Abstract

The proficiency in vernacular has long been a methodological ethos pervasive among field researchers and—despite new dynamics of fieldwork—still overshadows discussions related to collaboration with translators and interpreters, which are either marginalized or hidden within the category of a ‘research assistant’. The purpose of this study is to take a step beyond anecdotal evidence and explore trends in language proficiency and use of translation services among US based field researchers who had conducted international or domestic studies in an area where a language other than English was present. We conducted the largest-to-date survey on the subject and analyzed 913 responses from faculty at sociology and anthropology programs in the United States. We documented their global fieldwork activity and found only limited proficiency in field languages accompanied by a proliferation of reliance on translators and interpreters, not matching any methodological discussion present in the textbooks and other scholarly sources. We indicate disparities in the use of vernacular and translation services in the post-colonial societies and point out related ethical and methodological concerns. Furthermore, we analyze the researchers’ decision-making processes and their general perspectives on the importance of vernacular’s knowledge and opinions on the admissibility of translators in the fieldwork.

1 Introduction

Traditionally, the question of language as a tool in fieldwork has been central for anthropology and can be traced back to Malinowski (1989), who during his groundbreaking fieldwork in Melanesia described how his ethnological explorations suffered due to his lack of knowledge of Motu. In the end, Malinowski learned the dialect of the Trobriand Islanders (Kiriwinan) and produced Argonauts of the Western Pacific (Malinowski 1984 [1922]), which became an exemplar on how to undertake social anthropology. However, it would be one of Malinowski’s colleagues, Evans-Pritchard (1951) who would lay out the party line among anthropologists concerning fluency and interpreters:

It is obvious that if the anthropologist is to carry out his work […] he must learn the native language, and any anthropologist worth his salt will make the learning of it his first task and will altogether, even at the beginning of his study, dispense with interpreters […] To understand a people’s thought, one has to think in their symbols (Evans-Pritchard 1951: 77–80).

Mead (1939) and Lowie (1940) debated the merits and demerits of the argument, but for the most part, anthropologists did not disagree with Evans-Pritchard’s position. Both Malinowski’s Argonauts (1984 [1922]) and Evans-Pritchard’s Social Anthropology (1951) have been augmented by modern reflexive ethnographies (e.g., Rabinow 1977) and ethnographic/mixed-methods books (Bernard 2006; Bryman 2016) yet we still find scant elaboration on methods to acquire linguistic fluency. Perhaps, as Borchgrevink (2003: 96) suggests, this lack of attention may be due to anthropologists’ fears of losing ethnographic authority. Mead (1939) was among the few to advertise her linguistic deficiencies during fieldwork, a courageous decision in the light of the standards then being upheld by her contemporaries such as Evans-Pritchard (1951). The reticence to acknowledge linguistic incompetence is perhaps understandable given the ways it can mar analysis. For example, although few scholars in anthropology were as eminent as the late Barth, the analysis he provided in his study of Swat Pathans (Barth 1959) demonstrably suffered from a skewed view of political leadership because he did not understand the local language, and instead relied on high-caste interpreters who had their own interests to maintain. Mead herself was subject to stinging criticism suggesting that her fieldwork was superficial, in part due to her linguistics deficiencies (see Freeman 1983). Meanwhile, Chagnon wasted many months analyzing the fictitious and scatological “names” of Yanomamo villagers presented to him by amused tribesmen in what must have been one of the longest running gags in the ethnological record (see Chagnon 1992).

With time, languages have become a research tool also for other social scientists, including sociologists who now work in culturally diverse settings and face the same methodological issues as anthropologists a century ago. Nevertheless, social sciences did not invest in discussing the language and translation in fieldwork, and this omission was noted only by few social scientists (Birbili 2000; Bradby 2002; Gibb and Iglesias 2016; Palmary 2011; Temple 1997) mostly located in Europe, and especially in the United Kingdom. In American sociology, the neglect is closely related to the roots of the discipline focused on American society. It was assumed that issues such as language or intercultural research did not form the central focus of the field, hence no methodology was established (Useem 2019 [1963]). However, even among the founders of American sociology, like Thomas and Znaniecki, the reliance on foreign language proficiency and translation was central to the success of their studies of immigrant communities. Thomas didn’t disregard the collaboration with local translators when learning language in Poland (Bulmer 1984; Sinatti 2008) and one of the initial tasks Znaniecki undertook once in the US was translation and data collection from Polish immigrants (Chalasinski 1963).

As pointed out by Sinatti (2008), that approach adopted by the two prominent sociologists resembles, in its interdisciplinarity, contemporary transnational research. In fact, nowadays, development, disaster, and migration studies are where the issues of language seem to be most present in the methodological consciousness not only among anthropologists, but also among representatives of disciplines traditionally more distant from those discussions. Even there, an awkward intrusion of a linguistically incompetent American researcher who consumes local resources in poor communities is at the center stage of ethical discussions, and skewed power relations also remain a point of contestation in the arena of participatory research (Gaillard and Peek 2019; Scheyvens and Storey 2014). A prevalent lack of discussion regarding the skills and education needed to perform translation and interpreting duties is especially worrying in the most recent methodological notes reclaiming the status and complexities of collaboration with research assistants. To the contrary, a blatant disregard could even be noticed as in the following example: “Research assistants play a vital role in the research process, often acting as more than just [! – exclamation added] translators or interpreters” (Deane and Stevano 2016).

Naturally, the issues of language and culture have always been of interest in Translation Studies, where the questions of interpreter’s role, cultural factors, finding equivalence, and translation strategies have been extensively analyzed (see Baker 1981; Baker et al. 1991; Freed 1988; Newmark 1988). With time, scholars broke the discussion of interpreters as mediators to very specific social contexts such as court interpreting (Pym 1999), healthcare settings (Angelelli 2004), police interviewing (Berk-Seligson 2000), or immigration hearings (Lai and Mulayim 2010). Therein, attempts at elaborating guidelines were made and could potentially be extended to cross-language fieldwork research, such as a prior discussion with the interpreter (Baker 1981), an evaluation following the interview (Baker et al. 1991; Freed 1988), a triangular seating arrangement (Freed 1988), or depending on the purpose of the interview, a decision on ‘matching’ interpreter(s) and participants with respect to ethnicity, gender, age and other characteristics that otherwise can interfere with the goal of the interview (Baker et al. 1991; Murray and Wynne 2001). Unfortunately, scholars point out an omnipresent detachment of their theories from professional practice (Bajčić and Dobrić Basaneže 2016). Not only are those suggestions not implemented, but more importantly, agents prefer to resort to bilingual personnel, who often lack appropriate training or skills instead of professional interpreters. As a result, even though recent decades have witnessed professionalization of translators, either with university degrees, specialized trainings and certificates, or professional associations, the role and status of trained interpreters are still highly marginalized. This is especially troubling in the US, as “the Americans are among the least likely in the world to speak another language” (Stein-Smith 2016, p. v) and a Gallup poll points out that only “25% of Americans possess the ability to conduct a conversation in a language other than English. When immigrants, their children, and other heritage language speakers are subtracted, that leaves 10% of Americans with foreign language skills” (Stein-Smith 2016: 3). The US foreign language deficit is deeply rooted in the history and culture of the country (Brecht 2015; Stein-Smith 2016), both factors which earned the country the reputation of “graveyard of languages” in the 20th century (Rumbaut 2009). Among those already mentioned, Brecht (2015) adds other persisting challenges, such as no national foreign-language mandate at any level of education, no equal access as language education seems to be limited to more “privileged” institutions, and finally cost and budget constraints. The job market does not help with a demand either as only 36% of Americans reported that knowing a foreign language was an extremely or very important trait for workers to be successful in today’s economy, ranking it last out of eight skills for workers’ success (Devlin 2016).

To juxtapose those daunting statistics, U.S. scholars maintain a high level of engagement in international fieldwork and also need to make sure that diverse domestic communities with over five million Limited English Language Households, as well as immigrants, refugees and asylum seekers do not remain under-researched (American Community Survey 2019). Yet, the major scholarly associations and research methods textbooks are collectively mum on the topic and previous discussions are based on scarcely shared individual experiences, lacking a broader analysis that could support applicable ethical and methodological guidelines. Furthermore, recent discussions that duly revindicate the role of research assistant in the fieldwork tend to fold any translation and interpreting skills and roles within the broad spectrum of a research assistant duties (compare Deane and Stevano 2016; Molony and Hammett 2007; Sukarieh and Tannock 2019), with only scarce authors invoking specific skills and education needed for those roles (Turner 2010). This unfortunate approach adds to the invisibility and marginalization of translators, and contrasts with the common understanding of “(…) the language itself as a data resource” (Mendoza and Moren-Alegret 2013: 767) in the social science. Thus, the main objective of this study is to shed light on the trends in linguistic proficiency of the US-based field researchers and an extent of their collaboration with translators and interpreters worldwide. We analyze data from a broad spectrum of US scholars that go beyond individual or anecdotal fieldwork accounts, and we also attempt to provide a context to decisions made across a variety of regions, communities, languages, field situations and settings, some of them accessed by only few experts. Hence, we have undertaken the largest to date survey of American anthropologists and sociologists focused on the presence and use of languages, as well as collaboration with interpreters and translators[1] in domestic and international field sites with language(s) other than English present.

2 Method

2.1 Sample

To accomplish the above-mentioned objectives, we decided to gather input from scholars with potentially the most linguistically and geographically diverse fieldwork experiences. That led us to focus our study on the faculty based at the highest ranked academic programs. While recognizing the flaws of academic rankings, we assume that those institutions provide access to more resources and host scholars with long lasting fieldwork careers, allowing us to collect data on their extensive experience. Accordingly, we focused our study on the faculty based at all the sociology and anthropology programs from the U.S. universities listed among the 1,000 highest ranked worldwide according to the QS World University Rankings from 2018.[2] In particular, to compose the sampling frame, we visited the websites of 94 sociology and 85 anthropology programs based at US Higher Education Institutions that fulfilled the above mentioned criterium and compiled a list of 2,260 faculty of anthropology and 2,479 faculty of sociology programs, not discriminating their ranks/appointments to collect as diverse voices as possible.

This sampling strategy comes with a set of challenges and limitations. First, it is not fully representative of US based anthropologists and sociologists, as voices of faculty from smaller or lower-ranked institutions are missing from our analysis. A follow-up study comparing other types of higher education institutions with potentially different, but equally valuable dynamics of research activity could hopefully close this gap. Furthermore, the process of compiling a sampling frame was beset with difficulties like incomplete/outdated faculty profiles. Accordingly, we included all faculty listed, and introduced a filter question inquiring whether our subjects had conducted any field research (fieldwork, ethnography, interview, excavation, etc.) in an environment where a language other than English was present. As a result, 4,438 invitation e-mails were successfully delivered,[3] and 913 anonymous responses (20% response rate) received from those who responded affirmatively to the filter question and consented to participate in the study. A comparison of academic ranks shows relative coherency between the sample and sampling frame with a slight oversampling of active Full Professors and underrepresentation of Emeritus, Teaching and Adjunct faculty. Furthermore, over a quarter were sociologists and over a half were anthropologists, indicating a higher response rate among the latter as expected considering their traditional research interests (Table 1).

Basic professional characteristics of the sample and sampling frame by discipline.

| Discipline | Anthropology | Sociology | Other | No answer | Total | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data source | Sample | Sampling frame | Sample | Sampling frame | Sample | Sample | Sample | Sampling frame | ||

| Discipline count | N | 511 | 2,260 | 235 | 2,479 | 74 | 93 | 913 | 4,739 | |

| % | 56.0 | 47.7 | 25.7 | 52.3 | 8.1 | 10.2 | 100 | 100 | ||

| Current rank | Full Professor | % | 38.7 | 32.3 | 45.5 | 41.1 | 44.6 | 18.3 | 38.9 | 36.9 |

| Associate Professor | % | 22.3 | 23.8 | 23.8 | 22.5 | 24.3 | 4.3 | 21.0 | 23.1 | |

| Assistant Professor | % | 17.6 | 16.4 | 18.3 | 18.2 | 16.2 | 6.5 | 16.5 | 17.3 | |

| Emeritus faculty | % | 7.6 | 10.2 | 4.3 | 5.4 | 6.8 | 1.1 | 6.0 | 7.7 | |

| Full time teaching | % | 4.3 | 5.1 | 2.1 | 6.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3.0 | 6.0 | |

| Full time research | % | 3.7 | 1.9 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 4.1 | 2.2 | 3.0 | 1.6 | |

| Adjunct faculty | % | 3.1 | 4.7 | 2.1 | 1.7 | 1.4 | 0.0 | 2.4 | 3.1 | |

| Other | % | 2.5 | 5.7 | 2.1 | 2.9 | 2.7 | 2.2 | 2.4 | 4.2 | |

| No answer | % | 0.0 | 0.4 | 0.0 | 65.6 | 6.8 | ||||

| Years in academia | N | 496 | 229 | 70 | 27 | 822 | ||||

| Mean | 22.5 | 21.2 | 23.7 | 22.7 | 22.2 | |||||

| SD | 13.7 | 13.3 | 14.6 | 10.8 | 13.6 | |||||

| Range | 59 | 58 | 52 | 35 | 59 | |||||

To evaluate sample representativeness, we compare characteristics (Table 2) to data provided by the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS) 2018 survey for all the 94 sampled institutions. Still, IPEDS does not break down its data by academic programs or units, and there is no other authoritative data source on the matter. Thus, to provide a comparison closer to the anthropology and sociology disciplines we used the American Anthropological Association (AAA) (American Anthropological Association 2020) Survey of Departments, as well as the American Sociological Association (ASA) (American Sociological Association 2021a, 2021b) regular membership and Guide to Graduate Departments data. The IPEDS based comparison shows that our sample moderately underrepresents male and Asian faculty, and slightly overrepresents white faculty. Some of those variations are to be expected due to the differences between the social sciences and STEM gender profiles of faculty. On the other hand, less precise, but discipline relevant data from the AAA and ASA show their gender profiles as similar to the sample with only a slight underrepresentation of female faculty in our sample. Comparative racial/ethnic data is limited, but our sample closely approaches ASA profiles with the exceptions of underrepresented African American and overrepresented “other” categories.

Demographics of the sample compared to 2018 IPEDS survey for the 94 sampled institutions, and discipline data provided by the 2019 AAA Survey of Departments, the ASA 2018 regular membership profile (M), the ASA 2021 Guide to Graduate Departments data for 2019–2020 (D).

| Discipline | Anthropology | Sociology | Other | No answer | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data source | Sample | AAA | Sample | ASA | Sample | Sample | Sample | IPEDS | ||

| Age | N | 468 | 217 | 68 | 21 | 774 | ||||

| Mean | 54.5 | 53.4 | 56.9 | 55.1 | 54.4 | |||||

| SD | 13.6 | 13.8 | 16.2 | 12.6 | 13.9 | |||||

| Range | 61.0 | 59.0 | 59.0 | 39.0 | 66.0 | |||||

| Gender | Female | % | 49.3 | 52.5 | 52.8 | 55.4M | 41.9 | 8.6 | 45.5 | 43.4 |

| Male | % | 47.4 | 46.0 | 43.3M | 54.1 | 19.4 | 44.7 | 56.6 | ||

| Other | % | 1.4 | 0.4 | 1.2M | 0.0 | 1.1 | 1.0 | |||

| No answer | % | 2.0 | 0.9 | 4.1 | 71.0 | 8.9 | ||||

| Race/ethnicity | White | % | 76.9 | 70.2 | 68.8M | 73.0 | 22.6 | 69.3 | 63 | |

| 69.0D | ||||||||||

| Persons of color | % | 16.7 | 31.2M | |||||||

| Other | % | 10.0 | 8.5 | 2.0D | 6.8 | 0.0 | 8.3 | 11 | ||

| Asian | % | 2.3 | 7.7 | 9.0D | 5.4 | 2.2 | 3.9 | 12 | ||

| Hispanic/Latino(a) | % | 2.5 | 6.0 | 7.0D | 4.1 | 2.2 | 3.5 | 4.6 | ||

| Black or African American | % | 1.4 | 5.5 | 9.0D | 5.4 | 1.1 | 2.7 | 4.0 | ||

| American Indian or Alaska Native | % | 1.6 | 0.4 | 1.0D | 0.0 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 0.3 | ||

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | % | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | |||

| No answer | % | 5.1 | 1.7 | 4.0D | 5.4 | 71.0 | 11.0 | 5.0 | ||

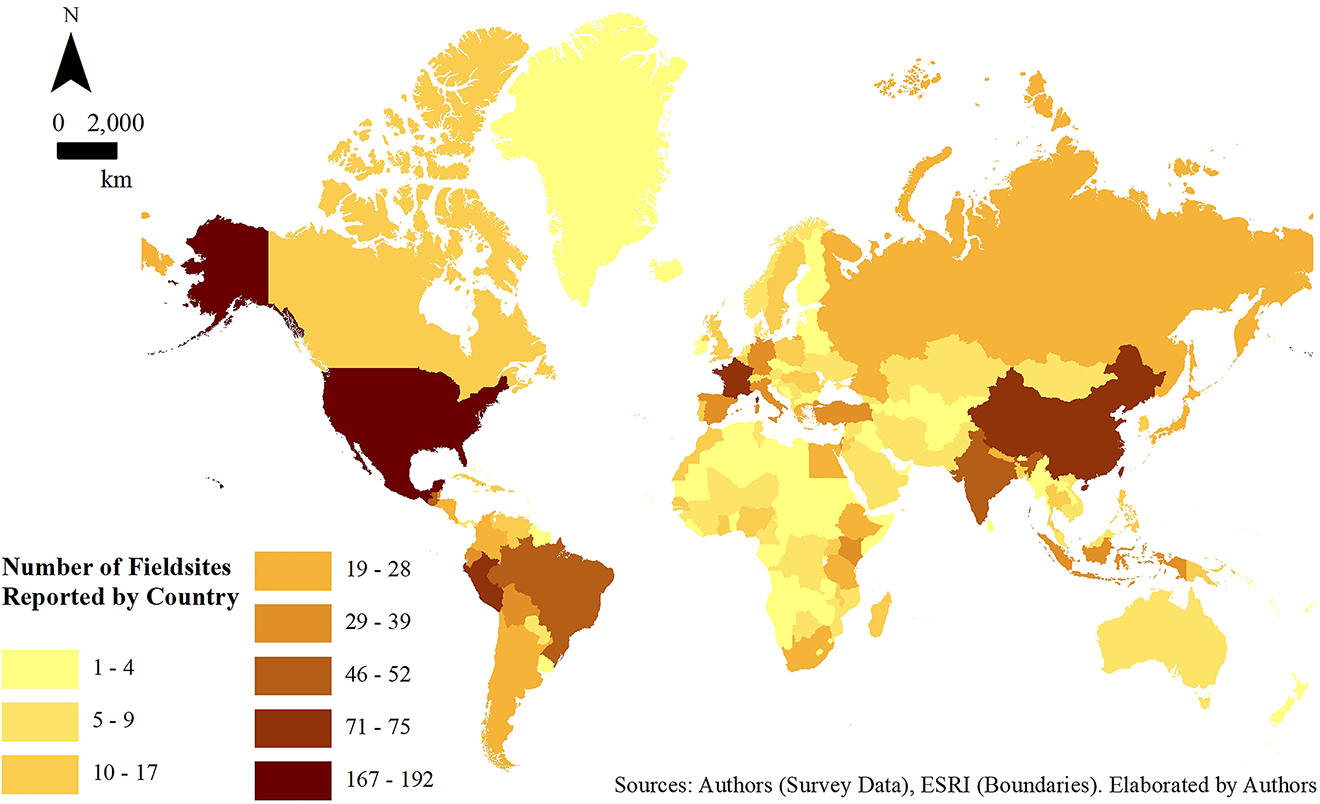

Spatially, our analysis encompasses insights from over 180 different countries and territories where our respondents were active. Fifty one among those locations had at least 10 fieldsites reported equaling 1,740 fieldsites, approx. 80% of all reported in our survey (Figure 1). While the traditional division between anthropologists researching the cultures of colonized people and sociologists working in Western societies holds, it is less clear than one could expect (Figure 2). Still, anthropologists have a greater presence in Africa, the Middle East, Asia (especially South-East), and South America comparing to sociologists who tend to engage in fieldwork in North and Central America, Europe (especially Western), and Asia.

Number of fieldsites reported by country.

Comparison of fieldsites distribution between anthropologists and sociologists.

2.2 Instrument

The questionnaire consisted of 22 closed-ended, open-ended, and Liker-type questions. The respondents indicated geographic and linguistic characteristics of their fieldsites, as well as if they had “another person to translate/interpret” for them. At this point, we need to highlight that in our previous study that served as a pilot for this survey, we asked if our participants have ever used a translator/interpreter in their field research. Some of our respondents marked “no” and then listed other people who de facto acted as one. Assuming that our respondents might have chosen this answer as they thought we asked for a qualified professional, in the current survey, we opted for a more generic formulation of the question, hence we simply asked if they have used “another person to translate/interpret” for them.

This procedure allowed us to describe our sample in terms of languages encountered, but also map the regional differences in collaboration with translators. Next, we inquired about motives for their collaboration with translator(s) or lack thereof, following up with a question on how they managed in environments where a language(s) other than English was present. We also inquired regarding translators’ professional profile, role, language pairs, and fieldsite settings, as well as any problematic situations, and scholars’ satisfaction with their collaboration. Further, we elicited respondents’ level of agreement with statements related to the methodological and ethical issues surrounding the knowledge of vernacular, use of English in the field site, and the influence of translators on the research process. Additionally, we asked our participants to list all languages they interacted with during their field research,[4] and to assess their fluency level based on a simplified version of an Interagency Language Roundtable (ILR) scale (Interagency Language Roundtable n.d.)[5] measuring language ability from 0 (No Proficiency) to 5 (Functionally Native Professional Proficiency). We then asked our respondents for any additional comments and solicited their demographic and professional profiles.

2.3 Analysis

We descriptively analyzed the 913 responses, including the geographies of language and translation in field research, researchers’ linguistic competence, history of collaboration with a translator and their profiles, perspective on the importance of vernacular’s knowledge, as well as perspectives on the admissibility of translators. To provide further insight into the context and motives behind researchers’ decisions we triangulated descriptive analysis with a thematic qualitative analysis of the open-ended prompts to 1) elaborate on decisions to involve (or not) an interpreter meaningfully answered by 869 respondents, 2) provide additional comments on the process meaningfully answered by 406 participants. Therein, data was first coded and then synthesized into major themes related to the decision on a collaboration with translators or lack thereof emerging across the responses. We provided illustrative excerpts from the answers accompanied with a basic profile of the participant, in the following format: gender – race/ethnicity – discipline – years of experience – rank – fieldsite locations.

3 Results

3.1 Touting the proficiency, but lacking competence in vernacular

The advantage of language proficiency, as a medium to understand “local” knowledges was brought to attention by several contemporary sociologists (Birbili 2000; Bradby 2002; Scheyvens and Storey 2014; Temple 1997; Useem 2019 [1963]), and over 95% of our respondents supported this notion in the survey. Moreover, an overall agreement that researchers who work in a non-English environment should know the vernacular language was also high among our respondents at 81.9%. However, the self-assessment of proficiency in fieldwork languages provided by the same scholars stands in a startling contrast to their statements on the language mastery. In only 24% of the fieldwork, researchers’ proficiency was at full professional, native or bilingual levels, and in almost 60% of the cases, our respondents interacted with languages in which their proficiency was at or below limited working level (Table 3). Does it mean that in contemporary fieldwork researchers fail to put their own methodological stance into practice?

Proficiency in fieldwork languages other than English by level and discipline.

| Discipline | Anthropology | Sociology | Other | No answer | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No proficiency | % | 24.2 | 28.3 | 24.1 | 36.5 | 25.4 |

| Elementary proficiency | % | 16.1 | 15.0 | 16.7 | 7.9 | 15.7 |

| Limited working proficiency | % | 16.2 | 14.8 | 11.5 | 22.2 | 15.7 |

| Professional working proficiency | % | 20.4 | 15.0 | 24.1 | 7.9 | 19.2 |

| Full professional proficiency | % | 13.8 | 11.2 | 10.9 | 9.5 | 12.9 |

| Native or bilingual proficiency | % | 9.3 | 15.7 | 12.6 | 15.9 | 11.1 |

| Total | % | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

Not necessarily, as almost 75% of the researchers speak at least one fieldwork language other than English at a professional working, full professional, or native or bilingual level. Still, although our respondents reported interactions with over 400 languages, one should notice that they frequently deal with postcolonial linguistic legacies and those are also languages in which they present highest proficiency (Table 4), interestingly, matching the enrollment in the fifteen most taught languages in the US higher education institutions (see Looney and Lusin 2019). Our thematic analysis indicates that lack of proficiency is frequently related to the dynamics of contemporary fieldwork. We turn to this issue in the next sections. However, other common explanations for lack of linguistic preparation include personal and societal traits such as a lack of interest in foreign language learning, a lack of time, and the global popularity of English. Language instruction funding and access issues were also raised by our respondents, and parallels the general trends in foreign language learning in the US:

It takes a long time and total immersion to learn a local language properly--training programs and funding should reflect this! Ease of social media access probably interferes if it encourages grad students to keep one foot back in their home social network and linguistic world. (Male – White – Anthropology – 27 – Full Professor -Indonesia)

Proficiency in the most encountered (over 1%) fieldwork languages.

| No proficiency | Elementary | Limited working | Professional working | Full professional | Native or bilingual | No. of interactions | % of all interactions | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spanish | 4.0% | 10.2% | 13.4% | 24.3% | 26.6% | 21.6% | 403 | 19.5% |

| French | 4.5% | 9.6% | 22.6% | 33.9% | 16.4% | 13.0% | 177 | 8.6% |

| Arabic | 29.4% | 22.1% | 23.5% | 11.8% | 10.3% | 2.9% | 68 | 3.3% |

| Chinese | 31.1% | 8.2% | 11.5% | 13.1% | 18.0% | 18.0% | 61 | 3.0% |

| Portuguese | 6.9% | 1.7% | 22.4% | 24.1% | 31.0% | 13.8% | 58 | 2.8% |

| German | 11.5% | 9.6% | 17.3% | 19.2% | 21.2% | 21.2% | 52 | 2.5% |

| Swahili | 18.6% | 23.3% | 32.6% | 18.6% | 2.3% | 4.7% | 43 | 2.1% |

| Russian | 26.3% | 18.4% | 13.2% | 10.5% | 18.4% | 13.2% | 38 | 1.8% |

| Italian | 8.3% | 8.3% | 16.7% | 30.6% | 25.0% | 11.1% | 36 | 1.7% |

| Indonesian | 16.7% | 3.3% | 10.0% | 43.3% | 26.7% | 0.0% | 30 | 1.5% |

| Quechua | 43.3% | 30.0% | 16.7% | 6.7% | 3.3% | 0.0% | 30 | 1.5% |

| Hebrew | 32.1% | 17.9% | 3.6% | 25.0% | 0.0% | 21.4% | 28 | 1.4% |

| Hindi | 7.4% | 14.8% | 14.8% | 14.8% | 11.1% | 37.0% | 27 | 1.3% |

| Greek | 26.1% | 21.7% | 21.7% | 17.4% | 4.3% | 8.7% | 23 | 1.1% |

| Japanese | 22.7% | 0.0% | 13.6% | 22.7% | 27.3% | 13.6% | 22 | 1.1% |

| Turkish | 22.7% | 13.6% | 27.3% | 18.2% | 9.1% | 9.1% | 22 | 1.1% |

3.2 The commonness of translation services in field research

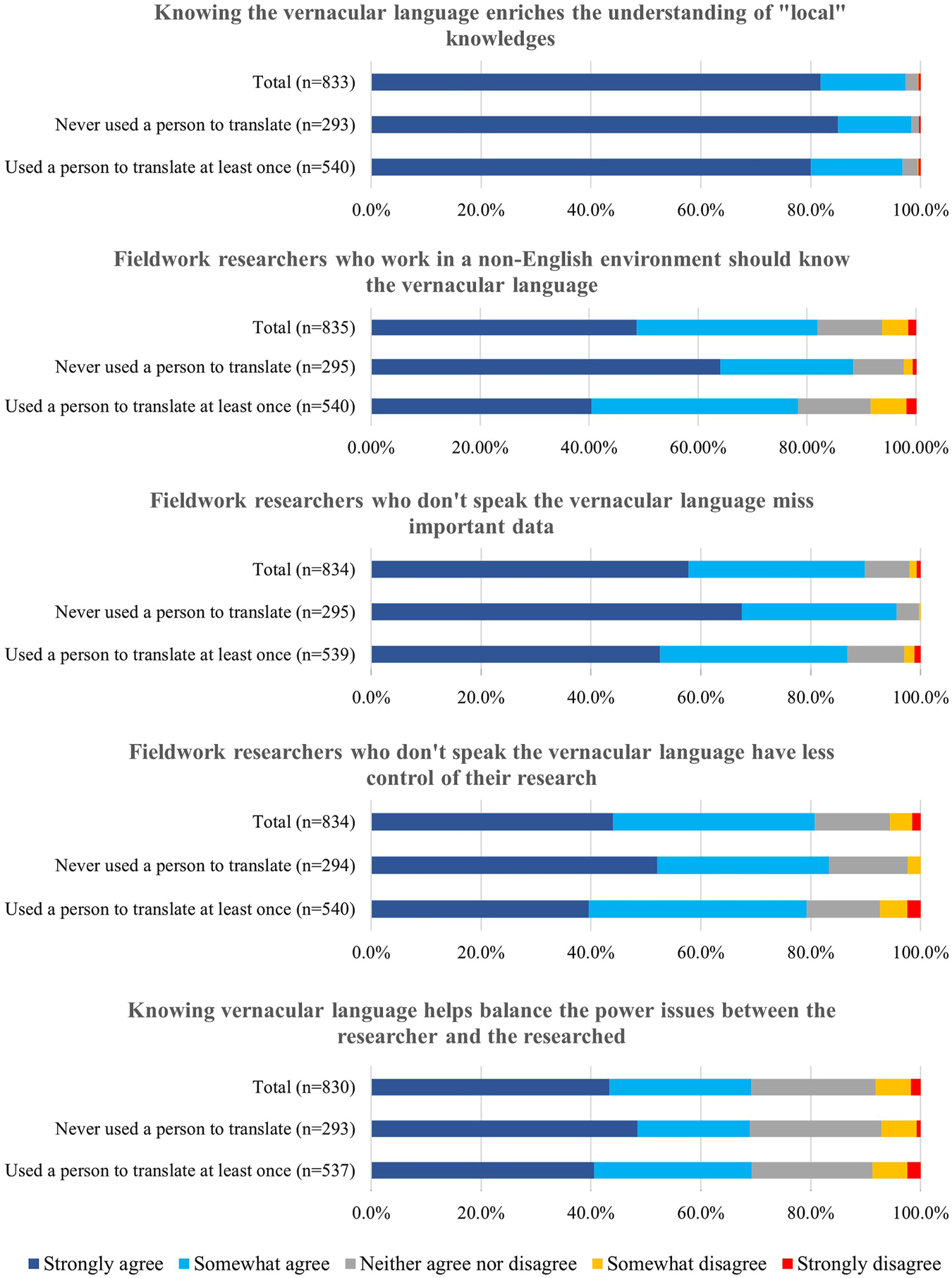

Following the above discussed trends in language proficiency, it is not surprising—but still quite fascinating to note—that over 65.3% of our respondents, and especially 68.9% of anthropologists, representatives of a discipline that promoted the idea of mastering the vernacular and dispensing of interpreters (see Beattie 1964; Evans-Pritchard 1951; Fortes 1945; Malinowski 1984 [1922]; Mead 1939), used a translator at least in one of their fieldsites. This is by no means a critique of contemporary anthropologists, but rather an indication that the “textbook” knowledge and still existing ethos of field research do not necessarily fit the fieldwork reality. A widespread inclusion of methodological guidelines on collaboration with translators could help diminish biases in perception and application of vernacular’s proficiency. For example, our current results indicate a relationship between an agreement that researchers who work in a non-English environment should know the vernacular language and respondent’s history of collaboration with a translator (78.4% overall and 40% strong agreement) or lack thereof (88.5% overall and 64% strong agreement). The opinions on the relationship between not knowing the vernacular and missing important data, possessing less control over the research, and balancing the power between the researched and researcher present a similar pattern (Figure 3).

Opinions on language in fieldwork by experience with translator.

Interestingly, ‘only’ 54.1% of the sociologists in our sample ever collaborated with a translator compared to over two thirds of anthropologists. It would, however, be spurious to claim that American sociologists had less need for translators due to their proficiency in languages other than English. It is rather due to the traditional research interests exposing anthropologists to an increased number of languages and geographies, as visible in the highest shares of fieldwork with translator use reported in African and Asian countries. In comparison, sociologists frequently work in the US and regions like Western Europe where one could claim to “get by” with English (compare Figures 2 and 4). This aligns with the results of our thematic analysis which indicates the global popularity of English as one of the deterrents to mastering field languages among respondents.

Geographic distribution of translators use during the fieldwork.

3.3 Liabilities of using English

The overreliance on English is a frequent and a problematic practice in both international research and studies of domestic minorities. Our thematic analysis found detailed accounts of thirty-four respondents[6] conducting their studies using English in communities that were not primarily English speaking. Additionally, fifteen scholars explained use of their native majority languages (mostly Spanish and Russian) instead of the local language, because the researched population knew the researcher’s language well enough to communicate. Using researchers’ native language in an environment where it is relatively well known as a second or official language is a convenient option, but implications of this approach should not be ignored. The first concern is related to the issue of representation, as people may present themselves differently in different languages (Temple and Koterba 2009). On the other hand, Pavlenko (2006) highlights that in bilingual individuals, ‘the two languages may be linked to different linguistic repertoires, cultural scripts, frames of expectation, autobiographic memories, and levels of proficiency and emotionality. They may also be associated with conflicting allegiances, distinct imagined audiences, incompatible subject positions, and mutually exclusive arguments’ (p. 27). We thus deal with a political act that should be recognized as such with all ethical and methodological implications (see Clifford 1983; Spivak 1993; Temple and Koterba 2009; Venutti 1995) as presented by one of our respondents:

Some of my interviewees overtly complained about foreign researchers who did not speak their local languages at all and told me that they gave only “courtesy” answers or answers what researchers were looking for. This kind of emotion was quite intense among interviewees, especially when they were regarded as “marginalized” or “minority” people. (Female – Asian – Sociology – 15 – Associate Professor – Japan, USA, UK)

Since not all languages have equal status (Blommaert 1996), often due to the process of colonization, a direct use of privileged languages like English implies an unstable balance between two languages and two cultures (Alvarez and Vidal 1996). The dominant language is intrinsically linked to power and available exclusively for the wealthy resulting with the voices of marginalized populations lost among those privileged to the knowledge (Watson 2004). Because of that, and despite that some field researchers ‘use interpreters, not because (…) [they] like to, but because (…) [they] have no other choice’ (Lowie 1940: 89) there is a methodological need to identify situations that call for a support of an interpreter and the circumstances in which the use of vernacular by a researcher is preferred.

3.4 Necessity and admissibility of interpreters

Our respondents indicated a variety of field circumstances which generate a need for translators, many of them related to the modern dynamics of field research. The increase in short-term projects, multi-sited fieldwork, international collaborative research, and studies of communities with multiple co-existing languages are among the most frequently encountered factors in our thematic analysis, as exemplified by the following respondents:

I am fluent in most of the languages I use in the field (plus a few more). But for short-term comparative studies, it is not feasible to prepare to the point of fluency. Only in that situation do I use a translator. I consider it essential for long-term work to always work in the native language of the research site. (Male – White – Anthropology – 40 – Full Professor – Iran, Arabian Peninsula, Japan, Germany, Austria, India, Malaysia, China, Indonesia)

I conducted research in an urban context where multiple languages were present. Because I do not have a fluency in all necessary languages but wanted to interview interlocutors from a variety of language fluencies, I relied on interpreters to carry out my research. (Male – White – Anthropology – 8 – Adjunct – South Sudan)

I run multi-national projects. In Albania and Kosovo in particular we use both English and Albanian as official project languages. Day to day and while working, I can get by in Albanian. For some important conversations I use a translator, typically my wife and co-director who is a native speaker of Albanian. For […] ethnographic research, we typically used native speakers to conduct interviews or assist with the interviews. (Male – White – Anthropology – 20 – Full Professor – Greece, Albania, Kosovo, Hungary)

However, we have also identified several patterns of circumstances where a need for translator raised not due to the complexity of a field study, but rather because of low proficiency among scholars, including some languages being either – subjectively – too difficult to learn, or spoken by only few individuals and impossible to learn before fieldwork due to logistical reasons. Another glimpse at Figure 4 corroborates this problem with the geographic distribution of the use of interpreters. In fact, several respondents understood language acquisition as a methodological process that takes place during fieldwork (frequently alongside a translator). Other criticized the idea of rapid language acquisition as unrealistic:

It always amazing me when some anthropologists purport to have learned the language of their research group in less than a year, and then conducted all their research in that language. I am a true bilingual in Swedish and English, and I can say with confidence that this is not possible, or if they do, they are not picking up on the nuances of meaning on the topic(s) of their research. […] Hence, I think anthropologists working in communities who speak languages which are not the researcher’s native language, must always use local translators. (Female – White – Anthropology – 28 – Associate Professor – Kenia, Tanzania, Ethiopia)

Therefore, it is not surprising that our respondents overwhelmingly agreed that the lack of language competency during fieldwork should trigger a collaboration with translator, with the sentiment being stronger among those who had experience with translators, indicating an inverted trend comparing to the pattern seen in previously discussed opinions (compare Figures 3 and 5).

Translator’s admissibility and their impact on fieldwork by experience with translator.

3.5 Avoidance and disownment of interpreters

Still, our thematic analysis indicated that hiring an interpreter when needed is not always a possibility. For instance, twelve respondents explained that limited funding was an obstacle and even altered their research design, with the issue affecting both early-career and experienced researchers. The lack of resources is a reappearing, but not the most common reason that leads to an executive decision to avoid help from interpreters. Our analysis of the scholars who did not resort to translators’ help found that thirty-five explicitly referred to ethical and methodological issues dictated by their discipline advocating language proficiency, most frequently: the respect toward the studied community, increased accessibility, direct contact with collaborators, and establishing rapport. Those factors are in line with previous individual accounts on the process of language acquisitions (see or Watson 2004). Additionally, several respondents noted that an intermediary would have possibly jeopardized their research, as interviewees would not feel comfortable to answer sensitive questions, like in the example:

[…] the presence of a translator can be problematic, and I felt could negatively impact my ethnographic research. I am proficient in Malayalam, so decided to conduct my research, including recorded interviews, on my own, and consult with my former Malayalam teacher on sections of the interview I did not fully understand. In this case, I would indicate which sections or words of the interview I didn’t understand, and I had a native speaker transcribe those phrases or words so that I could look up the meaning in a dictionary […] (Female – White – Anthropology – 3 – Assistant Professor – India)

Interestingly, even though this participant marked “no” as an answer to the question if they have ever used another person to translate/interpret for them, their extended explanation shows the contrary. In fact, a similar pattern was found in another thirty-three respondents, stating they had not collaborated with a translator/interpreter, and at the same time describing interpreter’s tasks performed by their colleagues, research assistants, bilingual managers, or family members. This, apparently not uncommon, misperception adds to the marginalization and methodological invisibility of the translator profession (see Sepielak et al. 2019). Furthermore, the researchers that had an opportunity to collaborate with translators hold in higher regard their role in accessing data (88.5% overall agreement) compared to those that never resorted to such help (69.1% overall agreement), thus the hesitation seems to be related to the experience. Similar pattern exists in researchers’ opinions regarding translators’ negative interference in data collection (Figure 5) where some previous work with translators increases the level of disagreement with the statement (50.8% overall disagree and 14.1% overall agree) compared to lack of such collaboration (39.3% overall disagree and 34.4% overall agree). The role of previous experience in forming an opinion on the role of translators is even more emphasized here, with over a third of the respondents among those lacking any experience with translators forming negative opinions about their influence on the fieldwork. Those opinions appear prejudicial and are alarming, especially in the reality of the common collaboration with translators and interpreters found by our study.

3.6 Profile and evaluation of interpreters

A glimpse at the survey trends regarding the characteristics of those who translated/interpreted for our respondents (Table 5) provides further insight into this issue, indicating an almost complete reliance on a non-professional unpaid interpreter, with only 10% of our respondents working with a professional paid interpreter at least once.

Profile of a person who translated/interpreted.

| Anthropology | Sociology | Other | Not provided | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A paid local person who was not a professional translator/interpreter | N | 175 | 51 | 23 | 22 | 271 |

| % | 31.4 | 30.4 | 29.5 | 28.2 | 30.7 | |

| A non-paid local person who was not a professional translator/interpreter | N | 121 | 29 | 17 | 16 | 183 |

| % | 21.7 | 17.3 | 21.8 | 20.5 | 20.7 | |

| A paid local professional translator/interpreter | N | 39 | 19 | 7 | 4 | 69 |

| % | 7.0 | 11.3 | 9.0 | 5.1 | 7.8 | |

| A paid professional translator/interpreter who arrived with the research team | N | 10 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 16 |

| % | 1.8 | 1.8 | 3.8 | 0 | 1.8 | |

| A research team member who knew the language, but was not a professional translator/interpreter | N | 200 | 59 | 25 | 30 | 314 |

| % | 35.8 | 35.1 | 32.1 | 38.5 | 35.6 | |

| Other | N | 13 | 7 | 3 | 6 | 29 |

| % | 2.3 | 4.2 | 3.8 | 7.7 | 3.3 | |

| Total | N | 558 | 168 | 78 | 78 | 882 |

Besides the funding challenges, our thematic analysis indicated several trends behind relying on non-professional or unpaid interpreters. Most frequently those were presented as pertaining to the relationships with or within the researched communities and described as innate features of the field research. Frequently, an extensive international fieldwork prompted local friendships, that were later conveniently invited to participate in the research process as translators (sometimes while researchers were in the language learning process themselves). In several cases, those informal reciprocity arrangements were given preferences to professional translators, as the latter would be drawn disproportionately from the more affluent or culturally different sectors of society, as in the example:

In Yemen the class background of the translator interfered with her neutrality – she was of a higher class than most of the women I was interviewing, and it was apparent from her behavior that she was disrespecting them. (Female–White–Anthropology–35–Professor–Peru_Kyrgyzstan_Kazakhstan_Belize_India_Yemen_Burkina_Faso_Ghana_Mexico)

A persistent pattern indicated that arrangements with informal interpreters would sometimes convert or begin as a part of a patron-client relationship with an unbalanced power difference between the researcher and the translator or the community. Other times, the respondents explained that the arrangements were parts of negotiations of power withing a wider local informal politics setting:

In Ethiopia and Kenya, we also hired local people who knew a bit of English, in part, as a goodwill gesture to tribal leaders. Security situation was such that they were going to send a few warriors out to keep an eye on us anyway, so we figured hiring them and paying them to help out on the excavation was just a good way to keep them out of trouble. (Female–White–Anthropology–45+–Retired–Kenia_Ethiopia_Netherlands_Indonesia)

Our thematic analysis found contrasting evaluations of ethical and methodological premises behind these practices, with some of the respondents finding the habitual interpreters’ profiles deeply concerning:

The worse in my opinion is the white male researcher who does not know the local language, but has married a woman who is a native of the country (but not the region) and uses her as his translator, project manager, etc. It’s very common in some subfields, and it establishes a race/gender/nationality hierarchy that reinforces local power dynamics and guarantees that the researcher is only going to hear hegemonic points of view (i.e., older males in the community probably approve, young women are only going to say and do what they think powerful men want to hear). (Female–White–Anthropology–30+–Full_Professor–Ecuador_Peru)

I make it a point to only bring on team members who are able to communicate with the local members of the project. While I do this to improve the quality of research and facilitate the research process, I primarily do this to de-colonialize the research process, i.e. mitigate the fact that I am an American researcher working in a country with a long history of imperialist relations, beyond and including archaeology (Latin America). (Female–White–Anthropology–4–Full_time_Teaching_Appointment–Peru)

Ethical issues appear as paramount here with the controversial and under-researched problem of the informal economy in translation with Motsie (2010) suggesting that a market may exist for informal interpreters with haphazard linguistic skills due to the target groups linguistic skills, and Marais (2014: 187) indicating that “the focus [within translation studies] on high culture is not wrong but limited’ calling on scholars to ‘study the informal economy in order to better understand the role of (informal and nonprofessional) translation in the emergence of society and how translation could be developed (if necessary) in the informal economy.” Interestingly, in line with the calls for better understanding of informal translation, over 95% of our respondents were satisfied with the persons who translated for them (Figure 6). Without doubt, researchers’ satisfaction with non-professional or/and non-paid interpreters does not erase issues related to power dynamics, data quality or translators’ marginalization, but it constitutes another relevant indicator of their perspective on the involvement of an interpreter.

Satisfaction with translator by discipline.

4 Discussion and conclusions

In this study, we went beyond the anecdotal evidence and documented that widespread fieldwork language fluency does not exist in American anthropology and sociology. To the contrary, our data implies that only a quarter of encounters with languages other than English met researchers’ full professional, bilingual, or native proficiency. While three-quarters of respondents still reported a minimum of a working proficiency in at least one of their fieldsite languages, a vast number constitute linguistic legacies bequeathed by imperialism and colonialism, often considered as political tools of oppression or social stratification. The practices of multi-sited fieldwork, rapid field assessments, international collaborative research, and linguistically diverse communities were most frequently mentioned as mitigating development of fluency in additional languages. The subjective difficulty of a language, access to a rare language, over-reliance on English, lack of time, interest, funding, or opportunities were also commonly listed by respondents as obstacles in language acquisition. In the end, field researchers did not dispense with interpreters, as Evans-Pritchard (1951) would have wished, but rather with the myth, or sleight of hand, of linguistic fluency.

At the same time, the researcher’s lack of linguistic proficiency does not equate to the lack of interactions with languages other than English. Our data showed this very clearly, with over a half of sociologists and two-thirds of anthropologists who interacted with languages other than English during fieldwork collaborating with translators at least once during their field studies. Once again, we highlight these figures not to excoriate the field researchers, but rather to point out differences between the contemporary fieldwork practice, the methodological ethos pervasive in classical literature, and the lack of fundamental preparation for researchers with methods textbooks evading the topics of managing languages and translation in fieldwork (compare Bernard 2006; Eriksen 2015; Welsch and Vivanco 2018).

The lack of consistent methodology is mirrored on the ground, where the translation services are employed in a haphazard manner, frequently relying on non-professional interpreters, non-paid locals, but also colleagues and family frequently not even recognized in their roles. We have documented that informal reciprocity agreements, negotiations of power within informal local politics, convenience, and budgetary issues appear as decisive factors regarding the decision on who is translating in the field. In some cases, decisions not to hire a professional interpreter appear to be based on methodological premises, frequently derived from status differences between the translator and translated communities. At the same time, data indicates researchers’ high satisfaction level with those who translated for them regardless of professional status or the level of formalization of collaboration. Despite the scholars’ contentment, several troubling ethical and methodological consequences emerge from this situation, including the proliferation of marginalization and the informal economy in translation, skewed fieldsite power dynamics, data quality issues, and safety considerations among others. We recommend that all those aspects be studied in future from the perspective of languages and translation in the fieldwork, but also from the perspective of those serving either as formal or ‘invisible’ translators.

Moreover, our data showed that a history of collaboration with translators is related to the stronger positive sentiments regarding their impact on fieldwork and a more lenient outlook on researcher’s language proficiency. Conversely, self-reliance is related to a more cautious or even dismissive approach to translators and emphasis on vernacular’s importance. This, somewhat prejudicial, approach to the role of field translators adds to the shushed requirement for any training and heightens marginalization and invisibility of the profession, sometimes – graciously – folded under an umbrella of a “research assistant”. No doubt, a consistent inclusion of guidelines in methodological papers and textbooks is needed and we hope that this study will facilitate this advancement.

-

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

-

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

Alvarez, Roman M. & Carmen Africa Vidal. 1996. Translation, power, subversion. Philadelphia: Multilingual Matters Ltd.Search in Google Scholar

American Anthropological Association. 2020. 2019 department survey, faculty profile module. https://secure.americananthro.org/eWeb/DynamicPage.aspx?Site=AAAWeb&WebKey=033b4db0-7a98-48d9-a183-cf506a381ff3 (accessed 10 November 2021).Search in Google Scholar

American Community Survey. 2019. ACS 5-year estimates: Limited English-speaking households (S1602). https://data.census.gov (accessed 10 April 2019).Search in Google Scholar

American Sociological Association. 2021a. ASA regular members by gender and race/ethnicity. https://www.asanet.org/academic-professional-resources/data-about-discipline/asa-membership/asa-regular-members-gender-and-raceethnicity (accessed 24 October 2021).Search in Google Scholar

American Sociological Association. 2021b. Guide to graduate departments of sociology. Washington: ASA.Search in Google Scholar

Angelelli, Claudia V. 2004. Medical interpreting and cross-cultural communication. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511486616Search in Google Scholar

Bajčić, Martina & Katja Dobrić Basaneže. 2016. Towards the professionalization of legal translators and court interpreters in the EU. Cambridge, New York: Cambridge University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Baker, Nicholas. 1981. Social work through an interpreter. Social Work 26. 391–397.Search in Google Scholar

Baker, Phill, Zahida Hussain & Jane Saunders. 1991. Interpreters in public services: Policy and training. London: Venture Press.Search in Google Scholar

Barth, Fredrik. 1959. Political leadership among Swat Pathans. Monographs in social anthropology. London: London School of Economics.Search in Google Scholar

Beattie, John. 1964. Other cultures. Aims, method, and achievements in social anthropology. New York: The Free Press.Search in Google Scholar

Berk-Seligson, Susan. 2000. Interpreting for the police: Issues in pre-trial phases of the judicial process. International Journal of Speech Language and the Law 7(2). 212–237. https://doi.org/10.1558/sll.2000.7.2.212.Search in Google Scholar

Bernard, Russell. 2006. Research methods in anthropology: Qualitative and quantitative approaches, 4th edn. Lanham, MD: AltaMira Press.Search in Google Scholar

Birbili, Maria. 2000. Translating from one language to another. Social Research Update 31. 1–7.Search in Google Scholar

Blommaert, Jan. 1996. Language and nationalism: Comparing Flanders and Tanzania. Nations and Nationalism 2(2). 235–256. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1354-5078.1996.00235.x.Search in Google Scholar

Borchgrevink, Axel. 2003. Silencing language: Of anthropologists and interpreters. Ethnography 4(1). 95–121. https://doi.org/10.1177/1466138103004001005.Search in Google Scholar

Bradby, Hannah. 2002. Translating culture and language: A research note on multilingual settings. Sociology of Health and Illness 24(6). 845–855. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.00321.Search in Google Scholar

Brecht, Richard D. 2015. America’s languages: Challenges and promise. American councils for international education. https://www.amacad.org/sites/default/files/academy/multimedia/pdfs/AmericasLanguagesChallengesandPromise.pdf (accessed 1 February 2020).Search in Google Scholar

Bryman, Alan. 2016. Social research methods, 5th edn. Oxford: Oxford University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Bulmer, Martin. 1984. The Chicago school of sociology. Institutionalization, diversity, and the rise of sociological research. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.Search in Google Scholar

Chagnon, Napoleon. 1992. Yanomamo: The last days of Eden. New York: Harvest Books.Search in Google Scholar

Chalasinski, Józef. 1963. Florian Znaniecki – socjolog polski i amerykański. Przegląd Socjologiczny/Sociological Review 17(1). 7–18.Search in Google Scholar

Clifford, James. 1983. On ethnographic authority. Representations 2. 118–146. https://doi.org/10.2307/2928386.Search in Google Scholar

Deane, Kevin & Sara Stevano. 2016. Towards a political economy of the use of research assistants: Reflections from fieldwork in Tanzania and Mozambique. Qualitative Research 16(2). 213–228. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794115578776.Search in Google Scholar

Devlin, Kat. 2016. Most European students are learning a foreign language in school while Americans lag. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/08/06/most-european-students-are-learning-a-foreign-language-in-school-while-americans-lag/#:∼:text=In%20a%202016%20Pew%20Research,eight%20skills%20for%20workers’%20success (accessed 1 February 2020).Search in Google Scholar

Eriksen, Thomas Hylland. 2015. Small places, large issues: An introduction to social and cultural anthropology, 4th edn. London: Pluto Press.10.2307/j.ctt183p184Search in Google Scholar

Evans-Pritchard, Edward E. 1951. Social anthropology. London: Cohen and West.Search in Google Scholar

Fortes, Meyer. 1945. The dynamics of clanship among the Tallensi. London: Oxford University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Freed, Anne O. 1988. Interviewing through an interpreter. Social Work 33. 315–319.Search in Google Scholar

Freeman, Derek. 1983. Margaret Mead: The making and unmaking of an anthropological myth. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Gaillard, JC & Lori Peek. 2019. Disaster-zone research needs a code of conduct. Nature 575. 440–442. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-019-03534-z.Search in Google Scholar

Gibb, Robert & Julien Iglesias. 2016. Breaking the silence (again): On language learning and levels of fluency in ethnographic research. The Sociological Review 65(1). 134–149. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-954x.12389.Search in Google Scholar

Interagency Language Roundtable. n.d. Interagency language roundtable. Interagency Language Roundtable. https://www.govtilr.org/index.htm.Search in Google Scholar

Lai, Miranda & Sedat Mulayim. 2010. Training refugees to become interpreters for refugees. Translation and Interpreting 2(1). 48–60.Search in Google Scholar

Looney, Dennis & Natalia Lusin. 2019. Enrollments in languages other than English in United States institutions of higher education, Summer 2016 and Fall 2016: Final Report. Modern Language Association. https://www.mla.org/content/download/110154/2406932/2016-Enrollments-Final-Report.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

Lowie, Robert H. 1940. Native languages as ethnographic tools. American Anthropologist 42(1). 81–89. https://doi.org/10.1525/aa.1940.42.1.02a00050.Search in Google Scholar

Malinowski, Bronislaw. 1984 [1922]. Argonauts of the Western Pacific. Prospect Heights: Waveland.Search in Google Scholar

Malinowski, Bronislaw. 1989. A diary in the strict sense of the term. Stanford: Stanford University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Marais, Kobus. 2014. Translation theory and development studies: A complexity theory approach. New York: Routledge.10.4324/9780203768280Search in Google Scholar

Mead, Margaret. 1939. Native languages as fieldwork tools. American Anthropologist 41(2). 189–205. https://doi.org/10.1525/aa.1939.41.2.02a00010.Search in Google Scholar

Mendoza, Cristobal & Ricard Moren-Alegret. 2013. Exploring methods and techniques for the analysis of senses of place and migration. Progress in Human Geography 37(6). 762–785. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132512473867.Search in Google Scholar

Molony, Thomas & Daniel Hammett. 2007. The friendly financier: Talking money with the silenced assistant. Human Organization 66(3). 292–300. https://doi.org/10.17730/humo.66.3.74n7x53x7r40332h.Search in Google Scholar

Motsie, Kefuwe. 2010. Multicultural communication and translation in integrated marketing communication: Informal advertisements. Bloemfontein, South Africa: University of the Free State Unpublished MA mini-dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

Murray, Craig D. & Joanne Wynne. 2001. Researching community, work and family with an interpreter. Community, Work and Family 4(2). 151–171. https://doi.org/10.1080/713658930.Search in Google Scholar

Newmark, Peter. 1988. A textbook of translation. Hempstead: Prentice Hall.Search in Google Scholar

Palmary, Ingrid. 2011. ‘In your experience’: Research as gendered cultural translation. Gender, Place and Culture 18(1). 99–113. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369x.2011.535300.Search in Google Scholar

Pavlenko, Aneta. 2006. Bilingual minds: Emotional experience, expression and representation. Clevedon: Multi Lingual Matters Ltd.10.21832/9781853598746Search in Google Scholar

Pym, Anthony. 1999. Nicole slapped Michelle. The Translator 5(2). 265–283. https://doi.org/10.1080/13556509.1999.10799044.Search in Google Scholar

QS. 2018. The QS world university rankings. https://www.topuniversities.com/university-rankings/world-university-rankings/2018 (accessed 29 August 2018).Search in Google Scholar

Rabinow, Paul. 1977. Reflections on fieldwork in Morocco. Berkeley: University of California Press.Search in Google Scholar

Rumbaut, Rubén. 2009. A language graveyard? The evolution of language competencies, preferences and use among young adult children of immigrants. In Terrence, G. Sook Lee & Russell Rumberger (eds.), The education of language minority immigrants in the United States, 35–70. Bristol: Multilingual Matters. Available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1883184.10.21832/9781847692122-004Search in Google Scholar

Scheyvens, Regina & Donavan Storey. 2014. Development fieldwork: A practical guide, 2nd edn. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.Search in Google Scholar

Sepielak, Katarzyna, Daiwd Wladyka & William Yaworsky. 2019. Unsung interpreters: The jumbled practice of language translation in contemporary field research. A study of anthropological field sites in the Arab League Countries. Language and Intercultural Communication 19(5). 421–436.10.1080/14708477.2019.1585443Search in Google Scholar

Sinatti, Giulia. 2008. The Polish peasant revisited. Thomas and Znaniecki’s classic in the light of contemporary transnational migration theory. Sociologica, Italian Journal of Sociology Online 2(2). 1–22.Search in Google Scholar

Spivak, Gayatri C. 1993. The politics of translation. In Gayatri C. Spivak (ed.), Outside in the teaching machine, 179–200. New York: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Stein-Smith, Kathleen. 2016. The U.S. foreign language deficit strategies for maintaining a competitive edge in a globalized world. Teaneck, NJ: Palgrave McMillan.Search in Google Scholar

Sukarieh, Mayssoun & Stuart Tannock. 2019. Subcontracting academia: Alienation, exploitation and disillusionment in the UK overseas Syrian refugee research industry. Antipode 51(2). 664–680. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12502.Search in Google Scholar

Temple, Bogusia. 1997. Watch your tongue: Issues in translation and cross-cultural research. Sociology 31(3). 607–618. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038597031003016.Search in Google Scholar

Temple, Bogusia & Katarzyna Koterba. 2009. The same but different—researching language and culture in the lives of Polish people in England. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum: Qualitative Social Research 810(1). 31.Search in Google Scholar

Turner, Sarah. 2010. Research note: The silenced assistant. Reflections of invisible interpreters and research assistants. Asia Pacific Viewpoint 51(2). 206–219. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8373.2010.01425.x.Search in Google Scholar

Useem, John. 2019 [1963]. Notes on the sociological study of language. Items 17(3). 19–24.10.1515/ijsl-2020-2077Search in Google Scholar

Venutti, Lawrence. 1995. The Translator’s Invisibility. A History of Translation. Abingdon: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Watson, Elizabeth E. 2004. ‘What a dolt one is’: Language learning and fieldwork in geography. Area 36(1). 59–68. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0004-0894.2004.00324.x.Search in Google Scholar

Welsch, Robert & Luis Vivanco. 2018. Cultural anthropology: Asking questions about humanity. New York: Oxford University Press.Search in Google Scholar

© 2022 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Articles

- Language choice in churches in indigenous Gã towns: a multilingual balancing act

- Seeking understanding: categories of linguistic (non)belonging in interviews

- Language proficiency and use of interpreters/translators in fieldwork: a survey of US-based anthropologists and sociologists

- Children’s use of English as lingua franca in Swedish preschools

- Translation for language revitalisation: efforts and challenges in documenting botanical knowledge of Thailand’s Northern Khmer speakers

- Hesitant versus confident family language policy: a case of two single-parent families in Finland

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Articles

- Language choice in churches in indigenous Gã towns: a multilingual balancing act

- Seeking understanding: categories of linguistic (non)belonging in interviews

- Language proficiency and use of interpreters/translators in fieldwork: a survey of US-based anthropologists and sociologists

- Children’s use of English as lingua franca in Swedish preschools

- Translation for language revitalisation: efforts and challenges in documenting botanical knowledge of Thailand’s Northern Khmer speakers

- Hesitant versus confident family language policy: a case of two single-parent families in Finland