Abstract

CD44, a cell-surface glycoprotein, plays an important role in cell proliferation, adhesion, migration, and other biological functions, which are related with the physiological and pathologic activities of cells. Especially, CD44 is extensively expressed within adult bone marrow and has been considered as an important marker for some cancer stem cells (CSCs) in various types of tumors. Therefore, it is essential to understand the variations in CD44 expression of stem cells and cancer cells for further clinical applications. In this paper, CD44 expression was assessed on a human colon cancer cell line (SW620), a human mesenchymal stem-like cell line (3A6), and a human foreskin fibroblast line (Hs68). We used chitosan to establish a suspension culture model to develop multicellular spheroids to mimic a three-dimension (3D) in vivo environment. Obviously, CD44 expression on 3A6 and SW620 cells was dynamic and diverse when they were in the aggregated state suspended on chitosan, while Hs68 cells were relatively stable. Furthermore, we discuss how to regulate CD44 expression of 3A6 and SW620 cells by the interactions between cell and cell, cell and chitosan, as well as cell and microenvironment. Finally, the possible mechanism of chitosan to control CD44 expression of cells is proposed, which may lead to the careful use of chitosan for potential clinical applications.

Introduction

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) with the capability of self-renewal and multi-lineage differentiation have been focused on in various applications of regenerative medicine. Surface antigens such as CD44, CD29, CD105, and CD166 are currently used to identify MSCs [1], [2], [3], [4]. On the other hand, cancer cells or tumor-derived cancer stem cells (CSCs) also display the characteristics of MSCs [5], [6], [7]. Similarly, CSCs are identified by their expression of specific surface markers, which include CD44 [8], [9], [10], [11], CD133 [12], [13], and aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 (ALDH1) [14]. In these surface proteins, CD44 is a surface antigen of MSCs, and it is also used as a CSCs marker in tumor entities. The purpose of this study was to investigate whether the common surface marker CD44 of MSCs and CSCs have similar responses under the effect of biomaterial.

Chitosan, prepared from chitin [15], is composed of glucosamine copolymers and N-acetyl-glucosamine [16], [17], [18] with good biocompatibility and biodegradability [19]. Differences of cell adhesion and proliferation on chitosan are dependent on the cell type, environmental pH, and the degree of chitosan deacetylation [20], [21], [22]. Especially, cells can spontaneously form three-dimensional (3D) spheroids on chitosan, and their cellular phenotypes and functions are different from those of monolayer cells [23], [24], [25], [26], [27]. It is known cells in 3D cultures resemble closely the in-vivo situation with regard to cellular shape and cellular environment, and this resemblance can regulate cell gene and protein expressions, and cell behaviors [28], [29], [30], [31], [32], [33], [34]. In addition, chitosan has been proposed to enhance the stemness of MSCs [35], [36] and epithelial–mesenchymal transition of cancer cells [37]. Therefore, chitosan was used to create a 3D environment for the human colon cancer cell line (SW620), the human mesenchymal stem-like cell line (3A6) and the human foreskin fibroblast line (Hs68) to form multicellular spheroids. Fibroblasts were included as a control in this study because they are well-differentiated and stable.

Experimental

Preparation of coated cultured plates

Chitosan (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA; C3646) with more than 75% deacetylated was used, which was extracted from shrimp shells. Chitosan was coated on tissue culture polystyrene (TCPS; Corning Inc., Corning, NY, USA) using methods described in a previous study [36]. One percent (w/w) chitosan dissolved in 0.5 M acetic acid was coated to plates that were about 10 μL/cm2 in size. The chitosan-coated plates were dried in an oven at 60°C and electric-neutralized by 0.5 N NaOH. Next, the plates were exposed under ultraviolet light for sterilization.

Attenuated total reflection-Fourier transform infrared (ATR-FTIR)

Before the plates were analyzed under the ATR-FTIR spectroscopy (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA; UMA 600), they were washed by water twice and air-dried in laminar flow. Absorbances were evaluated from 4000 cm−1 to 650 cm−1 with a spectral resolution of 4 cm−1. The absorbances of the materials and background were evaluated using 64 scans for each sample.

Cell culture

The 3A6 (human mesenchymal stem-like cell line), SW620 (human colon cancer cell line), and Hs68 cells (human newborn foreskin fibroblast line) were maintained in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM; Gibco, Carlsbad, CA, USA) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Biological Industries, Cromwell, CT, USA), 100 U/mL penicillin G, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, and 250 μg/mL amphotericin B (Biological Industries).

The 3A6 cell line was a gift from Professor Hung, Shih-Chieh (Institute of Clinical Medicine, National Yang-Ming University, Taiwan), 3A6 cells were isolated from human bone marrow, and have been confirmed to have the basic characteristics of mesenchymal stem cells [38]. The cell seeding densities were about 1.5×104/cm2 on TCPS and chitosan-coated surfaces.

Immunofluorescence

Cell spheroids were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and incubated with mouse anti-CD44 primary antibody (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA; 33-6700). FITC conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG antibody (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA; 12-506) was used as the secondary antibody. The cells were mounted and observed using a confocal fluorescence microscope (LEICA Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany; SP5).

Flow cytometry

Monolayer and spheroid cells were harvested by trypsinization for 10 min and pipetted to produce single cell suspensions. To determine cell surface antigen expression, the samples were incubated with the CD44-APC (BD Biosciences Pharmingen, San Diego, CA, USA; 559942) antibody. Cells were analyzed on FACSCalibur (BD Bioscience Pharmingen) and positive cells were determined by the higher fluorescent proportion of the population, which was compared with the isotype controls.

Hypoxia and stravation conditions

For hypoxia conditions, cells were cultured in a gas mixture composed of 94% N2, 5% CO2, and 1% O2, which was maintained using an incubator with two air sensors (Baker Ruskinn, South Wales, UK; Invivo2). For stravation conditions, cells were cultured in 1% FBS medium instead.

Preparation of a chitosan-solution-added medium

Preparation of a chitosan-solution-added cultured system followed the previous study [39]. Chitosan was dissolved in 0.5 M acetic acid and mixed with the medium to achieve 0.3 mg chitosan per mL medium. The without-chitosan groups were prepared in the same manner as the chitosan-containing medium without adding chitosan.

Statistical analysis

All measurements are presented as mean±standard deviation. Statistical significance was evaluated using at least three independent samples; comparing groups were performed using the Student’s t-test. Statistically significant values were defined as p<0.05 and p<0.01. These data were generated from several cultures that were generated in different situations and analyzed with TCPS groups as the reference every time.

Results and discussion

Chitosan-coated surface

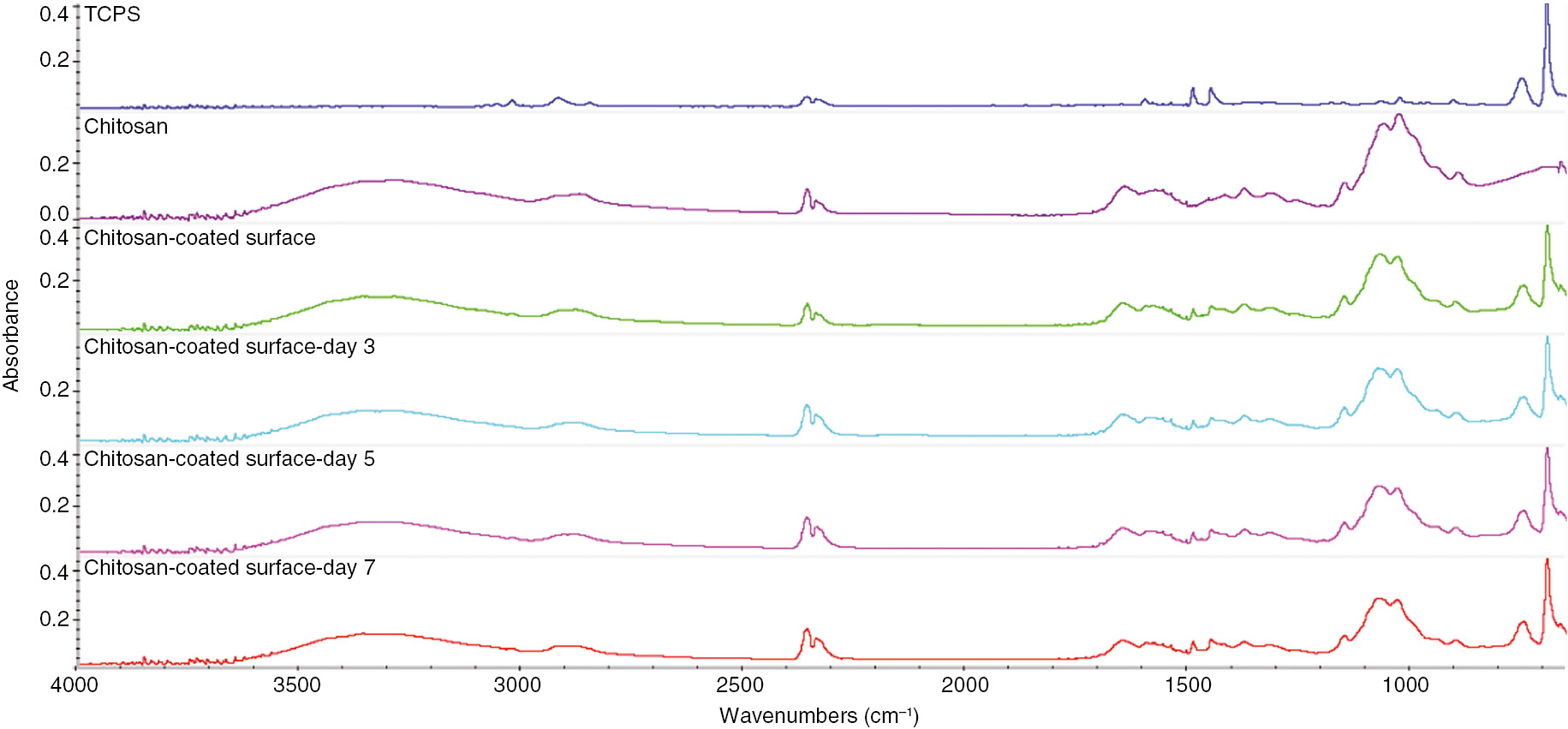

The chemical composition of the chitosan-coated surface was analyzed by ATR-FTIR. Figure 1 shows the ATR-FTIR spectra of TCPS, chitosan, and the chitosan-coated surface before and after the immersion into the medium. In contrast with spectra of TCPS and chitosan, there are significant peaks at 895 (saccharide structure), 1030 and 1060 (C–O stretching vibrations), 1150 (C–O–C in glycosidic linkage), 1580 (N–H bending vibration), 1650 (C=O stretching vibration), and 3000–3600 (N–H and O–H stretching vibration) cm−1 in spectra of chitosan and chitosan-coated surfaces. Moreover, after 3, 5 and 7 days of immersion into the medium, the specific chitosan IR spectra did not significantly change on chitosan-coated TCPS. These results assured that chitosan was successfully coated on TCPS to form a thin film and was stable in the culture medium environment.

ATR-FTIR spectra of TCPS, chitosan membrane, and chitosan-coated surfaces before and after the immersion into the medium within the 7 days.

Morphologies and diameters of multicellular spheroids

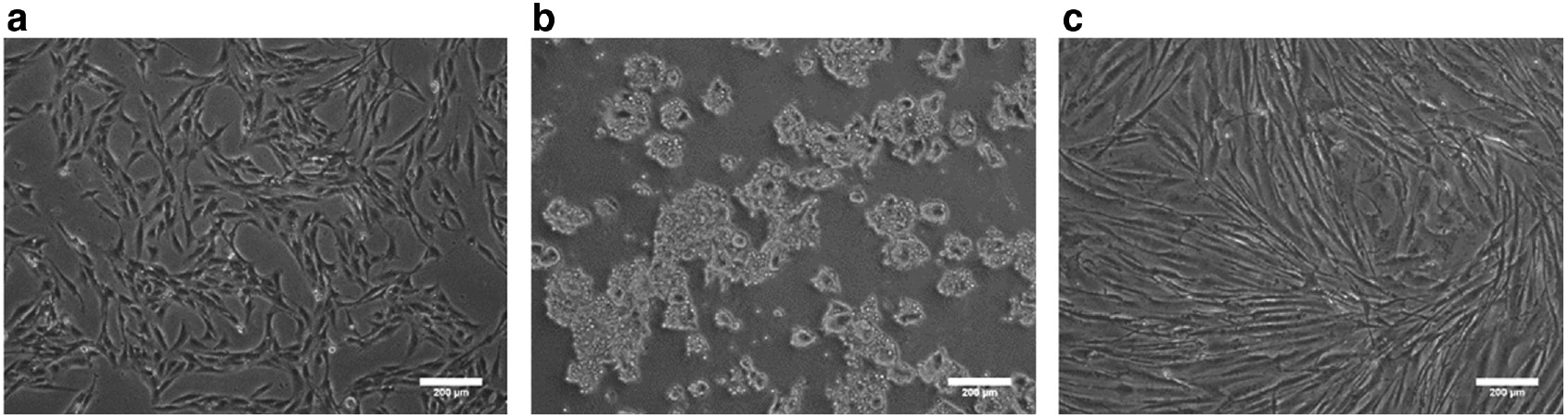

Figure 2 shows 3A6, SW620, and Hs68 cells successfully attached and proliferated on TCPS at day 3 after seeding. Both 3A6 and Hs68 cells exhibited the spindle morphology. SW620 exhibited the typical epithelial cell shape with round morphology.

Optical images of cells on TCPS. (a) Mesenchymal-derived stem cells 3A6. (b) Cancer cells SW620 (c) Fibroblasts Hs68. Scale bar=200 μm.

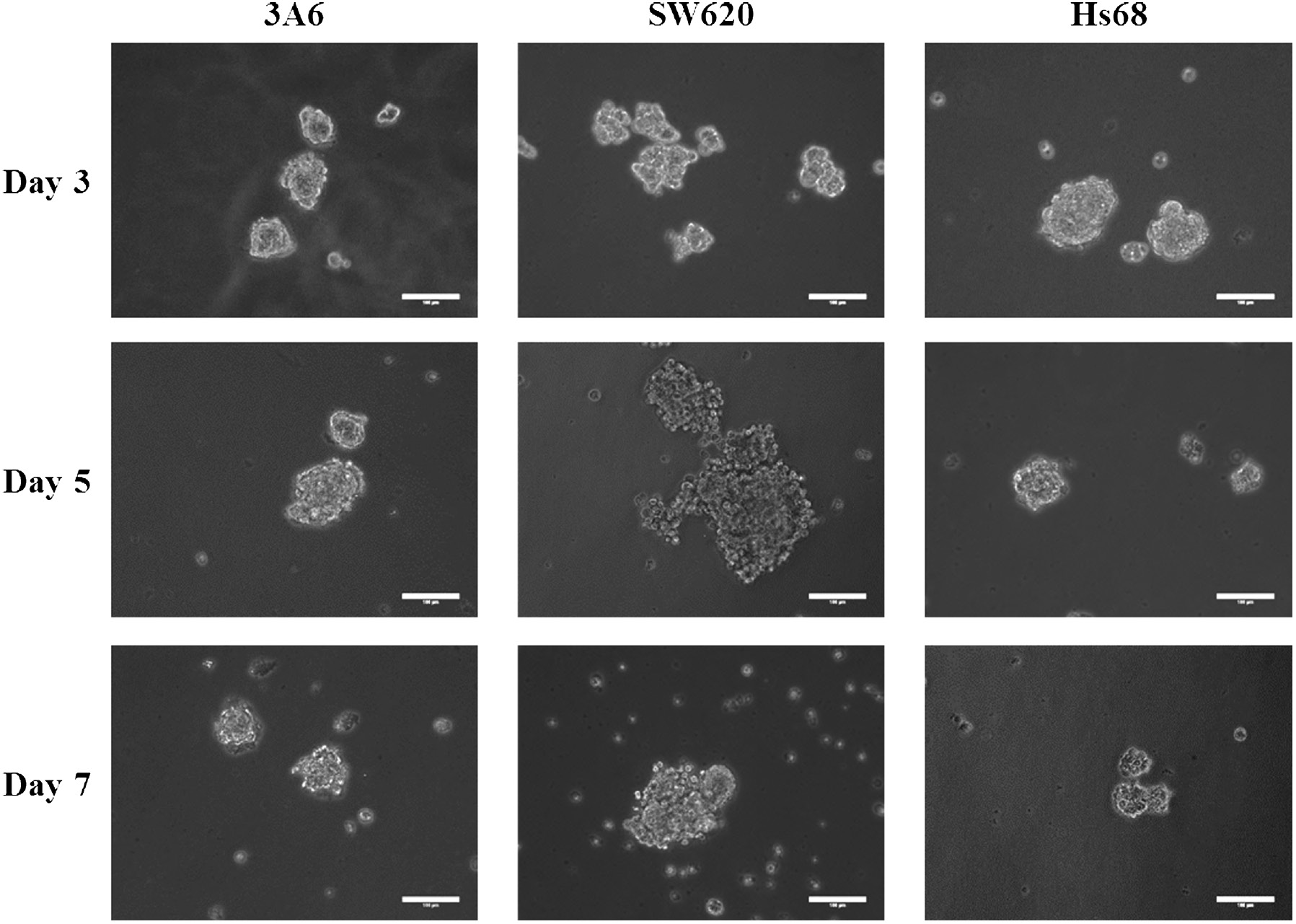

Figure 3 shows morphologies of 3A6, SW620, and Hs68 cells cultured on a chitosan-coated surface for 3, 5, and 7 days. Consistent with previous studies [27], [36], [40], almost all cells could suspend and form aggregates spontaneously. This indicates that the cell–cell distance of traditional cultures on TCPS was obviously greater than that of a suspension culture on chitosan-coated surfaces. The average spheroid size is shown in Table 1. The size of Hs68 cell spheroid decreased with culture time, while SW620 and 3A6 spheroids had the largest size on the fifth day. In these spheroids, SW620 could aggregate the largest spheroids on the fifth day.

Optical images of cell spheroids on chitosan-coated surfaces during a 7-day cultured period. Scale bar=100 μm.

Diameters of multicellular spheroids on chitosan-coated surfaces during 7-day cultured period.

| Culture time (days) | Diameter (μm) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 3A6 | SW620 | Hs68 | |

| 3 | 69.60±15.50 | 79.88±21.31 | 99.63±26.91 |

| 5 | 96.08±27.91 | 143.12±54.31 | 67.73±22.86 |

| 7 | 70.34±17.06 | 125.93±75.73 | 56.29±20.44 |

n>20.

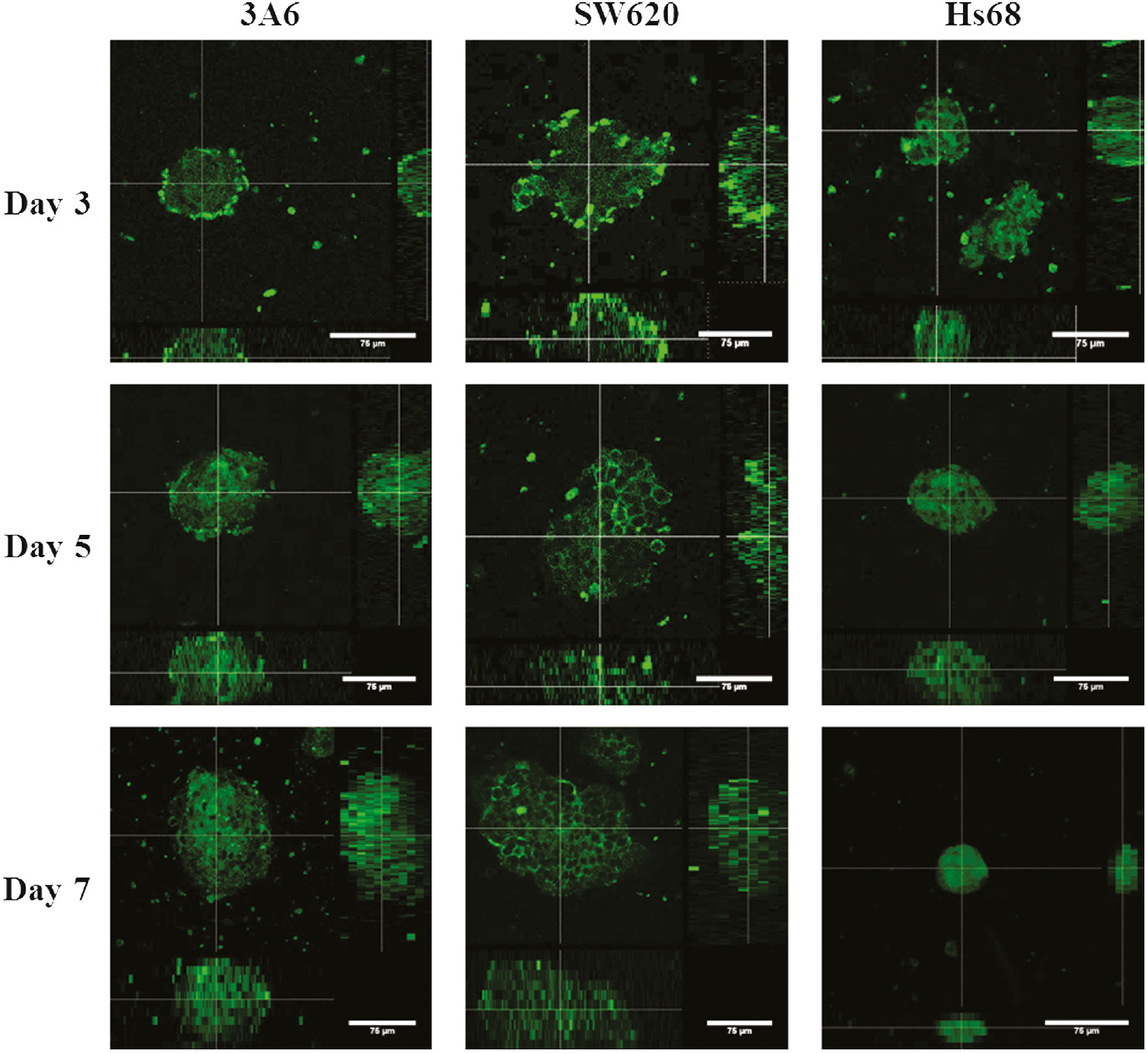

CD44 expressions of cell spheroids

CD44 proteins participate in many cellular processes, which include the regulation of growth, survival, differentiation, and motility [41], [42], [43], [44], [45]. Especially, CD44 protein is the common surface marker of MSCs and cancer cells [1], [2], [3], [4], [8], [9], [10], [11], so we assessed the surface antigen CD44 expression of MSCs and cancer cells by confocal microscopy after the cells were cultured on chitosan-coated surfaces for 3, 5, and 7 days. As shown in Fig. 4, overall multicellular spheroids were stained with the CD44 antibody. Thus, the flow cytometry was further used to quantitatively analyze the expression of CD44 in monolayer cells on TCPS and spheroid-derived cells on chitosan-coated surfaces.

Confocal immunofluorescence images of CD44 expressions of cell spheroids on chitosan-coated surfaces during a 7-day cultured period. The center images are the xy planes, and the images below and right are xz and yz planes. Scale bar=75 μm.

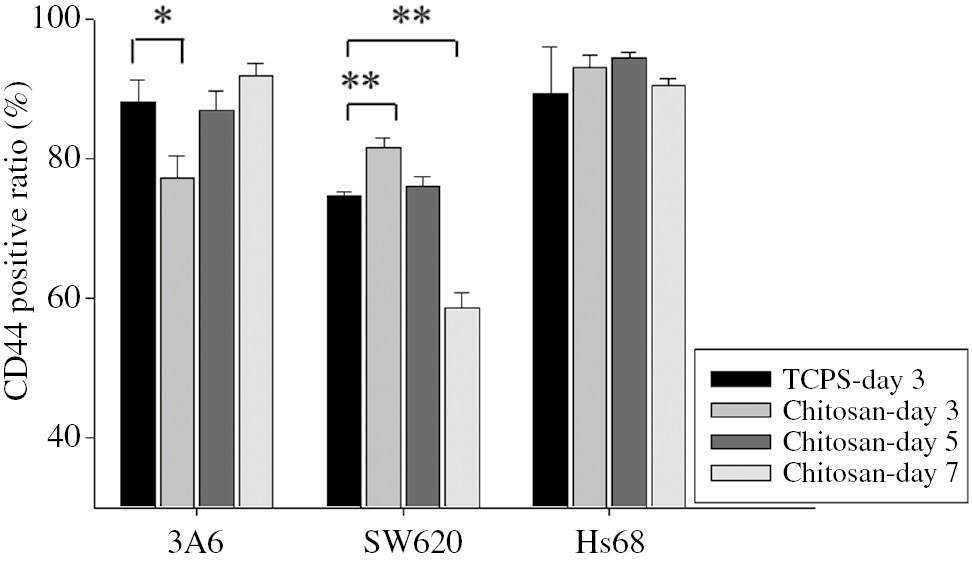

Fibroblasts were included in this study because they are well differentiated and stable. As shown in Fig. 5, there was no significant change in the CD44 expression of Hs68 cells, regardless of substrates or culture period. For 3A6 and SW620 cells, they exhibited the different tendencies for the CD44 expression. After having the cells cultured on chitosan-coated surfaces for 3 days, the CD44 expressions of 3A6 and SW620 cells in the spheroids were less and more than that on TCPS, respectively. On further culture, the CD44 expression of 3A6 and SW620 cells in the spheroids increased and decreased with culture time, respectively. On the 7th day, the CD44 expressions of 3A6 and SW620 cells in the spheroids have been more and less than that on TCPS, respectively. Thus, the CD44 expression of 3A6 and SW620 cells in the spheroids were dynamic and totally different.

CD44 expressions of multicellular spheroids on chitosan-coated surfaces during a 7-day cultured period. The positive ratios of CD44 expression were determined by flow cytometry. n=3, ∗p<0.05, ∗∗p<0.01.

CD44 expressions of cells in different cultured environments

Subsequently, various culture environments were established to investigate how chitosan-coated surfaces affected the CD44 expressions of cell spheroids. Major differences between cells cultured on TCPS and chitosan-coated surface were considered in this study, such as cell–cell distance, hypoxia/starvation, and the effect of chitosan itself.

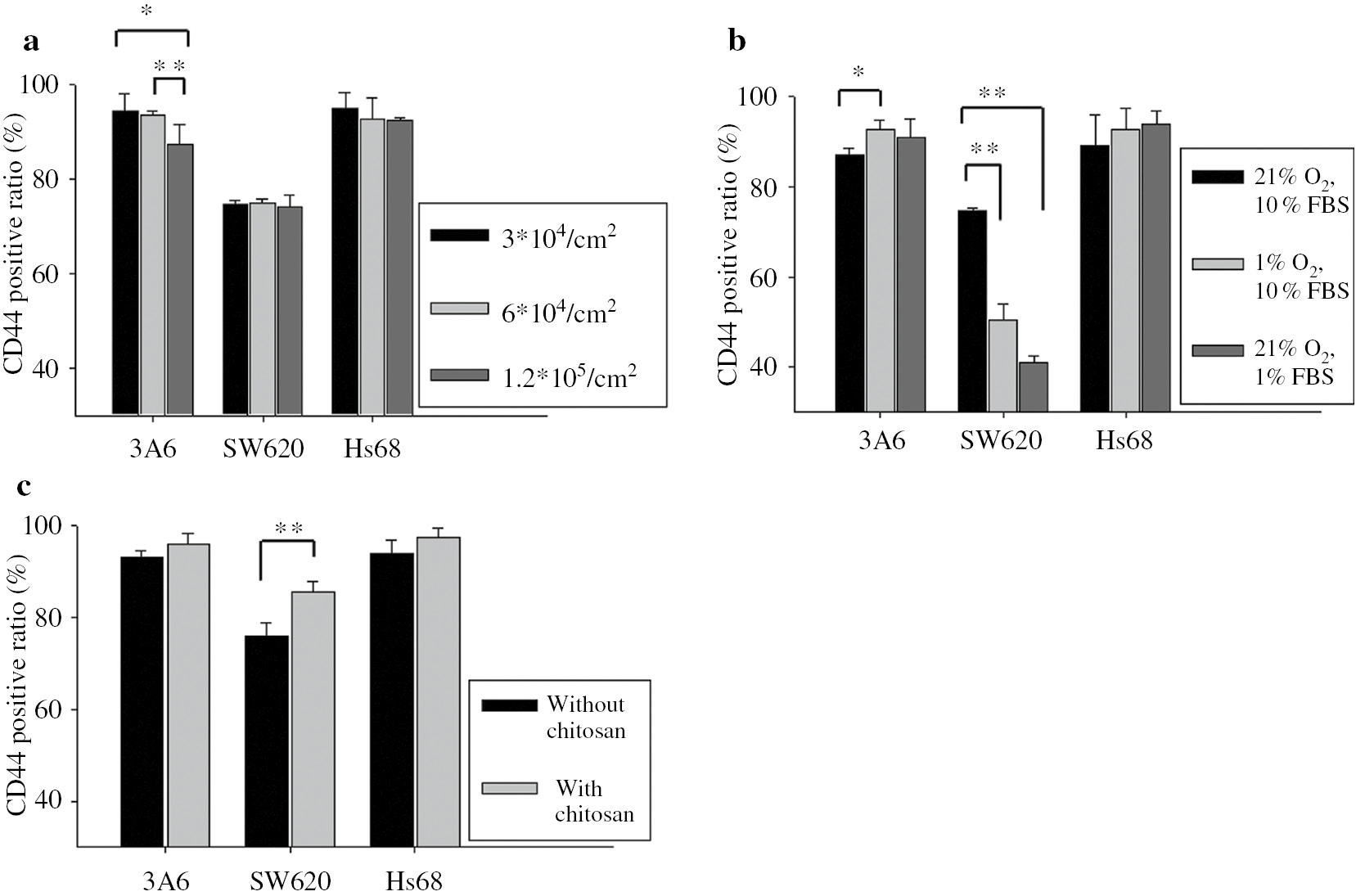

When cells were cultured on TCPS, the cells grew in a 2D environment and the cell–cell distance was obviously greater than that of cells being aggregated into multicellular spheroids. To simulate compact cell contact within cellular spheroids, we increased the seeding density for cells cultured on TCPS to decrease the cell–cell distance. Figure 6a shows the CD44 expression of 3A6 cells decreased with increasing seeding density (p<0.05 and p<0.01), while in the cases of SW620 and Hs68 cells, CD44 expression remained stationary. The differentiation of stem cells has been reported to be greatly regulated by their niche [46]. If mesenchymal stem cells can aggregate closer and communicate well with each other, it would greatly improve differentiation capability [31], [34]. Therefore, the 3D spheroid structure with high aggregation degree provided 3A6 cells with the tendency to differentiate so the CD44 expression of 3A6 cells significantly decreased at high seeding density after 3 days of culture.

CD44 expressions of cells cultured with different environments on TCPS. Cells were cultured (a) with different seeding densities. (b) with hypoxia and starvation. (c) with and without chitosan solution-added medium. The positive ratios of CD44 expression were determined by flow cytometry at 3-day culture. n=3, ∗p<0.05, ∗∗p<0.1.

In addition to reducing the cell–cell distance, the dense spheroid structure developed hypoxia and starvation at distances beyond the diffusion capacity of oxygen and nutrients [47]. Recently, low oxygen levels have been proposed to extensively affect cell behaviors [48]. Thus, the concentrations of oxygen and serum were decreased for cells cultured on TCPS to simulate the microenvironment of multicellular spheroids. As shown in Fig. 6b, the CD44 expression of 3A6 cells increased when the concentrations of oxygen (p<0.05) and serum were reduced on TCPS. However, the CD44 expressions of SW620 cells significantly decreased with low oxygen and nutrient levels (p<0.01). Therefore, a spheroid structure with a high aggregation degree provided hypoxia and a starvation environment for 3A6 and SW620 cells to exhibit opposite CD44 expressions, especially for cells within spheroids after a longer culture period.

It is likely that the effects of chitosan-coated surface on the CD44 expression of 3A6 and SW620 cells stem from its interaction with cells, or specific proteins and then to interact with cells for desired functions. Actually, chitosan is able to interact with many proteins, which is important in mediating cell and tissue responses [39], [49]. Therefore, chitosan was directly added into the cultured medium for cells cultured on TCPS. Obviously, Fig. 6c shows the CD44 expression of SW620 cells increased when cells were cultured in chitosan-added medium (p<0.01), suggesting chitosan played an important role in inducing the higher CD44 expression of SW620 cells on a chitosan-coated surface after 3 days of culture. On the other hand, the expression of CD44 for 3A6 cells did not significantly change in the presence of chitosan. Therefore, the reason for the lower CD44 expression of 3A6 cells on chitosan-coated surface after 3 days of culture may be the compact cell contact within the cellular spheroids (Fig. 6a).

For organism, there are various kinds of cells with varied morphologies and functions in the body that cooperate to maintain life. In this study, it has been confirmed that fibroblasts were relatively stable when cultured on different substrates and environments. However, MSCs and cancer cells were easily affected by environment factors to exhibit the different tendencies of protein expressions. These results indicated that responses of different kinds of cells should be taken into consideration simultaneously when biomaterials were implanted into the body for further applications. Therefore, we investigated and compared the effect of chitosan on CD44 expressions of 3A6, SW620, and Hs68 cells simultaneously in this study. The advantage of chitosan is that it is capable of establishing a suspension culture model to develop multicellular spheroids, which mimics in vivo 3D environment. Notably, CD44 expression on 3A6 and SW620 cells was dynamic and diverse so it is not suitable for observing the interaction between biomaterials and cells in vitro at a specified cultured time. In other words, the evaluation of biomaterials should be more cautious. Furthermore, many factors such as cell–cell distance, hypoxia/starvation, and the effect of chitosan itself in a 2D environment was designed to figure out how to regulate CD44 expression of 3A6 and SW620 cells in 3D environment. Interestingly, the complex responses of 3A6 and SW620 cells in multicellular spheroids could be delineated by the interactions between cell and cell, cell and chitosan, as well as cell and the microenvironment. Based on these data, the cell behaviors were regulated not only by the chitosan properties but also by many other factors. This indicates that more factors and aspects should be well considered when analyzing the interaction between the biomaterials and cells, which would help us to use biomaterials and regulate cells precisely.

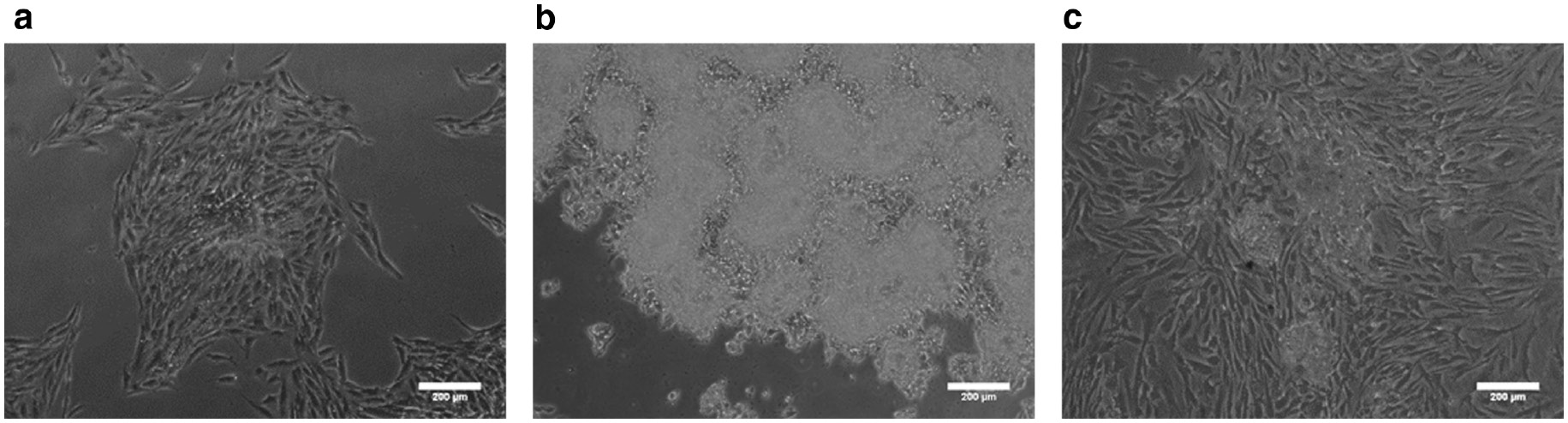

Finally, upon seeding cell spheroids back to TCPS, Fig. 7 shows that cells could attach to TCPS and migrate out from the spheroids. This suggested cells were could be cultured and regulated for further tissue engineering applications.

Optical images of reseeding cells on TCPS. Cells cultured on chitosan-coated surfaces for 3 days and reseeded to TCPS for 3 days. (a) 3A6. (b) SW620. (c) Hs68. Scale bar=200 μm.

Conclusion

In summary, CD44 expression of Hs68 cells was stable while 3A6 and SW620 cells were dynamic and exhibited the different tendencies for the CD44 expression when they were in the aggregated state suspended on chitosan. A biomaterial might contact various kinds of cells in the body to induce different cell responses, so the biomaterial must be carefully evaluated for potential clinical applications. In the future, more studies will be conducted to understand and verify the interaction between chitosan and cells, which would help us to use adequate cultured conditions to control cell behaviors in the application of cell therapy.

Article note:

A collection of invited papers based on presentations at the 12th Conference of the European Chitin Society (12th EUCHIS)/13th International Conference on Chitin and Chitosan (13th ICCC), Münster, Germany, 30 August–2 September 2015.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the staff of the Imaging Core, and the Flow Cytometric Analyzing and Sorting Core at the First Core Labs, National Taiwan University College of Medicine, for technical assistance. The authors also thank the Ministry of Science and Technology of the Republic of China for their financial support.

References

[1] D. H. Lee, S. D. Joo, S. B. Han, J. Im, S. H. Lee, C. H. Sonn, K. M. Lee. Connect Tissue Res.52, 226 (2011).10.3109/03008207.2010.516850Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[2] S. K. Both, A. J. van der Muijsenberg, C. A. van Blitterswijk, J. de Boer, J. D. de Bruijn. Tissue Eng.13, 3 (2007).10.1089/ten.2005.0513Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[3] J. H. Sung, H. M. Yang, J. B. Park, G. S. Choi, J. W. Joh, C. H. Kwon, J. M. Chun, S. K. Lee, S. J. Kim. Transplant Proc.40, 2649 (2008).10.1016/j.transproceed.2008.08.009Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[4] T. L. Ramos, L. I. Sanchez-Abarca, S. Muntion, S. Preciado, N. Puig, G. Lopez-Ruano, A. Hernandez-Hernandez, A. Redondo, R. Ortega, C. Rodriguez, F. Sanchez-Guijo, C. Del Canizo. Cell Commun. Signal14, 2 (2016).10.1186/s12964-015-0124-8Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[5] R. Pardal, M. F. Clarke, S. J. Morrison. Nat. Rev. Cancer3, 895 (2003).10.1038/nrc1232Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] N. Kobayashi, N. Navarro-Alvarez, A. Soto-Gutierrez, H. Kawamoto, Y. Kondo, T. Yamatsuji, Y. Shirakawa, Y. Naomoto, N. Tanaka. Cell Transplant17, 19 (2008).10.3727/000000008783906982Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[7] T. Reya, S. J. Morrison, M. F. Clarke, I. L. Weissman. Nature414, 105 (2001).10.1038/35102167Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] S. Takaishi, T. Okumura, S. Tu, S. S. Wang, W. Shibata, R. Vigneshwaran, S. A. Gordon, Y. Shimada, T. C. Wang. Stem Cells27, 1006 (2009).10.1002/stem.30Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[9] P. Dalerba, S. J. Dylla, I. K. Park, R. Liu, X. Wang, R. W. Cho, T. Hoey, A. Gurney, E. H. Huang, D. M. Simeone, A. A. Shelton, G. Parmiani, C. Castelli, M. F. Clarke. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA104, 10158 (2007).10.1073/pnas.0703478104Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[10] M. Zoller. Nat. Rev. Cancer11, 254 (2011).10.1038/nrc3023Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] L. Du, H. Wang, L. He, J. Zhang, B. Ni, X. Wang, H. Jin, N. Cahuzac, M. Mehrpour, Y. Lu, Q. Chen. Clin. Cancer Res.14, 6751 (2008).10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1034Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] L. Ricci-Vitiani, D. G. Lombardi, E. Pilozzi, M. Biffoni, M. Todaro, C. Peschle, R. De Maria. Nature445, 111 (2007).10.1038/nature05384Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[13] T. M. Elsaba, L. Martinez-Pomares, A. R. Robins, S. Crook, R. Seth, D. Jackson, A. McCart, A. R. Silver, I. P. Tomlinson, M. Ilyas. PLoS One5, e10714 (2010).10.1371/journal.pone.0010714Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[14] X. Fan, N. Ouyang, H. Teng, H. Yao. Int. J. Colorectal Dis.26, 1279 (2011).10.1007/s00384-011-1248-ySearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[15] V. R. Sinha, A. K. Singla, S. Wadhawan, R. Kaushik, R. Kumria, K. Bansal, S. Dhawan. Int. J. Pharm.274, 1 (2004).10.1016/j.ijpharm.2003.12.026Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[16] H. S. Kas. J. Microencapsul.14, 689 (1997).10.3109/02652049709006820Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[17] A. K. Singla, M. L. Sharma, S. Dhawan. Biotech. Histochem.76, 165 (2001).10.1080/bih.76.4.165.171Search in Google Scholar

[18] Y. Kato, H. Onishi, Y. Machida. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol.4, 303 (2003).10.2174/1389201033489748Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[19] C. Shi, Y. Zhu, X. Ran, M. Wang, Y. Su, T. Cheng. J. Surg. Res.133, 185 (2006).10.1016/j.jss.2005.12.013Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[20] Y. H. Chen, Y. C. Chung, I. J. Wang, T. H. Young. Biomaterials33, 1336 (2012).10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.10.048Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[21] C. Chatelet, O. Damour, A. Domard. Biomaterials22, 261 (2001).10.1016/S0142-9612(00)00183-6Search in Google Scholar

[22] Y. H. Chen, S. H. Chang, I. J. Wang, T. H. Young. Biomaterials35, 9247 (2014).10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.07.025Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[23] T. L. Yang, T. H. Young. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun.381, 466 (2009).10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.10.116Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[24] S. J. Lin, S. H. Jee, W. C. Hsaio, S. J. Lee, T. H. Young. Biomaterials26, 1413 (2005).10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.05.002Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[25] P. Verma, V. Verma, P. Ray, A. R. Ray. In Vitro Cell. Dev. Biol. Anim.43, 328 (2007).10.1007/s11626-007-9045-1Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[26] G. S. Huang, L. G. Dai, B. L. Yen, S. H. Hsu. Biomaterials32, 6929 (2011).10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.05.092Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[27] C. W. Tsai, Y. T. Kao, I. N. Chiang, J. H. Wang, T. H. Young. PLoS One10, e0140747 (2015).10.1371/journal.pone.0140747Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[28] T. J. Bartosh, J. H. Ylostalo, A. Mohammadipoor, N. Bazhanov, K. Coble, K. Claypool, R. H. Lee, H. Choi, D. J. Prockop. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA107, 13724 (2010).10.1073/pnas.1008117107Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[29] G. Benton, J. George, H. K. Kleinman, I. P. Arnaoutova. J. Cell. Physiol.221, 18 (2009).10.1002/jcp.21832Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[30] G. Benton, H. K. Kleinman, J. George, I. Arnaoutova. Int. J. Cancer128, 1751 (2011).10.1002/ijc.25781Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[31] J. E. Frith, B. Thomson, P. G. Genever. Tissue Eng. Part C Methods.16, 735 (2010).10.1089/ten.tec.2009.0432Search in Google Scholar

[32] A. Sadlonova, Z. Novak, M. R. Johnson, D. B. Bowe, S. R. Gault, G. P. Page, J. V. Thottassery, D. R. Welch, A. R. Frost. Breast Cancer Res.7, R46 (2005).10.1186/bcr949Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[33] S. K. Singh, I. D. Clarke, M. Terasaki, V. E. Bonn, C. Hawkins, J. Squire, P. B. Dirks. Cancer Res.63, 5821 (2003).Search in Google Scholar

[34] W. Wang, K. Itaka, S. Ohba, N. Nishiyama, U. I. Chung, Y. Yamasaki, K. Kataoka. Biomaterials30, 2705 (2009).10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.01.030Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[35] H. Y. Yeh, B. H. Liu, S. H. Hsu. Biomaterials33, 8943 (2012).10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.08.069Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[36] N. C. Cheng, S. Wang, T. H. Young. Biomaterials33, 1748 (2012).10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.11.049Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[37] Y. J. Huang, S. H. Hsu. Biomaterials35, 10070 (2014).10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.09.010Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[38] C. C. Tsai, C. L. Chen, H. C. Liu, Y. T. Lee, H. W. Wang, L. T. Hou, S. C. Hung. J. Biomed. Sci.17, 64 (2010).10.1186/1423-0127-17-64Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[39] T. L. Yang, L. Lin, Y. C. Hsiao, H. W. Lee, T. H. Young. Tissue Eng. Part A18, 2220 (2012).10.1089/ten.tea.2011.0527Search in Google Scholar

[40] Y. H. Chen, I. J. Wang, T. H. Young. Tissue Eng. Part A15, 2001 (2009).10.1089/ten.tea.2008.0251Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[41] H. Ponta, L. Sherman, P. A. Herrlich. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol.4, 33 (2003).10.1038/nrm1004Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[42] Y. S. Park, J. W. Huh, J. H. Lee, H. R. Kim. Oncol. Rep.27, 339 (2012).10.3892/or.2012.1642Search in Google Scholar

[43] V. Trochon, C. Mabilat, P. Bertrand, Y. Legrand, F. Smadja-Joffe, C. Soria, B. Delpech, H. Lu. Int. J. Cancer66, 664 (1996).10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19960529)66:5<664::AID-IJC14>3.0.CO;2-4Search in Google Scholar

[44] E. Mylona, K. A. Jones, S. T. Mills, G. K. Pavlath. J. Cell. Physiol.209, 314 (2006).10.1002/jcp.20724Search in Google Scholar

[45] A. L. Lazaar, S. M. Albelda, J. M. Pilewski, B. Brennan, E. Pure, R. A. Panettieri, Jr. J. Exp. Med.180, 807 (1994).10.1084/jem.180.3.807Search in Google Scholar

[46] F. M. Watt, B. L. Hogan. Science287, 1427 (2000).10.1126/science.287.5457.1427Search in Google Scholar

[47] M. G. Nichols, T. H. Foster. Phys. Med. Biol.39, 2161 (1994).10.1088/0031-9155/39/12/003Search in Google Scholar

[48] J. Mathieu, Z. Zhang, W. Zhou, A. J. Wang, J. M. Heddleston, C. M. Pinna, A. Hubaud, B. Stadler, M. Choi, M. Bar, M. Tewari, A. Liu, R. Vessella, R. Rostomily, D. Born, M. Horwitz, C. Ware, C. A. Blau, M. A. Cleary, J. N. Rich, H. Ruohola-Baker. Cancer Res.71, 4640 (2011).10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-3320Search in Google Scholar

[49] J. B. Lopes, L. A. Dallan, L. F. Moreira, S. P. Campana Filho, P. S. Gutierrez, L. A. Lisboa, S. A. de Oliveira, N. A. Stolf. Ann. Thorac. Surg.90, 566 (2010).10.1016/j.athoracsur.2010.03.086Search in Google Scholar

©2016 IUPAC & De Gruyter. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. For more information, please visit: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- In this issue

- Preface

- 12th International Conference of the European Chitin Society and 13th International Conference on Chitin and Chitosan (EUCHIS/ICCC 2015)

- Conference papers

- CD44 expression trends of mesenchymal stem-derived cell, cancer cell and fibroblast spheroids on chitosan-coated surfaces

- Bioactive chitosan based coatings: functional applications in shelf life extension of Alphonso mango – a sweet story

- Commercial cellulases from Trichoderma longibrachiatum enable a large-scale production of chito-oligosaccharides

- Hydrolysis of chitin and chitosan in low temperature electron-beam plasma

- Production of chitosan oligosaccharides for inclusion in a plant biostimulant

- New insights into the nature of the Cibacron brilliant red 3B-A – Chitosan interaction

- Co-assembly of chitosan and phospholipids into hybrid hydrogels

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- In this issue

- Preface

- 12th International Conference of the European Chitin Society and 13th International Conference on Chitin and Chitosan (EUCHIS/ICCC 2015)

- Conference papers

- CD44 expression trends of mesenchymal stem-derived cell, cancer cell and fibroblast spheroids on chitosan-coated surfaces

- Bioactive chitosan based coatings: functional applications in shelf life extension of Alphonso mango – a sweet story

- Commercial cellulases from Trichoderma longibrachiatum enable a large-scale production of chito-oligosaccharides

- Hydrolysis of chitin and chitosan in low temperature electron-beam plasma

- Production of chitosan oligosaccharides for inclusion in a plant biostimulant

- New insights into the nature of the Cibacron brilliant red 3B-A – Chitosan interaction

- Co-assembly of chitosan and phospholipids into hybrid hydrogels