Abstract

Purpose

Despite the increasing volume of research addressing the relevance of de-Westernizing Media Studies, we lack a comparative evaluation of the performance of Global South universities regarding their presence in the most prestigious domains within the field of Communication. Against this background, the article explores if and to what extent the publication of articles authored by BRICS-based scholars in top-ranked journals is restricted to a handful of academic institutions – making them a national “elite” authorized to engage in the mainstream intellectual debate.

Design/methodology/approach

We pose three questions: RQ1) To what extent is the academic output of BRICS countries in the field of Communication concentrated within a select few “top-level” institutions? RQ2) How are the research articles from the most productive universities distributed across the journal rankings comprising the SJR database? RQ3) What partnerships do institutions from BRICS countries engage in when producing research articles? Using data from the SciVal (Elsevier) and SJR (SCImago Journal Rank) platforms, the empirical study encompasses a set of articles published between 2012 and 2021.

Findings

Our findings reveal that South Africa, Russia, and Brazil had the highest concentration of academic production within a select few universities. The disparities among the most and least productive universities can be attributed to a lack of ambitious policies in terms of academic innovation. The contrast becomes more evident when we consider China’s performance – which has implemented a range of strategies to foster international partnerships with Western academic communities.

Practical implications/social implications

We contend that the demand for “de-Westernization” must go beyond a mere plea for increased numerical representation. The exclusion of perspectives or phenomena from developing regions hinders the progress of knowledge production itself. Once Social and Human Sciences traditionally occupy a peripheral position in terms of funding, it is as if Communication researchers based in the Global South were part of a “periphery of the periphery.”

Originality/value

The paper is relevant for enabling us to discuss Global South universities’ international insertion and the dynamics influencing the academic contributions of semi-peripheral communities. We also consider to what extent the SciVal and SJR metrics reinforce an academic rationale that upholds the mechanisms of neoliberal globalization and the standardization of the scholarly agenda.

1 Introduction

The scholarly literature has increasingly scrutinized the challenges that Global South-based researchers face when trying to circulate in prestigious journals within the field of Communication Research (Ai and Masood 2021; Albuquerque 2021; Ganter and Ortega 2019; Mutsvairo et al. 2021). The requirement to submit papers in English (Cheruiyot 2021), the paywalls maintained by commercial publishers (Oliveira et al. 2021), and the underrepresentation of scholars from peripheral universities on editorial boards (Albuquerque et al. 2020) fuel a framework that not only shapes what is deemed “relevant” or “interesting” (Goyanes 2020) but also leads to the isolation of non-mainstream academic communities.

Despite the growing demand for a more “de-Westernized” approach to knowledge production, progress in this direction remains limited (Demeter 2020; Ekdale et al. 2022a; Hanusch and Vos 2020; Mitchelstein and Boczkowski 2021; Oliveira et al. 2021). To illustrate, one of the most prominent journals in Human and Social Sciences, Political Communication, has recently published an editorial stating: “After conducting an internal audit of scholars from around the globe who have reviewed for Political Communication in recent years … […] We are excited to announce the first fruits of this effort: The addition of two new editorial board members [one from Argentina and another from Chile]” (Lawrence 2023: 3). It is worth noting that these two new board members are the only ones working for Latin American universities, while the United States alone has 26 out of the 42 scholars listed in that same group.

Against this backdrop, our research explores some intriguing aspects concerning the presence of Global South universities in prestigious scholarly platforms. More precisely, we aim to explore if and to what extent access to these publishing venues is restricted to a handful of academic institutions – making them a type of national “elite” authorized to engage in the mainstream intellectual debate. We take as a premise that the differences in academic capital – and consequently, in resources and opportunities for international partnerships – perceived between universities in the Global North and South (Demeter 2019b) can also occur within the countries themselves (Monteiro and Hirano 2020). In fact, the literature has already suggested that due to the scarce availability of funding to invest in all in-country institutions, developing nations tend to concentrate their money on historically more productive intellectual centers (Oleksiyenko and Yang 2015).

Our study entails a comparative analysis of several metrics to gauge the circulation of universities affiliated with BRICS countries (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa) within journals indexed in the SCImago Journal Rank (SJR). Three research questions specifically related to the field of Communication guide this paper. RQ1) To what extent is the academic output of BRICS countries concentrated within a select few “top-level” institutions? RQ2) How are the research articles from the most productive universities distributed across the journal rankings comprising the SJR database? RQ3) What partnerships do institutions from BRICS countries engage in when producing research articles? Using data from the SciVal and SJR platforms, our paper encompasses a large set of articles published between 2012 and 2021.

Analyzing the representation of BRICS institutions in mainstream academic outlets is relevant for different reasons. First, despite the increasing volume of research on the importance of de-Westernizing Media Studies (Demeter 2020; Ekdale et al. 2022b; Waisbord and Mellado 2014), we still lack a comprehensive and comparative evaluation of the BRICS universities’ performance regarding their presence in the most prestigious domains within the field of Communication. Second, as Demeter (2020: 98) contends, “academic institutions are the primary agents forming the global capital that underpins the knowledge production of the present world system.” However, the rationale behind investment in research and development not only differs when contrasting central and peripheral countries but also hinges upon the strategies adopted by each university. For example, while the leading educational institutions in North America benefit from foundations endowed with billion-dollar funds (Demeter 2020), university systems in poorer countries often rely on government funding, making them vulnerable to budgetary restrictions and political pressure (Altbach and Bassett 2014). Investigating how a group of countries from the Global South compete for “elite” positions in knowledge production enables us to map and discuss their strategies for international insertion.

A third justification is that understanding institutional performance allows us to uncover the varied realities and dynamics influencing the academic contributions of semi-peripheral communities (Monteiro and Hirano 2020). Fourth, universities in developing nations recurrently make decisions about which professors to hire or promote based on publication rates in prestigious journals (Demeter et al. 2022; Paasi 2005). In this regard, our study considers to what extent the SciVal and SJR metrics reinforce an academic rationale that upholds the mechanisms of neoliberal globalization (Amsler and Bolsmann 2012; Paasi 2005; Slaughter and Leslie 2001) and the standardization of the scholarly agenda in accordance with validation benchmarks adopted in the Global North (Albuquerque et al. 2020).

2 Communication studies and the Global South

Scholars based in non-mainstream countries face a range of challenges often overlooked by researchers from Western Europe and the United States (Demeter 2020; Waisbord and Mellado 2014) – including the requirement to attain proficiency in the English language for publication in top-ranked journals (Ganter and Ortega 2019; Livingstone 2007), limited resources for conducting empirical studies (Ai and Masood 2021), or demands to incorporate “riders” in the titles of their works to underline geographical limitation (Harb 2023; Rojas and Valenzuela 2019). In contrast, publications from developed countries often forego the need for such contextual explanations, as it is assumed that readers must already be familiar with figures like Donald Trump or organizations such as “The New York Times.”

Furthermore, the predominance of reviewers and editors from the Global North on the editorial boards of top-ranked journals might play a pivotal role in excluding alternative viewpoints (Albuquerque et al. 2020; Ganter and Ortega 2019; Oliveira et al. 2021) – whether by deliberate judgment (certain subjects can be deemed “irrelevant”) or due to a lack of familiarity with theories and methods that are better suited for understanding local contexts. In addition, international rankings and commercial databases operate as gatekeepers as Global South journals struggle to meet specific requirements to be included on lists such as the Journal Citation Reports (JCR) and SCImago Journal & Country Rank (SJR). Albuquerque (2021: 3) states, “this system artificially introduces scarcity and homogeneity, as it denies full international status to the journals that are not present in the list.” In this regard, “de-Westernizing” entails the study of Communication phenomena with the aim of developing concepts and categories able to transcend traditional geopolitical borders (Goyanes 2020; Pimentel and Marques 2021; Waisbord and Mellado 2014).

In this article, we use the Global North and South conceptions based on Demeter’s (2020) work, which classifies the South as comprising geopolitically dependent and historically colonized or exploited nations – namely, most of Latin America, Africa, the Middle East, non-Westernized Asia, and Eastern Europe. Nevertheless, we do not imply homogeneity among these nations. In tandem with Kürzdörfer and Narlikar (2023), we contend that “the term ‘Global South’ should be taken for what it is – a useful shortcut to engage with countries that are too often and too easily dismissed as ‘the rest.’ It needs to be used with care to avoid stereotyping and essentialization.” Accordingly, the authors claim that concepts like the “Third World” or “developing countries” are always simplifications. “Whether the West likes it [the term “Global South”] or not, many countries from the world regions do share memories, myths, imaginations, and lived experiences of colonialism, deprivation, and marginalization.” Kürzdörfer and Narlikar (2023) continue by sustaining that “even while policy-makers and think tankers in the West are rejecting the term, countries from the Global South are reclaiming it, as witnessed in the Voice of the Global South Summit, which was organized by India in January 2023.”

Truth be told, maybe the BRICS countries could be more accurately characterized as semi-peripheral insofar as they possess better resources and academic prominence when compared to poorer nations (Bennett 2014; Monteiro and Hirano 2020; Oleksiyenko and Yang 2015). The bloc – consisting of Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa and ready to admit six new countries in January 2024 (Argentina, Egypt, Iran, Ethiopia, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates) (Borger 2023) – aims to foster cooperation among emerging economies to defy the dominant logic of global trade (de Coning et al. 2015). Indeed, the group also has marked economic and political differences (Fourcade 2013). Some pundits even raise criticism about an allegedly “artificial character” of the BRICS, indicating that the acronym itself would be the group’s most significant strength (Aouragh and Chakravartty 2016). However, there is no doubt that in terms of economy and foreign policy, such collaborations have had results, such as the increasing relevance of the BRICS Bank. Furthermore, the interest of other nations in joining the group demonstrates the strength of BRICS on the world stage.

The alliance also allegedly nurtures academic partnerships (Finardi 2015; Kahn 2015) through initiatives such as the BRICS Think Tanks Council (BTTC), which is committed to training and empowering intellectual communities within the member countries. However, many actions being carried out (such as the BRICS Network University) prioritize a limited set of areas (Toledo 2023): energy, computer science, climate change, and water resources. Accordingly, data from the Web of Science demonstrate that between 2011 and 2019, BRICS countries published articles mainly in Chemistry, Materials Science, Engineering, and Physics. Articles from the Social Sciences, Humanities, and Arts comprised less than 1 % of the total (Príncipe 2020) – which reinforces the relevance of studying the unique challenges affecting the integration of Communication researchers based in non-Western countries into more prestigious academic circuits (Albuquerque 2023; Demeter 2019a; Fan et al. 2022; Monteiro and Hirano 2020).

If the “BRICS perspective refers to a common agenda of the struggle for recognition, shared by a group of countries questioning the U.S.-centered unipolar order” (Albuquerque and Lycarião 2018: 2878), what opportunities can such alliance bring to these countries’ universities? On the one side, reputable academic institutions aim to draw in highly productive professors and a larger student body, as individuals recognize that the university’s prestige can offer better job opportunities (Delgado-Márquez et al. 2012). On the other hand, the public influence of their researchers, along with citations in high-impact journals (Marginson 2006), plays a pivotal role in shaping the public perception of educational institutions, as well as in securing research funding.

When analyzing three different university rankings (the Shanghai List, The Times Higher Education Ranking, and the QS List), Demeter (2020) found a discernible waning in the dominance of American universities and a noteworthy surge in China’s academic output and visibility – although this result does not necessarily translate into a reduction in Western influence in the short term. Accordingly, data from the 2023 edition of the Times Higher Education Ranking (Elsevier) (Times Higher Education 2023) highlights the disparity in China’s performance compared to the other BRICS countries. Within the top 500 institutions in the field of Communication and Media, China boasts a total of 20 institutions (with seven of them ranking within the top 100). In contrast, Brazil and India each have two institutions on this list, while Russia has three, and South Africa counts four universities represented. The Shanghai Ranking (Academic Ranking of World Universities 2022) listed three Chinese institutions among the top 300 in the field in 2022 – and only one other BRICS organization appeared in the ranking, the Stellenbosch University, from South Africa. Nonetheless, using rankings to assess universities has encountered substantial criticism (David and Motala 2017). Rauhvargers (2013) argues that these classifications can reinforce the prominence of elite institutions, downplay the importance of the Humanities and Social sciences, and perpetuate the dominance of English-language publications.

One strategy peripheral and semi-peripheral countries adopt to enhance their universities’ global impact is to include nationally-edited journals in databases such as the SJR. However, only 21 of the 439 journals (base year 2021) listed in this database originate from one of the five BRICS nations – ten from Brazil, six from Russia, two from India, two from South Africa, and one from China (Appendix, Table 1a).

The predominance of SJR journals based in English-speaking countries is illustrated by the fact that the United Kingdom and the United States hold no less than 242 periodicals (159 and 83, respectively), representing more than half of the list. Other 42 countries host the remaining titles (Appendix, Table 2a), and many accept submissions in English only. When it comes to the degree of impact, the influence of American and British journals is even more striking: of the 112 SJR publications classified in Q1, 54 are led by the British and 32 by Americans – which corresponds to 76.8 % of the entire Communication area most prestigious SJR stratum. In the case of BRICS, Brazil is the sixth country on the list with the largest number of journals. However, even SJR Brazilian periodicals also accept articles in English. To illustrate, the Brazilian Journalism Research journal accepts submissions in Portuguese, Spanish, French, or English – but if the paper approved is written in one of the first three languages, authors must necessarily prepare an English version at their expense (Brazilian Journalism Research 2023).

Another strategy recurrently used by Global South scholars to strengthen their presence in high-impact journals involves collaborating with international colleagues. According to Fan et al. (2022), between 2011 and 2020, institutions from BRICS countries expanded their overseas partnerships, albeit with notable variations. Brazil, South Africa, and Russia predominantly cooperated through a few prestigious in-country universities. On the other hand, China and India showed a more evenly distributed scenario – although in the Chinese case, the “top-level” universities were primarily located in Beijing, Shanghai, Jiangsu, Hubei, and Shaanxi (Dong et al. 2020). Therefore, universities’ international reputation and influence are intricately tied to each country’s administrative policies in higher education. For instance, political interference or excessive bureaucracy in allocating research resources can hinder efforts to foster scientific innovation (Altbach and Bassett 2014).

Considering the discussion above, as well as the need to understand how the BRICS countries and universities have been incorporated into internationally prestigious and widely recognized databases, our article puts forth three questions:

To what extent is the academic output of BRICS countries in the field of Communication concentrated within a select few “top-level” institutions?

How are the research articles from the most productive universities distributed across the journal rankings comprising the SJR database?

What partnerships do institutions from BRICS countries engage in when producing research articles?

3 Methods

3.1 Defining “elite” journals

The literature focusing on knowledge production has no consensus regarding the definition of “elite” journals. Generally speaking, the most prestigious publications are identified as those included in international databases – with emphasis on the Web of Science (Albuquerque et al. 2020; Demeter 2019a; Santos et al. 2023) and Scopus (Demeter 2020; Ganter and Ortega 2019; González-Pereira et al. 2010; Goyanes and Demeter 2021).

Our research considers Scopus data from SciVal to offer a more inclusive approach than investigations emphasizing only journal databases such as JCR (Clarivate) (Albuquerque et al. 2023; Goyanes and de-Marcos 2020). Of course, we acknowledge the criticisms regarding the use of rankings operated by private companies (Albuquerque et al. 2020; Aouragh and Chakravartty 2016; Cooley and Snyder 2015; Demeter et al. 2022). At the same time, one cannot disregard the impact that databases such as the SJR and SciVal have on the global visibility of researchers and universities. In other words, by recognizing the dynamics associated with securing an institutional presence in these spaces, we can better understand the prevailing patterns of exclusion within the academic landscape while examining possible alternatives for overcoming these problems.

3.2 Data collection and analysis

We accessed the SciVal platform (Elsevier) to compile a spreadsheet containing the metadata of Communication research papers. These metadata included details such as the journal of publication (source title), year of publication, authors, and their respective institutions. We focused on articles published by authors based in at least one of the five BRICS countries, excluding texts such as book reviews and editor’s comments. This initial data collection identified 8,618 papers published between 2012 and 2021.

While SciVal offers data on universities and quantitative production, the SCImago Journal & Country Rank (SJR) classifies academic journals according to their influence and repercussions across different areas of knowledge. This study considered the 447 Communication journals listed in the base year 2021. However, eight of such periodicals were listed but not placed in one of the quartiles at the time. Therefore, our primary focus relies on the 439 journals distributed among Q1, Q2, Q3, and Q4 levels (Appendix, Table 2a). The cross-analysis from both databases enabled us to pinpoint 7,938 articles published in SJR-indexed journals that involved authors affiliated with at least one institution based in the BRICS countries. The slight decrease in the number of documents (compared to the initial data collection) can be attributed to the fact that some journals may have been discontinued during the ten years under investigation, or newly included journals might not have received an SJR classification at the time we collected the data.

Using both SciVal and SJR information, we listed the universities mentioned in the authorship of each article, as well as each paper’s journal performance according to the four quartiles of the SJR scale (Q1, Q2, Q3, and Q4). To comprehensively analyze the most prolific institutions in the field of Communication in the five BRICS partners, our research identified the top 20 universities in each country that published the most articles from 2012 to 2021 – resulting in 100 organizations. In cases of tie, priority was given to the university with the most significant number of articles published in Q1 journals (the highest quartile).

4 Findings

4.1 Performance of BRICS-based universities in the field of communication

Between 2012 and 2021, researchers affiliated with BRICS universities published 7,938 articles in SJR-indexed journals within the field of Communication. Table 1 displays that Brazil- and China-based authors published over twice the number of articles compared to South African (1,106 pieces) and Indian (1,015) scholars. Russia had the lowest number of publications over the decade, with 853 articles.

Total number of articles from each country (2012–2021).

| Country | Number of published articles (2012–2021) | Country’s participation compared to the group’s total publications |

|---|---|---|

| Brazil | 2,667 | 33.6 % |

| China | 2,297 | 28.9 % |

| South Africa | 1,106 | 13.9 % |

| India | 1,015 | 12.8 % |

| Russia | 853 | 10.7 % |

| TOTAL | 7,938 | 100 % |

-

Source: The authors with data from SciVal (2022) and SJR (2021).

In 2022, Brazil had 2,595 higher education institutions, of which 2,283 were private and 312 were public (Secom 2023). According to Table 2, researchers affiliated with the University of São Paulo (USP) contributed to 299 articles, accounting for 11.2 % of the 2,667 papers published by the country over the decade. Additionally, the São Paulo State University Júlio de Mesquita Filho (UNESP) made a notable contribution with 217 works, representing 8.13 % of the country’s total. Plus, these two institutions take the lead when considering all BRICS member countries. The data also reveals an intriguing concentration of article production within the field of Communication among Brazilian institutions – the top 20 universities accounted for 2,324 articles, whether in partnership or not.

Brazilian institutions with the highest number of published articles and their distribution across SJR quartiles.

| University | Total publications/% in relation to each country’s total | Publications from the university with partnerships/% of the institution’s total | Publications from the university without partnerships/% of the institution’s total | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| University of São Paulo | 299 (11.2 %) | 165 (55.2 %) | 134 (44.8 %) | 23 (7.7 %) | 154 (51.5 %) | 66 (22 %) | 56 (18.7 %) |

| São Paulo State University Júlio de Mesquita Filho | 217 (8.1 %) | 111 (51.2 %) | 106 (48.8 %) | 6 (2.8 %) | 42 (19.3 %) | 95 (43.8 %) | 74 (34.1 %) |

| Federal University of Rio de Janeiro | 187 (7 %) | 123 (65.8 %) | 64 (34.2 %) | 20 (10.7 %) | 90 (48.1 %) | 53 (28.3 %) | 24 (12.8 %) |

| Federal University of Minas Gerais | 150 (5.6 %) | 77 (51.3 %) | 73 (48.6 %) | 24 (16 %) | 49 (32.7 %) | 58 (38.7 %) | 19 (12.6 %) |

| Oswaldo Cruz Foundation | 142 (5.3 %) | 81 (57 %) | 61 (43 %) | 5 (3.5 %) | 132 (92.9 %) | 4 (2.8 %) | 1 (0.7 %) |

| Federal University of Santa Catarina | 137 (5.1 %) | 61 (44.5 %) | 76 (55.5 %) | 25 (18.2 %) | 58 (42.3 %) | 40 (29.2 %) | 14 (10.2 %) |

| University of Brasília | 133 (4.9 %) | 69 (51.9 %) | 64 (48.1 %) | 12 (9 %) | 58 (43.6 %) | 50 (37.6 %) | 13 (9.7 %) |

| Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul | 116 (4.3 %) | 59 (50.9 %) | 57 (49.1 %) | 5 (4.3 %) | 78 (67.2 %) | 21 (18.1 %) | 12 (10.3 %) |

| Fluminense Federal University | 111 (4.1 %) | 55 (49.5 %) | 56 (50.5 %) | 17 (15.3 %) | 41 (36.9 %) | 17 (15.3 %) | 36 (32.4 %) |

| State University of Campinas | 107 (4 %) | 52 (48.6 %) | 55 (51,4 %) | 7 (6.5 %) | 73 (68.2 %) | 10 (9.3 %) | 17 (15.9 %) |

| Federal University of São Paulo | 105 (3.9 %) | 48 (45.7 %) | 57 (54.3 %) | 6 (5.7 %) | 95 (90.5 %) | 1 (0.9 %) | 3 (2.8 %) |

| Federal University of Paraíba | 92 (3.4 %) | 60 (65.2%) | 32 (34.8 %) | 2 (2.2 %) | 43 (46.7 %) | 45 (48.9 %) | 2 (2.2 %) |

| Federal University of Bahia | 86 (3.2 %) | 59 (68.6 %) | 27 (31.4 %) | 3 (3.5 %) | 47 (54.6 %) | 27 (31.4 %) | 9 (10.5 %) |

| Federal University of Pernambuco | 79 (2.9 %) | 48 (60.8 %) | 31 (39.2 %) | 6 (7.6 %) | 26 (32.9 %) | 28 (35.4 %) | 19 (24 %) |

| Rio de Janeiro State University | 77 (2.8 %) | 42 (54.5 %) | 35 (45.4 %) | 7 (9 %) | 47 (61 %) | 12 (15.6 %) | 11 (14.3 %) |

| Federal University of São Carlos | 65 (2.4 %) | 43 (66.2 %) | 22 (33.8 %) | 0 | 42 (64.6 %) | 8 (12.3 %) | 15 (23 %) |

| Federal University of Paraná | 64 (2.3 %) | 32 (50 %) | 32 (50 %) | 13 (20.3 %) | 19 (29.7 %) | 17 (26.5 %) | 15 (23.4 %) |

| State University of Londrina | 59 (2.2 %) | 30 (50.8 %) | 29 (49.2 %) | 2 (3.4 %) | 12 (20.4 %) | 14 (23.7 %) | 31 (52.5 %) |

| Federal University of Ceará | 58 (2.1 %) | 41 (70.7 %) | 17 (29.3 %) | 8 (13.8 %) | 26 (44.8 %) | 15 (25.8 %) | 9 (15.5 %) |

| Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte | 40 (1.4 %) | 27 (67.5 %) | 13 (32.5 %) | 1 (2.5 %) | 24 (60 %) | 10 (25 %) | 5 (12.5 %) |

| TOTAL | 2,324 | 192 | 1,156 | 591 | 385 | ||

| 1,283 (55.2 %) | 1,041 (44.8 %) |

-

Source: The authors with data from SciVal (2022) and SJR (2021).

Concerning partnerships, the data revealed that 55.2 % of Brazilian top 20 universities’ research papers resulted from interinstitutional collaborations, whereas 44.8 % of the works were authored by individuals affiliated with a single institution. Notably, the Federal University of Ceará (70.7 % of its publications), the Federal University of Bahia (68.6 %), and the Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte (67.5 %) stood out in terms of co-authorship with national and/or international institutions.

When considering the SJR classification of the journals in which the 2,667 articles were published, only circa 10 % of the articles authored by researchers tied to Brazilian institutions (269 works) fall within the highest stratum. The University of São Paulo (USP) had only 7.7 % of its articles in Q1 outlets, while UNESP did not exceed 3 %. On average, publications from all Brazilian universities within the field of Communication are predominantly concentrated in Q2 journals, accounting for 1,211 articles – which represents 45.4 % of the country’s total publications. Additionally, 667 papers (25 % of the total) were published in Q3 journals, and 520 other studies appeared in journals classified as Q4 (the State University of Londrina, for instance, published more than 52 % of its articles in the lowest classification stratum). The Appendix includes a set of figures that visually represent the performance of the leading universities in each of the BRICS countries.

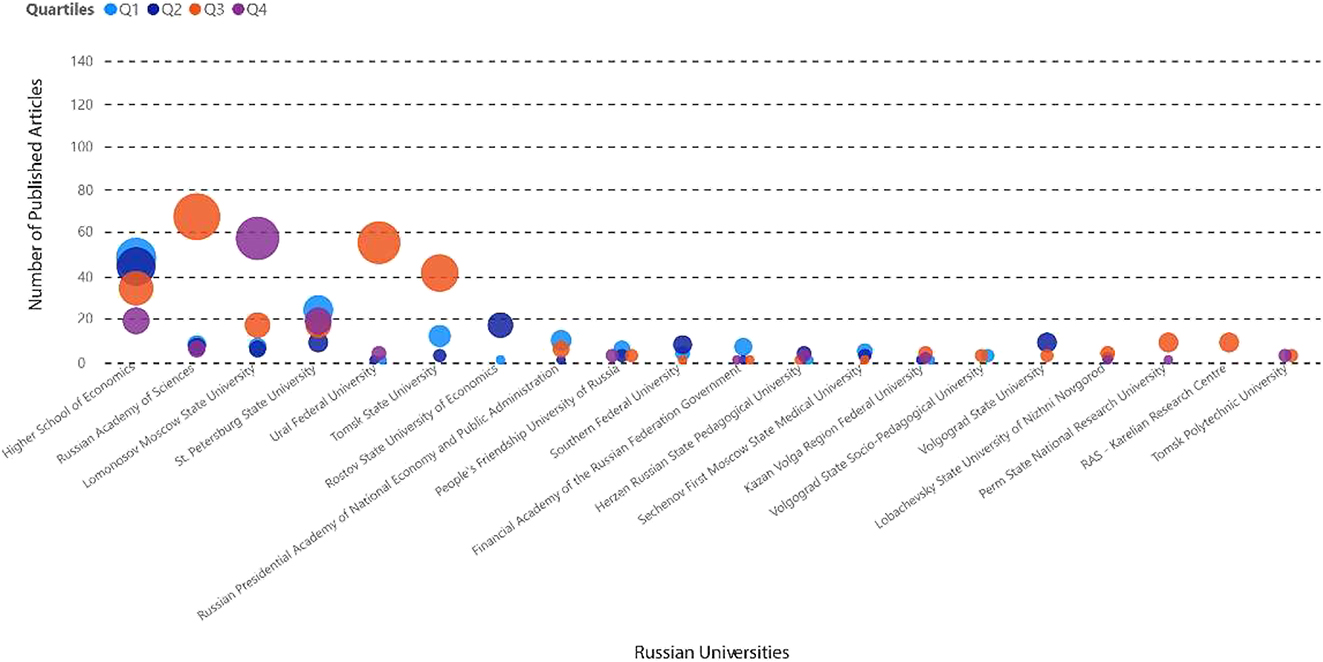

Russia counts 658 state-owned and 450 private civilian university-level institutions licensed by the Ministry of Education (UNDP 2009). The country’s top 20 prolific institutions contributed to 655 research papers (Table 3). Researchers affiliated with the Higher School of Economics hold the leading position, accounting for 145 of the 853 Russian publications (17 % of the country’s total). The second institution with the highest number of publications is the Russian Academy of Sciences, with 88 papers authored by its researchers, accounting for 10.3 % of the nation’s output. The Lomonosov Moscow State University (87 articles, or 10.1 %), the St. Petersburg State University (69 papers, or 8 %), and the Ural Federal University (61 articles, or 7.1 %) also achieved noteworthy performance.

Russian institutions with the highest number of published articles and their distribution across SJR quartiles.

| University | Total publications/% in relation to each country’s total | Publications from the university with partnerships/% of the institution’s total | Publications from the university without partnerships/% of the institution’s total | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Higher School of Economics | 145 (17 %) | 56 (38.6 %) | 89 (61.4 %) | 48 (33.1 %) | 44 (30.3 %) | 34 (23.5 %) | 19 (13.1 %) |

| Russian Academy of Sciences | 88 (10.3 %) | 46 (52.3 %) | 42 (47.7 %) | 8 (9 %) | 7 (7.9 %) | 67 (76.1 %) | 6 (6.9 %) |

| Lomonosov Moscow State University | 87 (10.1 %) | 9 (10.3 %) | 78 (89.7 %) | 7 (8 %) | 6 (6.9 %) | 17 (19.5 %) | 57 (65.5 %) |

| St. Petersburg State University | 69 (8 %) | 33 (47.8 %) | 36 (52.2 %) | 24 (34.8 %) | 9 (13 %) | 17 (24.6 %) | 19 (27.5 %) |

| Ural Federal University | 61 (7.1 %) | 18 (29.5 %) | 43 (70.5 %) | 1 (1.6 %) | 1 (1.6 %) | 55 (90.1 %) | 4 (6.6 %) |

| Tomsk State University | 56 (6.5 %) | 19 (33.9 %) | 37 (66.1 %) | 12 (21.4 %) | 3 (5.3 %) | 41 (73.2 %) | 0 |

| Rostov State University of Economics | 18 (2.1 %) | 1 (5.5 %) | 17 (94.5 %) | 1 (5.5 %) | 17 (94.4 %) | 0 | 0 |

| Russian Presidential Academy of National Economy and Public Administration | 17 (2 %) | 6 (35.3 %) | 11 (64.7 %) | 10 (58.8 %) | 1 (5.9 %) | 6 (35.3 %) | 0 |

| People’s Friendship University of Russia | 15 (1.7 %) | 9 (60 %) | 6 (40 %) | 6 (40 %) | 3 (20 %) | 3 (20 %) | 3 (20 %) |

| Southern Federal University | 13 (1.5 %) | 7 (53.8 %) | 6 (46.2 %) | 4 (30.8 %) | 8 (61.5 %) | 1 (7.7 %) | 0 |

| Volgograd State University | 12 (1.4 %) | 9 (75 %) | 3 (25 %) | 0 | 9 (75 %) | 3 (25 %) | 0 |

| Financial Academy of the Russian Federation Government | 10 (1.1 %) | 9 (90 %) | 1 (10 %) | 7 (70 %) | 1 (10 %) | 1 (10 %) | 1 (10 %) |

| Perm State National Research University | 10 (1.1 %) | 6 (60 %) | 4 (40 %) | 0 | 0 | 9 (90 %) | 1 (10 %) |

| Sechenov First Moscow State Medical University | 9 (1 %) | 8 (88.8 %) | 1 (11.1 %) | 5 (55.5 %) | 3 (33.3 %) | 1 (11.1 %) | 0 |

| Herzen Russian State Pedagogical University | 9 (1 %) | 5 (55.5 %) | 4 (44.4 %) | 1 (11.1 %) | 4 (44.4 %) | 1 (11.1 %) | 3 (33.3 %) |

| RAS – Karelian Research Centre | 9 (1 %) | 8 (88.8 %) | 1 (11.1 %) | 0 | 0 | 9 (100 %) | 0 |

| Kazan Volga Region Federal University | 8 (0.9 %) | 5 (62.5 %) | 3 (37.5 %) | 1 (12.5 %) | 1 (12.5 %) | 4 (50 %) | 2 (25 %) |

| Lobachevsky State University of Nizhni Novgorod | 7 (0.8 %) | 4 (57.1 %) | 3 (42.9 %) | 0 | 2 (28.6 %) | 4 (57.1 %) | 1 (14.3 %) |

| Tomsk Polytechnic University | 6 (0.7 %) | 4 (66.6 %) | 2 (33.3 %) | 0 | 0 | 3 (50 %) | 3 (50 %) |

| Volgograd State Socio-Pedagogical University | 6 (0.7 %) | 5 (83.3 %) | 1 (16.6 %) | 3 (50 %) | 0 | 3 (50 %) | 0 |

| TOTAL | 655 | 138 | 119 | 279 | 119 | ||

| 267 (40.7 %) | 388 (59.3 %) |

-

Source: The authors with data from SciVal (2022) and SJR (2021).

The average percentage of papers published through partnerships in Russia’s leading institutions stood at 40.7 %. In other words, most papers (more specifically, 59.3 %) did not involve interinstitutional co-authorships. On the one hand, the Financial Academy of the Russian Federation Government (90 % of articles resulting from partnerships), the Sechenov First Moscow State Medical University (88.8 % of collaborative works), and the RAS–Karelian Research Center (also 88.8 %) were prominent when it comes to collaborations. On the other hand, the Rostov State University of Economics and the Lomonosov Moscow State University recorded 94.5 and 89.7 % of their publications, respectively, without the involvement of scholars affiliated with other institutions.

Table 3 indicates that the Russian university with the greatest portion of published articles in absolute numbers also achieved the best performance regarding publications in top-ranked journals. The Higher School of Economics accounted for 48 (33.1 % of the country’s total) of the 145 Russia-based papers in Q1 journals and more 44 documents (30.3 %) in Q2 journals. The Russian Academy of Sciences, in turn, published the vast majority of its papers in Q3 journals (67 of its 88 articles, or 76.1 %). Five Russian universities did not manage to publish papers in Q1 journals.

Considering Russia’s 853 publications over the ten years under investigation, the data reveal that Russian researchers proportionally outperformed Brazilians in Q1 journals, with 139 articles published (constituting 16.3 % of their total publications). Nevertheless, in absolute numbers, most articles from Russia were published in Q3 journals (amounting to 376 texts, or 44 % of the country’s total).

South Africa, in turn, has fewer higher education institutions than its group’s partners: 26 public universities and 126 private universities in South Africa (Council on Higher Education 2022) – and this is probably one of the reasons why the country stands out with the highest concentration of papers involving a limited number of institutions (Table 4). The University of Johannesburg leads the way, as it participates in 213 publications, accounting for 19.2 % of the country’s 1,106 articles. Following are the University of Cape Town (132 authored articles, equivalent to 11.9 % of the country’s total), the University of the Witwatersrand (with 129 pieces, or 11.6 %), and the University of South Africa (with 106 articles, comprising 9.7 %). The top 20 South African institutions significantly contributed to the country’s performance, totaling 1,163 publications. Again, we stress that the article considers the participation of each university individually. Therefore, in the case of partnerships between two or more institutions, the paper is counted more than once.

South African institutions with the highest number of published articles and their distribution across SJR quartiles.

| University | Total publications/% in relation to each country’s total | Publications from the university with partnerships/% of the institution’s total | Publications from the university without partnerships/% of the institution’s total | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| University of Johannesburg | 213 (19.2 %) | 65 (30.5 %) | 148 (69.5 %) | 40 (18.7 %) | 34 (15.9 %) | 119 (55.9 %) | 20 (9.4 %) |

| University of Cape Town | 132 (11.9 %) | 38 (28.8 %) | 94 (71.2 %) | 41 (31 %) | 38 (28.8 %) | 40 (30.3 %) | 13 (9.8 %) |

| University of the Witwatersrand | 129 (11.7 %) | 42 (32.6 %) | 87 (67.4 %) | 37 (28.7 %) | 21 (16.3 %) | 56 (43.4 %) | 15 (11.6 %) |

| University of South Africa | 106 (9.6 %) | 27 (25.5 %) | 79 (74.5 %) | 18 (16.9 %) | 14 (13.2 %) | 65 (61.3 %) | 9 (8.5 %) |

| University of Stellenbosch | 101 (9.1 %) | 57 (56.4 %) | 44 (43.6 %) | 31 (30.7 %) | 38 (37.6 %) | 31 (30.7 %) | 1 (0.9 %) |

| University of KwaZulu-Natal | 90 (8.1 %) | 33 (36.7 %) | 57 (63.3 %) | 10 (11.1 %) | 24 (26.6 %) | 51 (56.6 %) | 5 (5.5 %) |

| University of Pretoria | 73 (6.6 %) | 31 (42.5 %) | 42 (47.5 %) | 24 (32.9 %) | 8 (10.9 %) | 33 (45.2 %) | 8 (10.9 %) |

| North-West University | 64 (5.8 %) | 34 (53.1 %) | 30 (46.9 %) | 24 (37.5 %) | 14 (21.9 %) | 25 (39 %) | 1 (1.6 %) |

| University of The Free State | 63 (5.7 %) | 34 (54 %) | 29 (46 %) | 13 (20.6 %) | 14 (22.2 %) | 21 (33.3 %) | 15 (23.8 %) |

| Rhodes University | 55 (4.9 %) | 16 (29 %) | 39 (71 %) | 17 (30.9 %) | 18 (32.7 %) | 19 (34.5 %) | 1 (1.8 %) |

| University of the Western Cape | 34 (3 %) | 10 (29.4 %) | 24 (70.6 %) | 12 (35.3 %) | 11 (32.3 %) | 7 (20.6 %) | 4 (11.8 %) |

| Tshwane University of Technology | 22 (1.9 %) | 7 (31.8 %) | 15 (68.2 %) | 1 (4.5 %) | 5 (22.7 %) | 11 (50 %) | 5 (22.7 %) |

| Cape Peninsula University of Technology | 18 (1.6 %) | 4 (22.2 %) | 14 (77.7 %) | 9 (50 %) | 4 (22.2 %) | 3 (16.6 %) | 2 (11.1 %) |

| University of Fort Hare | 17 (1.5 %) | 8 (47 %) | 9 (53 %) | 0 | 4 (23.5 %) | 11 (64.7 %) | 2 (11.8 %) |

| Nelson Mandela University | 11 (0.9 %) | 3 (27.3 %) | 8 (72.3 %) | 0 | 3 (27.2 %) | 8 (72.7 %) | 0 |

| Human Sciences Research Council South Africa | 10 (0.9 %) | 7 (70 %) | 3 (30 %) | 1 (10 %) | 6 (60 %) | 3 (30 %) | 0 |

| Durban University of Technology | 8 (0.7 %) | 4 (50 %) | 4 (50 %) | 2 (25 %) | 1 (12.5 %) | 3 (37.5 %) | 2 (25 %) |

| University of Venda | 7 (0.6 %) | 4 (57.1 %) | 3 (42.9 %) | 0 | 0 | 5 (71.4 %) | 2 (28.6 %) |

| University of Limpopo | 7 (0.6 %) | 0 | 7 (100 %) | 2 (28.6 %) | 1 (14.3 %) | 4 (57.1 %) | 0 |

| Council for Scientific and Industrial Research | 3 (0.3 %) | 3 (100 %) | 0 | 2 (66.6 %) | 1 (33.3 %) | 0 | 0 |

| TOTAL | 1,163 | 284 | 259 | 515 | 105 | ||

| 427 (36.7 %) | 736 (63.3 %) |

-

Source: The authors with data from SciVal (2022) and SJR (2021).

Moreover, 63.3 % of the articles published by South Africa’s most productive universities resulted from intra-institutional initiatives, that is, without involving partnerships with other organizations. The University of Limpopo published all its seven articles without the participation of other organizations, while the University of Johannesburg (the leader in published papers) had just over 30 % of co-authorships with other national or international entities.

As for the classification by quartiles, South Africa’s overall performance is as follows: 271 publications (or 24.5 % of its 1,106 papers) in Q1 journals, 239 publications (21.6 %) in Q2 periodicals, 496 articles (44.8 %) in Q3, and 100 articles (9 %) in Q4 outlets. However, being the leading institution in the number of publications does not necessarily mean a noticeable presence in the highest-ranking strata. For instance, only 18.7 % of the 213 papers from the University of Johannesburg were published in Q1 journals, while 15.9 % were in Q2 journals – proportionally lower than institutions such as the University of Cape Town and the University of the Witwatersrand. Besides, the Cape Peninsula University of Technology may not stand out in absolute numbers (18 articles published in the decade), but half of its research papers were published in Q1 journals. In general, there is a clear inclination toward Q3 journals in the case of South Africa. Akin to Russia, South Africa also has some of the top 20 institutions lacking a presence in Q1 Communication journals.

China and India are the only two BRICS countries with a more significant percentage of publications in Q1 journals than in other quartiles. As for China (Table 5), a country with 2,845 higher education institutions authorized by the government (Embaixada da República Popular da China no Brasil 2022), the institution with the highest number of publications was Zhejiang University – contributing 98 papers out of the total 2,297 (or 4.3 %). Following are the Shanghai Jiao Tong University, the Sun Yat-Sen University, and the Beijing Normal University, each with 87 articles (circa 3.8 % of the total). The top 20 Chinese universities published a total of 1,211 articles – revealing a proportionally lower rate compared to the other BRICS countries.

Chinese institutions with the highest number of published articles and their distribution across SJR quartiles.

| University | Total publications/% in relation to each country’s total | Publications from the university with partnerships/% of the institution’s total | Publications from the university without partnerships/% of the institution’s total | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zhejiang University | 98 (4.3 %) | 59 (60.2 %) | 39 (39.8 %) | 65 (66.3 %) | 21 (21.4 %) | 9 (9.2 %) | 3 (3 %) |

| Shanghai Jiao Tong University | 87 (3.8 %) | 59 (67.8 %) | 28 (32.2 %) | 61 (70.1 %) | 16 (18.4 %) | 6 (6.9 %) | 4 (4.6 %) |

| Sun Yat-Sen University | 87 (3.8 %) | 60 (69 %) | 27 (31 %) | 68 (78.1 %) | 13 (14.9 %) | 4 (4.6 %) | 2 (2.3 %) |

| Beijing Normal University | 87 (3.8 %) | 69 (79.3 %) | 18 (20.7 %) | 63 (72.4 %) | 18 (20.7 %) | 3 (3.4 %) | 3 (3.4 %) |

| Wuhan University | 80 (3.5 %) | 56 (70 %) | 24 (30 %) | 56 (70 %) | 15 (18.7 %) | 8 (10 %) | 1 (1.2 %) |

| Tsinghua University | 75 (3.3 %) | 52 (69,3) | 23 (30.7 %) | 57 (76 %) | 10 (13.3 %) | 5 (6.6 %) | 3 (4 %) |

| Fudan University | 74 (3.2 %) | 44 (59.5 %) | 30 (40.5 %) | 44 (59.5 %) | 23 (31 %) | 4 (5.4 %) | 3 (4 %) |

| Renmin University of China | 70 (3 %) | 53 (75.7 %) | 17 (24.3 %) | 53 (75.7 %) | 11 (15.7 %) | 5 (7.1 %) | 1 (1.4 %) |

| Peking University | 58 (2.5 %) | 39 (67.2 %) | 19 (32.8 %) | 43 (74.1 %) | 11 (19 %) | 3 (5.1 %) | 1 (1.7 %) |

| University of Nottingham Ningbo China | 56 (2.4 %) | 56 (100 %) | 0 (0 %) | 28 (50 %) | 18 (32.1 %) | 2 (3.6 %) | 8 (14.3 %) |

| Communication University of China | 52 (2.2 %) | 21 (40.4 %) | 31 (59.6 %) | 28 (53.8 %) | 12 (23 %) | 7 (13.5 %) | 5 (9.6 %) |

| University of Science and Technology of China | 52 (2.2 %) | 44 (84.6 %) | 8 (15.4 %) | 43 (82.7 %) | 9 (17.3 %) | 0 | 0 |

| Huazhong University of Science and Technology | 50 (2.1 %) | 34 (68 %) | 16 (32 %) | 37 (74 %) | 6 (12 %) | 4 (8 %) | 3 (6 %) |

| Guangdong University of Foreign Studies | 49 (2.1 %) | 31 (63.3 %) | 18 (36.7 %) | 23 (46.9 %) | 14 (28.6 %) | 11 (22.4 %) | 1 (2 %) |

| Nanjing University | 49 (2.1 %) | 36 (73.5 %) | 13 (26.5 %) | 36 (73.5 %) | 3 (6.1 %) | 8 (16.3 %) | 2 (4 %) |

| Nanjing Normal University | 40 (1.7 %) | 13 (32.5 %) | 27 (67.5 %) | 5 (12.5 %) | 1 (2.5 %) | 33 (82.5 %) | 1 (2.5 %) |

| Chinese Academy of Sciences | 38 (1.6 %) | 33 (86.8 %) | 5 (13.2 %) | 27 (71 %) | 10 (26.3 %) | 1 (2.6 %) | 0 |

| Shanghai University | 38 (1.6 %) | 27 (71 %) | 11 (28.9 %) | 18 (47.4 %) | 7 (18.4 %) | 10 (26.3 %) | 3 (7.9 %) |

| Jinan University | 36 (1.5 %) | 21 (58.3 %) | 15 (41.7 %) | 23 (63.9 %) | 7 (19.4 %) | 5 (13.9 %) | 1 (2.7 %) |

| Xiamen University | 35 (1.5 %) | 22 (62.9 %) | 13 (37.1 %) | 21 (60 %) | 9 (25.7 %) | 3 (8.6 %) | 2 (5.7 %) |

| TOTAL | 1,211 | 799 | 234 | 131 | 47 | ||

| 829 (68.5 %) | 382 (31.5 %) |

-

Source: The authors with data from SciVal (2022) and SJR (2021).

China also stands out for its substantial engagement in interinstitutional collaborations. In fact, the top 20 Chinese universities established partnerships with other organizations in 68.5 % of their research articles in Communication. The University of Nottingham Ningbo China case is particularly noteworthy, as all 56 of its works resulted from collaborations. In contrast, Nanjing Normal University had the lowest collaboration rate, with only 32.5 % of its articles featuring authors from other institutions.

Furthermore, researchers affiliated with Chinese universities have secured prominent positions in top-ranked journals. Between 2012 and 2021, they published 1,374 articles in Q1 journals, accounting for 59.8 % of the total of 2,297 works, and 527 articles in Q2 journals (22.9 % of the country’s total). Conversely, the number of articles from Chinese institutions decreases in less prestigious quartiles, with 282 works (12.3 %) in Q3 and 114 (4.9 %) in Q4 journals. Another noteworthy observation is that among the top 20 Chinese universities in our investigation, 14 have a proportion of articles published in Q1 journals that exceed the national average. For instance, the University of Science and Technology of China published 82.7 % of its articles in the highest stratum (Q1), with the remaining 17.3 % in Q2 (and none in Q3 or Q4). However, the Nanjing Normal University deviates from this pattern, with 82.5 % of its 40 works published in Q3 journals.

Concerning the general results for India (Table 6), whose number of university institutions is 1,113 (Ministry of Education 2023), Amity University Noida stands out with 47 works, accounting for 4.6 % of the total publications from that country. When considered as a group, the top 20 most prolific universities in India contributed 381 papers. Among these institutions, researchers collaborated with authors from other organizations in approximately 35 % of the articles. For example, the International Institute of Information Technology Hyderabad registers 70 % of its research articles featuring co-authors from other universities. Chandigarh University follows behind at 53.9 %, while Jamia Millia Islamia and Manipal Academy of Higher Education maintain a commendable 50 % collaboration rate. On the other end of the spectrum, the University of Hyderabad had the lowest collaboration rate in the decade, with only three out of its 17 research papers (or 15 %) resulting from cooperative efforts involving more than one organization.

Indian institutions with the highest number of published articles and their distribution across SJR quartiles.

| University | Total publications/% in relation to each country’s total | Publications from the university with partnerships/% of the institution’s total | Publications from the university without partnerships/% of the institution’s total | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amity University Noida | 47 (4.6 %) | 23 (48.9 %) | 24 (51.1 %) | 2 (4.2 %) | 6 (12.8 %) | 38 (80.8 %) | 1 (2.1 %) |

| Jawaharlal Nehru University | 31 (3 %) | 7 (22.6 %) | 24 (77.4 %) | 5 (16.1 %) | 2 (6.4 %) | 3 (9.7 %) | 21 (67.7 %) |

| University of Delhi | 29 (2.8 %) | 6 (20.7 %) | 23 (79.3 %) | 2 (6.9 %) | 8 (27.6 %) | 10 (34.5 %) | 9 (31 %) |

| Jamia Millia Islamia | 26 (2.5 %) | 13 (50 %) | 13 (50 %) | 11 (42.3 %) | 3 (11.5 %) | 7 (26.9 %) | 5 (19.2 %) |

| Vellore Institute of Technology | 23 (2.2 %) | 8 (34.8 %) | 15 (65.2 %) | 5 (21.7 %) | 8 (34.8 %) | 6 (26 %) | 4 (17.4 %) |

| Indian Institute of Technology Madras | 21 (2 %) | 7 (33.3 %) | 14 (66.7 %) | 16 (76.2 %) | 3 (14.3 %) | 2 (9.5 %) | 0 |

| University of Hyderabad | 20 (1.9 %) | 3 (15 %) | 17 (85 %) | 3 (15 %) | 12 (60 %) | 3 (15 %) | 2 (10 %) |

| Manipal Academy of Higher Education | 18 (1.7 %) | 9 (50 %) | 9 (50 %) | 0 | 4 (22.2 %) | 10 (55.5 %) | 4 (22.2 %) |

| Indian Institute of Technology Kharagpur | 17 (1.6 %) | 6 (35.3 %) | 11 (64.7 %) | 14 (82.3 %) | 2 (11.7 %) | 0 | 1 (5.9 %) |

| MICA | 16 (1.5 %) | 4 (25 %) | 12 (75 %) | 3 (18.7 %) | 9 (56.2 %) | 4 (25 %) | 0 |

| Symbiosis International University | 16 (1.5 %) | 3 (18.7 %) | 13 (81.3 %) | 1 (6.2 %) | 4 (25 %) | 9 (56.2 %) | 2 (12.5 %) |

| Anna University | 15 (1.4 %) | 6 (40 %) | 9 (60 %) | 6 (40 %) | 4 (26.6 %) | 3 (20 %) | 2 (13.3 %) |

| Guru Gobind Singh Indraprastha University | 14 (1.3 %) | 5 (35.7 %) | 9 (64.3 %) | 0 | 2 (14,3) | 9 (64.3 %) | 3 (21.4 %) |

| Indian Institute of Technology Guwahati | 14 (1.3 %) | 4 (28.6 %) | 10 (71.4 %) | 11 (78.6 %) | 2 (14.3 %) | 0 | 1 (7.1 %) |

| Indian Institute of Technology Bombay | 14 (1.3 %) | 5 (35.7 %) | 9 (64.3 %) | 7 (50 %) | 1 (7.1 %) | 2 (14.3 %) | 4 (28.6 %) |

| National Institute of Technology Karnataka | 13 (1.2 %) | 4 (30.8 %) | 9 (69.2 %) | 8 (61.5 %) | 4 (30.7 %) | 0 | 1 (7.7 %) |

| Indian Institute of Technology Delhi | 13 (1.2 %) | 5 (38.5 %) | 8 (61.5 %) | 8 (61.5 %) | 5 (38.5 %) | 0 | 0 |

| Chandigarh University | 13 (1.2 %) | 7 (53.9 %) | 6 (46.1 %) | 0 | 2 (15.4 %) | 10 (76.9 %) | 1 (7.7 %) |

| Jadavpur University | 11 (1 %) | 4 (36.4 %) | 7 (63.6 %) | 4 (36.3 %) | 0 | 0 | 7 (63.6 %) |

| International Institute of Information Technology Hyderabad | 10 (0.9 %) | 7 (70 %) | 3 (30 %) | 9 (90 %) | 1 (10 %) | 0 | 0 |

| TOTAL | 381 | 115 | 82 | 116 | 68 | ||

| 136 (35.7 %) | 245 (64.3 %) |

-

Source: The authors with data from SciVal (2022) and SJR (2021).

Researchers affiliated with Indian institutions published 319 of the country’s 1,015 articles in Q1 journals (31.4 % of their research output in Communication). In the remaining quartiles, the breakdown is as follows: 248 pieces (24.4 %) in Q2, 296 papers (29.2 %) in Q3, and 152 texts (14.9 %) in Q4. There is a considerable variation in the performance of Indian universities across the SJR quartiles. For instance, the International Institute of Information Technology Hyderabad stands out, with 90 % of its articles in Q1 journals. Conversely, three of the top 20 universities (Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Guru Gobind Singh Indraprastha University, and Chandigarh University) did not publish any articles in the highest-level journals. Interestingly, Amity University Noida, the Indian institution with the highest number of publications in SJR-indexed journals, primarily focused its publications in the Q3 stratum.

4.2 BRICS interinstitutional collaborations

This topic analyses whether and to what extent the top 20 most productive institutions in Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa have established partnerships to publish articles in SJR-indexed Communication journals. At this point, we want to make clear that for this variable, the cumulative performance of the universities under investigation may not align with the total number of articles attributed to the country. More precisely, if the University of São Paulo (Brazil) publishes a paper in collaboration with both Zhejiang University (China) and Amity University Noida (India), this would be counted as two distinct partnerships. The same occurs in the case of partnerships established between universities within the same country.

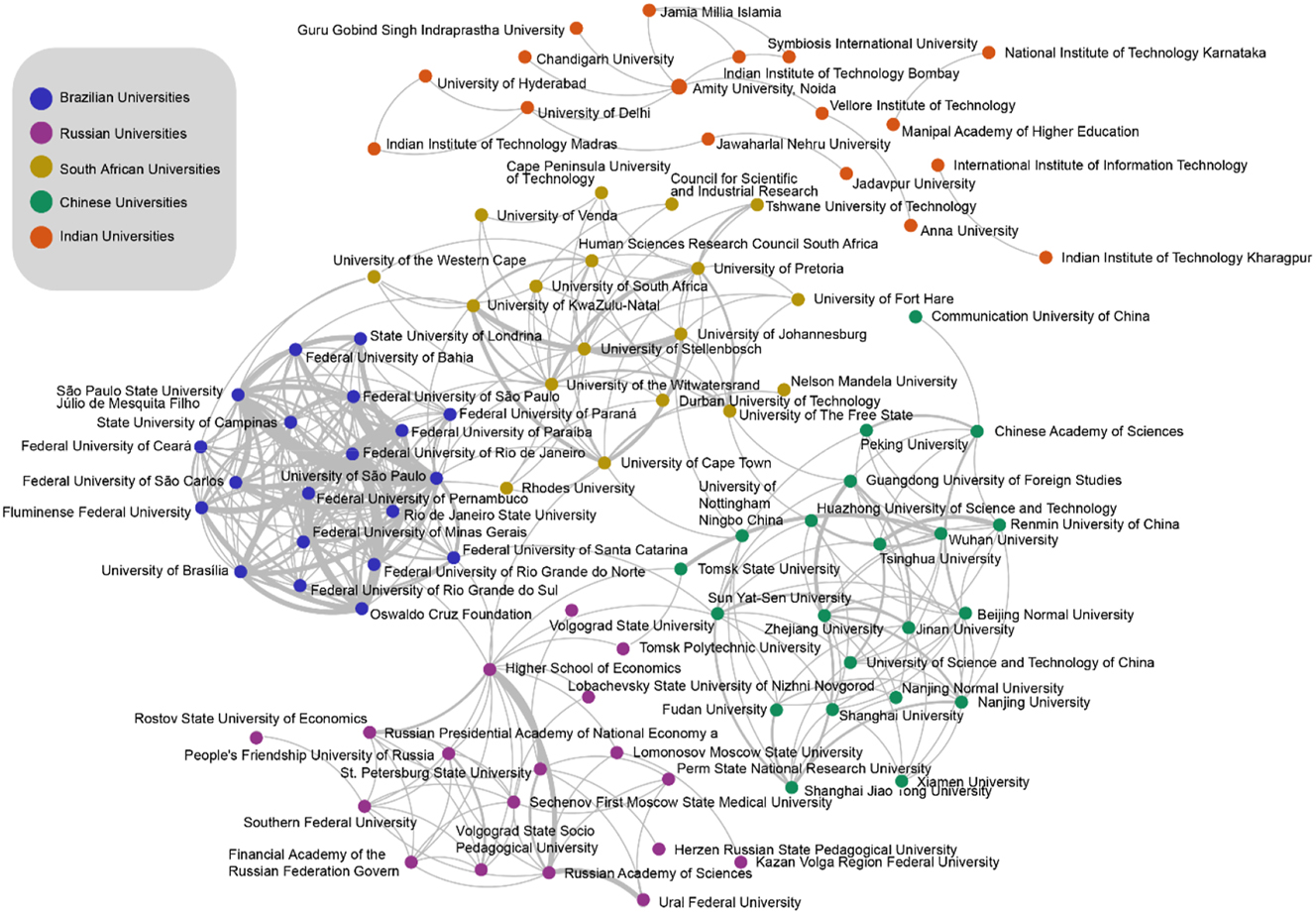

According to Figure 1, international collaborations exclusively among BRICS institutions are relatively rare. South Africa tops the list – despite only registering 15 partnerships. The country’s highlights are the collaborations with Brazil, with nine occurrences. There were also five partnerships with Chinese institutions and one with a Russian university. The University of Cape Town has cooperated with organizations from three BRICS countries: the University of São Paulo, the University of Nottingham Ningbo China, and the Higher School of Economics. In turn, the University of The Free State concentrated its joint work with China: two productions with the Guangdong University of Foreign Studies and one with the Huazhong University of Science and Technology.

Collaborations among the leading universities based in BRICS countries. Source: The authors with data from SciVal (2022).

Brazilian universities have collaborated with institutions from other BRICS countries on 14 occasions – nine with South Africa, four with Russia, and one with China. The University of São Paulo (USP) and the Federal University of Santa Catarina (UFSC) lead the partnerships. The USP co-authored papers with three South African universities (the University of Cape Town, the University of the Witwatersrand, University of KwaZulu-Natal). In turn, the UFSC published in collaboration with a Chinese institution (Sun Yat-Sen University) and had two more works with the Russia-based Higher School of Economics.

Chinese institutions participated in 13 collaborations, with Russia as the leading partner in this case, with seven articles. The co-authorships between Wuhan University and Tomsk State University stand out, with six publications. China also recorded collaborations with South Africa (five pieces) and Brazil (one work).

Russia took part in 12 collaborations: seven with China, four with Brazil, and one with South Africa. Only two Russian universities were involved in such intra-BRICS partnerships: Tomsk State University (six works with Wuhan University, as said before) and the Higher School of Economics (two articles with the Federal University of Minas Gerais; another two with the Federal University of Santa Catarina; one with Sun Yat-Sen University; and one more with the University of Cape Town).

India showed the most significant isolation, with no recorded collaborations between its leading universities and the top 20 institutions in other BRICS countries.

As Figure 1 shows, Brazil outperformed its BRICS partners in terms of domestic collaborations. Over a decade, the 20 Brazilian institutions that published the most in SJR journals formed 490 partnerships with in-country institutions. Notably, the University of São Paulo and the São Paulo State University Júlio de Mesquita Filho took the lead, jointly contributing to 22 publications. The Federal University of Rio de Janeiro and the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation collaborated on 18 jointly authored articles.

China established 113 domestic collaborations when it comes to its 20 top institutions, with five involving Zhejiang University and Guangdong University of Foreign Studies, and five more between Tsinghua University and Renmin University of China.

South Africa registered 101 partnerships among its 20 leading universities, including collaborations between the University of Johannesburg and the University of KwaZulu-Natal (nine articles), the University of Johannesburg and the University of Cape Town (six articles), and the University of Cape Town and University of KwaZulu-Natal (six articles).

In contrast, Russia had 79 publications resulting from domestic collaborations. The Higher School of Economics and St. Petersburg State University established the most frequent partnerships, which yielded eight articles. Likewise, the Russian Academy of Sciences and the Ural Federal University produced eight papers together. The Higher School of Economics and the Russian Academy of Sciences had seven joint pieces. Lastly, India presented a striking scarcity of co-authorships even among its own universities, with only 16 works resulting from domestic cooperation.

5 Discussion and conclusions

Considering that authors and institutions from the Global South face unique challenges when it comes to publishing in top-ranked journals, our research relied on data from the SciVal and SJR platforms to examine the publication trends of BRICS-based universities. More specifically, our study investigated the performance of the top 20 most prolific institutions in Communication and Media Studies in each BRICS country during the timeframe spanning 2012–2021.

Our findings revealed that South Africa, Russia, and Brazil had the highest concentration of academic production within a select few universities – more precisely, the University of Johannesburg (contributing to 19.2 % of total South African publications), the Higher School of Economics (associated with 17 % of all Russian papers), and the University of São Paulo (participating in 11.2 % of Brazilian documents) stood out. Conversely, the 20 most prolific universities in India and China do not account for even 5 % of their respective articles, suggesting a more balanced production in Communication across academic institutions. This finding aligns with the conclusions drawn by Fan et al. (2022) in their analysis of partnerships among the leading BRICS institutions, indicating that the higher education systems in Brazil, South Africa, and Russia remain “significantly unbalanced.”

The disparities between the most and least productive universities can be attributed to a combination of factors. In the case of Brazil, the top five universities excelling in this regard are all located in the Southeast region, precisely the country’s most economically affluent region (Chaimovich and Pedrosa 2021). Conversely, the North Region of Brazil has no institutions among the top 20. Truth be told, the Brazilian government has allocated resources to support projects from less economically developed regions (Brazilian Congress 2019). However, the outcomes have been modest, pointing out the need to design more ambitious policies.

In addition, we must look at the impact of funding policies on the research performance of academic institutions. As Gokhberg and Kuznetsova (2021) discussed, Russia-based universities and researchers frequently encounter barriers that hinder their participation in international funding programs, posing challenges to their research productivity. On the other hand, South Africa is a notable outlier within the African continent, accounting for a remarkable 87 % of all papers from the continent published in Global North journals (Demeter 2020) – despite experiencing only modest growth in research investments over the past decade (Schneegans et al. 2021). Similarly, India has witnessed a decline in the involvement of the government sector in research and development, while private entities are taking on a prominent role in the country’s innovation landscape (Mani 2021).

The contrast among BRICS countries becomes more evident when we look at China’s performance. Although public investment is the primary agent for promoting science in that country, China has implemented a range of strategies that foster international partnerships with Western academic communities – including sending Chinese scholars for training at top-level international universities, in addition to offering competitive salaries and favorable working conditions (Asheulova and Dushina 2014). Furthermore, high-impact journals have been recommended as the prime target for China-based researchers, and additional bonuses are provided for publishing in high-ranking publications (Nature 2017). Consequently, such a country has significantly bolstered its presence in the upper strata of the SJR-ranking listing of Communication journals.

If, on the one hand, domestic-only collaborations and concentration of top universities arise as a result of under-resourced institutions in the Global South, on the other, internal variables must be considered to interpret the results and implications for administrative support for higher education. For example, China’s higher presence in Q1 journals is also due to its academic promotion criteria – what has been called a “monetary reward system of science” (Quan et al. 2017).

At the same time, we noticed that some of the most prolific universities listed in our findings are not necessarily those traditionally recognized as the strongest in their respective national settings. For example, in the Brazilian case, the institution that presents the highest percentage of papers published in Q1 journals is the Federal University of Paraná – which started its Ph.D. program only in 2018. We need to understand which factors contribute to the rise of new players in academic production and collaboration. It is crucial to grasp to what extent the consolidation of international partnerships results from a collective effort or whether it is restricted to the individual actions of a few scholars interested in expanding their international circulation.

If, as Demeter (2020) emphasizes, academic institutions have a crucial role in forming the symbolic capital that supports the global system of knowledge production, the power dynamics established on a worldwide scale – namely, the disparities between institutions in the Global North and South – tend to replicate themselves nationally, that is, within each scientific community. For instance, highly productive researchers often gravitate toward positions at prestigious universities, thereby perpetuating a cyclical pattern of funding and publication concentrated within a select group of institutions deemed “authorized” to speak on behalf of their respective countries.

Furthermore, establishing transnational partnerships among universities in the Global South brings the opportunity to improve theoretical-methodological approaches and share structures that might be available in one country but not another. In fact, teaming up with BRICS scholars has the potential to facilitate the collection and processing of extensive amounts of data – addressing the preference of several top-ranked journals for papers providing multi-case, comparative studies (Goyanes 2020). Thus, the circulation of knowledge produced “from the margins” (Alahmed 2020; Dutta and Pal 2020; Albuquerque 2023) in highly prestigious journals depends on the ambition of academic agreements signed by actors beyond the Western World.

However, even though such collaborations have been mutually beneficial to the partnering institutions, our results indicate that such ties are still incipient, which demands the formulation of Science and Technology policies that also include Human and Social Sciences. That is, interinstitutional collaborations remain relatively rare, even among the most productive universities in each BRICS country. The exception to this trend is also found in Chinese academic institutions, which have expanded their network due to the increasing availability of resources (Demeter 2019a; Demeter et al. 2023) – although they often lean toward forming partnerships with universities outside the BRICS bloc. These results are in line with the findings of Finardi (2015): when studying different areas of knowledge, the researcher did not find a “BRICS effect” in terms of collaboration among the five partners.

Communication researchers based in countries in the Global South face two other challenges to participate in the most prestigious circuits of knowledge production. Firstly, unlike what happens in areas such as Physics or Mathematics, studies in Communication and other Human Sciences are based on language itself (Albuquerque 2023; Demeter 2019a). That is, the authors’ ability to present and defend ideas is more time-consuming for scholars whose mother tongue is not English. Second, as Monteiro and Hirano (2020) highlighted, Social and Human Sciences tend to occupy a peripheral place nationally and internationally regarding funding. It is as if Communication researchers based in the Global South were part of a “periphery of the periphery.”

After all, we consider that the demand for “de-Westernization” goes beyond a mere plea for increased numerical representation. The exclusion of perspectives or phenomena that outline the intellectual landscape of developing regions hinders the progress of knowledge production itself. Moreover, it neglects that purportedly universal definitions and categories often fall short in explaining phenomena that transcend the specific contexts in which they originated (Wasserman 2018). It is essential that researchers from the Global South propose and adopt autonomous strategies to prevent the concept of de-Westernization itself from being incorporated into mainstream research merely as a “niche of studies” and not as a cosmopolitan research practice that allows the encounter among different intellectual traditions.

This study comes with limitations. First, this study only demonstrates BRICS’s presence in elite journals, not their impact on the international academic community. Moreover, we cannot generalize our findings to all academic communities in developing nations as the BRICS members are better characterized as semi-peripheral rather than peripheral countries. Lastly, we should not overlook the importance of regional publishing circuits in these countries (Oliveira et al. 2021). Nevertheless, this paper offers a valuable perspective that encourages the development of strategies for integrating scientists and institutions from the Global South into circuits with increased international visibility.

Future research must compare the strategies adopted by different countries in terms of academic circulation and intellectual influence. Another possible research stream refers to investigating the tension between “writing about” and “writing in partnership with” Global South countries. It is true that we now have an increasing number of Western-based journals focusing specifically on “peripheral” countries, such as the “Chinese Journal of Communication,” “African Journalism Studies,” “Global Media and China,” “Journal of African Media Studies,” and the “Russian Journal of Communication.” However, it is crucial to understand if and to what extent the interest in the Global South reinforces a patronizing approach when it comes to articles circulating in prestigious settings.

Funding source: Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior

Award Identifier / Grant number: 001

Funding source: Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico

Award Identifier / Grant number: 310724/2020-1, 406504/2022-9

Top-20 Brazilian universities concerning the number of publications and the SJR quartiles of their journal articles. Source: The authors with data from SciVal (2022) and SJR (2021).

Top-20 Russian universities concerning the number of publications and the SJR quartiles of their journal articles. Source: The authors with data from SciVal (2022) and SJR (2021).

Top-20 Indian universities concerning the number of publications and the SJR quartiles of their journal articles. Source: The authors with data from SciVal (2022) and SJR (2021).

Top-20 Chinese universities concerning the number of publications and the SJR quartiles of their journal articles. Source: The authors with data from SciVal (2022) and SJR (2021).

Top-20 South African universities concerning the number of publications and the SJR quartiles of their journal articles. Source: The authors with data from SciVal (2022) and SJR (2021).

BRICS-based SJR journals per quartile as of 2021.

| Country/number of SJR journals | SJR journals from each country | SJR quartile |

|---|---|---|

| Brazil (10) | Interface: Communication, Health, Education | Q2 |

| Transinformação | Q2 | |

| Brazilian Journalism Research | Q3 | |

| Perspectivas em Ciência da Informação | Q3 | |

| Informação & Sociedade | Q3 | |

| Texto Livre | Q3 | |

| Comunicação, Mídia e Consumo | Q4 | |

| Caracol | Q4 | |

| Discursos Fotográficos | Q4 | |

| Latin-American Journal of Discourse Studies | Q4 | |

| Russia (6) | Tekst, Kniga, Knigoizdaniye | Q3 |

| Black Camera | Q3 | |

| Imagologiya i Komparativistika | Q3 | |

| Voprosy Onomastiki | Q3 | |

| World of Media | Q4 | |

| Vestnik Moskovskogo Universiteta. Seriya 10. Zhurnalistika | Q4 | |

| India (2) | Asia Pacific Media Educator | Q3 |

| Journal of Content, Community, and Communication | Q3 | |

| South Africa (2) | South African Journal of Communication Disorders | Q2 |

| Communitas | Q4 | |

| China (1) | Digital Communications and Networks | Q1 |

| TOTAL: 21 |

-

Source: The authors with data from SJR (2021).

Journals by SJR quartile per country (including the BRICS bloc) as of 2021.

| Country/number of SJR journals | SJR journals from each country | SJR quartile |

|---|---|---|

| United Kingdom (159) | Digital Journalism | Q1 |

| Political Communication | Q1 | |

| New Media and Society | Q1 | |

| Applied Linguistics | Q1 | |

| Communication Monographs | Q1 | |

| Public Opinion Quarterly | Q1 | |

| Big Data and Society | Q1 | |

| Information Communication and Society | Q1 | |

| Journal of Interactive Advertising | Q1 | |

| Social Media and Society | Q1 | |

| Journalism | Q1 | |

| Journalism Studies | Q1 | |

| European Journal of Communication | Q1 | |

| International Journal of Advertising | Q1 | |

| Telematics and Informatics | Q1 | |

| Internet Research | Q1 | |

| Media, Culture and Society | Q1 | |

| Mass Communication and Society | Q1 | |

| Discourse Studies | Q1 | |

| Journal of Advertising Research | Q1 | |

| Group Processes and Intergroup Relations | Q1 | |

| Journalism Practice | Q1 | |

| Technology, Pedagogy and Education | Q1 | |

| Health Communication | Q1 | |

| Journal of Professional Capital and Community | Q1 | |

| Communication and Sport | Q1 | |

| Journal of Broadcasting and Electronic Media | Q1 | |

| Journal of Media Business Studies | Q1 | |

| Journal of Communication Management | Q1 | |

| Journal of Social and Personal Relationships | Q1 | |

| Journal of Applied Communication Research | Q1 | |

| Chinese Journal of Communication | Q1 | |

| Public Understanding of Science | Q1 | |

| Language and Communication | Q1 | |

| Journal of Health Communication | Q1 | |

| Discourse Processes | Q1 | |

| JMM International Journal on Media Management | Q1 | |

| Journal of Interactive Media in Education | Q1 | |

| Feminist Media Studies | Q1 | |

| Javnost | Q1 | |

| International Communication Gazette | Q1 | |

| International Journal of Science Education, Part B: Communication and Public Engagement | Q1 | |

| Crime, Media, Culture | Q1 | |

| Communication Education | Q1 | |

| Popular Communication | Q1 | |

| Online Journal of Communication and Media Technologies | Q1 | |

| Discourse and Society | Q1 | |

| Educational Media International | Q1 | |

| Journal of Children and Media | Q1 | |

| Social Semiotics | Q1 | |

| Discourse and Communication | Q1 | |

| Communication Research Reports | Q1 | |

| Communication Reports | Q1 | |

| Visitor Studies | Q1 | |

| Critical Studies in Media Communication | Q2 | |

| Communication Research and Practice | Q2 | |

| Rhetoric Society Quarterly | Q2 | |

| Communication Studies | Q2 | |

| African Journalism Studies | Q2 | |

| Cultural Trends | Q2 | |

| International Journal of Conflict Management | Q2 | |

| Network Science | Q2 | |

| International Journal of Listening | Q2 | |

| Language and Intercultural Communication | Q2 | |

| Women’s Studies in Communication | Q2 | |

| Senses and Society | Q2 | |

| Media, War and Conflict | Q2 | |

| Western Journal of Communication | Q2 | |

| Journalism and Mass Communication Educator | Q2 | |

| Journal of Applied Journalism and Media Studies | Q2 | |

| Critical Studies in Television | Q2 | |

| Communication Quarterly | Q2 | |

| International Journal of Sport Communication | Q2 | |

| Information and Communications Technology Law | Q2 | |

| International Journal of Web Based Communities | Q2 | |

| Visual Communication | Q2 | |

| Global Media and China | Q2 | |

| Journal of Multicultural Discourses | Q2 | |

| Journal of Intercultural Communication Research | Q2 | |

| Argumentation and Advocacy | Q2 | |

| Journal of Media Ethics: Exploring Questions of Media Morality | Q2 | |

| Journal of Information, Communication and Ethics in Society | Q2 | |

| Southern Communication Journal, The | Q2 | |

| Communication Review | Q2 | |

| Howard Journal of Communications | Q2 | |

| Translator | Q2 | |

| Creative Industries Journal | Q2 | |

| East Asian Pragmatics | Q2 | |

| Studies in Documentary Film | Q2 | |

| Global Media and Communication | Q2 | |

| Journal of Visual Literacy | Q2 | |

| First Amendment Studies | Q2 | |

| Journal of Creative Communications | Q2 | |

| International Journal of Performance Arts and Digital Media | Q2 | |

| Journal of Digital Media and Policy | Q2 | |

| Australian Journalism Review | Q2 | |

| Art, Design and Communication in Higher Education | Q2 | |

| Radio Journal | Q2 | |

| Communication Teacher | Q2 | |

| Visual Communication Quarterly | Q2 | |

| Atlantic Journal of Communication | Q2 | |

| Journal of Communication in Healthcare | Q2 | |

| Journal of International Communication | Q2 | |

| Text and Performance Quarterly | Q3 | |

| Journal of Alternative and Community Media | Q3 | |

| Russian Journal of Communication | Q3 | |

| Journal of African Media Studies | Q3 | |

| Critical Arts | Q3 | |

| Archives and Manuscripts | Q3 | |

| Journal of British Cinema and Television | Q3 | |

| Quarterly Review of Film and Video | Q3 | |

| Journal of Brand Strategy | Q3 | |

| American Journalism | Q3 | |

| Journal of Visual Culture | Q3 | |

| Communicatio | Q3 | |

| French Screen Studies | Q3 | |

| Studies in European Cinema | Q3 | |

| Journal of Digital and Social Media Marketing | Q3 | |

| Journal of Media Law | Q3 | |

| Westminster Papers in Communication and Culture | Q3 | |

| International Journal of Media and Cultural Politics | Q3 | |

| Qualitative Research Reports in Communication | Q3 | |

| Catalan Journal of Communication and Cultural Studies | Q3 | |

| Media History | Q3 | |

| Journal of Arab and Muslim Media Research | Q3 | |

| Transnational Screens | Q3 | |

| Transnational Marketing Journal | Q3 | |

| Journal of Italian Cinema and Media Studies | Q3 | |

| Journal of Popular Television | Q3 | |

| Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television | Q4 | |

| Screen | Q4 | |

| Studies in Australasian Cinema | Q4 | |

| Empedocles | Q4 | |

| Science Fiction Film and Television | Q4 | |

| Studies in Eastern European Cinema | Q4 | |

| Journal of Greek Media and Culture | Q4 | |

| New Review of Film and Television Studies | Q4 | |

| Film-Philosophy | Q4 | |

| Journal of Chinese Cinemas | Q4 | |

| International Journal of Advanced Media and Communication | Q4 | |

| Journal of Japanese and Korean Cinema | Q4 | |

| Photographies | Q4 | |

| New Cinemas | Q4 | |

| Publishing History | Q4 | |

| Asian Cinema | Q4 | |

| Studies in South Asian Film and Media | Q4 | |

| International Journal of Work Innovation | Q4 | |

| Journal of African Cinemas | Q4 | |

| Journal of Writing in Creative Practice | Q4 | |

| Music, Sound and the Moving Image | Q4 | |

| Communication Booknotes Quarterly | Q4 | |

| Digital TV Europe | Q4 | |

| Film Fashion and Consumption | Q4 | |

| Studies in Russian and Soviet Cinema | Q4 | |

| Studies in Spanish and Latin American Cinemas | Q4 | |

| Northern Lights | Q4 | |

| Victoriographies | Q4 | |

| Film International | Q4 | |

| Visual Culture in Britain | Q4 | |

| United States (83) | Communication Methods and Measures | Q1 |

| International Journal of Press/Politics | Q1 | |

| Research on Language and Social Interaction | Q1 | |

| Journal of Advertising | Q1 | |

| Journal of Communication | Q1 | |

| Transactions of the Association for Computational Linguistics | Q1 | |

| Communication Research | Q1 | |

| Vehicular Communications | Q1 | |

| Annals of the International Communication Association | Q1 | |

| Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly | Q1 | |

| Media Psychology | Q1 | |

| Human Communication Research | Q1 | |

| Communication Theory | Q1 | |

| International Journal of Strategic Communication | Q1 | |

| Journalism & communication monographs | Q1 | |

| Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking | Q1 | |

| Mobile Media and Communication | Q1 | |

| Convergence | Q1 | |

| Management Communication Quarterly | Q1 | |

| Written Communication | Q1 | |

| Journal of Business and Technical Communication | Q1 | |

| Games and Culture | Q1 | |

| Signs and Society | Q1 | |

| International Journal of Communication | Q1 | |

| Symbolic Interaction | Q1 | |

| Journal of Family Communication | Q1 | |

| Psychology of Popular Media | Q1 | |

| Public Relations Inquiry | Q1 | |

| Asian Journal of Communication | Q1 | |

| Communication, Culture and Critique | Q1 | |

| Learned Publishing | Q1 | |

| Metaphor and Symbol | Q1 | |

| American Speech | Q2 | |

| Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics | Q2 | |

| Negotiation and Conflict Management Research | Q2 | |

| Communication and the Public | Q2 | |

| Quarterly Journal of Speech | Q2 | |

| Technical Communication Quarterly | Q2 | |

| Newspaper Research Journal | Q2 | |

| Journal of International and Intercultural Communication | Q2 | |

| Electronic News | Q2 | |

| Public Culture | Q2 | |

| Technical Communication | Q2 | |

| Journal of Communication Inquiry | Q2 | |

| TESL-EJ | Q2 | |

| International Journal of Digital Multimedia Broadcasting | Q2 | |

| Applied Environmental Education and Communication | Q2 | |

| Communication and Critical/Cultural Studies | Q2 | |

| Tourism, Culture and Communication | Q2 | |

| Scholarly Assessment Reports | Q2 | |

| Cultural Politics | Q2 | |

| Journal of Radio and Audio Media | Q2 | |

| Journal of Mobile Multimedia | Q2 | |

| Publishing Research Quarterly | Q3 | |

| Holocaust Studies | Q3 | |

| Review of Communication | Q3 | |

| Journal of Media Literacy Education | Q3 | |

| International Journal of Information Technology Project Management | Q3 | |

| Journal of Advertising Education | Q3 | |

| Sound Studies | Q3 | |