Spanish phraseology in formal and informal spontaneous oral language production

-

Enrique Gutiérrez Rubio

Abstract

The study presented in this paper aims to perform a comprehensive analysis of the use of phraseological units (PUs) in contemporary Spanish according to two different levels of oral language production: (a) spontaneous informal (on the basis of conversations uttered among the contestants of the Spanish version of the reality show Big Brother), (b) spontaneous formal (on the basis of interviews performed on Spanish radio and TV programmes). The configuration of Spanish phraseology as it is used in formal and informal spontaneous oral language production will be investigated according to four variables: frequency distribution, typological distribution, stylistic distribution, and individual distribution. It will be shown that a) the more informal the discourse context, the higher the frequency of use of PUs, b) that idioms (and not routine formulae or proverbs) are clearly dominant in both formal and informal oral contexts, c) that there are speakers in formal discourse contexts who often utter informal PUs, d) that vulgar vs. non-vulgar PUs – and not so much informal vs. non-informal PUs – is the main disagreement between formal and informal spontaneous oral contexts, and e) that using vulgar PUs more or less frequently would be a highly individual issue.

1 Spontaneous oral language, linguistic corpora, and Big Brother

In recent decades, linguistic corpora have become a key tool for investigating linguistics in general and phraseology in particular. However, in the field of phraseology most of the studies carried out so far focus on text corpora (see, for instance, Moon 1997, Moon 1998; Arnaud et al. 2008) and not on oral corpora. Probably one of the reasons for this phenomenon is that oral corpora are generally too small or still insufficiently reliable. In addition to this, in oral language production speakers very often make use of variations or reduced versions of phraseological units (PUs). So, if using computer programs for finding PUs in a corpus automatically or even semi-automatically in written corpora causes serious difficulties for the efficient excerption of PUs – as has been admitted by Kováříková and Kopřivová (2014: 523) – this issue becomes considerably more problematic when dealing with oral corpora. Moreover, analyses that intend to shed light on the configuration of phraseology, especially in terms of frequency of use, are usually based on a closed list of PUs, mainly obtained from the phraseological dictionaries that are available. This is another problematic question, since many phraseological neologisms that have become widespread among speakers in recent years – in some cases decades – are not included even in the most recent glossaries. In this sense, it is important to note that the most up-to-date Spanish phraseological dictionary, by Seco et al. (2017), collects exclusively PUs documented in written corpora. Probably because of these methodological issues, all three Spanish scholars who have worked intensively on “colloquial” phraseology have excerpted the PUs manually (Ruiz Gurillo 1998; Penadés Martínez 2004, Penadés Martínez 2012, Penadés Martínez 2015b; Sosiński 2010, Sosiński 2011). This approach logically increases the reliability of the data obtained, but drastically reduces the number of PUs on which linguists can work. For the same reasons, the PUs in the study presented in this paper were also excerpted manually.

As mentioned above, most of the available oral corpora of Spanish are not sufficiently reliable for the purpose of investigating phraseology in spontaneous oral language production, at least for the informal variety of Spanish. This would be the case of the most extensive oral corpus of Spanish, the present-day Spanish language CREA oral 3.2 by Real Academia de la Lengua Española (the Royal Spanish Academy). It consists of almost nine million words from more than 1600 sources belonging to a wide range of oral linguistic material including, among others, political speeches, phone conversations, messages on answering machines, and informal dialogues.[1] Given its lack of consistency, it cannot be reliably used as a whole. However, CREA oral allows us to look for PUs in a subcorpus explicitly shaped for investigating some specific kind of oral production. According to this, a subcorpus of 10,000 words recorded (and later transcribed) from interviews carried out on Spanish radio and TV programmes has been created. Since this analysis focuses exclusively on spontaneous language production, only the responses of the interviewees and not the interventions of the interviewers are included in this CREA oral subcorpus. Given the contexts in which the conversations were recorded, this material is an appropriate source for analysing formal spontaneous language production. At the opposite pole of oral production, conversations uttered in highly informal discourse contexts must be found. In this sense, they should fulfil as much as possible the four main “colloquialiser” features proposed by Briz (2010b), i.e. a relationship of equality among the speakers, experience-based correlation, an everyday interaction frame, and quotidian topics. In my opinion, all these features are ideally fulfilled by the contestants of the reality show Gran Hermano, the Spanish version of Big Brother, because of the shared situation of the “captives” in the house. That is the main reason why I opted for the conversations uttered in this contest as the basis of my multidimensional project[2] devoted to the analysis of Spanish phraseology used in informal spontaneous language production, of which the present paper is just a part. Therefore, I created my own Spanish Big Brother corpus, which consists of 30,041 lexical units.[3]

The question arises as to why to use conversations from Gran hermano instead of other (already transcribed) Spanish oral corpora that, unlike CREA oral, recollect conversations uttered in informal discourse contexts, such as, for instance, Val.Es.Co. (Valencia, Español Coloquial, developed at the University of Valencia)[4] or COLA (Corpus Oral de Lenguaje Adolescente, developed at the University of Bergen, Norway).[5] The main motive is that, for the specific purposes of my research, it is highly relevant to be absolutely certain that the speakers were recorded under the same circumstances. Moreover, the format of this contest allows me to investigate how the speakers behave linguistically in different situations or when talking with different persons. In addition to this, in existing oral corpora of Spanish the number of words uttered by every speaker is already established and usually most of them just register a few hundred words, which is not enough for a comprehensive individual analysis. Finally, since the contestants of Big Brother are public figures, it is possible to have access to interesting information about them that is unreachable for the users of the existing oral corpora, such as their sexual orientation, a key factor for the gender-oriented research included in my multidimensional analysis of Spanish phraseology in spontaneous informal language.

Undoubtedly, when considering the pros and cons of Big Brother as a source of oral linguistic material, it must be admitted, on the one hand, that it is a reality show and that, logically, it merely “simulates situations”. In consequence, we cannot be dealing here with 100% natural linguistic expressions. On the other hand, Dovey states that, as a material practice, this kind of simulation “[…] produces real knowledge about real things in the real world and has real effects upon real lives” (Dovey 2004: 233). In fact, this is not the first time that Big Brother has been employed for the purpose of linguistic analysis, with even a linguistic corpus based on the Norwegian version of this reality show existing.[6] Besides, Valeria Sinkeviciute (2017a, 2017b) is probably the specialist who has devoted her studies to Big Brother most intensively from a linguistic point of view, including one paper, in collaboration with Michael Haugh, on Spanish, specifically on conversations excerpted from the Spanish and Argentinian versions of this contest (Haugh and Sinkeviciute 2018).

One of the arguments that could be used against using Big Brother as a reliable source of spontaneous linguistic material is that the contestants cannot behave (linguistically) naturally since they are perfectly aware of the fact that they are wearing microphones and that there are dozens of cameras constantly monitoring them. However, Penadés Martínez (2004: 2227) confirms that, in the interviews and conversations – registered with a voice recorder in sight – from the PRESEEA corpus that she analysed, the degree of “formality” of the speech tended clearly to decrease at the end of the recordings, which lasted approximately 45–60 minutes. In accordance with this, it seems acceptable to proceed from the hypothesis that, after being recorded and broadcast live 24/7 for several weeks, the participants in Big Brother could probably behave linguistically almost as if they were not being recorded. According to all this, it seems very plausible that the conversations of Big Brother that form the corpus – recorded in the second half of November 2015, i.e. after more than two months of cohabitation in the house in conditions that were highly conducive to “colloquialisation” – are much more natural than any other dialogues performed in front of a voice recorder, as in the case of the COLA corpus, and even that these conversations among the contestants are as natural as those dialogues recorded secretly, which is the way 90% of the material comprising the Val.Es.Co. corpus was gathered.[7] This would also speak for a certain lack of consistency, since about 10% of the conversations was registered with a voice recorder in sight. On the contrary, in Big Brother all the participants, without exception, are aware that their words are being broadcast.[8]

2 Methodology of the analysis

2.1 Gran Hermano and CREA oral 3.2 (sub-)corpora

For this study a corpus that contains exactly 30,041 words obtained from randomly recorded fragments of the reality contest Gran Hermano broadcast in Spain by the private television station Tele 5 was analysed. These fragments belong to the 65th, 67th, and 76th days of the 16th season, which was broadcast live 24/7 via online streaming between September and December 2015. Besides, in order to avoid, as far as possible, the influence of the intervention of the TV production, only fragments from the 24-hour online streaming of Gran Hermano have been analysed, including exclusively conversations among the participants. In the moment when the fragments were recorded, from the original eighteen contestants only ten remained in the house, specifically four women and six men. Although the number of words of the speakers in the corpus is very unequal, every one of them has at least 1500 words (see Tab. 1). Moreover, their average age was 22.9 years and they could be classified as middle- to upper-middle-class, as illustrated by the fact that three of the contestants (Han, Sofía, and Marta) were pursuing higher education at the time they participated in the show. The fragments were not fully transcribed; only the PUs were excerpted after several viewings of the fragments that were analysed. Finally, the number of words uttered by every speaker was counted, so that the frequency of PUs per word could be calculated.

Characteristics of the speakers in the Gran Hermano corpus

Speaker |

Sex |

Profession |

Number of words |

Marta Peñate |

Female |

College student |

2769 |

Niedziela Raluy |

Female |

Circus performer |

4826 |

Marina Landaluce |

Female |

Secretary |

2556 |

Sofía Suescun |

Female |

College student |

2552 |

Han Wang |

Male |

College student |

2677 |

Ricky Natalicchio |

Male |

Student |

1739 |

Carlos Rengel |

Male |

Hotel manager |

5617 |

Aritz Castro |

Male |

Artisan/tour guide |

3505 |

Suso Álvarez |

Male |

Sales manager |

2278 |

Daniel Vera |

Male |

Fast food cashier |

1522 |

On the other hand, the subcorpus of the a priori formal spontaneous spoken language includes 10,000 words obtained from eleven interviews with two female and nine male speakers broadcast on Spanish TV and radio between 1990 and 1996. There is a wide range of profiles, from politicians or artists to businessmen or “normal people”, i.e. persons who are not used to speaking in public. Finally, every speaker in the CREA subcorpus has between 585 and 1089 words (see Tab. 2).

Characteristics of the speakers in the CREA oral subcorpus

Speaker |

Sex |

Profession |

Number of words |

Amparo Muñoz |

Female |

Actress/model |

1037 |

Marta Solé |

Female |

Hospitality manager |

817 |

Peret |

Male |

Musician |

1017 |

Ramón |

Male |

Former priest |

941 |

José María Aznar |

Male |

Prime minister |

1089 |

Agustín Jorge Giner |

Male |

Businessman |

585 |

Luis Zarraluqui |

Male |

Lawyer |

825 |

Josep Miquel Abad |

Male |

CEO OG Barcelona 92 |

1068 |

Cecilio Cardona |

Male |

Coffin manufacturer |

739 |

Ceferino Moreno Sandoval |

Male |

Painter |

959 |

Miguel Durán |

Male |

General manager |

923 |

2.2 Taxonomy of Spanish phraseology

One of the main issues faced by specialists in phraseology is that it is rather exceptional to find two scholars who, even within the same linguistic approach or national tradition, make use of the same phraseological taxonomy and terminology. After the evaluation of many existing taxonomies in the Spanish tradition, three basic categories of PUs are proposed for this research.

Idioms (“locuciones” in Spanish). Although the boundaries of this group are not absolutely defined, in the sense proposed in this research an idiom would be a unit “[…] that is fixed and semantically opaque or metaphorical, or, traditionally, ‘not the sum of its parts’, for example, kick the bucket or spill the beans” (Moon 1998: 4). Idioms such as partirse de risa[9] (‘to crack up’) are generally considered the most salient type of PUs and the only one which most researchers agree on. Moreover, only expressions denoting additional naming are accepted (see Dobrovol’skij and Piirainen 2005: 18). Idioms are further divided into seven subtypes according to their function in the sentence: adjectival phrases, adverbial phrases, conjunctive phrases, discourse marker phrases, nominal phrases, prepositional phrases, and verbal phrases.

Routine formulae (also known as pragmatic phrasemes), i.e. a heterogeneous group of multi-word expressions frequently used for pragmatic purposes such as ¡madre mía! (‘oh my!’) or ¿sabes lo que te quiero decir? (‘you know what I mean?’). Unlike idioms, PUs of this sort are independent speech acts, expressing a complete thought. In the manner of the idioms, routine formulae can also be divided into subtypes. Since they are independent speech acts, the classification does not respond to their function in the sentence, but to the kind of interaction established between the speakers, i.e. to pragmatic-discursive criteria (see López Simó 2016: 178–226): interpersonal-relation formulae, personal formulae, impersonal formulae, and metainteractive formulae.

Proverbs (including sayings and quotes), i.e. an independent maxim with a deontic function such as Spanish “piensa el ladrón que todos son de su condición” (‘knaves imagine nothing can be done without knavery’).

3 Results of the analysis

3.1 Frequency distribution

One of the major aims of this research on phraseology as it is used in spontaneous communicative situations is to shed light on the frequency of its use, and this is for two main reasons: on the one hand, because this is a question often commented on in studies on phraseology and colloquial register, but that has rarely been the object of systematic investigation, and on the other hand, to attempt to give a response to the question of the extent to which phraseology is a typical feature of colloquial registers, as has been suggested by some specialists (see Čermák et al. 2009: 9).

In total, 1501 occurrences and 550 different PUs (types) were documented in the 30,041 lexical units of the Gran Hermano corpus.[10] Logically, many PUs appear more than once in the conversations (2.7 times on average). As might be expected, the two most frequent PUs are two discourse marker phrases frequently used as pet phrases – o sea (approximately ‘I mean’) 69 times and es que (a neutral expression that could be (with difficulty) translated into English as ‘the thing is…’, ‘well…’, or even ‘it’s just that…’) 113 times.[11] Moreover, since 1501 occurrences were documented in a corpus of 30,041 words, on average one PU is used every 20.0 words. In addition, 550 types (i.e. different PUs) were identified, which means that a different type is used every 54.6 words.

The data extracted from the CREA oral subcorpus representing formal oral Spanish shows that one occurrence is used every 28.8 words (347 occurrences in a total of 10,000 lexical units);[12] in other words, the frequency of use (in terms of occurrences) in Gran Hermano is approximately 30% higher than in the formal subcorpus.[13] This would speak for a tendency, according to which the more informal the discourse context, the higher the frequency of use of PUs. This hypothesis could be partially confirmed by the only study (at least in Spanish) to have previously investigated the general frequency of phraseological use on the basis of an oral corpus. Marcin Sosiński (2010, 2011) documented 2816 occurrences in his analysis of the interviews and dialogues that form the PRESEEA GRANADA corpus – one of the PRESEEA corpora, composed of 82,141 lexical units – i.e. one occurrence every 29.2 words. Since the corpora of the PRESEEA project vary in a range between “formal” and “semi-formal” (see Penadés Martínez 2015b: 252), a frequency higher than 20 words per occurrence (Gran Hermano) and lower than 29 words per occurrence (CREA oral) would be expected.[14] According to the data obtained, phraseology is almost equally frequent in both (semi-)formal corpora, which is not exactly what was expected, since the PRESEEA corpora are supposed to be slightly less formal than the CREA oral subcorpus, but neither is it very surprising. In this sense, it has to be admitted that the comparison between my data and that proposed by Sosiński should be taken with precaution. Although the methodology used by Sosiński for his study is apparently very similar to the one used in my analysis (see Sosiński 2010: 138–140), when the time comes to decide whether a combination of words is or is not a PU, significant differences can be observed. According to the examples presented in his papers, this would probably not affect the most salient subtypes of PUs, such as verbal phrases (2011: 124), but it could be a key factor regarding other less salient subtypes, such as conjunctive and discourse marker phrases, and especially all kinds of routine formulae (routine phrases in his taxonomy). Moreover, Sosiński (2010: 143–144), in contrast with the methodological principles of my study, seems not to respect the additional naming criterium proposed by Dobrovol’skij and Piirainen (2005: 18) by treating terms such as fin de semana (‘weekend’) or primera comunión (‘first communion’) as nominal phrases.

3.2 Typological distribution

Another relevant statistic when it comes to shedding light on the characteristics of Spanish phraseology as it is used in formal and informal spontaneous language production is the typological distribution of the PUs documented in both oral contexts.

The results of the typological analysis of the PUs registered in the (sub-)corpora, in terms of occurrences, are presented in Tab. 3.

Typology of the Spanish PUs in Gran Hermano and CREA oral (sub-)corpora

Type |

Gran Hermano |

CREA oral |

||

occurrences |

% |

occurrences |

% |

|

Idioms |

952 |

63.4% |

326 |

93.9% |

Routine formulae |

542 |

36.1% |

20 |

5.8% |

Proverbs |

7 |

0.5% |

1 |

0.3% |

Total |

1501 |

100% |

347 |

100% |

As can be observed in Tab. 3, the presence of the type idioms is clearly dominant among the PUs that were documented in both oral contexts. However, there is a very significant discrepancy regarding the distribution of idioms and formulae, with the latter being 30% higher in the Gran Hermano corpus. As a result of this, it could be concluded that these pragmatically-oriented expressions are not representative of oral conversations in general, but that they are a distinctive feature of the phraseology used exclusively in spontaneous informal language production. In this sense, the data provided by Sosiński (2010, 2011) based on the PRESEEA GRANADA corpus fulfils the expectations of a (semi-)formal corpus – 18.9% of the PUs are categorised as routine phrases, i.e. the number is situated between the data obtained for the informal (36.1%) and the formal (5.8%) (sub-)corpora, but is closer to the latter (however, again, the data proposed by Sosiński should be treated with caution). Finally, the peripheral role of proverbs and sayings in both kinds of oral contexts has been confirmed.

3.3 Stylistic distribution

It is obvious that in informal discourse contexts speakers will tend to use more informal expressions than in more formal situations. However, in this section it is intended to reveal in detail the similarities and differences between the configurations of the PUs uttered in these two kinds of oral spontaneous language production.

For investigating the stylistic distribution of PUs, first it must be clearly established which styles we are referring to here and where their boundaries are. Nevertheless, to establish what is colloquial, vulgar, popular, neutral, literary, etc. is a very complicated task that goes far beyond the scope of this study. For this reason, the stylistic characterisations provided by the dictionaries will be employed, in this specific case, the labels proposed by the most complete and up-to-date work among the Spanish phraseological dictionaries published so far, i.e. Diccionario fraseológico documentado del español actual (DFDEA) by Seco et al. (2017).[15] Unfortunately, this is a major drawback because only those PUs included in the dictionary can be considered. From the 1501 occurrences documented in the approximately 30,000 words of the Gran Hermano corpus only 1033 (68.1%) are registered in DFDEA. On the other hand, from the 347 occurrences documented in the 10,000 words of the CREA oral subcorpus 284 (81.8%) are included in DFDEA. These percentages confirm that this issue is especially problematic when analysing informal oral language production owing to the fact that DFDEA collects exclusively PUs documented in written corpora (see Seco et al. 2017: XI–XII).

Following the categorisation used in DFDEA, eight stylistic labels will be proposed: literary, semicultured, neutral, colloquial, juvenile, uncultured, jargonistic, and vulgar. The stylistic distribution of the PUs documented in the (sub-)corpora is presented in Tab. 4.

Register labels of the PUs registered in DFDEA

Stylistic label |

Gran Hermano |

CREA oral |

||

occurrences |

% |

occurrences |

% |

|

Literary |

0 |

0.0% |

1 |

0.35% |

Semicultured |

0 |

0.0% |

1 |

0.35% |

Neutral |

603 |

58.4% |

238 |

83.8% |

Colloquial |

285 |

27.6% |

30 |

10.6% |

Juvenile |

4 |

0.4% |

0 |

0.0% |

Uncultured |

75 |

7.3% |

14 |

4.9% |

Jargonistic |

1 |

0.1% |

0 |

0.0% |

Vulgar |

65 |

6.3% |

0 |

0.0% |

Total |

1033 |

100% |

284 |

100% |

According to the data presented in Tab. 4, there are two basic features shared by both kinds of oral context: a) literary and semicultured PUs are highly infrequent in both kinds of spontaneous language production (just two occurrences in the CREA oral subcorpus – padre de la patria and a nivel de); b) most of the Spanish PUs used in oral conversations (at least among those listed in DFDEA) are stylistically neutral.

On the other hand, in the Gran Hermano corpus 41.6% of all the excerpted PUs can be considered informal, i.e. situated in the table “under” the neutral register (colloquial, juvenile, uncultured, jargonistic, or vulgar). On the contrary, a mere 15.5% of the PUs registered in the CREA oral are labelled as informal. In other words, the presence of informal PUs is almost three times more frequent in conversations uttered in informal discourse contexts than in formal situations.[16]

In this sense, the great majority of the uncultured PUs are due to just one pet phrase, o sea – 69 occurrences in Gran Hermano and all the occurrences (14) in the CREA oral subcorpus. The discourse marker phrase a ver (18 occurrences)[17] and the adverbial phrases a lo mejor (17) and en plan (13) are the most commonly used colloquial PUs in Gran Hermano.[18] In the case of the CREA oral subcorpus the most-repeated PUs are the discourse marker phrase no sé (eight occurrences), used to pick up the thread of the conversation, and the adverbial phrase a lo mejor (seven occurrences). According to the data, these two idioms are the only colloquial PUs often used in formal discourse contexts – the personal formula qué va, with just two occurrences, occupies the third position in the list. Besides, it is clear that adverbial phrases and those discourse marker phrases used as pet phrases are the two most frequent types of informal PUs in both oral corpora. However, they are comparatively much more commonly employed in informal oral language production. Besides, while o sea and a lo mejor seem to be characteristic of both oral discourse contexts, a ver and en plan are distinctive to Gran Hermano’s conversations.

A last but very significant divergence between the data obtained for both kinds of spontaneous language production is that more than 6% of all the PUs documented in the Gran Hermano corpus are labelled as vulgar.[19] On the contrary, there is not even one vulgar PU documented among the 10,000 words that form the CREA oral subcorpus.

According to all this, it could be concluded that one of the main disagreements between formal and informal oral contexts is the frequency of use of colloquial or uncultured PUs, but that an even more salient feature is the complete absence of vulgar PUs in the formal discourse contexts.

3.4 Individual distribution

Following Briz and Albelda (2013), formal and informal are not two absolute parameters, but, on the contrary, a contextual, gradual matter. Besides, even under the same conditions different people can behave in a linguistically dissimilar way. In this section the personal distribution in both (sub-)corpora will be shown in order to determine the tendencies when relating (in-)formal discourse contexts and individual linguistic behaviour. Specifically, three aspects will be considered. First, the individual general frequency will be presented and discussed, then the data regarding exclusively the informal PUs; finally, the frequency of vulgar PUs will be the object of attention.

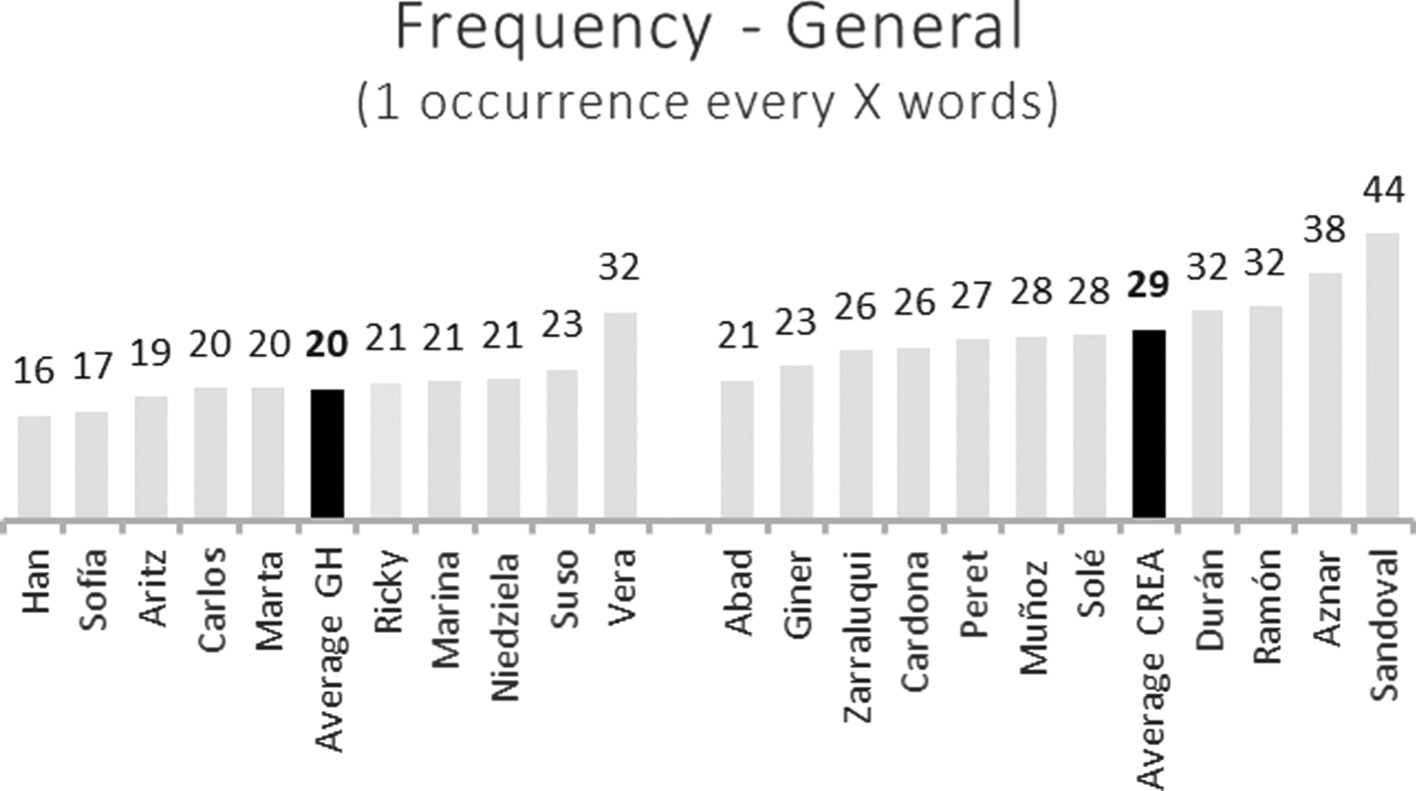

Fig. 1 undoubtedly confirms that, in terms of general frequency of use, personal linguistic preferences can be a key factor. Let us focus first on the Gran Hermano corpus; six out of the eleven contestants present a frequency very close to the average, being one PU used every 19 up to 21 words. Han (16) and Sofia (17) employ PUs slightly more than the average, while the contrary can be said about Suso (23). The only contestant who, according to the data, behaves as if he were speaking in a formal discourse context is Daniel Vera, since his ratio in terms of words per occurrence (32) is even higher than the average in the CREA oral subcorpus. On the other hand, the speakers in the formal discourse contexts seem to be much more heterogeneous in terms of general frequency. In most cases, their ratio is more distant from the average (one PU every 29 words) than among the contestants of Gran Hermano. However, these divergences between these two kinds of oral language production are undoubtedly affected by the different number of words of which the (sub-)corpora are compounded, as will be discussed below.

Individual general frequency of PUs in Gran Hermano and CREA oral corpora

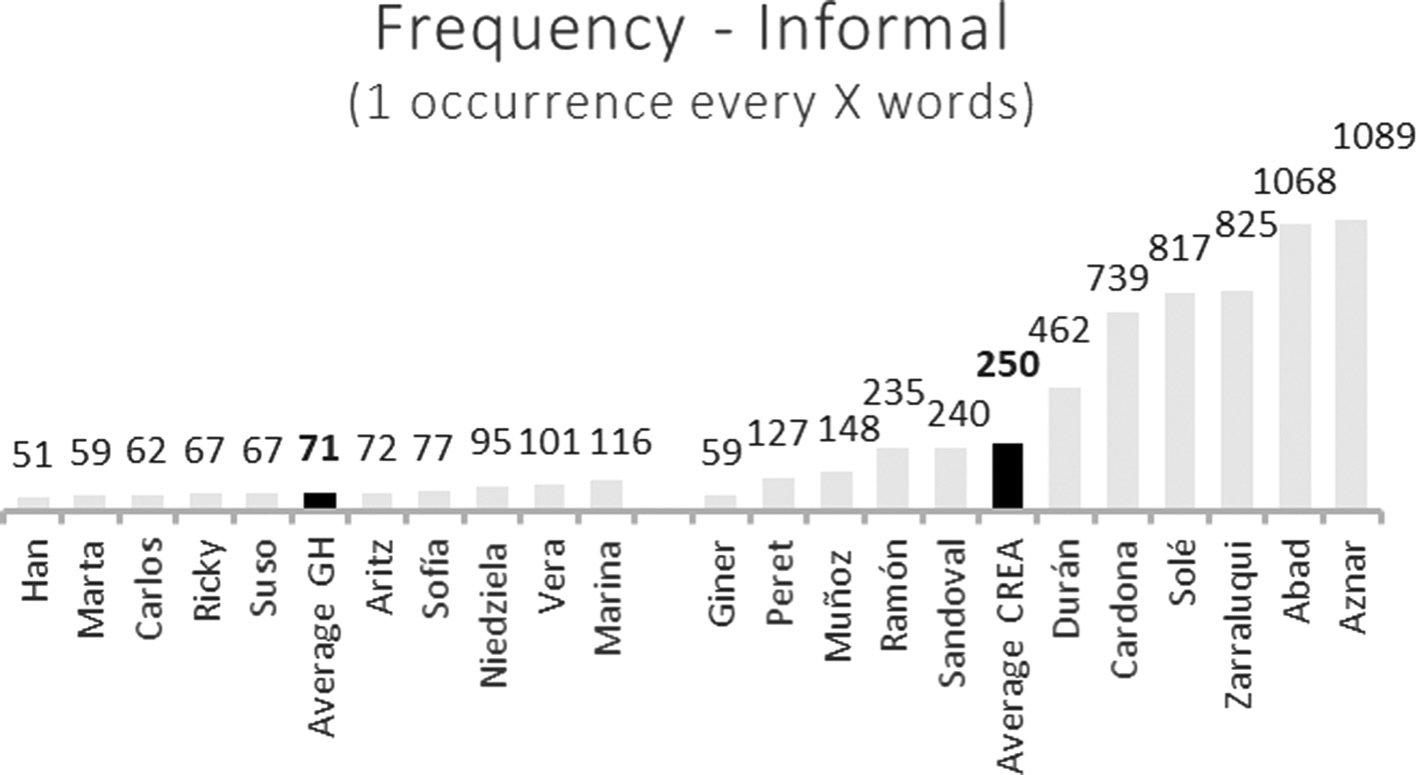

That said, the most interesting data for the purposes of this study is probably not the general frequency, but the numbers related to the individual use of informal PUs, i.e. colloquial, juvenile, uncultured, jargonistic, and vulgar PUs. Fig. 2 shows two clear tendencies.

Individual frequency of informal PUs in Gran Hermano and CREA oral corpora

First, although some significant divergences among the contestants of Gran Hermano can be observed, their frequencies are relatively alike (Han uses informal PUs 2.3 times more often than Marina), at least when compared with the numbers obtained for the speakers in the formal subcorpus. So, Agustín Jorge Giner, a businessman and the president of a modest football club in the Spanish third division, utters nine colloquial PUs and one uncultured one in just 585 words, i.e. he makes use of informal PUs 18.5 times more often than the former Spanish prime minister José María Aznar does (just one informal PU in 1089 words, a lo mejor) and his ratio is as low as the second lowest ratio in Gran Hermano. However, again this data should be treated with caution, since the number of words uttered by all the speakers in the CREA oral subcorpus is smaller than in the case of the contestants of Gran Hermano (see Tabs. 1 and 2).[20] Nevertheless, examples like Giner and Aznar demonstrate that speakers in formal contexts would tend to behave linguistically more heterogeneously than in more informal language production.

Second, it cannot be stated that informal language is used exclusively in informal discourse contexts. Some speakers tend to use informal expressions even in highly formal discursive situations, such as TV or radio interviews. Following the data, three possible profiles can be identified. On the one hand, there are speakers like Giner, who are not used to speaking in public and probably lack the proper linguistic tools or experience to behave “adequately” in these formal oral contexts. On the other hand, there are artists, such as the well-known musician Peret or the actress and model Amparo Muñoz, who seem not to be interested in “respecting” the linguistic prescription appropriate for formal language production, maybe because they wish to look natural and close to the audience, and consequently they behave on television as they would do in other less formal spaces (although probably not as informally as they would do if they were not being recorded). Finally, there are some interviewees who are used to talking in public and are perfectly aware of the importance, in their role as the public faces of companies or political parties, of using highly formal speech in these discourse contexts (some of them have even probably been trained for this purpose). Logically, people like Aznar, Abad, or Zarraluqui use almost no informal PUs in their discourse. Moreover, some speakers who are probably not so used to speaking in public often, but are able to produce formal Spanish when it is required, could be added to this third group, such as Cardona or Solé.

Finally, in Fig. 3 the frequency of use of vulgar PUs can be observed. The first obvious remark is that in formal discourse contexts the use of these rude expressions is drastically avoided. So, even those speakers who do behave linguistically as if they were talking in fewer formal oral contexts, such as Giner, Peret, or Muñoz, manage to avoid using vulgar PUs. On the contrary, all the contestants of Gran Hermano make use of profanity to a greater or lesser extent. Moreover, here the personal preferences are more visible than in terms of general and informal frequency. While some speakers, especially Suso, Marta, and Sofía, utter a vulgar PU approximately every 300 words, Niedziela does so every 1600 words and Han almost every 2700 words, i.e. Suso makes use of vulgar PUs 5.6 times more often than Niedziela and 9.4 times more often than Han does. The reasons for such individual divergences go beyond the scope of this study. However, a few suggestions can be proposed. First, it is not a gender question, since two out of the three contestants who most often make use of vulgar PUs are women (Marta and Sofía). Besides, personal circumstances can play an important role. This can be observed in the fact that the two least rude speakers in the Gran Hermano corpus have foreign backgrounds. Thus, although Niedziela was born in Spain, her family is Polish. Han was born in China and moved to Spain with his mother at the age of twelve. In addition to this, while Niedziela could be categorised as a native speaker of Spanish, Han presents some characteristics typical of a proficient[21] foreign speaker, including inaccurate versions of PUs such as *soltar de melena instead of soltarse la melena and *me importa un pedo instead of me importa un bledo.

Individual frequency of vulgar PUs in Gran Hermano and CREA oral corpora

A last remark regarding the individual distribution of PUs has to do with what could be called phraseological idiolects; in other words, with PUs that can be treated as personal discourse markers. According to the results of the analysis of Gran Hermano, the following phraseological idiolects can be pointed out: as already commented, the second most common pet phrase is o sea. In this sense, no other contestant uses a PU as often as Han utters o sea – 23 times in 2677 words, i.e. once every 116 words. Something similar can be stated for the habitual use of the discourse marker phrase es que by Niedziela (once every 219 words) and Carlos (once every 244 words).[22] Carlos also tends to use the adverbial phrase a lo mejor (once every 515 words) and the profanity me cago en la puta/leche/virgen (every 1123 words). This is the second most frequent vulgar PU used by one speaker just after the verbal phrase no tener ni puta idea, uttered by Sofía every 851 words. Marta’s favourite expression seems to be the interpersonal relation formula ¿sabes lo que te digo/quiero decir? (once every 554 words). Aritz’s distinguishing feature is the use of the impersonal formula ¡qué va! (once every 701 words). With nine occurrences, Marina’s most common pet phrase is again es que (once every 284 words), but she also often uses the following PUs – a veces (seven occurrences), o sea (six), dar la razón (five), and ya está and no sé (four each). Ricky utters the interpersonal relation formula no pasa nada once every 348 words and Daniel Vera diverse versions (11 occurrences, i.e. once every 138 words) of personal formulae with qué – ¡qué guay/bueno/asco/bien/divertido/guapo/peste/rabia! It is interesting that Suso does not use the most common pet phrases extremely often (es que four times, o sea twice, and a ver once in 2278 words), but he seems to like the verbal phrase saber mal (lit. ‘taste bad’) for expressing that something is unpleasant to him, since he uses it in three different conversations – once every 759 words (this PU is also uttered once by Niedziela).

In the CREA oral subcorpus it is more difficult to observe such a high frequency of certain PUs. In part this is due to the lower number of words uttered by every speaker that is registered, but in part also to the fact that pet phrases are much less frequent in formal contexts. According to the results of the analysis, the speakers can be divided into two main groups. The only three artists among the speakers stand out for the frequent use of o sea (Ceferino Moreno Sandoval once every 240 words, Amparo Muñoz once every 259 words, and Peret once every 339 words, i.e. more often than most of Gran Hermano’s contestants, representing 79% of all the occurrences of this uncultured discourse marker phrase in the CREA subcorpus). On the contrary, Agustín Jorge Giner, although he is the speaker with the most informal speech in this subcorpus (see Fig. 2), does not use pet phrases often (no sé twice and o sea once). However, he utters the colloquial adverbial phrase a lo mejor five times, i.e. once every 117 words. The second group would include those speakers who employ rather formal Spanish. In this case, the frequency of pet phrases is extremely low. However, two tendencies can be observed. Some of the interviewees often employ non-expressive PUs as tools to carry out and organise their speech. For instance, 32% of the PUs uttered by the hospitality manager Marta Solé are prepositional phrases (especially dentro de, four times and a través de, three times). Josep Miquel Abad constantly employs formal discourse marker phrases (41% of all his PUs), such as es decir (six times), por (lo) tanto (five times), or dicho esto and por ejemplo (twice each). A similar situation, but less extreme, can be observed in the speech of the coffin manufacturer Cecilio Cardona, with 28% of formal discourse marker phrases (he uses por ejemplo once every 148 words). These three speakers utter 70% of all the formal discourse marker phrases and 57% of all the prepositional phrases in the CREA subcorpus. The remaining speakers in this second group also employ rather formal discourse, but they rarely use prepositional phrases and formal discourse marker phrases. This group includes Luis Zarraluqui, who utters a veces every 206 words, and the three remaining interviewees, who do not use any PU more than twice – the former priest Ramón, Miguel Durán, and José María Aznar.

4 Concluding remarks

In the preceding pages the configuration of the phraseology as it is used in formal and informal spontaneous oral production – based on the data obtained from the Gran Hermano corpus and the CREA oral subcorpus – has been investigated according to four variables: frequency distribution, typological distribution, stylistic distribution, and individual distribution. The following conclusions can be drawn:

A tendency has been observed, according to which the more informal the discourse context, the higher the frequency of use of PUs (approximately 30% higher).

From the three types of PUs that have been proposed, idioms are clearly dominant in both formal and informal oral contexts. Besides, routine formulae are a distinctive feature of the phraseology used exclusively in informal language production. Finally, proverbs and sayings play a peripheral role in both kinds of oral contexts.

Stylistically neutral PUs are the most common type of expressions in both oral spontaneous (sub-)corpora (at least when considering the PUs registered in the DFDEA). However, PUs labelled as colloquial and uncultured are approximately three times more frequently documented in informal discourse contexts than in formal language production. Nevertheless, an even more salient feature is the total absence of vulgar PUs in the CREA oral subcorpus, i.e., even those speakers who employ informal PUs as often as the contestants of Gran Hermano do not utter any vulgar PUs at all. Consequently, it can be stated that vulgar vs. non-vulgar PUs – and not so much informal vs. non-informal PUs – is the main disagreement between formal and informal spontaneous oral contexts.

Formal and informal must not be understood as two binary poles, but rather as the ends of a continuum, so that there are speakers in formal discourse contexts who often utter informal PUs, even more often than some people involved in a conversation conducted in a very informal situation. On the contrary, it seems unusual to use formal PUs in informal contexts. In this sense, the individual characteristics of the speaker seem to play a relevant role, especially among those circumscribed in formal discourse contexts (in informal contexts speakers would tend to behave linguistically more homogenously).

In informal spontaneous language production, the divergences in terms of individual use are relatively small when relating general frequencies of use of phraseology. However, they grow when it comes to comparing the use of informal PUs and, especially, when the rates of vulgar PUs are considered. According to this, using vulgar PUs more or less frequently would be a highly individual issue.

5 References

Arnaud, Pierre, Emmanuel Ferragne, Diana M. Lewis & François Maniez. 2008. Adjective + noun sequences in attributive or NP-final positions. Observations on lexicalization. In Sylviane Granger & Fanny Meunier (eds.), Phraseology. An interdisciplinary perspective, 111–125. Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins.10.1075/z.139.13arnSearch in Google Scholar

Briz, Antonio. 2010a. El español coloquial: situación y uso. Madrid: Arco Libros.Search in Google Scholar

Briz, Antonio. 2010b. Lo coloquial y lo formal, el eje de la variedad lingüística. In Rosa M. Castañer Martín & Vicente Lagüéns Gracia (coord.), De moneda nunca usada: Estudios dedicados a José Mª Enguita Utrilla, 125–133. Zaragoza: Instituto Fernando El Católico, CSIC.Search in Google Scholar

Briz, Antonio & Marta Albelda. 2013. Una propuesta teórica y metodológica para el análisis de la atenuación lingüística en español y portugués. La base de un proyecto en común (ES.POR.ATENUACIÓN). Onomázein. Revista semestral de lingüística, filología y traducción 28. 288–319.Search in Google Scholar

Čermák, František, Jiří Hronek & Jaroslav Machač. 2009. Slovník české frazeologie a idiomatiky I – IV (SČFI). Praha: Leda.Search in Google Scholar

Dobrovol’skij, Dmitrij & Elisabeth Piirainen. 2005. Figurative Language: Cross-cultural and cross-linguistic perspectives. Oxford, UK: Elsevier.Search in Google Scholar

Dovey, Jon. 2004. It’s only a game show: Big Brother and the theatre of spontaneity. In Ernest Mathijs & Janet Jones (eds.), Big Brother international. Formats, critics and publics, 232–248. London & New York: Wallflower Press.Search in Google Scholar

Haugh, Michael & Valeria Sinkeviciute. 2018. Accusations and interpersonal conflict in televised multi-party interactions amongst speakers of (Argentinian and Peninsular) Spanish. Journal of Language Aggression and Conflict 6(2). 248–270.10.1075/jlac.00012.hauSearch in Google Scholar

Kováříková, Dominika & Marie Kopřivová. 2014. Authorial phraseology: Karel Čapek and Bohumil Hrabal. In Vida Jesenšek & Dmitrij Dobrovol’skij (eds.), Phraseology and culture, 565–575. Maribor: Filozofska fakulteta Maribor.Search in Google Scholar

López Simó, Mireia. 2016. Fórmulas de la conversación. Propuesta de definición y clasificación con vistas a su traducción español-francés, francés-español. Alicante: Universidad de Alicante dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

Moon, Rosamund. 1997. Vocabulary connections: Multi-word items in English. In Norbert Schmitt & Michael McCarthy (eds.), Vocabulary: Description, acquisition and pedagogy, 40–63. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Moon, Rosamund. 1998. Fixed expressions and idioms in English. A corpus-based approach. New York: Clarendon Press.10.1093/oso/9780198236146.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Penadés Martínez, Inmaculada. 2004. ¿Caracterizan las locuciones el registro coloquial? In M. Villayandre Llamazares (ed.), Actas del V Congreso de Lingüística General, León, 5-8 de marzo de 2002 (III), 2225–2235. Madrid: Arco Libros.Search in Google Scholar

Penadés Martínez, Inmaculada. 2012. La variación en las locuciones a partir de materiales del PRESEEA (Barrio de Salamanca, Madrid). In Ana M. Cestero Mancera, Isabel Molina Martos & Florentino Paredes García (eds.), Actas del XVI Congreso Internacional de La Asociación de Lingüística y Filología de la América Latina (Alcalá de Henares, 6-9 de junio de 2011), 2081–2091. Alcalá de Henares: Universidad de Alcalá, Servicio de Publicaciones.Search in Google Scholar

Penadés Martínez, Inmaculada. 2015a. Implicaciones de la frecuencia de uso de las locuciones en la elaboración de un diccionario. Estudios de Lingüística Universidad de Alicante (ELUA) 29. 253–277.10.14198/ELUA2015.29.11Search in Google Scholar

Penadés Martínez, Inmaculada. 2015b. Las locuciones verbales en el habla de Madrid (distrito de Salamanca). In Ana M. Cestero Mancera, Isabel Molina Martos & Florentino Paredes García (eds.), Patrones sociolingüísticos de Madrid, 251–286. Bern: Peter Lang.10.4067/S0718-93032015000100010Search in Google Scholar

Ruiz Gurillo, Leonor. 1998. La fraseología del español coloquial. Madrid: Ariel.Search in Google Scholar

Seco, Manuel, Olimpia Andrés, Gabino Ramos & Carlos Domínguez. 2017. Diccionario fraseológico documentado del español actual: locuciones y modismos españoles (DFDEA). Madrid: JdeJ Editores.Search in Google Scholar

Sinkeviciute, Valeria. 2017a. Variability in group identity construction: A case study of the Australian and British Big Brother houses. Discourse, Context & Media 20. 70–82.10.1016/j.dcm.2017.09.006Search in Google Scholar

Sinkeviciute, Valeria. 2017b. What makes teasing impolite in Australian and British English? ‘Step[ping] over those lines […] you shouldn’t be crossing’. Journal of Politeness Research 13(2), 175–207.10.1515/pr-2015-0034Search in Google Scholar

Sosiński, Marcin. 2010. Datos sobre las locuciones nominales en el corpus PRESEEA-Granada. In Actas del VII Congreso Internacional de la Asociación Asiática de Hispanistas, 137–148. Pekín: Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press.Search in Google Scholar

Sosiński, Marcin. 2011. La norma fraseológica: locuciones verbales en el corpus PRESEEA-Granada. In Edyta Waluch-de la Torre (ed.), Encuentros 2010. Vol. 1: La norma lingüística del español, 119–129. Varsovia: Editorial Instituto de Estudios Ibéricos e Iberoamericanos.Search in Google Scholar

Tran, Giao Quynh. 2006. The naturalized role-play: An innovative methodology in cross-cultural and interlanguage pragmatics research. Reflections on English Language Teaching 5(2). 1–24.Search in Google Scholar

Varela, Fernando & Hugo Kubarth. 1994. Diccionario fraseológico del español moderno. Madrid: Gredos.Search in Google Scholar

Annex

Annex I. Idioms documented in the Gran Hermano corpus

a base de, a bocajarro, a gusto (2), a la altura de, a la defensiva, a la vez, a lo bestia, a lo mejor (17), a lo/la que, a machete, a mano, a medida que, a muerte (3), a pulso, a punto de, a que [+ pregunta] (2), a saco, a solas, a su* bola, a su* manera (3), a su* rollo, a todas horas, a todo esto, a tope (4), a través de, a última hora, a unas malas, a veces (16), a ver [más proposición interrogativa/L. conj.] (12), a ver quién (es el guapo/valiente que), a ver si [deseo/L. conj.] (7), a ver [L. marc.] (18), a/de malas, abrir los ojos, acabarse la fiesta, ahora mismo/mismito (2), al / a un lado (3), al cabo de, al cien por cien, al contrario, al final (14), al menos, al oído, al principio (de) (5), al revés (6), alguno que otro, amor odio, andarse/irse por las ramas, aparte de, así que, aun (y) así / incluso/siquiera así, aunque sea (2), bordarlo, cada dos por tres, cada uno (4), cada vez que, cagarla, coger coraje, coger el truco, cogerla/pillarla, comerle la polla, comerse la cabeza, como (la) mierda / como si fuera una mierda (2), como (muy) tarde, como (un) loco (2), como el perro y el gato, como en casa [sentirse], como mucho (2), como que, como quien no quiera la cosa, como si (3), como un cerdo, como una casa, con el corazón, con todo mi amor, correr riesgo, dar (o meter) caña (2), dar cosa, dar fe, dar guerra, dar gusto, dar la razón (7), dar las gracias, dar pie (2), dar por hecho, dar yuyu (2), dar/pegar para el pelo (2), dar/pegar un corte, darle [a algo], darle algo [a alguien], darlo todo, darse cuenta [de algo], darse de cabezazos (contra la pared) (2), dársele [algo + valoración], de acuerdo, de antemano, de bote, de cachondeo, de cojones, de compras [ir/salir/estar], de frente, de golpe (2), de lado (2), de lo lindo, de lujo, de marca, de mierda (3), de momento (5), de muerte, de nuevo, de parte (de), de puta madre (3), de rebote, de repente, de risa, de siempre, de sobra, de todo (3), de verdad [L. adv.] (4), de verdad [L. adj.], de viaje, de/con mil amores, de/en broma (3), dejar tirado (2), dejarlo para última hora, delante de, dentro de, día a día, echar de menos, echar la papa/pota, el tema es que, en (repetidas) ocasiones, en abundancia, en cabeza, en cero coma, en contra, en directo, en el culo, en el fondo, en el último momento, en frente, en las mismas, en medio (4), en mi vida (2), en opinión, en plan (13), en realidad, en serio (8), en su salsa, en teoría, en todo momento, en verdad (4), en vez de (3), entre horas (2), es decir, es que (113), es verdad que (4), está claro que, estar ahí (ahí) (2), estar como una (puta) chota, estar como una cabra (2), estar con / tener las hormonas revolucionadas, fundírsele los plomos, haber que ver [algo], hacer caso, hacer falta (5), hacer gracia, hacer ilusión, hacer un feo, hacerse el loco, hagas lo que hagas, hasta el gorro, hasta la polla (2), hasta la saciedad, hecho (una) mierda/ como una mierda (3), hoy día / en día, ir/salir de marcha, irse de las manos, irse/salir por los cerros de Úbeda, írsele la olla, jugársela (2), la verdad (2), liarla, llevar la contraria, llevar(lo) [+ valoración], llevarse [+ valoración] (3), lo mismo [=a lo mejor] (2), lo mismo [=igual] (6), lo peor, lo que pasa/ocurre es que (2), lo que sea (3), lo único es que (2), mala leche, mala vida, más bien, más claro que el agua, más o menos (5), mentiría si (te) dijera que, meter la pata, meter la tijera (2), meter mano, mi amor (3), mi vida (3), mirada perdida, mitad y mitad, morirse/partirse de risa, nada de nada, ni de coña, ni mucho menos, ni nada (del/por el estilo) (4), ni por el forro, ni que, ni siquiera (2), (ni) un pelo, ni… ni hostias, no poder más, no por nada, no sé qué [L. adj.], no sé qué [L. marc.] (16), no sé qué [L. pron.], no sé (11), no sea que /no vaya a ser que (2), no tener (ni) (puta, pajolera) idea (6), o algo (5), o así, o sea / o séase (3), o sea [muletilla] (69), o tal, oler que alimenta, otra vez (3), para nada (2), parecerle [+ valoración] (2), pasarlo [+ valoración], pasarse por la cabeza, pedazo de (2), perder el tiempo (2), perico el de los palotes, pero bueno (7), pero claro (2), perro/ito faldero (2), poca vergüenza, poco a poco (2), poner/hacer ojitos, ponerse burro, por A por B, por ahí [localización] (2), por ahí [aproximadamente], por ciento (8), por debajo de, por dentro, por ejemplo (14), por encima (4), por la cara (3), por lo bajo, por lo menos, por los pelos/un pelo, por mucho/más que, por poner un ejemplo, por si (acaso), por voluntad propia, porque sí, pues eso (6), pues mira (7), pues sí, (pues) sí que (3), (pues) ya está, qué es de, que es un gusto/da gusto (2), que pela, ¡qué sé yo! / ¡yo qué sé!, que sepas que, que si [+ repetición del verbo anterior], que si tal/que tal, que te cagas (3), que todas las cosas, quedarse frito, quieras que no (2), romper/partir/dar pana, saber mal (4), salir del coño/moño, salirle de los huevos / del nabo, seguir el hilo (de la conversación), seguir el rollo, según qué cosas, ser el/lo/la que es, ser la polla, ser una máquina, ser/dar igual (10), ser/dar lo mismo, siempre que, sin embargo, sin más (2), sin querer, sin tanta hostia, sobre todo, soltarse la melena (2), su* madre, sudársela/sudar la polla (2), tal cual (5), tal vez, tal y cual (3), tanto… como…, te guste o no, tener (un par de) cojones, tener huevos, tener la gracia en el culo, tener que ver (4), tener/llevar razón (3), tener/ser *tu día, tirar caña (2), tirar del carro, tocar/chupar la polla (3), todas las cosas, todo cristo, todo el día (9), todo el mundo (6), todo el rato (2), tú a lo tuyo, un cero a la izquierda, un euro, un huevo (4), un montón [L. adv.] (9), un montón [L. nom.] (10), un poco [L. adv.] (18), un poco [L. nom.] (10), un tanto, una especie (de), una gota, una mierda (3), una pasta, una vez que, una/otra cosa (distinta) es que (2), valer/merecer la pena, vamos a ver, vender la moto, venir de lejos/de atrás (2), venirse arriba, y eso / todo eso (2), y mira que, y nada (2), y tal (11), y todo (11), (y) ya está (12), ya (te) digo (3).

Annex II. Routine formulae documented in the Gran Hermano corpus

a cascarla, a la mierda, a la una… a las dos… (y) a las tres / una, dos y tres (4), a lo mejor, ¿a que sí? (7), a ver (qué remedio) (3), a ver [fórmula de relación interpersonal] (8), a ver [fórmula personal] (12), (además) de verdad, adivina adivinanza, ¿ah sí? (5), ah, bueno (4), ah, no (2), ahí está, ahí lo dejo, ay señor, ay sí (2), buenas noches, buenos días (3), como lo oyes / lo que oyes, ¿cómo lo ves?, como quien dice, da/es igual (12), de nada, ¿de qué vas?, de verdad (10), déjame en paz (2), déjate de historias, desde luego, despacito y buena letra, ¿en qué mundo vives?, ¿en serio? (18), ¡es acojonante!, ¡es broma! (3), ¡es increíble!, es lo que hay, es verdad [fórmula impersonal] (10), es verdad [fórmula personal] (2), escucha/mira una cosa (2), eso es (2), eso espero, eso no te* lo crees ni tú*, está claro / claro está, ¡está guapo!, gracias por la parte que me toca / por lo que me toca, hasta mañana, hay gente para todo, hijo mío, hostia puta, la has cagado, la madre que le* parió/trajo (2), ¿lo entiendes?, lo más seguro, lo que estábamos diciendo, lo que te digo, lo que yo te diga, lo siento (mucho) (3), ¿lo ves?, madre mía / de dios (4), manos a la obra, más y mejor, me cago en la puta/leche/virgen (7), me importa un bledo, me la pela, me la suda (2), menos mal (2), menuda (puta) mierda, mira a ver (2), mira qué bien, mira que me extraña, muchas gracias (2), ¡muy bien! (2), ¡muy guapo!, ¡muy jevi!, no (lo) sé [fórmula personal cognitiva] (5), no (lo) sé [fórmula personal sintomática] (24), ¡no (me) jodas! (2), ¿no crees? (2), no es justo, no importa, no me digas, no me hagas esto (2), ¡no me lo puedo creer!, no mientas (2), no pasa nada (6), no sé yo, no seas putas, no te preocupes (4), (no tengo) ni (puta, pajolera) idea (3), no veas (2), no volveré a hacerlo, ¿o qué? (15), otra vez, pero bueno, pero esto qué es, pero hombre, pero qué va a ser [alguien algo], por eso (te digo) (4), por favor [fórmula personal] (7), por favor [fórmula de relación interpersonal] (15), puede ser (5), pues eso (2), pues nada, pues no, pues sí, (pues) ya está [fórmula personal] (8), (pues) ya está [fórmula de relación interpersonal] (4), ¡qué (puto) asco! (5), ¿qué (te) pasa? (8), ¡qué alegría!, ¡qué arte!, ¡qué bien!, ¡qué bueno! (3), ¡qué cabrón! (3), ¡qué chulo!, ¡qué coñazo!, ¡qué cosa(s)! (2), ¡qué divertido!, ¡qué envidia!, ¡qué estrés!, ¡qué fuerte! (6), ¡qué gracia / vaya (una) gracia! (2), ¡qué guapo! (9), ¡qué guay! (12), ¡qué horror!, ¡que le* den por el culo!, ¡qué mal (me parece)!, ¡qué maravilla! ¿qué me cuentas / estás contando?, ¡qué miedo!, ¡qué mono!, ¡qué movida!, ¡que no! [fórmula personal] (2), ¡que no! [fórmula de relación interpersonal] (3), ¡qué pena! (2), ¡qué pesadilla!, ¡qué pesado!, ¡qué peste! (3), ¿qué quieres que (le) haga?, ¿qué quieres que te diga?, ¡qué rabia!, ¡qué raro!, que se prepare, ¡qué sé yo! / ¡yo qué sé! (8), que sí (3), ¡qué sueño!, ¡qué suerte!, ¿qué tal? (4), ¡que te den por el culo!, ¡qué triste!, ¡qué va! (11), (qué) más quisieras, ¿sabes lo que pasa? (2), ¿sabes lo que te digo / quiero decir? (8), ¡será cabrón!, ¿sí o no? (2), si tú supieras, sí hombre, sí pero no, sí ya, ¿sí, no?, tal cual te lo digo, tal para cual, te digo una cosa, te lo digo (yo) (3), ¿te lo puedes creer?, te pido perdón, ¡te voy a matar!, te* lo juro/prometo [fórmula personal] (10), te* lo juro/prometo [fórmula de relación interpersonal], ¡te* vas a cagar! (2), ten cuidado, (todo) bajo control, tres… dos… uno… (5), ¿tú crees?, ¿tú te crees (que es normal/posible)?, tú tranquilo, (vamos) digo yo (2), vas a flipar, ¡vaya asco! (2), ¡vaya mierda!, ¡vaya putada!, ¡vaya tela!, venga a [+ infinitivo], venga va/vamos [19], ¡venga, hombre!, ¡vete a la mierda! (2), (vete) a saber (2), vete/anda por ahí (2), y lo sabes, ¿y eso?, y fuera, ¿y qué le voy a hacer? (2), ¿y qué?, ya (lo) veremos (2), ya está (9), ya lo sé (5), ya te digo (4), ya verás / verás tú / y verás (2), ya ves (3).

Annex III. Proverbs documented in the Gran Hermano corpus (in the form used by the speakers)

cada ladrón se piensa que son de su condición, mejor una verdad que duela que una mentira duradera, no cantes victoria antes de tiempo, una cosa es una cosa y otra cosa es otra cosa, una vez metido nada de lo prometido.

Annex IV. Idioms documented in the CREA oral subcorpus

a disposición, a juicio, a la altura del betún, a las órdenes, a lo largo de (2), a lo mejor (7), a mano, a nivel de, a nombre de [una persona o entidad], a su* aire, a través de (8), a veces (9), a ver [L. marc.], además de, al cabo de (2), al contrario / por el contrario / todo lo contrario (3), al final (2), al frente de, al menos, al mismo tiempo, al principio (de), alguna vez (2), andar listo, aparte de (3), aunque parezca mentira, cada vez que, cerrar la(s) puerta(s) [a alguien], como cualquier otro/a/os/as (3), como tal, como un tiro, con tal de [+ inf.], con toda franqueza, con toda sinceridad, dar por todos los lados [a alguien], dar el salto, dar rienda suelta (2), dar un paso adelante, dar/echar marcha atrás, dar/pedir explicaciones, darse cuenta [de algo] (3), de acuerdo, de alguna forma/en cierta forma, de boquilla, de brocha gorda, de (la) calle, de entrada, de hecho [L. adv.], de hecho [L. marc.], de modo que, de momento, de persona a persona, de principios, de pronto, de repente, de todas formas, de todas maneras (3), del corazón, dentro de (7), desde el primero hasta el último, desde luego (2), dicho esto (2), en absoluto, en cambio (2), en contacto, en cuanto, en cuanto a, en este/ese sentido (5), en fin, en general [L. adj.] (2), en general [L. adv.] (4), en la cuneta, en líneas generales, en ocasiones (4), en parte, en picado, en punta, en realidad (4), en su momento, en tanto en cuanto, en todo/cualquier caso, en vez de, en vigor, entre otras cosas (2), entre/mientras tanto, es decir (8), es que (3), estar con alguien, fuera de, hacer el juego, hacer falta (2), hacer las maletas, hacer todo lo posible, hacerse (a) la idea, hasta el punto de, hoy (en) día (2), ir con la cabeza muy/bien alta, junto a (2), las reglas del juego, llamar la atención, llegar alto, lo mismo (4), lo que pasa/ocurre es que (3), lo que se dice, más allá (2), más bien (2), más o menos, mayor de edad, mejor dicho, nada más (que), ni mucho menos, no sé (8), o sea (14), otra vez, otras veces, padre de la patria, parecerle [+ valoración], perder de vista [2], poner de manifiesto, poner una cruz, por aquello de, por ciento, por ejemplo (18), por libre, por lo demás, por lo menos, por lo visto / que se ve (2), por mucho/más que, por otra parte, por parte [de una persona] (2), por (lo) tanto (8), prestar atención, puerta abierta a, pues bien (2), pues claro, pues eso, pues sí, punto de vista, quieras o no quieras, quieras que no, respecto a/de (3), salir al paso (2), siempre y cuando, sin (la menor / ninguna) duda (3), sin embargo, sin ir más lejos, sobre todo (4), tal vez (4), tanto… como…, ser un honor para, tener que ver, tener tirón, tener/llevar razón, tener/tomar en cuenta (4), tocar/batir/hacer (las) palmas (3), todo el mundo (2), tomar conciencia, tomar el pulso, traer/tener sin cuidado, un (buen, cualquier) día, un montón, un poco [L. adv.] (11), un poco [L. Nom.] (1), una especie de, una serie de circunstancias, una vez más (2), valer/merecer la pena, y demás, y tal (3), (y) ya está.

Annex V. Routine formulae documented in the CREA oral subcorpus

a ver, buenas noches, buenos días, de ninguna manera, de verdad, desde luego, en fin (4), es cierto, gracias a Dios, lo siento, me explico, no lo sé (2), ¡qué decirte!, que en paz descanse, ¡qué va! (2).

Annex VI. Proverbs documented in the CREA oral subcorpus (in the form used by the speakers)

Quien compra un paraguas cuando llueve, en lugar de pagar seis, paga nueve.

©2020 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Editorial

- Editorial

- Articles

- Constructing subject-specific lists of multiword combinations for EAP: A case study

- Variations sur les expressions figées : quelle(s) traduction(s) chez les apprenants?

- Bridging the “gApp”: improving neural machine translation systems for multiword expression detection

- Spanish phraseology in formal and informal spontaneous oral language production

- The spatial conceptualization of time in Spanish and Chinese

- Das semantische Potential der Idiome aus kognitiver Perspektive

- La phraséologie dans l’étude du français langue maternelle : des faits de langue d’Hippolyte-Auguste Dupont aux faits d’expression de Charles Bally

- Obituaries

- Obituary

- Book reviews

- Book reviews

- Book reviews

- Book reviews

- Book reviews

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Editorial

- Editorial

- Articles

- Constructing subject-specific lists of multiword combinations for EAP: A case study

- Variations sur les expressions figées : quelle(s) traduction(s) chez les apprenants?

- Bridging the “gApp”: improving neural machine translation systems for multiword expression detection

- Spanish phraseology in formal and informal spontaneous oral language production

- The spatial conceptualization of time in Spanish and Chinese

- Das semantische Potential der Idiome aus kognitiver Perspektive

- La phraséologie dans l’étude du français langue maternelle : des faits de langue d’Hippolyte-Auguste Dupont aux faits d’expression de Charles Bally

- Obituaries

- Obituary

- Book reviews

- Book reviews

- Book reviews

- Book reviews

- Book reviews