Abstract

In the digital age, social media platforms like Facebook, Instagram, and YouTube have emerged as powerful allies in promoting and preserving heritage sites. Focusing on the unique heritage of Bishnupur, West Bengal, India, this manuscript investigates the intricate interplay between social media and these cultural treasures. Through a comprehensive analysis of engagement metrics such as likes, shares, and comments, the study uncovers the nuanced dynamics of how online audiences connect with heritage sites. Platform-specific strategies are identified as essential for tailoring content to the strengths and preferences of each social media platform’s user base. The study also reveals the organic emergence of vibrant communities of heritage enthusiasts who unite to share their passion, experiences, and advocacy. The research emphasizes social media’s key role in promoting heritage sites and provides practical insights for optimizing platform-specific strategies, contributing to the discourse on preserving cultural heritage in the digital age.

1 Introduction

Heritage sites, standing as the tangible remnants of our shared history, cultural identity, and architectural marvels, hold a unique position in our global heritage (Waterton, Watson, and Silverman 2016). They transcend temporal boundaries, narrating tales of civilizations, artistry, and innovation. These sites, whether ancient archaeological treasures or iconic architectural landmarks, do not merely offer glimpses into our past; they serve as repositories of cultural memory and anchors for our future (Noaime and Alnaim 2023). Their significance extends beyond the confines of preservation; they are potent economic assets, invigorating local economies and beckoning millions of tourists annually. This intricate blend of cultural and economic importance makes heritage sites a topic of enduring interest and study (Aruljothi and Ramaswamy 2019). The very essence of heritage site preservation and promotion has undergone a transformation in our digital age. The internet, particularly through the lens of social media, has emerged as a transformative force in the world of tourism (Kamariotou, Kamariotou, and Kitsios 2021). It has redefined how travellers explore destinations, share their experiences, and engage with the places they visit. In this digital landscape heritage sites have found a dynamic ally. Through platforms like Facebook, Instagram, and YouTube, they have harnessed the power of visual content, storytelling, and instant connectivity to capture the imagination of a global audience (Alexander 2017; Kim and Yang 2017).

The theoretical foundation of this study rests on several pivotal pillars. Firstly, it is anchored in the recognition that heritage sites are not static artifacts but living cultural entities. The theoretical perspective draws from heritage studies which emphasize the dynamic and evolving nature of heritage. This perspective underscores the cultural, social, and economic dimensions of heritage sites, positioning them as spaces that demand active preservation and promotion (Di Fiore 2020). The second pillar of the theoretical framework is the concept of the digital age and its profound impact on various facets of life. In particular, the influence of digital technologies and social media in the realm of tourism and cultural heritage is firmly established. These technologies have introduced novel paradigms of interaction, engagement, and knowledge dissemination (Kumar et al. 2023; Saseanu et al. 2020; Sheldon 2020; Sutrisno 2023).

Heritage sites are repositories of cultural identity and historical memory, and their preservation and promotion are not only a cultural responsibility but an economic imperative (Harrison et al. 2020). The UNESCO World Heritage Convention underscores the global commitment to safeguarding these treasures, recognizing their intrinsic value to humanity (Cave and Negussie 2017). In this context the study addresses the contemporary challenges and opportunities facing heritage site promotion in the digital age. It acknowledges the dual nature of heritage site tourism – a source of economic vitality and a potential threat to the sites themselves. This duality necessitates innovative and informed strategies to maximize the benefits while mitigating the risks.

While heritage studies and digital tourism have been extensively explored (Cantoni 2020; Economou 2015; Swensen and Nomeikaite 2019; Zhang et al. 2023) the unique heritage of West Bengal offers a distinct backdrop. The overarching aim of this study is to explore the dynamic interplay between heritage site tourism and social media within the cultural and economic context of West Bengal, India. This study embarks on a journey to unravel the intricate relationship between heritage sites, social media, and tourism within the rich tapestry of West Bengal’s cultural heritage. Its aim is not only to understand the present state of heritage site tourism but to equip heritage site managers, tourism professionals, and policymakers with the tools and insights needed to harness the potential of social media for the promotion and preservation of these invaluable cultural assets.

2 Literature Review and Knowledge Gap

Heritage sites, as tangible links to our collective history and culture, occupy a significant space in our contemporary world (Apaydin 2020). They serve as repositories of identity and are vital economic assets for the regions they are situated in. Tourism at heritage sites has witnessed a surge in recent years, becoming a substantial contributor to local economies. However, this surge in popularity has raised several challenges and concerns, prompting the exploration of innovative approaches to address them (Smith 2015).

2.1 The Role of Heritage Sites in Culture and Economy

Heritage sites hold significant cultural value, connecting communities to their roots and preserving historical narratives, which fosters a sense of pride and belonging (Beel and Wallace 2018; Meskell 2018). This cultural significance is intertwined with economic benefits as heritage tourism stimulates local economies, creating jobs and promoting entrepreneurship (Li, Lau, and Su 2020; Shishmanova 2019). Recent studies emphasize the multifaceted impact of heritage tourism on local communities. Faria et al. (2024) highlight how these sites facilitate cultural exchange and enhance social cohesion, while Chhabra (2021) stresses the importance of sustainable tourism practices that balance economic gains with cultural preservation and environmental integrity.

The heritage tourism industry is diverse, encompassing various attractions from archaeological sites to architectural marvels (Sonia et al. 2023). The rise of digital platforms and social media has further transformed this landscape, shaping visitor perceptions and engagement (Jia et al. 2022). Guo, Yu, and Zhao (2024) illustrate how successful social media strategies can enhance the visibility and interaction of heritage sites with digital audiences. Moreover, Zhu et al. (2024) demonstrate the revitalizing economic impact of heritage tourism on rural communities, underscoring how investments in these sites can foster sustainable development. Overall, these studies illustrate that the relationship between cultural significance and economic value in heritage tourism is complex, benefiting both community identity and economic well-being.

2.2 Challenges Faced by Heritage Tourism

The rise in heritage tourism, while advantageous, has introduced significant challenges, particularly overcrowding. This issue leads to wear and tear on historical structures and diminishes visitor engagement, often resulting in dissatisfaction and reduced repeat visitation (Honey and Frenkiel 2021; Yoon et al. 2024). Sustainability and preservation of heritage sites are closely linked to factors such as visitor education, accessibility, and the balance between conservation and economic profitability. Leung et al. (2018) stress the importance of educational programs to raise awareness about preservation while Su et al. (2019) advocate for sustainable management practices that involve local communities to enhance stewardship.

The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the vulnerabilities of the heritage tourism sector, leading to temporary closures and significant revenue losses. This crisis underscored the need for resilient strategies to adapt to unforeseen challenges (Adams et al. 2022; Alonso et al. 2020). A study by Ye et al. (2024) indicates that the pandemic prompted a re-evaluation of tourism practices, encouraging more sustainable approaches focused on long-term impacts. Recent studies also explore the role of technology in addressing these challenges. Correia et al. (2023) discuss how digital solutions, like virtual tours and augmented reality, can enhance accessibility while reducing physical strain on heritage sites. This trend towards digital innovation reflects a broader movement within the tourism industry to promote sustainable practices (Wang et al. 2024).

2.3 The Transformative Role of Social Media

In the contemporary digital landscape, social media has become a transformative force in tourism, fundamentally changing how travellers plan trips, share experiences, and engage with destinations (Yang and Wang 2025). Its impact is particularly notable in heritage tourism, where platforms like Instagram, Facebook, and YouTube serve as vital repositories for visual content related to heritage sites (Koens, Postma, and Papp 2018; Rachman et al. 2023). These platforms allow heritage sites to showcase their cultural significance, interact with potential visitors, and provide real-time information (Koukopoulos, Koukopoulos, and Jung 2017). Digital marketing strategies tailored for heritage tourism have proven effective. Arasli, Abdullahi, and Gunay (2021) highlight the benefits of targeted social media advertising in reaching niche audiences, while Polat et al. (2024) demonstrate how influencer partnerships on Instagram can foster authentic connections and enhance community engagement.

Social media also plays a crucial role in broadening appreciation for heritage across geographical boundaries. Grincheva (2020) emphasizes that engaging content attracts new audiences, especially among younger cultural enthusiasts. Furthermore, Zhang et al. (2023) point out the significance of user-generated content in shaping perceptions of heritage sites, enhancing authenticity and fostering deeper connections. The integration of innovative technologies, such as augmented reality (AR), is becoming increasingly important in social media strategies. Wang et al. (2024) discuss how AR can enrich visitor experiences by offering interactive elements that promote immersive engagement with heritage content. This trend signifies a shift towards experiential marketing in the heritage sector, making innovative digital experiences essential for attracting visitors.

2.4 Knowledge Gap

This study addresses several critical gaps in the existing literature on social media and heritage tourism. First, while many studies focus on general trends there is a lack of detailed case studies that examine specific regional contexts. Additionally, current studies often emphasize quantitative metrics without exploring qualitative insights which limits understanding of audience perceptions and motivations. Furthermore, the implications of social media strategies for sustainable heritage site management remain underexplored, as does the integration of emerging technologies like augmented reality (AR) in enhancing visitor engagement. Finally, while user-generated content is acknowledged its influence on perceptions of authenticity and value in heritage sites is not sufficiently examined. By addressing these gaps this study not only enriches academic discourse but also provides actionable insights for stakeholders in heritage conservation and tourism management.

3 Materials and Methods

3.1 Selection of the Study Area

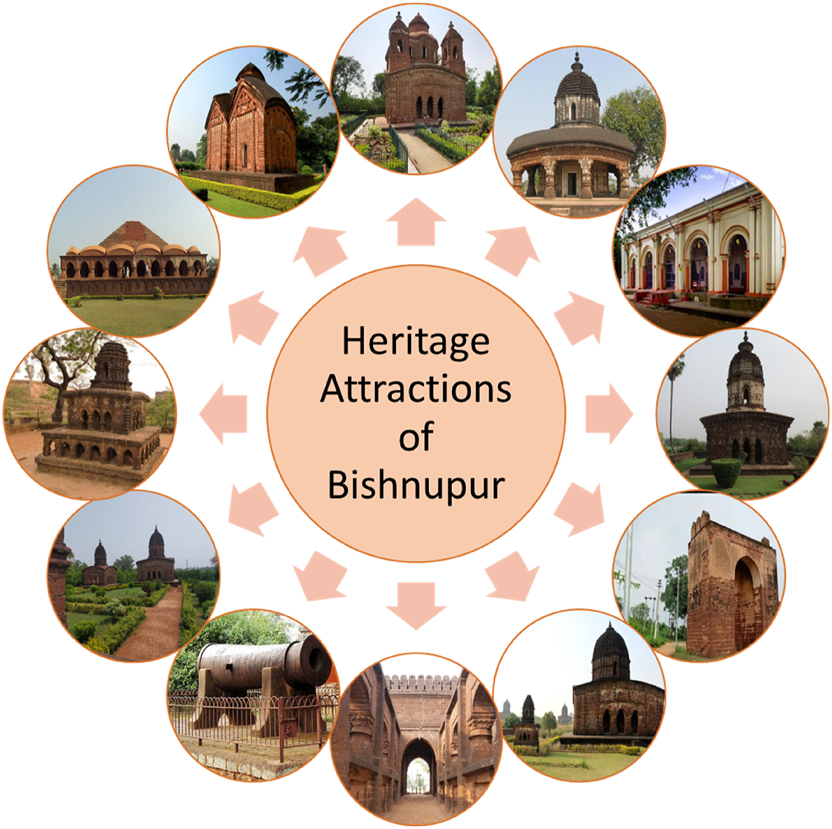

To accomplish the objectives of this study the study deliberately chose the town of Bishnupur, known for its terracotta temples and situated at coordinates 23.075°N, 87.317°E, within the Bankura district of West Bengal. Bishnupur is a renowned tourist destination that attracts a significant number of visitors annually, both from within the country and abroad. This site has gained prominence for its exceptional terracotta temples (Figure 1), constructed by the Malla rulers, as well as the historic Radha Krishna temples dating back to 1600–1800 CE, and the exquisite Baluchari sarees (Chattopadhyay 2003; Chowdhury 2006). Geographically, Bishnupur is situated at coordinates 23.075°N and 87.317°E. The district experiences a temperate climate, with cold winters and warm summers. The soil in Bishnupur is primarily categorized as ferruginous red soil. The region encompasses a substantial deciduous forest area, covering 148,177 hectares, which constitutes approximately 21.5 % of the total geographical expanse of the district. Bishnupur is readily accessible as a tourist destination, benefitting from well-established road and railway connections, making it convenient for travellers to explore and appreciate the historical and cultural richness of the area.

Heritage attractions of Bishnupur in Indian States of West Bengal.

3.2 Sources of Data

The data for this content analysis was collected from publicly available social media posts on platforms, including Facebook, Instagram, and YouTube, with a specific focus on heritage site tourism in Bishnupur, West Bengal, India. A total of 120 samples (40 from each social media platform) were collected from each of these platforms. Data collection spanned the period from September 2022 to August 2023 (the actual period during which photos and videos were uploaded), aligning with the study objectives and ensuring the creation of a comprehensive dataset. To gather this data relevant keywords, hashtags, and geotags associated with heritage sites in Bishnupur were identified and used as search terms. For instance, keywords like “Bishnupur heritage,” “Terracotta temples,” and “Bishnupur tourism” were employed to pinpoint pertinent content.

3.3 Post Selection Criteria

The selection criteria for posts involved several key factors to ensure relevance and quality of data. First, posts needed to directly relate to heritage sites in Bishnupur, highlighting their cultural significance, visitor experiences, or promotional content. Only publicly accessible posts, free from privacy restrictions, were included to maintain ethical standards. Additionally, preference was given to posts that exhibited measurable engagement metrics, such as likes, shares, and comments, allowing for a thorough analysis of user interaction and the overall impact of social media on heritage tourism.

3.4 Quantitative Content Analysis

The quantitative assessment focused on the volume of social media posts related to heritage site tourism in Bishnupur. Data regarding the frequency and prevalence of specific keywords, hashtags, and geotags in posts, comments, and captions were collected. The goal was to analyze the volume of posts over time, pinpoint peak posting periods, and identify which social media platforms were most commonly used for discussions on heritage site tourism in Bishnupur.

3.5 Data Management

The data gathered for content analysis were meticulously organized and stored within a secure and structured database. This database encompassed pertinent metadata, including the content source, posting month, and engagement metrics, streamlining subsequent analyses.

3.6 Ethical Considerations

Data collection from social media platforms was executed in strict adherence to privacy regulations and ethical considerations. Only publicly available posts were included in the analysis, with no collection of personal or private data. As the data were sourced from publicly available platforms, user consent was not a requisite for data collection. The study adhered to the terms of service of the respective social media platforms.

3.7 Data Analysis

Quantitative data analysis encompassed statistical methods to summarize and interpret the quantitative data. This included frequency analysis, trend analysis, and comparisons between different heritage sites and social media platforms. In this study the significance of user engagement is emphasized when examining the role of social media in the promotion of heritage sites. User engagement serves as a vital metric that gauges the extent of interaction, interest, and active participation exhibited by users with content associated with heritage sites on various social media platforms (Table 1).

Metrics and their descriptions used in this study.

| Metric | Description |

|---|---|

| Likes | The number of times users have clicked the “Like” button on posts related to heritage sites. |

| Shares | The number of times users have shared posts related to heritage sites on their own timelines or with others. |

| Comments | The number of comments made by users on posts about heritage sites. |

| Video views | The number of views on videos related to heritage sites. |

| Engagement rate | A calculated metric based on the total number of interactions (likes, shares, comments) divided by the number of followers or viewers, typically expressed as a percentage. |

| Time trends | The change in engagement metrics over time, showing any seasonality or trends. |

3.8 Limitations and Biases

During the data collection process several limitations and biases were encountered. A potential sampling bias was identified as the selection of posts may have favored more popular or visually appealing content, potentially skewing engagement metrics. To mitigate this a diverse range of posts was included, ensuring a balance of user-generated, promotional, and informational content. Additionally, temporal bias was recognized as the collection period may not have fully captured seasonal fluctuations in visitor engagement; thus, it is suggested that future study could benefit from longitudinal studies to analyze trends across different seasons or events. Lastly, platform-specific bias was acknowledged, given that each social media platform exhibits unique user bases and engagement patterns; engagement metrics were therefore analyzed separately for each platform to provide a more nuanced understanding of the data.

4 Results

4.1 Facebook Engagement with Bishnupur Heritage Sites

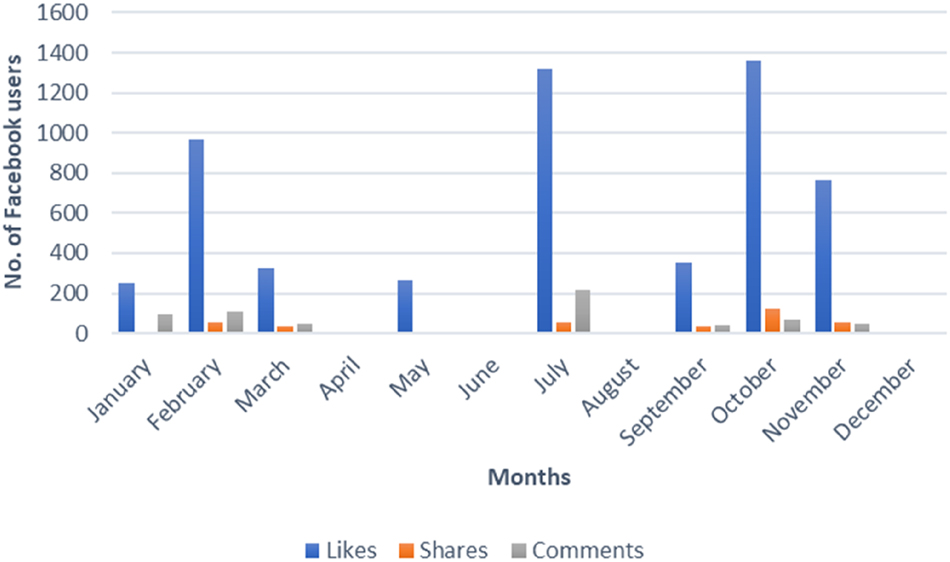

Figure 2 represents the interaction of Facebook users with heritage sites in Bishnupur, West Bengal, over a year, with each month denoting the time when photos were uploaded. Notably, February witnessed a significant uptick in activity, recording 964 likes, 52 shares, and 107 comments. This surge in engagement could be attributed to various factors such as promotional events, exceptional content quality, or thematic relevance to that specific month, signifying a successful period for audience engagement. July also stood out with substantial activity, amassing 1,322 likes, 52 shares, and 214 comments. This heightened interest aligns with the typical surge in tourism during the summer months, driving increased interaction. In contrast, April, June, August, and December registered minimal engagement with zero likes, shares, and comments. These months are often considered “off-peak” periods for tourism which might explain the dearth of promotional efforts on social media during these times.

Response of Facebook users towards heritage sites of the study area.

4.2 Instagram Engagement with Bishnupur Heritage Sites

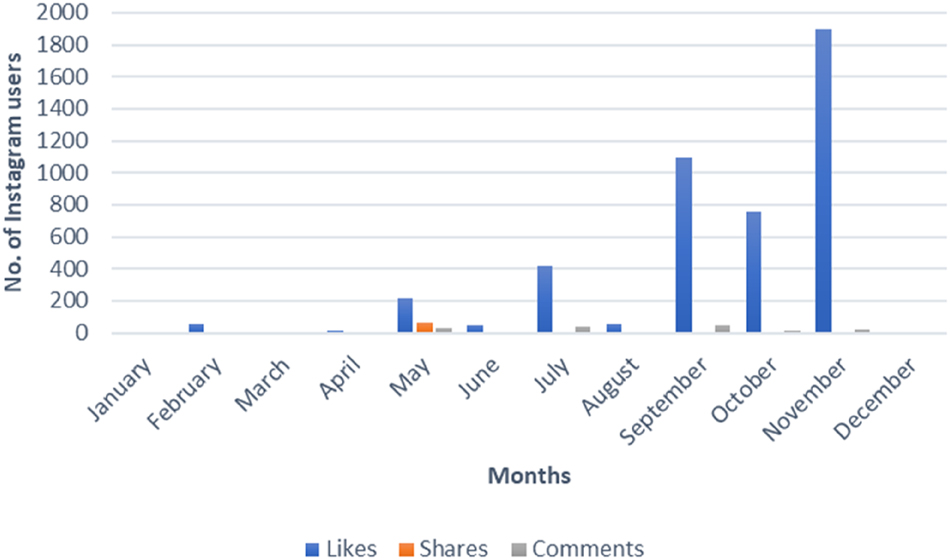

The Instagram response to heritage sites in Bishnupur, West Bengal, presented in Figure 3, revealed an irregular engagement pattern throughout the year where specific months notably stood out. In May, engagement saw a substantial surge with 212 likes, 67 shares, and 31 comments. Spring’s arrival tends to inspire people to explore and share their adventures on Instagram. September recorded the peak in likes, a remarkable 1,096, indicating a strong interest in heritage sites during that period. However, shares and comments remained relatively modest. In November, substantial engagement emerged with 1,900 likes, two shares, and 20 comments, possibly influenced by festivals or captivating campaigns. In contrast, most other months experienced minimal to no engagement on Instagram.

Response of Instagram users towards heritage sites of the study area.

4.3 YouTube Engagement with Bishnupur Heritage Sites

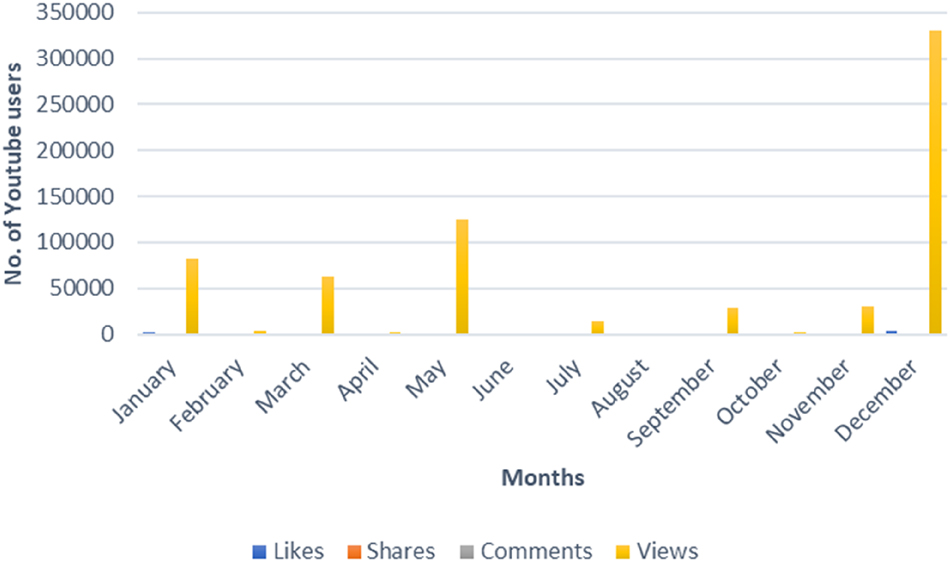

The data presented in Figure 4 reveals YouTube user engagement with videos related to heritage sites in Bishnupur, West Bengal, based on the months in which videos were uploaded. Notably, December emerged as the most successful month, garnering the highest engagement with 3,496 likes, 298 comments, and an impressive 331,096 views. This suggests that videos released during the holiday season or featuring compelling content garnered the most attention. January also experienced robust engagement with 2,066 likes, 371 comments, and 82,626 views, indicating a favourable response to content uploaded at the beginning of the year. In March, 1,116 likes, 174 comments, and 62,983 views showed a continued interest in heritage site videos. May exhibited a resurgence in engagement with 1,408 likes, 64 comments, and 125,464 views, suggesting the appeal of content during this month. Videos uploaded in November also maintained moderate engagement. Conversely, videos uploaded in February, April, June, and August had lower levels of engagement, indicating that content in these months did not resonate as strongly with the audience.

Response of YouTube users towards heritage sites of the study area.

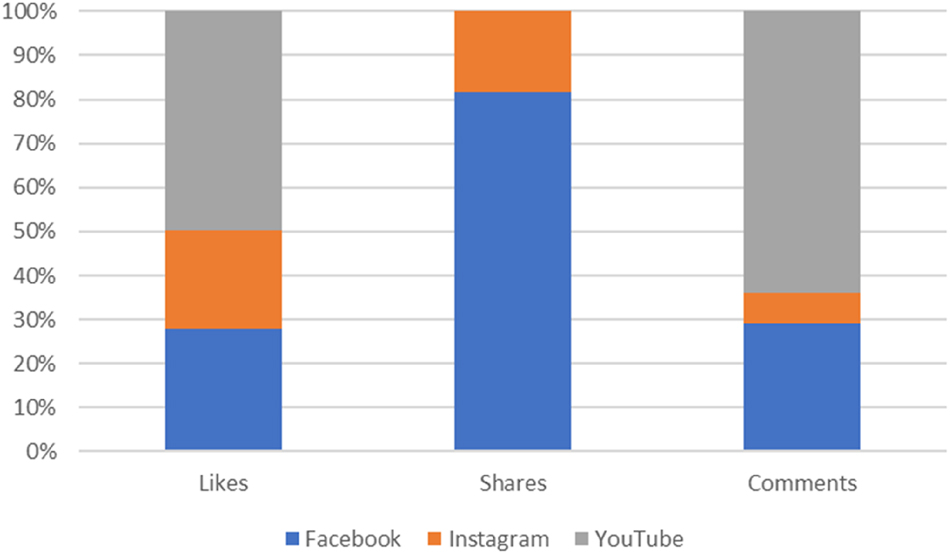

4.4 Engagement Metrics with Bishnupur Heritage Sites

Figure 5 illustrates the engagement metrics, including likes, shares, and comments, for promoting heritage sites in Bishnupur on three different social media platforms: Facebook, Instagram, and YouTube. On Facebook the content received a significant number of likes (5,604), indicating a considerable level of approval and interest among users. Additionally, 365 shares signify that the content was compelling enough to be shared with others, expanding its reach. The 624 comments demonstrate an active engagement, with users actively interacting by leaving their thoughts, questions, and feedback, which is essential for fostering conversations around heritage sites. On Instagram the content garnered a substantial number of likes (4,553), showing that users on this platform expressed their approval and appreciation. While the number of shares (82) is lower than Facebook it is still noteworthy, indicating that the content resonated with some users enough to be shared. The 152 comments reflect user engagement where people interacted with the content by providing their thoughts or feedback, which is valuable for encouraging conversations and connections. YouTube received a significant number of likes (10,017), demonstrating strong approval and engagement with the video content. While there were no shares, which is common on YouTube due to its video format, the 1,375 comments reveal a high level of user interaction. Users actively discussed or reacted to the video content, indicating a vibrant and engaged community on this platform.

Engagement metrics, including likes, shares, and comments, for promoting heritage sites in the study area.

4.5 Engagement Rates with Bishnupur Heritage Sites

Table 2 offers insights into the effectiveness of various social media platforms in engaging users with content promoting heritage sites in Bishnupur, West Bengal. The engagement rates provide a clear indication of how well each platform captures the audience’s interest. Instagram emerges as the frontrunner with a notably high engagement rate of 1.243 %. This implies that for every 1,000 users exposed to heritage site content on Instagram approximately 1.243 % of them actively engage with it. The visually-centric and interactive nature of Instagram seems to resonate well with the target audience interested in heritage sites. On the other hand, Facebook lags behind with the lowest engagement rate of 0.063 which suggests that for every 1,000 Facebook users encountering heritage site content only 0.063 % of them interact with it. Facebook may require a revaluation of content or engagement strategies to enhance its effectiveness in this context. YouTube falls between the two with an engagement rate of 0.743 %; while not as high as Instagram, it surpasses Facebook and represents a moderate level of engagement. YouTube’s video-focused platform offers an effective means of engaging users but there is room for optimization to boost the engagement rate.

Social media-wise engagement rate in promoting heritage sites in the study area.

| Sl. No. | Social media platform | Engagement rate (%) | Classification |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.063 | Low engagement | |

| 2 | 1.243 | Low engagement | |

| 3 | YouTube | 0.743 | Low engagement |

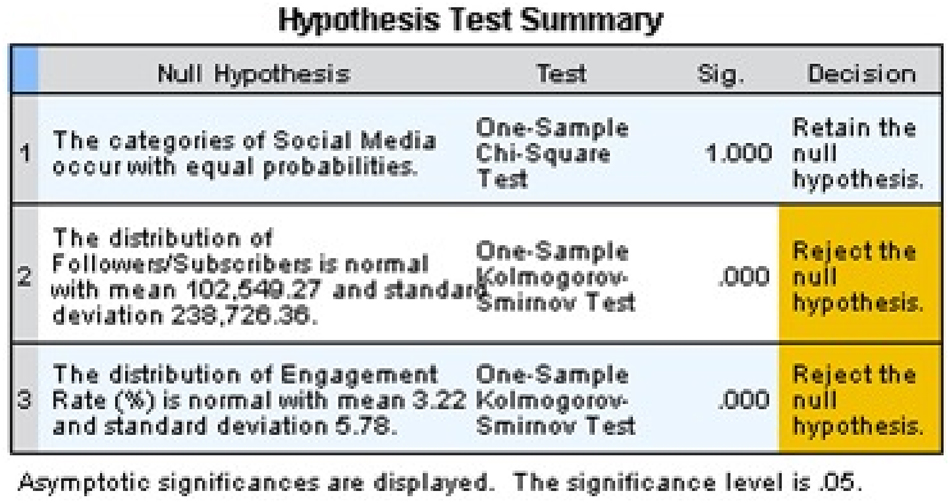

4.6 Analysis of Engagement Rate Distribution and Hypothesis Testing Results

Figure 6 suggests that the distribution of Engagement rate (%) is not normal with the specified mean and standard deviation. The significance level for all the tests is set at 0.05 which means that a p-value less than 0.05 is considered statistically significant. In both Null Hypothesis Tests 2 and 3 the p-values are extremely small (0.000), indicating strong evidence to reject the null hypotheses. This means that the distributions of Followers/Subscribers and Engagement Rate (%) do not match the specified normal distributions. In contrast, Null Hypothesis Test 1 has a p-value of 1.000, indicating that there is no significant evidence to reject the null hypothesis. This suggests that the categories of social media occur with equal probabilities, at least based on the data and statistical test used.

Hypothesis test summary.

4.7 Role of Social Media in Promoting and Preserving Heritage Sites

The thematic analysis, presented in Table 3, highlights the multifaceted role of social media in promoting and preserving heritage sites, particularly in Bishnupur. It reveals that social media enhances awareness and visibility, enabling both global outreach and local engagement through visually appealing content and strategic hashtags. Community engagement thrives as users share personal stories and organize group visits, fostering a sense of belonging around cultural appreciation. Storytelling enriches the cultural narrative, combining personal experiences with local legends, while educational content raises awareness of historical significance and traditional crafts. User-generated content showcases diverse perspectives, further enhancing the narrative of heritage preservation. Social media also mobilizes community action for preservation efforts through advocacy campaigns and volunteer initiatives. However, the challenge of misinformation underscores the need for credible sources and responsible sharing practices. Overall, social media emerges as a powerful tool for connecting audiences with cultural heritage, fostering meaningful engagement and driving preservation efforts.

Impact of social media on heritage site promotion and preservation: Insights from thematic analysis.

| Main theme | Sub-themes | Description | Case-specific examples from engagement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Awareness and visibility | Global reach and local engagement | Social media platforms help heritage sites gain visibility, allowing for both global outreach and localized engagement among community members. | A viral post featuring a stunning photo of Bishnupur’s terracotta temples attracted attention from international users, leading to inquiries about travel. Local tourism boards used hashtags to promote events, increasing attendance at heritage site festivals. |

| Community engagement | User interaction and shared experiences | Social media fosters a sense of belonging by allowing users to interact, share experiences, and build communities around heritage appreciation. | Users posting about family visits to Bishnupur, tagging friends, and reminiscing about childhood trips which sparked conversations about cultural heritage. Facebook groups dedicated to heritage tourism where users exchange tips and organize group visits. |

| Storytelling and cultural narratives | Personal narratives and local legends | Platforms facilitate storytelling that highlights the cultural significance of heritage sites, enriching users’ understanding and appreciation. | Videos sharing local legends about the craftsmanship behind Bishnupur pottery, encouraging users to comment with their interpretations and related stories. Instagram posts that weave personal experiences with historical facts, creating a narrative that engages audiences. |

| Educational content | Informative posts and interactive learning | Social media provides an avenue for sharing educational content, raising awareness about the history and importance of heritage sites. | Posts explaining the techniques of terracotta artistry in Bishnupur led to discussions among users about traditional crafts and their relevance today. Live Q&A sessions on platforms like Instagram where experts answer questions about Bishnupur’s heritage and history. |

| User-generated content | Community contributions and diverse perspectives | Encouraging user-generated content enhances narratives around heritage preservation, showcasing varied experiences and viewpoints from different users. | A campaign inviting users to share their own photos and experiences visiting Bishnupur which resulted in a collage of perspectives that highlighted the site’s appeal. Users posting their artistic interpretations of Bishnupur sites, enriching the conversation with diverse creative expressions. |

| Call to action for preservation | Advocacy initiatives and volunteer mobilization | Social media campaigns can effectively rally support for heritage preservation, encouraging participation in conservation initiatives. | Posts highlighting the need for restoration work at Bishnupur temples led to organized volunteer events where users signed up to assist with cleanup and maintenance efforts. Fundraising campaigns on social media to support local preservation projects generated significant community support. |

| Impact of visual appeal | Aesthetic engagement and visual storytelling | High-quality, visually appealing content captures user attention and drives engagement, emphasizing the importance of aesthetics in promoting heritage sites. | Eye-catching photos of Bishnupur’s festivals or architecture receiving thousands of likes and shares, encouraging users to plan visits. Videos that combine stunning visuals with narratives about the sites, making the content more engaging and shareable. |

| Challenges of misinformation | Inaccurate representation and importance of verification | The spread of inaccurate information can hinder preservation efforts, underscoring the need for credible sources and content verification. | Discussions on social media addressing misleading claims about the history of certain sites in Bishnupur, prompting users to fact-check and promote accurate narratives. Initiatives to educate users on how to verify information about heritage sites before sharing, fostering a culture of responsible content sharing. |

5 Discussions

5.1 Diverse Engagement Across Platforms

The analysis of engagement metrics across Facebook, Instagram, and YouTube highlights distinct patterns valuable for promoting heritage sites. Facebook leads with 5,604 likes, indicating strong user approval and potential for increased awareness, which can drive traffic to heritage locations (Timothy 2020). In contrast, Instagram, with 4,553 likes, emphasizes the importance of visual content and storytelling, effectively engaging users, particularly younger audiences (Kádár and Klaniczay 2022; MacDowall and Budge 2021). YouTube excels with 10,017 likes and 1,375 comments, showcasing its strength in fostering community engagement through video content, which facilitates in-depth storytelling and educational opportunities (Rotman and Preece 2010; Pietrobruno 2018).

The findings from this engagement analysis can be extended to inform practices at other heritage sites. For instance, heritage managers could leverage the strengths of each platform by tailoring content to fit the unique engagement styles of their audiences. Facebook could be used to share updates and promotional events while Instagram can focus on high-quality visuals and storytelling that resonate with users. YouTube can serve as a platform for deeper educational content such as virtual tours or expert discussions about the sites. Furthermore, these insights suggest important policy implications for heritage site promotion. Heritage organizations and policymakers could develop strategic social media campaigns that align with user engagement patterns, emphasizing visual storytelling and community interaction. By adopting a more integrated social media strategy that utilizes the strengths of each platform, heritage sites can enhance their visibility, engage a wider audience, and foster a stronger sense of community around cultural heritage preservation (Kádár and Klaniczay 2022).

5.2 Likes Reflect Approval and Interest

Likes on social media serve as a crucial form of positive feedback, reflecting user approval and appreciation for content related to heritage sites (Lowe-Calverley and Grieve 2018). Each “like” signifies an emotional connection, indicating that users resonate with the historical or cultural significance of these sites, whether through architectural beauty or compelling storytelling (Latif et al. 2020; Liu et al. 2017; Watson, Barnes, and Bunning 2019). The visual appeal of heritage sites plays a key role in attracting likes as captivating images of intricate carvings or grand structures engage users and underscore the importance of presenting these sites attractively (De las Heras-Pedrosa et al. 2020). On Instagram the visual nature of the platform amplifies the impact of likes on content visibility; posts that receive high engagement are more likely to reach broader audiences (Rietveld et al. 2020). This increased exposure is beneficial for heritage site promotion, ensuring that more users learn about the cultural and historical significance of these locations. Furthermore, likes often function as a form of user-generated content where users share their own images or experiences, thereby endorsing the heritage sites and expanding the reach of the message (Munoz and Towner 2018).

The insights drawn from these engagement metrics can inform practices at other heritage sites. For instance, effective strategies could include enhancing visual storytelling to attract more likes and thus greater visibility. Additionally, heritage site managers can encourage user-generated content by hosting photo contests or campaigns that prompt visitors to share their experiences. Policy implications may involve developing guidelines for leveraging social media analytics to improve engagement and outreach strategies, ultimately fostering a stronger community connection to cultural heritage. Recent studies further support these findings, emphasizing the importance of interactive and visually appealing content in engaging diverse audiences (Vlassis 2021).

5.3 Shares Indicate Compelling Content

Shares are a crucial indicator of compelling content on social media, serving as a powerful amplification mechanism for heritage site promotion (Moran, Muzellec, and Johnson 2020). When users share posts related to heritage sites they not only express their appreciation but also extend the content’s reach to their networks, effectively acting as digital word-of-mouth marketers (Hays, Page, and Buhalis 2013). This sharing behavior functions as a form of endorsement, suggesting that the content successfully conveys the cultural, historical, or aesthetic value of the site (Macarthy 2021). In the context of heritage site promotion such endorsements are significant; they signal to potential visitors that the site is worth exploring.

The act of sharing also serves as social proof. When users observe that a post has been shared multiple times it instils trust and credibility, reassuring potential visitors of the site’s worth (Amblee and Bui 2011). This aspect is particularly vital for heritage site promotion as it can lead to increased interest and visitation. As shares broaden the audience content can reach individuals who may not have otherwise encountered it, thereby expanding the awareness of cultural assets (Leonardi 2018). Moreover, shareable content fosters a sense of community among users who are passionate about preserving and promoting these sites, building networks of heritage enthusiasts who engage with and advocate for the protection of cultural assets (Lieb 2012).

Heritage managers should focus on producing high-quality visual and narrative content that resonates with audiences and encourages sharing. Strategies such as storytelling, highlighting unique aspects of the heritage site, and showcasing community events can make posts more compelling and shareable. Additionally, policy implications arise from these insights. Heritage organizations should consider incorporating social media engagement metrics, including shares, into their evaluation frameworks for heritage site promotion. By understanding what content resonates most with audiences they can refine their marketing strategies to enhance visibility and engagement. Collaborative campaigns that encourage user-generated content and sharing can also be developed, fostering community involvement and advocacy for heritage preservation.

5.4 Value of Comments for Conversations

The value of comments in conversations about heritage sites extends beyond individual engagement; it has broader implications for practices and policies across various sites. First, heritage sites can learn from the importance of comment engagement to develop targeted strategies that encourage visitor interaction. By fostering an environment where visitors feel comfortable sharing their thoughts, questions, and experiences, sites can create a more vibrant community around their narratives. For instance, hosting question and answer (Q&A) sessions or encouraging visitors to share their own stories can enhance engagement and deepen connections to the site’s history (Royo-Vela and Casamassima 2011).

Moreover, insights drawn from user comments can inform the creation of educational materials and programming. By analyzing frequently asked questions and popular topics of discussion, heritage sites can tailor their exhibits, tours, and online content to address visitor interests and knowledge gaps. This responsive approach not only enriches the visitor experience but also reinforces the site’s relevance in a rapidly changing cultural landscape (Argyriou, Economou, and Bouki 2020). Additionally, heritage sites should recognize the potential of comment sections as platforms for community building. Encouraging dialogue among visitors fosters a sense of belonging and shared passion for cultural preservation. Initiatives such as user-generated content contests or collaborative storytelling projects can enhance this community spirit and attract diverse audiences (Alexander 2017).

The constructive criticism and feedback gleaned from comments can guide decisions related to site management and visitor services. By actively monitoring and responding to visitor input heritage sites can demonstrate a commitment to continuous improvement, ensuring that policies reflect the needs and desires of the community (Palomba et al. 2015). Furthermore, comments often highlight areas where visitors feel underserved or face barriers. This feedback can drive policies aimed at making heritage sites more inclusive and accessible, ensuring that diverse audiences can engage fully with the site’s offerings. Implementing changes based on visitor feedback not only improves the experience but also aligns with broader goals of social equity and inclusion in cultural heritage preservation. The dialogue fostered through comments can illuminate issues of cultural sensitivity and representation. Heritage sites can use these insights to develop policies that prioritize respectful and inclusive narratives, ensuring that the voices of all stakeholders are considered in the site’s interpretation and presentation (Zhuang et al. 2023).

5.5 Platform-Specific Strategies

Each social media platform has unique strengths that heritage sites can leverage to enhance engagement and outreach. YouTube’s video-centric approach is ideal for in-depth storytelling and educational content, allowing for the creation of documentary-style videos that highlight historical significance and address frequently asked questions (Nikolov 2022). Facebook’s versatility enables the sharing of various content types such as historical photographs and text-based narratives while its features like sharing capabilities and event promotions can broaden reach and stimulate community discussions (Lingel and Golub 2015). Instagram excels in visual storytelling, making it perfect for showcasing the beauty of heritage sites through high-quality images and short videos. The effective use of hashtags and location tags enhances content discoverability, and encouraging user-generated content fosters authenticity and relatability in the site’s online presence (Guo 2023).

Maintaining consistency across social media platforms while tailoring content to each platform’s strengths is essential for heritage sites. Cross-promotion helps create a unified brand presence, ensuring audiences are aware of content on multiple platforms (Labadens 2018). This holistic approach caters to diverse audience preferences and fosters a cohesive community. To adapt strategies effectively it is crucial to monitor user behavior and engagement metrics; for example, Instagram users typically prefer visually appealing, concise content while YouTube users engage more with longer narratives (Parmelee, Perkins, and Beasley 2023). Heritage sites should utilize platform-specific features – such as Instagram Stories, Facebook Live, and YouTube Premiere – to enhance engagement through interactive experiences like live Q&A sessions and behind-the-scenes content. Integrating these strategies can inform guidelines for digital engagement in heritage site management. By training staff on effective social media use and prioritizing diverse voices in digital content, heritage sites can ensure their narratives resonate with contemporary audiences.

5.6 Community Building

Community building in the context of heritage sites involves bringing together individuals who share a passion for history, culture, and the preservation of these assets (Harvey 2016). The significant engagement metrics, such as likes, shares, and comments, indicate that there is a sizeable group of enthusiasts and supporters. Heritage sites often evoke strong emotions and a sense of awe (Pearce, Strickland-Munro, and Moore 2017). Users who engage with content related to these sites are likely to have their own personal experiences and memories (Cannelli and Musso 2022). Comment sections provide a platform for users to share these experiences, creating a sense of camaraderie and shared storytelling (Lund, Cohen, and Scarles 2018). Engaging with users through social media can lead to networking opportunities and collaboration. Users who are passionate about heritage sites may want to connect with others who share similar interests. This can lead to partnerships, collaborative projects, or joint initiatives aimed at promoting and preserving these cultural assets (Markham, Gentile, and Graham 2017).

Building a community around heritage sites can serve as an educational platform (Haddad 2016). Enthusiasts can exchange knowledge, share historical facts, and raise awareness about the significance of these sites (Tsimonis and Dimitriadis 2014). This educational aspect is vital for encouraging future generations to appreciate and protect their cultural heritage. Engaged users are more likely to advocate for the preservation and protection of these sites. They can also provide support to ongoing conservation efforts, volunteer activities, or fundraising campaigns. It can contribute to the preservation of these cultural assets by generating public interest, donations, and support for heritage site maintenance and restoration. This not only benefits the sites themselves but also the surrounding communities. By engaging with users through likes, shares, and comments, a sense of belonging and attachment to heritage sites is fostered. Users who actively participate in discussions and share their experiences feel a personal connection to these cultural assets. This connection can lead to increased visitation and a greater sense of responsibility in preserving these sites for future generations.

6 Policy Perspectives

To effectively promote and preserve heritage sites worldwide, it is essential to design social media campaigns that reflect the unique cultural and historical attributes of these sites, similar to successful initiatives observed globally. For instance, the “Keep It Wild” campaign in New Zealand leverages social media to connect local communities and tourists, enhancing engagement while promoting sustainable practices (Butler and Thompson-Carr 2024). Tailoring campaigns to resonate with both local and global audiences can significantly generate interest and enhance engagement.

Education is crucial in heritage site promotion. Implementing educational initiatives through social media can inform visitors about the historical and cultural significance of these sites. For example, the use of multimedia content – such as videos, infographics, and virtual tours – has been effectively employed by institutions like the Smithsonian in the U.S. to engage broader audiences and make learning accessible (Chase, Hoffman, and Lasnoski 2024).

Addressing challenges such as overcrowding and environmental preservation at heritage sites requires comprehensive strategies. The management of popular destinations like Venice in Italy has involved implementing crowd management solutions and responsible tourism practices alongside investments in infrastructure to enhance visitor comfort while safeguarding heritage (Bertocchi and Visentin 2019). Establishing a crisis management plan is also vital; the response strategies developed during the COVID-19 pandemic have shown the importance of being prepared for potential disruptions, enabling rapid recovery in tourism (Collins-Kreiner and Ram 2021).

Active involvement of local communities is paramount for the preservation and promotion of heritage sites. Global initiatives such as UNESCO’s “Heritage for Peace” program emphasize community engagement in heritage conservation, fostering a sense of ownership and advocacy (Radun, Sossai, and Coelho 2022). Collaborating with social media influencers, travel bloggers, and cultural enthusiasts can significantly extend the reach of heritage sites similar to how the “Instagrammable Moments” campaign has successfully showcased local culture in various destinations.

User-generated content is another powerful tool for heritage site promotion. Encouraging visitors to share their experiences – like the #MyHeritage campaign in the UK – can increase engagement and reach. Hosting contests and interactive campaigns motivates users to contribute to the promotion effort, further amplifying visibility (Cui, Kumar, and Orr 2023). Leveraging social media for real-time updates on events, exhibitions, and conservation efforts is vital; timely information can attract visitors and maintain their interest.

Promoting sustainable tourism practices and responsible travel behaviors through social media is essential. Initiatives like the “Travel Responsibly” campaign by the World Wildlife Fund educate visitors on the importance of conserving heritage sites and the environment, thereby contributing to their preservation (Sumner 2024). Implementing social media monitoring and analytics tools is necessary to track campaign effectiveness, engagement levels, and visitor sentiment. Regular data analysis can inform decisions and adjustments to strategies.

Lastly, a commitment to ongoing study and data collection on the impact of social media in heritage site promotion is critical. Staying updated on evolving social media trends and adapting strategies, as seen with successful case studies globally, ensures effectiveness in the digital landscape. By adopting a holistic approach that combines tailored content, education, responsible tourism, and community engagement, heritage sites can harness the full potential of social media to safeguard their cultural legacy while fostering socio-economic growth through tourism.

7 Conclusions

The relationship between heritage sites and social media plays a crucial role in cultural preservation, promotion, and economic growth, particularly in West Bengal, India, aligning with several Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). This study highlights how platforms like Facebook, Instagram, and YouTube can transform heritage tourism by analyzing engagement metrics – likes, shares, and comments – to reveal connections between heritage sites and their audiences. While heritage sites are vital for reflecting history and driving tourism-related economic growth, challenges such as overcrowding, preservation issues, and sustainability have been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. Social media serves as an essential tool for addressing these challenges, allowing heritage sites to convey their significance and engage with potential visitors. Region-specific strategies, including tailored campaigns, educational initiatives, crisis management, and community involvement, are crucial for maximizing social media’s impact in line with the SDGs. By adopting sustainable practices and fostering user-generated content, these efforts can protect cultural heritage and promote economic growth through tourism. Ultimately, this study offers a blueprint for leveraging social media to shape a sustainable cultural landscape in support of global development goals.

References

Adams, K. M., J. Choe, M. Mostafanezhad, and G. T. Phi. 2022. “(Post-) Pandemic Tourism Resiliency: Southeast Asian Lives and Livelihoods in Limbo.” In Recentering Tourism Geographies in the ‘Asian Century’, 267–88. London, UK: Routledge.10.4324/9781003265429-14Search in Google Scholar

Alexander, B. 2017. The New Digital Storytelling: Creating Narratives With New Media – Revised and Updated Edition. USA: Bloomsbury Publishing.10.5040/9798400690839Search in Google Scholar

Alonso, A. D., S. K. Kok, A. Bressan, M. O’Shea, N. Sakellarios, A. Koresis, M. A. B. Solis, and L. J. Santoni. 2020. “COVID-19, Aftermath, Impacts, and Hospitality Firms: An International Perspective.” International Journal of Hospitality Management 91: 102654. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102654.Search in Google Scholar

Amblee, N., and T. Bui. 2011. “Harnessing the Influence of Social Proof in Online Shopping: The Effect of Electronic Word of Mouth on Sales of Digital Microproducts.” International Journal of Electronic Commerce 16 (2): 91–114. https://doi.org/10.2753/jec1086-4415160205.Search in Google Scholar

Apaydin, V. 2020. “The Interlinkage of Cultural Memory, Heritage and Discourses of Construction, Transformation and Destruction.” In Critical Perspectives on Cultural Memory and Heritage, 13–30. Berkeley, USA: University of California Press.10.2307/j.ctv13xpsfp.7Search in Google Scholar

Arasli, H., M. Abdullahi, and T. Gunay. 2021. “Social Media as a Destination Marketing Tool for a Sustainable Heritage Festival in Nigeria: A Moderated Mediation Study.” Sustainability 13 (11): 6191. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13116191.Search in Google Scholar

Argyriou, L., D. Economou, and V. Bouki. 2020. “Design Methodology for 360° Immersive Video Applications: The Case Study of a Cultural Heritage Virtual Tour.” Personal and Ubiquitous Computing 24 (6): 843–59. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00779-020-01373-8.Search in Google Scholar

Aruljothi, C., and S. Ramaswamy. 2019. Pilgrimage Tourism: Socio-economic Analysis. Chennai, India: MJP Publisher.Search in Google Scholar

Beel, D., and C. Wallace. 2018. “Gathering Together: Social Capital, Cultural Capital and the Value of Cultural Heritage in a Digital Age.” Social and Cultural Geography 21 (5): 697–717. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649365.2018.1500632.Search in Google Scholar

Bertocchi, D., and F. Visentin. 2019. “The Overwhelmed City’: Physical and Social Over-capacities of Global Tourism in Venice.” Sustainability 11 (24): 6937. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11246937.Search in Google Scholar

Butler, R., and A. Thompson-Carr. 2024. The Routledge Handbook of Tourism and Indigenous Peoples. London. Routledge, 2024.10.4324/9781003230335Search in Google Scholar

Cannelli, B., and M. Musso. 2022. “Social Media as Part of Personal Digital Archives: Exploring Users’ Practices and Service Providers’ Policies Regarding the Preservation of Digital Memories.” Archival Science 22 (2): 259–83. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10502-021-09379-8.Search in Google Scholar

Cantoni, L. 2020. “Digital Transformation, Tourism and Cultural Heritage.” In A Research Agenda for Heritage Tourism, 235–52. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing.10.4337/9781789903522.00025Search in Google Scholar

Cave, C., and E. Negussie. 2017. World Heritage Conservation. London, UK: Routledge.10.4324/9781315851631Search in Google Scholar

Chase, E., L. Hoffman, and M. Lasnoski. 2024. Cultural Heritage Conservation for Early Learners. London, UK: Routledge.10.4324/9781003333210Search in Google Scholar

Chattopadhyay, R. 2003. Shilpa O Sansknti Bankura. Kolkata: Dev Sahitya Kutir Pvt Ltd.Search in Google Scholar

Chhabra, D. 2021. Resilience, Authenticity and Digital Heritage Tourism. London, UK: Routledge.10.4324/9781003098836Search in Google Scholar

Chowdhury, R. 2006. “Bankura Jelar Shilpa Sansknti.” In Bankura Nana Range Bona, edited by S. Adhikary, 12–4. Kolkata: Tamon Prakashan.Search in Google Scholar

Collins-Kreiner, N., and Y. Ram. 2021. “National Tourism Strategies during the Covid-19 Pandemic.” Annals of Tourism Research 89: 103076. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2020.103076.Search in Google Scholar

Correia, L. F. R., R. D. S. Bartholo, A. W. Brufato, and E. C. T. Sanchez. 2023. “Toward a Digital Twin for Cultural Heritage.” In Advances in Tourism, Technology and Systems: Selected Papers from ICOTTS 2022, Vol. 1, 419–30. Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore.10.1007/978-981-99-0337-5_35Search in Google Scholar

Cui, T., P. Kumar, and S. A. Orr. 2023. “Connecting Characteristics of Social Media Activities of a Heritage Organisation to Audience Engagement.” Digital Applications in Archaeology and Cultural Heritage 28: e00253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.daach.2022.e00253.Search in Google Scholar

De las Heras-Pedrosa, C., E. Millan-Celis, P. P. Iglesias-Sánchez, and C. Jambrino-Maldonado. 2020. “Importance of Social Media in the Image Formation of Tourist Destinations from the Stakeholders’ Perspective.” Sustainability 12 (10): 4092. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12104092.Search in Google Scholar

Di Fiore, L. 2020. “Heritage and Food History: A Critical Assessment.” In Food Heritage and Nationalism in Europe. Abingdon, UK: Taylor & Francis.10.4324/9780429279751-2Search in Google Scholar

Economou, M. 2015. “Heritage in the Digital Age.” In A Companion to Heritage Studies, 215–28. Chichester, UK: Wiley-Blackwell.10.1002/9781118486634.ch15Search in Google Scholar

Faria, C., P. C. Remoaldo, J. A. Alves, and H. S. Lopes. 2024. “A Bibliometric Analysis on Creative Tourism (2002–2022).” Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change 22 (3): 333–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/14766825.2024.2394896.Search in Google Scholar

Grincheva, N. 2020. Museum Diplomacy in the Digital Age. London, UK: Routledge.10.4324/9781351251006Search in Google Scholar

Guo, M. 2023. Modeling Visual Rhetorics for Persuasive Media Through Self-supervised Learning. University of Pittsburgh. PhD diss. https://d-scholarship.pitt.edu/45148/ (accessed September 9, 2024).Search in Google Scholar

Guo, Y., M. Yu, and Y. Zhao. 2024. “Impact of Destination Advertising on Tourists’ Visit Intention: The Influence of Self-Congruence, Self-Confidence, and Destination Reputation.” Journal of Destination Marketing and Management 31: 100852. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2023.100852.Search in Google Scholar

Haddad, N. A. 2016. “Multimedia and Cultural Heritage: A Discussion for the Community Involved in Children’s Heritage Edutainment and Serious Games in the 21st Century.” Virtual Archaeology Review 7 (14): 61. https://doi.org/10.4995/var.2015.4191.Search in Google Scholar

Harrison, R., C. DeSilvey, C. Holtorf, S. Macdonald, N. Bartolini, E. Breithoff, H. Fredheim, et al.. 2020. Heritage Futures: Comparative Approaches to Natural and Cultural Heritage Practices. London, UK: UCL press.10.2307/j.ctv13xps9mSearch in Google Scholar

Harvey, D. C. 2016. “The History of Heritage.” In The Routledge Research Companion to Heritage and Identity, 19–36. London, UK: Routledge.10.4324/9781315613031-1Search in Google Scholar

Hays, S., S. J. Page, and D. Buhalis. 2013. “Social Media as a Destination Marketing Tool: Its Use by National Tourism Organisations.” Current Issues in Tourism 16 (3): 211–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2012.662215.Search in Google Scholar

Honey, M., and K. Frenkiel, eds. 2021. Overtourism: Lessons For a Better Future. Washington, D.C., USA: Island Press.Search in Google Scholar

Jia, Z., Y. Jiao, W. Zhang, and Z. Chen. 2022. “Rural Tourism Competitiveness and Development Mode, a Case Study from Chinese Township Scale Using Integrated Multi-Source Data.” Sustainability 14 (7): 4147. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14074147.Search in Google Scholar

Kádár, B., and J. Klaniczay. 2022. “Branding Built Heritage through Cultural Urban Festivals: An Instagram Analysis Related to Sustainable Co-creation, in Budapest.” Sustainability 14 (9): 5020. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14095020.Search in Google Scholar

Kamariotou, V., M. Kamariotou, and F. Kitsios. 2021. “Strategic Planning for Virtual Exhibitions and Visitors’ Experience: A Multidisciplinary Approach for Museums in the Digital Age.” Digital Applications in Archaeology and Cultural Heritage 21: e00183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.daach.2021.e00183.Search in Google Scholar

Kim, C., and S. U. Yang. 2017. “Like, Comment, and Share on Facebook: How Each Behavior Differs from the Other.” Public Relations Review 43 (2): 441–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2017.02.006.Search in Google Scholar

Koens, K., A. Postma, and B. Papp. 2018. “Is Overtourism Overused? Understanding the Impact of Tourism in a City Context.” Sustainability 10 (12): 4384. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10124384.Search in Google Scholar

Koukopoulos, Z., D. Koukopoulos, and J. J. Jung. 2017. “A Trustworthy Multimedia Participatory Platform for Cultural Heritage Management in Smart City Environments.” Multimedia Tools and Applications 76 (24): 25943–81. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11042-017-4785-8.Search in Google Scholar

Kumar, S., V. Kumar, I. K. Bhatt, S. Kumar, and K. Attri. 2023. “Digital Transformation in Tourism Sector: Trends and Future Perspectives from a Bibliometric-Content Analysis.” Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Insights 7 (3): 1553–76. https://doi.org/10.1108/jhti-10-2022-0472.Search in Google Scholar

Labadens, N. 2018. How to Crush Social Media in Only 2 Minutes a Day: YouTube, Google, Amazon, Cross Promotion, Blogs and Shapr, Vol. 2. Lannconsultings.com. Createspace Independent Publishing Platform, Scotts Valley, California, USA.Search in Google Scholar

Latif, K., M. Y. Malik, A. H. Pitafi, S. Kanwal, and Z. Latif. 2020. “If You Travel, I Travel: Testing a Model of when and How Travel-Related Content Exposure on Facebook Triggers the Intention to Visit a Tourist Destination.” Sage Open 10 (2): 1–12, https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244020925511.Search in Google Scholar

Leonardi, P. M. 2018. “Social Media and the Development of Shared Cognition: The Roles of Network Expansion, Content Integration, and Triggered Recalling.” Organization Science 29 (4): 547–68. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2017.1200.Search in Google Scholar

Leung, Y. F., A. Spenceley, G. Hvenegaard, R. Buckley, and C. Groves. 2018. Tourism and Visitor Management in Protected Areas: Guidelines for Sustainability, Vol. 27. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN.10.2305/IUCN.CH.2018.PAG.27.enSearch in Google Scholar

Li, Y., C. Lau, and P. Su. 2020. “Heritage Tourism Stakeholder Conflict: A Case of a World Heritage Site in China.” Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change 18 (3): 267–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/14766825.2020.1722141.Search in Google Scholar

Lieb, R. 2012. Content Marketing: Think Like a Publisher – How to Use Content to Market Online and in Social Media. Indianapolis, USA: Que Publishing.Search in Google Scholar

Lingel, J., and A. Golub. 2015. “In Face on Facebook: Brooklyn’s Drag Community and Sociotechnical Practices of Online Communication.” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 20 (5): 536–53. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcc4.12125.Search in Google Scholar

Liu, J., C. Li, Y. G. Ji, M. North, and F. Yang. 2017. “Like it or Not: The Fortune 500’s Facebook Strategies to Generate Users’ Electronic Word-Of-Mouth.” Computers in Human Behavior 73: 605–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.03.068.Search in Google Scholar

Lowe-Calverley, E., and R. Grieve. 2018. “Thumbs up: A Thematic Analysis of Image-Based Posting and Liking Behaviour on Social Media.” Telematics and Informatics 35 (7): 1900–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2018.06.003.Search in Google Scholar

Lund, N. F., S. A. Cohen, and C. Scarles. 2018. “The Power of Social Media Storytelling in Destination Branding.” Journal of Destination Marketing and Management 8: 271–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2017.05.003.Search in Google Scholar

Macarthy, A. 2021. “500 Social Media Marketing Tips: Essential Advice.” In Hints and Strategy for Business: Facebook, Twitter, Pinterest, Google+, YouTube, Instagram, LinkedIn, and Mor. Washington, D.C., USA: Kindle Edition.Search in Google Scholar

MacDowall, L., and K. Budge. 2021. Art After Instagram: Art Spaces, Audiences, Aesthetics. London, UK: Routledge.10.4324/9781003001799Search in Google Scholar

Markham, M. J., D. Gentile, and D. L. Graham. 2017. “Social Media for Networking, Professional Development, and Patient Engagement.” American Society of Clinical Oncology Educational Book 37: 782–7. https://doi.org/10.1200/edbk_180077.Search in Google Scholar

Meskell, L. 2018. A Future in Ruins: UNESCO, World Heritage, and the Dream of Peace. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Moran, G., L. Muzellec, and D. Johnson. 2020. “Message Content Features and Social Media Engagement: Evidence from the Media Industry.” Journal of Product and Brand Management 29 (5): 533–45. https://doi.org/10.1108/jpbm-09-2018-2014.Search in Google Scholar

Munoz, C. L., and T. L. Towner. 2018. “The Image Is the Message: Instagram Marketing and the 2016 Presidential Primary Season.” In Social Media, Political Marketing and the 2016 US Election, 84–112. London, UK: Routledge.10.4324/9781351105521-5Search in Google Scholar

Nikolov, M. 2022. Is YouTube History an Effective Tool for Teaching History to Secondary Schoolers? http://arno.uvt.nl/show.cgi?fid=160752 (accessed September 10, 2024).Search in Google Scholar

Noaime, E., and M. M. Alnaim. 2023. “Examining the Symbolic Dimension of Aleppo’s Historical Landmarks.” Alexandria Engineering Journal 78: 292–305. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aej.2023.07.054.Search in Google Scholar

Palomba, F., M. Linares-Vásquez, G. Bavota, R. Oliveto, M. D. Penta, D. Poshyvanyk, and A. D. Lucia. 2015. “User Reviews Matter! Tracking Crowdsourced Reviews to Support Evolution of Successful Apps.” In: 2015 IEEE International Conference on Software Maintenance and Evolution (ICSME), 291–300. Piscataway, USA: IEEE.10.1109/ICSM.2015.7332475Search in Google Scholar

Parmelee, J. H., S. C. Perkins, and B. Beasley. 2023. “Personalization of Politicians on Instagram: What Generation Z Wants to See in Political Posts.” Information, Communication and Society 26 (9): 1773–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118x.2022.2027500.Search in Google Scholar

Pearce, J., J. Strickland-Munro, and S. A. Moore. 2017. “What Fosters Awe-Inspiring Experiences in Nature-Based Tourism Destinations?” Journal of Sustainable Tourism 25 (3): 362–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2016.1213270.Search in Google Scholar

Pietrobruno, S. 2018. “YouTube Flow and the Transmission of Heritage: The Interplay of Users, Content, and Algorithms.” Convergence 24 (6): 523–37. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354856516680339.Search in Google Scholar

Polat, E., F. Çelik, B. Ibrahim, and D. Gursoy. 2024. “Past, Present, and Future Scene of Influencer Marketing in Hospitality and Tourism Management.” Journal of Travel and; Tourism Marketing 41 (3): 322–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2024.2317741.Search in Google Scholar

Rachman, Y. B., S. M. G. Tambunan, M. K. J. A. Sani, and T. A. Salim. 2023. “Content Analysis of Libraries’ Instagram Posts: Cultural Collection, Activities, and Preservation of Cultural Heritage.” Preservation, Digital Technology and Culture 52 (3): 103–11. https://doi.org/10.1515/pdtc-2023-0017.Search in Google Scholar

Radun, D. F., F. C. Sossai, and I. Coelho. 2022. “UNESCO: The Emergence of the Ideals of Peace and World Heritage.” Contexto Internacional 44 (3). https://doi.org/10.1590/s0102-8529.20224403e2020134.Search in Google Scholar

Rietveld, R., W. V. Dolen, M. Mazloom, and M. Worring. 2020. “What You Feel, Is what You like Influence of Message Appeals on Customer Engagement on Instagram.” Journal of Interactive Marketing 49 (1): 20–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intmar.2019.06.003.Search in Google Scholar

Rotman, D., and J. Preece. 2010. “The ‘WeTube’ in YouTube–Creating an Online Community through Video Sharing.” International Journal of Web Based Communities 6 (3): 317. https://doi.org/10.1504/ijwbc.2010.033755.Search in Google Scholar

Royo-Vela, M., and P. Casamassima. 2011. “The Influence of Belonging to Virtual Brand Communities on Consumers’ Affective Commitment, Satisfaction and Word-of-mouth Advertising.” Online Information Review 35 (4): 517–42. https://doi.org/10.1108/14684521111161918.Search in Google Scholar

Saseanu, A. S., S. I. Ghita, I. Albastroiu, and C. A. Stoian. 2020. “Aspects of Digitalization and Related Impact on Green Tourism in European Countries.” Information 11 (11): 507. https://doi.org/10.3390/info11110507.Search in Google Scholar

Sheldon, P. J. 2020. “Designing Tourism Experiences for Inner Transformation.” Annals of Tourism Research 83: 102935. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2020.102935.Search in Google Scholar

Shishmanova, M. V. 2019. “Cultural Heritage, Cultural Tourism, and Creative Economy Basis for Social and Economic Development.” In: Caring and Sharing: The Cultural Heritage Environment as an Agent for Change: 2016 ALECTOR Conference. Istanbul, Turkey: Springer International Publishing, 153–63.10.1007/978-3-319-89468-3_13Search in Google Scholar

Smith, M. K. 2015. Issues in Cultural Tourism Studies. London, UK: Routledge.10.4324/9781315767697Search in Google Scholar

Sonia, P., G. Sravanthi, I. Khan, S. Pahwa, Z. N. Salman, and G. Sethi. 2023. “Sustainable Utilization of Natural Stone Resources: Environmental Impacts and Preservation of Cultural Heritage.” In E3S Web of Conferences, Vol. 430, 01106. Les Ulis, France: EDP Sciences.10.1051/e3sconf/202343001106Search in Google Scholar

Su, M. M., Y. Sun, G. Wall, and Q. Min. 2019. “Agricultural Heritage Conservation, Tourism and Community Livelihood in the Process of Urbanization – Xuanhua Grape Garden, Hebei Province, China.” Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research 25 (3): 205–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2019.1688366.Search in Google Scholar

Sumner, H. 2024. “A Critical Analysis of Conservation Marketing and Campaigning Strategies in the Digital Age: The Case of World Wildlife Fund (WWF).” In Film, Media, and Journalism Best Research Projects 2023–2024. North Wales Coast, UK: Bangor University.Search in Google Scholar

Sutrisno, S. 2023. “Changes in Media Consumption Patterns and Their Implications for People’s Cultural Identity.” Technology and Society Perspectives (TACIT) 1 (1): 18–25. https://doi.org/10.61100/tacit.v1i1.31.Search in Google Scholar

Swensen, G., and L. Nomeikaite. 2019. “Museums as Narrators: Heritage Trails in a Digital Era.” Journal of Heritage Tourism 14 (5–6): 525–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/1743873x.2019.1574803.Search in Google Scholar

Timothy, D. J. 2020. “Journal of Heritage Tourism.” In Encyclopedia of Global Archaeology, 6197–8. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing.10.1007/978-3-030-30018-0_1244Search in Google Scholar

Tsimonis, G., and S. Dimitriadis. 2014. “Brand Strategies in Social Media.” Marketing Intelligence & Planning 32 (3): 328–44. https://doi.org/10.1108/mip-04-2013-0056.Search in Google Scholar

Vlassis, A. 2021. “Global Online Platforms, COVID-19, and Culture: The Global Pandemic, an Accelerator towards Which Direction?” Media, Culture & Society 43 (5): 957–69. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443721994537.Search in Google Scholar

Wang, H., Z. Gao, X. Zhang, J. Du, Y. Xu, and Z. Wang. 2024. “Gamifying Cultural Heritage: Exploring the Potential of Immersive Virtual Exhibitions.” Telematics and Informatics Reports 15: 100150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.teler.2024.100150.Search in Google Scholar

Waterton, E., S. Watson, and H. Silverman. 2016. “An Introduction to Heritage in Action.” In Heritage in Action, 3–16. Cham, Switzerland: Springer.10.1007/978-3-319-42870-3_1Search in Google Scholar

Watson, S., A. J. Barnes, and K. Bunning, eds. 2019. A Museum Studies Approach to Heritage. London, UK: Routledge.10.4324/9781315668505Search in Google Scholar

Yang, F. X., and Y. Wang. 2025. “Rethinking Metaverse Tourism: A Taxonomy and an Agenda for Future Research.” Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research 49 (1): 3–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/10963480231163509.Search in Google Scholar

Ye, D., D. Cho, F. Liu, Y. Xu, Z. Jia, and J. Chen. 2024. “Investigating the Impact of Virtual Tourism on Travel Intention during the Post-COVID-19 Era: Evidence from China.” Universal Access in the Information Society 23 (4): 1507–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10209-022-00952-1.Search in Google Scholar

Yoon, T. K., J. Y. Myeong, Y. Lee, Y. E. Choi, S. Lee, S. Lee, and C. Byun. 2024. “Are You Okay with Overtourism in Forests? Path between Crowding Perception, Satisfaction, and Management Action of Trail Visitors in South Korea.” Forest Policy and Economics 161: 103184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forpol.2024.103184.Search in Google Scholar

Zhang, S., J. Liang, X. Su, Y. Chen, and Q. Wei. 2023. “Research on Global Cultural Heritage Tourism Based on Bibliometric Analysis.” Heritage Science 11 (1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-023-00981-w.Search in Google Scholar

Zhu, Y., S. Chai, J. Chen, and I. Phau. 2024. “How Was Rural Tourism Developed in China? Examining the Impact of China’s Evolving Rural Tourism Policies.” Environment, Development and Sustainability 26 (11): 28945–69. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-023-03850-5.Search in Google Scholar

Zhuang, W., Q. Zeng, Y. Zhang, C. Liu, and W. Fan. 2023. “What Makes User-Generated Content More Helpful on Social Media Platforms? Insights from Creator Interactivity Perspective.” Information Processing & Management 60 (2): 1–19, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ipm.2022.103201.Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Moving into 2025

- Articles

- New Contributions to Iron Gall Ink Inspection Protocols Using Open Source Surface Analysis and Digital Imaging

- Passing Down Local Memories: Generativity and Photo Donations in Preservation Institutions

- Oral History Metadata and AI: A Study from an LGBTQ+ Archival Context

- Exploring Design Aspects of Online Museums: From Cultural Heritage to Art, Science and Fashion

- Can Social Media Pave the Way for the Preservation and Promotion of Heritage Sites?

- Exploring the Potential of Mobile Phone Applications in the Transmission of Intangible Cultural Heritage Among the Younger Generation

- The Application of Interaction Design in Cultural Heritage Tourism: A Systematic Literature Review

- List of Reviewers

- PDT&C Peer-Reviewers in 2023–2024

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Moving into 2025

- Articles

- New Contributions to Iron Gall Ink Inspection Protocols Using Open Source Surface Analysis and Digital Imaging

- Passing Down Local Memories: Generativity and Photo Donations in Preservation Institutions

- Oral History Metadata and AI: A Study from an LGBTQ+ Archival Context

- Exploring Design Aspects of Online Museums: From Cultural Heritage to Art, Science and Fashion

- Can Social Media Pave the Way for the Preservation and Promotion of Heritage Sites?

- Exploring the Potential of Mobile Phone Applications in the Transmission of Intangible Cultural Heritage Among the Younger Generation

- The Application of Interaction Design in Cultural Heritage Tourism: A Systematic Literature Review

- List of Reviewers

- PDT&C Peer-Reviewers in 2023–2024