Abstract

The macromolecular complexes of random, regular, graft, block and dendritic polyampholytes with respect to transition metal ions, surfactants, dyes, polyelectrolytes, and proteins are discussed in this review. Application aspects of macromolecular complexes of polyampholytes in biotechnology, medicine, nanotechnology, catalysis are demonstrated.

Introduction

Macromolecular complexes of polyampholytes (MCP) represent the products of complexation of linear and crosslinked synthetic polyampholytes, possessing random, regular, graft, block and dendritic microstructures, with polyelectrolytes, proteins, metal ions, surfactants, dyes, drugs, and nanoparticles [1], [2], [3], [4], [5], [6]. Synthetic polyampholytes that are involved into complexation reactions can be classified as “annealed”, “quenched”, “betaine”, and/or “zwitterionic” types [1], [7], [8], [9], [10]. From theoretical point of view, both polyampholytes and MCP are interesting for understanding the protein folding mechanism, molecular simulation study of polyampholyte-protein complexes, enzymatic properties of protein-metal complexes, function of biological tissues, membranes etc. [11], [12], [13]. From practical point of view, the fundamental findings of MCP can be utilized in the field of bio- and nanotechnology, medicine, catalysis, hydrometallurgy, oil industry and environment protection [14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21]. This review is organized in the following manner. The first subchapter is devoted to the complexation between polyampholytes themselves. The second subchapter considers polyampholyte-protein complexes. Complexes of polyampholytes with polyelectrolytes are described in the third subchapter. Subchapter 4 combines the complexes of polyampholytes with metal ions, surfactants, dyes, and metal nanoparticles. Application aspects of MCP are considered as separate subchapter. The perspectives and open problems of MCP are outlined in the concluding part.

Polyampholyte–polyampholyte complexes

To the best of our knowledge, the complexation between polyampholytes themselves is an insufficiently studied topic. Polyampholyte–polyampholyte complexation was first mentioned for a random copolymer composed of acrylic acid (AA), N,N′-dimethylaminoethylmethacrylate (DMAEM) and methyl methacrylate (MMA) [22]. Self-aggregation of AA-DMAEM-MMA was evaluated turbidimetrically as a function of pH and polymer concentration. An increase in the turbidity near of the isoelectric point (IEP) of polyampholyte (pHIEP≈6.4) was related to polyampholyte–polyampholyte interaction (self-assembling). However, authors dealt with intramolecular complexation of polyampholyte chains rather than intermacromolecular complexation. It seems that in aqueous solution intramolecular complexes of polyampholytes become more hydrophobic and further aggregated into larger colloidal particles and precipitate.

Formation of intramolecular complexes of polyampholytes within a single chain of polyampholytes is mostly pronounced for linear block polyampholytes (LBPA) [23], [24], [25], [26]. For instance, the insolubility of equimolar LBPA at the IEP is due to cooperative interactions between the anionic and cationic blocks.

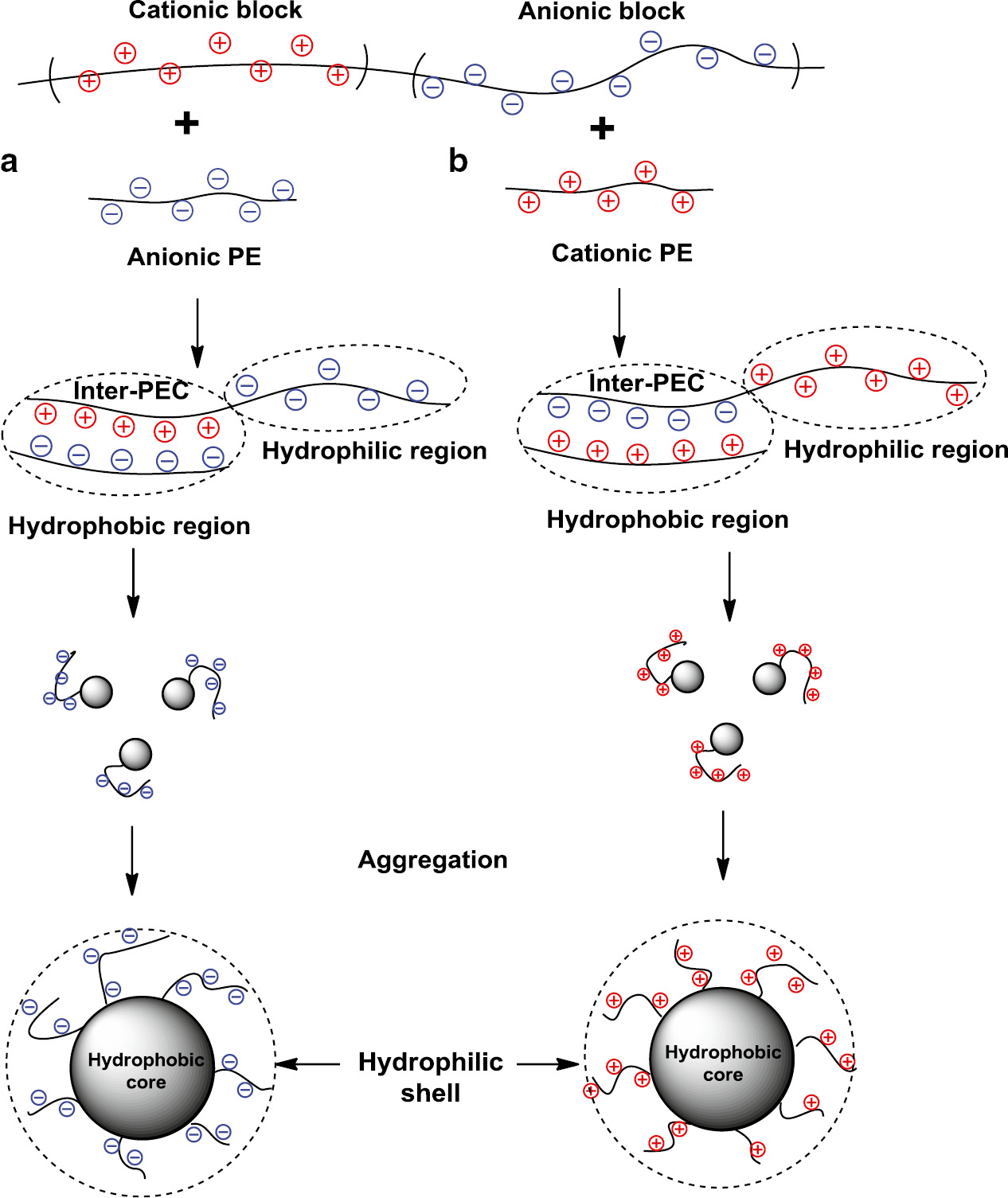

It is expected that LBPA containing polyampholyte block and the excess of either anionic or cationic blocks are able to form interpolyelectolyte complexes (Inter-PEC) [27]. The specific feature of diblock quenched polyampholytes composed of sodium salt of 2-acrylamide-2-methylpropanesulfonate (AMPS) and 3-acrylamidopropyltrimethylammonium chloride (APTAC) is that the “core” of such copolymers composed of cationic and anionic monomers represents the polyampholyte regime and forms intra-polyelectrolyte complexes (Intra-PEC) while the “shell” part bearing the excess of either positive or negative charges represents the polyelectrolyte regime. Due to the presence of anionic and cationic blocks on the surface of Intra-PEC they are able to form polyampholyte–polyampholyte complexes. Authors [27] studied the complexation reaction between a pair of anionic diblock (AMPS-APTAC)91-(AMPS)67 (denoted as P(SA)91S67) and cationic diblock (AMPS-APTAC)91-(APTAC)88 (denoted as P(SA)91A88) copolymers (Fig. 1). They were involved into complexation reaction to form stoichiometric polyion complex (PIC) micelles.

![Fig. 1:

Anionic diblock P(SA)91S67 and cationic diblock P(SA)91A88 copolymers (a) and formation of PIC micelle (b). Redrawn from Ref. [27] with permission from MDPI.](/document/doi/10.1515/pac-2019-1104/asset/graphic/j_pac-2019-1104_fig_001.jpg)

Anionic diblock P(SA)91S67 and cationic diblock P(SA)91A88 copolymers (a) and formation of PIC micelle (b). Redrawn from Ref. [27] with permission from MDPI.

The Rh values for P(SA)91S67 and diblock P(SA)91A88 in 0.1 M NaCl were equal to 5.7 and 6.0 nm. The Rh for the PIC micelle increased to 29.0 nm suggesting that PIC micelle is spherical and consists of core-shell structure where the anionic PAMPS and cationic PAPTAC blocks represent a core, and amphoteric parts P(SA)91 form the shell. As revealed from ζ-potential and TEM measurements the ζ-potential of PIC micelle was close to zero, the average radius of dried PIC was equal to 20.3 nm.

Mixing of poly[2-(methacryloyloxy)ethyl phosphorylcholine]-block-poly[3-(methacrylamido)propyltrimethylammonium chloride] (PMPC20-b-PMAPTAC190) and poly[2-(methacryloyloxy)ethyl phosphorylcholine]-block-poly[sodium 2-acrylamido-2-methylpropanesulfonate] (PMPC20-b-PAMPS196) leads to the spontaneous formation of core-shell PIC vesicles composed of PIC core and PMPC shells [28] (Fig. 2). The PIC vesicles were characterized by NMR, static and dynamic light scattering, TEM, AFM and ζ-potential. The aqueous solution of PMPC20-b-PAMPS196 has a negative ζ-potential value of −29 mV due to the PAMPS block that has pendant anionic sulfonate groups, while the aqueous solution of PMPC20-b-PMAPTAC190 has a positive ζ-potential value of +27 mV because the PMAPTAC block has pendant cationic quaternary amino groups. For equimolar mixture of PMPC20-b-PAMPS196 and PMPC20-b-PMAPTAC190 the ζ-potential was zero because the negative and positive charges of the PAMPS196 and PMAPTAC190 blocks are mutually compensated.

![Fig. 2:

(a) Chemical structures of poly[2-(methacryloyloxy)ethyl phosphorylcholine]-block-poly[3-(methacrylamido)propyltrimethylammonium chloride] (PMPC20-b-PMAPTAC190) and poly[2-(methacryloyloxy)ethyl phosphorylcholine]-block-poly[sodium 2-acrylamido-2-methylpropanesulfonate] (PMPC20-b-PAMPS196). (b) Conceptual illustration of PIC vesicle formation with spherical hollow structure according to TEM image. Redrawn and compiled from Ref. [28] with permission from MDPI.](/document/doi/10.1515/pac-2019-1104/asset/graphic/j_pac-2019-1104_fig_002.jpg)

(a) Chemical structures of poly[2-(methacryloyloxy)ethyl phosphorylcholine]-block-poly[3-(methacrylamido)propyltrimethylammonium chloride] (PMPC20-b-PMAPTAC190) and poly[2-(methacryloyloxy)ethyl phosphorylcholine]-block-poly[sodium 2-acrylamido-2-methylpropanesulfonate] (PMPC20-b-PAMPS196). (b) Conceptual illustration of PIC vesicle formation with spherical hollow structure according to TEM image. Redrawn and compiled from Ref. [28] with permission from MDPI.

The hydrodynamic radius (Rh) and aggregation number (Nagg) of PIC vesicles in 0.1 M NaCl was equal to 78.0 nm and 7770, respectively. Since the PIC vesicles contain a spherical hollow cavity (TEM image in Fig. 2b) covered by biocompatible PMPC shell, they may be useful for immobilization of bioactive compounds and controlled delivery to appropriate targets.

Polyampholyte-protein and polyampholyte-DNA complexes

As distinct from polyampholyte-protein complexes, complexes of polyelectrolytes with proteins have recently been reviewed by many authors [29], [30], [31], [32], [33]. The polyampholyte-protein and polyampholyte-DNA systems surveyed from literature sources are summarized in Table 1.

Complexes of synthetic polyampholytes with proteins and DNA.

| No | Polyampholyte | Protein or DNA | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Acrylic acid – co – N,N′-dimethylaminoethylmethacrylate – co – methyl methacrylate (AA-co-DMAEM-co-MMA) | Soybean trypsin inhibitor | [22] |

|

Ribonuclease A | ||

| 2 | Magnetite nanoparticles (MNP) coated by poly[(acrylic acid-co-3-(diethylamino)propylamine] | BSA | [34] |

|

Lysozyme | ||

| 3 | Carboxymethylated poly(L-histidine) and poly(1-vinylimidazole) | Fetal bovine serum | [35], [36] |

|

DNA | ||

|

|||

| 4 | Carboxymethylated poly(4-vinylpyridine) | DNA | [37] |

|

|||

| 5 | 2,5-dimethyl-4-vinylethynylpiperidinol-4-co-acrylic acid (DMVEP-co-AA) | BSA | [38] |

|

|||

| 6 | 3-sulfopropyl methacrylate–co–[2-(methacryloyloxy)ethyl]trimethylammonium chloride [poly(SA-co-TMA)] | Blood plasma | [39] |

|

(Human fibrinogen) | ||

| 4 | Polyethyleneimine-based polyampholyte | Plasmid DNA | [40] |

|

|||

| 7 | Succinylatedε-poly-L-lysine | Lysozyme | [41], [42] |

|

|||

| 8 | Polyethyleneglycol (PEG) containing amino- (A) and carboxylic (C) groups (PEG-AC) | DNA | [43] |

|

|||

| 9 | Poly(ethyleneglycoldiglycidyl ether-methacrylic acid-methylimidazole) Poly(EGDE-MAA-2MI) | BSA | [44] |

|

The method of protein separation by water-soluble polyampholytes is selective complexation of polyampholyte with one of the proteins, which has predominantly positive or negative charge [45], [46], [47], [48]. Upon addition of polyampholyte to mixture of proteins, some protein forms a complex with the polyampholyte, as the other remain in the supernatant phase [47]. The precipitated protein-polyampholyte complex may be isolated from the system and then redissolved at a different pH or else can be destroyed at the IEP, where the full precipitation of polyampholyte itself takes place [48]. Polyampholyte hydrogels and cryogels effectively adsorb proteins by two ways. The first approach is adsorption of proteins by preliminary prepared networks and the second one is imprinting of proteins within the network in situ polymerization conditions. Binding of proteins by polyampholyte networks has the electrostatic nature and takes place between their isoionic point (IIP) and isoelectric point (IEP) [49]. A macroporous amphoteric polymers based on N,N-dimethylaminoethylmethacrylate and methacrylic acid [50], N-[3-(dimethylamino)propyl]methacrylate and MAA [51] and N,N-dimethylaminopropylacrylamide and AA [52] were used as a template, adsorbents and carriers with respect to bovine serum albumin (BSA) and lysozyme.

Polyampholyte-polyelectrolyte complexes

Authors [53], [54] developed molecular dynamics simulations for evaluation of polyampholyte-polyelectrolyte complexation. The structure of polyelectrolyte-polyampholyte complexes revealed that random polyampholyte forms with polyelectrolyte the micellar aggregate while diblock polyampholyte with polyelectrolyte forms branch polymer-like aggregate. Molecular simulation study proved that the stability of complexes of polyampholytes is arranged in the following order: block polyampholyte-polyelectrolyte>statistical polyampholyte-polyelectrolyte>alternating polyampholyte-polyelectrolyte. The pH-dependent behavior of isolated polyampholytes and polyampholyte-polyelectrolyte complexes in dilute solutions was studied by Monte Carlo simulations [55]. The polyelectrolyte-polyampholyte system showed the stability below the IEP at pH≤6.5 and the complex dissociated above the IEP. This theoretical finding was confirmed by the existence of the “isoelectric effect” that is specific at the IEP of polyampholytes [5].

Kabanov and co-workers [56], [57], [58], [59] studied for the first time the interaction of random and dendritic polyampholytes with linear and crosslinked polyelectrolytes. Formation of Inter-PEC between cellulose-based poly(zwitterion) and poly(N,N-dimethyl-N,N-diallylammonium chloride) (PDMDAAC) is described in [60]. A series of copolymers based on N-methyldiallylamine-maleic acid, N,N-dimethyldiallylammonium and alkyl (or aryl) derivatives of maleamic acids were involved into the complexation with PDMDAAC, poly(acrylic acid) (PAA), and poly(styrene sodium sulfonate) (NaPSS) [61], [62], [63], [64]. The stoichiometry of polyampholyte-polyelectrolyte complexes was found. The LBPA binds the anionic and cationic polyelectrolytes more effectively in comparison with statistical and alternating polyampholytes [65], [66] (Fig. 3). The nucleus of LBPA-polyelectrolyte complex consists of Inter-PEC that is represented as hydrophobic region (or core) surrounded by anionic (or cationic) block (shell) that is responsible for the preservation of Inter-PEC particles in water-soluble state.

Schematic representation of LBPA complexes with anionic (a) and cationic (b) polyelectrolytes.

Layer-by-layer (LbL) complexation of rigid polyampholyte – sulfonatedcardopoly(arylen ether sulfone) (SPES) – with anionic NaPSS and cationic PDMDAAC polyelectrolytes was studied by authors [67]. The remarkable behavior of polyampholytes to change the net charge from positive to negative was realized by authors [68] to obtain pH-sensitive LbL films with an amphoteric copolymer, i.e. poly(diallylamine-co-maleic acid) (PDAMA). Using PDAMA as a component the free-standing LbL films in combination with the NaPSS or the PDMDAAC were fabricated [69].

The complexation of polycarbobetaines with NaPSS, DNA and poly(zwitterion) – poly[3-dimethyl(methacryloyloxyethyl ammonium propane sulfonate)] (PDMCPS) with polymeric anion: poly(2-acrylamido-2-methyl propane sulfonic acid) (PAMPS) or polymeric cations: poly(3-acrylamidopropyltrimethyl ammonium chloride) (PDMCPAA-Q) and x,y-ionene bromides (x=3, 6; y=3, 4) was studied [70] to evaluate the UCST of PDMCPS. It was found that in case of PDMCPS-PAMPS an ammonium cation in the middle interacts with sulfonate anion of PAMPS (Fig. 4a). Inter-PEC consisting of PDMCPAA-Q and PDMCPS is soluble because the sulfonates located at the end of side chain are responsible for the solubility (Fig. 4b).

![Fig. 4:

Scheme of formation of polybetaine-polyelectrolyte complexes between PDMCPS and PAMPS (a), PDMCPAA-Q (b) and x,y-ionene bromides (c). (Reprinted from Ref. [70]).](/document/doi/10.1515/pac-2019-1104/asset/graphic/j_pac-2019-1104_fig_004.jpg)

Scheme of formation of polybetaine-polyelectrolyte complexes between PDMCPS and PAMPS (a), PDMCPAA-Q (b) and x,y-ionene bromides (c). (Reprinted from Ref. [70]).

The specific feature of polyampholyte-polyelectrolyte complexes is that long polyelectrolyte chains bind only oppositely charged repeating units of polyampholytes, the unbond fragments of polyampholytes in the form of charged loops and tails are responsible for water solubility.

Complexes of polyampholytes with low-molecular-weight substances

Polyampholyte-metal complexes

Metal complexes of polyampholytes are useful to model the complexation of proteins with metal ions, to model the active sites of enzymes as cofactors, to produce metal nanoparticles by reduction of metal ions coordinated (or complexed) with polymeric ligands. Complexation of “annealed” polyampholytes with transition metal ions can proceed via ionic, coordination or ion-coordination bonds. The following structure of polyampholyte-copper complex is suggested for vinyl-2-aminoethyl ether-methacrylic acid/copper(II) complex where electron donor ligands N and O form a stable five-membered ring in inner coordination sphere while carboxylic and chloride anions are replaced in outer coordination sphere preserving the whole electroneutrality of macromolecular chain [71] (Fig. 5).

Ion-coordination complex of Cu2+ with amphoteric copolymer vinyl-2-aminoethyl ether-methacrylic acid.

Mouton and co-workers [72], [73], [74] comprehensively studied the complexation of water-soluble polycarbobetaines (PCB) with copper(II) ions as a function of temperature, pH, and initial adsorbate concentration. In dependence of pH and initial copper(II) concentration removal of metal ions reached up to 97%. Modification of PCB by ethanolamine and glycine leads to formation of mixed 5- and 6-memebered chelate complexes (Fig. 6). The PCB was reused 5 times without the loss of adsorption capacity (99%).

Chelate complexes of PCB (1) and PCB modified by ethanolamine (2) and glycine (3) with copper (II) ions.

Linear and crosslinked polyampholytes made of 2-(1-imidazolyl)ethylmethacrylate and methacrylic acid abbreviated as poly(ImEMA-co-MAA) and methacrylic acid, ethyleneglycoldiglycidil ether (EGDE) and 2-methylimidazole (2MI) abbreviated as poly(EGDE-MAA-2MI) [75] were tested for removal of Pb2+ and Cd2+ ions from aqueous solution.

As distinct from linear analogs, interaction of copper ions with amphoteric hydrogels is accompanied by gradually coloring and shrinking of sample [76] (Fig. 7). The thin colored shell layer which is formed on the hydrogel surface gradually moves into the gel interior. The driving force of this process is “ion-hopping transportation” of metal ions through intra- and intermolecular complex formation, e.g. continuous migration of metal ions deeply into the gel interior by exchanging of free ligand vacancies [77]. Desorption of copper(II) ions from the gel interior by 0.1 M HCl starts from the surface due to destruction of ligand-metal complexes and leaching out of metal ions to outer solution. Periodic washing out of gel specimen by distilled water leads to its full regeneration.

![Fig. 7:

Initial state of hydrogel (1), sorption of copper(II) ions during 10 (2), 40 (3) and 120 (4) min and desorption of copper(II) ions by 0,1N HCl during 3 (5), 15 (6) and 60 (7) min. The regenerated hydrogel (8). (Reprinted from Ref. [76]).](/document/doi/10.1515/pac-2019-1104/asset/graphic/j_pac-2019-1104_fig_007.jpg)

Initial state of hydrogel (1), sorption of copper(II) ions during 10 (2), 40 (3) and 120 (4) min and desorption of copper(II) ions by 0,1N HCl during 3 (5), 15 (6) and 60 (7) min. The regenerated hydrogel (8). (Reprinted from Ref. [76]).

Polyampholyte cryogels may be more practically beneficial due to macroporous structure and presence of acid-base (or anionic-cationic) groups that are able to bind both transition metal ions and complex anions (or cations), such as [Au(CN)2]−, [PtCl6]4− or [UO2(SO4)2]2+. Due to the presence of acid-base groups polyampholyte cryogels are able to bind transition metal ions by ionic and coordinaion bonds [78]. Amphoteric cryogels can adsorb up to 99.9% of metal ions but release only 51–67% of metal ions.

Stabilization of gold nanoparticles by polyampholytes

Acid-base groups of polyampholytes composed of N,N′-diallyl-N,N′-dimethylammonium chloride (DADMAC) and 3,5-bis(carboxyphenyl)maleamic carboxylate (BCPMAC) participated in reduction of [AuCl4] − ions to produce anisotropic gold nanoplatelets stabilized by macromolecular chains [79] (Fig. 8). Regular polyampholyte, namely poly-(N,N′-diallyl-N,N′-dimethylammonium-alt-N-octylmaleamic carboxylate) is proved to be an efficient reducing and stabilizing agent for the formation of gold colloids [80]. Water-soluble and durable Au nanoclusters, smaller than 4 nm with a narrow size distribution, were deposited on a pH- and solvent-responsive water-soluble polyampholyte – the sulfonated cardopoly(arylene ether sulfonate) (SPES) containing 1 amine and 2 sulfonate groups [81]. The Au@SPES hybrids possessed clear pH- and solvent-sensitive properties, and exhibited precipitation behaviors in response to pH and solvent changes in aqueous solution.

![Fig. 8:

TEM images of gold nanoparticles synthesized in the presence of dioctyl sodium sulfosuccinate and DADMAC-BCPMAC polyampholyte at 70°C (a) with a higher magnification of the edge-to-edge junctions (b). Reprinted from Ref. [79].](/document/doi/10.1515/pac-2019-1104/asset/graphic/j_pac-2019-1104_fig_008.jpg)

TEM images of gold nanoparticles synthesized in the presence of dioctyl sodium sulfosuccinate and DADMAC-BCPMAC polyampholyte at 70°C (a) with a higher magnification of the edge-to-edge junctions (b). Reprinted from Ref. [79].

Several diblock polyampholytes, in particular poly(methacrylic acid)-block-poly(N,N-dimethylaminoethyl methacrylate), PMAA-b-PDMAEMA having different molecular weight and block ratio were used for stabilization of AuNPs [82]. The fabrication of gold nanoparticles was realized in DMF and THF. The type of solvent has an impact on the particle size of the gold nanoparticles. The average sizes and plasmon resonance spectra of AuNPs stabilized by various polyampholytes are shown in Table 2 [83].

The sizes and plasmon resonance absorbances of polyampholyte-protected AuNPs.

| Polyampholytes | The average size, nm | The maximum absorbance, λ 𝜆max |

|---|---|---|

| Poly(N,N-dimethylaminoethyl methacrylate-methacrylic acid) | 17 | 540 |

| Poly(vinylbenzyldimethylammonium acetate) | 20 | 550 |

| Poly(vinylbenzyldiethylammonium acetate) | 4–44 | 550 |

| Poly(N,N-dimethyl-N,N-diallylammonium-alt-N-phenylmaleamic acid) | 22 | 530 |

| Poly(N,N-dimethyl-N,N-diallylammonium-alt-N-4-butylphenylmaleamic acid) | 11 | 540 |

Physicochemical, complexation and catalytic properties of polyampholytecryogelswere reviewed in [84], [85]. Metal nanoparticles immobilized within macroporous amphoteric cryogels were used as flow-through catalytic system for reduction of 4-nitrophenol and p-nitrobenzoic acid to corresponding amine derivatives [86], [87], [88], [89].

Polyampholyte-surfactant complexes

Similar to the interaction of homopolyelectrolytes with surfactants [90] cationic detergents form cooperative complexes with acidic groups of polyampholytes, and anionic ones – with their basic groups. Interaction of statistical copolymer of 1,2,5-trimethyl-4-vinylethynylpiperidinol-4 and acrylic acid (TMVEP-AA) and regular copolymer of styrene and N,N-dimethylaminopropylmonoamide of maleic acid (St-DMAPMAMA) with sodium dodecylsulfate (SDS) and cetyltrimethylammonium chloride (CTMA) leads to formation of compact particles stabilized by hydrophobic contacts of the long alkyl chain of detergents [91], [92]. Alternating polyampholytes synthesized by copolymerization of N,N′-diallyl-N,N′-dimethylammonium chloride and maleamic acid (phenylmaleamic acid, 4-butylphenylmaleamic acid) complexed with fatty acids (dodecanoic acid and perfluorododecanoic acid) and formed polyampholyte-coated micelles [93] (Fig. 9).

![Fig. 9:

Complexation of alternating polyampholytes with dodecanoic and perfluorododecanoic acids. Redrawn from Ref. [93].](/document/doi/10.1515/pac-2019-1104/asset/graphic/j_pac-2019-1104_fig_009.jpg)

Complexation of alternating polyampholytes with dodecanoic and perfluorododecanoic acids. Redrawn from Ref. [93].

It is proposed that binding of dodecanoate at first leads to formation of loose aggregates, which reorganize to micelles with a core of alkyl chains of surfactants and shell of carboxylates. The size of self-assembled polyampholyte-wrapped micelles is in the range of 3–5 nm.

Solubilization/precipitation behavior of polyampholyte-surfactant complexes formed between 2-(methacryloyloxy)ethyltrimethylammonium chloride (MADQUAT) and sodium salt of 2-acrylamido-2-methylpropanesulfonate (AMPS) (quenched polyampholytes) and charged surfactants was studied by authors [94].The survey of applied polyampholytes and surfactants is given in Table 3.

Quenched polyampholytes based on acrylamide (AAm), AMPS, MADQUAT and type of used surfactants.

| Polyampholyte | AAm, mol.% | AMPS, mol.% | MADQUAT, mol.% | Surfactanta |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 80/12/08 | 80 | 12 | 8 | CTAB, SDS |

| 80/08/12 | 80 | 8 | 12 | TTAB |

| 80/20 | – | 80 | 20 | TTAB |

| 50/50 | – | 50 | 50 | TTAB, SDS |

-

aCTAB is cetyltrimethylammonium bromide, SDS is sodium dodecylsulfate, TTAB is tetradecyltrimethylammonium bromide.

Polyampholytes with excess of anionic or cationic groups swell in water and are solubilized in the presence of cationic and anionic surfactants above a particular surfactant concentration that is proportional to the polymer concentration. The surfactant binding ability of fully charged polyampholytes, such as 80/20 and 50/50, differs from the partially charged polyampholyte. The polyampholyte 80/20 is soluble in water due to the excess of anionic monomers and shows polyelectrolyte character, while equimolar polyampholyte 50/50 is insoluble in water because of strong electrostatic attraction between oppositely charged monomers leading to chain collapse and precipitation. The interactions of the 80/20 and 50/50 polyampholytes with surfactants are different. The polyampholyte with excess of AMPS (80/20) precipitates in the presence of TTAB, whereas equimolar polyampholytes AMPS-MADQUAT (50/50) dissolves upon addition of SDS. After the precipitation of 80/20-TTAB complexes, these complexes resolubilize at increased concentration of TTAB.

The complexation of charge unbalanced AMPS25-co-APTAC75 and AMPS75-co-APTAC25 copolymers of linear and crosslinked structure with respect to surfactants was studied in aqueous solution [95]. Complexation of linear AMPS25-co-APTAC75 with anionic surfactant – sodium dodecylbenzenesulfonate (SDBS) and AMPS75-co-APTAC25 with cationic surfactant – cetyltrimethyl ammonium chloride (CTMAC) is accompanied by changes in turbidity, ζ-potential and average hydrodynamic diameter of colloid particles. The optimal molar ratios of polyampholyte-surfactant complexes found from the extremums of curves are equal to [AMPS25-co-APTAC75]:[SDBS]≈3:2 mol/mol and [AMPS75-co-APTAC25]:[CTMACl]≈2:3 mol/mol (Figs. 10 and 11).

![Fig. 10:

Changes in ζ-potential (1), average hydrodynamic diameter (2) and turbidity (3) of [AMPS25-co-APTAC75]/[SDBS] with the molar ratio of interacting components. (Reprinted with permission from Ref. [95]).](/document/doi/10.1515/pac-2019-1104/asset/graphic/j_pac-2019-1104_fig_010.jpg)

Changes in ζ-potential (1), average hydrodynamic diameter (2) and turbidity (3) of [AMPS25-co-APTAC75]/[SDBS] with the molar ratio of interacting components. (Reprinted with permission from Ref. [95]).

![Fig. 11:

Changes in ζ-potential (1), average hydrodynamic diameter (2) and turbidity (3) of [AMPS75-co-APTAC25]/[CTMAC] with the molar ratio of interacting components. (Reprinted with permission from Ref. [95]).](/document/doi/10.1515/pac-2019-1104/asset/graphic/j_pac-2019-1104_fig_011.jpg)

Changes in ζ-potential (1), average hydrodynamic diameter (2) and turbidity (3) of [AMPS75-co-APTAC25]/[CTMAC] with the molar ratio of interacting components. (Reprinted with permission from Ref. [95]).

It is obvious that SDBS binds the positively charged APTAC while CTMAC – the negatively charged AMPS. In both cases the surfactant molecules form intramolecular micelle structures surrounded by negatively or positively charged monomers.

Complexation of polyampholyte hydrogels containing an excess of negative (AMPS-75H) and positive (AMPS-25H) charges with CTMA and SDBS is accompanied by gradual shrinking of samples because the cationic and anionic surfactants interact with excessive anionic and cationic groups of hydrogels. Gradual penetration of surfactant molecules inside hydrogel volume can lead to formation of micelles within hydrogel matrix and hydrophobization of the whole system and overall shrinking of hydrogel volume. It is expected that analogous mechanism takes place in case of anionic hydrogel (AMPS-75H) and cationic surfactant (CTMAC). The driving force of formation of AMPS-25H/SDBS (or AMPS-75H/CTMAC) complexes is electrostatic binding of surfactants by excessive positive or negative charges of polyampholytes.

Linear blockpolyampholyte (LBPA) with the excess of cationic block [(PMAA)36-b-(P1M4VPCl)64] forms two types of complexes with SDS: [(PMAA)36-b-(P1M4VPCl)64]/[SDS]=2:1 and 1:1 [96]. The formation of [(PMAA)36-b-(P1M4VPCl)64]/[DDSNa]=2:1 can be accounted for the interaction of SDS with the excess of cationic block not involved into intramolecular complexation. The formation of stoichiometric complex is due to the destruction of cooperative ionic contacts between acidic and basic blocks and their replacement by a new cooperative ionic contacts between LBPA and the surfactant. For the system consisting of [(PMAA)36-b-(P1M4VPCl)64] and CTMAC only the formation of [(PMAA)36-b-(P1M4VPCl)64]/[CTMACl]=2:1 is observed. In this case cationic groups of surfactant can not compete with cationic groups of blockpolyampholyte and interacts only with the carboxylic groups placed on the “loops”.

Polysulfobetaine-surfactant complexes, namely poly(sulfobetaine methacrylate)-SDS and (PSBMA-SDS) and poly(sulfobetaine methacrylate)-cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (PSBMA-CTAB) significantly influence the UCST of pristine PSBMA [97]. Binding of SDS to PSBMA prevents the appearance of UCST while CTAB shifts the cloud point temperature of PSBMA to higher temperature resulting in precipitation of the aggregates from the solution. The hydrophobic domains of PSBMA-SDS complexes were used for stabilization of fluorescent molecules (1-anilino-8-naphthalenesulfonate, pyrene and curcumin) that could be useful for detection of trace amounts of aromatic pollutants in aqueous systems.

Polyampholyte-dye complexes

Polyampholyte hydrogels containing an excess of negative (AMPS-75H) and positive (AMPS-25H) charges effectively absorb methylene blue (MB) and methyl orange (MO), respectively, due to electrostatic binding [95]. No binding of MB is observed for AMPS-25H and AMPS-50H. The reason is that both AMPS-25H and MB are positively charged. In case of AMPS-50H the oppositely charged chains compensate each other and both MB and MO molecules are not able to penetrate into hydrogel matrix. The same phenomenon is observed for AMPS-75H and AMPS-50H with respect to negatively charged MO molecules. AMPS-75H hydrogel containing an excess of negative charges and AMPS-25H containing an excess of positive charges effectively absorb up to 80–90% of negatively charged MB and positively charged MO molecules. Release of dye molecules from hydrogel matrix was performed in 0.5 M KCl medium. The driving force of dye release from the hydrogel matrix is a replacement of electrostatically bound dye by low-molecular-weight salt. The amount of released dye molecules over 1 day is 70–75%.

Quenched polyampholyte composed of NaPSS and vinylbenzyltrimethylammonium chloride (VBTMAC) demonstrated repeatedly absorption-desorption behavior of bisphenol A in dependence of temperature [98]. The NaPSS-VBTMAC absorbs bisphenol A at room temperature and release it at higher temperature that is very important for removal of hydrophobic aromatic compounds from very dilute aqueous solutions. Polyampholyte-surfactant complex was applied for extraction of bisphenol A [99]. Two mechanisms of bisphenol A adsorption by complexes of polyampholyte based on methacrylic acid, ethylene glycol diglycidyl ether and 2-methylimidazole (poly(EGDE-MAA-2MI)) with SDS (or SDBS) were suggested. The first one is adsorption of bisphenol A on the surface of poly(EGDE-MAA-2MI) through hydrogen bonds another one – is embedding of bisphenol A into the hydrophobic environment polyampholyte-surfactant complex.

Application aspects of macromolecular complexes of polyampholytes

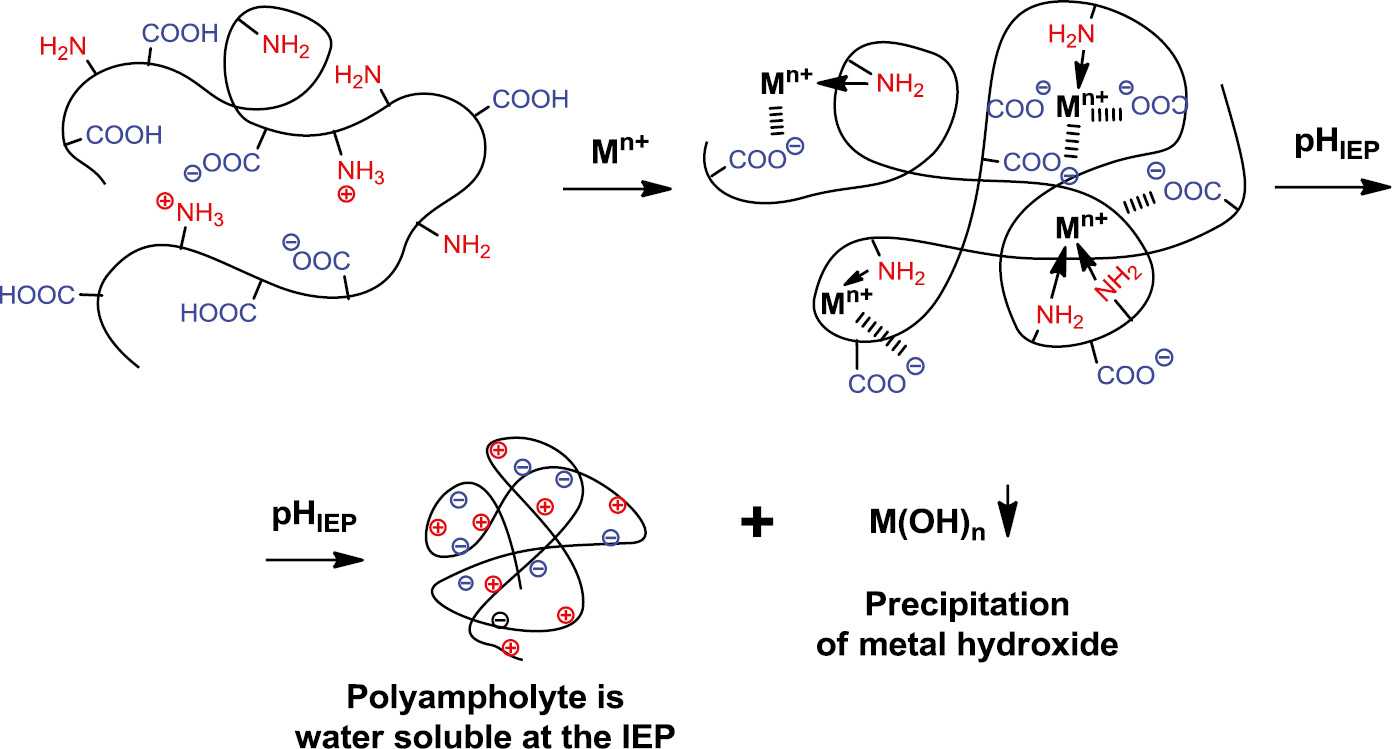

Application of linear polyampholytes for removal of metal ions is illustrated in Fig. 12 [100], [101]. Complexation of transition metal ions with acid-base groups proceeds via formation of ion-coordination (or chelate) complexes. Release of metal ions takes place at the IEP of polyampholytes as schematically shown below.

Sorption of transition metal ions by linear polyampholytes and release at the IEP.

If the IEP of polyampholytes are displaced in the alkaline region (pH 8–10), transition metal ions are precipitated in the form of metal hydroxyde and the polyampholyte is found in the supernatant. In contrast, if the IEP arranges in acidic region and polyampholyte is insoluble, then the polyampholyte precipitates while metal ions retained in supernatant. Application of macroporous amphoteric hydrogels and cryogels is more efficient and economically feasible for removal of metal ions from wastewaters [102]. Polyampholyte hydrogels modified by graphene oxide (GO) exhibited good mechanical property, durability, high sorption capacity, and excellent recyclability to design adsorbents for removal hazard metal ions in wastewater (Fig. 13).

![Fig. 13:

Polyampholyte hydrogel containing amine and carboxylic groups modified by graphene oxide (a), sorption and desorption of metal ions (b), purification of industrial water from Pb2+ and Cd2+ ions (c). (Reprinted with permission from Ref. [102]).](/document/doi/10.1515/pac-2019-1104/asset/graphic/j_pac-2019-1104_fig_013.jpg)

Polyampholyte hydrogel containing amine and carboxylic groups modified by graphene oxide (a), sorption and desorption of metal ions (b), purification of industrial water from Pb2+ and Cd2+ ions (c). (Reprinted with permission from Ref. [102]).

The advantages of polyampholyte hydrogel sorbent are: (i) excellent mechanical strength for separation and reusability; (ii) fast sorption rate and high sorption capacity; (iii) high treatment capacity on fixed-bed column; (iv) efficient removal of toxic metal ions from industrial effluent; (v) low cost, US$ 6.3/kg.

The efficiency of removal of metal ions from the waste by polyampholyte hydrogels and cryogels is compared in Table 4.

Comparison of sorption and desorption efficiency of polyampholyte sorbents with respect to various metal ions.

| Amphoteric sorbent | Metal ions | Sorption capacity, mg/g, % | Removal capacity, % | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AA-MMA-Teta | Pb | 216.1 | 91.5 | [102] |

| Cd | 153.8 | 87.5 | ||

| Poly(EGDE-MAA-2MI) | Pb | 182 | No data | [75] |

| Cd | 201 | No data | ||

| Chitosan-g-poly(acrylic acid) modified by magnetic Fe3O4 nanoparticles | Pb | 695.2 | 95.0 | [103] |

| Cd | 308.8 | 90.7 | ||

| aminocarboxylate-maleic acid | Hg | 263.0 | 98.0 | [104] |

| Aminoacid containing hydrogels | Cu | 77.5 and 99.4% | 88 and 93% | [105] |

| Polycarbobetaine | Cu | 253.0 | 97 | [72], [73], [74] |

| Allylamine-methacrylic acid | Cu | 634.9 | 51.4 | |

| Ni | 586.4 | 67.2 | [78] | |

| Co | 588.7 | 62.0 |

In spite of higher sorption capacity of macroporous amphoteric cryogels with respect to transition metal ions, they exhibit lower desorption ability in comparison with amphoteric hydrogels. This is probably due to capturing of metal ions in “dead” volumes of networks that are inaccessible for desoprtion. Special interest represents magnetic macroporous chitosan-g-poly(acrylic acid) hydrogels which possess high adsorption capacity, easy separation and excellent reusability [103] (Fig. 14).

![Fig. 14:

Magnetic separation of metal ions by magnetic macroporous amphoteric hydrogel from aqueous solution (a) and adsorption capacity of Cd2+ and Pb2+ on initial concentration of metal ions (b). (Reprinted with permission from Ref. [103]).](/document/doi/10.1515/pac-2019-1104/asset/graphic/j_pac-2019-1104_fig_014.jpg)

Magnetic separation of metal ions by magnetic macroporous amphoteric hydrogel from aqueous solution (a) and adsorption capacity of Cd2+ and Pb2+ on initial concentration of metal ions (b). (Reprinted with permission from Ref. [103]).

Purification of dyes from the industrial wastes is extremely important from ecological point of view. Removal of methylene blue (MB) [104], methyl orange (MO) [95], Congo red [106] was performed with the help of aminocarboxylate-maleic acid based hydrogels [104], linear and crosslinked polyampholytes based on N-acryloyl-N′-ethylpiperzine and maleic acid [106] as well as amphoteric cryogels composed of AMPS-APTAC [95].

Removal efficiency of dyes by polyampholyte hydrogels and cryogels is compared in Table 5. The best sorption capacity of dyes is exhibited by the hydrogels of aminocarboxylate-maleic acid and chitosan-g-poly(acrylic acid) sorbents modified by clay minerals [107], [108].

Sorption and desorption capacity of polyampholyte hydrogels and cryogels with respect to dye molecules.

| Amphoteric sorbent | Dyes | Sorption capacity, mg/g | Removal capacity, % | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N-acryloyl-N′-ethylpiperzine-maleic acid | Congo red | 8.37–11.45 | 68–93 | [106] |

| Chitosan-g-poly(acrylic acid) modified bymontmorillonite | MB | 1859 | No data | [107] |

| Chitosan-g-poly(acrylic acid) modified byattapulgite | 1873 | No data | [108] | |

| Aminocarboxylate-maleic acid | MB | 2101.0 | 99.4 | [109] |

| MO | No data | 30 | ||

| AMPS-APTAC (75:25) | MB | 480.0 | 95.0 | [95] |

| AMPS-APTAC (25:75) | MO | 98.3 | 87.0 |

Conclusion

In this review we concisely described the macromolecular complexes of synthetic polyampholytes with participation of proteins, DNA, polyelectrolytes, metal ions, surfactants and dyes that can cause impact on biotechnology [109], medicine [110] in particular, for formulation of gene delivery [40], [111] or pH-triggered drug delivery [112] systems, as contrast agents [34] in magnetic resonance imaging with long in vivo circulation time. Amphoteric hydrogels and cryogels due to micro- and macroporous structure, high sorption capacity, easy and fast desorption, durability, and good mechanical stability have potential application for removal and recovery of dye and metal ions from the wastewater [103], [104], [105], [106], [107], [108]. Reduction and stabilization of metal nanoparticles by functional groups of polyampholytes [79], [80], [81], [82] followed by supporting of metal nanoparticles onto inorganic supporters [83] and immobilization within hydrogel and cryogel matrix [84], [85], [86], [87], [88], [89] is perspective for construction of active, stable, selective, and reusable nanocatalysts for hydrogenation, oxidation and isomerization processes at mild conditions. Macromolecular complexes of polyampholytes can be expanded to polyampholytic nano-, micro- and macrogels, amphoteric membranes and thin films including LbL [6], [113]. Molecularly imprinted polyampholyte hydrogels and cryogels might be effective tool for binding, separation and purification of target proteins from their mixture. Complexes of polyampholyte hydrogels and cryogels with metal nanoparticles and enzymes may represent a new generation of macromolecular systems to provide a rational basis for future development of heterogenized homogeneous catalysts and biocatalysts [86], [87], [88], [89], [114]. Design of macromolecular complexes of polyampholytes at the interface of two immiscible liquids is also promising subject. The attention is paid to protein-mimetic alternating and blockpolyampholytes derived respectively from amino acids [115] and copolypeptides [116] as new protein-resistant materials with inherent antimicrobial properties [117]. Macromolecular complexes of amphoteric ionic liquids [118], [119] are also prospective materials to develop energy storage devices.

Article note

A collection of papers from the 18th IUPAC International Symposium Macromolecular-Metal Complexes (MMC-18), held at the Lomonosov Moscow State University, 10–13 June 2019.

Acknowledgements

Financial support from the Ministry of Education and Science of the Republic of Kazakhstan (Funder Id: http://dx.doi.org/10.13039/501100004561, Grant No. IRN AP05131003, 2018-2020) is greatly acknowledged.

References

[1] A. B. Lowe, C. L. McCormick. Chem. Rev. 102, 4177 (2002).10.1021/cr020371tSearch in Google Scholar

[2] A. V. Dobrynin, R. H. Colby, M. Rubinstein. J. Polym. Sci. Part B: Polym. Phys. 42, 3513 (2004).10.1002/polb.20207Search in Google Scholar

[3] A. Laschewsky. Polymers 6, 1544 (2014).10.3390/polym6051544Search in Google Scholar

[4] E. Su, O. Okay. Eur. Polym. J. 88, 191 (2017).10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2017.01.029Search in Google Scholar

[5] S. E. Kudaibergenov. Polyampholytes: Synthesis, Characterization and Application, Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers, New York (2002).10.1007/978-1-4615-0627-0Search in Google Scholar

[6] S. E. Kudaibergenov. Encycl. Polym. Sci. Technol. pp. 1, John Wiley Interscience, Hoboken, NJ, USA (2008).Search in Google Scholar

[7] S. E. Kudaibergenov, A. Cifferi. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 28, 1969 (2007).10.1002/marc.200700197Search in Google Scholar

[8] S. Kudaibergenov, N. Nueraje, V. Khutoryanskiy. Soft Matter. 8, 9302 (2012).10.1039/c2sm25766aSearch in Google Scholar

[9] S. Kudaibergenov, W. Jaeger, A. Laschewsky. Adv. Polym. Sci. 201, 157 (2006).10.1007/12_078Search in Google Scholar

[10] S. E. Kudaibergenov, N. Nuraje. Polymers. 10, 1146 (2018).10.3390/polym10101146Search in Google Scholar

[11] R. Everaers, A. Johner, J. F. Joanny. Europhys. Lett. 37, 275 (1997).10.1209/epl/i1997-00143-xSearch in Google Scholar

[12] P. G. Higgs, J. F. Joanny. J. Chem. Phys. 94, 1543 (1991).10.1063/1.460012Search in Google Scholar

[13] H. S. Samanta, D. Chacraborty, D. Thirumalai. J. Chem. Phys. 149, 163323 (2018).10.1063/1.5035428Search in Google Scholar

[14] C. Dai, Zh. Xu, Y. Wu, C. Zou, X. Wu, T. Wang, X. Guo, M. Zhao. Polymers 9, 296 (2017).10.3390/polym9070296Search in Google Scholar

[15] A. Rabiee, E.-L. Amir, J. Hajar. Rev.Chem.Eng. 30, 501 (2014).10.1515/revce-2014-0004Search in Google Scholar

[16] M. Barcellona, N. Johnson, M. T. Bernards. Langmuir 31, 13402 (2015).10.1021/acs.langmuir.5b03597Search in Google Scholar

[17] Sh. Su, R. Wu, X. Huang, L. Cao, J. Wang. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 102, 986 (2006).10.1002/app.23990Search in Google Scholar

[18] Y.-J. Shih, Y. Chang, D. Quemener, H.-S. Yang, J.-F. Jhong, F.-M. Ho, A. Higuchi, Y. Chang. Langmuir 30, 6489 (2014).10.1021/la5015779Search in Google Scholar

[19] D. A. Z. Wever, F. Picchioni, A. A. Broekhuis. Prog. Polym. Sci. 36, 1558 (2011).10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2011.05.006Search in Google Scholar

[20] R. Liu, W. Pu, L. Wang, Q. Chen, Z. Li, Y. Lie, B. Lib. RSC Adv. 5, 69980 (2015).10.1039/C5RA13865ESearch in Google Scholar

[21] L. Zhang, H. S. Sundaram, Z. Wei, C. Li, Z. Yuan. React. Funct. Polym. 118, 51 (2017).10.1016/j.reactfunctpolym.2017.07.006Search in Google Scholar

[22] S. Nath. J. Chem. Tech. Biotechnol. 62, 295 (1995).10.1002/jctb.280620313Search in Google Scholar

[23] T. Goloub, A. Keizer, M. A. C. Stuart. Macromolecules 32, 8441 (1999).10.1021/ma9907441Search in Google Scholar

[24] R. Varoqui, Q. Tran, E. Pefferkorn. Macromolecules 12, 831 (1979).10.1021/ma60071a008Search in Google Scholar

[25] S. E. Kudaibergenov, V. A. Frolova, E. A. Bekturov, S. R. Rafikov. Dokl. Akad. Nauk SSSR 311, 396 (1990).Search in Google Scholar

[26] E. A. Bekturov, S. E. Kudaibergenov, V. A. Frolova, R. S. Schultz, J. Zoller. Makromol. Chem. 191, 1329 (1990).10.1002/macp.1990.021910612Search in Google Scholar

[27] R. Nakahata, S. Yusa. Polymers 10, 205 (2018).10.3390/polym10020205Search in Google Scholar

[28] K. Nakai, K. Ishihara, M. Kappl, S. Fujii, Y. Nakamura, S. Yusa. Polymers 9, 49 (2017).10.3390/polym9020049Search in Google Scholar

[29] S. Gao, A. Holkar, S. Srivastava. Polymers 11, 10979 (2019).10.3390/polym11071097Search in Google Scholar

[30] X. Wang, K. Zheng, Y. Si, X. Guo, Y. Xu. Polymers 11, 82 (2019).10.3390/polym11010082Search in Google Scholar

[31] J. M. Horn, R. A. Kapelner, A. C. Obermeyer. Polymers 11, 578 (2019).10.3390/polym11040578Search in Google Scholar

[32] M. Ishihara, S. Kishimoto, S. Nakamura, Y. Sato, H. Hattori. Polymers 11, 672 (2019).10.3390/polym11040672Search in Google Scholar

[33] P. Semenyuk, V. Muronetz. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20 1251 (2019).10.3390/ijms20051251Search in Google Scholar

[34] T. Zhao, K. Chen, H. Gu. J. Phys. Chem. B 117, 14129 (2013).10.1021/jp407157nSearch in Google Scholar

[35] S. Asayama, H. Kato, H. Kawakami, S. Nagaoka. Polym. Adv. Technol. 18, 329 (2007).10.1002/pat.890Search in Google Scholar

[36] S. Asayama, K. Seno, H. Kawakami. Chem. Lett. 42, 358 (2013).10.1246/cl.121263Search in Google Scholar

[37] V. I. Izumrudov, M. V. Zhiryakova, S. E. Kudaibergenov. Biopolymers 52, 94 (1999).10.1002/1097-0282(1999)52:2<94::AID-BIP3>3.0.CO;2-OSearch in Google Scholar

[38] S. E. Kudaibergenov, E. A. Bekturov. Vysokomol. Soedin. Ser. A 31, 2614 (1989).10.1016/0032-3950(89)90325-0Search in Google Scholar

[39] Y.-J. Shih, Y. Chang, D. Quemener, H.-S. Yang, J.-F. Jhong, F.-M. Ho, A. Higuchi, Y. C. Chang. Langmuir 30, 6489 (2014).10.1021/la5015779Search in Google Scholar

[40] S. Ahmed, T. Nakaji-Hirabayashi, T. Watanabe, T. Hohsaka, K. Matsumura. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 3, 1677 (2017).10.1021/acsbiomaterials.7b00176Search in Google Scholar

[41] S. Ahmed, S. Fujita, K. Matsumura. Nanoscale 8, 15888 (2016).10.1039/C6NR03940ESearch in Google Scholar

[42] S. Ahmed, K. Matsumura. Cryobiol. Cryotechnol. 62, 143 (2016).Search in Google Scholar

[43] C. Yoshihara, C.-Y. Shew, T. Ito, Y. Koyama. Biophys. J. 98, 1257 (2010).10.1016/j.bpj.2009.11.047Search in Google Scholar

[44] M. F. Leal Denis, R. R. Carballo, A. J. Spiaggi, P. C. Dabas, V. Campo Dall’ Orto, J. M. L. Martinez. React. Funct. Polym. 68, 169 (2008).10.1016/j.reactfunctpolym.2007.09.011Search in Google Scholar

[45] C. S. Patrickios, C. J. Jang, W. R. Hertler, T. A. Hatton. Polym. Prepr. 1993, 34, 954.Search in Google Scholar

[46] C. S. Patrickios, C. J. Jang, W. R. Hertler, T. A. Hatton. “Protein interactions with acrylic polyampholytes”, in Macro-ion Characterization from Dilute Solutions to Complex Fluids, K. S. Schmitz (Ed.), pp. 257–267. ACS Symposium Series, Washington, DC (1994).10.1021/bk-1994-0548.ch019Search in Google Scholar

[47] S. Nath, C. S. Patrickios, T. A. Hatton. Biotechnol. Prog. 11, 99 (1995).10.1021/bp00031a014Search in Google Scholar

[48] C. S. Patrickios, W. R. Hertler, T. A. Hatton. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 44, 1031 (1994).10.1002/bit.260440903Search in Google Scholar

[49] A. G. Didukh, G. Sh. Makysh, L. A. Bimendina, S. E. Kudaibergenov. “Bovine serum albumine complexation with some polyampholytes”, in Advanced Macromolecular and Supramolecular Materials and Processes, K. E. Geckeler (Ed.), pp. 265–275, Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers, Springer, Boston, MA (2003).10.1007/978-1-4419-8495-1_20Search in Google Scholar

[50] S. E. Kudaibergenov, G. S. Tatykhanova, A. N. Klivenko. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 133, 43784-1 (2016).10.1002/app.43784Search in Google Scholar

[51] R. Kanazawa, A. Sasaki, H. Tokuyama. Sep. Purif. Technol. 96, 26 (2012).10.1016/j.seppur.2012.05.016Search in Google Scholar

[52] J. T. Huang, J. Zhang, J. Q. Zhang, S. H. Zheng. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 95, 358 (2005).10.1002/app.21262Search in Google Scholar

[53] J. Jeon, A. V. Dobrynin. Macromolecules 38, 5300 (2005).10.1021/ma050303jSearch in Google Scholar

[54] J. Jeon, A. V. Dobrynin. J. Phys. Chem. 110, 24652 (2006).10.1021/jp064288bSearch in Google Scholar

[55] A. K. N. Nair, A. M. Jimenez, S. Sun. J. Phys. Chem. B. 121, 7987 (2017).10.1021/acs.jpcb.7b04582Search in Google Scholar

[56] I. V. Savinova, N. A. Fedoseeva, V. P. Evdakov, V. A. Kabanov. Vysokomol. Soedin. Ser. A. 18, 2050 (1976).10.1016/0032-3950(76)90111-8Search in Google Scholar

[57] E. E. Skorikova, G. A. Vikhoreva, R. I. Kalyuzhnaya, A. B. Zezin, L. S. Gal’braikh, V. A. Kabanov. Vysokomol. Soedin. Ser. A. 30, 44 (1988).10.1016/0032-3950(88)90253-5Search in Google Scholar

[58] M. F. Zansokhova, V. B. Rogacheva, Zh. G. Gulyaeva, A. B. Zezin, J. Joosten, J. Brekman. Polym. Sci. Ser. A. 50, 656 (2008).10.1134/S0965545X08060096Search in Google Scholar

[59] V. B. Rogacheva, T. V. Panova, E. V. Bykova, A. B. Zezin, J. Joosten, J. Brekman. Polym. Sci. Ser. A. 51, 242 (2009).10.1134/S0965545X0903002XSearch in Google Scholar

[60] T. Elschner, T. Heinze. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 10, 1549 (2014).10.3762/bjoc.10.159Search in Google Scholar

[61] M. Hahn, J. Koetz, A. Ebert, R. Schmolke, B. Philipp, S. Kudaibergenov, V. Sigitov, E. Bekturov. Acta Polym. 40, 331 (1989).10.1002/actp.1989.010400508Search in Google Scholar

[62] J. Koetz, B. Philipp, M. Hahn, A. Evert, R. Schmolke, S. E. Kudaibergenov, V. B. Sigitov, E. A. Bekturov. Acta Polym. 40, 405 (1989).10.1002/actp.1989.010400610Search in Google Scholar

[63] Zh. E. Ibraeva, M. Hahn, W. Jaeger, L. A. Bimendina, S. E. Kudaibergenov. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 205, 2464 (2004).10.1002/macp.200400242Search in Google Scholar

[64] Zh. E. Ibraeva, M. Hahn, W. Jaeger, A. Laschewsky, L. A. Bimendina, S. E. Kudaibergenov. Macromol. Mater. Eng. 290, 769 (2005).10.1002/mame.200500080Search in Google Scholar

[65] S. E. Kudaibergenov, E. A. Bekturov, S. R. Rafikov. Dokl. Akad. Nauk SSSR. 311, 396 (1990).Search in Google Scholar

[66] E. A. Bekturov, S. E. Kudaibergenov, V. A. Frolova, R. E. Khamzamulina, R. C. Schulz, J. Zoller. Makromol. Chem. 191, 457 (1990).10.1002/macp.1990.021910220Search in Google Scholar

[67] C. Guang, W. Guojun, W. Liming, S. Zhang, Z. Su. Chem. Commun. 15, 1741 (2008).Search in Google Scholar

[68] Y. Tokuda, T. Miyaqishima, K. Tomida, B. Wanq, S. Takahashi, K. Sato, J. Anzai. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 399, 26 (2013).10.1016/j.jcis.2013.02.039Search in Google Scholar

[69] B. Wang, Y. Tokuda, K. Tomida, S. Takahashi, K. Sato. Materials 6, 2351 (2013).10.3390/ma6062351Search in Google Scholar

[70] L. Chen, Y. Honma, T. Mizutani, D.-J. Liaw, J. P. Gong, Y. Osada. Polymer 41, 141 (2000).10.1016/S0032-3861(99)00161-5Search in Google Scholar

[71] S. E. Kudaibergenov, N. Vozhzhova, A. A. Andrusenko, E. M. Shaikhutdinov, E. A. Bekturov. Izv. Akad. NaukKazSSR, Ser. Khim. 5, 42 (1986).Search in Google Scholar

[72] J. Mouton, M. Turmine, H. Van den Berghe, J. Coudane. Chem. Eng. J. 283, 1168 (2016).10.1016/j.cej.2015.08.058Search in Google Scholar

[73] J. Mouton, M. Turmine, H. Van den Berghe, J. Coudane. Int. J. Sus. Dev. Plann. 11, 192 (2016).10.2495/SDP-V11-N2-192-202Search in Google Scholar

[74] J. Mouton, G. M. Kirkelund, Y. Hassen, S. Chastagnol, H. Van den Berghe, J. Coudane, M. Turmine. Mat. Today Commun. 20, 100575 (2019).10.1016/j.mtcomm.2019.100575Search in Google Scholar

[75] V. Campo Dall’ Orto, J. M. Lazaro-Martinez. “Design, characterization, and environmental applications of hydrogels with metal ion coordination properties”, in Emerging Concepts in Analysis and Applications of Hydrogels, S. B. Majee (Ed.), pp. 101–130, INTECH. Rijeka, Croatia (2016).10.5772/62902Search in Google Scholar

[76] J. G. Noh, Y. J. Sung, K. E. Geckeler, S. E. Kudaibergenov. Polymer 46, 2183 (2005).10.1016/j.polymer.2005.01.005Search in Google Scholar

[77] V. A. Kabanov. Rus. Chem. Rev. 74, 5 (2005).10.1070/RC2005v074n01ABEH001165Search in Google Scholar

[78] G. Tatykhanova, Zh. Sadakbayeva, D. Berillo, I. Galaev, Kh. Abdullin, Zh. Adilov, S. Kudaibergenov. Macromol. Symp. 317–318, 7 (2012).10.1002/masy.201100063Search in Google Scholar

[79] N. Schulze, C. Prietzel, J. Koetz. Colloid. Polym. Sci. 294, 1297 (2016).10.1007/s00396-016-3890-ySearch in Google Scholar

[80] C. Note, J. Koetz, L. Wattebled, A. Laschewsky. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 308, 162 (2007).10.1016/j.jcis.2006.12.047Search in Google Scholar

[81] S. Li, Y. Wu, J. Wang, Q. Zhang, Y. Kou, S. Zhang. J. Mater. Chem. 20, 4379 (2010).10.1039/c0jm00255kSearch in Google Scholar

[82] B. Mahltig, N. Cheval, J. F. Gohy, A. Fahmi. J. Polym. Res. 17, 579 (2010).10.1007/s10965-009-9346-zSearch in Google Scholar

[83] E. K. Baygazieva, N. N. Yesmurzayeva, G. S. Tatykhanova, G. A. Mun, V. V. Khutoryanskiy, S. E. Kudaibergenov. Int. J. Biol. Chem. 7, 14 (2014).10.26577/2218-7979-2014-7-1-14-23Search in Google Scholar

[84] S. Kudaibergenov. Gels. 5, 8 (2019).10.3390/gels5010008Search in Google Scholar

[85] S. E. Kudaibergenov, G. S. Tatykhanova, B. S. Selenova. J. Inorg. Organometal. Polym. Mater. 26, 1198 (2016).10.1007/s10904-016-0373-zSearch in Google Scholar

[86] A. N. Klivenko, G. S. Tatykhanova, N. Nuraje, S. E. Kudaibergenov. Bull. Karaganda State University, Ser. Khim. 4, 10 (2015).Search in Google Scholar

[87] G. S. Tatykhanova, A. N. Klivenko, G. M. Kudaibergenova, S. E. Kudaibergenov. Macromol. Symp. 363, 49 (2016).10.1002/masy.201500137Search in Google Scholar

[88] M. Aldabergenov, M. Dauletbekova, A. Shakhvorostov, G. Toleutay, A. Klivenko, S. Kudaibergenov. J. Chem. Technol. Metal. 53, 17 (2018).Search in Google Scholar

[89] S. Kudaibergenov, M. Dauletbekova, G. Toleutay, S. Kabdrakhmanova, T. Seilkhanov, Kh. Abdullin. J. Inorg. Organometal. Polym. Mater. 28, 2427 (2018).10.1007/s10904-018-0930-8Search in Google Scholar

[90] N. Khan, B. Brettman. Polymers 11, 51 (2019).10.3390/polym11010051Search in Google Scholar

[91] E. A. Bekturov, S. E. Kudaibergenov, G. S. Kanapyanova. Polymer Bull. 11, 551 (1984).10.1007/BF01045336Search in Google Scholar

[92] E. A. Bekturov, S. E. Kudaibergenov, G. S. Kanapyanova. Kolloid. Zh. 46, 861 (1984).Search in Google Scholar

[93] A. F. Thunemann, K. Sander, W. Jaeger. Langmuir 18, 5099 (2002).10.1021/la020188vSearch in Google Scholar

[94] I. M. Harrison, F. Candau, R. Zana. Colloid. Polym. Sci. 277, 48 (1999).10.1007/s003960050366Search in Google Scholar

[95] G.Toleutay, M. Dauletbekova, A. Shakhvorostov, S. Kudaibergenov. Macromol. Symp. 385, 1800160 (2019).10.1002/masy.201800160Search in Google Scholar

[96] E. A. Bekturov, S. E. Kudaibergenov, R. E. Khamzamulina, R. C. Schulz, J. Zoller. Makromol. Chem. Rapid Commun. 12, 37 (1991).10.1002/marc.1991.030120108Search in Google Scholar

[97] J. Niskanen, J. Vapaavuori, C. Pellerin, F. M. Winnik, H. Tenhu. Polymer 127, 77 (2017).10.1016/j.polymer.2017.08.057Search in Google Scholar

[98] S. Morisada, H. Suzuki, S. Emura, Y. Hirokawa, Y. Nakano. Adsorption 14, 621 (2008).10.1007/s10450-008-9112-2Search in Google Scholar

[99] J. M. Lazaro-Martinez, M. F. Leal Denis, L. R. Denaday, V. Campo Dall’ Orto. Talanta 80, 789 (2019).10.1016/j.talanta.2009.07.065Search in Google Scholar

[100] E. A. Bekturov, S. E. Kudaibergenov. USSR Author certificate 1086391, Filed 1982, Issued 1983.Search in Google Scholar

[101] E. A. Bekturov, S. E. Kudaibergenov, G. M. Zhaimina. USSR Author certificate 1231810, Filed 1983, Issued 1984.Search in Google Scholar

[102] G. Zhou, J. Luo, C. Liu, J. Ma, Y. Tang, Z. Zeng, S. Luo. Water Res. 89, 151 (2016).10.1016/j.watres.2015.11.053Search in Google Scholar

[103] Y. Zhu, Y. Zheng, F. Wang, A. Wang. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 93, 483 (2016).10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2016.09.005Search in Google Scholar

[104] S. A. Ali, I. Y. Yaagob, M. A. J. Mazumder, H. A. Al-Muallem. J. Hazard. Mater. 369, 642 (2019).10.1016/j.jhazmat.2019.02.082Search in Google Scholar

[105] S. A. Ali, O. C. S. Al Hamouz, N. M. Hassan. J. Hazard. Mater. 47, 248 (2013).10.1016/j.jhazmat.2012.12.052Search in Google Scholar

[106] G. R. Deen, T. T. Wei, L. K. Fatt. Polymer 104, 91 (2016).10.1016/j.polymer.2016.09.094Search in Google Scholar

[107] L. Wang, J. Zhang, A. Wang. Colloids Surf. A: PhysicoChem Eng. Aspects 322, 47 (2008).10.1016/j.colsurfa.2008.02.019Search in Google Scholar

[108] L. Wang, J. Zhang, A. Wang. Desalination 266, 33 (2011).10.1016/j.desal.2010.07.065Search in Google Scholar

[109] S. L. Haag, M. T. Barnards. Gels 3, 41 (2017).10.3390/gels3040041Search in Google Scholar

[110] K. Matsumura, R. Rajan, S. Ahmed, M. Jain. “Medical application of polyampholytes”, in Biopolymers for Medical Applications, J. M. Ruso, P. V. Messina (Eds.), pp. 173–190, CRC Press, Boca Raton (2017).10.1201/9781315368863-8Search in Google Scholar

[111] E. N. Danilovtseva, U. M. Krishnan, V. A. Pal’shin, V. V. Annekov. Polymers 9, 624 (2017).10.3390/polym9110624Search in Google Scholar

[112] H.-C. Wang, J. M. Grolman, A. Rizvi, G. S. Hisao, C. M. Rienstra, S. C. Zimmerman. ACS Macro Lett. 6, 321 (2017).10.1021/acsmacrolett.6b00968Search in Google Scholar

[113] M. Bradley, B. Vincent, G. Burnett. Colloid. Polym. Sci. 287, 345 (2009).10.1007/s00396-008-1978-8Search in Google Scholar

[114] T. Gancheva, N. Virgilio. React. Chem. Eng. 5, (2019). Doi: 10.1039/c8re00337h.10.1039/c8re00337hSearch in Google Scholar

[115] J. Sun, P. Cernoch, A. Volkel, Y. Wei, J. Rukolainen, H. Schlad. Macromolecules 49, 5494 (2016).10.1021/acs.macromol.6b00817Search in Google Scholar

[116] Y. Tao, S. Wang, X. Zhang, Z. Wang, Y. Tao, X. Wang. Biomacromolecules 19, 936 (2018).10.1021/acs.biomac.7b01719Search in Google Scholar

[117] S. J. Shirbin, S. J. Lam, N. J. Chan, M. M. Ozmen, Q. Fu, N. O’Brien-Simpson, E. C. Reynolds, G. G. Qiao. ACS Macro Lett. 5, 552 (2016).10.1021/acsmacrolett.6b00174Search in Google Scholar

[118] H. Ohno, M. Yoshizawa-Fujita, W. Ogihara. “Amphoteric polymers”, in Electrochemical Aspects of Ionic Liquids, H. Ohno (Ed.), pp. 433–439, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey (2011).10.1002/9781118003350.ch31Search in Google Scholar

[119] C. C. J. Fouillet, T. L. Greaves, J. F. Quinn, T. P. Davis, T. Adamcik, M. A. Sani, F. Separovic, C. J. Drummond, R. Mezzenga. Macromolecules 50, 8965 (2017).10.1021/acs.macromol.7b01768Search in Google Scholar

© 2020 IUPAC & De Gruyter. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. For more information, please visit: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- In this issue

- Preface

- The 18th IUPAC International Symposium Macromolecular-Metal Complexes (10–13 June, 2019, Moscow – Tver – Myshkin – Uglich – Moscow)

- Conference papers

- Magnetically separable Ru-containing catalysts in supercritical deoxygenation of fatty acids

- Palladium nanoparticles supported on nitrogen doped porous carbon material derived from cyclodextrin, glucose and melamine based polymer: promising catalysts for hydrogenation reactions

- Macromolecular complexes of polyampholytes

- Coordination polymers based on trans, trans-muconic acid: synthesis, structure, adsorption and thermal properties

- Allylic hydrocarbon polymers complexed with Fe(II)(salen) as a ultrahigh oxygen-scavenging and active packaging film

- Removal of chromium ions by functional polymers in conjunction with ultrafiltration membranes

- Engineering the ABIO-BIO interface of neurostimulation electrodes using polypyrrole and bioactive hydrogels

- Formation of ruthenium nanoparticles inside aluminosilicate nanotubes and their catalytic activity in aromatics hydrogenation: the impact of complexing agents and reduction procedure

- Multifunctional carriers for controlled drug delivery

- Evaluation of sulfide catalysts performance in hydrotreating of oil fractions using comprehensive gas chromatography time-of-flight mass spectrometry

- Ni–Mo sulfide nanosized catalysts from water-soluble precursors for hydrogenation of aromatics under water gas shift conditions

- Combination of nanoparticles and carbon nanotubes for organic hybrid thermoelectrics

- Ultrafine metal-polymer catalysts based on polyconjugated systems for Fisher–Tropsch synthesis

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- In this issue

- Preface

- The 18th IUPAC International Symposium Macromolecular-Metal Complexes (10–13 June, 2019, Moscow – Tver – Myshkin – Uglich – Moscow)

- Conference papers

- Magnetically separable Ru-containing catalysts in supercritical deoxygenation of fatty acids

- Palladium nanoparticles supported on nitrogen doped porous carbon material derived from cyclodextrin, glucose and melamine based polymer: promising catalysts for hydrogenation reactions

- Macromolecular complexes of polyampholytes

- Coordination polymers based on trans, trans-muconic acid: synthesis, structure, adsorption and thermal properties

- Allylic hydrocarbon polymers complexed with Fe(II)(salen) as a ultrahigh oxygen-scavenging and active packaging film

- Removal of chromium ions by functional polymers in conjunction with ultrafiltration membranes

- Engineering the ABIO-BIO interface of neurostimulation electrodes using polypyrrole and bioactive hydrogels

- Formation of ruthenium nanoparticles inside aluminosilicate nanotubes and their catalytic activity in aromatics hydrogenation: the impact of complexing agents and reduction procedure

- Multifunctional carriers for controlled drug delivery

- Evaluation of sulfide catalysts performance in hydrotreating of oil fractions using comprehensive gas chromatography time-of-flight mass spectrometry

- Ni–Mo sulfide nanosized catalysts from water-soluble precursors for hydrogenation of aromatics under water gas shift conditions

- Combination of nanoparticles and carbon nanotubes for organic hybrid thermoelectrics

- Ultrafine metal-polymer catalysts based on polyconjugated systems for Fisher–Tropsch synthesis