Abstract

The reaction of bis(cyclohexylammonium) 4-nitrophenylphosphate with Me3 SnCl (1:2) under reflux in ethanol yielded the title compound 4-NO2 C6 H4 PO4(SnMe3)2·H2 O (1). The X-ray crystallographic analysis achieved on single crystals obtained by slow evaporation at room temperature revealed the formation of an unexpected supramolecular coordination network. The elementary building block can be viewed as two Me3 Sn moieties linked by a bridging 4-nitrophenylphosphate ligand. The two tin atoms are five-coordinated and describe a trans-Me3 SnO2 geometry in a trigonal bipyramidal arrangement. However, the Sn atoms are distinct, exhibiting two different environments. Thus, one is linked to two axial oxygen atoms from two distinct phosphato groups, whereas the other is bound to one phosphato oxygen atom and to a water molecule. From a supramolecular point of view, the combination of the tridentate binding mode of 4-NO2 C6 H4 PO4 and the additional formation of intermolecular hydrogen bonding interactions between NO2/H2 O and PO4/H2 O groups gives rise to a three-dimensional lattice network.

Introduction

As some organotin(IV) compounds have been found to be the subject of potential applications – medicine, agriculture, industry – many research groups around the world are still involved in the quest for new organotin compounds (Evans and Karpel, 1985; Yin and Wang, 2004; Zhang et al., 2006; Hanif et al., 2007). Our group is also strongly involved in this field, focusing in particular on the reactivity of organotin(IV) precursors with oxyanions in order to structurally characterize new derivatives and unexpected molecular architectures (Diallo et al., 2007, 2009; Gueye et al., 2011).

4-Nitrophenylphosphoric acid is a colorless, endogenous or exogenous pigment precursor that may be transformed by biological mechanisms into colored compounds used in many fields of application. In enzymology, it is particularly employed as a substrate for the phosphatase assay, acting as a phosphoryl donor for several phosphotransferases (Yamazaki et al., 1994; Hengge et al., 1996). Its dianion is notably traded in the form of its bis(cyclohexylammonium) salt. From a crystallographic point of view, the dihydrate form, 2[C6 H11 NH3]+[4-O2-NC6 H4 OP(O)O2]2-·2H2 O, was structurally characterized for the first time in the 80s by Jones and coworkers (Jones et al., 1984). Since then, several transition metal coordination complexes based on the use of 4-nitrophenylphosphate as ligand have been structurally isolated (Rawji et al., 2000; Gajda et al., 2001; Hassana et al., 2012). However, and surprisingly, to the best of our knowledge, only two crystallographic reports showing the coordination of bis(4-nitrophenyl)phosphate ligand to a p-block metal atom (Pb) have been deposited to date in the Cambridge Chemical Data Centre (Yamami et al., 1998a,b). In this context, it seemed worthwhile and challenging to undertake a study of the reactivity of bis(cyclohexylammonium) 4-nitrophenylphosphate toward organotin compounds. In this paper, we report the results gained from the use of Me3 SnCl as tin precursor.

Results and discussion

When bis(cyclohexylammonium) 4-nitrophenylphosphate reacts with SnMe3 Cl in EtOH, in 1:2 molar ratio under reflux, the green crystals characterized were obtained by slow solvent evaporation at room temperature (yield, 27%). The crystals are air-stable and poorly soluble in common organic solvents. The infrared (IR) spectrum exhibits characteristic absorption bands, which can be assigned to OH (3514 cm-1), PO4 (1259 and 1109 cm-1) and NO2 (1340 and 1172 cm-1) functions. In comparison to the IR fingerprint of the bis(cyclohexylammonium) 4-nitrophenylphosphate itself, some modifications affecting the PO4 and NO2 absorption bands were observed, suggesting the interaction between the tin(IV) complex and the organic ligand.

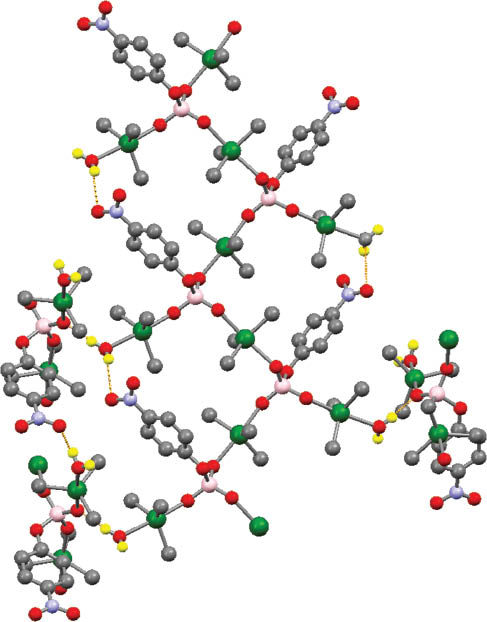

The X-ray crystallographic analysis revealed a three-dimensional (3-D) supramolecular coordination network built on the self-assembly of elementary building blocks, which can be defined as 4-NO2 C6 H4 PO4(SnMe3)2·H2 O (1). An ORTEP diagram showing the crystal structure of 1, together with selected bond lengths and angles, is given in Figure 1. The asymmetric unit consists of two independent molecules of similar metrical data (see figure caption), and the following discussion is given for the molecule based on Sn(1,2) only for brevity. 1 can be viewed as two Me3 Sn moieties connected by a bridging 4-nitrophenylphosphate ligand (L) via two P-O-Sn linkages. The two tin atoms are five-coordinated and describe a trans-Me3 SnO2 geometry in a trigonal bipyramidal (TBP) arrangement. The equatorial plane of each Sn atom contains the carbon atoms of the three methyl groups [C-Sn=2.110(9) Å (mean), C-Sn-C=119.6(4)° (mean)]. However, the Sn atoms are distinct, exhibiting two different environments with regard to the ligands in axial positions. Thus, one (Sn2) is linked to two axial oxygen atoms from two distinct phosphato groups [Sn2-O4=2.239(5) and Sn2-O5i=2.231(4) Å], whereas the other (Sn1) is bound to one phosphato oxygen atom [Sn1-O2=2.174(4)] and to a coordinated water molecule [Sn1-O1=2.391(5)], thus corroborating the presence of broad absorption band observed at 3514 cm-1 in the IR spectrum. Both TBP environments are slightly distorted [O1-Sn1-O2=177.5(2)°, O4-Sn2-O5=174.2(2)o]. The Sn-O bond to the coordinated water is the longest of this type in the molecule [Sn(1)-O(1) 2.391(5) Å], whereas the Sn-O bond trans to this one is the shortest [Sn(1)-O(2) 2.174(4) Å]; the two Sn(2)-O bonds lie between these two values and are equal within experimental error.

![Figure 1 The asymmetric unit of 1 showing the labeling scheme (ortep view).Displacement ellipsoids are drawn at 50% probability level [H atoms non-implicating in hydrogen bonding were omitted for clarity. Color code: Sn, yellow; C, violet; O, green; P, pink; N, light blue]. Selected bond lengths and angles (Å, °): Sn1-C2 2.092(9), Sn1-C1 2.097(7), Sn1-C3 2.110(7), Sn1-O2 2.174(4), Sn1-O1 2.391(5), Sn2-C11 2.120(7), Sn2-C10 2.121(7), Sn2-C12 2.129(7), Sn2-O5 2.231(4), Sn2-O4 2.239(4), Sn3-C14 2.119(8), Sn3-C15 2.119(8), Sn3-C13 2.134(8), Sn3-O9 2.136(5), Sn3-O8 2.401(6), Sn4-C23 2.105(8), Sn4-C24 2.109(8), Sn4-C22 2.113(8), Sn4-O12ii 3 2.214(5), Sn4-O11 2.306(4); C2-Sn1-C1 120.6(4), C2-Sn1-C3 121.1(4), C1-Sn1-C3 117.2(3), C2-Sn1O2 91.2(3), C1-Sn1-O2 97.3(3), C3-Sn1-O2 92.3(3), C2-Sn1-O1 88.3(3), C1-Sn1-O1 85.0(3), C3-Sn1-O1 85.9(3), O2-Sn1-O1 177.5(2), P1-O2-Sn1 130.5(3), P1-O4-Sn2 147.6(3), P1-O5-Sn2ii 139.8(3), C10-Sn2-C11 122.6(3), C10-Sn2-C12 117.6(3), C11-Sn2-C12 119.8(3). Symmetry transformations used to generate equivalent atoms (i): -x+2, y-1/2, -z; (ii): -x+2, y+1/2, -z; (iii): -x+3, y+1/2, -z+1; (iv): -x+3, y-1/2, -z+1.](/document/doi/10.1515/mgmc-2013-0058/asset/graphic/mgmc-2013-0058_fig1.jpg)

The asymmetric unit of 1 showing the labeling scheme (ortep view).

Displacement ellipsoids are drawn at 50% probability level [H atoms non-implicating in hydrogen bonding were omitted for clarity. Color code: Sn, yellow; C, violet; O, green; P, pink; N, light blue]. Selected bond lengths and angles (Å, °): Sn1-C2 2.092(9), Sn1-C1 2.097(7), Sn1-C3 2.110(7), Sn1-O2 2.174(4), Sn1-O1 2.391(5), Sn2-C11 2.120(7), Sn2-C10 2.121(7), Sn2-C12 2.129(7), Sn2-O5 2.231(4), Sn2-O4 2.239(4), Sn3-C14 2.119(8), Sn3-C15 2.119(8), Sn3-C13 2.134(8), Sn3-O9 2.136(5), Sn3-O8 2.401(6), Sn4-C23 2.105(8), Sn4-C24 2.109(8), Sn4-C22 2.113(8), Sn4-O12ii 3 2.214(5), Sn4-O11 2.306(4); C2-Sn1-C1 120.6(4), C2-Sn1-C3 121.1(4), C1-Sn1-C3 117.2(3), C2-Sn1O2 91.2(3), C1-Sn1-O2 97.3(3), C3-Sn1-O2 92.3(3), C2-Sn1-O1 88.3(3), C1-Sn1-O1 85.0(3), C3-Sn1-O1 85.9(3), O2-Sn1-O1 177.5(2), P1-O2-Sn1 130.5(3), P1-O4-Sn2 147.6(3), P1-O5-Sn2ii 139.8(3), C10-Sn2-C11 122.6(3), C10-Sn2-C12 117.6(3), C11-Sn2-C12 119.8(3). Symmetry transformations used to generate equivalent atoms (i): -x+2, y-1/2, -z; (ii): -x+2, y+1/2, -z; (iii): -x+3, y+1/2, -z+1; (iv): -x+3, y-1/2, -z+1.

From a supramolecular point of view, the phosphato group of L exhibits a tridentate coordination mode. Thus, the phosphato oxygen atom [P=O] not implicated in bonding to tin in 1 (O5, O12) is also bonded to a tin atom of another unit, leading finally to the propagation of a polymeric architecture. In addition, the formation of intermolecular hydrogen bonding interactions between NO2/H2 O and PO4/H2 O groups gives rise to a 3-D lattice network. The geometry of hydrogen bonds is detailed in Table 1. Interestingly, the coordination-driven self-assembly leads to the creation of 19-membered (3Sn, 3P, 8O, 4C, 1N) square-shaped macrocycles joined to each other in a grid-like arrangement and in which three corners are occupied by phosphorus atoms (Figure 2). The resulting network topology can be described by the {4,4} Schläfli symbol.

Geometry of hydrogen bonds.

| Interaction | Da-H (Å) | H···Ab (Å) | D···A (Å) | D-H···A (°) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| O-H···(NO) | 0.92(4) | 1.84(4) | 2.736(7) | 166(5) |

| O-H···O(NO) | 0.90(7) | 2.23(7) | 2.862(10) | 127(6) |

| O-H···O(PO3) | 0.91(3) | 1.84(3) | 2.733(6) | 168(6) |

| O-H···O(PO3) | 0.90(7) | 1.85(7) | 2.747(7) | 174(5) |

aHydrogen bond donor. bHydrogen bond acceptor.

Representation of the resulting supramolecular structure of 1 highlighting the square-shaped macrocycle organization.

Hydrogen bonds are shown by orange dashed lines. H atoms non-implicated in hydrogen bonding have been omitted for clarity (color code: Sn, green; P, pink; O, red; N, light blue; C, gray; H, yellow).

When evaporation conditions were speeded up by heating in a double boiler at 40°C, a yellow powder (2) was obtained instead of green crystals. The microanalysis of 2 suggests the formation of monosubstituted [C6 H11 NH3]+[(SnMe3)L]-. The IR spectrum recorded on this powder showed significant differences with the IR fingerprint of 1. We observed in particular the disappearance of the broad band located at 3514 cm-1 assigned to ν(OH). Moreover, the collected powder was very soluble in organic solvents. The 119Sn{1H} nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectrum recorded in solution (C6 D6) exhibits only one very broad signal at δ=-43 ppm. Such a value of chemical shift, in the range of -40 and -120 ppm, suggests, for a methyltin(IV) derivative, tetracoordination (Wrackmeyer, 1985, 2008). Moreover, Holecek and Lycka showed in the past that the coupling constant 1J(119,117Sn-13C) can be used as a tool to determine the type of geometry around a tin(IV) atom (Nadvornik et al., 1984). In our case, values of 1J(119,117Sn-13C) coupling constants (522, 546 Hz) are in agreement with a quasi-tetrahedral geometry for Sn. These spectroscopic data suggest in solution a discrete structure that could correspond to a SnMe3 moiety associated to a monodentate L ligand, with the negative charge on the resulting [(SnMe3)L]- anion compensated for by a cyclohexylammonium cation. In comparison to compound 1, we assume that the speeding up of the evaporation process by heating at 40°C has reduced the presence and implication of water (confirmed by the IR spectrum of 2). At the solid state, a polymeric organization seems very plausible, involving additional electronic donations of uncoordinated phosphato oxygen atoms to neighboring tin atoms. Currently, attempts of crystallization are under way in our laboratory to get single crystals from this powder in order to confirm unambiguously the proposed structure.

Finally, and from a mechanistic point of view, we suppose in solution an equilibrium implicating the three tin species (Me3 Sn)2 L (nonhydrated form of 1), [CyNH3]+L- and [(Me3 Sn)L]-[CyNH3]+ (2), and Me3 SnCl. Taking into account the reaction stoichiometry (L/Me3 SnCl=1:2), the neutral nonhydrated species 1 should be formed preferably, being also more soluble than charged 2. With slow evaporation, 1 hydrates (this lowers its solubility as hydrogen bonds form) and crystallizes. With a faster evaporation, 2 becomes the first to precipitate.

Conclusion

The reactivity between bis(cyclohexylammonium) 4-nitrophenylphosphate and Me3 SnCl was studied, leading to an unexpected supramolecular coordination 3-D network based on 4-NO2 C6 H4 PO4(SnMe3)2·H2 O building blocks (1). To our knowledge, such a self-assembly organization is unusual, and the complex 1 constitutes the first example of a 4-nitrophenylphosphatotin(IV) derivative. Further works are in progress to extend this study to other organotin(IV) precursors, focusing in particular on the nature and number of alkyl substituents bound to Sn.

Experimental

General

Bis(cyclohexylammonium) 4-nitrophenylphosphate was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Chemie GmbH, Steinheim, Germany and SnMe3 Cl was purchased from Merck Chemicals, Hohenbrunn bei München, Germany; both were used without any further purification. The elemental analyses (C, H, N) were performed at the Microanalyses Laboratory of the University of Bath (UK) and at the Institut de Chimie Moléculaire de l’Université de Bourgogne (Dijon, France). IR spectra were recorded on a Bruker FTIR Vector 22 spectrometer (Wissembourg, France) equipped with a Specac Golden Gate™ attenuated total reflectance (ATR) device and a Perkin-Elmer BX FTIR spectrometer (Waltham, MA, USA), using KBr pellets or Nujol mulls. Multinuclear NMR spectra (1H, 13C{1H}, 31P, 119Sn{1H}) were recorded on a 300 MHz Bruker Avance III NanoBay NMR spectrometer. Samples were dissolved in C6 D6 and the chemical shift scale of the spectrum was referenced to internal (CH3)4 Sn for 119Sn{1H} NMR spectra.

Synthesis of 4-NO2 C6 H4 PO4(SnMe3)2·H2 O (1)

An ethanolic solution of bis(cyclohexylammonium) 4-nitrophenylphosphate (0.300 g, 0.7187 mmol, 15 mL) was added dropwise to an ethanolic solution of SnMe3 Cl (0.286 g, 1.4373 mmol, 10 mL). After stirring at room temperature, the mixture was heated under reflux for 2 h. The resulting colorless solution was then filtered and submitted to a slow solvent evaporation at room temperature (25°C in Dakar). After 2 weeks, green single crystals were collected and characterized as 4-NO2 C6 H4 PO4(SnMe3)2·H2 O (1) (0.056 g, yield 27%). IR (KBr, cm-1): 3514 (m, br, νOH), 2935 (m, νCH), 1606 (m), 1591 (s), 1509 (s), 1494 (s), 1340 (s, νas NO2), 1259 (s, νP-O-C), 1172 (s, νs NO2), 1095 (vs, νP=O), 1007 (s), 896 (s), 773 (s), 741 (s), 692 (m). Anal. calculated for C12 H24 NO7 PSn2 (562.67): C 25.61; H 4.30; N 2.49; found: C 25.80; H 3.81; N 2.31%.

Synthesis of (CyNH3)[4-NO2 C6 H4 PO4(SnMe3)] (2)

The procedure is similar to that used for 1 and differs only by the evaporation condition of the solution obtained after heating under reflux. The evaporation process is speeded up by heating in a double boiler at 40°C. After 2 weeks, a yellow powder was collected. IR (ATR, cm-1): 2936 (s), 2859 (s), 1590 (s), 1509 (s), 1512 (s), 1491 (s), 1388 (m), 1341 (s, νas NO2), 1259 (s, νP-O-C), 1139 (s, νs NO2), 1109 (vs, νP=O), 984 (s), 879 (s), 896 (s), 777 (m), 756 (m), 724 (m), 693 (m), 645 (m), 618 (m), 572 (s), 550 (s). 1H NMR (ppm, C6 D6): 0.62 (s, H3 C-Sn, 2J(1H-119,117Sn)=70 Hz), 1.00 (m, Cy), 1.43 (m, Cy), 1.92 (m, Cy), 2.23 (m, Cy), 2.81 (m, Cy), 6.40 (m, br, Cy-NH3), 6.87 (m, Ph), 7.27 (m, Ph), 7.98 (m, Ph). 13C{1H} NMR (ppm, C6 D6): 3.2 (CH3-Sn, 1J(119,117Sn-13C)=546, 522 Hz), 24.4 (CH2-Cy), 25.1 (CH2-Cy), 30.9 (CH2-Cy), 50.0 (CH-Cy), 116.8 (CH-Ph), 120.3 (CH-Ph), 120.4 (CH-Ph), 139.0 (C-Ph), 141.7 (C-Ph), 161.1 (C-Ph), 161.2 (C-Ph), 167.0 (C-Ph). 119Sn{1H} NMR (ppm, C6 D6): -43 (br). 31P NMR (ppm, C6 D6): -0.5 (s, integral 60%), -6.2 (s, integral 20%), -8.0 (br, 117/119Sn satellites observed but not resolved, integral 18%) -18.2 (s, integral 2%). Anal. calculated for C15 H27 N2 O6 PSn (481.07): C 37.45; H 5.66; N 5.82; found: C 37.20; H 5.11; N 5.96%.

Crystal structure determination

Formula C12 H24 NO7 PSn2, M=562.67, green crystal: 0.4 mm×0.4 mm×0.4 mm, a=10.0219(2), b=10.3360(2), c=19.7286(4) Å, α=90°, β=90.201(2)°, γ=90°, V=2043.60(7) Å3, Dcalcd=1.829 g/cm3, μ=2.550 mm-1, Z=4, monoclinic, space group P21, λ=0.71073 Å, T=150(2) K, 37 930 reflections collected on a Nonius Kappa CCD diffractometer (index ranges: h: -13, 13; k: -14, 14; l: -27, 27), 10 866 independent (Rint=0.0558) and 10 866 observed reflections [I≥2σ(I)], 440 refined parameters, 7 restraints, R indices for observed reflections: R1=0.0358, wR2=0.0706, R indices for all data: R1=0.0470, wR2=0.0747, goodness of fit=1.034, maximum residual electron density 2.037 and -1.464 e/Å3. The structure was solved by SHELXS and refined by SHELXL (Sheldrick, 1986, 1997) using a full-matrix least-squares method based on F2. The asymmetric unit consists of two independent but essentially similar molecules. The absorption correction applied was semiempirical from equivalents. In the final cycles of least-squares refinement, all non-hydrogen atoms were allowed to vibrate anisotropically. Hydrogen atoms when included at calculated positions were relevant. The structural model converged successfully once 180° pseudo-merohedral twinning about the 001 direct lattice direction was taken into account. The fractional contribution for the twin components was 77:23 Hydrogen atoms attached to O(1) and O(8) were located in the difference Fourier map and were refined using geometric restraints.

Supporting information

Crystallographic data for the structure reported in this paper have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC), No. CCDC 789750 for 1. Copies of the data may be obtained free of charge from the Director, CCDC, 12 Union Road, Cambridge CB2 1EZ, UK (Fax: +44 1223 336 033; e-mail: deposit@ccdc.cam.ac.uk or www: http://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk).

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the Cheikh Anta Diop University of Dakar (Senegal), University of Bath (UK), the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS, France) and the University of Burgundy (Dijon, France).

References

Diallo, W.; Diop, C. A. K.; Diop, L.; Mahon, M. F.; Molloy, K. C.; Russo, U.; Biesemans, M.; Willem, R. Molecular structures of [(Ph3 Sn)2 O3 Se] and [(Ph3 Sn)2 O4 Cr](CH3 OH). J. Organomet. Chem. 2007, 692, 2187–2192.Search in Google Scholar

Diallo, W.; Okio, K. Y. A.; Diop, C. A. K.; Diop, L. A.; Diop, L.; Russo, U. New selenito SnPh3 residues containing complexes and adducts: synthesis and spectroscopic studies. Main Group Met. Chem. 2009, 32, 93–100.Search in Google Scholar

Evans, C. J.; Karpel, S. Organotin compounds in modern technology. In Journal of Organometallic Chemistry Library. Evans, C. J. and Karpel, S., Eds. Elsevier Science Ltd: Amsterdam, 1985; Vol. 16, pp. 1–279.Search in Google Scholar

Gajda, T.; Düpre, Y.; Török, I.; Harmer, J.; Schweiger, A.; Sander, J.; Kuppert, D.; Hegetschweiler, K. Highly efficient phosphodiester hydrolysis promoted by a dinuclear copper(II) complex. Inorg. Chem. 2001, 40, 4918–4927.Search in Google Scholar

Gueye, N.; Diop, L.; Molloy, K. C.; Kociok-Köhn, G. Crystal structure of C2 O4(SnPh3.dimethylformamide)2. Main Group Met. Chem. 2011, 34, 3–5.Search in Google Scholar

Hanif, M.; Hussain, A. M. S.; Bhatti, M. H.; Ahmed, M. S.; Mirz, B.; Evans, H. S. Synthesis, spectroscopic investigation, crystal structure, and biological screening, including antitumor activity, of organotin(IV) derivatives of piperonylic acid. Turk. J. Chem. 2007, 31, 349–361.Search in Google Scholar

Hassana, A. M. A.; Hanafy, A. I.; Alia, M. M.; Salmanb, A. A.; El-Shafayb, Z. A.; El-Wahabb, Z. H. A.; Salamab, I. A. Synthesis, characterization and catalytic activity of chromone derivative Schiff base complexes; rapid hydrolysis of phosphodiester in an aqueous medium. J. Basic Appl. Chem. 2012, 2, 1–11.Search in Google Scholar

Hengge, A. C.; Denu, J. M.; Dixon, J. E. Transition-state structures for the native dual-specific phosphatase VHR and D92N and S131A mutants. Contributions to the driving force for catalysis. Biochemistry 1996, 35, 7084–7092.Search in Google Scholar

Jones, P. G.; Sheldrick G. M.; Kirby A. J.; Abell K. W. Y. Bis(cyclohexylammonium) 4-nitrophenyl phosphate dihydrate, 2C6 H14 N+·C6 H4 NO6 P2-·2H2 O. Acta Crystallogr. 1984, C40, 550–552.Search in Google Scholar

Nadvornik, M.; Holecek, J.; Handlir, K.; Lycka, A. The carbon-13 and tin-119 NMR spectra of some four- and five-coordinate tri-n-butyltin(IV) compounds. J. Organomet. Chem. 1984, 275, 43–51.Search in Google Scholar

Rawji, G. H.; Yamada, M.; Sadler, N. P.; Milburn, R. M. Cobalt(III)-promoted hydrolysis of 4-nitrophenyl phosphate: the role of dinuclear species. Inorg. Chim. Acta. 2000, 303, 168–174.Search in Google Scholar

Sheldrick, G. M. SHELXS86. A Computer Program for Crystal Structure Determination; University of Gottingen: Germany, 1986.Search in Google Scholar

Sheldrick, G. M. SHELXL97. A Computer Program for Crystal Structure Refinement; University of Gottingen: Germany, 1997.Search in Google Scholar

Wrackmeyer B. 119Sn-NMR parameters. Annu. Rep. NMR Spectrosc. 1985, 16, 73–186.10.1016/S0066-4103(08)60226-4Search in Google Scholar

Wrackmeyer B. NMR of tin compounds. In Tin Chemistry – Fundamentals, Frontiers and Applications. Davies, A. G.; Gielen, M.; Pannell, K.; Tiekink, E., Eds. Wiley: Chichester, 2008, pp. 17–52.Search in Google Scholar

Yamami, M.; Furutachi, H.; Yokoyama, T.; Okawa, H. Hydrolytic function of a hydroxo-ZnIIPbII complex toward tris-p-nitrophenyl phosphate: a functional model of heterobimetallic phosphatases. Chem. Lett. 1998a, 27, 211–212.Search in Google Scholar

Yamami, M.; Furutachi, H.; Yokoyama, T.; Okawa, H. Macrocyclic heterodinuclear Zn(II)Pb(II) complexes: synthesis, structures, and hydrolytic function toward tris(p-nitrophenyl) phosphate. Inorg. Chem. 1998b, 37, 6832–6838.Search in Google Scholar

Yamazaki, A.; Kaya, S.; Tsuda, T.; Araki, Y.; Hayashi Y.; Taniguchi, K. An extra phosphorylation of Na+, K+-ATPase by paranitrophenylphosphate (pNPP): evidence for the oligomeric nature of the enzyme. J. Biochem. 1994, 116, 1360–1369.Search in Google Scholar

Yin, H.-D.; Wang, C.-H. Crystal and molecular structure of triphenyltin thiazole-2-carboxylate. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2004, 18, 411–412.Search in Google Scholar

Zhang, W.-L.; Ma, J.-F.; Jiang, H. μ-Isophthalato-bis[triphenyltin(IV)]. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. E: Struct. Rep. Online. 2006, 62, m460–m461.Search in Google Scholar

©2014 by Walter de Gruyter Berlin/Boston

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research articles

- Molecular structures of Sn(II) and Sn(IV) compounds with di-, tri- and tetramethylene bridged salen* type ligands

- Synthesis and structures of Cu-Cl-M adducts (M=Zn, Sn, Sb)

- Synthetic strategy for the incorporation of Bu2Sn(IV) into fluorinated β-diketones/benzoylacetone and sterically demanding heterocyclic β-diketones and spectroscopic characterization of hexacoordinated complexes of Bu2Sn(IV)

- Reactivity of bis(cyclohexylammonium) 4-nitrophenylphosphate with SnMe3 Cl. X-ray structure of 4-NO2 C6 H4 PO4(SnMe3)2·H2 O

- Structural elucidation of novel mixed ligand complexes of 2-thiophene carboxylic acid [M(TCA)2(H2O)x(im)2] [x=2 M: Mn(II), Co(II) or Cd(II), x=0 Cu(II)]

- Short Communication

- Synthesis and structure of the first tin(II) amidinato-guanidinate [DippNC(nBu)NDipp]Sn{pTol-NC[N(SiMe3)2]N-pTol}

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research articles

- Molecular structures of Sn(II) and Sn(IV) compounds with di-, tri- and tetramethylene bridged salen* type ligands

- Synthesis and structures of Cu-Cl-M adducts (M=Zn, Sn, Sb)

- Synthetic strategy for the incorporation of Bu2Sn(IV) into fluorinated β-diketones/benzoylacetone and sterically demanding heterocyclic β-diketones and spectroscopic characterization of hexacoordinated complexes of Bu2Sn(IV)

- Reactivity of bis(cyclohexylammonium) 4-nitrophenylphosphate with SnMe3 Cl. X-ray structure of 4-NO2 C6 H4 PO4(SnMe3)2·H2 O

- Structural elucidation of novel mixed ligand complexes of 2-thiophene carboxylic acid [M(TCA)2(H2O)x(im)2] [x=2 M: Mn(II), Co(II) or Cd(II), x=0 Cu(II)]

- Short Communication

- Synthesis and structure of the first tin(II) amidinato-guanidinate [DippNC(nBu)NDipp]Sn{pTol-NC[N(SiMe3)2]N-pTol}