Abstract

Cancer remains one of the leading causes of global mortality, with dysregulated epigenetic regulators playing pivotal roles in tumorigenesis. Among these, Jumonji C domain-containing protein 5 (JMJD5/KDM8), an assigned protein hydroxylase/histone demethylase, exhibits context-dependent oncogenic or tumor-suppressive functions across malignancies. While JMJD5 is significantly overexpressed in breast, colon, oral squamous cell carcinoma, prostate cancer, and atypical meningiomas, its downregulation is observed in liver and lung cancers, highlighting its paradoxical roles in cancer biology. This review systematically examines JMJD5’s multifaceted mechanisms in tumor progression, including its regulation of apoptosis, modulation of glucose metabolism, promotion of metastatic dissemination, and acceleration of cell cycle progression. We further discuss the therapeutic implications of JMJD5 targeting, emphasizing its potential as a novel epigenetic vulnerability for precision oncology strategies.

Introduction

The global incidence and mortality rates of cancer are rising rapidly. Cancer is expected to become the main factor of death around the world in the 21st century and the biggest obstacle to improving lifespan [1]. Tumorigenesis involves not only oncogenic mutations driving aberrant expression of critical genes but also widespread epigenetic dysregulation. This complexity underscores the urgent need for novel therapeutic targets to advance precision oncology strategies.

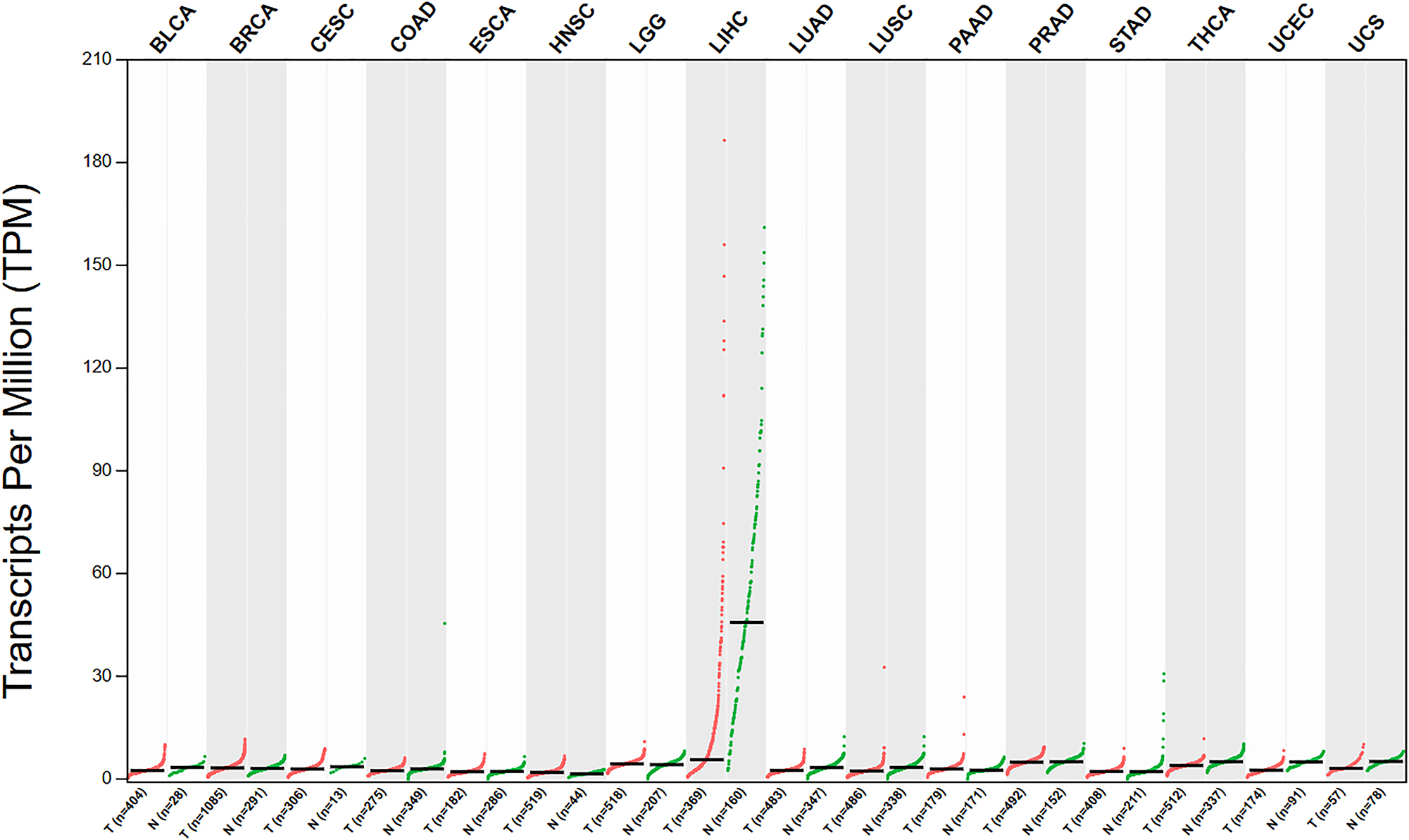

The Jumonji C domain-containing (JMJD) protein family, comprising 33 members in humans, plays pivotal roles in epigenetic regulation through histone modification [2]. In particular, JMJD5, also called KDM8, has proteolytic enzyme, and hydroxylase activities [2]. It plays a major role in various cancers, such as lung, liver, prostate, colon, and oral [3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9]. The expression of JMJD5 in different types of cancer is shown in Figure 1. Accordingly, here, we review the characteristics of JMJD5 in cancer and the specific mechanisms involved so as to explore new potential therapeutic targets for cancer treatment.

The expression of JMJD5 in different types of cancer (http://gepia.cancer-pku.cn/). (BLCA: Bladder Urothelial Carcinoma, BRCA: Breast invasive carcinoma, CESC: Cervical squamous cell carcinoma and endocervical adenocarcinoma, COAD: Colon adenocarcinoma, ESCA: Esophageal carcinoma, HNSC: Head and Neck squamous cell carcinoma, LGG: Brain Lower Grade Glioma, LIHC: Liver hepatocellular carcinoma, LUAD: Lung adenocarcinoma, LUSC: Lung squamous cell carcinoma, PAAD: Pancreatic adenocarcinoma, PRAD: Prostate adenocarcinoma, STAD: Stomach adenocarcinoma, THCA: Thyroid carcinoma, UCEC: Uterine Corpus Endometrial Carcinoma, UCS: Uterine Carcinosarcoma; T: tumor, N: normal).

Characteristics of JMJD5

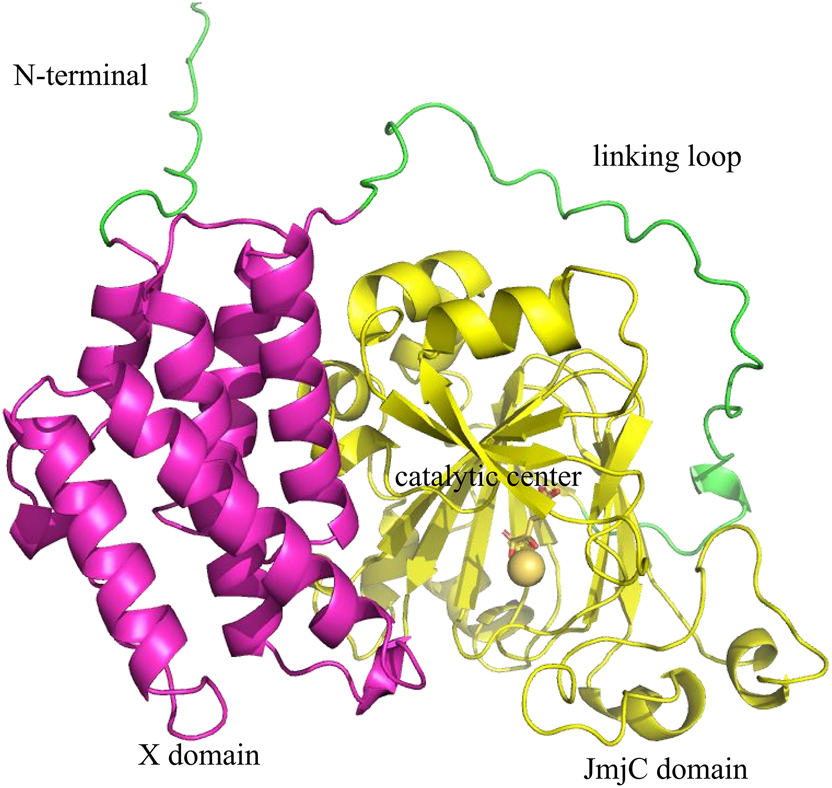

Most members of the JMJD family contain a DNA-binding domain, a Jumonji C (JmjC) domain, and a Jumonji N (JmjN) domain [10]. According to the GeneCards database, JMJD5 is localized to chromosome 16 (16p12.1). There are two subtypes of JMJD5 in the human body, subtype 1 and subtype 2, which contain 18,820 and 18,283 bases, respectively. The structure of the JMJD5 catalytic core comprises a JmjC domain, followed by an N-terminal extension comprising a mixture of helix and β-fold topology [10]. The protein structure of JMJD5 is shown in Figure 2.

The protein of JMJD5 is shown as a cartoon. 3D arrangement of JMJD5’s domain according to the protein structure obtained by AlphaFold (https://alphafold.com/) prediction. There are two structural domains, namely an N-terminal X domain and a C-terminal JmjC domain. These two domains are connected by a long loop sequence named the linking loop. The X domain flanks the protein surface of the JmjC domain and is composed of several helices.

In terms of enzymatic activity, JMJD5 demethylates histone H3 lysine 36 dimethylation (H3K36me2) [7]. JMJD5 uses Fe2+ and α-KG as cofactors for specific demethylations. Histone transferases and demethylases play important roles in regulating fundamental cellular activities, such as the cell cycle, growth, and apoptosis. Atypical histone modification is associated with the development of cancer, which can be considered to be a major target for new drugs [11], 12]. However, the JMJD5 H3K36me2 demethylation activity has been contested by several laboratories that were unable to reproduce it in vitro [2]. In addition, JMJD5 has dual endopeptidase and exopeptidase activities for arginine-methylated histone tails, including H2A, H3, and H4. Individual amino acids, including serine, arginine, alanine, threonine, proline, glycine, lysine, and glutamine residues, are removed from the tails of H3 and H4 [13]. H3, H4, and their arginine-methylated isoforms are significantly elevated with the knockout of JMJD5 in vivo [13]. Moreover, JMJD5 is a hydroxylase that catalyzes the stereoselective C-3 hydroxylation of arginine residues in protein sequences involved in chromatin stability (regulator of chromosome condensation domain-containing protein 1) and translation (ribosomal protein S6) [14]. The binding of JMJD5 to histone octamer indicates that the core histone octamer may be a potential substrate of JMJD5 as a protein hydroxylase [15].

Normal physiological roles of JMJD5

JMJD5 participates in a range of biological processes, including embryogenesis [16], 17], circadian rhythm [18], osteoclastogenesis [19], etc. The embryos of JMJD5 deficient mice exhibited severe growth retardation, resulting in the death of the embryos in the second trimester. The reason is that JMJD5 is involved in the transcriptional regulation of p53 regulatory gene subsets, and in JMJD5-deficient embryos, enhanced recruitment of p53 may lead to abnormal activation of the p53 signal, resulting in embryo death [17], 20]. Circadian rhythms are endogenous oscillations that adapt an organism’s behavior and physiology to regular changes in its environment. The study suggested JMJD5 and timing of CAB expression 1 (TOC1) work together to regulate the Circadian rhythms [21].

Jones et al. demonstrated a short-period circadian phenotype in JMJD5-mutated plants. They proved that JMJD5 may play an important role in both Arabidopsis and human circadian systems, despite the evolutionary distance between plants and mammals [18]. Researchers showed that down-regulated expression of JMJD5 leads to accelerated osteoclast formation and induces several osteoclast-specific genes such as Cathepsin K (CTSK) and dendritic cell-specific transmembrane protein (DC-STAMP), suggesting that JMJD5 is a negative regulator of osteoclast differentiation [19]. Research has demonstrated that JMJD5 functions as a critical disease-associated gene. Disease-causing variants such as the intronic mutation and C123Y substitution have been shown to disrupt JMJD5 mRNA splicing fidelity, destabilize its protein structure, and impair its hydroxylase enzymatic activity. These molecular alterations collectively contribute to a syndromic developmental disorder characterized by three cardinal manifestations: profound growth restriction, severe neurocognitive impairment, and distinctive craniofacial dysmorphism [22].

Overview of JMJD5’s dual roles in cancer progression

Many studies have shown that JMJD5 is a tumor promoter. For example, JMJD5 can promote the development of lung cancer cells [3]. Meanwhile, in liver cancer, JMJD5 uses its hydroxylase activity to promote hepatitis B virus replication, favoring the development of hepatocellular carcinoma [5]. In addition, the level of JMJD5 in breast cancer is closely related to clinical stage, histological grade, negative estrogen receptor status, and lymph node metastasis, all of which are poor prognostic factors [6]. JMJD5 also contributes to the proliferation and metabolism of breast cancer cells [23]. Interestingly, Glycine max consumption inhibits the development of breast cancer by downregulating the level of JMJD5 [24]. JMJD5 has also been reported to significantly increase the proliferation and migration of colon, prostate, and oral cancer cells [7], [8], [9]. In prostate cancer, there is an interaction between JMJD5 and the androgen receptor (AR), which promotes the expression of androgen-responsive genes even under conditions of androgen deprivation. These genes, including ANCCA/ATAD2 and EZH2, are regulated by JMJD5 and contribute to the survival of prostate cancer cells in the absence of hormones [8]. In atypical meningiomas, the recurrence rate decreases when the expression of JMJD5 is low [25].

The latest research shows that most leukemias are induced by the fusion of the mixed-lineage leukemia (MLL) gene with multiple genes. MLL fusion benefits the recruitment of TATA-binding protein and RNA polymerase II (Pol II), which augments the expression level of target genes. In eukaryotes, Pol II is controlled by nucleosomes at the transcriptional initiation site. JMJD5 replaces all arginine-methylated histone tails, producing “tailless nucleosomes” at the transcriptional starting point, which causes Pol II to enter a productive elongation process [26], 27] and thereby promote the development of leukemia. In addition, phosphorylation of the C-terminal domain of Pol II by Cyclin Dependent Kinase 9 (CDK9) can promote the binding of the N-terminal domain of JMJD5 to the C-terminal domain of Pol II [27].

However, studies have shown that JMJD5 inhibits cancer progression in lung and liver cancer. The expression of JMJD5 was first found to be downregulated in lung cancer cells [28]. Subsequent studies found that JMJD5 reduced the metastasis of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) [29]. Recent studies have shown that JMJD5 negatively impacts the stability of EGFR, and lower levels of JMJD5 are linked to accelerated progression of NSCLC. At a mechanistic level, JMJD5 collaborates with the E3 ligase HUWE1 to enhance the proteasomal degradation of both EGFR and its TKI-resistant variants, thus restraining the growth of NSCLC. These results imply that JMJD5 functions as a tumor suppressor in NSCLC by targeting EGFR for destabilization through JMJD5 [30]. Similarly, JMJD5 prevents the reproduction of hepatocellular carcinoma cells and inhibits the occurrence and development of hepatocellular carcinoma cells [4].

This evidence shows that JMJD5 plays a dual role in cancer and indicates the need for analysis of the function of JMJD5 in different situations. It is also clear that other roles require examination.

The mechanisms of JMJD5 in cancer

JMJD5 plays an essential role in cancer. Next, we present the current research on JMJD5 in cancer, highlighting its diverse functions and emphasizing its potential mechanisms in cancer.

JMJD5 and apoptosis

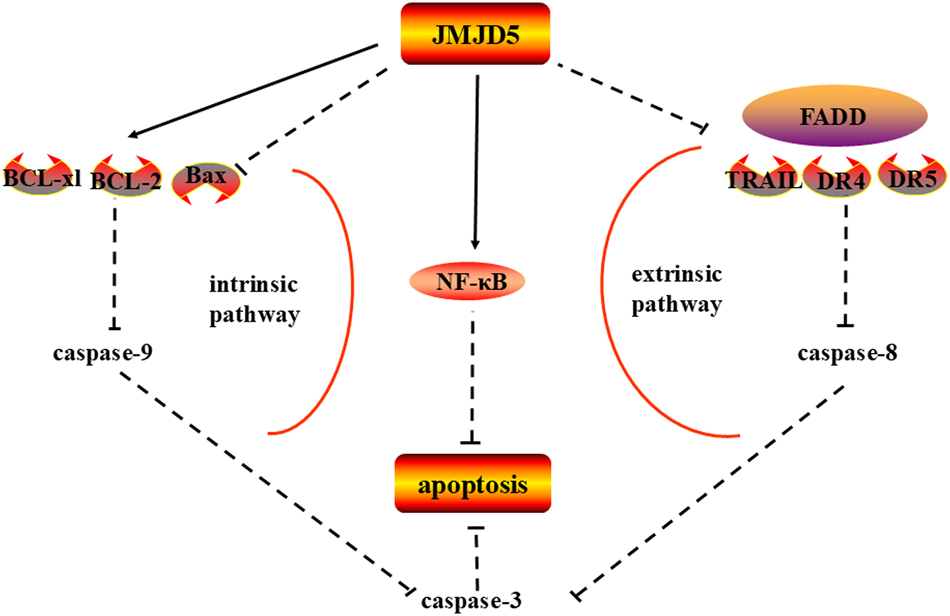

Apoptosis is a type of programmed cell death, which can eliminate damaged cells in an orderly and effective manner in the body. For the internal pathway, activation of Bcl-2-associated X protein (BAX) can activate caspase-9 and caspase-3, which can stimulate poly-ADP ribose polymerase (PARP) cleavage and prompt apoptosis [31]. For the external pathway, recruitment of fas-associated protein with death domain (FADD) and caspase-8 is activated when tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) binds to pro-apoptotic membrane receptors, including death receptor (DR)4 and DR5. Subsequently, caspase-3 is activated and apoptosis is activated [32].

In atypical meningiomas, patients with low expression of JMJD5 have a lower recurrence rate and longer survival time. JMJD5 is highly expressed in samples with low expression of caspase-3. The apoptosis-related factor is significantly related to the recurrence of atypical meningiomas. Therefore, JMJD5 may inhibit apoptosis by limiting the expression of caspase-3, which affects the recurrence of atypical meningiomas [25]. Similarly, in oral cancer, JMJD5 inhibits apoptosis through internal and external pathways [9]. The expression of cleaved caspase-8/-9/-3 and PARP increases in JMJD5 silenced cells. In addition, western blot analysis shows that JMJD5 siRNA reduces the expression of B-cell leukemia/lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2) and Bcl-xL while up-regulating the amount of Bax. RT-qPCR research shows that FADD, DR4, DR5, and TRAIL levels are significantly activated after the JMJD5 gene is knocked out. In addition, the caspase inhibitor can reverse the apoptosis induced by JMJD5 gene knockout and substantially improve cell viability at the same time [9]. Moreover, nuclear NF-κB is significantly augmented by overexpression of JMJD5 [9]. Activation of NF-κB is widely accepted to play a significant part in anti-apoptotic signaling. The NF-κB family increases the expression of Bcl-xL, which can prevent apoptosis [33], 34]. This process can be seen in Figure 3.

JMJD5 affects caspases in apoptosis. JMJD5 inhibited the expression of caspase-9/3 by intrinsic apoptotic pathway and caspase-8/3 by extrinsic apoptotic pathway, thus inhibiting apoptosis in cancer. Note: Bcl-2, B-cell leukemia/lymphoma 2; BAX, Bcl-2-associated X protein; FADD, fas-associated protein with death domain; DR4, death receptor 4; TRAIL, tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand. (inhibition (--|), activation (→))

The above evidence shows that JMJD5 exerts anti-apoptotic effects to drive oncogenesis. Apoptosis serves as a critical safeguard mechanism by eliminating potentially malignant cells during precancerous lesion formation; its dysregulation enables unchecked proliferation and confers therapeutic resistance in established tumors [35]. The aberrant suppression of apoptotic signaling by JMJD5 underscores its role as a molecular linchpin in cancer progression. Targeting JMJD5-mediated apoptotic evasion could therefore represent a promising strategy to restore programmed cell death, disrupt tumor survival pathways, and enhance chemosensitivity. Future translational studies focusing on JMJD5 inhibition may unlock novel therapeutic paradigms for precision cancer intervention.

JMJD5 and cell cycle progression

The cell cycle is a complex biological action involving a great deal of regulatory proteins, these proteins guide the cell through a certain sequence of proceedings, culminating in mitosis [36]. The cell cycle is frequently abnormally regulated in tumors and JMJD5 adjusts the cell cycle in cancer by regulating p53/p21, microtubules, and cyclin A.

JMJD5 affects the cell cycle by regulating p53 and p21

p53 is the most important tumor suppressor. It participates in a mixture of cellular responses, including apoptosis, cell growth, and metabolism [37], and can trigger DNA repair and cell cycle arrest [38]. Once cells are subjected to varying degrees of cellular damage, such as DNA damage and carcinogenic stress, p53 is rapidly activated by p53 phosphorylation. p53 is also mainly responsible for adjusting the expression of p21. The p21 gene contains two p53-binding genomic regions, which are respectively located upstream of the first exon and intron [39].

The p53 gene in embryos is significantly up-regulated when the expression of JMJD5 decreases. JMJD5 regulates the transcriptional activity of p53 by binding to the p53 DNA-binding domain. The quantity of p53 in cells increases when cancer cells are treated with adriamycin (a DNA-damaging substance) [3]. Moreover, JMJD5 prevents the recruitment of p53 to its target gene p21 in normal embryonic cells. Therefore, as shown in Figure 4, JMJD5 is considered to be a new p53 signal regulator that positively regulates the cell cycle and cell proliferation by inhibiting p53 [20]. Similarly, JMJD5 negatively regulates p53 in human oral cancer and lung cancer cells and thereby regulates the cell cycle and growth under normal and DNA-damaged conditions [3], 9]. Notably, the hepatitis B virus X protein (HBx) is critically implicated in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) pathogenesis by directly binding to and disrupting p53’s transcriptional activity, thereby promoting tumorigenesis [40]. Intriguingly, JMJD5 enhances HBx expression through epigenetic regulation [5], creating a feedforward loop that amplifies p53 suppression. This JMJD5-HBx-p53 regulatory axis may represent a targetable vulnerability in HCC, warranting further investigation into its therapeutic potential.

JMJD5 controls the cell cycle. JMJD5 regulates the acetyl-α-tubulin and detyrosinated-α-tubulin, MAP1B protein to regulate microtubule stabilization and promote cell cycle development. Furthermore, JMJD5 up-regulates the expression of cell cycle protein A1 and negatively regulates the expression of p53, which in turn stimulates the cell cycle. Note: MAPs, microtubule-associated proteins. (inhibition (--|), activation (→)).

In mouse embryonic fibroblasts, p21 gene knockout can partially avoid the cell growth inhibition and pluripotency deficiency caused by a decrease in JMJD5, indicating that a fall in JMJD5 levels leads to growth retardation and pluripotency deficiency through upregulation of p21 [41]. The results show that the interaction between these two molecules is crucial for maintaining the cell cycle and a pluripotent state. In addition, further studies have found that the decreased expression of JMJD5 might increase p21 by increasing genomic H3K36me2, rather than through the p53-p21 pathway [17]. Interestingly, another study reached the opposite conclusion: in hepatocellular carcinoma, JMJD5 directly binds to the promoter of p21 to activate p21, and this process is also independent of p53 [4]. This shows that, in different cases, the binding of JMJD5 to different sites of p21 will lead to differences in the regulation of p21, which should be studied in detail in subsequent research work.

The above evidence reveals a paradoxical regulatory role of JMJD5 in hepatocellular carcinoma: while it broadly suppresses p21 and p53 expression, it directly activates p21 in this specific context. This duality underscores the need for rigorous mechanistic studies to resolve whether JMJD5 functions as a transcriptional activator or repressor of p21, potentially governed by context-dependent mechanisms (e.g., cell type-specific signaling or tumor microenvironmental factors). Future investigations should prioritize systematic interrogation of JMJD5’s effects on p21/p53 networks across diverse cancer types, experimental models, and disease stages. Such efforts will clarify its context-specific regulatory logic and inform strategies to exploit JMJD5-p21/p53 axis modulation for targeted therapies.

JMJD5 affects the cell cycle by regulating microtubule stability

Microtubules are dynamic filamentous cytoskeleton proteins, which perform an essential role in cancer cell multiplication, signal transduction, and metastasis [42]. Defects in the assembly or properties of microtubules can lead to cancer and are associated with cancer cell proliferation, chemotherapy resistance, and poor patient prognosis [43]. Microtubules play a part in the correct execution of cell mitosis. Microtubules and their auxiliary proteins form the mitotic spindle during mitosis. It separates the chromosomes and can be said to be the most essential process in all eukaryotic cells [44]. During mitosis, the kinetochore must establish microtubule attachment and maintain those attachments while the microtubule grows and shrinks [45]. When the expression of microtubules is changed, the abnormality of the mitotic spindle and the subsequent abnormal cell cycle leads to cancer [46].

In cancer treatment, small changes in microtubule dynamics can also participate in the spindle checkpoint, which prevents cell cycle development during mitosis and ultimately leads to cancer cell apoptosis. Compounds that inhibit microtubule assembly such as vinca alkaloids and taxanes are critical chemotherapeutic agents for the therapy of cancer [47]. Abnormal mitotic spindles and prolonged mitosis develop when JMJD5 is knocked down. In addition, microtubules are more sensitive to nocodazole-induced depolymerization when the cells express lower levels of JMJD5, whereas the overexpression of JMJD5 enhances microtubule resistance to nocodazole. Cells with less expression of JMJD5 are more sensitive to the cytotoxicity of low concentrations of vincristine and colchicines, which are microtubule-targeting anti-cancer drugs [48]. These consequences indicate JMJD5 may play a crucial part in controlling mitosis by regulating the stability of spindle microtubules, with the following specific mechanisms.

First of all, in eukaryotes, the precise assembly of mitotic spindles guarantees correct chromosome separation during mitosis. Chromosome instability caused by mitotic abnormalities is one of the principal features of various cancers. JMJD5 may directly bind to the spindle microtubule [49], which increases the stability of the spindle and cytoskeletal microtubule [48], 49]. Secondly, acetylation and detyrosination of tubulin are indicators of microtubule stabilization. Cells with JMJD5 deletion show significant decreases in the levels of tubulin acetylation and detyrosination on the mitotic spindle. This result indicates that the portion of JMJD5 located in the cytoplasm promotes the acetylation and detyrosination of α-tubulin [48], 49] and thereby promotes microtubule stability. Finally, microtubule-associated proteins (MAPs) regulate the dynamics and stability of microtubules [50]. Studies have shown that overexpression of JMJD5 increases the stability of microtubules by increasing the level of MAP1B [48]. This phenomenon is illustrated in Figure 4.

Collectively, JMJD5 emerges as a promising biomarker for predicting the responsiveness of cancer cells to microtubule-targeting agents. Further studies are warranted to investigate whether pharmacological inhibition of JMJD5 can potentiate the clinical efficacy of microtubule-targeting therapies.

JMJD5 affects the cell cycle by regulating cyclin A protein

In breast cancer, the expression of cyclin A, one of the transition regulators of G1/S and G2/M, is up-regulated in response to JMJD5 overexpression [7]. JMJD5 is recruited to the H3K36me2 of the cyclin A coding region and demethylates it, resulting in increased transcriptional activity and cell cycle progression (Figure 4) [7]. Because JMJD5 can shuttle between the nucleus and cytoplasm under the conclusive situation [51], how does JMJD5 translocate into the nucleus and affect the expression of cyclin A?

Experimental studies have shown that a conventional signal-dependent nuclear protein – a nuclear localization signal (NLS) – is essential for the transfer of JMJD5 into the nucleus. Importin a/b and transportin-1 are proteins that carry cargo. We believe that importin a/b and transportin-1 also play an essential role in the nuclear translocation of JMJD5. Research has shown that interference with importin a/b and transportin-1 leads to a considerable decrease in the nuclear location of JMJD5 [51]. In this case, the study found that cyclin A was up-regulated when NLS was overexpressed. Still, no significant change was found in cyclin A without NLS, which indicated that NLS also affects the expression of cyclin A [51], 52].

Collectively, these findings establish JMJD5 and NLS as critical regulators of cyclin A activation, operating through mechanisms essential for cell cycle progression. This work not only delineates a functional nexus between JMJD5/NLS and cyclin A but also provides a mechanistic framework to investigate unexplored pathways through which JMJD5 may orchestrate cyclin A dynamics – including post-translational modifications, protein complex assembly, or cross-talk with checkpoint signaling. Future studies should leverage this foundation to dissect context-dependent regulatory networks and evaluate therapeutic strategies targeting JMJD5-driven cell cycle dysregulation.

JMJD5 and glucose metabolism

A prominent feature of tumor cells is metabolic changes, known as aerobic glycolysis or the Warburg effect [53]. This process includes increased glucose uptake and the conversion of intracellular glucose into pyruvate via glycolysis and subsequently into lactic acid. A fundamental substance in this process is pyruvate kinase M2 (PKM2), which dephosphorylates phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) into pyruvate [53]. Previous work [23] showed that the glucose uptake and lactic acid secretion of JMJD5 knockout cells were significantly decreased under normoxic or hypoxic conditions, which indicates that JMJD5 is involved in Warburg metabolism.

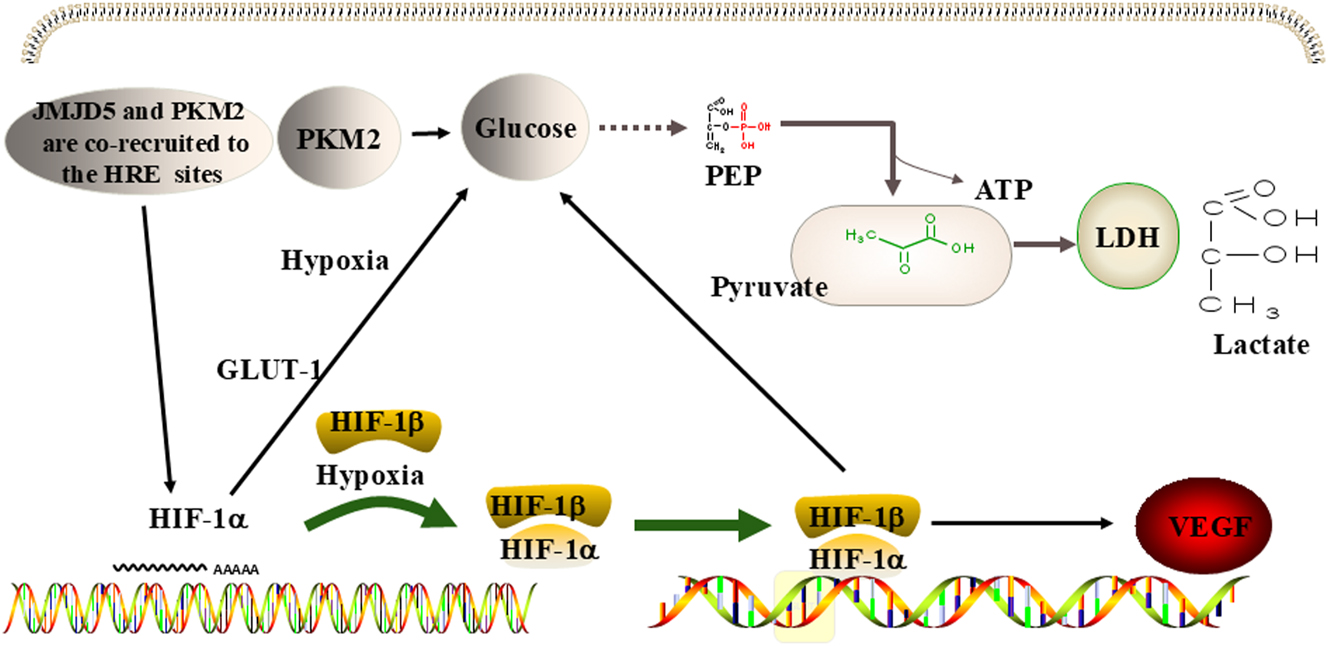

The specific mechanism is that JMJD5 binds to PKM2, which transfers PKM2 to the nucleus [8]. JMJD5 promotes the transformation of the cytoplasmic tetramer PKM2 into a dimer or heterodimer in the nucleus, which enables PKM2 to play an essential role in the Warburg effect. In addition, the JMJD5/PKM2 complex is co-recruited to hypoxia response elements as a co-activator of hypoxia inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) [8], 23]. HIF-1 is a heterodimer protein composed of two subunits, namely HIF-1α and HIF-1β. HIF-1 is the transporter of the glucose transporter-1 (GLUT-1). The upregulation of HIF-1 significantly promotes the transport of glucose to the cytoplasm [54]. In addition, HIF-1 can promote the expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and the activation of VEGF receptors, thereby favoring continuous angiogenesis, tumor progression, and metastasis [55]. This process is described in Figure 5.

JMJD5 regulates metabolism in cancer. JMJD5 promotes the Warburg effect by stimulating the activity of PKM2, and the combination of JMJD5 and PKM2 jointly encourages the activity of HIF-1α, further promoting the Warburg effect and causing the expression of VEGF. Note: PKM2, pyruvate kinase M2; HIF-1α, hypoxia inducible factor-1α; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor. LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; PEP, phosphoenolpyruvate; GLUT, glucose transporter.

In glioblastoma multimodal, Zinc finger CCHC type and RNA binding motif 1 (ZCRB1) and circRNA HEAT repeat containing 5B (circHEATR5B) overexpression inhibit aerobic glycolysis and proliferation in cells. Overexpression of ZCRB1 promotes the formation of circHEATR5B. In addition, circHEATR5B encodes a novel protein HEATR5B-881aa, which directly interacts with JMJD5 and reduces its stability by phosphorylating S361. Knockout of JMJD5 reduces PKM2 dimerization and inhibits glycolysis and proliferation of glioblastoma multimodal cells [56]. In addition, research indicates that low expression levels of JMJD5 are associated with elevated TP53-inducible glycolysis and apoptosis regulator (TIGAR) levels and poor prognosis in lung cancer patients [57]. JMJD5 emerges as a key regulator of tumor glucose metabolism by targeting the p53/TIGAR metabolic pathway. Studies have found that knocking down JMJD5 significantly enhances the expression of TIGAR in p53 wild-type NSCLC cells, which may further inhibit glycolysis and promote the pentose phosphate pathway [57]. In pancreatic cancer, JMJD5 deletion promotes the proliferation of pancreatic cancer cells and induces the transformation of cell metabolism from oxidative phosphorylation to glycolysis. JMJD5 negatively regulates the expression of c-Myc, the main regulator of cancer metabolism, leading to the reduction of c-Myc targeted gene expression. Research shows that the reduction of JMJD5 expression promotes cell proliferation and glycolysis of pancreatic cancer cells in a c-Myc dependent manner [58].

Collectively, these findings position JMJD5 as a central orchestrator of tumor metabolic reprogramming. Mechanistically, JMJD5 drives nuclear translocation and stabilization of PKM2, amplifying the Warburg effect – a hallmark of cancer metabolism characterized by aerobic glycolysis. Furthermore, JMJD5 forms a functional interplay with PKM2 to synergistically activate HIF-1α, thereby fueling metabolic adaptation, neovascularization, and tumor progression. Beyond this, JMJD5 becomes a key regulator of tumor glucose metabolism by targeting the p53/TIGAR metabolic pathway. Furthermore, the present study indicated that JMJD5 regulates glycolytic metabolism in pancreatic cancer cells in a c-Myc-dependent manner. These multilayered mechanisms underscore JMJD5’s potential as a therapeutic vulnerability for disrupting metabolic dependencies in malignancies.

JMJD5 and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition

Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) is the pivotal procedure in tumor metastasis. The EMT involves a dynamic reorganization of cellular architecture from epithelial to mesenchymal states, resulting in enhanced migratory and invasive capabilities [59]. One sign of EMT is the downregulation of E-cadherin [60]. Snail is a well-known transcriptional suppressor that can inhibit E-cadherin and induce EMT [61]. Snail is a target gene of JMJD5. JMJD5 can bind to the Snail promoter and activate its transcription. The expression of Snail is up-regulated when the expression of JMJD5 is elevated, which promotes tumor cell metastasis [6]. For example, JMJD5 is important in maintaining cell migration and invasion in breast cancer [6] and oral cancer [9]. JMJD5 can reduce the expression of E-cadherin in oral squamous cell carcinoma cells and trigger cancer cell metastasis.

Cancer cell metastasis is the main factor contributing to poor prognosis. The interruption of the metastatic pathway has preclinical and clinical prospects for cancer patients with metastatic disease. A variety of drugs have been shown to prevent metastasis and serve as targets for therapeutic development. It can be seen from the above that JMJD5 plays a crucial role in cancer metastasis. Adoption of JMJD5 as a target to control the metastasis of cancer cells will be of major significance to the treatment of tumors.

Drugs that reduce the effects of JMJD5

The disorder of JMJD5 plays an essential role in tumorigenesis. Silibinin is a commonly used anti-hepatotoxic drug, which has shown anti-cancer effects in many kinds of cancers [62]. In oral squamous cell carcinoma, JMJD5 is highly expressed and is significantly related to tumor size, cervical lymph node metastasis, and clinical stage [62]. Metastasis-associated protein 1 (MTA1) can regulate the expression of JMJD5 and is positively correlated with JMJD5. Silibinin suppressed oral cancer cell proliferation through downregulation of JMJD5 and MTA1 [62]. However, the signaling pathway through which silibinin represses JMJD5 and MTA1 in oral cancer cells is still unclear, and it can be explored in future studies. Allyl isothiocyanate is a natural dietary chemotherapy drug and epigenetic regulator and is a promising candidate drug for enhancing cancer treatment. In oral squamous cell carcinoma, the expression of JMJD5 and cyclin A1 is significantly increased, and Allyl isothiocyanate can downregulate the expression of JMJD5 and cyclin A1. Allyl isothiocyanate induces G2/M cell cycle arrest and apoptosis by regulating the G2/M related proteins JMJD5 and cyclin A1 in oral cancer cells, thereby inhibiting tumor growth [63].

Since JMJD5 regulates microtubule stability, the microtubules in JMJD5-deficient cells are more easily damaged by nocodazole-induced depolymerization, and overexpression of JMJD5 enhances the resilience of microtubules to nocodazole [48]. Studies have shown that cells lacking JMJD5 are more vulnerable to the cytotoxic effects of low concentrations of vinblastine or colchicine. When cells were treated with vinblastine or colchicine, the cell viability and the level of cleaved PARP in JMJD5-deficient cells were higher than that in control cells, and apoptotic cells were significantly increased. These results indicate that the absence of JMJD5 substantially increases the susceptibility of cancer cells to microtubule-destabilizing agents [48]. These results prove that JMJD5 may be a potential biomarker that can anticipate the sensitivity of cancer patients to microtubule-targeted drugs. Thus, the effect of nocodazole, vinblastine, or colchicine on cancer may be achieved by reducing JMJD5. We need further studies to determine whether the pharmacological inhibition of JMJD5 combined with microtubule targeting agents will enhance the chemotherapy response. Tumber et al. found that most broad-spectrum 2-oxoglutarate (2OG) oxygenase inhibitors can inhibit JMJD5, namely N-oxalylglycine, pyridine-2,4-dicarboxylic acid (2,4-PDCA), and ebselen. KDM4 subfamily specific inhibitor JMJD histone demethylase inhibitor III also effectively inhibits JMJD5. However, many clinically used 2OG oxygenase inhibitors (such as roxadustat) do not inhibit JMJD5 [64]. Brewitz et al. reported that 5-aminoalkyl-substituted 2,4-PDCA derivatives are effective JMJD5 inhibitors, exhibiting better selectivity for JMJD5 than other 2OG oxygenases [65].

Collectively, our findings demonstrate that silibinin suppresses the proliferation and metastatic potential of oral cancer cells through JMJD5 expression modulation. Furthermore, microtubule-targeting agents such as nocodazole, vinblastine, and colchicine exhibit anti-tumor effects via JMJD5 downregulation. These collective observations position JMJD5 as a tractable therapeutic target, underscoring the need for future investigations to prioritize the systematic identification and characterization of novel JMJD5 inhibitors. Such efforts will facilitate the translation of JMJD5-targeting strategies into clinical oncology practice.

Conclusions

Numerous studies have implicated JMJD5 as a driver of tumorigenesis in a variety of different cancers. JMJD5 plays an indispensable role in the occurrence and progression of cancer by affecting apoptosis, the cell cycle, glucose metabolism, and metastasis (Table 1). Indeed, because JMJD5 is an enzyme, small-molecule inhibitors could be developed to boost cancer therapy. Recent research has shown that silibinin suppressed oral cancer cell proliferation through downregulation of JMJD5 and MTA1, but the specific signaling pathway involved remains to be identified [62]. Allyl isothiocyanate induces G2/M cell cycle arrest and apoptosis by regulating the G2/M related proteins JMJD5 and cyclin A1 in oral cancer cells, thereby inhibiting tumor growth [63]. Thus, JMJD5 is a pharmaceutical target for the treatment of cancer. In addition, there are still a considerable number of unsolved mysteries concerning JMJD5, such as the functions of JMJD5 in gastric cancer and esophageal cancer and its other roles in the nucleus or cytoplasm. Further work is necessary to determine the roles of JMJD5 in tumors.

Different mechanisms of JMJD5 in cancer.

| The role of JMJD5 in cancer | Mediums | The way of adjustment | Types of cancer | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| JMJD5 promotes cancer metastasis and invasion | Snai1 | JMJD5 activates the expression of snail1 and reduces the expression of E-cadherin | (a) Breast cancer | [6], 9] |

| E-cadherin | (b) Oral cancer | |||

| JMJD5 regulates apoptosis | (a) BCL-2, BCL-xl, Bax | JMJD5 increases Bcl-2, Bcl-xl, NF-kB and decrease Bax, DR4, DR5 and TRAIL | (a) Atypical meningiomas | [9], 25] |

| (b) TRAIL, DR4, DR5, | (b) Oral cancer | |||

| JMJD5 regulates glucose metabolism | PKM2 | (a) JMJD5 transfers PKM2 into nucleus which promotes the Warburg effect | (a) Lung cancer | [8], 23], [56], [57], [58] |

| ZCRB1 | (b) ZCRB1 interacts with JMJD5 and reduces its stability | (b) Glioblastoma multimodal | ||

| TIGAR | (c) JMJD5 inhibits TIGAR in p53 wild-type NSCLC cells | (c) Pancreatic cancer | ||

| c-Myc | d) JMJD5 negatively regulates c-Myc expression | |||

| JMJD5 regulates cell cycle | (a) P53, P21 | (a) JMJD5 inhibits p53 and p21 | (a) Oral cancer | [3], 7], 9], 48], 49] |

| (b) Cyclin A1 | (b) JMJD5 up-regulates cyclin A1 by demethylation of H3K36me2 located in the cyclin A1 coding region | |||

| (c) α-tubulin | (c) JMJD5 promotes the acetylation and detyrosination of α-tubulin | (b) Lung cancer | ||

| (d) MAP1B | (d) JMJD5 increases the stability of microtubules by increasing the level of MAP1B |

-

BCL, B-cell lymphoma; Bax, Bcl-2-associated X protein; TRAIL, tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand; DR, death receptor 4; PKM, pyruvate kinase muscle; ZCRB1, zinc finger CCHC type and RNA binding motif 1; TIGAR, TP53-inducible glycolysis and apoptosis regulator; MAP1B, microtubule-associated protein 1B.

Collectively, the emerging role of JMJD5 in oncogenesis positions it as a promising therapeutic target for cancer intervention strategies. While preclinical evidence supports the translational potential of JMJD5 inhibition, rigorous preclinical and clinical validation remains imperative to establish its therapeutic efficacy and safety profile. Furthermore, systematic investigations are required to fully elucidate the physiological functions of JMJD5 and its oncogenic mechanisms across diverse cancer types. Such foundational research will accelerate the development of JMJD5-targeted therapies, which may ultimately integrate into mainstream clinical oncology paradigms in the foreseeable future.

Funding source: Wu Jieping Medical Foundation

Award Identifier / Grant number: 320.6750.2020-05-17

Funding source: The Zhangjiakou Science and Technology Bureau Foundation

Award Identifier / Grant number: 2421134D

Funding source: The Scientific Research Foundation of Harbin Medical University Cancer Hospital

Award Identifier / Grant number: JJZD2021-08 and JCQN2021-03

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the teachers of Yingjun Li, Ming Du and Zhongyu Liu for their kind help.

-

Research ethics: Not applicable.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Author contributions: Ling Qi and Jing-Wen Zhou wrote the manuscript. Ling Qi made figures and tables, and Yong-Chen Zhang, Xiao-Dong Ling, Ming-Xia Jiang, and Li-Sha Li modified the grammar. Yanjing Li proposed the idea of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state there is no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: This work was supported by Wu Jieping Medical Foundation (320.6750.2020-05-17) and the Scientific Research Foundation of Harbin Medical University Cancer Hospital (JJZD2021-08 and JCQN2021-03) and the Zhangjiakou Science and Technology Bureau Foundation (2421134D).

-

Data availability: Not applicable.

References

1. Bray, F, Laversanne, M, Sung, H, Ferlay, J, Siegel, RL, Soerjomataram, I, et al.. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: A Cancer J clinicians 2024;74:229–63. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21834.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

2. Oh, S, Shin, S, Janknecht, R. The small members of the JMJD protein family: enzymatic jewels or jinxes? Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer 2019;1871:406–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbcan.2019.04.002.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

3. Huang, X, Zhang, S, Qi, H, Wang, Z, Chen, HW, Shao, J, et al.. JMJD5 interacts with p53 and negatively regulates p53 function in control of cell cycle and proliferation. Biochim Biophys Acta 2015;1853:2286–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbamcr.2015.05.026.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

4. Wu, BH, Chen, H, Cai, CM, Fang, JZ, Wu, CC, Huang, LY, et al.. Epigenetic silencing of JMJD5 promotes the proliferation of hepatocellular carcinoma cells by down-regulating the transcription of CDKN1A 686. Oncotarget 2016;7:6847–63. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.6867.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

5. Kouwaki, T, Okamoto, T, Ito, A, Sugiyama, Y, Yamashita, K, Suzuki, T, et al.. Hepatocyte factor JMJD5 regulates hepatitis B virus replication through interaction with HBx. J Virol 2016;90:3530–42. https://doi.org/10.1128/jvi.02776-15.Search in Google Scholar

6. Zhao, Z, Sun, C, Li, F, Han, J, Li, X, Song, Z. Overexpression of histone demethylase JMJD5 promotes metastasis and indicates a poor prognosis in breast cancer. Int J Clin Exp Pathol 2015;8:10325–34.Search in Google Scholar

7. Hsia, DA, Tepper, CG, Pochampalli, MR, Hsia, EY, Izumiya, C, Huerta, SB, et al.. KDM8, a H3K36me2 histone demethylase that acts in the cyclin A1 coding region to regulate cancer cell proliferation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2010;107:9671–6. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1000401107.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

8. Wang, HJ, Pochampalli, M, Wang, LY, Zou, JX, Li, PS, Hsu, SC, et al.. KDM8/JMJD5 as a dual coactivator of AR and PKM2 integrates AR/EZH2 network and tumor metabolism in CRPC. Oncogene 2019;38:17–32. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41388-018-0414-x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

9. Yao, Y, Zhou, WY, He, RX. Down-regulation of JMJD5 suppresses metastasis and induces apoptosis in oral squamous cell carcinoma by regulating p53/NF-κB pathway. Biomed Pharmacother = Biomed Pharmacother 2019;109:1994–2004. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2018.07.144.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

10. Del, RPA, Krishnan, S, Trievel, RC. Crystal structure and functional analysis of JMJD5 indicate an alternate specificity and function. Mol Cell Biol 2012;32:4044–52. https://doi.org/10.1128/mcb.00513-12.Search in Google Scholar

11. Spannhoff, A, Hauser, AT, Heinke, R, Sippl, W, Jung, M. The emerging therapeutic potential of histone methyltransferase and demethylase inhibitors. ChemMedChem 2009;4:1568–82. https://doi.org/10.1002/cmdc.200900301.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

12. Wang, R, Xin, M, Li, Y, Zhang, P, Zhang, M. The functions of histone modification enzymes in cancer. Curr Protein Pept Sci 2016;17:438–45. https://doi.org/10.2174/1389203717666160122120521.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

13. Liu, H, Wang, C, Lee, S, Deng, Y, Wither, M, Oh, S, et al.. Clipping of arginine-methylated histone tails by JMJD5 and JMJD7. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2017;114:E7717–e26. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1706831114.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

14. Wilkins, SE, Islam, MS, Gannon, JM, Markolovic, S, Hopkinson, RJ, Ge, W, et al.. JMJD5 is a human arginyl C-3 hydroxylase. Nat Commun 2018;9:1180. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-03410-w.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

15. Wang, H, Zhou, X, Wu, M, Wang, C, Zhang, X, Tao, Y, et al.. Structure of the JmjC-domain-containing protein JMJD5. Acta Crystallogr Section D, Biol Crystallogr 2013;69:1911–20. https://doi.org/10.1107/s0907444913016600.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

16. Oh, S, Janknecht, R. Histone demethylase JMJD5 is essential for embryonic development. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2012;420:61–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.02.115.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

17. Ishimura, A, Minehata, K, Terashima, M, Kondoh, G, Hara, T, Suzuki, T. Jmjd5, an H3K36me2 histone demethylase, modulates embryonic cell proliferation through the regulation of Cdkn1a expression. Development 2012;139:749–59. https://doi.org/10.1242/dev.074138.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

18. Jones, MA, Covington, MF, DiTacchio, L, Vollmers, C, Panda, S, Harmer, SL. Jumonji domain protein JMJD5 functions in both the plant and human circadian systems. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2010;107:21623–8. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1014204108.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

19. Youn, MY, Yokoyama, A, Fujiyama-Nakamura, S, Ohtake, F, Minehata, K, Yasuda, H, et al.. JMJD5, a Jumonji C (JmjC) domain-containing protein, negatively regulates osteoclastogenesis by facilitating NFATc1 protein degradation. J Biol Chem 2012;287:12994–3004. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.m111.323105.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

20. Ishimura, A, Terashima, M, Tange, S, Suzuki, T. Jmjd5 functions as a regulator of p53 signaling during mouse embryogenesis. Cell Tissue Res 2016;363:723–33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00441-015-2276-7.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

21. Jones, MA, Harmer, S. JMJD5 Functions in concert with TOC1 in the arabidopsis circadian system. Plant Signaling Behav 2011;6:445–8. https://doi.org/10.4161/psb.6.3.14654.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

22. Fletcher, SC, Hall, C, Kennedy, TJ, Pajusalu, S, Wojcik, MH, Boora, U, et al.. Impaired protein hydroxylase activity causes replication stress and developmental abnormalities in humans. J Clin Invest 2023;133:e152784. https://doi.org/10.1172/jci152784.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

23. Wang, HJ, Hsieh, YJ, Cheng, WC, Lin, CP, Lin, YS, Yang, SF, et al.. JMJD5 regulates PKM2 nuclear translocation and reprograms HIF-1α-mediated glucose metabolism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2014;111:279–84. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1311249111.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

24. Wang, Y, Liu, L, Ji, F, Jiang, J, Yu, Y, Sheng, S, et al.. Soybean (Glycine max) prevents the progression of breast cancer cells by downregulating the level of histone demethylase JMJD5. J Cancer Res Therapeut 2018;14:S609–s15. https://doi.org/10.4103/0973-1482.187292.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

25. Lee, SH, Lee, EH, Lee, S-H, Lee, YM, Kim, HD, Kim, YZ. Epigenetic role of histone 3 lysine methyltransferase and demethylase in regulating apoptosis predicting the recurrence of atypical meningioma. J Kor Med Sci 2015;30:1157–66. https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2015.30.8.1157.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

26. Liu, H, Lee, S, Zhang, Q, Chen, Z, Zhang, G. The potential underlying mechanism of the leukemia caused by MLL-fusion and potential treatments. Mol Carcinogenesis 2020;59:839–51. https://doi.org/10.1002/mc.23204.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

27. Liu, H, Ramachandran, S, Fong, N, Phang, T, Lee, S, Parsa, P, et al.. JMJD5 couples with CDK9 to release the paused RNA polymerase II. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2020;117:19888–95. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2005745117.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

28. Wang, Z, Wang, C, Huang, X, Shen, Y, Shen, J, Ying, K. Differential proteome profiling of pleural effusions from lung cancer and benign inflammatory disease patients. Biochim Biophys Acta 2012;1824:692–700. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbapap.2012.01.016.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

29. Wu, J, He, Z, Yang, X-M, Li, K-L, Wang, D-L, Sun, F-L. RCCD1 depletion attenuates TGF-β-induced EMT and cell migration by stabilizing cytoskeletal microtubules in NSCLC cells. Cancer Lett 2017;400:18–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canlet.2017.04.021.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

30. Shen, J, Liu, G, Qi, H, Xiang, X, Shao, J. JMJD5 inhibits lung cancer progression by facilitating EGFR proteasomal degradation. Cell Death Dis 2023;14:657. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41419-023-06194-0.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

31. Fan, TJ, Han, LH, Cong, RS, Liang, J. Caspase family proteases and apoptosis. Acta Biochim Biophys Sinica 2005;37:719–27. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-7270.2005.00108.x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

32. Bell, BD, Leverrier, S, Weist, BM, Newton, RH, Arechiga, AF, Luhrs, KA, et al.. FADD and caspase-8 control the outcome of autophagic signaling in proliferating T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008;105:16677–82. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0808597105.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

33. Chen, C, Edelstein, LC, Gélinas, C. The Rel/NF-kappaB family directly activates expression of the apoptosis inhibitor Bcl-x(L). Mol Cell Biol 2000;20:2687–95. https://doi.org/10.1128/mcb.20.8.2687-2695.2000.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

34. Fan, C, Yang, J, Engelhardt, JF. Temporal pattern of NFkappaB activation influences apoptotic cell fate in a stimuli-dependent fashion. J Cell Sci 2002;115:4843–53. https://doi.org/10.1242/jcs.00151.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

35. Fulda, S. Tumor resistance to apoptosis. Int J Cancer 2009;124:511–5. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.24064.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

36. Song, CH, Lin, CW, Han, KH. Cell cycle-based antibody selection for suppressing cancer cell growth. FASEB J: Off Publ Fed Am Soc Exp Biol 2025;39:e70402. https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.202401586rrr.Search in Google Scholar

37. Vousden, KH, Prives, C. Blinded by the light: the growing complexity of p53. Cell 2009;137:413–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.037.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

38. Yu, Q Restoring p53-mediated apoptosis in cancer cells: new opportunities for cancer therapy. Drug Resist Updates : Rev Comment Antimicrob Anticancer Chemother 2006;9:19–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drup.2006.03.001.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

39. el-Deiry, WS, Tokino, T, Waldman, T, Oliner, JD, Velculescu, VE, Burrell, M, et al.. Topological control of p21WAF1/CIP1 expression in normal and neoplastic tissues. Cancer Res 1995;55:2910–9.Search in Google Scholar

40. Truant, R, Antunovic, J, Greenblatt, J, Prives, C, Cromlish, JA. Direct interaction of the hepatitis B virus HBx protein with p53 leads to inhibition by HBx of p53 response element-directed transactivation. J Virol 1995;69:1851–9. https://doi.org/10.1128/jvi.69.3.1851-1859.1995.Search in Google Scholar

41. Zhu, H, Hu, S, Baker, J. JMJD5 regulates cell cycle and pluripotency in human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells (Dayton, Ohio) 2014;32:2098–110. https://doi.org/10.1002/stem.1724.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

42. Čermák, V, Dostál, V, Jelínek, M, Libusová, L, Kovář, J, Rösel, D, et al.. Microtubule-targeting agents and their impact on cancer treatment. Eur J Cell Biol 2020;99:151075. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejcb.2020.151075.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

43. Shi, X, Sun, X. Regulation of paclitaxel activity by microtubule-associated proteins in cancer chemotherapy. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2017;80:909–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00280-017-3398-2.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

44. McIntosh, JR. Mitosis. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect Biol 2016;8:a023218. https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a023218.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

45. Monda, JK, Cheeseman, IM. The kinetochore-microtubule interface at a glance. J Cell Sci 2018;131:jcs214577. https://doi.org/10.1242/jcs.214577.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

46. Borys, F, Joachimiak, E, Krawczyk, H, Fabczak, H. Intrinsic and extrinsic factors affecting microtubule dynamics in normal and cancer cells. Molecules 2020;25:3705. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules25163705.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

47. Zhou, J, Giannakakou, P. Targeting microtubules for cancer chemotherapy. Curr Med Chem Anti Cancer Agents 2005;5:65–71. https://doi.org/10.2174/1568011053352569.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

48. Wu, J, He, Z, Wang, DL, Sun, FL. Depletion of JMJD5 sensitizes tumor cells to microtubule-destabilizing agents by altering microtubule stability. Cell Cycle (Georgetown, Tex) 2016;15:2980–91. https://doi.org/10.1080/15384101.2016.1234548.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

49. He, Z, Wu, J, Su, X, Zhang, Y, Pan, L, Wei, H, et al.. JMJD5 (Jumonji domain-containing 5) associates with spindle microtubules and is required for proper mitosis. J Biol Chem 2016;291:4684–97. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.m115.672642.Search in Google Scholar

50. Amos, LA, Schlieper, D. Microtubules and maps. Adv Protein Chem 2005;71:257–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0065-3233(04)71007-4.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

51. Huang, X, Zhang, L, Qi, H, Shao, J, Shen, J. Identification and functional implication of nuclear localization signals in the N-terminal domain of JMJD5. Biochimie 2013;95:2114–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biochi.2013.08.002.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

52. Macara, IG. Transport into and out of the nucleus. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev: MMBR 2001;65:570–94, table of contents. https://doi.org/10.1128/mmbr.65.4.570-594.2001.Search in Google Scholar

53. Cairns, RA, Harris, IS, Mak, TW. Regulation of cancer cell metabolism. Nat Rev Cancer 2011;11:85–95. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc2981.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

54. Hong, X, Zhong, L, Xie, Y, Zheng, K, Pang, J, Li, Y, et al.. Matrine reverses the Warburg effect and suppresses colon cancer cell growth via negatively regulating HIF-1alpha. Front Pharmacol 2019;10:1437. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2019.01437.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

55. Vaupel, P, Multhoff, G. Accomplices of the hypoxic tumor microenvironment compromising antitumor immunity: adenosine, lactate, acidosis, vascular endothelial growth factor, potassium ions, and phosphatidylserine. Front Immunol 2017;8:1887. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2017.01887.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

56. Song, J, Zheng, J, Liu, X, Dong, W, Yang, C, Wang, D, et al.. A novel protein encoded by ZCRB1-induced circHEATR5B suppresses aerobic glycolysis of GBM through phosphorylation of JMJD5. J Exp Clin Cancer Res : CR 2022;41:171. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13046-022-02374-6.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

57. Liu, G, Qi, H, Shen, J. JMJD5 inhibits lung cancer progression by regulating glucose metabolism through the p53/TIGAR pathway. Med Oncol (Northwood, Lond England) 2023;40:145. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12032-023-02016-7.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

58. Wang, H, Wang, J, Liu, J, Wang, Y, Xia, G, Huang, X. Jumonji-C domain-containing protein 5 suppresses proliferation and aerobic glycolysis in pancreatic cancer cells in a c-Myc-dependent manner. Cell Signal 2022;93:110282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cellsig.2022.110282.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

59. Yang, J, Antin, P, Berx, G, Blanpain, C, Brabletz, T, Bronner, M, et al.. Guidelines and definitions for research on epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2020;21:341–52. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41580-020-0237-9.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

60. Paredes, J, Figueiredo, J, Albergaria, A, Oliveira, P, Carvalho, J, Ribeiro, AS, et al.. Epithelial E- and P-cadherins: role and clinical significance in cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta 2012;1826:297–311. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbcan.2012.05.002.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

61. Peinado, H, Olmeda, D, Snail, CA Zeb and bHLH factors in tumour progression: an alliance against the epithelial phenotype? Nat Rev Cancer 2007;7:415–28.10.1038/nrc2131Search in Google Scholar PubMed

62. Yang, CY, Tsao, CH, Hsieh, CC, Lin, CK, Lin, CS, Li, YH, et al.. Downregulation of Jumonji-C domain-containing protein 5 inhibits proliferation by silibinin in the oral cancer PDTX model. PloS one 2020;15:e0236101. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0236101.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

63. Hsieh, CC, Yang, CY, Peng, B, Ho, SL, Tsao, CH, Lin, CK, et al.. Allyl isothiocyanate suppresses the proliferation in oral squamous cell carcinoma via mediating the KDM8/CCNA1 Axis. Biomedicines 2023;11:2669. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines11102669.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

64. Tumber, A, Salah, E, Brewitz, L, Corner, TP, Schofield, CJ. Kinetic and inhibition studies on human Jumonji-C (JmjC) domain-containing protein 5. RSC Chem Biol 2023;4:399–413. https://doi.org/10.1039/d2cb00249c.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

65. Brewitz, L, Nakashima, Y, Piasecka, SK, Salah, E, Fletcher, SC, Tumber, A, et al.. 5-Substituted pyridine-2,4-dicarboxylate derivatives have potential for selective inhibition of human Jumonji-C domain-containing protein 5. J Med Chem 2023;66:10849–65. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jmedchem.3c01114.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter on behalf of Tech Science Press (TSP)

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Review Articles

- Unveiling the hidden role of tumor-educated platelets in cancer: a promising marker for early diagnosis and treatment

- Multiple roles of mitochondria in tumorigenesis and treatment: from mechanistic insights to emerging therapeutic strategies

- The impact of JMJD5 on tumorigenesis: a literature review

- Research Articles

- A case-matched comparison of ER-α and ER-β expression between malignant and benign cystic pancreatic lesions

- Salivary gamma-glutamyltransferase activity as an indicator of redox homeostasis in breast cancer

- Cancer can be suppressed by alkalizing the tumor microenvironment: the effectiveness of “alkalization therapy” in cancer treatment

- Percutaneous-assisted laparoscopic bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy in BRCA-mutated patients: a retrospective comparative study

- ACAT2 contributes to cervical cancer tumorigenesis by regulating the expression of the downstream gene LATS1

- Rapid Communication

- Efficacy of mild hyperthermia in cancer therapy: balancing temperature and duration

- Case Report

- Orbital marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue with amyloidosis: a case series and review of the literature

- Commentary

- Palliative external beam radiotherapy for dysphagia management in advanced esophageal cancer: a narrative perspective

- Endometriosis and endometriosis-associated ovarian cancer, possible connection and early diagnosis by evaluation of plasma microRNAs

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Review Articles

- Unveiling the hidden role of tumor-educated platelets in cancer: a promising marker for early diagnosis and treatment

- Multiple roles of mitochondria in tumorigenesis and treatment: from mechanistic insights to emerging therapeutic strategies

- The impact of JMJD5 on tumorigenesis: a literature review

- Research Articles

- A case-matched comparison of ER-α and ER-β expression between malignant and benign cystic pancreatic lesions

- Salivary gamma-glutamyltransferase activity as an indicator of redox homeostasis in breast cancer

- Cancer can be suppressed by alkalizing the tumor microenvironment: the effectiveness of “alkalization therapy” in cancer treatment

- Percutaneous-assisted laparoscopic bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy in BRCA-mutated patients: a retrospective comparative study

- ACAT2 contributes to cervical cancer tumorigenesis by regulating the expression of the downstream gene LATS1

- Rapid Communication

- Efficacy of mild hyperthermia in cancer therapy: balancing temperature and duration

- Case Report

- Orbital marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue with amyloidosis: a case series and review of the literature

- Commentary

- Palliative external beam radiotherapy for dysphagia management in advanced esophageal cancer: a narrative perspective

- Endometriosis and endometriosis-associated ovarian cancer, possible connection and early diagnosis by evaluation of plasma microRNAs