Abstract

In this article, we explore the question: how do local nonprofits respond to migration crises? We focus on the migration context across Colombia and Venezuela, two countries situated in the Andean region of South America with histories of migratory patterns, and geographies where public goods and services by government are limited, leaving nonprofits often as primary service providers. We explore our research question through the case study of the nonprofit organization Fundación Huellas. The Fundación Huellas case study outlines a local, community-based nonprofit responding to a migration crisis in Medellín, Colombia. While micro-territorial in scope, we posit that the case helps to understand the role(s) of nonprofit organizations in migration crises and demonstrates an important dimension to localization in the provision of public goods and services in such contexts. We find that localization should be explored and understood in Latin America as including the dimension of “acompañamiento” (or accompaniment in English), which can manifest in daily nonprofit practice. We use our case study data to introduce and explain the dimension of “acompañamiento” in localization and migration crises and to call on the field and funders to better recognize and support this orientation in local nonprofit responses.

1 Introduction

People move away from their homelands for multiple reasons. This includes economic and labor considerations; the so-called push/pull theory of migration. Populations are growing in low-income countries and shrinking in high-income countries which creates a push out of low-income countries and a pull toward high-income countries where a workforce is in demand (Garip 2016; Munck 2008). Migration is also a consequence of a desire to escape dangerous situations due to political strife, war, atrocities, and prosecutions. These forms of migration are often considered forced migration (Mingot and de Arimatéia da Cruz 2013). Forced migration is understood as distinct from economic and labor migration, but this division both in theory and practice is diminishing in many settings (Bada and Feldmann 2017; Massey et al. 1993; UNHCR 2022). In Latin America especially, migrants leave home countries for economic and labor reasons often compounded by violence and drug cartel activity (Garip 2016).

As a team of Latin Americanist scholars and practitioners, who study and work in nonprofit organizations, we explore how local nonprofits respond to migration crises. In this article, we focus on the migration context across Colombia and Venezuela, two countries situated in the Andean region of South America with histories of migratory patterns, and geographies where public goods and services by government can be limited, leaving nonprofits often as primary service providers (Appe and Layton 2016; Garkisch, Heidingsfelder, and Beckmann 2017). Colombia has received 2.5 million migrants from Venezuela since 2017 due to the country’s economic hardship and political strife (https://www.crisisgroup.org/). In fact, after Turkey, Colombia hosts the second most absolute number of refugees globally (UNHCR 2022).

We explore our research question through the case study of the nonprofit organization Fundación Huellas. This organization was created to serve local children who were out of school due to forced displacement from Colombian territories that faced violence. This has expanded from serving internally displaced Colombian families to Colombians who are returning from Venezuela and Venezuelan migrants and refugees. Fundación Huellas, legally incorporated in 2007, is located in the outskirts of Medellín, Colombia, a city that has received the second largest number of Venezuelan migrants and refugees after the country’s capital, Bogotá. Medellín hosts almost 10 % of Venezuelans in Colombia, estimated to be 190,000 migrants and refugees (GIFMM 2021; Yu 2022). The case study of Fundación Huellas outlines a local, community-based nonprofit responding to the current migratory crisis in Colombia. While micro-territorial in scope (the organization focuses on two neighboring municipalities in the department of Antioquia outside of Medellín), we posit that the case helps to understand the role(s) of nonprofit organizations in migration crises and demonstrates an important dimension to localization – accompaniment – in the provision of public goods and services in these contexts.

We consider localization to be organizational policies, processes, deliverables and behaviors in development aid that take into account local actors, their perspectives and their knowledge; and that promote ownership of development by local communities. The importance of localization for nonprofit organizations aiding in crises has gotten renewed attention, given the need for local responses during the COVID-19 pandemic (WINGS 2023). Localization as a concept considers local and community input and ownership to be critical to the provision of goods and services. It also suggests that funding can be more effective if directed to local actors. In this paper, we seek to better understand localization in migration crises through accompaniment which we explain in the next section. This objective contrasts with what has often been a focus of migration response and development aid: it has concentrated more on the role of international non-governmental organizations (INGOs) and other Northern actors (van Wessel, Kontinen, and Bawole 2023).

Prior to explaining our case study approach, first the paper briefly addresses nonprofits in migration-affected contexts and the localization discussion in development aid. Second, the background on the empirical setting is provided to situate our case study. Then, we outline our methods and present our findings. We find that localization should be explored and understood in migratory contexts as also including the dimension of “acompañamiento” (or accompaniment in English), which can manifest in daily nonprofit practice while responding to crises. The case study seeks to introduce and explain the dimension of “acompañamiento” in localization and migration crises. We build on studies about nonprofits in migration-affected contexts that have considered accompaniment (e.g. Peralta and Vaitkus 2019; Wilson 2012), calling on the field and funders to better recognize and support this orientation in local nonprofit responses.

2 Nonprofits and Migration

Garkisch, Heidingsfelder, and Beckmann’s (2017) systematic literature review on the role of the nonprofit sector in services related to migration provided a welcomed, comprehensive overview of nonprofit organizations[1] in this important policy area. Their review demonstrated the limited geographic scope in the research about nonprofit organizations and migration and that the topic needs further theoretical development (Garkisch, Heidingsfelder, and Beckmann 2017). In particular, they call on scholars to further research about how nonprofits can perform and serve better in migratory contexts.

The research on immigrant- and migrant-serving nonprofits has grown over the last 20 years. The literature in part centers on how nonprofit organizations respond to the ebbs and flows of migration crises (e.g. Meyer and Simsa 2018; Simsa 2017; Strokosch and Osbornes 2017). It also has captured the support and range of services provided by these nonprofits in destination countries (e.g. Safouane 2017; Van der Leun and Bouter 2015), from basic social services to human rights protection, and how nonprofits manage volunteers in service provision to migrants (Simsa et al. 2018). Furthermore, research has explored specific integration practices (Fernández Guzmán Grassi and Nicole-Berva 2022), the roles of immigrants and migrants as volunteers themselves (Greenspan and Walk forthcoming), and the extent of diversity among immigrant- and migrant-serving nonprofits (e.g. Babis 2016).

We turn to authors who have explored and applied the concept of accompaniment in nonprofits and migration settings. As Peralta and Vaitkus (2019) observe, this is not a new concept, rather it has a rich history in community and development work, especially around health inequities. The concept was brought to the forefront by the work of Paul Farmer and his death in 2022 allowed his contributions to resurface and be reconsidered. Farmer practiced accompaniment in global health through the nongovernmental organization (NGO), Partners In Health, which he co-founded in the late 1980s. Farmer describes accompaniment as the following: “To accompany someone is to go somewhere with him or her … to be present on a journey with a beginning and an end” (Farmer 2011, p. 1). He learned through his work which started in Haiti that “[t]here’s no one-size-fits-all approach, but there are surely basic principles of accompaniment” (Farmer 2011, p. 2). Farmer wanted accompaniment to be the new aid paradigm to achieve the development outcomes that are possible.

While his approach started in the health sector (and in Haiti), he brought it to the orbit of broader development goals, and to other continents and economies, including the U.S. (Farmer 2011). When applied to health inequalities, the model allows a patient to receive care by not having to go to a clinic in, let’s say, an urban center. Rather a patient has what Partners In Health calls a accompagnateur, who provides accompaniment, holistically and locally (Farmer 2006). With the model of accompaniment, he drew on both the need to support local capacity and the need to change how we approach (and fund) health and broader development goals (Farmer 2011). He was cautious about expert knowledge only, explaining, “True accompaniment does not privilege technical expertise above solidarity or compassion or a willingness to tackle what may seem to be insuperable challenges” (2011, p. 8). He noted the challenges to measuring accompaniment, and dismissed this as a reason not to support and fund it (Farmer 2011). In fact, he debated this topic with the largest of donors, and consistently lamented that the lack of funding was always a major issue (Farmer 2006).

To our knowledge, accompaniment has been discussed in the context of migration in the nonprofit literature related to the provision of local language services in the U.S. (Wilson 2012) and immigration documentation in the Dominican Republic (Peralta and Vaitkus 2019). Both studies found the use of the term accompaniment in their data from nonprofit organizations. Wilson (2012) describes “immigrant accompaniment” in the work of U.S. nonprofits as including: “a range of informal services provided to immigrants – client representation, protection, and companionship” (p. 977). Wilson (2012) found that this role in the context of immigration in the U.S. was distinctive to the services provided by nonprofits in comparison to those provided by local governments. Peralta and Vaitkus (2019) found similar patterns. They studied migration in the context of Haitians in the Dominican Republic and the mention of accompaniment was persistent in their qualitative data. They explain that accompaniment: “goes beyond simply pooling resources or providing aid at different points in [service provision]. This role involves being present throughout” the service provision (Peralta and Vaitkus 2019, p. 1326, emphasis added).

In the writing and words of Farmer, accompaniment’s origin is often referenced. It is Latin: ad cum panis and translated to ‘breaking bread together’ (2011, p. 4). It has roots in Catholicism’s liberation theology, a movement prominent in Latin America starting the 1960s which centered on liberating the oppressed with a focus on poverty and social injustices (Farmer 2011). It is perhaps fitting therefore that it was a central theme found in our data about Huellas, a local nonprofit working in the region. And given accompaniment’s focus on local capacity and local orientation, it also is well timed as there is a renewed interest in localization within international development and global philanthropy circles.

3 Localization in Development Aid

Considerations of accompaniment in the work of nonprofits links appropriately to localization. Calls for localization have again emerged due to the perceived ineffectiveness and lack of efficiency in development (Booth and Unsworth 2014; Cabot-Venton and Pongracz 2021; Cernea 1987; Craney and Hudson 2020; Lentfer and Cothran 2017) and evidence of promising local responses during the COVID-19 pandemic (WINGS 2023). Benefits include more resources to projects on the ground (Cabot-Venton and Pongracz 2021), increased community ownership in development projects (https://mcld.org/), and potentially sustained commitment that extends well beyond the presence of external donors and other funders (Abrahams 2022).

Localization re-frames and re-imagines the focus and reliance on Northern actors in development aid. Rather, it considers the challenges to development aid “to be structural and systemic and thus in need of system-level changes rather than small improvements. Such changes would require that Southern CSOs [civil society organizations] be at the centre [sic] and in the lead, rather than playing the role of implementation partners” (van Wessel, Kontinen, and Bawole 2023, p. 2). We have seen several calls for localization often focused on access to funding. Big donor names and initiatives have included the 2016 Grand Bargain (https://interagencystandingcommittee.org/grand-bargain), which promises a still unrealized earmarked 25 % of humanitarian aid going directly to local actors and bilateral government agencies such as USAID promising more locally-led approaches. USAID recently pledged 25 % of its funding going to directly to local partners (up from its current 6 %) (Saldinger 2021).

With these statements, van Wessel, Kontinen, and Bawole (2023) explain, “[m]any donors that provide funding for civil society initiatives emphasize contextualization and local ownership of programmes; however, they continue to support programming by Northern development [civil society organizations] and channel funds through them as ‘fundermediaries’ that pass funds to other actors as a main function (Sriskandarajah 2015), rather than allocating these funds directly to organizations in the Global South” (van Wessel, Kontinen, and Bawole 2023, p. 2). Efforts for a paradigm shift that values localization need to bring to the forefront truly localized initiatives, which might not be part of the traditional international cooperation landscape. Fundación Huellas provides such as case. We present Fundación Huellas as localized civil society action within geographies that face a migration crisis. Like Peralta and Vaitkus’ (2019) research on nonprofit organizations in Dominican Republic’s migration context, Huellas provides a focus on migration outside of North America and Europe. We draw on the case to better understand the components of sustained, local action through the lens of accompaniment in migration crises.

4 Empirical Setting: Migratory Histories to and from Colombia and Venezuela

Here we briefly narrate the migration patterns in both Colombia and Venezuela dating back to the second half of 20th century to the present. While Venezuela migrants dominate the current migration crisis, Colombia and Venezuela have had “intertwined histories” or what the UNHCR (2023a) calls “circular movements between the two countries” (p. 2). Both countries have experienced fluctuations of emigration (migration away) and immigration (migration to) (Barrera 2018). In the case of Colombia, there have also been significant levels of internally displaced people.

Since the 1960s, economic crises and political violence pushed millions of Colombians to internally migrate and/or migrate abroad, looking for better living conditions and escaping from periods of violence (Espacios de Mujer 2023; Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Colombia 2023; Silva and Massey 2015). Internally, Colombia has one of the largest number of displaced populations in the world, at 6.8 million in 2022 (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees UNHCR 2024). Additionally, five million Colombians have emigrated abroad since the 1960s, which is equivalent to more than 10 percent of the current Colombian population (DNP 2017). Many Colombians who left the country live in United States and Spain, as well as Venezuela; in fact, over two-thirds of immigrants in Venezuela in the 1990s were Colombians (Kurmanaev and Medina 2015). However, today migration to Venezuela from Colombia has decreased and since 2015, Colombia has been on the receiving end. In fact, Colombians, who once emigrated to Venezuela, are now returning to Colombia due to the economic and political crisis (Barrera 2018). More than half a million Colombians have returned from Venezuela since 2015 (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees UNHCR 2024).

Venezuela’s current out-migration wave started after the death of Hugo Chávez in 2013, due to the deterioration of economic conditions and the rise of repression, political persecution, and insecurity under his successor’s (Nicolás Maduro) government (Barrera 2018; Freitez, Viso, and Osorio 2021). Today there are more than seven million Venezuelan migrants outside of Venezuela which represent more than 20 % of the country’s population. Venezuelans have mostly migrated to the United States, Spain, and to Colombia and other Latin American countries (ACNUR 2023). The political context pushed both upper-class and poorer Venezuelan to emigrate, in search of work and means to survive. Migratory conditions continued to worsened and new migrants were less educated, had fewer economic resources, and lacked emigration documents such as passports and visas (ACNUR 2023). Consequently, Venezuelan migrants are often forced to take irregular routes to reach destination countries, making them vulnerable to smugglers, traffickers and armed groups and reliant on the informal economy (ACNUR 2023; Van Praag 2019). Irregular migration by land has resulted in Colombia receiving many Venezuelan migrants, estimated to be more than 2.5 million (Alvarado et al. 2018; CNN 2022).

5 Research Approach and Data Collection

Using the case of the nonprofit organization, Fundación Huellas, our qualitative research approach aims to explore migration crises in the region, particularly in areas where public goods and services by government are almost nonexistent. We purposively selected an organization working with vulnerable populations in Medellín, Colombia. We chose a qualitative approach using a case study design (Stake 1995) to understand how a local nonprofit is responding to empirical realities of migration on the ground. The selected nonprofit is thus a theoretically useful case (Miles and Huberman 1994; see also Eisenhardt 1989), following the interpretive case study methodology for selecting cases which seek to maximize what we can learn (Stake 1995).

Fundación Huellas agreed to participate in the research study and one of its founders is part of the present article’s research team. Thus, the research is conducted through an academic-practitioner collaboration. Under the qualitative design, data collection and analysis were often conducted in tandem (Merriam 1998; Stake 1995). Our first mode of data collected was through participant observation and archival documents, which were complemented by key interviews, allowing for triangulation of data sources to derive key findings, namely a greater understanding of accompaniment.

We engaged in deep participatory observation where we took copious notes and had countless observational points. In addition, we did a thorough and systematic analysis of key organizational documents. These reports were situational analyses, project descriptions and program evaluations. The documents date from 2009 and the most recent is a baseline report from 2023. The documents amassed almost 1350 pages of content (see Appendix A for document inventory). The classification of all the participatory observation and archival data was managed in Excel matrices and Word documents. Text was compiled and stored in the original language (Spanish). The data excerpts that are used to illustrate results are translated into English. These data were complemented by eight in-depth interviews with staff, volunteers, and participants. Such organizational and positional labels were not always mutually exclusive, where some participants, for example, were volunteers and at times were provided a stipend for their time or to cover transportation. The interviews were conducted in Spanish. All participation through interviews was done voluntarily and oral consent was received.[2]

We coded the data to examine patterns, the similarities and differences to answer our research question, consistent to case study design and analysis (Corbin and Strauss 2008; Miles and Huberman 1994). We relied an inductive analysis (based on emergent themes) that were broadly related to the response to the migration crisis and conducted deductive analysis specific to what we identified as localization practices (e.g. ownership, participation) (Merriam 1998). The academic-practitioner research team facilitated an exchange of information and communication with research participants about the research progress and welcomed comments and feedback. The following provides more details on the selected organization.

6 Fundación Huellas: Internal Displacement and Forced Migration at its Core

Fundación Huellas began as Escuelita de Tablas in 1998 serving local children who were out of school due to forced displacement from Colombian territories that faced violence (namely, from the territories of Urabá and Chocó). Initially, Escuelita de Tablas was an improvised wooden school with a zinc roof top and a dirt floor. In 2004, La Torre Community Center was constructed with international, local government and private funding sources. Thereafter in 2007 Fundación Huellas was legally incorporated as a local Colombian nonprofit organization.

Fundación Huellas serves two municipalities (Medellín and Bello in the department of Antioquia) that have absorbed large quantities of internally displaced populations from Colombia as well as more recently Colombians returning from Venezuela and Venezuelan migrants and refugees. The La Torre in the Santo Domingo Savio II neighborhood in Medellín now with more than 40 years of operation as a neighborhood has simple infrastructure for basic services (water, sanitation), stable housing (cement, brick, and adobe), functioning schools, and some health services. Huellas’ services have been extended to the entire neighborhood. The Granizal neighborhood in the municipality of Bello, ranges from 10 and 20 years old, and is considered still an informal settlement, with limited basic services. Working in this area since 2010, Huellas reports that health issues are of particular concern given the lack of an overarching healthcare system and the absence of sewage and drinking water systems, which leads to challenges with several (preventable) diseases (DR16, 2020, p. 1).

As a receiving city of displaced and migrant populations, the Medellín hillsides are transient, with some families migrating to the neighborhood and using them as a starting point. They end up moving on, migrating into Medellín’s city center or other Colombian territories for more economic and labor opportunities. This has become common for both displaced Colombians and Venezuelan migrants. Just as common, there are cases where families arrive at these neighborhoods and settle for the long term (Huellas staff person, personal communication, May 2023).

By 2015, of the participants of the different projects and services provided by Fundación Huellas, “76.6 % [… had] experienced some type of displacement” (DR6, 2015, p. 2), a figure that has been consistent since. In 2019 …

… 78.5 % of the families [stated] that they had been victims of some victimizing event … such as displacement, homicides, massacres, forced abandonment of land, land dispossession, kidnapping, forced disappearance, and confrontations … that forced families to leave their places of origin (DR14, 2019, p. 2).

The arrival and reception of Venezuelan families in the hillsides of Medellín started to heighten in 2017 and 2018. From 2019, Venezuelans were formally being documented in Fundación Huellas reporting. Due to this growth, Huellas in 2022 broadened its understanding of who it serves and formally extended its mission to include migrant populations, such as those from Venezuela. Since 2022, the organization’s programs:

focus on rights, gender, functional diversity, intercultural and differential approaches, of children, adolescents, youth, adult women and men, older adults, and their families, in situations of vulnerability, poverty, displacement, migration and/or different conditions of inequality and violence (DR20, 2022, p. 1, emphasis added).

Undoubtedly, migrants seek out Huellas’ services. One volunteer notes that it is not uncommon to find community newcomers stopping by to see how the local nonprofit might be able to help. During one visit by the research team, when we arrived, there was a woman reading the calendar posted on the Huellas’ door. A Huellas staff member stopped to talk to her as we approached the building. It was clear that she was not from Medellín, and the hunch was that she was Venezuelan based on her accent. She was sent by the local school to consider Huellas’ afternoon programming for her son. She was hoping he could attend the afternoon sessions to help “burn off some of his energy” (neighborhood woman, personal communication, May 2023). She was welcomed, given information about the schedule, and encouraged to bring her son.

Like in many migration crises around the world, Venezuelan migrants arrive to Colombia in an irregular manner, which means that they do not have work permits and are exposed to situations of extreme needs and labor exploitation; migrants rarely have access to formal employment. For children, the lack of sufficient documentation is a barrier to entering into the school system. Likewise, most families are unable to access health services. All these elements together with the fact that, for the sake of family survival, most migrant parents leave their homes to work, leaving many children unsupervised, interacting and developing, day after day, on the street (DR16, 2020). Due to these realities, Huellas has adopted and developed a comprehensive model of accompaniment in its work.

7 A Model of Acompañamiento

While localization is receiving attention in development aid, it is not a word used and managed by Huellas in the context of its work. Rather, we find through our data analysis that the term acompañamiento captures values related to localization and is more relevant given Huellas’ mission. Indeed, acompañamiento (translated as accompaniment in English) alludes ownership and participation; and furthermore, regular and sustained relationships, “throughout” the service provision (Peralta and Vaitkus 2019, p. 1326). Based on our data, we present a more detailed elaboration of accompaniment in the context of a migration crisis. For Fundación Huellas, accompaniment is both an implicit practice that takes shape in its work, and explicitly woven into its approach. For example, it is emphasized in report titles such as the “Ecomanatiales Accompaniment Report” (DR5, 2015) or in project names such as “Academic accompaniment for children and youth of Medellín in times of Covid-19” (DR21, 2020).

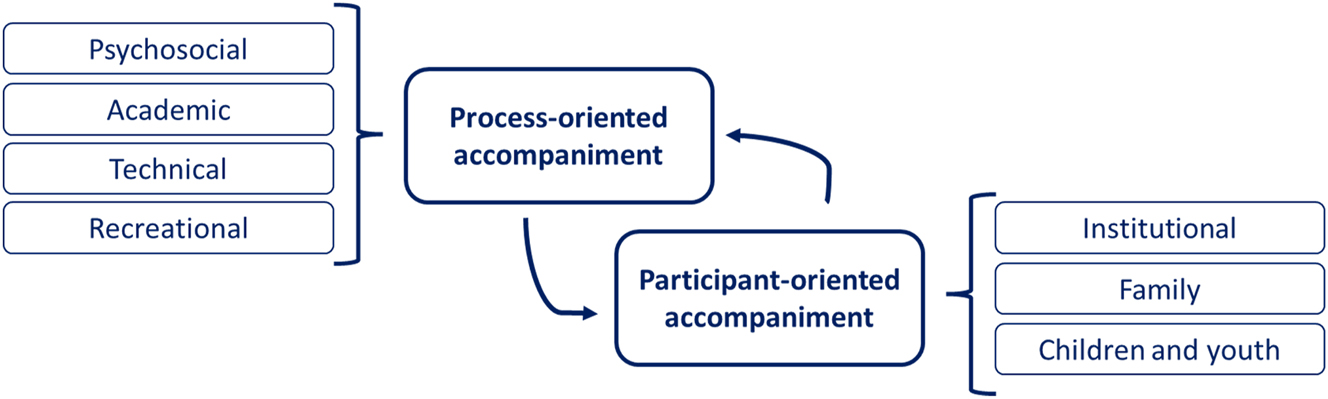

Huellas practices process-oriented accompaniment which includes four types of accompaniment: psychosocial, academic, technical and recreational. In addition, it considers participant-oriented accompaniment, which includes three types of support, individual and/or collective: institutional, family, and children and youth support. These types of accompaniment manifest in project proposals, designs and evaluations and became very present in our observational and interview data. Examples of accompaniment appear in the stories told by staff, volunteers and participants. The components of accompaniment often happen simultaneously (that is, process-oriented and participant-oriented accompaniment are often fulfilled concurrently) (see Figure 1, for further text examples from our data see Appendix B).

Types of acompañamiento in the Fundación Huellas.

8 Process-Oriented Accompaniment

Process-oriented accompaniment is related to the intention to transform and empower participants through actions and projects over time. Huellas is characterized as having a constant presence in the localities where it works. It strives to maintain this presence, with volunteer action and university internships, even in periods of funding constraints. The statutes of the Huellas state that its primary purpose is “to generate processes of social, productive, sports-recreational, educational, technological, artistic … [and] community development” (DR20, 2022, p. 1, emphasis added).

8.1 Psychosocial Accompaniment

Much of the programming at Huellas includes a psychosocial dimension. For Huellas this means providing psychotherapy and mental health promotion through personalized (clinical) spaces on demand, and collective (community) spaces that complement other types of accompaniment. Huellas’s Child Protection Policy demonstrates this orientation. It was created in part by Ana,[3] who we spoke to at length about her experience at Huellas. Ana grew up in the neighborhood and then studied to be a psychologist. When her studies were complete, she became a volunteer at Huellas, and her first task – with other local youth – was to draft the organizational policy for child protection, an exemplar of process-oriented accompaniment.

Huellas staff explained that the participation by Ana and other young people brought important familiarity to the local conditions and the psychosocial needs of the neighborhoods. Their participation drew attention to identifying and understanding the risks faced by youth in particular. Based on their own experiences, they were able to integrate risk identification in the policy for Huellas staff members to consider when working with children and youth. Ana described and contextualized the risks for youth that are especially pronounced, including drug use, reclusion, begging, sexual exploitation, and child labor. Ana’s experiences and the local knowledge contributed to the Child Protection Policy Guidance Document (DR11, 2019) and in fact, it captures several of the types of accompaniment from Figure 1. As written, Huellas’s Child Protection Policy (2019) states:

Fundación Huellas is an organization that works in the search for better conditions and opportunities for children and adolescents … [in the Santo Domingo II neighborhood, La Torre sector, in the city of Medellin and the Granizal neighborhood in the municipality of Bello]. Its main purpose is to generate processes of social inclusion and informal training for the formation in values with a focus on rights for this population, victims of displacement and those facing situations of impoverishment (DR11, 2019, p. 4).

Soon after the completion of the Child Protection Policy, Ana was hired onto a project, which uses her expertise as a psychologist. The project addresses mental health among children and youth. Here she integrates process-oriented accompaniment (namely, psychosocial) with participant-oriented support to children and youth.

8.2 Academic, Technical, and Recreational Accompaniment

For Fundación Huellas, accompaniment is a daily practice that respects the realities and dynamics of local participants (notice, Huellas does not use the term beneficiaries[4]) and their communities. Academic support is aimed at the development of basic literacy, logical-mathematical problem solving, and second language skills, all of which allow children to level up and enhance their formal school learning. With the disruption due to migration and as a consequence of the school virtualization during the Covid-19 pandemic, many children and youth have a delay in their learning process or are in a condition of ‘extra-age’ (that is, they are two years older for the level of schooling required, e.g. a 10 year old child who does not know how to read and write and is in level or grade 3 of primary school, when they should be in level/grade 5). Programs with academic accompaniment by Huellas have served hundreds of neighborhood youth and children over the years to close this gap.

Process-oriented accompaniment also includes technical and recreational accompaniment. Examples of technical accompaniment are those provided to women and families for the development of skills (e.g. food production, tailoring, food preparation, handicrafts, among others). For example, during our data collection visits, Huellas was developing the project “The Promotion of Rights and Economic Autonomy for Women” (DR22, 2023). The project included activities to accompany women in advancing informal productive initiatives and small startups that would help to generate resources for families. This type of process-oriented accompaniment seeks to promote economic autonomy and provide for families’ basic needs. The recreational accompaniment also contributes to Huellas mission. This type of accompaniment in the nonprofit’s programs helps to develop fine motor skills, stimulates the motivation of the participants, and promotes better relationships among them. It is achieved through the implementation of play, the promotion of physical activity, and the values of coexistence (respect, listening, collaboration, solidarity, among others). This type of accompaniment is integrated with the other types. Consistently, all staff and volunteers shared with us and it is well documented in organizational reports that play methodologies have accompanied the work of the Huellas since its origin (e.g. DR1, 2009; DR8, 2017).

9 Participant-Oriented Accompaniment

The participant-oriented accompaniment centers on the explicit population groups for which Huellas directs its mission. These types of accompaniment harmonizes with the process-oriented accompaniment outlined above (see Figure 1).

9.1 Institutional Accompaniment

Institutional accompaniment emphasizes the different experiences, projects and services offered by the organization, with “active and participatory methodologies that give recognition of all [perspectives]” (DR1, 2009, p. 14). The practice is “energized” by volunteers, practitioners, and professionals, and directed towards boys, girls, young people, women and the community at large. In other words, in fact, accompaniment for Huellas is the “conversation between different actors [seeking solutions to] achieve transformations of [their] realities” (DR9, 2018, p. 15).

According to Huellas leadership, the fulfillment of the mission of the organization has been possible thanks to the strength of local voluntary action. This has included community volunteers and university students conducting professional internships. Many of the students, once they become professionals, are hired as technical and psychological staff (like Ana above) when Huellas projects have the funding available. Such hiring practices underline participant-oriented accompaniment. These voluntary and professional trajectories in Huellas have transformed the reality of many of the participants’ upbringing. For example, Huellas found that in 2018,

50 % of the daily volunteers of the Foundation Huellas have as children participated in many of the processes or services offered by the organization (they studied at the “Escuelita de Tablas”, participated in children’s [programming], the toy library, sports festivals …), … once they had the opportunity to go to school and university, they have returned to the organization with the intention of giving back what they received. (DR9, 2018, p. 9)

And in return, Huellas as an organization and institutionally accompanies the participants through these stages of their personal, academic and professional lives.

Indeed, Huellas’s current staff all have years of experience with the organization: many were raised in and from the neighborhood, participated in Huellas as children and youth as mentioned and/or conducted their internships with the nonprofit and have stayed. In addition to Ana (discussed above), Lina is from the neighborhood and had participated in Huellas’ youth groups in her adolescence. She then volunteered to help with organizational administration, where she received a small stipend to help her with her transportation costs. Currently she is a staff member to support women and children’s groups. Another example is Alba, who conducted her internship at Huellas working on a program about child sexual abuse prevention. She then became a volunteer and has cycled in and out of volunteer and paid staff positions, depending on available funding.

Indeed, in its commitment to accompaniment, as demonstrated with the process of The Child Protection Policy above, Fundación Huellas values local knowledge and local capacity. Another example is one woman who has participated in Huellas programs for 10 years named Dora. She migrated to the hillside from another region in Colombia about 20 years ago. In 2013, there was a Fundación Huellas project in the neighborhood about home gardens. Initially she was not interested. She never considered herself to be someone who would tend to the land or grow things. But there she was 30 years old with six kids, a husband, and the only other thing she had was a small plot of land. One week she heard about the project and somehow the next week she was meeting directly with Huellas, and since then she has been a loyal participant. Dora smiles widely and states 10 years later, “I love my garden” and “I say to people, I have now seven kids, a husband, and my garden” (participant, personal communication, May 2023). It has allowed her family to never need food, nor do they lack nutrition. Since then, she has become a volunteer and promoter for Huellas and home gardens. She has volunteered, with a stipend, with Huellas to support other families in cultivation and nutrition. Indeed, she has practiced accompaniment and assumed a role of what Farmer’s work calls an accompagnateur with her neighbors and newcomers to the neighborhood.

9.2 Family, Children and Youth Accompaniment

Family accompaniment refers to actions, projects and processes targeted at families. During our research we found this type of accompaniment by Huellas is directed mainly to women which in turn supports children and youth accompaniment. For children and youth accompaniment, Huellas provides spaces to promote reading, artistic initiatives such as dance, music and crafts, intercultural experiences of learning English and other languages, as well as various sports activities with soccer, jump rope, and karate, among others.

Undoubtedly, support for families, children and youth takes many forms, some unexpected. One staff member reflected emotionally on a story about a Venezuelan migrant family that has had a lasting impression on her. The story came up in reflection about the challenges around migration, how the neighborhoods are absorbing these challenges, and the support given to participants. The staff person underlined that these neighborhoods confront the reality of the migration crisis daily. She began to tell the story; she explained that there were two Venezuelan sisters who participated in and were active in a Huellas youth group. As they approached the end of the 2022 calendar year, as is typical in Colombia, the group prepared an end-the-year holiday celebration. As part of the celebrations, staff took and printed photos of the youth participants to gift them at the celebration. She continued,

We wanted to give all the kids the photos as a gift, to celebrate and remember the good year together. On the day of the celebration, we noticed that these two young Venezuelan sisters and their family were not present and when asked about it, neighbors mentioned that they were setting off to return back to Venezuela. We were told that the family was planning to walk to Venezuela and that from Medellín they thought they would make it to the border in about a month [almost 400 miles]. It was so difficult to hear. I was so upset, upset that we could not say goodbye, upset that they might not be safe. This was December 7, when the celebration happened; and then on December 8, I happened to be traveling on my motorcycle to my home and came across the family, and another family, on the highway, walking alongside the road. They were 13 people: eight kids and five adults. I pulled over immediately. They explained to me their plan to walk to Bucaramanga [over 250 miles from Medellin] and then take a bus to Cúcuta [about 6–7 h or more], which was on the Venezuelan border. For some reason it was so emotional for me. As it happened, I had their photos in my backpack from the day before. I was able to give it to them (staff person, personal communication, May 2023).

It was hard for Alba to witness and understand. After the encounter, she spoke to her parents, and they as a family assumed a form of accompaniment. They helped the two families with bus tickets for part of the route to get closer towards the Venezuelan border. They trusted that the decision to return to Venezuela by the families was the decision that they needed to make, even if they worried about their safety and health. During the following weeks, the weather was very bad – mostly rain – and Alba could not help but consider how difficult the trip was both for walking and in a bus. She admitted that she had witnessed migrants walking along roads and highways throughout the years in Colombia with the crisis, but in this case having a relationship with the family, having accompanied them to that point in time, the impact was palpable.

10 Concluding Remarks

We situate Fundación Huellas’ work into the realities of migration crises and with attention to conversations about localization in development aid. Localization is operationalized through organizational policies, processes, deliverables, and behaviors, taking into account local actors, their perspectives and their knowledge. The case of Huellas shows a local nonprofit responding to migration crisis through its built-in localization practices of accompaniment. The presence of Fundación Huellas in the two neighborhoods has reached now 25 years. This was underlined by staff, volunteers, and participants as one of the most valued aspects of Fundación Huellas by the community, citing examples of other entities arriving temporarily and leaving (due to short term contracts, or moving on to the next funding stream elsewhere).

Huellas’ work was started around serving vulnerable populations who were affected by violence and insecurity, and thereby forced to internally migrate. As a result, it has built local expertise in issues around migration, which has served in its work with the current (Venezuelan) migration crisis. By studying Fundación Huellas’ approach, we bring to the foreground accompaniment, which we find to be an important dimension to localization in the context of migration crises. That is, accompaniment implies ownership and participation but through regular and sustained relationships, producing “accompanied” neighborhoods and communities. We observed that in its work, Huellas did not differentiate between those displaced by the armed conflict in Colombia and the newer Venezuelan migrants present due to the socio-political situation in their country. The inclusion criterion for services responds rather to the condition of vulnerability (often a consequence of displacement and migration). Participation in services of course also was dependent on the willingness of community members to engage in Huellas services and the different types of accompaniment, as all participation with Huellas is voluntary (staff person, personal communication, May 2023).

Our knowledge on migration crises has been dominated by aggregated statistics and Northern actors. However, local nonprofits have a rich history in responding to community needs and serving vulnerable populations when the public and for-profit sectors are absent – as is the case in the outskirts of Medellín. The response of nonprofits to migration crises around the world is evidence of the important role that they play on local and global scales. Of course, as a case study, this article does not seek to generalize its findings to all local nonprofit organizations working in migration crises. However, we contend that its findings can be applied and explored among other local nonprofits working in development aid and migration crises building off our work and the work of Peralta and Vaitkus (2019) and Wilson (2012). The case underlines especially the value of local expertise in issues around migration and the promise of accompaniment in this policy area.

We would like to observe more consideration, documentation, and conceptual development of accompaniment in nonprofit work on migration, particularly in Latin America and other contexts with legacies of colonialism and imperialism, and which have been subject to the project of development. Such cases often remain separate from European and North American examples and perspectives in the literature (see Lewis 2015). Nonprofit studies literature should contribute to understanding how localization particularly intersects with post-colonial conditions. Accompaniment, given its roots in Latin American resistance movements (Farmer 2011), provides a lens to explore how communities and nonprofits determine their own versions of localization, not at all driven by the renewed interest by donors (and scholars) to the topic nor what is à la mode in development practice.

Another area that deserves additional attention, which we have only marginally mentioned (and which Huellas has not been a beneficiary of), is the funding streams and donor commitments to localization. Multilateral and bilateral actors have been slow to implement their own rhetoric. The model of accompaniment essentially requires funding at the local level, as Paul Farmer spiritedly advocated throughout his professional life. Most donors still fall short. However, some funders such as Spirit In Action International, Trickle Up and Thousand Currents are pioneers in development aid as they provide direct funds to local actors that include families, nonprofit organizations, leaders, and social movements. For example, Thousand Current has articulated an accompaniment-way of localization … as it “funds, connects, and walks alongside the people, organizations, and movements that are finding solutions and making waves around the world” (https://thousandcurrents.org/ emphasis added).

As the introduction for this special issue observes, nonprofits engage in and are affected by migration crises in multiple ways. Indeed, the early 21st century, like many other periods of history, has been characterized by migration crises. These situations demand the attention of and are documented by national and international policy makers, media outlets, and international NGOs in all parts of the world. However, governments and their policy decisions and any international donor support are often substandard at the local level. It will be more important to understand (and support) the work of local nonprofit organizations in contexts like Colombia, where migration crises are a wicked problem that need local and supported (or perhaps better said, accompanied) solutions. The UNHCR estimated that “117.2 million people will be forcibly displaced or stateless in 2023” (UNHCR 2023b), suggesting that there will be no shortage of demand for local nonprofit responses and accompaniment like that offered by Huellas.

Appendix A: Documentary Review Inventory.

| Documentary revision code | Source of information | Author of the document |

|---|---|---|

| DR1 | Yo También Cuento. Proyecto de formación integral y capacitación informal con niños, niñas y pre-adolescentes desescolarizados | Comunidad de Hermanos Maristas y Fundación Huellas, 2009 |

| DR2 | Ciclos de Oportunidad: Una Propuesta teórica a partir de la experiencia en comunidades pobres y sus dinámicas propias de desarrollo | Araque, L. 2013 |

| DR3 | Informe final proyecto Alternativas de Desarrollo Humano Integral Sostenible para La Vereda Granizal, Municipio de Bello, Departamento de Antioquia. Convenio con PNUD | Fundación Huellas, 2014 |

| DR4 | Informe de avance Proyecto Discapacidad. Vereda Granizal, Bello. Convenio con PNUD | Fundación Huellas, 2014 |

| DR5 | Informe de acompañamiento Ecomanatiales. Convenio PNUD | Fundación Huellas, 2015 |

| DR6 | Análisis información Encuesta de participación Caseta Comunitaria Altos de Oriente II (Ejercicio de visitas domiciliarias) | Fundación Huellas, 2015 |

| DR7 | Proceso de Producción Agroecológica. Sistematiación de la experiencia | Fundación Huellas y PNUD, 2016 |

| DR8 | Sistematización BPM | Cardona, L., Villegas, L., Henao, M y Marin, B., 2017 |

| DR9 | La fuerza del voluntariado y su aporte a la sostenibilidad de las organizaciones | Araque, L., 2018 |

| DR10 | Sistematización de la experiencia de producción agrecológica en la vereda Granizal del municipio de Bello-Antioquia | Gonzalez, L., Ramírez, E. y Araque, L., 2019 |

| DR11 | Política de Protección a la Infancia Fundación Huellas | Fundación Huellas, 2019 |

| DR12 | Informe Final Luna Menstruante 2019 | Fundación Huellas, 2019 |

| DR13 | Sistematización PASI 2019 [Prevención del Abudo Sexual Infantil] | Álvarez, M., Ramírez, E. y Araque, L., 2019 |

| DR14 | Informe Técnico final Servicios básicos [proyecto Promoción de los servicios básicos y el desarrollo económico, comunitario y cultural de la vereda Granizal, municipio de Bello/Antioquia/Colombia] | Fundación Huellas, 2019 |

| DR15 | Informe PPI Cuarentena | Fundación Huellas, 2020 |

| DR16 | Informe Técnico PPI [proyecto de Dinamización de la Política de Protección a la Infancia de la Fundación Huellas] | Fundación Huellas, 2020 |

| DR17 | Informe caracterización de las familias participantes en el proyecto “acompañamiento académico para niñas, niños y jóvenes de Medellín en tiempo de Covid-19” | Fundación Huellas, 2021 |

| DR18 | Informe técnico AA [proyecto Acompañamiento académico para niños, niñas y jóvenes de Medellín en tiempos de Covid-19] | Fundación Huellas 2022 |

| DR19 | Informe de sistematizción de la experiencia: Proyecto Acompañamiento académico para niño, niñas y jóvenes de Medellín en tiempos de COVID-19 | Fundación Huellas, 2022 |

| DR20 | Estatutos de la Fundación Huellas | Fundación Huellas, 2022 |

| DR21 | Acompañamiento académico para niños, niñas y jóvenes de Medellín en tiempos de Covid-19 | Fundación Huellas, 2023 |

| DR22 | Informe analítico de aplicación delLínea base inicial (Proyecto promoción de derechos y autonomía económica de las mujeres) | Fundación Huellas, 2023 |

Appendix B: Examples of Document Review Excerpts Illustrating the Types of Acompañamiento at Fundación Huellas.

| Orientation of accompaniment | Type of accompaniment | Examples of data from Huellas documents |

|---|---|---|

| Process-oriented accompaniment | Psychosocial accompaniment |

Psychosocial accompaniment for 15 women of the Manantiales Sector, to develop in 10 meetings (DR3, 2014, p. 10) Realization of 18 meetings (nine per sector) of psychosocial and artistic accompaniment to 20 adolescents from Manantiales and Altos de Oriente II, under the principle of formation in values with a focus on rights, as part of the strategy of use of free time (DR3, 2014, p. 10) … the process of psychological accompaniment to the families of the village has been strengthened (DR8, 2017, pp. 73–74) During the year 2019 and 2020 (from September 2019 to September 2020) the psychology service was provided in all the territories where the Huellas Foundation has a presence. This psychological accompaniment service was provided at the free request of the families or persons who requested it. To carry out this service, the Huellas Foundation had two practitioners of the Psychology degree of the EAFIT university and two graduate psychologists. Before the contingency presented by the COVID-19 Pandemic, care was carried out in person, but from the moment the national government decreed containment measures through the quarantine decree, it became necessary to provide care by telephone. During this period of confinement, the importance of accompaniment was confirmed, necessary for families who, in exceptional situations of confinement and constant coexistence, needed help and advice to maintain mental health (DR16, 2020, p. 13) |

| Academic accompaniment | Development of the School Support component and the Mental Health component … It was attended by people between 6 and 79 years old. The children, adolescents and young people participated in one of the 10 school support groups and/or the three seedbeds of knowledge development (English, mathematics and reading comprehension), in addition, the mothers and caregivers were part of the training workshops for the adequate academic accompaniment at home and the volunteer team received training workshops focused on the strengthening and acquisition of pedagogical and didactic skills for the dynamization of the different spaces (DR19, 2022, p. 32 and 53) In result 1, of specific objective 1, the six activities related to academic accompaniment were carried out:

Sessions were planned, participant observation, and adjustments were made for each group according to their particular needs. In the Yellow Church and in Puerta del Cielo, academic accompaniment and mental health intervention were implemented simultaneously, at the explicit request of the person who leads the processes of the shelters (DR21, 2023, p. 11) In the sessions on academic accompaniment, the role of mothers and caregivers in the growth of their children was addressed, generating questions, reflections and new knowledge about parenting styles, understanding of individual learning processes and didactic tools that can serve as support for the approach to various topics (DR21, 2023, p. 12) Work with mothers and caregivers, both in emotional intelligence and in training for academic accompaniment (DR21, 2023, p. 23) |

|

| Technical accompaniment | Thirty eight agroecological training meetings were held with the agroecological promoter families of Altos de Oriente, in which 25 representatives of the families that have been accompanied by the promoter also participated (DR14, 2019, p. 17) Fifteen meetings of psychosocial and technical accompaniment with 15 women members of the collective weavers of illusions (DR3, 2014, p. 7) |

|

| Recreational accompaniment | One hundred fifty children and young people participate in recreational accompaniment spaces for training in values with a focus on rights and environmental awareness, as a strategy for the use of free time (DR3, 2014, p. 2) | |

| Participant-oriented accompaniment | Institutional accompaniment | Currently the relationship between the institution and the community is strengthened, fruit of the work of all these years of institutional accompaniment and the response and reception of the community (DR8, 2017, p. 62) |

| Family accompaniment | … different programs and projects such as the community restaurant, sports and recreational promotion, La Biblioteca Popular Manantiales, the Yo también cuento project, the thematic Christmas, among others; and the second, focused on family accompaniment through the Entrepreneurship Network, agroecological production, Weavers of illusions, Water purification filters [of water], High Crafts, and Recyclers of the Granizal village (DR8, 2017, p. 77) Generate processes of social inclusion from the formation in values of the children of the foundation. Principle 2: Guarantee adequate accompaniment to children and adolescents from humanitarian training processes and their rights, as well as their families (DR11, 2019, pp. 6–7) |

|

| Children and youth accompaniment | A total of 80 people were treated, in a greater proportion of children, adolescents, young people and women, who are socially allowed to express what they feel, without there being a social sanction, in terms of weakness. In total, 58 families were accompanied, mainly children and adolescents who come with their mothers (DR21, 2023, p. 21) Strengthen the resilience of children and adolescents in social and development action (DR11, 2019, pp. 6–7) At the end of the project, 135 children and young people have been accompanied in their educational process (DR21, 2023, p. 5) |

References

Abrahams, J. 2022. The Localization Agenda: A Devex Special Report. Washington, D.C.: Devex. https://devex.shorthandstories.com/the-localization-agenda/index.html#group-section-The-need-for-localization-A9MwYxRdJm.Search in Google Scholar

ACNUR. 2023. Situación de Venezuela. Geneva: The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. https://www.acnur.org/situacion-en-venezuela.html.Search in Google Scholar

Alvarado, V., S. Gómez, D. A. Gutiérrez, M. E. Otero, and M. Restrepo. 2018. Informe Mensual del Mercado Laboral. Bogotá: Fedesarrollo.Search in Google Scholar

Appe, S., and M. D. Layton. 2016. “Government and the Nonprofit Sector in Latin America.” Nonprofit Policy Forum 7 (2): 117–35. https://doi.org/10.1515/npf-2014-0028.Search in Google Scholar

Babis, D. 2016. “Understanding Diversity in the Phenomenon of Immigrant Organizations: A Comprehensive Framework.” International Migration & Integration 17: 355–69. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-014-0405-x.Search in Google Scholar

Bada, X., and A. E. Feldmann. 2017. “Mexico’s Michoacán State: Mixed Migration Flows and Transnational Links.” Forced Migration Review 56: 12–4.Search in Google Scholar

Barrera, C. 2018. La diáspora venezolana. Bogotá: Revista Credencial. https://www.revistacredencial.com/noticia/actualidad/la-diaspora-venezolana.Search in Google Scholar

Booth, D., and S. Unsworth. 2014. Politically Smart, Locally Led Development. London: Overseas Development Institute. https://odi.org/en/publications/politically-smart-.Search in Google Scholar

Cabot-Venton, C., and S. Pongracz. 2021. “Framework for Shifting Bilateral Programmes to Local Actors.” In Social Protection Approaches to COVID-19 Expert Advice Service (SPACE). United Kingdom: DAI Global UK Ltd.Search in Google Scholar

Cernea, M. 1987. “Farmer Organization and Institution Building for Sustainable Development.” Regional Development Dialog 8 (2): 1–24.Search in Google Scholar

CNN. 2022. Venezolanos en Colombia: Cuántos Hay, Dónde Están y Otros Datos. Atlanta: CNN. https://cnnespanol.cnn.com/2022/09/23/venezolanos-colombia-datos-orix/.Search in Google Scholar

Corbin, J., and A. Strauss. 2008. Basics of Qualitative Research, 3rd ed.. Thousand Oaks: Sage.Search in Google Scholar

Craney, A., and D. Hudson. 2020. “Navigating the Dilemmas of Politically Smart, Locally Led Development: The Pacific-Based Green Growth Leaders’ Coalition.” Third World Quarterly 41 (10): 1653–69. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2020.1773256.Search in Google Scholar

DNP. 2017. DNP Inicia Caracterización de los Colombianos Residentes en el Exterior. Bogotá: National Planning Department. https://www.dnp.gov.co/Paginas/DNP-inicia-caracterizaci%C3%B3n-de-los-colombianos-residentes-en-el-exterior-.aspx.Search in Google Scholar

Eisenhardt, K. M. 1989. “Building Theories from Case Study Research.” The Academy of Management Review 14 (4): 532–50. https://doi.org/10.2307/258557.Search in Google Scholar

Espacios de Mujer. 2023. La Migración Colombiana en los Últimos 50 Años. Medellín: Espacios de Mujer. http://www.espaciosdemujer.org/wp-content/uploads/migrantes.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

Farmer, P. 2006. “Accompaniment: The Missing Piece of the Funding Puzzle.” In Grantmakers in Health’s Annual Meeting on Health Philanthropy. Washington, D.C.: Grantmakers In Health.Search in Google Scholar

Farmer, P. 2011. Accompaniment as Policy. Cambridge: Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University. https://www.lessonsfromhaiti.org/press-and-media/transcripts/accompaniment-as-policy/.Search in Google Scholar

Fernández Guzmán Grassi, E., and O. Nicole-Berva. 2022. “How Perceptions Matter: Organizational Vulnerability and Practices of Resilience in the Field of Migration.” Voluntas 33: 921–35. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-021-00440-9.Search in Google Scholar

Freitez, A., C. Viso, and E. Osorio. 2021. ¿Qué se sabe sobre la migración venezolana reciente? Sistematización de artículos publicados entre 2008 y 2020. Caracas, Venezuela: Observatorio Venezolano de Migración.Search in Google Scholar

Garip, F. 2016. On the Move: Changing Mechanisms of Mexico-U.S. Migration. Princeton: Princeton University Press.10.23943/princeton/9780691161068.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Garkisch, M., J. Heidingsfelder, and M. Beckmann. 2017. “Third Sector Organizations and Migration: A Systematic Literature Review on the Contribution of Third Sector Organizations in View of Flight, Migration and Refugee Crises.” Voluntas 28: 1839–80. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-017-9895-4.Search in Google Scholar

GIFMM. 2021. “GIFMM (2021). GIFMM Colombia: Joint Needs Assessment. Bogotá D.C., Colombia. https://www.r4v.info/en/node/89279.” Bogotá D.C.: GIFMM. https://www.r4v.info/en/node/89279.Search in Google Scholar

Greenspan, I., and M. Walk. Forthcoming. “Informal Volunteering and Immigrant Generations: Exploring Overlooked Dimensions in Immigrant Volunteering Research.” Voluntas 35: 23–35. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-023-00563-1.Search in Google Scholar

Kurmanaev, A., and O. Medina. 2015. Venezuela’s Poor Neighbors Flee en Masse Years After Arrival. New York: Bloomberg Business.Search in Google Scholar

Lentfer, J., and T. Cothran. 2017. Smart Risks: How Small Grants are Helping to Solve Some of the World’s Biggest Problems. Rugby: Practical Action Publishing.10.3362/9781780449302.033Search in Google Scholar

Lewis, D. 2015. “Contesting Parallel Worlds: Time to Abandon the Distinction Between the “International” and “Domestic” Contexts of Third Sector Scholarship?” Voluntas 26 (5): 2084–103. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-014-9482-x.Search in Google Scholar

Massey, D. S., A. Joaquín, H. Graeme, Ali Kouaouci, A. Pellegrino, and T. J. Edward. 1993. “Theories of International Migration: A Review and Appraisal.” Population and Development Review 19: 431–66. https://doi.org/10.2307/2938462.Search in Google Scholar

Merriam, S. B. 1998. Qualitative Research and Case Study Applications in Education. Hoboken: Jossey-Bass.Search in Google Scholar

Meyer, M., and R. Simsa. 2018. “Organizing the Unexpected: How Civil Society Organizations Dealt With the Refugee Crisis.” Voluntas 29 (6): 1159–75. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-018-00050-y.Search in Google Scholar

Miles, M. B., and A. M. Huberman. 1994. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook. Thousand Oaks: Sage.Search in Google Scholar

Mingot, E. S., and J. de Arimatéia da Cruz. 2013. “The Asylum-Migration Nexus: Can Motivations Shape the Concept of Coercion? The Sudanese Transit Case.” Journal of Third World Studies 30 (2): 175–90.Search in Google Scholar

Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Colombia. 2023. Antecedentes Históricos y Causas de la Migración. Bogotá: Ministry of Foreign Affairs. https://www.cancilleria.gov.co/colombia/migracion/historia.Search in Google Scholar

Munck, R. 2008. “Globalisation, Governance and Migration: An Introduction.” Third World Quarterly 29 (7): 1227–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436590802386252.Search in Google Scholar

Peralta, K. J., and E. Vaitkus. 2019. “Constructing Action: An Analysis of the Roles of Third Sector Actors During the Implementation of the Dominican Republic’s Regularization Plan.” Voluntas 30 (6): 1319–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-018-0003-1.Search in Google Scholar

Safouane, H. 2017. “Manufacturing Striated Space for Migrants: An Ethnography of Initial Reception Centers for Asylum Seekers in Germany.” Voluntas 28 (5): 1922–39. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-016-9813-1.Search in Google Scholar

Saldinger, A. 2021. Samantha Powers Lays Out Her Vision for USAID. Washington, D.C.: DEVEX. https://www.devex.com/news/samantha-power-lays-out-her-vision-for-usaid-102003.Search in Google Scholar

Silva, A. C., and D. S. Massey. 2015. “Violence, Networks, and International Migration from Colombia.” International Migration 53 (5): 162–78. https://doi.org/10.1111/imig.12169.Search in Google Scholar

Simsa, R. 2017. “Leaving Emergency Management in the Refugee Crisis to Civil Society? The Case of Austria.” Journal of Applied Security Research 12: 78–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/19361610.2017.1228026.Search in Google Scholar

Simsa, R., P. Rameder, A. Aghamanoukjan, and M. Totter. 2018. “Spontaneous Volunteering in Social Crises: Self-Organization and Coordination.” Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 48 (2): 103S–22S. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764018785472.Search in Google Scholar

Sriskandarajah, D. 2015. Five Reasons Donors Give for Not Funding Local NGOs Directly. London: The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/global-development-professionals-network/2015/nov/09/five-reasons-donors-give-for-not-funding-local-ngos-directly.Search in Google Scholar

Stake, R. E. 1995. The Art of Case Study. Thousand Oaks: Sage.Search in Google Scholar

Strokosch, K., and S. P. Osbornes. 2017. “Co-Producing Across Organisational Boundaries: Promoting Asylum Seeker Integration in Scotland.” Voluntas 28 (5): 1881–99. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-016-9810-4.Search in Google Scholar

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2022. Global Trends: Forced Displacement in 2022. Geneva: UNHCR.Search in Google Scholar

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2023a. Venezuelan Factsheet. Geneva: UNHCR. https://reporting.unhcr.org/venezuela-factsheet.Search in Google Scholar

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2023b. Global Appeal. Switzerland: UNHCR. https://reporting.unhcr.org/globalappeal-2023.Search in Google Scholar

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2024. Colombia Situation 2024. Geneva: UNHCR. https://reporting.unhcr.org/operational/situations/colombia-situation.Search in Google Scholar

Van der Leun, J., and H. Bouter. 2015. “Gimme Shelter: Inclusion and Exclusion of Irregular Immigrants in Dutch Civil Society.” Journal of Immigrant and Refugee Studies 13 (2): 135–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/15562948.2015.1033507.Search in Google Scholar

Van Praag, O. 2019. Understanding the Venezuelan Refugee Crisis. Washington, D.C.: Wilson Center. https://www.wilsoncenter.org/article/understanding-the-venezuelan-refugee-crisis?gad_source=1&gclid=Cj0KCQiAkKqsBhC3ARIsAEEjuJiu6lW698FXA9hMJsyC_wIQMrnVc3feUom3EAh0MxFJOE2xwnMhKo8aAq3REALw_wcB.Search in Google Scholar

van Wessel, M., T. Kontinen, and J. Bawole, eds. 2023. “Starting from the South: Reimagining Civil Society Collaborations in Development.” In Reimagining Civil Society Collaborations in Development. London: Routledge Explorations in Development Studies.10.4324/9781003241003Search in Google Scholar

Wilson, C. E. 2012. “Collaboration of Nonprofit Organizations with Local Government for Immigrant Language Acquisition.” Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 42 (5): 963–84. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764012461400.Search in Google Scholar

WINGS. 2023. Philanthropy Can Be a Solution to Making Localisation a Reality. Sao Paulo: Policy Paper. https://wings.issuelab.org/resources/40705/40705.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

Yu, H. E. 2022. Medellín’s Holistic Housing for Refugees. Brooklyn: Mayor’s Migration Council. https://www.mayorsmigrationcouncil.org/.Search in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Nonprofit Organizations and Public Policy in Refugee and Other Migrant Crises: Concepts and Frameworks

- Are We All in This Together? Examining Nonprofits’ Perceptions of Governmental Actors in the Management of the U.S. Refugee Crisis

- Governance in Crisis. Examining the Role of TSOs in Asylum Seekers Reception in France and Italy

- Migration Crisis in the Andes: A Case Study of Localization and Acompañamiento from Medellin, Colombia

- Perceived and Pursued Opportunities from Mass Deportation Threats: The Case of Haitian Migrant-Serving Nonprofit Organizations in the Dominican Republic

- Breaking Down the Wall: The Effect of Immigration Enforcement and Nonprofit Services on Undocumented Student Academic Performance

- Frontline of Refugee Reception Policy: Warsaw Reception Centers During the 2022 Ukrainian Crisis

- Policy Brief

- Achieving Better Integration of Ukrainian Refugees in the Czech Republic: Making Use of Expertise and Addressing Cultural Differences

- Research Articles

- Who Volunteers at Refugee and Immigrant Nonprofits? Results from Two Studies

- Testing the Relationship Between Local Context and Immigrant-Serving Nonprofit Strategies

- Commentary

- Burden Shifting to U.S. Nonprofits: Supporting Access to Asylum When Legal Protection Frameworks Fail

- Book Review

- Book Review for “Nonprofits, Public Policy, and Migration Crises” Special Issue of Nonprofit Policy Forum

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Nonprofit Organizations and Public Policy in Refugee and Other Migrant Crises: Concepts and Frameworks

- Are We All in This Together? Examining Nonprofits’ Perceptions of Governmental Actors in the Management of the U.S. Refugee Crisis

- Governance in Crisis. Examining the Role of TSOs in Asylum Seekers Reception in France and Italy

- Migration Crisis in the Andes: A Case Study of Localization and Acompañamiento from Medellin, Colombia

- Perceived and Pursued Opportunities from Mass Deportation Threats: The Case of Haitian Migrant-Serving Nonprofit Organizations in the Dominican Republic

- Breaking Down the Wall: The Effect of Immigration Enforcement and Nonprofit Services on Undocumented Student Academic Performance

- Frontline of Refugee Reception Policy: Warsaw Reception Centers During the 2022 Ukrainian Crisis

- Policy Brief

- Achieving Better Integration of Ukrainian Refugees in the Czech Republic: Making Use of Expertise and Addressing Cultural Differences

- Research Articles

- Who Volunteers at Refugee and Immigrant Nonprofits? Results from Two Studies

- Testing the Relationship Between Local Context and Immigrant-Serving Nonprofit Strategies

- Commentary

- Burden Shifting to U.S. Nonprofits: Supporting Access to Asylum When Legal Protection Frameworks Fail

- Book Review

- Book Review for “Nonprofits, Public Policy, and Migration Crises” Special Issue of Nonprofit Policy Forum