Abstract

Physical motion is a key source domain for structuring abstract concepts, giving rise to metaphorical motion. Previous studies have produced varying conclusions about whether the typological properties of physical motion apply to metaphorical motion. This discrepancy underscores the need for investigations that consider different target domains and genres. Additionally, the focus has been on typical S- or V-languages, while serial-verb languages like Chinese remain under-explored. To address the gap, this study uses a constructional approach to examine the typological properties of Chinese metaphorical motion across target domains and genres. The findings reveal significant intra-linguistic variation, influenced by factors such as the semantic properties of target domains, the pragmatic context, and the structural characteristics of Chinese.

1 Introduction

Physical motion (i.e., spatial motion) serves as a crucial source domain for structuring abstract concepts like time and emotion, which gives rise to metaphorical motion (Lakoff and Johnson 1980; Özçalışkan 2003, 2004, 2005; Torres-Martínez 2022; Zlatev et al. 2012). In metaphorical motion, abstract concepts are conceptualized as moving entities (e.g., time flies) or locations with spatial configurations (e.g., we march into the new era; Chen and Wu 2023; Lewandowski and Özçalışkan 2023).

Earlier research on physical motion has categorized languages into verb-framed languages (V-languages) and satellite-framed languages (S-languages; Talmy 2000). However, whether the typological properties of physical motion apply to metaphorical motion remains debated (Caballero and Ibarretxe-Antuñano 2015; Feist and Duffy 2020; Lewandowski and Özçalışkan 2023; Özçalışkan 2004, 2005; Rojo and Valenzuela 2003). This discrepancy underscores the need for research across different target domains and genres. To date, no study has simultaneously examined these two variables. While most studies have emphasized crosslinguistic comparisons, few have addressed intra-linguistic variation in metaphorical motion. Moreover, the majority of research has concentrated on typical S- or V-languages, with less attention to serial-verb languages like Chinese. Chinese, in a transitional state from the V end toward the S end (Shi and Wu 2014), provides a unique context for examining intra-linguistic variation in both directions (Chen and Wu 2023). Therefore, this study investigates the typological properties of Chinese metaphorical motion across target domains and genres.

1.1 Expressions of physical motion events

A motion event is defined as comprising a framing event and a co-event (Talmy 2000). The former includes components of figure, ground, motion, and path, while the latter involves manner and cause. Based on how path, the framing component, is lexicalized, languages are divided into V-languages and S-languages. V-languages (e.g., Spanish and Turkish) encode path in the verb and manner in an adjunct, whereas S-languages (e.g., English and German) place path in a satellite, freeing the verb to express manner. To accommodate serial-verb languages like Chinese, Slobin (2004) adds a third category, equipollently-framed languages, where both path and manner are expressed in the verb phrase.

Building on this framework, scholars have conducted crosslinguistic research from inter-typological perspectives (i.e., variation between language types; e.g., Allen et al. 2007; Berman and Slobin 1994; Zlatev and Yangklang 2004) and intra-typological perspectives (i.e., variation within language types; e.g., Filipović 2007; Goschler and Stefanowitsch 2013; Slobin 2004). There is also increasing interest in intra-linguistic variation (i.e., variation within languages). For instance, in Spanish, manner verbs are found to be used when the event does not involve boundary crossing (Aske 1989; Slobin and Hoiting 1994). Other intra-linguistic differences based on manner type (e.g., punctual vs. extended; Naigles et al. 1998; Özçalışkan 2015), event type (e.g., self-motion vs. caused motion; Hendriks and Hickmann 2015; Lewandowski 2021; Rohde 2001), and register (Kashyap and Matthiessen 2019) are also highlighted.

Due to this intra-linguistic variation, researchers have shifted focus from categorizing languages to exploring constructions within them. Some have examined the interplay between verbs and constructions, arguing that motion event typology can be better explained through verb-construction combinability constraints (Lewandowski and Mateu 2020; Narasimhan 2003; Pedersen 2019). Nonetheless, these approaches do not discuss equipollently-framed constructions, which limits their comprehensiveness. Additionally, they pay little attention to the specific situation of each construction type within a language and the factors contributing to intra-linguistic variation.

By contrast, Croft et al. (2010) list all the possible construction types and analyze their use across various situations. They propose that along the scale of morphosyntactic integration in (1), which ranges from the most to the least integrated, certain situations tend to elicit more integrated constructions. Factors such as event type, verb type, aspect, transitivity, and pragmatic rules influence the choice of construction (Beavers et al. 2010; Croft et al. 2010; Hendriks and Hickmann 2015).

| Double framing, satellite framing < verb framing, compounding < coordination |

However, because Croft et al. only focus on five languages – English, Icelandic, Bulgarian, Japanese, and Dutch – they do not include the serial construction in (1), despite acknowledging its presence in languages like Chinese. To address this, we modify Croft et al.’s scale as shown in (2).

| Double framing, satellite framing < compounding, serial < verb framing < coordination |

Compared to (1), (2) places compounding and serial between satellite framing and verb framing. In satellite framing, the satellite expressing path is an obligatory, grammaticalized element fused with the main verb expressing manner, forming an indivisible unit. In compounding and serial constructions, two or more lexical verbs encoding manner and path co-occur but retain partial autonomy (e.g., allowing some syntactic flexibility: 跑了出去 pao3 le chu1qu4 ‘run-pfv-out’).[1] In verb framing, manner is expressed through an adjunct that can be omitted without affecting grammaticality. Therefore, compounding and serial constructions show intermediate syntactic integration, positioned lower than satellite framing but higher than verb framing. This revised scale offers a more comprehensive typological framework, which can accommodate a wider variety of languages and provide clearer insights into intra-linguistic variation.

1.2 Expressions of metaphorical motion events

Most previous research on the lexicalization of metaphorical motion in typologically different languages suggests that crosslinguistic variation in physical motion largely extends to metaphorical motion. Specifically, in metaphorical motion, S-languages (e.g., English, German, Polish) use a broader range and higher frequency of manner verbs, while V-languages (e.g., Greek, Spanish, Turkish) rely more on path verbs (Caballero and Ibarretxe-Antuñano 2015; Cifuentes-Férez 2014; Katis and Selimis 2005; Lewandowski and Özçalışkan 2023; Özçalışkan 2004, 2005; Wilson 2005).

However, some studies present different findings. Rojo and Valenzuela (2003) find that in fictive motion (i.e., metaphorical conceptualization of perception as moving objects; e.g., the road winds through the mountains), English speakers, like their Spanish counterparts, primarily use path verbs, which deviates from physical motion patterns. Similarly, Feist and Duffy (2020) observe a preference for path verbs in English over Spanish in metaphorical motion of time. Additionally, Chen and Wu (2023) demonstrate that in Chinese, the typological properties of metaphorical motion differ from those of physical motion and vary between fiction and nonfiction.

These findings echo previous studies that call for considering target domains and genres in metaphorical motion (Caballero 2017; Kashyap and Matthiessen 2019). No study has yet addressed both variables within a single framework. Furthermore, most research has focused on typical S- or V-languages, with limited attention to serial-verb languages like Chinese. Therefore, this paper examines the lexicalization patterns of Chinese metaphorical motion across target domains and genres with reference to scale (2). We believe this revised scale will reveal the variation within Chinese more clearly. Note that the focus of this study is the distribution of constructions based on differing preferences for manner or path verbs in metaphorical motion across target domains and genres. Thus, the construction types are investigated independently, not in the clustering shown on the scale (2).

2 Methodology

2.1 Data collection

This study examines metaphorical motion with actual motion as a reference, using data from the Lancaster Corpus of Mandarin Chinese (LCMC). The one-million-word corpus includes categories of reportage, editorials, reviews, religion, skills/trades/hobbies, official documents, academic prose, and fiction (McEnery and Xiao 2003).

By combing through two dictionaries of Mandarin Chinese (Dong 2007; Guo 1994) and prior studies on Chinese motion (e.g., Chen and Guo 2009; Chu 2004; Lin 2019; Shi and Wu 2014), we found 148 motion verbs and searched each verb in LCMC. To identify metaphorical motion, we followed Chen and Wu’s (2023) method, which was adapted from Pragglejaz (2007): (a) identify the contextual meaning of the verb; (b) assess if the contextual meaning contrasts with the basic meaning of motion and can be understood comparatively; (c) if so, mark the expression as metaphorical motion. To avoid overgeneralization, this paper focuses on self-motion, deferring caused motion for future study. A total of 636 metaphorical motion clauses and 3,207 actual motion clauses were identified. For comparison, 636 actual motion clauses were randomly selected from the 3,207.

2.2 Data coding

The clauses were coded by two native Chinese speakers in three aspects: target domains, motion verbs, and event constructions. The original percentage of agreement was 97 %. All disagreements were resolved through discussion.

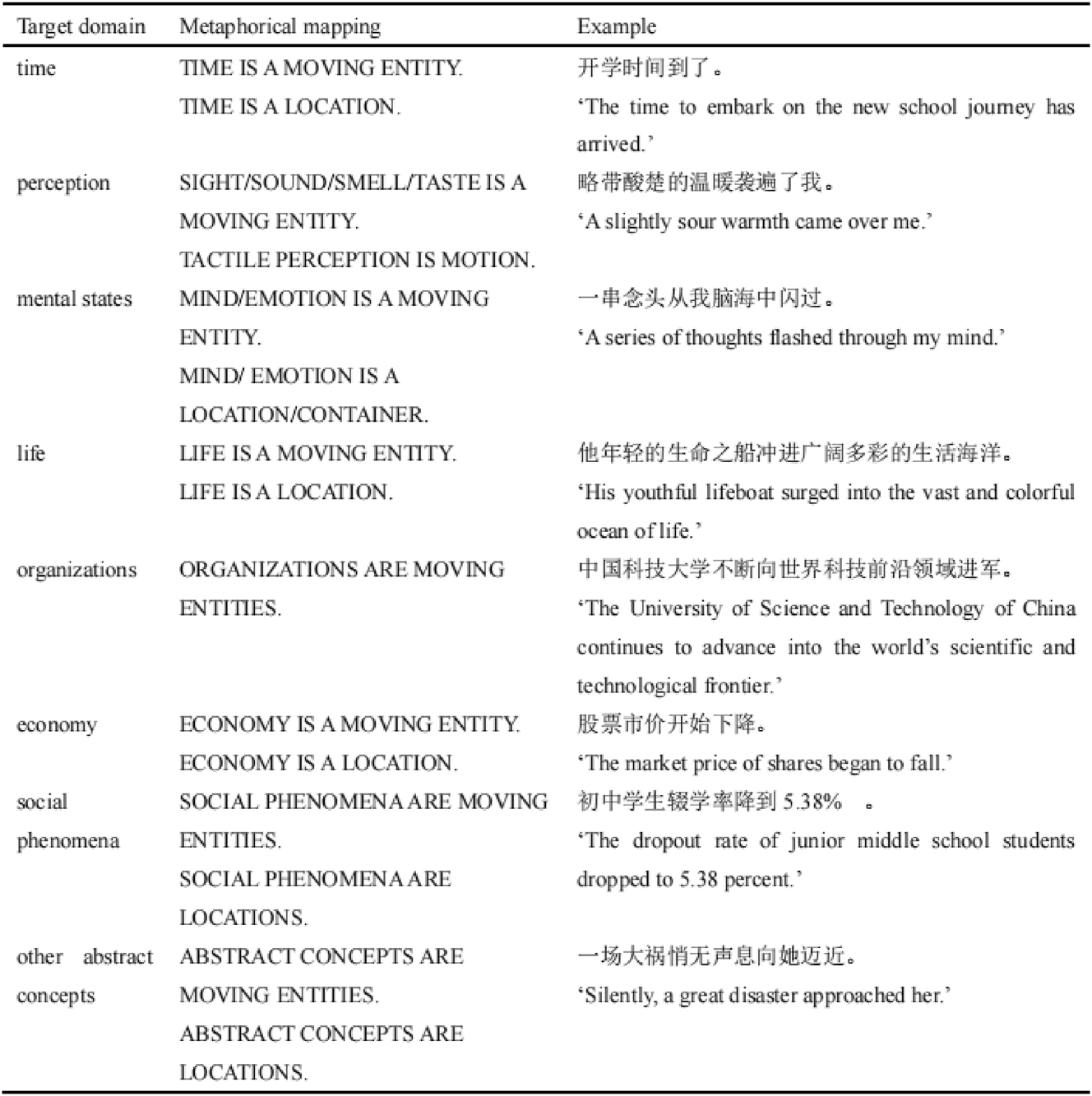

Based on previous studies on metaphorical motion (Lewandowski and Özçalışkan 2023; Özçalışkan 2003; Shan and Onchoke 2018), this study classified target domains of metaphorical motion into several types, as shown in Table 1. Among them, “other abstract concepts” refers to less common types, like disaster, plot, and opportunity.

Target domains of Chinese metaphorical motion.

There are four types of motion verb. Manner verbs describe subsidiary action or state that a figure manifests during motion (e.g., 飞 fei1 ‘fly’). Path verbs depict the course that a figure takes, usually in relation to the ground (e.g., 出 chu1 ‘exit’). Neutral verbs come in two forms: the first simply expresses the movement of a figure, like 行 xing2 ‘move’; the second originally encodes non-translational action but expresses manner of motion in constructions, such as 躲 duo3 ‘hide’ in 躲入 duo3ru4 ‘hide into’. Additionally, there are two deictic verbs: 来 lai2 ‘come’ denotes motion toward the speaker, and 去 qu4 ‘go’ refers to motion away from the speaker.

These motion verbs occur alone or in combination, resulting in six types of event constructions: verb framing (VF), satellite framing (SF), serial, coordinate (CD), compounding (CP), and double framing (DF; Croft et al. 2010). In verb framing like (3), path is encoded in the verb (到 dao4 ‘arrive’), whereas manner is expressed by an adjunct (迅速 xun4su4 ‘quickly’). In satellite framing like (4), manner is lexicalized in the verb (飞 fei1 ‘fly’), but path is connected with a directional preposition (向 xiang4 ‘toward’).[2] Certain serial-verb structures also exhibit satellite framing (Talmy 2009). In (5), 过 guo4 as V2 in 闪过 shan3guo4 ‘flash through’ conveys a path concept and the experiential aspect of having already V-ed. However, when used alone, this verb changes meaning to indicate that the figure’s motion was part of a sequence observed from a distance (Talmy 2009). Hence, 闪过 shan3guo4 is a satellite framing construction. A serial-verb structure can be considered a serial construction (i.e., symmetrical encoding) only when the meaning of the morpheme as V2 aligns with its meaning in single-verb usage, like 冒出 mao4chu1 ‘emit’ in (6).

| 日本 | 经济 | 迅速 | 到 | 了 | 崩溃 | 边缘。 |

| Ri4ben3 | jing1ji4 | xun4su4 | dao4 | le | beng1kui4 | bian1yuan2. |

| Japan | economy | quickly | arrive | pfv | collapse | brink |

| ‘The economy of Japan quickly arrived at the brink of collapse.’ | ||||||

| 友谊 | 之 | 歌 | 飞 | 向 | 21 | 世纪。 |

| You3yi4 | zhi | ge1 | fei1 | xiang4 | 21 | shi4ji4. |

| friendship | assoc | song | fly | toward | 21 | century |

| ‘The song of friendship flies toward the twenty-first century.’ | ||||||

| 一 | 串 | 念头 | 从 | 我 | 脑海 | 中 | 闪过。 |

| Yi2 | chuan4 | nian4tou2 | cong2 | wo3 | nao3hai3 | zhong1 | shan3guo4. |

| one | cl | thought | from | me | mind | inside | flash_through |

| ‘A series of thoughts flashed through my mind.’ | |||||||

| 他 | 心 | 中 | 冒出 | 一 | 个 | 邪恶 | 的 | 念头。 |

| Ta1 | xin1 | zhong1 | mao4chu1 | yi2 | ge4 | xie2e4 | de | nian4tou2. |

| he | mind | inside | emit_out | one | cl | evil | assoc | thought |

| ‘An evil thought came into his mind.’ | ||||||||

Other symmetric constructions include compounding and coordination. In compounding, two verbs are morphologically bound and more tightly integrated than in serial constructions (Croft et al. 2010). For instance, in (7), the two verbs are morphologically bound; the neutral verb 刺 ci4 ‘prick’, which typically denotes non-translational action, acquires the meaning of manner of motion when combined with the path verb. By contrast, in coordination like (8), two components are combined with less integration than in serial constructions.

| 一 | 道 | 贪婪 | 的 | 目光 | 刺到 | 脸 | 上。 |

| Yi2 | dao4 | tan1lan2 | de | mu4guang1 | ci4dao4 | lian3 | shang4. |

| one | cl | greedy | assoc | glance | pierce_to | face | up |

| ‘A greedy glance pierced his face.’ | |||||||

| 一 | 股 | 欲火 | 腾扑 | 上来。 |

| Yi4 | gu3 | yu4huo3 | teng2pu1 | shang4lai2. |

| one | cl | fire_of_desire | pounce | come_up |

| ‘A wave of desire surged up.’ | ||||

Finally, double framing involves expressing path twice: once within the verb and once as a separate satellite (Croft et al. 2010). This results in an asymmetrical structure, as illustrated in (9), where path is conveyed by the verb 离 li2 ‘leave’ and the satellite 开 kai1 ‘away’.[3]

| 他 | 带 | 着 | 遗憾 | 离开 | 了 | 人世。 |

| Ta1 | dai4 | zhe | yi2han4 | li2kai1 | le | ren2shi4. |

| he | carry | dur | regret | leave_away | pfv | world |

| ‘He left the world with regret.’ | ||||||

3 Results

3.1 Metaphorical motion across target domains

Constructions that encode Chinese metaphorical motion across target domains are presented in Table 2. It shows that there exists significant variation in their distribution (χ2(42) = 179.45, p < 0.001). In the target domains of life, perception, organizations, and mental states, satellite framing is the dominant lexicalization pattern, whose percentage exceeds 50 %. It is followed by serial and verb framing. However, metaphorical motion of economy, social phenomena, time, and other abstract concepts presents a different picture. The proportion of satellite framing drops below 50 %, while the percentage of verb framing increases significantly. This is especially the case in the target domain of time, where satellite framing accounts for merely 14.29 %, whereas verb framing makes up 71.43 %. With the ranking of target domains, the domain at the top (i.e., life) uses the highest proportion of satellite framing constructions, which are on the far left of the scale in (2). As one goes down, target domains lower in the column use more constructions lower on the scale in (2).

Constructions of Chinese metaphorical motion across target domains.

| Target domain | DF | SF | CP | Serial | VF | CD | Othersa | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Life | 0.80 % | 69.60 % | 1.60 % | 16.00 % | 9.60 % | 2.40 % | 0.00 % | 100.00 % |

| (1)b | (87) | (2) | (20) | (12) | (3) | (0) | (125) | |

| Perception | 0.92 % | 68.81 % | 2.75 % | 17.43 % | 5.50 % | 4.59 % | 0.00 % | 100.00 % |

| (1) | (75) | (3) | (19) | (6) | (5) | (0) | (109) | |

| Organizations | 0.00 % | 62.50 % | 4.17 % | 27.78 % | 4.17 % | 0.00 % | 1.39 % | 100.00 % |

| (0) | (45) | (3) | (20) | (3) | (0) | (1) | (72) | |

| Mental states | 0.00 % | 59.52 % | 3.57 % | 17.86 % | 11.90 % | 7.14 % | 0.00 % | 100.00 % |

| (0) | (50) | (3) | (15) | (10) | (6) | (0) | (84) | |

| Economy | 4.00 % | 40.00 % | 2.00 % | 17.00 % | 35.00 % | 2.00 % | 0.00 % | 100.00 % |

| (4) | (40) | (2) | (17) | (35) | (2) | (0) | (100) | |

| Other abstract concepts | 2.90 % | 33.33 % | 5.80 % | 24.64 % | 26.09 % | 5.80 % | 1.45 % | 100.00 % |

| (2) | (23) | (4) | (17) | (18) | (4) | (1) | (69) | |

| Social phenomena | 4.76 % | 23.81 % | 4.76 % | 19.05 % | 33.33 % | 14.29 % | 0.00 % | 100.00 % |

| (2) | (10) | (2) | (8) | (14) | (6) | (0) | (42) | |

| Time | 5.71 % | 14.29 % | 0.00 % | 2.86 % | 71.43 % | 5.71 % | 0.00 % | 100.00 % |

| (2) | (5) | (0) | (1) | (25) | (2) | (0) | (35) |

-

aThe category of “others” includes constructions like 祸不单行 huo4bu4dan1xing2 ‘misfortunes do not come alone’, which use a neutral verb to express movement without adding nuances like manner or path. bThe numbers in parentheses indicate frequencies.

In contrast to actual motion, depicted in Table 3, metaphorical motion involving domains of life, perception, organizations, and mental states has more satellite framing (χ2(4) = 31.44, p < 0.001) but fewer verb framing constructions (χ2(4) = 42.00, p < 0.001). However, the situation is reversed in metaphorical motion related to economy, social phenomena, time, and other abstract concepts (satellite framing: χ2(4) = 41.58, p < 0.001; verb framing: χ2(4) = 64.71, p < 0.001). In sum, metaphorical motion across target domains exhibits variation in both directions compared with actual motion.

Constructions of Chinese actual motion.

| DF | SF | CP | Serial | VF | CD | Others | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actual motion | 1.10 % | 51.89 % | 5.35 % | 19.03 % | 21.38 % | 0.63 % | 0.63 % | 100.00 % |

| (7) | (330) | (34) | (121) | (136) | (4) | (4) | (636) |

Tables 4 and 5 display the proportion of motion verbs in metaphorical motion and actual motion, respectively. In line with the distribution of constructions, there is a significant difference in the distribution of motion verbs across target domains (χ2(14) = 71.2, p < 0.001). Metaphorical motion involving domains of life, perception, organizations, and mental states exhibits a higher frequency of manner verbs (χ2(4) = 23.62, p < 0.001) but a lower frequency of path verbs (χ2(4) = 19.40, p < 0.001) compared to actual motion. Conversely, metaphorical motion related to domains of economy, social phenomena, time, and other abstract concepts shows a higher frequency of path verbs (χ2(4) = 24.54, p < 0.001) but a lower frequency of manner verbs (χ2(4) = 25.73, p < 0.001). Notably, when it comes to metaphorical motion of time, manner verbs account for only 15.22 %, while path verbs make up 84.78 %. This finding aligns with Feist and Duffy’s (2020) research, which indicates a preference for path verbs in temporal motion in both English and Spanish.

Motion verbs of Chinese metaphorical motion across target domains.

| Target domain | Manner verbs | Path verbs | Neutral verbs | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organizations | 64.42 % (67) | 35.58 % (37) | 0.00 % (0) | 100.00 % (104) |

| Life | 57.22 % (107) | 41.18 % (77) | 1.60 % (3) | 100.00 % (187) |

| Perception | 56.25 % (99) | 42.05 % (74) | 1.70 % (3) | 100.00 % (176) |

| Mental states | 50.70 % (72) | 46.48 % (66) | 2.82 % (4) | 100.00 % (142) |

| Economy | 39.74 % (60) | 57.62 % (87) | 2.65 % (4) | 100.00 % (151) |

| Other abstract concepts | 39.47 % (45) | 57.02 % (65) | 3.51 % (4) | 100.00 % (114) |

| Social phenomena | 28.05 % (23) | 65.85 % (54) | 6.10 % (5) | 100.00 % (82) |

| Time | 15.22 % (7) | 84.78 % (39) | 0.00 % (0) | 100.00 % (46) |

Motion verbs of Chinese actual motion.

| Manner verbs | Path verbs | Neutral verbs | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actual motion | 45.50 % (470) | 52.08 % (538) | 2.42 % (25) | 100.00 % (1033) |

3.2 Metaphorical motion across genres

Table 6 presents constructions encoding Chinese metaphorical motion across genres, whose distribution exhibits a pronounced difference (χ2(25) = 81.57, p < 0.001). In reviews, editorials, and fiction, satellite framing predominates, with percentages above 50 %. It is followed by serial and verb framing. By contrast, in reportage, official documents, and academic prose, the percentage of satellite framing drops below 50 %, while the proportion of verb framing increases pronouncedly. It is interesting to note that although reportage, editorials, and reviews all come from the press, they present significant variation. Reportage has more verb framing but fewer satellite framing constructions than reviews and editorials (verb framing: χ2(2) = 9.32, p < 0.01; satellite framing: χ2(2) = 11.33, p < 0.01). When it comes to the ranking of genres, reviews have the highest percentage of satellite framing constructions, which are on the far left of the scale in (2). As one moves down, genres lower in the column use more constructions lower on the scale in (2).

Constructions of Chinese metaphorical motion across genres.

| Genre | DF | SF | CP | Serial | VF | CD | Others | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Press: reviews | 0.00 % | 74.19 % | 0.00 % | 12.90 % | 6.45 % | 6.45 % | 0.00 % | 100.00 % |

| (0) | (23) | (0) | (4) | (2) | (2) | (0) | (31) | |

| Press: editorials | 1.96 % | 68.63 % | 0.00 % | 15.69 % | 11.76 % | 0.00 % | 1.96 % | 100.00 % |

| (1) | (35) | (0) | (8) | (6) | (0) | (1) | (51) | |

| Fictiona | 1.21 % | 57.58 % | 3.03 % | 16.36 % | 14.85 % | 6.67 % | 0.30 % | 100.00 % |

| (4) | (190) | (10) | (54) | (49) | (22) | (1) | (330) | |

| Press: reportage | 2.33 % | 45.35 % | 4.65 % | 17.44 % | 27.91 % | 2.33 % | 0.00 % | 100.00 % |

| (2) | (39) | (4) | (15) | (24) | (2) | (0) | (86) | |

| Reports/official documents | 7.32 % | 36.59 % | 0.00 % | 14.63 % | 39.02 % | 2.44 % | 0.00 % | 100.00 % |

| (3) | (15) | (0) | (6) | (16) | (1) | (0) | (41) | |

| Academic prose | 3.08 % | 26.15 % | 7.69 % | 38.46 % | 24.62 % | 0.00 % | 0.00 % | 100.00 % |

| (2) | (17) | (5) | (25) | (16) | (0) | (0) | (65) | |

| Religionb | 0.00 % | 50.00 % | 0.00 % | 16.67 % | 27.78 % | 5.56 % | 0.00 % | 100.00 % |

| (0) | (9) | (0) | (3) | (5) | (1) | (0) | (18) | |

| Skills, trades, and hobbiesb | 0.00 % | 50.00 % | 0.00 % | 14.29 % | 35.71 % | 0.00 % | 0.00 % | 100.00 % |

| (0) | (7) | (0) | (2) | (5) | (0) | (0) | (14) |

-

aFiction includes the categories of general fiction, detective fiction, science fiction, martial arts fiction, romantic fiction, popular lore, biographical stories, and humorous stories in LCMC. bBecause metaphorical motion expressions in the genres of religion and skills/trades/hobbies have a low frequency, they are excluded from the discussion.

Compared to actual motion, illustrated in Table 2, metaphorical motion in reviews, editorials, and fiction shows a higher frequency of satellite framing (χ2(3) = 11.81, p < 0.01) but a lower frequency of verb framing constructions (χ2(3) = 10.98, p < 0.05). However, the opposite pattern is observed in metaphorical motion in reportage, official documents, and academic prose (satellite framing: χ2(3) = 18.59, p < 0.001; verb framing: χ2(3) = 8.09, p < 0.05). Overall, metaphorical motion across genres displays variation in both directions in contrast to actual motion.

Table 7 demonstrates the percentage of motion verbs across genres. Consistent with the distribution of constructions, there is notable variation in the distribution of motion verbs (χ2(10) = 49.60, p < 0.001). Compared with actual motion in Table 5, metaphorical motion in reviews, editorials, and fiction shows a higher percentage of manner verbs (χ2(3) = 20.63, p < 0.001) but a lower percentage of path verbs (χ2(3) = 20.16, p < 0.001). However, the situation is reversed in reportage, academic prose, and official documents (manner verbs: χ2(3) = 13.95, p < 0.01; path verbs: χ2(3) = 16.77, p < 0.001).

Motion verbs of Chinese metaphorical motion across genres.

| Genre | Manner verbs | Path verbs | Neutral verbs | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Press: reviews | 75.68 % (28) | 24.32 % (9) | 0.00 % (0) | 100.00 % (37) |

| Press: editorials | 54.79 % (40) | 41.10 % (30) | 4.11 % (3) | 100.00 % (73) |

| Fiction | 53.49 % (268) | 43.71 % (219) | 2.79 % (14) | 100.00 % (501) |

| Press: reportage | 41.79 % (56) | 55.97 % (75) | 2.24 % (3) | 100.00 % (134) |

| Academic prose | 36.72 % (47) | 60.94 % (78) | 2.34 % (3) | 100.00 % (128) |

| Reports/official documents | 26.51 % (22) | 73.49 % (61) | 0.00 % (0) | 100.00 % (83) |

3.3 Interaction between target domains and genres

To check whether there are independent main effects of domain and genre, this study investigates the distribution of domains across genres.

Table 8 reveals that domains are unequally distributed across genres. For example, fiction emphasizes the domains of life, perception, and mental states. In addition, the “sum1” column shows that reviews, the top genre, has the highest combined percentage of metaphorical motion related to life, perception, organizations, and mental states. As demonstrated in Table 2, these domains are the top four in the proportion of satellite framing constructions. Moving down the column, the combined percentage in “sum1” decreases. Conversely, the combined percentage of metaphorical motion of economy, social phenomena, time, and other abstract concepts, which lead in the proportion of verb framing constructions, show an increasing pattern in the “sum2” column. This suggests that certain genres favor metaphorical motion tied to specific target domains, indicating a potential dependent effect between target domain and genre on the distribution of constructions.

The distribution of domains across genres.

| Organizations | Life | Perception | Mental states | sum1 | Economy | Other abstract concepts | Social phenomena | Time | sum2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Press: reviews | 51.61 % | 22.58 % | 3.23 % | 6.45 % | 83.87 % | 16.13 % | 0.00 % | 0.00 % | 0.00 % | 16.13 % |

| (16) | (7) | (1) | (2) | (26) | (5) | (0) | (0) | (0) | (5) | |

| Fiction | 3.03 % | 24.55 % | 26.97 % | 21.21 % | 75.76 % | 6.67 % | 10.00 % | 2.73 % | 4.85 % | 24.24 % |

| (10) | (81) | (89) | (70) | (250) | (22) | (33) | (9) | (16) | (80) | |

| Press: editorials | 33.33 % | 19.61 % | 3.92 % | 0.00 % | 56.86 % | 37.25 % | 1.96 % | 1.96 % | 1.96 % | 43.14 % |

| (17) | (10) | (2) | (0) | (29) | (19) | (1) | (1) | (1) | (22) | |

| Press: reportage | 17.44 % | 13.95 % | 17.44 % | 6.98 % | 55.81 % | 20.93 % | 5.81 % | 2.33 % | 15.12 % | 44.19 % |

| (15) | (12) | (15) | (6) | (48) | (18) | (5) | (2) | (13) | (38) | |

| Reports/official documents | 19.51 % | 14.63 % | 0.00 % | 2.44 % | 36.59 % | 31.71 % | 2.44 % | 29.27 % | 0.00 % | 63.41 % |

| (8) | (6) | (0) | (1) | (15) | (13) | (1) | (12) | (0) | (26) | |

| Academic prose | 9.23 % | 4.26 % | 0.00 % | 7.69 % | 21.54 % | 23.08 % | 41.54 % | 10.77 % | 3.08 % | 78.46 % |

| (6) | (3) | (0) | (5) | (14) | (15) | (27) | (7) | (2) | (51) |

To further verify this, we examine the respective distribution of the top three frequent constructions – satellite framing, verb framing, and serial constructions – across domains and genres, as shown in Table 9.[4] The chi-square tests (satellite framing: χ2(35) = 161.65, p < 0.001; verb framing: χ2(35) = 83.70, p < 0.001; serial: χ2(35) = 107.81, p < 0.001) demonstrate that domain and genre, in concert with one another, influence the choice of constructions in metaphorical motion.

The respective distribution of satellite framing, verb framing, and serial constructions across domains and genres.

| Fiction | Press: editorials | Press: reviews | Press: reportage | Reports/official documents | Academic prose | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Life | SF | 54 | 8 | 6 | 7 | 5 | 2 |

| VF | 9 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| Serial | 12 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Perception | SF | 60 | 2 | 1 | 11 | 0 | 0 |

| VF | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | |

| Serial | 1 | 3 | 4 | 0 | 3 | 6 | |

| Mental states | SF | 45 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| VF | 6 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | |

| Serial | 17 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Organizations | SF | 2 | 14 | 12 | 8 | 6 | 3 |

| VF | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| Serial | 12 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | |

| Economy | SF | 15 | 9 | 4 | 6 | 1 | 2 |

| VF | 5 | 5 | 0 | 6 | 8 | 6 | |

| Serial | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12 | |

| Social phenomena | SF | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| VF | 3 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 2 | |

| Serial | 7 | 6 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | |

| Time | SF | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| VF | 11 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 2 | |

| Serial | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3 | |

| Other abstract concepts | SF | 12 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 6 |

| VF | 11 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 5 | |

| Serial | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

4 Discussion

This study has investigated the typological properties of Chinese metaphorical motion across target domains and genres. In terms of target domains, along the motion event typology scale expressed in (2), metaphorical motion related to life is the closest to the left, followed by perception, organizations, mental states, economy, social phenomena, and time. In terms of genres, metaphorical motion from reviews ranks closest to the left, followed by editorials, fiction, reportage, academic prose, and official documents. Moreover, because domains are unevenly distributed across genres, there are dependent main effects of domain and genre on the distribution of constructions. These findings align with Croft et al.’s (2010) claim of a shift in typological research from classifying entire languages, which often leads to labeling them as “mixed” types, to typologizing specific situation types within a language.

Chen and Wu (2023) indicate that in Chinese, metaphorical motion from fiction attracts more constructions on the left, followed by actual motion and metaphorical motion from nonfiction. By contrast, our study conducts a more detailed classification by using the original LCMC categories instead of the broad concept of nonfiction. We have found that reviews and editorials, which are considered nonfiction in Chen and Wu (2023), have more satellite framing constructions than fiction. This suggests that although nonfiction tends to lean toward constructions on the right end of the scale overall (Chen and Wu 2023), the internal situation is much more complex and requires a detailed analysis rather than a generalization.

Several factors contribute to the variation in Chinese metaphorical motion. To begin with, the semantic properties of target domains influence the choice of verb types and construction types, which are deeply interrelated (Caballero 2017). Domains such as life, perception, and mental states are highly subjective and inherently complex, posing challenges for linguistic expression (Caballero 2007). To bridge this gap, these domains rely heavily on manner verbs that describe how motion is conducted (Slobin 2006). When applied metaphorically, manner verbs illuminate abstract state changes across dimensions like mode (e.g., 跳 tiao4 ‘jump’), rate (e.g., 冲 chong1 ‘rush’), intensity (e.g., 涌 yong3 ‘gush’), and force (e.g., 落 luo4 ‘fall’). Furthermore, these domains exhibit distinct preferences for specific types of manner verbs. For instance, the domain of mental states favors verbs that suggest liquid motion, such as 沉 chen2 ‘sink’, 浸 jin4 ‘soak’, 浮 fu2 ‘float’, 溢 yi4 ‘spill’, and 涌 yong3 ‘gush’. This preference arises from the conceptual analogy between mental states and liquids – both are dynamic, pervasive, and deeply interconnected. In (10), the manner verb 涌 yong3 ‘surge’ vividly captures a sudden rush of complex emotion, akin to a liquid surge. Such reliance on manner verbs aligns with satellite framing constructions, which provide the syntactic space to encode manner, ultimately leading to a higher proportion of these constructions and a leftward shift along the scale.[5]

| 新 | 仇 | 旧 | 恨 | 涌上 | 心头。 |

| Xin1 | chou2 | jiu4 | hen4 | yong3shang4 | xin1tou2. |

| new | hatred | old | hatred | gush_up | heart |

| ‘Old and new hatred gushed up in my heart.’ | |||||

The high frequency of manner verbs in metaphorical motion of perception is consistent with Caballero’s (2007) study of English but contrasts with Rojo and Valenzuela’s (2003) findings for English and Spanish. One possible explanation for this difference is the methodologies used. Rojo and Valenzuela (2003) employ an elicitation-by-drawings method, asking participants to instruct an artist to include missing paths. This approach may have prompted participants to focus on path and use path verbs. Another likely reason could be the nature of fictive motion, which describes spatial configurations by evoking the motion of perception along a path (Lewandowski and Özçalışkan 2023). In such a case, manner verbs are only used if they correlate with some property of path (manner condition; Matsumoto 1996). By contrast, in both our and Caballero’s (2007) studies, much of the metaphorical motion related to perception does not describe stationary circumstances in physical space. Instead, it involves sound, smell, and taste, thereby rendering the manner condition less applicable.

On the other hand, the domain of time, typically conceptualized as linear and continuous, favors path verbs that emphasize trajectory. This linear perspective is absent in manner verbs, which focus on how movement occurs rather than its direction. Furthermore, foregrounding path in the conceptualization of time directs attention to the ground instead of the figure, as a path presupposes a ground against which it is described. This focus reduces the use of manner verbs, which depict co-events performed by the figure (Feist and Duffy 2020). Consequently, the emphasis on path verbs and restricted employment of manner verbs results in a greater frequency of verb framing constructions, leading to variation in the rightward direction.

Beyond the inherent semantic characteristics of target domains, the pragmatic context also plays a crucial role in shaping verb and construction selection. Different genres serve distinct communicative purposes, and metaphor aids in achieving these goals (Semino et al. 2013). Reviews and editorials aim to describe, evaluate, and persuade, while fiction focuses on description and evoking emotional responses. In these genres, manner verbs are predominantly used to craft dynamic narratives that engage readers, convey subjective evaluations, and enhance dramatic effects (Caballero 2017). As a result, the frequency of satellite framing constructions increases. By contrast, genres prioritizing factual reporting, information transmission, and objectivity – such as reportage, official documents, and academic prose – favor path verbs, as they denote the result of changes (Chen and Wu 2023) and align with the goal of providing clear and direct information. This preference for path verbs naturally leads to an increase in verb framing constructions.

These two factors – target domain properties and pragmatic context – often interact to influence verb and construction preferences. For example, metaphorical motion of organizations evokes the broader metaphor organizations are human beings, which emphasizes the figure. Since manner verbs describe co-events performed by the figure, they naturally become more prominent in such contexts. Additionally, metaphorical motion of organizations is frequently found in editorials and reviews. The communicative goals of these genres foster the use of manner verbs to convey underlying values and attitudes. For instance, when describing an organization, two concepts – 勇攀高峰 yong3pan1gao1feng1 ‘scale new heights’ and 越过规矩 yue4guo4gui1ju3 ‘violate the rules’ – reflect different organizational values and approaches. Thus, the inherent semantic property of the target domain and the communicative goals of editorials and reviews work together to influence the use of manner verbs and their corresponding satellite framing constructions.

The third factor concerns the structural properties of Chinese (Chen and Wu 2023), specifically the availability of morphosyntactic and lexical resources for expressing motion (Beavers et al. 2010). Since Chinese has not fully transitioned from a V-language to an S-language, a wide range of old and new constructions coexist (Shi and Wu 2014). This diversity grants writers considerable flexibility in choosing expressions for metaphorical motion according to their communicative needs. In contrast, although S- and V-languages also have satellite framing and verb framing constructions, their distribution is highly imbalanced, with certain ones being more restricted. For example, in Spanish, manner verbs in satellite framing can be used only when the event does not involve boundary crossing (Aske 1989; Slobin and Hoiting 1994). Hence, unlike Chinese, the typological properties of physical motion in these languages apply more consistently to metaphorical motion (Caballero and Ibarretxe-Antuñano 2015; Cifuentes-Férez 2014; Katis and Selimis 2005; Lewandowski and Özçalışkan 2023; Özçalışkan 2004, 2005; Wilson 2005).

5 Conclusions

This paper contributes to the study of motion event encoding by highlighting intra-linguistic variation. It explores the typological properties of metaphorical motion across different target domains and genres, a perspective that has not been systematically addressed before. The findings reveal considerable variation in Chinese, showing that the typological features of physical motion do not always extend to metaphorical motion. Key factors influencing this variation are identified, including the semantic properties of target domains, the pragmatic context, and the structural characteristics of Chinese. This intra-linguistic variation indicates that elements of physical motion are selectively transferred to metaphorical motion, with a focus on features most relevant to the target domain (Feist and Duffy 2020). It also demonstrates the context-sensitive nature of language patterns, underscoring the role of genre in developing a comprehensive typology of motion events (Caballero 2017; Caballero and Ibarretxe-Antuñano 2015).

In addition, this study enhances Croft et al.’s (2010) scale of morphosyntactic integration for greater comprehensiveness, supporting their call for typologizing specific situation types rather than entire languages. However, it is important to note that this paper focuses on the varying distribution of constructions arising from distinct preferences for manner or path verbs of metaphorical motion across target domains and genres, which are driven by semantic features of the domains and pragmatic context. As such, while the modified scale from Croft et al. is employed to better illustrate intra-linguistic variation, the hierarchical relationship within the scale is not directly applied to the data analysis. The paper discusses the construction types independently rather than in clusters.

There are issues that require further research. Most previous studies on the lexicalization of metaphorical motion have focused on crosslinguistic comparisons, with fewer examining intra-linguistic variation, as this study does. Future research could explore such differences in other languages. Caballero and Ibarretxe-Antuñano’s (2015) cross-genre study has found that while English and Spanish differ in expressing physical motion, their differences are less dramatic in metaphorical motion. This suggests that even in S- or V-languages, the lexicalization of metaphorical motion may vary by genre. Additionally, this study discusses construction types independently. Future research could investigate metaphorical motion encoding concerning the scale in clusters for a more comprehensive understanding. Finally, future studies might explore metaphorical caused motion to validate the findings on a broader scale.

Funding source: Guangdong Province Philosophy and Social Sciences Project

Award Identifier / Grant number: GD24YWY04

Funding source: Humanities and Social Sciences Foundation of the Ministry of Education of China

Award Identifier / Grant number: 23YJC740003

Funding source: Guangdong Province General Universities Special Innovation Project

Award Identifier / Grant number: 2024WTSCX121

Funding source: Hunan Province Philosophy and Social Sciences Project

Award Identifier / Grant number: 24YBQ095

Acknowledgments

I am deeply grateful to Prof. Yu Deng and Dr. Changqing Zheng for their invaluable guidance in revising the manuscript. My sincere thanks also go to the anonymous reviewers, Dr. Jenny Audring, the Area Editor, and all other editors involved, whose feedback greatly improved the paper. Finally, I appreciate Marie-Christine Benen and Kumaran Rengaswamy for their helpful responses regarding the review process.

-

Research funding: This work was supported by research grants from the Guangdong Province Philosophy and Social Sciences Project (No. GD24YWY04), the Humanities and Social Sciences Foundation of the Ministry of Education of China (No. 23YJC740003), the Guangdong Province General Universities Special Innovation Project (No. 2024WTSCX121), and the Hunan Province Philosophy and Social Sciences Project (No. 24YBQ095).

References

Allen, Shanley, Asli Özyürek, Sotaro Kita, Amanda Brown, Reyhan Furman, Tomoko Ishizuka & Mihoko Fujii. 2007. Language-specific and universal influences in children’s syntactic packaging of manner and path: A comparison of English, Japanese and Turkish. Cognition 102(1). 16–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2005.12.006.Search in Google Scholar

Aske, Jon. 1989. Path predicates in English and Spanish: A closer look. Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society 15(1). 1–14. https://doi.org/10.3765/bls.v15i0.1753.Search in Google Scholar

Beavers, John, Levin Beth & Shiao Wei Tham. 2010. The typology of motion expressions revisited. Journal of Linguistics 46(3). 331–377. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0022226709990272.Search in Google Scholar

Berman, Ruth & Dan Slobin. 1994. Relating events in narrative: A crosslinguistic developmental study. New York: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.Search in Google Scholar

Caballero, Rosario. 2007. Manner-of-motion verbs in wine description. Journal of Pragmatics 39(12). 2095–2114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2007.07.005.Search in Google Scholar

Caballero, Rosario. 2017. Metaphorical motion constructions across specialized genres. In Iraide Ibarretxe-Antuñano (ed.), Motion and space across languages, 229–256. Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins.10.1075/hcp.59.10cabSearch in Google Scholar

Caballero, Rosario & Iraide Ibarretxe-Antuñano. 2015. From physical to metaphorical motion: A cross-genre approach. In Vito Pirrelli, Claudia Marzi & Marcello Ferro (eds.), NetWordS 2015: Word knowledge and word usage: Representations and processes in the mental lexicon, 155–157. Pisa: Scuola Normale Superiore.Search in Google Scholar

Chen, Liang & Jiansheng Guo. 2009. Motion events in Chinese novels: Evidence for an equipollently-framed language. Journal of Pragmatics 41(9). 1749–1766. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2008.10.015.Search in Google Scholar

Chen, Shujun & Lihuan Wu. 2023. Variable motion encoding within Chinese: A usage-based perspective. Language and Cognition 15(3). 480–502. https://doi.org/10.1017/langcog.2023.12.Search in Google Scholar

Chu, Chengzhi. 2004. Event conceptualization and grammatical realization: The case of motion in Mandarin Chinese. Hawaii: University of Hawaii PhD thesis.Search in Google Scholar

Cifuentes-Férez, Paula. 2014. A closer look at paths of visions, manner of vision and their translation from English into Spanish. Languages in Contrast 14(2). 214–250. https://doi.org/10.1075/lic.14.2.03cif.Search in Google Scholar

Croft, William, Jóhanna Barðdal, Willem Hollmann, Violeta Sotirova & Chiaki Taoka. 2010. Revisiting Talmy’s typological classification of complex event constructions. In Hans Boas (eds.), Contrastive studies in construction grammar, 201–236. Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins.10.1075/cal.10.09croSearch in Google Scholar

Dong, Danian. 2007. Xiandai hanyu fenlei da cidian [Dictionary of classification of modern Chinese]. Shanghai: Shanghai Lexicographical Publishing House.Search in Google Scholar

Feist, Michele & Sarah Duffy. 2020. On the path of time: Temporal motion in typological perspective. Language and Cognition 12(3). 444–467. https://doi.org/10.1017/langcog.2020.7.Search in Google Scholar

Filipović, Luna. 2007. Talking about motion: A crosslinguistic investigation of lexicalization patterns. Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins.10.1075/slcs.91Search in Google Scholar

Goschler, Juliana & Anatol Stefanowitsch. 2013. Variation and change in the encoding of motion events. Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins.10.1075/hcp.41Search in Google Scholar

Guo, Dafang. 1994. Xiandai hanyu dongci fenlei cidian [Dictionary of classification of modern Chinese verbs]. Changchun: Jilin Education Press.Search in Google Scholar

Hendriks, Henriette & Maya Hickmann. 2015. Finding one’s path into another language: On the expression of boundary crossing by English learners of French. The Modern Language Journal 99. 14–31. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.2015.12176.x.Search in Google Scholar

Kashyap, Abhishek & Christian Matthiessen. 2019. The representation of motion in discourse: Variation across registers. Language Sciences 72. 71–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.langsci.2018.06.011.Search in Google Scholar

Katis, Demetra & Stathis Selimis. 2005. The development of metaphoric motion: Evidence from Greek children’s narratives. Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society 31(1). 205–216. https://doi.org/10.3765/bls.v31i1.899.Search in Google Scholar

Lakoff, George & Mark Johnson. 1980. Metaphors we live by. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.Search in Google Scholar

Lewandowski, Wojciech. 2021. Variable motion event encoding within languages and language types: A usage-based perspective. Language and Cognition 13(1). 34–65. https://doi.org/10.1017/langcog.2020.25.Search in Google Scholar

Lewandowski, Wojciech & Jaume Mateu. 2020. Motion events again: Delimiting constructional patterns. Lingua 247. 102956.10.1016/j.lingua.2020.102956Search in Google Scholar

Lewandowski, Wojciech & Şeyda Özçalışkan. 2023. Running across the mind or across the park: Does speech about physical and metaphorical motion go hand in hand? Cognitive Linguistics 34(3–4). 411–444. https://doi.org/10.1515/cog-2022-0077.Search in Google Scholar

Lin, Jingxia. 2019. Encoding motion events in Mandarin Chinese: A cognitive functional study. Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins.10.1075/scld.11Search in Google Scholar

Matsumoto, Yo. 1996. Subjective motion and English and Japanese verbs. Cognitive Linguistics 7(2). 183–226. https://doi.org/10.1515/cogl.1996.7.2.183.Search in Google Scholar

McEnery, Tony & Richard Xiao. 2003. Lancaster corpus of Mandarin Chinese. European Language Resources Association (Catalogue no. W0039) and the Oxford Text Archive (Catalogue no. 2474).Search in Google Scholar

Naigles, Letitia, Ann Eisenberg, Edward Kako, Melissa Highter & Nancy McGraw. 1998. Speaking of motion: Verb use in English and Spanish. Language and Cognitive Processes 13. 521–549. https://doi.org/10.1080/016909698386429.Search in Google Scholar

Narasimhan, Bhuvana. 2003. Motion events and the lexicon: A case study of Hindi. Lingua 113. 123–160.10.1016/S0024-3841(02)00068-2Search in Google Scholar

Özçalışkan, Şeyda. 2003. Metaphorical motion in crosslinguistic perspective: A comparison of English and Turkish. Metaphor and Symbol 18(3). 189–228.10.1207/S15327868MS1803_05Search in Google Scholar

Özçalışkan, Şeyda. 2004. Typological variation in encoding the manner, path, and ground components of a metaphorical motion event. Annual Review of Cognitive Linguistics 21. 73–102.10.1075/arcl.2.03ozcSearch in Google Scholar

Özçalışkan, Şeyda. 2005. Metaphor meets typology: Ways of moving metaphorically in English and Turkish. Cognitive Linguistics 16(1). 297–298.10.1515/cogl.2005.16.1.207Search in Google Scholar

Özçalışkan, Şeyda. 2015. Ways of crossing a spatial boundary in typologically distinct languages. Applied Psycho Linguistics 36. 485–508. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0142716413000325.Search in Google Scholar

Pedersen, Johan. 2019. Verb-based vs. schema-based constructions and their variability: On the Spanish transitive directed-motion construction in a contrastive perspective. Linguistics 57(3). 473–530. https://doi.org/10.1515/ling-2019-0007.Search in Google Scholar

Pragglejaz, Group. 2007. Mip: A method for identifying metaphorically used words in discourse. Metaphor and Symbol 22(1). 1–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/10926480709336752.Search in Google Scholar

Rohde, Ada Ragna. 2001. Analyzing path: The interplay of verbs, prepositions, and constructional semantics. Houston: Rice University PhD thesis.Search in Google Scholar

Rojo, Ana & Javier Valenzuela. 2003. Fictive motion in English and Spanish. International Journal of English Studies 3(2). 123–149.Search in Google Scholar

Semino, Elena, Alice Deignan & Jeannette Littlemore. 2013. Metaphor, genre, and recontextualization. Metaphor and Symbol 28(1). 41–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/10926488.2013.742842.Search in Google Scholar

Shan, Xinxin & Aunga Onchoke. 2018. Metaphorical motion in Chinese. Cognitive Linguistic Studies 5. 230–260. https://doi.org/10.1075/cogls.00020.sha.Search in Google Scholar

Shi, Wenlei & Yicheng Wu. 2014. Which way to move: The evolution of motion expressions in Chinese. Linguistics 52(5). 1237–1292. https://doi.org/10.1515/ling-2014-0024.Search in Google Scholar

Slobin, Dan. 2004. The many ways to search for a frog: Linguistic typology and the expression of motion events. In Ludo Verhoeven & Sven Strömqvist (eds.), Relating events in narrative: Typological and contextual perspectives, 219–257. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.Search in Google Scholar

Slobin, Dan. 2006. What makes manner of motion salient? In Maya Hickmann & Stéphane Robert (eds.), Space in languages: Linguistic Systems and cognitive categories, 59–81. Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins.10.1075/tsl.66.05sloSearch in Google Scholar

Slobin, Dan & Nini Hoiting. 1994. Reference to movement in spoken and signed languages: Typological considerations. Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistic Society 20(1). 487–505. https://doi.org/10.3765/bls.v20i1.1466.Search in Google Scholar

Talmy, Leonard. 2000. Toward a cognitive semantics II. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.10.7551/mitpress/6847.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Talmy, Leonard. 2009. Main verb properties and equipollent framing. In Jiansheng Guo, Elena Lieven, Nancy Budwig, Susan Ervin-Tripp, Keiko Nakamura & Şeyda Özçalışkan (eds.), Crosslinguistic approaches to the psychology of language: Research in the tradition of Dan Isaac Slobin, 389–402. New York: Psychology Press.Search in Google Scholar

Torres-Martínez, Sergio. 2022. Metaphors are embodied otherwise they would not be metaphors. Linguistics Vanguard 8(1). 185–196. https://doi.org/10.1515/lingvan-2019-0083.Search in Google Scholar

Wilson, Nicole. 2005. Conceptualizing motion events and metaphorical motion: Evidence from Spanish/English bilinguals. Santa Cruz: University of California PhD thesis.Search in Google Scholar

Zlatev, Jordan, Blomberg Johan & Ulf Magnusson. 2012. Metaphor and subjective experience: A study of motion-emotion metaphors in English, Swedish, Bulgarian, and Thai. In Ad Foolen, Ulrike Lüdtke, Timothy Racine & Jordan Zlatev (eds.), Moving ourselves, moving others, 423–450. Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins.10.1075/ceb.6.17zlaSearch in Google Scholar

Zlatev, Jordan & Peerapat Yangklang. 2004. A third way to travel: The place of Thai in motion event typology. In Sven Strömqvist & Ludo Verhoeven (eds.), Relating events in narrative: Typological and contextual perspectives, 159–190. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.