Abstract

This paper illustrates the crucial role of “internal locatives” (Maienborn, C. 2001. On the position and interpretation of locative modifiers. Natural Language Semantics 9(2). 191–240.) in the clause-internal distribution and interpretation of locative expressions headed by the stative locative morpheme zài ‘be at’ in Mandarin Chinese. Internal locatives describe spatial properties that are part of an event described by a verb, contrasting with event locative modifiers in the Davidsonian sense. I show that zài locatives occur in up to four positions in the clause: two pre-verbal and two post-verbal. Internal location is encoded in (i) a lower pre-verbal modifier position and (ii) a compounding structure I label “V-zài”, where zài immediately follows the verb. Although both express internal location, the pre-verbal internal locative is a modifier, while V-zài forms a complex predicate with the preceding verb, implemented as set intersection and event summation respectively (Rothstein 2004. Structuring events: A study in the semantics of lexical aspect. Oxford: Blackwell). This distinction accounts for an asymmetry long-noted in the Chinese linguistics literature: with a manner of motion verb, pre-verbal zài only has a static location interpretation while V-zài allows both static and goal interpretations. Elsewhere, the outermost pre-verbal position hosts a Davidsonian event modifier, while the post-verbal complement position (following verb and object nominal) hosts locative arguments, available only with certain verb classes, e.g., verbs of putting. This work presents a finer-grained view of how locative components integrate into the clause, bringing together research on locative modification and research on the encoding of locative result, which hitherto have tended to be explored independently of each other. Finally, it highlights the crosslinguistic relevance of internal locatives, originally described in German.

1 Introduction

Locative expressions may be integrated into a clause in more ways than one. Bierwisch (1988) notes, for instance, that locative expressions may serve as predicate (1), argument (2), or adjunct (3) in a clause.[1]

| ‘The bird is on the roof.’ (Predicate) |

| ‘The book lay *(on the table).’ (Argument) |

| ‘Mary read a book on the plane.’ (Adjunct) |

| (Gehrke 2008: 22 (31)) |

Despite the apparent illustrativeness of the preceding examples, the grammatical status of a locative expression is often difficult to determine in practice, and locatives have been approached variously as predicates (Wunderlich 1991), predicate modifiers and predicate extensors (Nam 1995), as either adjuncts or arguments (Kracht 2002), and even only as arguments (Creary et al. 1989).

The distinction between argument and adjunct is closely related to verb meaning, which in turn is a crucial determinant of how locative expressions in a clause are interpreted. In particular, locative expressions that describe static location may also be associated with notions of directionality and result – for which I will also frequently employ the term “goal” – typically when they occur with verbs of putting (4) and verbs of motion (5).

| ‘I told the children to put their toys back in the box.’ (i.e., ‘into the box’) (Thomas 2001: 95 (15a)) |

| ‘I ran in the office.’ (i.e., ‘into the office’) (Thomas 2001: 87 (1)) |

This paper explores the syntactic distribution and interpretation of the stative locative phrases headed by the locative morpheme zài ‘be at’ in Mandarin Chinese, exemplified in its main predicate use in (6).

| shū | zài | zhuōzi-shàng |

| book | be.at | table-upon |

| ‘The book is on the table.’ | ||

Main predicate zài ‘be at’ is not the main focus of this work, which will be more concerned with cases where the locative phrase occurs with a verb. In this case, the locative phrase may be placed either before the verb (7), or after it (8) (Li and Thompson 1981: 397).

| nǐ | yéye | zài | nǎli | zhù? |

| 2sg | grandfather | be.at | where | live |

| ‘Where does your grandfather live?’ | ||||

| (CCL: Hán Hán’s Blog)2 | ||||

- 2

“CCL” indicates data from Zhan et al. (2003), available online at the website of the Center for Chinese Linguistics (abbreviated as CCL) of Peking University, http://ccl.pku.edu.cn:8080/ccl_corpus. “BCC” indicates data from the Beijing Language and Culture University Modern Chinese corpus, available online at http://bcc.blcu.edu.cn/.

| nǐ | zhù | zài | nǎli? |

| 2sg | live | be.at | where |

| ‘Where do you live?’ | |||

| (CCL: Lǐ Áo conversation transcripts) | |||

Previous works have demonstrated certain asymmetries between locative zài in pre- and post-verbal position. For instance, the pre-verbal position is generally less restrictive for zài than the post-verbal, as suggested by the pair of examples in (9) and (10).

| dàjiā | …zài | shāngǔ-lǐ | kǎo | yángròu |

| everyone | …be.at | valley-within | roast | mutton |

| ‘Everyone …roasted mutton in the valley.’ | ||||

| (BCC: People’s Daily 1998) | ||||

| *dàjiā | kǎo | yángròu | zài | shāngǔ-lǐ |

| everyone | roast | mutton | be.at | valley-within |

| Intended: as in (9) | ||||

Yet post-verbal zài shows some kind of freedom not exhibited in pre-verbal position, in that post-verbal zài may yield a directional or goal interpretation (11), while this is not possible in pre-verbal position (12) (Li and Thompson 1981: 399; Tai 1975).

| xiǎo | hóuzi | tiào | zài | mǎ-bèi-shang | |

| small | monkey | jump | be.at | horse-back-upon | |

| ‘The little monkey jumped onto the horse’s back.’ | goal | ||||

| xiǎo | hóuzi | zài | mǎ-bèi-shang | tiào | |

| small | monkey | be.at | horse-back-upon | jump | |

| ‘The little monkey is on the horse’s back jumping.’ | static location | ||||

It should further be stressed that, apart from directional or goal interpretations, post-verbal zài may also encode static location (Tham 2013), a point that has not always received sufficient attention in previous discussions, but which will be important for the current work.

Within the pre- and post-verbal positions, other questions also remain unsettled. First, there is some disagreement among scholars whether post-verbal zài allows a nominal to intervene between verb and locative. Some works have claimed that post-verbal zài must occur immediately after the verb (Li and Thompson 1981: 406; Wang 1957), while others contend that a theme nominal is allowed between verb and locative, as long as the theme NP contains a numeral and classifier (Fan 1982: 72 (2b)). Second, locative expressions in pre-verbal position seem to call for a further distinction (Shao 1982). The pre-verbal locatives in (9) and (12) can be said to describe event location – the place where the event described by the rest of the clause is situated. This assumption cannot, however, apply to (13), which also contains a pre-verbal locative.

In this example, the zài phrase expresses a locative relation that forms part of the event description itself, and not event location. Anticipating the upcoming discussion, the locative relation in (13) will be termed an “internal locative” following the work of Maienborn (2000, 2001, 2003).

| nǎinai | …zài | lú-huǒ-gài-shang | kǎo | báishǔgān |

| grandmother | be.at | stove-fire-lid-upon | roast | dried.sweet.potato |

| ‘Grandmother roasted preserved sweet potato on the stovelid.’ (BCC: People’s Daily 2012) | ||||

| internal location | ||||

Maienborn distinguishes between event or “external” locative modifiers in the classic Davidsonian sense (14), and internal locative modifiers, exemplified in (15). While in (14), the PP specifies the location of the event of Eva signing the contract, in (15), the PP describes only the “location” of some part of the signing event – the location where the signature is inscribed.

| ‘Eva signed the contract in Argentina.’ |

| ‘Eva signed the contract on a separate page.’ |

In what follows, I argue that the notion of internal location is a crucial thread running through the distributional and interpretational paradigm of zài locatives in Mandarin. Internal location will be relevant in explicating each of the asymmetries between pre- and post-verbal zài listed above. An important point to note is that I utilize “internal location” as a conceptual notion that is not tied to a single syntactic position, deviating from Maienborn’s analysis of German locatives. Correspondingly, a conceptual component is an important part of the current analysis of Mandarin locatives, and I will show that the interpretation of zài locatives is dependent on both structural and conceptual factors.

In general, the discussion leans towards delineating semantic and conceptual factors, with syntactic factors playing more of a supportive role in the exposition, although strong emphasis is placed on empirical motivation for structural distinctions.

The paper proceeds as follows: Section 2 prefaces the discussion with some background, relating the current proposal to previous works, and laying out assumptions about the zài locative and the components of verb meaning relevant to how zài is interpreted in context. The rest of the paper can be considered to comprise two major parts. Sections 3 and 4 make up the first part, surveying the distribution of zài and the interpretations available to each of its positions. Addressing the unresolved questions noted above, these two sections identify four possible structural positions for zài locatives. In showing that internal locatives are found both pre- and post-verbally, these sections also highlight the need to recognize a category of internal location, apart from event location. Having established these structural contrasts and motivated the notion of internal location for Mandarin, the second part of the paper turns to the interpretation of internal locatives in different positions. Section 5 presents a pragmatic account of the interpretation of internal locatives in pre-verbal position, in the spirit of Maienborn (2000, 2001, 2003). Section 6 compares the differences between pre-verbal internal locatives and the V-zài structure, showing that, while both positions encode internal locations, V-zài alone allows goal interpretations not available from the verb. I take V-zài to be an instance of complex predication, adopting Rothstein’s (2003, 2004) event summing analysis to represent their meaning. Section 7 concludes with a brief discussion of the historical factors behind the varied interpretations of zài, and the theoretical distinctions highlighted by this work.

2 Preliminaries

This prefatory section lays down some groundwork to facilitate the upcoming discussion. I first place the coverage of the current work into some historical perspective to highlight its relative comprehensiveness, and then present my assumptions about the zài locative itself.

2.1 The current proposal in perspective

The distribution and interpretation of the zài locative in Mandarin has long been a subject of discussion in the Chinese linguistics literature (Chen 1978; Fan 1982; Li and Thompson 1981: 390–409; Liu 2009; Shao 1982; Tai 1975; Wang 1980; Zhu 1981 to list some of the better known works). It is thus worth taking a moment to provide some perspective on where the current work stands in relation to previous studies.

This work describes the interpretations of Mandarin zài locatives according to whether they occur pre- or post-verbally. Some of this discussion will overlap with earlier literature, for instance, it will maintain the general acknowledgement that modifiers occur freely pre-verbally, but are restricted post-verbally in Mandarin. It will also clarify the correlation between post-verbal position and goal interpretations noted in earlier work (Tai 1975; Wang 1980), one pointed out by various researchers to be only partial (Fan 1982; Liu 2009; Shao 1982; Zhu 1981).

Specifics aside, previous discussions have mainly focused on post-verbal zài given its more apparent complexity, and on cases where zài is immediately post-verbal. The current proposal departs from earlier work in two ways. First, by taking seriously the abovementioned distinction made by Maienborn between internal and external locatives, I show that pre-verbal position conceals greater complexity than previously noted in that there are actually two distinct pre-verbal positions, one for internal locatives, and one for event locatives. Second, I identify two distinct structures for zài in post-verbal position, a point which similarly has not been sufficiently illustrated in prior research.

This investigation yields a distributional paradigm of four positions for zài locatives. I argue that a two-way distinction between internal location, inclusive of locative arguments, as opposed to event location, provides a useful characterization of the syntax/semantics mapping for zài locatives in the clause. Specifically, event locatives occur in the higher pre-verbal position in the clause (assumed to be above vP), while internal locatives are found in the three lower positions identified (vP and below). Each position, however, integrates differently with the rest of the clause, so an internal locative combines variously as modifier, co-predicate in a complex predication, or argument, as outlined in the representations below.

| [ …zàiP event loc [ vP zàiP internal loc/arg (modifier) [ VP V-zài internal loc/arg (complex predicate)]] |

| [ VP V DP zàiP arg ] |

2.2 The meaning of zài

Since this work is a discussion of locative phrases headed by the morpheme zài, it is necessary here to first briefly discuss the syntax and semantics of the locative morpheme itself. The morpheme zài is one of the so-called “coverbs” – morphemes that exhibit properties of both verbs (they are able to constitute the sole predicate of a clause) and prepositions (they may occur in adjunct positions with a main verb as illustrated throughout this work) (Li and Thompson 1981: 356–360). In this paper, the category of zài is not a crucial issue. I follow convention in assuming at least that zài in adjunct positions is a preposition, remaining agnostic about its category as a sole predicate. In general, however, I will simply refer to zài as a stative locative morpheme. The reader is free to assume other categorial classifications. It should also be noted that zài describes a stative locative relation. This is clear from its use as the main predicate – seen above in (6) – and its compatibility with stative verbs (17).

| zài | jiā-lǐ | zhù |

| be.at | home-within | live |

| ‘live at home’ | ||

| zhù | zài | jiā-lǐ |

| live | be.at | home-within |

| ‘live at home’ | ||

Sun (2008, 2011) argues that the complement of zài is a “spatial NP”. A spatial NP may take the form of a place name, e.g. Shànghǎi (18a), or consist of a nominal describing an ordinary object in combination with a spatial morpheme such as -shàng ‘upon’, -lǐ ‘within’, as in (18b). (18c) shows that zài cannot occur with a noun describing an ordinary object if the spatial morpheme is absent. In addition, spatial NPs may also be headed by nouns that describe entities typically understood as places, e.g. xuéxiào ‘school’, yínháng ‘bank’ (18d), for which the spatial morpheme is optional (18e).[3] The spatial morphemes such as -shàng ‘upon’, -lǐ ‘within’ have been argued to be clitics (Liu 1998). For current purposes, their morphological status is not crucial.

| zài Shànghai |

| be.at Shanghai |

| zài hézi-lǐ/shàng/xià … |

| be.at box-within/upon/under |

| ‘be in/on/under …the box’ |

| *zài hézi |

| be.at box |

| zài xuéxiào |

| be.at school |

| zài xuéxiào-lǐ/wài/páng … |

| be.at school-within/outside/side |

| ‘be in/outside of/beside …the school’ |

Sun’s spatial NPs are perhaps more appropriately understood as spatial DPs, since the spatial morphemes attach to nominals inclusive of numerals and demonstratives. In (19), the horizontal surface described by the spatial morpheme applies to all the relevant three sheets of paper.

| [ DP nà | sān | zhāng | zhǐ]-shang |

| that | three | clf | paper-upon |

| ‘on those three sheets of paper’ | |||

I will thus refer below to spatial DPs rather than spatial NPs. I take spatial DPs to denote a particular type of individual – a region, of type r. The basic semantics of the morpheme zài is represented as the predicate loc, a relation between a type e individual and a spatial region of type r (20a) (Wunderlich 1991). I assume that zài as a predicate denotes a set of states, which I take to be included in the set of events, of type v. As a main predicate, for instance, zài will provide an event variable, as in (20b).

| zài: λrλx loc(x, r) |

| zài: λrλx λe loc(x, r)(e) |

The meaning of a phrase such as (21) may correspond to (21a), when the locative phrase integrates into the clause as a modifier or as an argument, or to (21b), when it is a predicate.[4]

| zài | hézi-lǐ |

| be.at | box-within |

| ‘(be) in the box’ | |

| λx [loc(x, interior(the box))] |

| λxλe [loc(x, interior(the box))(e)] |

2.3 Goal interpretations and verb meaning

An investigation of locative modification is simultaneously an exploration of locative elements in verb meaning. Across languages, stative locative expressions are known to allow goal interpretations in combination with different types of verbs, and in different contexts. This was briefly illustrated above with examples from English (4)–(5) and Mandarin (11). Locative expressions may take on goal interpretations when they occur with verbs that themselves either encode or implicate goal meanings, e.g. verbs of putting and with verbs of directed motion such as (the counterparts of) English go, fall, etc. (see e.g. Cummins 1996; Fábregas 2007; Gehrke 2007; Song 1997; Song and Levin 1998; Thomas 2004, among many others. For further discussion and references see Beavers et al. 2010: 12). In addition, locative expressions may also yield goal readings with manner of motion verbs that are not apparently associated with goal meanings, as seen in (4)–(5) and (11), raising questions as to the source of directionality in these examples. For some researchers, such examples have been taken to indicate lexical ambiguity in the relevant motion verb (Alonge 1997; Fábregas 2007; Folli and Ramchand 2005). Other researchers have argued for a pragmatic approach (Levin et al. 2009; Nikitina 2008; Tutton 2009) that attributes goal readings with manner of motion verbs to particular properties of the motion event description (see also the discussion in Beavers et al. 2010: 32–35).

These phenomena and the issues they raise are equally important in the study of zài locatives. As the discussion progresses, it will become clear that the motion specifications of different verb types in Mandarin are relevant for first, whether a zài phrase may show a goal interpretation, and second, whether a goal interpretation, if available, is found only post-verbally or also pre-verbally. I will eventually distinguish between three categories of verbs based on the extent to which they allow a goal of motion to be inferred. I will propose that (i) verbs that describe a caused change of location such as a putting event, e.g. fàng ‘put’, bǎi ‘(to) place’ entail a goal, and allow goal readings for zài locatives both pre- and post-verbally (Section 4.1); (ii) path verbs that describe directed motion, e.g. diào ‘drop’, luò ‘fall’ strongly implicate a goal, and these also allow goal readings for zài locatives both pre- and post-verbally, with post-verbal position preferred (Section 5.4); (iii) manner of motion verbs such as fēi ‘fly’, tiào ‘jump’, etc. weakly implicate a goal, and allow goal readings for zài locatives only post-verbally (Section 6.1). Finally, verbs that allow no inference of directed motion, including those that do not describe motion, e.g., zhǔ ‘cook’, jiáo ‘chew’, etc., do not give rise to any goal readings with zài locatives, even though they allow zài to occur after them.

I now turn to the distribution of zài phrases, relating the asymmetries and characteristics of different positions of zài locatives to their interpretation. The discussion begins with pre-verbal zài phrases in the next section.

3 zài locatives in pre-verbal position

The zài locatives in pre-verbal position have traditionally received less attention in previous works, although Shao (1982) and Yu (1999) are notable exceptions. These works do not, however, link the variable interpretations of pre-verbal zài phrases to their syntactic realization. This section argues that zài locatives occur in two pre-verbal positions, with event locatives occupying a higher position than internal locatives.

3.1 Event location occurs only in pre-verbal position

The most obvious asymmetry between pre- and post-verbal zài is that demonstrated between (9) and (10), repeated below. The pre-verbal locative phrase in (9) is straightforwardly understood as an event modifier, describing the location of the mutton-roasting event. Adopting Maienborn’s (2000, 2001) terminology, the zài phrase here describes event location, or external location, a location that is external to the event. For Maienborn, the term “external” also makes reference to the syntactic position of the relevant locative phrase, a point that will also be relevant for the Mandarin data.

| dàjiā | …zài | shāngǔ-lǐ | kǎo | yángròu |

| everyone | …be.at | valley-within | roast | mutton |

| ‘Everyone …roasted mutton in the valley.’ | ||||

| (BCC: People’s Daily 1998) | ||||

| *dàjiā | kǎo | yángròu | zài | shāngǔ-lǐ |

| everyone | roast | mutton | be.at | valley-within |

| Intended: as in (9) | ||||

Example (10) illustrates that event locatives are unacceptable in post-verbal position, consistent with general observations that modifiers in Mandarin occur pre-verbally to a large extent, and are restricted post-verbally (see Ernst 2014: 50 and references cited therein).

The semantics of event locative modification may be obtained by applying Maienborn’s MOD template (22), which conjoins a modifier and the expression to be modified.

| MOD: λPλQλx [P(x) & Q(x)] |

The zài phrase simply denotes the set of entities located at a certain location. In (23), for instance, the zài phrase denotes the set of entities located in the valley, which may include events (23a).[5] In external modifier position, the locative phrase is an event modifier, and in applying the MOD template, the relevant variable is constrained to be an event variable (see the discussion in Maienborn 2001: 216). This gives the event modifier in (23b). Combined with the rest of the clause, before existential binding of the event variable, gives us the set of events in which Sanmao roasts mutton in the valley (23c).

| Sānmáo | zài | shāngǔ-lǐ | kǎo | yángròu |

| name | be.at | valley-within | roast | mutton |

| ‘Sanmao roasted mutton in the valley.’ | ||||

| zài shāngǔ-lǐ ‘be in the valley’: λx [loc(x, in(the.valley)] |

| zài shāngǔ-lǐ ‘be in the valley’ as event modifier: λPλe [P(e) & loc(e, in(the.valley)] |

| λe∃z [roast(e) & agent(e, sanmao) & theme(e, z) & mutton(z) & loc(e, in(the.valley))] |

3.2 More in pre-verbal position: internal locatives

Perhaps a more intriguing question raised by the pre-verbal position is the contrast between event locatives, as in (9) above, and internal locatives, as in (13), repeated below as (24).

| nǎinai | …zài | lú-huǒ-gài-shang | kǎo | báishǔgān |

| grandmother | be.at | stove-fire-lid-upon | roast | dried.sweet.potato |

| ‘Grandmother roasted preserved sweet potato on the stovelid.’ (BCC: People’s Daily 1962) | ||||

| internal location | ||||

At first pass, internal locatives appear to describe the location of some entity denoted by an argument nominal. This is an oversimplification, however, as examples below will show. Maienborn (2001: 221) notes that “an internal modifier elaborates on independently established spatial constraints which are part of the conceptual knowledge that is associated with the respective eventuality type”, also observing that “suitable candidates are not confined to the entities referred to by the arguments of the verb, but also include referents introduced by incorporated arguments and modifiers as well as entities that are not overtly expressed but can only be inferred on the basis of conceptual knowledge” (2001: 218). A wider range of examples easily conveys these varying interpretations of internal locatives, which depend on the kind of situation described by the verb. With verbs of contact such as dǎ ‘hit’, pāi ‘smack’, for instance, an internal locative encodes the surface of contact, as in (25) and (26). The contact relation holds between the hitting entity – in (25) inferred to be the hand of the agent of smacking or patting, in (26) explicitly encoded by an instrument phrase.

| tāmen huì zài niánqı̄ng de huìyuán jiānbǎng-shang pāi jǐ xià |

| 3pl will be.at young assoc member shoulder-upon tap several time |

| ‘They will pat the young members on the shoulder a few times.’ (CCL: People’s Daily 1996) |

| …yòng | dāo | zài | yú | tóu-dǐng-shàng | pāi | … |

| use | knife | be.at | fish | head-top-upon | smack | … |

| ‘…smack on top of the fish head with a knife’ (CCL: Càipǔ dàquán)6 | ||||||

- 6

Càipǔ dàquán: roughly “A comprehensive collection of recipes”.

In some cases, the internal locative phrase specifies a manner of some action, as in (27), where the zài phrase describes how the dancing is performed (en pointe), rather than the location of any entity in the dancing event.

| zài | zú-jiān-shang | tiào | wǔ |

| be.at | foot-tip-upon | jump | dance |

| ‘dance en pointe (lit. on the tips of the feet)’ (https://www.jucong.com/excerptx/224741112) | |||

An important point to further note is that the internal locative phrase is not restricted to predicating of an internal argument, although that is the case in the more typical examples such as (24). In (26), for instance, the locative predicate applies to the instrument nominal, while in (27), it pertains to the agent. Below, I show that event locations are realized in a higher phrasal position than pre-verbal internal locations and goals.

3.3 Two positions for pre-verbal locatives

This section argues that the distinction between event and internal locatives is not merely a semantic one, and that the relevant locative phrases are realized in different structural positions. Three kinds of data support the structural distinction. First, event and internal zài phrases may co-occur, and when they do, the event modifier always occurs to the left of the internal modifier (28).

| Sānmáo | zài | lóuxià | zài | wǒ | jiān-shang | dǎ-le |

| Sanmao | be.at | downstairs | be.at | 1sg | shoulder-upon | hit-pfv |

| wǒ | yì | quán | ||||

| 1sg | one | fist | ||||

| ‘Sanmao punched me once on the shoulder downstairs.’ | (event loc > internal loc) | |||||

| *Sānmáo | zài | wǒ | jiān-shang | zài | lóuxià | dǎ-le | wǒ |

| Sanmao | be.at | 1sg | shoulder-upon | be.at | downstairs | hit-pfv | 1sg |

| yì | quán | ||||||

| one | fist | ||||||

| Intended: as above | (*internal loc > event loc) | ||||||

Second, the placement of manner adverbs and third, that of imperfective subordinate clauses, further discriminate between event and internal locatives. Manner adverbs may occur on either side of the internal locative, as shown in (29), where a manner adverb occurs to the right and to the left of the internal locative respectively.

| Sānmáo | zài | wǒ | jiān-shang | zhòngzhong-de | dǎ-le |

| Sanmao | be.at | 1sg | shoulder-upon | heavy-adv | hit-pfv |

| wǒ | yì | quán | |||

| 1sg | one | fist | |||

| ‘Sanmao punched me hard once on the shoulder.’ | (internal loc > manner) | ||||

| Sānmáo | zhòngzhong-de | zài | wǒ | jiān-shang | dǎ-le |

| Sanmao | heavy-adv | be.at | 1sg | shoulder-upon | hit-pfv |

| wǒ | yì | quán | |||

| 1sg | one | fist | |||

| ‘Sanmao punched me hard once on the shoulder.’ | (manner > internal loc) | ||||

With an event locative, however, a manner adverb may only occur to the right of the locative, as the contrast between (30a) and (30b) demonstrates.

| Sānmáo | zài | lóuxià | zhòngzhong-de | dǎ-le | wǒ |

| Sanmao | be.at | downstairs | heavy-adv | hit-pfv | 1sg |

| yì | quán | ||||

| one | fist | ||||

| ‘Sanmao punched me hard once downstairs.’ | (event loc > manner) | ||||

| *Sānmáo | zhòngzhong-de | zài | lóuxià | dǎ-le | wǒ | yì |

| Sanmao | heavy-adv | be.at | downstairs | hit-pfv | 1sg | one |

| quán | ||||||

| fist | ||||||

| Intended: as in (30) | (*manner > event loc) | |||||

In contrast with manner adverbials, an imperfective subordinate clause co-occurs with event and internal locatives in the reverse sequence. A V-zhe subordinate clause may occur on either side of an event locative, as shown in (31), but can only occur to the left of an internal locative (compare the examples in (32)).

| Sānmáo | zài | chúfáng-lǐ | chūi-zhe | kǒushào | kǎo |

| Sanmao | be.at | kitchen-within | blow-ipfv | whistle | roast |

| mógu | |||||

| mushroom | |||||

| ‘Sanmao whistled as he roasted mushrooms in the kitchen.’ | (event loc > V-zhe) | ||||

| Sānmáo | chūi-zhe | kǒushào | zài | chúfáng-lǐ | kǎo | mógu | |

| Sanmao | blow-ipfv | whistle | be.at | fire-upon | roast | mushroom | |

| ‘Sanmao whistled as he roasted mushrooms in the kitchen.’ | (V-zhe > event loc) | ||||||

| Sānmáo | chūi-zhe | kǒushào | zài | huǒ-shang | kǎo | mógu | |

| Sanmao | blow-ipfv | whistle | be.at | fire-upon | roast | mushroom | |

| ‘Sanmao whistled as he roasted mushrooms on the fire.’ | (V-zhe > internal loc) | ||||||

| *Sānmáo | zài | huǒ-shang | chūi-zhe | kǒushào | kǎo | mógu | |

| Sanmao | be.at | fire-upon | blow-ipfv | whistle | roast | mushroom | |

| Intended: as above | (*internal loc > V-zhe) | ||||||

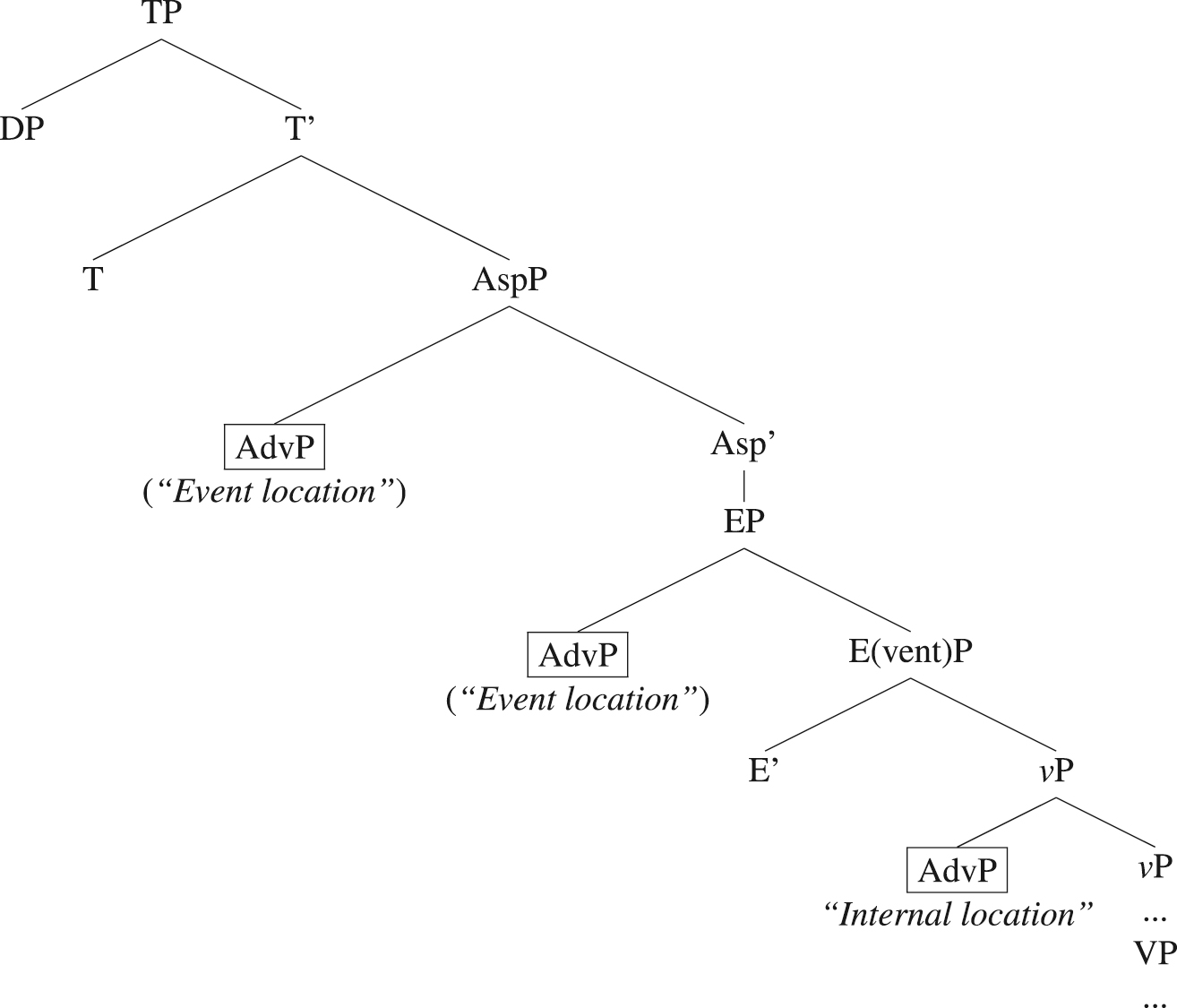

To account for these asymmetries, I adopt the structure for adverb placement posited in Ernst (2004: 760). I assume that internal locatives in Mandarin are adjoined to the left of vP (or its equivalent),[7] while external locatives, which are event modifiers, adjoin to a higher functional projection above vP but below TP. This could be EventP (Travis 2010) or AspectP (Huang et al. 2009), quite possibly varying based on information structural properties of the locative modifier.

The structural representation is given below in (33), with relevant positions for the pre-verbal placement of a zài locative phrase highlighted via boxed text.

Following the discussion in Ernst (2004), manner adverbs may also be assumed to adjoin to vP, where internal locatives also adjoin. This accounts for why there is no inherent ordering between manner adverbials and internal locatives. In contrast, event locatives are assumed to adjoin to a projection above vP, and thus are required to occur to the left of both manner adverbials and internal locatives. In the same vein, a V-zhe subordinate clause may be assumed to attach only to EventP. This captures the freedom of its ordering relative to event locatives, but the requirement that it occur to the left of participant locatives.

3.4 Pre-verbal goal zài phrases

To complete the picture, it should be added that, with verbs of putting such as fàng ‘put’, bǎi ‘place’, etc., to be discussed further in Section 4.1, a pre-verbal zài locative may also express goal or result location (34).

| tāmen | zài | lú-qián | bǎi-le | yì | zhāng | xiǎo | zhuō |

| 3-pl | be.at | stove-front | place-pfv | one | clf | small | table |

| ‘They placed a small table in front of the stove.’ (CCL: People’s Daily 1988) | |||||||

Given the above discussion, it is relatively straightforward to demonstrate that a pre-verbal zài phrase with a result reading attaches no higher than vP, i.e., the lower modification site. A goal-denoting pre-verbal locative phrase must follow an event locative and not vice versa (35).

| Sānmáo | zài | chúfáng-lǐ | zài | lúzi-shang | fàng-le | yí | zhı̄ | guō |

| Sanmao | be.at | kitchen-within | be.at | stove-upon | put-pfv | one | clf | pot |

| ‘Sanmao put a pot on the stove in the kitchen.’ | ||||||||

| *Sānmáo | zài | lúzi-shang | zài | chúfáng-lǐ | fàng-le | yí | zhı̄ | guō |

| Sanmao | be.at | kitchen-within | be.at | stove-upon | put-pfv | one | clf | pot |

| ‘Sanmao put a pot on the stove in the kitchen.’ | ||||||||

Moreover, the pre-verbal result locative phrase can only occur after an imperfective subordinate clause and not the other way around (36).

| Sānmáo | chūi-zhe | kǒushào | zài | lúzi-shang | fàng-le | yí | zhı̄ | guō |

| Sanmao | blow-ipfv | whistle | be.at | stove-upon | put-pfv | one | clf | pot |

| ‘Sanmao put a pot on the stove in the kitchen, whistling.’ | ||||||||

| *Sānmáo | zài | lúzi-shang | chūi-zhe | kǒushào | fàng-le | yí | zhı̄ | guō |

| Sanmao | be.at | stove-upon | blow-ipfv | whistle | put-pfv | one | clf | pot |

| ‘Sanmao put a pot on the stove in the kitchen, whistling.’ | ||||||||

I thus assume that the pre-verbal result locative attaches at the same level as the internal locative.

A consequence of this assumption is that pre-verbal result locatives, which should be considered arguments (see Section 4.1), would count as a special type of internal location. That is, all argument result locatives are internal locatives, although the class of internal locatives more generally includes adjuncts. One might ask whether the goal-denoting locative phrase as in (34) may co-occur with an internal locative. It is possible to find two zài phrases in internal modifier position, and the sequence could further include an event locative, as (37) illustrates.

| Sānmáo | [zài | shūfáng-lǐ] | [zài | shūjià-shang] | [zài | dì | sān | gé] |

| Sanmao | be.at | study-wthin | be.at | bookcase-upon | be.at | ordinal | three | shelf |

| fàng | le | yì | běn | shū | ||||

| put-pfv | one | clf | book | |||||

| ‘Sanmao put a book on the bookcase on the third shelf in the study.’ | ||||||||

Given that event locatives are adjuncts, and internal locatives may also be adjuncts, we should expect multiple instances in a sentence to be possible. Such instances would presumably be subject to some kind of monotonicity constraint in terms of the spatial regions they describe, so that the lower-adjoined locative describes a proper sub-region of the locative in the projection immediately above (Creary et al. 1989). It is not immediately clear to me, however, whether the last zài phrase in (37) should be considered an event-internal locative, or if it is rather a locative that further modifies the preceding argument locative. A proper investigation of the question of multiple pre-verbal zài phrases is beyond the scope of this study, and I set it aside for future research. In the next section, I turn to zài in post-verbal position, showing that, as in pre-verbal position, post-verbal zài is not a unitary phenomenon.

4 Post-verbal zài

This section presents data indicating that there are two post-verbal positions for zài, one a complement position following verb and object, the other an immediately post-verbal position. This point is worth specific mention because the great majority of discussions of post-verbal zài are limited to the cases where zài is immediately post-verbal, with Fan (1982) being a rare exception that brings up examples of zài following the object. Even so, the two structures for post-verbal zài were not distinguished. Therefore, this section makes it a point to clarify the two post-verbal positions for the locative.

4.1 zài in complement position

The naturally occurring data in (38–39) show the occurrence of locative zài phrases in complement position, i.e., after verb and object. I show below that complement zài phrases should be considered locative arguments in the sense of being a constituent selected by the verb.[8]

| mǔqin | jìn | fáng | lái, | fàng-le | yì | wǎn | jı̄dàn | zài | tā | chuáng-qián |

| mother | enter | room | come | put-pfv | one | bowl | egg | be.at | 3sg | bed-front |

| ‘Mother entered the room (and) put a bowl of eggs in front of his bed.’ (CCL: Liu, X. Tiānxíngzhě) | ||||||||||

| Hú-mā | …bǎi-le | yì | zhı̄ | bái | lúzi | zài | wūyán-xià |

| name-mother | place-pfv | one | clf | white | stove | be.at | roof-under |

| ‘Mother Hu placed a white stove under the roof.’ (BCC: Zhang, H. Yèshēnchén) goal | |||||||

To a speaker of English and presumably other configurational SVO languages, the points made in this section may seem quite obvious and unremarkable. To contextualize the discussion, it must be noted that in the Chinese linguistics literature, the existence of a complement locative structure is a surprisingly unsettled question. As noted above, discussions of post-verbal zài have almost exclusively been concerned with zài in immediately post-verbal position. Even when the existence of complement locatives has been explicitly acknowledged (Fan 1982), they have not been distinguished from zài in immediately post-verbal position.

This situation is likely due to two factors. First, dialectal variation: speakers of Northern varieties of Mandarin tend to disprefer zài in complement position, while this use tends to be accepted by speakers of varieties south of the Yangtze river, and in immigrant Mandarin-speaking communities in Southeast Asia.[9] This observation is based on personal consultations with Mandarin speakers from different regions. Second, information structural factors may be at work that require the theme object to be indefinite, with a numeral and classifier, as the examples below illustrate, and as also pointed out in Fan (1982). In particular, the object is less acceptable as a bare nominal, as in (40)–(41).

| #mǔqin | jìn | fáng | lái, | fàng-le | jı̄dàn | zài | tā | chuáng-qián |

| mother | enter | room | come | put-pfv | egg | be.at | 3sg | bed-front |

| Intended: ‘Mother entered the room (and) put eggs in front of his bed.’ | ||||||||

| #Hú-mā | bǎi-le | bái | lúzi | zài | wūyán-xià |

| name-mother | place-pfv | white | stove | be.at | roof-under |

| Intended: ‘Mother Hu placed (the) white stove(s) under the roof.’ | |||||

This variation notwithstanding, according to a consultant from Tianjin (Northern Mandarin), speakers of Northern varieties of Mandarin are able to accept complement locatives of suitable form (i.e., with indefinite Numeral + Classifier NP objects) in more formal and written registers, although these structures are strongly dispreferred in colloquial speech. The generalizations discussed here received confirmation in an online survey of 73 native speakers of Mandarin asked to rate 39 sentences containing zài locatives in different positions according to their “standardness” – whether these were acceptable as textbook examples, acceptable in daily speech, or unacceptable to varying degrees.[10] Sentences with a complement zài locative with an appropriate verb were acceptable for 90 % or more of respondents, regardless of their hometown region, with some variation in whether such sentences were considered “textbook” standard. The remaining speakers might not find these completely acceptable, but no respondent indicated complete unacceptability. Nonetheless, given the ambivalence of earlier researchers towards complement zài (which also suggests a role for language change), the discussion below errs on the side of comprehensiveness, presenting relatively detailed corpus data on complement zài to highlight both the attested presence of these structures in naturally occurring data, and their contrast with the V-zài structure in what follows.

A zài phrase in complement position is possible only with certain classes of verbs, in particular, verbs of putting such as fàng ‘put’, bǎi ‘place, arrange’, guà ‘hang’, chā ‘insert’, etc. As noted in the preceding subsection, with such verbs, the locative phrase may also occur pre-verbally (34). The preceding verbs may be understood as specifying for a goal. In addition, verbs of caused motion such as those in (42), which themselves might not be seen to require a goal, but are compatible with one being understood, also allow complement zài. The same is possible for verbs describing activities that may also be understood to effect a “putting” event (43).

| rēng, diū, pāo ‘toss, throw’; jiāo ‘pour, douse’; dào ‘pour’; lín ‘drizzle’; jiā ‘add (e.g. salt)’; chéng ‘ladle’; sǎ ‘scatter’ |

| tú, mǒ, cā ‘smear, wipe’; pēn ‘spray’; shuā ‘brush’ |

These data suggest that complement zài describes the goal in a putting event description. This characterization of locative complement verbs may be extended to certain classes of verbs of creation. One class of such verbs describes events of image creation, in which the zài phrase describes the surface where the created image resides (44)–(45). Some other verbs of this class are listed in (46). Verbs of building (47) also allow complement zài.

| xiě-le | jǐ | gè | zì | zài | hēibǎn-shàng |

| write-pfv | few | clf | character | be.at | blackboard-upon |

| ‘wrote a few characters on the blackboard’ (CCL: Yu, P. Mèngjì) | |||||

| wǒ | hái | xiù-le | zhı̄ | lǎoyı̄ng | zài | shàngtou |

| 1sg | further | embroider-pfv | clf | eagle | be.at | surface |

| ‘I even embroidered an eagle on (something).’ (BCC: Tao, T. Wǒ ài jiāomán niángzi) | ||||||

| diāo, kè ‘carve’; huà ‘draw/paint’; yìn ‘print’ |

| jiàn, gài ‘build’; shè ‘establish’ |

A slight complication is presented by the compatibility of complement zài with verbs of incarceration such as guān ‘shut’ (48), and similar verbs (49), as well as verbs of concealment such as cáng ‘hide’ (50), which describe events that may, but need not, involve a putting, also allow complement zài.[11]

| guān-le | yí | gè | xiǎohuǒzi | zài | fáng-lǐ |

| shut-pfv | one | clf | young.man | be.at | room-within |

| ‘shut a young man in the room’ (CCL: Fang, P. and Wang, K. transl. The Decameron) | |||||

| suǒ ‘lock’; fēng ‘seal’; mái ‘bury’; shuān ‘bolt’ |

| cáng-le | yì | bāo | dōngxi | zài | chuāng-wài | de | dòng-lǐbian |

| hide-pfv | one | bag | thing | be.at | window-outside | assoc | hole-inside |

| ‘hid a bag of stuff in the hole outside the window’ (CCL: Chu, B. F. Bāxı̄ kuánghuānjié) | |||||||

While events of incarceration such as that described by (48) could involve a putting event – i.e., the young man in question could have been pushed into the room and shut there – they need not. Example (48) would be true even in the case where the young man had already been in the room, and someone had shut the door, rendering him captive. Similarly, to cāng ‘hide/conceal’ something need not involve putting that item in a certain place, but could simply be done by covering up that item. That is, verbs such as cáng ‘hide/conceal’, guān ‘shut’ and those in (49) do not necessarily describe putting events. Rather, they describe a caused change of state that takes place while the theme is located somewhere (Fong 1997; Nikitina 2010).

Nevertheless, incarceration and concealment events share certain important features with putting events. First of all, as just noted, incarceration and concealment events may also unfold as putting events. Second, a putting event is a caused change of location, and a change of location may be considered a special kind of change of state. Third, as noted above, incarceration events involve a change of state that affects the relationship the theme bears to a location. Thus, both putting events and incarceration events may be more generally described as a caused change in locative situation, which may be interpreted simply as a change in location (in the case of putting events), or as a change in the relationship the theme bears to a location (in the case of incarceration events). It also seems reasonable to assume for verbs that describe a caused change of locative situation, that they select a locative argument, realized by a complement zài phrase.[12] I provide a representation for the meaning of such verbs, using fàng ‘put’ as an example:

| fàng ‘put’: λPLOC λy λx λe ∃e1 ∃e2 [e = S (e1 ⊔ e2) & put(e1) & agent(e1, x) & theme(e1, y) & PLOC(y)(e2) & cul(e) = e2] |

This representation draws on elements of Rothstein’s (2004) analysis of accomplishment events. A putting event is assumed to involve the summing of two events to form a singular event. The putting event consists of a “putting” activity sub-event, which culminates (cul) in a “near-instantaneous” sub-event (see Rothstein 2004: 36). This culminating event is that of the theme of the putting event being located someplace. The locative predicate applied to the theme argument (PLOC) is a predicative argument selected by the verb. This representation does not reflect the semantic analysis Rothstein ultimately puts forth for accomplishment events, which pays particular attention to incremental accomplishments. I adopt the representation in (51) for two reasons. First, events of putting (not discussed by Rothstein) cannot be considered incremental.[13] If someone puts a singular item at a location, the length of the putting activity does not in any sense bring the theme closer to the final location event. To illustrate, suppose one is trying to hang a painting on the wall. The painting is cumbersome and heavy, the worker is working alone, the nail is difficult to reach, etc. One can spend an hour doing various things to hang the painting, but the duration of this activity does not make the painting any more “on the wall”. Second, the summation analysis and the cul operator will become relevant for the discussion of V-zài locatives in Section 6.2.4, so the adoption of these elements here allows for a more streamlined discussion.

I assume that complement zài occurs – as suggested by its name – as a complement to V, as in (52), in line with works that associate the complement position of V for a result or goal interpretation (see e.g. Gehrke 2008: 83; Ramchand 2008: 39).

The complement zài phrase is selected by the verb as an argument, providing the goal interpretation. The VP, formed by combining with the object nominal meaning, then yields the following predicate:

| fàng yì běn shū zài zhuōzi-shang ‘put a book on the table’: |

| λe λx ∃y ∃e1 ∃e2 [e =S (e1 ⊔ e2) & put(e1) & agent(e1, x) & theme(e1, y) & book(y) & |

| loc(y, top(the.table))(e2) & cul(e) = e2] |

4.2 V-zài: a distinct position from complement zài

I now turn to zài in immediately post-verbal position, i.e., what I have been calling V-zài structures. I distinguish V-zài from complement zài, showing that more verbs occur in the V-zài structure than allow complement zài, and argue that at least in some cases V-zài should be considered as forming a compound. I show further that the notion of internal location is relevant not only pre-verbally, but also post-verbally, in the V-zài position.

4.2.1 V-zài expresses internal location and more

This subsection demonstrates that V-zài is compatible with a wider range of verbs and interpretations than complement zài. In particular, it is a position that hosts internal locatives. All the goal verbs discussed above that allow complement zài may also felicitously occur in a V-zài structure, as exemplified below.

| nà | gè | kōng | xiāngzi | bǎi | zài | yí | kuài | shítou-shang |

| that | clf | empty | box | place | be.at | one | slab | stone-upon |

| ‘That empty box was placed on a slab of stone.’ (BCC: Ba, J. Aìqing de sānbùqǔ (wù yǔ diàn)) | ||||||||

Apart from occurring with verbs of putting in their different senses, V-zài position may also express internal location, as shown in (55) and (56). These examples all seem to contain a transitive verb with its arguments not overtly realized. I defer discussion of this point to the next subsection, keeping the focus on the interpretations of V-zài for the time being.

| māma | dài-huí-lai | liǎng | zhāng | yùmǐ-bǐng, | kǎo | zài |

| mother | bring-return-come | two | clf | corn-flatbread | roast | be.at |

| heater.panel-upon | ||||||

| nuǎnqìpiàn-shang | ||||||

| ‘Mother brought home two pieces of corn flatbread, which were toasting on the heater panel.’ (BCC: People’s Daily 1998) | ||||||

| yùmǐ | shú | le, | jiáo | zài | zuǐ-lǐ, | yòu | nèn | yòu | xiāng |

| corn | ripe | sfprt | chew | be.at | mouth-within | again | tender | again | fragrant |

| ‘The corn was ripe, and chewed in the mouth, was tender and fragrant.’ (BCC: People’s Daily 1998) | |||||||||

| internal location | |||||||||

These meanings cannot be expressed via a typical transitive sentence structure with the locative after the object nominal, as (57) and (58) show. The zài phrases in these examples are, however, allowed pre-verbally (compare (24) above).

| *māma | kǎo-le | liǎng | zhāng | yùmǐ-bǐng | zài | nuǎnqìpiàn-shang |

| mother | roast-pfv | two | clf | corn-flatbread | be.at | heater.panel-upon |

| Intended: as in (55) | ||||||

| *wǒ | jiáo-le | yì | bǎ | yùmǐ | zài | zuǐ-lǐ |

| 1sg | chew-pfv | one | handful | corn | be.at | mouth-within |

| Intended: ‘I chewed a handful of corn in my mouth.’ | ||||||

Another contrast between V-zài and complement zài is that manner of motion verbs occur freely in the V-zài configuration (59), but they are not compatible with complement zài (60) (or more neutrally, with a locative phrase following the object nominal). This is so even though the relevant manner of motion verb, e.g. zǒu ‘walk’ in (60) can combine with an object (here a path-denoting nominal). Adding a locative phrase after the object as in (60) is unacceptable under any interpretation, whether stative or result.

| tā | zǒu | zài | mǎlù-shang |

| 3sg | walk | be.at | street-upon |

| ‘(S)he walked on the street.’ | |||

| tā | zǒu | le | yì | tiáo | xı̄n | lù | (*zài | hé-biān) |

| 3sg | walk | pfv | one | clf | new | road | be.at | river-side |

| Intended: ‘(S)he walked a new road/route to the river bank.’ | ||||||||

Even more notably, V-zài locatives allow for goal readings that, unlike for complement locatives, are not specified by, or inferrable from, verb meaning. I assume these goal readings to arise from the linguistic context, anticipating the discussion of V-zài locatives in Section 6. One example was seen earlier in (11), repeated below as (61). Here, zài occurs after the manner of motion verb tiào ‘jump’, and is interpreted as the goal of the jumping event. If the locative phrase is pre-verbal, however, only a static location interpretation is possible (62) (=(12)), an asymmetry noted in Tai (1975), from which the examples originate.

| xiǎo | hóuzi | tiào | zài | mǎ-bèi-shang | |

| small | monkey | jump | be.at | horse-back-upon | |

| ‘The little monkey jumped onto the horse’s back.’ (= (11)) | goal | ||||

| xiǎo | hóuzi | zài | mǎ-bèi-shang | tiào | |

| small | monkey | be.at | horse-back-upon | jump | |

| ‘The little monkey is on the horse’s back jumping.’ (= (12)) | static location | ||||

The phenomenon is more widespread than simply with manner of motion verbs. Verbs that do not entail (but may implicate) motion such as tuı̄ ‘push’ can be found in the V-zài structure with a goal interpretation, but for most speakers, cannot occur with complement zài (64).[14]

| màozi | tuı̄ | zài | hòunǎosháo-shang | |

| hat | push | be.at | back.of.head-upon | |

| ‘hats pushed back on the back of the head’ (CCL: Yan, G. Fúsāng) | goal | |||

| *tā | tuı̄-le | yì | dǐng | màozi | zài | hòunǎosháo-shang |

| 3sg | push-pfv | one | clf | hat | be.at | back.of.head-upon |

| Intended: ‘(S)he pushed a hat onto the back of the head.’ | ||||||

These examples indicate clearly that complement zài and V-zài are distinct structures. They show further that V-zài overlaps with pre-verbal internal locatives, but is unique in allowing for result interpretations with verbs that do not lexically specify for a goal, as in the case of manner of motion verbs.

4.2.2 V-zài as a compound

The preceding examples of V-zài exhibit a distinctive morphosyntactic characteristic: V-zài is an intransitive structure, allowing only one argument of V to be realized in subject position, even though V itself may be transitive, as (54)–(56) suggest. If V is intransitive, the sole argument of V is realized as subject of V-zài. With transitive V, the examples discussed so far may suggest that the subject of V-zài corresponds to the internal argument of V, but examples such as (65), in which the (pro-dropped) subject of V-zài presumably refers to the instrument rather than the agent or theme of the hitting, argue against this equivalence.

| wǒ | yuàn | tā | ná-zhe | xìxi | de | píbiān, | …qı̄ngqing | dǎ |

| 1sg | wish | she | hold-prog | thin-redup | assoc | whip | light-redup | hit |

| zài | wǒ | shēn-shang | ||||||

| be.at | 1sg | body-upon | ||||||

| ‘I wish that she would hold a thin whip (and) …hit me gently with it.’15 | ||||||||

- 15

This example lifts a line from a famous Chinese song in which the singer’s beloved is a shepherdess and the singer envisions himself as a lamb in her fold.

In (65), the subject of dǎ ‘hit’ plus zài remains the external argument of dǎ ‘hit’, but the locative relation holds between the instrument (the whip) and the theme of the hitting event. Example (66) presents a similar case, this time with the verb pái ‘smack/pat’.

| Hú Liǔ | jǔ-qǐ | càdāo, | pái | zài | zhēnbǎn-shàng | |

| name | raise-arise | chopper | smack | be at | chopping.board-upon | |

| ‘Hu Liu raised the chopper and smacked it on the chopping board.’ | (CCL: Ouyang, S. Kǔdòu) | |||||

In both examples, the verb itself requires an agentive subject. It is not possible to say *píbián dǎ-le wǒ ‘(the) whip hit-pfv me’ (intended as “the whip hit me”), or *càidāo pāi-le zhēnbǎn ‘chopper smack-pfv chopping board’ (intended as “the chopper smacked the chopping board”), yet the subject of V-zài is interpretable as these inanimate entities. These examples show that the subject of V-zài has no simple correspondence with the arguments of V, as is also the case for the examples of pre-verbal internal location zài phrases in (25) and (26).

This variability of argument realization shown by V-zài structures evokes earlier discussions of non-canonical argument realization phenomena in simple transitive sentences in Mandarin, the topic of such works as Ren (2000); Zhang (2004) in the Chinese linguistics literature, and Lin (2001) in the generative tradition. Mandarin allows flexible argument realization patterns as demonstrated in (67) and (68).

| wǒ | hē | chá |

| 1sg | drink | tea |

| ‘I drink tea.’ | ||

| wǒ | hē | dàbēi | |

| 1sg | drink | big | cup |

| ‘I drink with the big cup.’ | |||

| wǒ | chı̄ | miàn |

| 1sg | eat | noodles |

| ‘I eat noodles.’ | ||

| tā-men | chı̄ | cānguǎn |

| 3sg-pl | eat | restaurant |

| ‘They are eating restaurant food.’ | ||

The (a) sentences in (67) and (68) show transitive verbs with what tend to be considered canonical patient objects. The (b) sentences show somewhat surprising object nominals: in (67b), the object is interpreted as an instrument, while in (68b), it corresponds to a location.[16]

Huang et al. (2009: 66–75) sketch an analysis of related facts that take the verb in question to be a root, which bears no specific argument structure. Huang et al. (2009) assume that verbs in Mandarin may enter syntax either as a root or as an item fully specified with syntactic argument structure information.[17] Following their proposal, I assume that the V-zài structure also demonstrates an instance in which the verb corresponds to the root. This assumption allows us an operational understanding of the verb’s lack of specific argument structural properties here.[18]

In addition, the V-zài structure should be understood as a compound. This point is supported by the perfective marker -le being attached to zài rather than intervening between verb and zài, as shown in (69) and (70), as noted by various earlier authors (Li 1990: 59–60; McCawley 1992; Peck and Lin 2019). This provides support for the compound status of V-zài.

| Sàmǎlánqí | qı̄nzì | bǎ | zhè | méi | jı̄n | pái | guà-zài-le |

| Samaranch | personally | ba | this | clf | gold | medal | hang-be.at-pfv |

| Xǔ | Hǎifēng | xiōng-qián | |||||

| na | me | chest-front | |||||

| ‘Samaranch personally hung the gold medal on Xu Haifeng’s chest.’ (CCL: Yang, L. Yáng Lán Fǎngtánlù) | |||||||

| bǐ | diào-zài-le | gǎozhǐ-shang |

| pen | drop-be.at-pfv | writing.paper-upon |

| ‘The pen dropped onto the writing paper.’ (CCL: Lu, Y. Zǎochen cóng zhǒngwǔ kāishǐ) | ||

The compound assumption also receives support from examples such as (71), in which the two instances of V-zài are clearly used as parallel items, with the second instance as a proposed replacement for the first.

| tǐyàn | zài | lù-shang | de | gǎnjué, | érqiě | shì | zǒu | zài, |

| experience | be.at | road-upon | assoc | feel | moreover | be | walk | be.at |

| bù, | shì | qíxíng | zài | Chuān-Zàng | xiàn-shang | |||

| no | be | ride | be.at | Sichuan-Tibet | line-upon | |||

| ‘Experience the feeling of being on the road, what’s more, of walking, no, riding on the Sichuan-Tibet route.’ (Wechat c. 2010) | ||||||||

Providing further evidence for the compounding analysis, V-zài may express metaphorical “locative” relations that cannot be expressed via pre-verbal (73) or complement zài (74), as also observed in Liu (2009).

| Jiǎng Jièshí | de | shéntài | jǔzhǐ | …lǎo | tàitai | kàn-zài | yǎn-lǐ |

| name | assoc | expression | movement | old | lady | look-be.at | eye-within |

| ‘Chiang Kai-shek’s behaviour was observed by the old lady’ ( lit. ‘seen in her eyes’) (CCL: Wu, J. and Zhu, X. Jiǎngshì jiāzú quánzhuàn). | |||||||

| *zài | yǎn-lǐ | kàn(-zhe) |

| be.at | eye-within | see-prog |

| *lǎo | tàitai | kàn-le | yìxiē | shì | zài | yǎn-lǐ | |

| old | lady | look-pfv | one | pl | matter | be.at | eye-within |

| Intended: ‘The old lady observed some matters.’ | |||||||

The greater flexibility of V-zài interpretations relative to pre-verbal zài suggests that these two structures are qualitatively different. Indeed, I will argue in Section 6 that V-zài forms a complex predicate, which would be highly consistent with a compounding analysis. The asymmetry demonstrated above thus again supports the notion that at least certain cases of V-zài should be considered a compound structure, although it is not impossible that some instances of V-zài could be analysed as a verb followed by a prepositional phrase.

I assume that the V-zài configuration is also encoded within the VP, as shown in (75), with the zài phrase originating as a post-verbal PP. In this case, however, the PP is not restricted to a goal or result interpretation, but is interpreted as rhematic material in the sense of Ramchand (2008: 46–56). As indicated in (75), the verb here is assumed to correspond to a root. The structure may be productively reanalysed “on the fly” to (as opposed to being lexicalized as) a compound verb structure, as in (76).

The compounding “on the fly” assumption accommodates the different behaviour of V-zài compounds from lexical compounds.[19] V-zài does not occur easily in “V-not-V” structures that describe a set of alternatives in the context. As (77) shows, zǒu-(zài) bù zǒu zài (‘walk-be.at neg walk-be.at’ i.e., ‘walk at or not’) is quite infelicitous. The preferred form is zǒu bù zǒu zài (‘walk neg walk-be.at’ i.e., ‘walk at or not’). In contrast, true lexical compounds such as fāxiàn ‘discover’ and jiějué ‘resolve’ allow either their first morpheme or the compound itself before the negative in the V-not-V structure (78).

| zǒngcái | zǒu | (??zài) | bù | zǒu | zài | qiánmiàn | dōu | měi | guānxi |

| CEO | walk | be.at | neg | walk | be.at | front | all | neg | matter |

| ‘It does not matter whether the CEO walks in front or not.’ | |||||||||

| wènti | dōu | zài | shēnghuó-zhōng, | jiù | kàn | fā(xiàn) | bù |

| problem | all | be.at | life-centre | just | see | discover | neg |

| fāxiàn, | jiě(jué) | bù | jiějué | ||||

| discover | resolve | neg | resolve | ||||

| ‘Problems are there in our lives, it just depends on whether we discover them and whether we resolve them.’ | |||||||

| (http://cpc.people.com.cn/n/2013/0714/c64387-22191692.html, accessed November 25, 2023) | |||||||

Nonetheless, occasional examples of V-zài-not-V-zài can be found online, suggesting that for some speakers, at least, the compound status of V-zài is not in question. As for the example in (77), chǔ bù chǔ zài ‘located neg located be.at’, i.e. ‘located at or not’ is also acceptable.[20]

| zhè | gè | shíhou | yào | kàn | nǐ | de | juésè | chǔ | zài | bù |

| this | cl | time | must | see | 2sg | assoc | role | located | be.at | neg |

| chǔ | zài | dēnglù | zhuàngtài | |||||||

| located | be.at | login | state | |||||||

| ‘At this time, it depends on whether your role is in the logged in status or not.’ | ||||||||||

| (https://zhidao.baidu.com/question/1302432903615744699.html, accessed November 25, 2023) | ||||||||||

The compound structure for V-zài suggests a closer relationship between V and zài in this as opposed to other zài locatives. This will be reflected in the semantic analysis for V-zài in Section 6, where I propose that V and zài form a complex predicate.

I end this discussion with a brief detour into the ba construction, which often provides the context in which the post-verbal distribution of zài is discussed (80). ba requires a transitive verb to occur in the VP to its right, thus an intransitive verb, as in (81), is disallowed. The verb need not, however, be compatible with complement zài: the verb tuı̄ ‘push’, comfortable with ba (82) and in a V-zài structure (63), does not occur with complement zài (64). This suggests the locative in the VP following ba corresponds to V-zài, and thus that any account of the ba sentences below would in any case require an understanding of V-zài.

| Sānmáo | bǎ | shuǐ | fàng | zài | zhuōzi-shàng |

| Sanmao | ba | water | put | be.at | table-upon |

| ‘Sanmao put the water on the table.’ | |||||

| *Sānmáo | bǎ | xuésheng | zuò | zài | dì-shàng |

| Sanmao | ba | student | sit | be.at | floor-upon |

| Intended: ‘Sanmao sat the student on the floor.’ | |||||

| Lǎo Zhāng | bǎ | Wáng | Dé | yòu | tuı̄ | zài | xiǎo | dèng-shang |

| name | ba | name | again | push | be.at | small | stool-upon | |

| ‘Old Zhang pushed Wang De onto the little stool again.’ (CCL: Lao She, Lǎo Zhāng de zhéxué) | ||||||||

The syntax of the ba construction presents complications, however, and an integration with the V-zài structure would take us too far afield. I thus set aside occurrences of V-zài in the ba construction in the rest of the discussion.

4.3 Taking stock: external and internal locatives

Having established the dual nature of both pre-verbal and post-verbal positions for zài, this seems an appropriate moment to review the notion of “internal location” in the Mandarin clause. A noteworthy point emerging from the preceding description is that internal locatives are distinct from external or event locatives both conceptually and structurally, not only in their occupying two distinct pre-verbal positions, but also in their being found post-verbally, in V-zài position. In addition, locative arguments selected by the verb are not restricted to complement position, they also occur felicitously in those positions that accept internal locatives: the lower pre-verbal position and V-zài position. This suggests the notion of internal locatives can be broadened to include argument locations as a special class. Structurally, then, vP (or its equivalent) marks the boundary between external and internal location: anything at or below vP is “internal” to the event described by the VP (83a). Anything above vP is external to the event. Finally, and perhaps not surprisingly, the complement of VP is reserved for argument locatives (83b).

| [ …zàiP ext [ vP zàiP int/arg [ VP V-zài int/arg ]]] |

| [ VP V DP zàiP arg ] |

This conclusion raises questions about the distinction between the pre- and post-verbal non-argument internal locative positions. Observationally, the main contrast between these is that with manner of motion verbs, goal readings are possible only in V-zài position and not in pre-verbal internal locative position. The following discussion will attempt to convey this contrast in terms of how the locative components integrate into the clause. Pre-verbal internal locatives are clearly adjuncts, since, as discussed in Section 3.4, they may be repeated. In Section 6, I will argue that internal locatives in V-zài position are part of a complex predicate formed with V. Before that, it is first necessary to consider how internal location interpretations arise.

5 The interpretation of internal locatives

This section begins the second part of the paper, which is concerned with the semantic interpretation of internal locatives in their different positions. The analysis adopts the approach of semantic underspecification with conceptual enrichment proposed in Maienborn (2000, 2001, 2003). Maienborn argues for an underspecified semantic representation for internal locative modifiers that is resolved at the level of conceptual structure, given that our understanding of each internal locative is based on encyclopaedic knowledge of the event described by the co-occurring verb. As discussed in Section 3.2, internal locatives in Mandarin show the same kind of interpretational indeterminacy that is suited to an appeal to conceptual factors. I apply Maienborn’s analysis to the Mandarin data, begining with stative internal locatives, which are analogous to those described in Maienborn’s description of internal location in German, and then extend the analysis to goal readings for zài in pre-verbal position.

5.1 An underspecified semantics for internal locatives

This subsection briefly illustrates the underspecification analysis developed in Maienborn (2000, 2001, 2003), laying the groundwork for the semantic analysis of Mandarin internal locatives below. Maienborn’s analysis of internal locatives relies on three major components: first, an explicit conceptual component associated with a semantic representation for a sentence; second, an underspecified semantics in which the internal locative relation holds over a free variable; third, an assumption of abductive principles to model the appeal to encyclopaedic knowledge in interpreting internal locative relations.

The underspecified semantics for internal locatives introduces a free variable into the related event representation: v in the modification template in (84) (a variant of MOD in (22)). The specification Q(vx) is a notational convention indicating that “v is assigned a value such that Q(v) is anchored w.r.t. the conceptual structure accessible through x” (Maienborn 2001: 220).

| MOD′: λQλP …λx [P(…)(x) & Q(vx)] |

A brief illustration is provided using the sentence in (85). Its semantic representation, or Semantic Form, is composed by combining the semantic form of the PP (85a) and the verb (85b) via the MOD′ template for transitive verbs (85c), based on the more general template in (84), yielding the representation in (85d).

| Angela | hat | die | Diamenten | in | einem | Kinderwagen | geschumuggelt |

| Angela | has | the | diamonds | in | a | baby-carriage | smuggled. |

| [PP in einem Kinderwagen]: λx ∃z [loc(x, in(z)) & baby-carriage(z)] |

| [v schmuggel-]: λy λe [ smuggle(e) & theme(e, y)] |

| MOD′: λQλPλyλe [P(y)(e) & Q(ve)] |

| [v [PP in einem Kinderwagen] schmuggel-]: |

| λy λe ∃z [smuggle(e) & theme(e, y) & loc(v e , in(z) & baby-carriage(z)] |

| (Maienborn 2001: 220) |

The representation in (85d) describes the set of individuals y and events e such that e is an event of y being smuggled, and e also includes some underspecified item that is in a baby carriage, represented by the free variable v. This free variable is required by MOD′ to be interpreted on the basis of our world knowledge of e, i.e., the smuggling event described.

The relevant knowledge includes, for instance, the understanding that smuggling events are events of transport (86a), and events of transport involve the transported item being supported in a vehicle (86b). (The function τ applied to an event e yields the temporal extension of e.)

| Conceptual knowledge about smuggling events: |

| ∀e [smuggle(e) → transport(e)] |

| ∀ex [transport(e) & theme(e, x) → ∃y [ vehicle(y) & instr(e, y) & support(y, x) at τ(e)]] |

| (Maienborn 2001: 221 (69)) |

Also relevant is the understanding that baby carriages can serve as vehicles (87a), as can, say ships (87b) and other things too numerous to be listed.

| Conceptual knowledge about vehicles: |

| ∀x[baby-carriage(x) → vehicle(x)] |

| ∀x [ship(x) → vehicle(x)] |

| (Maienborn 2001: 221 (70)) |

Maienborn further includes the knowledge that if some object x is located in the inner region of an object y, then y supports x, as listed in (88).

| Conceptual knowledge about spatial and functional relations: |

| ∀xy [loc(x, on(y)) → support(y, x)] |

| ∀xy [loc(x, in(y)) → contain(y, x)] |

| ∀xy [contain(x, y) → support(x, y)] |

| (Maienborn 2001: 221 (71)) |

Based on this kind of world knowledge, we can arrive at a suitable interpretation of the sentence in (85), repeated below in (89). The semantic representation of the example sentence, given in (89a) receives the appropriate conceptual interpretation in (89b).

| Angela | hat | die | Diamenten | in | einem | Kinderwagen | geschumuggelt |

| Angela | has | the | diamonds | in | a | baby-carriage | smuggled. |

| Semantic Form: ∃e∃y [smuggle(e) & agent(e, angela) & theme(e, the diamonds) & loc(ve, in(y) & baby-carriage(y)] |

| Conceptual Structure: ∃e∃y [smuggle(e) & agent(e, angela) & theme(e, the diamonds) & instr(e, y) & loc(the diamonds, in(y)) at τ(e) & baby-carriage(y)] |

| (Maienborn 2001: 222) |

5.2 The semantics of internal locatives in Mandarin

Given the discussion in Section 3.2, it is reasonable to adopt Maienborn’s analysis of internal locatives to the interpretation of internal locatives in Mandarin. For the relevant part of the sentence in (90) (repeated from (24)) given in (90a), MOD′ gives us the semantic representation in (90b).

| nǎinai | …zài | lú-huǒ-gài-shang | kǎo | báishǔgān |

| grandmother | be.at | stove-fire-lid-upon | roast | dried.sweet.potato |

| ‘Grandmother roasted preserved sweet potato on the stovelid.’ (BCC: People’s Daily 1962) | ||||

| zài lú-huǒ-gài-shang kǎo báishǔgān ‘roast dried sweet potato on the stovelid’ |

| λx λe ∃y [roast(e) & agent(e, x) & theme(e, y) & preserved sweet potato(y) & loc(v e , top.of(the stovelid))] |

The representation in (90b) indicates the set of individuals x and events e such that e is an event of x roasting sweet potato preserves, and in which there is some entity located on the stove lid anchored through the conceptual structure associated with the roasting event. The interpretation of (90b) draws on world knowledge about roasting events, e.g., they are events of heating (91a), which involve a heat source instrument (91b) to which the theme must be in some proximal relation during the temporal extension of the event.

| Conceptual knowledge about roasting events: |

| ∀e [roast(e) → heat(e)] |

| ∀ex [heat(e) & theme(e, x) → ∃z [ heat source(z) & instr(e, z) & proximal to(z, x) at τ(e)]] |

It would also be necessary to draw on our understanding of heating instruments such as stoves and fires (92), as well as our understanding that being on the top or the interior of some item is also to be proximal to it (93).

| Conceptual knowledge about heating instruments: |

| ∀x [stove(x) & lit(x) → heat source(x)] |

| ∀x [fire(x) → heat source(x)] |

| ∀xy [stove(x) & lit(x) & lid of(x, y) → heat source(y)] |

| Conceptual knowledge about spatial relations: |

| ∀xy [be.at(x, top.of(y)) → proximal to(x, y)] |

| ∀xy [be.at(x, interior.of(y)) → proximal to(x, y)] |

With conceptual knowledge of this sort, we can derive from the semantic representation for (90) given in (94a), to yield the interpretation in (94b).

| nǎinai | zài | lú-huǒ-gài-shang | kǎo | báishǔgān |

| grandmother | be.at | stove-fire-lid-upon | roast | dried.sweet.potato |

| ‘Grandmother roasted preserved sweet potato on the stovelid.’ (BCC: People’s Daily 1962) | ||||

| Semantic Form: ∃e∃y [roast(e) & agent(e, grandmother) & theme(e, y) & preserved sweet potato(y) & be.at(v e , top(the stovelid))] |

| Conceptual Structure: ∃e∃y [roast(e) & agent(e, grandmother) & theme(e, y) & preserved sweet potato(y) & instr(e, the stovelid) & loc(y, top(the stovelid)) at τ(e)] |

This kind of appeal to world knowledge and conceptual factors allows us to accommodate the different interpretational possibilities of internal locatives as they occur with different verbs.

5.3 Goal interpretations in pre-verbal position

As noted earlier, pre-verbal zài may also show goal readings with verbs that select a goal argument, as illustrated by examples such as (95) (= (34)).

| tāmen | zài | lú-qián | bǎi-le | yì | zhāng | xiǎo | zhuō | |

| 3-pl | be.at | stove-front | place-pfv | one | clf | small | table | |

| ‘They placed a small table in front of the stove.’ (CCL: People’s Daily 1988) | goal | |||||||

Under the current hypothesis that pre-verbal zài is a modifier position (in this instance, the internal modifier position, see Section 3.4), this possibility is somewhat surprising. I assume that in such cases, the zài phrase remains a modifier and is integrated in the same way described above. The goal interpretation being entailed by verb meaning, however, the locative modifier is simply identified as instantiating the goal argument.

Building on the lexical semantics of put-type verbs as discussed above in (51), I assume that bǎi ‘place’ in (95) enters the syntax with its goal component intact, via an existentially bound spatial region (type r) participant (96a).[21] This (two-place) verb combines with the meaning of its object yì zhāng xiǎo zhūo ‘a small table’ to yield (96b) – the set of events in which there is some place at which “they” place a (small) table (setting aside unrelated details). The internal locative modifier phrase is incorporated per the now-familiar MODv template, adding a locative relation with a free variable v, anchored via the placing event, as shown by the underlined portion in (96c).

| Two place bǎi ‘place’: λy λx λe ∃e1 ∃e2 ∃x ∃r [Se(e1 ⊔ e2) & place(e1) & agent(e1, x) & theme(e1, y) & loc(x, r)(e2) & cul(e1) = e2] |

| [ vP tāmen bǎi yì zhāng (xiǎo) zhūo] ‘they place a (small) table’: λe ∃e1 ∃e2 ∃x ∃r [Se(e1 ⊔ e2) & place(e1) & agent(e1, they) & theme(e1, x) & table(x) & loc(x, r)(e2) & cul(e1) = e2] |

| [ vP zài lúqián [ vP tāmen bǎi yì zhāng xiǎo zhūo]] ‘they place a (small) table in front of the stove’: λe ∃e1 ∃e2 ∃x ∃r [Se(e1 ⊔ e2) & place(e1) & agent(e1, they) & theme(e1, x) & table(x) & loc(x, r)(e2) & cul(e1) = e2 & loc ( ve, front (the stove))] |

Adding the locative modifier yields two locative specifications, each with some relatively underspecified content. In the lexically given locative predicate, the identity of the ground component is subject to contextual interpretation. In the modifier locative, the identity of the theme is underspecified. I assume some kind of economy principle in interpreting sentences involving compatible underspecified elements to the effect in (97). For the Semantic Form of (95) in (98a), then, this yields the conceptual interpretation in (98b).

| Interpretational Economy: Unify compatible components in Semantic Form to the maximum specificity. |

| Semantic Form: ∃e ∃e1 ∃e2 ∃x ∃r [Se(e1 ⊔ e2) & place(e1) & agent(e1, they) & theme(e1, x) & table(x) & loc(x, r)(e2) & cul(e1) =

|

| Conceptual Structure: ∃e ∃e1 ∃e2 ∃x ∃r [Se(e1 ⊔ e2) & place(e1) & agent(e1, they) & theme(e1, x) & table(x) & loc(x, front(the stove))(e2) & cul(e1) = e2] |

This seems a somewhat roundabout account for a structure that could potentially be treated as PP preposing. I would argue that this approach is preferable to a preposing analysis, however, for two reasons. First, as will be shown in the next section, not all goal readings of post-verbal zài are preserved in pre-verbal position. Only those that are entailed or strongly implicated by verb meaning, e.g., verbs such as those in Section 4.1 that allow complement locatives, will allow pre-verbal locatives to express goal. A preposing analysis would have to provide a separate account preventing goal readings with zài following a manner of motion verb from also becoming available in pre-verbal position. Second, the current approach allows for a more consistent analysis of the structural positions of locatives. Pre-verbal position continues to be treated as a modifier position, and the pre-verbal locative combines with the rest of the clause in a consistent way regardless of verb meaning.

5.4 Going further: goal interpretations for zài with verbs of directed motion