Abstract

The study supplements manuscript digitization, which often overlooks owners’ role in manuscript literacy, highlighting their integral connection to preservation efforts. This is particularly relevant concerning Ambon manuscripts in the former Hitu kingdom. The study’s primary objective is to discern optimal practices for sustainable preservation, emphasizing the community owners not as passive entities but as individuals possessing significant knowledge and skills, competencies which can be effectively employed to safeguard and uphold manuscripts. The data collection process encompassed comprehensive literature reviews on digital manuscript collections, interviews with owners, focus group discussions (FGD) involving the younger generation of heirs, FGD with Ambon manuscript researchers at IAIN Ambon, and observations on manuscripts and cultural practices within the community. The findings reveal notable aspects such as: 1) degradation occurs in Ambon manuscripts, both in their physical state and the transmission of knowledge post-digitization, which underscores a deficiency in knowledge transfer between manuscript users and owners, representing an ethical responsibility; 2) within Ambon society, old houses function as literacy centers for the community. Given the substantial quantity of manuscripts, these houses should be recognized as scriptoria and serve as foundational points for manuscript-based literacy development; and 3) traditional practices within owner communities indicate that manuscript knowledge/literacy extends beyond basic reading and writing skills. It encompasses a holistic and comprehensive understanding of knowledge, including its relevance to daily life, categorization, origins, literacy, preservation skills (particularly caring and copying), and utilization (for legitimacy, anticipation/conflict resolution, and even economic purposes).

1 Introduction

To guarantee the enduring accessibility of heritage materials, such as manuscripts, long-term preservation is a critical concern. This awareness also informs contemporary methods and approaches to manuscript preservation, including physical preservation, care, conservation, digitization, microfilm creation, and documentation (Lone, Wahid, and Shakoor 2021). Physical preservation entails safeguarding manuscripts from physical damage, such as storing them in a controlled environment with stable temperature, humidity, and light levels (Balloffet and Hille 2005).

One modern method that is currently in vogue is digitalization. Digitization helps minimize the need to handle original manuscripts and reduces the risk of damage, while conservation care involves physical maintenance to repair and stabilize manuscripts (Manernova 2015). Digitalization is intended to mitigate the expensive physical management of materials. Consequently, it often overlooks the maintenance of physical manuscripts, presuming that access to the content is sufficiently secured.

Numerous studies suggest that digital data storage is susceptible to vulnerabilities and inherent challenges. While digitization holds the promise of a bright future, it also presents several challenges that require attention, including digitization expenses, backward compatibility concerns, and obstacles related to recognizing and utilizing cultural heritage resources for younger generations (Balen and Vandesande 2015). Balogun (2023) underscores numerous concerns stemming from the digitization of traditional knowledge, including the authenticity, integrity, and cultural sensitivity of its digital representation. Moreover, it is important to recognize that content on a website remains susceptible to alteration or disappearance.

These challenges suggest that preserving manuscripts necessitates a sustainable approach, wherein physical conservation and digitization work together effectively to ensure information retention, even in instances of manuscript damage or loss (Baquee and Raza 2020). The sustainability of this cultural heritage demands comprehensive support, encompassing assistance from providers, user-friendly system applications, and initiatives promoting education and awareness related to digital cultural heritage documents (Kramer-Smyth 2019). However, while digitization holds promise for the future, it comes with challenges that require attention, including digitization costs, issues related to backward compatibility, and challenges associated with recognition programs and utilizing cultural heritage sources for younger generations (Balen and Vandesande 2015). In this case, preservation of manuscripts necessitates an enduring strategy and active community involvement (Saptouw 2020).

The active participation of the local community in the cultural heritage preservation process should be considered through methods that involve them recognizing their wealth of knowledge and skills that can be employed to protect and preserve manuscripts (Oinam and Thoidingjam 2019). Beyond facilitating broad access, the utilization of manuscripts by owners and the local community is crucial, encapsulating independent manuscript preservation practices.

Manuscript preservation practices are believed to be inherent in traditional methods due to their pivotal role in ensuring the longevity and accessibility of historical and cultural information for future generations (Rios et al. 2020). Creating microfilm manuscripts involves producing high-resolution negative film for the preservation and enhanced accessibility of information (Mandal, Deborah, and Pedersen 2023). Documentation entails detailed records of manuscripts’ condition, content, and history, informing preservation efforts and research (Hassani 2015). The mastery and development of these methods are profoundly influenced by emotional attachment and an understanding of the significance of manuscripts or manuscript literacy.

In light of the profound emotional connection between owners and their manuscripts, Ambon manuscripts warrant special attention. These manuscripts constitute a collection of ancient text fragments discovered on Ambon in Maluku, Indonesia. Ambon manuscripts hold substantial value as a source of civilization across different epochs. Since the VOC and Dutch era, Ambon has evolved into a key center for spice cultivation and trade, emerging as a significant city in the archipelago and presently serving as the provincial capital (Azra 2015). These manuscripts bear historical and cultural significance, offering insights into literary and linguistic traditions in the region, as well as religious practices and beliefs (Gallop 2020; Handoko 2015; Ma’rifat 2014). Ambon manuscripts are valuable for their religious connotations and play a pivotal role in economic, social, cultural, and academic aspects. However, their utmost relevance to the owner community lies in their legitimizing function for uninterrupted continuity of the royal succession since its mythical origin (Braginsky 2004; Chambert Loir 2005). This importance explains why the Ambon manuscripts continue to be preserved in the households of residents, where they are meticulously maintained independently.

The intense emotional bond, cultural relevance, and legitimizing function underlie our suspicion that traditional practices conducted by the local community are in place to preserve Ambon manuscripts. This study seeks to unveil these practices, studying them to understand the motivations for manuscript preservation in the Maluku community and exploring their potential development as a model for independent and sustainable preservation.

2 Literature Review

Numerous nations worldwide, through their respective libraries, including India, China, South Africa, Korea, Indonesia, and Venezuela, have undertaken digital process-oriented preservation endeavors over the years to ensure enduring access to traditional knowledge reservoirs (Balogun 2023). The proliferation of digital databases and interactive virtual reality technologies has gained traction due to their provision of practical avenues and experiential avenues for the preservation, transmission, cross-border communication, and sustainable innovation of heritage (Yu 2023). Nonetheless, within the framework of sustainable preservation, the digitization of traditional knowledge faces diverse challenges.

Numerous scholarly investigations have elucidated the persistent vulnerability of digital archive storage concerning local knowledge, highlighting risks of loss or deterioration. Comparative analyses of digitization efforts targeting traditional knowledge reservoirs across three African nations – Nigeria, South Africa, and Uganda – have brought these challenges to light. Biela, Oyelude, and Haumba (2016) identified several impediments, including constrained financial resources, skill shortages in digital management, inadequate infrastructure, and limitations in preservation media. Furthermore, research findings underscore the considerable reliance of institutional digital preservation endeavors on international funding sources.

These challenges are also evident in digital preservation initiatives in countries such as Indonesia. Initiatives for digitalization often hinge on external financial support, exemplified by programs like the Endangered Archives Programme (EAP) and DREAMSEA. Meanwhile, endeavors by local entities, like the Language Agency and the Ministry of Religion, have yet to yield publicly accessible databases.

An additional salient concern revolves around the capacity of digital archives to authentically represent culture in comparison to original sources. Balogun (2023) has articulated reservations regarding the authenticity and fidelity of indigenous knowledge representation within digital repositories. Furthermore, digital archives continue to face limitations in faithfully capturing indigenous knowledge relative to its analog counterparts. Consequently, the preservation and administration of Indigenous Knowledge Systems (IKS) in South Africa provide a framework through which indigenous communities can reclaim, validate, and disseminate their knowledge within the context of their cultural milieu (Christen 2015; Montenegro 2023).

The implementation of IKS in South Africa underscores the pivotal role of communities in safeguarding local knowledge assets. Local stakeholders are afforded opportunities to actively participate in the preservation process. Nevertheless, this framework has yet to prioritize community ownership as the central focus of preservation efforts. Nonetheless, the profound cultural significance of indigenous knowledge to community livelihoods serves as a compelling impetus for community engagement in preservation endeavors. The challenges encountered in digital preservation efforts underscore the imperative of balancing digitization with physical preservation as the primary means of safeguarding local knowledge for sustainable preservation.

These two issues are highly relevant to the characteristics of Ambon manuscripts in their capacity as traditional knowledge sources. It is estimated that up today, around 200 Ambon manuscripts are still privately held by local communities (https://eap.bl.uk/project/EAP276). The significance of local knowledge sources to the culture, which fosters strong ownership, is evident in the ownership of Ambon manuscripts. One of the crucial contents of Ambon manuscripts is pertinent to the legitimization of uninterrupted leadership succession among Ambon nobility (Braginsky 2004; Chambert-Loir 2005). This legitimizing function is believed to be why Ambon manuscripts are difficult to be entrusted to other parties, such as libraries, for safekeeping. Additionally, their role in religious propagation (Handoko 2015), their function in cultural rituals (Ma’rifat 2014), and supernatural reasons are other factors why communities still keep manuscripts in their homes.

Considering the condition and characteristics of Ambon manuscripts, Community-Based Preservation is the most ideal approach. In this context, Ambon manuscripts are seen as cultural heritage. The definition of cultural heritage is not confined to a single definitive meaning but can be adjusted to the required context. Some key principles include 1) tangible or intangible assets owned and recognized by a group of people; 2) inherited across generations (Gireesh Kumar and Raman Nair 2022; Logan 2007); and 3) possessing symbolic, artistic, aesthetic, ethnological, anthropological, and social significance (UNESCO Institute for Statistics 2009). Ambon manuscripts are classified as tangible culture, making community-based preservation the most suitable strategy for sustainable preservation.

Community-based preservation is a people-centered approach in building community-based processes to manage cultural heritage connected to religious affiliations, traditions, social networks, and everyday aspects of local communities (Khalaf 2016; Li et al. 2020; Wijesuriya, Thompson, and Court 2017). The focus of this approach is problem-solving based on the needs of the subjects. Active community participation can be the primary driver in maintaining the continuity of cultural heritage like Ambon manuscripts.

Local community participation is heavily emphasized in sustainable cultural preservation endeavors. This involvement spans various levels, from information gathering to decision-making within the preservation process. Engaging the community enriches knowledge about cultural heritage and fosters a sense of ownership and responsibility for preservation. The sustainability of Ambon manuscript preservation can be attained by integrating community participation as a central element, recognized as crucial in overcoming challenges and obstacles in manuscript preservation while ensuring the manuscripts’ ongoing relevance and benefit to the local community.

Moreover, within the social network of manuscript owners, various stakeholders surrounding cultural heritage must collaborate as interdependent contributors, grounded in mutual respect as partners in a collective endeavor to effect change (Onciul 2017). Communities of manuscript owners cannot be left alone to preserve manuscripts; preservation efforts should involve various entities, such as educational institutions, that can instill pride in the cultural heritage they possess.

Culture and heritage have the potential to make positive contributions to social cohesion. Successful partnerships between authorities and traditional custodians have commenced at cultural sites with the goal of building awareness and local involvement in heritage preservation, such as the collaboration with stonemasons in rebuilding tombs in Timbuktu. Such approaches empower local communities to play a role in heritage preservation, reinforce a sense of ownership, and support local economies related to craftsmanship and conservation. Increased involvement of local authorities also fosters new collaborative partnerships in conservation and urban regeneration efforts, supporting citizen pride, local empowerment, and inclusive community projects (UNESCO 2016).

The preservation process must encompass inventorying and identifying threats to cultural heritage elements such as manuscripts. Based on this information, preservation and revitalization plans can be developed. When physical preservation of cultural heritage is not feasible due to a lack of funds and expertise, digital preservation is considered an alternative to safeguard cultural heritage (Yahia and Bouslama 2023). The preservation of digital content emerges as an enduring solution to various threats, including damage, warfare, fires, and floods (Trillo et al. 2020). This ensures the preservation and availability of valuable resources for succeeding generations of scholars. Nevertheless, it is imperative to ascertain that forthcoming generations possess the capability to access and benefit from this digital heritage.

Communities are urged to actively preserve and manage their cultural heritage, encompassing items such as manuscripts. This active engagement is crucial, as communities are uniquely positioned to consolidate their cultural existence and secure their future. Drawing upon collective memory and historical awareness, each community is responsible for identifying and managing its cultural heritage. Mainly, indigenous communities, groups, and, in certain instances, individuals assume pivotal roles in the production, protection, preservation, and recreation of intangible cultural heritage. Within the broader context of cultural heritage preservation, every nation should endeavor to facilitate the involvement of numerous communities, groups, and individuals – those instrumental in creating, maintaining, and transmitting such heritage. Their active participation in cultural heritage management is vital (Mekonnen, Bires, and Berhanu 2022).

This study aims to position the community at the forefront of Ambon manuscript preservation efforts. This is accomplished by investigating the practices observed within the communities of manuscript owners. The objective is to initiate strategies for sustainable preservation using a bottom-up approach.

3 Objectives of Study

The objectives of this study are as follows:

To evaluate the condition of Ambon manuscripts subsequent to digital preservation by comparing the quantity and quality of digital archives with field conditions.

To elucidate prevailing preservation traditions within the Ambon community, their accessibility, and transmission, achieved through focus group discussions with the younger generation.

To discern patterns of attachment and engagement among manuscript-owning communities in the preservation of Ambon manuscripts.

To formulate a sustainable model for preserving Ambon manuscripts that ensures the continuity of traditional knowledge while integrating with modernity.

4 Methodology

Data were systematically gathered through an extensive literature review encompassing digital manuscript collections from various providers, including The British Library through the EAP project and the Ambon Manuscript Collection at the National Library of Indonesia. The data extracted from these two repositories comprise digital archives of Ambon manuscripts along with fundamental information about them. Furthermore, an examination of research conducted at State Islamic University of Ambon, the Language Office of Maluku Province, and Pattimura University was undertaken to identify sources supporting local community research on manuscripts, with these sources indispensable for comprehending the viewpoints of local academics regarding their heritage and cultural milieu. The primary objective of the literature review was to procure preliminary data and information crucial for delineating the areas of observation.

The study was geographically situated on Ambon Island, specifically within the confines of the former Hitu Kingdom/Jazirah Leihitu region. This selection was made intentionally, driven by the notion that each area could serve as a representative microcosm of geographic delineations within the Maluku Province. The study outcomes are anticipated to comprehensively encapsulate the conditions of the local communities and provide a nuanced overview of each distinct area. Numerous manuscripts are housed within the confines of the former Hitu Kingdom region, encompassing locations such as Hitumessing, Morella, Hila, and Kaitetu. Four distinct observation points were judiciously chosen: Kaitetu, Hitu Lama, Hitu Messing, and Morela, grounded in specific considerations. Firstly, these areas serve as repositories for storing and preserving Ambon manuscripts. Secondly, these communities actively engage in the preservation endeavors related to Ambon manuscripts.

The qualitative research explores the social phenomena intertwined with Ambon Manuscripts in the Maluku community. Consequently, this study focuses on the participants’ experiences, perspectives, and emotions concerning Ambon Manuscripts. Semi-structured interviews were meticulously conducted to acquire the necessary information, with key informants actively involved in the Ambon Manuscript preservation program within the region as well as representatives from the community and educational institutions linked to the content of Ambon Manuscripts interviewed. In-depth interviews were also conducted with the proprietors or familial custodians of manuscripts in Ambon, the chosen study location, to unravel the experiences, perspectives, and sentiments underlying the manuscript-centric social phenomenon. The interviews focused on two aspects: 1) community perspectives on managing Ambon Manuscripts; and 2) the potential for community participation in Ambon Manuscript preservation. Participants were purposively selected.

Purposive observation and snowball sampling were employed to scrutinize the social milieu engaged in traditional manuscript preservation practices in the Ambon community. Furthermore, data were garnered through Focus Group Discussions (FGD) with the younger generation to assess their involvement and sense of ownership towards the manuscripts while observing the intergenerational transmission of manuscript knowledge/literacy within a traditional context. The second FGD was facilitated by IAIN Ambon, involving cultural and Ambon manuscript researchers to extract additional insights.

At three designated observation points, assistance was extended through reading guidance, simple grouping/cataloging directives, and physical care for the manuscripts provided to the immediate heirs. This intervention marked the preliminary step towards fostering manuscript literacy within the owner community. Additional initiatives targeting the younger generation included training on accessing digitized Ambon manuscripts through provider websites, ensuring their exposure to knowledge and the inheritance of manuscript content. Community training sessions in fundamental preservation techniques and participatory conservation involving researchers and the community were conducted to undertake preservation tasks, document the preservation efforts, and outline manuscript descriptions as permanent records for future generations. The active involvement of the community renders these manuscripts more valuable, and the community is more inclined to assume ownership of preservation initiatives.

The collected data, in the form of texts, were analyzed qualitatively to uncover the experiences of the research subjects (Creswell and Creswell 2018). Information about manuscripts was systematically categorized based on physical attributes, content, emotional connections, community knowledge, traditional preservation practices, and community expectations regarding manuscript preservation. Any residual data was segregated into a distinct group to reassess its relevance to the study objectives. The grouped data was then streamlined based on alignment with the study objectives, with the condensed data then reviewed within a broader framework to uncover relationships between different data groups. These intergroup relationships served as a yardstick for evaluating the consistency of traditional manuscript preservation, hinging on emotional/motivational ties, knowledge, preservation practices, and feedback from these undertakings.

5 Analysis of Data

5.1 Degradation of Ambon Manuscripts After Digitization

Ambon possesses a significant number of manuscripts, including collections housed in traditional establishments (marga), spanning regions such as Keitetu, Hitu Lama, Hitumessing, and Morela. The British Library website notes that Ambon manuscripts consist of collections attributed to individuals such as Basri Ripamole, Gepi Latupono, Djafar Lain, Bangsa Amanullah, Awat Yahehet, Rahman Ali Salampessy, Sait Manilet, Abdullah Pelu, Husain Hatuwe, Salhana Pelu, Sarajudin Hatuina, and Usman Hataul.

The manuscripts, predominantly originating from the erstwhile traditional Hitu dukedoms, are concentrated in the ancestral homes of the respective marga, with each ancestral residence harboring a substantial number of manuscripts. For instance, the Hatuwe ancestral home in the village of Wapauwe near the Keitetu region houses 65 manuscripts encompassing the Quran, prayer compilations, sermons, Islamic teachings, fiqh (creed), and horoscopes. The British Library has cataloged 194 manuscripts from diverse locations in Maluku (https://eap.bl.uk/project/EAP276), while the research team from the University of Indonesia has documented 92 manuscripts exclusively from the former Hitu dukedom. The inventory conducted in this study suggests that the actual number of manuscripts is considerably more prominent, with each ancestral home functioning as a distinct scriptorium. However, certain digitally inventoried manuscripts remain unaccounted for, possibly attributed to the indigenous communities’ tendency to withhold certain manuscripts from public view.

In scrutinizing preservation aspects, this study confines its examination to inventoried manuscripts. The outcomes are delineated in the ensuing table (Table 1).

Manuscript quantity comparison.

| Data source | Observation area | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Wapauwe/Kaitetu | Morela | Hitu Messing | |

| British Library (2009) | 66 | 18 | 32 |

| Center for Islamic Manuscript Studies and Philology (2020) | 63 | 8 | 7 |

| Field Observations (2023) | 27 | 8 | 7 |

The depiction derived from the table above signifies a reduction in the number of manuscripts in Maluku. According to the proprietors, publishing manuscripts has fostered an increased interest in studying Maluku manuscripts. Furthermore, local governments frequently borrow these manuscripts for cultural exhibitions, however, the lack of responsibility and ethical considerations has led to the loss, damage, or inadequate storage of some manuscripts. Additionally, cultural beliefs attributing magical effects to manuscripts result in specific individuals, typically close family members, appropriating them for use as talismans. Consequently, this has contributed to a decline in the quantity of Ambon manuscripts[1] (Focus group discussion, August 21, 2023).

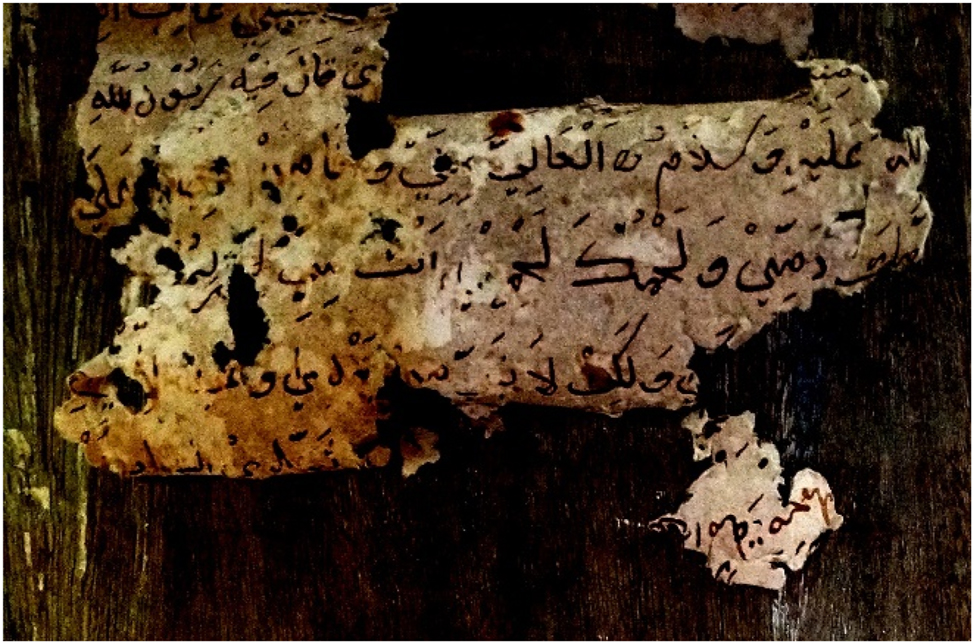

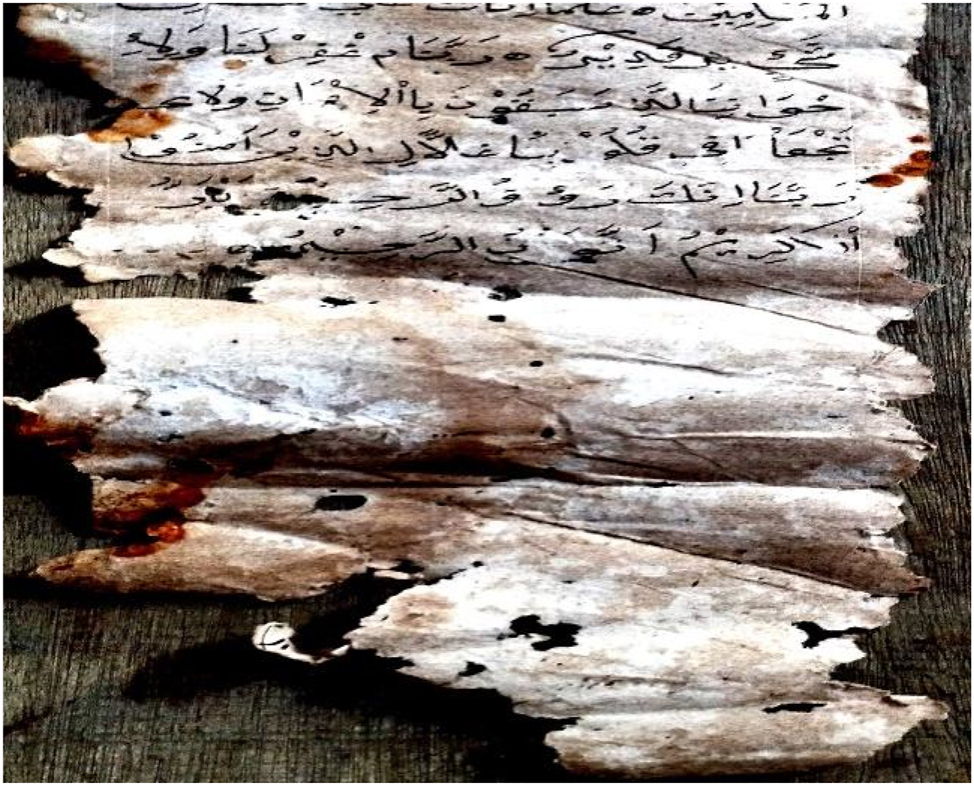

A diminishing trend is also noticeable in the quality of the manuscripts. Numerous manuscript papers have incurred damage, with the most severe condition observed in the Manilet house, where, after post-exhibition borrowing, their manuscripts were stacked haphazardly, leading to the intermixing of numerous pages. Only eight units could be identified throughout the study as intact manuscript entities, while the remainder persisted in unidentified pile formations. Several scroll manuscripts have also undergone decay and discoloration due to insufficient care (Figures 1 and 2).

Physical condition of the Manilet manuscript collection. Primary data.

Physical condition of the scroll manuscripts in the Manilet Collection. Primary data.

The Wapauwe/Kaitetu collection exhibits a slightly superior condition due to the preceding digitization process, which was accompanied by fundamental conservation endeavors. The scroll manuscripts have undergone protective coating with Japanese tissue, ensuring their relatively well-preserved state. Furthermore, the manuscripts are housed within a reasonably effective glass cabinet to uphold optimal humidity levels, however, despite the availability of a dedicated container for manuscript storage, it regrettably remains underutilized for its intended purpose. The principal challenge in maintaining the Wapauwe/Kaitetu collection pertains to cataloging. While it is apparent that previous research efforts have attended to the care and grouping of these manuscripts, a deficiency in knowledge transfer concerning cataloging and basic preservation practices has led to the manuscripts being once again stored in stacks (Figure 3).

Manuscript storage in the Wapauwe/Kaitetu collection (primary data).

The manuscripts housed in Hitu Messing display diverse conditions. Owners engage in personal preservation efforts, employing lamination for collections such as genealogies or dati register. However, evaluating the merit or detriment of this practice in the preservation context poses a challenge; while lamination effectively conserves the form and content of the manuscript, the subsequent extraction of the manuscript from the plastic proves exceedingly difficult.

Field observations affirm that post-digitization, there has been a degradation in the physical manuscripts, both quantitatively and qualitatively. The cultural use of manuscripts as talismans indicates a low level of manuscript literacy within the owner community, thereby threatening the physical sustainability of the manuscripts. Furthermore, the absence of knowledge transfer to the owners in the research or manuscript digitization processes renders prior efforts seemingly futile. These issues, coupled with irresponsible user behavior, reveal ethical shortcomings among manuscript users, especially concerning Ambon manuscripts.

5.2 Preservation Tradition and Manuscript Literacy in Ambonese Community

A notable characteristic of Ambon manuscripts lies in their relevance to the cultural aspects of the community. This connection is chiefly evident in manuscripts such as genealogies linked to the leadership of traditional regions in the former Hitu sultanate. Determining the lineage house of leaders (the ancestral home of regional kings) relies on these manuscripts. A similar practice governs the inheritance of imams and preachers, who must read sermon scroll manuscripts during their inauguration. The actualization and relevance of manuscript content in the cultural life of Ambon manuscripts hold a significant position, fostering a heightened level of community concern for them.

Broadly speaking, ownership rights of manuscripts are conferred upon clans, collectively referred to as “marga.” Each “marga” possesses an ancestral home where they store all their inventories and valuable items; for example, in Morela, the Manilet clan stores these items in the Manilet ancestral home, rather than in the king’s house:

The ancestral residence of the Manilet clan functions as the primary repository for their collection. Notably, this clan possesses a traditional house for this purpose. As a result, all inventories belonging to the Manilet clan find their place in their ancestral residence, distinct from the king’s house. This practice has evolved into a tradition within the Manilet clan, clearly separate from the royal residence. Essentially, each clan adheres to its own tradition; for instance, the Manilet clan stores its possessions exclusively in its ancestral house. It is important to note that this practice does not imply the possibility of the Manilet clan’s ancestral house transforming into a royal residence (Nurhijah Manilet, primary data, interview on August 11, 2023).

A similar approach is observed in Wapaue, where the majority of manuscripts are housed in the Hatuwe residence. This reflects a longstanding common practice in Maluku, where each clan meticulously nurtures and preserves its unique heritage.

Findings from interviews indicate varied roles and responsibilities for each clan. In the case of the Manilet clan (primary data), their principal role is in the leadership of mosques, enabling them to assume critical functions such as preachers or imams (prayer leaders) and potentially other roles in a religious context. Specific locations or residences, such as “Ulath House,” “Ligawa House,” “Latulani House,” “Manilet House,” “Sasoles House,” “Lauselen House,” and “Tenu House,” are individually owned by specific clans, each with its designated roles. Some residences have undergone modifications or renovations, while others have become private homes as owners extend their families through subsequent generations.

In the governance structure of Morela, the Sasole clan assumes a crucial role, which parallels the arrangements in former Hitu sultanate areas, such as Pellu in Hitu Lama and Hitu Messing. These clans possess distinct rights to fulfill significant positions, including kingship, and actively participate in the traditional governance structure with various administrative functions. Distinct roles and responsibilities within each clan’s social and customary structure influence the kinds of manuscripts they preserve:

The king’s residence typically does not house manuscripts, as those relevant to religious teachings are stored in the ancestral residence. In the instance of genealogies related to the kingdom, for example, the Sasole clan has maintained a comprehensive genealogy from the earliest civilization to the present territory. The Sasole clan shares a close relationship with the Sialana clan, fostering a sense of brotherhood. Consequently, proposals for the king selection process can be submitted by both the Sialana and Sasole clans (Nurhijah Manilet, primary data, interview on August 14, 2023).

Manuscripts stored in the king’s residence, traditionally called the leader’s house, typically comprise genealogies recorded from early civilizations to the present. Conversely, manuscripts preserved in other ancestral residences, such as Manilet, are primarily associated with religious teachings. In Morela, the Sasole and Sialana clans, entitled to the king’s position, maintain a bond of brotherhood. Both clans collectively hold the genealogy manuscripts, contingent on the current occupant of the king’s position.

In Indonesia, there has been a structural shift towards a democratic system in the official governance of Maluku. However, this structural transformation is not accompanied by cultural changes, with time-honored customs persisting and upheld by the local clans. Essentially, the traditional regional governance system, a practice deeply embedded over time, endures with certain modifications.

The preservation of this governance system represents a manifestation of manuscripts in everyday life. It underscores the manuscript’s cultural relevance, symbolizing the emotional connection between the community and these manuscripts. This significance often leads to the treatment of these manuscripts as cherished heirlooms, however, the storage and accessibility of these manuscripts depend on their specific types.

Access to genealogy manuscripts as legitimacy for the Regional King is challenging due to their secure storage. According to Pellu (interview on August 14, 2023), access restrictions are in place to maintain stability in village governance; even the retrieval of these manuscripts requires the presence of the entire extended family to ensure that there is no misuse (Figure 4).

Extended family presence during manuscript retrieval at the king’s residence in Hitu Messing.

The genealogical manuscript is transmitted through closed inheritance within the royal family, receiving specialized care due to its legitimizing function for the king’s position. The Hitu-Messing Royal Family’s genealogical manuscript is autonomously preserved through lamination or traditional methods involving spices like cloves, which are effective against insects and rodents but ineffective against decay. Despite the extinction of manuscript writing traditions, genealogical manuscript writing has no continuation, with this role supplanted by official government documents and oral transmission by Saniri (traditional custodians).

The storage of religious manuscripts is handled differently. In the observed areas, access to religious manuscripts tends to be open, with this ease of access aligning with the spirit of religion that must be disseminated. Actively, manuscript owners spread values contained in the manuscript through informal education at home. Manuscript owners like Husain Hatuwe (Ucen) are known as Quranic teachers in the village of Wapaue, which is manifested through an open hall large enough for children to learn Quranic recitation.

Most families, including their descendants, understand the content of the manuscripts. They have been taught to read the manuscripts, although the tradition of writing is no longer taught, which means that the tradition of transmitting the manuscript’s content continues today. However, the tradition of writing and copying manuscripts no longer continues to complement the traditional practice of inheriting manuscript literacy. The cessation of this tradition results from structural changes in society, where the Latin script is established as the official script in various domains. For pragmatic reasons, primarily to facilitate learning in public schools, the people of Maluku have taught their children to write in Latin script and abandon the Arabic script.

Manuscript literacy is generally construed as the capacity to peruse and inscribe manuscripts, comprehend their historical context, and discern their interrelations. This proficiency typically alludes to the aptitudes held by manuscript scholars, however, discoveries at Hitu Messing suggest that manuscript proprietors commonly possess manuscript literacy. Indeed, the manuscript literacy of manuscript proprietors encompasses a more intricate array of knowledge. The stature of manuscript inheritors as cultural luminaries, such as monarchs and clergy, not only necessitates proficiency in reading and writing (focus group discussion, August 21, 2023); according to Waulath (interview on August 22, 2023), a preacher must grasp the historical dimensions of manuscripts and their utilization in societal cultural customs, such as selecting an apt manuscript for recitation during mosque dome replacement ceremonies. It may be asserted that their manuscript literacy is intricately entwined with societal and cultural norms within the community.

Given its continued relevance to the contemporary lives of Maluku residents, the majority of manuscripts are presently undergoing maintenance, albeit under varying conditions. The manuscript collection curated by Husein Hatuwe is better preserved than other collections from the former sultanate of Hitu, such as those in Morela. Husein’s collection is meticulously organized within glass cases, with maintenance efforts primarily involving select members of the Hatuwe family. Inventories and digitization initiatives have been carried out by academic teams representing various institutions, including Universitas Indonesia, IAIN Ambon, Universitas Pattimura, Religious Research and Development Agency, and the Language Agency, who have disseminated their findings from inventory and digitization efforts through printed publications and digital copies. However, Husen Hatuwe himself lacks a comprehensive understanding of how to effectively utilize these resources.

Traditionally, Husen Hatuwe employs cloves placed within the showcase shelves, aiming to deter pests that could potentially damage the manuscripts, such as mites and rats. Alternatively, manuscripts are sometimes stored in bamboo, although this practice may inadvertently complicate retrieval efforts.

Using glass material in shelving is also advantageous for regulating manuscript humidity, thereby mitigating mold formation. Generally, manuscripts under Husen Hatuwe’s ownership remain in satisfactory condition due to the conservation efforts undertaken by visiting researchers. These efforts involve the application of Japanese tissue to damaged manuscripts, the provision of improved storage containers, and thorough cleaning.

Conversely, the condition of other manuscripts presents a contrasting picture, often exhibiting signs of decay attributed to neglect. Notably, numerous manuscripts have become unidentifiable within the premises of Morela’s house due to their haphazard storage. Nonetheless, despite these challenges, the owner Nurhijah remains resolute in retaining possession of her manuscripts, expressing a preference for their preservation even if it means their eventual deterioration on-site rather than their transfer to other parties, as articulated by Nurhijah Manilet (primary data, interview on August 14, 2023). Similarly, Husain Hatuwe echoes a comparable sentiment, underscoring the profound emotional connection between owners and their manuscripts. Indeed, manuscripts are regarded as integral components of one’s identity and ancestral legacy (interview on August 22, 2023).

Moreover, disseminating manuscript content and associated educational endeavors entails further implications for manuscript owners. There exists a tradition wherein descendants of owners pursue education in religious institutions. For instance, Khatib Ismail Waulath of Hitu Messing was sent by his parents to study religion at an Islamic boarding school in Java since junior high school. According to Khatib Ismail (interview on August 16, 2023), this tradition is deeply ingrained within religious leader families in Jazirah Leihitu, representing a commitment to the exclusive right to religious leadership. A similar practice is observed within the Manilet family of Morela and the Hatuwe family of Wapauwe.

The tradition of manuscript preservation in Maluku is upheld primarily by individuals holding specific cultural positions within the community. This practice is rooted in the inheritance of manuscripts as cherished family heirlooms, serving to validate and uphold their cultural significance.

Given their status as familial heirlooms, manuscripts are particularly cherished by families of royal lineage and those of religious leaders, such as the esteemed Hatuwe lineage. Husen Hatuwe, for instance, regards the manuscripts in his possession as symbolic representations of his family’s esteemed role as religious leaders in the village of Wapauwe. His collection, predominantly comprising religious knowledge, notably about Islam, is deemed essential for any Islamic scholar aspiring to lead religious affairs within the village community. Given that the succeeding imam typically hails from the same lineage (Hatuwe), passing down these manuscripts to future generations holds significant importance. However, it is evident from field observations that this inheritance transfer is primarily limited to the physical handover of manuscripts, with the content remaining dependent on the individual awareness of the succeeding heir to engage with them. Notably, there is yet to be an established pattern of educational initiatives within families to internalize the values encapsulated within these manuscripts for future generations.

To date, there have been no reported instances of manuscripts being traded, although there are occurrences of some manuscripts being borrowed but not returned, often utilized for research purposes or as components of final college assignments. Most manuscripts in Jazirah Leihitu exhibit signs of damage attributable to the natural aging process. While the owners acknowledge the importance of preserving these manuscripts, they express a sense of resignation towards their inevitable deterioration, given the challenges in averting such damage (primary data).

5.3 Community Attachment and Participation in Manuscript Preservation in Ambon

The cultural milieu in which political leaders, specifically kings and religious leaders, notably imams in customary villages, are traditionally inherited along direct descent lines significantly shapes the limited attention given to manuscript preservation. This involvement encompasses physical upkeep, documentation, and the cultivation of cultural comprehension. The community also contributes to safeguarding cultural heritage through diverse actions in manuscript preservation, comprehending its significance and understanding its impact on cultural identity in Ambon. Analyzing the extent of community engagement in these pivotal aspects will yield more profound insights into how local traditions and wisdom persist and evolve within the framework of manuscript preservation.

Empirical observations indicate that concern and attachment to manuscripts are predominantly evident within inheritor families. Profound structural shifts, particularly through formal education, erode the broader community’s connection to manuscripts (focus group discussion, August 21, 2023), while formal education has transitioned from informal educational patterns (Quranic studies), where manuscript knowledge was traditionally imparted. Nonetheless, observational evidence suggests that the general community was once strongly attached to manuscripts.

Primary evidence indicates that most individuals are aware of numerous manuscript scrolls in their vicinity and their respective storage locations. However, the surrounding populace still needs to discover specifics regarding which manuscripts are stored and their quantities. Access to manuscripts, especially religious ones, is openly available to all without the need for special rituals, but this accessibility presents both advantages and disadvantages. The primary peril lies in physical damage to the manuscripts and cataloging issues, leading to disorganization. In both Morela and Wapauwe, stacking manuscripts without proper categorization poses challenges for owners in locating specific manuscripts. Conversely, manuscripts are dispersed in Hitu Messing and Hitu Lama, resulting in varied storage conditions.

Although cultural changes in Maluku progressed relatively slowly, many traditions involving manuscripts within the community have been abandoned. Presently, scroll manuscripts are exclusively recited during the appointment of individuals as imams/preachers, as observed in Hitu Lama and Hitu Messing. However, Friday sermons no longer utilize scroll manuscripts, as Husain Hatuwe asserts they “do not bring tranquility.” This assertion underscores the sermons’ failure to consider the Maluku community’s multi-religious conditions adequately.

In reality, manuscript contents in the former sultanate lands of Hitu continue to serve as reference sources for village communities regarding politics and religious values. Particularly for religious values, they remain integral to the identity of the predominantly Muslim community in Jazirah Leihitu. While shifts in values are discernible, Islamic Sharia still permeates the village communities of Kaitetu and Wapauwe, however, the association between these values and manuscripts is waning, as manuscripts no longer serve as the primary medium for religious education (focus group discussion, August 21, 2023).

Manuscripts that retain relevance in community life are utilized to determine the date of Ramadan fasting. The community in Jazirah Leihitu still consults manuscript owners to determine the date of Ramadan 1. Similar to genealogical manuscripts, such manuscripts are laminated by owners for self-preservation. However, lamination is unfortunately an unsuitable preservation method, as the heat and adhesive used render physical repairs impossible.

Field observations indicate that previous digitization and conservation efforts could have actively engaged the community. However, digitalization initiatives lacked accompanying training in manuscript care and management for owners and the surrounding community, rendering the digitization process unsustainable. Moreover, the tradition of manuscript copying has ceased, making existing manuscripts invaluable specimens. The surrounding community tends to overlook the importance of manuscript preservation, delegating this responsibility to more adept entities such as academics and government employees (especially the National Library). While owners are open to transitioning to digital mediums, they still regard the original form as superior. Husain Hatuwe, owner of the Wapauwe/Kaitetu collection, and Nurhijah Manilet, owner of the Morela collection, acknowledge the likelihood of manuscript damage but delegate this to others due to their limited preservation skills.

Education, notably higher education, presents a paradox. Awareness of the importance of manuscripts grows among the educated, especially those in philological fields who actively research these manuscripts. Conversely, the surrounding community increasingly disregards manuscript importance despite their past close ties to Maluku life and identity.

In the context of manuscript preservation, community perceptions, motivations, and obstacles play pivotal roles. Community perceptions of a particular cultural heritage’s importance can influence whether manuscripts are deemed valuable. Motivations for manuscript preservation may stem from historical, cultural, and social factors, however, obstacles such as resource shortages, lack of knowledge, or support can impede preservation efforts. This study aims to delve deeper into how community perceptions, motivations, and obstacles intersect and impact manuscript preservation efforts, offering a nuanced understanding of cultural heritage preservation dynamics.

5.4 Collaboration for the Sustainability of Manuscript Preservation in Ambon: Continuity of Traditional Knowledge

Although typically confined to the upper echelons of society, the cultural comprehension and local consciousness of classical Ambon manuscripts have effectively preserved the community’s emotional bond and the ethos of inheriting the manuscript contents. The presence of external researchers, engaged in both research and digitization endeavors, enriches the owners’ grasp of the historical context, values, and cultural significance encapsulated within these manuscripts. Additionally, successive generations pursuing advanced education, particularly those specializing in philology, contribute to the appreciation of their intellectual heritage.

This cognizance has, to a limited extent, emerged from governmental initiatives. Thus far, the Maluku Provincial Government has undertaken promotional efforts, periodically showcasing Ambon manuscripts in exhibitions at various levels. These endeavors serve to foster a sense of pride and understanding regarding the manuscripts’ significance among their owners, while also acquainting the broader audience with these manuscripts as part of their intellectual legacy from the past. However, deficiencies in skills and knowledge concerning manuscript care have led to considerable damage post-lending, with some manuscripts even being lost after borrowing.

Apart from the regional government, numerous central government entities such as the Maluku Language Office, the Ministry of Religious Affairs Research and Development Agency, the National Library, and universities have contributed through research and digitization endeavors. Furthermore, institutions like the British Library and the Center for Islamic Manuscript Studies and Philology are also engaged in digitization efforts.

The advantages of digitization in preserving traditional knowledge are substantial. Benefits such as enhanced accessibility, widespread dissemination, and the potential for technological advancements to analyze manuscript content yield positive outcomes and novel prospects. Furthermore, presenting traditional manuscripts in digital format makes the contained knowledge more accessible to the younger generation raised in the digital age. Consequently, valuable intellectual heritage can be appreciated by specific groups and accessed by a broader audience interested in delving into and experiencing the cultural richness of their ancestors. Several traditional manuscripts encompass diverse local knowledge, including insights into agriculture, traditional medicine, and customary rituals. This approach significantly aids in maintaining the relevance of manuscripts for the younger generation in Jazirah Leihitu, who are growing up in an environment replete with digital resources (Table 2).

Preservation actors and their roles.

| Preservation actors | Roles in manuscript preservation |

|---|---|

| Manuscript owners | Transmitting manuscript content to future generations (limited within the family; traditional protection practices; dissemination of manuscripts through cultural practices). |

| Community owners | Cultivating a sense of ownership and emotional attachment through cultural practices. |

| Government | Promotion to foster a positive attitude towards manuscripts. |

| Academic institution | Digitization; academic dissemination. |

Although digitization presents various advantages, maintaining the continuity of traditional knowledge contained in Ambon manuscripts remains the primary objective that must be considered. Interviews conducted with the younger generation in Jazirah Leihitu reveal that, due to their current level of digital literacy, accessing digitized manuscript materials is much easier for external parties than for the actual manuscript owners themselves. Furthermore, digitization initiatives do not adequately equip manuscript owners to independently perform maintenance tasks, resulting in a deterioration of both the quantity and physical condition of the manuscripts.

Despite ongoing efforts to preserve manuscripts among the people of Maluku through traditional practices and local knowledge, the lack of advancement in traditional manuscript care knowledge hinders the effective channeling of this preservation spirit. Consequently, manuscript owners often rely on external experts, particularly manuscript researchers, for assistance in caring for and maintaining these manuscripts (primary data).

The findings above highlight that, despite shared goals among various stakeholders, their efforts remain fragmented and unsustainable. This is evident from both qualitative and quantitative degradation observed in the manuscripts, including instances of missing manuscripts, physical damage, and subpar storage conditions in Jazirah Leihitu.

Conversely, preserving and considering the cultural values embedded in each manuscript during digitization efforts is imperative. Therefore, it is crucial to develop approaches that integrate physical manuscript protection with considerations of cultural values in the digitization process. This balanced approach will ensure the preservation of traditional manuscripts’ inherent values and meanings while also enhancing accessibility and understanding of traditional knowledge for present and future generations.

To achieve this, it is essential to ensure that the digitization process does not compromise the essence and significance of traditional manuscripts in their original form. A profound understanding of the cultural context, values, and language depicted in the manuscripts is vital to prevent any dilution of the intended traditional knowledge during the digitization process. Involving cultural experts, researchers, and relevant communities in the digitization process is crucial to safeguard the cultural authenticity and local wisdom embodied in these manuscripts, which have been passed down through generations (Marsh 2023).

To ensure the continuity of traditional knowledge, digitization should be viewed not as the ultimate objective but as a tool that facilitates the preservation and dissemination of such knowledge (Balogun and Kalusopa 2021). Employing physical safeguards for manuscripts and adopting a comprehensive approach to the cultural values embedded within Ambon manuscripts will effectively facilitate the transmission of this traditional knowledge to future generations. Consequently, digitization is a sustainable solution that fosters both the development and preservation of traditional knowledge, bridging the gap between a cherished historical legacy and an increasingly technology-driven future.

The research has identified and addressed the potential and challenges of preserving Ambon manuscripts, culminating in developing a more comprehensive and targeted, integrated preservation model. This model, known as the scaffolding model, offers a holistic framework for preservation endeavors (Figure 5).

Scaffolding model for the preservation of Maluku manuscripts.

This model represents a progression of preventive preservation methodologies grounded in indigenous knowledge (Aghisni, Agustini, and Saefudin 2022). The preventive preservation model utilizes cultural rituals as collaborative platforms for community engagement, stewardship, and government participation. However, in Aghisni’s proposed model, all initiatives remain reliant on governmental funding, thus potentially encountering the perennial challenge of financial constraints. Moreover, the preservation approach heavily relies on traditional methods without incorporating efforts to enhance custodial proficiency in modern manuscript preservation.

The scaffold model devised in this investigation places emotional attachment, relevance, and a fervent commitment to manuscript preservation at the forefront of sustainable conservation efforts. This mirrors the traditional practices prevalent in Maluku, where active community involvement in self-preservation is prominent. Research findings underscore the pivotal role of this aspect in the ongoing conservation of manuscripts in Maluku, predicated on community self-sufficiency.

An additional benefit of this model underscores the importance of knowledge dissemination rather than the availability of funding. Empowering the local community with contemporary preservation techniques offers a more sustainable pathway compared to reliance on international financial aid.

Further advancement entails the expansion of actors engaged in the preservation process. The preventive preservation strategy overlooks the involvement of academia and other educational institutions (such as the Language Agency, Ministry of Religious Affairs Lecturers, Universities, and the National Library) as stakeholders responsible for preserving manuscripts within communities. These four stakeholders, namely 1) the local community, 2) stakeholders (the Maluku provincial government), 3) academia, and 4) users, position themselves as interim supporters until manuscript owners achieve preservation independence.

The term “local community” denotes the inhabitants residing in the vicinity of the manuscript storage area, excluding the manuscript heirs. Their involvement is evident in participating in cultural rituals that incorporate manuscripts, such as the designation of a sermon deliverer or alterations to mosque domes. Within this specific context, the local community assumes the responsibility of transmitting manuscript contents to subsequent generations. While primarily referring to the community residing near the manuscript storage area, this delineation remains flexible. In a broader local context, particularly within Maluku, the term “local community” may encompass communities invested in local manuscripts or local research communities. In a broader scope, the local community may also play a role in advocating for recognition from local government entities or in empowering themselves as indigenous communities.

Stakeholders specifically pertain to local government bodies and other governmental institutions associated with manuscripts, such as the Language Office of Maluku and the Cultural Heritage Preservation Center (BPCB) of Maluku. This cohort contributes through initiatives like exhibitions aimed at fostering appreciation for manuscripts among a wider audience. Cultivating this awareness serves as a strategy for promoting positive attitudes, aided by community socialization, the dissemination of translation findings, or adaptation into alternative formats such as academic publications. Furthermore, as a form of acknowledgment, at minimum, these manuscripts should be cataloged as cultural heritage within the Maluku cultural database.

Academics comprise researchers of ancient manuscripts, whether local, national, or international, conducting studies focusing on Maluku manuscripts. Their specific roles encompass digitization, dissemination, and contextual reinterpretation of manuscripts. Ethically, they bear responsibility for manuscript preservation and knowledge transfer to community stakeholders.

Users refer to entities utilizing Maluku manuscripts for economic or commercial purposes. This category is obliged to recognize these manuscripts as intellectual property belonging to the Maluku community. Hence, they are obligated to share proceeds generated from commercialization endeavors, such as producing batik or souvenirs derived from illuminated Maluku manuscripts, to support maintenance and preservation efforts.

Centralizing the community within this model involves decision-making through a bottom-up approach. This approach delegates final decision-making authority to community stakeholders, facilitating a simpler, more practical, and locally tailored process. Additionally, this model can mitigate social tensions among supporting factions (Verdini, Frassoldati, and Nolf 2017).

The elements in this scaffold model can work as a unified system only if preservation policies fulfill two key elements. The two key elements of this model are the transfer of preservation skills to community owners and the formulation of a code of ethics that ensures each party fulfills its role. These two aspects require awareness from actors (knowledge transfer) and policy instruments (code of ethics).

5.5 Two Key Elements of the Scaffolding Model: Preservation Mentoring and User Ethic

The scaffolding model relies on two critical elements to ensure its efficacy: preservation mentoring practices and user ethics. This study is supplemented by direct mentoring practices for manuscript owners. Activities were conducted in Morela, involving manuscript owners from three other observation areas.

The direct training provided by researchers aims to transfer the necessary knowledge and skills for caring, conserving, and repairing manuscripts. Fundamental principles imparted include tool usage and handling of manuscripts (utilization of gloves, masks, etc.), storage management (grouping, coding), content comprehension skills, and accessing digital manuscript data.

The execution of these activities can aid communities in preserving and conserving manuscripts as part of their invaluable cultural heritage. Furthermore, it can foster awareness of the significance of safeguarding cultural heritage for future generations (Figure 6).

Foundational manuscript preservation mentoring practices.

Collaborative initiatives between the community and researchers are instrumental in fostering awareness and comprehension of the historical and cultural significance encapsulated within manuscripts. This collaboration empowers the community to actively participate in preservation and maintenance endeavors.

The preservation of cultural heritage through community engagement comprises several stages. Firstly, there is a need to enhance community awareness. Secondly, mentoring in fundamental preservation techniques, participatory conservation, and documentation of preservation efforts are essential to introduce proper methods for the care, conservation, and restoration of manuscripts, thereby aiding the community in understanding the historical and cultural values imbued within these manuscripts.

The second crucial aspect is user ethics, which play a pivotal role in the preservation context. The active involvement of communities and manuscript users is essential in upholding the physical integrity and cultural value of these historical artifacts. Formulating these ethics into a code of conduct would enhance their effectiveness in ensuring that each party fulfills its responsibilities.

User ethics in the context of preserving Ambon manuscripts signify a collective dedication to responsibly safeguarding and caring for manuscripts. This entails user behavior that prioritizes the physical protection of manuscripts from potential risks such as environmental damage, rough handling, or improper storage.

By internalizing these ethics, the community and individuals involved in preserving Ambon manuscripts function as custodians who prevent the possibility of physical degradation. The significance of shared responsibility in Ambon manuscript user ethics is also evident in collaborations between the local community and external stakeholders. These ethics facilitate cross-community engagement in preservation efforts, facilitating the exchange of knowledge and best practices. Additionally, understanding user ethics contributes to educating the broader community about the importance of collectively preserving these historical manuscripts.

Furthermore, user ethics play a pivotal role in fostering positive behavior in the use and access to Ambon manuscripts. Through respectful and cautious behavior, these ethics mitigate the risk of damage and misuse. Consequently, user ethics form a robust foundation for maintaining the physical integrity and cultural values embodied in Ambon manuscripts, while also shedding light on the significance of active participation in preserving this invaluable heritage.

6 Conclusions and Recommendations

Field observations have confirmed degradation in both the physical condition and knowledge transmission of Ambon manuscripts following digitization. Additionally, the limited access of future generations to digital materials suggests a deficiency in knowledge transfer from manuscript users.

Various cultural practices indirectly illustrate the historical significance and enduring legacy of manuscript literacy traditions in Ambon. Manuscript literacy holds significant importance as it influences the legitimacy of power within customary law, given that the lineage determines the King and imam (up to the Khatib). Due to its association with religious affairs and proficiency in Arabic script, there is a prevalent tendency among imam/khatib families to educate their children in religious schools, fulfilling their responsibility to uphold this esteemed status.

The presence of ancestral homes as the primary sites for children to learn Arabic script/Quranic recitation, the ceremonial reading of scroll manuscripts as part of the initiation into the imam/khatib status, the determination of the start date of Ramadan based on manuscripts, and the recitation of scroll manuscripts during dome replacement ceremonies all exemplify the pervasive influence of manuscript content within the social fabric of Jazirah Leihitu society. This underscores the manuscripts’ relevance, vitality, and integration into the realities of Maluku society.

The scaffolding model is developed in response to the historical and contemporary conditions of manuscript content preservation in Maluku. Given that structural shifts have initiated cultural transformations within Maluku society, albeit to a limited extent, the amalgamation of past practices and present realities is unavoidable. This model aims to bring together stakeholders involved with manuscripts through an ethical code, establishing them as temporary support structures within a dynamically evolving society. By fostering independent initiatives to enhance manuscript literacy within the community, this model seeks to strengthen the preservation efforts. Regrettably, as of now, there is a lack of an ethical code governing research and manuscript digitization processes to facilitate this endeavor.

Funding source: Badan Riset dan Inovasi Nasional

Award Identifier / Grant number: Rumah Program

Acknowledgment

This work is supported by Rumah Program funded by the Research Organization for Archaeology, Language and Literature, the National Research and Innovation Agency (BRIN).

References

Aghisni, S. S., D. N. Agustini, and E. Saefudin. 2022. “Kegiatan Preservasi Preventif Naskah Kuno Berbasis Kearifan Lokal: Studi Kasus Tentang Preservasi Preventif Naskah Kuno Berbasis Kearifan Lokal di Situs Kabuyutan Ciburuy Kabupaten Garut.” Nautical: Jurnal Ilmiah Multidisiplin 5 (1): 400–7.Search in Google Scholar

Azra, A. 2015. “Genealogy of Indonesian Islamic Education: Roles in the Modernization of Muslim Society.” Heritage of Nusantara: International Journal of Religious Literature and Heritage 4 (1): 85–114. https://doi.org/10.31291/hn.v4i1.63.Search in Google Scholar

Balen, K. V., and A. Vandesande. 2015. Community Involvement in Heritage. Antwerp-Apledoorn: Garant.Search in Google Scholar

Balloffet, N., and J. Hille. 2005. Preservation and Conservation. USA: American Library Association.Search in Google Scholar

Balogun, T. 2023. “Data Management of Digitized Indigenous Knowledge System in Repositories.” Information Development 39 (3): 425–38. https://doi.org/10.1177/02666669231186777.Search in Google Scholar

Balogun, T., and T. Kalusopa. 2021. “A Framework for Digital Preservation of Indigenous Knowledge System (Iks) in Repositories in South Africa.” Records Management Journal 31 (2): 176–96. https://doi.org/10.1108/rmj-12-2020-0042.Search in Google Scholar

Baquee, A., and M. M. Raza. 2020. “Preservation Conservation and Use of Manuscripts in Aligarh Muslim University Library: A Case Study.” Collection Management 45 (3): 273–83. https://doi.org/10.1080/01462679.2019.1679313.Search in Google Scholar

Biela, N., A. Oyelude, and E. Haumba. 2016. “Digital Preservation of Indigenous Knowledge (IK) by Cultural Heritage Institutions: A Comparative Study of Nigeria, South Africa, and Uganda.” In Standing Conference of Easter Central and Southern African Libraries Association (SCESCAL), 351–64. Ezulwini, Swaziland: HSRC research output.Search in Google Scholar

Braginsky, V. 2004. The Heritage of Traditional Malay Literature. A Historical Survey of Genres, Writings and Literary Views. Leiden: KITLV Press.10.1163/9789004489875Search in Google Scholar

Chambert-Loir, H. 2005. “The Sulalat al-Salatin as a Political Myth.” Indonesia 79: 131–60.Search in Google Scholar

Christen, K. 2015. “Tribal Archives, Traditional Knowledge, and Local Contexts: Why the “s” Matters.” Journal of Western Archives 6 (1): 1–19.Search in Google Scholar

Creswell, J. W., and J. D. Creswell. 2018. Research Design Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, 5th ed. Los Angeles: Sage Publications, Inc.Search in Google Scholar

Gallop, A. T. 2020. “Shifting Landscapes: Remapping the Writing Traditions of Islamic Southeast Asia Through Digitisation.” Humaniora 32 (2): 97–109. https://doi.org/10.22146/jh.55487.Search in Google Scholar

Gireesh Kumar, T. K., and R. Raman Nair. 2022. “Conserving Knowledge Heritage: Opportunities and Challenges in Conceptualizing Cultural Heritage Information System (CHIS) in the Indian Context.” Global Knowledge, Memory and Communication 71 (6–7): 564–83. https://doi.org/10.1108/GKMC-02-2021-0020.Search in Google Scholar

Handoko, W. 2015. “Naskah Kuno dan Perkembangan Islam di Maluku Studi Kasus Kerajaan Hitu Maluku Tengah Abad XVI-XIX M.” Berkala Arkeologi 35 (2): 169–82. https://doi.org/10.30883/jba.v35i2.64.Search in Google Scholar

Hassani, F. 2015. “Documentation of Cultural Heritage; Techniques, Potentials, and Constraints.” The International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences 40: 207–14. https://doi.org/10.5194/isprsarchives-xl-5-w7-207-2015.Search in Google Scholar

Khalaf, M. 2016. “Urban Heritage and Vernacular Studies Parallel Evolution and Shared Challengens.” ISVS E-Journal 4 (3): 39–51.Search in Google Scholar

Kramer-Smyth, J. 2019. Partners for Preservation: Advancing Digital Preservation Through Cross-Community Collaboration. London: Facet Publishing.10.29085/9781783303496Search in Google Scholar

Li, J., S. Khrishnamurthy, A. P. Roders, and P. van Wesemael. 2020. “Community Participation in Cultural Heritage Management: A Systematic Literature Review Comparing Chinese and International Practices.” Cities 96: 1–9.10.1016/j.cities.2019.102476Search in Google Scholar

Logan, W.S. 2007. “Closing Pandora’s Box: Human Rights Coundrums in Cultural Heritage.” In Cultural Heritage and Human Rights, edited by H. Silverman, and D. Fairchild Ruggles. New York: Springer.10.1007/978-0-387-71313-7_2Search in Google Scholar

Lone, M. I., A. Wahid, and A. Shakoor. 2021. “Preservation of Rare Documentary Sources in Private Libraries and Religious Institutions.” Global Knowledge, Memory and Communication 70 (8/9): 876–90. https://doi.org/10.1108/gkmc-09-2020-0141.Search in Google Scholar

Mandal, D. J., H. Deborah, and M. Pedersen. 2023. “Subjective Quality Evaluation of Alternative Imaging Techniques for Microfiche Digitization.” Journal of Cultural Heritage 63: 81–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.culher.2023.07.014.Search in Google Scholar

Manernova, O. 2015. “Conservation of Library Collections: Research in Library Collections Conservation and Its Practical Application at the Scientific Library of Tomsk State University.” IFLA Journal 41 (1): 63–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/0340035214561732.Search in Google Scholar

Ma’rifat, D. F. 2014. ““Syair Jawi”: Manuskrip Ambon.” Madah: Jurnal Bahasa Dan Sastra 5 (1): 115–28. https://doi.org/10.31503/madah.v5i1.529.Search in Google Scholar

Marsh, D. E. 2023. “Digital Knowledge Sharing: Perspectives on Use, Impacts, Risks, and Best Practices According to Native American and Indigenous Community-Based Researchers.” Archival Science 23 (1): 81–115. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10502-021-09378-9.Search in Google Scholar

Mekonnen, H., Z. Bires, and K. Berhanu. 2022. “Practices and Challenges of Cultural Heritage Conservation in Historical and Religious Heritage Sites: Evidence from North Shoa Zone, Amhara Region, Ethiopia.” Heritage Science 10 (1): 172. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-022-00802-6.Search in Google Scholar

Montenegro, M. 2023. “Bridging Histories Through Intercultural Archiving.” Public History Weekly 11 (2). https://doi.org/10.1515/phw-2023-21185.Search in Google Scholar

Oinam, A. C., and P. Thoidingjam. 2019. “Manuscript Preservation and Conservation for Future Generation.” KIIT Journal of Library and Information Management 6 (1): 91–6. https://doi.org/10.5958/2455-8060.2019.00013.2.Search in Google Scholar

Onciul, B., et al.. 2017. “Introduction: Engaging Heritage, Engaging Communities.” B. Onciul, M. L. Stefano, and S. K. Hawke. Woodbridge: Boydell Press.10.1515/9781782049128Search in Google Scholar

Rios, F., M. Lassere, J. E. Ruggill, and K. S. McAllister. 2020. “Sustaining Software Preservation Efforts Through Use and Communities of Practice.” International Journal of Digital Curation 15 (1): 7. https://doi.org/10.2218/ijdc.v15i1.696.Search in Google Scholar

Saptouw, F. 2020. “An Analysis of the Strategies Employed to Curate, Conserve and Digitize the Timbuktu Manuscripts.” International Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences 14 (10): 916–21.Search in Google Scholar

Trillo, C., R. Aburamadan, S. Mubaideen, D. Salameen, and B. C. N. Makore. 2020. “Towards a Systematic Approach to Digital Technologies for Heritage Conservation. Insights from Jordan.” Preservation, Digital Technology & Culture 49 (4): 121–38. https://doi.org/10.1515/Pdtc-2020-0023.Search in Google Scholar

UNESCO. 2016. Culture: Urban Future: Global Report on Culture for Sustainable Urban Development. Paris: UNESCO Publishing.Search in Google Scholar

UNESCO Institute for Statistics. 2009. UNESCO Framework for Cultural Statistics. Paris: UNESCO Publishing.Search in Google Scholar

Verdini, G., F. Frassoldati, and C. Nolf. 2017. “Reframing China’s Heritage Conservation Discourse: Learning by Testing Civic Engagement Tools in a Historic Rural Village.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 23 (4): 317–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2016.1269358.Search in Google Scholar

Wijesuriya, G., J. Thompson, and S. Court. 2017. “People-Centered Approaches: Engaging Communities and Developing Capacities for Managing Heritage.” In Heritage, Conservation, and Communities Engagement, Participation, and Capacity Building, edited by G. Chitty, 54–69. Abingdon: Routledge.10.4324/9781315586663-13Search in Google Scholar

Yahia, K. B., and F. Bouslama. 2023. “Reflections on the Preservation of Tunisian Cultural Heritage in a Post-Crisis Context: Between Digitalization and Innovative Promotional Techniques.” Preservation, Digital Technology & Culture 52 (1): 17–29. https://doi.org/10.1515/Pdtc-2022-0028.Search in Google Scholar

Yu, L. 2023. “Digital Sustainability of Intangible Cultural Heritage: The Example of the ‘Wu Leno’ Weaving Technique in Suzhou, China.” Sustainability (Switzerland) 15 (12). https://doi.org/10.3390/su15129803.Search in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- From the Editor

- Articles

- A Digital Preservation for the Indonesian First Terminus

- Preserving the Past, Enabling the Future: Assessing the European Policy on Access to Archives in the Digital Age

- Enhancing Participatory Design Through Blockchain

- Methods of Modelling Electronic Academic Libraries: Technological Concept of Electronic Libraries

- Preservation as a Shared Responsibility: Collaboration for the Sustainable Preservation of Ambon Manuscripts

- News and Comments

- Declaration on the Protection of Archives, Libraries, Museums and Heritage Places During Armed Conflicts and Political Instability

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- From the Editor

- Articles

- A Digital Preservation for the Indonesian First Terminus

- Preserving the Past, Enabling the Future: Assessing the European Policy on Access to Archives in the Digital Age

- Enhancing Participatory Design Through Blockchain

- Methods of Modelling Electronic Academic Libraries: Technological Concept of Electronic Libraries

- Preservation as a Shared Responsibility: Collaboration for the Sustainable Preservation of Ambon Manuscripts

- News and Comments

- Declaration on the Protection of Archives, Libraries, Museums and Heritage Places During Armed Conflicts and Political Instability