Abstract

The selective broadband absorption of solar radiation plays a crucial role in applying solar energy. However, despite being a decade-old technology, the rapid and precise designs of selective absorbers spanning from the solar spectrum to the infrared region remain a significant challenge. This work develops a high-performance design paradigm that combines deep learning and multi-objective double annealing algorithms to optimize multilayer nanostructures for maximizing solar spectral absorption and minimum infrared radiation. Based on deep learning design, we experimentally fabricate the designed absorber and demonstrate its photothermal effect under sunlight. The absorber exhibits exceptional absorption in the solar spectrum (calculated/measured = 0.98/0.94) and low average emissivity in the infrared region (calculated/measured = 0.08/0.19). This absorber has the potential to result in annual energy savings of up to 1743 kW h/m2 in areas with abundant solar radiation resources. Our study opens a powerful design method to study solar-thermal energy harvesting and manipulation, which will facilitate for their broad applications in other engineering applications.

1 Introduction

The overexploitation of fossil fuels and global warming are significant challenges in our society today. As one of the most promising renewable resources, solar energy has garnered tremendous interest for its potential to address these issues. Among the various studies in this field, solar metamaterial absorbers have shown great promise for converting sunlight into available energy, with potential applications in thermophotovoltaics [1–7], seawater desalination [8–10], and sewage purification [11, 12]. To maximize the utilization of solar energy, it is crucial to establish an ideal solar absorber. According to Wien’s displacement law [13], an ideal solar absorber should have high absorption in the solar spectrum (0.3–2.5 µm) and zero emissivity in the infrared region (2.5–25 µm), preventing heat leakage and optimizing its performance as a photothermal energy conversion device. In essence, solar absorbers must exhibit exceptional spectrum selectivity. In recent years, numerous studies have emerged on the topic of selective solar absorber design. Various structure systems have been proposed for selective solar absorbers, including densely packed nanowires [14], nanotubes [15], nanopillars [16], 1D or 2D gratings [17], sawtooth and pyramid structures [18–23], and different periodic patterns [24–34]. However, these designs primarily rely on brute-force, time-consuming, and inefficient trial-and-error conventional domain-knowledge-driven design strategies, resulting in a suboptimal performance for selective solar absorbers.

Layered film photonic structures offer several advantages for the development of selective solar absorbers, including their simple planar geometry, precisely controllable dimensions, flexibility in combining different materials, and potential for large-scale manufacturing. Several optimization schemes, such as genetic algorithms (GA) [35, 36] and particle swarm algorithms (PSA) [37–39], have been developed and applied to design layered film photonic structures for optical and selective solar absorbers. Up to date, these current optimization methods suffer from several problems: (i) Intelligent optimization algorithms rely on electromagnetic simulation calculations for data acquisition, and higher optimization accuracy requires larger simulation calculations, significantly increasing the optimization process’s time cost; (ii) Popular intelligent optimization algorithms like particle swarm and genetic are prone to settling on local optimal solutions when faced with high-dimensional optimization problems; (iii) Current optimization methods primarily focus on achieving single-objective optimization and are incapable of solving multi-objective optimization problems, such as those found in spectrally selective absorbers. Thus, it remains in-demand to pursue a powerful scheme to accelerate the development of ideal selective solar absorbers.

Here, we report the development of an ideal selective solar absorber (SSA) using a deep-learning (DL) architecture aided by multi-objective double annealing (DA) algorithm optimization scheme. Utilizing the DL architecture, the relationship between complex nanostructure parameters and optical response spectra can be real-time predicted, eliminating iterative and time-consuming calculations. When the DA algorithm is used for the global optimization, the DL network can predict the optical responses in the time scale of millisecond, significantly speeding up design process. The algorithm also offers various candidates, enabling the selection of suitable material and thickness of each layer to meet desired optical experiment requirements. We fabricate a wafer-scale SSA with broadband sunlight absorption via DL architecture aided by multi-objective DA algorithm optimization scheme. The on-site experiments under the sunlight indicate that our SSA is promising for photothermal conversion. Our study provides a powerful design way to develop SSA and various other metamaterial-based applications.

2 Results and discussion

The candidate SSA consists of layered film (LF) photonic structures on a chromium (Cr) substrate with a magnesium fluoride (MgF2) anti-reflection layer (Figure 1A). The low-refractive-index MgF2 layer on top acts as an anti-reflection layer, reducing the reflection of the incident light from the absorber and increasing the amount of light that can enter the absorber, while the Cr substrate acts as an opaque reflector. The LF structure is made of four common metal materials and three common insulator materials, where the ultra-thin metallic layer acts as a translucent mirror together with the lossless insulator layer and the Cr substrate at the bottom to form a metal–insulator–metal–insulator–metal (MIMIM) structure, so their combination has the potential to produce different optical properties (high absorption and low emissivity) in different wavelength regimes. As shown in Figure 1A, the LF structure is divided into 6 layers, metallic layers can be one of the four candidate materials: iron (Fe), titanium (Ti), tungsten (W), and Cr, and insulator layers can be one of the three candidate materials: aluminum oxide (Al2O3), MgF2, and silicon dioxide (SiO2). All metal and insulator layers are set as fixed materials, so there are a total of twelve material combinations. It is designed to absorb the majority of energy from solar radiation while preventing heat leakage through the mid-infrared range (MIR) (Figure 1B). This allows for the efficient coupling of solar and passive heating to maximize the heating effect. Under the classical design framework, such complex combinations require brute-force optimizations with sizable parameter space, which turn out to be rather inefficient and time-consuming.

SSA concept and the DL-aided multi-objective optimization scheme. (A) The schematic structure of the LF in the SSA containing candidate materials. (B) The solar spectrum (air mass 1.5 global), the resultant transmitted irradiance (blue shade), and the absorption/emissivity of an SSA in relevant wavelength regimes. The SSA should have high absorption in the UV to NIR (300−2500 nm) spectrum for solar heating. Additionally, it should have low emissivity in the MIR (2.5–25 μm) for passive heating. (C) Schematic comparison of DL-aided multi-objective DA optimization scheme and current conventional optimization scheme.

With the purpose of overcoming this challenge, we develop a DL-aided multi-objective DA algorithm optimization scheme. The DA algorithm is an extended algorithm based on the traditional simulated annealing algorithm [40]. It uses the annealing procedure from the traditional annealing algorithm and combines the local search algorithm with the global search algorithm. Global search algorithms typically perform well at identifying basins (areas in the search space) where the best solution may be found, but they frequently struggle to find the best solution within the basin. On the other hand, local search algorithms excel at identifying the basin’s ideal value. The DA algorithm can run multiple annealing at the global scale, choose the best result from them, and then recursively run the search again by focusing on that result until the annealing no longer yields an optimal result or the new solution is hardly better superior. In the multi-objective optimization process, the weighted absorption of the solar spectrum (figure-of-merit-1, FOM1) as the main optimization objective and the average MIR emissivity (FOM2) as the constraint. In terms of practical applications, an SSA should possess both high solar spectral absorptance and low thermal emissivity in the infrared region, in accordance with Planck’s law of blackbody radiation. The spectral density of thermal radiation from a blackbody absorber can be defined by [41]:

where λ is the wavelength, T is the absolute temperature of the blackbody absorber, his Planck’s constant, c is the speed of light in the vacuum, and k is the Boltzmann constant. According to the formula, we calculate the irradiance spectra at different temperatures in Figure S1 (Supporting Information). Thus, the FOM1 and FOM2 can be defined as:

where the

Maximizing FOM1 while satisfying the FOM2 constraint is crucial to enable the designed SSA to approach the ideal SSA. The detailed workflow of the multi-objective DA algorithm optimization scheme is illustrated in Figure S2 (Supporting Information). The relationship between the SSA and its FOM is described by a DL network that is trained using a dataset generated by FDTD. The dataset generation process is outlined in Table S1 and Figure S3 (Supporting Information).

The use of DL has brought significant benefits, as demonstrated in Figure 1C. Compared to conventional optimization methods, the DL-aided multi-objective DA optimization scheme drastically reduces the time required for complex simulation calculations, making optimization several orders of magnitude faster, especially when the SSA complexity is high or when multiple optimization objectives are involved.

Here, we utilize DL-aided multi-objective optimization scheme to perform the inverse design of an SSA. Our goal is to achieve maximum absorption in the solar spectrum while minimizing emissivity in the infrared region (Equation (4)).

The most popular DL framework, TensorFlow, was used to build and train the DL Network. 9 parameters are selected as the input parameters vector P = [h1, h2, h3, h4, h5, h6, h7, n m , n i ], including 7-dimensional unit-cell parameters and 2-dimensional material types of those parameters (Figure 2A). Before training, the dataset is randomly divided, with 80 % being used as the training set and 20 % being used as the validation set and the K-fold cross-validation is used for training. During the DL network training, six fully connected layers were used for deep learning training with 32, 64, 128, 256, 512, and 1024 neurons in each hidden layer. Random regularization is added after each layer of the network to deactivate some random neurons in the DL network, which improves the overfitting phenomenon, and the magnitude of regularization increases with the number of network layers. We choose the swish function as the activation function of the hidden layer. In order to obtain a faster convergence speed, we choose the Nadam òptimizer as the backpropagation optimizer. The mean squared error (MSE) between the predictive and actual absorptance is expressed to present the loss function:

where

Optimization of the design process for SSA. (A) The architecture of the DL network. The DL network is composed of an input layer that corresponds to 9 design parameters, 6 hidden layers, and an output layer that corresponds to the 2501 spectral points. The number of neurons in the hidden layers is shown; (B) MSE of training and validation. After 800 epochs, the training and validation losses stabilize at 0.00556 and 0.0054, respectively; (C) optimization of historical FOM1 records of the SSA with three different randomly selected initial values; (D) optimal configuration for the SSA; (E) and (F) represent the absorption/emissivity calculated by the DL network (blue line) and FDTD (red line) in the solar spectrum and infrared region, respectively.

The DA algorithm is utilized for 2000 iterative calculations to obtain the optimal configuration, and the FOM1 of the optimization process is depicted in Figure 2C. Upon optimization to 2000 generations, FOM1 remains at 0.977 and the optimal parameter set is shown in Figure 2B. We have also optimized the LF structure using three different DA algorithms with randomly selected initial values, and in all cases, they converged to the same optimal structure (Figure 2D), although the number of iterations required was different in each case.

The absorption/emissivity calculated by FDTD and DL network for the final optimized structure is shown in Figure 2E and F. The FDTD and DL network results of FOM1 and FOM2 are 0.981/0.977 and 0.087/0.082, respectively. It can be seen that both in the solar spectrum and infrared region, the results calculated by FDTD and generated by the DL network maintain a high degree of agreement.

Based on the above design study, we fabricate the SSA sample and perform the characterization and optical measurement. We have successfully fabricated the designed six-layer absorber (MgF2/Ti/SiO2/Ti/SiO2/Cr) using a high vacuum electron beam evaporation thin film deposition system. Our wafer-scale SSA samples, as shown in Figure 3A, demonstrate this achievement. Furthermore, a cross-section of the fabricated absorber, depicted in Figure 3B through a scanning electron microscope (SEM), clearly shows each layer in sequence. These collective findings establish the successful fabrication of the SSA. The absorption/emissivity of the fabricated SSA calculated by FDTD and experimentally measured are shown in Figure 3C and D. With the best geometrical parameters and material combinations, the designed SSA has high absorption in the solar spectrum (calculate/measure = 0.98/0.94) and low average emissivity in the infrared region (calculate/measure = 0.08/0.19). The comparison between the measured absorption and the numerical simulation demonstrated good agreement, with minor variations potentially attributed to differences in thickness between the simulation and experiment, as well as the accumulated roughness during the fabrication process of the multilayer films leading to discontinuities in the ultrathin Ti layer (see more details in Figure S4, Supporting Information). These results provide further evidence of the success of the SSA design and fabrication. In addition, the designed absorber has an excellent incident-angle rudeness (see more details in Figure S5, Supporting Information).

Morphological and spectral characterization of SSA. (A) A image of SSA made on a 2-inch silicon wafer; (B) the cross-section of the fabricated absorber as seen through SEM; (C) and (D) represent the absorption/emissivity of the fabricated SSA calculated by FDTD (black line) and experimentally measured (red line) in the solar spectrum and infrared region, respectively. The AM1.5 global tilted solar spectrum and atmospheric transparency window are provided as the background.

To further demonstrate the superiority of our designed SSA, we compared its main spectral properties with those of current state-of-the-art solar absorbers, as shown in Table 1. Despite the experimental defect that resulted in a lower FOM than predicted, our fabricated SSA still exhibits the best spectral selectivity among all experimentally demonstrated solar absorbers reported in the literature. This represents a significant improvement over current state-of-the-art solar absorbers.

Performance of the selective absorbers for solar spectral absorption.

| Ref. | [31] | [14] | [43] | [44] | This work |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Material | SiO2/W/Al2O3 | Graphene/SiO2/Ag | TiN/SiNx | AlCrSiO2/TiN | MgF2/Ti/SiO2/Cr |

| Structure | Metamaterial | Metamaterial | Metamaterial | Layered film | Layered film |

| Absorption bandwidth (nm) | 300–2500 | 300–2500 | 250–2250 | 300–2500 | 300–2500 |

| Absorption (%) | 93.2 (calculate) | 85 (measure) | 87 (measure) | ∼92.3 (measure) | 98.1 (calculate) 94.2 (measure) |

| Emission bandwidth (µm) | 2.5–25 | / | 5–13 | 2.5–25 | 2.5–25 |

| Emissivity (%) | 5.8 (calculate) | / | 29 (calculate) | ∼16 (measure) | 8.7 (calculate) 19.7 (measure) |

| Angular stability (Fom1 > 80 %) | ∼75° | >60° | >60° | / | >75° |

| Origin of results | Simulation | Experiment simulation | Simulation | Experiment simulation | Experiment simulation |

| Design scheme | Iterative optimization | Brute-force simulation | Iterative optimization | Brute-force simulation | Deep learning |

-

Note: ‘/’ denotes the absence of relevant research.

The designed absorber exhibits a unique structure and material composition that contributes to its superior spectral properties. Specifically, the low refractive index MgF2 layer on the top acts as an anti-reflection layer, which minimizes the reflection of the incident light and maximizes the light that enters the absorber. The ultra-thin metal Ti [45], with its low-quality factor, serves as a translucent mirror that, in combination with the lossless dielectric SiO2 and the bottom Cr substrate, forms the MIMIM structure. This combination of layers and materials is responsible for the exceptional performance of the absorber. This structure forms two low-quality factor asymmetric Fabry–Perot resonators [46]. The FOM1 of different anti-reflection and bottom layer materials on the absorber performance is shown in Figure S6 (Supporting Information). In order to reveal the physical mechanism of the designed absorber’s ultra-broadband perfect absorption, we calculated the electric field intensity distribution (

Simulated contour plots of (A)

Since the thicker Cr metal layer has no transmitted light and high absorption corresponds to low reflectivity, the mechanism of the designed absorber to achieve broadband absorption can also be investigated by optical admittance diagram at different wavelengths. The optical admittance is the inverse of the impedance, which is expressed by the equation

We further perform a series of on-site experiments to evaluate the application capability of our SSA. The experiments were performed on the roof of the Keli Building of Jimei University, Xiamen, Fujian, China, on September 28, 2022. The illustration and photographs of the heating measurement system used in the experiment are shown in Figure 5A and B, respectively. As shown in Figure 5A, the SSA and the black paint (the spectral properties of black paint are shown in Figure S7, Supporting Information) used as a control group were placed in two separate containers. The container is made of an acrylic box (size: 10 × 10 × 10 cm) with an opening at the top, which is surrounded by Al foil and covered with low-density polyethylene (LDPE) film at the top. Acrylic box can be used as a thermal insulation layer, Al foil can reflect solar radiation, and LDPE film can ensure that as much solar radiation as possible into the interior of the box while reducing the heat convection between the interior of the box and the outside environment, the purpose of this is to reduce the impact of heat convection and heat conduction in the environment on the absorber temperature. The transmittance spectrum of the LDPE film is shown in Figure S8 (Supporting Information). The sample in the container is supported by three wooden needles to reduce heat transfer from the bottom of the box to the sample, and a K-type thermocouple is placed at the bottom of the sample to monitor the real-time temperature. A solar radiation sensor is placed at the same height as the sample to monitor the real-time solar irradiance. The ambient air temperature is extracted from the Xiamen gaoqi international airport station [51].

Schematic (A) and photograph (B) of the outdoor temperature measurement chamber; (C) the measured surface temperature of the two samples as a function of time when exposed on a sunny day in Xiamen, Fujian, China (09:00–17:00, September 28, 2022). The yellow area indicates the measured solar irradiance, corresponding to the right axis. The calculated net power as a function of temperature based on the absorption/emissivity spectra of the simulated (D) and measured (E) results with four different values of heat transfer coefficients.

Figure 5C shows the daytime temperature measurements accompanied by solar irradiance during the period 9:00–17:00. With the increase of solar irradiance, the temperature of both samples gradually increased and the temperature gap between them widened. When the solar irradiance peaked around noon (over 800 W/m2), both the absorber and the black paint also reached their maximum temperatures of 85.16 °C and 78.78 °C, respectively. The temperature of the two samples gradually approaches the ambient temperature as the solar radiance declines. The primary factor causing the temperature difference between the ideal absorber and the black paint is their different optical characteristics. The ideal solar absorber achieves superior warming performance with higher solar absorption and lower infrared emissivity. It is worth noting that the thickness of the ideal absorber is less than 500 nm while the black paint is above 20 µm. As the thickness of the black paint is challenging to control for quantitative analysis, we evaluated the heating performance of the two samples under ideal conditions.

In accordance with the first law of thermodynamics, Pnet can be calculated as follows [42]:

where

denotes the radiation power density by the absorber at a temperature of T s ;

is the absorbed heat flux due to surrounding atmospheric thermal radiation at a temperature of T a ;

denotes the incident solar power absorbed by the absorber;

denotes the power loss caused by conduction and convection between the absorber and the ambient air. Additionally,

With the aim to validate these experimental findings, we evaluated the net power as a function of temperature based on the absorption/emissivity spectra of the simulated (Figure 5D) and measured (Figure 5E) results with four different values of heat transfer coefficients. The solar irradiance and atmospheric transmittance shown in Figure S9A and B (Supporting Information) are used. The net power of the simulated results shows a higher net power than that of the measured results, which matches the averaged optical properties presented in Figure 3. At an ambient temperature of 300 K, the calculated net powers of the simulated and measured results were 861.81 and 807.55 W/m2, respectively. When the net power is equal to zero (Pnet = 0), the absorber reaches the steady-state temperature. The steady-state temperatures at different heat transfer coefficients are shown in Table 2, and the steady-state temperature of the absorber gradually decreases as the heat transfer coefficient increases. The net power of black paint as a function of temperature calculated from its spectral properties is shown in Figure S10 (Supporting Information). Due to the larger emissivity of black paint in the infrared region, excessive heat leakage is generated, which greatly reduces its steady-state temperature. The steady-state temperature of black paint with different heat transfer coefficients is shown in Table S2 (Supporting Information).

The calculated steady-state temperature of SSA under different heat transfer coefficients.

| Steady-state | h c = 0 | h c = 4 | h c = 6 | h c = 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| temperature (Pnet = 0) | ||||

| Simulated result | >500 K | 463 K | 423 K | 397 K |

| Measured result | 495 K | 420 K | 397 K | 380 K |

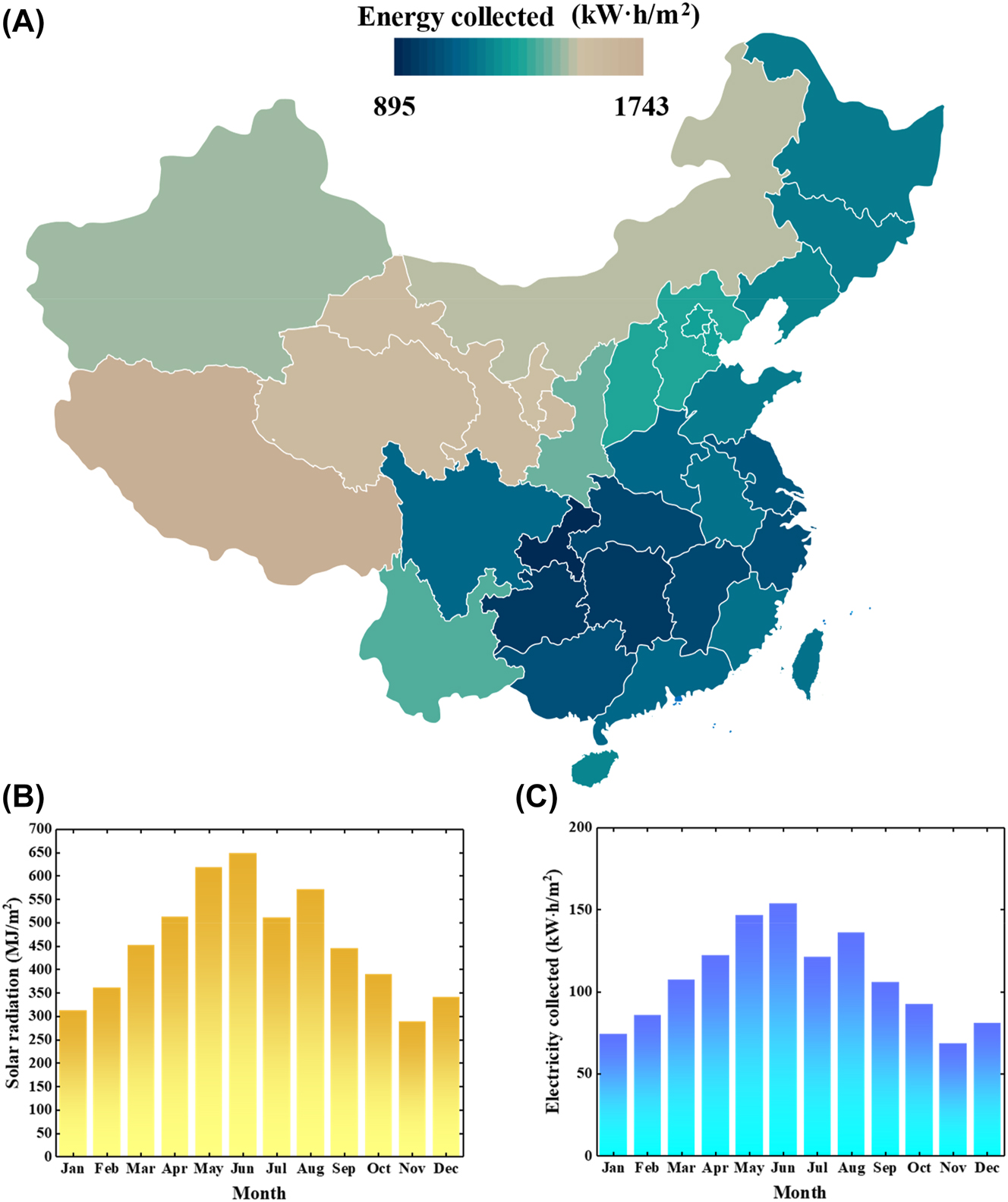

We estimated the benefit of the SSA as a potential absorber material by calculating the energy it can collect, according to the assessment methods in Ref. [52] in Figure 6. The average annual energy collected over the surveyed Chinese provinces is 1461 kW h/m2. In high altitude provinces with hot and dry weather (e.g., Tibet), the SSA can potentially collected ∼1743 kW h/m2 per year (Figure 6A). The same calculation was also performed for the city of Xiamen. We refer to the monthly variation of solar radiation in Xiamen City [53] to objectively estimate the energy collected in Figure 6B, suggesting solar radiation in July is the highest and that in February is the lowest. We plot the estimated energy collected by the SSA every month in Figure 6C. Although this is a rudimentary analysis, it does indicate that more kilowatt hours can be collected in the summer months when there is more abundant solar radiation, and that the scale of the potential annual savings (1295 kW h/m2) is substantial.

Energy harvesting potential of SSA. (A) Estimated energy collected if our designed SSA as a potential absorber material across the China; (B) the monthly variation of solar radiation in Xiamen; (C) electricity (energy) collected spectrum versus months.

3 Conclusions

In conclusion, we have successfully developed a high-performance SSA utilizing a DL- aided multi-objective DA algorithm optimization scheme. Our optimized SSA exhibits superior absorption and spectral selectivity (FOM1 = 0.94, FOM2 = 0.19) compared to other similar absorbers. Through experimental demonstration, we have validated the optical properties and heating performance of our SSA. Simulations based on the measured optical properties have shown the significant potential of our SSA in solar energy harvesting compared to black paint. As the fabrication of the optimized layered photonic structures in the SSA can be achieved using deposition techniques, it can potentially be scaled up for practical applications. Moreover, the DL-aided multi-objective DA algorithm optimization scheme employed in this study can be widely applicable for material design in various fields, including optical, thermal, and mechanical applications of meta-materials.

4 Experimental section

4.1 Numerical simulations

The numerical simulations were calculated with the FDTD Solutions v8.13, Lumerical software. The plane waves along the z-axis propagated to the solar absorber in the simulation. The boundary conditions along the x-axis and y-axis were periodic, and the boundary conditions along the z-axis were perfectly matched layers. In the simulation, the electromagnetic waves were introduced vertically incident on the SSA, and the normalized reflectance was collected with a frequency-domain field and power monitor placed behind the excitation source.

4.2 Data collection

A total of 30,000 samples were collected using a desktop, among which 27,000 were for the training samples, and 3000 were for the testing samples (Windows10 operation system, GeForce RTX 3070 GPU, AMD Ryzen 9 5900HX CPU @ 3.3 GHz and 16 GB of RAM). The geometry ranges can be found in Table S1 (Supporting Information). The model was constructed based on the open-source machine learning framework of TensorFlow. The version used was Python 3.9.

4.3 Training hyperparameters

The hyperparameters of the MLP structure are tuned by the Optuna framework. Optuna is a powerful hyperparameter optimization library that automates the process of finding optimal hyperparameter settings. In the Optuna framework, the range and type of hyperparameters to be adjusted are predefined. This included the number of hidden layers and the number of neurons per layer in the MLP architecture. We set the search space for the number of hidden layers to be from 1 to 8, and the search space for the number of neurons per layer to be (32, 64, 128, 256, 512, 1024, 2048). The performance of the MLP network using a given configuration of hyperparameters was evaluated by using the loss function on the test set as the objective function.

4.4 Sample fabrication

We fabricate the designed six-layer absorber (MgF2/Ti/SiO2/Ti/SiO2/Cr) with the physical vapor deposition method using a high vacuum electron beam evaporation thin film deposition system (DZS-500, Shenyang Scientific Instrument Co., Ltd., China). The evaporation materials, such as 99.99 % MgF2, Ti, SiO2, and Cr pellets, are purchased from ZhongNuo Advanced Material (Beijing) Technology Co., Ltd. Prior to deposition, the silicon substrate (size: 2 inches) is pre-processed in a clean room by ultrasonic cleaning using ethanol, acetone, isopropyl alcohol, and demineralized water, respectively, in sequence. After blowing dry with nitrogen, the silicon substrate adheres to the substrate holder. Throughout the deposition process, 2.0 × 10−4 Pa of pressure was kept in the vacuum chamber. To guarantee the uniformity of the films, the substrate holder was rotated at 15 rpm in a clockwise direction. For MgF2, SiO2, Ti, and Cr, the films’ deposition rates were kept under control at roughly 0.55 Å/s, 0.45 Å/s, 0.4 Å/s, and 0.5 Å/s, respectively. The INFICON STM-2XM thickness detector was used to measure the deposited films’ thickness in real-time.

4.5 Material characterizations

The cross-section morphologies and EDS were characterized by SEM (Sigma 300, Zeiss, Germany).

4.6 Optical characterization

The UV–visible–NIR (0.3–2.5 µm) reflectance (R) spectra of the samples were measured using a spectrometer (Shimadzu UV-3600i Plus) equipped with a 150 mm integrating sphere. The infrared (2.5–25 µm) emissivity of the sample was measured by a Fourier infrared spectrometer (Nicolet iS50, Thermo Scientific, USA) with a gold integrating sphere. The absorptance (A) spectra were directly derived from 1 – R – T. According to Kirchhoff’s law at thermal equilibrium, the spectral emissivity (ε(λ)) and absorptance are equal at any specified temperature and wavelength (ε(λ) = α(λ)) [54, 55].

4.7 Thermal measurement

The outdoor solar radiation intensity Psolar was measured by a photoelectric solar radiation sensor (RS-RA-N01-AL, Shandong Renke Control Technology Ltd. Co., China). The temperature of the sample was measured by a contact thermocouple thermometer (UT325, Uni-Trend Technology Ltd. Co., China).

Supplementary Materials

See Supplementary Materials for supporting content.

Funding source: The National Natural Science Foundation of China

Award Identifier / Grant number: Grant Nos. 51772042, 52021001 and 52022018

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank He Bin from Shiyanjia Lab (www.shiyanjia.com) for the SEM analysis.

-

Research funding: This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 51772042, 52021001 and 52022018).

-

Author contributions: Wen-zhuang Ma: methodology, software, writing–original draft preparation; Wei Chen: investigation; Degui Li, Yue Liu, Juhang Yin, Chunzhi Tu, Yunlong Xia, and Gefei Shen: validation, formal analysis and resources; Peiheng Zhou: investigation; Longjiang Deng: Supervision; Li Zhang: writing–review and editing, funding acquisition. All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest statement: Authors state no conflicts of interest.

-

Data availability: Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

[1] C. Fei Guo, T. Sun, F. Cao, Q. Liu, and Z. Ren, “Metallic nanostructures for light trapping in energy-harvesting devices,” Light Sci. Appl., vol. 3, no. 4, p. e161, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1038/lsa.2014.42.Search in Google Scholar

[2] L. Zhou, Y. Tan, D. Ji, et al.., “Self-assembly of highly efficient, broadband plasmonic absorbers for solar steam generation,” Sci. Adv., vol. 2, no. 4, p. e1501227, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.1501227.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[3] C. Chang, W. J. Kort-Kamp, J. Nogan, et al.., “High-temperature refractory metasurfaces for solar thermophotovoltaic energy harvesting,” Nano Lett., vol. 18, no. 12, pp. 7665–7673, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.nanolett.8b03322.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[4] M. Lim, S. Jin, S. S. Lee, and B. J. Lee, “Graphene-assisted si-insb thermophotovoltaic system for low temperature applications,” Opt. Express, vol. 23, no. 7, pp. A240–A253, 2015. https://doi.org/10.1364/oe.23.00a240.Search in Google Scholar

[5] M. Lim, J. Song, J. Kim, S. S. Lee, I. Lee, and B. J. Lee, “Optimization of a near-field thermophotovoltaic system operating at low temperature and large vacuum gap,” J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transf., vol. 210, pp. 35–43, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jqsrt.2018.02.006.Search in Google Scholar

[6] H. Wang, J. Chang, Y. Yang, and L. Wang, “Performance analysis of solar thermophotovoltaic conversion enhanced by selective metamaterial absorbers and emitters,” Int. J. Heat Mass Tran., vol. 98, pp. 788–798, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2016.03.074.Search in Google Scholar

[7] S. McSherry, M. Webb, J. Kaufman, et al.., “Nanophotonic control of thermal emission under extreme temperatures in air,” Nat. Nanotechnol., vol. 17, no. 10, pp. 1104–1110, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41565-022-01205-1.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] M. Elimelech and W. A. Phillip, “The future of seawater desalination: energy, technology, and the environment,” Science, vol. 333, no. 6043, pp. 712–717, 2011. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1200488.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] Z. Wang, T. Horseman, A. P. Straub, et al.., “Pathways and challenges for efficient solar-thermal desalination,” Sci. Adv., vol. 5, no. 7, p. x763, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aax0763.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[10] Y. Wang, H. Ma, J. Yu, et al.., “All‐dielectric insulated 3D plasmonic nanoparticles for enhanced self‐floating solar evaporation under one sun,” Adv. Opt. Mater., vol. 11, no. 7, p. 2201907, 2023.10.1002/adom.202201907Search in Google Scholar

[11] S. Ma, W. Qarony, M. I. Hossain, C. T. Yip, and Y. H. Tsang, “Metal-organic framework derived porous carbon of light trapping structures for efficient solar steam generation,” Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells, vol. 196, pp. 36–42, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solmat.2019.02.035.Search in Google Scholar

[12] J. Zhang, C. Wang, J. Shi, D. Wei, H. Zhao, and C. Ma, “Solar selective absorber for emerging sustainable applications,” Adv. Energy Sustain. Res., vol. 3, no. 3, p. 2100195, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1002/aesr.202100195.Search in Google Scholar

[13] Y. Tian, X. Liu, F. Chen, and Y. Zheng, “Perfect grating-Mie-metamaterial based spectrally selective solar absorbers,” OSA Contin., vol. 2, p. 3223, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1364/osac.2.003223.Search in Google Scholar

[14] A. Ghobadi, S. A. Dereshgi, H. Hajian, et al.., “97 percent light absorption in an ultrabroadband frequency range utilizing an ultrathin metal layer: randomly oriented, densely packed dielectric nanowires as an excellent light trapping scaffold,” Nanoscale, vol. 9, no. 43, pp. 16652–16660, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1039/c7nr04186a.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[15] M. Farhat, T. Cheng, K. Le, M. M. Cheng, H. Bağcı, and P. Chen, “Mirror-backed dark alumina: a nearly perfect absorber for thermoelectronics and thermophotovotaics,” Sci. Rep., vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 1–11, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep19984.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[16] H. Liu, Z. Ma, C. Zhang, Q. Ai, M. Xie, and X. Wu, “Optical properties of hollow plasmonic nanopillars for efficient solar photothermal conversion,” Renewable Energy, vol. 208, pp. 251–262, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2023.03.060.Search in Google Scholar

[17] H. Lin, B. C. Sturmberg, K. Lin, et al.., “A 90-nm-thick graphene metamaterial for strong and extremely broadband absorption of unpolarized light,” Nat. Photonics, vol. 13, no. 4, pp. 270–276, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41566-019-0389-3.Search in Google Scholar

[18] L. Mo, L. Yang, A. Nadzeyka, S. Bauerdick, and S. He, “Enhanced broadband absorption in gold by plasmonic tapered coaxial holes,” Opt. Express, vol. 22, no. 26, pp. 32233–32244, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1364/oe.22.032233.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[19] R. Piao and D. Zhang, “Ultra-broadband perfect absorber based on nanoarray of titanium nitride truncated pyramids for solar energy harvesting,” Phys. E Low-Dimens. Syst. Nanostruct., vol. 134, p. 114829, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physe.2021.114829.Search in Google Scholar

[20] H. Wang and L. Wang, “Perfect selective metamaterial solar absorbers,” Opt. Express, vol. 21, no. 106, pp. A1078–A1093, 2013. https://doi.org/10.1364/oe.21.0a1078.Search in Google Scholar

[21] H. Liu, M. Xie, Q. Ai, and Z. Yu, “Ultra-broadband selective absorber for near-perfect harvesting of solar energy,” J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transf., vol. 266, p. 107575, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jqsrt.2021.107575.Search in Google Scholar

[22] B. Zhang, C. Jiang, and Z. Zhou, “A three-material chimney-like absorber with a sharp cutoff for high-temperature solar energy harvesting,” Sol. Energy, vol. 232, pp. 92–101, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solener.2021.12.050.Search in Google Scholar

[23] F. Ding, Y. Jin, B. Li, H. Cheng, L. Mo, and S. He, “Ultrabroadband strong light absorption based on thin multilayered metamaterials,” Laser Photon. Rev., vol. 8, no. 6, pp. 946–953, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1002/lpor.201400157.Search in Google Scholar

[24] J. Liu, W. Ma, W. Chen, et al.., “Numerical analysis of an ultra-wideband metamaterial absorber with high absorptivity from visible light to near-infrared,” Opt. Express, vol. 28, no. 16, pp. 23748–23760, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1364/oe.399198.Search in Google Scholar

[25] Y. Zhou, Z. Qin, Z. Liang, et al.., “Ultra-broadband metamaterial absorbers from long to very long infrared regime,” Light Sci. Appl., vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 1–12, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41377-021-00577-8.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[26] J. Wu, Y. Sun, B. Wu, C. Sun, and X. Wu, “Broadband and wide-angle solar absorber for the visible and near-infrared frequencies,” Sol. Energy, vol. 238, pp. 78–83, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solener.2022.04.032.Search in Google Scholar

[27] C. Sun, H. Liu, B. Yang, K. Zhang, B. Zhang, and X. Wu, “An ultra-broadband and wide-angle absorber based on a TiN metamaterial for solar harvesting,” Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys., vol. 25, no. 1, pp. 806–812, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1039/d2cp04976g.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[28] D. Song, K. Zhang, M. Qian, Y. Liu, X. Wu, and K. Yu, “Ultra-broadband perfect absorber based on titanium nanoarrays for harvesting solar energy,” Nanomaterials, vol. 13, no. 1, p. 91, 2022. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano13010091.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[29] Y. Zou, X. Li, L. Yang, B. Zhang, and X. Wu, “Efficient direct absorption solar collector based on hollow TiN nanoparticles,” Int. J. Therm. Sci., vol. 185, p. 108099, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijthermalsci.2022.108099.Search in Google Scholar

[30] H. Liu, K. Yu, K. Zhang, Q. Ai, M. Xie, and X. Wu, “Pattern-free solar absorber driven by superposed Fabry–Perot resonances,” Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys., vol. 25, no. 15, pp. 10628–10634, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1039/d3cp00325f.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[31] T. Søndergaard, S. M. Novikov, T. Holmgaard, et al.., “Plasmonic black gold by adiabatic nanofocusing and absorption of light in ultra-sharp convex grooves,” Nat. Commun., vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 1–6, 2012. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms1976.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[32] M. Lobet, M. Lard, M. Sarrazin, O. Deparis, and L. Henrard, “Plasmon hybridization in pyramidal metamaterials: a route towards ultra-broadband absorption,” Opt. Express, vol. 22, no. 10, pp. 12678–12690, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1364/oe.22.012678.Search in Google Scholar

[33] J. Liu, W. Chen, Y. Chen, M. P. Houng, and C. F. Yang, “Numerical study on extinction performance of Ag nanoparticles@SiO2 ellipsoid,” J. Mater. Res. Technol., vol. 9, no. 3, pp. 6723–6732, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmrt.2020.04.076.Search in Google Scholar

[34] G. Hou, Z. Lin, Q. Wang, Y. Zhu, J. Xu, and K. Chen, “Integrated silicon-based spectral reshaping intermediate structures for high performance solar thermophotovoltaics,” Sol. Energy, vol. 249, pp. 227–232, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solener.2022.11.026.Search in Google Scholar

[35] H. Cai, M. Wang, Z. Wu, X. Wang, and J. Liu, “Design of multilayer planar film structures for near-perfect absorption in the visible to near-infrared,” Opt. Express, vol. 30, no. 20, pp. 35219–35231, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1364/oe.469855.Search in Google Scholar

[36] W. Zhang, H. Qi, Z. Yu, M. He, Y. Ren, and Y. Li, “Optimization configuration of selective solar absorber using multi-island genetic algorithm,” Sol. Energy, vol. 224, pp. 947–955, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solener.2021.06.059.Search in Google Scholar

[37] J. Liu, C. Dou, W. Chen, et al.., “Inverse design a patternless solar energy absorber for maximizing absorption,” Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells, vol. 244, p. 111822, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solmat.2022.111822.Search in Google Scholar

[38] R. Yan, T. Wang, X. Jiang, et al.., “Design of high-performance plasmonic nanosensors by particle swarm optimization algorithm combined with machine learning,” Nanotechnology, vol. 31, no. 37, p. 375202, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6528/ab95b8.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[39] Z. H. Ruan, Y. Yuan, X. X. Zhang, Y. Shuai, and H. P. Tan, “Determination of optical properties and thickness of optical thin film using stochastic particle swarm optimization,” Sol. Energy, vol. 127, pp. 147–158, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solener.2016.01.027.Search in Google Scholar

[40] M. Steinbrunn, G. Moerkotte, and A. Kemper, “Heuristic and randomized optimization for the join ordering problem,” VLDB J., vol. 6, no. 3, pp. 191–208, 1997. https://doi.org/10.1007/s007780050040.Search in Google Scholar

[41] M. J. Moghimi, G. Lin, and H. Jiang, “Broadband and ultrathin infrared stealth sheets,” Adv. Eng. Mater., vol. 20, no. 11, p. 1800038, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1002/adem.201800038.Search in Google Scholar

[42] A. Addeo, E. Monza, M. Peraldo, et al.., “Selective covers for natural cooling devices,” Il Nuovo Cimento C, vol. 1, no. 5, pp. 419–429, 1978. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02507668.Search in Google Scholar

[43] S. Wu, Y. Ye, Z. Jiang, T. Yang, and L. Chen, “Large‐area, ultrathin metasurface exhibiting strong unpolarized ultrabroadband absorption,” Adv. Opt. Mater., vol. 7, no. 24, p. 1901162, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1002/adom.201901162.Search in Google Scholar

[44] D. Yang, X. Zhao, Y. Liu, et al.., “Enhanced thermal stability of solar selective absorber based on nano-multilayered alcrsio films,” Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells, vol. 207, p. 110331, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solmat.2019.110331.Search in Google Scholar

[45] L. Lei, S. Li, H. Huang, K. Tao, and P. Xu, “Ultra-broadband absorber from visible to near-infrared using plasmonic metamaterial,” Opt. Express, vol. 26, no. 5, pp. 5686–5693, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1364/oe.26.005686.Search in Google Scholar

[46] D. Zhao, L. Meng, H. Gong, et al.., “Ultra-narrow-band light dissipation by a stack of lamellar silver and alumina,” Appl. Phys. Lett., vol. 104, no. 22, p. 221107, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4881267.Search in Google Scholar

[47] A. Ghobadi, H. Hajian, S. A. Dereshgi, B. Bozok, B. Butun, and E. Ozbay, “Disordered nanohole patterns in metal-insulator multilayer for ultra-broadband light absorption: atomic layer deposition for lithography free highly repeatable large scale multilayer growth,” Sci. Rep., vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 1–10, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-15312-w.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[48] M. Chirumamilla, A. S. Roberts, F. Ding, et al.., “Multilayer tungsten-alumina-based broadband light absorbers for high-temperature applications,” Opt. Mater. Express, vol. 6, no. 8, pp. 2704–2714, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1364/ome.6.002704.Search in Google Scholar

[49] B. Tang, Y. Zhu, X. Zhou, L. Huang, and X. Lang, “Wide-angle polarization-independent broadband absorbers based on concentric multisplit ring arrays,” IEEE Photon. J., vol. 9, no. 6, pp. 1–7, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1109/jphot.2017.2761799.Search in Google Scholar

[50] C. Ji, Z. Zhang, T. Masuda, Y. Kudo, and L. J. Guo, “Vivid-colored silicon solar panels with high efficiency and non-iridescent appearance,” Nanoscale Horiz., vol. 4, no. 4, pp. 874–880, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1039/c8nh00368h.Search in Google Scholar

[51] Xiamen, Fujian , People's Republic of China Weather History, Xiamen Gaoqi International Airport Station, 2022. Available at: https://www.wunderground.com/history/daily/cn/xiamen/ZSAM/date/2022-9-28.Search in Google Scholar

[52] Y. Tian, X. Liu, A. Ghanekar, and Y. Zheng, “Scalable-manufactured metal–insulator–metal based selective solar absorbers with excellent high-temperature insensitivity,” Appl. Energy, vol. 281, p. 116055, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2020.116055.Search in Google Scholar

[53] Y. M. Wang, W. J. Wu, and Z. F. Tang, “Evaluation of solar energy resources and analysis of solar energy application potential in Xiamen,” in The 32nd Annual Meeting of Chinese Meteorological Society, 2015.Search in Google Scholar

[54] A. P. Raman, M. A. Anoma, L. Zhu, E. Rephaeli, and S. Fan, “Passive radiative cooling below ambient air temperature under direct sunlight,” Nature, vol. 515, no. 7528, pp. 540–544, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature13883.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[55] W. Chen, Y. Gao, Y. Y. Li, et al.., “Broadband solar metamaterial absorbers empowered by transformer‐based deep learning,” Adv. Sci., vol. 10, no. 13, p. 2206718, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1002/advs.202206718.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Supplementary Material

This article contains supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/nanoph-2023-0291).

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Annular pupil confocal Brillouin–Raman microscopy for high spectral resolution multi-information mapping

- Diffractive light-trapping transparent electrodes using zero-order suppression

- Surface lattice resonances for beaming and outcoupling green μ LEDs emission

- Tight focusing field of cylindrical vector beams based on cascaded low-refractive index metamaterials

- Concept of inverted refractive-index-contrast grating mirror and exemplary fabrication by 3D laser micro-printing

- Deep learning empowering design for selective solar absorber

- Compact slow-light waveguide and modulator on thin-film lithium niobate platform

- Passive nonreciprocal transmission and optical bistability based on polarization-independent bound states in the continuum

- Learning flat optics for extended depth of field microscopy imaging

- Polarization-independent achromatic Huygens’ metalens with large numerical aperture and broad bandwidth

- Squaraine nanoparticles for optoacoustic imaging-guided synergistic cancer phototherapy

- Programmable metasurface for front-back scattering communication

- Two-photon interference from silicon-vacancy centers in remote nanodiamonds

- PVA-assisted metal transfer for vertical WSe2 photodiode with asymmetric van der Waals contacts

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Annular pupil confocal Brillouin–Raman microscopy for high spectral resolution multi-information mapping

- Diffractive light-trapping transparent electrodes using zero-order suppression

- Surface lattice resonances for beaming and outcoupling green μ LEDs emission

- Tight focusing field of cylindrical vector beams based on cascaded low-refractive index metamaterials

- Concept of inverted refractive-index-contrast grating mirror and exemplary fabrication by 3D laser micro-printing

- Deep learning empowering design for selective solar absorber

- Compact slow-light waveguide and modulator on thin-film lithium niobate platform

- Passive nonreciprocal transmission and optical bistability based on polarization-independent bound states in the continuum

- Learning flat optics for extended depth of field microscopy imaging

- Polarization-independent achromatic Huygens’ metalens with large numerical aperture and broad bandwidth

- Squaraine nanoparticles for optoacoustic imaging-guided synergistic cancer phototherapy

- Programmable metasurface for front-back scattering communication

- Two-photon interference from silicon-vacancy centers in remote nanodiamonds

- PVA-assisted metal transfer for vertical WSe2 photodiode with asymmetric van der Waals contacts