Abstract

This paper examines the dynamic interplay between the global geopolitical risk and eleven decentralized finance (DeFi) digital currencies during the inflationary burden caused by the Russia-Ukraine war episodes. Daily data spanning from 13 October 2021 to 29 October 2024 and the innovative Quantile-Vector Autoregressive (Q-VAR) methodology are employed for estimating the pairwise, joint and network linkages at the lower, middle and upper quantiles. High levels of geopolitical risk are more connected with bull markets of the DeFi assets and new war episodes strengthen this relation. Geopolitical tensions combined with high inflation lead to the GPR becoming major determinant of DeFi markets so contributing to the transition to the digital decentralized cashless financial system. Maker is the leading DeFi asset in this transition and constitutes a promising successor of fiat currencies that suffer from devaluation generated by conflicts.

1 Introduction

Intense war episodes during the last years have brought to the forefront the necessity for further elaboration on the impacts that geopolitical uncertainty causes on the real economy and financial markets in a global context. The series of subsequent periods of turmoil such as the Global Financial Crisis, the Sovereign Debt Crisis and the Covid-19 pandemic have fueled the need for expansionary fiscal action taking and unconventional monetary policies (Afonso et al. 2018; Chen et al. 2016; Cukierman 2013; Mishkin 2009; Papadamou, Spyromitros, and Kyriazis 2018; Papadamou, Kyriazis, and Tzeremes 2019a, 2019b; Papadamou, Kyriazis, and Tzeremes 2020, Papadamou, Siriopoulos, Kyriazis 2020; Wu, Xie, and Zhang 2024). These have led to liquidity infusion in an unprecedented level, leaving little space for policymaking since the outbreak of the Russia-Ukraine conflict. Elevated geopolitical stress has caused supply chain disruptions and has brought about intense inflationary phenomena.

This has resuscitated concerns about the suitability of national currencies as stores of value and has triggered a vivid debate about the urgency for adopting more eligible, low-cost and digital forms of liquidity (Chen and Siklos 2022; Maouchi, Charfeddine, and El Montasser 2022; Zhao 2022). Such currencies would be decentralized, enjoying high demand and good performance and would be able to act as shields from inflation. In these conditions, geopolitical risk could become a major determinant of economic and financial activity. Its growing footprint on economic and financial matters enables geopolitical uncertainty to function as the steering wheel for the transformation of the existing financial landscape into a more flexible financial system with mainly digital forms of money and investments.

Decentralized finance (DeFi) constitutes an asset category with no requirement to abide by the mandates of a central authority nor to conform to regulation. DeFi assets are based on distributed ledgers and smart contracts – with the use of blockchain – that permit to avoid the use of intermediaries such as banking institutions, brokers or exchanges (Makarov and Schoar 2022; Zetzsche, Arner, and Buckley 2020). They are considered to be promising successors and potentially improved alternatives for traditional national currencies. The latter are prone to devaluation due to their vulnerability to inflationary pressures when crises emerge. Currency devaluations emerge due to supply shortages being accompanied with high demand-originated inflation and money shortages which have to be confronted with ample liquidity infusions by central banks. New money created and injected to the economy leads to upwards pressures on the price levels so results in devaluation of fiat national currenciesa and wealth reductions (Chiu and Molico 2010). This underlines the need for vehicles to protect from wealth and income losses.

There is a three-fold perspective by which the relation between geopolitical risk and decentralized finance should be considered. Firstly, from the viewpoint of lack of stability in financial systems brought about from geopolitical tensions. Financial systems frequently experience severe instability as a result of events like currency depreciation or economic penalties. Because of this uncertainty, people and companies are searching for more secure and dependable alternatives to traditional financing. Given that it functions on a foundation that is both censorship-resistant and borderless, decentralized finance offers an appealing alternative. It is especially attractive to consumers in areas with unstable economies as it enables them to access financial services without being constrained by regional regulatory frameworks. Secondly, there is the angle of the impacts of GPR on market behaviour. Increased market volatility may result from an array of geopolitical events, such as wars, trade disputes, and political changes. These types of incidents frequently undermine trust in traditional financial institutions, leading investors to turn to decentralized assets like cryptocurrency for safety. These digital currencies are becoming increasingly appealing as hedges in uncertain times since they are regarded to constitute a type of insurance against market swings and the possible loss of value connected with traditional assets. Thirdly, the regulatory framework vis-à-vis adoption of decentralized finance should be considered. Governments may impose more stringent laws on digital assets in response to rising geopolitical tensions, which might make it more difficult for DeFi platforms to gain traction. However, because of their intrinsic design, which encourages decentralization and autonomy from centralized authority, these legislative reforms may also lead to increased interest in DeFi systems. Despite regulatory obstacles, demand for these platforms may rise as consumers learn more about the advantages of DeFi, such as enhanced privacy and less reliance on conventional banking systems.

Inspired by such important contemplations about the connection of war issues with the evolution of the economy, this study delves into investigating the dynamic relationship that global geopolitical risk exhibits with eleven DeFi digital currencies with large market capitalization. The modern Quantile-VAR methodology as in Kyriazis et al. (2024) is employed to estimate the net pairwise directional connectedness, the net extended joint connectedness and the network connectedness. Examination takes place for alternative levels of GPR and bear, normal or bull DeFi markets represented by the lower, middle and upper quantiles.

This research is built on earlier studies such as Koop, Pesaran, and Potter (1996), Pesaran and Shin (1998), Gabauer (2020), Stenfors, Chatziantoniou, and Gabauer (2022), Dimitriadis, Koursaros, and Savva (2024a, 2024b, 2024c), Hong et al. (2024) and Kyriazis et al. (2024). This work is connected with earlier academic papers that investigate how geopolitical risk is linked with the real economy (Balestra, Caruso, and Di Domizio 2024; Caldara and Iacoviello 2022; Caldara et al. 2022; Kyriazis and Economou 2023; Li et al. 2024; Yang et al. 2023) and financial markets (Baur and Smales 2020; Chiang 2022; Fang et al. 2024; Ngo et al. 2024; Salisu, Lasisi, and Tchankam 2022; Selmi, Bouoiyour, and Wohar 2022; Wang, Wu, and Xu 2019; Zheng et al. 2023). This paper fills a significant gap in relevant literature by providing a three-fold contribution. Firstly, this is the first study focusing on the impact of geopolitical risk on decentralized finance markets. Secondly, the dynamic connectedness is examined both by pairwise and joint perspectives as well as through the lens of network connectedness by employing three alternative advanced specifications of the Quantile-VAR methodology. Thirdly, this paper sheds light on the potential of the transition to the cashless digital economy and financial markets through the prism of inflation caused by both unconventional monetary policies and supply shortages in conditions of elevated geopolitical uncertainty. Thereby, this study advances research on the impacts of geopolitical risk on financial markets by examining financial evolution through the lens of decentralized finance which constitutes the most innovative and promising aspect of money innovation and development. Shedding light on this connection provides a quantum leap towards better understanding the transformation perspectives of the financial outlook and the prospects for progress in the field of monetary financial economics. The inflationary burden imposed by geopolitical tensions has rendered the feasibility of the monetary evolution the benchmark for the viability of economies and financial markets. This paper undertakes the task to pave the way towards further exploration of the extent by which decentralized digital monetary instruments could substitute or complement major national currencies that suffer from devaluation pressures stemming from geopolitical conflicts.

Empirical outcomes reveal that high levels of geopolitical risk are more connected with bull markets of the DeFi assets and that the emergence of new war episodes render tighter the linkages between the GPR and these innovative forms of liquidity and investment. Elevated geopolitical uncertainty combined with high inflationary pressures make the geopolitical risk acquire a major role on determining the DeFi markets. This contributes to the evolution of the existing financial landscape and its transformation into a digital cashless financial system with no central authorities. Notably, Maker is the leading force in the effort of decentralized finance assets to gain popularity in investors preferences and constitute a promising successor of national fiat currencies that suffer from devaluation in times of crises rooted in war conflicts.

The remainder of this study is structured as follows. Section 2 provides the literature review about the relation of geopolitical risk with money and inflation, the financial markets in general and digital currencies specifically. Section 3 presents an overview of the main geopolitical events in the period examined with the Russo-Ukrainian War at the epicenter. We proceed to such an analysis because we believe that this contributes to a better understanding and interpretation of the variables selected and the econometric results presented in the following Sections 4 and 5. Section 4 describes the data and the methodological frameworks employed for econometric estimations. Section 5 illustrates the empirical results, and provides the econometric analysis and the economic underpinnings of the outcomes. Finally, Section 6 concludes and suggests avenues for further research as regards the impacts of GPR on the real economy and financial markets.

2 Literature Review

So far, there is an emerging literature which connects the geopolitical risk of a country to various economic aspects regarding its overall macroeconomic performance. Due to space limitations and because of the specialization of our paper we cannot reproduce here all the variety of this literature, thus, we have chosen to reproduce a special and characteristic part of it, which deals with how the GPR affects financial markets and their institutions, an argument which we also support in this paper.

2.1 GPR and Financial Markets in General

To start with, one should mention the seminal paper of Caldara and Iacoviello (2022) who argue that when the GPR of a country increases, this leads to lower investment activity and higher unemployment. In addition, Das, Kannadhasan, and Bhattacharyya (2019) provide evidence that the US geopolitical risk is less influential than the US economic policy uncertainty on emerging stock markets and that such impacts vary across countries.

These findings coincide with those of Kannadhasan and Das (2020) who have found that the GPR is presenting negative impacts on Asian emerging stock markets at lower quantiles while it presents positive effects at middle and upper quantiles. They also coincide with the findings of Choi (2022) who studied the impact of global geopolitical risks on stock market volatilities of South Korea, China, and Japan and found that they have a strong interdependence with global geopolitical risks. They also abide by the recent findings of Lee (2024) who by employing a TVP-VAR model has studied the impact of geopolitical risk from North Korea on the stock market linkages of Northeast Asia, namely South Korea, China, and Japan. What is also important, because it is also related to the discussion we made in Section 3, it was found that North Korea’s nuclear threats negatively affected South Korean and Japanese stock markets respectively. In the same vein, Yilmazkuday (2024) investigates the effects of global geopolitical risk on stock prices of 29 economies and finds that a positive unit shock of global geopolitical risk reduces stock prices.

Moreover, Demir and Danisman (2021) have found that geopolitical uncertainty should be blamed for significantly inferior impacts on bank performance than economic policy uncertainty in 19 countries. Ivanovski and Hailemariam (2022) on their part, argue for a positive impact of geopolitical risk on oil market values across 16 countries. This is consistent with the findings of earlier studies as those performed by Antonakakis et al. (2017), Su et al. (2020) and Ozcelebi and Tokmakcioglu (2022). Yilanci and Kilci (2021) on their part detect no causal linkages stemming from geopolitical risk toward the markets of precious metals, while Huang, Suleman and Zhang (2023), in a similar study use a nonparametric causality-in-quantiles approach, investigating the causal relationship between the gold market and geopolitical risks, using high-frequency data. They reveal that geopolitical risks affected volatility rather than returns in the gold market.

Finally, in a recent research of Ngo, Van Nguyen and Hoang (2024) who explored the influence of geopolitical risks on national reserves and resource management strategies across 108 countries from 1990 to 2021, it is demonstrated that geopolitical risks adversely influence a country’s ability to accumulate total reserves relative to its external debt. This further indicates considerable challenges in resource management amid geopolitical instability.

2.2 The Nexus Between GPR, Money and Inflation

Regarding the more specific relationship between geopolitical risk, money and inflation, Iyke, Phan and Narayan (2022) support that geopolitical uncertainty is influential for international currency values. Aisen and Veiga (2008) similarly argue that high geopolitical instability can cause higher inflation. Aysan et al. (2019) using the BSGVAR technique illustrate that GPR has predictive power on both the returns and volatility of Bitcoin. Al Mamun et al. (2020) find that Bitcoin investors can only hedge their portfolio with gold, not with other financial assets and conclude that the effect of geopolitical risk, global and US economic policy uncertainty is far more significant during unfavorable economic conditions.

Adeosun et al. (2022) on their part study the interaction of economic policy uncertainty, GPR, and inflation in USA, Canada, the UK, Japan, and China and reveal that when inflation increases excessively, it causes inefficiencies, dampens society’s welfare, and triggers geopolitical tensions. Colon et al. (2021) display that the cryptocurrency market can serve as a strong hedge against geopolitical risks in most cases, but it could be considered a weak hedge and safe haven against economic policy uncertainty during a bull market.

Additionally, Caldara et al. (2024) on their part employ data for a large panel of countries to quantify the relationship between inflation and geopolitical tensions and mainly show that geopolitical risks foreshadow high inflation, with the intensity of this effect differing across countries and historical periods. By the same reasoning, Kyriazis and Economou (2022) in their study also estimate that the Turkish geopolitical uncertainty displays significant linkages with fluctuations in the Turkish lira values against other currencies and so affects the Turkish economy during the Erdoğan administration era as a whole. Mansour-Ichrakieh and Zeaiter (2019) show that in some cases, when the geopolitical risk increases in one country (in their case, Russia), this may generate higher financial stability in another country (in Turkey according to their study). Similar findings to the above research have been found in the study of Economou and Kyriazis (2022). In addition, Bouri, Gupta and Vo (2022) examine how Bitcoin and other leading cryptocurrencies are affected by the geopolitcal risks. Using a dataset that covers the period 30 April 2013 to 31 October 2019, they detect that the price behaviour of all cryptocurrencies examined is jumpy but only Bitcoin jumps are dependent on jumps in the geopolitical risk index. Their findings complement previous studies which support that Bitcoin is a hedge against geopolitical risk. Bouri, Gkillas and Gupta (2020) illustrate that geopolitical events can push governments to adopt cryptocurrencies as a tool for circumventing sanctions or for conducting international trade.

Fang, Tang and Wang (2024) on their part, by empirically testing the dynamic risk performance of cryptocurrency assets under geopolitical risk events, and examining whether they have safe-haven properties in the face of major global external shocks, provide evidence that the volatility of cryptocurrencies should not be underestimated when investors consider hedging strategies under external shocks. Finally, Sakariyahu et al. (2024) examined the impact of uncertainty and sentiment factors on price behaviour of cryptocurrencies and estimate that economic and political uncertainty factors significantly drive crypto prices.[1]

2.3 GPR, the Russo-Ukrainian War and Their Impact on Digital Currencies

Abakah et al. (2023) argue that geopolitical events such as the Russo-Ukranian War can create fear among investors due to market sentiment, leading to panic sales and thus sharp reductions in cryptocurrency returns. Moreover, according to Singh, Bansal and Bhardwaj (2022), the Russo-Ukrainian conflict confrontation had a real impact on financial markets. They trace both long and short-term mutual dependence between economic policy uncertainty (EPU), GPR, and Bitcoin returns and their findings show that Bitcoin could be linked to future uncertainties in economies, thus presenting risk in terms of the currency being used as a safe-haven investment. In a similar study, Kamal and Wahlstrøm (2023), examine the reactions of the cryptocurrency market to two events that occurred during the escalation of the Russo-Ukrainian War in February 2022 and reveal that the escalation exerted a negative influence on both liquidity and returns.

In the same vein, Hossain, Al Masum and Saadi (2024) study the connection between geopolitical risks and foreign exchange markets using the Russo-Ukrainian conflict, and support that due to intensified geopolitical risks, the conflict had a negative effect on foreign exchange rates. Nouir and Hamida (2023) find that the nexus between uncertainty and bitcoin volatility changes according to different factors and that US uncertainty has short run effects on Bitcoin volatility, while China’s uncertainty has rather long run effects. Similar findings have also been reached by the recent studies of Shamima et al. (2023), Tiwari et al. (2024) and Khalfaoui, Gozgor, and Goodell (2024).

3 Main Incidents that Affected the Geopolitical Risk at the Global Level During the 2021–2024 Period

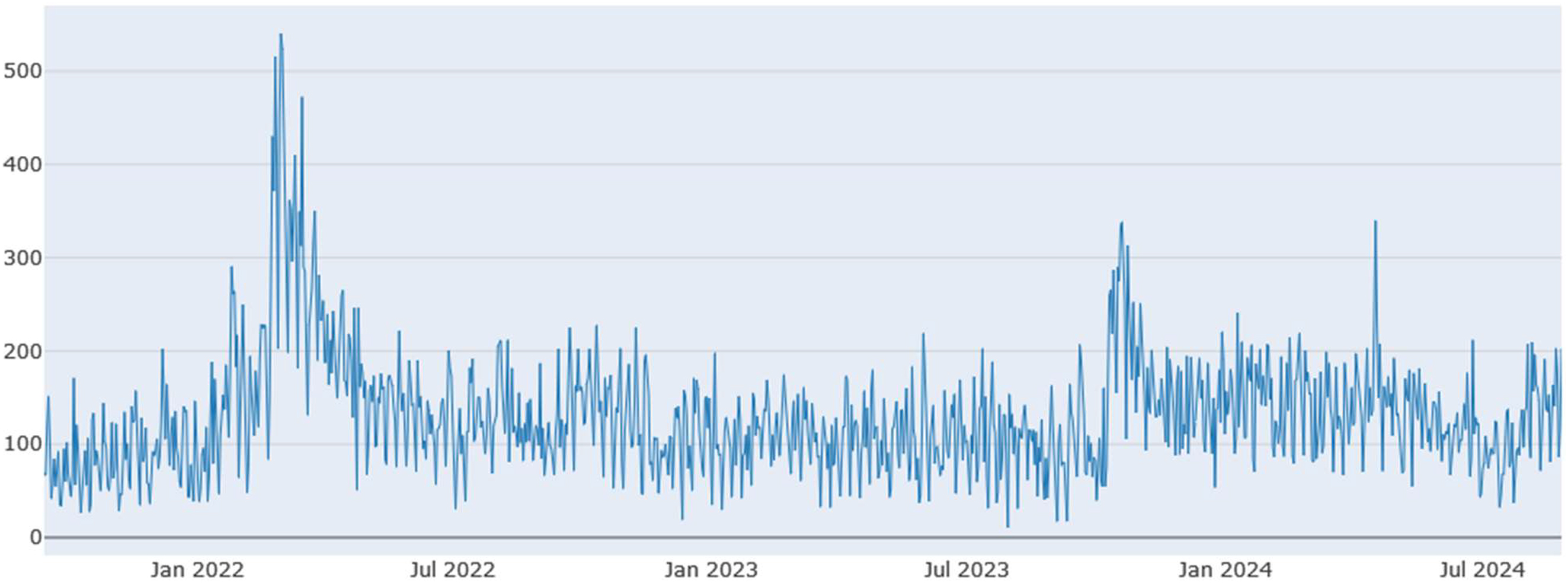

Figure 1 displays the Geopolitical Risk at the global level (Global GPR) as extracted by the Caldara and Iacoviello Index for the September 2021 to August 2024 period of time. The Caldara and Iacoviello (2022) GPR index reflects automated text-search results of the electronic archives of 10 newspapers: Chicago Tribune, the Daily Telegraph, Financial Times, The Globe and Mail, The Guardian, the Los Angeles Times, The New York Times, USA Today, The Wall Street Journal, and The Washington Post.

Global GPR based on Caldara and Iacoviello (2022). Source: https://www.policyuncertainty.com/gpr.html.

A cautious observation of Figure 1 displays a series of fluctuations in the global GPR as depicted by a series of spikes. Among them, three large spikes are observed, which appear to have a more intense impact on global GPR. The first one is observed during the end of 2021 and the start of 2022. The second is observed during the last months of 2023 and the last one during the spring of 2024.

Below we make an attempt to link these spikes to a series of important geopolitical events. At this point, it must be clarified that the following analysis which deals with the connection between the Global GPR index and the main international geopolitical events, generally applies for the entire period under scrutiny (September 2021 to August 2024). What we tentatively recognize is that the intensity of the influence of these events varies from sub-period to sub-period, hence the appearance of three large spikes throughout the period under scrutiny, compared to many smaller spikes that are also observed throughout this period as a whole. In other words, except the Russian invasion in Ukraine (February 2022) or the recent Israeli – Hamas and Israeli – Iranian conflicts (April 2024) respectively, which should be considered as key events influencing the Global GPR index, other critical facts that affected the period examined are also analyzed in brief below.[2]

Firstly, the uncertainties that humanity continued to experience at the international level, caused by the global Covid-19 pandemic, were related to economic recession and internal social strife in states around the world (for example, due to the conflict between vaccinated and unvaccinated parts of the population in most countries, etc.). Economic recession due to the pandemic was combined with the rise of inflation at alarming levels around the globe. The excessive rise of prices for goods and services were affected by the central banks decision to conduct expansionary monetary policies such as quantitative easing (QE) so as to remedy the crisis. For example, on March 15, 2020, the Fed shifted the objective of QE to supporting the economy by buying at least $500 billion in Treasury securities and $200 billion in government-guaranteed mortgage-backed securities over the months that followed.[3]

Secondly, economic recession due to Covid-19 in parallel to the Russia’s invasion to Ukraine disrupted global supply chains, creating scarcities in a wide array of goods. Thirdly, the instensificaion of climate crisis with its catastrophic consequences such as extreme weather events like heat waves that burned forests and dried up rivers, exacerbated the global crisis. Fourthly, the rising trends regarding illegal immigration flows from the East to the West should also be considered as important due to their negative socioeconomic impact on the Western recipient societies. Fifth, all the above are related to the huge and still rising imbalance regarding the distribution of wealth between rich and poor countries. Sixth, is the issue of nuclear threat. For example, Kim Jong-Un’s intentions for North Korea to develop nuclear weapons that can be delivered by long-range ballistic missiles (ICBM’s) can be highly detrimental for global order. Lee (2024) writes that according to data from the War Memorial of South Korea, over 100 missiles have been launched during Kim Jong-Un’s era, from 2012, till 2023, posing a significant threat not only to the Northeast Asia region but also to the global economy.

Bearing the above in mind, regarding the first large spike, there is no doubt that this is related to the global uncertainties that arose from the end of 2021 onwards, after the failure of the consultations between NATO and Russia in Geneva and Brussels meetings regarding the handling of the Ukrainian crisis.[4] In late 2021, Russia massed troops near Ukraine’s borders but denied any plan to attack. The failure of the negotiations led to a deadlock: on February 23, 2022 the EU and the US announced the imposition of economic sanctions on Russia, which meant the final failure of the peace talks.[5] This situation resulted in the immediate Russian invasion in Ukraine the following day (February 24, 2022). As a chain of reaction, in the afternoon of the same day, a partial military mobilization of NATO was decided. Russia on her part characterized the invasion as a “Special Military Operation” in an attempt to minimize and obfuscate what followed in the next period, which led to a full-fledged war that still takes place at the time of writing.

Except for the Ukrainian War, geopolitical risk at the planetary level has been further affected during this period by additional important events, such as the so-called 2022 Kazakh unrest, that is related to Russia’s dynamic military intervention in Kazakhstan so as to help the pro-Russian Kazakhstan’s government to suppress massive protests after a sudden sharp increase in liquefied petroleum gas prices. It should be considered certain that this event has left its mark in terms of uncertainty in the global arena as Kazakhstan is a country with a production of 1,700,000 barrels of oil per day, which also produces a large amount of uranium, and is considered to be an important component of the Chinese “Silk Road”.[6]

One has to also bear in mind that in the meantime, at the Pacific, another escalation that could lead to uncontrollable situations began to flare up again, when Chinese military exercises that began on August 2022, initiated the so-called Fourth Taiwan Strait Crisis. In particular, this crisis was sparked off by the US Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi who paid a visit to Taipei. Just after this, as a sign of power and determination, the Chinese Navy launched a series of unprecedented military exercises around Taiwan, provoking the so-called Fourth Taiwan Strait Crisis.[7] This could, of course, lead to further escalation that might even result in (as a worst case scenario) an open military confronation that could involve, in a domino style scenario, many powerful (in economic and military terms) states that have interests in the area, including the key players China, Taiwan and USA, as well as others, such as Japan, Australia and the United Kingdom,[8] South Korea, North Korea and Russia etc. Characteristically, the Taiwan Strait could be the place where the world’s two biggest powers may fight a war.

A second very large spike in Figure 1 is observed towards the end of 2023. There is no doubt that this is related to the so-called Israel and Hamas War, started in October 2023. It is considered as the most significant military engagement in the region since the Yom Kippur War in 1973. As of November 2024, over 43,000 Palestinians have been killed, many of them civilians.[9] At the time of writing over 100 Israeli hostages are still held by Hamas. The conflict has caused widespread devastation and a severe humanitarian crisis in the region.What is more, is that unless the appropriate wise diplomatic manipulations are taken, this conflict could lead to a very dangerous domino in the Middle East, with the involvement of other countries as well, such as Iran, Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, etc.

The second large spike in Figure 1 is directly related to the third large spike which appears in the end of spring 2024. Obviously, this is linked with the Israeli – Iranian conflict. In particular, on April 13, 2024 Iran launched a series of retaliatory attacks against Israel with loitering munitions, cruise and ballistic missiles and drones, in response to the Israeli bombing of the Iranian embassy in Damascus on April 1, which led to the death of two Iranian generals.[10] After the intervention of leaders from around the globe, who asked Israel not to counter strike but to show self-reliance, a costly all-out war was avoided. Van Veen and Touval (2024) have recently published a paper which explains four conflict scenarios that capture the main dynamics of conflict between Israel and the US. What is for sure, is that various experts argue that this conflict creates further serious geopolitcal uncertainties of a global impact.[11]

In paraller to these events, in June 2023, during the Russian invasion to Ukraine, Ukraine launched a counteroffensive against Russian forces who occupied its territory. After Ukraine liberated large swathes of its territory in late 2022, such as large areas in Donetsk and Zaporizhzhia oblasts (regions), President Putin estimated that the war is “going to take a while” and warned of the “increasing” threat of nuclear war. He clearly implied the use of Tactical Nuclear Weapons.[12] This direct threat, has of course an obvious impact on the Global GPR. It is more that certain that if Russia would decide to escalate as much as using also the nuclear option, this would have been a critical threat for global peace and security.[13] Putin repeated these threats in June 2024 when he declared:

For some reason, the West believes that Russia will never use it … We have a nuclear doctrine, look what it says. If someone’s actions threaten our sovereignty and territorial integrity, we consider it possible for us to use all means at our disposal. This should not be taken lightly, superficially.[14]

“All means”, of course, implies also the usage of nuclear weapons, either tactical or strategic (the latter as a last choice). This is of high importance, since according to the official Russian Military Doctrine, Russia “considers nuclear weapons to be exclusively a means of deterrence” and: “The doctrine deems the use of nuclear weapons an “extreme and compelled measure”. “The doctrine also emphasizes deterrence of aggression by the Russian military strength including its nuclear weapons”.[15] The above mean that if any area of Russian territory is threatened, nuclear weapons could be an option. We believe that the third sharp large spike that is observed in the GGPR of Figure 1 is directly related to this type of recent threats.

As a sequence of this escalation of both warfare and threats, in early August 2024, Ukraine launched a surprise attack on the Kursk oblast (a Russian territory), capturing dozens of towns and villages in recent weeks. At the time of writing (November 2024) it appears that the Ukranian counter-offensive at Kursk has significantly degenerated. The Russian forces have managed to push back Ukrainian troops from several settlements they had previously captured. But what is important regarding our discussion to this point, is that the Ukranian counteroffensive at Kursk gave the Russian political leadership the opportunity to proceed with readjustments of its official doctrine regarding the usage of nuclear weapons.

Putin announced that the threshold for using nuclear weapons has been lowered. The updated doctrine now includes scenarios where Russia might use nuclear weapons in response to conventional attacks that pose a “critical threat” to its sovereignty, especially if these attacks involve the participation or support of nuclear forces. This change is seen as an attempt to deter Western involvement in the conflict and to signal greater willingness to escalate if necessary.[16]

The last verse is open to many interpretations and the Russian high command can use it as they see fit. For example, they may claim that the Ukrainian offensive on the Russian territory (Kursk) is also linked to the killing of civilians, which directly threatens the very existence of the Russian Federation, so the Russian military leadership is morally justified to also consider the nuclear option (for example, tactical nuclear missiles).

After all, already since February 24, 2022, President Putin threatened Western leaders not to further intervene in Ukraine, otherwise, their intervention would result in consequences “such as you have never seen in your entire history.” This is, of course, a direct threat which implies that the Russian leadership will not hesitate to use, if necessary, devastating nuclear weapons.[17]

All the uncertainties as mentioned above, and especially, the very serious threat of using nuclear weapons have obviously related to the third large sharp spike that is observed regarding the Global GPR, that appeared near the end of spring 2024. What is for sure, is that the above geopolitical developments and especially, the Russian invasion in Ukraine have caused the World Order to decline (Lee 2024; Park 2022). Furthermore, they have once more highlighted the nexus between political, military, economic effects, deterrence strategies and the security dilemmas regarding the global balance of power (Morales, Rajmil and O’Callaghan 2023).[18]

4 Data and Methodology

For the purposes of estimations, closing daily values of the global geopolitical risk and eleven popular DeFi digital currencies are employed that cover the period from 13 October 2021 (abiding by data availability of the DeFi assets) to 19 October 2024. The DeFi assets are represented by the following digital currencies: Chainlink, Uniswap, Internet Computer, Aave, Maker, Synthetix, Compound, 0× Protocol, yearn finance, Sushiswap and Loopring which enjoy a decentralized digital character with no regulatory obstacles and are considered to be bubbly so are attractive to risky investors. Geopolitical risk in a worldwide extent is expressed by the daily values of the innovative global geopolitical risk (GPR) index developed by Caldara and Iacoviello (2022). Thereby, the Russia-Ukraine geopolitical tensions expressed by armed conflicts are examined as well as the rest of the geopolitical events presented in Section 3. All quotes are denominated in US dollars. Logarithmic differences are used to reflect the alterations in GPR and the returns of the investments considered. The GPR index is sourced from the policyuncertainty.com database while the DeFi market values are downloaded from the coinmarketcap.com database.

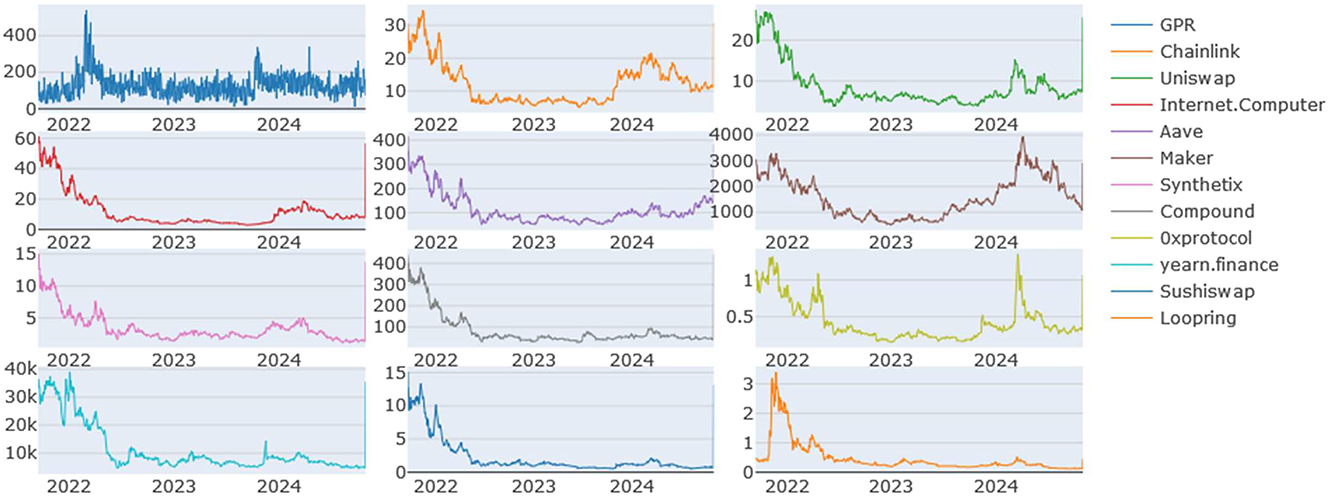

Figure 2 displays the time evolution of GPR and DeFi values. Geopolitical risk presents its highest levels at the onset of the Russia-Ukraine conflict in early 2022. Notably, the large majority of the digital currencies illustrate bear tendencies during the war and the high inflationary pressures while some of them slightly rebound in the summer of 2024. Interestingly, Loopring displays a large increase in prices when the war begins and decreases thereafter.

Values of the geopolitical risk and the DeFi assets.

Table 1 provides the descriptive statistics of the global geopolitical risk and each of the eleven DeFi assets considered. GPR is extremely unstable and this is more evident at the outbreak of the Russia-Ukraine conflict. It is obvious that Sushiswap (1.47) is the most profitable DeFi investment and Synthetix (0.757) and Compound (0.735) follow while Maker (0.161) is the least profitable digital asset on average but displays periods of abrupt rises in performance. Sushiswap (2,799.567) is also the most volatile assets whereas Maker (44.094) displays the weakest fluctuations and is considered to be the safest investment. All DeFi assets are demonstrated to be positively skewed and leptokurtic. Non-normality in all variables is corroborated by the Jarque–Bera test. The ERS test displays that the majority of variables are stationary in logarithmic differences.

Descriptive statistics of logarithmic differences of the GPR and each of the DeFi assets.

| Mean | StdDev | Skewness | Ex.Kurtosis | JB | ERS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GPR | 14.412 | 8,127.461 | 9.964*** | 156.437*** | 1,182,348*** | −15.352*** |

| Chainlink | 0.169 | 47.681 | 14.283*** | 361.473*** | 6,250,716*** | −10.573*** |

| Uniswap | 0.224 | 72.447 | 17.370*** | 459.352*** | 10,088,893*** | −3.179 |

| Internet computer | 0.512 | 372.988 | 30.059*** | 973.287*** | 45,207,465*** | −1.813* |

| Aave | 0.184 | 46.86 | 9.864*** | 216.665*** | 2,250,289*** | −3.284*** |

| Maker | 0.161 | 44.094 | 12.851*** | 304.141*** | 4,429,096*** | −4.123*** |

| Synthetix | 0.757 | 732.885 | 31.254*** | 1,025.41*** | 50,174,106*** | −1.672* |

| Compound | 0.735 | 767.104 | 31.976*** | 1,057.493*** | 53,359,845*** | −2.099** |

| 0× Protocol | 0.261 | 81.092 | 15.393*** | 385.150*** | 7,097,417*** | −7.630*** |

| yearn.finance | 0.506 | 389.541 | 30.769*** | 1,004.439*** | 48,144,742*** | −2.237** |

| Sushiswap | 1.47 | 2,799.567 | 33.117*** | 1,108.307*** | 58,606,139*** | −1.173 |

| Loopring | 0.318 | 110.933 | 17.657*** | 461.766*** | 10,196,493*** | −3.808*** |

-

Notes: ***, ** and * display significance at 1 %, 5 % and 10 %, respectively; Skewness: D’Agostino (1970) test; Kurtosis: Anscombe and Glynn (1975) test; JB: Jarque and Bera (1980) normality test; ERS: Stock, Elliott, and Rothenberg (1996) unit-root test with constant.

The methodological framework employed for estimations with three innovative specifications is the Quantile Vector Autoregression (QVAR) approach as in Kyriazis et al. (2024) is presented in (1):

where y t and y t−j constitute k × 1 dimensional endogenous variable vectors, τ takes values between zero and unity and stands for the quantile investigated, p represents the lag length of the Quantile-VAR model, μ(τ) is a conditional mean vector with k × 1 dimensions, Φ j (τ) is the Q-VAR coefficient matrix of k × k dimensions while u t (τ) is the error vector of k × 1 dimensions featured by a variance-covariance matrix of k × k dimensions, denoted as Σ(τ).

The spillover impact that an innovation in variable i causes on variable j is:

where e i is a zero vector taking the value of 1 on the ith position. This normalization leads to:

When it comes to the joint directional connectedness TO variables, this is the joint effect generated from variable i towards the group of the remaining variables j:

Reversely, the spillover effect that the group of the remaining variables j causes on variable i is the joint directional connectedness FROM others:

So their difference is the net joint connectedness from variable i towards the group of the remaining variables j:

In addition, the adjusted Total Connectedness Index (TCI) of Chatziantoniou, Gabauer and Stenfors (2021) takes values between zero and unity to reflect market systemic risk. Higher values of TCI indicate stronger systemic connectedness and higher market risk

Estimations of dynamic linkages reveal how this nexus alters over time and enable the assessment of the spillover impacts that GPR generates on the markets of DeFi assets or the reverse. Pairwise, joint and network examinations permit a multi-spectral analysis and allow valuable insights into how geopolitical risk can influence the adoption of decentralized finance vehicles and the transition to the cashless economy by the adoption of alternatives for traditional fiat currencies. Therefore, the detection and measurement of difficultly-discernible connectedness could provide a compass for examining the impacts of GPR on monetary economics and macro-finance.

5 Econometric Results

Econometric estimations are conducted by the Quantile-VAR methodology at the lower (5th), middle (50th) and upper (95th) quantiles by a 30-day rolling window and 10-day forecast horizon. The lower quantile represents low geopolitical risk and bear DeFi markets, the middle quantile stands for normal GPR and middle values of the return distributions of DeFi returns while the upper quantile reflects elevated geopolitical uncertainty and bull DeFi markets. Outcomes are generated by the net pairwise directional connectedness to examine dynamic relation in pairs of GPR and separate DeFi assets but also by the net extended joint connectedness to estimate how and by which extent the GPR is jointly connected with the group of DeFi currencies and to better discern its impacts on systemic risk. Moreover, the network connectedness outcomes reveal whether and by which magnitude the GPR or specific DeFi assets serve as sources or receivers of spillover impacts from each of the remaining constituents of the system.

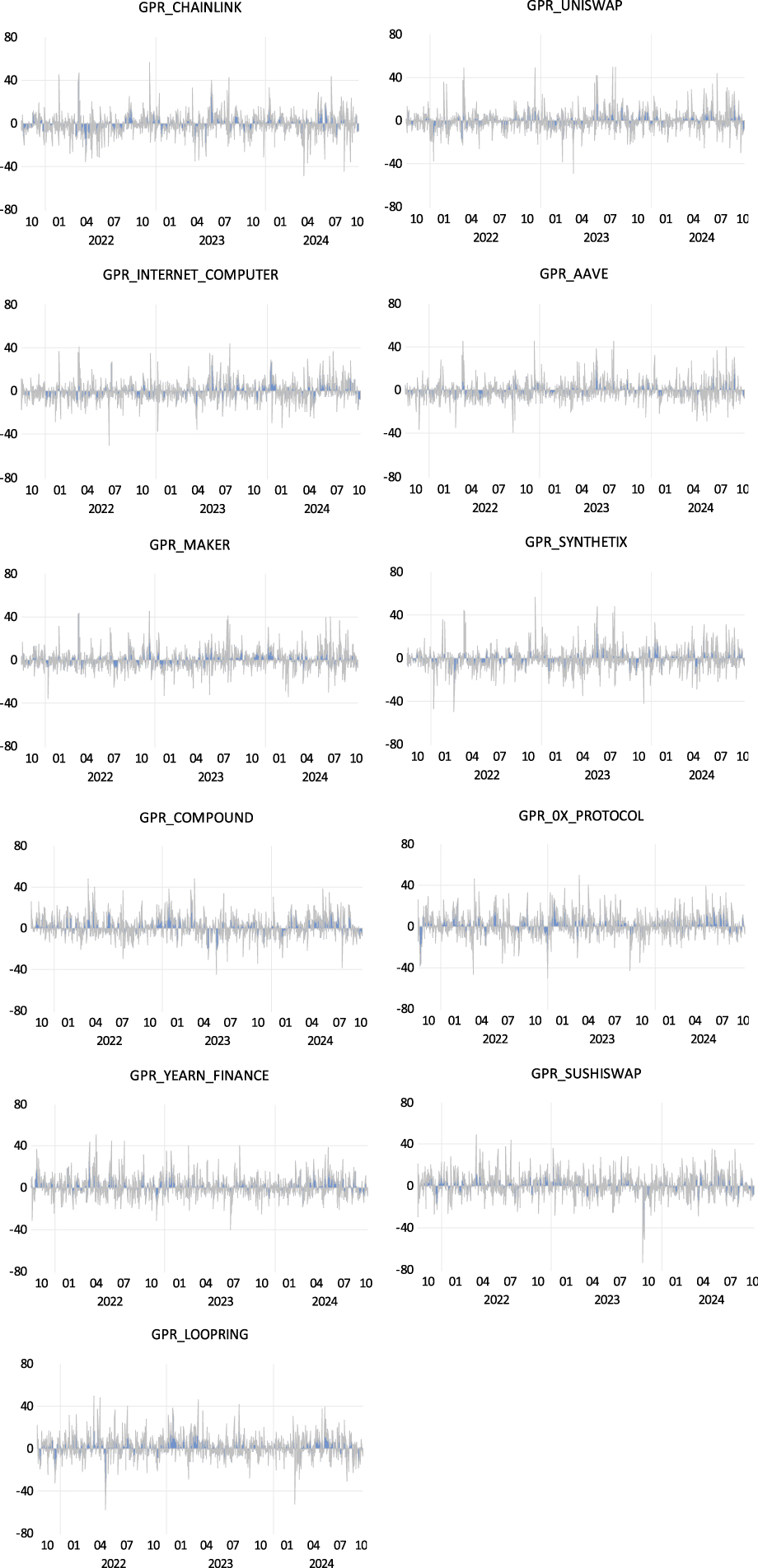

5.1 Net Pairwise Directional Connectedness

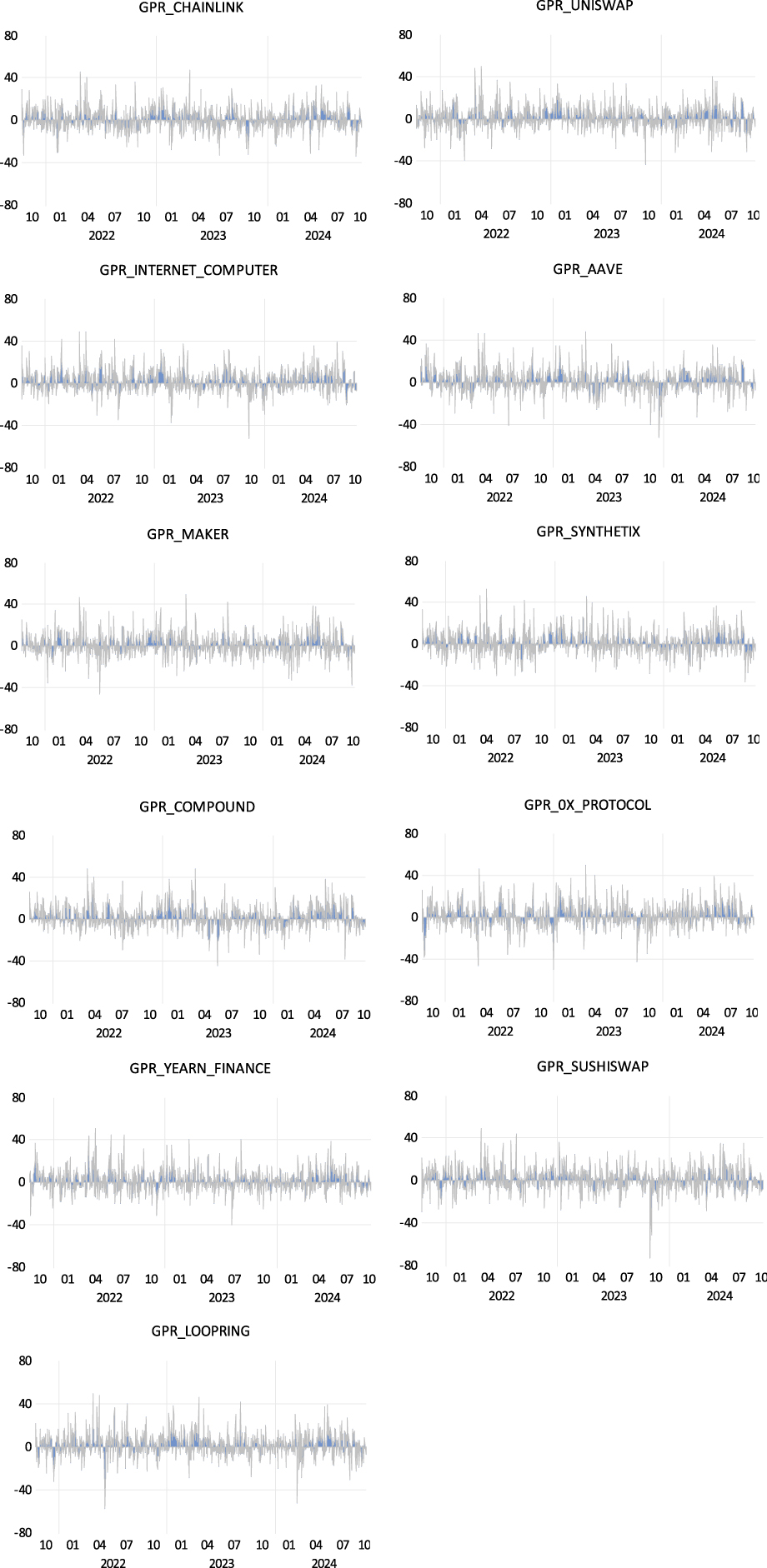

Figures 3a–3c present the net pairwise directional connectedness at the lower, middle and upper quantiles, respectively. The vertical axis shows the level of net pairwise directional connectedness while the horizontal axis displays the time. It is obvious that geopolitical risk is weakly to modestly linked with each of the DeFi assets considered at the lower quantile. Their connection presents spikes at the onset of the Russia-Ukraine conflict (early 2022) and this is repeated when new intense war episodes appear in middle 2023. On average, these spikes do not exceed the level of 50 while in general the relation is less than 40 in the remaining period. Remarkably, these linkages become tighter since mid-2024 even though no presence of large spikes can be found. The emergence of intense Middle-Eastern conflicts combined with the already accumulated geopolitical uncertainty and inflationary pressures render the GPR influential on decentralized digital markets in a more permanent basis.

Net pairwise directional connectedness between the GPR and each of the DeFi assets at the lower (5th) quantile. Note: The name on each graph denotes the pair of variable whose net pairwise directional relation is examined. The vertical axis illustrates the level of net pairwise directional connectedness and the horizontal axis shows the time. Areas with a positive sign inform that the GPR is a net generator of pairwise directional connectedness to the respective DeFi asset while areas with a negative sign inform that the GPR is a net receiver from the DeFi asset.

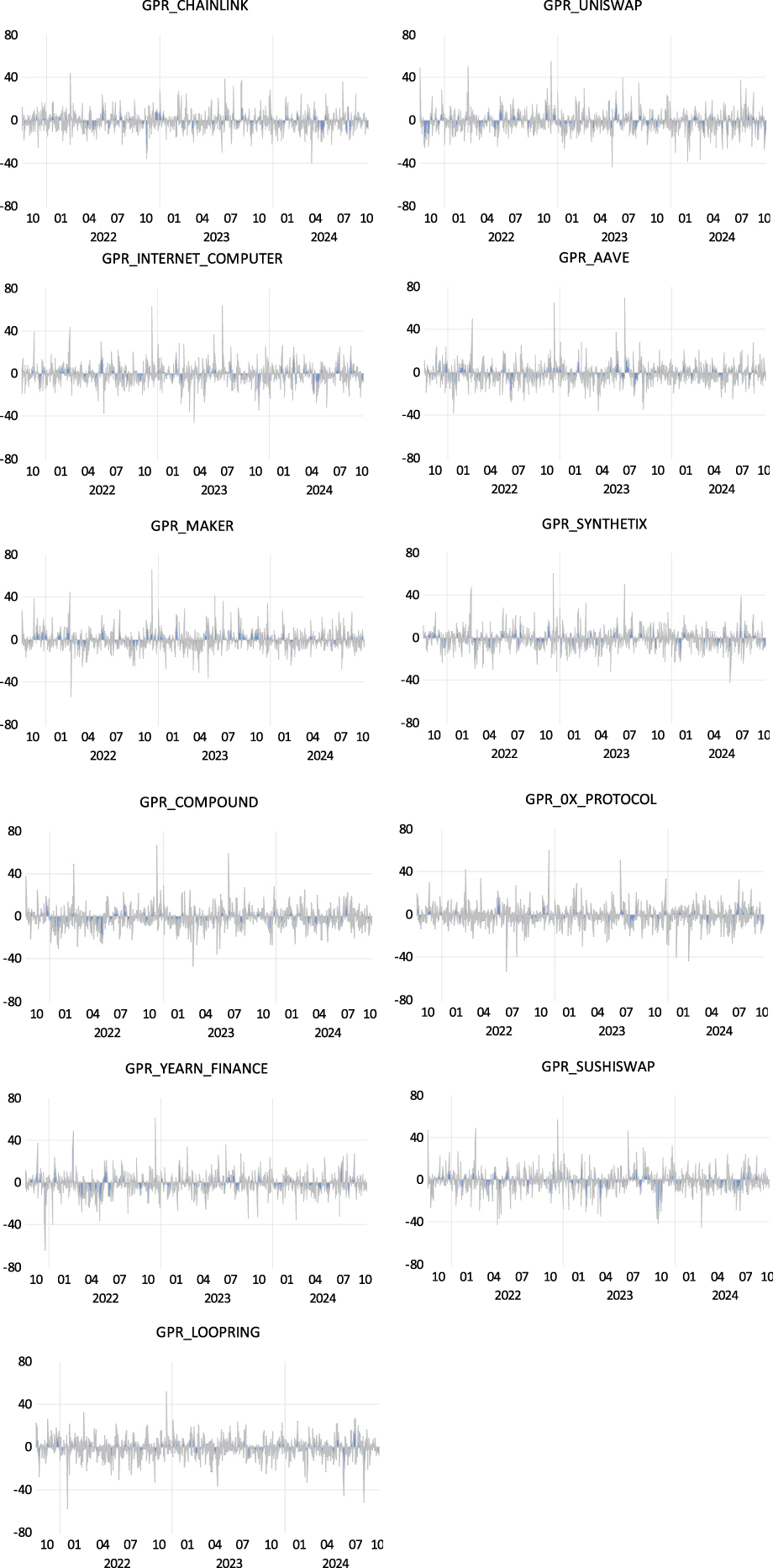

Contrary to what could be expected, examination at the middle quantile (Figure 3b) does not bring about significant decreases in the connectedness between GPR and each of the DeFi markets. The linkages between GPR and each of the constituents of the DeFi group are weak but a non-negligible number of upwards or downwards spikes in the net pairwise connectedness are found. This indicates that even in normal conditions, geopolitical tensions interact with modern financial markets and shocks in the former could result in spillovers on the latter or the reverse. The majority of DeFi assets are shown to be influenced by the GPR by more than 40 at several points of time.

Net pairwise directional connectedness between the GPR and each of the DeFi assets at the middle (50th) quantile. Note: The name on each graph denotes the pair of variable whose net pairwise directional relation is examined. The vertical axis illustrates the level of net pairwise directional connectedness and the horizontal axis shows the time. Areas with a positive sign inform that the GPR is a net generator of pairwise directional connectedness to the respective DeFi asset while areas with a negative sign inform that the GPR is a net receiver from the DeFi asset.

As concerns the upper quantile (Figure 3c), lower spikes but significantly more systematic and permanent connectedness of geopolitical tensions and each of the DeFi assets are revealed. The connectedness hardly reaches the level of 50 in most cases but clearly displays consistency and does not fade out. This indicates that when geopolitical stress is high and alternative forms of money and investment are profitable then the GPR plays a pivotal role in the development of sophisticated decentralized digital assets’ markets. This corroborates the notion that geopolitically-induced uncertainty leads to instability in the traditional financial system and paves the way for the transition to the new digital financial markets with bubbly investment vehicles.

Net pairwise directional connectedness between the GPR and each of the DeFi assets at the middle (95th) quantile. Note: The name on each graph denotes the pair of variable whose net pairwise directional relation is examined. The vertical axis illustrates the level of net pairwise directional connectedness and the horizontal axis shows the time. Areas with a positive sign inform that the GPR is a net generator of pairwise directional connectedness to the respective DeFi asset while areas with a negative sign inform that the GPR is a net receiver from the DeFi asset.

5.2 Net Extended Joint Connectedness

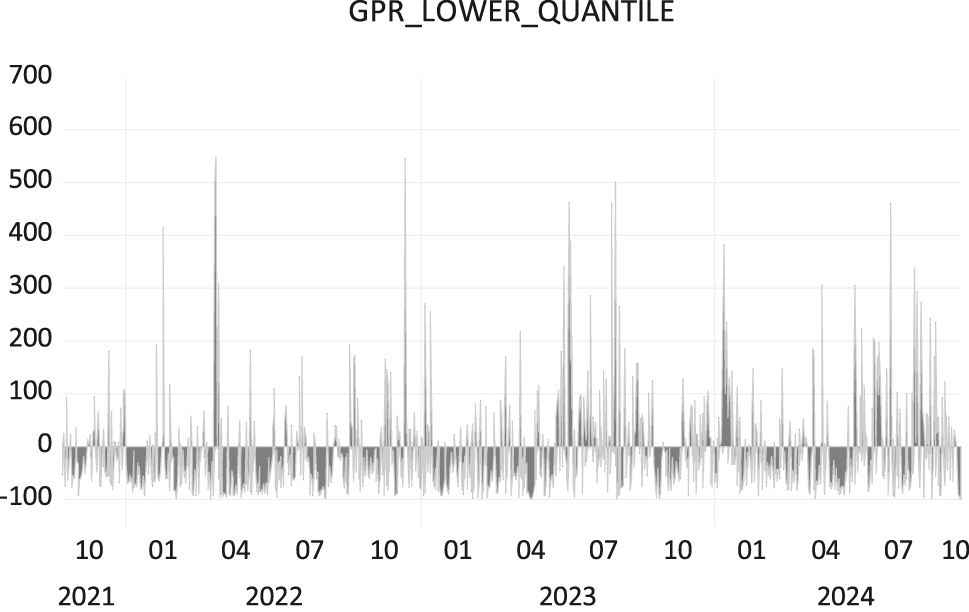

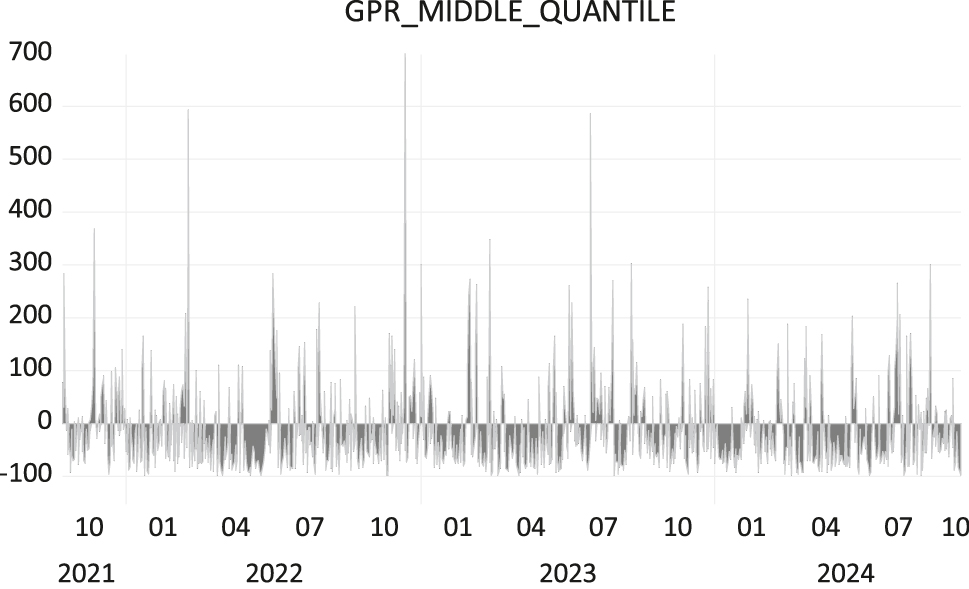

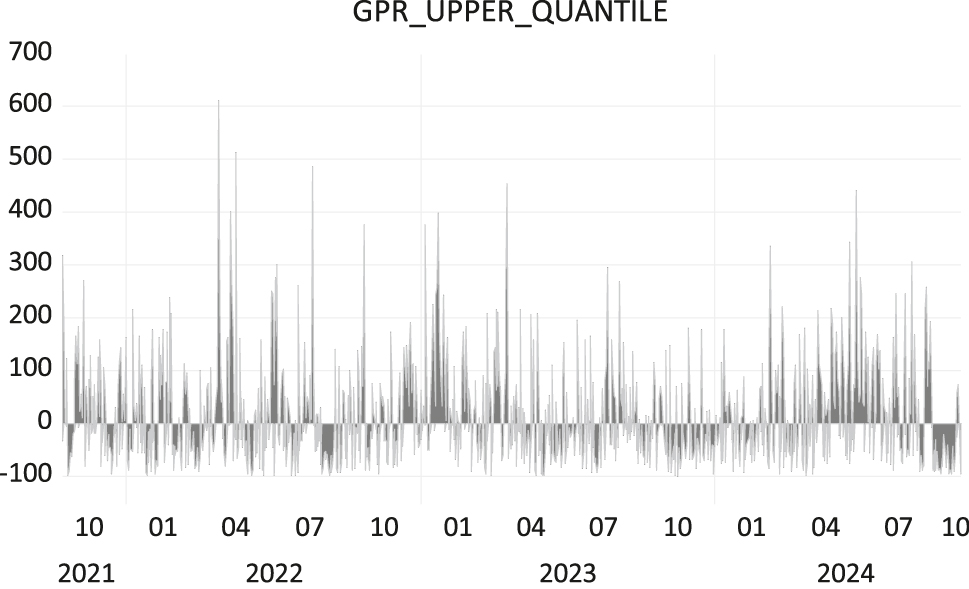

Estimations of the net extended joint connectedness between the GPR and the group of DeFi assets at the lower, middle and upper quantiles are displayed in Figure 4 and demonstrate interesting findings.

In terms of higher precision, the lower quantile (Figure 4a), which represents low geopolitical risk and bear DeFi markets, is found to be very strongly influential on digital investments just after the onset of the Russia-Ukraine conflict. This fortifies the notion that war-induced uncertainty is of major importance for markets of innovative digital forms of money and investment and the unanticipated shock of new geopolitical crises constitutes a driver of evolution concerning the transition to a new cashless digital economy. GPR also proves to affect DeFi assets in later phases of the war (early 2023) and this probably works through the signaling and confidence channels of economic policymaking by reducing the optimistic sentiment and consequently the willingness of consumers and investors to hold national currencies.

Net extended joint connectedness between the geopolitical risk index and the group of DeFi assets at the lower (5th) quantile. Note: The name on each graph indicates the quantile at which the GPR is examined regarding its joint connectedness with the group of the DeFi assets, the vertical axis reveals the level of net extended joint connectedness and the horizontal axis stands for the time. Areas with a positive sign show that the GPR constitutes a net source of extended joint connectedness to the group of the DeFi assets while areas with a negative sign mean that the GPR is a net receiver from the group.

Notably, geopolitical risk presents considerable impacts on the DeFi assets during the spring and the summer of 2024 and this reveals how accumulated inflationary pressures in tandem with elevated geopolitical risk can form a period of persistent GPR effects on the markets of decentralized digital currencies. This nourishes the belief that when the GPR repeatedly affects the economy both directly and indirectly – via the increases of price levels through the supply chain channel – the connection of geopolitical risk and modern financial markets becomes stronger and tends to be permanent.

Examination at the middle quantile (Figure 4b) indicates that normal levels of GPR and middle values in the distributions of the DeFi returns display weak connectedness. This relationship though strengthens as time evolves and war episodes along with inflation accumulate the burden for financial markets. Thereby, the combination of the Russia-Ukraine war episodes and the Middle East conflicts (in late 2023 and 2024) results into the GPR being impactful on digital currency markets who could serve as a shield from the menace of inflation that both these wars bring about.

Net extended joint connectedness between the Geopolitical Risk Index and the group of DeFi assets at the middle (50th) quantile Note: The name on each graph indicates the quantile at which the GPR is examined regarding its joint connectedness with the group of the DeFi assets The vertical axis reveals the level of net extended joint connectedness and the horizontal axis stands for the time. Areas with a positive sign show that the GPR constitutes a net source of extended joint connectedness to the group of the DeFi assets while areas with a negative sign mean that the GPR is a net receiver from the group.

Intriguingly, results at the upper quantile (Figure 4c) reveal substantially stronger connectedness between GPR and the DeFi assets than at the lower and the middle quantiles. It is worth emphasizing that this connection remains powerful during all the war period examined. This relation becomes stronger when new war episodes emerge in early 2023 as this lowers the confidence of consumers and investors in fiat national money holdings but does not act favorably for digital currencies either. This happens because the latter are considered to be too risky to invest in times of so elevated geopolitical and monetary uncertainty. Notably though, the dynamic linkages between the GPR and the DeFi assets render strong and persistent at the same time since early 2024 and continue this way until the early autumn of 2024. This is combined with the amelioration of performance in the majority of the DeFi assets and especially regarding the Maker, 0× Protocol. Chainlink and Uniswap which constitute the leading vehicles of the DeFi popularity in investor preferences. Even though the performance of the DeFi decreases later in 2024, the connection with the GPR during elevated geopolitical risk and bull DeFi markets remains strong. This sets the basis for further geopolitical and inflationary impactful spillovers on the formation of a solid clientele for investments in the form of decentralized finance.

Net extended joint connectedness between the Geopolitical Risk Index and the group of DeFi assets at the upper (95th) quantile Note: The name on each graph indicates the quantile at which the GPR is examined regarding its joint connectedness with the group of the DeFi assets The vertical axis reveals the level of net extended joint connectedness and the horizontal axis stands for the time. Areas with a positive sign show that the GPR constitutes a net source of extended joint connectedness to the group of the DeFi assets while areas with a negative sign mean that the GPR is a net receiver from the group.

Geopolitical stress and national currency devaluation when combined serve as a catalyst for the ability of the DeFi assets to crowd out–from the perceptions of economic agents-national currencies as the only acceptable means of money and investments. Thereby, geopolitical tensions and monetary instability work for fueling the transition to the cashless digital economy where decentralized digital currency would be the means of sheltering from external shocks and wealth loss.

5.3 Network Connectedness

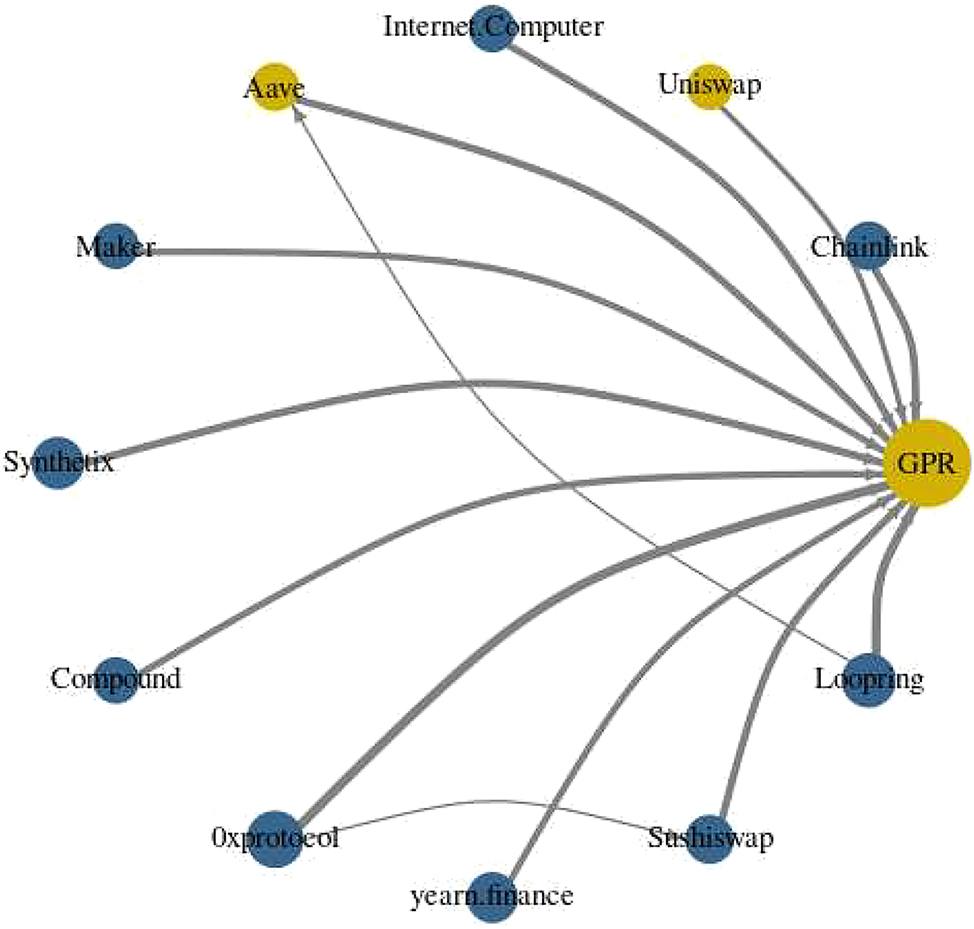

The dynamic interlinkages between the GPR and the group of DeFi constituents are also examined by the network connectedness specification. Figure 5a presents estimations at the lower quantile. It is demonstrated that nine out of the eleven DeFi assets examined function as net sources of spillover impacts. Notably, geopolitical risk fails to serve as a net contributor of impacts to any of the DeFi assets. Moreover, it is obvious that the DeFi assets are not related with each other by a considerable extent.

Network connectedness between the GPR and DeFi assets at the lower (5th) quantile.

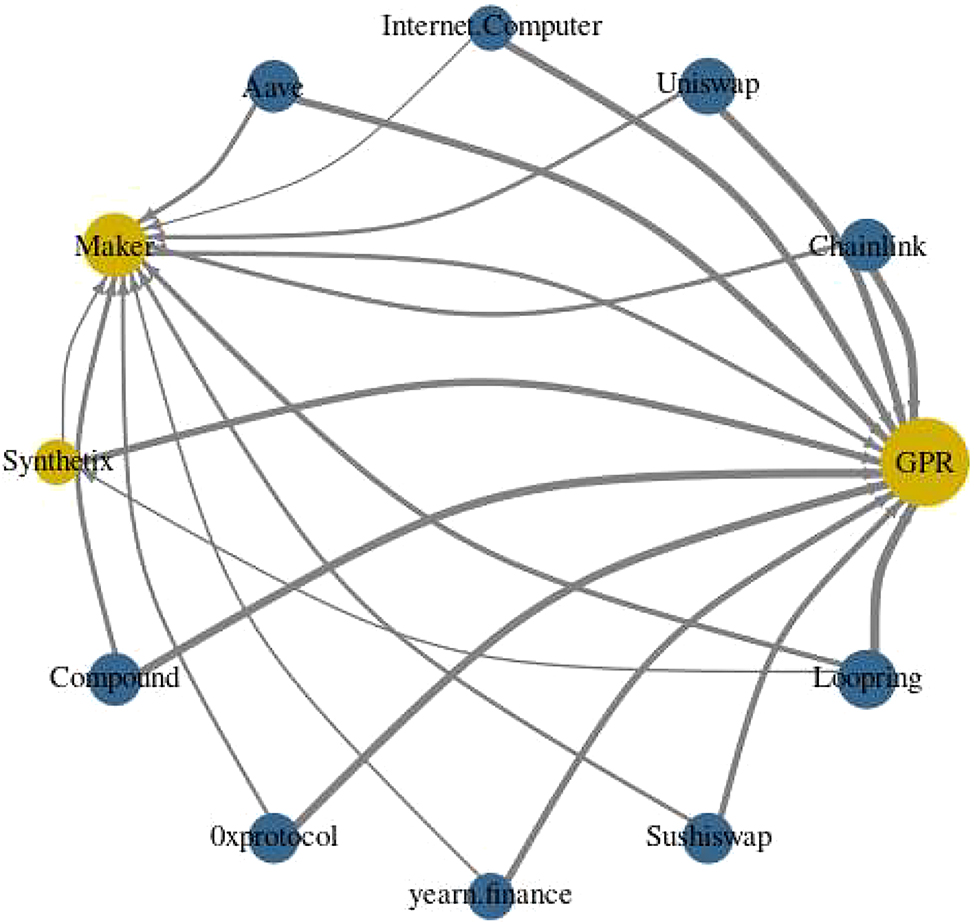

Connectedness at the middle quantile (Figure 5b) displays that nine out of eleven DeFi currencies work as net contributors of spillovers and GPR is clearly a net receiver of impacts. The Maker and Synthetix currencies are the net receivers of spillovers, in contrast with the lower quantile where Uniswap and Aave were the net DeFi receivers in the system. Interconnectedness among constituents of the system is much more evident than at the lower quantile. Remarkably, the Maker is linked with each one of the remaining DeFi assets and this indicates that it has a pivotal role in the functioning of the DeFi markets overall.

Network connectedness between the GPR and DeFi assets at the middle (50th) quantile.

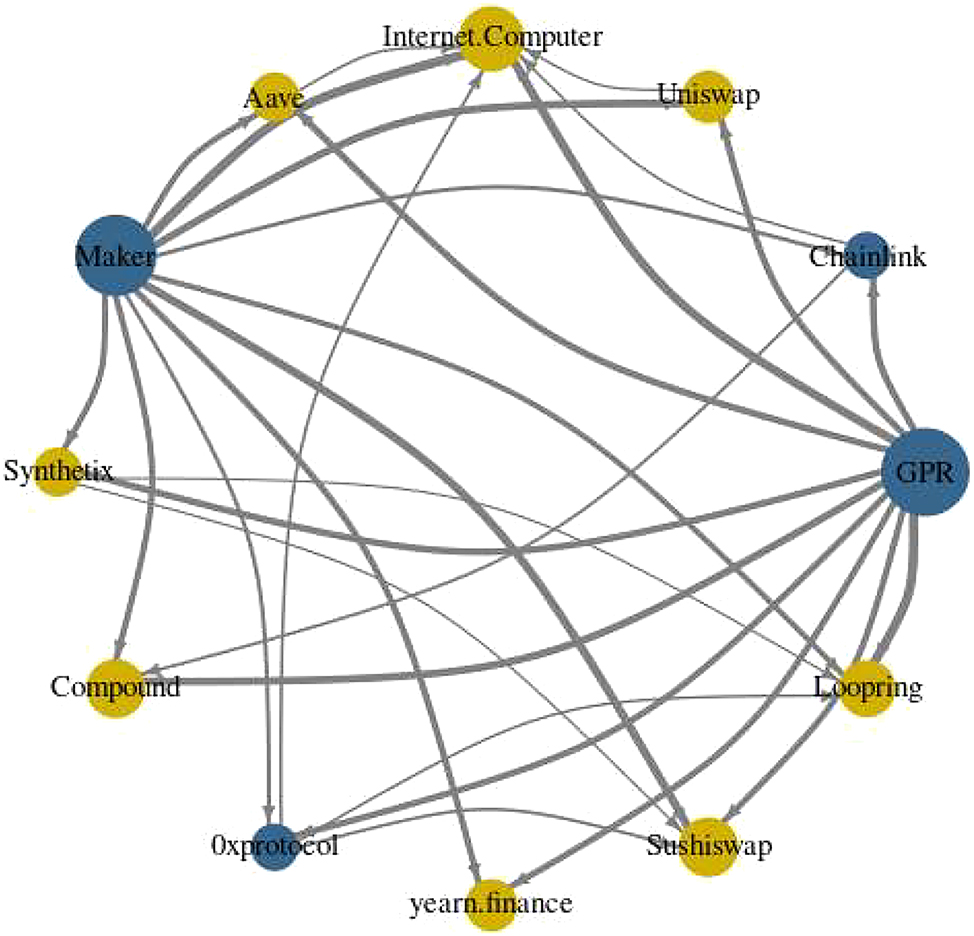

When it comes to estimations at the upper quantile (Figure 5c), some striking changes in dynamic linkages are traced. In contrast to findings at the lower and middle quantiles, geopolitical risk functions as a net source of spillover effects on the DeFi markets and is strongly connected with the great majority of them. Eight out of eleven DeFi assets work as net receivers of innovations from other sources. Intriguingly, the Maker becomes the second strongest generator of spillovers, following the GPR, and proves to be influential on all the remaining DeFi investments. Market risk as presented by the level of interlinkages is found to be considerably higher than at the lower and middle quantiles. It is noteworthy that in conditions of very high geopolitical risk and bull tendencies in DeFi markets – as expressed by the upper quantile – the GPR becomes an influential determinant of evolution in the DeFi markets. The combination of highly stressed geopolitical and monetary conditions – translated into high GPR and inflation – gives birth to a new leader in the market of the DeFi assets that plays the role of the adjustor of systemic risk in the decentralized digital currency markets. In other words, high geopolitical uncertainty and its monetary consequences contribute to the creation of a strong alternative currency that considerably adjusts the markets of the remaining DeFi assets.

Network connectedness between the GPR and DeFi assets at the upper (95th) quantile.

The Maker and other leading DeFi assets could prove to be very useful as devices to complement or substitute existing national currencies in an economic environment where the majority of consumers and investors are eager to re-allocate portfolios towards innovative, inflation-proof and promising profit-making investments. The emergence of a leading DeFi asset that could be used for avoiding strict central authority mandates and the obligation to abide by monetary and banking regulation could act as the cornerstone for the transformation of the financial system into digital and frictionless. Thereby, in times of elevated geopolitical stress and high pressures for the exploitation of profitable investments for counteracting the inflation-resuscitated waves of devaluation, Maker – which is the safest among the DeFi – or other DeFi digital currencies could function as the cornerstone for financial stability and as the foundations of the connection between GPR and the transformation of the financial system.

It could be argued that geopolitical risk constitutes a determinant of evolution in the field of monetary economics and macro-finance. Geopolitical risk pushes towards the transformation of the existing monetary and financial framework into a cashless digital landscape that abides by the necessity for lowering costs and providing eligibility in transactions and protection from the proliferating number of financial instability sources.

6 Conclusions

Unveiling the role of geopolitical uncertainty on the formation of economic and monetary policymaking is of primary interest in modern eras where externalities result into high levels of instability in the real economy and financial markets through inflationary phenomena which nourish serious loss of purchasing power, impoverishment and societal inequalities. This paper sets under scrutiny the dynamic connectedness of global geopolitical risk and decentralized finance (DeFi) assets – which could constitute modern and highly promising successors of fiat currencies – through the prism of dynamic spillovers both separately and jointly. This academic study aspires to contribute towards better understanding whether and by which extent geopolitical tensions could function as a driver of evolution of the current traditional financial landscape into a cashless digital financial system with higher eligibility and lower costs. This investigation provides insights into how war-induced inflation could lead to the establishment of new forms of liquidity in consumers’ and investors’ perceptions and as means for sheltering from devaluation and wealth loss. The contribution of this study is that it paves the way for future research into the potential replacement or supplementation of major national currencies that are subject to inflation consequence resulting from geopolitical conflicts through the use of digital decentralized monetary instruments.

Three advanced specifications – the net pairwise directional connectedness, the net extended joint connectedness and the network connectedness – of the modern Quantile-VAR framework are adopted with daily data spanning 13 October 2021 to 29 October 2024 to examine the interplay of GPR with decentralized unregulated finance in the Russo-Ukrainian war period. Empirical results indicate that bull markets of DeFi assets are more closely associated with high levels of geopolitical risk, and the introduction of new war episodes strengthens the connections between the GPR and these cutting-edge forms of investment and liquidity. High inflationary pressures and elevated geopolitical uncertainty cause geopolitical risk to become a significant factor in shaping the DeFi markets. This aids in the current financial landscape’s development and its transition toward a digital, cashless, central authority-free financial system. Notably, Maker is the driving force behind the push for decentralized financial assets to become more popular with investors and to emerge as a viable alternative to national fiat currencies that depreciate during war-related crises. Thereby, the Maker or alternative DeFi assets could act not only as the proof but also as the foundations of the connectedness of GPR with the evolution of the financial system.

This study renders possible for academics and interested readers in the fields of geopolitics, monetary economics and macro-finance to achieve a deeper understanding on the potential of geopolitical risk to reformulate financial markets and provide a boost for their digital cashless evolution with no constraints imposed by central authorities. This connection is examined through the prism of inflation, caused by war, which threatens to turn fiat national currencies into outdated forms for transactions and store of value. Our findings provide a compass on how geopolitical risk could prove to be a major driver of the evolution in the fields of monetary economics and finance.

Further research on this promising field that links geopolitics with economics and finance could include investigating of the connection of GPR with other types of financial investments and estimating how this could be influential on the purchasing capacity, the wealth levels and investor sentiment of economic agents.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to express their many thanks to the Editor and to the reviewers for their very productive comments and suggestions.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors declare that there are no conflicting interests.

-

Data availability: All data employed are available upon request.

References

Abakah, E. J. A., D. Adeabah, A. K. Tiwari, and M. Abdullah. 2023. “Effect of Russia-Ukraine War Sentiment on Blockchain and FinTech Stocks.” International Review of Financial Analysis 90: 102948. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.irfa.2023.102948.Search in Google Scholar

Adeosun, O. A., M. I. Tabash, X. V. Vo, and S. Anagreh. 2022. “Uncertainty Measures and Inflation Dynamics in Selected Global Players: A Wavelet Approach.” Quality and Quantity 57: 3389–424. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-022-01513-7.Search in Google Scholar

Afonso, A., M. G. Arghyrou, M. D. Gadea, and A. Kontonikas. 2018. ““Whatever it Takes” to Resolve the European Sovereign Debt Crisis? Bond Pricing Regime Switches and Monetary Policy Effects.” Journal of International Money and Finance 86: 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jimonfin.2018.04.005.Search in Google Scholar

Aisen, A., and F. J. Veiga. 2008. “Political Instability and Inflation Volatility.” Public Choice 135 (3): 207–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-007-9254-x.Search in Google Scholar

Al Mamun, M., G. S. Uddin, M. T. Suleman, and S. H. Kang. 2020. “Geopolitical Risk, Uncertainty and Bitcoin Investment.” Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications 540: 123107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physa.2019.123107.Search in Google Scholar

Anscombe, F. J., and W. J. Glynn. 1975. Distribution of the Kurtosis Statistic B 2 for Normal Samples. Virginia: Defense Technical Information Center.Search in Google Scholar

Antonakakis, N., R. Gupta, C. Kollias, and S. Papadamou. 2017. “Geopolitical Risks and the Oil-Stock Nexus Over 1899–2016.” Finance Research Letters 23: 165–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.frl.2017.07.017.Search in Google Scholar

Aysan, A. F., E. Demir, G. Gozgor, and C. K. M. Lau. 2019. “Effects of the Geopolitical Risks on Bitcoin Returns and Volatility.” Research in International Business and Finance 47: 511–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ribaf.2018.09.011.Search in Google Scholar

Balestra, A., R. Caruso, and M. Di Domizio. 2024. “What Explains the Size of Sovereign Wealth Funds? A Panel Analysis (2008–2018).” Finance Research Letters 62: 105200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.frl.2024.105200.Search in Google Scholar

Baur, D. G., and L. A. Smales. 2020. “Hedging Geopolitical Risk with Precious Metals.” Journal of Banking & Finance 117: 105823. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2020.105823.Search in Google Scholar

Bouri, E., K. Gkillas, and R. Gupta. 2020. “Trade Uncertainties and the Hedging Abilities of Bitcoin.” Economic Notes 49 (3): e12173. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecno.12173.Search in Google Scholar

Bouri, E., R. Gupta, and X. V. Vo. 2022. “Jumps in Geopolitical Risk and the Cryptocurrency Market: The Singularity of Bitcoin.” Defence and Peace Economics 33 (2): 150–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/10242694.2020.1848285.Search in Google Scholar

Caldara, D., and M. Iacoviello. 2022. “Measuring Geopolitical Risk.” The American Economic Review 112 (4): 1194–225. https://doi.org/10.17016/ifdp.2018.1222.Search in Google Scholar

Caldara, D., S. Conlisk, M. Iacoviello, and M. Penn. 2022. “Do Geopolitical Risks Raise or Lower Inflation.” Federal Reserve Board of Governors 1–34, https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4852461.Search in Google Scholar

Caldara, D., S. Conlisk, M. Iacoviello, and M. Penn. 2024. “Do Geopolitical Risks Raise or Lower Inflation.” https://www.matteoiacoviello.com/research_files/GPR_INFLATION_PAPER.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

Caruso, R. 2011. “On the Nature of Peace Economics.” Peace Economics, Peace Science and Public Policy 16 (2): 1–13. https://doi.org/10.2202/1554-8597.1216.Search in Google Scholar

Caruso, R. 2017. “Peace Εconomics and Peaceful Economic Policies.” The Economics of Peace and Security Journal 12 (2): 16–20. https://doi.org/10.15355/epsj.12.2.16.Search in Google Scholar

Caruso, R., and A. Biscione. 2022. “Militarization and Income Inequality in European Countries (2000–2017).” Peace Economics, Peace Science and Public Policy 28 (3): 267–85. https://doi.org/10.1515/peps-2022-0026.Search in Google Scholar

Chatziantoniou, I., D. Gabauer, and A. Stenfors. 2021. “Interest Rate Swaps and the Transmission Mechanism of Monetary Policy: A Quantile Connectedness Approach.” Economics Letters 204: 109891. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2021.109891.Search in Google Scholar

Chen, H., and P. L Siklos. 2022. “Central Bank Digital Currency: A Review and Some Macro-Financial Implications.” Journal of Financial Stability 60: 100985.10.1016/j.jfs.2022.100985Search in Google Scholar

Chen, Q., A. Filardo, D. He, and F. Zhu. 2016. “Financial Crisis, US Unconventional Monetary Policy and International Spillovers.” Journal of International Money and Finance 67: 62–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jimonfin.2015.06.011.Search in Google Scholar

Chiang, T. C. 2022. “The Effects of Economic Uncertainty, Geopolitical Risk and Pandemic Upheaval on Gold Prices.” Resources Policy 76: 102546. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2021.102546.Search in Google Scholar

Chiu, J., and M. Molico. 2010. “Liquidity, Redistribution, and the Welfare Cost of Inflation.” Journal of Monetary Economics 57 (4): 428–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmoneco.2010.03.004.Search in Google Scholar

Choi, S. Y. 2022. “Evidence from a Multiple and Partial Wavelet Analysis on the Impact of Geopolitical Concerns on Stock Markets in North-East Asian Countries.” Finance Research Letters 46: 102465. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.frl.2021.102465.Search in Google Scholar

Colon, F., C. Kim, H. Kim, and W. Kim. 2021. “The Effect of Political and Economic Uncertainty on the Cryptocurrency Market.” Finance Research Letters 39: 101621.10.1016/j.frl.2020.101621Search in Google Scholar

Cukierman, A. 2013. “Monetary Policy and Institutions Before, During, and After the Global Financial Crisis.” Journal of Financial Stability 9 (3): 373–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfs.2013.02.002.Search in Google Scholar

D’Agostino, R. B. 1970. “Transformation to Normality of the Null Distribution of g1.” Biometrika 57: 679–81.10.1093/biomet/57.3.679Search in Google Scholar

Das, D., M. Kannadhasan, and M. Bhattacharyya. 2019. “Do The Emerging Stock Markets React to International Economic Policy Uncertainty, Geopolitical Risk and Financial Stress Alike?” The North American Journal of Economics and Finance 48: 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.najef.2019.01.008.Search in Google Scholar

Demir, E., and G. O. Danisman. 2021. “The Impact of Economic Uncertainty and Geopolitical Risks on Bank Credit.” The North American Journal of Economics and Finance 57: 101444. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.najef.2021.101444.Search in Google Scholar

Dimitriadis, K. A., D. Koursaros, and C. S. Savva. 2024a. “The Influence of the “Environmental-Friendly” Character Through Asymmetries on Market Crash Price of Risk in Major Stock Sectors.” Journal of Climate Finance 9: 100052. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.irfa.2024.103693.Search in Google Scholar

Dimitriadis, K. A., D. Koursaros, and C. S. Savva. 2024b. “Evaluating the Sophisticated Digital Assets and Cryptocurrencies Capacities of Substituting International Currencies in Inflationary Eras.” International Review of Financial Analysis 96: 103693. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.irfa.2024.103693.Search in Google Scholar

Dimitriadis, K. A., D. Koursaros, and C. S. Savva. 2024c. “The Influential Impacts of International Dynamic Spillovers in Forming Investor Preferences: A Quantile-VAR and GDCC-GARCH Perspective.” Applied Economics: 1–21. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.5052174.Search in Google Scholar

Economou, E. M. L., and N. A. Kyriazis. 2022. “Spillovers Between Russia’s and Turkey’s Geopolitical Risk During the 2000–2021 Putin Administration.” Peace Economics, Peace Science and Public Policy 28 (1): 29–50. https://doi.org/10.1515/peps-2021-0021.Search in Google Scholar

Fang, Y., Q. Tang, and Y. Wang. 2024. “Geopolitical Risk and Cryptocurrency Market Volatility.” Emerging Markets Finance and Trade: 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/1540496X.2024.2343948.Search in Google Scholar

Gabauer, D. 2020. “Volatility Impulse Response Analysis for DCC-GARCH Models: The Role of Volatility Transmission Mechanisms.” Journal of Forecasting 39 (5): 788–96. https://doi.org/10.1002/for.2648.Search in Google Scholar

Hong, Y., Y. Jiang, X. Su, and C. Deng. 2024. “Extreme State Media Reporting and the Extreme Stock Market During COVID-19: A Multi-Quantile VaR Granger Causality Approach in China.” Research in International Business and Finance 67: 102143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ribaf.2023.102143.Search in Google Scholar

Hossain, A. T., A. A. Masum, and S. Saadi. 2024. “The Impact of Geopolitical Risks on Foreign Exchange Markets: Evidence from the Russia–Ukraine war.” Finance Research Letters 59: 104750.10.1016/j.frl.2023.104750Search in Google Scholar

Huang, J., Y. Li, M. T. Suleman, and H. Zhang. 2023. “Effects of Geopolitical Risks on Gold Market Return Dynamics: Evidence from a Nonparametric Causality-in-Quantiles Approach.” Defence and Peace Economics 34 (3): 308–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/10242694.2021.2007333.Search in Google Scholar

Ivanovski, K., and A. Hailemariam. 2022. “Time-Varying Geopolitical Risk and Oil Prices.” International Review of Economics & Finance 77: 206–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iref.2021.10.001.Search in Google Scholar

Iyke, B. N., D. H. B. Phan, and P. K. Narayan. 2022. “Exchange Rate Return Predictability in Times of Geopolitical Risk.” International Review of Financial Analysis 81: 102099. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.irfa.2022.102099.Search in Google Scholar

Jarque, C. M., and A. K. Bera. 1980. “Efficient Tests for Normality, Homoscedasticity and Serial Independence of Regression Residuals.” Economics Letters 6 (3): 255–9.10.1016/0165-1765(80)90024-5Search in Google Scholar

Kamal, M. R., and R. R. Wahlstrøm. 2023. “Cryptocurrencies and the Threat Versus the Act Event of Geopolitical Risk.” Finance Research Letters 57: 104224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.frl.2023.104224.Search in Google Scholar

Kannadhasan, M., and D. Das. 2020. “Do Asian Emerging Stock Markets React to International Economic Policy Uncertainty and Geopolitical Risk Alike? A Quantile Regression Approach.” Finance Research Letters 34: 101276. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.frl.2022.103365.Search in Google Scholar

Khalfaoui, R., G. Gozgor, and J. W. Goodell. 2024. “Impact of Russia-Ukraine War Attention on Cryptocurrency: Evidence from Quantile Dependence Analysis.” Finance Research Letters 52: 103365. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.frl.2022.103365.Search in Google Scholar

Kollias, C., S. Papadamou, and A. Stagiannis. 2011. “Terrorism and Capital Markets: The Effects of the Madrid and London Bomb Attacks.” International Review of Economics & Finance 20 (4): 532–41.10.1016/j.iref.2010.09.004Search in Google Scholar

Koop, G., M. H. Pesaran, and S. M. Potter. 1996. “Impulse Response Analysis in Nonlinear Multivariate Models.” Journal of Econometrics 74 (1): 119–47.10.1016/0304-4076(95)01753-4Search in Google Scholar

Kyriazis, N. A., and E. M. L. Economou. 2022. “The Impacts of Geopolitical Uncertainty on Turkish Lira During the Erdoğan Administration.” Defence and Peace Economics 33 (6): 731–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/10242694.2021.1904200.Search in Google Scholar

Kyriazis, N. A., and E. M. L. Economou. 2023. “Multi-Faceted US Uncertainty Connectedness with Domestic and Global Geopolitical Risk.” Journal of Financial Economic Policy 16 (1): 1–18.10.1108/JFEP-05-2023-0136Search in Google Scholar

Kyriazis, N., S. Papadamou, P. Tzeremes, and S. Corbet. 2024. “Quantifying Spillovers and Connectedness Among Commodities and Cryptocurrencies: Evidence from a Quantile-VAR Analysis.” Journal of Commodity Markets 33: 100385. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcomm.2024.100385.Search in Google Scholar

Lee, G. 2024. “The Impact of North Korean Nuclear Threat on Stock Market Linkages in Northeast Asia: The Case of South Korea, China, and Japan.” Finance Research Letters 66: 105727. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.frl.2024.105727.Search in Google Scholar

Li, C., W. Zhang, X. Huang, and J. F. Zhang. 2024. “Geopolitical Risks, Institutional Environment, and Food Price Inflation.” Applied Economics: 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2024.2386853.Search in Google Scholar

Makarov, I., and A. Schoar. 2022. “Cryptocurrencies and Decentralized Finance (DeFi).” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 2022 (1): 141–215. https://doi.org/10.1353/eca.2022.0014.Search in Google Scholar

Mansour-Ichrakieh, L., and H. Zeaiter. 2019. “The Role of Geopolitical Risks on the Turkish Economy Opportunity or Threat.” The North American Journal of Economics and Finance 50: 101000. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.najef.2019.101000.Search in Google Scholar

Maouchi, Y., L. Charfeddine, and G. El Montasser. 2022. “Understanding Digital Bubbles Amidst the COVID-19 Pandemic: Evidence from DeFi and NFTs.” Finance Research Letters 47: 102584. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.frl.2021.102584.Search in Google Scholar

Mishkin, F. S. 2009. “Is Monetary Policy Effective During Financial Crises?” The American Economic Review 99 (2): 573–7. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.99.2.573.Search in Google Scholar

Morales, L., D. Rajmil, and A. B. O’Callaghan. 2023. “Navigating the Ukraine War: Unraveling the Interplay of Geoeconomics, Geopolitics and Deterrence.” Peace Review: A Journal of Social Justice: 663–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/10402659.2023.2262408.Search in Google Scholar

Ngo, V. M., P. Van Nguyen, and Y. H. Hoang. 2024. “The Impacts of Geopolitical Risks on Gold, Oil and Financial Reserve Management.” Resources Policy 90: 104688. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2024.104688.Search in Google Scholar

Nouir, J. B., and H. B. H. Hamida. 2023. “How Do Economic Policy Uncertainty and Geopolitical Risk Drive Bitcoin Volatility?” Research in International Business and Finance 64: 101809. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ribaf.2022.101809.Search in Google Scholar

Ozcelebi, O., and K. Tokmakcioglu. 2022. “Assessment of the Asymmetric Impacts of the Geopolitical Risk on Oil Market Dynamics.” International Journal of Finance & Economics 27 (1): 275–89. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijfe.2151.Search in Google Scholar

Papadamou, S., E. Spyromitros, and N. A. Kyriazis. 2018. “Quantitative Easing Effects on Commercial Bank Liability and Government Yields in UK: A Threshold Cointegration Approach.” International Economics and Economic Policy 15: 353–71. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10368-017-0401-7.Search in Google Scholar

Papadamou, S., N. A. Kyriazis, and P. G. Tzeremes. 2019a. “Spillover Effects of US QE and QE Tapering on African and Middle Eastern Stock Indices.” Journal of Risk and Financial Management 12 (2): 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm12020057.Search in Google Scholar

Papadamou, S., Ν. A. Kyriazis, and P. G. Tzeremes. 2019b. “Unconventional Monetary Policy Effects on Output and Inflation: A Meta-Analysis.” International Review of Financial Analysis 61: 295–305. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.irfa.2018.11.015.Search in Google Scholar

Papadamou, S., Ν. A. Kyriazis, and P. G. Tzeremes. 2020. “US Non-Linear Causal Effects on Global Equity Indices in Normal Times Versus Unconventional Eras.” International Economics and Economic Policy 17: 381–407. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10368-019-00457-y.Search in Google Scholar

Papadamou, S., C. Siriopoulos, and N. A. Kyriazis. 2020. “A Survey of Empirical Findings on Unconventional Central Bank Policies.” Journal of Economic Studies 47 (7): 1533–77. https://doi.org/10.1108/jes-04-2019-0186.Search in Google Scholar

Park, P. 2022. “Russian Invasion of Ukraine and the Decline of the World Order.” Journal of East Asian Affairs 35 (1): 135–65.Search in Google Scholar

Pesaran, H. H., and Y. Shin. 1998. “Generalized Impulse Response Analysis in Linear Multivariate Models.” Economics Letters 58 (1): 17–29.10.1016/S0165-1765(97)00214-0Search in Google Scholar

Sakariyahu, R., R. Lawal, R. Adigun, A. Paterson, and S. Johan. 2024. “One Crash, Too Many: Global Uncertainty, Sentiment Factors And Cryptocurrency Market.” Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money 94: 102028.10.1016/j.intfin.2024.102028Search in Google Scholar

Salisu, A. A., L. Lasisi, and J. P. Tchankam. 2022. “Historical Geopolitical Risk and the Behaviour of Stock Returns in Advanced Economies.” The European Journal of Finance 28 (9): 889–906. https://doi.org/10.1080/1351847x.2021.1968467.Search in Google Scholar

Selmi, R., J. Bouoiyour, and M. E. Wohar. 2022. ““Digital Gold” and Geopolitics.” Research in International Business and Finance 59: 101512. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ribaf.2021.101512.Search in Google Scholar

Shamima, A., A. Rima, R. M. Ramizur, and T. Fariha. 2023. “Is Geopolitical Risk Interconnected? Evidence from Russian-Ukraine Crisis.” The Journal of Economic Asymmetries 28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeca.2023.e00306.Search in Google Scholar

Singh, S., P. Bansal, and N. Bhardwaj. 2022. “Correlation Between Geopolitical Risk, Economic Policy Uncertainty, and Bitcoin Using Partial and Multiple Wavelet Coherence in P5 + 1 Nations.” Research in International Business and Finance 63: 101756. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ribaf.2022.101756.Search in Google Scholar

Stenfors, A., I. Chatziantoniou, and D. Gabauer. 2022. “Independent Policy, Dependent Outcomes: A Game of Cross-Country Dominoes Across European Yield Curves.” Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money 81: 101658. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intfin.2022.101658.Search in Google Scholar

Stock, J., G. Elliott, and T. Rothenberg. 1996. “Efficient Tests for an Autoregressive Unit Root.” Econometrica 64 (4): 813–36.10.2307/2171846Search in Google Scholar

Su, C. W., K. Khan, R. Tao, and M. Umar. 2020. “A Review of Resource Curse Burden on Inflation in Venezuela.” Energy 204: 117925. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2020.117925.Search in Google Scholar

Tiwari, M., C. Lupton, A. Bernot, and K. Halteh. 2024. “The Cryptocurrency Conundrum: The Emerging Role of Digital Currencies in Geopolitical Conflicts.” Journal of Financial Crime 31 (6): 1622–34, https://doi.org/10.1108/JFC-12-2023-0306.Search in Google Scholar

van Veen, E., and Y. Touval. 2024. Israel against Iran: Regional Conflict Scenarios in 2024, Policy Brief. Clingendael: Netherlands Institute of International Relations. https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/resrep61775.pdf?refreqid=fastly-default%3Afb5607c9e93502ec4cc15461c00b5554&ab_segments=&origin=&initiator=&acceptTC=1.Search in Google Scholar

Wang, X., Y. Wu, and W. Xu. 2019. “Geopolitical Risk and Investment.” Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking 56 (8): 2023–59, https://doi.org/10.1111/jmcb.13110.Search in Google Scholar

Wu, J. C., Y. Xie, and J. Zhang. 2024. Does Unconventional Monetary and Fiscal Policy Contribute to the COVID Inflation Surge? (No. w33044). National Bureau of Economic Research.10.3386/w33044Search in Google Scholar

Yamarik, S. J., N. D. Johnson, and R. A. Compton. 2010. “War! What is it Good for? A Deep Determinants Analysis of the Cost of Interstate Conflict.” Peace Economics, Peace Science and Public Policy 16 (1): 8–22. https://doi.org/10.2202/1554-8597.1197.Search in Google Scholar

Yang, T., Q. Dong, M. Du, and Q. Du. 2023. “Geopolitical Risks, Oil Price Shocks and Inflation: Evidence from a TVP–SV–VAR Approach.” Energy Economics 127: 107099. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eneco.2023.107099.Search in Google Scholar

Yilanci, V., and E. N. Kilci. 2021. “The Role of Economic Policy Uncertainty and Geopolitical Risk in Predicting Prices of Precious Metals: Evidence from a Time-Varying Bootstrap Causality Test.” Resources Policy 72: 102039. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2021.102039.Search in Google Scholar

Yilmazkuday, H. 2024. “Geopolitical Risk and Stock Prices.” European Journal of Political Economy 83: 102553. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2024.102553.Search in Google Scholar