Abstract

Purpose

This article examines intellectual and media imperialism as complementary dimensions of cultural imperialism. While previous studies have addressed these concepts separately, this study argues that the United States’ dominant role in the international academic sphere allows it to influence media professionals in other countries, reinforcing media imperialism through a local workforce.

Approach

This article employs a historical-interpretative approach for describing how intellectual imperialism and media imperialism work together. It also incorporates a quantitative analysis of the rise of the disinformation-fighting agenda.

Findings

This study highlights the intricate relationship between external intellectual influence and local media narratives. Based on concrete examples, it shows how the Knight Center influences Brazilian journalists through intellectual training and practical initiatives organized via Abraji.

Practical and social implications

This paper contributes to the broader discourse on cultural dominance and media influence. It emphasizes the need for critical reflection on the role of external forces in national media ecosystems.

Originality/value

The originality of this article lies in its exploration of the intersection between intellectual and media imperialism. It illustrates how external influences, such as the Knight Center, bypass local academic structures and align with US political interests, ultimately affecting national sovereignty and shaping media narratives.

1 Introduction

The term cultural imperialism has been used to describe different phenomena. Intellectual and media imperialism are the two most common meanings associated with it. The first one refers to initiatives aimed at exerting cultural influence on the elites of certain societies. The other involves the use of media to seduce and convince the general public of these societies. Most studies on media imperialism focus on how the export of media content serves this purpose (Nordenstreng 2013; Schiller 1969). Intellectual and media imperialism have been the subject of different research traditions. Otherwise, this article intends to explore how they work together, as complementary dimensions of cultural imperialism.

This article explores the role that the Knight Center for Journalism in the Americas, based at the University of Texas – Austin, and Abraji (Associação Brasileira de Jornalismo Investigativo, or Brazilian Investigative Journalism Association) exert as a mediator of cultural imperialism in Brazil. Since the 1960s, Latin America developed a proper tradition in communication studies, which has been critical of the US intellectual influence in the region. According to this view, creating national and regional academic infrastructure – universities, journals, and scientific organizations – was key to allowing them to exert intellectual sovereignty.

We argue that the Knight Center enhances the US influence on Latin American journalists, by training them in accordance with US values and methods. In Brazil, Abraji works as an intellectual and political proxy that promotes US perspectives and interests in Brazil. From an intellectual viewpoint, it works as a tool that allows the Knight Center to work as an educating actor in Brazil, bypassing the national academic infrastructure. By doing this, Abraji helps to provide intellectual legitimacy for items of the US political agenda.

This article adopts a historical interpretative approach about the relationship between the Knight Center and Abraji, and how it impacts on Brazil’s journalistic and political landscape. Documents published by the Knight Center and Abraji – their websites, news, and other informative pieces – provide the bulk of our empirical material. We interpret this material critically, in the light of the theory of cultural imperialism. Whereas the Knight Center and Abraji justify their actions based on the premise they offer journalistic and political assistance to Brazil, we contend that this concretely means a foreign interference in Brazilian internal affairs.

To discuss how this happens concretely, we examine two examples. The first one refers to how Abraji acted in support of the Lava Jato (Car Wash) operation, an anticorruption initiative that had a strong political bias against the Workers’ Party (Partido dos Trabalhadores, hereafter PT) and the former president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva. The article presents evidence that the US government exerted a strong influence on Lava Jato. The second example refers to the disinformation-fighting agenda. It explores how the United States used its central position in the international scholarship milieu to promote the idea that those countries and political forces opposing their interests are disinformation-spreaders. Moreover, the United States fostered the development of local infrastructures in other countries to protect its interests, disguising them as disinformation-fighting initiatives. Abraji has worked as one of the most important operators of this scheme in Brazil. We propose that Abraji is a key institutional piece organizing the intellectual comprador elite in the Brazilian media.

2 The Knight Center for the journalism in the Americas

The Knight Center for Journalism in the Americas is sited at the University of Texas at Austin. This university is one of the most important centers for Latin American studies. It also occupies a very central position in the world academic system in communication studies. Indeed, it has been ranked in the fourth position in the most recent Shanghai Ranking (2023). A recent study (Albuquerque et al. 2020) found that the University of Texas was one of the universities with more members on editorial boards in communication journals (92). This number was nearly double that of the editorial board members working in all Latin American and Caribbean universities (50). This endows the University of Texas with huge gatekeeping power in defining Latin America and its problems.

The Knight Center was founded in 2002 with grants provided by the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. The Knight Foundation specialized in sponsoring initiatives fostering journalism education and, starting in 2005, innovative approaches to journalism (Lewis 2012). The Knight Center has two core objectives. First, it works as a media assistance program, through distance learning programs directed at Latin American and Caribbean journalists and the organization of events to promote intellectual exchanges between academics and journalists. Second, it assists the creation of journalistic associations in Latin American and Caribbean countries.

Latin America has an established tradition in journalism education, which dates to the 1950s. Latin American communication scholars efforted to build an intellectual tradition independent from the US, to warrant their intellectual independence and national sovereignty (Enghel and Becerra 2018; Ganter and Ortega 2019). Thus, the Knight Center’s teaching initiative can be looked at as an active effort to surpass or circumvent the educational university infrastructure existing in Latin America and the Caribbean as the main source of formation for native journalists.

Despite the structural disadvantages they face, scholars working from Latin America have managed to get a growing presence in high-ranked journals in communication (Albuquerque et al. 2023) In theory, this would provide them with a better opportunity to influence the international debate on Latin America. But does it happen concretely? To answer this question, we have examined a very specific sample of articles, published by the Knight Center research team. We have focused on the researchers mentioned on the Knight Center’s website. It would be fair to expect that those researchers would be particularly interested in promoting an active dialogue with native Latin American researchers. After all, the Knight Center Research Group defines its main goal as being “to incentivize collaboration between scholars interested in contributing to the scholarship on journalism and media in Latin America and the Caribbean” (Knight Center n.d.).

We analyzed all the articles authored by the members of the Knight Center’s main research team focusing on Latin America. The sample comprises 41 articles and 2,408 citations, all of which were collected from the Web of Science database. The total number of sources (authors or institutions) cited in these articles was 961. We analyzed the profile of the authors who had five or more citations in the sample. This diminished the sample to 80 authors. We collected data referring to the country where the authors were born, made their graduate studies (when applicable), and work. We also tried to identify patterns of institutional concentration in the sample. What did we find?

Eighteen authors in our list were born in Latin America. This corresponds to 22 % of our sample. When we consider the country where they work, this figure decreases to eleven authors (or 17.5 %) of the sample. In comparison, forty authors work at US institutions. Latin American representation is even lower when we take PhD education as a parameter. Only six authors (7.5 %) graduated in Latin America, compared to 49 (61.5 %) in US institutions. This suggests that the Knight Center researchers are not particularly interested in engaging with how Latin Americans define themselves. The lack of attention to the native Latin American perspectives is particularly noteworthy when we consider that language does not provide a barrier for these researchers. Still, more importantly, Latin American scholars have a growing presence in the same quality journals where the Knight Center scholars publish.

Otherwise, 24 of the most cited authors in the list (30 % of the list) have connections with the University of Texas or the Knight Foundation: They work or have worked there (either as faculty members or visiting professors), or they have studied there (PhD or postdoctoral studies). These data suggest that collaboration, as conceived by Knight Center researchers, is a one-way road. While they downplay Latin American institutions in their references, they oversize the institution they work for. The Knight Center research team employs two resources to legitimize itself as a world center for Latin American journalism studies. It not only takes a natural advantage from the asymmetric international academic system, but it actively ignores native Latin American perspectives. By doing this, they move to bypass Latin America as a source of knowledge about itself.

2.1 Knight Center and Abraji

The Knight Center has also induced the creation of journalistic associations and vehicles in Latin America and Caribbean countries. Its website mentions associations created in Argentina (FOPEA), Brazil (Abraji), Colombia (CdR), Paraguay (FOPEP), and Peru (Rede Provincial de Periodistas de Peru). This article focuses on Abraji, an acronym for Associação Brasileira de Jornalismo Investigativo (Brazilian Investigative Journalism Association).

Abraji was founded in 2002. Earlier that year, investigative journalism became a hot topic in Brazil for a tragic reason. In June, a gang of drug dealers killed in a barbaric manner Tim Lopes, an investigative journalist working for O Globo newspaper. Abraji’s website describes its origin in terms consistent with a grassroots organization: “In December 2002, around 140 journalists gathered in the Freitas Nobre auditorium at the USP School of Communications and Arts, raised their hands, and decided to join forces in what has now become Abraji” (Abraji n.d.a).

This is not the entire story. In many ways, Abraji emulates the Knight Center’s agenda and methods on a local scale. It offers courses on variegated topics, such as data journalism, techniques to investigate corruption, and sustainable local journalism, among others. It also organizes research seminars on investigative journalism. As it happens to the Knight Center on a larger scale, these efforts aim to replace the Brazilian university system as the main source of knowledge authority on journalism.

Abraji also acts as a local organizer of initiatives pushing the Knight Center’s agenda. Since 2018, the publication of the scholars associated with the Knight Center Research Group began to focus on the topic of entrepreneurial journalism (Knight Center n.d.). Entrepreneurial journalism has risen recently, in response to the crisis experienced by the commercial media, due to platformization of journalism. Entrepreneurial outlets rely on alternative means for financing their business. One of the most important is funding provided by philanthropic foundations and, recently, platforms. These studies perceive an enormous potential for the development of new journalistic startups in Latin America. Some of these works depict the new entrepreneurial vehicles as being a model for the future of alternative (or independent) media. Accordingly, Abraji has engaged in initiatives aimed at fostering independent journalism projects in Brazil. One example is the course “Independent Journalism: How to develop sustainable journalistic projects” (Abraji n.d.b).

Even more important, Abraji works as a hub articulating a variety of Brazilian organizations in projects that, in most cases, are coordinated from abroad, especially from the United States. One of the main foreign partners of Abraji is the US government. Abraji has worked as the local partner of courses on topics such as investigative journalism, problems faced by female journalists, and disinformation-fighting, among others. The US Embassy sponsors Abraji’s International Seminar.

The following sections explore the Knight Center/Abraji connection as an initiative that merges characteristics of intellectual and media imperialism. We contend that it takes advantage of the academic asymmetries benefiting the Minority World (MiW) scholars and research institutions over their Majority World (MaW) equivalents.

3 Explaining the academic asymmetries: the de-westernizing and decolonizing approaches

Recently, many studies have highlighted the asymmetries existing in several international scholarships. They have found uneven national patterns regarding publication in prestige international journals (Demeter 2020) editorial boards membership (Albuquerque et al. 2020; Goyannes and Demeter 2020), and citations (Chakravartty et al. 2018). Scholars with a MaW background face more challenges than their MiW colleagues. For instance, English is considered the Lingua Franca for international scholarship (Suzina 2021), which provides a huge advantage for Anglophone scholars over others. Also, works referring to the MiW are supposed to have a more universal character than the others. The entire international scholarship system organizes upon a ranking system that defines the MaW institutions (universities, journals, and so on) as being superior to the others. These rules establish the basis for unbalanced patterns of relationships between MaW and MiW. Why does this happen?

Currently, there are three basic manners to answer this question. The “de-Westernizing” model is the most superficial of them. It concedes that international scholarship lacks diversity but does not elaborate neither on why and how this happens, nor what consequences follow. For the de-Westernizing approach, the lack of diversity is a serious problem, and the manner of solving it is taking concrete measures to introduce more diversity into the field (Waisbord 2022). This is the preferred approach of academic institutions such as scientific associations and journals. For instance, in its Statement on Inclusion, Diversity, Equity, and Access, the Executive Committee of the International Communication Association “recognizes that inequities have long existed, and continue to exist” (ICA 2019) and proposes a series of principles and measures aimed at changing this situation. It is worth noting that – except for one case – all the people who sign the document have MiW backgrounds and work in MiW institutions.

Differently from the de-Westernizing perspective, the decolonial approach identifies the perceived asymmetries in the international as a legacy of colonialism, that is, the exploitation of societies belonging to the MaW by MiW countries (Mignolo 2006; 2011]). Some consequences follow this argument. First, the fundamental causes of the current asymmetries are located mainly in the past, rather than in the present. The lesser presence of MaW countries in the international arena is supposed to be a consequence of a systematic process of economic exploitation and cultural erasure (epistemicide), which was put into practice in the past (Santos 2014). Second, this tradition associates colonial exploitation mainly with Western European countries. In most cases, colonialism conflates with Eurocentrism (Mignolo 2006). Third, the present time tends to be considered as the time that offers the opportunity to challenge the causes of scholarly asymmetries and set the basis for a fairer international academic system (Grosfoguel 2007).

Neither the de-Westernizing nor the decolonial approaches elaborate consistently on what consequences follow the strong international academic asymmetries. To face this problem, it is necessary to consider another perspective: the cultural imperialism approach.

4 Two dimensions of cultural imperialism

Roughly speaking, imperialism and colonialism refer to the same problem – the domination that some societies exert over others – considered from different angles. Studies on imperialism focus on the active side of the domination relationship (Kumar 2021): the characteristics of the perpetrators, their motives, methods, and the ideological means they use to justify the domination of other societies (Hayter 1971; Lutz 2006). Most often, studies on colonialism refer to the building of a Euro-centered world order, that is the domination exerted by Western European countries over societies all around the world. They also tend to study relations of domination that occurred in the past. Otherwise, studies on imperialism also explore relations of domination occurring in the present and, since the mid-20th century, have paid growing attention to the role of the United States as an agent of imperialism.

Cultural imperialism refers to the specific manners in which imperialistic domination occurs in the cultural realm. Studies on cultural imperialism have focused on two different classes of subjects: intellectual imperialism (Alatas 2000, 2003]; Bourdieu and Wacquant 1999) and media imperialism (Boyd-Barrett and Mirrlees 2019; Schiller 1969). These studies often consider one dimension or another; they rarely consider the two dimensions altogether.

4.1 Intellectual imperialism

Intellectual imperialism describes processes directed principally at intellectual elites. Syed Hussein Alatas (2000) provided some of the best syntheses on what intellectual imperialism is, how it works, and which consequences follow. He argues that intellectual imperialism works based on the same principles that its political and economic counterparts: 1) Exploitation: MaW people are supposed to deliver their knowledge to MiW scholars, as native informants 2) Tutelage: MiW is supposed to lecture MaW people on how they should behave; 3) Conformity: MaW people are expected to accept the rules established by the MiW; 4) Collaboration: MaW scholars and intellectuals are supposed to take part in the perpetuation of the MiW-led order, by performing secondary roles; 5) Intellectual rationalization of the imperialistic order; 6) Mediocrity: The people conducting the intellectual imperialistic subjugation of MaW countries are not among those with more status in their countries (Alatas 2000). One of the consequences of this process is creating a group of intellectual compradors, that is, MaW scholars who work as local collaborators of the MiW order.

In this article, imperialism refers to a scheme of intellectual domination that operates through a network of academic institutions, which includes universities, academic journals, funding agencies, and ranking organizations. The ranking organizations perform a vital role in this logic, as they hierarchize scholars, departments, universities, academic journals, and other relevant academic organizations according to scales of prestige. By doing this, they define what are the “prestige” universities and departments, and what journals are worth publishing and what are not (Marginson and Van der Wende 2007). By doing this, they concentrate symbolic power and academic authority in some places, at the expense of others. This logic stimulates MaW scholars who want to pursue an international career to search for education and work in MiW educational institutions, which may foster a brain drain in their native countries. Otherwise, they can perform subsidiary roles in research networks led by MiW scholars.

An important consequence of intellectual imperialism is enabling MiW scholars and policymaking institutions to classify the entire world according to a moral hierarchy. In almost every case, MiW countries occupy the highest positions in these rankings and, therefore, are taken as normative models for the other countries. Different authors have contended that the Freedom House ranking on freedom of the press is strongly biased towards the US and its allies (Giannone 2010; Sapiezynska and Lagos 2016). Additionally, scholars take for granted the classification of the political systems of countries as being consolidated democracies, transitional democracies, or authoritarian regimes. In most cases, the category “consolidated democracies” is reserved for MiW countries (Albuquerque 2023). It is worth noting that, recently, numerous scholars have raised serious concerns about the health of democracy in MiW countries (Levitsky and Ziblatt 2018; Mounk 2018). Still, comparative studies often ignore these concerns and still classify MiW democracies as being “consolidated.” A practical consequence of this hierarchic logic is endowing MiW scholars and universities with authority for intervening in other countries’ internal affairs under the excuse of providing them with “democracy assistance” (Christensen 2017). We contend that the Knight Center’s actions in Brazil provide an example in this regard.

It follows that, from an intellectual imperialism perspective, it is not sufficient to denounce the academic international order as being unfair. Also, they are not mere relics from a colonial past. In fact, this order is much more US than European-centered, and its origin is relatively recent. Its origins can be traced to the 1980–90s, in the context of a major restructuring of the global systems based on neoliberal principles, which was led by an alliance between the United States and International Financing Institutions, especially the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (Babb 2013). The strongly unbalanced nature of the academic international order does not happen by chance. It is part of a political project: concentrating the power of legitimate knowledge is in the hands of the United States and its MiW allies. Concretely, this enables the US (and secondarily other MiW) to educate other countries’ elites (and those working for international organizations) according to their worldviews and cultural values. By doing this, they can exert strong political influence on other countries.

4.2 Media imperialism

Media imperialism employs the dissemination of media content as a resource for conquering the hearts and minds of the larger public. The debate on media imperialism traces back to the years following World War 2. Then, the United States began to employ its mass media as a resource for exerting influence on other countries. Initially, the United States focused mainly on its Latin American neighbors. The promotion of the “American Way of Life” was part of a broader strategy aiming to present the United States as the champion of the agenda or modernization for other countries.

The United States justified these efforts based on two principles. The first was the principle of “free flow of information”, which was essentially an international extension of the free press ideology (Ampuja et al. 2019; Blanchard 1986; Boyd-Barrett and Mirrlees 2019). According to this principle, there would not be any barrier to the circulation of information in the world. The other was the ideology of modernization. During the Cold War Era, the United States sponsored the idea that modernization, understood as a technical set of principles and practices was the model that the MaW countries should follow to achieve social and economic development. The modernization ideology was the US’ answer to the Communist revolution model proposed by the Soviet Union. In this context, the American Way of Life appeared as a cultural paradigm for other societies, and the mass media offered an efficient tool for spreading it to other societies.

Critics denounced these US initiatives as imperialistic in nature. Drawing on the dependency theory, they argued that the real impact of the US modernization model was to foster the dependency of the MaW countries on the United States. They perceived the massive export of US cultural products as a threat to the cultural diversity of the world. Some authors contended that US media products served as stealth conveyors of US capitalistic ideology. Dorfman and Mattelart’s work on Walt Disney’s Donald Duck cartoons provides a particularly influential example in this regard (Dorfman and Mattelart 1971). Other authors highlighted the relationship between the US media and its industrial-military apparatus (Schiller 1969).

Initially debate on media imperialism was not confined to the academic milieu but was the subject of intense activism around the globe. This mobilization stimulated the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) to create the International Commission for the Study of Communication Problems, in 1977. Three years later, the Commission released a document entitled New World Information and Communication Order (NWICO) (Freije 2019). The United States and the United Kingdom reacted furiously to the document, arguing that it was an attack on the freedom of the press (Carlsson 2003). In the following decades, the scholarly debate on media imperialism lost much influence. Eventually, a new batch of concepts, such as asymmetric interdependence, soft power, and globalization came to substitute “media imperialism” as a model for describing the international academic order.

5 Beyond gatekeeping: the academic system as a political organizer

The structural asymmetries existing in the global scholarship allow MiW scholars and educational institutions to exert political influence and even act as political organizers in other countries. Bourdieu (1996) has described the prestige universities as key institutions in the formation of the state nobility in MiW countries, as they provide symbolical capital for the political elites. According to Bourdieu: “If the academic title is linked to the state, it is thus a privilege symbolically instituted by the state, that is, as ‘a right to the exclusive exercise of a certain function and the benefit of a certain income’” (Bourdieu 1996: 377). By graduating from such universities, state elites can justify their privileged positions as resulting from intellectual competence and individual merit. With the rise of the neoliberal globalization era, the prestige universities began to assume a new role, as they became core assets for the formation of the transnational elite in charge of conducting global governance (Fourcade 2006).

It follows that scholars and universities have played an important role in supporting imperialism. They did it in many ways. To begin with, they consistently described the colonized societies as being inferior to the colonizers (Said 1978), therefore justifying colonization as a civilizing project. Additionally, they systematically produced knowledge about the colonized societies to make it easier for the colonialists to dominate them. Anthropology was particularly important in this regard. Central universities also were instrumental in recruiting local elites and socializing them in the culture of the colonizers.

After the colonized societies acquired formal independence, the importance of the MiW universities in educating the elites of MaW countries became even greater. Many leaders of MaW countries enrolled in MiW universities to obtain legitimized knowledge and respectability. The United States (seconded by other MiW countries) took political advantage of this situation. US universities and scholars engaged in a series of educational initiatives – disguised as “foreign aid” – in association with “philanthropic” foundations and the US government State Department (Hayter 1971).

6 Destabilizing Brazilian democracy: the US influence on Lava Jato

Launched in 2014, the Lava Jato Operation had a huge impact on Brazilian politics. It originated as an anticorruption judicial operation aiming to tackle corruption, but soon changed its focus and promoted a narrative associating corruption with the Workers’ Party and former president Lula. Ultimately Lava Jato created a climate of generalized suspicion that led to the impeachment of President Dilma Rousseff in 2016. Additionally, in 2017, Judge Sergio Moro convicted Lula to a 9 years-term in prison. He was jailed in the following year. Then, he was the clear favorite for winning the 2018 presidential election.

Strong evidence suggests that the United States exerted a considerable influence on Lava Jato. Judge Moro’s ties with US state agencies such as the State Department, Department of Justice and FBI are well known. Added to this, it was later revealed the team of prosecutors ahead of Lava Jato coordinated its actions with the FBI (Estrada and Bourcier 2022). Yet, the US interference in Lava Jato goes far beyond that. A news piece based on an interview with Thomas A. Shannon Jr is particularly insightful in this regard. Working as the US ambassador in Brazil from 2009 to 2013 and as a counselor in the State Department from 2013 to 2016, he makes no secret that the US’ political interests had a huge influence in the process. The Brazilian project of fostering Latin American economic and political unity conflicted with the US interests in building a commercial integration in the Americas, “from Alaska to Patagonia”. Aiming to contain what Shannon Jr. called “a part of the project of power of PT and Latin America left” (Hall et al. 2020) the United States decided to attack the Brazilian construction firm Odebrecht, perceived as part of this project. To do this, the United States employed the legal framework of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, which allows the country to punish corruption acts abroad.

6.1 Building the intellectual basis for Lava Jato

The structural asymmetries in global scholarship proved to be an asset in this regard, as it allowed to training local elites attuned to the US interests. In Brazil, this process happened much before Lava Jato itself. In a telegram written in 2007, Clifford Sobel, then the US ambassador in Brazil manifested his interest in training local experts sympathetic to the United States and ready to learn its methods “without looking like pawns in a game” (Conjur 2021). The academic institutions provided the means for this.

US universities provided legal training on corruption-fighting for Brazilian lawyers, judges, and prosecutors. Since the early 2000s, the United States claimed for itself the role of leading corruption-fighting worldwide. At that time, corruption was a hot topic in the international scholarship. The World Bank was a key force pushing this agenda. It presented corruption as the “abuse of public offices for private gains” (World Bank 1997). Together with other agents, it proposed the building of a massive institutional infrastructure to contain corruption through the promotion of accountability. According to this view, accountability institutions such as the Judiciary, the Prosecutor’s Office, and the media are pillars of the quality of democracy. Otherwise, this view tends to perceive representative politics with a certain distrust, as institutions are prone to be captured by populist logic. This academic approach provided a very favorable scenario for Lava Jato, as it empowered the institutions taking part in the investigations to the detriment of the Executive power.

Most US scholars – and some Brazilians associated with them – focusing on Lava Jato were very supportive of it. They have portrayed it as the most important anticorruption operation in Latin America ever (Da Ros and Taylor 2022; Lagunes and Svejnar 2021). They did it not only as scholars, but also as public intellectuals. For instance, the political scientist Matthew M. Taylor defended Lava Jato in numerous interviews to journalistic vehicles and lamented when it became clear that it was losing momentum, during Bolsonaro’s presidential term. Notre Dame University awarded Moro with an honoris causa PhD for his performance ahead of Lava Jato. It is worth noting that other scholars – especially Brazilian ones – have been very critical of several aspects of Lava Jato. Yet, the US scholars dealing with the topic barely engage with their views.

Contrary to that suggested by its intellectual supporters, the concrete result of Lava Jato was degrading, not improving Brazilian democracy. It casted suspicion on the representative institutions and, by doing so, paved the way for the rise of the far-right in Brazil. A few days after Bolsonaro’s victory in the presidential elections, Moro accepted his invitation to be his minister of Justice. This was the first step leading to the decay of Lava Jato. Departing from 2019, new evidence emerged, suggesting that the prosecutors ahead of Lava Jato, Judge Moro, and the legacy media colluded to convict Lula, for political reasons (Albuquerque 2021). The Lava Jato ended in disgrace. The Brazilian Supreme Court ruled Moro suspicious for having accepted Bolsonaro’s invitation (and therefore benefiting himself from Lula’s prison). Still, recent international literature continues to praise Lava Jato (Da Ros and Taylor 2022; Lagunes and Svejnar 2021).

6.2 Lava Jato: the role of the legacy media and Abraji

The Brazilian legacy media provided massive coverage, largely favorable to Lava Jato (Albuquerque 2021; Damgaard 2018). For the owners and leading editors, Lava Jato provided the opportunity to knock out PT – their political adversary – from the presidency, after it won four elections in a row. Many rank-and-file journalists also engaged enthusiastically in Lava Jato, as they believed it was the right thing to do. Abraji had an important role in legitimizing the journalistic engagement in Lava Jato coverage as a model example of investigative journalism. It promoted numerous roundtables with journalists who took part in Lava Jato coverage of different events. In most cases, they presented their experiences in a very positive light. Still more important, Abraji acted as the main coordinator of the actions of journalists in several countries in Latin America.

Many members of Abraji directors board had a detached participation in Lava Jato coverage. Vladimir Netto – Abraji’s vice president in 2016 and 2017 – deserves a special mention for his close relationship with Sergio Moro. In 2016, Netto published a book on Lava Jato, depicting Moro in heroic terms. It is worth noting that Netto’s wife, Giselly Siqueira, worked as a communications advisor in several departments of the Judiciary and, for just over six months, worked as Moro’s press advisor at the Ministry of Justice (Revista Fórum 2018). All in all, Abraji worked actively as a local agent promoting US political and intellectual influence on Brazil in a very dramatic episode of its recent history.

7 Pushing the US fighting disinformation agenda

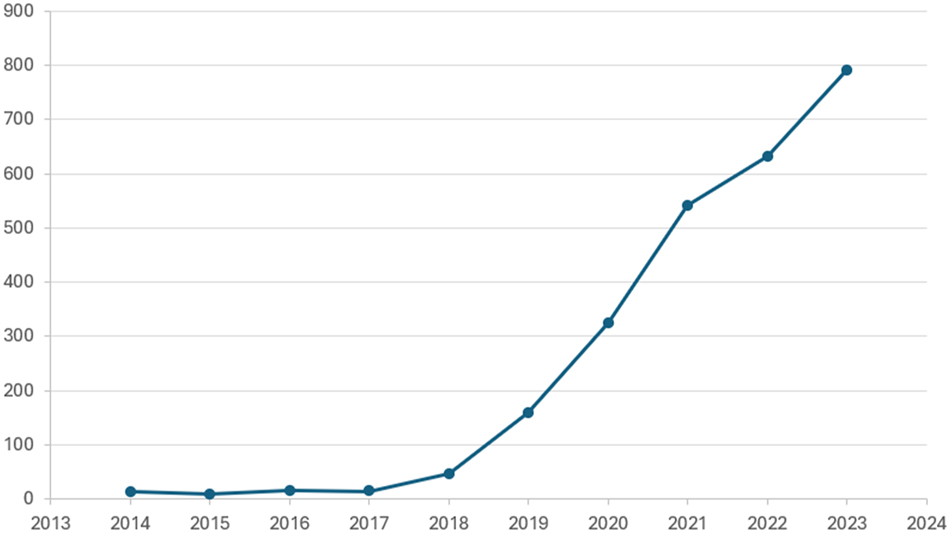

In a short interval of time, disinformation evolved to become a hot topic in both international scholarly and policy debates. Donald Trump’s triumph in the US presidential elections and the referendum that decided for the United King’s exit from the European Union were the main catalysts for this process. Figure 1 demonstrates how this approach took by storm the scholarly research:

Growth of publications on disinformation in the Web of Science (2014–2023).

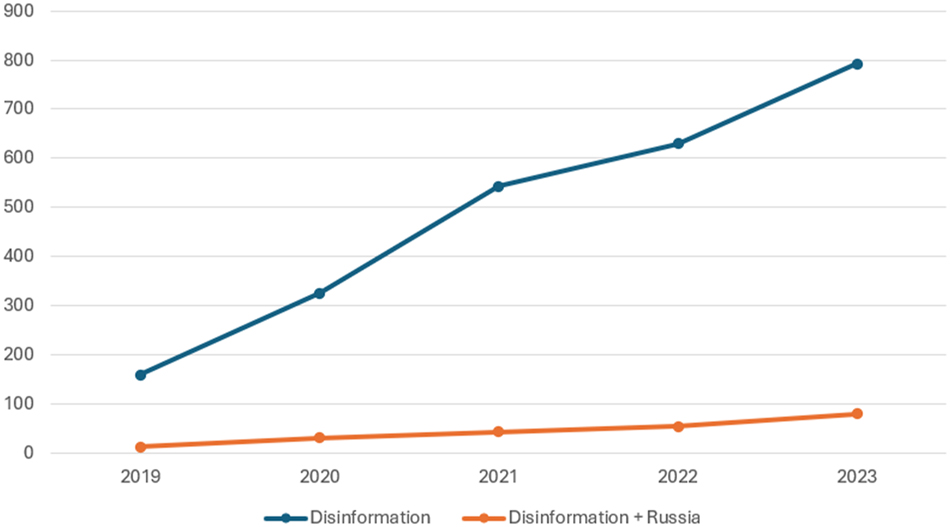

A so accelerated pace of growth does not seem consistent with an organic pattern of development of academic research. Non-academic actors have, in a great measure, set the terms for the public and scholarly debate on this topic. The think tank First Draft deserves special mention here. Its text “Information disorder” (Wardle and Derakhshan 2017) provided one of the main conceptual frameworks of the global debate on the topic. A policy paper addressed to the European Council, this text defines its purpose as, not simply to describe what disinformation is and how it works, but also to propose means to combat it. Wardle and Derakhshan draw mainly on US and UK examples but attribute them a universal character. More importantly, the paper presents a weaponized view of the problem, as its views closely align with those championed by key institutions of the US intelligence/military apparatus, such as the Atlantic Council and Rand Corporation. This is especially true regarding a Russophobic approach to the problem. Throughout the text, there are 62 references to “Russia” or “Russian”, associated with disinformation, trolls, and so on. In fact, as Figure 2 demonstrates, this weaponized approach has exerted a strong influence on the international literature about this topic.

Growth of publications on disinformation and mentioning Russia in the Web of Science (2019–2023).

Between 1980 and 2023, the Web of Science database recorded a total of 2.666 articles on disinformation. Over ninety percent of this production was published in the last five years, from 2019 to 2023. Still, more importantly, almost 10 percent of this sample associates disinformation to Russia.

To be sure, the influence of the US industrial-military apparatus in the agenda of communication research is not new. In its very origin, before World War 2, communication research is inseparable from the interests of the military, State Department, and intelligence agencies. During the Cold War era, the anti-Soviet agenda exerted a strong influence on the US communication research. This continues to happen. However, there is a core difference, as the US domestic views now can set the agenda of global research.

8 Promoting the US disinformation-fighting agenda in Brazil

The United States has systematically promoted its disinformation-fighting agenda worldwide since 2017. In March, the Atlantic Council – a think tank associated with the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) – published a policy paper entitled “Democratic Defense Against Disinformation”. Echoing the narrative that accused Russia of meddling in the US 2016 presidential election, this paper contended that North American and European countries should prepare themselves to face Russian practices of “hostile propaganda” (Polyakova and Fried 2019). The document endows the US government with the responsibility to lead these efforts, seconded by Europe and the G7 countries, civil society organizations (such as the Atlantic Council itself), and the private sector, especially the media and social media platforms.

The Atlantic Council has organized projects in other parts of the world. In 2018, it organized a series of initiatives aimed at influencing the Brazilian general elections that would take place that year. In June, the Brazilian think tank FGV’s Department for Public Policy Analysis announced it would join Atlantic Council in the #ElectionWatch project (FGV 2018). In September, the Atlantic Council promoted the seminar “Digital Resilience in the 2018 Elections” (MediaLab UFRJ 2018), together with the Rio de Janeiro Federal University’s Media Lab. Since the beginning, the Atlantic Council has attempted to connect itself to Brazilian research and educational institutions and a grassroots-like rhetoric, as they talk about “civil society resilience”. All in all, this episode provides an example of US meddling in Brazilian elections, with the pretext of avoiding others do so.

On June 28, this project assumed concrete forms through the Comprova Project. Abraji assumed a central role in the organization of this project. On its site, Abraji presents Comprova as a project idealized and developed by First Draft and the Harvard Kennedy School, counting with the support of the Google News Initiative and the Facebook Journalism Project. Comprova gathers dozens of journalistic vehicles and fact-checking agencies in a common effort to (allegedly) fight disinformation. Comprova initiated its activities by checking content related to the 2018 elections.

In 2019, Comprova released a report evaluating the impact of collaborative journalism in that period. The overall result of the evaluation is very positive. Yet, the concrete result of the 2018 elections was a massive rise of far-right politicians in Brazil, under the leadership of the new president Jair Bolsonaro. Massive disinformation spreading boosted the electoral campaigning of these politicians. During his government, Bolsonaro continued to employ disinformation as a key political resource (Soares 2021). This behavior proved particularly harmful during the Covid-19 pandemic, as Bolsonaro’s government continuously minimized the risk presented by the disease and undermined medical and scientific-based responses to it (Oliveira et al. 2021). The generalized feeling of anxiety provoked by this situation provided Comprova with an excellent opportunity to pose as a public service entity in contrast to an irresponsible government.

From the viewpoint of its foreign organizers, the most important objective behind initiatives such as Comprova is to exert a certain amount of control over the Brazilian media. Being a member of Comprova works as a stamp of trustworthiness for the vehicles that are part of this project. In 2022, Comprova had 42 vehicles (Projeto Comprova n.d.). Many of them are legacy media outlets, either with a national (for instance, O Estado de São Paulo, Folha de São Paulo, Veja) or a regional status (Correio do Povo, Diário do Nordeste, O Liberal, among others). The group counts on native digital media (such as Nexo Jornal and Poder 360) and national chapters of international media (CNN Brasil, AFP). Comprova includes foundation-funded Alma Preta, which makes news from an ethnic-racial perspective, and the far-right magazine Crusoé, which provided large support for Bolsonaro.

Even though Comprova gained prestige during (and in opposition to) Bolsonaro’s government, it seems to maintain an equal adversary stance against the Brazilian left-wing political forces and the media aligned with it. No outlet associated with the Brazilian progressive media group has been invited to make part of Comprova. This had concrete consequences for them. Not being part of this group led these media to be classified as “hyperpartisan” (as it happens to the far-right media), and this cost them prestige and resources (Albuquerque and Gonçalves 2024).

Abraji does not make secret of the Comprova’s ties with the US government. On many occasions, it thanks the US Embassy and Consulates for providing it with funding for its training programs. By building a “legitimate” journalistic field endowed with the mission of “fighting disinformation”, the United States attempts to exert control on the media landscape. One clear example refers to the effort to contain the Russian disinformation agenda. In February 2024, the Atlantic Council published a large report on Russia’s “global information war on Ukraine” (Atlantic Council 2024). This report counts with a chapter dedicated to Latin America, and Brazil receives a considerable share of attention on it. Brazil is one of the founding members of BRICS, which also includes Russia and China and seeks to challenge the US unipolar dominance over the world. The group was created in 2009, during Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva’s second term as Brazilian president. The report identifies Brasil 247 – described as being “aligned with left-wing parties, especially the Workers’ Party” – as the main spreader of the pro-Russian versions of the Ukrainian war in Brazil.

9 Discussion and conclusion

Cultural imperialism has two faces: intellectual and media imperialism. Most studies on cultural imperialism focus exclusively on one or the other aspect. Otherwise, this article proposes that to understand how cultural imperialism works nowadays, it must consider both simultaneously. In the last decades of the 20th century, the United States managed to acquire a dominant position in the emerging global scholarship, based on a US-dominated system of academic rankings. This privileged position allowed the United States to exert strong intellectual and political influence abroad. It also fostered new dynamics of media imperialism. The historical definition of media imperialism associates it with the export of media content from one country to another. This article explores a new dynamics of media imperialism, in which imperialist countries educate the media elites of other countries according to their values, interests, and methods.

This article analyzed a concrete example of how this media imperialism logic works. It refers to how the Knight Center for Journalism in the Americas efforts to influence Brazilian journalists. In sum, the Knight Center does this in two different manners. First, it provides intellectual training to Brazilian journalists and journalism students. Given that Latin America has a solid university infrastructure in journalism education, the Knight Center’s initiative means effectively an attempt to bypass this infrastructure as the main referential for Latin American journalists’ education. To do this, researchers affiliated with the Knight Center actively minimize the importance of the research carried out by researchers working and Latin America and overvalue the importance of their own intellectual contribution. The analysis of the citation patterns in a selected group of works published by the Knight Center’s researchers team provides solid evidence that this really happens.

Second, the Knight Center works as an organizer of practical initiatives mobilizing Brazilian journalists, through its proxy association Abraji. Many of these initiatives are attuned to the interests of the US government or its agencies and are backed by foreign state and non-state actors. This article explored two cases in a more detailed manner. One refers to the Lava Jato operation, which had a huge political impact on Brazilian politics. We present and discuss evidence of the US government’s interference in Lava Jato and the auxiliary role that Abraji performed in this regard. The other refers to the promotion of a disinformation-fighting agenda in Brazil, perceived in the light of the US interests. Again, Abraji performed a strategic role, by articulating a variegated set of agents in a local version of an effort led by agents associated with the US intelligence-military apparatus. By doing so, Abraji plays a strategic role in providing education and networking allowing to building an intellectual comprador elite in the Brazilian journalistic community.

Funding source: Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento CientÃ-fico e Tecnológico

Award Identifier / Grant number: 406504/2022-9

Award Identifier / Grant number: E-26/200.531/2023

-

Research funding: This work was funded by Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (Award no. 406504/2022-9) and Fundação Carlos Chagas Filho de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (Award no. E-26/200.531/2023).

References

Abraji (Associação Brasileira de Jornalismo Investigativo). n.d.a. Sobre a Abraji. Available at: https://www.abraji.org.br/institucional/#sobre-a-abraji.Search in Google Scholar

Abraji (Associação Brasileira de Jornalismo Investigativo). n.d.b. Cursos. Available at: https://cursos.abraji.org.br/course/index.php?categoryid=19.Search in Google Scholar

Alatas, Syed Farid. 2000. Intellectual imperialism: Definition, traits, and problems. Southeast Asian Journal of Social Science 28(1). 23–45. https://doi.org/10.1163/030382400x00154.Search in Google Scholar

Alatas, Syed Farid. 2003. Academic dependency and the global division of labour in the social sciences. Current Sociology 51(6). 599–613. https://doi.org/10.1177/00113921030516003.Search in Google Scholar

Albuquerque, Afonso. 2021. The two sources of the illiberal turn in Brazil. The Brown Journal of World Affairs 27(2). 179–193.Search in Google Scholar

Albuquerque, Afonso. 2023. Transitions to nowhere: Western teleology and regime-type classification. International Communication Gazette 85(6). 479–497. https://doi.org/10.1177/17480485221130220.Search in Google Scholar

Albuquerque, Afonso & Reynaldo A. Gonçalves. 2024. Journalism, crisis, and resistance: Journalistic role performance in the Brazilian progressive media. Journalism Practice. 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2024.2399566.Search in Google Scholar

Albuquerque, Afonso, Thaiane Moreira de Oliveira, Marcelo Alves dos Santos Junior & Sofia Oliveira Firmo de Albuquerque. 2020. Structural limits to the de-westernization of the communication field: The editorial board in Clarivate’s JCR system. Communication, Culture and Critique 13(2). 185–203. https://doi.org/10.1093/ccc/tcaa015.Search in Google Scholar

Albuquerque, Afonso, Thaiane Oliveira, Francisco Paulo Jamil Marques, Everton Miola, Ivan Mitozo, Carolina Quesada Tavares & Mariana Araujo. 2023. A Internacionalização da Pesquisa Brasileira em Comunicação: Desafios e Estratégias. RAE-IC. Revista de la Asociación Española de Investigación de la Comunicación 10(20). raeic102005. https://doi.org/10.24137/raeic.10.20.5.Search in Google Scholar

Ampuja, Marko, Juha Koivisto & Kaarle Nordenstreng. 2019. Historicizing and theorizing media and cultural imperialism. In Oliver Boyd-Barrett & Tanner Mirrlees (eds.), Media imperialism: Continuity and change, 31–44. London: Rowman & Littlefield.Search in Google Scholar

Atlantic Council. 2024. Undermining Ukraine: How Russia widened its global information war in 2023. Available at: https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/in-depth-research-reports/report/undermining-ukraine-how-russia-widened-its-global-information-war-in-2023/.Search in Google Scholar

Babb, Sarah. 2013. The Washington consensus as transnational policy paradigm: Its origins, trajectory and likely successor. Review of International Political Economy 20(2). 268–297. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2011.640435.Search in Google Scholar

Blanchard, Margaret A. 1986. Exporting the first amendment: The press-government Crusade of 1945-1952. Research on teaching monograph series. New York: Longman Publishing Group.Search in Google Scholar

Bourdieu, Pierre. 1996. The state nobility: Elite schools in the field of power. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.10.1515/9781503615427Search in Google Scholar

Bourdieu, Pierre & Loic Wacquant. 1999. On the cunning of the imperialist reason. Theory, Culture & Society 16(1). 41–58. https://doi.org/10.1177/026327699016001003.Search in Google Scholar

Boyd-Barrett, Oliver & Tanner Mirrlees. 2019. Media imperialism: Continuity and change. London: Rowman & Littlefield.Search in Google Scholar

Carlsson, Ulla. 2003. The rise and fall of NWICO: From a vision of international regulation to a reality of multilevel governance. Nordicom Review 24(2). 31–67. https://doi.org/10.1515/nor-2017-0306.Search in Google Scholar

Chakravartty, Paula, Rachel Kuo, Victoria Grubbs & Charlton McIlwain. 2018. #CommunicationSoWhite. Journal of Communication 68(2). 254–266. https://doi.org/10.1093/joc/jqy003.Search in Google Scholar

Christensen, Michael. 2017. Interpreting the organizational practices of North American democracy assistance. International Political Sociology 11(2). 148–165. https://doi.org/10.1093/ips/olx013.Search in Google Scholar

Conjur. 2021. Jornal francês mostra como EUA usaram Moro e Lava Jato. Available at: https://www.conjur.com.br/2021-abr-10/jornal-frances-mostra-eua-usaram-moro-lava-jato/.Search in Google Scholar

Damgaard, Mads Bjelke. 2018. Media leaks and corruption in Brazil: The infostorm of impeachment and the Lava-Jato Scandal. New York: Routledge.10.4324/9781351049306Search in Google Scholar

Da Ros, Luciano & Matthew M. Taylor. 2022. Brazilian politics on trial: Corruption and reform under democracy. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers.10.1515/9781955055192Search in Google Scholar

Demeter, Marton. 2020. Academic knowledge production and the global south. London: Palgrave-Macmillan.10.1007/978-3-030-52701-3Search in Google Scholar

Dorfman, Ariel & Armand Mattelart. 1971. Para leer al Pato Donald: Comunicación de masa y colonialismo. Buenos Aires: Siglo Veinteuno.Search in Google Scholar

Enghel, Florencia & Martín Becerra. 2018. Here and there: (Re)situating Latin America in international communication theory. Communication Theory 28. 111–130. https://doi.org/10.1093/ct/qty005.Search in Google Scholar

Estrada, Gaspard & Nicolas Bourcier. 2022. Lava Jato: The Brazilian Trap. Le Monde. Available at: https://www.lemonde.fr/en/archives/article/2022/03/11/lava-jato-the-brazilian-trap_5978421_113.html.Search in Google Scholar

FGV. 2018. International partnership will tackle disinformation in the 2018 elections. Available at: https://portal.fgv.br/en/news/international-partnership-will-tackle-disinformation-2018-elections.Search in Google Scholar

First Draft. n.d. About. Available at: https://firstdraftnews.org/about/.Search in Google Scholar

Fourcade, Marion. 2006. The construction of a global profession: The transnationalization of economics. American Journal of Sociology 112(1). 145–194. https://doi.org/10.1086/502693.Search in Google Scholar

Freije, Vanessa. 2019. The ‘emancipation of media’: Latin American advocacy for a new international information order in the 1970s. Journal of Global History 14(2). 301–320. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1740022819000058.Search in Google Scholar

Ganter, Sarah A. & Francisco Ortega. 2019. The invisibility of Latin American scholarship in European media and communication studies: Challenges and opportunities of de-westernization and academic cosmopolitanism. International Journal of Communication 13. 68–91.Search in Google Scholar

Giannone, Diego. 2010. Political and ideological aspects in the measurement of democracy: The freedom House case. Democratization 17(1). 68–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510340903453716.Search in Google Scholar

Goyannes, Manuel & Manuel Demeter. 2020. How the geographic diversity of editorial boards affects what is published in JCR-ranked communication journals. Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly 57(4). 1123–1148. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077699020904169.Search in Google Scholar

Grosfoguel, Ramón. 2007. The epistemic decolonial turn: Beyond political-economy paradigms. Cultural Studies 21(2–3). 211–223. https://doi.org/10.1080/09502380601162514.Search in Google Scholar

Hall, Kevin, Guilherme Amado & Thiago Herdy. 2020. Ex-embaixador mostra visão dos EUA sobre Lava Jato e projeto de poder do PT. Poder360. Available at: https://www.poder360.com.br/lava-jato/ex-embaixador-mostra-visao-dos-eua-sobre-lava-jato-e-projeto-de-poder-do-pt/.Search in Google Scholar

Hayter, Teresa. 1971. Aid as imperialism. Middlesex, UK: Penguin Books.Search in Google Scholar

ICA (International Communication Association). 2019. On inclusion, diversity, equity, and access: Statement from the executive committee of the international communication association. Available at: https://www.icahdq.org/blogpost/1523657/327317/On-Inclusion-Diversity-Equity-and-Access-Statement-from-the-Executive-Committee-of-the-International-Communication-Association-ICA.Search in Google Scholar

Knight Center. n.d. Research Group. Available at: https://knightcenter.utexas.edu/research-group/#journal.Search in Google Scholar

Kumar, Krishan. 2021. Colony and empire, colonialism and imperialism: A meaningful distinction? Comparative Studies in History and Society 63(2). 280–309. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0010417521000050.Search in Google Scholar

Lagunes, Paul & Jan Svejnar (eds.). 2021. Corruption and the Lava Jato Scandal in Latin America. New York: Routledge.10.4324/9781003024286Search in Google Scholar

Levitsky, Steven & Daniel Ziblatt. 2018. How democracies die. New York: Crown.Search in Google Scholar

Lewis, Seth C. 2012. From journalism to information: The transformation of the Knight Foundation and news innovation. Mass Communication and Society 15(3). 309–334. https://doi.org/10.1080/15205436.2011.611607.Search in Google Scholar

Lutz, Catherine. 2006. Empire is in the details. American Ethnologist 33(4). 593–611. https://doi.org/10.1525/ae.2006.33.4.593.Search in Google Scholar

Marginson, Simon & Marijk Van der Wende. 2007. To rank or to be ranked: The impact of global rankings in higher education. Journal of Studies in International Education 11(3/4). 306–329. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315307303544.Search in Google Scholar

MediaLab UFRJ. 2018. Seminário Internacional Resiliência Digital nas Eleições 2018. Available at: https://medialabufrj.net/eventos/2018/10/seminario-internacional-resiliencia-digital-nas-eleicoes-2018/.Search in Google Scholar

Mignolo, Walter D. 2006. The idea of Latin America. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing.Search in Google Scholar

Mignolo, Walter D. 2011. The darker side of western modernity: Global futures, decolonial options. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.10.1215/9780822394501Search in Google Scholar

Mounk, Yascha. 2018. The people vs. democracy: Why our freedom is in danger and how to save it. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.10.4159/9780674984776Search in Google Scholar

Nordenstreng, Kaarle. 2013. How the new world order and imperialism challenge media studies. tripleC: Communication, Capitalism & Critique 11(2). 348–358. https://doi.org/10.31269/triplec.v11i2.495.Search in Google Scholar

Oliveira, Thaiane, Simone Evangelista, Marcelo Alves & Rodrigo Quinan. 2021. ‘Those on the right take chloroquine’: The illiberal instrumentalisation of scientific debates during the COVID-19 pandemic in Brazil. Journal of Political Ideologies 26(2). 165–184. https://doi.org/10.1080/13569317.2021.1949826.Search in Google Scholar

Polyakova, Alina & Daniel Fried. 2019. Democratic defense against disinformation 2.0. Atlantic Council. https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/in-depth-research-reports/report/democratic-defense-against-disinformation-2-0/.Search in Google Scholar

Projeto Comprova. n.d. Partners. Available at: https://projetocomprova.com.br/about/partners/.Search in Google Scholar

Revista Fórum. 2018. Comunicação de Moro Será Chefiada por Esposa de Autor de Livro da Lava Jato, Filho de Miriam Leitão. Available at: https://revistaforum.com.br/midia/2018/12/18/comunicao-de-moro-sera-chefiada-por-esposa-de-autor-de-livro-da-lava-jato-filho-de-miriam-leito-37159.html.Search in Google Scholar

Said, Edward. 1978. Orientalism. New York: Pantheon Books.Search in Google Scholar

Santos, Boaventura de Sousa. 2014. Epistemologies of the south: Justice against epistemicide. London: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Sapiezynska, Ewa & Claudia Lagos. 2016. Media freedom indexes in democracies: A critical perspective through the cases of Poland and Chile. International Journal of Communication 10. 549–570.Search in Google Scholar

Schiller, Herbert I. 1969. Mass communications and the American empire. New York: A. M. Kelley.Search in Google Scholar

Shanghai Ranking. 2023. Shanghai Ranking’s global ranking of academic subjects 2023 – communication. Available at: https://www.shanghairanking.com/rankings/gras/2023/RS0507.Search in Google Scholar

Soares, Marcelo. 2021. Radiografia das Lives e Discursos de Bolsonaro Mostra Escalada de Autoritarismo e Desinformação. El País Brasil. Available at: https://brasil.elpais.com/brasil/2021-07-25/radiografia-das-lives-e-discursos-de-bolsonaro-mostra-escalada-de-autoritarismo-e-desinformacao.html.Search in Google Scholar

Suzina, Ana C. 2021. English as Lingua Franca: On the sterilization of scientific work. Media, Culture & Society 43(1). 171–179. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443720957906.Search in Google Scholar

Waisbord, Silvio. 2022. What is next for de-westernizing communication studies? Journal of Multicultural Discourses 17(1). 26–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/17447143.2022.2041645.Search in Google Scholar

Wardle, Claire & Hossein Derakhshan. 2017. Information disorder: Toward an interdisciplinary framework for research and policy making Council of Europe report DGI. Available at: https://edoc.coe.int/en/media/7495-information-disorder-toward-an-interdisciplinary-framework-for-research-and-policy-making.html.Search in Google Scholar

World Bank. 1997. Helping countries combat corruption: The role of the World Bank. Washington, DC: World Bank.Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Structural challenges for the global circulation of knowledge and scientific sovereignty in a multipolar world

- Research Articles

- Academic imperialism meets media imperialism: the case of Abraji in Brazil

- Geographic tokenism on editorial boards: a content analysis of highly ranked communication journals

- Exploring the link between research funding, co-authorship and publication venues: an empirical study in communication, political science, and sociology

- Valuing diversity, from afar – A scientometric analysis of the Global North countries overrepresentation in top communication journals

- China’s policies and investments in metaverse and AI development: implications for academic research

- Democratizing publishing in communication/media studies: a case study of Communication, Culture & Critique

- Multilingual science: discussing language as a place of encounter in knowledge production and exchange

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Structural challenges for the global circulation of knowledge and scientific sovereignty in a multipolar world

- Research Articles

- Academic imperialism meets media imperialism: the case of Abraji in Brazil

- Geographic tokenism on editorial boards: a content analysis of highly ranked communication journals

- Exploring the link between research funding, co-authorship and publication venues: an empirical study in communication, political science, and sociology

- Valuing diversity, from afar – A scientometric analysis of the Global North countries overrepresentation in top communication journals

- China’s policies and investments in metaverse and AI development: implications for academic research

- Democratizing publishing in communication/media studies: a case study of Communication, Culture & Critique

- Multilingual science: discussing language as a place of encounter in knowledge production and exchange