Abstract

Among Lester Salamon’s early theoretical contributions was the introduction of the “Voluntary Failure” concept. In a series of articles published in the second half of the 1980s (Salamon, L. M. 1987a. “Of Market Failure, Voluntary Failure, and Third-Party Government: Toward a Theory of Government-Nonprofit Relations in the Modern Welfare State.” Journal of Voluntary Action Research 16 (1–2): 29–49. Reprinted in Salamon (1995): 33–49, Salamon, L. M. 1987b. “Partners in Public Service: The Scope and Theory of Government-Nonprofit Relations,” In The Nonprofit Sector. A Research Handbook, edited by W. Powell Walter, 99–117. New Haven: Yale University Press, Salamon, L. M. 1989. “The Voluntary Sector and the Future of the Welfare State.” Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 18 (1): 11–24. Reprinted in Salamon (1995): 203–19) Salamon rejects the existing theories concerning the existence and the growth of nonprofit entities, both demand-side theories such as “government failure” (Weisbrod) and “contract failure” (Hansmann) and supply-side theories (James). He introduces the so-called “third-party government” approach underlining the interdependence between the state and various other (profit and nonprofit) social actors (Salamon Lester M. and Toepler S. 2015. “Government–Nonprofit Cooperation: Anomaly or Necessity?” Voluntas 26: 2155–77). The “voluntary failure theory” is based on the recognition of four limits of nonprofit organizations’ action: (a) philanthropic insufficiency; (b) philanthropic particularism; (c) philanthropic paternalism; (d) philanthropic amateurism. These shortcomings can be overcome by the creation of an institutional framework of collaboration between the public administration and the most organized part of civil society, namely the so-called third-sector organizations. The aim of this paper is to open a discussion around the adequacy of the above-mentioned approach to explain the complex configurations that current relationships between public administration and third sector organizations have assumed in Western democracies, especially in the field of welfare policies. We will do so through the analysis of the recent scientific literature on government-nonprofit relationships, with a particular focus on the so-called “new public governance” (Osborne Stephen, P. 2006. “The New Public Governance?” Public Management Review 8 (3): 377–87, Osborne Stephen, P. ed. 2009. The New Public Governance? Emerging Perspectives on the Theory and Practice of Public Governance. London: Routledge) and the co-creation and co-production paradigm (Torfing, J., E. Sørensen., and A. Røiseland. 2016. “Transforming the Public Sector into an Arena for Co-creation: Barriers, Drivers, Benefits, and Ways Forward.” Administration & Society: 1–31), that emphasize the involvement of citizens (i.e. users or clients) and their associations in the definition of the policies, programs, and services directed to them.

1 Voluntary Failure Theory and Third Party-Government

To fully understand Salamon’s contribution, it is necessary to place it in the historical period, particularly in the economic, political, and social context of his time. His thinking emerged in that historical contingency in which conservative parties came to power and pushed new economic policies both in the USA (Reaganomics) and in the UK (Thatcherism). After the “Glorious Thirty”[1] of the birth, development, and diffusion of the Beveridge Welfare State, the predominance of the so-called neo-liberal economic theories began, focusing on deregulation, privatization, and the reduction of public interventions, especially in the field of welfare policy.

Today we are aware that those economic recipes were wrong and after thirty years of neo-liberalism (1978–2008), scholars (Piketty 2011; Porter Michael 2011; Rajan 2019) have noted all the disasters they wrought in terms of increasing inequalities on a planetary scale. Not only has the North-South and West-East gap increased, but internal inequalities have also grown in the developed West between regions, cities, and within metropolitan areas (i.e. between city centers and suburbs). But in those years the mainstream thought in the social and economic sciences in particular was dominated by a neo-liberal creed.

Salamon took a different position and was decidedly in opposition to this cultural dominance, undoubtedly showing courage to deviate from the dominant scientific and academic norms. Salamon’s argument (1987a) is fluid, linear, and well-structured. He begins with the pars destruens demonstrating, first with a theoretical reflection and then with the support of a vast amount of empirical data, the fallacies of the main theories of the time concerning the relationship between the government and voluntary sector.

Despite the fact that government in the United States relies more heavily on nonprofit organizations than on its own instrumentalities to deliver government funded human services, and that nonprofits receive more of their income from government than from any other single source, the phenomenon of government nonprofit partnership has been largely overlooked both in analyses of the welfare state and in research on the voluntary sector. (p. 29)

According to Salamon, the partnership between the government and the nonprofit sector has been overlooked not because of its novelty or because of a lack of research but because of a “weakness in theory” (p. 32). Then, he continues his reasoning trying to demonstrate the fallacy of the existing theories. He identifies three main theories. The first one, “the theory of the Welfare State” is inadequate because in the US there is a tendency to emphasize the monolithic character of the American welfare state and to deemphasize the continuing role of voluntary groups in public programs.

The second one is Weisbrod’s “Market Failure/Government Failure Theory.” As is well known, the theory states that a private, voluntary sector arises to meet the unsatisfied demand for collective goods. According to this theory, private, nonprofit organizations exist to supply a range of collective goods desired by one segment of a community but not by a majority. Salamon underlines that since the nonprofit sector is viewed as a substitute for government, this theory regarding government support for nonprofit organizations “has little theoretical rationale” (p. 35).

The third one is Hansmann’s “Contract Failure Theory.” The key notion of this theory is that for some goods and services, such as care for the aged, the purchaser is not the same as the consumer. Therefore, some proxy has to be created to offer a degree of assurance that the goods or services delivered meet adequate quality and quantity standards. The theory states that the “nonprofit form” provides that proxy. Salamon affirms that this theory provides little rationale for government reliance on nonprofits or government regulation of nonprofits since it would suppose a direct involvement of public agencies in service delivery.

After this poignant and detailed examination of the theoretical approaches of his time, Salamon moves on to pars construens proposing his two main theories: “voluntary sector failure” and “third-party government.”

On the idea of a monolithic welfare state, Salamon argues that there is clear evidence that regarding the actual delivery of services, the welfare state in the US makes use of a wide variety of third parties to carry out governmental functions. In his opinion, this gives rise to “an elaborate system of third-party government” in which government shares its decision-making power with a wide array of third-party implementers (e.g. local public agencies, for-profit bodies, and nonprofit organizations).

Concerning the other two theories “government failure” and “contract failure” Salamon claims that they are limited because they do not take into account the fact that also the voluntary nonprofit sector has its deficiencies. It is exactly to overcome these failures that necessitate government action and justify government support to the voluntary sector. Salamon identifies four shortcomings: philanthropic insufficiency; philanthropic particularism; philanthropic paternalism; and philanthropic amateurism.

The first one, philanthropic insufficiency, describes the ways the voluntary sector, as a provider of collective goods, lacks sufficient resources to cope with the human-service problems of an advanced society adequately and reliably. The second one, philanthropic particularism, outlines the tendency of voluntary organizations and their benefactors to focus on particular subgroups of the population, such as ethnic, religious, neighborhood, specific interest, etc. The third one, philanthropic paternalism, results from the fact that the influence over the definition of “community needs” rests in the hands of those in command of the greatest resources. As a consequence, some services favored by the wealthy may be promoted, while others requested by the poor are scarcely delivered. The fourth one, philanthropic amateurism, highlights the fact that voluntary organizations rely greatly on volunteers in running their activities. Nonprofit bodies that depend on volunteering are limited by dependence on contributions and often are unable to provide adequate wages and attract highly skilled professional personnel. Salamon’s argument then goes as follows:

(…) the voluntary sector’s weaknesses correspond well with government’s strengths, and vice versa. Potentially, at least, government is in a position to generate a more reliable stream of resources, to set priorities on the basis of a democratic political process instead of the wishes of the wealthy, to offset part of the paternalism of the charitable system by making access to care a right instead of a privilege, and to improve the quality of care by instituting quality-control standards

(…) [on the other side] voluntary organizations are in a better position than government to personalize the provision of services, to operate on a smaller scale, to adjust care to the needs of clients rather than to the structure of government agencies, and to permit a degree of competition among service providers. (p. 42)

In conclusion, Salamon states that there is a strong theoretical rationale that sustains government-nonprofit cooperation in many fields of public policy. The author returns to the topic in two other well-known papers (Salamon 1987b, 1989) in which he reinforces his argument with the support of a significant amount of data. He states that the paradigm of competition between government and the nonprofit sector – even if it has been a longstanding symbol for defenders of the voluntary sector – fails before an accurate analysis of the reality; and over time, shows itself to be self-defeating for the sector as a whole. There is no doubt in his opinion that:

The partnership that has emerged between government and the nonprofit sector in the delivery of human services is one of the more significant, though hardly unique, American contributions to the evolution of the modern welfare state. (Salamon 1987a, p. 47)

In a more recent article published by Salamon and one of his collaborators (Salamon and Toepler 2015), the authors recognized that the relationships between nonprofit organizations and the public sector is not always a win-win situation but, in order to display the highest level of effectiveness some conditions must be guaranteed, and several risks should be avoided. As they state:

Of central concern here are at least four potential dangers: (a) the potential loss of autonomy or independence that some fear can result from heavy dependence on government support; (b) ‘‘vendorism,’’ or the distortion of agency missions in pursuit of available government funding; (c) bureaucratization, or over-professionalization resulting from government program and accounting requirements; and (d) the stunting of advocacy activity in order not to endanger public funding streams. (p. 2169).

We share the concerns about these negative effects, potentially present in any institutional relationship, and we underline the fact that in order to establish the usefulness and the feasibility of a public-nonprofit partnership several conditions should be met. In the final section of this article, we will return to that issue.

2 New Policy Trends and Public Administration Approaches

Western societies changed greatly in the 35 years since Salamon first published his studies. In the next sections, we will analyze some of the main areas of research and key policy trends in the field of public administration and the welfare state, including the social investment paradigm; the New Public Governance; and finally, the co-creation or co-production framework. These will be evaluated to determine if the Salamon approach is still relevant and fruitful, and what we can still learn from it.

2.1 The “Social Investment State”: Beyond Neoliberalism?

The last two decades have seen in many developed countries of the West the implementation of “demand support” policies in health and welfare sectors. Not just for reasons of public expenditure containment, these policies aimed broadly to strengthen the purchasing power of citizens with regard to a number of social, health and home care services (Hemerijck 2002). The measures taken fall within the framework of a long process of revision, redefinition, and rearticulation of the role and functions of public institutions regarding the responsibility to ensure a certain level of well-being for the population (Hemerijck 2012).

The long process of building, institutionalizing, and legitimizing different welfare state models in Europe and generally in the developed West (Pierson 2001) followed two phases. The first phase –referred to as the “golden era” or the “glorious thirty”–coincided substantially with the period between the end of World War II and the oil crisis of the early 1970s (1945–1975). The second phase is characterized by the emergence of “neo-liberal” policies of fiscal retrenchment and public budget cuts. It began in the United Kingdom and the United States, before gradually spreading across Europe and then the Global South. During this period (1978–2008), measures and practices inspired by the logic of the market have been gradually introduced within the systems of welfare in order to overcome the limitations, malfunctions and inequalities, which connoted the service delivery model based mainly on public agencies. During the thirty years of neo-liberal domination, several innovations have been adopted:

the 1980s saw the spread of “contracting-out” tools in the acquisition of social, health, and education services by the government, mainly to non-profit providers; as well as

the adoption of “quasi-markets” models particularly in the context of health care and later on in educational policies as well. In these models, a plurality of providers, public and private for-profit as well as private non-profit, compete in highly regulated markets; and

during the 1990s, the logic of private management in public administration, the so-called “new public management,” proliferated, which tended to emulate the managerial top levels of the private sector in government, both in terms of rewards (i.e. of salary increases and career progression), and in terms of responsibilities with respect to the decisions they made.

All these policies, while making substantial changes in the welfare services delivery system in Western democracies, nevertheless firmly maintained the decision-making power in the hands of the public sector (Hemerijck 2012a, 2012b). Alongside the public agencies, a number of private providers selected by the public sector (logic of the “offer support”) gradually appeared through a series of contracting procedures for the acquisition of services (e.g. private treaty, public invitation to purchase, tender to the lowest bidder, or under the “most economically advantageous” offer, etc.)

It was only in the late 1990s and early 2000s that various European countries experimented with measures and practices inspired by the logic of the “support of the demand,” and then scaled up them in a systematic way, some of which had been already adopted, not always with success, in USA during the previous decade. These are policies which, using various operating modes (e.g. vouchers, service-ticket, service-checks, personal budgets, virtual budget, etc.), are aimed at improving the quality of services while enabling cost savings. This is achieved through the increased ability to purchase services by specific categories of “persons in need.” Whatever the concrete form of implementing “demand support” policies (Standing 2004) they share two guiding principles:

to empower, improve, enhance, strengthen, and increase the “power” (sovereignty) of the service users over the delivery agencies, not only in terms of purchasing power but also in “personal autonomy”; and

competition: to increase service quality and reduce the cost for buyers by introducing mechanisms that induce providers to compete for a greater market share (social regulation).

These recent changes, which followed the multiplication and diversification of public and private actors in the field of welfare, has led some authors, such as Jenson (2014) to point out that, in fact, at least four logics (principles) of resource allocation and delivery of services operate in this area: the logic of the market; the logic of the state; the associative logic; and the logic of the informal sector.

the logic of the market is based on the pursuit of profit through competition;

the logic of the state is based on the principle of providing citizens with the recognition of “social rights”, and operates through the formal public institutions and bureaucracies;

the associative logic is based on ethical and moral codes and operates through a number of nonprofit organizations; and

the private informal logic sees the family as a key institution and is based on practices that incorporate personal and moral obligations, emotional relationships, and social relationships.

The ever-changing interplay of these four logical or operating principles engenders specific institutional configurations and models of welfare (i.e. schemes), which are characterized by a peculiar “division of labor” between the different actors involved in the caring sector. During the second half of the 2000s, three main narratives emerged in the public and academic debate, especially at European level:

a first narrative developed within the longstanding scientific tradition of welfare state studies: it is the so-called issue of personalization (Needham 2014);

a second narrative developed as part of the scientific debate on the social economy and concerns the issue of social entrepreneurship (Defourny, Hulgard, and Pestoff 2014); and

finally, the third narrative is completely external to these two traditions. It was born from the emergence of new information and communication technologies, and a search for innovative ways to meet the growing and changing needs of society. This is the concept of social innovation (A.A.V.V. 2006), which represents both a confrontation with, and a bridge between, the two cultural and research traditions that had always proceeded on parallel paths without any exchange among them.

The topic of social innovation, given its positive connotation, played the role of a catalyst. It has been able to foster the encounter of two streams of research that developed separately and grew in parallel for many years: welfare studies and social enterprise studies. It succeeded in gather together several scholars and researchers coming from different scientific disciplines and approaches around some research streams and various research centers both at European and international level. This synthesis prepares the ground for elaboration and the emergence of new theoretical approaches to social policy and welfare systems, as well as to the study of the evolution of modern and postmodern societies.

In order to exit from the worldwide economic-financial crisis (i.e. era of austerity), particularly in the European contest, a new paradigm (social investment framework) emerged in welfare policy, trying to develop a new configuration of welfare systems based on four key terms and conceptual frameworks, redefining the role and functions of these sub-systems of the social structure: market, state, societal community and culture. As far as the market subsystem is concerned, in order to face the challenges of a globalized economy, we observe the adoption of an orientation toward a continuous innovative approach, assuming a “sustainable attitude”; meaning to be responsible for the impacts the business units (corporations) produce on three domains: economic, social and environmental.

In this new framework the Public Sector (see Table 1) should adopt a “social investment policy” orientation, meaning that public policies, especially in the welfare area, should be designed to promote and incentivize the autonomous expression of its citizens (i.e. empowerment) helping them to fully develop their capabilities. This is called the “life cycle approach” and is defined by the idea that public policy should sustain the citizens giving them resources (e.g. economic, cultural, and social capital) in order to be well equipped to face the crucial and critical phases of their life cycle.

Key words of welfare configurations.

| Welfare state | Neo-liberalism | Social investment | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Main actor | State | Market | Society/community |

| Criteria | Universalism | De-regulation | Personalization |

| Principle | Equality | Freedom (of choice) | Inclusion/cohesion |

| Key policy issue | Participation | Privatization | Social entrepreneurship |

| Beneficiaries | Users | Clients/customers | Active citizens |

| Legitimacy base | Social rights | Means test | Social innovation |

| Selectivity | |||

| System of coordination | Planning | Marketization | Accreditation systems |

| Logic of actors’ relationship | Negotiation | Competition | Partnership |

In the civil society relational sphere, the new framework requires a different role from the collective actors operating in it. The variety of groups, movements, associations, and organizations that are active in this societal space should adopt a more open attitude toward the new typology of needs arising from the deep structural and demographic changes that occurred in the last two decades in the western world. The adoption of a “social inclusion paradigm” requires moving from a “citizenship-based approach” to a “human rights” approach (Donati 2015), especially taking into account the growing number of migrants.

As it relates to the cultural subsystem of the society, in order to cope with the challenges of a multi-ethnic, multi-religious, multi-cultural society, different institutions, whether in the market or in the state and civil society, should promote a “social cohesion approach.” In doing so, they should try to overcome the ultra-individualistic cultural orientation which is mainstreaming in contemporary (i.e. post-modern) societies (Donati 2015).

In synthesis the concept of “developmental” welfare state (Hemerijck 2007) provides a common language for a political program. It prioritizes high levels of employment for both men and women as a fundamental political objective. By combing elements of flexibility and security it seeks to facilitate the reconciliation of work and family life expectations, especially for women. This concept includes new forms of governance on the basis of clever combinations of public, private and individual resources and actions.

2.2 From New Public Management to New Public Governance

To our knowledge, the first scholar to introduce the idea of paradigms or models of public administration (PA) is Stephen Osborne in a (2006) editorial, which was published in a themed issue of the Journal “Public Management Review”. In that editorial, Osborne argued that the “traditional PA” model lasted from the late nineteenth century through the late 1970s. The second model, the New Public Management (NPM), was mainstream during the 1980s and 1990s and a third one, the New Public Governance (NPG), emerged in the mid-2000s.

Osborne suggests that the first paradigm was characterized by a focus on administering set rules and guidelines and included a central role for bureaucracy in policy making and implementation. The NPM paradigm, on the other hand, was based on the use of markets, competition, and contracts for resource allocation and service delivery within public services. It included an emphasis on controlling inputs and outputs, evaluation, performance management, and audits. Finally, the NPG paradigm “posits both a plural state, where multiple inter-dependent actors contribute to the delivery of public services and a pluralist state, where multiple processes inform the policy making system” (p. 384). According to Osborne, the NPG model is concerned with inter-organizational relationships (i.e. trust, relational capital, and relational contracts) and the governance of processes, focusing on service effectiveness and outcomes (Osborne 2009).

Table 2 shows the main characteristics of the three models of public administration. The key point, as it relates to our reasoning, is the role that the service users (citizens) assume in each model. In the TPA configuration, they have a passive role as recipients of services designed, delivered and evaluated by civil servants. In the NPM setting, they are treated as customers in the market, assumed to driven by rational choices. Finally, in the NPG arrangement, the citizens begin to have an active role in the different stages of services delivery.

The role of public servants in different paradigms of public governance and management.

| Traditional public administration | New public management | New public governance | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Key concepts | Public goods | Public choice | Public value |

| Role of public professionals | Implementation of professional standards, rule adherence Delivering |

Achievement of pre-set objectives | Value co-creators Facilitators, enablers |

| Role and tasks of public managers | Commanders Managerial planning and process control by the formal rules and legal authority |

Efficiency and market maximisers Managerial control over professionals via predefined goals and customers’ wishes |

Explorers Meta governance, coordination, facilitation |

| Professional-client relation | Top-down, one-directional relationship | Output oriented management, performance measurement | Collaborative relationship based on user empowerment and interdependence between public, private and non-profit actors |

| Service users | Passive consumers | Rational customers | Co-producers (Prosumers) |

| Principles of engagement | Fairness/equal treatment, Transparency Effectiveness, Efficiency, Professional knowledge and discretion, |

Efficiency/Cost reduction, Specialization, Competitiveness Short-term perspective, Goal-achievement, |

Social justice, Inclusion, Participation, Influence, Deliberation, Power balancing, Innovativeness, Transparency, meaningfulness, Professional engagement Long-term perspective |

| Principles of accountability | Accountability to decision-makers | Accountability to client satisfaction | Accountability to citizens (as service users) |

Needless to say, the configuration most in line with the Salamon’s “third party government” model is the latter. Mainly because, in order to be effective, it requires the establishment of a collaborative relationship based on user empowerment and interdependence between public, private, and non-profit actors.

2.3 Co-creation/Co-production in Search of a New Paradigm

In the last decade, the concept of co-production and related terms (e.g. co-creation, co-design, co-governance, co-planning) have became a central theme of public policy reform in western societies. Such concepts acted as an innovative way of planning, managing, delivering, and assessing services provided to citizens by the government (Torfing, Sørensen, and Røiseland 2016). This is especially true in the fields of health, education, social services, and housing. This trend is exemplified by the publication of several thematic issues in high ranked international scientific journals.[2]

The supporters of this approach claim that it has positive effects on the planning and delivery of effective public services. For example, one possible benefit is the responsiveness to the democratic deficit, acting as a path to active citizenship and active communities. Supporters have also claimed it is a means by which to reap additional resources to public services delivery. Unfortunately, very few evidence-based studies have been completed to demonstrate the aforementioned outcomes and impacts.

Adopting a more theoretical sociological approach, we argue that the concept itself is neither a positive or negative one, therefore in order to understand (i.e. measure) the real contribution that co-creation might have on the service delivery to which it is applied, it must be contextualized and specified further. Meaning, it is necessary to clarify who are the actors implied by the “co” and what are the objects of the “production” or “design” or “planning.”

We stress the risk linked to a naïve adoption of a co-design or co-production framework. In particular we highlight the possibility that the focus on the “activation” or “involvement” of the end users (i.e. beneficiaries) of a service at the individual level, could have the effect of “ruling out” the intermediary bodies, which historically have played a crucial mediation role between citizens and the public administration officers and agencies, such as social economy organizations (e.g. associations for parents, the disabled, mentally ill persons, the elderly or other disadvantaged groups), social enterprises, or voluntary organizations.

In the scientific literature it is possible to find many definitions and approaches to co-production or co-creation depending on the different disciplines and schools of thought. The first term, co-production, boasts a long tradition whereas the second one, co-creation, is more recent and less analyzed. For instance, in the public management literature there are two main definitions of “co-production”.

The first one is more specific. Osborne et al. consider co-production “the voluntary or involuntary involvement of public services users in any of the design, management, delivery and/or evaluation of public services” (Osborne, Radnor, and Strokosch 2016: 640).

The second one instead is more inclusive. Howlett et al. prefer the definition coined by John Alford in 1998, that sees “co-production” as the “involvement of citizens, clients, consumers, volunteers and/or community organizations in producing public services in addition to consuming or otherwise benefiting from them (Alford 1998, p. 128)” (Howlett, Kekez, and Poocharoen 2017: 2).

Although co-production emerged and developed as a concept that emphasized citizens’ engagement in policy delivery, however, its meaning has evolved in recent years to include both individuals (i.e. citizens and quasi-professionals) and organizations (citizen groups, associations, non-profit organizations) collaborating with government agencies in the design, management, and delivery of services (Alford 1998; Poocharoen and Ting 2015) (ibidem).

In general terms, the main traditions of research and approaches concerning co-creation or co-production are spread across three different literatures:

Management literature (Osborne and Strokosch 2013; Osborne et al. 2016);

Civil society, democracy, social movements studies (Pestoff 2014); and

Urban renewal, local development, social planning (Brandsen et al. 2018).

A first step in defining an analytical framework is to identify conceptual sub-dimensions of the co-production semantic field, as is done by the typology elaborated by Brandsen and Pestoff (2006). The authors recognize three distinct levels of relationship between citizens and the public sector: co-governance, co-management, and co-production:

Co-governance (macro-level) refers to an arrangement in which citizens’ associations participate in the planning and delivery of public services. The focus on co-governance is primarily on policy formulation.

Co-management (meso-level) describes a configuration in which citizens’ associations produce services in collaboration with the public sector. Co-management refers primarily to interactions between organizations. Its focus is primarily on policy implementation.

Co-production (micro-level) represents a situation where citizens (through associations) produce their own services at least in part. Its focus is primarily on services delivery.

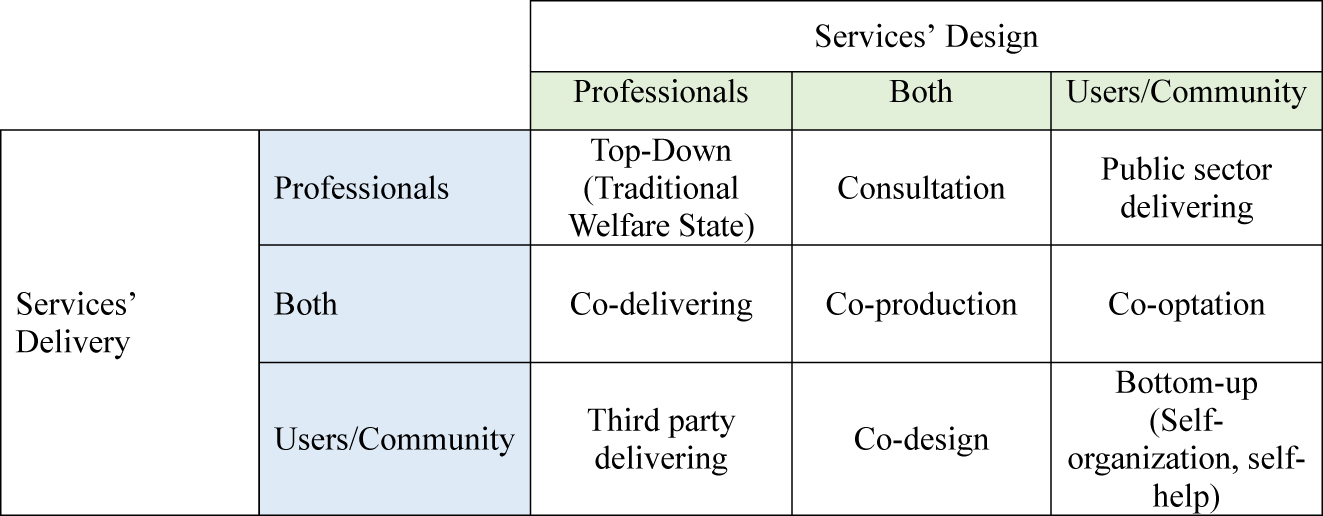

Adopting a micro level of analysis, Bason (2010) analyses several examples and case studies from the private and the public sector. From this study the author identifies four distinct roles for citizens in the co-creation process: explorer, ideator, designer, diffuser.[3] Others (Voorberg, Bekkers, and Tummers 2015) have described three roles of citizens in the co-creation process: co-implementer, co-designer, co-initiator.[4] Taking into consideration two dimensions of the service implementation process: (1) who is responsible for the service design and (2) who is responsible for the service delivery, Bovaird (2007) develops a typology of co-production along two axes (see Figure 1).

User and professional roles in the design and delivery of services (Boyle and Harris 2009, p. 16).

Depending on the extent of professional versus user involvement in planning the service and delivering the service it is possible to identify nine configurations. Moving from the top left cell of the matrix to the bottom right cell we can shift from a “pure public services model” to a “typical voluntary/community sector” model, having the highest form of co-creation and co-design in the middle of the nine cells table.

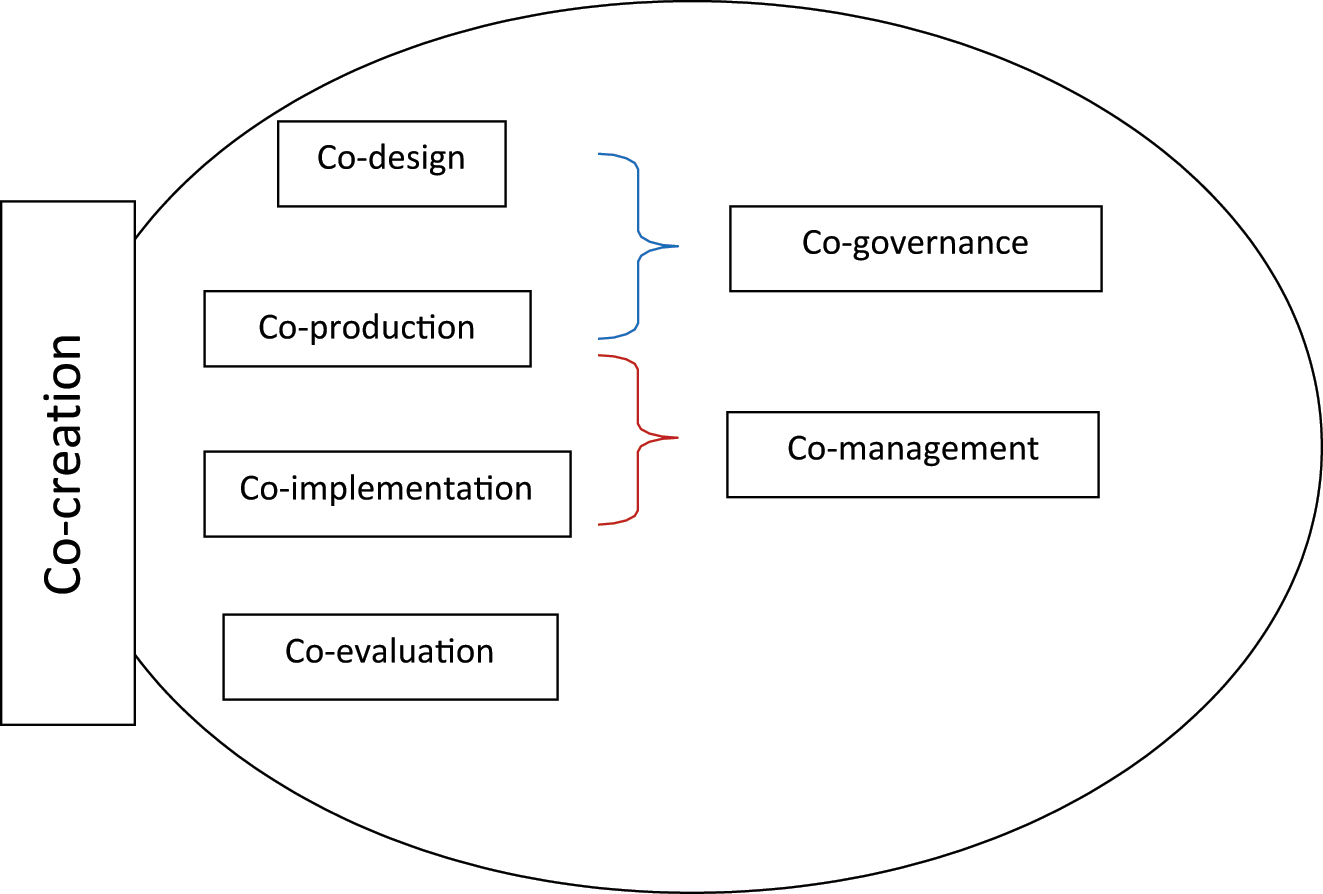

In synthesis, in our opinion, it is possible to identify the following analytical distinctions of the group of policies that have been defined through the “co-” suffix (Figure 2).

In the first instance, which is at the highest level of the “abstraction ladder,” we have the term co-creation that encompasses all the others. It refers to an arrangement where there is a certain level of collaboration between the “producer” and the “user” of a good or service. In the field of business, the phenomenon has been called “prosumer,” meaning the merging of producer and consumer roles.

The internal dimensions of the co-creation process.

Inside the co-creation process, we can find several phases or degrees of collaboration moving from a macro to a micro level of analysis, including the meso level.[5]

2.4 The Down Side of Co-creation

Despite the fact that many of the authors underline the “positive” effects of policies fostering co-creation or co-production practices (e.g. delivering better outcomes, preventing problems, bringing in more human resources; encouraging self-help and behavior change, supporting better use of scarce resources, growing in social networks to support resilience, improving well-being), there are several potentially negative or unexpected effects to be take into consideration. Among these risks or possible backlash, we recognize that the co-creation or co-production process is a highly time consuming one, which presents a difficulty in keeping the participants (i.e. users and professionals) involved for a long period of time. Moreover, given the fact that the users of a service change over time, it is necessary to involve newcomers in order to maintain a sufficient level of participation.

Secondly, the users or clients that participate are often those in better socio-economic conditions (i.e. middle-class), with high levels of education. So, the co-creation or co-production process can exclude, instead of including, users who are considered “hard-to reach.” Thirdly, public administration officials are usually not willing to adopt innovation in their working procedures, and often use strategies to keep “business as usual” practices. They are aware that innovation often creates “winners” and “losers.” This especially true in the co-creation and co-production framework because it requires a deep mind-set change from the professionals. So, often the public administration sector reacts to these policies merely in a “formal” way, adopting the rhetoric of co-production while trying to carry out their activities as usual.

The success or failure of policies fostering co-creation or co-production is very hard to verify and depends on several factors, the most important of which is the purpose of the policy. What is the main aim of the innovation? To increase the responsibility of the users or clients? Or increase their participation? To enhance the efficiency (i.e. cost reduction) of the public administration? Or the effectiveness (i.e. quality) of the service delivering process? A final point on this topic concerns the complexity of the public administration system, with its hierarchical model of decision-making and the separation between political roles and managerial roles.

In order to be sustainable and scalable, a co-creation or co-production innovation must involve the entire public administration body, from the politicians and top managers, down to the so-called on-the-ground professionals. Needless to say, these actors have different aims and incentives, so it is very difficult to find an equilibrium among their often-conflicting interests.

In any co-creation or co-production practice, there are, at least, three conflicting logics acting in the field: (1) Professional and expert logic versus citizens and layperson logic; (2) Service logic versus workers union and corporative logic; (3) Public administration logic versus third sector and civil society logic. The final result (impact) of applying the co-creation approach in service delivering depends on which logic configuration will be dominant.

Table 3 shows, in a concise way, the different roles of citizens, civil society actors, and civil servants for each stage or phase of the co-creation process.

The activities and principles underpinning co-creation.

| Policy/service development dimensions | Civil Society actors and citizens | Public administration actors | Principles | Activities/roles |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Co-planning Co-design Co-commissioninga |

Users’, clients’ organizations | Mid- to first-line management | Inclusion, Fairness, Social justice |

Assessing needs Designing services |

| Co-governance | Civil society organizations | Politician, Senior-management |

Democracy, participation, Influence, Power balancing, Sensemaking Consensus |

Decision-making about goals, tools and principles |

| Co-management | CSO representatives | Senior-management, mid-management | Effectiveness Efficiency Negotiation |

Organizing and managing services |

| Co-production/co-implementation | Citizens, users, clients | First-line management Front-line workers and professionals |

Innovativeness Effectiveness, Efficacy |

Delivering services |

| Co-evaluation/co-assessment | Non-public actors involved in service delivering | Mid-management and front-line workers and professionals | Meaningfulness Accountability, Transparency |

Learning about service improvement |

| Maintenance Scaling |

All non-public actors (stakeholders) | Front-line workers and professionals Mid-management |

Sustainability Replicability/Transferability |

Implementing learnings, Sharing insights |

-

aBy co-commissioning we mean the involvement of civil society organizations and/or groups of citizens in the definition of the content of the bid/tender through which the PA wants to purchase the supply/provision of a service.

3 Final Remarks

Having reached the end of the analysis process carried out so far, it is possible to draw some conclusions about the relevance of Salamon’s thinking regarding the relationship between government and third sector. The policy lines that seek to implement the so-called Social Investment paradigm do not seem to particularly encourage the participation of civil society actors in the implementation of social policies. Undoubtedly, on the one hand, this approach has the merit of abandoning the neo-liberal framework which influenced public policies but welfare policies in particular as a waste of resources that would be more profitably used in the hands of the market. In doing so, it underlines and emphasizes the investment and productive, value-creating dimension of these policies. On the other hand, the model is mainly located at the macro level, with a particular focus on active labor policies, whereas the involvement of non-profit subjects occurs primarily at the meso level, that is, the implementation of social policies at the local level. Overall, this suggests that the Social Investment model appears to be neutral towards Salamon’s theories.

The New Public Governance approach seems to be more attentive to the involvement of third sector organizations in the implementation of public policies. In fact, in an attempt to overcome the previous model of New Public Management, it shifts the focus of attention from within the public administration to outside it. From intra-organizational relations between the various departments to inter-organizational relations towards a plurality of public, private, for-profit, and non-profit actors who can legitimately contribute to the implementation of social policies; the resulting focus on collaboration is fully consistent with Salamon’s thinking. Thirdly, the more recent co-creation and co-production framework appears to be particularly in line with Salamon’s theories. Despite its recent diffusion in the scientific debate, not to mention the still scarce presence in the public debate, it does not yet allow us to understand the direction in which the approach will evolve. In fact, co-creation can be defined either in competitive terms, where it is understood as a means to reduce the costs of public administration, or in cooperative terms, where it is understood as a tool for expanding the democratic participation of citizens and including their associations in the decision-making process.

In conclusion, it is possible to affirm that Salamon’s intuition and his pioneering approach summarized in the model of third-party government was not only correct but anticipated the evolution that welfare policies have undertaken over the last three decades in Western democracies. This is exemplified by the progressive growth in the involvement of socially oriented private actors (i.e. third sector organizations) in the implementation of public policies, especially at the local level, representing a shift from “government” to “governance.” However, it is also important to recognize that what Salamon referred to with the term “voluntary sector” or “nonprofit sector” has undergone significant changes in the period considered. First of all, as a result of internal differentiation and specialization, the more entrepreneurial part of the sector has grown through the birth and spread of what is now called “social enterprise.” Social enterprises, while being located within the third sector in a broad sense, have constitutive characteristics that are profoundly different from the subjects of traditional philanthropy and organized volunteering. Furthermore, they appear less oriented towards a relationship with the public administration sector than the classical actors of the third sector.

In addition, we must also recognize that the methods and the means of nonprofit-public relationships have evolved greatly in the last thirty years. This increases the complexity and diversification of the concrete forms of implementation that a partnership between the public administration and the third sector can assume. Finally, even the third sector itself has changed significantly, so much so that some of the shortcomings identified by Salamon seem much less concerning today, such as amateurism. Currently, the sector can count on a high professionalization process to which, in addition to the generational turnover of the top management and leadership, led to the establishment of numerous university courses specifically aimed at training the upper and middle management of the nonprofit sector. In summary, we suggest that the theory of “third-party governance” has certainly been successful and has become mainstream in the political and scientific debate, while the theory of “voluntary failure” is less widespread and ultimately overwhelmed by the internal evolution of the sector. The four weaknesses indicated by Salamon – philanthropic insufficiency, philanthropic particularism, philanthropic paternalism, and philanthropic amateurism–made public-private nonprofit collaboration necessary, but they appear less present today. The fall short of characterizing a sector that has evolved both from a managerial dimension and value point of view. Becoming less paternalistic and particularistic but more commercialized and professionalized.

References

A.A.V.V. 2006. Social Silicon Valleys a Manifesto for Social Innovation: What it is, Why it Matters and How it Can be Accelerated. London: The Young Foundation, The Basingstoke Press.Search in Google Scholar

Alford, J. 1998. “A Public Management Road Less Traveled: Clients as Co-producers of Public Services.” Australian Journal of Public Administration 57 (4): 128–37. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8500.1998.tb01568.x.Search in Google Scholar

Bason, C. 2010. Leading Public Sector Innovation: Co-creating for a Better Society. Bristol: Policy Press.10.2307/j.ctt9qgnsdSearch in Google Scholar

Bovaird, T. 2007. “Beyond Engagement and Participation: User and Community Coproduction of Public Services.” Public Administration Review 67 (5): 846–60.10.1111/j.1540-6210.2007.00773.xSearch in Google Scholar

Boyle, D., and M. Harris. 2009. The Challenge of Co-production. London: Nef-Nesta.Search in Google Scholar

Brandsen, T., and V. Pestoff. 2006. “Co-production, the Third Sector and the Delivery of Public Services.” Public Management Review 8: 493–501. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719030601022874.Search in Google Scholar

Brandsen, T., S. Trui, and V. Bram, eds. 2018. Co-production and Co-creation Engaging Citizens in Public Services, New York: Routledge.10.4324/9781315204956Search in Google Scholar

Defourny, J., L. Hulgard, and V. Pestoff, eds. 2014. Social Enterprise and the Third Sector. Changing European Landscapes in a Comparative Perspective. London: Routledge.10.4324/9780203487747Search in Google Scholar

Donati, P. 2015. “Beyond the Traditional Welfare State: “Relational Inclusion” and the New Welfare Society.” AIS – Sezione di Politica sociale Working Papers N. 1. Also available at http://www.ais-sociologia.it/sezioni/ps/working-papers/.Search in Google Scholar

Hemerijck, A. 2002. “The Self-Transformation of the European Social Model(s). In Why We Need a New Welfare State, edited by G. Esping-Andersen, D. Gallie, A. Hemerijck, and J. Myles, Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/0199256438.003.0006Search in Google Scholar

Hemerijck, A. 2007. “Towards Developmental Welfare Recalibration in Europe.” In ISA RC 19th Conference “Social Policy in a Globalizing World”, Florence 6–8 September. WRR.nl – Scientific Council for Government Policy (Latest revision 08-07-2013).Search in Google Scholar

Hemerijck, A. 2012. Changing Welfare States. Oxford: Oxford University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Hemerijck, A. 2012a. When Changing Welfare States and Eurocrisis meet, in “Sociologica”, n. 1 2012. Bologna: Il Mulino.Search in Google Scholar

Hemerijck, A. 2012b. Retrenchment, Redistribution, Capacitating Welfare Provision, and Institutional Coherence After the Eurozone’s Austerity Reflex, in “Sociologica”. n. 1 2012, Bologna: Il Mulino.Search in Google Scholar

Howlett, M., A. Kekez, and O. Poocharoen. 2017. “Understanding Co-production as a Policy Tool: Integrating New Public Governance and Comparative Policy Theory.” Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice 19 (5): 487–501, https://doi.org/10.1080/13876988.2017.1287445.Search in Google Scholar

Jenson, J. 2014. Modernising Paradigms. Social Investments Via Social Innovation, Paper Presented at the International Conference: Towards Inclusive Employment and Welfare Systems: Challenges For a Social Europe, 1–17. Berlin.Search in Google Scholar

Needham, C. 2014. Personalisation, Personal Budgets and Citizenship in English Care Services. in Autonomie Locali e Servizi Sociali, n. 2, 2014, 203–20. Bologna: Il Mulino.Search in Google Scholar

Osborne, S. P., and K. Strokosch. 2013. “It Takes Two to Tango? Understanding the Co-production of Public Services by Integrating the Services Management and Public Administration Perspectives.” British Journal of Management 24: S31–S47. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8551.12010.Search in Google Scholar

Osborne, S. P. 2006. “The New Public Governance?” Public Management Review 8 (3): 377–87, https://doi.org/10.1080/14719030600853022.Search in Google Scholar

Osborne, S. P., ed. 2009. The New Public Governance? Emerging Perspectives on the Theory and Practice of Public Governance. London: Routledge.10.4324/9780203861684Search in Google Scholar

Osborne, S. P., Z. Radnor, and K. Strokosch. 2016. “Co-production and the Co-creation of Value in Public Services: A Suitable Case for Treatment?” Public Management Review 18 (5): 639–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2015.1111927.Search in Google Scholar

Pestoff, V. 2014. “Collective Action and the Sustainability of Co-production.” Public Management Review 16 (3): 383–401. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2013.841460.Search in Google Scholar

Pierson, P. ed. 2001. The New Politics of the Welfare State. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/0198297564.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Piketty, T. 2011. Le capital au xxie siècle. Paris: Éditions du Seuil.Search in Google Scholar

Poocharoen, O., and B. Ting. 2015. “Collaboration, Co-production, Networks: Convergence of Theories.” Public Management Review 17 (4): 587–614. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2013.866479.Search in Google Scholar

Porter Michael, K. M. 2011. “Creating Shared Value. How to Reinvent Capitalism and Unleash a Wave of Innovation and Growth.” Harvard Business Review 89 (1–2): 2–17.Search in Google Scholar

Rajan, R. 2019. The Third Pillar. How Markets and the State Leave the Community Behind. New York: Penguin Books.Search in Google Scholar

Salamon, L. M. 1987a. “Of Market Failure, Voluntary Failure, and Third-Party Government: Toward a Theory of Government-Nonprofit Relations in the Modern Welfare State.” Journal of Voluntary Action Research 16 (1–2): 29–49. Reprinted in Salamon (1995): 33–49. https://doi.org/10.1177/089976408701600104.Search in Google Scholar

Salamon, L. M. 1987b. “Partners in Public Service: The Scope and Theory of Government-Nonprofit Relations,” In The Nonprofit Sector. A Research Handbook, edited by W. Powell Walter, 99–117. New Haven: Yale University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Salamon, L. M. 1989. “The Voluntary Sector and the Future of the Welfare State.” Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 18 (1): 11–24. Reprinted in Salamon (1995): 203–19. https://doi.org/10.1177/089976408901800103.Search in Google Scholar

Salamon Lester, M. and Toepler, S. 2015. “Government–Nonprofit Cooperation: Anomaly or Necessity?” Voluntas 26: 2155–77. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-015-9651-6.Search in Google Scholar

Standing, H. 2004. Definitions, Frameworks and Tools from the Health Sector. London: DFID Health Systems Resource Center.Search in Google Scholar

Torfing, J., E. Sørensen, and A. Røiseland. 2016. “Transforming the Public Sector into an Arena for Co-creation: Barriers, Drivers, Benefits, and Ways Forward.” Administration & Society 51 (5): 1–31.10.1177/0095399716680057Search in Google Scholar

Voorberg, W. H., V. Bekkers, and L. G. Tummers. 2015. “A Systematic Review of Co-creation and Co-production: Embarking on the Social Innovation Journey.” Public Management Review 17 (9): 1333–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2014.930505.Search in Google Scholar

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Lester M. Salamon Memorial Issue, Part II

- Research Articles

- Social Origins Theory: Untapped Potential and the Test by the Pandemic Crisis

- Germany – Still a Welfare Partnership Country?

- Nonprofit–Government Partnership during a Crisis: Lessons from a Critical Historical Junction

- The Relationship Between Public Administration and Third Sector Organizations: Voluntary Failure Theory and Beyond

- Commentary

- Rereading Salamon: Why Voluntary Failure Theory is Not (Really) About Voluntary Failures

- Book Review

- Riccardo Guidi, Ksenija Fonović, and Tania Cappadozzi: Accounting for the Varieties of Volunteering: New Global Statistical Standards Tested

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Lester M. Salamon Memorial Issue, Part II

- Research Articles

- Social Origins Theory: Untapped Potential and the Test by the Pandemic Crisis

- Germany – Still a Welfare Partnership Country?

- Nonprofit–Government Partnership during a Crisis: Lessons from a Critical Historical Junction

- The Relationship Between Public Administration and Third Sector Organizations: Voluntary Failure Theory and Beyond

- Commentary

- Rereading Salamon: Why Voluntary Failure Theory is Not (Really) About Voluntary Failures

- Book Review

- Riccardo Guidi, Ksenija Fonović, and Tania Cappadozzi: Accounting for the Varieties of Volunteering: New Global Statistical Standards Tested