Abstract

Of similative origin, Polish jakoby derives from the connective jako ‘how, that’ univerbated with the irrealis enclitic by. From the earliest attested stages (late 14th century) into the 17th century, jakoby was used as a comparison marker and as a subordinator of manner or purpose clauses. The former use has persisted, and the latter was ousted. After the 16th century jakoby further evolved into a reportive marker, as a particle or complementizer. Contrary to what pathways explaining the connection between similative and evidential marking would suggest, jakoby’s now predominant function as a reportive marker was apparently not prepared by inferential use, nor was its complementizer function mediated by a purpose function. Instead, purpose and reportive complementizers belong to different “branches”, both of which can be motivated by an indiscriminate similative-manner function. The evidence in favor of this derives from a systematic evaluation of extant research and a corpus study covering almost the entire period from 1600 to our day. A crucial moment to understanding jakoby’s functional changes is the insight that similatives can acquire propositional scope prior to entering the evidential domain and marking a metonymic relation between speech acts and epistemic attitudes expressed by the former.

1 Introduction

In modern Polish, jakoby is used as a particle or complementizer in contexts of hearsay. As a complementizer it is also frequently employed after verbal or nominal attachment sites (complement-taking predicates, CTPs) that denote the cognitive attitude (opinion, conviction, belief, doubt, etc.) of someone other than the speaker, including claims that are considered facts by some people; see (3).

| Jesteś | jakoby | lekarz-em. |

| be.prs.2sg | rep.ptcl | physician-ins.sg |

| ‘Reportedly, you are a physician.’ | ||

| Mówi-ą | także, | jakoby =m | sprowadzi-ł | na was |

| say[ipfv]-prs.3pl | also | rep.comp=1sg | bring[pfv]-lf-(sg.m) | on 2pl.acc |

| Tatar-ów. | ||||

| tatar-acc.pl | ||||

| ‘They also say that [lit. as though ] I brought the tatars on you.’ | ||||

| (PNC; W. Jabłoński: Uczeń czarnoksiężnika. 2003) | ||||

| Uwierzy-ł | plotk-om, | jakoby | P. |

| believe[pfv]-pst-(sg.m) | gossip-dat.pl | rep.comp | |

| ‘He believed gossip (saying) that P.’ | |||

Jakoby originated from a similative marker (jako ‘how’) univerbalized with the irrealis enclitic by. From the earliest attested stages (late 14th century) into the 17th century, jakoby was used as a comparison marker (similative) and as a subordinator of manner or purpose clauses. The former use has to some extent persisted, while the latter faded out (probably during the 19th century; see Section 4.2.2).

The development of jakoby presents an interesting case because it gives reason to assume that it diverges from earlier proposed pathways in various ways. At first sight, it is tempting to regard jakoby as an example that confirms the functional pathway of similative markers into evidentiality proposed by Gipper (2018); here and below > marks ‘sequence of appearance’, ⊃ ‘implies’:

| (i) similarity (⊃ irreal) > (ii) visual/perceptual evidence > (iii) inference + uncertainty. |

On the basis of data from a limited number of languages, Gipper suggests that this pathway might be crosslinguistically common, but adds the caveat that this assumption must be tested on more languages (2018: 276–277). In fact, on closer inspection, the development of jakoby raises doubts whether Gipper’s pathway is the only one leading from similative to reportive marking. Actually, jakoby seems to have run through more than the pathway in (4) in acquiring a salient reportive function, but it seems as though jakoby “stripped off” functions in (4)’s middle part, while it retained the initial stage. Admittedly, loss of intermediary stages (with the initial one(s) retained) is not by itself a counterargument against some presumed pathway and simply yields a “doughnut category” (Dahl 2000: 10–11; Haspelmath 2003: 236). However, since there is practically no evidence for jakoby as an inferential marker, the acquisition of the now predominant reportive use should better be explained by other mechanisms. Moreover, jakoby’s diachronic changes are at variance with Saxena’s (1995) implicational hierarchy in (5) for various reasons (see Section 4). In fact, they are inverse to generalizations implied by this hierarchy, which was designed for say/thus (‘A < B’ means “A is lower on the hierarchy/appeared earlier than B”, thus “B implies A (but not vice versa)”):

| direct quote marker, complementizer (say < know < believe < want) < purpose, reason < conditional < comparative marker. |

Jakoby also lost its manner and purpose uses, and probably these uses are not part of the same developmental path (see Section 4.2.2.4). Furthermore, jakoby is only scarcely attested in contexts of quotation and after pretense-CTPs, although it has probably functioned as a subordinator since its earliest attestations, including uses as a potential complementizer, i.e., as a conjunction that identifies a clause as an argument of a predicative expression in an adjacent clause (cf. Kehayov and Boye 2016: 1; Wiemer 2021: 43–46).

This article outlines changes in the functional distribution and syntactic behavior of jakoby from Old Polish (14th–15th c.) to the present, in order to substantiate the objections and claims formulated in the preceding paragraphs. I will argue for a pathway that differs from Gipper’s in one crucial point, namely the role of inferential marking, and which, concomitantly, radically differs from Saxena’s. I will first comment on the available data and the state of research (Section 2) before I survey jakoby in modern Polish (Section 3) and then turn to its diachronic development (Section 4). The results will be discussed against the larger backdrop of recent research into the link between similative markers and evidentiality and the concomitant development of complementizers (Section 5). Examples are glossed to the extent necessary for understanding the morphosyntactic structure of the relevant clauses.

2 Data and state of research

The earliest attestations of Polish are from the late 14th century. The Old Polish period covers the 14th century up to about 1540, Middle Polish approximately covers the subsequent time until the late 18th century. Only very small corpora exist for Old Polish, but there are two dictionaries, Słownik Staropolski (SłStar) for the 14th–15th centuries, and Słownik Polszczyzny XVI wieku (SłXVI) for the 16th century, which contain extensive entries based on comparatively large bodies of texts. The reconstruction of jakoby’s way into reportive marking is based on the relevant entries in these dictionaries, on a critical assessment of existing research (Jędrzejowski 2020; Socka 2015; Wiemer 2015; Wiemer and Socka 2022), and on a combination of corpus samples (see Section 4). In addition, for the period inbetween, i.e., from the 17th century to the early 20th century, I investigated samples from the recently launched Electronic Corpus of 17th- and 18th-century Polish texts (up to 1772), abridged KorBa (<Korpus Barokowy), and from two smaller corpora covering the period 1753–1928; a sample of modern Polish was drawn from the PNC (see References). Of course, dictionary data (for the oldest periods, 14th–16th centuries) cannot be used for inferential statistics, and frequency counts have to be treated with caution when it comes to comparing them with corpus-based random samples (employed for the later periods). However, at present, this combination of analyses covering almost all periods of the attested history of Polish provides the best approximation for a reconstruction of the development of jakoby (as of other connectives) with the available resources.

3 Jakoby in contemporary Polish

This section illustrates the modern usage of jakoby as a particle or complementizer. It will be argued that jakoby has a primary reportive use and that evidence for an inferential reading is virtually lacking.

Jakoby is a word, i.e., it is a phonologically independent (non-clitic) lexical unit, used as a particle or complementizer with reportive or (more rarely) similative meaning. In both syntactic functions jakoby conveys epistemic distance, i.e., lack of full epistemic support (Boye 2012), which may range from epistemic agnosticism (see (1), (6)) to downward rejection of the truth of the proposition under jakoby’s scope (see (3)). This feature is induced by the incorporated irrealis enclitic -by, which explains the relation to irrealis functions, as well as why, as a complementizer, jakoby shows restrictions on the form of the finite verb and still serves as prosodic host for person-number clitics (see (2), (15) and Section 4.1). In both particle and complementizer use jakoby exclusively occurs in finite clauses, i.e., with verbs marked for tense and agreement (person/number). It scopes over propositions, that is, over claims (or questions) about situations (= states-of-affairs) that can be checked as being true or false, or which can be modified epistemically by the speaker (or another judging subject; see (10) and Footnotes 4 and 7), since the situation is assigned reference in space and time (Boye 2012: 192–198; Wiemer 2015: 227–228). Jakoby’s use as a similative marker has considerably receded and is being ousted by its cognate jakby. This observation suggests a shift from the domain of perception to the domain of cognition (knowledge and belief), which entails scope over propositional content.

Used as a particle, i.e., a function word with a flexible position that is not part of constituent structure, jakoby occurs with any finite form of the verb and almost never serves as a host of person-number clitics (see Section 4.1); see (6)–(8):

| − | Ale | t-o, | co | jakoby | znaleź-l-i=ście, |

| but | dem-n | what.nom | rep.ptcl | find[pfv]-lf-pl.vir=2pl | |

| jest akurat moje. | |||||

| ‘But what you allegedly found is just mine.’ | |||||

| (PNC; A. Sapkowski: Wieża Jaskółki. 2001) | |||||

| C-i | dw-aj | zdoln-i | młodzieńc-y |

| this-nom.pl.vir | two-nom.vir | capable-nom.pl.vir | young_man-nom.pl.vir |

| siedz-ą | jakoby | do t-ej | por-y, |

| sit[ipfv]-prs.3pl | rep.ptcl | to dem-gen.sg.f | time[f]-gen.sg |

| ‘These two talented young men are allegedly still sitting (in jail).’ | |||

| (PNC; M. Sokołowski: Gady. 2007) | |||

| I znowu czekały, aż ktoś się nimi zainteresuje, | ||||

| wyłuska | ow-e | jakoby | niezwykł-e | |

| shell[pfv]-(fut.3sg) | that-acc.pl | rep.ptcl | unusual-acc.pl | |

| informacj-e. | ||||

| information-acc.pl | ||||

| ‘And again they waited until someone takes an interest in them and extracts this supposedly unusual information.’ | ||||

| (PNC; W. Żukrowski: Za kurtyną mroku. Zabawa w chowanego. 1995) | ||||

(8) furthermore demonstrates that semantic scope does not depend on the constituent to which jakoby adheres in linear sequence: though modifying the adjective niezwykłe ‘unusual’, jakoby implicitly scopes over a proposition that can be paraphrased as owe informacje były niezwykłe ‘those pieces of news were unusual’ (cf. Boye 2012: 183–184; Wiemer 2015: 228–229). As in the other cases adduced, jakoby indicates that this proposition derives from an earlier (somebody else’s) utterance.[1]

Jakoby is thus sensitive to meaning components conveying propositional content of speech. As a complementizer, it predominantly occurs after verbal or nominal CTPs related to speech acts or cognitive attitudes (for figures see Section 4.2.2); see (9)–(13). It also occurs after verbs (or nouns) that do not, at face value, convey a speech-act-related meaning, but which reveal such a layer under specific circumstances. An example is negated wiedzieć ‘know’ in (9). It demonstrates that jakoby, as it were, “activates” a reportive meaning: the clause introduced by jakoby does not convey the headmaster’s lack of knowledge, but that the headmaster claimed to be ignorant of what is the propositional content of its clausal argument (the jakoby-clause). That is, jakoby marks reference to what the headmaster verbally claimed to be ignorant of, and this relates to verbal behavior.[2] Thus, as a complementizer, jakoby cannot by itself introduce a speech-act related meaning, independently of the meaning of a CTP, but it can be used to make salient, or disambiguate, speech-act related meaning whenever the semantics of a CTP is compatible with such a meaning.[3]

| Dokucza jej silne pieczenie w przełyku. Czeka ją gastroskopia. Tymczasem | ||

| dyrektor | gimnazjum | utterance (implied) |

| headmaster-(nom.sg) | gymnasium-(gen.sg) | verbal attachment site |

| nic nie wie, | jakoby | |

| nothing neg know[ipfv]-(prs.3sg) | rep.comp | |

| we wtorek w placówce miało miejsce takie zdarzenie. | ||

| ‘She has a strong burning sensation in her esophagus. A gastroscopy is waiting for her. Meanwhile, the headmaster of the gymnasium does not know anything that such an event took place on Tuesday.’ | ||

| (PNC; Trybuna Śląska, 24.10.2003) | ||

| Lucia | wypiera-ł | się | ||

| pn[m]-(nom.sg) | refute[ipfv]-pst-(sg.m) | rm | utterance | |

| jakoby | spa-ł | z | facet-ami. | verbal attachment site |

| rep.comp | sleep[ipfv]-lf-(sg.m) | with | guy-ins.pl | |

| ‘Lucia denied that he slept with guys.’ | ||||

| (PNC; B. Jędrasik: Gorączka – opowiadania wyuzdane. 2007) | ||||

| Nigdy nie wróciła do Rosji i tylko dziwne | |||

| słuch-y | krąży-ł-y | o | utterance |

| rumor-nom.pl | circulate[ipfv]-pst.nvir-pl.nvir | about | nominal attachment |

| niej, | jakoby | wysz-ł-a za mąż | site |

| 3f.loc | rep.comp | marry[pfv]-lf-sg.f | |

| za hodowcę bawołów z Teksasu. | |||

| ‘She never returned to Russia, and there were only strange rumors that she had married a Texas buffalo breeder.’ | |||

| (PNC; J. Krzysztoń: Wielbłąd na stepie. 1998 [1978]) | |||

| A po wojnie | |||

| [Francj-a] | łatwo | uwierzy-ł-a, | cognitive attitude (belief) |

| France[f]-nom.sg | easily | believe[pfv]-pst-sg.f | verbal attachment site |

| jakoby | by-ł-a | mocarstw-em | |

| rep.comp | be-lf-sg.f | power-ins.sg | |

| zwycięsk-im (…). | |||

| victorious-ins.sg | |||

| ‘And after the war, France easily believed that it was a victorious power.’ | |||

| (PNC; Polityka, 14.02.2004) | |||

| (…) nie | wolno | wyciągną-ć | wniosk-u, | cognitive attitude (conclusion) |

| neg | allowed | draw[pfv]-inf | conclusion-gen | nominal attachment site |

| jakoby | mi | nic | nie | |

| rep.comp | 1sg.dat | nothing | neg | |

| dolega-ł-o. | ||||

| ail[ipfv]-lf-sg.n | ||||

| ‘One must not draw the conclusion that/as though I am fine.’ | ||||

| (PNC; I. Karpowicz: Nowy kwiat cesarza. 2007) | ||||

Importantly, reference to somebody’s cognitive attitude, or a “product” of mental activity (like wniosek ‘conclusion’ in (13)), is metonymically related to its verbalization: speech acts serve as external manifestations of people’s epistemic states (beliefs, convictions, doubts, etc.), however acquired or justified. By using jakoby, speakers refer to verbal utterances either directly or via cognitive attitudes that manifest themselves through respective utterances. These attitudes, or the related speech acts, are “labeled”, whereby the speaker qualifies them in terms of reliability or other properties relevant for epistemic support. This also pertains to alleged facts that people (other than the speaker) subscribe to: any opinion or alleged truth that the speaker refers to had to be uttered in some way or other to give it propositional content, and this content can be denied (see (15)).

| W porównaniu z tym | |||

| propagowani-e | idiotyczn-ego | pogląd-u (…), | jakoby |

| propagating-nom | idiotic-gen.sg | opinion-gen.sg | rep.comp |

| zgodnie z prawami mechaniki | |||

| pszczoł-y | mia-ł-y | by-ć | niezdoln-e |

| bee-nom.pl | aux-lf-pl.nvir | be-inf | incapable-nom.pl.nvir |

| do lot-u, | |||

| to flight-gen | |||

| to już drobiazg. | |||

| ‘In comparison with this, promoting the idiotic view that, according to the laws of mechanics, bees are incapable of flying, is a minor matter.’ | |||

| (PNC; A. Szady: Katastroficzny romans sądowy z życia owadów. 2007) | |||

| Nie | jest | prawd-ą, | jakoby=m |

| neg | be.prs.3sg | truth-ins | rep.comp=1sg |

| w tych tekstach używała wulgaryzmów (…). | |||

| ‘It isn’t true that I used/use vulgarisms in these texts.’ | |||

| (PNC; Polityka, 14.02.2009) | |||

Denial and skepticism against propositions that are either openly expressed or inferred by the speaker are frequent concomitants of jakoby; however, there may be more neutral stances. See, for example, (16), in which the speaker accepts the possibility that the messages (wieści) are true, and this is what raises his/her anxiety:

| Martwią mnie wszelako napływające z Pragi | ||||

| wieśc-i, | jakoby | książ-ę | Henryk | trwoni-ł |

| news-nom.pl | rep.comp | prince[m]-nom.sg | pn-(nom) | waste[ipfv]-lf-(sg.m) |

| czas | ||||

| time-(acc) | ||||

| na płochych rozrywkach, podobnie jak to czynił za młodu jego bezbożny stryj, Bolesław Rogatka. | ||||

| ‘However, I am concerned about the news from Prague that Prince Henry was wasting his time on frivolous amusements, just as his godless uncle, Bolesław Rogatka, did in his youth.’ | ||||

| (PNC; W. Jabłoński: Metamorfozy. 2004) | ||||

Thus, in case jakoby does not refer directly to (previously uttered) speech acts or their products (see (2), (3), (10), (11), (16)), it serves to ascribe cognitive attitudes (a.k.a. epistemic states) to other people (see (12)–(15)); in either case jakoby scopes over propositional content. That is, jakoby indicates that the speaker makes a claim about other people’s epistemic attitudes on the basis of their real or imagined utterances; I know of hardly any examples in which the speaker interprets just behavior, and in diachronic corpora, such examples are likewise exceptional (see Section 4). Crucially, jakoby does not point at any process or trigger of inference, as do inferential markers; instead, it scopes over the propositional “spell-out” either directly of hearsay or of attitudes or “products” of cognitive processes, which the speaker labels in such and such a way, and these labels are supplied by suitable CTPs. As a complementizer, jakoby connects a clause with the relevant propositional content to a higher-order predicate (CTP) which either directly relates to representative speech acts (i.e., assertions) or whose meaning potential includes a layer from which reference to representative speech acts can easily be activated. In this sense, jakoby and “its” CTP are in semantic concord: they share their evidential background of judgment, namely a verbal (communicative) one; but this concord concerns only the label, and the content of the judgment is specified (by the complement clause), while there is no connection with a possible trigger or justification of that judgment.

Consequently, even if jakoby does not refer directly to a speech act (“labeled” by the attachment site of jakoby), it is not used as an inferential marker in the sense employed in evidentiality research (Aikhenvald 2004; Speas 2018; Squartini 2008, among many others). According to the latter, inferential markers indicate that a proposition is based on inference, or more precisely: that the speaker makes a judgment about a situation (= SoA) S and that there is a more particular source of evidence which gives support for this judgment (i.e., that proposition p holds for S).[4] S may be any situation and, as a rule, it does not refer to a speech event or assign a cognitive attitude to other people. The triggers (or backgrounds) of the inference vary, and usually the types of background provide the basis of classifications of inferential markers, which distinguish between perceptual triggers (or circumstantial knowledge) and encyclopedic knowledge (including knowledge about habits); to this we should add inferences triggered by hearsay.[5] Diachronic pathways like Gipper’s are based on these assumptions so that an inferential stage is understood as a “mediator” between similative and reportive meaning.

However, Pol. jakoby does not target any such inference or its trigger (as either complementizer or particle): whatever the proposition (p) in jakoby’s scope tells us, it simply spells out other people’s assertions or, alternatively, mental states or products of intellectual activity that can be manifested by assertions. CTPs of jakoby label these assertions or related cognitive states, and jakoby “links” these labels to specific propositional content, but it does not point at, or specify, any process of inference or its triggers. In other words: the judgment modified by jakoby does not result from a speaker’s inference based on perceptual data or from their general knowledge background. Jakoby simply scopes over the content of speech or a related attitude of knowledge or belief, which the speaker assigns to another person. How this attitude was acquired, or why it was uttered, is irrelevant, but the speaker may distance themselves from the assertions of others and the stances behind them.

This makes jakoby differ also from what we normally observe in cases when inferences are based on hearsay, as in the following examples from English (17) and Spanish (18):

| (…) and while many say that it has looked to be that way for most of this year, it seems that for a couple of days, IBM really will be leaderless, because John Akers says he will resign at today’s board meeting, and Gerstner is not due to take up his posts until Thursday. |

| (BNC; from Marín-Arrese et al. 2022: 60) |

| A | juzgar | por | sus | declaraciones | parece | que |

| to | judge.inf | by | his | declarations | seem.prs.3sg | comp |

| Obama (…) está dispuesto a gobernar desde el estricto respeto a la Constitución, las leyes y los derechos ciudadanos … | ||||||

| ‘Judging by his declarations, it seems that Obama (…) is ready to govern with a strict respect for the Constitution, the law and civil rights …’ | ||||||

| (from Marín-Arrese and Carretero 2022: 244) | ||||||

The conclusion (‘for a couple of days, IBM will be leaderless’) is based on a verbal announcement (‘John Akers says p’), but this conclusion is drawn by the author of (17), not by those referred to in this stretch of discourse.[6] The author of (17) does not ascribe a cognitive attitude, or conclusion, to those referents mentioned in the discourse, but this is exactly what jakoby does (if it does not target speech acts directly). The case appears a bit more complicated in (18): on the basis of what Obama declared, the author of (18) concludes that Obama is ready to obey laws and civil rights and that this disposition will manifest itself in his conduct. Thus, one may ask whether the speaker’s assumption relates to Obama’s attitude or rather to his expectable behavior. Of course, these two interpretations are intimately connected (and may be variably fore- and backgrounded), either interpretation is compatible with parece que ‘(it) seems that’, and either interpretation amounts to inferential use. This differs for Pol. jakoby, which only ascribes attitudes to people, with the presupposition that they uttered something, or behaved in a particular way.

Table 1 summarizes these insights. Report-based inferential markers highlight the content of an inference (drawn by the speaker), with the triggering hearsay in the background, and the inference may relate to any kind of situation (not necessarily to another person’s cognitive attitude); see (17) and [1]. By contrast, jakoby either targets the propositional content of speech act(s) as such (thus behaves like a typical reportive marker; see [2b]), or it only assigns a cognitive attitude (or a conclusion, as the result of an intellectual process) to somebody else. In this case, there is a metonymic relation between speech act and cognitive attitude: the latter presupposes the former (attitude → speech act); see [2a]. Report-based inferentials are based on a metonymic relation as well, but this relation is better characterized as an implicature, and, above all, this implicature works in the opposite direction (speech act ⊃ inference about SoA (= p)), and the inferred p can relate to any SoA (knowledge background).

Relations between propositional content of speech acts and cognitive attitudes.

| [1] | Report-based inferences: (propositional content of) utterances ⊃ inference about S | |||

| TRIGGER (background) speech act(s) | ⊃ ASSERTION (foreground) inference concerning S | |||

| Ex. (17) | Knowledge background: ‘John Akers: “I will resign at today’s board meeting”’ | ‘For a couple of days, IBM will be leaderless’ = p | ||

| Propositional modifier: it seems (that) [p] | ||||

| [2a] | claims about other people’s cognitive attitudes (incl. “products” of mental operations) | |||

| BACKGROUND (presupposed) | → | ASSERTION (foreground): speaker’s qualification of cognitive attitude assigned to other people | ||

| Ex. (12) | ‘Prominent representatives of France have said something [or behaved in some way] concerning France’s role in and after the war’ | ‘After the war, (prominent representatives of) France believed that it was a victorious power.’ | ||

| Propositional modifier: jakoby [p] | ||||

| [2b] | reference to (propositional content of) utterance(s) | |||

| ASSERTION | ||||

| Ex. (10) | ― (No inference required) | ‘Somebody said: “Lucia sleeps/slept with guys”’ (and Lucia himself denies this)a | ||

| Propositional modifier: jakoby [p] | ||||

-

aNotably, this is a case in which the judging subject, relevant for the employment of jakoby, is not the speaker, but the subject of the superordinate clause (= Lucia).

4 Tracing jakoby’s diachronic development

In Section 4.1, I start with an account of the origin and early history of jakoby based on extant research (mentioned in Section 2) and then present a corpus-based study covering the subsequent time from 1600 to our days almost without gaps (Section 4.2). In Section 4.3 I will provide the arguments in favor of an immediate diachronic link between similative and reportive use.

4.1 Characteristics of jakoby in Old and Middle Polish

As a word unit, jakoby consists of the connective (and interrogative) jako and the irrealis marker by. Since the earliest Old Polish attestations jako was a highly flexible unit, both in syntactic and in semantic terms. From a semantic point of view, comparison (similative) and manner were prominent at the earliest stages. The diachronic relation between comparison and manner function (manner > comparison or comparison > manner, or both from an indiscriminate meaning?) has remained unclear;[7] however, in manner use jako is compatible with purpose, from which it cannot be clearly discerned in many discourse tokens of earlier Polish (see below). Apart from that, jako served as a complementizer (see the relevant entries in SłStar i SłXVI). In the latter function, jako died out, and in general, jako has been ousted by its cognate jak in practically all usage types,[8] including the combination with by to mark comparison (see (19)–(21)). The details of these latter processes are an open issue and cannot be addressed here.

In turn, by originally was the 3sg-aorist form of byti ‘be’. In combination with the anteriority l-participle it marked a pluperfect. The aorist died out very early (only limited attestations in Old Polish), but the paradigmatically isolated form by survived as a 2P-enclitic (“Wackernagel clitic”); among its “favorite” hosts were clause-initial connectives like jako. However, =by could also attach to the l-participle, particularly after =by ceased to strictly abide by the 2P-rule. In any case, =by kept requiring the l-participle even after the latter turned into a general past marker (= l-form) and regardless of =by’s position and prosodic host.[9] Alternatively =by could go with the infinitive, but attached to jako this option was restricted to manner and purpose (see below).

The combination =by + l-form (or infinitive) eventually turned into a discontinuous subjunctive marker;[10] with the l-form, person-number enclitics always attached to =by yielding clusters like X=by=ś.2sg, X=by=śmy.1pl. Both requirements have persisted into contemporary Polish both in the “ordinary” subjunctive and for connectives with a final element -by, provided these function as subordinators (of adverbial or complement clauses); the full version of the PNC (1.8 bln segments) returns only 16 cases in which jakoby as a complementizer does not attract person-number clitics. The picture is diametrically opposed for jakoby as a particle (i.e., a function word with loose or no syntactic integration), for which queries in the full version of the PNC yield only 14 items with attached person-number clitics. Therefore, the remarkable point is that, in subordinator function, -by has remained this attractor, even though it can no longer be separated from jako and nothing can intervene (jako|by).

In sum, jakoby results from a morphologization process that has come close to morphological opacity, but the original collocation requirements of -by with the clausal predicate have remained and thereby turned into a semantically vacuous rule: the l-form only marks finiteness, but no tense; it can be characterized as a ‘morphone’, i.e., a property of word forms that bears no effect on syntax or semantic interpretation (Aronoff 1994). I gloss it lf.

Figure 1 summarizes this development. Steps (i)–(iii) present the rise of a new function word, whereas step (iv) indicates the split into complementizer versus particle. The latter process was accompanied by the retention of the l-form requirement and -by’s function as host for verbal agreement markers (→ complementizer) versus the loss of these properties (→ particle), and as a complementizer, jakoby always occurs clause-initially and typically right after its CTP. The chronological relation between steps (iii) and (iv) is another open issue that I will not tackle here.

Jakoby’s morphosyntactic history in a nutshell.

Furthermore, jakoby (at different stages of its morphologization) through Old and Middle Polish was a highly flexible similative marker, as it could scope over constituents of practically any format, e.g., NP-internal modifiers (19) or participial adjuncts (20):[11]

| Okrvg yey oczy okolo zrzyenycze, | ||

| yakoby | [drogy-ego | yaczynct-a] |

| sim | precious-gen.sg | yakcynth-gen.sg |

| ‘a circle around her eyes at the pupil, like [a precious hyacynth]’ | ||

| (SłStar; Rozmyślanie o żywocie Pana Jezusa, ∼1500) | ||

| Sobota duchovna … rzeczona yest vtora pyrwa (…), | ||||

| jakoby | [vczynyon-a | ze | wtor-ey | pyrwa] |

| sim | made-nom.sg.f | from | second-gen.sg.f | pirva |

| ‘The spiritual Saturday (= sabbath?) is called the second first …, as if [it had been made first from second]’ (i.e., ‘… as if it had been made first Saturday from the second one’) | ||||

| (SlStar; Rozmyślanie …, ∼1500) | ||||

Importantly, examples in which jakoby took scope over propositions, as in (21), are easy to spot, for instance when jakoby introduced a finite clause to compare some assumed state with another, hypothetical one.

| Ach myloscz, czosz my vczinyla, eszesz me tak oslepila (…), | |||

| yakoby =ch | [nyk-ogo | na swecz-e | zna-l]. |

| sim=1sg | nobody-gen | on earth-loc | know[ipfv]-lf-(sg.m) |

| ‘Oh love, what have you done to me, you have blinded me (…) as if [I didn’t/wouldn’t know anybody (else) on earth].’ | |||

| (SłStar; Piśmiennictwo polskie …, 1408) | |||

Note that in similative use (and uses related to perception) jakoby can still be analyzed transparently as jako=by, with =by marking the subjunctive together with the l-form. Regardless of this, jakoby could take propositional scope if it syntactically modified units below clause level (see Section 3). Relevant examples can be found already in the earliest period; compare (22) with (8):

| Kaza-l-y | zvyąza-cz | myl-ego | Iesus-a | povroz-my | |

| order[pfv]-pst-pl | bind[pfv]-inf | dear-acc.sg.m | Jesus-acc.sg | tie-ins.pl | |

| (…) | yakoby | [zlodzyey-a]. | |||

| sim | criminal[m]-acc.sg | ||||

| ‘They ordered to bind dear Jesus with ties, | |||||

| (i) like [a criminal]. | |||||

| (ii) as if (he were) [a criminal].’ | |||||

| (SłStar; Rozmyślanie …, ∼1500) | |||||

Here zlodzyey-a agrees with the object NP myl-ego Iesus-a. This might be taken as a simple comparison of Jesus with a criminal (see (i)), but, possibly supported by the syntactic parallelism, the component -by favors a hypothetical statement (see (ii)), i.e., a suspended proposition: the proposition conveyed by the clause cannot be “checked”, because it lacks referential anchorage. Concomitantly, the original interpretation as a transparent combination of jako + irrealis clitic =by is weakened, since there is no verb (l-form) otherwise required by this clitic. For the same reason loss of transparency is inherent also with “objects” on subclausal levels (see (19)).

Other prominent uses were manner (23)–(24) and purpose, which sometimes interfered with a consecutive meaning (25). In manner function, jakoby introduced embedded WH-interrogatives (see 23).

| Nye | vye-m, | y<a>ko.by =[chmy | y | mog-l-y | zatay-cz]. |

| neg | know[ipfv]-prs.1sg | how.irr =1pl | 3sg.m.acc | can-lf-pl | hide[pfv]-inf |

| ‘I don’t know how [we may hide him].’ | |||||

| (SłStar; Rozmyślanie …, ∼1500) | |||||

| A then Walthko, raczsza …, s Greglavem | |||||

| scha | radzy-l-y, | yako.by | [gy | zaby-cz | mye-l-y]. |

| rm | counsel[ipfv]-pst-pl | how.irr | 3sg.m.acc | kill[pfv]-inf | aux-lf-pl |

| ‘And this Waldko, the advisor …, counseled with Greglav (as to) how [they should kill him].’ | |||||

| (SłStar; Wiesz o zabiciu Andrzeja Tęczyńskiego, ∼1470) | |||||

| Stro-g-my | skuthk-y | dobr-e, | ||

| build[ipfv]-imp-1pl | deed-acc.pl | good-acc.pl | ||

| gakobi =[chom | presz | ne | nasz-im | dusz-am |

| CONJ=1PL | through | 3pl.acc | our-dat.pl | soul-dat.pl |

| otrzyma-l-y | sbauen-e]. | |||

| receive[pfv]-lf-pl | redemption-acc | |||

| ‘Let us do good deeds, so that, [through them, we (may) gain redemption for our souls].’ or: ‘… in order [for our souls to gain redemption].’ | ||||

| (SłStar; Kazania Gnieźnieńskie, 14th c.) | ||||

In manner and purpose uses, jakoby also occurred with infinitival predicates, as in (26):[12]

| Do | t-ego=m | záwʃze | by-ł | chętliw-y/ |

| to | dem-gen=1sg | always | be-pst-(sg.m) | anxious-nom.sg.m |

| Iákoby | żywot | wieś-ć | vczćiw-y. | |

| conj | life[m]-(acc-sg) | lead[ipfv]-inf | honorable-acc.sg.m | |

| ‘I always was anxious/to live an honorable life’ (‘… in order to live/as for how to live …’) | ||||

| (SłXVI; Kochanowski, 1579) | ||||

As marker of manner or purpose, jakoby retained its transparent character: jako=[by + l-form/infinitive]. Simultaneously, these uses are associated with volition (intention), and for jakoby both faded out during the 19th century (see Table 5). By contrast, similative uses are more closely associated to cognition, and this favors an expansion into epistemic modality (which entails propositional content). Concomitantly, in similative use jakoby may retain its transparency even with propositional adjuncts (see (21)), but since it could always modify constituents of very different formats and, thus, be used without a verbal predicate, this flexible behavior supported loss of transparency (see (19)–(20)). In addition, it should be emphasized that orthography (joint vs disjoint spelling) cannot be regarded as a reliable indicator of (loss of) morphological transparency (jako=by > jako|by).[13]

SłStar and SłXVI register some more minor functions, but no quotative uses. Moreover, before the 16th century, jakoby only rarely occurred clause-initially in the scope of predicates denoting speech acts and, if it did, these clauses mostly served to mark manner or purpose (cf. Wiemer 2015 for details). Simultaneously, in SłStar I did not find a single example with jakoby as a particle in the context of a speech act verb or any other indicator of reported speech. Similarly, Jędrzejowski (2020), who extracted 262 examples with jakoby from PolDi (see References list), found only two instances in which jakoby could be interpreted as a complementizer after verbs denoting speech acts (see further Section 4.2.2.1).

According to the SłXVI, the situation in the 16th century did not differ much, that is, during the 16th century reportive use of jakoby was still emergent, regardless of the syntactic function (complementizer or particle). Of course, one may question the representativeness of SłXVI (and of SłStar), and, anyway, even extensive dictionary entries do not create a valid ground for inferential statistics. Regardless, the huge amount of examples in SłXVI at least allows us to judge that, as a complementizer, jakoby still frequently occurred in similative function (27), probably not less frequently than as a complementizer after verbs (28) or nouns (29) denoting speech acts. SłXVI also adduces quite many embedded interrogatives with jako ‘how’ in transparent combination with =by (30):

| ia milcżę/ | ||||

| á | cżyni-ę | iákoby =m | nie | widzia-ł. |

| and | act[ipfv]-prs.1sg | sim=1sg | neg | see[ipfv]-lf-(sg.m) |

| ‘I am silent and act as if I haven’t seen anything.’ | ||||

| (SłXVI; Jan Leopolita: Biblia …, 1561) | ||||

| oſkárżył Misboſetá ſyna Saulowego niewinnie/ | ||||

| iákoby | mia-ł | przeciw | krol-owi | mowi-ć. |

| rep.comp | aux-lf-(sg.m) | against | king-dat.sg | speak[ipfv]-inf |

| ‘He accused Saul’s son Misboset unjustifiably that/as if he had spoken against the king.’ | ||||

| (SłXVI; Marcin Bielski: Kronika …, 1564) | ||||

| Gdy | nowin-á, | iákoby | zeiś-ć |

| when | news[f]-nom.sg | rep.comp | depart[pfv]-inf |

| mia-ł | z | świát-á, | przyſz-ł-á (…). |

| aux-lf-(sg.m) | from | world-gen | arrive[pfv]-pst-sg.f |

| ‘When the news that he had passed away arrived (…).’ | |||

| (SłXVI; Piotr Ciekliński: Potroyny z Plauta, 1597) | |||

| Antipater | myſli-ł | iákoby | przez | iad |

| pn[m]-(nom.sg) | think[ipfv]-pst-(sg.m) | rep.comp | through | poison-(acc.sg) |

| mog-ł | zágładzi-ć | Alexandr-á. | ||

| can-lf-(sg.m) | exterminate[pfv]-inf | pn-acc | ||

| ‘Antipater thought how he could exterminate Alexander with poison.’ | ||||

| (SłXVI; Historyja Aleksandra Wielkiego, 1550) | ||||

Notably, in SłXVI we find hardly any examples with inferential use. What we do find is jakoby clauses as clausal arguments of cognitive states, as in (31), which corresponds to modern usage (see Section 3).

| wiele | ludz-i | proſt-ych | mniemái-ą/ |

| many | people-gen | simple-gen.pl | assume[ipfv]-prs.3pl |

| iákoby | t-á | Mſz-á | wáſz-á |

| rep.comp | dem-nom.sg.f | mass[f]-nom.sg | your-nom.sg.f |

| by-ł-a | od | Krystuf-á. | |

| be-lf-sg.f | from | Christ-gen | |

| ‘Many simple people assume that this your Mass was/is from Christ.’ | |||

Finally, SłStar and SłXVI give only scarce evidence for jakoby-clauses referring to (illusory) perception, for instance after zda(wa)ć się ‘seem’ or śnić ‘dream’; see however (27) and (32).[14]

| w ten cżas | |||

| mi.ſie | widzia-ł-o | iákoby | wrazi-ł |

| 1sg.rm | see[ipfv]-pst-sg.n | sim.comp | press[pfv]-lf-(sg.m) |

| w mé ſerce miecż oſtry. | |||

| ‘At this moment, it seemed to me as if he forced a sharp sword into my heart.’ | |||

| (SłXVI; Baltazar Opec: Zywot pan Iezu Kriſta, 1522) | |||

Jędrzejowski’s (2020) investigation does not give any corpus evidence for the 16th century (he sets 1543 as the beginning of the Middle Polish period, but the data from KorBa, which he used, start with 1600). Unfortunately, the 16th century remains a “dark period” for corpus-based studies in the history of Polish, after all. Consequently, claims concerning distributional patterns have to be treated with special caution not only for Old Polish (largely the time until 1500) with its very limited text sources, but no less for the 16th century.

4.2 Corpus-based investigation: 1600–2012

Let us now continue with a corpus-based study on the subsequent periods.

4.2.1 Design of the study

For an investigation of the time after the 16th century up to modern Polish, I designed a study based on annotated electronic corpora, whose combination allows covering the period from 1600 up to 2012 almost without gaps, although not entirely evenly. The time 1600–2012 was divided into four uneven periods: 1600–1649, 1700–1750, 1753–1925, 1945–2012. Random samples (à 200 tokens) were composed for the first two periods from KorBa and for the last period from the PNC, while the third period – the longest one covering mainly the 19th century – was represented by two smaller corpora, from which all jakoby tokens were extracted and composed into one non-random sample consisting of 290 tokens. The queries accounted for all spelling variants, including disjoint ones (jako by). The figures are provided in Table 2 (for the corpus URLs see References). Despite the partially unequal size and quality of the samples, the statistical figures below can certainly be considered a good approximation for written Polish of the respective periods.

Corpora (see references) and sample sizes.

| Corpus (size in tokens) | Abbreviation | Number of tokens | Period | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| KorBa, before 1650 | KorBa_17 | 200 (random) | 1600–1649 | |

| KorBa, 1700–1750 (>13 mln, for entire KorBa)a | KorBa_18 | 200 (random) | 1700–1750 | |

| DiAsPol (2.285 mln; as of 27.07.2020) | Pol_XIX | 122 | Σ 290 | 1753–1928 |

| Pol_preWar (almost 10 mln)b | 168 | 1824–1925 | ||

| PNC (>300 mln, balanced)c | Pol_modern | 200 (random) | 1945–2012 | |

-

aIncluding 64,348 person-number enclitics (of l-forms for past tense and subjunctive). bIncluding 16,303 person-number enclitics (of l-forms for past tense and subjunctive). cIncluding 1,627,574 person-number enclitics (of l-forms for past tense and subjunctive).

This corpus study differs from the study presented by Jędrzejowski (2020) in several respects. Jędrzejowski’s analysis included corpus data for the 14th–15th centuries (from PolDi), which is a big advantage. As concerns, however, the subsequent centuries (from 1600 onwards), the present study can be considered as much better suited to representative sampling. First, its samples are considerably larger, and the period covered by KorBa is split into two subperiods (separated by a 50-year interval). Second, all samples but one were randomized. Third, the present study takes into account all uses of jakoby, including particle use, its earlier uses of adverbial subordinator and instances in which it was written disjointly (jako by). Moreover, a serious drawback of Jędrzejowski’s analysis of jakoby occurring after ‘verbs of thinking’ is that it fails to distinguish between true inferential use and use to simply mark other people’s cognitive attitudes (without referring to an inference). This amounts to ignoring the crucial difference I pointed out in Section 3; the result is a partially erroneous analysis, also for Old Polish. However, on close inspection, most of Jędrzejowski’s findings prove compatible with my analysis and even support it (see Sections 4.2.2.2 and 4.3).

The samples listed in Table 2 were further annotated manually. Table 3 presents the grid of criteria and their values that are analyzed below.

Criteria grid.

| Properties of jakoby | If jakoby = complementizer or WH-word |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Semantic function | Syntactic status | With person/number enclitics | PoS of CTP |

|

sim(ilative) att(itude) rep(ortive) quot(ative) purp(ose) man(ner) other |

ptc (particle) comp conj(unction) wh(-word) other |

Yes/no | Verb Noun Other |

Under sim(ilative) function I subsumed reference to perceptual events, since these were attested by only a handful of cases (see Section 4.2.2.2). The label att(itude) refers to cases in which jakoby was used to assign a cognitive attitude (belief state or conclusion) to other people. A truly inferential function – in the sense elaborated on in Section 3 – was practically unattested. If a value of some criterion could not be assigned unambiguously, _d (= doubtful) was added, but I will not discuss these cases as such. The annotation was double-checked.

Complementizer function (comp) was assigned on a rather “liberal” basis: whenever jakoby occurred clause-initially and in the immediately preceding clause there was an expression that suited as a CTP (i.e., the jakoby-clause could be interpreted as its clausal argument), I counted the jakoby-token as a complementizer. This corresponds to the “pragmatic” solution applied by Schmidtke-Bode (2014: 26), which is not without its problems. However, since all samples were treated alike, their comparison nonetheless lends reliable support to conclusions on diachronic change.

4.2.2 Results

I will start with the syntactic functions of jakoby and its development as a complementizer before I turn to its semantic functions.

4.2.2.1 Relation between reportive function and complementizer use

The complementizer use of jakoby increased over the examined periods, but one wonders how this connects to the acquisition of a predominant reportive function. The answer can be approached from different angles. We can just count the occurrences of jakoby with reportive function, divide them in complementizer and particle use (including doubtful cases) and calculate the coefficients per period; see Table 4a. The counts of complementizer uses include cases in which jakoby marked the assignment of epistemic attitudes (see Section 4.2.2.2). The latter use was altogether absent in particle use.

Proportions of reportive complementizer versus particle (coefficients).

| COMP/PTC | ||

|---|---|---|

| KorBa_17 | 20/13 | = 1.54 |

| KorBa_18 | 37/15 | = 2.47 |

| Pol_XIX | 67/22 | = 3.05 |

| Pol_modern | 121/44 | = 2.75 |

In all periods, complementizer use exceeds particle use by at least the factor 1.5, and this preponderance increases over time; in the third period the coefficient is almost twice as high as in the 17th century, afterwards, it drops slightly.

Conversely, we may ask for the relation between reportive and similative function in jakoby’s use as a complementizer; see the figures in Table 4c. If we introduce the raw figures into contingency tables for different combinations of periods, a significant difference emerges only if the first two periods (17th and mid-18th centuries) are jointly opposed to the last two periods (end of 18th to 21st centuries); however, the effect size is weak:

χ 2 = 4.2153, df = 1, p = 0.04006*, Cramer’s V: 0.115

In combination with the figures in Table 4c below this indicates that, since the 17th century, the dominance of the reportive over the similative function as complementizer increased steadily, but overall less than moderately. A remarkable change occurred only recently, during the last 100 years.

Furthermore, apart from the changing coefficients of complementizer versus particle use in reportive function (see Table 4a), we can ask how this relation looks on the background of other functions that jakoby had in its history (for their overview see Table 5). Consider the following. On the one hand, as a complementizer, jakoby practically only occurs with finite predicates, and this correlates with its propositional scope. On the other hand, jakoby, regardless of its syntactic behavior, can (but need not) have propositional scope with “similative complements” as well (see Section 4.1). In order to assess the relation between reportive complementizer and reportive particle on this backdrop, we should assess the changes in the share of complementizer use in the samples against the changes that occurred in the proportions between similative and reportive use in the same samples. Tables 4b and 4c supply the relevant figures. Table 4b supplies the proportions between the syntactic functions (doubtful cases are indicated in brackets and they partake in the counts; not all figures sum up to 100 %, because uninterpretable cases were excluded).

Syntactic status: changes over periods (regardless of semantic function).

| Adverbial subordinator | WH-word | Complementizer | Other (incl. particle) | 100 % of sample | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KorBa_17 | 54 (1) 27.5 % |

13 6.5 % |

33 (13) 23 % |

75 37.5 % |

200 |

| KorBa_18 | 38 (10) 24 % |

12 6 % |

46 (5) 25.5 % |

74 37 % |

200 |

| Pol_XIX | 31 (5) 12.4 % |

1 0.3 % |

81 (11) 31.7 % |

144 50 % |

290 |

| Pol_modern | 0 | 0 | 131 (3) 67 % |

66 33 % |

200 |

We notice an enormous increase of complementizer function in the last period, when only the distinction between complementizer and particle is left (for its coefficient see Table 4a). All changes of proportions taken together are highly significant, although the effect size is, again, rather small (χ 2 = 163.55, df = 9, p < 2.2e-16; Cramer’s V: 0.254).

Now compare this with Table 4c, which shows the proportions of jakoby as a complementizer with similative function (including reference to perception) and with reportive function (including uses of assigning epistemic attitudes) in their samples.

Complementizer use with similative versus reportive function.

| Similative | Reportive | 100 % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| KorBa_17 | 11 (5.5 %) | 20 (10 %) | 200 |

| KorBa_18 | 11 (5.5 %) | 37 (18.5 %) | 200 |

| Pol_XIX | 22 (7.6 %) | 67 (23.1 %) | 290 |

| Pol_modern | 2 (1 %) | 121 (60.5 %) | 200 |

Obviously, only a small number of complementizer tokens occurred in similative function over all examined periods. In modern Polish, similative complementizer use approximates zero, while reportive complementizer use contributes more than half of all tokens. If, in addition, similative and reportive use are compared against the remainder of functions over the periods, the same highly significant figures result (p < 2.2e-16), but effect size becomes stronger only if the last period is compared to all the remaining three ones (Cramer’s V = 0.393).

Jointly, these comparisons let us conclude that, since the 17th century, a reportive function of jakoby has been more closely associated to its complementizer use than to its particle use; this association increased steadily and most drastically between the 19th century and the post-war period.

4.2.2.2 Changes in jakoby’s semantic functions

Over all samples, there is only a handful of examples in which jakoby behaves as a complementizer in inferential function. In all those cases the inference seems to be based on perception (see (33)). For counts, these few cases were united with jakoby referring to perceptual events (as in (34). The border between perception and perception-based inference is notoriously fuzzy. Example (34) clearly relates to an impression (an immense headache) which is simply compared to something obviously fictive (biting of worms in the head). Example (33), in turn, comes closer to an inferential function, although it lacks an indication of the basis of judgment (also in the broader context) – which makes it difficult to draw a line between an inferential function and an epistemic function of restricting assertiveness (cf. Wiemer and Marín-Arrese 2022: 33–36).

| Stel-ej | zda-ł | się | jakoby |

| pn[m]-(nom.sg) | seem[pfv]-pst-(sg.m) | rm | sim.comp |

| żadnej nie miał ochoty do opowiadania nam swoich przypadków. | |||

| ‘Stelej did not seem to be eager to tell us about his cases.’ | |||

| (lit. ‘Stelej seemed as though he was not eager …’) | |||

| (KorBa; Gellert: Przypadki szwedzkiej hrabiny G***, 1755) | |||

| Bolenie niezmierne w połgłowiu takie/ | |||

| że | się | zda/ | jakoby |

| comp | rm | seem[pfv]-prs.3sg | sim.comp |

| tam od chrobaka i czerwiu jakiego gryzienie było (…). | |||

| ‘An immense headache such that it might seem as though there was biting by worms.’ | |||

| (KorBa; Anonim, between 1606 and 1608) | |||

The samples brought to light only 7 tokens (out of 200) for 1600–1649, 10 (out of 200) for 1700–1750 and 13 (out of 290) for 1753–1928 with “perceptual” CTPs, predominantly with zda(wa)ć się ‘seem’.

Jędrzejowski (2020: 112, 114) adduces examples like (35)–(36), in which jakoby introduces a clause after ‘verbs of thinking’ (glossing and translation adapted):[15]

| od | t-ego | dni-a | myśli-ł, | ||

| from | dem-gen.sg.m | day[m]-gen.sg | think[ipfv]-pst-(sg.m) | ||

| jakoby | ji | za | trzydzieści | pieniędz-y | przeda-ł. |

| comp.irr | 3sg.m.acc | for | 30 | coin-gen.pl | sell[pfv]-pst-(sg.m) |

| ‘from this day on he thought that he sold him for 30 silver (coins)’ | |||||

| (PolDi; Rozmyślania przemyskie, ≈ 1500) | |||||

| począ-ł | myśli-ć/ | ||||||

| begin[pfv]-pst-(sg.m) | think[ipfv]-inf | ||||||

| jakoby | siebie | i | towarzystw-o | z niewol-i | wyrwa-ć. | ||

| comp.irr | self.acc | and | company-acc | from captivity-gen | tear_away[pfv]-inf | ||

| ‘he began to think how to free himself and his company from captivity’ | |||||||

| (KorBa; Opisanie krótkie zdobycia galery przeniejszej aleksandryjskiej, 1628) | |||||||

Jędrzejowski regards them as indicative of inferential meaning. He found five such cases for Old Polish (in PolDi), only one in KorBa (see (36)) and none for the time after 1765. He also cites an example with mniemać ‘suppose’ (which he obviously counts as verb of speech; 2020: 114–115), but this one is no more convincing than the other examples. Examples like (36), with an infinitival predicate, demonstrate complements with purpose meaning introduced by a WH-word; here, jakoby is used as a transparent composition of jako+by, which died out subsequently (see Section 4.1). Example (35), in turn, does not show any inference, either; the jakoby-clause simply spells out the propositional content assigned to the subject of myślić ‘think’ (see Section 3). Analogous objections apply to the remainder of Jędrzejowski’s examples with think-verbs. He thus does not present any real evidence for jakoby in inferential function. However, some other of his observations and conclusions confirm my own findings. Namely, from 1600 onwards, verbs related to speech acts start outnumbering seem-verbs as potential CTPs of jakoby-clauses (Jędrzejowski 2020: 115). Moreover, clausal complements introduced by jakoby are first attested with seem-verbs (14th century widzieć się ‘appear (as though)’; 2020: 111–112); this supports the assumption that jakoby started its complementizer-“career” in similative function.

As for jakoby in particle use, I did not find a single case with an inferential function in any of the samples. Similarly, only exceptionally did jakoby signal the assignment of an epistemic attitude; the increase of this function, to be noted toward the last period, is mainly due to complementizer use.

Table 5 presents the counts and percentages of jakoby’s semantic functions over the four periods. The numbers of doubtful cases are indicated in brackets, percentages include these cases. Doubtful cases are also included in the inferential statistics presented below. The rows do not always add up to 100 %, because uninterpretable cases were discarded.

Semantic functions of jakoby.

| sim | att | rep | quot | purp | man | other | 100 % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KorBa_17 1600–1649 | 97 (14) 55.5 % |

3 1.5 % |

25 (7) 16 % |

0 | 22 11 % |

8 (1) 4.5 % |

14 7 % |

200 |

| KorBa_18 1700–1750 | 89 (6) 47.5 % |

3 1.5 % |

44 (14) 29 % |

1 0.5 % |

6 3 % |

8 4 % |

5 2.5 % |

200 |

| Pol_XIX 1753–1928 | 153 (15) 57.9 % |

10 (5) 5.2 % |

61 (20) 27.9 % |

0 | 3 1 % |

2 0.7 % |

5 1.7 % |

290 |

| Pol_modern 1945–2012 | 13 (4) 8.5 % |

10 (14) 12 % |

132 (11) 71.5 % |

4 2 % |

0 | 0 | 11 5.5 % |

200 |

Already with the naked eye we can discern some general tendencies:

similative use is on a stable high level until the last period, when it decreases drastically, although it does not disappear;

by contrast, reportive use increases enormously in the last period, while it increases only slightly between the first and the second period;

there is a concomitant increase in the use to mark epistemic attitudes, which suggests that these two changes are connected;

quotative use is exceptional;

jakoby in purpose clauses dies out by the end of the third period, and so does its use in manner clauses (embedded WH-interrogatives).

Over all periods, the similative and the reportive function are the two most frequent ones. If we compare these two against the rest, the changes among jakoby’s semantic functions since 1600 prove to be highly significant, although the effect size is weak:

χ 2 = 9.7154, df = 2, p = 0.007768**, Cramer’s V: 0.156

The effect is much stronger if the last period (modern Polish) is compared to the three earlier periods jointly:

χ 2 = 169.72, df = 2, p < 2.2e-16**, Cramer’s V: 0.437

As Table 6 shows, an even clearer picture emerges if only similative uses are compared against reportive uses (including assignment of epistemic attitudes) for different combinations of periods (<< means ‘much less than’, < ‘less than’).

Similative × evidential uses of jakoby.

| p | Cramer’s V | |

|---|---|---|

| All four samples with each other: | <<0.001** | 0.388 |

| 1600–1649 vs 1700–1750 (KorBa): | <0.004** | 0.175 |

| 1600–1750 (KorBa) vs 1753–1928: | <<0.001** | 0.271 |

| 1600–1750 vs 1753–2012: | <<0.001** | 0.336 |

| 1753–1928 vs 1945–2012 (PNC): | <<0.001** | 0.561 |

| 1600–1928 vs 1945–2012: | <<0.001** | 0.477 |

We may thus subsume that an increase of evidential marking becomes obvious already from the early 17th to the early 18th century, but the most drastic change occurred between the late 18th century and the period after World War II. This confirms a finding by Jędrzejowski (2020: 118).

The enormous increase of jakoby’s functions in the evidential domain is due to reportive use. It takes the lion’s share also compared to the assignment of knowledge/belief states, which is illustrated in (37):

| Obywatel-e | tamc-i | rozumiej-ą/ | ||

| citizen-nom.pl | dem-nom.pl | understand[ipfv]-prs.3pl | ||

| jako.by | zdawna | przychodzi-ł-o | tam | morz-e/ |

| comp.irr | long.ago | come[ipfv]-lf-sg.n | there | sea[n]-nom.sg |

| aż pod brzegi góry (…). | ||||

| ‘Those citizens understand (= hold the opinion) that in former times the sea had come there just up to the mountain (…).’ | ||||

| (KorBa; from a geographical account, 1609) | ||||

To emphasize, in all periods jakoby marked perception or inferences only occasionally, while similative use has survived into contemporary Polish, both as a propositional modifier (see (38)) and with constituents on subclausal level (see (39)).

| Wiadomość | uderzy-ł-a | mnie, |

| message[f]-(nom.sg) | hit[pfv]-pst-sg.f | 1sg.acc |

| jakoby | piorun | trząs-ł (…). |

| sim | lightning[m]-(nom.sg.) | shake[ipfv]-lf-(sg.m) |

| ‘The news struck me as if a lightning was shaking.’ | ||

| (PNC; A. Fiedler: Orinoko. 1957) | ||

| Przez wywarte szerokie podwoje | ||

| widzia-ł | jakoby | teatrum |

| see[ipfv]-pst-(sg.m) | sim | theater-(acc.sg) |

| przyćmionych nieco ewentów własnego żywota. | ||

| ‘Through the wide open door he saw as though the theater of the somewhat overshadowed events of his life.’ | ||

| (PNC; Wł. Reymont: Rok 1794. 1918) | ||

However, the similative use of jakoby has acquired a highbrow, old-fashioned flavor. In this and in manner function other units have been taking over the field, first of all the cognate connective jakby (largely as a transparent composition jak = by). As subordinator of purpose clauses jakoby was ousted by żeby, aby, by considerably earlier.[16]

4.2.2.3 Verbal versus nominal CTPs

The diachronic corpus study furthermore allows to conclude that jakoby’s development into a reportive complementizer was accompanied by a tendency toward nouns as preferred attachment sites. Table 7 shows that, in reportive use, the share of nominal attachments sites of jakoby has dramatically increased. The relation between verbal and nominal CTPs in the modern Polish sample is approximately 1:2 (coefficient 0.5),[17] this proportion is inverse in comparison to the 18th century (coefficient 1.6). Nothing similar can be observed for non-reportive complementizer uses of jakoby, i.e., those of the similative-perceptual domain. These observations support findings in Wiemer (2015: 282–290, 2018: 319–320), in which 14th–16th century data were investigated only on a dictionary basis.

PoS of attachment site of jakoby as complementizer.

| Similative/perceptual verb/noun/other | Reportive verb/noun/other | |

|---|---|---|

| KorBa_17 | 7/1/3 | 16/0/0 |

| KorBa_18 | 11/0/0 | 21/13/3 |

| Pol_XIX | 19/2/1 | 35/26/6 |

| Pol_modern | 0/2/0 | 41/79/1 |

It might be argued that a preponderance of nominal over verbal attachment sites in the reportive domain might follow from a larger amount of speech act-related nouns (including, first of all, derivatives of respective verbs), i.e., from a higher type frequency of nouns in the lexical inventory of Polish. Whether there are really more relevant nouns than verbs – and whether all items of an inventory larger than that of respective verbs are employed as CTPs in actual usage – remains to be settled. In the first place, however, the observed higher token-frequency of speech act-related nouns as CTPs of jakoby-clauses applies for contemporary Polish, and one must still ask why, in the reportive domain, the proportion between verbal and nominal CTPs has become inverse. To give a methodologically impeccable answer, one must first establish inventories of speech act-related verbs and nouns for earlier stages of Polish as well, to compare them with the contemporary stage. For the time being, we may state that the spread of jakoby as a reportive complementizer started in the scope of semantically suitable verbs.

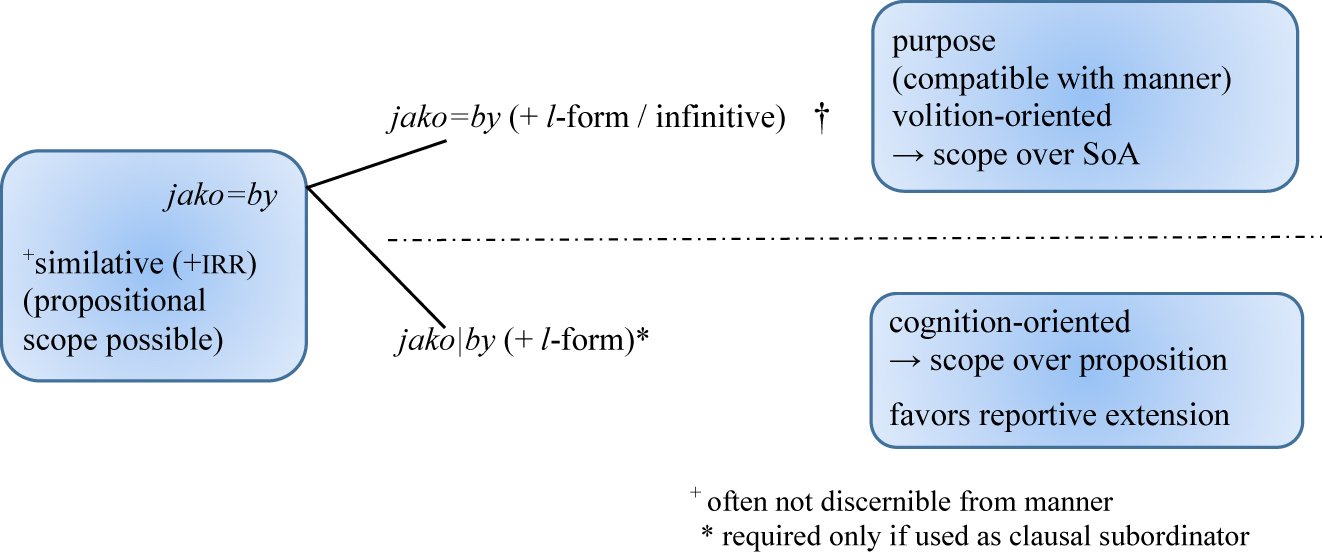

4.3 On univerbation and the similative > reportive shift

Although presently without an ultimate proof, we may assume that cognition-based (i.e., evidential and epistemic) functions of jakoby developed on another path than the volition-based purpose (and the associated manner) function, and that, after the onset of the morphologization process of jako and by, this process bifurcated into two separate “branches” (see Figure 2). Moreover, there were conditions for a shift from similative to reportive usage that “bypassed” the inferential domain. These assumptions are plausible for the following reasons.

Purported diachronic relation between volition- and cognition-oriented uses of jako=by > jako|by.

First, jako is one of the oldest interrogatives and clause connectives in Slavic with an enormously flexible (or vague) range of usages, among which manner (‘how’), quotes, but also the function of an epistemically neutral complementizer figure prominently.[18] The addition of the enclitic =by (+l-form/infinitive) attenuated the reality status, but, as a marker of purpose or manner, this combination never ceased to yield a compositional reading: jako[=by + l-form/infinitive]. This differed for the similative use: although =by attenuated reality status, too, an advanced stage of morphological fusion (i.e., univerbation) ensued, as can be inferred already from those early and frequent instances in which jakoby modified constituents below the clause level, when no l-form of the verb was involved (see Section 4.1). In these cases -by was the only signal of irrealis functions. Despite the unreliability of joint/disjoint spelling (see fn. 14), a correlation between loss of morphosyntactic transparency and the shift from similative to reportive use is obvious, since jakoby has become an inseparable word unit and its reportive use became predominant; as a particle, even the l-form requirement is absent (see Section 3). That is, the compositional reading (jako = by) died out together with manner and purpose uses, whereas loss of transparency (jako|by) was possible very early in similative use. Presumably, this created favorable conditions for the non-transparent usage of jakoby to be “transferred” directly into its emergent reportive use, together with other factors (see below).

Second, as concerns the conceptual connection between comparison and perception with cognition, consider that comparisons can be drawn for objects of different ontological status (cf. Fortescue 2010 for discussion). In accordance with Lyons’ (1977) distinction between objects of first, second (= states-of-affairs), and third order (= propositions) – and adding illocutions as fourth order objects – similative markers can, in principle, be applied to objects on any of these four levels. If used to mark clause linkage, similatives may mark “propositional objects” either as adjuncts or as complements;[19] see the examples in Table 8.

Types of ontological objects linked by similatives.

| Similative (example) | Basis of comparison | Ontological status | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (40) | My hands are like [emery paper]. | First order | Physical object |

| (41) | Lying is like [betraying a friend]. | Second order | SoA, event (can be observed) |

| (42) | He stumbled into the room as if [he were drunk]. → adjunct | Third order | Proposition (target of epistemic and evidential modifiers); related to cognition, but with suspended reality status |

| (43) | It seemed/He pretended as if [he were drunk]. → complement | ||

| (44) | She smiled at me like [“Hey, take it easy!”] | Fourth order | Illocution (target of quotatives), related to behavior |

On this account, jakoby acquired the potential of scoping over propositions very early, and indeed we find such instances already in the oldest attested layers of Polish (see Section 4.1). There is no reason to assume that, in this development, purpose (or manner) uses of jako = by played any role as intermediate stages.

Now, what about connections between comparison, on the one hand, and reports and the assignment of epistemic attitudes, on the other? In most environments, irrealis markers, like -by, suspend propositions, in the sense that propositional content cannot be verified (nor falsified) since -by deprives it of specific referential anchorage. This suspension is tantamount to preventing, or canceling, a realis (a.k.a. factual) reading from the respective clause.[20] Moreover, comparison (i.e., one of the original functions of jako) does not imply identity between two objects (of whatever ontological status, and expressed in whatever syntactic format). If comparison applies to propositional content, lack of identity (plus irrealis marking) easily leads to epistemic distance, i.e., lack of the speaker’s full commitment to the truth of p (this includes a possible agnostic stance). Thus, from a conceptual point of view, suspension of assertion supplies an immediate link between jakoby’s original similative function and its employment in propositional contexts.[21] Before we finish this argument on how jakoby can have entered and become so entrenched in the reportive domain without the “aid” of an intermediate inferential stage, let us reconsider the more “traditional” reasoning.

The shift from perception to inference is well-known; as a reviewer remarked, this shift “consists in that the speaker observes a situation similar to one in which p would have occurred, and infers (by a process that has been called abduction) that p has probably occurred”. This is correct, but, crucially, inference, in particular abduction, is fraught with a varying degree of fault (“has probably occurred”), and this account of failure induces less than a full epistemic commitment to p being true. However, despite this conceptual link, the diachronic data discussed above does not support the assumption that this otherwise widespread shift has played any significant role in the history of Pol. jakoby. We also do not have any attestations of jakoby that would suggest a shift from report-based inferences to reportive meaning proper (for this possible link see the discussion in Section 3). Admittedly, there are occasional instances even from the late 19th century in which clausal complements headed by jakoby acquire an inferential function. One such example was supplied by a reviewer.

| Odnosi się wrażenie, jakoby autor stosował swe uwagi do pewnych wzorców mniemanych władz duszy (…). |

| ‘One gets the impression that the author applied his comments to certain patterns of assumed authorities of the soul.’ (1873) |

Such examples cannot be denied, but they are isolated. Jędrzejowski’s (2020) corpus-based study as well as the much broader corpus study presented here show that such instances at all times (including the Old Polish data) have been extremely rare. There is no reason to assume that these findings are just incidental: why should any of the employed corpora (as well as the diachronic dictionaries) be considered to be less favorable of inferential than of reportive contexts? If, on a diachronic pathway, inferential meaning is assumed not only to precede reportive meaning but even to prepare the soil for its rise, we would expect inferential use to be more frequent than a reportive one at some point, in order to “ease” a transition from similative via inferential to reportive meaning. We may be less strict and admit that, under identical assumptions, salient inferential usage need not be frequent in the period immediately preceding the onset or increase in reportive use, but even then the available data does not meet the expectation. One may then try to argue (as did one reviewer) that a shift from similative (and perceptual) to inferential function already took place at the time of the earliest attestations of Polish (or even earlier), so that we no longer “see” these changes and the fading of its effects. However, apart from being quite untestable, such a hypothesis would drive us to two other problems: first, between the time when jakoby presumably shifted into inferentiality (before 1500) and the time when jakoby started becoming more salient in the reportive domain (17th century) would be separated by at least 200 years. Second, jakoby has kept its original similative meaning until now, albeit as a stylistically marked variant, but it was decidedly more salient through all periods in which there was but faint evidence of jakoby in inferential use.

All these facts considered do not make jakoby look like a unit with a “doughnut history”, i.e., with inferential meaning having “dropped out” after it created favorable conditions for reportive meaning to arise and thereby mediating a transition from its original similative function.[22] We can, instead, assume that jakoby developed under specific bridging contexts that favored its speech-act related potential, but only rarely triggered inferential usage, and that previously emergent speech-act related uses of jakoby began to be amplified during the 17th century. This view on the facts would open up a reasonable alternative account of how jakoby became established in the reportive domain, while retaining its irrealis feature. As argued above, the comparison+irrealis meaning of jakoby can be “carried over” rather directly into propositional contexts, with an ensuing lack of full epistemic support. Apart from this conceptual link, the conditions relevant for emergent complementizer use since Old Polish times were favorable for reportive use, regardless of occasional inferential use. On the basis of these conceptual and empirical preconditions a scenario can be imagined that is compatible with the findings assembled in Sections 3 and 4. In particular, a switch into the reportive domain was possible because jakoby began to be employed as a means of taking a stance with other people’s opinions and assertions: the reporting speaker would keep their less than full epistemic support against other people’s judgments, whether expressed verbally or only implied. This usage – reportive plus epistemic distance – need not be inherited through intermediate perceptual-inferential steps as suggested in Gipper’s pathway (see (4)), or as assumed by Jędrzejowski (2020), in accordance with the mainstream of evidentiality literature.[23] I, therefore, suggest that a shift toward reportive use was favored by the following context conditions:

jakoby more frequently occurred in the immediate vicinity of verbs, later also of other predicative units, that proved suitable as speech-act related CTPs, while such contexts with seem- and other perception verbs were much less frequent; if they occurred, occasional shifts into perception-based inferentiality proved insufficient for inferential meaning to become more entrenched.

Jointly, jakoby was characteristic in rhetorical contexts in which the speaker wanted to take a stance against another person’s assertion or viewpoint and to distance themselves from that opinion, for which the irrealis feature of jakoby proved suitable. The role of rhetoric requires a more thorough check; at present it is based not only on the discourse potential of jakoby in modern Polish (see fn. 2), but also on a repeated perusal of the diachronic material analyzed above.

An additional supportive factor was the metonymic link between cognitive stances and utterances that express them (see Section 3). No mediating inferential function was required, instead the similative source meaning could largely do without a perceptual background (= Gipper’s stage II) in order to apply to other people’s utterances and related epistemic attitudes.

This scenario takes the lack of full epistemic support as a constant feature of jakoby throughout its history (as does Jędrzejowski 2020 and as would comply with Gipper’s assumptions), but it avoids all problems in explaining why inferential usage obviously has not played any considerable role as a mediating stage in pathways discussed hitherto.

Figure 2 summarizes these considerations: jako|by indicates that the erstwhile enclitic =by turned into an inseparable segment of a new word (whereby univerbation was completed). We should remember that in similative (comparison) use jako(by) could often be read as a manner marker as well (see Section 4.1), and that the latter function is compatible with purpose (see (23)–(24)). The interrupted horizontal line is to indicate that the volition- and the cognition-based usage types belong to different developmental paths.

5 Conclusions

The facts analyzed for Pol. jakoby and the argument developed in Section 4.3 justify a diachronic pathway as presented in Table 9; it mainly accounts for the complementizer use. The underlying scenario stands as a working hypothesis.

Functional development of jakoby.

| (i) | Comparison/similitude (jako), attenuated by irrealis marker (-by) | Objects are compared to types; comparison is flexible for objects of different ontological status (in Lyons’ sense) |

|

This flexibility makes possible a domain shift | |

| (ii) | Lack of full epistemic supporta | (Commitment to) propositional content is suspended + speaker refers to other people’s assertions in order to take stance with them |

|

Metonymic shift | |

| (iii) | Assignment of epistemic attitudes to other people (manifested by their utterances and/or behavior) | = [2a] in Table 1 |

-

aAs a side remark, the inner form of expressions like Eng. veri-similitude and its equivalents, e.g., in Polish (prawdo-podobieństwo) and Russian (pravdo-podobie) reflects the conceptual “mélange” of similarity and knowledge.

Stage (ii) spells out jakoby’s reportive function, while (iii) refers to its function in assigning epistemic attitudes with associated utterances. As pointed out in Section 3, it is crucial to realize that, if jakoby does not mark directly the propositional content of utterances (= hearsay), it never refers to inferences, but simply ascribes epistemic attitudes on the basis of utterances (or its behavioral equivalents); in other words: contemporary jakoby never refers to the evidential background of how a judgment was acquired, but only scopes over the propositional content of speech acts or metonymically related cognitive attitudes labeled by a predicate (verb or noun). Jointly with this, the analysis of diachronic data does not favor an assumption that behavior observed and interpreted by the speaker might have preceded utterances as an alternative basis for the assignment of attitudes.

I have furthermore shown that comparison markers need not turn into evidential (or epistemic) modifiers (e.g., particles or complementizers) in order to acquire propositional scope; rather inversely, the potential to scope over propositions seems to be a precondition for similatives to proceed on this path of functional development. For instance, cognates in other Slavic languages, like Cz. jako by, jakoby, Slk. ako by, akoby, only have similative and manner uses, in particular as complementizers after seem-verbs, and no evidential uses have developed. In fact, Pol. jakoby stands out for its reportive use at least on a European background (Wiemer 2018: 314–317, 321–328, 2022: 692–699). No comparable cases are mentioned in Boye et al. (2015), however some similative connectives in languages of Northeastern Europe do behave like reportive complementizers in certain contexts; cf. Holvoet (2016: 238–241) on Baltic and Kehayov (2016: 456–458) on Finnic.