Abstract

The open-ended project-in-development called Eurotales: A Museum of the Voices of Europe is an experimental online museum that is based on the underlying question of “how can one present and communicate, in museological form, the intangible culture of languages as they are and have been used across Europe?” Its response is to turn to digital technology to explore and create displays that foreground language uses as culture, as identity, and as memory. The aim is to show and explore the actual multiplexity of languages in real life, and through time and space, and to contrast this implicitly with canonical and standardizing accounts presented in histories of named languages, which are also digitally displayed. This article opens with a discussion of museums and digital collections of intangible culture and goes on to describe the thinking and design underlying the four digital collections of Eurotales. The methods of data collection for each of these are separately mentioned in their subsequent descriptions. The collections present the material traces of language as intangible culture, the lived experiences and memories of languages of individuals in the present and in the past (separately), and societies’ authorized, or canonical, memories of named languages as presented in their published histories. Eurotales is thence presented as a project that uses the superordinating and intangible nature of digital space to address and explore the equally superordinating and intangible natures of language, culture, memory, and identity.

1 Introduction

This paper presents an ongoing project that uses digital technology to explore and create various displays that foreground languages as culture, languages as identity, and languages as memory. After introducing Eurotales in summary form, the second section (§2) provides a discussion of museums and digital collections of (intangible) culture. In this and in all subsequent sections, this article includes commentary on and description of how Eurotales responds to the concepts under scrutiny, thus providing a contextualized introduction to the thinking, design, and methods of data collecting that underlie the databases upon which the museum is founded. The following section (§3) presents the digital display of language as intangible cultural heritage. The paper then (§4) considers the interactions of cultural identity and memory with our digital displays of language as intangible culture. The brief concluding section (§5) draws attention to the ways in which digital tools enable the intangibility, multiplicity, and complexity of language as cultural heritage, memory, and identity to be simultaneously shown, shared, and explored.

The experimental collaborative museum, Eurotales: A Museum of the Voices of Europe, is based at Rome Sapienza University, where its physical display site opened in 2022. The Eurotales open access web museum (available online in its preliminary stages),[1] is under construction; its expanding collections are organized and formed by four databases that were first used to generate touch-screen displays in our mixed (digital and analogue) exhibit in Rome. From its inception, the museum was designed to view and present language both as deeply entwined with other cultural and social practices, and as an inherently cultural (and intangible) possession and practice of humans. The museum’s name refers to language as voices in order to forestall any misleading implication of connections between named languages and national identities, and to introduce the concept of language exhibited as usage, not from the perspective of grammarians. The project design was formed by the challenges of collecting from scratch, and of displaying language as intangible cultural heritage, in particular a heritage of extraordinary universality and complexity. Thus, the project placed digital technologies centrally in our vision of collecting, mapping, and displaying linguistic cultures of Europe (taking the words language and culture in their fully democratized sense, to include all types and variations of languages and language uses), in their formal, geographic, and temporal multiplexity (Cannata et al 2020, 209).

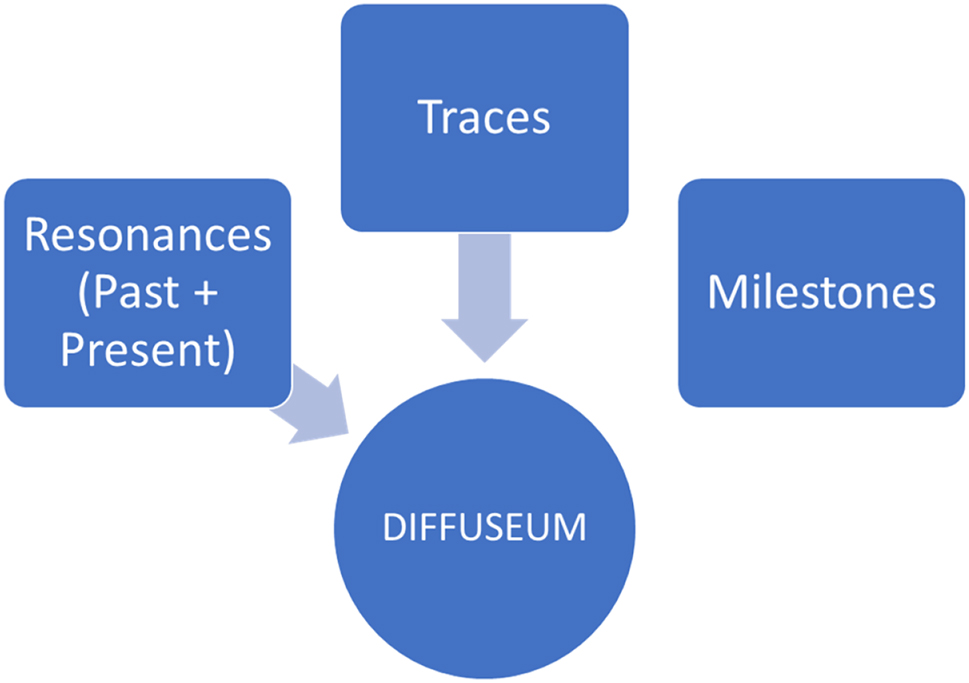

The four databases, which generate our four digital collections, are called Traces, Resonances of the Past, Resonances of the Present, and Milestones (which generate flexibly displayed timelines) (Figure 1).

Eurotales digital collections and display sites.

The graphic shows the four digital museum collections of Eurotales, two of them thematically related (the Resonance databases), that are stored in separate databases that then produce four digital exhibition-sites; in the next stage of our project, the Traces and Resonances of the Past databases will be made relational, and produce searchable output with the projected implementation of the Diffuseum, a fifth display website, and the basis for a related mobile app.

The Traces exhibit displays geographically situated items, mapped, illustrated and explained, that are physical evidence of languages used in that place for stated purposes and within stated time periods. Each trace is material evidence of a nexus between geographically situated culture and language, mostly signalled by a material object. Our two Resonances collections produce displays that show how the many languages of Europe resonate now, and in the past, with and through people. Both collections include items relating to language, cultural memory, and identity, showing that people’s first, or even their main, languages are not always the ones that we would expect from their countries of birth or residence; they use the examples of famous people from the past, and self-reported information from thousands of present-day contributors, to drive forward the point that many languages inhabit individual places, and many individuals speak and use more than one language. A less entangled picture of languages in time is provided by the Milestones collection, which produces digital timelines of named languages; each timeline presents the canonical history of one language, which is an encoding of the recognized and standardized cultural memory of languages. These timelines stand in implicit dialogue with the other collections and their displays, that tell very different tales of the linguistic cultures of Europe.

2 Culture and Digital Museums

A museum is a not-for-profit, permanent institution in the service of society that researches, collects, conserves, interprets and exhibits tangible and intangible heritage. Open to the public, accessible and inclusive, museums foster diversity and sustainability. They operate and communicate ethically, professionally and with the participation of communities, offering varied experiences for education, enjoyment, reflection and knowledge sharing. (ICOM 2025)

The journey toward today’s perception of what a museum should be, as revealed by ICOM’s approved definition, started centuries ago with revolutionary shifts in concepts and actions relating to the public sphere. It is perhaps no mere coincidence that the same period (late eighteenth–nineteenth century) saw significant changes in uses of the words culture, industry, democracy, class and art (Williams 1960, ix et passim),[2] and a boom in the numbers and types of museums being established and made accessible to the public (Latham and Simmons 2014, 46). Developments in the meanings of these words and in the museum world both reflected what Williams felt was movement toward “a new kind of society [leading to a new kind of] practical social judgement” (Williams 1960, xvi). The “theory of culture” and “revision of our received cultural history” that he called for and instigated were enthusiastically taken up in the social sciences, producing a proliferation of further definitions and uses of the word and concept culture which had long since, as Williams noted, taken on the meaning of “a whole way of life, material, intellectual and spiritual”; the phrase “way of life” is still used as a synonym for culture in its widest sense (Williams 1960, xiv; Jary and Jary 1995, 139). The new public museums were and still are physical and democratized manifestations of their societies’ understanding of what culture is, dependent upon a culturally formed urge to collect and inspect materials that will reflect back on the collecting society’s sense of its self; museum visiting is, in this way, a physical manifestation of a characteristic of culture, which is that “[h]uman beings are both acted on by culture and act back, and so generate new cultural forms and meanings” (Jary and Jary 1995, 139). So it is that museums and collections have accumulated and reflected to society its identity as, among other things, a collecting culture. Museums are thus to be understood as institutions of cultural self-reflection and identity, and of cultural archiving and memory (Velhinho and Almeida 2023, 3). Democratized understandings of culture led to expanded types of museum collections and displays, which, by the second half of the twentieth century were including and even specializing in items representative of local culture, industrial culture, popular culture, and from many other “ways of life.” Late twentieth and twenty-first century understandings of “culture-as-social-formation” and “culture-as-dialogue” have followed other postmodern conceptualizations that replace the static with the procedural and interactive; they define culture as interactively created and continuously generated by socio-cultural reflexivity, and as “the set of norms, practices and values that characterize minority and majority groups,” as well as “ongoing negotiation and inculcation of learned and patterned beliefs, attitudes, values and behaviours” and “norms and expectations” (Jary and Jary 1995, 139; Klein 2020, at 23: 18).[3] It is intangible and dispersed among the societies that are involved in its identification: “Today [. . .] culture is understood broadly to refer to the cultural webs of meaning in which we are entangled” (Rönkä 2021, at 1: 19–28).

“No collection, no museum” (Miller 2018, 6) is an understanding shared by museologists and enshrined in all of ICOM’s definitions to date. The same could be said of most digitization projects designed for public or institutional use: no data collection, no database, no digitization project; so it is collections that are what museums and such digitization projects have in common. In time, cultural diversity has become increasingly recognized, even by international institutions, and preservation policies aimed at the “urgent safeguarding [. . .] of the intangible cultural heritage of humanity” have been suggested since the early 2000s (Velhinho and Almeida 2023, 4; Gahtan et al. 2020, 15). The ever-growing number of projects digitizing existing museum collections has not been able to match every aspect of these requirements, because in the analogue collections of older established museums there tend to be smaller numbers of items explicitly displayed as reflexes of intangible heritage, and sometimes only archaeological collections are explained as representing diversity of intangible culture. In general, however, well-funded museums and other institutions are increasingly including new types of digital (or digitally enhanced) collection and exhibition spaces; in these efforts they also explore the storing and display possibilities of digital collections of intangible culture. There are even collections of digital culture itself, such as Deloitte’s Digital Media Trends collection.[4] Digital spaces are available for public collaboration in museum-type collecting, too. Echoing twentieth-century changes in museological outlooks, as verbalized in ICOM’s recent redefinition of the museum, the twenty-first century’s burgeoning of platforms that are driven by and include social and community input recognizes late twentieth century concepts such as those of the eco-museum and the museo diffuso or dispersed museum, and reflects a new phase in the democratization of museology. A new, theoretical and practical, discourse of cybermuseology has opened up within museum studies, too, and portals presenting collections of collections (e.g. Europeana) have been launched (Velhinho and Almeida 2023, 4).[5]

The digitization of museums can expand, share, and at the same time personalize individual and group cultural identities. This is not an uncontroversial assumption, however, since the cultural identities and experiences of digitally created personae and groups are virtual: cyberidentities and cybersociality. Here individuals share, withhold, or even create varying elements of their personal and cultural identities; this has been called the subject-led negotiation of identities, made possible by the digital and new-media world (Darvin 2016, 525–526); this resembles definitions of culture as interactive narratives, and ongoing negotiation and inculcation. Further, just as with analogue museums, the cultural content that is reflected by the collection is molded by the project’s overt and covert principles of selection and by the biases inherent in the design of databases and interfaces: more generally, and at an even less visible level of formation, even if the collection aims at including a diversity of items, the “algorithmic processing” of data means that each item is displayed in the same way as the others, leaving out aspects of that item that are not addressed by the database metadata, and potentially “flattening” the overall presentation of the cultural area addressed by that collection; possible dangers lie also in the “non-transparent” realm of the operating systems used by public platforms (Velhinho and Almeida 2023, 6–7).

Being itself a dynamic and intangible process, digitization is particularly well suited to the collecting and display of intangible culture, but not all of the above-mentioned dangers can be averted, and the designers and curators of digital museums of intangible cultural heritage are faced with special challenges in the attempt to overcome or offset them. The items on display in such museums exist in virtual tangibility only, as digital items; they merely represent the intangible cultural heritage, and are mediated narratives of that intangible culture, susceptible to the discourses and understandings of the time of mediation and of viewing, and are not the thing itself (Sousa 2018 in Velhinho and Almeida 2023, 10). Further, the flattening caused by metadata can place digital collections and displays of intangible cultural heritage at greater risk of denuding the exhibits of inconsistent and idiosyncratic variations (wherein lie greater diversity), because cultural intangibility is characterized by dynamism, arguably more than by immateriality, and, hence, by constant variability and change (Amescua 2013, 126).

Positive developments in creation of digital collections and digital interfaces for the display of intangible cultural heritage include the fact that, with continued and growing exposure to digital collections of cultural material, present-day users are gaining in digital knowingness and “acquiring new skills of thinking . . . in terms of conceptualization [and] in how to navigate a media environment of seemingly infinite choices” (Darvin 2016, 525). Furthermore, as research into digital culture advances, curators and designers of digitized intangible cultural heritage (in contrast to many or most of the contributing users of uncurated social media platforms) tend to be very aware of the degree of constructedness – indeed of the “co-constructedness” (Darvin 2016, 526) – inherent in the digital intangible culture product; and they offset this by following established guidelines from the digital humanities and later protocols; these projects make the scope and limitations of their exhibiting designs as transparent as possible.

The entirety of Eurotales is envisioned as a multi-modal and enduring platform for the collection and display of the language heritage of a very large area: a Europe without firm spacial or temporal borders, because languages themselves, like many intangible cultural heritages, are bound only to their users, who may be found anywhere, at any historical period. We use maps of the European region as a way of showing where language users reside, or were born (in Resonances of the Past and of the Present),[6] and where languages in use have left their cultural footprints (Traces). The map illustrates the project’s scope and limitations – the museum includes languages that are culturally and primarily associated with Europe by origin and history, and limits its collections to items and speakers within that large territory. A digital museum is particularly well-suited to the display of geographically dispersed culture, since its borderless nature is actually reflected in the cyberworld, a huge and unbounded intangible space within which all elements are rendered intangible. Digitalizing linguistic culture, as we are doing, takes advantage of the “virtual travel and fluidity of movement” of the cyberworld, where “identities become unbounded and deterritorialised, no longer tied to fixed localities, patterns, or cultural traditions” (Darvin 2016, 526).

With a policy of inclusion and a need for scrupulous and scholarly curation as prescribed for museological (Miller 2018, 8),[7] digital (Pitti 2004, 471), and humanities scholarship (McGann 2014, 79),[8] the museum has constantly expanding collections, regularly updated modules, display technologies and designs, and plans to continue developing new and different interfaces;[9] with these, it conforms with both the ICOM definition, and suggestions from critical and theoretical digitization studies (Berry and Fagerjord 2017, 127, 140); it benefits from the constant adjustments that are required by a well-designed, progressive project (Pitti 2004, 473) and that are considered characteristic of both cultural and collective memory and digital, participatory culture (Rönkä 2021, at 4: 19–4: 31; Velhinho and Almeida 2023, 9). The digital museum is culturally integrated within the larger and smaller community and communities of Europe that it serves: its collections represent collaborations between community participants and curators, with the end-product – the web museum – being openly accessible to the user community and beyond; this allies our digital museum conceptually with Eco-museology.

3 Language and Digitized Intangible Culture (Traces)

That language is a formative component of human culture is as axiomatic as the recognition that, like culture, it is both shared and valued by members of its extended communities. Also, like culture, it belongs to those “social objects and activities which are primarily or exclusive symbolic in their intent or social function” and that are generally recognized as defining traits of humanity (Silverstein 2023, n.p.; Reed and Alexander 2006, 112). Culture, Williams’s “way of life” that is nowadays more analytically observed as an “ongoing negotiation of learned and patterned beliefs, attitudes, values and behaviors” (Klein 2020, at 3: 16), is intangible; it “cannot be seen, heard, or sensed directly. We cannot study culture except by studying its effects on (and in and through) things like discursive interaction [. . .]” (Silverstein 2023, n.p.). Language, too, is intangible – we cannot study it except by studying its different various manifestations in vocal, or written, or even neural forms. These reflexes both form and take their meanings from socially embedded use and are thence fundamentally cultural. “‘[L]anguage’ and ‘culture’ may be abstract, intensional terms [. . .] but the extensional reality, the lived reality of language and culture are in fact densely interconnected structures of interdiscursivity.” In other words, language and culture are intangibles that are manifested in their uses and relations to meaning. Both are universal human heritage. Silverstein presents language as “cultural stuff” and a “code of culture” of a unique nature, it being “the leading medium through which all the other cultural codes come to be enregistered”; language is undeniably, then, intangible cultural heritage of an extraordinary kind (Silverstein 2023, n.p.).[10]

As discussed, digitization and digital design are particularly well suited to the challenges of collecting and displaying intangible culture, given the shared dynamic and fluid character of the digital world and intangible culture. A potential drawback of digitization was identified as the flattening effect of subjecting materials that display diversity and idiosyncrasies to reformulation by universally applied “algorithmic processing” (Velhinho and Almeida 2023, 6) and metadata, that produce digitized output that may compromise the methodological integrity, and even the form, of the digital product. Eurotales, being envisioned from the outset as a museum of intangible cultural heritage, has benefited from awareness of the dangers of collecting and presenting diverse and varied items through a homogenized base. The museum directors and curators are researchers of real-life uses of language and culture; we are aware of the flattening effects of most traditional descriptions and representations of languages, which are routinely perceived and spoken of in overly generalized, standardized, and unnaturally fixed ways, whether by grammar books or by common perceptions and misconstruals of what a verbal language is. Change and variation, at the heart of intangibility and of human languages, and essential to how they are able to make cultural meaning, is something that thoughtfully designed digitized displays may be better able to evoke or include than analogue ones.

Eurotales addresses the problem of displaying the intangible cultural heritage of language, and attempts to capture the complexity and protean nature of language as intangible culture through creating a plurality of digital collections, each designed to present and describe, in different ways, the multiple reflexes of language in material and localised culture (Traces, described in this section), and in human culture (Resonances and Timelines, described in the following section). The metadata of the Traces and Resonances of the Past collections provide extended commentary, informing visitors about the particularity of the item and the significant interaction of culture and language it represents. These collections also display links to, e.g., mapping, audio and video material; and on entering a collection’s homepage, visitors are invited to contribute their own suggested materials, through a link provided. The webpage provides spaces for other forms of display and searchable access. In these ways, the museum aims to directly and indirectly expose visitors to the dynamic, changeable, and variable nature of languages among and within speakers, through time and space, and in interaction.

The Traces collection is based on the recognition that “one cannot abstract [a quantum of language matter] from its original [cognitive] association with a certain experiential landscape out of which it has been drawn by memory” (Gasparov 2010, 6). It researches and displays material objects that are tangible parts of experiential landscapes and that, to appropriate McGann’s words into a different context, carry some of the “hundreds of voices” that “lie concealed in these tracings” (2014, 16, 78). Each item in this collection is identified and extensively researched by academics, who enter the metadata with scrupulous attention to scholarly standards, including citations and the obtaining of rights and permissions for images not produced by themselves. Each Trace is presented and explained as giving voice to a particular instance of linguistic culture, either overtly (through inscriptions or grafitti) or covertly (through association with use, with oral history, or with narratives). Visitors see each exhibited Trace as one or more images alongside descriptive information, including transcriptions and translations of any writing on the object; and the images are followed by contextualizing explanations, which are often further elaborated in an expandable section. An example is the Canto di Balla Trace, which is a particularly good illustration of how Traces relate to the intangible linguistic culture that we thereby exhibit. The image on this item shows a modern plaque, apparently naming a place, situated in Florence; but it does not relate to any place name used today; rather, the plaque is showing a twelfth century way of referring to places, in the Tuscan dialect, and is a marker of an old oral tradition. The explanation below the image tells us about the linguistic and geographic experiential landscape within which this toponym first appeared, and explains the significance of both the place and the Tuscan terminology used in this old way of designating areas of the city (Gahtan 2025).

Not all Traces are as easily pinpointed to single, unchanging, places, because (like language in use) objects enshrining linguistic heritage are also widely spread and mobile, and function within many cultures, as do the visitors to this museum. For this reason, the individual Trace exhibits contain explanations of the often multiple geographical, linguistic, and temporal backgrounds and journeys of the voices and objects they display, while mapping the items on their current locations. The Piraeus Lion Trace (Sönmez 2025), for instance, maps a rune-inscribed ancient Greek statue on its current location in Venice, although the statue is a trace of the culture, voices, and writing system of Vikings in the service of the Byzantine empire.

4 Digitizing Linguistic Culture: Memories and Identities (Resonances and Milestones)

Cultural heritage, memory, and identity are “closely linked”: heritage and cultural memory are “entangled” in both individual and social perception and expression (Viejo-Rose 2015, 2, 4), and cultural identity is “internally constructed” and at the same time “driven by pre-existing historical and social traditions” (Klein 2020, at 5: 45 and 8: 44). Language is intimately tied to these elements too, identity (or “self-concept”) being “constituted by the meanings of language and how it is reflected by language, not just in small-scale social interactions but also in larger linguistic-political discourses” (Evans 2015, 3).

Collections (archives) and museums, as institutions of cultural memory, attract and allow visitors to experience this interdependent triad, and expand their personal cultural memories and identities through new perceptions. Linguistic objects and events may be considered by visitors, and displayed in these institutions as, for example, triggers, containers, communicators, markers, anchors, sites, and narratives of memory (Viejo-Rose 2015, 3).[11] With collective memory being “deeply affected by the forms and technologies of registration and access” and “social dynamics [being] enhanced by participatory methodologies and tools” (Velhinho and Almeida 2023, 4), digital and digitized public platforms like Eurotales can directly and indirectly impact the collective linguistic memory of Europe. They are also formative of self-identity, to greater or lesser extents depending upon the individual’s immersion in digital and new media. This is because “a person’s sense of self and relation to the world continuously shifts” which makes identity “dynamic, multiple and even contradictory. As the digital provides multiple spaces where language is used in different ways, [users] are able to move across online and offline realities with greater fluidity and perform multiple identities” (Darvin 2016, 524).

Collecting, displaying, and viewing cultural heritage are among the “culturally shaped practices that steer us to remember certain things and to forget others,” moderating “even our most personal memories,” thus, again, presenting culture as a living narrative, and a continuous negotiation and inculcation (Rönkä 2021, 2: 33–2: 37; Klein 2020, at 23: 18). Language and memory are both, then, shaped and produced by cultural (experiential) landscapes and “social frameworks” (Gasparov 2010, 6). The growing number of digital and new media collections are increasingly part of this “steering” experiential landscape. The collections of Eurotales that are most directly designed to show, prompt, and create cultural and shared memories of languages are the Resonances of the Past and Milestones collections, while the Resonances of the Present collection is designed to evoke language heritage as the meeting point of individual memory and identity. The initial idea behind the two Resonances collections was to display items that could prompt visitors to relate their own and others’ experiences of language biographies to their commonly held cultural knowledge, and thus revisit both their own and others’ lives, memories, and identities as embedded within a multilingual mosaic that extends through time as well as space. In these collections, people are presented as elements of linguistic heritage.

4.1 Resonances of the Past and Milestones

The Resonances Past collection shows how the voices of Europe resonated with and through people in the past. As with the Resonances Present collection, it shows that neither people’s first languages, nor their main languages of use, nor the languages that are generally associated with their places of residence or with their places of action, can be predicted from their countries of birth or assumed nationality. The language-focussed biographies of publically-known historical figures thus reveal the nature and fluidity of social and individual language identity, demonstrating that these have always been fluid and changeable; and because the people represented in the collection and display are well-known, they also exist in cultural memory. Where other culturally shaped practices – such as the publishing (in any medium) of biographies, and the reproduction of popular myths about historical figures – often ignore the subject’s linguistic history, Resonances of the Past foregrounds this, and reveals (again) the interconnection of language and culture as they are inextricably interwoven with an individual’s identity as a cuturally significant person. Items for this collection are selected and researched by several volunteering academics and also by students taking the online course “Linguistic Cultures and Communities in Europe (Past and Present). Building the Eurotales Museum” offered through the CIVIS platform.[12] All submitted research for this, as for the other collections, is carefully curated for accuracy and scholarly accoutrements (as with Traces), before being entered into the databases.

Along with notable multilinguals, and figures who made notable linguistic contributions to European culture, Resonances of the Past displays and re-inserts into cultural memory the languages and varieties (including dialects and varieties that have no name) that institutionalized memorializing sites and cultural myths very often exclude or overlook. As an example from the collection, we may consider the Napoleon Bonaparte Resonance. Accompanying the exhibit’s images relating to Napoleon and his languages is a textual explanation, most of which is presented below.

Napoleon I, first Emperor of the French and icon of French imperialism, knew no French until after the age of 10, when he was sent to school in France. Throughout his youth and well into his twenties, even as an officer in the French army, he nurtured a strong Francophobia (McLynn 1997, 28), which may explain why “he never mastered the rules of spelling and always spoke with an Italian accent, pronouncing certain words as if they obeyed the rules of Italian phonetics” (McLynn 1997, 18). This did not stop him from trying his hand as a novelist, writing a romantic novella in French (Clisson et Eugénie) in 1795, and founding two French newspapers (Dwyer 2007, 306). When it came to learning new languages, however, throughout his life Napoleon demonstrated “absolutely no linguistic talent” (Dwyer 2007, 24). His first language was Corsican, a Romance language closer to Tuscan than to other languages; and he and his proudly Corsican family [. . .] would have also been variably proficient in Italian, [that remained] the language of administration in Corsica [in his lifetime]. At school he learned Latin, and “some German” at which he proved to be “hopeless” (Dwyer 2007, 16, 24). Later, when exiled at St Helena, he used some English. These are the six main languages which, to varying degrees, resonated in Napoleon’s education and life (Sönmez 2023).

Cultural memories of language are also on display through timelines of languages, generated by the Milestones collection. The canonical histories of named languages of Europe, which promote and fix approved narratives belonging to cultural memory (which is thus “steered” by these histories, too), are researched and used to create Milestones for the most significant events in the histories of these languages. As with Traces, this research is conducted by academics and, again, carefully curated before being put into the database. The Milestones form the database, which generates Timelines that can be viewed language-by-language, or with selected languages displayed together. The metadata includes categories from which other filters can be produced, presenting flexible options for viewing, as, for example, “political event,” “language and gender,” “language and institutions,” “First printed text,” “Canonical Text,” “First radio,” and “First TV Broadcast.”

Especially when viewed in contrast with the individualized narratives of linguistic culture, memory and identity that are displayed through Resonances of the Past and Resonances of the Present, the canonical histories of named languages show how public cultural memory has – until recently – been steered by established and conventional memory institutions to forget very large swathes of linguistic culture, and to overlook languages that are not constitutionally accepted as national languages. From its inception, a core aim of the Eurotales project was to offset the flattening effects of standardized and standardizing national and historical narratives, and to do this by using the flexibility and adaptability of multiple digital bases to create growing collections and displays that reflect rarely displayed languages and language uses. All of our collections, as their descriptions will have shown, include elements of overlooked linguistic culture, and allow for dialogue between their exhibits and official narratives of language. In this way, the museum is deeply implicated in what has been named “the Digital Co-Creation of Collective Memories” (Velhinho and Almeida 2023, 9).

The Traces, Resonances of the Past, and Resonances of the Present collections, as described, present opportunities for the restitution of canonically marginalized linguistic history and culture, but not all overloooked languages have readily available and published histories to be researched, from which Milestones may be created. We are nevertheless looking forward to continuing the expansion of this collection through researching and adding timelines of European languages that are sometimes overlooked, where their histories have been recorded (we can name Breton and Cornish as such languages that have recently joined the Milestones collection, and Occitan and Basque as two that are planned for the near future). Endangered and vulnerable languages, that are important elements in individual and localized cultural identities, will altogether slip out of the cultural memory of Europe unless brought back into non-specialist and public discourse about languages. They need to be “negotiated” back in to the cultural memory and identity of Europe, and it is hoped that Eurotales will play a part in this process. However, official and detailed histories of endangered and vulnerable European languages such as Aromanian, Alemannic, Homshetsi, and Pontic Greek scarcely exist or are difficult to find, making it very difficult to research and illustrate Milestones in order to create timelines; such languages may be better represented through Resonances (of the Past and of the Present) or Traces, where some of them are already present. By including such languages and references to sources about them, we will be making further records of these languages a little easier to find, too.

4.2 Resonances of the Present

As the only display based solely and entirely on data provided by participating members of the public, the Resonances Present collection enhances the links between individual and cultural identity, and displays how linguistic identity manifests itself in individuals, in families, and across generations. In addition to providing interactively produced exhibits, the Resonances of the Present database is an important part of the experimental and dynamic nature of the museum, as it indicates languages of Europe that should be further researched and added to the collections and displays (Cannata et al. 2023). The collection comprises thousands of database entries detailing the language biographies of informants and their social and familial networks, from all over Europe; the data is extracted from a growing mass of questionnaires, the majority of which are distributed and filled in by EU students taking the Sapienza (University of Rome) “Linguistic Cultures and Communities in Europe (Past and Present). Building the Eurotales Museum” on the CIVIS platform, that was introduced in Section 3 above. Informed consent is obtained from all respondents before the interviews are conducted. Respondents provide their names as ways of ensuring they are human respondents, and the data is anonymized before being entered in the database; identifying information is then permanently deleted from the records.[13] The data is displayed graphically through clickable maps, and linguistically and statistically through labelled colour wheels and pie charts. This collection is designed to show the many different languages spoken in Europe and recalled by individuals within their families (and in society), going back two generations. It presents an indication of the “situated language ecology” of individuals (Darvin 2016, 529) and relates to their individual and social identities in various ways. The question of self-identity is semi-directly approached in the questionnaire’s open question “which language would you be most reluctant to lose?”, which has produced some very interesting commentary and insights. Showing the results of thousands of responses to this open question is posing ongoing display challenges.

5 Conclusions

The impact of the digital upon culture, memory, identity, and heritage has been reported in several parts of this article, and tying together these reported observations, with the benefit of some experience in attempting to create digital collections and displays of language as intangible cultural heritage, the following brief concluding comments may be made.

As indicated in the foregoing paragraphs, growing numbers of books and research papers on culture, memory, and identity have emphasized that they are interlinked concepts relating the individual to the social, and that they are all fluid, changeable, and in constant dialogue (or negotiation) with and between humans and their experiential environments. Studies of the impact of digital technologies and new media upon these areas of interest note that the cyberworld share these qualities; and studies on language note that it, too, is integrally linked to culture, memory, and identity, and likewise shares these qualities. Recognizing dynamicity as the overriding quality of intangible culture may lead us to understand that what all these elements share is this fluidity and adaptability, or this tendency to change and vary in accordance with interchanges between individuals and the multiple social worlds they inhabit. From this perspective, Eurotales is not just a new museum of language but a museum for a new cyberworld that is uniquely placed to collect, present, and open new discussions about the intangibles of human existence, including that all-encompassing entity we refer to as culture, of which language is recognized as a formational medium and foundational element (Silverstein 2023, n.p.).

The project as described here has been designed as open-ended (expandable), and incorporating multiple databases (collections), in order to allow for the explicit and implicit interplay and dialogue between the different and often contrasting collections; this serves to reflect back to the museum’s users/visitors the multiplexity and dynamicity of linguistic culture. Its open-endedness means that the museum can be expanded to include more and different languages or regions; the only restrictions are time and manpower, which are greatly affected by our policy of avoiding automated data-collecting or database-filling tools and mechanisms. The manual selection, collection, and entering of metadata in each database has been designed to overcome the flattening effect of automated entry and to allow each item to be presented with its shared descriptors, alongside its idiosyncrasies and other significant notes. It is here that the embedding of the project within an academic research facility, with resultant open-endedness for time and content of the project, makes its mark, as strict adherence to scholarly standards of research is required for every item that will be displayed; this includes careful curating, which cannot be automated. Similarly, although the collections are displayed using maps or with reference to present-day European country names, the metadata includes commentary or notes sections that allow curators to indicate the appropriate name- or border-changes that impact the geographic identities of regions, languages (Resonances display this), and also objects (Traces), at different historical times.

The project shares Grusin’s hope that its application of digital technology to the practices of museology, and its digital response to the challenges of displaying intangibles, can “transform our understanding of the canon and history of the humanities by foregrounding and investigating the complex entanglements of humans and nonhumans [. . .],” and be part of the ongoing redefinition of “our traditional humanistic practices of history, critique, and interpretation” (Grusin 2014, 89–90).

References

Amescua, C. 2013. “Anthropology of Intangible Cultural Hereitage and Migration: An Uncharted Field.” In Anthropological Perspectives on Intangible Cultural Heritage, edited by Lourdes Arizpe, and Cristina Amescua, 103–20. Springer International Publishing.10.1007/978-3-319-00855-4_9Search in Google Scholar

Berry, D. M., and A. Fagerjord. 2017. Digital Humanities. Knowledge and Critique in a Digital Age. Polity Press.Search in Google Scholar

Cannata, N., M. W. Gahtan, and M. J.-M. Sönmez. 2023. “Eurotales – A Museum Lab of the Voices of Europe, Representing the Memory of Languages.” Unpublished Paper Presented at the Memory Studies Association 7th Annual Conference: Communities and Change. Newcastle University. July 3–7, 2023.Search in Google Scholar

Cannata, N., M. J.-M. Sönmez, and M. W. Gahtan. 2020. “Eurotales: A Museum of the Voices of Europe.” In Museums of Language and the Display of Intangible Cultural Heritage, edited by M. J.-M. Sönmez, M. W. Gahtan, and N. Cannata. Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Darvin, R. 2016. “Language and Identity in the Digital Age.” In The Routledge Handbook of Language and Identity, edited by Siân Preece. Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Dwyer, P. 2007. Napoleon: The Path to Power. Bloomsbury.Search in Google Scholar

Evans, D., ed. 2015. Language and Identity: Discourse in the World. Bloomsbury.Search in Google Scholar

Gahtan, M. W. 2025. ““Canto di Balla.” Eurotales: Traces. Last modified July 2025.” https://eurotales.eu/tracce/.Search in Google Scholar

Gahtan, M. W., N. Cannata, and M. J.-M. Sönmez. 2020. “Introduction.” In Language Museum and the Display of Intangible Cultural Heritage, edited by M. J.-M. Sönmez, N. Cannata, and M. W. Gahtan. Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Gasparov, B. 2010. Speech, Memory, and Meaning. Intertextuality in Everyday Language. De Gruyter Mouton.10.1515/9783110219111Search in Google Scholar

Grusin, R. 2014. “The Dark Side of Digital Humanities: Dispatches from Two Recent MLA Conventions.” Differences: A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies 25 (1): 79–92. https://doi.org/10.1215/10407391-2420009.Search in Google Scholar

ICOM. 2025. “Museum Definition.” In ICOM International Council of Museums. https://icom.museum/en/resources/standards-guidelines/museum-definition/.Search in Google Scholar

Jary, D., and J. Jary. 1995. Collins Dictionary of Sociology, 2nd ed. HarperCollins.Search in Google Scholar

Klein, S. 2020. “Identity, Society and Culture.” YouTube, September 17. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rb_b6SV1j5U.Search in Google Scholar

Latham, K. F., and J. E. Simmons. 2014. Foundations of Museum Studies. Evolving Systems of Knowledge. Libraries Unlimited.10.5040/9798400653261Search in Google Scholar

Lenard, P. T. 2020. “Culture.” In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, edited by N. Edward. Zalta. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2020/entries/culture/.Search in Google Scholar

McGann, J. 2014. A New Republic of Letters. Memory and Scholarship in the Age of Digital Reproduction. Harvard University Press.10.4159/9780674369245Search in Google Scholar

McLynn, F. 1997. Napoleon. A Biography. Jonathan Cape.Search in Google Scholar

Miller, S. 2018. The Anatomy of a Museum: An Insider’s Text. John Wiley and Sons.10.1002/9781119237051Search in Google Scholar

Pitti, D. V. 2004. “Designing Sustainable Projects and Publications.” In A Companion to Digital Humanities, edited by S. Schreibman, R. Siemens, and J. Unsworth, 471–87. Blackwell Publishing.10.1111/b.9781405103213.2004.00034.xSearch in Google Scholar

Rönkä, M., ed. 2021. “What Is Cultural Memory.” YouTube, February 23. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hrECyLpL_gY.Search in Google Scholar

Reed, I., and J. Alexander. 2006. “Culture.” In The Cambridge Dictionary of Sociology, edited by B. S. Turner. Cambridge University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Silverstein, M. 2023. Language in Culture. Lectures on the Social Semiotics of Language. Cambridge University Press.10.1017/9781009198813Search in Google Scholar

Sönmez, M. J.-M. 2023. “Napoleon Bonaparte.” Eurotales: Resonances of the Past. July 4. https://eurotales.eu/risonanze/.Search in Google Scholar

Sönmez, M. J.-M. 2025. “The Piraeus Lion.” Eurotales: Traces. Last modified June 21, 2025. https://eurotales.eu/tracce/.Search in Google Scholar

Velhinho, A., and P. Almeida. 2023. “The Legacy of Collective Memory in Digital Culture: Digitisation, Cultural Mapping and Co-Creation.” Comunicação e Sociedade 43: e023003. https://doi.org/10.17231/comsoc.43(2023).4344.Search in Google Scholar

Viejo-Rose, D. 2015. “Cultural Heritage and Memory: Untangling the Ties that Bind.” Culture & History Digital Journal 4 (2): e018. https://doi.org/10.3989/chdj.Search in Google Scholar

Williams, R. 1960. Culture and Society 1780–1950. Anchor Books.Search in Google Scholar

© 2026 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.