Abstract

In the digital media era, the preservation of minority languages and cultures faces profound challenges. This article focuses on the Gyalrong Tibetan language (GTL) as a representative case within the broader context of linguistic diversity endangerment. The emergence of digital technology as a supplementary tool to preserve endangered languages provides opportunities and challenges in language conservation. Adopting a qualitative research approach and thematic analysis, collecting data from previous studies, fieldwork, and interviews, this study considers the intersection of digital technology and GTL preservation. It examines 1) the opportunities, 2) the challenges and concerns of integrating digital technology and minority languages and 3) the evolving dynamics of language proficiency influenced by educational systems among younger generations. Moreover, these considerations are placed within the framework of media ecology and language shifts, exploring how communication technologies shape GTL and its cultural context. This research contributes empirical insights to the discourse on minority language revitalisation and offers a strategic view for further research into language preservation in a digitised world.

1 Introduction

Phyak (2021) and Robinson et al. (2020) highlighted that, in an era marked by rapid globalisation and technological advancement, minority communities worldwide face challenges and opportunities regarding their linguistic and cultural diversity. Furthermore, Lewis and Simons (2016) illustrated that minority languages represent more than 60 % of the world’s languages, however, unfortunately, one-third of the former are in a process of disappearing. For example, urbanisation, migration and the dominance of Mandarin Chinese in China have resulted in a decrease in the number of people using minority languages, such as Miao and Yi, on a daily basis (Qu 2010, 2014; Tashi and Drudrup 2011).

In China, minority identity refers to the recognition and representation of ethnic groups that are distinct from the majority Han Chinese population (Qu 1984, 1990, 2010). These ethnic groups have their own distinct languages, cultures, traditions and histories. The Gyalrong Tibetan language (GTL) is one of the most representative Tibetan dialects (Qu 1984, 2010) playing a dominant role in understanding ancient Tibetan literature and Han language (Qu 1984; Que 1995; Shi 2014; Tashi and Drudrup 2011). However, most GTL users are middle-aged or older; youth use GTL far less than the former groups in terms of the scope, frequency and familiarity of use (Qu 2010). Therefore, the dissemination and development of Gyalrong Tibetan is facing a great challenge.

Using digital technology to help preserve minority languages has gained significant attention in recent years due to its potential for addressing challenges related to language endangerment, cultural preservation and education (Fan 2018; Jia 2023; Qu 2010; Zhu 2021). Digital technology offers various options for promoting and safeguarding GTL, such as via digital language documents and digital archiving of cultural artifacts. However, the development of digital technology allows GTL to have more connection with other languages, and substantially leads to language shifts (Fishman 2001). The intersection of digital technologies and the preservation of minority languages presents not only opportunities but also challenges, and it is through the lenses of media ecology that we can gain insight into these dynamics (Cassels 2019; McLuhan 1964).

This study delves into the use of digital technology to protect the GTL in different ways. A qualitative research method is used, including analysis of previous studies, fieldwork and interviews, to underscore the opportunities, barriers, concerns and education regarding using digital technology to preserve the GTL. At the same time, this study not only provides empirical insights but also contributes to future revitalisation of minority languages and cultures.

This study begins by delineating the current GTL background to highlight its current problems and differences compared to other Tibetan languages and Chinese Mandarin. The next section introduces the application of digital technology in the learning of GTL, presenting its challenges and reflections on the use of digital technology. Finally, the study concludes by considering GTL education, showing how the use of digital technologies in the Gyalrong Tibetan community (GTC) can provide a potential development model for traditional languages and cultures.

2 Literature Review

Language is one of the important factors in national psychological identity and an important sign of national identity (Qu 2014). However, in the process of modernisation in contemporary China, minority languages, which contain a large amount of local knowledge (e.g., myths, legends, folk songs, minority life, folk memories), are disappearing rapidly (Fan 2018; Tashi and Drudrup 2011). This situation is evident among the Gyalrong Tibetan people in the western Sichuan province, who speak GTL as their native language. GTL is important for understanding ancient Tibetan literature because GTL includes many ancient Tibetan vocabularies (Qu 2010).

The development of modern communication technologies, such as information technology and the Internet, is a typical characteristic of the information age. Technology offers unlimited opportunities for language preservation (Jia 2023) and improving quality of life (Lakhan and Laxman 2018). Regarding minority language preservation, while there has been much research on the history of minority words and literature protection (Fan 2018; Jia 2023), few researchers have conducted empirical studies to investigate the dissemination and usage of minority language in the digital media era.

2.1 The Diversity of Tibetan Dialects in China

There are three major Tibetan regions in China: U-Tsang, Amdo and Kham (Duoerji 2015; Zhou 2010). The Tibetan people are primarily divided into U-Tsang, Amdo, Kham and special Tibetan branches, the latter of which include Kongpo, Gyalrong, Minyag, Baima, Hwari, Zhuocang, Sherpa and others (Roche and Suzuki 2018; Suzuki 2016; Zhou 2010). The classification of Tibetans is highly consistent with the classification of Tibetan regions.

There were more than 1.2 million Tibetans in western Sichuan by the end of 2006 (Wang 2006). These Tibetans are primarily distributed among the Garze Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture (with c. 732,000 people); Aba Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture (c. 480,700 people); Liangshan Yi Autonomous Prefecture; Baoping, Shimian, Hanyuan, and other counties in the Ya’an area; and in Pingwu and Nanping counties in the Mianyang area (Qu 2010; Suzuki 2016; Wang 2006).

In academia, the Gyalrong Tibetans are generally considered a branch of the Tibetan ethnic group, with a population of c. 370,000 (Qu 1984, Que 1995; Shi 2014) predominantly distributed among Danba County and Kangding County of the Garze Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, the Da Jin River and Xiao Jin River basin west of the Qionglai Mountains, Li and Wenchuan Counties east of the Qionglai Mountains along the Dadu River, and in Baoxing County, Tianquan County, Kangding City and Daofu County southeast of the Jiajin Mountains. In Danba County (Figure 1), approximately 60 % of the population is Gyalrong Tibetan, 30 % Han, and 3 % Qiang, with the remaining 7 % composed of Mongolian, Hui, Dong, Miao, Manchu, Zhuang, Chaoxian and other ethnic minorities.

The map of Danba County.

There are many dialects of the Tibetan language, which are primarily divided into U-Tsang, Amdo and Kham (Qu 1984, 2010). These three dialects are further subdivided, as follows.

The U-Tsang dialect includes the Qianzang dialect, which is primarily spoken in Lhasa and Shannan, the Hoin Tibetan dialect in Shigatse Prefecture, the Ali Tibetan dialect in Ali Prefecture, the Sherpa Tibetan dialect in Zhangmu Port of Nyalam County, the Basong Tibetan dialect in Cuogao Township and Xueka Township of Gongbujiangda County (Qu 2014; Que 1995).

The Kham Dialect includes the eastern native dialect in Dege County, Kang Ding City, Ya Jiang County, Changdu City and other regions; the southern dialect in Diqing Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture and Muli Tibetan Autonomous County; the western dialect in Gaize, Bange, Nierong, Shenzha and other counties; Zhuoni dialect in Zhuoni and Diebu Counties; and Zhouqu dialect in Zhouqu county (Qu 2014; Que 1995; Shi 2014; Suzuki 2016).

The Amdo dialect includes pastoral dialects in various Tibetan autonomous prefectures in Qinghai Province and parts of Aba Tibetan and Qiang Autonomous Prefecture in Sichuan Province; agricultural native languages in Hualong Hui Autonomous County, Xunhua Salar Autonomous County, and Ledu District of Haidong City, among others; and semi-agricultural and semi-pastoral languages of Tongren County and Xiahe County (Qu 1984, 1990).

The languages spoken in Tibetan areas in western Sichuan are diverse, including different Tibetan dialects, Chinese and other minority languages (Duoerji 2015; Qu 2010). In western Sichuan, Chinese is also divided into Mandarin and Sichuanese, which primarily reflect differences in speech. Most of the early Tibetan residents in western Sichuan were accustomed to speaking the Tibetan language, the most representative of which was the GTL (Tashi and Drudrup 2011). In addition, Tibetan dialects in Sichuan province include the Kang dialect, the Jia dialect, the Amdo language and the Ergonese language (Qu 1984, 1990, 2010; Suzuki 2016).

However, with development over time and according to the needs of society, the Jiarong Tibetan language is gradually disappearing, being replaced by the current Chinese language. Increasingly many Tibetan residents can understand but not speak Tibetan (Duoerji 2015; Fan 2018). Moreover, in western Sichuan, because there are many dialects of Tibetan languages that cannot be unified and centralised, the retention and transmission of each language is often limited to oral transmission of family life and daily communication of older persons.

2.2 Digital Technology and Gyalrong Tibetan Community

In recent decades, digital technology has become a typical feature of modern societies, influencing various communities worldwide (Sianturi, Lee, and Cumming 2023). The GTC is known for its unique language, culture and traditions (Qu 2010). With the development of Internet and infrastructure construction, Danba County, where the GTC is located, has become a famous tourist destination, illustrating how the GTC is increasingly connected to other communities and Internet connectivity and the use of mobile devices have expanded, facilitating access to information, communication and online services. Furthermore, digital technology has facilitated communication between geographically dispersed Gyalrong Tibetans, allowing them to maintain cultural ties and solidarity (Zhu 2021).

Digital technology has been adopted into conservation of both intangible and tangible culture heritage, such as customs, traditions, language, archaeological sites, artifacts and so forth (UNESCO 2003). To preserve intangible cultural heritage, initiatives such as the digitisation of traditional paintings, oral traditions and traditional costumes have been undertaken. Virtual platforms have also emerged, allowing all community members to share stories, songs and rituals, thereby increasing cultural awareness and understanding (Ovide and García-peñalvo 2016; Sianturi, Lee, and Cumming 2023). At the same time, social media has become a popular tool to allow the online dissemination of digital cultural heritage in comprehensive and attractive manner (Manžuch 2017; Meighan 2022).

In addition, for most Gyalrong Tibetans, social media platforms are significant channels through which to express their identity and disseminate minority culture and experiences (Casumbal-Salazar 2017; Meighan 2022). Meanwhile, Gyalrong people can connect with other communities and promote cross-cultural exchanges through digital media, such as short films, documentaries and online art galleries (Lakhan and Laxman 2018). Digital storytelling has allowed the GTC to share their history, struggles and aspirations with the world, promoting cultural appreciation and understanding (Galla 2016; Mager et al. 2018).

However, the GTC faces challenges in terms of digital confusion, due to disparities in Internet infrastructure (Marcu et al. 2022) associated with living in remote areas, along borders, or in economically underdeveloped areas (Li et al. 2021; Jia 2023). For instance, some community members, especially older persons and remote villagers, may have limited access to digital resources, which affects their perception of digital technologies (Li and Woolrych 2021).

Digital technology also has influenced the traditional economy of the GTC. Although digital technology has opened new possibilities for cultural preservation, economic growth and social connections, challenges related to digital inclusion and cultural representation persist (Fan 2018; Zhu 2021). For instance, e-commerce platforms and mobile payment systems have facilitated trade and opened new economic opportunities for local artisans and businesses. However, possible homogenisation of traditional handicrafts and cultural products for the digital market remains a concern. Fan (2018) and Zhao (2022) indicated that it is essential for stakeholders, including governments, NGOs, and community leaders, to address these challenges to ensure that the GTC can fully exploit the potential of digital technologies while preserving its unique heritage and identity.

2.3 Digital Technology and the Gyalrong Tibetan Language

Several studies have emphasised the significance of digital technology in documenting and archiving minority languages. For instance, Eisenlohr (2004) reviewed studies that addressed using new technologies to revitalise lesser-used languages. Elsewhere, Casumbal-Salazar (2017) also conducted similar research regarding digital technologies and indigenous languages. Hence, digital technology has emerged as a significant tool for the preservation and revitalisation of minority languages and cultures. Of the three major dialects, Kangba has particular significance for improvement of the cultural community, promotion of cultural prosperity, and promotion of ethnic history research (Qu 1984; Zhao 2022).

The GTL, which is used by c. 370,000 people, has a complicated linguistic and historical cultural background (Qu 2014). GTL is an important branch of the Kham dialect, with its use primarily concentrated in areas such as Maerkang City, Jinchuan County, Xiaojin County, Wenchuan County in the Aba Tibetan and Qiang Autonomous Prefecture of Sichuan Province, and Danba County and Daofu County in the Garze Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture (Qu 1984, 2010).

GTL is the only Tibetan branch language that retains relatively complete ancient characteristics and hence is valuable when studying the history of Sino-Tibetan languages (Qu 2010, 2014). For instance, the consonant-vowel system of GTL is complicated but regular, and the GTL grammatical system includes ancient prepositional structures and personal and subordinate categories (Qu 2014). Influenced by the geographical environment, GTL has divided into four dialects that are not mutually intelligible and have local characteristics (Qu 1990, 2014), and includes at least seven different dialects in total (Tashi and Drudrup 2011).

Linguistic diversity is an important part of human civilisation, and the protection of national languages is a necessary part of the protection of cultural diversity and the plurality of civilisations (Qu 2010; Zhao 2022). However, many minority languages and cultures in China are gradually disappearing, with the GTL and culture no exception. One of the factors underlying this disappearance is that ethnic minority areas have basically formed a bilingual system of minority language and Chinese, due to economic development, population flow, frequent exchanges, the need for communication (Qu 2010) and the promotion of the common language (Tashi and Drudrup 2011).

Qu (2010) noted that one characteristic of an endangered minority language is that it is only used in a small area and mixed with other languages (Tashi and Drudrup 2011). Similar to the characteristics of scattered, small, and mixed distribution of ethnic minorities in other regions of China, Gyalrong Tibetan people primarily live in Danba county, a remote and small county in western Sichuan (Qu 2014). Many other minority groups live in Danba county, such as Han, Yi and Qiang. Therefore, conducting language research with Gyalrong Tibetans in Danba County can serve as a typical case that applies to other areas of the country.

Various factors might lead to language changes, such as socio-political, economic, cultural development, the number of people who speak the language, the scope of communication, the nature of language, and the scope of communication functions (Qu 2010, 2014; Tashi and Drudrup 2011). As the number of people using and understanding the GTL decreases, GTL and its associated heritage will inevitably disappear. Moreover, because the younger generation of Gyalrong Tibetan people have limited understanding of Gyalrong Tibetan heritage, they try to avoid using the GTL in their daily life. Therefore, it is critical to research the protection and dissemination of Gyalrong Tibetan minority languages.

Digital technology offers opportunities for cultural preservation and representation (Junker 2018; Lantaya et al. 2021). Researchers have explored the use of digital platforms to showcase Gyalrong Tibetan cultural heritage, including traditional stories, music, and rituals. By presenting the cultural aspects of the Gyalrong Tibetan dialect online, digital technology contributes to the promotion and awareness of the significance of the language within its cultural context (Qu 2014; Tashi and Drudrup 2011). In addition, digital recording devices, linguistic databases, and online archives have enabled researchers and community members to capture and preserve spoken language, cultural practices, and traditional knowledge associated with the dialect (Brown and Nicholas 2012).

Digital technology ensures the conservation of linguistic resources, making them accessible for future research and language revitalisation initiatives. To protect GTL, researchers have considered education, ideology and culture. However, there exist difficulties with GTL research, due to a lack of learning and reference materials (Tashi and Drudrup 2011). A lag exists in the digitisation of ethnic minority cultures, and the popularisation and dissemination of concepts and technologies for the creation, preservation and utilisation of digital resources is slow (Fan 2018; Zhao 2022).

In recent decades, linguistics researchers and local cultural workers have expended considerable effort to collect and retain a large digital corpus, including of minority languages and oral literature. Nevertheless, the actual application of digital sources is inadequate, due to dated formats and lack of dissemination (Fan 2018). Meanwhile, previous research has focused more on the history, pronunciation and distribution of the GTL (Qu 1984, 1990, 2010), and the theoretical preservation of GTL material (Duoerji 2015; Tashi and Drudrup 2011). There is insufficient prior empirical research, especially in the context of current society, which is characterised by rapid development of digital technology; in this context, research cannot remain at a theoretical level (Fan 2018; Zhao 2022; Qu 2014; Zhu 2021). Further research needs to better adopt the collected literature and materials into daily life.

This study addressed the following three research questions: 1) How can digital technology support GTL revitalisation and cultural reclamation? 2) What are the challenges and opportunities associated with incorporating digital technology in the preservation of the Gyalrong Tibetan dialect? 3) What are the younger generation’s perspectives on using digital technology to support GTL dissemination?

3 Theoretical Framework

This study contextualised media ecology and language shift theory and digital humanities as theoretical perspectives to instruct data explanation and analysis. The media ecology framework examines how communication technologies influence culture and language practices (McLuhan 1964). In the digital era, increased exposure to dominant languages through media platforms can lead to language shifts and decreased use of minority languages (Cassels 2019). Investigating the influence of digital media on GTL use can reveal language shift dynamics and inform targeted conservation strategies in the digital media era.

Language shift refers to a process in which a community gradually transitions from using one language as their primary means of communication to using another language (Fishman 2001). Hill (2002) and Zuckermann (2020) illustrated that the language shift phenomenon is usually caused by discrimination, oppression, colonisation and cultural genocide, however, as digital media exposure increases, language shift dynamics occur (Androutsopoulos 2011). Studies have investigated how digital media influence language use among Gyalrong Tibetan speakers. Understanding the influence of digital technology on language shifts plays an essential role in the process of designing effective language conservation strategies to reduce the factors that drive potential language loss.

The digital humanities (DH) framework underscores the intersection of digital technologies and cultural heritage (Spiro 2012). For instance, this can refer to using tools, methodologies, and platforms in the exploration and preservation of language. DH has been employed by language preservation projects worldwide, including archiving and language revitalisation programs (Terras, Nyhan and Vanhoutte 2013). This illustrates how DH can provide valuable insights into the integration of digital technology to preserve GTL resources, traditional costumes, and cultural heritage.

4 Methodology

This study analyses the preservation of the GTL in Western Sichuan Province, focusing on the motivation, education, challenges, and opportunities of using digital technologies in GTL preservation. This research consisted of a qualitative case study design and thematic analysis, which facilitated in-depth understanding of the current issues and potential strategies underlying the use of digital language preservation in the GTC.

A qualitative research approach is suitable for understanding the relationships among digital technology, community engagement and language revitalisation in a localised field (Greene, Kreider, and Mayer 2005; Taguchi 2018). At the same time, qualitative research can help to describe the details of participants’ feelings, suggestions, and personal experiences, and convey the meaning of participants’ reactions (Denzin and Lincoln 1998; Richardson 2012). Therefore, readers can empathize with participants and easily understand the complex issues.

Fieldwork, semi-structured interviews (Dearnley 2005), and archival research were employed to collect data from language experts and relevant residents in Dan Ba county, Sichuan Province, China. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with Gyalrong Tibetan linguists, educators, government employees, primary students, local merchants, and local Gyalrong Tibetan residents, with a total of 67 respondents. Interviewee demographics are provided in Table 1. These interviews explored their experiences (Adams 2015), perceptions, and practices (Dearnley 2005) related to the use of digital technology in language preservation in terms of five different dimensions: linguistic and cultural factors, social factors, economic factors, environmental factors, and technological factors (Galla 2016). Open-ended questions allowed participants to share their insights and provide qualitative data regarding their interactions with digital tools, challenges faced and successes achieved.

Demographic profile of interviewees.

| General information | Interviewee | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 27 | 67 |

| Female | 40 | ||

| Others | 0 | ||

| Age | Under 18 | 30 | 67 |

| 19–45 | 19 | ||

| 46–65 | 9 | ||

| Over 66 | 9 | ||

| Identity | Linguists | 8 | 67 |

| Government employees | 5 | ||

| Primary students | 30 | ||

| Local merchants | 9 | ||

| Local residents | 9 | ||

| Educators | 6 | ||

The survey was limited to Gyalrong Tibetan residents living in Danba County. These data represented a random sample that should be representative of local minority communities (Desalegn et al. 2019). Moreover, to better understand and learn the history of the GTC and the distribution of the GTL dialect, secondary data were collected from previous literature and official documents.

Digital language resources, websites, social media platforms, and online communities relevant to GTL preservation were analysed. This analysis provided insights into the types of resources available, their content and their impact on language preservation (Bowen 2009; Rabianski 2003). It will help identify trends, themes, and innovative practices in the utilisation of digital technology for language revitalisation (Rabianski 2003).

Face-to-face interviews in both Chinese Mandarin and Sichuanese were conducted in Dan Ba county from June to August 2022. Interviewees were asked general questions about GTL preservation in Dan Ba county within three main categories: 1) motivations of learners, 2) positive influences and concerns in using digital technology to protect the GTL, and 3) language education. Each interview lasted between 20 and 30 min and was recorded by a digital camera. This research followed the six-step thematic analysis procedures proposed by Braun and Clarke (2006) to analyse interview transcripts.

Ethical considerations are a crucial part of the research process to ensure the protection of participants’ rights and confidentiality (Arifin 2018). All participants received an informational letter before participating in the interview, confirming they fully understood the purpose of the study, the voluntary nature of their participation, the confidentiality of their responses, and their rights. Further, participants had the opportunity to ask questions, provided voluntary consent to participate in the research and could withdraw at any time, without penalty. To ensure cultural sensitivity and community values (Graham et al. 2011; Ross, Iguchi and Panicker 2018), efforts were made to engage in a collaborative and participatory research approach, involving the GTC and relevant stakeholders in the research design and implementation.

Participant anonymity was maintained by assigning pseudonyms or using participant codes during data analysis and reporting. Additionally, the research adhered to ethical guidelines regarding the responsible handling and storage of data, ensuring its secure and confidential storage. This included digital data encryption, password protection of the record files, and secure storage of physical handwriting interview documents. Data access was restricted to authorised personnel. Any potential biases or conflicts of interest were acknowledged and minimised throughout the research process, and the study was conducted with the utmost respect for the well-being and cultural rights of the Tibetan community.

5 Results

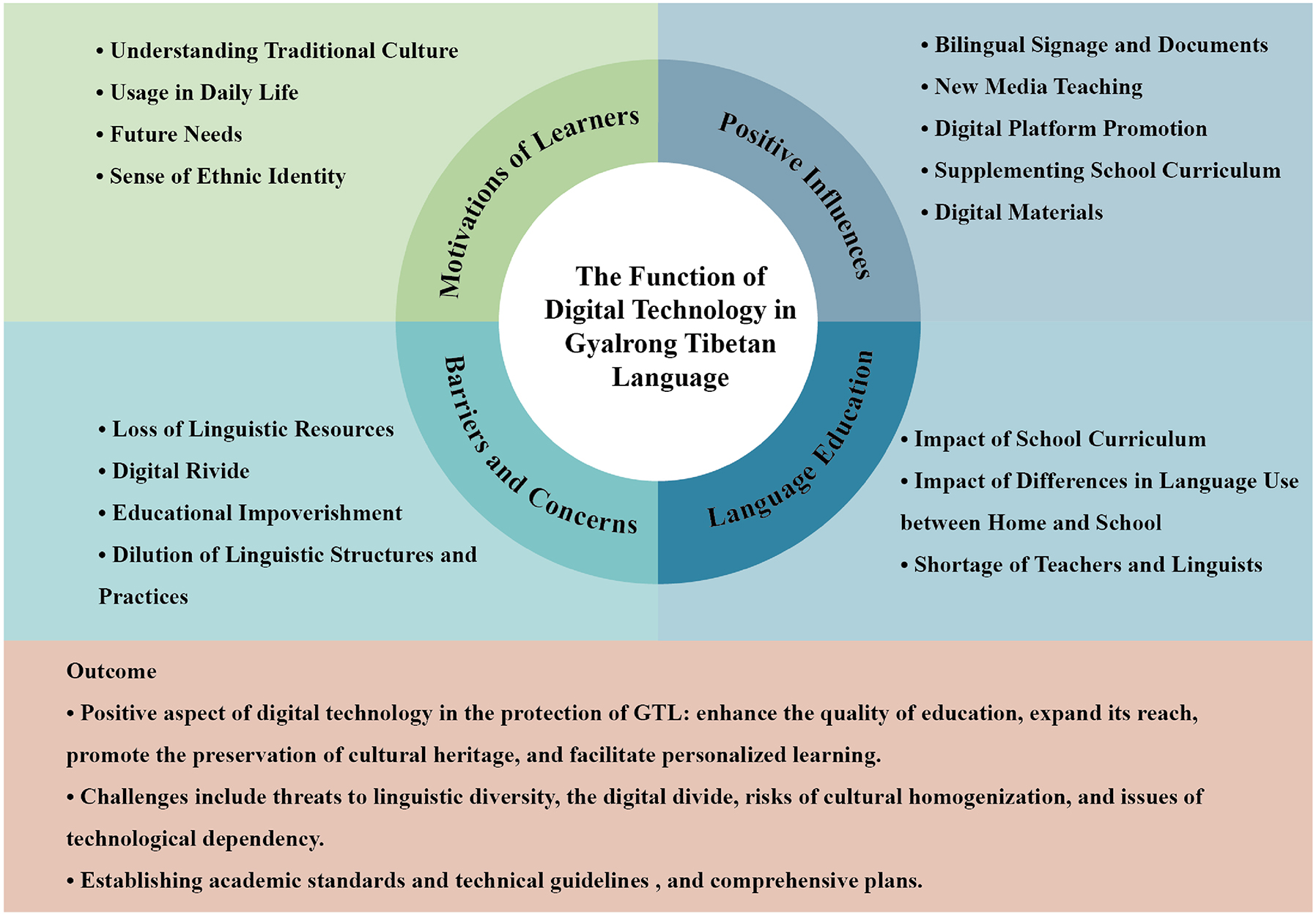

This analysis examined the function and role of digital technology in minority language preservation, drawing on open-ended questions in the interviews and a literature search. Questionnaires and interviews were organised into technology-related topics which included 1) motivations of learners, 2) positive influences, 3) barriers and concerns in using digital technology to protect the GTL, and 4) language education (see Figure 2).

The overarching research results from the current investigation.

5.1 Motivations of Learners

One difference between learning an endangered language and learning the primary spoken language is that, in most cases, endangered languages can only be used in a small community or area or in a household (Qu 2010). Languages become endangered through language shifts caused by conquest, oppressive policies (Hinton 2011), or economic needs (Qu 2010, 2014). The rate with which minority languages are protected is far slower than the speed of language decline and consequently, language researchers must intensify their efforts to comprehensively document and study languages before they disappear.

Among the 67 Tibetan residents interviewed in this research, based on analysis of their intrinsic and extrinsic motivations, more than 60 % mentioned that although learning and using GTL helps them to understand and promote the traditional culture of their own people, they also use the language in their daily lives. However, as the frequency of using the language in education and workplace is low, people’s enthusiasm and initiative to learn the GTL have also decreased.

The motivations of learners encompass a blend of cultural pride, identity connection, and community engagement (Wiltshire, Bird, and Hardwick 2022). Participant A shared insight into the motivations of students for learning the GTL illustrating that the enthusiasm and involvement of students in Tibetan language classes indicated a genuine interest in learning their native language, based on their desire to connect with their cultural roots, communicate with older community members, and actively participate in the local community.

However, extrinsic motivations also play an essential role in GTL learning. Based on the interview results, one-third of the respondents believed that motivation to learn the GTL is based on the need for future study, work, or their own feelings of nationality (Hinton 2011). With the growth of tourism, GTL performance has become one of the local attractions, allowing GTL speakers to enhance their income levels by participating in language activities. In the context of limited resources, the interactivity and appeal of digital technology provide learners with opportunities to engage in their language learning journey. Concurrently, local government initiatives and educational institutions align with these motivations, fostering an environment that encourages and propels individual learning of GTL.

The motivations of learners are influenced by factors such as education, cultural preservation efforts (Wiltshire, Bird, and Hardwick 2022), and challenges and opportunities within interactive learning experiences (Galla 2018). Therefore, if learners can be correctly guided and actively encouraged, they can promote the transformation from thought to action, and actively learn the GTL and their traditional culture. Many individuals are curious and likely to be interested, which can actively enhance their sense of national identity, and integrate the establishment of a strong sense of social responsibility with their own development.

5.2 Positive Functions of Technology in Gyalrong Tibetan Language Dissemination

Cultural preservation is essential to safeguard the GTL and its cultural heritage (Casumbal-Salazar 2017). The Danba County government and local organisations have made significant efforts to promote the preservation of GTC; Interviewee B who works for the government mentioned that, “the government has been proactive in using digital platforms to raise awareness about the GTL and culture”.

The use of digital technology allows for the creation and dissemination of bilingual signage and documentation (Galla 2016; Meighan 2022; Sianturi, Lee, and Cumming 2023). Government units and businesses are employing technology to ensure that information is presented in both Tibetan and Chinese. Therefore, digital technology enables learners and speakers to notice and understand that language is an essential part of their minority culture (Cassels 2019; Galla 2016) which enhances visibility and accessibility, reinforcing the presence and importance of the GTL in public spaces.

At the same time, digital technology can be used to provide reliable professional guidance and a teaching basis for the further development of Gyalrong Tibetan and to implement cultural rescue for minority languages. Participant C mentioned that:

The better and more influential thing is the Wuming Buddhist Institute in Serta, which will tell about Tibetan culture in the process of explaining scriptures by living Buddhas and khenpos through new media and offline teaching, and call on everyone to understand the history and culture of the Tibetan language and learn the Tibetan mother tongue.

The interviewee highlighted cultural events like the Gyalrong Cultural Festival that serve as platforms for language and culture promotion, with digital technology playing a pivotal role in the events. Digital platforms such as social media, official websites, and mobile apps are utilised to advertise and coordinate these events (Meighan 2022). This broader reach enhances participation and engagement (Galla 2016), attracting individuals who might otherwise have limited exposure to the GTL (Cassels 2019; Mager 2018).

The integration of digital technology into cultural preservation has made a significant contribution to the spread of the GTL (Galla 2018). The use of such technology has enhanced accessibility, visibility, and engagement with digital event promotion and creative content sharing technologies (Mager et al. 2018). These positive features illustrate how technology can play a key role in maintaining and promoting minority languages, such as Gyalrong Tibetan.

5.3 Barriers and Concerns in Using Digital Technology

Minority languages and intangible cultural heritage could greatly benefit from digital technologies (Cassels 2019; Galla 2016; Mager et al. 2018; Sianturi, Lee and Cumming 2023). However, there remain challenges and complexities in the context of preserving minority languages through digital technology. During the interviews, barriers and concerns were noted by various stakeholders with respect to GTL preservation.

First, the interviewees expressed concerns about maintaining the authenticity and integrity of the GTL and culture while utilising digital technology. Some interviewees worried that digital media might inadvertently dilute or change the traditional linguistic structures and practices. Of the interviewees, 30 % highlighted that although the swiftness of new media dissemination and the broad reach of its audience facilitate the spread of culture, they may also lead to the distortion and misunderstanding of cultural content, meaning learners often cannot distinguish the authenticity and integrity of GTL dialect and writing. Furthermore, overuse of digital technology might change minority culture (Cassels 2019), modify the history of the minority community (Salazar 2007), and lead to language shifts (Hill 2002; Wiltshire, Bird, and Hardwick 2022).

Digital technology brings new opportunities to expose minority culture and peoples to the broader world (Cassels 2019; Mager 2018). Therefore, there exists a delicate balance between new technologies and traditional practice. Participant E said that, “we must carefully tread the line between using technology and preserving our priceless traditions.” Indeed, 70 % of the participants mentioned this aspect. Additionally, cultural boundaries make it difficult for members of out-groups to access authentic language use. Digitally presenting the true meaning and pronunciation of GTL is a key principle, while also considering cultural boundaries to ensure that the audience can easily understand the relevant culture.

Second, language resources are primarily composed of ethnic languages and regional dialects, but the production and protection of language heritage though digital means is primarily directed toward areas of ethnic and rural dialect (Fan 2018). However, many minority language resources are stored in a diffuse manner, and due to a lack of protection experience and professional technology, some written and sound resources have been lost (Tashi and Drudrup 2011; Zhao 2022). Furthermore, problems addressing the cost of new technologies are exacerbated given lack of infrastructure, geographic isolation (Galla 2018; Sianturi, Lee, and Cumming 2023) residents with low income (Sianturi, Lee, and Cumming 2023), and a higher proportion of older residents (Giglitto 2019). In the digital age, certain dialects may be marginalised or even erased due to insufficient support and resources, posing a challenge to language preservation.

Third, the digitalisation process has led to a diminishing wealth of native language education and minority and local languages. This digital divide poses significant challenges to the sustainable development involving minority languages. The digitisation process lags in these areas, and the popularisation and dissemination of concepts and technologies for the creation, preservation and utilisation of digital resources is slow (Fan 2018; Galla 2018). Participants pointed out that not all community members have access to language preservation efforts through digital technology, potentially leaving certain segments of the population behind. Retired interviewee D stated that, “not everyone has smartphones or computers in Danba county. For digital preservation of GTL, we need to consider those who might not benefit from digital initiatives”.

Furthermore, exploring barriers and concerns requires a thoughtful and culturally sensitive approach to the application of digital technology in preserving indigenous languages (Fan 2018; Zhao 2022; Zhu 2021). With such an approach, researchers are able to navigate this complex field and develop strategies that truly respect and protect GTL. To address these challenges, it is essential to formulate and implement strategies that integrate GLC into the digital preservation process. This involves constructing digital libraries tailored for the creation and distribution of locally-relevant information collections for minority languages, promoting participatory design of software and reducing language biases through collaboration with local communities.

5.4 Gyalrong Tibetan Language Education

With the revision of policy, problems related to Tibetan teachers in Danba County have gradually emerged. Over 74 % respondents mentioned that an impact of the school curriculum on Tibetan language proficiency is evident. Teenagers learn the Tibetan dialect with their parents from an early age, however, they use Mandarin in daily communication with their classmates and teachers in school which results in a serious deficit in the inheritance of the GTL.

Participant F, who was dedicated to language dissemination, also mentioned the reason why time spent teaching the traditional language decreased.

Parents think that it is not necessary for their children to know how to write Tibetan and speak Tibetan, as long as they can understand the Tibetan dialect of the family and have daily conversations at home. This is because they prefer to communicate with others in Mandarin or Sichuanese outside of the home.

Further, the research data show that teachers in Danba County pay limited attention to cultural protection and dissemination, as well as to resource development and innovation regarding school-based teaching materials for Gyalrong Tibetan. All of the educators interviewed pointed out that educational institutions lack sufficient GTL teachers or linguists to instruct students and other learners and therefore, the collection and selection of Tibetan intonation in Gyalrong is a major problem (Jia 2023; Qu 2014; Zhu 2021) in the preparation of textbooks. Moreover, Tibetan handwriting is more difficult than Chinese handwriting (Li and Nyima 2010). As current students receive Sichuanese and Mandarin, many students learn Tibetan as a second language.

Digital technology not only brings benefits and challenges to language preservation, but also contributes to indigenous language education (Galla 2016; Hafner, Chik, and Jones 2015). Language learning apps, online resources, and digital platforms can supplement school curricula and provide opportunities for students to engage with the GTL outside the classroom. Furthermore, digitally archived materials, such as audio and video recordings, can store information regarding the minority culture and social phenomena in detail, in a form that is easily presented to others (Galla 2018; Zhu 2021). However, the digital divide between different regions remains a challenge. Students in remote areas may lack access to necessary equipment and internet connectivity, exacerbating the unequal distribution of educational resources and impacting the preservation and transmission of minority languages.

Cultural content within digital language resources can foster a deeper connection to the cultural significance of language. New media and social networking platforms have provided new channels for the dissemination of minority cultures and languages; through these platforms, the languages and cultures of GTC can be more widely disseminated and showcased, thereby enhancing the sense of identity among community members with their own languages and cultures. Therefore, regarding protection of GTL, schools should consider integrating digital resources that offer interactive and engaging ways to learn Tibetan language.

Furthermore, interactive digital tools could be designed to enhance language learning experiences, making the process more appealing and effective for younger generations. For instance, by leveraging big data and artificial intelligence technologies, personalised learning plans could be tailored to students’ learning habits and abilities. Additionally, a short animation film of Tibetan culture could be developed to express the traditional national culture in a vivid and interesting way. This would not only enhance learning efficiency but also ensure that each student receives education resources suited to their needs, thereby better protecting and preserving minority languages. However, excessive reliance on digital technology may lead to students and teachers becoming overly dependent on technical tools, overlooking traditional teaching methods and practical activities. This could potentially undermine students’ actual proficiency in using their own language and culture, thereby affecting the natural transmission of the language.

Therefore, integrating digital technology into educational strategies for the preservation of minority languages has numerous potential benefits, including enhancing educational quality, expanding educational coverage, promoting cultural heritage and facilitating personalised learning. However, it also faces various challenges, such as threats to linguistic diversity, the digital divide, risks of cultural homogenisation, and issues of technological dependency. Additionally, establishing academic standards and technical guidelines for the protection of digital heritage in minority languages is crucial, along with developing comprehensive plans to build digital resources in these languages. Such resources include digital libraries, online courses and resources, e-learning apps, digital archives and open education resources.

6 Conclusions

This study gathered insights from previous studies, fieldwork, and interviews regarding how digital technology could support further research into minority language preservation. This study provides empirical evidence to support language protection research, and identifies further opportunities for and barriers to participation in minority languages using digital technologies.

Digital technology presents a viable solution for sustaining and revitalising the GTL among younger generations who primarily receive their education in modern schools. The Internet and digital and mobile technologies have changed how knowledge is accessed, shared, and engaged, offering communities hope for language preservation (Lakhan and Laxman 2018; Sianturi, Lee, and Cumming 2023). Integrating digital tools thoughtfully into educational strategies can aid in mitigating the language proficiency gap and contribute to language preservation efforts.

However, the process of language preservation has challenges. The concerns illustrated by interviewees reflect that collecting and organising accurate GTL materials from remote regions is a priority in language protection. Additionally, it is important to ensure linguistic authenticity and cultural integrity when using digital technology in language revitalisation (Giglitto et al. 2019; Jia 2023; Qu 2014). Moreover, there is the issue of accessibility of digital documents, highlighting the need to address the balanced development of digital technologies to ensure that they do not inadvertently exclude certain segments of the population.

Furthermore, the evolving role of technology presents itself as a supplementary force for minority language education. Digital technologies allow younger generations to obtain various materials for learning languages beyond the classroom. GTL videos and innovative video formats that attract learners’ attention can contribute to a more holistic understanding of the GTL, however, these efforts need to be executed with care to maintain a connection with traditional practices and values.

In conclusion, the function of digital technology in GTL preservation is not only an evolving solution but also a significant challenge. As technology continues to influence language shifts, cooperation between innovation and tradition is essential to preserve the linguistic and cultural heritage of the GTC. Therefore, in advancing the protection process, it is essential to comprehensively consider these factors and formulate scientifically sound and reasonable strategies to maximise the positive role of digital technology in the protection of minority languages, while minimising its negative impacts.

Appropriate use of digital technologies could simultaneously increase cultural pride and develop a new way to conduct education and language revitalisation. This could include combining GTL instruction with cultural education, emphasising the cultural value and practical application of the language. Besides, more diverse and interactive learning resources for GTL could be generated by developing and utilising digital tools and platforms to incorporate GTL elements into other disciplines, such as history, geography, and art, thereby strengthening the practical application of the language. Additionally, and more importantly, it is essential to encourage community involvement in school education, leveraging community resources and knowledge to enrich GTL teaching and ensure the accuracy and relevance of GTL in real-life contexts.

Appendix: Interview Outline

Introduction to the Interview

Self-introduction

Briefly describe the purpose of the interview

Explain to the other person that the interview will be anonymous, that a voice recording is required, etc.

Personal information

Personal information, including Identity, Age, Living area, etc.

Main Interview Questions

On a scale of 1–10, how would you rate your proficiency in spoken Tibetan?

Similarly, on a scale of 1–10, how would you rate your proficiency in written Tibetan?

Can you describe your experience of learning the GTL, including any formal education, self-study, or immersion experiences?

Could you provide examples of situations where you commonly use Tibetan in your daily life or professional activities?

What factors motivated or inspired you to learn and continue using the Tibetan language?

Reflecting on your education, were you taught about the history and cultural significance of the Tibetan language within your ethnic group?

Do you perceive a need or opportunity to introduce Tibetan language and culture to individuals from other ethnic backgrounds? If so, how?

From your perspective, what are the primary challenges facing the preservation of the Tibetan language today, particularly in the digital age?

In your opinion, how can digital technology be leveraged to support the preservation and dissemination of the Tibetan language?

Have you observed any efforts or initiatives by local government authorities aimed at protecting or promoting the Tibetan language, particularly through digital means?

Have you personally engaged in any activities or projects focused on preserving the Tibetan language using digital tools or platforms?

What opportunities or channels do you see for individuals like yourself to contribute to ongoing efforts in preserving the Tibetan language, particularly through digital means?

In your view, what specific steps or strategies should be prioritized to ensure the long-term preservation and vitality of the Tibetan language in the digital era? (Please list as many as possible)

References

Adams, W. C. 2015. “Conducting Semi-Structured Interviews.” In Handbook of Practical Program Evaluation, 492–505. Hoboken, NJ: Jossy-Bass.10.1002/9781119171386.ch19Search in Google Scholar

Androutsopoulos, J. 2011. “Language Change and Digital Media: A Review of Conceptions and Evidence.” Standard Languages and Language Standards in a Changing Europe 1: 145–59.Search in Google Scholar

Arifin, S. R. M. 2018. “Ethical Considerations in Qualitative Study.” International Journal of Care Scholars 1 (2): 30–3. https://doi.org/10.31436/ijcs.v1i2.82.Search in Google Scholar

Bowen, G. A. 2009. “Document Analysis as a Qualitative Research Method.” Qualitative Research Journal 9 (2): 27–40. https://doi.org/10.3316/qrj0902027.Search in Google Scholar

Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.Search in Google Scholar

Brown, D., and G. Nicholas. 2012. “Protecting Indigenous Cultural Property in the Age of Digital Democracy: Institutional and Communal Responses to Canadian First Nations and Māori Heritage Concerns.” Journal of Material Culture 17 (3): 307–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359183512454065.Search in Google Scholar

Cassels, M. 2019. “Indigenous Languages in New Media: Opportunities and Challenges for Language Revitalization.” Working Papers of the Linguistics Circle 29 (1): 25–43.Search in Google Scholar

Casumbal-Salazar, I. 2017. “A Fictive Kinship: Making “Modernity,” “Ancient Hawaiians,” and the Telescopes on Mauna Kea.” Native American and Indigenous Studies 4 (2): 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1353/nai.2017.a703400.Search in Google Scholar

Dearnley, C. 2005. “A Reflection on the Use of Semi-structured Interviews.” Nurse Researcher 13 (1): 19–28, https://doi.org/10.7748/nr2005.07.13.1.19.c5997.Search in Google Scholar

Denzin, N. K., and Y. S. Lincoln. 1998. The Landscape of Qualitative Research: Theories and Issues. London: Sage Publications.Search in Google Scholar

Desalegn, B. B., C. Lambert, S. Riedel, T. Negese, and H. K. Biesalski. 2019. “Feeding Practices and Undernutrition in 6-23-Month-Old Children of Orthodox Christian Mothers in Rural Tigray, Ethiopia: Longitudinal Study.” Nutrients 11 (1): 138–53, https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11010138.Search in Google Scholar

Duoerji, H. 2015. “Jiarong Tibetan Language Studies.” China Tibetology 4 (1): 150–211.Search in Google Scholar

Eisenlohr, P. 2004. “Language Revitalization and New Technologies: Cultures of Electronic Mediation and the Refiguring of Communities.” Annual Review of Anthropology 33 (1): 21–45, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.anthro.33.070203.143900.Search in Google Scholar

Fan, J. J. 2018. “Protection of the Digital Heritage of Minority Languages.” Journal of Northwest University for Nationalities 5 (3): 135–9.Search in Google Scholar

Fishman, J. A. 2001. Can Threatened Languages Be Saved? Reversing Language Shift, Revisited: A 21st Century Perspective. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.Search in Google Scholar

Galla, C. K. 2018. “Digital Realities of Indigenous Language Revitalization: A Look at Hawaiian Language Technology in the Modern World.” Language and Literacy 20 (3): 100–20. https://doi.org/10.20360/langandlit29412.Search in Google Scholar

Galla, C. K. 2016. “Indigenous Language Revitalization, Promotion, and Education: Function of Digital Technology.” Computer Assisted Language Learning 29 (7): 1137–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2016.1166137.Search in Google Scholar

Giglitto, D., L. Ciolfi, C. Claisse, and E. Lockley. 2019. “Bridging Cultural Heritage and Communities Through Digital Technologies: Understanding Perspectives and Challenges.” Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Communities & Technologies-Transforming Communities 1 (1): 81–91.10.1145/3328320.3328386Search in Google Scholar

Graham, J., B. A. Nosek, J. Haidt, R. Iyer, S. Koleva, and P. H. Ditto. 2011. “Mapping the Moral Domain.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 101 (2): 366. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021847.Search in Google Scholar

Greene, J. C., H. Kreider, and E. Mayer. 2005. “Combining Qualitative and Quantitative Methods in Social Inquiry.” Research Methods in the Social Sciences 1: 275–82.Search in Google Scholar

Hafner, C. A., A. Chik, and R. Jones. 2015. Digital Literacies and Language Learning, 19, 3rd ed., 1–7. Reading, UK: Language Learning & Technology.Search in Google Scholar

Hill, J. H. 2002. “Expert Rhetorics in Advocacy for Endangered Languages: Who Is Listening, and What Do They Hear?” Journal of Linguistic Anthropology 12 (2): 119–33. https://doi.org/10.1525/jlin.2002.12.2.119.Search in Google Scholar

Hinton, L. 2011. “Language Revitalization and Language Pedagogy: New Teaching and Learning Strategies.” Language and Education 25 (4): 307–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500782.2011.577220.Search in Google Scholar

Jia, L. 2023. “The Dilemma and the Way Out for the Protection of Minority Languages in China in the Information Age.” 1. Heilongjiang, China: The Border Economy and Culture.Search in Google Scholar

Junker, M. O. 2018. “Participatory Action Research for Indigenous Linguistics in the Digital Age.” In Insights From Practices in Community-Based Research: From Theory to Practice Around the Globe, 164–75. Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter Mouton.10.1515/9783110527018-009Search in Google Scholar

Lakhan, R., and K. Laxman. 2018. “The Situated Role of Technology in Enhancing the Academic Performance of Indigenous Students in Mathematics Learning: Application within a Maori Cultural Context in New Zealand.” I-Manager’s Journal of Educational Technology 15 (1): 26–39. https://doi.org/10.26634/jet.15.1.14615.Search in Google Scholar

Lantaya, L., R. Bonifacio, G. Jabagat, L. J. Ilongo, E. Caryl, G. Lucday, and R. Maluenda. 2021. “Beyond Extinction: Preservation and Maintenance of Endangered Indigenous Languages in the Philippines.” International Journal of Scientific & Technology Research 10 (12): 54–61.Search in Google Scholar

Lewis, M. P., and G. Simons. 2016. Sustaining Language Use: Perspectives On Community-Based Language Development. Dallas: SIL International.Search in Google Scholar

Li, J., A. Brar, and N. Roihan. 2021. “The Use of Digital Technology to Enhance Language and Literacy Skills for Indigenous People: A Systematic Literature Review.” Computers and Education Open 2 (1): 100035, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.caeo.2021.100035.Search in Google Scholar

Li, L., and P. Nyima. 2010. “The Analysis on the Challenge of Bilingual Education in Khampa and Amdo Dialeet Areas: Basing on the Educational Anthropology Field Work about the Bilingual Education of Ganzi Danpa County in Sichuan Province.” Tibetian Studies 120 (2).Search in Google Scholar

Li, M., and R. Woolrych. 2021. “Experiences of Older People and Social Inclusion in Relation to Smart “Age-friendly” Cities: A Case Study of Chongqing, China.” Frontiers in Public Health 9 (1): 779913, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.779913.Search in Google Scholar

Mager, M., X. Gutierrez-Vasques, G. Sierra, and I. Meza. 2018. “Challenges of Language Technologies for the Indigenous Languages of the Americas,” In Proceedings of the 27th International Conference on Computational Linguistics, 55–69. Santa Fe, New Mexico, USA.Search in Google Scholar

Manžuch, Z. 2017. “Ethical Issues in Digitization of Cultural Heritage.” Journal of Contemporary Archival Studies 4 (2): 4.Search in Google Scholar

Marcu, G., S. J. Ondersma, A. N. Spiller, B. M. Broderick, R. Kadri, and L. R. Buis. 2022. “Barriers and Considerations in the Design and Implementation of Digital Behavioral Interventions: Qualitative Analysis.” Journal of Medical Internet Research 24 (3): e34301. https://doi.org/10.2196/34301.Search in Google Scholar

McLuhan, M. 1964. Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man. New York: McGraw-Hill.Search in Google Scholar

Meighan, P. J. 2022. “Indigenous Language Revitalization Using TEK-Nology: How Can Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) and Technology Support Intergenerational Language Transmission?” Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development.10.1080/01434632.2022.2084548Search in Google Scholar

Ovide, E., and F. J. García-peñalvo. 2016. “A Technology-Based Approach to Revitalise Indigenous Languages and Cultures in Online Environments.” Fourth International Conference on Technological Ecosystems for Enhancing Multiculturality – TEEM 1 (1): 1155–60.10.1145/3012430.3012662Search in Google Scholar

Phyak, P. 2021. “Epistemicide, Deficit Language Ideology, and (de)Coloniality in Language Education Policy.” International Journal of the Sociology of Language 2021 (267–268): 219–33. https://doi.org/10.1515/ijsl-2020-0104.Search in Google Scholar

Qu, A. T. 1984. “Overview of the Gyalrong Language.” Minority languages Of China 2 (14).Search in Google Scholar

Qu, A. T. 1990. “Dialects of Jiarong — Dialect Division and Linguistic Identification.” Minority Languages of China 4 (8): 1–8.Search in Google Scholar

Qu, A. T. 2010. “Protection of Ethnic Languages Vocabulary and Intangible Cultural Heritage.” Minority Translators Journal 4 (1): 7–14.Search in Google Scholar

Qu, A. T. 2014. “Investigation and Research on the Use of Spoken and Written Languages of Ethnic Minorities in China.” Minority Translators Journal 4 (1): 5–19.Search in Google Scholar

Que, D. 1995. Gyalrong Ethnohistory. China: The Ethnic Publishing House.Search in Google Scholar

Rabianski, J. S. 2003. “Primary and Secondary Data: Concepts, Concerns, Errors, and Issues.” The Appraisal Journal 71 (1): 43.Search in Google Scholar

Richardson, A. J. 2012. “Paradigms, Theory and Management Accounting Practice: A Comment on Parker (Forthcoming) “Qualitative Management Accounting Research: Assessing Deliverables and Relevance”.” Critical Perspectives on Accounting 23 (1): 83–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpa.2011.05.003.Search in Google Scholar

Robinson, G. W., E. Lee, S. R. Silburn, P. Nagel, B. Leckning, and R. Midford. 2020. School-Based Prevention in Very Remote Settings: A Feasibility Trial of Methods and Measures for the Evaluation of a Social Emotional Learning Program for Indigenous Students in Remote Northern Australia, 8. Lausanne, Switzerland: Public Health.10.3389/fpubh.2020.552878Search in Google Scholar

Roche, G., and H. Suzuki. 2018. “Tibet’s Minority Languages: Diversity and Endangerment.” Modern Asian Studies 52 (4): 1227–78. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0026749x1600072x.Search in Google Scholar

Ross, M. W., M. Y. Iguchi, and S. Panicker. 2018. “Ethical Aspects of Data Sharing and Research Participant Protections.” American Psychologist 73 (2): 138. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000240.Search in Google Scholar

Salazar, J. F. 2007. “Indigenous Peoples and the Cultural Construction of Information and Communication Technology (ICT) in Latin America.” In Information Technology and Indigenous People, edited by L. E. Dyson, M. Hendriks, and S. Grant, 14–26. U.S.: Information Science.10.4018/978-1-59904-298-5.ch002Search in Google Scholar

Shi, S. 2014. “Discussion on the Formation Process of the Three Traditional Geographical Regions of the Tibetan People.” China Tibetology 9 (3): 51–9.Search in Google Scholar

Sianturi, M., J. S. Lee, and T. M. Cumming. 2023. “Using Technology to Facilitate Partnerships Between Schools and Indigenous Parents: A Narrative Review.” Education and Information Technologies 28 (5): 6141–64. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-022-11427-4.Search in Google Scholar

Spiro, L. 2012. “Opening up Digital Humanities Education. Brett D. Hirsch (Hg.).” Digital humanities Pedagogy: Principles and Politics 331–63.10.2307/j.ctt5vjtt3.19Search in Google Scholar

Suzuki, H. 2016. “Tibetan Dialectology Research and Language Map: How to Treat the Kham Dialect.” Journal of Ethnology 7 (2): 92–4.Search in Google Scholar

Taguchi, N. 2018. “Description and Explanation of Pragmatic Development: Quantitative, Qualitative, and Mixed Methods Research.” System 75 (1): 23–32, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2018.03.010.Search in Google Scholar

Tashi, N., and T. Drudrup. 2011. “On Gyalrong Dialect of Tibetan Language — Interview with Guillaume Jacques, a French Linguist.” Journal of Tibet University 26 (3): 1–4.Search in Google Scholar

Terras, M., J. Nyhan, and E. Vanhoutte. 2013. Defining Digital Humanities: A Reader, edited by M. Terras, J. Nyhan, and E. Vanhoutte. U.K.: Ashgate Publishing.Search in Google Scholar

UNESCO. 2003. Basic Texts of the 2003 Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage. France: UNESCO.Search in Google Scholar

Wang, Y. X. 2006. Chinese Ethnolinguistics: Theory and Practice. China: The Ethnic Publishing House.Search in Google Scholar

Wiltshire, B., S. Bird, and R. Hardwick. 2022. “Understanding How Language Revitalisation Works: A Realist Synthesis.” Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 1–17, https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2022.2134877.Search in Google Scholar

Zhao, L. 2022. “Exploration on the Protection of Minority Languages and the Development of Language Industry: A Case Study of Unique Minority Languages in Gansu Province.” New Silk Road 1 (12): 109.Search in Google Scholar

Zhou, Q. S. 2010. “Overview of Chinese Sociolinguistic Research.” Applied Linguistics (4): 10–21.Search in Google Scholar

Zhu, D. K. 2021. “The Targeted Protection of Ethnic Minority Language Resources: A Study Based on Live Data Collected for “China’s Language Resources Protection Project”.” Minority Languages of China 6 (3).Search in Google Scholar

Zuckermann, G. 2020. Revivalistics: From the Genesis of Israeli to Language Reclamation in Australia and Beyond. New York: Oxford University Press.10.1093/oso/9780199812776.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Going Beyond Digital Preservation

- Articles

- Historical Depictions, Archaeological Practices, and the Construct of Cultural Heritage in Commercial Video Games: The Role of These Games in Raising Awareness

- Digital is Not the Alternative: Dilemma and Preserving Films in India

- Digital Transformation of Archives in the Context of the Introduction of an Electronic Document Management System in Kazakhstan

- Cultural Preservation Through Immersive Technology: The Metaverse as a Pathway to the Past

- The Function of Digital Technology in Minority Language Preservation: The Case of the Gyalrong Tibetan Language

- What Needs to be Learned by U.S. Cultural Heritage Professionals? Results from the Digital Preservation Outreach & Education Network

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Going Beyond Digital Preservation

- Articles

- Historical Depictions, Archaeological Practices, and the Construct of Cultural Heritage in Commercial Video Games: The Role of These Games in Raising Awareness

- Digital is Not the Alternative: Dilemma and Preserving Films in India

- Digital Transformation of Archives in the Context of the Introduction of an Electronic Document Management System in Kazakhstan

- Cultural Preservation Through Immersive Technology: The Metaverse as a Pathway to the Past

- The Function of Digital Technology in Minority Language Preservation: The Case of the Gyalrong Tibetan Language

- What Needs to be Learned by U.S. Cultural Heritage Professionals? Results from the Digital Preservation Outreach & Education Network