Abstract

Words that speakers and dictionaries deem to be morphologically defective (and thus unacceptable) are often found in corpora, suggesting a disconnect between judgements about such words and usage of them. This paper explores the hypothesis that social and contextual factors may help explain why defective words are often attested despite speakers’ intuitions that they should not be. We carry out a study on French, proposing that some verbs conventionally analysed as defective in this language are not so much examples of ineffable ungrammaticality as they are examples of social stigmatisation. We perform an acceptability judgement task which finds that the acceptability of defective words is inversely correlated with the extent to which participants orient to prescriptivist discourses circulating in French society, and depends also on the emphasis that the task places on taking a prescriptive attitude to language. The hypothesis that speakers’ metalinguistic awareness is key to accounting for speakers’ felt sense of defectiveness is further substantiated by the fact that acceptability of defective items is inversely proportional to the frequency of their lexeme, suggesting that the amount of evidence speakers have about a lexeme plays an important role in how acceptable the item is perceived to be.

1 Introduction

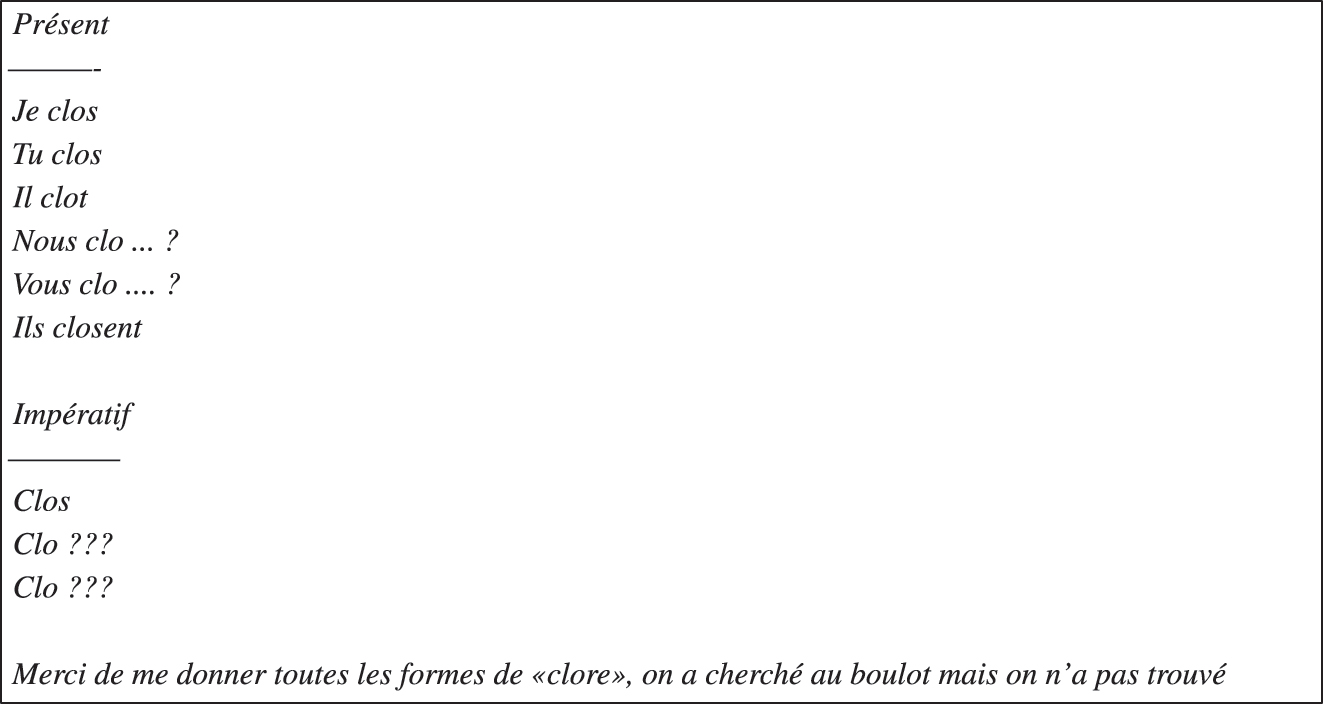

A lexeme’s inflectional paradigm is defective when there is no wordform that speakers will accept as the realisation of one or more of its cells (Sims 2015). Each resulting empty cell is a paradigm gap. A well-known example of a defective lexeme in French is the verb clore ‘to close’, shown in Table 1. This verb is frequently cited as being defective in its 1pl present indicative, 2pl present indicative, and in the imperfect, simple past, subjunctive imperfect, and imperative plural (e.g., Morin 1987, 1995). Moreover, anecdotally, at least some speakers are clearly aware that this verb is problematic. For instance, in a Google Groups discussion, a person posted the following question about the forms of clore:

The conjugation of finite non-periphrastic forms of the defective verb clore ‘to close’. Dashed cells are deemed defective.

| Indicative | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Present | Imperfect | Simple past | Simple future |

| je clos | – | – | je clorai |

| tu clos | – | – | tu cloras |

| il clôt | – | – | il clora |

| – | – | – | nous clorons |

| – | – | – | vous clorez |

| ils closent | – | – | ils cloront |

|

|

|||

| Subjunctive | Conditional | Imperative | |

|

|

|||

| Present | Imperfect | Present | Present |

|

|

|||

| que je close | – | je clorais | |

| que tu closes | – | tu clorais | clos |

| qu’il close | – | il clorait | |

| que nous closions | – | nous clorions | – |

| que vous closiez | – | vous cloriez | – |

| qu’ils closent | – | ils cloraient | |

The poster asks for the 1pl present indicative, 2pl present indicative and imperative forms of clore, saying that they and their coworkers have spent time discussing what these forms would be, to no avail. Additionally, consider the following Twitter exchange:

In this exchange A (an account specialising in tweets about French grammar) condemns the practice of using clôturer ‘to surround with a fence’ instead of clore, which owes its origins to speakers’ desire to fill in the cells of the latter verb: “Avoid the verb ‘clôturer’ with the meaning of ‘to end’. Use ‘clore’ instead” – to which user B replies: “The verb clore is defective. Its conjugation is incomplete. It is better to use ‘clôturer’ instead”. Examples of this sort, which are not hard to find, show that at least some speakers seem to have metalinguistic awareness of French verbal defectiveness. The question we ask is: What is the source of this “felt sense” of defectiveness?

Previous studies have analysed paradigm gaps (in French and other languages) as cases of ineffable ungrammaticality. While differing in the details, all of these analyses make an implicit or explicit claim that speakers reject potential “gap-filling” forms either because there is no sufficiently well-formed output of the grammar (Albright 2003; Orgun and Sprouse 1999), or because potentially well-formed outputs are blocked by an entrenched generalisation about the existence of defectiveness (Halle 1973; Sims 2015). In either scenario, affected paradigm cells are left empty and are thus unavailable for use. Speakers’ felt sense of defectiveness is posited to derive from this failure of the grammar to license a form.

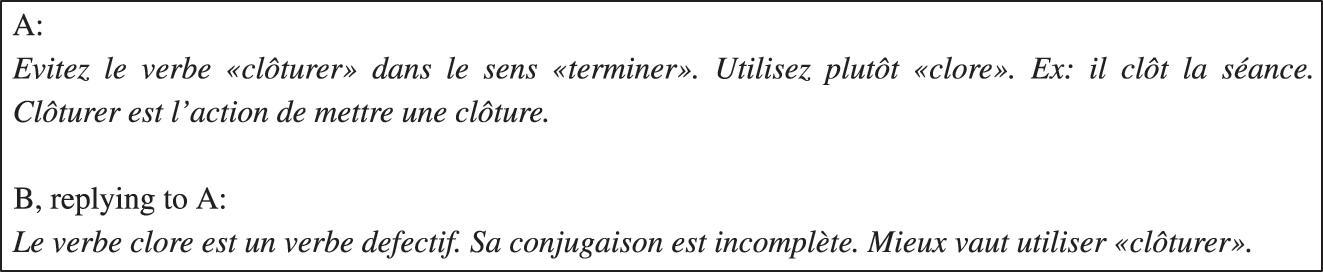

While it is clear that for the French verbal gaps there are grammar-internal motivating factors (discussed in Section 3.2), there are also indications that there is more to the story of French defectiveness than ineffable ungrammaticality. For instance, it is difficult to square grammar books’ and dictionaries’ claims about French verbal gaps – and speakers’ metalinguistic awareness of them – with observations of language use. If French verbal gaps are examples of ineffable ungrammaticality, we expect to be able to detect this in patterns of usage: paradigm cells with gaps should be unattested in large-scale corpora – or at least, underattested (Sims 2015: 52–55). Yet detecting gaps in corpora has proven difficult in French (Copot and Bonami 2020) and other languages (Brown and Evans 2022; Nikolaev and Bermel 2023).[1] Figure 1 shows data from Copot and Bonami (2020) comparing the frequency properties in the French portion of Corpora from the Web (FrCoW; Schäfer 2015) of words that have been claimed to be defective by at least two dictionaries (e.g., in the ipfv.3sg, clore, discontinuer ‘cease’, frire ‘fry’, amongst others) to those of other verbs in the same cell.[2] One might expect gap-filling wordforms to be underattested. Contrary to this expectation, Figure 1 shows that the frequency of occurrence of gap-filling forms in imperfect third singular does not differ significantly from the frequency of imperfect third singular forms in general, when controlling for lexeme frequency.

Words belonging to the French ipfv.3sg cell, plotted by their lexeme and token frequency (Copot and Bonami 2020). Points highlighted in yellow are words that have been claimed to be defective.

This suggests that at least in French, there is a discrepancy between what grammar books/dictionaries claim and speakers’ metalinguistic awareness of defectiveness on the one hand, and speakers’ linguistic behaviour with regard to defective verbs on the other. What is the source of this discrepancy? If speakers’ felt sense of defectiveness derives from ineffable ungrammaticality, why is it not possible to detect this ungrammaticality in patterns of usage?

In this paper we pursue the hypothesis that the French verbal gaps are not so much examples of ineffable ungrammaticality as they are examples of grammatical taboos. More specifically, we are interested in the possible role of prescriptivism in shaping speakers’ felt sense of defectiveness. We follow Curzan (2014: 5) in defining prescriptivism as those practices of language regulation within a society that are created, maintained, and enforced by institutionalised and culturally sanctioned language authorities, and then reproduced and perpetuated at the individual level by speakers who ideologically align themselves with these language authorities. We thus view prescriptivism as a particular kind of sociolinguistic practice involved in regulation of language norms (Cameron 1995); the term is used here to restrict our focus to the subset of those practices that are specifically elitist in orientation, authority-based, institution-based, and often conservative in nature. They interest us in particular because France is known for its strongly standardising language culture. Standardising prescriptivism is able to produce a discrepancy between observable language use and speaker beliefs about and evaluative reactions to their language, via stigmatisation.[3] We examine whether those speakers that have a felt sense of defectiveness are anchoring this feeling, in part, in a belief that verb forms that would fill gaps are not properly part of French.

To test the hypothesis, we constructed judgement tasks comparing defective forms to both slang words and to ungrammatical forms. We expected defectiveness to pattern with slang, particularly in being judged as less acceptable when French speakers were asked to judge items normatively (Would a teacher mark the use of the word as wrong?) than when asked to make a possibility judgement (Could you imagine hearing this word in a conversation?). To preview the results, defectiveness only partly patterned with slang, with differences likely reflecting register differences across the two types of items. Nonetheless, effects by the type of judgement task and by participants’ strength of orientation to prescriptivist discourses, along with an effect of word frequency in which high-frequency words of the defective type were rated as more problematic, support the hypothesis that prescriptivism plays a role in delineating the class of items that have been deemed defective. The results ultimately suggest a story in which speakers’ metacognitive awareness of prescriptive norms affects the grammatical system. We conclude that taking speakers’ own metacognition about their language into account can offer important insight into defectiveness as a morphological phenomenon.

2 Linguistic effects of prescriptivism

While a few studies have linked prescriptivism to the diachronic development of defectiveness (Baerman 2008, 2011; Broadbent 2009; Gilliéron 1919), we are not aware of any that investigate the role of prescriptivism in how speakers judge defective forms. Moreover, the importance of prescriptivist beliefs to linguistic investigation is not always assumed. In this section we therefore begin with some discussion of what it means to take prescriptivism as an object of investigation and its hypothesised relationship to defectiveness.

2.1 Prescriptivism as an object of investigation

We approach speakers’ prescriptivist beliefs as a sociolinguistic factor whose relationship to defectiveness can be examined through hypothesis formation and testing. The idea to examine how prescriptivism affects linguistic behaviour is not new. For example, see the work of Cameron (1995) and Curzan (2014), who examine prescriptivism’s effects through the lenses of sociolinguistics and language change, respectively. Yet it requires us to step away from the prescriptive-descriptive binarism that is deeply embedded in linguistics as a field. We therefore begin with the question: why should linguists be interested in prescriptivism?

In the binary opposition that linguists draw between descriptivism and prescriptivism (for instance, when teaching introductory linguistics courses), descriptivism represents objective, empirical and scientific investigation of language, while prescriptivism represents beliefs about language that are subjective, misguided, and even prejudicial. Accordingly, linguists have a tendency to view prescriptivist beliefs as irrelevant to linguistic theory in the same way that beliefs about the laws of nature (e.g., that the earth is flat) are irrelevant to the actual laws of nature.

At the same time, it has been observed (Cameron 1995; Curzan 2014; Hinrichs et al. 2015; Vogel 2018, 2019; Woolard and Schieffelin 1994) that positioning prescriptivism as irrelevant to linguistic study is paradoxical to the extent that prescriptivism is also often viewed as a force that distorts patterns of language use and interferes with language change. Cameron (1995: 3) notes that the “leave your language alone” ethos that is widespread in linguistics is on the one hand a reaction against prescriptivism, but on the other also revealing of a belief that prescriptivism interferes with language, or at least has the potential to do so.[4] After all, why would speakers need to be exhorted to leave their language alone if prescriptivist beliefs were truly irrelevant to language use?

While prescriptivist discourses can observably affect language use, even at the level of the individual (Malory 2024), on the timescales involved in language change the effect often amounts to a “small, temporary and delaying influence” (Anderwald 2020: 78).[5] This makes it possible to view prescriptivism as interfering with inexorable language change in the short run, but as irrelevant in the long run. Additionally, effects of prescriptivism are most easily observed in formal written language (Hinrichs et al. 2015).[6] Linguists, however, generally take spoken (or signed) language as primary, so prescriptivism effects may be seen as artificially imposed and as not affecting the “real” language (Curzan 2014: 50).

The paradoxical view of prescriptivism as irrelevant but at the same time pernicious is thus ameliorated, at least in part, by defining linguistic effects of prescriptivism as temporary, artificial, and imposed on the “real” language. This has allowed the field of linguistics to continue to (implicitly or explicitly) take the position that prescriptivism is uninteresting to the scientific study of language. Yet this position is of doubtful value.

We should beware of […the idea] that changes in the language caused by prescriptive impulses are not somehow ‘real’ language change, internal or external: it falls into the binary of suggesting that some changes are ‘natural’ to language and others are unnaturally imposed. The natural-unnatural binary can prove unhelpful in thinking about the relationship of prescriptivism and language history. (Curzan 2014: 10)

Moreover, as Cameron (1995) emphasises, viewing prescriptivism as a factor in societal regulation of linguistic norms makes it equally as normal as any other kind of sociolinguistic factor: “If ‘natural’ here means something like ‘observed to occur in all speech communities to a greater or lesser extent’, then the kind of norm-making and tinkering linguists label ‘prescriptive’ is ‘natural’ too” (Cameron 1995: 5).

One advantage of viewing prescriptivism as a sociolinguistic factor – in principle like any other – is that it facilitates questions about the roles of authority and agency in linguistic behaviour (Cameron 1995). We are interested in prescriptivist discourses as socially rooted phenomena that have the potential to shape linguistic behaviour and grammatical patterns. Failing to consider whether prescriptivism (or other aspects of speakers’ metalinguistic knowledge) affects speakers’ linguistic behaviour risks misanalysing or incompletely analysing grammatical phenomena. The defectiveness literature, like linguistic research in general, overrepresents standardised languages spoken in Western, Educated, Industrialised, Rich and Democratic (WEIRD) societies (Henrich et al. 2010), which often have strongly standardising language traditions. In such languages, it seems reasonable to hypothesise that speakers’ knowledge of morphological defectiveness is shaped by their awareness of normative societal language ideologies, as well as their own individual alignment with those ideologies, the latter of which can be viewed as an issue of agency. Investigating prescriptivism as a factor in linguistic behaviour allows us to ask questions about whether processes of linguistic regulation that are elitist in orientation, authority-based, institution-based, and often conservative may also play a role in causing and/or maintaining defectiveness.

2.2 Types of prescriptivism and prescriptivism as a historical cause of gaps

Curzan (2014: 12–40) identifies four types of prescriptivism: standardising prescriptivism, stylistic prescriptivism, restorative prescriptivism, and politically responsive prescriptivism. We set aside politically responsive prescriptivism, which has to do with promoting “inclusive, nondiscriminatory, politically correct, and/or politically expedient usage” (p. 24), since we are not aware of it having been linked to morphological defectiveness.

Standardising prescriptivism involves rules or admonitions that seek to promote one form or construction as the only legitimate one from among competing ways of saying the same thing. It thus defines the boundaries of the standard language, with forms that fall outside of the standard being labelled as “wrong” and subject to stigmatisation. As Curzan points out, the standard language tends also to be ideologically conflated with the language as a whole. In other words, forms that are defined as falling outside of the standard are also often conceptualised as falling outside of the language.

Stylistic prescriptivism involves rules or admonitions that focus on points of style within standard language use. It is aesthetically oriented, focused on language use that is perceived to be pleasing or appropriate, with constructions that fall short often being labelled as “ugly”. Stylistic prescriptivism may focus on register, such as the desired properties of formal written style, and it tends to define what counts as “good” or “beautiful” language in terms of formal, written norms.

Finally, restorative prescriptivism involves rules or admonitions that seek to restore earlier forms and constructions that have become obsolete. It is thus conservative in nature. Restorative prescriptivism is often motivated by an ideological stance that equates older forms of the language with more “pure” states of the language.

These three types of prescriptivism are not mutually exclusive and practices of language regulation and standardisation often invoke more than one kind of prescriptivism simultaneously.

While previous research connecting prescriptivism to defectiveness is scant, a few studies invoke prescriptivism as a partial historical cause of defectiveness. Baerman (2008) argues that language standardisation processes in Russian underpinned the development of 1sg gaps in verbs by creating a stylistic clash between borrowings with Church Slavonic roots and a native Russian morphophonological alternation that became the normative standard. This can be interpreted as assigning a causative role to both standardising prescriptivism and stylistic prescriptivism. Broadbent (2009) also cites prescriptivism rooted in a desire to avoid homophony of aren’t and amn’t in West Yorkshire as a cause of the *amn’t gap in English. Perhaps most interestingly in the present context, Gilliéron (1919) argues that the French verb clore ‘close’ introduced in Section 1 had been lexically lost from French by the sixteenth century, with only the past participle form clos continuing in adjectival use. The Académie française later resuscitated the verb – but only those forms that were predictable from the past participle (see also Baerman 2011 for discussion). This assigns a crucial role to restorative prescriptivism in causing the defectiveness of clore, since it is the resuscitation of the verb that brought some – but not all – of the forms back into use. These studies suggest that the idea that different kinds of prescriptivism can play a role in speakers’ felt sense of defectiveness may be on the right track.

2.3 Hypothesised relationship to defectiveness

In broad terms, our hypothesis is that prescriptive practices – particularly, standardising ones – at least in some cases lead speakers to form negative judgements of forms marked by prescriptive authorities as defective. The narrative behind this hypothesis is as follows.

In a standardising culture that seeks to reduce linguistic variation and which reinforces the message that there is only one “right” way to say something, the simple feeling that there must be a single right form may cause speakers to be uncomfortable with situations in which they are uncertain about what the “right” inflected form of a lexeme is, leading them to avoid using any possible form out of fear of choosing the “wrong” one. In other words, avoidance may arise from a kind of risk aversion. Additionally, dictionaries and grammar books may note such cases and codify them as explicit linguistic knowledge (e.g., “the form for cell X in lexeme Y is problematic”). Such statements may be prescriptive in orientation or may simply be intended as descriptions of grammatical structure or language use. However, in standardising prescriptive cultures, speakers tend to view even descriptive dictionaries and grammars as prescriptive authorities (Curzan 2014: 104). This may also serve to steer speakers away from using any form at all.

At the same time, this tendency to treat dictionaries and grammars as prescriptive authorities means that speakers’ metalinguistic knowledge of defectiveness does not inherently depend on speakers facing uncertainty over the morphological form of some word. For instance, the conservative ideologies underpinning restorative prescriptivism have no inherent relationship to uncertainty about the form of a word. Prescriptivism should thus be able to act on speakers’ metalinguistic knowledge of defectiveness if the lexeme is the target of prescriptive forces, whatever the reason for this.

Importantly, under this hypothesis prescriptivism is expected to lead individual speakers to differ in whether they deem a given lexeme to be defective, depending on the strength of their orientation towards the ideologies underpinning their society’s prescriptive language practices. It is also expected to produce lexeme-level differences, reflecting how strongly a word is targeted by prescriptivist discourses and speakers’ awareness of these. We assume that more frequent lexemes are more likely to be recorded in grammars and dictionaries as defective – for instance, because they are more likely to be noticed as having a problematic form. We thus expect lexeme-level effects of prescriptivism to show up disproportionately in high-frequency words.

This prediction is notable because it runs opposite to what has been claimed in previous work. Most notably, Albright (2003, 2009) argues that defectiveness should be more likely for low frequency lexemes. He models defectiveness as jointly determined by indeterminacy within the grammar about the application of morphological patterns and by the amount that is known about a target word. For example, in Spanish some verbs have a morphophonological stem alternation (e.g., c[o]ntar ‘count.inf’ – c[we]nto ‘1sg’) and others do not (e.g., c[o]mer ‘eat.inf’ – c[o]mo ‘1sg’). The fewer opportunities speakers have to observe the inflected form that realises some paradigm cell, the more likely they are to need to generate it based on inflectional rules, rather than recalling it from memory. However, in some classes alternation is highly variable and/or there are few words with the relevant phonological shape (e.g., there are few class 3 verbs with a root vowel /o/), resulting in no highly reliable rule. Albright argues that defectiveness arises in situations in which a form cannot be recalled and needs to be generated, but there is insufficient information about whether the target verb should alternate. Since low frequency lexemes are less likely to have robust memory representations and are thus most likely to need to be generated by rule, they are expected to be more susceptible to defectiveness, compared to higher frequency lexemes. Albright (2003) does not actually report whether Spanish verbs conventionally identified as defective tend to be of low frequency,[7] but Sims (2015: 155) finds that in Modern Greek, nouns listed in dictionaries as defective and connected to an indeterminate alternation are disproportionately of low frequency. We return to discussion of the relationship between word frequency and defectiveness in Sections 5 and 7.

3 Prescriptivism and defectiveness in French

With this background we now turn to the specific case study of French that forms the core of this paper. The French language provides fertile ground to test whether paradigmatic gaps bear a connection to prescriptivism.

3.1 Prescriptivism in the French language

Language planning and policy is the ensemble of actions taken by persons or organisations in positions of authority to influence the structure and function of the language(s) spoken by a given population. France has a strong tradition of prescriptive language planning, dating back to the fourteenth century (Stengel 1976; Swiggers 1984). Language planning and policy relating to the French language has been very conservative, with calls for protecting the language from foreign borrowings and for standardising correct usage. Of particular interest for our research is the rejection of variation: authorities on the French language rarely acknowledge the existence of multiple linguistic means for expressing the same thing, instead preferring to artificially partition variation by assigning lexical variants different connotations along some axis (in a way that is often neither consistent between authorities nor an apt description of the variants’ distribution by speaker) or by selecting one variant as more correct than others (Poplack and Dion 2009; Poplack et al. 2015).

Due to the important place that language planning and policy occupies in French culture, speakers of French have long shown considerable metalinguistic awareness of anti-variationist ideologies, as documented in the work of Ayres-Bennett (1994, 2006) on the remarqueurs, a tradition of writers who would remark upon points of doubtful usage of the French language. The tradition of the remarqueurs has evolved in more modern times into chroniques de langage, the practice of having regular columns about language use in major newspapers (Osthus 2015).

The tradition of prescriptivism permeating the French language has also been consolidated into an institution: the clearest symbol of prescriptive attitudes in French language planning and policy is the Académie française. The Académie was founded in 1635 with the stated purpose of defining rules for the French language, so that the language may be made “pure, eloquent, and apt for discussing the arts and the sciences” (article XXIV of the Académie’s statute). Through the lens of the framework in Section 2.2, this is a call for stylistic prescriptivism (eloquent, apt for discussing the arts and sciences), as well as for standardising and restorative prescriptivism (pure).

The combination of the prestige of organisations like the Académie and the historical interest in metalinguistic discourse make it so that the average French speaker often has awareness of prescriptive rules meant to be followed through language use and sees deviations from them as markers of low status. Of particular interest for our purposes is that Lodge (1991) documents several examples of prescriptivism from speakers of French, and Drackley (2019) argues that speakers of French will go further than institutions in their prescriptive attitude, seeking to counter language reforms perceived to be relaxing grammatical rules.

3.2 Structural properties of defective French verbs

The structural properties of defective French verbs have been documented in Morin (1987), Morin (1995), Boyé (2000), Boyé and Cabredo Hofherr (2010), and Bach and Esher (2015).[8] Here we focus on Boyé and Cabredo Hofherr (2010).

Boyé and Cabredo Hofherr (2010) show that the defectiveness of the set of French verbs is rooted in the morphological organisation of verbal stems. The affected cells do not form a morphosyntactic natural class, so a generalisation about the distribution of gaps within the paradigm cannot be made in morphosyntactic terms. However, the affected cells are all expected to have forms built on the same stem, based on Bonami and Boyé’s (2002) analysis of stem allomorphy. The key generalisation for the defective verbs is thus that if one form is lacking, other forms sharing the same stem are absent too. Boyé and Cabredo Hofherr suggest that this can have different causes: “either speakers do not have a plausible stem for a defective cell (stem indeterminacy) or there are possible stems which are either rejected by speakers for independent reasons (stem conflict) or not used without any discernible synchronic motivation (stem gaps)” (p. 45).

They assign most cells of clore ‘close’, the example introduced at the beginning of the paper, to the stem gap type: existing forms of the verb strongly suggest a particular form to fill most defective cells (e.g., closez for 2pl indicative present), so defectiveness in these cells cannot be directly attributed to some problem with the stem form. They also include frire ‘fry’ in this type (however, they note variation across speakers in whether this verb is defective).

They classify the simple past cells of clore, as well as the defective forms of verbs like braire ‘bray’ and faillir ‘fail to’, as stem indeterminacy gaps, with no sufficiently plausible stem for defective cells. They do not include any French verbs in the stem conflict category, but we consider this type to include verbs like surfaire ‘overdo’ in the indicative present 2pl: the verb is formed by prefixing a highly irregular verb, faire ‘do’. The indicative present 2pl form of the base verb is faites. However, on the basis of implicative relationships within the French verbal system, the more likely indicative present 2pl form for this class of verbs would be faisez.[9] So verbs like surfaire find themselves between two attractors in conjugational space: their irregular base form and the more frequent pattern for their class.

In terms of their structural properties, French verbal gaps are thus simultaneously both uniform and diverse. On the one hand, the gaps are clearly connected to verb stem allomorphy: the distribution of gaps in a defective verb’s paradigm follows the expected distribution of its stem allomorphs. On the other hand, they do not have a uniform structural cause, with some verbs lacking any clear analogical model or being pulled between two models, but with others having one clearly expected stem form. This latter group, in particular, leads Boyé and Cabredo Hofherr (2010) to conclude that (at least some) paradigm gaps are lexicalised.

Sims (2023) observes that this scenario, in which defective lexemes have structural properties in common without those properties by themselves offering sufficient causal explanation, arises in many cases of defectiveness. It suggests that structural factors play a role in many cases of defectiveness but also may often be only part of the full causal story. We hypothesise that at least in French, an additional factor is prescriptivism, or more accurately, speakers’ alignment to prescriptivist ideologies.

Before moving on to our experimental study, it is important to note that while we have discussed the French verbal gaps as if they are a clearly defined class of items, in fact dictionaries disagree about which lexemes are defective and in which cells. A core group of verbs is marked as defective by most dictionaries (e.g., falloir ‘to have to’ and quérir ‘to seek’), while others are marked as defective in only a handful (e.g., braire ‘to bray’ is defective for Le Robert[10] but not for Larousse[11]). In addition, dictionaries do not necessarily agree on which forms are illicit: occire ‘to kill’ is marked as defective for its present, imperfect and simple past indicative in both Le Robert[12] and Larousse;[13] however, only the former also marks the lexeme as defective in its simple future indicative forms. This variability suggests again that defective items are not easily defined based on purely structural criteria.

4 Methodology

We built an experiment to test the status of French verbs that are conventionally analysed as defective. Are gap-filling forms rejected (at least in part) because of prescriptive pressure, either out of a general fear of using the wrong word (a kind of risk aversion) or because the specific word in question has been explicitly proscribed?

We take our methodological inspiration from Vogel (2019), who uses acceptability ratings as a way to distinguish grammatical but stigmatised constructions from ungrammatical ones. Vogel’s core idea is that since stigmatisation has an ideological basis rather than a purely grammatical one, speakers’ judgements about stigmatised constructions will reflect the Paradox of Grammatical Taboos, given in (1) (Vogel 2019: 48).

| Paradox of Grammatical Taboos |

| A taboo in a language L can only hold over a construction C, if C exists. Thus, C must be part of L’s language system. |

| Because of the taboo over C, speakers of L who conform to the taboo nevertheless believe that C should not and therefore does not belong to L. |

How speakers judge the acceptability of grammatical but stigmatised constructions is expected to depend on whether they rate the construction according to Part A of the Paradox (i.e., according to whether it is used within the community) or according to Part B of the Paradox (i.e., according to whether they believe it to properly belong to the language). Since the two parts of the Paradox represent contradictory understandings of stigmatised constructions, different kinds of questions about a stigmatised construction should elicit different judgements. However, since ungrammatical constructions are unacceptable in general, and fully grammatical, non-stigmatised constructions are acceptable in general, judgements of these should be consistent across different question types.

In his study of German syntactic constructions, Vogel employs three types of questions: one designed to elicit participant judgements about whether a target construction is possible (oriented to Part A of the Paradox), one designed to elicit judgements about whether the construction is normatively correct (oriented to Part B of the Paradox), and one designed to elicit judgements about whether the construction is aesthetically pleasing (“nice”) (also oriented to Part B of the Paradox). We interpret the normative condition as reflecting standardising prescriptivism and the aesthetic condition as reflecting stylistic prescriptivism. Vogel finds greater variability of response for grammatical but stigmatised constructions compared to ungrammatical constructions and compared to grammatical but non-stigmatised constructions, especially in the possibility task condition.[14] We apply a version of Vogel’s methodology to the study of defectiveness in French verbs.

4.1 Tasks

Our experiment featured two task conditions. In both, participants were presented with a sentence containing an underlined word, which they were asked to provide an acceptability judgement for. We sought to manipulate the applicability of the kind of prescriptivist discourse that we suspect contributes to aversion towards defective words (a normative context that stigmatises variability). The two conditions thus targeted different aspects of speakers’ metalinguistic knowledge about the French language.

The normative condition asked participants to provide a normative judgement on the stimuli, asking them to consider rules of thumb such as whether a teacher would mark the use of the word as wrong, or whether they would expect not to find this usage of the word in a book or a dictionary. Along with emphasising the importance of standard, normative usage, this task condition also carried implications about the formality of the context of use, since formal contexts are where the use of language is more prescriptively codified.

The possibility condition attempted to create contexts that would minimise the application of prescriptivist filters on the judgement, by instead shifting focus to everyday informal language use. Participants were asked to rely on their intuitions about language use, such as whether they might be able to hear the usage in question in a conversation between friends at a bar, or between students hanging out after school. This task focused on contexts in which pressure to speak “correctly” according to standard language norms is likely to be less, and certainly less overt.

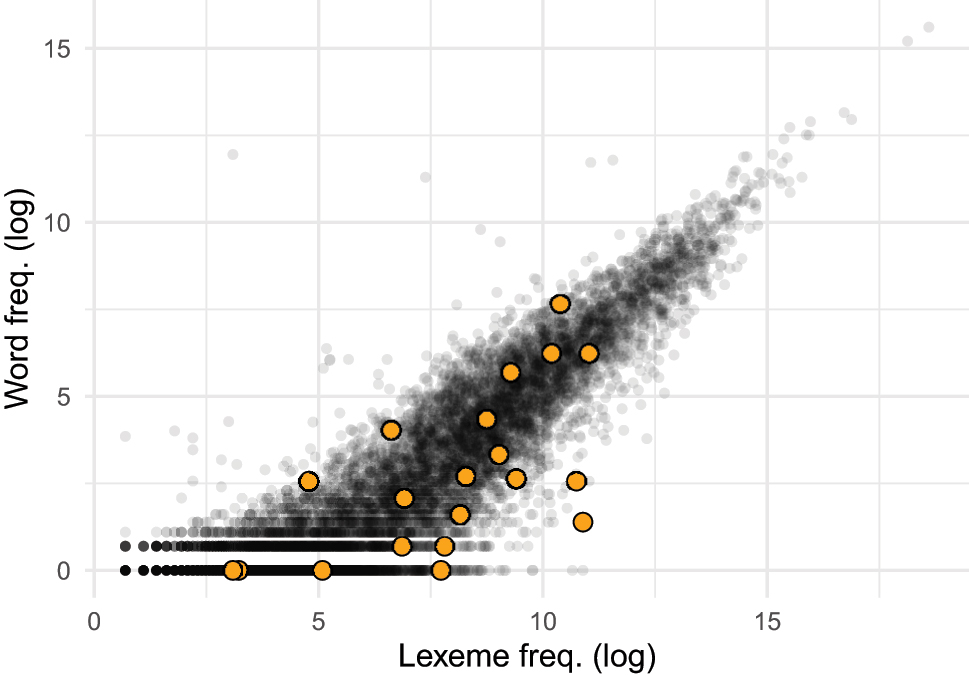

Instructions outlined how the participants should judge the underlined words, by discussing the idea of normativity or possibility explicitly (as relevant to the particular task), as well as by giving heuristics and examples. Figure 2 shows a practice item in each condition. Participants were presented with a continuous scale with labelled extremes. The labels and the prompt changed depending on the task condition.

The same practice item in the two task conditions.

The full task instructions are available in this project’s OSF repository (see the data availability statement at the end of the paper). Each participant saw only one task condition, as described in Section 4.4.

4.2 Items

As noted above, there is a tradition of analysing defectiveness as arising out of unresolvable ungrammaticality. If defectiveness in French verbs is of this sort, perhaps because the grammatical system does not generate sufficiently well-formed candidate forms for the relevant lexemes or because it blocks all candidate forms, defective words should be rated as poorly as words that violate crucial rules or constraints of the linguistic system. If, on the other hand, paradigm gaps are established or corroborated by explicit negative evidence that a word form is prescriptively stigmatised (or by a fear of it being stigmatised), then defective words should pattern with other stigmatised but grammatical forms.

To allow for comparison of defective verbs to unquestionably ungrammatical and to stigmatised forms, the experiment had three item conditions: defective verbs, verbs containing agreement errors, and slang verbs. Verbs with agreement errors (henceforth called ungrammatical items) were controls that provided a reference for how a word is judged when it is blocked or not generated by the grammar.[15] Slang words were controls that provided a reference for items that are used in casual written and spoken French, though proscribed in formal and normative contexts.

Defective words were identified through the verbal portion of Flexique, a large lexical database of French paradigms (Bonami et al. 2014). Flexique marks a word as defective if it is cited as such in at least two major dictionaries of the French language. In total, 1208 wordforms are identified as defective by the source, belonging to 39 lexemes. It is noteworthy that many of the lexemes that dictionaries cite as defective have fallen out of use in the language or are associated with formal registers. These factors were likely to influence the words’ acceptability, so lexemes marked as archaic (14/39) or as used only in formal registers (9/39) were excluded, along with lexemes cited as defective because they are only used in a small subset of forms of their paradigm (18/39). Moreover, a number of defective lexemes in the list are derivationally related (e.g., {traire ‘to milk’, soustraire ‘to subtract’, abstraire ‘to abstract’}, {clore ‘to close’, éclore ‘to hatch’, déclore ‘to uncover’, enclore ‘to enclose’}). We chose to include only one verb per morphological family. In our selection of defective verbs we thus chose to emphasise quality over quantity. This limited the number of defective verbs that were available for use as experimental items.

The defective verbs used for this experiment are given in Table 2.[16] The inflected forms of these verbs that are used in this study are cited as a gap by several dictionaries. These verbs still skew in the direction of being used in more formal registers. For example, clore is not marked as formal by dictionaries, but its flavour of the meaning of ‘to close’ is often found in relation to ceremonies or debates. The semantically similar verb fermer is preferred when talking about closing doors or keeping one’s mouth closed. This distributional association between our items and a higher register happens to be an inescapable fact about the French language. While we tried to minimise this issue with our selection of verbs, there is still a marked register difference between the defective and slang items. In Section 6.1 we consider the importance of this for interpretation of the experiment results.

The defective words chosen for the experiment. The frequencies correspond to the raw frequency of each wordform in FrCoW (Schäfer 2015).

| lexeme | cell | gloss | form | freq |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| braire | ipfv.2sg | bray | brayais | 1 |

| clore | prs.2pl | close | closez | 8 |

| discontinuer | prs.3sg | cease | discontinuea | 3,649 |

| douer | fut.3sg | endow | douera | 49 |

| faillir | prs.2pl | fail to | failliez | 4 |

| frire | prs.2pl | fry | friez | 32 |

| impartir | fut.1pl | assign | impartirons | 1 |

| revaloir | composite_past.2sg | get even with | ai revalu | 4 |

| surfaire | prs.2pl | overdo | surfaites | 200 |

-

aThe high frequency of this form is likely due to its homophony with the feminine form of the adjective discontinu ‘discontinuous’.

French has many sources of slang. We selected words that were described as colloquial in major dictionaries (labelled as “argot”, “slang” or “informal”), and avoided slang words from Verlan (Lefkowitz 1991; Nieser 2005), a language game based on inverting syllables of existing French words that forms the basis of many French colloquialisms.

Ungrammatical items had a subject agreement error in the underlined verb. Speakers of French sometimes neutralise orthographic distinctions between homophonous forms of verbal lexemes (Boivin and Pinsonneault 2018). We made sure that for the agreement error chosen, there was no homophony between the erroneous form and the correct one.

Nine words from each item condition were included in the experiment. This number was dictated by the paucity of suitable defective items. Lexemes in the three item conditions were similarly distributed by frequency, as shown in Table 3. For the sake of interpretability, frequencies are listed in the table as the number of instances of a target word per million tokens of corpus (i.e., as ipm frequency), but frequency matches were selected based on log frequency, since word frequency effects follow a power law distribution.

Lexeme frequency distribution for test items by item condition. Counts are given as the number of instances per million words of corpus, based on the nine-billion-word FrCoW corpus (Schäfer 2015).

| Min | Median | Max | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ungrammatical | 0.003 | 0.244 | 1.56 |

| Defective | 0.011 | 0.48 | 5.304 |

| Slang | 0.048 | 0.23 | 2.252 |

The verbs of interest were presented in minimal sentence frames. We wanted to make sure participants knew they were judging the acceptability of a verb in a particular conjugated form. Agreement errors also require a full sentence.

The list of experiment items is available in Appendix A.

4.3 Participants

Since the number of experiment items was limited by the number of suitable defective verbs, we recruited a large number of participants so that the experiment would have sufficient power to examine participant-level factors.[17] Four hundred participants were recruited on the online experiment platform Prolific.co. Two participants were excluded as the results came from the same IP address, and the results for one participant were not recorded due to a technical issue. A further 20 participants were excluded for not passing the attention check described in Section 4.4. All remaining participants declared being native French speakers who had grown up speaking French as their only language in most day-to-day situations and who currently reside in France. The declared gender of the non-excluded participants was distributed as follows: 193 participants were male, 172 were female, 12 were non-binary. The ages of participants ranged from 18 to 68, with a median of 28. The highest academic qualification held by participants was an elementary school diploma for 2, a high school diploma for 45, a bachelor’s degree for 127 and a master’s degree or higher for 203.

In order to create a score for how prescriptively oriented each participant was, they were asked to indicate the extent of their agreement with nine statements expressing prescriptive ideas that are in circulation in French society, on a 5-point scale. The questions can be found in Appendix A. This survey was designed to have three statements corresponding to each of the three types of prescriptivism – standardising, stylistic, and restorative. The scores for the three types of prescriptivism turned out to be highly correlated, so answers to the questions were summed into a single prescriptivism score for each participant; possible scores ranged from 9 to 45 (actual range: 9–44, median: 28).

4.4 Procedure

The experiment was administered entirely in French. It was deployed on PCIbex (Schwarz and Zehr 2018). Participants were first presented with a consent form. After consenting they responded to the questionnaire designed to gauge the extent of their prescriptive attitudes. They were then randomly assigned to one of the two task conditions. Of the participants included in the analysis, 191 completed the possibility judgement task and 186 completed the normativity judgement task. Participants were then presented with three practice items to familiarise them with the use of the scale. For the central part of the experiment, participants were presented with 27 items (nine from each of the item conditions) in a randomised order.

Following the main task, participants were asked to complete a word familiarity task. They were presented with a list of citation forms (for French verbs, the infinitive) of both the words in the experiment and of pseudoverbs created with Wuggy (Keuleers and Brysbaert 2010). The pseudoverbs matched the phonotactic structure (more technically, the bigram frequency) of the real verbs included in the experiment. Participants were asked to select all words that they knew the meaning of. The inclusion of pseudoverbs had a double purpose: on one hand, pseudoverbs act as fillers so that participants will not be presented only with lexemes they just observed in the experiment, and on the other, they serve to identify unreliable participants. All test items (real verbs) that participants reported not to know were excluded from analysis (4.6 % of total responses).[18] The median familiarity for real verbs in the experiment, as a percentage of participants who reported knowing the word, was 98 %. The three least familiar verbs were douer ‘to gift’ (68 %), impartir ‘to impart’ (75 %) and braire ‘to bray’ (83 %). Average familiarity for defective lexemes was 88 %, 97 % for ungrammatical lexemes, and 99 % for slang.

Twenty participants reported knowing more than 20 % of pseudoverbs. All data from these participants were excluded based on this criterion. The cutoff percentage was chosen based on a visual inspection of the distribution of the percentage of pseudoverbs reported to be known by each participant. A dip in density was observed at around 20 %.

At the end of the experiment, participants were asked for demographic information, they were offered the chance to give feedback on the experiment, and they were then redirected to a debriefing about the goals of the research.

The experiment lasted 10 min on average. Participants were compensated 2.50 euros.

4.5 Predictions

We expected agreement errors to receive scores at floor in both task conditions. Slang was expected to receive higher scores in the possibility condition than in the normativity condition (this would match what Vogel 2019 found for stigmatised syntactic constructions in German). Previous research shows that speakers report lower confidence in their productions when asked to produce words that could fill defective cells (Albright 2003; Pertsova and Kuznetsova 2015; Sims 2006, 2009) and deem such words as relatively less acceptable that non-defective words (Löwenadler 2010; Lukács et al. 2010), from which we can extrapolate that speakers find defective forms somewhat aversive. We expected the aversion inherent to the felt sense of defectiveness would translate to low acceptability scores in our study. However, we did not expect all defective items to be rated uniformly for three reasons.

First, if a felt sense of defectiveness is the result of explicit instructions not to use the forms or of a fear of using the wrong form due to the social stigma attached to linguistic faux pas, more prescriptively oriented participants should rate defective items as worse than less prescriptively oriented participants do. We thus expected by-participant variation that would be predicted by participant prescriptivism scores.

Second, based on the hypothesis that French verbal gaps are stigmatised, we expected defective items to be rated lower in the normative task condition than in the possibility task condition, parallel to slang items. We thus expected by-task variability.

Third, we expected that higher frequency defective items would be rated lower than lower frequency ones because speakers are likely to have more experience with higher frequency verbs, and thus have more evidence for their defective status.

In summary, we expected more by-item variability in this item condition than in the other two, and we expected this variability to be predicted by lexeme frequency. We also expected by-task variability, and for the effects of these factors to be stronger for participants with higher prescriptivism scores.

4.6 Analysis

The analysis was performed in R (R Core Team 2021), with the brms package (Bürkner 2017). A zero-and-one-inflated maximal bayesian beta regression was fitted to the responses. The choice to augment the model with zero-and-one inflation is intended to account for the fact that not all participants utilised the scale as continuous, instead giving either extreme answers only, or a high percentage of extreme answers.

The dependent variable is the raw scores from the judgement task, all values between 0.00 and 1.00.

fixed effects

Task condition: Whether the participant was assigned to the normativity or possibility condition. The factor is deviation-coded (possibility: −0.5, normativity: 0.5).

Item condition: Whether the item is defective, slang or ungrammatical. The factor is deviation-coded with the system of contrasts shown in Table 4.

Prescriptivism score: A continuous variable, ranging from 9 to 44, indicating the extent to which the participant subscribes to prescriptive ideology. The variable was standardised.

Lexeme frequency: The frequency of the lexeme in a lemmatised version of FrCoW (Schäfer 2015). The variable was first log-transformed (word frequency is known to have a power law distribution) then standardised.

Other demographic information: Age, gender and education of the participants were collected. Education was not found to be a useful predictor for the scores assigned to defective lexemes, and was excluded from the model. Age and gender were found to be correlated with judgements for defective words in interesting ways; however, they were also found to be multicollinear with prescriptivism and with each other. They were therefore not included in the main model for this reason. Nevertheless, their effect is discussed in Section 5.3.

System of contrasts for deviation coding of item condition.

| 2 | 3 | |

|---|---|---|

| Ungrammatical | −0.33 | −0.33 |

| Defective | 0.67 | −0.33 |

| Slang | −0.33 | 0.67 |

The model structure was iteratively chosen by combining hypothesis-guided data exploration with expert knowledge and model criticism. The first step involved listing all of the hypothesis-relevant factors that were expected to influence participant behaviour, and potential expected interactions between them. These terms were included in a maximal model, which was progressively stepped down, iteratively removing terms that were not crucial for our hypotheses if their credible interval included 0. The final model included the following terms:

First-order effects Item condition, task condition, participant prescriptivism score, and lexeme frequency were included as main terms.

Second-order interactions An x in Table 5 marks combinations of terms which were included as two-way interactions.

Third-order interactions A single third-order interaction was included, between item condition, task condition and prescriptivism score.

Random intercepts Participant and item were included as random intercepts.

Two-way interactions included in the model.

| Item cond | Task cond | Lexeme freq | Prescriptivism | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item cond | – | x | x | x |

| Task cond | – | x | ||

| Lexeme freq | – | |||

| Prescriptivism | – |

We considered random slopes for item condition and lexeme frequency over participant, and for task condition and prescriptivism over item.[19] Comparison between models with and without random slopes showed that the addition of random slopes did not noticeably improve the accuracy of the model. To reduce the likelihood of overfitting, we opted to remove random slopes.

5 Results

5.1 Descriptive statistics

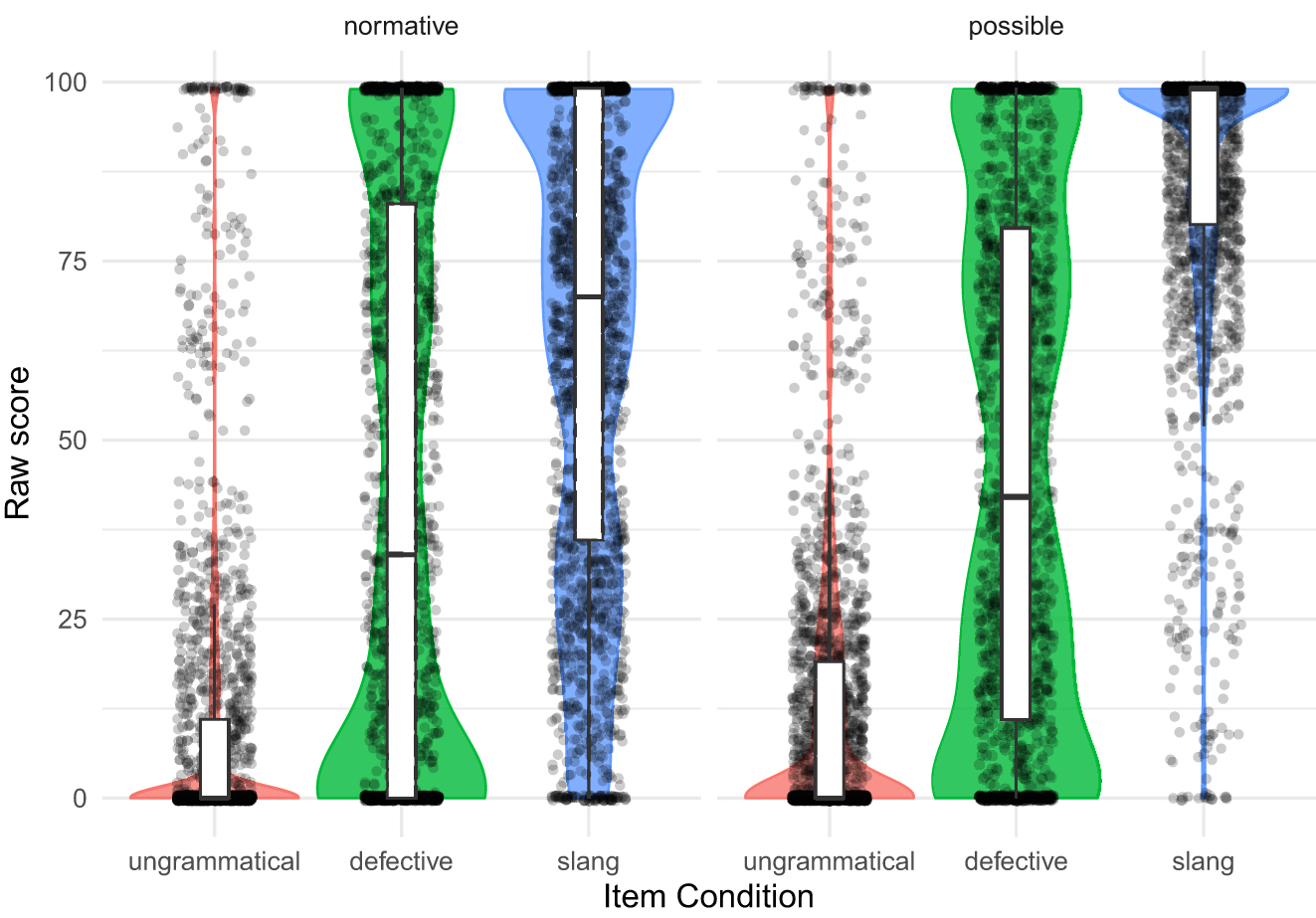

Figure 3 shows raw scores by task and item condition. Raw responses for ungrammatical items are generally at floor, though more clearly so in the normative condition. Raw responses for slang are at ceiling in the possibility condition, showing lower average scores and higher variability in the normativity condition. Raw scores for defective items show high variability in both task conditions. While extreme scores dominate, a large number of scores between the two ends of the scale can also be observed.

Raw scores by item and task condition.

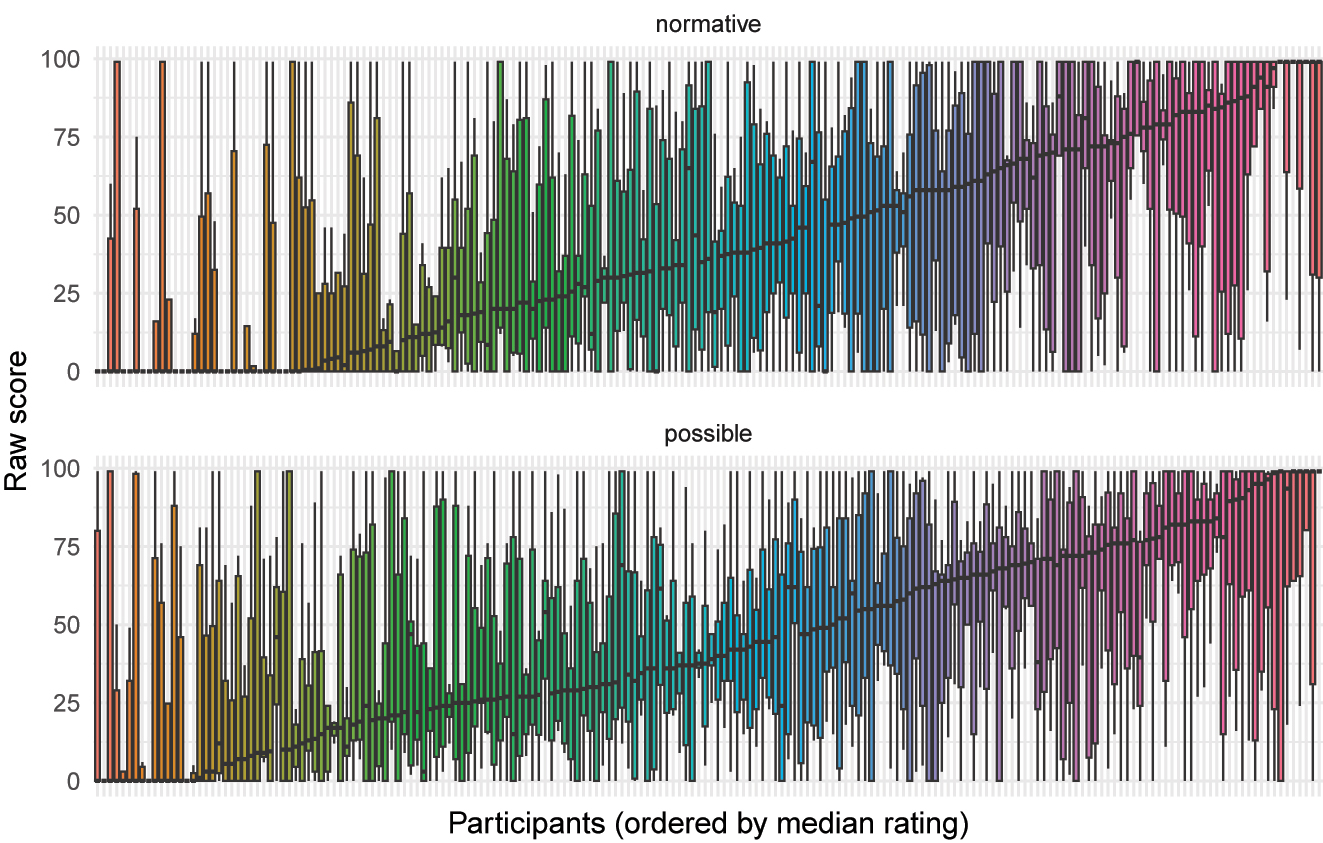

The variability for defective items is yielded by a combination of by-participant variability (Figure 4) and by-item variability (Figure 5). The extent of the variability in both dimensions is notable but expected.

Judgements for defective items grouped by participant, ordered by the participant’s median judgement for defective forms, marked by the black horizontal line. The vertical box for each participant represents the spread of their judgements for defective items.

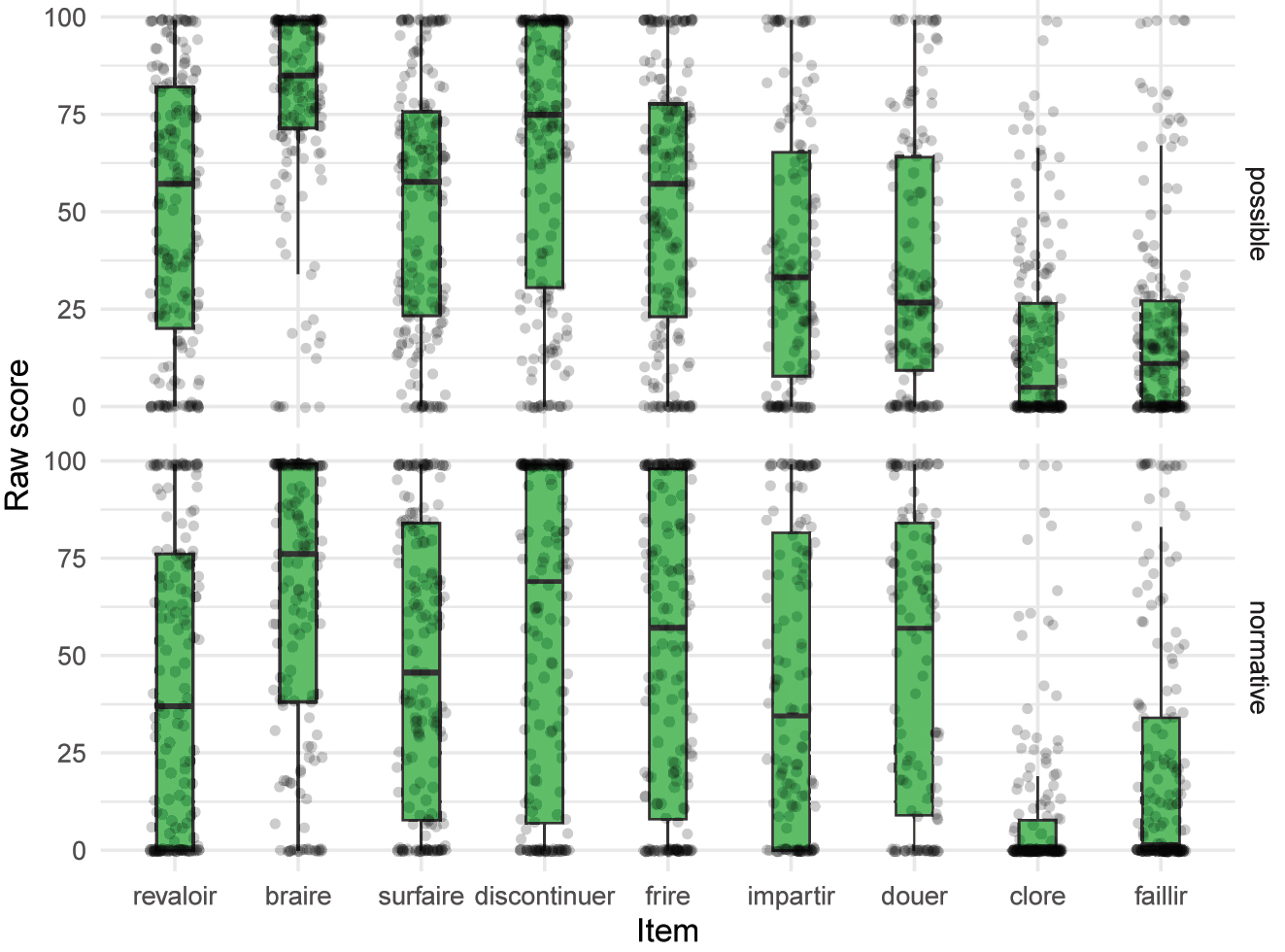

Judgements for defective items grouped by item, ordered by ascending lexeme frequency.

Figure 4 shows that in both task conditions, while there are participants who rated almost all defective items as unacceptable, there are others who rated almost all defective items as perfectly acceptable. In between the two extremes, some participants rated some defective items as fully acceptable, other items as if they were absolutely unacceptable, and yet others in the middle. In previous experimental studies on other languages, paradigm gaps have been observed to elicit gradient speaker judgements (e.g., Albright 2003; Pertsova and Kuznetsova 2015; Sims 2009), with disagreement among speakers about what inflected form should be used to fill a gap or the acceptability of possible gap-filling forms (Löwenadler 2010; Lukács et al. 2010; Nikolaev and Bermel 2022). Sims (2023) suggests that when it comes to which lexemes are judged to be defective, individual-level variation is perhaps even the norm, so this is not a surprising property to find in French verbal defectiveness.

Figure 5 shows that individual items also exhibited considerable range and variability in judgement. Some of the words described as defective by dictionaries are also judged unacceptable by speakers (for example closez, from the verb clore, although even for this datapoint there are participants giving a high rating). Others are felt to be almost perfectly acceptable (brayais from braire ‘to bray’). Items eliciting behaviour in between the two extremes are the majority of the data, and each defective item elicits judgements across the scale.

The variability seen for defective words at item and participant level is unique to the defective item condition. Table 6 shows the result of calculating the standard deviation within each participant or each item, grouping the standard deviations by item condition and taking the median value. The same participant rated ungrammatical and slang items much more consistently than they rated defective items, and the median defective item shows much more variability in scores than the median ungrammatical or slang item.

Median standard deviation by participant and item for the three item conditions.

| Ungrammatical | Defective | Slang | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median std. deviation by participant | 0.08 | 0.36 | 0.11 |

| Median std. deviation by item | 0.23 | 0.34 | 0.26 |

5.2 Statistical modelling

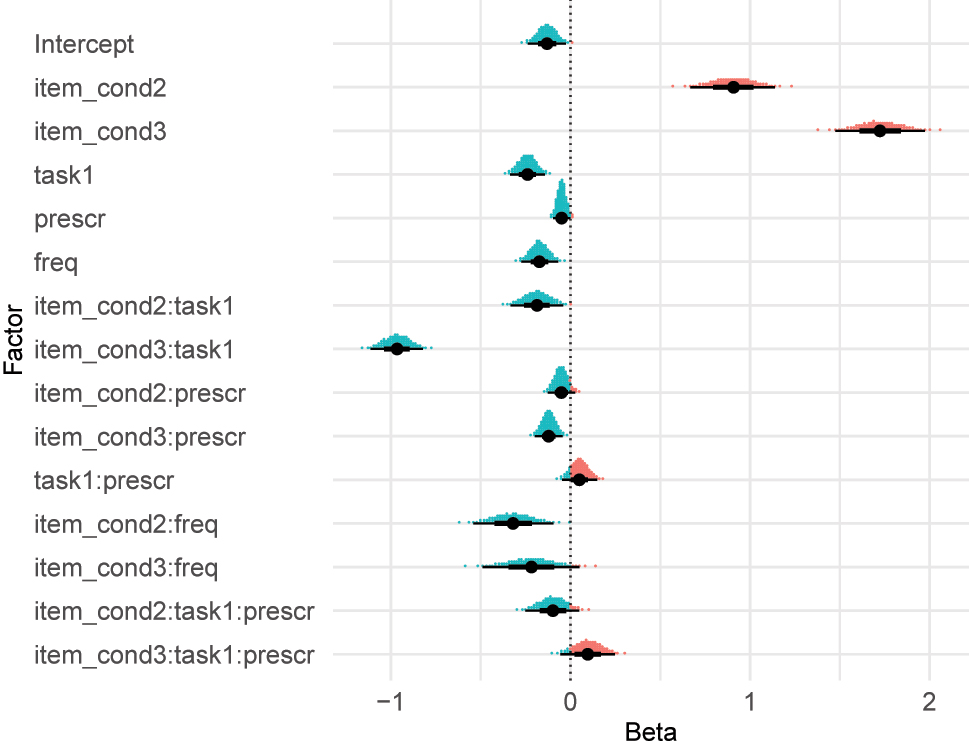

The model coefficients are presented in Table 7, and the posterior of the coefficients is visualised in Figure 6. The model has no divergent transitions, all R-hats are below 1.01 and Bulk-ESS and Tail-ESS are above 1,000 for all predictors in a model with 4 chains run for 4,000 iterations, signaling that the fitting process went smoothly and that the estimates are reliable.

Model coefficients. The labels have the following interpretation: item_cond has ungrammatical items as the reference level, compared to defective items (2) and slang (3). The variable is contrast-coded. task_cond has the possibility task as the reference level, compared to the normative task (1), and is contrast-coded. freq corresponds to the standardised effect of lexeme frequency, and prescr to the standardised effect of participant prescriptivism.

| Estimate | Est.Error | l-95 % CrI | u-95 % CrI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | −0.13 | 0.05 | −0.24 | −0.03 |

| item_cond2 | 0.91 | 0.12 | 0.67 | 1.14 |

| item_cond3 | 1.72 | 0.12 | 1.48 | 1.97 |

| task1 | −0.24 | 0.05 | −0.34 | −0.14 |

| prescr | −0.05 | 0.02 | −0.10 | −0.00 |

| freq | −0.17 | 0.05 | −0.27 | −0.07 |

| item_cond2:task1 | −0.19 | 0.07 | −0.33 | −0.04 |

| item_cond3:task1 | −0.97 | 0.07 | −1.11 | −0.82 |

| item_cond2:prescr | −0.05 | 0.04 | −0.13 | 0.03 |

| item_cond3:prescr | −0.12 | 0.04 | −0.20 | −0.04 |

| task1:prescr | 0.05 | 0.05 | −0.05 | 0.15 |

| item_cond2:freq | −0.32 | 0.11 | −0.54 | −0.10 |

| item_cond3:freq | −0.22 | 0.14 | −0.49 | 0.05 |

| item_cond2:task1:prescr | −0.10 | 0.08 | −0.25 | 0.05 |

| item_cond3:task1:prescr | 0.10 | 0.08 | −0.06 | 0.25 |

Posterior draws from the model estimates. The point represents the estimate with the highest posterior density. The thicker interval represents the area where 66 % of the posterior density is concentrated, and the thinner line represents where 95 % of the posterior density is concentrated.

The model was given weakly informative priors for the intercept

A strength of the Bayesian approach to statistical modelling is its ability to quantify uncertainty in a more direct and interpretable way. Instead of obtaining a point estimate for an effect and asking whether an effect is statistically significant, we can examine the entire posterior distribution to understand the range and probability of different parameter values. This allows for a richer and more informative analysis, where decisions are based on the probability of parameters lying within certain ranges, rather than a binary significance threshold. In this paper, we rely on evidence ratios for one-sided hypothesis tests to characterise the likelihood of the presence of an effect: this quantity conveys the model’s estimate for how much of the posterior distribution for a term lies above or below a certain value.

The model clearly shows that both defective and slang words were rated much better than ungrammatical items (large positive estimates for item_cond2 and item_cond3, CrI does not include 0). There is also a clear effect of task condition, where overall, the normative task reliably received worse scores than the possibility task (negative estimate for task_cond1, CrI does not include 0); participants gave harsher judgements when asked to think normatively. All of the posterior for the main effect of freq – lexeme frequency – lies below 0: overall, participants rated more frequent lexemes as worse than less frequent ones (This average behaviour is driven by defective items, as shown by the interactions discussed below.) Participant prescriptivism also has a highly likely negative effect, with 98 % of the posterior distribution for prescr lying below 0 (Evidence Ratio: 40.88, i.e., the effect of prescriptivism is 40.88 times more likely to be negative than positive): the more prescriptive a participant is, the worse their ratings tend to be.

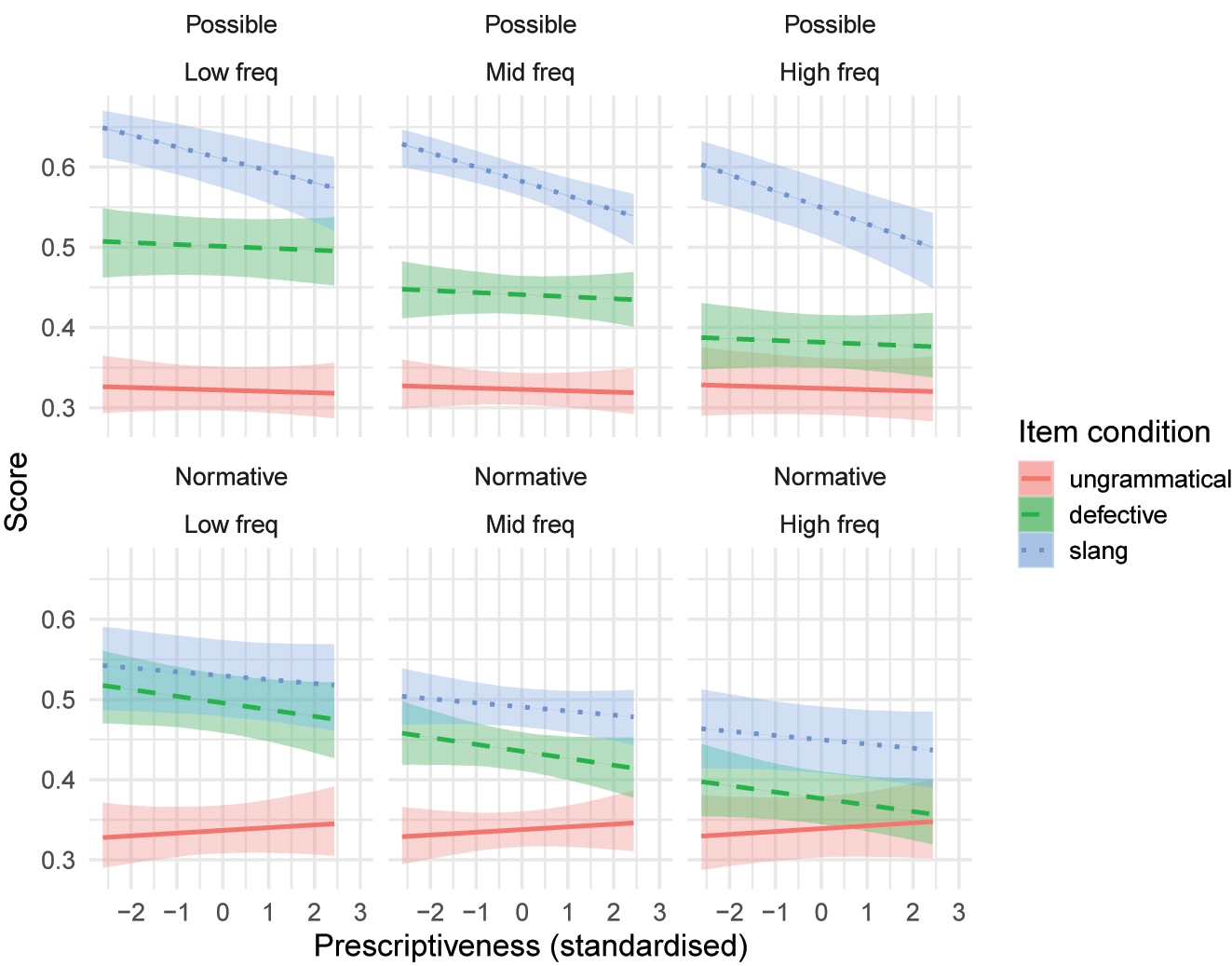

Our hypotheses involved complex interactions between factors. To facilitate inference, we present a conditional effects plot including all factors in the model to help visualise its predictions (Figure 7). Conditional effect plots for combinations of two variables are available with the analysis scripts (see the data availability statement at the end of the paper).

Conditional effects for the model in Table 7.

The conditional effects plot shows the model’s predictions for the interactions between all four variables of interest: task condition, item condition, participant prescriptivism, and lexeme frequency. Ungrammatical items receive low scores across the board, regardless of any other variable. They therefore successfully fulfil the role of baseline judgement for items that are not generated by the grammar. Task has a clear effect on judgements for defective and slang items: a clear large negative effect is visible for slang, which is rated much lower on average in the normative task, suggesting that the task manipulation is successfully tapping into participants’ normative tendencies. The difference between defective words and ungrammatical items is reduced in the normative task too (item_cond2:task1 has a negative coefficient with 99 % of the posterior below 0, ER: 108.59). The reduced effect size compared to item_cond3:task1 is likely the result of the high variability and bimodal behaviour for this class of items, discussed in Section 5.1.

The most important conditional predictor of the judgements for defective items is their lexeme’s frequency (item_cond2:freq is a medium-sized effect with a posterior fully below 0). In both tasks, more frequent defective lexemes are rated almost as poorly as ungrammatical items, while the least frequent defective lexemes are rated on par with slang in the normative task and just slightly worse on average in the possibility task. This same effect is visible in the raw data in Figure 5. Ungrammatical items do not show the same sensitivity to frequency, but slang items do to a lesser extent (item_cond3:freq has a posterior that is 94 % below 0, ER: 16.66). It is noteworthy that the effect of lexeme frequency on acceptability is negative for these two conditions. We interpret this to be a negative entrenchment effect, rooted in prescriptivism:[20] if defectiveness is in part the result of prescriptive pressures we might expect said pressures to affect the most frequent lexemes most severely, either by explicitly naming them as the object of a taboo, or by most strongly triggering an individual’s fear of uttering a wrong inflected form for a common lexeme, which would result in a social penalty of higher likelihood and magnitude. This hypothesis is given further credibility by the fact that a similar negative frequency effect is visible for slang items, where the narrative of negative entrenchment is readily available: speakers have a stronger dispreference for the use of frequent slang words.

Participant prescriptivism is also an important variable. A mostly positive (85 % above 0, ER: 5.82) coefficient for task1:prescr in combination with the negative coefficients for task1 and prescr suggests that the difference between judgements in the two tasks is on average a little smaller for high-prescriptivism participants. In both task conditions, more prescriptive participants rated both defective items (item_cond2:prescr has 80 % of its posterior below 0, ER: 4.08) and slang (all of the posterior for item_cond3:prescr is below 0) as worse on average than less prescriptive participants do.

A mostly positive coefficient for item_cond3:task1:prescr (98 % of the posterior above 0, ER: 39.2) indicates a positive tilt for the slope of slang items by prescriptivism (going from negative in the possibility task to relatively more neutral in the normative task). The more neutral slope is nevertheless coupled with a lower intercept in the normative task, suggesting that in the normative task, participants treat all slang words as more equal in their badness, with less regard for their frequency. The items can be observed to form a natural class when the task foregrounds normative proscription. In the possibility task, low-prescriptivism participants do give slang items higher scores, but high-prescriptivism participants give similar scores to slang in both tasks. This may suggest either a difficulty for high-prescriptivism participants to conform to the possibility task instructions, or confounds between prescriptivism and judgements such as age (further discussed in Section 5.3): for example, older participants are both more prescriptive and may be less likely to be exposed to youth slang in their daily life, which may result in the observed pattern. The mostly negative coefficient for defective items by task (88 % of the posterior for item_cond2:task_1:prescr is below 0, ER: 7.63) indicates a negative tilt of the slope by prescriptivism in the normative task compared to the possibility task, a tilt from flat to negative. In the possibility task, all participants treat defective words as equally bad on average, while in the normative task, defective items are rated worse by more prescriptive people.

5.3 The role of indexical factors

As previewed in Section 4.6, the indexical factors of age and gender were not included in the model presented in Table 7 and Figures 6 and 7, despite an observable effect on item conditions. This choice was made because both variables were found to be collinear with participant prescriptivism, a key variable of interest for this study, and subject to selection effects. This is expected: a participant’s degree of attunement to prescriptive attitudes is causally downstream of the individual’s lived experience. As the focus of the present study is on the effect of prescriptive attunement on the judgement of defective items, rather than on the factors that cause prescriptivism, we chose to leave out these two factors from the model in service of focusing on the research question posed by the study. Nevertheless, the effect of these factors is worth discussing.

Of the two variables, age appeared to have the biggest impact on how speakers judged defective items, with older participants rating defective items lower than younger participants, an effect that was exacerbated in the normative condition. However, participant age was found to be collinear with prescriptivism: older participants had almost exclusively high prescriptivism scores (Figure 8).

The relationship between age and prescriptivism.

Training a model on only the participants under age 40, for whom the correlation between age and prescriptivism is not as strong, replicates the main findings of the results reported in Table 7, indicating that the effect of prescriptivism cannot be reduced to age. However, adding age to a model that includes older participants greatly increases uncertainty about estimates involving prescriptivism score, it reverses the monotonicity of other effects, and age gains a clear interaction with item condition (older people rate defective words as worse than younger people do, particularly in the normative task condition). Combining knowledge about the causal relationship between prescriptivism and age with model criticism, we hypothesise that because age and prescriptivism are so closely linked in older participants, a model that includes both suffers from multicollinearity, and much of the variance that could be attributable to prescriptivism gets assigned to age (we speculate that this may be because age is a more parsimonious predictor of both reactions to defective words and to slang, the latter especially since it is associated with the way that young people speak). Nevertheless, it is possible to entertain a complementary causal story where age plays a role alongside prescriptivism in speakers’ reaction to defective words: age correlates with having more exposure to both language input and to metalinguistic attitudes about one’s language, which may lead to older people being more aware of which words are meant to be treated as defective, and to older people being more attuned to the desirability of communicating according to a specific linguistic standard (an effect mediated through prescriptivism). Because of the non-independence between age and prescriptivism in our sample, we are not able to comment further on this possibility, and leave it to further research.

Gender was also found to have an impact on speakers’ reaction to defective words: non-binary people were more accepting of defective words than people who identified as male or female, and people who identified as female were more accepting of defective words in the normative condition compared to those who identified as male. However, the effect of gender is confounded by its interaction with age and prescriptivism. As shown in Table 8, female and nonbinary people in our sample are younger than males, and nonbinary people are considerably less prescriptive than both men and women.

Median age and prescriptivism by gender.

| Gender | median prescriptivism score | median age |

|---|---|---|

| Male | 30.00 | 31.00 |

| Female | 27.00 | 25.00 |

| Non-binary | 18.00 | 25.00 |

Our sample size for nonbinary people (12 participants) does not allow us to disentangle the effects of gender, age and prescriptivism in participants’ judgements of defective words, which we leave as the object of future research.

6 Discussion

In this section we consider the implications of this study for theorising about the relationship between defectiveness, stigmatisation, and prescriptivism.

6.1 Defectiveness and stigmatisation

The paper explores the link between defectiveness and proscribed language. The strongest version of the hypothesis we have explored is that the grammar has no issue generating forms that dictionaries deem to be defective and their unacceptability comes instead from grammar-external social factors, such as a societal pressure to “speak correctly” and an individual’s desire to avoid uttering expressions that may be deemed “incorrect” by their linguistic peers. Under the strongest version of this hypothesis, we would expect identical behaviour between slang and defective items in the experiment, since both types of items would be grammatical but proscribed.

We find evidence that words deemed defective by French dictionaries are sensitive to prescriptive pressures: they are on average rated lower in the normative task compared to the possibility task, and they are generally rated lower by more prescriptive participants, especially in the normative task, and both tasks show a negative frequency effect. However, their behaviour is not the same as that of slang items: the average difference in scores between task conditions is smaller for defective items than for slang, and their pattern with respect to prescriptivism scores differs from slang in multiple respects. The predictions of the strongest version of the hypothesis that defectiveness is solely a result of stigmatisation are not verified, since defective items do not pattern with slang in all respects, most notably by having relatively low acceptability in the possibility condition. Nevertheless, the data shows that judgements for defective words show many of the hallmarks of stigmatisation.

The failure to find greater parallelism between the defective items and the slang items may reflect the formal nature of the defective items and the nature of the two task conditions. As noted in Section 4.2, we explicitly excluded all defective words that were marked in the dictionary as archaic or only used in formal registers. However, the set of nine defective items chosen still contains words that have distributional associations with formal usage.[21] Since the possibility task asked people whether the word would be out of place in everyday conversation, it is possible that more negative responses – especially for more frequent items, for which speakers are likely to have a good handle on their distribution – can be attributed to a mismatch between the inherent formality of the items and the inherent informality of everyday conversation. In contrast, for slang the inherent informality of the items aligned with the informality of the possibility task.

Nonetheless, the imperfect correspondence between defective and slang items suggests that the strongest version of the claim that defectiveness is stigmatisation is reductive and there are additional factors at play that affect defective items but not slang. In particular, we wonder about the role of structural factors. As noted in Section 3.2, in many cases defective lexemes, including the defective French verbs examined here, have identifiable structural properties that are implicated as partial causes of their defectiveness. Inasmuch as slang items may not have structural properties in common and are perfectly well-formed from the perspective of the grammar, this seems likely to be another thing differentiating how speakers judge the two kinds of items. While not the focus of the present study, grammatical structure is thus still an important piece of the puzzle of defectiveness. A full model of how the grammar works in tandem with prescriptive and other social factors to produce a felt sense of defectiveness in (French) speakers is a direction for future research.

6.2 The disconnect between productions and judgements

In this section we return to the issue that motivated us to investigate the relationship between defectiveness and prescriptivism in the first place. As outlined in Section 1, experimental evidence from various languages suggests that gap-filling words are not accepted and that speakers often dislike producing them. However, in French, gap-filling forms are found in naturalistic production (for instance, in corpora) with frequencies that are within expected ranges for non-defective words. There is thus seemingly a disconnect between speakers’ productions and their judgements. Different possible conciliatory narratives suggest themselves. We see these as potentially all at play.

First, it has long been observed that stigmatisation is contextually constructed, so even speakers who have a felt sense of the defectiveness for a given word might in fact use a gap-filling form in contexts where the risk of negative social sanction is low. In such a scenario, the stigmatisation of gap-filling would thus be detected in judgements, but gap-filling would also be expected to be observable in use. In particular, controlled production experiments where linguists ask participants to fill a gap in a sentence with a supposedly defective form, with participants knowing that their data will be collected, analysed and published by scientists, might lead to findings that tell us much more about the stigmatised nature of the phenomenon than about the linguistic rules that govern it. Acceptability studies are even more likely to engage metalinguistic thinking and judgement from participants, as in addition to the observer effects described above, they explicitly put the participant in an evaluative mindset.

Second, a disconnect between judgements and productions may also have a basis in language processing. Kapatsinski (2022) offers a specific proposal with regard to this possibility. In Kapatsinski’s model of production planning, forms that are partial matches for expressing some intended meaning are first activated and then at a second time step, activation of unintended meanings produces inhibition on the association. This negative feedback cycle results in multiple kinds of information being integrated at later stages of processing in a way that is sensitive to the needs of the communicative context. In part it thus determines how careful speakers are about their choice of words. This negative feedback cycle can result in delay to the start of production until some option emerges as sufficiently preferable to the others. However,

[T]he negative feedback cycle will not always complete before a form is sent to execution. The feedback cycle suggests, as Labov has also argued, that stigmatized productions are likely to slip through when the speaker’s attention is drawn away from stylistic connotations […]. It also predicts that such variants are likely to slip through if the speaker is under time pressure […]. A paradigm gap refers to the situation in which no form of a particular word is perceived as an acceptable filler for a particular paradigm cell […]. Therefore, speakers need to remember to avoid producing certain forms in formal contexts […]. By distinguishing between an initial stage of processing that generates multiple competing alternatives, and a subsequent stage in which these forms are suppressed by negative feedback, the negative feedback cycle explains how paradigm gaps can look like variation in everyday, casual language production, while generating distinctly different reactions in considered judgement, and being avoided in monitored speech and writing. (Kapatsinski 2022: 13)

Kapatsinski does not provide any test for his proposal, but it is congruent with our finding that judgements for defective items depended on both the task type (normativity- versus possibility-oriented judgements) and speakers’ orientation to prescriptive norms in ways that suggest that gap-filling is stigmatised in some contexts. Kapatsinski’s proposal thus offers a plausible mechanism by which metalinguistic knowledge of prescriptive norms and stigmatisation might affect production and metalinguistic judgement differently.