Abstract

With reference to Steven Feld’s “acoustemology,” his epistemology of sounding and listening, developed in the Bosavi Rainforest in Papua New Guinea, where the trees are too dense to afford a distant view and meaning has to be found up close, on the body with other human and more-than-human bodies, this essay deliberates how sound knows in entanglements and from the in-between: in a being with as a knowing with rather than from a distance. In this way, this essay, from the densities of the rainforest, critiques Western knowledge and its reliance on visual categories, straight lines, and universalising principles that pretend objectivity and a distant view. Instead, it turns to the relational indivisibility of sound that lets us hear interdependencies and confronts us with the invisible of which we are part. In conclusion, it proposes that sound studies as applied, transversal studies enable such a paradigm shift that at once reveals what hegemonic knowledge strands exclude and invites a different dialogue from the in-between of everything.

1 Introduction: Sonic “Knowledge Values”

This essay is the revised version of a talk given in the context of the PhD and postdoctoral course and conference “Dialogue and the Art of Listening.”[1] This was a verbal, non-written, talk, and the aim of this essay is to keep some of the verbal elasticity and freedom within its writing, to establish an equally direct address and sonic sense through the text. Therefore, its objective is not to produce a deductive argument nor a comprehensively referenced text that develops the relationship of its theme to existing historical and contemporary theories. Instead, the idea is to think about the subject of art and listening in a practice-based dialogue, contingent, and exploratory, open for application across the disciplines present at this conference and beyond.

The quasi-verbal, performed approach runs deliberately counter the “rules” of contemporary philosophy as identified by Alexander Jeuk in his insightful piece written for Philosophy Now, “What Happened to Philosophy?”, in that it does not foreground existing “literature” or “debates,” and does not try to argue for novelty value. Instead, it proposes a philosophical practice of exploration through systematic thinking: a thinking through the relationality of the phenomenon under discussion in its experienced and applied complexity.[2] This does not represent a disregard for other scholarship, an ignorance of its import and influence. But is an attempt to practice rather than demonstrate philosophical thinking as a resource and strategy for doing research across disciplines.

In this spirit, what I hoped to introduce and advocate for in the talk was an interdisciplinary listening that applies sound studies in a practical theorising critical of knowledge universals and their epistemic reduction. Accordingly, my intention for this essay is to focus on the phenomenon rather than the literature under discussion and work from the experience of sound into scholarship. The suggestion is that the sonic, as material and concept, generates and endorses sensory knowledge possibilities, which can contribute to knowing across various disciplines. Sound as sonic thinking and doing can augment and add to every discipline and field of study, and it can bring new knowledge methods and methodologies to a broader readership, who will engage in this written and edited version of the talk from their own field.

To start, I want to draw attention to the suitcase in the image above (Figure 1). This is my thinking prop. It’s a performative device and a tool to agitate cross-disciplinary and practice-based studies from sound. But it’s not a gimmick. Instead, it is the mobile and “undisciplinary” dimension of my working with the auditory. It denotes an unreliable location, a passing methodology, and hints at the plural conditions of what we travel with, where to and from. In that sense, it represents an access point to sonic fictions that might reassess the fictions of science, their hegemony, measurability, and linearity, and instead bring something of a disorganised, disorderly, and non-classifiable force to knowledge and how we think the world.

Image of suitcase for itinerant transversal sound studies ©Salomé Voegelin.

I will start and then also end on this suitcase as it helps to imagine and use sound as a tool and device for research and scholarship; to open new ways of working and thinking through its hybridity, its cross-disciplinary materialisation, and its ability to make audible passing, relational, embodied, and contingent realities. These are the possible realities of the world and of scholarship that remain invisible and excluded from a conventional, discipline-bound (visual) knowledge scheme, but are thinkable through the indivisible dimensionality of sound, which provides an important access point to the complex interdependencies of knowledge and the world.

The suitcase allows me to make a conceptual but also an operational place for this endeavour. It helps me to make up for the relative lack of sound’s inclusion and framing in conventional academic work and disciplines, by performing its mobile institution with a metal handle and faux leather walls. Because, as we know anecdotally and through our own work and research, such a thinking and doing across disciplines from sound exists. There are many practitioners and theorists who generate and pursue sonic thinking and auditory methodologies within and from their various disciplinary working and research in the humanities as well as in the natural sciences.[3] However, more often than not, these more-than- and un-disciplinary ventures into sound are dependent on a singular researcher, whose retirement presents the end to a particular approach, courses get closed and the resulting void is quickly filled again by conventional visual teaching, learning, and researching. Or alternatively, the sonic is not actually listened to and taken into account as sound, but is transposed into data and visualised for scientific purposes, or read in relation to musicological (score-based) or cultural and semantic (language-based) schemes.[4] Either way, sound is unable to bring its “knowledge value” permanently and regularly to the institution of learning, teaching, and knowledge, to perform a sustainable impact on research and teaching as well as on interdisciplinarity.

In other words, sound is not (yet) commonly represented in the curriculum or in methodological schemata. And maybe it should never be established in the curriculum, but needs to keep on troubling it, pulling on its disciplinary lines and challenging its dominant visuality and commensurate singular knowledge frame. However, its absence, or temporary and person-dependent presence, means its experiential and material insights have to be retraced and reperformed all the time. They remain quasi-oral and embodied in their delivery and legacy. Such a contingent approach fails to gain traction within a visual, canonical, and foundational knowledge system. Thus, its methods and approaches lose out on funding and the opportunities afforded to those approaches that work within a recognisable and established category. However, rather than bemoaning the difficulty experienced when trying to convince funders and institutions of the value of sound’s relational logic and invisible materialisation for how we think the world, I mean to focus on the benefits of its troubling demands. Thus, I embrace its anecdotal, not entirely established but always emerging position as it evidences sound’s potential to be more mobile and fluid, to move between disciplines, to think relationally and build hybrid connections, unencumbered by an objective view and by what is right and appropriate within the expectations of one discipline, the canon, and scientific history.

It is for these reasons that I have chosen a suitcase as a device to practice and perform an itinerant and anecdotal curriculum for sound. The suitcase stands historically in reference to works such as Alexander Calder’s Circus (1926–1931) and Marcel Duchamp’s Boîte-en-valise (1935–1941), taking on their playful anarchy and institutional critique. More contemporaneously it is aware of works such as Unpacked by Mohamad Hafez and Ahmed Badr from 2017, where suitcases hold, model, and narrate the memory of middle-eastern refugees, and thus communicate a different narrative knowledge of war, geography, and power.[5] And it is mindful also of Yhonnie Scarce who uses the suitcase as a means to bring her ancestors and thus their knowledge along on her travels, declaring them her royal family as opposed to the British coloniser’s royal family. “As far as I’m concerned my grandparents, great grandparents and those people who walked my Country before me, are Australia’s royalty.”[6]

Within these references, the suitcase holds the potential for other knowledge and thus for other political narratives and inspires performance. It invites a telling and retelling, a bringing along, and a taking back. It questions fixed and singular knowledge strands, as well as singular lines and directions of travel, and initiates engagement and exchange. In that sense, it brings the notion of visitation, migration, and reciprocity to knowledge, and functions as a thought device for understanding a relational and mobile actuality.

This talk, which you read here as an essay, is part of this performance. It is part of my travels through Europe, with this suitcase, performing as an itinerant saleswoman for transversal sound studies to challenge and ask, advocate, and practice sound’s knowledge across disciplines.

How does sound travel? How does sound connect? How does sound produce knowledge?

To elaborate on these questions, I want to talk about sonic epistemology, sonic knowledge, and sonic knowing, as a relational practice and troubling factor. Something that does not represent conventional methods and aims, that doesn’t produce knowledge categories, and that challenges grand universals and the expectations and certainties they set up. In particular, the sonic challenges terms such as objectivity, a position that is apparently ensured by distance and enabling of quantification but whose measure relies on a cultural visuality, on the means and belief to see separate entities from afar. By contrast, sound denies distance. I always hear on my body however far away the source of a sound might be. I hear the distance as a sonic interval, close-up. Because I do not hear the source but its sounding with everything: the environment, the weather, the air density, the human, and more-than-human bodies it passes through and vibrates with. And thus sound, when it is not reduced, visualised, or transposed into language or data, and when it is not simply misunderstood as source, but when it remains what I call “direct” sound, what is heard, disables the possibility of distance that science demands and that Western, US–EU modernist research associates with veracity and truth. Instead, it offers something else, a view on the relational, the in-between, and the entangled, which its experience makes accessible and through which it augments and transforms how and what we think we see.

But if, from the relationality and proximity of sound, we dispel the fiction that distance provides objectivity, a measurable perception, and thus a knowledge protected from the vagaries of the body, as well as from the uncertain contingency of positionalities and orientations, what becomes of science?

Whose body becomes visible as the agent of science’s fiction of distance? Whose body measures it? Whose body controls and naturalises itself tautologically through its measure?

These are questions that demonstrate that a focus on the relational, established through sound can serve as a radical pluralising device, whose radicality describes its ability to make possible worlds, i.e. the world in its plurality, thinkable. And it can represent a starting point to re-insert the body of human and more-than-human beings into scholarship and thus into knowledge. In this way, a directly perceived sound, a sound that is not transposed into a visual system, at once reveals the visuo-normative organisation of seeing and measuring the world, and challenges its hegemonic dogma about the way the world can be.[7] Instead of confirming its singularity, sound makes temporary, invisible, and relational realities accessible, which, in listening with – performing sound’s connecting logic – we inhabit in plural ways, and which we extend into their consequences by how we inhabit them. Thus, the critical radicality of sound is not inherent but performed. It brings the body as equally sonic possible and impossible bodies into the frame of scholarship: “performing the body from its invisible slices, from the variants of a present body that is not within the paternal law or the biomedical imagery of a normative science, but unperforms them.”[8]

Sound’s possible worlds and possible bodies can provide tools for a discussion and practice of feminist and decolonial knowledges, and it represents a means to ponder and pursue, within our own limitations of being human, posthumanist knowledge possibilities.

1.1 Listening

In the context of this essay, listening is understood as dialogue, as conversation, which outlines it as a sensory-motor action in relation to sounding and a reciprocal vis-à-vis rather than as a passive and solitary reception. “Listening” is an ubiquitous term.[9] It is a word that gets talked about a lot and that we’re currently searching definitions for. And maybe already in this searching for a definition or description we are making a mistake or we’re potentially looking at that which listening doesn’t do, which is the definable. Instead, maybe listening remains a doubtful process that escapes definition and finds words and scientific thinking not through vocabularies but in a contingent praxis. In this way, it might enter into knowledge discourse not to provide categories and classifications, but as a more “mythical” practice of accessing and thus thinking about the world from the invisible and the relational, where things come to appear differently, in different chronologies, spatialities, and references. In that sense listening stands as a vestige of the pre-enlightenment, as a “gothic curiosity” that challenges those aspects of rationality which were gained by excluding rather than working with the uncertain.

Listening in the sense of such a quasi-gothic conjuring practice is not about congealing something into recognition or getting something into a structure. It is not a reading of the world, where the ears are pressed into the service of eyes and of theory, and where the aim is a structuralist organisation in lines and frames, words and grammar. Instead, it is a practice that does not see lines, that does not hear frames but porous relationalities; whose ears are expanded across the body; and whose dialogue is embodied, unreliable, made of the stutters and breath of its posthuman, unboundaried form.[10]

Crucially, the mythical is not a flippant or trivial, “feminine” association between sound and irrationality. Instead, it performs the necessary “madness” of other possibilities and even impossibilities: all the other ways the world, bodies, matter, and scholarship can be. In that sense, the mythical is a transformative force and a deliberate critique of a US–EU rationality and scientism, which pursue a visual, quantifiable organisation, and finally colonisation and extraction of the world as a singular place. By contrast, listening, in its direct and gothic practice, unperforms the trajectory of prescriptive referencing, and demands of scholarship not to separate experience from theoretical discussion, but to understand the force of their continuity and reciprocity. It does not present a position against scholarship but performs a scholarship based on experience in its complexity rather than through literature and reference. This is exactly where sound holds the potential for a radical criticality, to rethink our faith in a white male ontology, in cultural legibility, universality and a referential truth, by pursuing a more performative engagement from the margins (Figure 2).

Curatorial performance at “être à l’écoute” – a symposium on sound at EDHEA (École de design et haute école d’art du Valais in Sierre, Switzerland, October 2021, courtesy EDHEA).

1.2 Lines

“The line” is the US–EU modernity’s imaginary of thought and reality. It is its rationality, and its metrics of exclusion. It is drawn on maps and in textbooks, as a canon and as grammar. It defines the value and worth of scientific expression and findings, and it informs the political imaginary of Western modernity. It frames the context and canon against which one will be assessed. It is a historical and a contemporary construction that makes definition dialectical, “not that,” and makes science and politics possible by delimiting the impossible.[11] Research is essentially a negotiation of this line. Therefore, one central question is whether I can contextualise and reference what I am writing about in relation to this line, and what if I cannot?

I am not criticising the need for contextualisation. It is important to be in conversation with and surrounded by others’ thoughts and practice when researching and writing. But it is important also to ponder who I can be in the vicinity of? Who my partners in this exchange can be and whose writing counts as worthwhile context and voice, and who remains outside this frame of validity? What I am describing is the need to be aware of who is on this line and who is not on this line. And to question why this line is so straight, and white and male? How do writers such as Kant, Hegel, Deleuze et al. apparently assure my writing, while less canonical figures make it fuzzy, wobbly, and less readable. What ideological and political possibilities does the line perform? And how can we trouble it? How can we make a PhD, a successful postdoc, or a successful research project of any sort, without sticking to the line?

I am aware that I am starting with a contradiction or at least a tension between wanting a space in the curriculum for sound studies without wanting to adhere to its lines. How can I house sound within academia, to profit from its privileges, funding opportunities, visibility, etc. when its own shape, when its own demands maybe contradict the very infrastructure and structure that academia has built to remain legitimate. And in particular to remain legitimate in the context of current funding cuts for the arts and humanities, which naturally provoke a retrenchment onto conventional ground.

Working with sound within academia, we work in that tension and in that contradiction in a very interesting and useful way. I would like you to think of the radical criticality of sound, its inevitable proximity and indivisibility, as a benefit in the quest for making “an original contribution,” which is any research’s stated aim. Because, working with sound as part of your method and thinking brings with it the necessity and possibility for a broader and more methodological engagement, where new material, data, and historical information are not pushed through the conventional knowledge machine of visuo-cultural analysis and interpretation. But where the invisibility and indivisibility of the phenomenon under consideration disables the interpretative apparatus and provokes a paradigm shift that can help find truly new ways to know.

You might have to confront the invisible of your own discipline, of its contexts and infrastructure, to make space for it and let it challenge and re-form your approach and outcomes. This might feel precarious. However, not therefore less valuable or less doable.

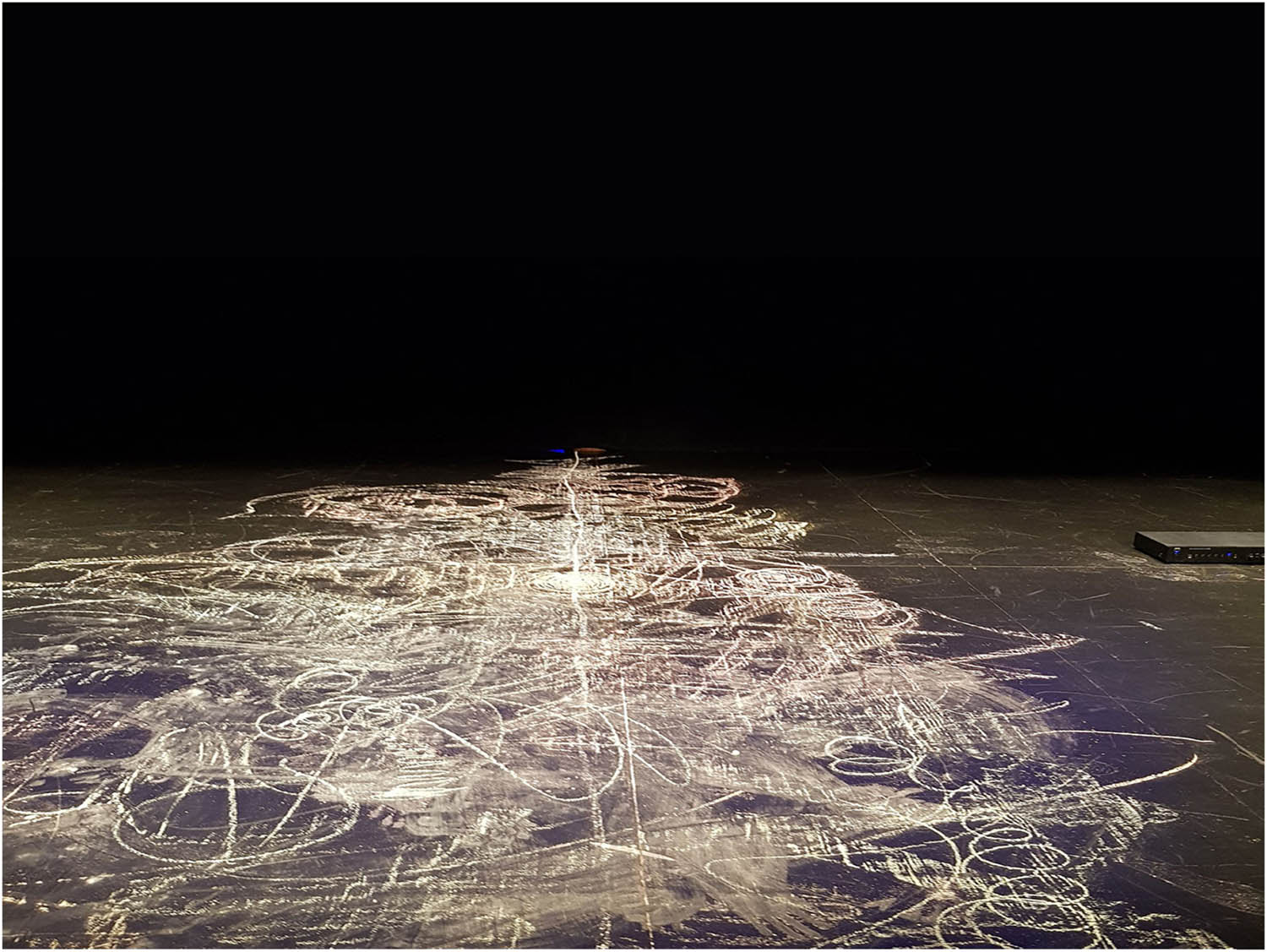

We can embrace the “mythical force” of sound with a feminist zeal and gain great jouissance from its quasi-gothic performance, unafraid. Because the conventions and the norms of the institutions of hegemonic (visual) knowledge are so strong and invested that they will not break and yield only very little, if at all. We can push, we can quite outrageously and radically ask for the line to become more elastic and diffuse, and we can temporarily jam and glitch the analytical apparatus, but we won’t destroy it. The aim is not to be destructive, but to bring the line together with the fuzzy stuff it was part of before the big enlightenment “tidy-up.” Because the line is not separate, it is part of everything. It only appears as a separate, straight, and white line because we have erased everything else (Figure 3).

Curatorial performance at “être à l’écoute” – a symposium on sound at EDHEA (École de design et haute école d’art du Valais in Sierre, Switzerland, October 2021, courtesy EDHEA).

There are precedents, scientists, and researchers we can turn to, to get inspiration on how to work in the fuzzy parts of knowledge, where categories and taxonomies fail to clarify, and language as semantic structure has to be rethought.

One such researcher is the anthropologist, linguist, and ethnomusicologist Steven Feld who I had the pleasure of meeting in London in 2018 when he came to present Voices of the Rainforest,[12] a 70 min 7.1 sound film of his field recordings made in the Bosavi rainforest. This film is put together from footage recorded over more than 20 years of field work, from the 70s to the early 90s, in Papua New Guinea. It is a very significant work in relation to the idea of a sonic epistemology and the confrontation of the invisible, a phrase that could be used to describe Feld’s research methods. What is so relevant is what his visits, working, and recording in the Bosavi rainforest did to Feld himself and to his anthropological and ethnographic training and expectations. How its environment and life demanded of him to break with pre-given methodologies and disciplinarity as the opaque view of too many trees, the dense soundscape, and the interdependent living of different species, disabled a distanced view, the pre-condition for categorisation and classification.

The conventional task of an anthropologist and ethnomusicologist would have been to identify song and music making, cultural rituals and behaviours, cooking, dancing, eating, and so on, so they could then be categorised and brought home into the US–EU knowledge scheme, labelled individually to be described and analysed separately. In his essay Acoustemology published in 2015, re-discussing this term which he had coined in the early 90s, Feld states that after 15 years of embedded research in the region, he recognised the limit of Western academia.[13] Accordingly, instead of providing taxonomies, most of his texts write through anecdotes about his encounters with the people, the forest, animals, sounds, and weather, telling us through these narrations how the trees are too dense to afford a distant view, and how the entanglements between forest, animals, people, rituals, song, and life are too indivisible to create categories.

Doing fieldwork in such a densely connected sphere does not present the condition for an objective and categorising scholarship. It becomes impossible to label and taxonomise and subsequently investigate things in their individuated form according to western-centric methodologies and expectations. Instead, embedded in the environment as in an entangled milieu, deprived of a distanced view, your ears and thus your body become part of what you are investigating. Consequently, your understanding has to be found on this body, from how it exists with other human and more-than-human bodies close up, through touch, smell, and sound.

This bodily knowledge is grounded in a local practice, a geography of proximity, without lines but an indivisible volume of trees. It does not find meaning through representation and categories but senses relationally. Feld describes how Bosavi's song is not an adaptation or response to, but a participation in the relationality of the forest. Its sounding is a listening with, rather than a singing about. It cannot offer a separate ethnomusical category that could be taxonomised in conventional western scholarship, away from the lived environment and within the pre-existing theory, because this would mute the conversations and connections made by the song and pull its relational interactions into a linguistic and representational frame, excluding their material, local, and contingent knowledge. Feld explains that conventional methodologies and knowledge paths will not hear the indivisible field but remain focused on separating the trees from song, from bird call, from insect chirping, and so on, to theorise their categories.[14] In response, “acoustemology, conjoins ‘acoustics’ and ‘epistemology’ to theorise sound as a way of knowing” relationally and stages “inquiries into what is knowable and how it becomes known, through sounding and listening.”[15] His listening abandons the possibility of recognition and classification and embraces as possible the “impossibility” of a generative, narrative, and embodied understanding from sound that is “direct” rather than semantic, visualised, and categorised.

The idea of acoustemology is not in the first instance drawn from a referential frame. Instead, “the idea is to think bigger, to reimagine the object of study more expansively, more philosophically, and more experimentally.”[16] This experimentality is not legitimated in discourse and vis-à-vis a canon and literature, but on the body, listening, being in the field of study, immersed in a listening with. Therefore, it does not produce a knowing through referencing but a “knowing-in-action: a knowing-with and knowing-through the audible.”[17] It engages knowledge through experience, which is always relational, and meets scholarship if at all, from this entangled practice.[18]

This acoustemology is conceptualised and practised as a critique of conventional anthropology and ethnomusicology, for the lines it drew and keeps on obeying to retain its disciplinary power while excluding everything else. At this place, Feld refers to Audre Lorde’s essay “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House” from 1984 and states with her that other intellectual tools are needed in order not to continue to hear signs and signifiers, songs, and birds and insects, separately, but to listen to songs with birds with insects in a relational practice that performs a knowing of the forest of which we are part.[19]

Following Feld, I understand sound as one such “other intellectual tool”[20] needed to destroy the master’s house built from hegemonic lines and perpetuating a reduced but universalised knowledge value. To develop and establish this other tool I propose a relational and transversal practice of sound through which we can hear our being with and establish a scholarship that reads objectivity with Donna Haraway and Karen Barad as a responsibility rather than as distance.[21] That is, as a responsibility to what we think we know and what we exclude by knowing it.[22]

Feld focuses on sound because his cultural visuality and visuo-musical literacy are barred by the trees. Listening outside its methods and categories he hears the in-between and the sounding together, and in this way, he troubles the line of conventional scholarship and its methodological limits. Enabled and compelled by a lack of distance, he at once reveals ethnomusicology’s inability to deal with what is between categories and opens its disciplinary boundaries from what he cannot see. However, I do not understand his practice of sound as an essentialised or essentialising concept or device. Instead, his focus on the auditory not only opens the discipline of ethnomusicology to its material complexity, it also opens a portal into the multisensory complexity of every discipline. Equally, this essay does not set up a binary between the visual and the sonic, seeing and listening. It does not bemoan sound’s historical neglect. By contrast, it focuses on the sonic in order to understand how we are looking, what scholarly identities, what knowledge, and what methodologies a normative cultural eye produces. And it uses a reorientation towards the ear to come to see more and differently: to re-vision our bodies and the world in the indivisibility of sound, so we might develop a scholarship that is inclusive of the invisible and relational dimension of the world, and not afraid of being put into question by its fuzzy, non-classifiable reality.

Listening to dense interdependencies, Feld comes to “see” as in feel, smell, and sense, the rainforest as an entangled sphere made graspable through sound as an access point to its multi-sensoriality and multispecies, multibody dimensionality, of which he is part.

This unavoidable entanglement and connectivity is a very powerful critical position from which to glean a different sense and a different view on the line and how it can be made fuzzy, inclusive, and permeable. It does not indicate the impossibility of (visual) scholarship but reveals the fictions of objectivity; and it provides a more complex, plural, embodied position to do research from.

Nothing is stopping us from taking this position here, in relation to our own research. Just because we think we can see the trees from the woods does not mean we can or we should pretend a measurable distance. There is a relational density that sound can make audible and thus thinkable, but the visual pretends to ignore by showing us chairs, and bodies, windows, and walls as separate entities that hide their correlation. Visually we expect and live our distance: this is this and that is that, and you are you and I am I. By contrast, if I clap my hands, stamp my foot, or sing a note, I agitate our in-between. Instead of hearing a separate entity, such as my clapping hands or stamping feet or you and me, as individuated and boundaried bodies, we come to sense this room as a vibrational sphere where you do not hear my hands, or my foot, not the floor I stamp on nor my voice. Instead, you hear everything sound in the agitation of my clap: the way it sounds with the soft curtains, the flat surfaces, the texture of the wall, and with all the other human and more-than-human bodies in this room, as well as in relation to its size and temperature, its air pressure, humidity, and so on. Sounding the being with of all human and more-than-human bodies in their mattering together.

Crucially this vibrationality is not a metaphor, but is the phenomenon under consideration, sound experienced in its relationality, which guides its systematic discussion. The vibrational capacity of sound makes things thinkable and knowable from their relationality. It brings to perception how everything moves together, invisibly and indivisibly, composing an interdependent world. Therefore, we can question whether the distance we rely on for our scholarship really exists, or whether it is a visual fiction of science? And we can ponder how the sonic agitation of the in-between and with refutes distance and thus objectivity and therefore Western scholarship, just like the trees did. And how instead it makes a different scholarship necessary but also accessible and thus thinkable and practicable: the scholarship of correlation, of a vibrational sphere and interdependencies heard with “expanded ears” and many bodies.[23]

It is in this sense that listening as concurrent with sounding makes a dialogue. And it is from this dialogue between human and more-than-human bodies that different knowledges and different knowledge methodologies can emerge. This sonic dialogue is the “other tool” that can dismantle the master’s house, and build others, in the plural and in formless forms: rickety, unsteady, haphazard, and temporary accommodations of knowledge that decolonise hegemonic epistemologies and question universals; that are feminist because inventive of positionalities; and that are intersectional by making all lines visible simultaneously.

However, this is not the proposal of an idealist auditory research architecture. There is no guarantee that the rickety thought-buildings thus produced will yield a better view, a more critical infrastructure, and that it will result in a more symmetrical world. Sound is not per se the saviour of ethnomusicology or of philosophy. But what it does do, in its haphazard formlessness, is to make the instrumentality and “purpose-tautologies” of research visible and to trouble (visual) norms and expectations.

The confrontation of what we cannot see through a sounding-listening with what is off the line and a listening-sounding with beyond the category, in the fuzzy geography of a tacit, local, and embodied knowledge and experience, unsettles foundational ideas that assure communication but exclude what falls beyond their frame. Instead, it enables a dialogue with what and how we do not know. In this sense sound is a tool for making visible the unknown, as in the unnameable, and the non-classifiable, and reveals our interdependencies with its (im)possibilities. This unsteady view might, at least at first, induce a vertigo of proximity and bring forth an anxiety of losing clear parameters of knowledge, of science and the arts.

This is, as stated before, not a cause to abandon scholarship and academia, however. To the contrary, it is a provocation to write and research even more deliberately, radically, and outrageously across and beyond lines. To work with a language that is ready to lose the line and de-form and re-form its own grammar through a sounding listening dialogue with what it researches. And it is a challenge also to how we can assess and peer-review such work that draws off and is in conversation with the apparently impossible: the fuzzy, the tacit, the relational, and the embodied, and that is in dialogue with authors, artists, and theorists that we might not know from a canonical view and whose voices and bodies come to mean not through historical reference but in a present dialogue. This is one of the greatest challenges and opportunities of current academic work. And not engaging in it, remaining in the paradigm of literature and reference, is, according to Jeuk, one of the reasons contemporary philosophy lacks “greatness.”[24]

Peer review, assessment, and examination depend on a measurable work/world. But how to practice and cultivate the possibility of writing not from literature and debates, but from the body, mine and that of the reader, in proximity without expectations, without canons and standardisation, but with the hope nevertheless for dialogue? And how to read and assess not from the known but in conversation with the unknown and on plural terms? To admit into academia also what I do not recognise but which might make a contingent, embodied, and sensory sense, measured not as trees but from the experience of their in-between?

I have no universal answer to these questions, as a sonic practice and sensibility present a de-universalising of the academic world and scholarship, leaving us with innovative explanations on the structure of experience, but with no succinct conclusions, just more to think and do. From here, we might have to figure it out contingently, ethically, and with a desire to be in conversation with what we do not yet know.

Therefore, at the end of this essay, I want to invite you to practice a “rainforest view” on scholarship. To rethink the dry, mute, categorised, and taxonomised environments of Western discourse and scholarship through the sonic fiction of a humid, voluminous, indivisible, and opaque simultaneity. To become aware of what we exclude to reach certainty and to ask what we might be able to include if we engage the opaque, the invisible, and the relational.

Listening to Feld’s sound film in the Curzon at the Brunswick Centre in London in 2018 got me some way there. It remained a representation and re-enactment, but near enough to make me think and shift my ears to get a view of the in-between and sense blind spots, without having to go to the rainforest and add to the climate catastrophe by my going there. Listening to sound artwork and the sonic environment can help us practice expanded listening that is embodied, non-structural, uncertain, unreliable but entangled. And from this experience, we can bring a sonic competency to scholarship and academic work. We can practice listening and sound with in order to feel, smell, and sense relationships and mobile in-betweens and to understand the complicity of our own bodies, as matter and orientation, in anything we see, judge, and think to know.

This is where I re-meet the suitcase. The performative device I developed from a sense of frustration about what remains ignored or deliberately excluded from conventional academic discourse. Paired with a sense of optimism or at least deliberate naivety of how we could include it against all odds. (For those of you reading this as an essay, at this stage in the talk I opened the suitcase and revealed its contents while discussing what they enable and are used for.)

The suitcase holds various and changing objects: books, texts, scores, recording and playback technologies, a stethoscope, earplugs, masks, gloves, headphones, and so on. These help me to workshop with people to expand our ears together. We do sound walks, listening exercises, produce sonic designs, and re-vision problems and tasks from the invisible. Thus, these elements assist in a practical theorising of the world from sound. It is the playful but also serious foundation of a non-foundational and cross-disciplinary scholarship with which I would like to visit as many teaching, learning, and researching institutions as possible, to advocate for transversal sound studies, as an applied methodology that can pluralise a current hegemonic knowledge system, offer a shared hybrid sphere for interdisciplinarity, and bring a view on the interdependent to our current emergencies of climate and public health, scarcity of resources and migratory pressures, social injustice, and so on, to understand these entangled problems from the entanglement of “direct” sound and with a leaky vision that sees the in-between.

1.3 A Short Note on Sound’s Benevolence

Just before I end, I want to stress again that sound is one “other intellectual tool” among many. And like most things that aim to introduce a different thinking, it can also be abused. Thus, as mentioned earlier, sound does not represent an ideal. Its practice is not per se benevolent and progressive, generative of a symmetrical world. Its very ability to be close and intimate, which I rate as its great asset for a decolonial and feminist scholarship, can also be used to manipulate, abuse, persuade us of fake news, and normalise unacceptable politics.

But what it does do, in its ephemeral indivisibility, is to transform an individuated and quantifiable reception into a relational and reciprocal practice of perception, where sounding is a listening with, where the two are simultaneous and connected and thus aware of their responsibility to the hearing and the making of sound. In this way, sound evokes an ethics of how we participate and are part of the real, rather than an ethics of behaviour or of things based on visual norms, judged from a distance, as an objective reality. Because if I understand that the world I hear is the world I hear because of the way I listen and am matter with, and that, in turn, the way I am matter with sounds within this world I hear, then I am forced to face my listening through this reciprocity and consequently am forced to appreciate my responsibility towards the “knowledge-in-action”[25] created by this cyclical exchange. In other words, sound represents a resource, concept, method, and tool to question and expand how we know. It does not guard against malevolence, asymmetries, abuse, discrimination, and exclusion. However, given its relational logic and its participatory ethics, we might be in a better position to hear and feel such abuse taking place and act accordingly.[26]

-

Conflict of interest: Author states no conflict of interest.

References

Attali, Jacques. Noise the Political Economy of Music. Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press, 1985.Search in Google Scholar

Augoyard, Jean-François and Henri Torgue. Sonic Experience: A Guide to Everyday Sounds. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1985.Search in Google Scholar

Barad, Karen. Meeting the Universe Halfway. London: Duke University Press, 2007.10.2307/j.ctv12101zqSearch in Google Scholar

Barad, Karen. “Posthumanist Performativity: Towards an Understanding of How Matter Comes to Matter.” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 28, no. 3, Gender and Science: New Issues (Spring 2003), 801–31.10.1086/345321Search in Google Scholar

Bijsterveld, Karin, 2019. Sonic Skills: Listening for Knowledge in Science, Medicine and Engineering (1920s-Present). London: Palgrave Macmillan.10.1057/978-1-137-59829-5Search in Google Scholar

Birdsall, Carol. Nazi Soundscapes: Sound, Technology and Urban Space in Germany, 1933–1945. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2014.Search in Google Scholar

Braidotti, Rosi. Posthuman Knowledge. Cambridge: Polity Press, 2019.Search in Google Scholar

Braidotti, Rosi. Posthuman. Cambridge: Polity, 2013.Search in Google Scholar

Claus, Caroline. Sonic Perspectives on Urbanism. Dijon: Les Presses du Réel, 2018.Search in Google Scholar

Daughtry, Martin J. Listening to War: Sound, Music, Trauma and Survival in Wartime Iraq. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199361496.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Dyson, Francis. Tone of Our Times. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2014.10.7551/mitpress/8427.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Erlman, Veit. Reason and Resonance: A History of Modern Aurality. New York: Zone Books, 2010.Search in Google Scholar

Eshun, Kodwo. More Brilliant than the Sun: Adventures in Sonic Fiction. London: Quartet Books, 1998.Search in Google Scholar

Feld, Steven. “On Post-Ethnomusicology Alternatives: Acoustemology.” In Perspectives on a 21st Century Comparative Musicology, Ethnomusicology or Transcultural Musicology, edited by Claudio Rizzoni, 82–98. Udine, Italy: Nota Valter Colle, 2017.Search in Google Scholar

Feld, Steven, “Acoustemology.” In Keywords in Sound, edited by David Novak and Matt Sakakeeny, 12–21. London: Duke University Press, 2015.10.2307/j.ctv11sn6t9.4Search in Google Scholar

Furlonge, Nicole. Race Sounds: The Art of Listening in African American Literature. Iowa: University of Iowa Press, 2018.10.1353/book58293Search in Google Scholar

Goodman, Steve. Sonic Warfare: Sound Affect and the Ecology of Fear. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2012.Search in Google Scholar

Haraway, Donna. The Companion Species Manifesto – Dogs, People & Significant Otherness: Dogs, People, and Significant Otherness. California, US: Prickly Paradigm Press, 2003.Search in Google Scholar

Haraway, Donna. Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016.10.2307/j.ctv11cw25qSearch in Google Scholar

Irigaray, Luce and Michael Marder. Through Vegetal Being, Philosophical Perspectives. US: Universityb of Columbia Press, 2016.Search in Google Scholar

Irigaray, Luce. Sharing the World. US: Bloomsbury, 2008.10.5040/9781350251922Search in Google Scholar

Jeuk, Alexander, “What Happened to Philosophy?” In Philosophy Now, 20–3, October/November 2023.Search in Google Scholar

Kanngieser, Anja. “Geopolitics and the Anthropocene: Five Propositions for Sound.” Geohumanities 1:1 (2015), 1–6.10.1080/2373566X.2015.1075360Search in Google Scholar

Kassabian, Anahid. Ubiquitous Listening: Affect, Attention and Distributed Subjecitvity. US: University of California Press, 2013.10.1525/california/9780520275157.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Lorde, Audre. “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House.” In Your Silence Will Not Protect You, 89–93. UK: Silver Press, 2017.10.1093/oso/9780198782360.003.0009Search in Google Scholar

McEnaney, Tom. “The Sonic Turn.” Diacritics 47:4 (2019), 80–109.10.1353/dia.2019.0035Search in Google Scholar

Napolin, Julie Beth. The Fact of Resonance: Modernist Acoustics and Narrative Form. New York: Fordham University Press, 2020.10.1515/9780823288199Search in Google Scholar

Ouzounian, Gascia. Stereophonica: Sound in Space, Technology and the Arts. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT, 2020.10.7551/mitpress/11698.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Rancière, Jacques. Disagreement, Politics and Philosophy. London: University of Minnesota Press, 1999.Search in Google Scholar

Reyner, Igor, “Fictional Narratives of Listening: Crossovers between Literature and Sound Studies.” Interference Journal (2017).Search in Google Scholar

Robinson, Dylan. Hungry Listening: Resonant Theory for Indigenous Sound Studies. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2020.10.5749/j.ctvzpv6bbSearch in Google Scholar

Rogers, Tara. Pink Noises: Women on Electronic Music and Sound. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2010.10.1515/9780822394150Search in Google Scholar

Shildrick, Margrit. Embodying the Monster, Encounters with the Vulnerable Self. London: Sage, 2002.10.4135/9781446220573Search in Google Scholar

Schuppli, Susan. Material Witness: Media, Forensics, Evidence. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2020.10.7551/mitpress/9953.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Sterne, Jonathan (ed.). The Sound Studies Reader. London: Routledge, 2012.10.4324/9780203723647Search in Google Scholar

Stoever, Jennifer. The Sonic Color Line: Race and the Cultural Politics of Listening. New York: New York University Press, 2016.10.2307/j.ctt1bj4s55Search in Google Scholar

Thompson, Emily. “Wiring the World: Theater Installation Engineers and the Empire of Sound in the Motion Picture Industry, 1927–1930.” In Hearing Cultures: Essays on Sound, Listeing ad Modernity, edited by Veit Erlmann, 191–209. London: Berg, 2004.10.4324/9781003103189-10Search in Google Scholar

Voegelin, Salomé. Sonic Possible Worlds: Hearing the Continuum of Sound, 2nd edn. US, NY: Bloomsbury, 2020.10.5040/9781501367656Search in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Special issue: Happiness in Contemporary Continental Philosophy, edited by Ype de Boer (Radboud University, the Netherlands)

- Editorial for Topical Issue “Happiness in Contemporary Continental Philosophy”

- Badiou and Agamben Beyond the Happiness Industry and its Critics

- Happiness and the Biopolitics of Knowledge: From the Contemplative Lifestyle to the Economy of Well-Being and Back Again

- Reanimating Public Happiness: Reading Cavarero and Butler beyond Arendt

- Thinking from the Home: Emanuele Coccia on Domesticity and Happiness

- A Strategy for Happiness, in the Wake of Spinoza

- Das Unabgeschlossene (das Glück). Walter Benjamin’s “Idea of Happiness”

- The Role and Value of Happiness in the Work of Paul Ricoeur

- On the “How” and the “Why”: Nietzsche on Happiness and the Meaningful Life

- Albert Camus and Rachel Bespaloff: Happiness in a Challenging World

- Symptomatic Comedy. On Alenka Zupančič’s The Odd One In and Happiness

- Happiness and Joy in Aristotle and Bergson as Life of Thoughtful and Creative Action

- Special issue: Dialogical Approaches to the Sphere ‘in-between’ Self and Other: The Methodological Meaning of Listening, edited by Claudia Welz and Bjarke Mørkøre Stigel Hansen (Aarhus University, Denmark)

- Sonic Epistemologies: Confrontations with the Invisible

- The Poetics of Listening

- From the Visual to the Auditory in Heidegger’s Being and Time and Augustine’s Confessions

- The Auditory Dimension of the Technologically Mediated Self

- Calling and Responding: An Ethical-Existential Framework for Conceptualising Interactions “in-between” Self and Other

- More Than One Encounter: Exploring the Second-Person Perspective and the In-Between

- Special issue: Lukács and the Critical Legacy of Classical German Philosophy, edited by Rüdiger Dannemann (International Georg-Lukács-Society) and Gregor Schäfer (University of Basel)

- Introduction to the Special Issue “Lukács and the Critical Legacy of Classical German Philosophy”

- German Idealism, Marxism, and Lukács’ Concept of Dialectical Ontology

- The Marxist Method as the Foundation of Social Criticism – Lukács’ Perspective

- Modality and Actuality: Lukács’s Criticism of Hegel in History and Class Consciousness

- “Objective Possibility” in Lukács’s History and Class Consciousness

- The Hegelian Master–Slave Dialectic in History and Class Consciousness

- “It Would be Helpful to Know Which Textbook Teaches the ‘Dialectic’ he Advocates.” Inserting Lukács into the Neurath–Horkheimer Debate

- Everyday Hegemony: Reification, the Supermarket, and the Nuclear Family

- Critique of Reification of Art and Creativity in the Digital Age: A Lukácsian Approach to AI and NFT Art

- Special issue: Theory Materialized–Art-object Theorized, edited by Ido Govrin (University of Tessaly, Greece)

- Material–Art–Dust. Reflections on Dust Research between Art and Theory

- Nancy in Jerusalem: Soundscapes of a City

- Zaniness, Idleness and the Fall of Late Neoliberalism’s Art

- Enriching Flaws of Scent عطر עטרה A Guava Scent Collection

- Special issue: Towards a Dialogue between Object-Oriented Ontology and Science, edited by Adrian Razvan Sandru (Champalimaud Foundation, Portugal), Federica Gonzalez Luna Ortiz (University of Tuebingen, Germany), and Zachary F. Mainen (Champalimaud Foundation, Portugal)

- Retroactivity in Science: Latour, Žižek, Kuhn

- The Analog Ends of Science: Investigating the Analogy of the Laws of Nature Through Object-Oriented Ontology and Ontogenetic Naturalism

- The Basic Dualism in the World: Object-Oriented Ontology and Systems Theory

- Knowing Holbein’s Objects: An Object-Oriented-Ontology Analysis of The Ambassadors

- Relational or Object-Oriented? A Dialogue between Two Contemporary Ontologies

- The Possibility of Object-Oriented Film Philosophy

- Rethinking Organismic Unity: Object-Oriented Ontology and the Human Microbiome

- Beyond the Dichotomy of Literal and Metaphorical Language in the Context of Contemporary Physics

- Revisiting the Notion of Vicarious Cause: Allure, Metaphor, and Realism in Object-Oriented Ontology

- Hypnosis, Aesthetics, and Sociality: On How Images Can Create Experiences

- Special issue: Human Being and Time, edited by Addison Ellis (American University in Cairo, Egypt)

- The Temporal Difference and Timelessness in Kant and Heidegger

- Hegel’s Theory of Time

- Transcendental Apperception from a Phenomenological Perspective: Kant and Husserl on Ego’s Emptiness

- Heidegger’s Critical Confrontation with the Concept of Truth as Validity

- Thinking the Pure and Empty Form of Dead Time. Individuation and Creation of Thinking in Gilles Deleuze’s Philosophy of Time

- Ambient Temporalities: Rethinking Object-Oriented Time through Kant, Husserl, and Heidegger

- Special issue: Existence and Nonexistence in the History of Logic, edited by Graziana Ciola (Radboud University Nijmegen, Netherlands), Milo Crimi (University of Montevallo, USA), and Calvin Normore (University of California in Los Angeles, USA) - Part I

- Non-Existence: The Nuclear Option

- Individuals, Existence, and Existential Commitment in Visual Reasoning

- Cultivating Trees: Lewis Carroll’s Method of Solving (and Creating) Multi-literal Branching Sorites Problems

- Abelard’s Ontology of Forms: Some New Evidence from the Nominales and the Albricani

- Boethius of Dacia and Terence Parsons: Verbs and Verb Tense Then and Now

- Regular Articles

- “We Understand Him Even Better Than He Understood Himself”: Kant and Plato on Sensibility, God, and the Good

- Self-abnegation, Decentering of Objective Relations, and Intuition of Nature: Toomas Altnurme’s and Cao Jun’s Art

- Nietzsche, Nishitani, and Laruelle on Faith and Immanence

- Meillassoux and Heidegger – How to Deal with Things-in-Themselves?

- Arvydas Šliogeris’ Perspective on Place: Shaping the Cosmopolis for a Sustainable Presence

- Raging Ennui: On Boredom, History, and the Collapse of Liberal Time

Articles in the same Issue

- Special issue: Happiness in Contemporary Continental Philosophy, edited by Ype de Boer (Radboud University, the Netherlands)

- Editorial for Topical Issue “Happiness in Contemporary Continental Philosophy”

- Badiou and Agamben Beyond the Happiness Industry and its Critics

- Happiness and the Biopolitics of Knowledge: From the Contemplative Lifestyle to the Economy of Well-Being and Back Again

- Reanimating Public Happiness: Reading Cavarero and Butler beyond Arendt

- Thinking from the Home: Emanuele Coccia on Domesticity and Happiness

- A Strategy for Happiness, in the Wake of Spinoza

- Das Unabgeschlossene (das Glück). Walter Benjamin’s “Idea of Happiness”

- The Role and Value of Happiness in the Work of Paul Ricoeur

- On the “How” and the “Why”: Nietzsche on Happiness and the Meaningful Life

- Albert Camus and Rachel Bespaloff: Happiness in a Challenging World

- Symptomatic Comedy. On Alenka Zupančič’s The Odd One In and Happiness

- Happiness and Joy in Aristotle and Bergson as Life of Thoughtful and Creative Action

- Special issue: Dialogical Approaches to the Sphere ‘in-between’ Self and Other: The Methodological Meaning of Listening, edited by Claudia Welz and Bjarke Mørkøre Stigel Hansen (Aarhus University, Denmark)

- Sonic Epistemologies: Confrontations with the Invisible

- The Poetics of Listening

- From the Visual to the Auditory in Heidegger’s Being and Time and Augustine’s Confessions

- The Auditory Dimension of the Technologically Mediated Self

- Calling and Responding: An Ethical-Existential Framework for Conceptualising Interactions “in-between” Self and Other

- More Than One Encounter: Exploring the Second-Person Perspective and the In-Between

- Special issue: Lukács and the Critical Legacy of Classical German Philosophy, edited by Rüdiger Dannemann (International Georg-Lukács-Society) and Gregor Schäfer (University of Basel)

- Introduction to the Special Issue “Lukács and the Critical Legacy of Classical German Philosophy”

- German Idealism, Marxism, and Lukács’ Concept of Dialectical Ontology

- The Marxist Method as the Foundation of Social Criticism – Lukács’ Perspective

- Modality and Actuality: Lukács’s Criticism of Hegel in History and Class Consciousness

- “Objective Possibility” in Lukács’s History and Class Consciousness

- The Hegelian Master–Slave Dialectic in History and Class Consciousness

- “It Would be Helpful to Know Which Textbook Teaches the ‘Dialectic’ he Advocates.” Inserting Lukács into the Neurath–Horkheimer Debate

- Everyday Hegemony: Reification, the Supermarket, and the Nuclear Family

- Critique of Reification of Art and Creativity in the Digital Age: A Lukácsian Approach to AI and NFT Art

- Special issue: Theory Materialized–Art-object Theorized, edited by Ido Govrin (University of Tessaly, Greece)

- Material–Art–Dust. Reflections on Dust Research between Art and Theory

- Nancy in Jerusalem: Soundscapes of a City

- Zaniness, Idleness and the Fall of Late Neoliberalism’s Art

- Enriching Flaws of Scent عطر עטרה A Guava Scent Collection

- Special issue: Towards a Dialogue between Object-Oriented Ontology and Science, edited by Adrian Razvan Sandru (Champalimaud Foundation, Portugal), Federica Gonzalez Luna Ortiz (University of Tuebingen, Germany), and Zachary F. Mainen (Champalimaud Foundation, Portugal)

- Retroactivity in Science: Latour, Žižek, Kuhn

- The Analog Ends of Science: Investigating the Analogy of the Laws of Nature Through Object-Oriented Ontology and Ontogenetic Naturalism

- The Basic Dualism in the World: Object-Oriented Ontology and Systems Theory

- Knowing Holbein’s Objects: An Object-Oriented-Ontology Analysis of The Ambassadors

- Relational or Object-Oriented? A Dialogue between Two Contemporary Ontologies

- The Possibility of Object-Oriented Film Philosophy

- Rethinking Organismic Unity: Object-Oriented Ontology and the Human Microbiome

- Beyond the Dichotomy of Literal and Metaphorical Language in the Context of Contemporary Physics

- Revisiting the Notion of Vicarious Cause: Allure, Metaphor, and Realism in Object-Oriented Ontology

- Hypnosis, Aesthetics, and Sociality: On How Images Can Create Experiences

- Special issue: Human Being and Time, edited by Addison Ellis (American University in Cairo, Egypt)

- The Temporal Difference and Timelessness in Kant and Heidegger

- Hegel’s Theory of Time

- Transcendental Apperception from a Phenomenological Perspective: Kant and Husserl on Ego’s Emptiness

- Heidegger’s Critical Confrontation with the Concept of Truth as Validity

- Thinking the Pure and Empty Form of Dead Time. Individuation and Creation of Thinking in Gilles Deleuze’s Philosophy of Time

- Ambient Temporalities: Rethinking Object-Oriented Time through Kant, Husserl, and Heidegger

- Special issue: Existence and Nonexistence in the History of Logic, edited by Graziana Ciola (Radboud University Nijmegen, Netherlands), Milo Crimi (University of Montevallo, USA), and Calvin Normore (University of California in Los Angeles, USA) - Part I

- Non-Existence: The Nuclear Option

- Individuals, Existence, and Existential Commitment in Visual Reasoning

- Cultivating Trees: Lewis Carroll’s Method of Solving (and Creating) Multi-literal Branching Sorites Problems

- Abelard’s Ontology of Forms: Some New Evidence from the Nominales and the Albricani

- Boethius of Dacia and Terence Parsons: Verbs and Verb Tense Then and Now

- Regular Articles

- “We Understand Him Even Better Than He Understood Himself”: Kant and Plato on Sensibility, God, and the Good

- Self-abnegation, Decentering of Objective Relations, and Intuition of Nature: Toomas Altnurme’s and Cao Jun’s Art

- Nietzsche, Nishitani, and Laruelle on Faith and Immanence

- Meillassoux and Heidegger – How to Deal with Things-in-Themselves?

- Arvydas Šliogeris’ Perspective on Place: Shaping the Cosmopolis for a Sustainable Presence

- Raging Ennui: On Boredom, History, and the Collapse of Liberal Time