Abstract

Background

There is seemingly no clear path to obtain the relevant information during postpartum as there is limited understanding of the information-seeking behaviour of postpartum women in recent times and difficulty in getting adequate healthcare information in sub-Saharan Africa. In Ghana, numerous studies exist on information needs and information-seeking behaviour in the health sector, but none emphasized both the health information needs and information-seeking behaviour of postpartum women.

Aim

This study aimed to investigate the health information needs and the information-seeking behaviour of first-time postpartum mothers in the Sunyani Municipal Hospital in Ghana.

Methods

The study employed a cross-sectional survey which used a quantitative research approach and a convenience sampling technique to sample 139 first-time mothers using a questionnaire that is based on a scientific understanding of how people find and use information.

Findings

It was revealed that the majority of first-time mothers had experienced the need for health information and had adequate knowledge about health issues but inadequate or moderate knowledge of postpartum health issues. Their most preferred source of health information is the healthcare professional due to their trust in them, and first-time mothers also consulted other informal sources without proper evaluation.

Conclusion

The state of becoming a mother comes with its challenges, and as such, timely and accurate health information is needed to help curb these challenges. Through training and education, government and authorities can help protect postpartum mothers from harm.

1 Introduction

An individual’s health information seeking is informed considerably by his or her current health status (Markwei & Rasmussen, 2015). This is no different from women experiencing postpartum – the period right after childbirth, extending to a period of 6 months where a woman goes through a transition from womanhood to motherhood, which is described as a period of intense social change (Javadifar, Majlesi, Nikbakht, Nedjat, & Montazeri, 2016) and psychological adjustment (Kamali, Ahmadian, Khajouei, & Bahaadinbeigy, 2018). During postpartum, the new mother becomes highly vulnerable to some infections for which she can experience lifelong health complications or even lose her life. Some of the numerous infections and complications associated with postpartum include haemorrhage, sepsis, hypertensive disorders, malaria, anaemia, malnutrition (Galvão, Braga, Gonçalves, Guimarães, & Braga, 2016), excessive tiredness or breathlessness, severe abdominal pain, discomfort, swollen hands or face or legs, painful or sore breast with cracks or bleeding nipples, eclampsia (Wichaidit et al., 2016), and mental health disorders (Zivoder et al., 2019).

There is a lack of a clear understanding of the information-seeking behaviour of postpartum women in recent times, and with that, it is difficult to get them the help they need. As seen in literature, during postpartum, women, especially first-time mothers, face vast and varied information needs, but how they satisfy these information needs is not well established in scientific studies. In sub-Saharan Africa, new mothers, unfortunately, do not receive adequate information from their healthcare providers on how to manage their current condition (Owen, Colburn, Tetteh, & Srofenyoh, 2020), which is attributed to the inadequate understanding of their health information needs and information-seeking behaviours (Abebe, Hill, Vaughan, Small, & Schwartz, 2019). For some researchers (Owen et al., 2020), healthcare providers over-rely on group counselling instead of counselling mothers individually concerning their needs and that of their newborns.

In Ghana, there have been numerous studies on information needs and information-seeking behaviour in the health sector. Notable among them is the snapshot of information-seeking behaviour in health science using the bibliometric approach (Abubakar & Harande, 2010), health information-seeking behaviour (HISB) on the Internet by graduate students (Ansah-koi, 2013), information needs of women undergoing treatment and management of breast cancer (Boadi, 2018), and HISB of women in a peri-urban community (Jang, 2019). Other researchers, however, focused on women in the postpartum or postnatal period (e.g., Ahn & Corwin, 2015; Owusu-Aidoo, 2019; Owen et al., 2020).

Despite the increasing studies on health information needs and information-seeking behaviour (Abebe et al., 2019; Jang, 2019; Rotich & Wolvaardt, 2017; Wang, Zhou, Ni, & Pan, 2020) on one side and studies on women in the postpartum period (Ahn & Corwin, 2015; Owusu-Aidoo, 2019; Zivoder et al., 2019) on the other side, none of them focused on both the health information needs and information-seeking behaviour of postpartum women. Generally, this study sought to fill this gap by examining the health information needs and the information-seeking behaviour of first-time mothers. Specifically, five objectives guided the conduct of this study. They are as follows:

To identify the health information needs of first-time mothers.

To ascertain the HISB of first-time mothers.

To find out the sources of health information available to first-time mothers

To evaluate the accessibility of health information by first-time mothers.

To determine the challenges/barriers faced by first-time mothers in seeking health information.

This study’s findings seek to inform policy-making in health institutions, make a practical contribution to the health sector concerning the health information needs and information-seeking behaviour of postpartum women, and add to the existing literature in the study area. The remainder of this article is divided into five sections. Related literature is reviewed in the next section then followed by the methodology of the study. Data are analyzed and discussed in the Section 4. The study is concluded in Section 5 with recommendations.

2 Literature Review

Health information is information about an individual’s health and the choices related to it (such as illnesses, symptoms, and treatment) and information about error prevention, and increased safety during one’s care (Ramsay, Peters, Corsini, & Eckert, 2017).

Although health information is invaluable and can empower effective decision-making on one’s health, it can be quite overwhelming and confusing as a result of excess information on the Internet, in journals, and in other sources due to the changing dynamisms of research on health information, resulting in diverse opinions held by different health experts (University of California, 2021). It has become necessary that individuals evaluate their health information very well to ensure that they are reliable.

2.1 Health Information Needs of Postpartum Women

The fundamental building block of a woman’s health during pregnancy, childbirth, and postpartum is maternal health information. Although globally there have been several concerns and interests in mother–child health care, there continue to be records of unmet maternal information needs. Most women receive inadequate education or information, resulting in preventable deaths of mothers and their babies during the perinatal period, especially in developing countries (Mulauzi & Daka, 2018).

According to some researchers (e.g., Rotich & Wolvaardt, 2017), postpartum is characterized by many health complications which can be addressed on time if important information is provided on maternal and newborn care right after childbirth. As such, the researchers undertook a study to determine the information needs of mothers and their babies within the first 6 weeks after delivery. The study revealed that health information need was the only health need that the mothers reported as unmet. This unmet need is evident that the health information needs of postpartum mothers largely are not understood, hence the insufficient supply of health information to meet this need (Martinović, Kim, & Katavić, 2023).

2.2 HISB

HISB is described specifically by some researchers (e.g., Kamyar, Kazerani, Shekofteh, & Jambarsang, 2023; Mills & Todorova, 2016) as ways in which people search, find, and use information relating to their health, illnesses, risks, and health-protective behaviours. Jacobs, Amuta, and Jeon (2017) found that the current health status of an individual, family health history, and perception of their health can influence a person’s HISB which play an important role in disease control (Abebe et al., 2019). Madge, Marincaș, Daha, and Simion (2023) add that gravity of the health need may lead to active or passive information seeking or total information avoidance. Corrarino (2013) shows that health information seeking is a vital element of the ability of a woman to identify a need and a source, as well as act on health-related information, and includes health promotion and disease prevention activities.

2.3 Information-Seeking Behaviour of Postpartum Women

Information-seeking behaviour is how people search for and use information (Orlu, Mafo, & Tochukwu, 2017). By understanding the actual information need and information-seeking behaviour of individuals, service providers will be able to provide quality services for their clientele (Umar, Umar, & Hussaini, 2020). Jaafar, Ainin, and Yeong (2017) show that women, unlike men, are more conscious of health issues and are highly interested in seeking health information; thus, they have a higher tendency to accept and engage with their illness and that of others and seek health information to help (Kilpatrick, King, & Willis, 2015).

Orlu et al. (2017) revealed in their study that an individual’s emotions determine their information-seeking behaviour. Also, they uncovered that the initial stage of information searching is characterized by uncertainty and anxiety. Hence, the researchers emphasized the need for an organized but flexible search strategy.

2.4 Theoretical Review

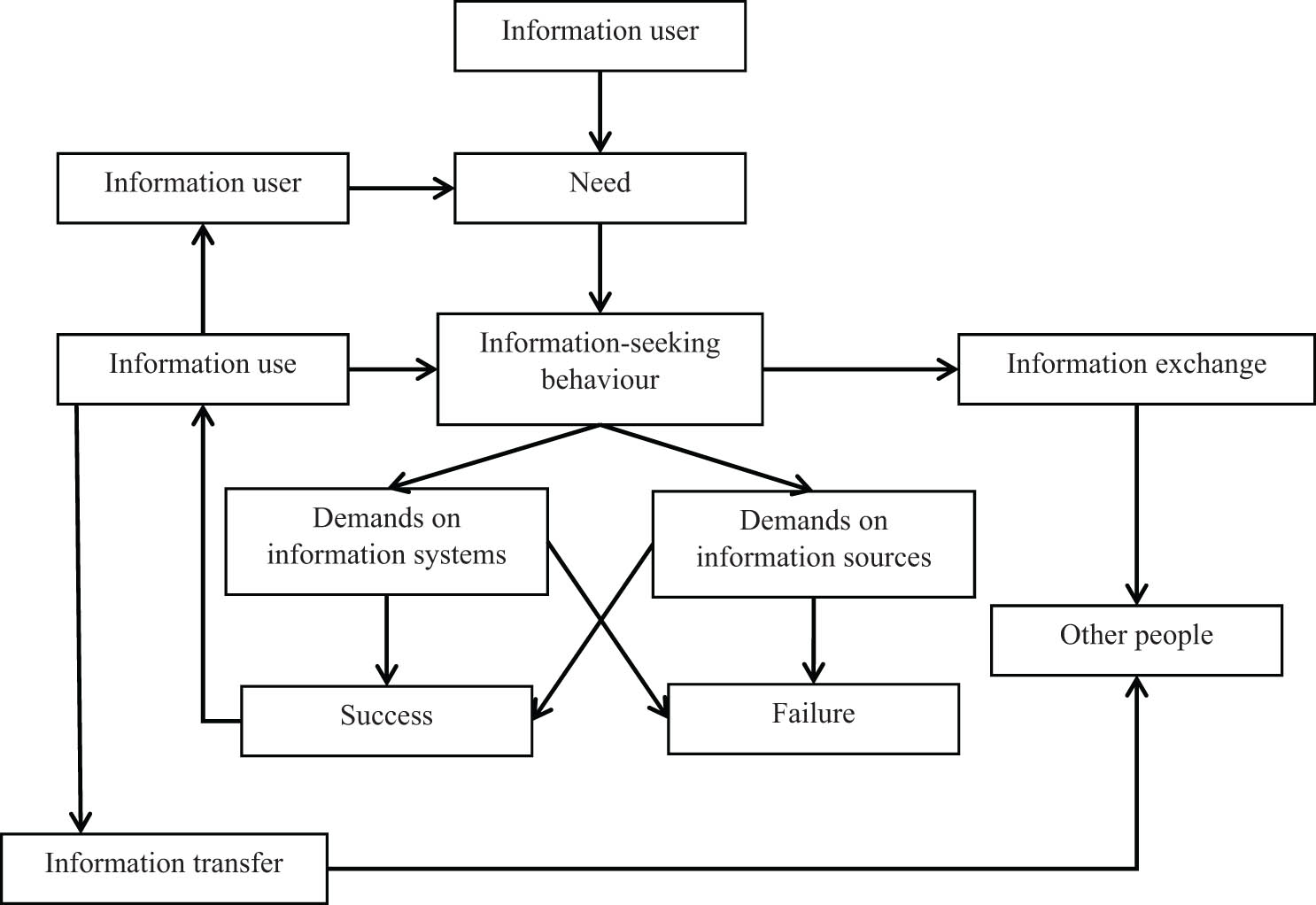

Wilson’s model of information behaviour is one of the commonly used models in explaining information-seeking behaviour (Tewell, 2015). The model has been used by several studies (e.g., Jang, 2019; Makinde, 2018) in explaining the information-seeking behaviour of different groups like women and pregnant women.

The study, therefore, adopted Wilson’s (1999) model of information behaviour as its theoretical framework, to help showcase the information-seeking behaviour of women in postpartum based on needs, information-seeking behaviour, and information sources, systems, and use.

2.5 Wilson’s Model of Information Behaviour

Wilson’s (1999) model focuses on the information needs, information seeking, and information use of the user. It shows that every information user has diverse needs and many patterns of seeking information during their consultations with several information sources. Wilson’s model also specifies that users of information have needs that may be because of their earlier “satisfaction or non-satisfaction” with the information they acquire.

The “information user” (in this case the postpartum woman) is the principal variable of the model. According to Wilson’s model, an information “need” determines the information system to consult and influence how information is utilized or exchanged. Wilson emphasizes that a user accesses many information systems or other information sources which could lead to satisfaction or dissatisfaction.

The model further indicates that the information user may personally use the acquired information seen as useful or exchange it with other individuals which he termed “information transfer”. Finally, Wilson (1999) adds that, in making use of acquired information, the perceived need of an individual may either be partially or fully satisfied, and this determines whether the information search is repeated. Figure 1 depicts Wilson’s model of information behaviour.

Wilson’s model of information behaviour. Source: Wilson (1999, p. 251).

2.6 Adapting Wilson’s Model of Information Behaviour to the Current Study

According to Jayamma and Mahesh (2020), the main variables are obtained from a theoretical framework to develop a strong basis for any research enquiry. As a result, the researcher mapped the objectives of the study to the main variables in Wilson’s (1999) model as displayed in Table 1, which presented a broad picture of the relationship between the study and the theoretical framework.

Level of knowledge about health issues

| Health Issue | No knowledge | Moderate knowledge | Adequate knowledge | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Breastfeeding | 36 | 25.9 | 48 | 34.5 | 55 | 39.6 | 139 | 100 |

| Infant behaviour | 42 | 30.2 | 51 | 36.7 | 46 | 33.1 | 139 | 100 |

| Baby’s development | 42 | 30.2 | 47 | 33.8 | 50 | 36.0 | 139 | 100 |

| Signs of newborn developmental problems | 48 | 34.5 | 46 | 33.1 | 45 | 32.4 | 139 | 100 |

| Childhood illness | 39 | 28.1 | 57 | 41.0 | 43 | 30.9 | 139 | 100 |

| Nutrition | 27 | 19.4 | 53 | 38.1 | 59 | 42.4 | 139 | 100 |

| Complications after delivery | 45 | 32.4 | 51 | 36.7 | 43 | 30.9 | 139 | 100 |

| Birth recovery and self-care | 47 | 33.8 | 41 | 29.5 | 51 | 36.7 | 139 | 100 |

| Intimacy with a partner after delivery | 46 | 33.1 | 42 | 30.2 | 51 | 36.7 | 139 | 100 |

| Contraceptive use | 51 | 36.7 | 41 | 29.5 | 47 | 33.8 | 139 | 100 |

| Mental health after delivery | 80 | 57.6 | 28 | 20.1 | 31 | 22.3 | 139 | 100 |

Source: Field Data (2022).

Linking the constructs of the framework to the objectives, the information needs attribute helped achieved objective 1, information-seeking behaviour helped achieved objective 2, and the remaining three objectives were tackled using the information sources, systems, and use attribute.

2.7 Research Methods

This study used the quantitative research approach to examine the HISB of women in the postpartum period in the Sunyani Municipal Hospital (SMH) as it helped to test Wilson’s model of information behaviour.

The research design for this study was a survey, and its usage provided the researcher with relevant data such as the demographic characteristics of the large number of postpartum women who attend the Post-Natal Clinic (PNC) at the SMH. In addition, standardized questions that were based on Wilson’s model of information behaviour were utilized.

2.8 Study Setting

The study was situated in the Sunyani municipal area, specifically, the SMH in the Bono region of Ghana.

The reason for the selection of SMH for this study is that according to Mohammed, Bonsing, Yakubu, and Wondong (2019), it is one of the referral centres for primary-level health care in the urban and rural communities of the middle belt of Ghana, and the records of the hospital indicate an average PNC attendance of 217 postpartum women every month (Health Information and Records Department, 2020). With this, there were enough women in the postpartum period available to be included in the sample.

2.9 Target Population and Sampling

In using the 6-month postpartum period, referred to as the delayed postpartum (Romano, Cacciatore, Giordano, & La Rosa, 2010) as a criterion for selecting mothers for the study, many prospective respondents (first-time mothers) were identified for the study. According to the records of the hospital, there is an average of 217 postpartum women who attend PNC every month. Therefore, the target population for the study was 217.

The sample for the study was selected by using the formula below as stated by Krejcie and Morgan (1970) to calculate the sample size:

where n = required sample size, x 2 = the table value of chi-square for 1 degree of freedom at the desired confidence level (3.841), N = the population size, P = the population proportion (assumed to be 0.50 which provided the maximum sample size), and e = the degree of accuracy expressed as a proportion (0.05).

Therefore, the sample size for first-time postpartum mothers was approximately 139. A convenience sampling technique was used to select first-time mothers for the study based on their availability (Creswell & Creswell, 2018).

Data for the study were gathered at the PNC unit within the hospital setting where the postpartum women bring their babies (once every month) for postnatal care.

2.10 Data Collection Instrument

A structured questionnaire was used to collect data for the study. The questionnaire was first piloted among 10 first-time mothers to ensure the internal consistency of the items and the improvement of questions (Creswell & Creswell, 2018).

-

Ethical consideration: The conduct of the study was guided by the research ethics policy of the University of Ghana (2022). To ensure voluntary participation, only respondents who wanted to participate in the study were selected, and they were free to withdraw anytime. In ensuring informed consent, permission was sought from the SMH, and the consent of respondents was sought after being briefed about the study.

3 Data Analysis and Discussion of Findings

The data collected in this study were processed and analysed using the Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) software version 23. All the responses from the respondents were coded before being entered into the SPSS software, and the data were analysed using descriptive statistics.

A total of 139 copies of the questionnaire were administered to the first-time mothers who attend PNC at the SMH; all of which were retrieved. Hence, there was a 100% response rate.

3.1 Demographic Information

This section solicited information related to the backgrounds of the respondents. Of the 139 responses for each, it was seen that with the ages, 69 (50%) were between 30 and 39 years, 59 (42%) were between 20 and 29 years, and 11 (8%) were between 40 and 49 years. Of this, 116 (84%) were married, 22 (15%) were single, and only 1 (1%) was divorced. Again, about their educational status, 131 (94%) had at least some form of formal education from basic to master’s degree, whereas 8 (6%) did not have any formal education. Finally, 112 (81%) were employed, whereas 27 (19%) were not.

3.2 Health Information Needs of Respondents

This section examined the health information needs of the respondents concerning issues about their health and that of their babies. It also examined the respondent’s level of knowledge in relation to some outlined health issues and sought to determine how important the outlined health issues were to the respondents.

3.2.1 Respondents’ Questions on Health Information Needs

The respondents were asked to indicate whether they had questions about their health as well as the well-being of their babies. It was seen that 91% of the respondents indicated that they have had questions about their health and that of their babies for which they required health information. However, 13 (9%) of the respondents indicated that no, they had not had any questions of that sort. Therefore, this showed that the majority of the respondents had some questions for which they required health information.

3.2.2 Frequency of Need for Information about the Health and Well-Being of Mother and Baby

The questions required the respondents to indicate how often they felt the need for information about their health as well as the well-being of their babies. Of the 139 responses, 70 (50.4%) indicated that they need that information sometimes, 29 (20.9%) stated always, 27 (19.4%) indicated most of the time, and 13 (9.4%) indicated that they never need such information.

3.2.3 Level of Knowledge about Health Issues

This section asked respondents to rate their level of knowledge concerning a list of health issues about their health and that of their newborn. This is presented in Table 1.

In Table 1, it can be seen that postpartum women had inadequate knowledge of mental health issues, contraceptive use, and signs of newborn developmental illness; moderate knowledge about issues concerning complications after delivery, childhood illness, baby’s development, and infant behaviour; and adequate knowledge about nutrition, breastfeeding, intimacy, and birth recovery.

3.2.4 Level of Importance of Health Issue

A follow-up was asked from the respondents to specify the level of importance of a list of health issues, and the summary of the responses showed that all the health issues were seen as extremely important to respondents with breastfeeding at 80.6%, nutrition at 74.8%, childhood illness at 72.7%, and signs of newborn developmental problems at 68.3% among others. The findings, thus, showed that although all the health issues were considered extremely important by the majority of postpartum women, breastfeeding was at the apex of the list and contraceptive use was at the lowest in the same category.

3.3 Sources of Health Information

This section sought to identify the sources where respondents searched for and obtain information about their health and that of their baby. It also required that respondents indicated the level of importance of each source and their most preferred source when searching for health information.

3.3.1 The First Source Consulted when in Need of Health Information

Here, the respondents were required to choose the first source they always consulted (from a list of sources) when they needed information about their health and that of their baby.

Of of the 139 responses received, the majority of the respondents 65 (47%) preferred to first consult a health professional when they needed information about their health, which was followed by family/friends with 64 (46%), although the difference is not so significant as compared to the internet 6 (4%) and social media 4 (3%).

3.3.2 Reasons for Choosing a Specific Source of Health Information Over Others

The respondents were asked to choose from a list of options, the various reasons that informed their decision to consult a particular source of health information, and of the 139 responses, a majority of 48 (34%) chose a source because of its trustworthiness, 33 (24%) chose as source as it always being available, 26 (19%) chose a source as it contains valuable information, 18 (13%) chose a source due to fast and minimum efforts, and 14 (10%) chose a source due low-cost requirements. Hence, the prime reason why respondents chose to consult a particular source of information was due to its trustworthiness, whereas the cost factor associated with accessing a source was the reason with the lowest concern to respondents.

3.3.3 Rating the Level of Importance of Sources of Health Information

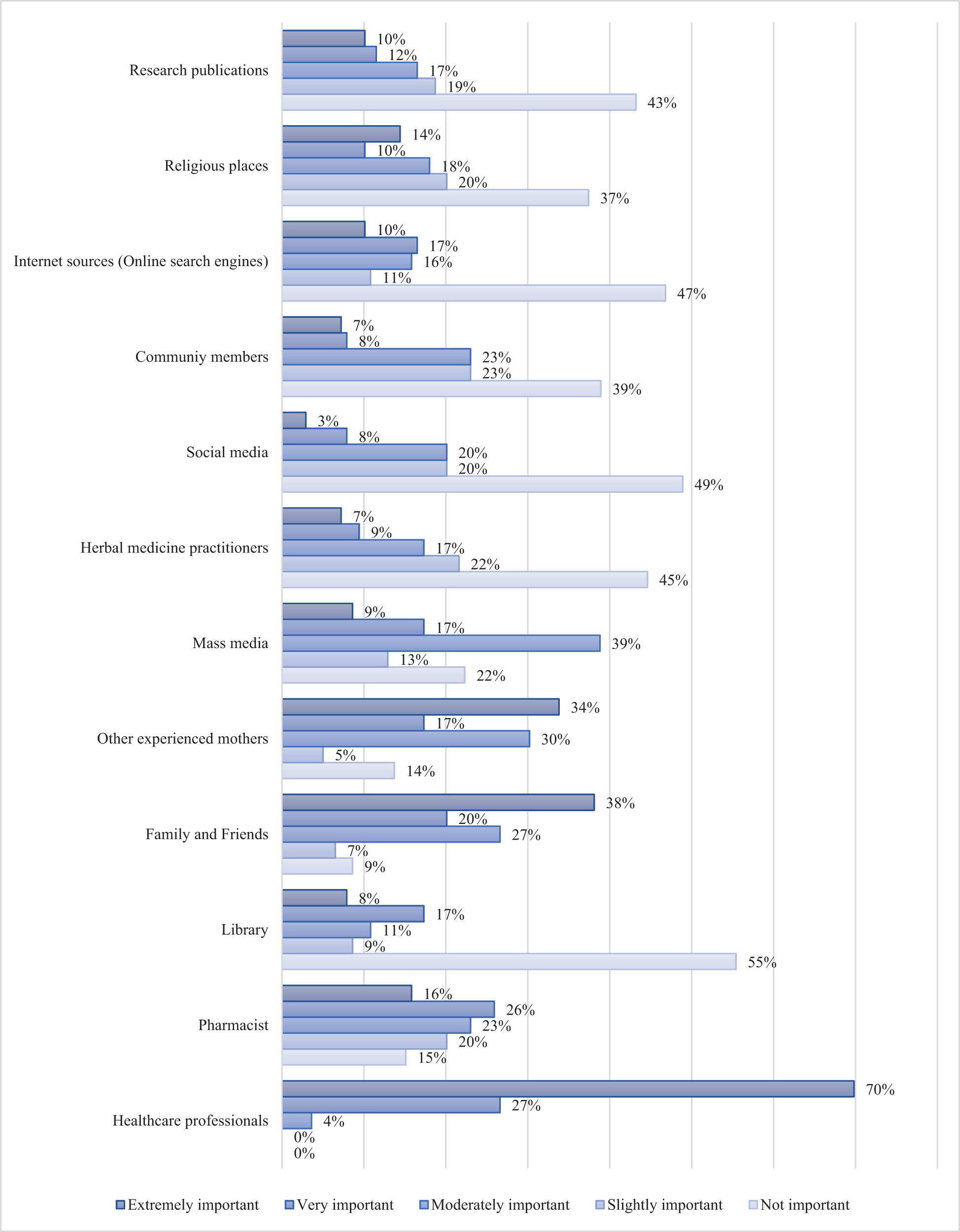

The respondents were asked to rate the level of importance of a list of sources of information in terms of searching for health information. Figure 2 provides a summary of the findings according to the responses given by respondents.

Level of importance of sources of information.

In Figure 2, the only sources of information that the majority of the respondents indicated as extremely important were health professionals and other experienced mothers.

3.4 HISB

In this section, respondents were required to indicate the rate at which they consulted certain sources of health information and the criteria they used in evaluating the sources

3.4.1 Frequency of Usage of Sources of Information

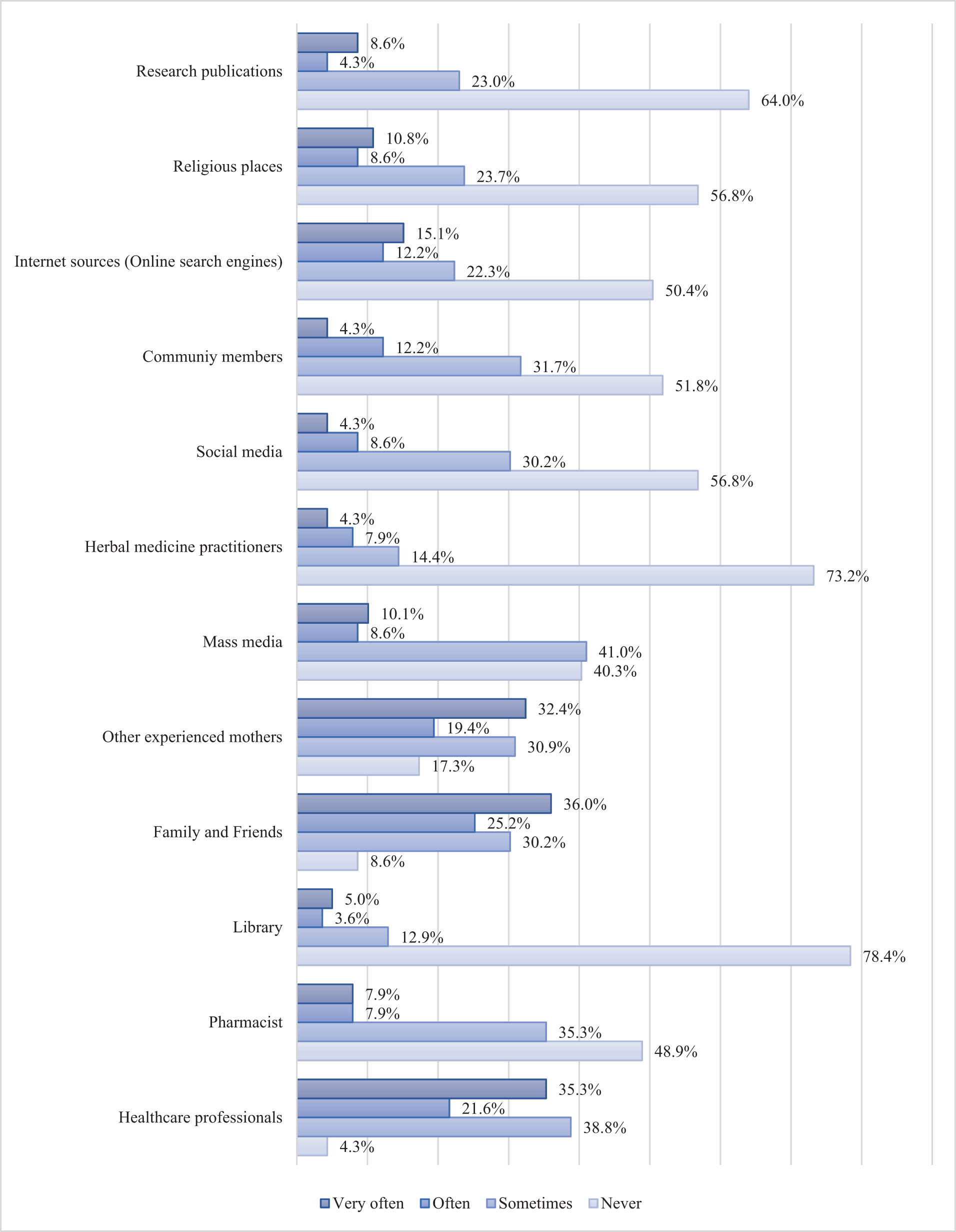

Having rated the level of importance of the health information sources to mothers, the respondents were required to indicate how often they consulted each source. Figure 3 gives a summary of the responses.

Frequency of usage of sources of information. Source: Field Data.

In Figure 3, while family/friends and other experienced mothers were mostly consulted by the majority of the respondents, the library and other sources were mostly never consulted.

3.5 Accessibility to Health Information by First-Time Mothers

In this section, the study sought to ascertain how possible or otherwise it was for respondents to access health information and the amount of time the respondents spent during information access.

3.5.1 Frequency of Access to Health Information

The respondents were asked to indicate how often they were able to access health information upon request, irrespective of the time. Of the 139 responses, 83 (60%) indicated that they always had access, 30 (21%) indicated most times, 25 (18%) indicated sometimes, and just 1 (1%) stated never. This showed that the majority of the respondents always had access to health information anytime there was a health need.

3.5.2 Time Spent During Information Access

There was a follow-up question that required respondents to specify the time they normally spent trying to access health information. It was revealed that of the 139 responses received that 74 (53%) spent seconds during information access, 57 (41%) spent minutes, 7 (5%) spent hours, and just 1 (1%) spent days. Thus, it took some seconds for the majority of the respondents to access health information.

3.6 Challenges/Barriers to Seeking Health Information

This section included questions that solicited information about the barriers that impeded access to health information by respondents. It also required that respondents rated the level of impact of the barriers to their access to health information.

First, it was determined that 80% of the respondents had ever encountered a challenge during their search for information, while 20% had never experienced any form of challenge during their search for health information.

3.6.1 Frequency of Facing Certain Barriers to Health Information Seeking

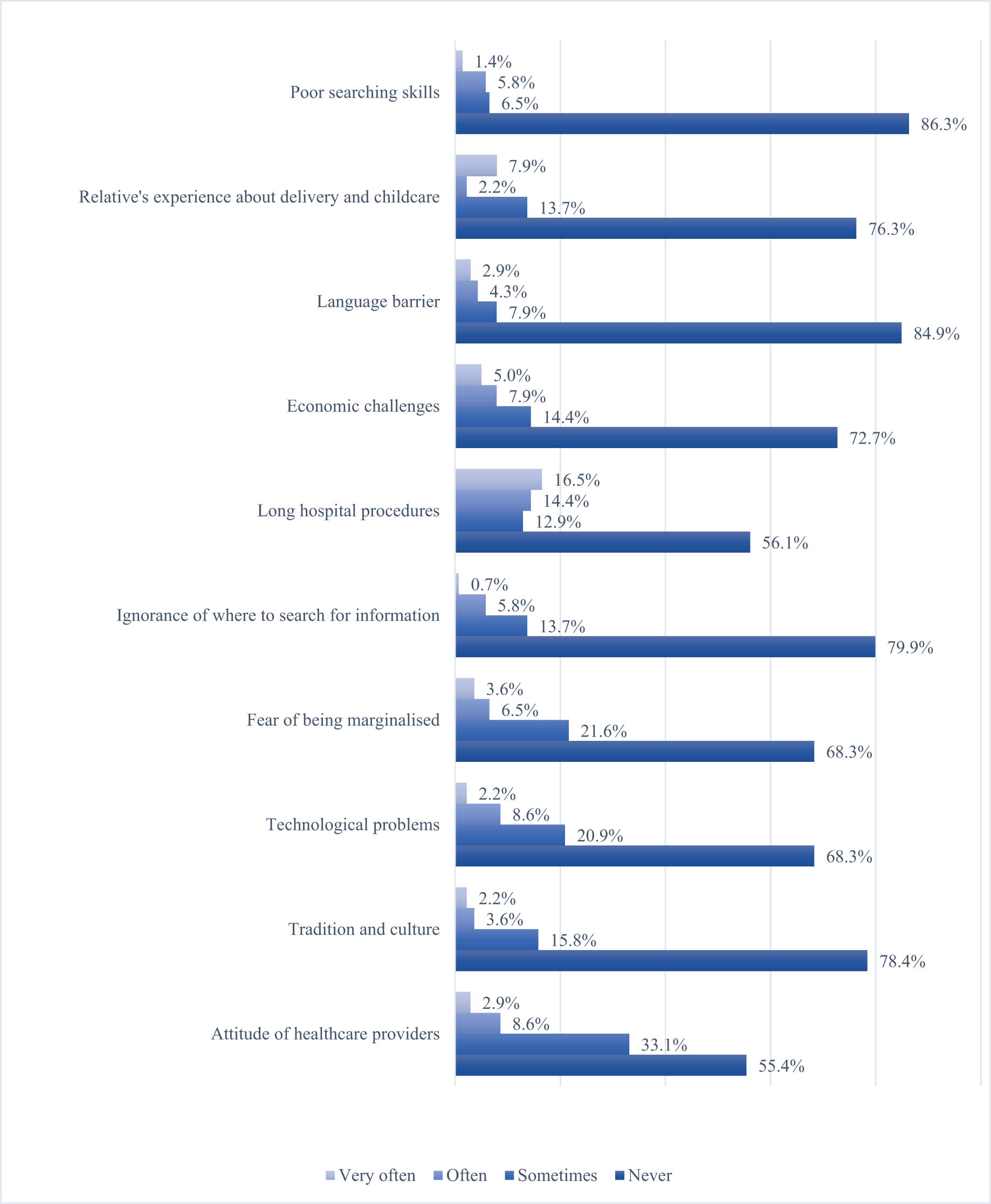

Having asked whether the respondents had ever faced any challenges during their search for health information after delivery, the respondents were required to indicate the frequency at which they faced certain barriers. The responses are summarized in Figure 4.

Frequency of barriers to health information seeking. Source: Field Data (2022).

It can be observed from Figure 4 that although some of the mothers had encountered some barriers during their search for information, the majority of the respondents had never encountered any of the barriers during their health information seeking.

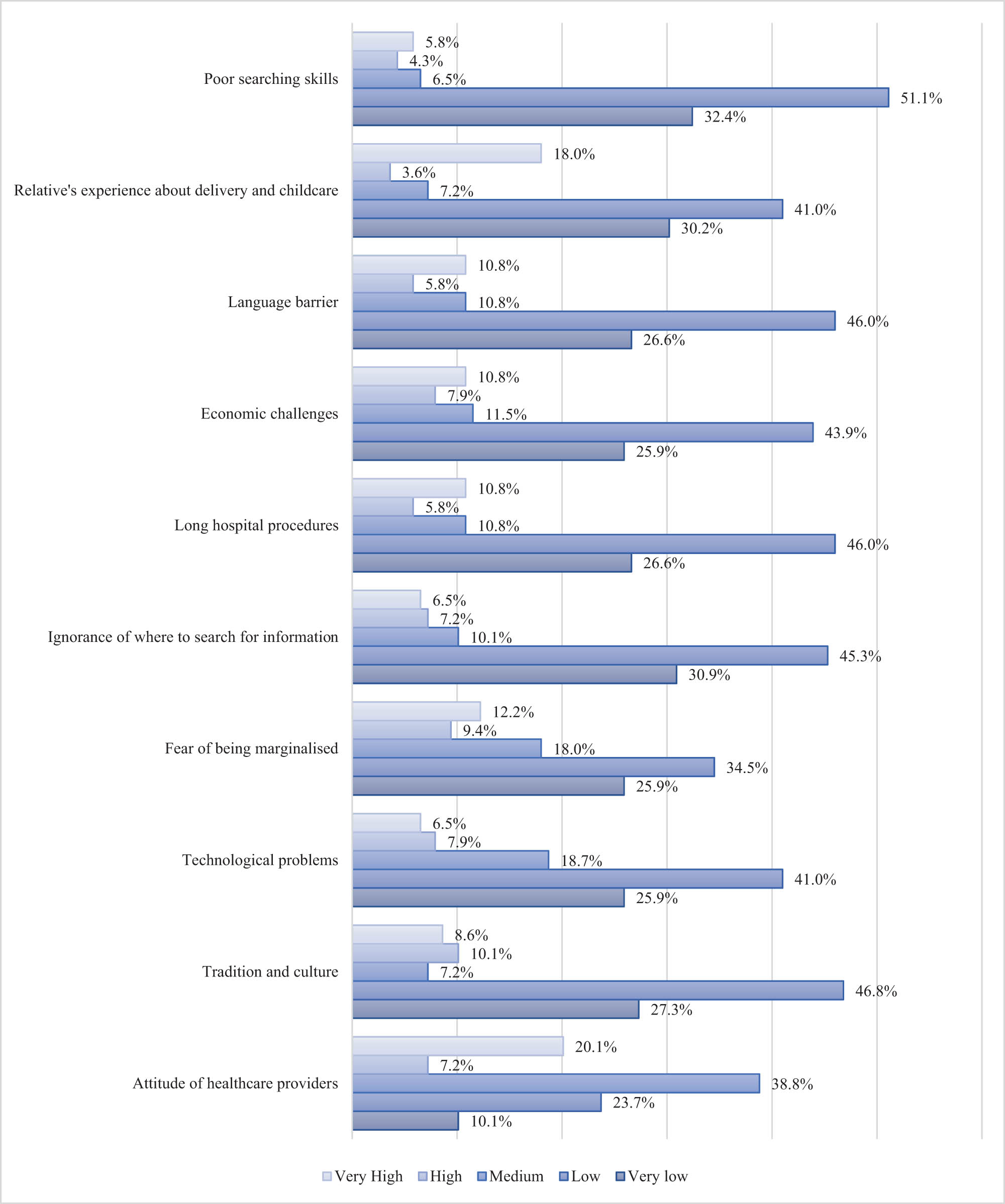

3.7 Impact of Barriers to Health Information Seeking

The respondent rated the level of impact of the barriers to their search for health information. Figure 5 shows that except for the attitude of healthcare professionals who had a medium impact on the information-seeking behaviour of respondents, the impact of all the other barriers was significantly low.

Impact of barriers to health information seeking. Source: Field Data (2022).

4 Discussion of Findings

4.1 Health Information Needs

It was discovered that the majority of first-time mothers had ever had questions about their health and the well-being of their newborns which made them seek health information. However, it was discovered that a handful of the women had never had any questions about their health and that of their babies since they gave birth. Some studies support the findings which revealed that the majority of mothers had adequate knowledge of nutrition (Agize, Jara, & Dejenu, 2017). Again, the study of Karim et al. (2019) corroborated the findings by revealing that women were denied the right to choose alternative delivery procedures (e.g., normal vaginal delivery or CS) during childbirth because they had inadequate knowledge about the delivery alternatives and its effect on their health. Also, the study by Al-Onizat (2019) confirmed the findings as it was revealed that parents had inadequate knowledge about the natural growth indicators of the first three years of their children’s lives

Again, there are quite a few studies that contradicted the findings of the study. For instance, the study of Rotich and Wolvaardt (2017) revealed that mothers (in the postpartum period) had inadequate knowledge about their baby’s needs (such as breastfeeding), baby’s growth and developmental progress, and self-management, although their findings that indicated that mothers had inadequate knowledge about delivery-related discomfort supported the findings of the study. Also, the study by Jama et al. (2020) revealed that mothers had inadequate knowledge about breastfeeding, whereas the study by Guerra-Reyes, Christie, Prabhakar, Harris, and Siek (2016) revealed that mothers had inadequate knowledge about sexual and mental health during postpartum.

4.2 Sources of Health Information

It was discovered that whenever first-time postpartum mothers needed health information, the majority consulted health professionals, followed by those who first consulted family/friends. Again, the findings revealed that the reason why first-time mothers first consulted a particular source for health information was that it was trustworthy. These findings were supported by Guerra-Reyes et al. (2016) who revealed that the most preferred source of information was face-to-face interaction with the healthcare professional. Again, the findings were supported by Agyei, Adu, Yeboah, and Tachie-Donkor (2018) as they revealed that the entire population of adolescent mothers and adult postpartum mothers had a negative perception of the role of libraries in the dissemination of health information.

Other studies, however, refuted the findings as Dol et al. (2022) discovered that while family/friends were the most preferred source of information, Internet sources were the most valued source of information. The findings of the study disagreed with that of Obasola and Mabawonku (2017) who showed that the most preferred source of information was mobile phones followed by mass media and the Internet.

4.3 HISB

The findings showed that the majority of first-time mothers consulted family/friends very often, unlike the health professionals or mass media which were sometimes consulted. The findings of the study agreed with that of Rowley, Johnson, and Sbaffi (2017) which revealed that women did not pay particular attention to the accuracy and comprehensiveness of information.

In contrast to the study, Sun, Zhang, Gwizdka, and Trace (2019) discovered that trustworthiness, objectivity, and expertise of sources of information were the most widely reported evaluation criteria. Again, the study by Greyson (2017) disputed the study findings by revealing that young parents evaluated health information by checking for credibility, relevance, accuracy, timeliness, trustworthiness, and the applicability of the information to one’s situation.

4.4 Accessibility to Health Information

The findings revealed that majority of the first-time mothers were always able to access health information compared to those who were able to access health information most time. In addition, the findings concerning the time spent accessing health information indicated that while most of the first-time mothers spent seconds accessing health information, no respondent spent weeks or months in their search for health information.

The findings are inconsistent with the study by Odini (2016) which established that there was inadequate time for the majority of the women in Kenya to access health information. Again, contrary to the findings of this study, Mwangakala (2021) revealed that most women did not have any type of media for maternal health information.

4.5 Challenges/Barriers to Seeking Health Information Seeking

This study discovered that first-time mothers encountered challenges during their search for health information. The majority of the first-time mothers indicated that the attitude of healthcare providers, tradition and culture, technological problems, and fear of being marginalized, among others did not strongly pose a challenge in health information seeking. The findings of this study were in contrast to that of Lee (2018), which revealed that Korean mothers tended to be strongly influenced by their culture and beliefs in search for health information. Again, the study by Mulauzi and Daka (2018) refuted the findings of the study as it revealed that the challenges faced by postpartum women included inadequate human resources, lack of information, distance, language barrier, illiteracy, poverty, inadequate services, cultural practices, and poor attitudes of healthcare workers towards women. Also, a previous study disagreed with the study findings by revealing that the major sources of dissatisfaction among mothers who had just delivered were neglect, unfriendliness, and ineffective communication by caregivers (or healthcare professionals) such as nurses.

5 Conclusion and Recommendations

The aim of this study was to investigate the health information needs and the information-seeking behaviour of first-time mothers in the SMH.

The state of motherhood presents with it certain changes that are new to the woman who will require some form of health information to enable her to cope with her new self and cater for her infant. It is only when this need for health information is provided, and challenges impeding access to health information are reduced to the barest minimum is where mortality rates will reduce.

5.1 Recommendations

The following recommendations are hereby proposed based on the findings of the study:

Health authorities should ensure that all maternal educational programmes are recorded and replayed to mothers during their visits to the health facility for PNC services to help with education anytime.

Health authorities should factor in caregivers during the designing of maternal educational programs which will equip the caregivers with adequate knowledge on how to take care of new mothers.

Public Libraries must collaborate with health authorities to make known health information in a repackaged form through selective dissemination of information.

Public Libraries should partner with the management of health facilities to educate postpartum mothers on how to use the various evaluation criteria to evaluate health information from different sources.

Ghana Health Service in conjunction with the Ministry of Health should organize refresher courses and training programs at regular intervals for healthcare professionals.

The Ministry of Health should establish a secure online environment where postpartum mothers can gain access to credible information to address their health concerns

Healthcare professionals should conduct regular patient surveys to enable them to identify the challenges postpartum women face in the search for health information at health facilities.

The Government of Ghana through the Ministry of Health in collaboration with the Ghana Library Authority should develop a policy that compels all health facilities to establish libraries where patients who visit the health facility could have access to reliable information about their health.

6 Limitations and Future Research

The study was limited to the health information needs and the information-seeking behaviour of first-time mothers who fall within the 6 months postpartum period. Therefore, the results cannot be generalized to include all first-time mothers who fall within the 1-year postpartum period. Future research should consider all postpartum mothers who fall within the 1-year postpartum period.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

APPENDIX A: QUESTIONNAIRE

This questionnaire is to gather data on your knowledge or thought on the topic “Whom do I ask? First-time postpartum mothers in a developing economy.” Your thought and truthful responses will be gladly appreciated. Thank You.

Instructions

Please tick [ ] in the appropriate space provided below and supply answers where required.

Section A: Demographic Characteristics

Age range: a. 19 and below [ ] b. 20–29 [ ] c. 30–39 [ ] d. 40–49 [ ] e. 50 and above [ ]

Marital Status: a. Single [ ] b. Married [ ] c. Divorced [ ]

Highest educational level

a. No formal education [ ] b. Primary to JHS [ ] c. SSCE [ ] d. Diploma [ ] e. Degree [ ] f. Masters [ ] g. PHD [ ] e. Others.

Occupation: a. unemployed [ ] b. self-employed [ ] c. civil servant [ ]

Section B: Health Information Needs

This sub-section examines your health information needs. Health information needs are information you require to answer the questions or problems you have about your health and that of your baby.

Have you ever had questions about your health or that of your baby for which you required information from somewhere? a. YES [ ] b. NO [ ]

How often have you feel the need for information about your health and that of your baby?

a. Never [ ] b. Sometimes [ ] c. Most of the time [ ] d. Always [ ]

How will you rate your level of knowledge about the following issues using the scale provided?

No. Health issues No knowledge Moderate knowledge Adequate knowledge a. Breast feeding and other ways to feed your child 1 2 3 b. Infant behaviour (e.g., sleeping, crying, sucking, hearing) 1 2 3 c. Baby’s development (e.g., teething, crawling) 1 2 3 d. Signs of newborn developmental problems 1 2 3 e. Childhood illness 1 2 3 f. Nutrition (for baby and yourself) 1 2 3 g. Complications after delivery (e.g., urinary infections) 1 2 3 h. Birth recovery and self-care (e.g., weight loss, C-section recovery, stretch marks) 1 2 3 i. Intimacy with husband after delivery 1 2 3 j. Contraceptives use after delivery and planning next pregnancy 1 2 3 k. Mental health after delivery (e.g., depression) 1 2 3 How important are the following information to your health and that of your baby using the scale below? Kindly circle the number you deem appropriate.

No. Health issues Not important (NI) Slightly important (SI) Moderately important (MI) Very important (VI) Extremely important (EI) a. Breast feeding and other ways to feed your child 1 2 3 4 5 b. Infant behaviour (e.g., sleeping, crying, sucking, hearing) 1 2 3 4 5 c. Signs of newborn developmental problems 1 2 3 4 5 d. Childhood illness 1 2 3 4 5 e. Nutrition (for baby and yourself) 1 2 3 4 5 f. Complications after delivery (e.g., infections, excessive bleeding) 1 2 3 4 5 g. Birth recovery and self-care (e.g., weight loss, C-section recovery, stretch marks) 1 2 3 4 5 h. Intimacy with husband after delivery 1 2 3 4 5 i. Contraceptives use after delivery and planning next pregnancy 1 2 3 4 5 j. Mental health after delivery (e.g., depression) 1 2 3 4 5 Section C: Sources of Health Information

This sub-section examines where you obtain information about your health and that of your baby

When in need of health information, which source do you consult first? Please tick only one

a. Health professional [ ] b. Family/Friends [ ] c. Internet [ ] d. Social Media [ ]

Why do you choose this particular source in Question 10? Tick as many as apply

a. It is always available [ ] b. It is trust worthy [ ] c. It is fast and requires minimum effort to obtain information [ ] d. It does not involve high cost to obtain information [ ] e. It contains valuable information [ ]

With reference to Question 10. What other sources of information do you choose when in need of health information?

a. Health professional [ ] b. Family/friends [ ] c. Internet [ ] d. Social media [ ] e. Other, please specify...........

Rate the importance of the following sources of information. Kindly circle the number you deem appropriate.

No. Information source NI SI MI VI EI a. Healthcare professionals (e.g., doctors, nurses, midwives) 1 2 3 4 5 b. Pharmacist 1 2 3 4 5 c. Library (i.e., physical, or online) 1 2 3 4 5 d. Family/friends 1 2 3 4 5 e. Other experienced mothers 1 2 3 4 5 f. Mass media (radio/TV stations, newspapers) 1 2 3 4 5 g. Herbal medicine practitioners 1 2 3 4 5 h. Social media (e.g., Facebook, WhatsApp, Twitter) 1 2 3 4 5 i. Community members or social group 1 2 3 4 5 j. Online search engines (e.g., Google search). 1 2 3 4 5 k. Internet/online sources (e.g., the websites) 1 2 3 4 5 l. Religious places (e.g., churches, mosque, shrine) 1 2 3 4 5 m. Research publications 1 2 3 4 5 Section D: Health Information Seeking Behaviour

How many times do you seek health information from these sources using the scale provided? Kindly circle the number you deem appropriate.

No. Information source Never Sometimes Often Very often a. Healthcare professionals (e.g., doctors, nurses, midwives) 1 2 3 4 b. Pharmacist 1 2 3 4 c. Library (i.e., physical, or online) 1 2 3 4 d. Family/friends 1 2 3 4 e. Other experienced mothers 1 2 3 4 f. Mass media (radio/TV stations, newspaper) 1 2 3 4 g. Herbal medicine practitioners 1 2 3 4 h. Social media (e.g., Facebook, WhatsApp, Twitter) 1 2 3 4 i. Community members 1 2 3 4 j. Internet (e.g., health websites, websites for mothers) 1 2 3 4 k. Religious places (e.g., churches, mosque, shrine) 1 2 3 4 l. Research publications 1 2 3 4 How often do you use any of these methods to evaluate (or check) the truthfulness of the health information acquired using the scale provided? Kindly circle the number you deem appropriate.

No. Evaluation methods Never Sometimes Often Very often a. Discuss information with healthcare professionals (e.g., midwife) 1 2 3 4 b. Check the qualification of the writer of the information 1 2 3 4 c. Check whether the writer has enough experience or expertise about the issue 1 2 3 4 d. Check whether there are spelling mistakes in the information provided 1 2 3 4 e. Find out whether the information talk about facts, or it portrays the writer’s opinion 1 2 3 4 f. Check if other writers share the same view 1 2 3 4 g. Check whether the information relates to the topic 1 2 3 4 h. Find out if the information has enough detail to give you adequate understanding 1 2 3 4 i. Compare the information with information from other trusted sources 1 2 3 4 j. Check when the information was written 1 2 3 4 k. Check whether the information is current 1 2 3 4 l. Check whether the information is a new version of an old one 1 2 3 4 m. Check whether the information deals specifically with the topic being researched 1 2 3 4 n. Find out the reason why the information was written 1 2 3 4 o. Find out who the information was written for 1 2 3 4 p. Check out if the information has some biases 1 2 3 4 q. Check whether the information can be trusted 1 2 3 4 r. Consider whether you really need the information 1 2 3 4 s. Check whether the information has enough details 1 2 3 4 Section E: Accessibility to Health Information

Are you able to obtain health information any time you seek it?

a. Never [ ] b. Sometimes [ ] c. Most times [ ] d. Always [ ]

How long does it take to obtain health information you need it?

a. Seconds [ ] b. Minutes [ ] c. Hours [ ] d. Days [ ] f. Weeks [ ] g. Months [ ]

Section F: Challenges in Seeking Health Information Seeking

Do you sometimes encounter any challenge while searching for health information?

a. Yes [ ] b. No [ ]

How often has the following made your search for health information difficult using the scale provided? Kindly circle the number you deem appropriate.

No. Barriers Never Sometimes Often Very often a. Attitude of healthcare providers (e.g., nurses, midwives) 1 2 3 4 b. Tradition and culture (e.g., beliefs, community/family practices) 1 2 3 4 c. Technology (e.g., internet, network problems) 1 2 3 4 d. Fear of being marginalized (or laughed at or disgraced) 1 2 3 4 e. Ignorance of where to search for information 1 2 3 4 f. Long hospital procedures 1 2 3 4 g. Economic challenges (e.g., transportation, poverty) 1 2 3 4 h. Language barrier (i.e., lack of understanding) 1 2 3 4 i. Relative’s experience about delivery and childcare 1 2 3 4 j. Poor searching skills 1 2 3 4 Rate the impact of the following barriers to your search for health information.

| No. | Barriers | Very low | Low | Medium | High | Very high |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a. | Attitude of healthcare providers (e.g., nurses, midwives) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| b. | Tradition and culture (e.g., beliefs, community/family practices) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| c. | Technology (e.g., Internet, network problems) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| d. | Fear of being marginalized (or laughed at or disgraced) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| e. | Ignorance of where to search for information | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| f. | Long hospital procedures | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| g. | Economic challenges (e.g., transportation, poverty) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| h. | Language barrier (i.e., lack of understanding) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| i. | Relative’s experience about delivery and childcare | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| j. | Poor searching skills | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

Thank you.

References

Abebe, R., Hill, S., Vaughan, J. W., Small, P. M., & Schwartz, H. A. (2019). Using search queries to understand health information needs in Africa. Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social-Media, 13(1), 3–14.10.1609/icwsm.v13i01.3360Search in Google Scholar

Abubakar, A. B., & Harande, Y. (2010). A snapshot of information seeking behaviour literature in health science: A bibliometric approach. Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal), 368, 1–8.Search in Google Scholar

Agize, A, Jara, D., & Dejenu, G. (2017). Level of knowledge and practice of mothers on minimum dietary diversity practices and associated factors for 6–23-month-old children in Adea Woreda, Oromia, Ethiopia Andualem. BioMed Research International, 2017, 1–9.10.1155/2017/7204562Search in Google Scholar

Agyei, D. D., Adu, S. M., Yeboah, E. A., & Tachie-Donkor, G. (2018). Establishing the knowledge of health information among adolescent postpartum mothers in rural communities in the Denkyembour District, Ghana. Advances in Research, 14(1), 1–8.10.9734/AIR/2018/39939Search in Google Scholar

Ahn, S., & Corwin, E. J. (2015). The association between breastfeeding, the stress response, inflammation, and postpartum depression during the postpartum period: Prospective cohort study. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 52, 1585–1590.10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2015.05.017Search in Google Scholar

Al-Onizat, S. H. H. (2019). The effectiveness of an educational program in enhancing parents’ level of knowledge about normal growth indicators in the development of children and determining the indicators which delay development in children from birth to three years old. Educational Research and Reviews, 14(9), 300–309.10.5897/ERR2019.3719Search in Google Scholar

Ansah-koi, K. (2013). Health seeking behaviour on the internet: A study of graduate students of the University of Ghana. University of Ghana. http://ugspace.ug.edu.gh/.Search in Google Scholar

Boadi, B. (2018). Information needs of women undergoing treatment and management of breast cancer a study of 37 Military Hospital and Sweden-Ghana Medical Centre. (Ph.D. dissertation). University of Ghana, Ghana.Search in Google Scholar

Corrarino, J. E. (2013). Health literacy and women’s health: Challenges and opportunities. Journal of Midwifery Women’s Health, 58(3), 257–264.10.1111/jmwh.12018Search in Google Scholar

Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2018). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approach (5th ed.). Los Angeles: Sage.Search in Google Scholar

Dol, J., Richardson, B., Aston, M., McMillan, D., Murphy, G. T., & Campbell-Yeo, M. (2022). Health information seeking in the postpartum period: A cross-sectional survey. Journal of Neonatal Nursing, 28(2), 118–122.10.1016/j.jnn.2021.08.008Search in Google Scholar

Galvão, A., Braga, A. C., Gonçalves, D. R., Guimarães, J. M., & Braga, J. (2016). Sepsis during pregnancy or the postpartum period. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 36(6), 735–743.10.3109/01443615.2016.1148679Search in Google Scholar

Greyson, D. (2017). Health information practices of young parents. Journal of Documentation, 73(5), 778–802.10.1108/JD-07-2016-0089Search in Google Scholar

Guerra-Reyes, L., Christie, V. M., Prabhakar, A., Harris, A. L., & Siek, K. A. (2016). Postpartum health information seeking using mobile phones: Experiences of low-income mothers. Maternal Child Health Journal, 20, 13–21.10.1007/s10995-016-2185-8Search in Google Scholar

Health Information and Records Department. (2020). Health Information Records. Sunyani Municipal Hospital.Search in Google Scholar

Jaafar, N. I., Ainin, S., & Yeong, M. W. (2017). Why bother about health? A study on the factors that influence health information seeking behaviour among Malaysian healthcare consumers. International Journal of Medical Informatics, 104, 38–44.10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2017.05.002Search in Google Scholar

Jacobs, W., Amuta, A. O., & Jeon, K. C. (2017) Health information seeking in the digital age: An analysis of health information seeking behavior among US adults. Cogent Social Sciences, 3(1), 1–11.10.1080/23311886.2017.1302785Search in Google Scholar

Jama, A., Gebreyesus, H., Wubayehu, T., Gebregyorgis, T., Teweldemedhin, M., Berhe, T., & Berhe, N. (2020). Exclusive breastfeeding for the first six months of life and its associated factors among children age 6-24 months in Burao district, Somaliland. International Breastfeeding Journal, 15(1), 1–8.10.1186/s13006-020-0252-7Search in Google Scholar

Jang, C. I. (2019). Health information seeking among women in a Peri-Urban Community: A study of market women in Madina. (Doctoral dissertation). University of Ghana.Search in Google Scholar

Javadifar, N., Majlesi, F., Nikbakht, A., Nedjat, S. & Montazeri, A. (2016). Journey to motherhood in the first year after childbirth. Journal of Family and reproductive Health, 10(3), 146–153.Search in Google Scholar

Jayamma, K. V., & Mahesh, G. T. (2020). Information seeking behaviour of post graduate students of government science college, Bangalore: A study. Asian Journal of Information Science & Technology (AJIST), 10(1), 1–5.10.51983/ajist-2020.10.1.303Search in Google Scholar

Kamali, S., Ahmadian, L., Khajouei, R., & Bahaadinbeigy, K. (2018). Health information needs of pregnant women: Information sources, motives and barriers. Health Information and Libraries Journal, 35(1), 24–37.10.1111/hir.12200Search in Google Scholar

Kamyar, S., Kazerani, M., Shekofteh, M., & Jambarsang, S. (2023). Health information seeking behaviour in academic population and its relationship with carcinophobia: An analytical survey on Recognizing the problems and barriers to obtaining the required information resulting from fear of cancer. International Journal of Information Science and Management, 21(1), 275–288. doi: 10.22034/ijism.2022.1977703.0.Search in Google Scholar

Karim, A., Ahmed, S. I., Ferdous, J., Islam, B. Z., Tegegne, H. A., & Aktar, B. (2019). Assessing informed consent practices during normal vaginal delivery and immediate postpartum care in tertiary-level hospitals of Bangladesh. European Journal of Midwifery, 3(10), 1–5.10.18332/ejm/109311Search in Google Scholar

Kilpatrick, S., King, T. J., & Willis, K. (2015). Not just a fisherman’s wife: Women’s contribution to health and wellbeing in commercial fishing. Australian Journal of Rural Health, 23, 62–66.10.1111/ajr.12129Search in Google Scholar

Krejcie, R. V., & Morgan, D. W. (1970). Determining sample size for research activities. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 30, 607–610.10.1177/001316447003000308Search in Google Scholar

Lee, H. S. (2018). A comparative study on the health information needs, seeking and source preferences among mothers of young healthy children: American mothers compared to recent immigrant Korean mothers. Information Research: An International Electronic Journal, 23(4), 1–28.Search in Google Scholar

Madge, O., Marincaș, A. M., Daha, C., & Simion, L. (2023). Health information seeking behaviour and decision making by patients undergoing breast cancer surgery: A qualitative study. Health Information & Libraries Journal, 1–12. doi: 10.1111/hir.12480.Search in Google Scholar

Makinde, O. B. (2018). Information needs and information-seeking behavior of researchers in an industrial research institute in Nigeria. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of South Africa, Pretoria, South Africa.Search in Google Scholar

Markwei, E., & Rasmussen, E. (2015). Everyday life information-seeking behavior of marginalized youth: A qualitative study of urban homeless youth in Ghana. International Information & Library Review, 47(1–2), 11–29.10.1080/10572317.2015.1039425Search in Google Scholar

Martinović, V., Kim, S. U., & Katavić, S. S. (2023). Study of health information needs among adolescents in Croatia shows distinct gender differences in information seeking behaviour. Health Information & Libraries Journal, 40(1), 70–91. doi: 10.1111/hir.12369.Search in Google Scholar

Mills, A., & Todorova, N. (2016). An integrated perspective on factors influencing online health information seeking behaviours. ACIS 2016 Proceedings, 83.Search in Google Scholar

Mohammed, S., Bonsing, I., Yakubu, I., & Wondong, W. P. (2019). Maternal obstetric and sociodemographic determinants of low birth weight: A retrospective cross-sectional study in Ghana. Reproductive Health, 16(70), 1–8.10.1186/s12978-019-0742-5Search in Google Scholar

Mulauzi, F., & Daka, K., (2018). Maternal health information needs of women: A survey of literature. The Journal of Lexicography and Terminology, 2(1), 1–15.Search in Google Scholar

Mwangakala, H. A. (2021). Accessibility of maternal health information and its influence on maternal health preferences in rural Tanzania: A case study of Chamwino District. South African Journal of Information Management, 23(1), 1–9.10.4102/sajim.v23i1.1353Search in Google Scholar

Obasola, O. I., & Mabawonku, I. M. (2017). Women’s use of information and communication technology in accessing maternal and child health information in Nigeria. African Journal of Library, Archives and Information Science, 27(1), 1–15.Search in Google Scholar

Odini, S. (2016). Accessibility and utilization of health information by rural women in Vihiga county, Kenya. International Journal of Science and Research (IJSR), 5(7), 827–834.10.21275/v5i7.NOV164666Search in Google Scholar

Orlu, D. A., Mafo, I. H., & Tochukwu, N. T. (2017). Perceived emotions in the information seeking behaviour of Manchester Metropolitan University students. Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal), 1534.Search in Google Scholar

Owen, M. D., Colburn, E., Tetteh, C., & Srofenyoh, E. K. (2020). Postnatal care education in health facilities in Accra, Ghana: Perspectives of mothers and providers. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 20(664), 1–10.10.1186/s12884-020-03365-1Search in Google Scholar

Owusu-Aidoo, P. (2019). Factors influencing the utilisation of family planning methods among postpartum women at the 37 Military Hospital of Ghana. (Doctoral dissertation). University of Ghana, Ghana.Search in Google Scholar

Ramsay, I., Peters, M., Corsini, N., & Eckert, M. (2017). Consumer health information needs and preferences: A rapid evidence review. Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. http://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/.10.1016/j.pec.2017.04.005Search in Google Scholar

Romano, M., Cacciatore, A., Giordano, R., & La Rosa, B. (2010). Postpartum period: Three distinct but continuous phases. Journal of Prenatal Medicine, 4(2), 22–25.Search in Google Scholar

Rotich, E., & Wolvaardt, L. (2017). A descriptive study of the health information needs of Kenyan women in the first 6 weeks postpartum. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 17(1), 385.10.1186/s12884-017-1576-1Search in Google Scholar

Rowley, J., Johnson, F., & Sbaffi, L. (2017). Gender as an influencer of online health information seeking and evaluation behavior. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 68(1), 36–47.10.1002/asi.23597Search in Google Scholar

Sun, Y., Zhang, Y., Gwizdka, J., & Trace, C. B. (2019). Consumer evaluation of the quality of online health information: Systematic literature review of relevant criteria and indicators. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 21(5), e12522.10.2196/12522Search in Google Scholar

Tewell, E. (2015). A decade of critical information literacy: A review of the literature. Communications in Information Literacy, 9(1), 24–43.10.15760/comminfolit.2015.9.1.174Search in Google Scholar

Umar, A., Umar, S., & Hussaini, M. (2020). Information needs and information seeking behaviour of students in College of Nursing and Midwifery Gombe, Gombe State. International Journal of Applied Technologies in Library and Information Management, 6(2), 67–72.Search in Google Scholar

University of California. (2021). Patient education: Evaluating health information. https://www.ucsfhealth.org/education/evaluating-health-information.Search in Google Scholar

University of Ghana. (2022). Research ethics policy. University of Ghana. https://orid.ug.edu.gh/sites/orid.ug.edu.gh/files/UG%20Research%20Ethics%20Policy.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

Wang, T., Zhou, X., Ni, Y., & Pan, Z. (2020). Health information needs regarding diabetes mellitus in China: An internet-based analysis. BMC Public Health, 20(990), 1–9.10.1186/s12889-020-09132-3Search in Google Scholar

Wichaidit, W., Alam M., Halder A. K., Unicomb L., Hamer D. H., & Ram P. K. (2016). Availability and quality of emergency obstetric and newborn care in Bangladesh. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 95, 298–306.10.4269/ajtmh.15-0350Search in Google Scholar

Wilson, T. D. (1999). Models in information behaviour research. Journal of Documentation, 55(3), 249–270.10.1108/EUM0000000007145Search in Google Scholar

Zivoder, I., Martic-Biocina, S., Veronek, J., Ursulin-Trstenjak, N., Sajko, M., & Paukovic, M. (2019). Mental disorders/difficulties in the postpartum period. Psychiatr Danub, 31, 338–344.Search in Google Scholar

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- An Empirical Evaluation of Research on “Library Management” at the Doctoral Level in India: A Study of the Last 50 Years from 1971 to 2020

- Social Unrest Prediction Through Sentiment Analysis on Twitter Using Support Vector Machine: Experimental Study on Nigeria’s #EndSARS

- Measuring the Concept of PID Literacy: User Perceptions and Understanding of PIDs in Support of Open Scholarly Infrastructure

- Culturally Responsive Librarians: Shifting Perspectives Toward Racial Empathy

- Farmers’ Use of the Mobile Phone for Accessing Agricultural Information in Haryana: An Analytical Study

- How European Research Libraries Can Support Citizen-Enhanced Open Science

- Research Image Management Practices Reported by Scientific Literature: An Analysis by Research Domain

- Adding Perspective to the Bibliometric Mapping Using Bidirected Graph

- Students’ Perspectives on the Application of Internet of Things for Redesigning Library Services at Kurukshetra University

- Whom Do I Ask? First-Time Postpartum Mothers in a Developing Economy

- The Effectiveness of Software Designed to Detect AI-Generated Writing: A Comparison of 16 AI Text Detectors

- Requirements of Digital Archiving in Saudi Libraries in the Light of International Standards: King Fahad National Library as a Model

- Analyzing Hate Speech Against Women on Instagram

- Adequacy of LIS Curriculum in Response to Global Trends: A Case Study of Tanzanian Universities

- COVID-19 Emergency Remote Teaching: Lessons Learned from Five EU Library and Information Science Departments

- Review Article

- Assessing Diversity in Academic Library Book Collections: Diversity Audit Principles and Methods

- Communications

- Twitter Interactions in the Era of the Virtual Academic Conference: A Comparison Between Years

- The Classification of Q1 SJR-Ranked Library and Information Science Journals by an AI-driven “Suspected Predatory” Journal Classifier

- Scopus-Based Study of Sustainability in the Syrian Higher Education Focusing on the Largest University

- Letter to the Editor

- Most Preprint Servers Allow the Publication of Opinion Papers

- SI Communicating Pandemics: COVID-19 in Mass Media

- COVID-19 in Mass Media: Manufacturing Mass Perceptions of the Virus among Older Adults

- Topical Issue: TI Information Behaviour and Information Ethics

- A Compass for What Matters: Applying Virtue Ethics to Information Behavior

- Studies on Information Users and Non-Users: An Alternative Proposal

- Ethical Issues of Human Information Behaviour and Human Information Interactions

- Ethics and Social Responsibility in Information Behavior, an Interdisciplinary Research in Uruguay

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- An Empirical Evaluation of Research on “Library Management” at the Doctoral Level in India: A Study of the Last 50 Years from 1971 to 2020

- Social Unrest Prediction Through Sentiment Analysis on Twitter Using Support Vector Machine: Experimental Study on Nigeria’s #EndSARS

- Measuring the Concept of PID Literacy: User Perceptions and Understanding of PIDs in Support of Open Scholarly Infrastructure

- Culturally Responsive Librarians: Shifting Perspectives Toward Racial Empathy

- Farmers’ Use of the Mobile Phone for Accessing Agricultural Information in Haryana: An Analytical Study

- How European Research Libraries Can Support Citizen-Enhanced Open Science

- Research Image Management Practices Reported by Scientific Literature: An Analysis by Research Domain

- Adding Perspective to the Bibliometric Mapping Using Bidirected Graph

- Students’ Perspectives on the Application of Internet of Things for Redesigning Library Services at Kurukshetra University

- Whom Do I Ask? First-Time Postpartum Mothers in a Developing Economy

- The Effectiveness of Software Designed to Detect AI-Generated Writing: A Comparison of 16 AI Text Detectors

- Requirements of Digital Archiving in Saudi Libraries in the Light of International Standards: King Fahad National Library as a Model

- Analyzing Hate Speech Against Women on Instagram

- Adequacy of LIS Curriculum in Response to Global Trends: A Case Study of Tanzanian Universities

- COVID-19 Emergency Remote Teaching: Lessons Learned from Five EU Library and Information Science Departments

- Review Article

- Assessing Diversity in Academic Library Book Collections: Diversity Audit Principles and Methods

- Communications

- Twitter Interactions in the Era of the Virtual Academic Conference: A Comparison Between Years

- The Classification of Q1 SJR-Ranked Library and Information Science Journals by an AI-driven “Suspected Predatory” Journal Classifier

- Scopus-Based Study of Sustainability in the Syrian Higher Education Focusing on the Largest University

- Letter to the Editor

- Most Preprint Servers Allow the Publication of Opinion Papers

- SI Communicating Pandemics: COVID-19 in Mass Media

- COVID-19 in Mass Media: Manufacturing Mass Perceptions of the Virus among Older Adults

- Topical Issue: TI Information Behaviour and Information Ethics

- A Compass for What Matters: Applying Virtue Ethics to Information Behavior

- Studies on Information Users and Non-Users: An Alternative Proposal

- Ethical Issues of Human Information Behaviour and Human Information Interactions

- Ethics and Social Responsibility in Information Behavior, an Interdisciplinary Research in Uruguay