.019 |

| Neuroticism | 0.020 | −0.030 | 0.003 | −0.123 | 0.038 | 0.015 | 0.050 | 0.035 | 0.113 | 0.093 |

| Openness | −0.085 | −0.011 | −0.016 | −0.070 | −0.018 | 0.079 | −0.107 | −0.107 | −0.116 | −0.143 |

| Conscientiousness | −0.103 | −0.097 | −0.064 | −0.138 | −0.149 | 0.016 | −0.087 | −0.207* | −0.141 | −0.167 |

| Agreeableness | 0.124 | 0.019 | 0.026 | 0.043 | 0.094 | −0.022 | −0.012 | 0.133 | −0.006 | −0.035 |

| Gender | −0.082 | −0.003 | 0.016 | −0.125 | −0.169 | 0.037 | −0.074 | −0.017 | −0.023 | 0.031 |

| Age | 0.136 | 0.099 | 0.082 | 0.078 | 0.125 | −0.150 | −0.048 | −0.017 | −0.202* | 0.026 |

| Education | 0.180* | 0.077 | 0.102 | 0.051 | 0.070 | −0.087 | 0.055 | 0.101 | −0.004 | 0.104 |

| Language | 0.239* | 0.011 | 0.113 | 0.187* | 0.197* | −0.161 | 0.038 | 0.095 | 0.028 | 0.117 |

| Lockdown | −0.107 | 0.038 | −0.001 | −0.053 | −0.139 | 0.035 | −0.060 | −0.173* | −0.105 | −0.024 |

| Lockdown length | 0.118 | −0.027 | 0.120 | 0.160 | 0.295* | −0.045 | −0.037 | 0.103 | 0.117 | −0.049 |

| Exposure to robots | 0.212* | 0.316** | 0.207* | 0.216* | 0.177* | −0.191* | 0.191* | 0.352** | 0.411** | 0.293** |

| Interest in robots | 0.301** | 0.350** | 0.307** | 0.102 | 0.127 | −0.352** | 0.196* | 0.328** | 0.392** | 0.383** |

Note. Gender is coded as dummy variable with values 0 = male, 1 = female. Education is coded as dummy variable with values 0 = lower than bachelor, 1 = higher than bachelor. Language is coded as dummy variable with values 0 = German, 1 = other. Lockdown is coded as dummy variable with values 1 = lockdown, 2 = no lockdown. *p < 0.05. **p < 0.001. Significant correlations are marked in bold.

Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients (r s) between Loneliness, Need to belong, and Wish to see a robot at home/in public places

| Loneliness IN | Loneliness | Loneliness AF | Loneliness SO | Need to belong | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| At home | 0.147 | 0.135 | 0.059 | 0.114 | −0.110 |

| As a companion | 0.222* | 0.225* | 0.084 | 0.184* | −0.064 |

| As a friend | 0.258* | 0.303** | 0.095 | 0.229* | −0.044 |

| As a partner | 0.230* | 0.247* | 0.014 | 0.312** | −0.176* |

| As a sex partner | 0.267* | 0.267* | 0.110 | 0.292** | −0.101 |

| No robot | −0.097 | −0.082 | −0.073 | −0.059 | 0.071 |

| At the counter | 0.038 | 0.052 | −0.042 | 0.035 | −0.028 |

| At school | 0.115 | 0.131 | −0.011 | 0.076 | 0.040 |

| In a hospital | 0.074 | 0.072 | 0.049 | −0.030 | 0.054 |

| In other public places | 0.122 | 0.142 | 0.020 | 0.020 | 0.008 |

Note. *p < 0.05. **p < 0.001. Significant correlations are marked in bold. Loneliness AF = Loneliness affiliative environment. Loneliness IN = Loneliness intimate others. Loneliness SO = Loneliness social others.

As seen in Table 3, NARS have a small positive association with Wish to have no robot at home or in public places and small to moderate negative associations to having a robot at home, as a companion, a friend, a partner, or a sex partner (H1a). NARS also have a small to moderate negative association with Wish to see a robot at the counter, at school, in a hospital, and in other public places (H1a). Especially, the sub-factor of Negative attitudes toward emotional interactions with robots (NARS S3) plays a role.

Robot anxiety toward a robot both as a companion and in public places is positively associated with a refusal to have a robot at all (H1b). The former, especially the Anxiety about the behavioral characteristics of a robot (RAS Companion S2), is also negatively linked to having a robot as a sex partner. The majority of correlations can be classified as small or moderate.

Interestingly, the Anxiety to communication or discourse with robots (RAS S1 and RAS S3) both as a companion and in public places is not or almost not linked to the Wish to have a robot in any of these roles. The majority of negative, although weak, associations with different roles for robots exist related to the Behavioral aspect of robot anxiety (RAS S2), namely, how the robot would move or act.

Further, as shown in Table 4, age was negatively associated with an Acceptance of a robot in a hospital (H2a). Contrary to our expectations, no other correlations were found between age (H2a) and gender (H2b) of participants and a Wish to have a robot at home or in public places.

As expected, education was positively linked to Wish to have a robot at home (H4a): Participants with university education were rather in favor of getting a robot.

In line with our expectations, the more previous Exposure participants had with social robots and the more they were interested in them, the more they were willing to have a robot at home and in public places in most of the roles (H4b and H4c). Again, the majority of correlations can be categorized as small or moderate.

As postulated, our results show that the lonelier a person feels, the more disposed he or she is to have a robot as a companion, as a friend, a partner, and even as a sex partner (H5a). That being said, the separate Loneliness subscales were related to this wish in a different way. Although the Intimate others and the Social others aspects of Loneliness were linked to all the four potential roles of the robot, the Affiliative environment aspect was not associated with any of them. The Intimate others aspect focuses on the lack of companionship and isolation, the Social others aspect deals with being close to other people and having someone to turn to, and the Affiliative environment aspect is related to being a part of a social group and not feeling alone.

However, Need to belong was negatively linked only to the Wish to have a robot as a partner (H5b). This shows that the more a person wants to belong and to be accepted by other people, the less they can imagine having a robot as a partner. Apparently, such a person does not consider an artificial agent as possible substitute as human bonds.

Almost all other correlations can be classified as weak or moderate (0.20 to 0.39). Willingness to see a robot in various public places (counter, school, hospital, other public places) was not linked to any of the variables in question. Finally, the longer a Lockdown in the country had been, the more favorable the participants were to having a robot as their sex partner (H6a). This relationship was not mediated by Loneliness (H6b, Table 6).

Model coefficients of Lockdown length as a predictor, Loneliness as mediator, and Wish to have a robot as a sex partner as a criterion

| β | SE | T | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 0.502 | 0.271 | 1.857 | 0.066 |

| Total effect lockdown | 0.016 | 0.006 | 2.835 | <0.05* |

| Direct effect lockdown | 0.014 | 0.005 | 2.665 | <0.05* |

| Effect loneliness | 0.304 | 0.118 | 2.584 | <0.05* |

| Indirect effect lockdown | 0.001 | 0.002 | — | 0.095 |

| R 2 = 0.13, MSE = 0.666 | ||||

| F(1,101) = 7.58, p < 0.001 | ||||

Note. Calculated with PROCESS Macro, Model 4 [74].

In summary, various parameters such as Loneliness, Attitudes toward robots, Robot anxiety, Exposure to and Interest in robots, education and native language, but not personality qualities (except for Conscientiousness), or gender were found to be linked to Acceptance of a robot at home in different qualities. Age was only negatively associated with the Wish to see a robot in a hospital.

3.2 Exploratory analyses EH1–EH3

Conscientiousness was negatively associated with a robot at school (EH1). No other correlations were found between Big Five personality measures (EH1) of participants and a Wish to have a robot at home or in public places.

EH2 and EH3 were tested using a Wilcoxon signed-rank test. Distance to a robot (EH2) and Time spent with a robot companion at home and a robot in public places (EH3) did not differ significantly. However, there was a slight descriptive tendency showing that in public places, participants prefer to stay further to robots (M home = 2.71, M public = 2.49, Z = −1.68, p = 0.09) and wish to spend more time with them (M home = 2.21, M public = 2.39, Z = −1.28, p = 0.20).

3.3 Predictors of robots’ acceptance

The results of the regression analyses are summarized in Tables 7 and 8.

Factors predicting Wish to have a robot as a friend, as a companion, as a sex partner, at home, and as a partner

| At home | As a companion | As a friend | As a sex partner | As a partner | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | t | B | SE | t | B | SE | t | B | SE | t | B | SE | t | |

| Loneliness IN | −4.44* | 2.92 | −2.31 | 0.42* | 0.25 | 2.12 | 0.42* | 0.21 | 2.13 | ||||||

| NARS S3 | −0.39* | 0.26 | −2.34 | −0.40* | 0.20 | −2.45 | −0.44* | 0.19 | −2.37 | ||||||

| Exposure | −1.22* | 0.53 | −2.79 | ||||||||||||

| Exposure_sq | 1.49** | 0.10 | 3.45 | ||||||||||||

| Language | 0.32 | 0.29 | 2.02 | ||||||||||||

| Loneliness AF | −0.62* | 0.28 | −2.27 | ||||||||||||

| Loneliness IN sq | 9.42* | 1.26 | 2.27 | ||||||||||||

| Loneliness IN cub | −5.11* | 0.17 | −2.23 | ||||||||||||

| R 2 | 0.62** | 0.52** | 0.50** | 0.50 | 0.56 | ||||||||||

| F | 7.07 | 3.60 | 2.73 | 1.39 | 1.18 | ||||||||||

Note. Only significant predictors are included. NARS S3 = Negative attitudes toward robots interaction. Loneliness AF = Loneliness affiliative environment. Loneliness IN = Loneliness intimate others. Loneliness IN sq = Loneliness intimate others square. Loneliness IN cub = Loneliness intimate others cubic. *p < 0.05. **p < 0.001. Method: HC3.

Factors predicting Wish to see a robot at the counter, at school, in hospital, in other public places, and to have no robots

| At the counter | At school | In hospital | Other public places | No robot | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | t | B | SE | t | B | SE | t | B | SE | t | B | SE | t | |

| Lockdown | −0.30* | 0.36 | −2.45 | ||||||||||||

| Openness | −0.20* | 0.13 | −2.09 | −0.21* | 0.12 | −2.65 | −0.20* | 0.10 | −2.77 | ||||||

| NARS S1 | −0.35* | 0.17 | −3.,15 | −0.36** | 0.14 | −4.48 | −0.35** | 0.13 | −4.38 | −0.46** | 0.17 | −4.05 | 0.50** | 0.15 | 5,78 |

| NARS S2 | 0.21* | 0.14 | 2.10 | ||||||||||||

| Exposure | 0.31** | 0.10 | 3.91 | 0.44** | 0.10 | 5.37 | |||||||||

| Conscientiousness | −0.21* | 0.13 | −2.69 | −0.17* | 0.10 | −2.39 | |||||||||

| Agreeableness | 0.21* | 0.13 | 2.58 | ||||||||||||

| Age | −0.26* | 0.02 | −3.19 | ||||||||||||

| Interest | 0.38** | 0.07 | 4.67 | ||||||||||||

| RAS Public S2 | −0.26* | 0.08 | −3.17 | ||||||||||||

| RAS Public S3 | 0.18* | 0.08 | 2.10 | ||||||||||||

| Gender | 0.21* | 0.16 | 2.18 | ||||||||||||

| Loneliness IN | −0.18* | 0.15 | −2.11 | ||||||||||||

| R 2 | 0.34** | 0.39** | 0.38** | 0.52** | 0.26** | ||||||||||

| F | 3.90 | 12.65 | 19.20 | 12.83 | 18.04 | ||||||||||

Note. Only significant predictors are included. NARS S1 = Negative attitudes toward robots’ interaction. NARS S3 = Negative attitudes toward robots’ emotional interaction. Loneliness IN = Loneliness intimate others. RAS Public S2 = Robot anxiety behavioral characteristics. RAS Public S3 = Robot anxiety discourse. Gender is coded as dummy variable with values 0 = male, 1 = female. Lockdown is coded as dummy variable with values 1 = lockdown, 2 = no lockdown. *p < 0.05. **p < 0.001. Method: backward.

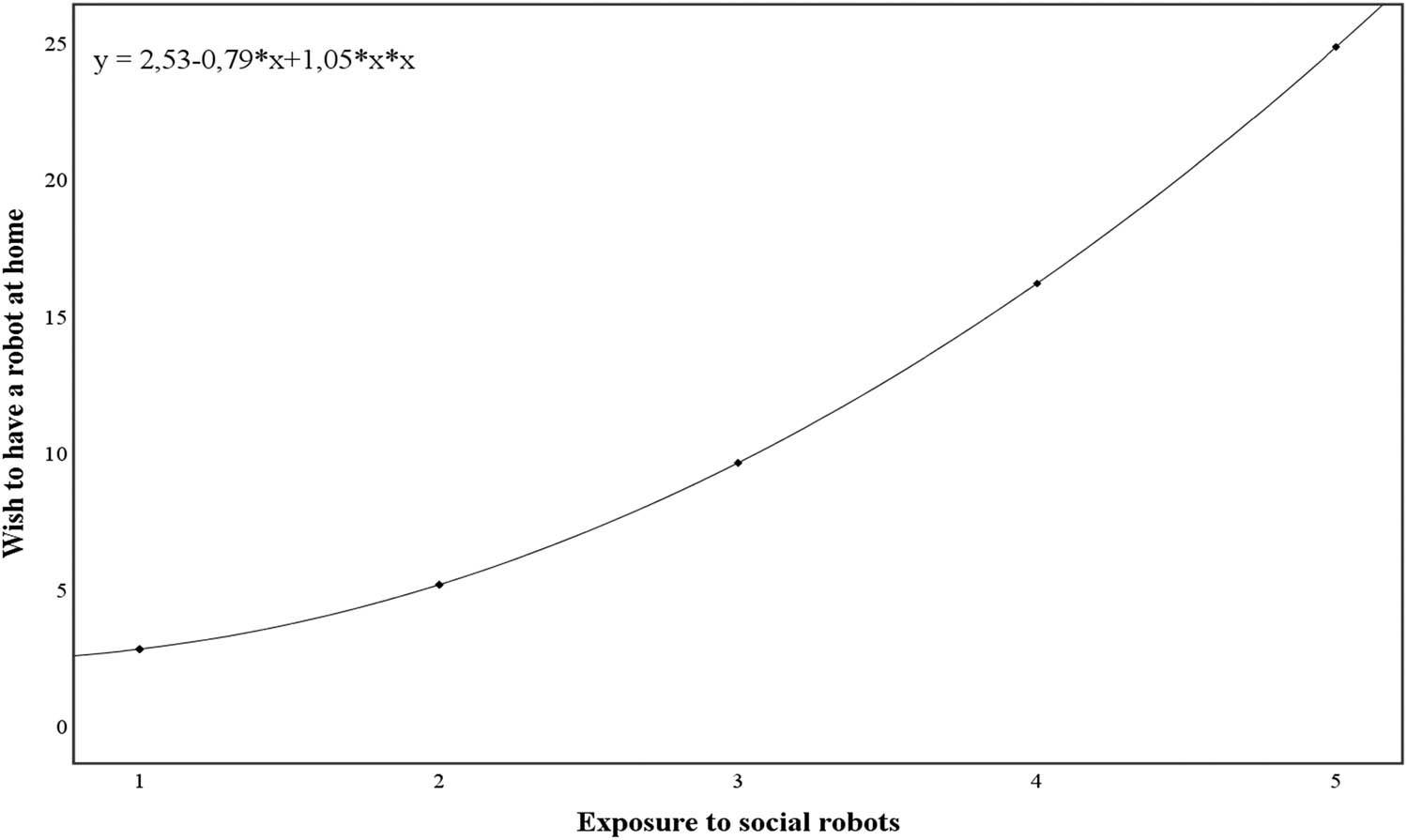

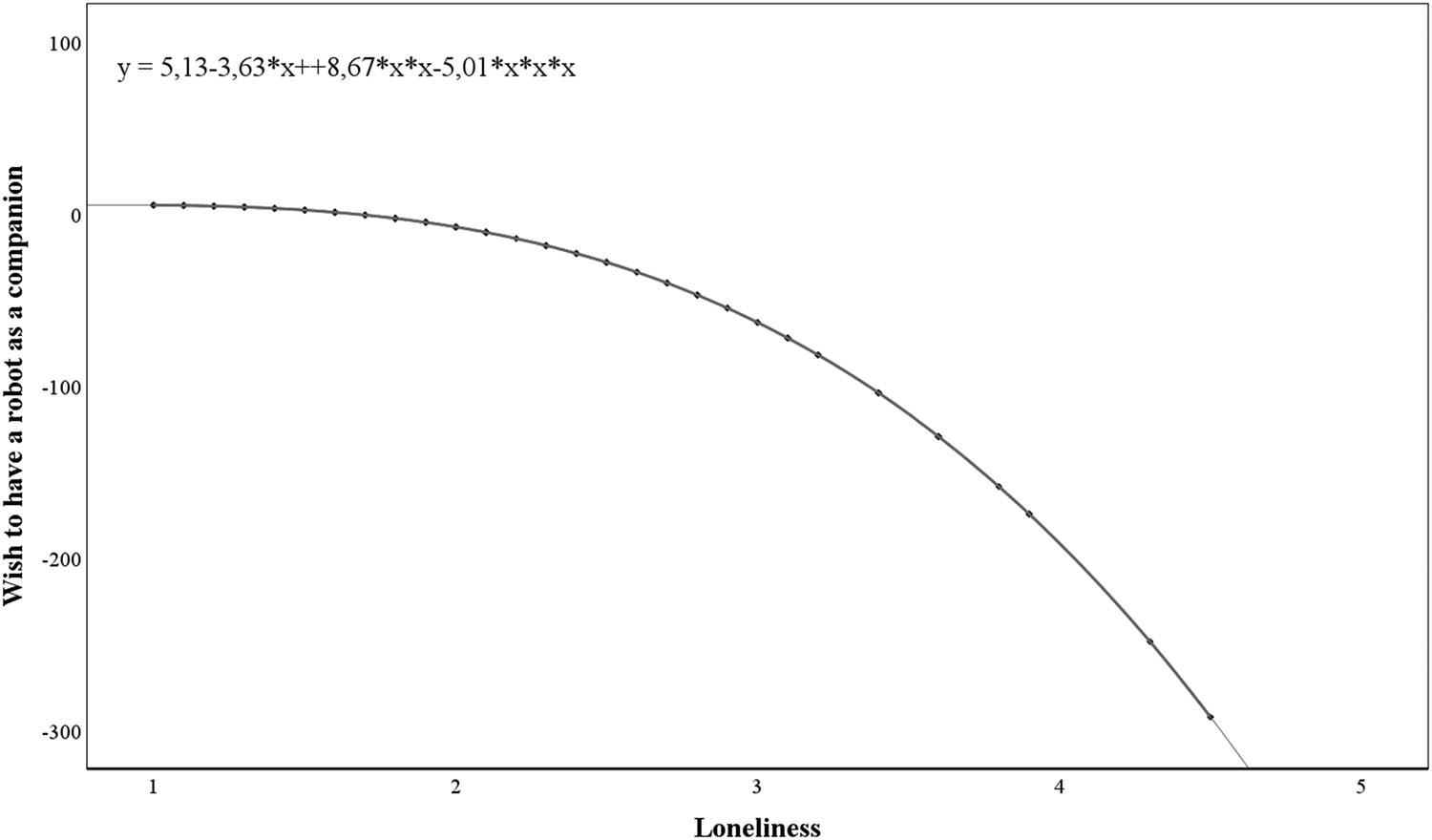

Linearity assumption check showed that the relationship between Exposure and Wish to have a robot at home is better explained by a square term of the Exposure variable (Figure 1), and the relationship between Loneliness (Intimate) and Wish to have a robot as a companion is better explained by the cubic term of the Loneliness variable (Figure 2).

Wish to have a robot at home explained by Exposure to social robots.

Wish to have a robot as a companion explained by Loneliness (Intimate).

Regression analyses support partially H1a, H1b, H4b, H4c, H5a, and H6 and contradict H2a and H2b. The relationship between Exposure to social robots and a Wish to have a robot at home is better explained by a square model (Figure 1). The relationship between Loneliness and a Wish to have a robot as a companion is explained by a cubic model (Figure 2). Moreover, we found that conscientiousness and agreeableness predict a Wish to have a robot at school and at other public places (EH1).

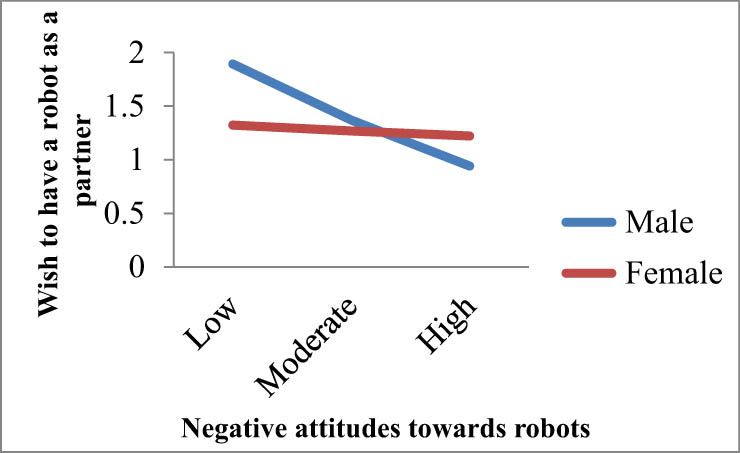

To test the hypothesis that participant gender moderates the relationship between NARS and a Wish to have a robot as a partner, a hierarchical multiple regression analysis using the PROCESS Macros [74] (Model 1) was conducted. Indeed, the relationship between NARS and Wish to have a robot as a partner was different for men and women (H3). Specifically, for men, as NARS increased, the Wish to have a robot as a partner decreased (B = −0.67, t(130) = −2.54, p < 0.05), whereas for women, the relationship between NARS and Wish to have a robot as a partner was not significant (B = −0.07, t(130) = −0.71, p = 0.478). In general, women were not inclined to see a social robot as their partner. The results of the moderation analysis are summarized in Table 9. Figure 3 illustrates the model.

Gender as moderator of the relationship between Negative attitudes toward robots and Wish to have a robot as a partner

| B | SE | T | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 3.51 | 0.83 | 4.26 | <0.001** |

| Negative attitudes toward robots | −0.67 | 0.26 | −2.54 | <0.05* |

| Gender (female) | −2.02 | 0.89 | −2.27 | <0.05* |

| Negative attitudes toward robots x Gender | 0.60 | 0.28 | 2.12 | <0.05* |

| R 2 = 0.059, MSE = 0.553 | ||||

| F(3,130) = 2.718, p < 0.05 | ||||

Note. Calculated with PROCESS Macro, Model 1 [74]. Gender is coded as dummy variable with values 0 = male, 1 = female.

Gender as moderator of the relationship between Negative attitudes toward robots and a Wish to have a robot as a partner. Gender is coded as dummy variable with values 0 = male, 1 = female. Note. The y-axis represents the average ratings on the item “Wish to have a robot as s partner.”

3.4 Robot’s roles and qualities EH4–EH5

Table 10 provides an overview about the Roles and tasks of a robot at home and in public places chosen by the participants (EH4). Most participants preferred to see either no robot at all or a robot as a helper and assistant. In these Roles, robots were suggested to be used for cleaning and cooking; only a few participants could imagine a robot as a friend or in an intimate relationship. Also, in public places, the most preferred choice of a task for the robot was cleaning followed by transportation. Only 19.3% of all participants could imagine a robot in childcare.

Robots’ roles and tasks at home and in public places

| Frequency | Percent (%) (N = 135) | |

|---|---|---|

| Robots’ roles at home | ||

| Helper | 67 | 49.6 |

| No robot at home | 63 | 46.7 |

| Assistant | 61 | 45.2 |

| Servant | 27 | 20.0 |

| Companion | 18 | 13.3 |

| Others | 10 | 7.4 |

| Friend | 8 | 5.9 |

| Partner | 1 | 0.7 |

| Robots’ tasks at home | ||

| Cleaning | 66 | 48.9 |

| Cooking | 56 | 41.5 |

| Shopping | 37 | 27.4 |

| Entertainment | 35 | 25.9 |

| Health | 33 | 24.4 |

| Childcare | 16 | 11.9 |

| Friendship | 5 | 3.7 |

| Intimate | 3 | 2.2 |

| Robots’ task in public places | ||

| Cleaning | 97 | 71.9 |

| Transportation | 87 | 64.4 |

| Health | 51 | 37.8 |

| Entertainment | 51 | 37.8 |

| Guidance | 45 | 33.3 |

| Shopping assistance | 40 | 29.6 |

| Childcare | 26 | 19.3 |

Note. Sorted by frequency. Participants could choose multiple categories.

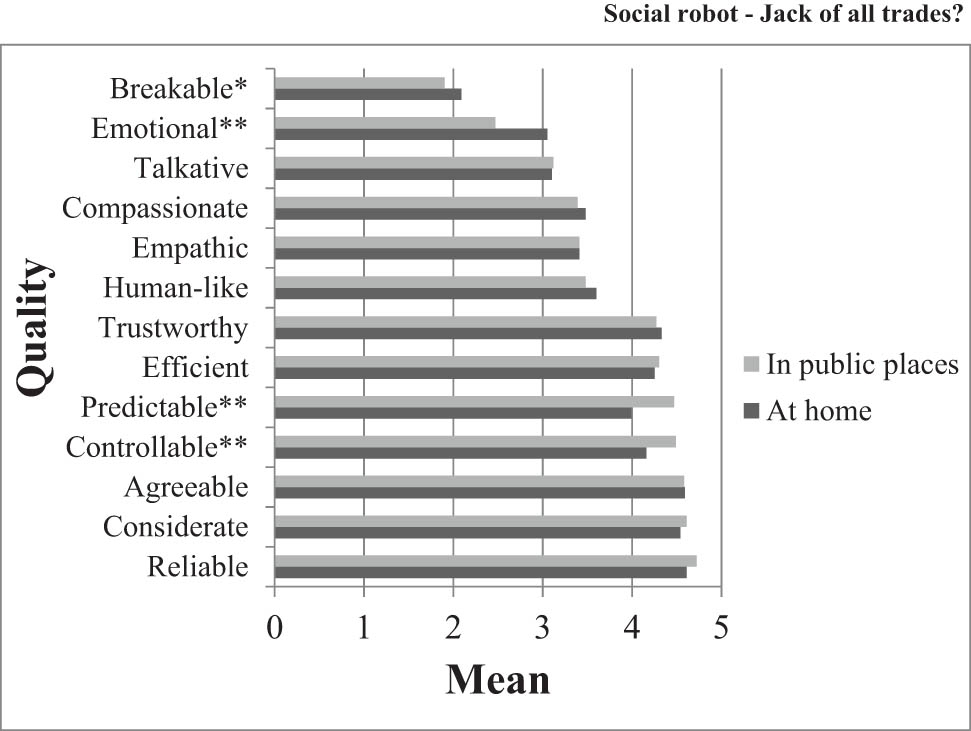

In a further question, participants were asked to evaluate different Qualities a robot at home and in a public place should have (EH5). Table 11 summarizes the descriptive statistics of these parameters, compared between a robot at home and in public places. Significant differences were found in only four Qualities. Both robots at home and robots in public places are expected to be extremely reliable, considerate, and agreeable, but moderately emotional, talkative, and companionate (Figure 4). In comparison to robots at home, robots in public places are desired to be more controllable (M h = 4.16, M p = 4.49) and predictable (M h = 3.99, M p = 4.47), but less breakable (M h = 2.09, M p = 1.90) and emotional (M h = 3.05, M p = 2.47).

Results of the Wilcoxon signed-rank test between characteristics of a robot at home and in public places

| Quality | At home | In public places | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Z-Score | Median | Mean | SD | Median | Mean | SD | |

| Controllable | −3.59** | 5.00 | 4.16 | 1.06 | 5.00 | 4.49 | 0.98 |

| Predictable | −4.63** | 4.00 | 3.99 | 1.18 | 5.00 | 4.47 | 0.87 |

| Considerate | −1.02 | 5.00 | 4.54 | 0.87 | 5.00 | 4.61 | 0.82 |

| Efficient | −1.19 | 5.00 | 4.25 | 1.15 | 5.00 | 4.30 | 1.29 |

| Human–like | −1.38 | 4.00 | 3.60 | 1.36 | 3.00 | 3.48 | 1.35 |

| Reliable | −1.87 | 5.00 | 4.61 | 0.86 | 5.00 | 4.72 | 0.73 |

| Agreeable | −0.10 | 5.00 | 4.59 | 0.84 | 5.00 | 4.58 | 0.82 |

| Trustworthy | −0.58 | 5.00 | 4.33 | 1.11 | 5.00 | 4.27 | 1.22 |

| Compassionate | −1.04 | 4.00 | 3.48 | 1.24 | 3.50 | 3.39 | 1.37 |

| Talkative | −0.29 | 3.00 | 3.10 | 1.25 | 3.00 | 3.12 | 1.34 |

| Breakable | −2.34* | 1.00 | 2.09 | 1.35 | 1.00 | 1.90 | 1.35 |

| Empathic | −1.57 | 4.00 | 3.41 | 1.42 | 4.00 | 3.41 | 1.42 |

| Emotional | −4.28** | 3.00 | 3.05 | 1.37 | 2.50 | 2.47 | 1.27 |

Note. *p < 0.05. **p < 0.001. Significant differences are marked in bold. Measured on a scale from 1 (Not at all) to 5 (To a great extent).

Robots’ qualities desired at home and in public places, measured on a scale from 1 (Not at all) to 5 (To a great extent).

4 Discussion

4.1 Human-related factors

4.1.1 NARS and RAS

Consistent to our expectations, NARS had a small positive association with a Wish to have no robot at home or in public places and small to moderate negative associations to having a robot at home, as a companion, a friend, a partner, or a sex partner. NARS also have a small to moderate negative association with Wish to see a robot at the counter, at school, in a hospital, and in other public places. Especially, the sub-factor of Negative attitudes toward emotional interactions with robots plays a role.

In its turn, Robot anxiety, especially its behavioral aspect (how the robot would move or act), is positively associated with a refusal to have a robot at all. It could conceivably be hypothesized that mitigating or even reversing the Negative attitudes to social robots and lowering Anxiety toward robots by propagating emotional interactions with them or providing more information about their possible behavior can possibly improve Acceptance of robots – both in public places and at home. In future investigations, it should be possible to use experimental designs to test these suggestions.

4.1.2 Personality and demographic factors

Only a few Personality traits and personal characteristics were linked to Wish to have a robot. Our results showed that Conscientiousness was negatively associated with Wish to have a robot at school and age was negatively associated with Wish to have a robot in a hospital. Probably, conscientious people do not trust robots to educate children, and older people do not want robots to substitute humans in a very care-sensitive environment like a hospital. This finding broadly supports the results of a previous study by Kaplan that found that participants’ Conscientiousness, Extroversion, and Neuroticism predicted robots’ anthropomorphization, thus implicitly predicting Acceptance [42]. Further, in this study [42], likability of robots was best predicted by the participant’s level of Intellect, Conscientiousness, Extroversion, and Agreeableness. In our study, however, Extraversion was not a significant predictor of robots’ acceptance.

In line with our expectations, gender moderated the negative relationship between the NARS and Wish to have a robot as a partner. For men, as the NARS increase, their Wish to have a robot as a partner decreases, whereas for women, there is no significant association between NARS and Wish to have a robot as a partner. In general, women are also less inclined than men to accept a social robot as their partner. This result should however be treated with caution because of the unbalanced sample (111 females vs 28 males vs 1 nonbinary).

In line with this finding is the fact that sex robots are mostly female [78]. This phenomenon can be accounted for by the fact that people are usually only familiar with the concept of female sex robots. So, in the USA and Japan, the design of humanoid robots is led by stereotypes (i.e., a bodyguard is male and a housekeeper is female) [79]. At the same time, a female body as such is stereotypically objectified, prostitution being mainly a female profession [80]. This taken together produces the trend of a female sex robot. Because of these longtime cultural tendencies, women are apparently more reluctant to imagine a robot as a sex partner.

As for searching no romantic partnership with a male robot, this might be partially explainable from an evolutionary perspective: Women rather prefer a lifelong partner with reproductive potential [81]. Apparently, this factor is genuinely absent in social robots. Future studies should dwell upon possible motives, such as emotional, social, or communicational, for choosing a robot as a partner in different genders.

Finally, as expected, participants with university education were rather supportive of having a robot.

In addition, in line with our expectations, the more participants were Exposed to social robots and were Interested in them, the more they were Willing to have a robot at home and in public places in most of the Roles. Again, because of the young age of our participants, it was only to expect that many of them were interested in robots or even had experiences with them.

4.1.3 Loneliness

First, we found that the lonelier a person currently feels, the more inclined he or she is to accept a social robot as a companion, a friend, a partner, and even as a sex partner. These results are intuitive, meaning that acutely lonely people tend to accept having a robot at home and see it as a companion and a friend. This finding also accords with earlier observations which showed that experimentally prompted Loneliness had a positive effect on anthropomorphization of a social robot and on the readiness to accept it [39,49]. On the other side, some studies demonstrated that emotional Loneliness and depressive mood can reduce acceptance of robots [49], with other important factors being usability and the specific qualities of a robot. Therefore, it may be desirable in the future to have an accessible offer of social robots for lonely people, not only in situations of forced isolation like the current pandemic or in remote areas [82].

This being said, it is important to note that in this study the state of Loneliness is being considered. In contrast to this, the trait of Loneliness, a constant feeling of being alone and having no significant other, was reported to reduce participants’ Acceptance of social robots [39]. Moreover, whereas the intimate and the social aspects of loneliness are associated with all four potential roles of the robot that were mentioned above, its affiliative aspect is not related to any of them. This last aspect implies a human desire to be part of a group, which indeed is difficult to overcome with a social robot alone and is eventually only possible in a truly human society. Future studies should attempt to disentangle different aspects of Loneliness as state vs trait and as distinct predictors of Robots’ acceptance.

Despite these promising results, questions remain. Even if lonely people accept robots more and hope to ease their Loneliness in this way, it is not clear how effective such an intervention can be. Although several studies suggest that social robots can be successfully applied for reducing Loneliness in elderly people [44,83], little is known about whether they are equally effective in mitigating Loneliness in people of different, in particular, younger ages. Although there has been recent evidence that social robots could lessen both emotional and social Loneliness [84], there is still abundant room for further investigations.

4.1.4 Need to belong

An unanticipated finding was that the Need to belong was negatively linked to Wish to have a robot as a partner. In this interpretation, Need to belong can be an opposite pole to Loneliness on the continuum, as traditionally assumed. This is in line with the finding concerning the Affiliative aspect of Loneliness. A possible explanation for this finding might be that a person wants to belong to and be accepted by other humans, not by a social robot as a partner. This fundamental need to be a part of a group can only be satisfied within human society, not by artificial agents. Moreover, as the Dual Continuum Model of Belonging and loneliness by Lim et al. [54] predicts, Loneliness can also exist within a specific context (e.g., in the family, while Belonging is high) and is not explained by just being alone. Therefore, it is important to bear in mind that on the one hand offering social robots indeed could be a remedy for Loneliness, especially in the circumstances of isolation, be that a pandemic, a hospital, an elderly home, or remote places such as a north pole research station or a Mars mission. Nevertheless, social robots will not be able to completely satisfy the fundamental human Need to belong to a society.

Finally, Willingness to see a robot in various public places (counter, school, hospital, other public places) was linked neither to Loneliness, nor to Need to belong. Apparently other factors, presumably more utilitarian ones, influence Acceptance of social robots in public places.

4.2 Contextual factor lockdown

As for the specific characteristics of the pandemic situation, we found that the longer a Lockdown in the part of the country was, the more inclined the participants were to have a robot as their sex partner. However, this relationship was not mediated by Loneliness.

4.3 Dependent variables

4.3.1 Wish to have a robot at home and as companion

Regression analyses revealed that the Wish to have a robot at home was best predicted by the Emotional interaction sub-factor of NARS and by Exposure to social robots. Participants’ Wish to have a robot as companion was only predicted by the Intimate others sub-factor of Loneliness, whereas it also predicted Wish to have a robot as friend and as a sex partner, together with the Emotional interaction sub-factor of NARS. Finally, Wish to see a robot as a partner was predicted by the Affiliative environment sub-factor of Loneliness. Thus, loneliness and attitudes to emotional interactions with robots are important factors for acceptance of a robot at home.

The more exposed to robots the participants were, the more they wished to see a robot at home. The lonelier our participants were, the more they wished to accept a robot as a companion, especially at higher levels of Loneliness.

4.3.2 Wish to see robots in public places

As for having a robot in different public places, such factors as Lockdown, Openness, Conscientiousness, Agreeableness, NARS (Interaction and Emotional interaction), Exposure to and Interest in social robots, age, gender, and again, the Intimate others aspect of Loneliness predicted them best in different combinations. When introducing social robots in public places, Personality traits, age, and gender of potential users should be considered. So, older participants are less in favor of seeing a robot at hospital, whereas women are more inclined to have robots in public places.

The Intimate others aspect of Loneliness was a negative predictor of having no robot, whereas Negative attitudes to interaction with robots was a positive predictor. The lonelier the participants were, the more they accepted a robot, and the more negative their attitudes to possible interaction with social robots were, the less inclined they were to have a robot. Further research should determine whether positive experiences of interactions with robots can clear out Negative attitudes toward them and promote better acceptance.

Finally, there was no significant difference in preferred Distance to a robot and Time spent with a robot at home and in public places. Participants preferred a middle Distance (not too close and not far away) in both cases.

4.3.3 Opinions: Where to apply social robots?

Our participants’ opinions about a possible Role of a robot were as follows: Most participants preferred to see either no robot at all or a robot as a helper and assistant for cleaning and cooking. Only a few participants could imagine a robot as a friend or in an intimate relationship. In public places, the most preferred option was cleaning followed by transportation and health. The least preferred option here was childcare. Apparently, social robots are perceived rather as devices used for such household duties as cooking and cleaning.

In the comparison between characteristics of a robot at home and in public places, significant differences were found in only four of them. Both robots at home and in public places were expected to be extremely reliable, considerate, and agreeable, but only moderately emotional, talkative, and companionate. In contrast to robots at home, robots in public places were to be more controllable and predictable, but less breakable and emotional. As the results show, reliability and agreeableness are the most valued attitudes of social robots. These features are also valued in household devices.

These findings are in line with the results reported in earlier studies. In the study by Dautenhahn and colleagues [72], most subjects saw a robot at home as an assistant, machine, or servant. Several accepted it as a friend. Ninety percent of the participants also stated they would prefer a robot to do the vacuuming, and only 10% wanted the robot to assist with childcare. They also wanted a robot companion to be predictable, controllable, considerable, and polite. Ezer et al. [73] and Nomura et al. [61] also reported that robots were rather seen as helpful, reliable, and purposeful devices. Future research should determine a possible link between these qualities and Acceptance of robots in a different Role at home and public places.

5 Conclusions and outlook

This study was conceived during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in the circumstances of extreme social isolation and lockdown. It gained several insights into relationships between Loneliness, Need to belong, Personality variables, and robot-related Attitudes on the one hand and Acceptance of robots on the other. We found that Personality and demographic characteristics of participants, as well as attitudes to robots and Loneliness, played an important role in Robots’ acceptance. Contextual factors such as Lockdown also contributed to that.

5.1 Limitations of the present study

Our findings should doubtlessly be scrutinized in future studies to overcome the limitations of the present study. First, the present study was of a correlative nature, which is unsuitable for producing causal conclusions. Further experimental studies are needed to manipulate different robot-related factors, such as emotional interaction or voice [85]. Second, the limited number of participants and the homogeneity of the sample regarding nationality, education, cultural background, and age do not allow generalization of the present results. Most of the participants were of younger age, enjoyed university education, and came from Germany or other European countries. Further, more representative studies are needed to compare the acceptance of social robots in different, not only European societies. Third, there were more female participants than male ones, which makes it difficult to generalize the gender-related results. Fourth, this study did not involve any real-life interaction with a robot and was purely cross-sectional. However, a recent meta-analysis [86] showed that whether participants had interacted with physical robots or merely seen their photos had no influence on a wide range of measures. Fifth, the present study was conducted in an unusual period of social distancing, which prevents us from generalizing results to all situations. Multiple other related factors such as stress or depression might have influenced our results. Last but not least, only some equivocal, general, notion of social robots was referred to, without any actual live interaction with a specific robot, which could deliver a different picture. Experimental, eventually longitudinal field studies with different robots will be useful and shed more light on real-life human–robot interactions.

5.2 Robots as a third social category

Humans tend to assign human traits to other, nonhuman beings, mostly to their pets. The main objective difference between pets and robots is that pets are alive and are not machines: They have physical needs such as hunger, thirst, and even seek the attention of their owner. This difference, however, can disappear in specific cultural contexts, for example, in Japan, where due to Shinto, the native animistic beliefs about life and death, robots are perceived as living beings [87].

In the European culture, to which our participants belong, robots are not believed to have needs. They might imitate them by using natural learning algorithms and, for example, like Paro [88], repeat behaviors leading to being stroked. But, strictly speaking, these are not their real needs, they can go without this. They only serve their humans without asking for attention, food, or drinks. Of course, pet robots exist that pretend to have needs as well, e.g., MarsCat.[2] Still, human owners know that robots do not emotionally or physically need them as a real other human beings do. One can argue that on these grounds, humans will never develop as much empathy for robots as they have for other humans or for animals because of the knowledge that robots are still machines. Even if the owner is able to ignore the fact that a social robot is a machine, it is questionable whether or not subconscious knowledge would prevent the human from having a feeling of belonging to the robot.

Thus, robots might open a third social category in addition to humans and pets – at least in some cultural contexts. So, there is no wonder that Need to belong cannot be compensated by a social robot – because it is not human – in our results with mostly European participants. Figuratively speaking, despite all the hopes, social robots are hardly masters of all the trades offered. Thus, when creating social robots for remote places or other venues with the aim to mitigate Loneliness, one should bear in mind that there are some genuinely human functions, such as being a part of a group, that cannot be substituted by robots. Future research, preferably using experimental methods, should study aspects of Loneliness as state and trait as predictors of Robots’ acceptance.

-

Funding information: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

-

Author contributions: KK and YZ contributed to the conception and design of the study. KK conceived the stimuli, programmed the survey, and conducted the study. KK performed the analysis. YZ, MAJM, and MHF contributed to the analyses. KK wrote the first draft of the manuscript. KK, MAM, YZ, and MHF wrote, discussed, and revised several drafts before approving the final version.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

-

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individuals included in this study.

-

Ethical approval: The study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Potsdam, Germany (approval number 25/2020). The participants provided their online informed consent to participate in this study.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets and stimuli of this study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

References

[1] S. Chen, C. Jones, and W. Moyle, “Social robots for depression in older adults: a systematic review,” J. Nurs. Scholarsh., vol. 50, no. 6, pp. 612–622, 2018 Nov.10.1111/jnu.12423Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[2] J. Murphy, C. Hofacker, and U. Gretzel, “Dawning of the age of robots in hospitality and tourism: challenges for teaching and research,” Eur. J. Tour. Res., vol. 15, pp. 104–111, 2017 Mar 1.10.54055/ejtr.v15i.265Search in Google Scholar

[3] L. Royakkers and R. van Est, “A literature review on new robotics: automation from love to war,” Int. J. Soc. Robot., vol. 7, no. 5, pp. 549–570, 2015 Nov.10.1007/s12369-015-0295-xSearch in Google Scholar

[4] A. M. Sabelli and T. Kanda, “Robovie as a mascot: a qualitative study for long-term presence of robots in a shopping mall,” Int. J. Soc. Robot., vol. 8, no. 2, pp. 211–221, 2016 Apr.10.1007/s12369-015-0332-9Search in Google Scholar

[5] C. Bartneck and J. Forlizzi, “A design-centred framework for social human-robot interaction,” in: RO-MAN 2004 13th IEEE International Workshop on Robot and Human Interactive Communication (IEEE Catalog No04TH8759), Kurashiki, Okayama, Japan, IEEE, 2004 [cited 2022 Mar 1], pp. 591–594. http://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/1374827/.10.1109/ROMAN.2004.1374827Search in Google Scholar

[6] E. Broadbent, “Interactions with robots: the truths we reveal about ourselves,” Annu. Rev. Psychol., vol. 68, no. 1, pp. 627–652, 2017 Jan 3.10.1146/annurev-psych-010416-043958Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[7] P. Ferrarelli, T. Lapucci, and L. Iocchi, “Methodology and results on teaching maths using mobile robots”, in: ROBOT 2017: Third Iberian Robotics Conference, Eds., A. Ollero, A. Sanfeliu, L. Montano, N. Lau, and C. Cardeira, vol. 694, Cham, Springer International Publishing, 2018 [cited 2022 Mar 1], pp. 394–406. http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-319-70836-2_33.10.1007/978-3-319-70836-2_33Search in Google Scholar

[8] C. Lytridis, C. Bazinas, G. Sidiropoulos, G. A. Papakostas, V. G. Kaburlasos, V.-A. Nikopoulou, et al., “Distance special education delivery by social robots,” Electronics, vol. 9, no. 6, p. 1034, 2020 Jun 23.10.3390/electronics9061034Search in Google Scholar

[9] F. Tanaka, A. Cicourel, and J. R. Movellan, “Socialization between toddlers and robots at an early childhood education center,” Proc. Natl Acad. Sci., vol. 104, no. 46, pp. 17954–17958, 2007 Nov 13.10.1073/pnas.0707769104Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[10] M. Pollack, L. Brown, D. Colbry, C. Orosz, B. Peintner, S. Ramakrishnan, et al., Pearl: a mobile robotic assistant for the elderly. undefined, 2002 [cited 2022 Mar 1]. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Pearl%3A-A-Mobile-Robotic-Assistant-for-the-Elderly-Pollack-Brown/1bc1535414684083ecef597f704bb069a6b6f38f.Search in Google Scholar

[11] A. Sharkey and N. Sharkey, “Granny and the robots: ethical issues in robot care for the elderly,” Ethics Inf. Technol., vol. 14, no. 1, pp. 27–40, 2012 Mar.10.1007/s10676-010-9234-6Search in Google Scholar

[12] H. M. Shim, E.-H. Lee, J.-H. Shim, S.-M. Lee, and H. Seung-Hong, “Implementation of an intelligent walking assistant Robot for the elderly in outdoor environment,” 9th International Conference on Rehabilitation Robotics, 2005 ICORR 2005 [Internet], Chicago, IL, USA, IEEE, 2005 [cited 2022 Mar 1], pp. 452–455. http://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/1501140/.Search in Google Scholar

[13] C. A. Cifuentes, M. J. Pinto, N. Céspedes, and M. Múnera, “Social robots in therapy and care,” Curr. Robot. Rep., vol. 1, no. 3, pp. 59–74, 2020 Sep.10.1007/s43154-020-00009-2Search in Google Scholar

[14] A. D. Cheok and E. Y. Zhang, Human-Robot Intimate Relationships, 1st ed., Cham, Springer International Publishing, Imprint, Springer, 2019, p. 1. (Human-Computer Interaction Series).10.1007/978-3-319-94730-3Search in Google Scholar

[15] C. S. González-González, R. M. Gil-Iranzo, and P. Paderewski-Rodríguez, “Human–robot interaction and sexbots: a systematic literature review,” Sensors, vol. 21, no. 1, p. 216, 2020 Dec 31.10.3390/s21010216Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[16] O. Bendel, Hologram Girl, Ai Love You, Cham, Springer, pp. 149–165, 2019.10.1007/978-3-030-19734-6_8Search in Google Scholar

[17] D. N. L. Levy, Love + Sex with Robots: The Evolution of Human-Robot Relations, 1st ed., New York, HarperCollins, 2007, p. 334.Search in Google Scholar

[18] Y. Zhou and M. H. Fischer, “Intimate relationships with humanoid robots: exploring human sexuality in the twenty-first century,” AI Love You [Internet], Y. Zhou and M. H. Fischer, Eds., Cham, Springer International Publishing, 2019 [cited 2022 Mar 1], pp. 177–184. http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-030-19734-6_10.10.1007/978-3-030-19734-6_10Search in Google Scholar

[19] C. Edirisinghe, A. D. Cheok, and N. Khougali, “Perceptions and responsiveness to intimacy with robots; a user evaluation,” A. D. Cheok and D. Levy, Eds., Love and Sex with Robots, vol. 10715, Cham, Springer International Publishing, 2018 [cited 2022 Mar 2], pp. 138–157. http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-319-76369-9_11.10.1007/978-3-319-76369-9_11Search in Google Scholar

[20] T. Nomura, T. Kanda, T. Suzuki, and K. Kato, “Prediction of human behavior in human--robot interaction using psychological scales for anxiety and negative attitudes toward robots,” IEEE Trans. Robot., vol. 24, no. 2, pp. 442–451, 2008 Apr.10.1109/TRO.2007.914004Search in Google Scholar

[21] L. Bishop, A. van Maris, S. Dogramadzi, and N. Zook, “Social robots: The influence of human and robot characteristics on acceptance,” Paladyn J. Behav. Robot., vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 346–358, 2019 Oct 16.10.1515/pjbr-2019-0028Search in Google Scholar

[22] D. Kang, S. Kim, and S. S. Kwak, “The effects of the physical contact in the functional intimate distance on user’s acceptance toward robots,” Companion of the 2018 ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction, Chicago IL USA, ACM, 2018 [cited 2022 Mar 1], pp. 143–144. https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/3173386.3177023.10.1145/3173386.3177023Search in Google Scholar

[23] T. Nomura, “Robots and gender,” Gend. Genome, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 18–26, 2017 Mar.10.1016/B978-0-12-803506-1.00042-5Search in Google Scholar

[24] S. Naneva, M. Sarda Gou, T. L. Webb, and T. J. Prescott, “A systematic review of attitudes, anxiety, acceptance, and trust towards social robots,” Int. J. Soc. Robot., vol. 12, no. 6, pp. 1179–1201, 2020 Dec.10.1007/s12369-020-00659-4Search in Google Scholar