Abstract

The main aim of this article is to investigate the prosody-information structure interface in the analysis of the Hungarian additive particle is ‘also, too’. We present a prosodic study of narratives, collected through guided elicitation, and provide a prosodic basis for a focus-based analysis of is. Standard formal semantic approaches to the interpretation of additive particles regard additive particles as focus sensitive, hence the associate of the particle is focal and the focus interpretation (in terms of alternatives) is a significant part in its semantics. This view is considered crosslinguistically valid, although the discussion mostly concerns English. In Hungarian, the focus sensitivity of the additive particle is not directly transparent and needs more elaboration. In the relevant literature, the issue of focus marking with respect to the additive particle is has been insufficiently studied or merely stipulated. In this article, we argue for the importance of a more elaborate study of the prosody-information structure interface in the analysis of Hungarian additive particles. Accordingly, we provide data and its analysis to support our core argument and claims. Our study contributes to the overall understanding and analysis of is and to the general claims about focus marking and focus types in Hungarian. We aim to complement the standard semantic analyses by providing a prosodic analysis supporting the focus-sensitive analysis of is instead of merely stipulating an association with focus. On a more general level, we show that the various readings of additive particles can be explained by taking the prosodic patterns of the relevant constructions into account.

1 Introduction

The starting point of our investigation is the general view that additive particles are crosslinguistically focus sensitive. As shown in foundational formal semantic approaches, the interpretation of a range of particles is dependent on the focus structure of the utterance. The phenomenon is well-known as ‘association with focus’ (König 1991; Krifka 2006; Rooth 1985) or ‘focus sensitivity’ (Beaver and Clark 2002, 2008). Such focus sensitive particles are, for example, the exclusive marker only, the additive particle also and the scalar particle even. The interpretation of sentences containing such focus sensitive particles depends on the placement of the focus marking.[1] The interpretational differences are either truth-conditional, as in the case of only (1), or presuppositional, as in sentences containing also (2).

| a. | Peter only introduced BILL to Mary. |

| b. | Peter only introduced Bill to MARY. |

In (1), the ‘focus’, marked by prosody in English (for the sake of simplicity, indicated by capitals), determines the domain of quantification of only and hereby affects the truth-conditions of the given sentence (Rooth 1992), for example, a situation where Peter introduced Bill to Mary makes (1b) false, but not (1a).

It is argued in formal semantic analyses (see, e.g., König 1991; Krifka 2006) that sentences containing the particle also come with an existential/additive presupposition.[2]

| a. | Peter also introduced BILL to Mary. |

| b. | Peter also introduced Bill to MARY. |

In both sentences in (2), the assertion is the proposition Peter introduced Bill to Sue. However, the sentences differ in their presuppositions. (2a) presupposes that there is at least one person different from Bill, such that Peter introduced him/her to Sue, while (2b) presupposes that Peter introduced Bill to at least one other person than Sue.

| a. | assertion in (2a) and (2b): introduce′ (p,b,m) |

| b. | presupposition of (2a):

|

| c. | presupposition of (2b):

|

The additive presupposition is directly derived from the focus interpretation (based on alternatives) of the given sentence, which is determined by the placement of ‘focus’ (i.e., focus marking). In the approaches taken by König (1991) and Krifka (2006), focus sensitive particles are analyzed as operators on structured propositions, representing the focus structure of the utterance as an ordered triple consisting of the focus (Foc), the alternative set (Alt) and the background

|

|

|

|

|

|

The definition in (4) derives the desired assertion and presupposition for the sentences in (2). For an illustration, consider the interpretation of (2a). The interpretation of (2b) in (5) is derived in the same way.

| a. | Peter introduced BILL to Mary. →

|

| b. | Peter also introduced BILL to Mary. → also

|

|

|

|

|

|

Other approaches, (e.g., Szabolcsi 2017, 2018), derive the semantics of the additive particle with Alternative Semantics (Rooth 1985, 1992).

In English, focus marking is primarily prosodic, the focal constituent is marked by (the nuclear) pitch accent. This focus marking is independent of the presence of also. If we remove also from (2a), it automatically results in the focused sentence in (5a), which serves as the basis for the interpretation of the additive particle in (2a).

| a. | Peter also introduced BILL to Mary. |

| a. | Peter introduced BILL to Mary. |

In Hungarian, however, focus marking related to the additive particle is ‘also, too’ is less straightforward and needs more elaboration. In the next section, we discuss this issue in more detail, and introduce the structural properties of sentences with is ‘also, too’, as well as the general issue of focus marking in Hungarian. In Section 3, we briefly present previous work and approaches to the prosody-syntax interface in Hungarian. Section 4 presents our prosodic study, followed by our proposal and conclusions in Section 5.

2 The Hungarian additive particle

In this section, we quickly introduce the language specific properties of the Hungarian additive particle is ‘also, too’ and present the issues raised for a uniform focus sensitive analysis. In the following, we briefly discuss the structural marking strategies of information structure in Hungarian, and thereby also show the structural distribution of the particle is. We will show that the phrase with is neither occupies the clause-initial ‘topic position’ nor the preverbal ‘focus position’. Next, we discuss the issue of how focus is marked in Hungarian and how to capture the focus sensitive nature of is, i.e., how to account for the focal status of the associate of the particle instead of merely stipulating it. At the end, we will introduce various readings and constructions with is that form the basis of our prosodic study.

2.1 Syntactic distribution

The amount of research on information structure in Hungarian is extensive and the literature dates back to the late 1970s.[3] One of the most well-known characteristics of the Hungarian language is its discourse-configurational type (É. Kiss 1995; Surányi 2015), where surface order and certain syntactic positions are closely related to the discourse-semantic/pragmatic functions, ‘topic’ and ‘focus’. Topical elements appear in a clause initial position (6a), and the narrow identificational focus of the utterance occupies the immediate preverbal position and triggers inverse order of the verbal particle [vprt] and the verb (6b).

| [Mari-nak]TOP | be-mutatta | Péter Vili-t. |

| Mary-dat | vprt-introduced | Peter Bill-acc |

| ‘Peter introduced Bill to Mary.’ | ||

| (

|

||

| [Mari-nak]FOC | mutatta | be | Péter Vili-t. |

| Mary-dat | introduced | vprt | Peter Bill-acc |

| ‘Peter introduced Bill to MARY.’ | |||

| (

|

|||

The constituent in the structural focus position (6b) gets the nuclear pitch accent and is assigned an interpretation in terms of exclusion by identification (É. Kiss 1998; Kenesei 2006; Szabolcsi 1981). Placement in the immediate preverbal position is claimed to be an obligatory and default marking strategy for (identificational) narrow focus constructions (e.g., Genzel et al. 2015). Next to this structural focus marking, it is widely assumed that other, syntactically unmarked, focus structures are also available (see, e.g., É. Kiss 1998; Surányi 2011). However, most work on non-structural focus marking concentrates on postverbal focus and the issue of exhaustivity. The possibilities of mere prosodic focus marking in the preverbal field, however, are seriously under-studied or not even acknowledged (see more in Section 2.2).

The Hungarian additive particle is ‘also, too’ is an enclitic:[4] it is destressed and needs a syntactic host, with which it forms a phonological word. It is positionally bound to a constituent, very often but not exclusively a noun phrase. We will refer to the constituent and the particle together as the ‘is-phrase’. A frequency analysis on the Hungarian National Corpus (http://corpus.nytud.hu/mnsz/ [Oravecz et al. 2014]) shows that in around 64% of all occurrences, it is attached to a noun or pronoun.[5] It can also be attached to adverbials (

| Péter | Vili-t | is | be-mutatta | Mari-nak. |

| Peter | Bill-acc | also | vprt-introduced | Mary-dat |

| Péter | be-mutatta | Vili-t | is | Mari-nak. |

| Peter | vprt-introduced | Bill-acc | also | Mary-dat |

| ‘Peter also introduced BILL to Mary.’ | ||||

| Péter | Mari-nak | is | be-mutatta | Vili-t. |

| Peter | Mary-dat | also | vprt-introduced | Bill-acc |

| Péter | be-mutatta | Vili-t | Mari-nak | is. |

| Peter | vprt-introduced | Bill-acc | Mary-dat | also |

| ‘Peter also introduced Bill to MARY.’ | ||||

As for its surface position, it has been shown that in the preverbal field, the is-phrase cannot occur in the topic field, nor in the immediate focus position (e.g., É. Kiss 2004; Szabolcsi 1997). One argument to support the claim that the is-phrase does not appear in the topic field is given by the linearization constraints of sentence adverbials (e.g., szerencsére ‘fortunately’). In the preverbal field, sentence adverbials cannot enter the comment[6] but can mark the right edge of the topic field (see, e.g., É. Kiss 2004; Kálmán 2001). Example (8b) illustrates that the adverbial cannot follow the is-phrase, which indicates that the latter is not in the topic field.

| [Péter]TOP | szerencsére | [Vili-t | is | be-mutatta | Mari-nak]COMM |

| Peter | fortunately | Bill-acc | also | vprt-introduced | Mary-dat |

| ‘Fortunately, Peter also introduced BILL to Mary.’ | |||||

| *[Péter | Vili-t | is]TOP | szerencsére | [be-mutatta | Mari-nak]COMM |

| Peter | Bill-acc | also | fortunately | vprt-introduced | Mary-dat |

Now consider the contrast between (9b) and (9a) which illustrates the claim that the is-phrase in Hungarian is excluded from the immediate preverbal focus position. In (9b), the inverse order of the verb and the verbal particle (vprt) indicates that the is-phrase occupies the immediate preverbal focus position, but this linearization is considered ungrammatical.

| Péter | Vili-t | is | be-mutatta | Mari-nak. |

| Peter | Bill-acc | also | vprt-introduced | Mary-dat |

| ‘Peter also introduced BILL to Mary.’ | ||||

| *Péter | Vili-t | is | mutatta | be | Mari-nak. |

| Peter | Bill-acc | also | introduced | vprt | Mary-dat |

This syntactic behavior can straightforwardly be explained on semantic grounds by virtue of the exhaustivity effect assigned to the preverbal focus position[7] that is incompatible with additivity (see, e.g., É. Kiss 1998; Szabolcsi 1981).

2.2 Focus sensitivity of is

It is generally accepted that additive particles are crosslinguistically focus sensitive. In English, focus marking is primarily prosodic and the focused constituent bears the nuclear pitch accent.[8] Based on the focus marking, the sentence has different focus-alternatives, by which the additive presupposition is derived (e.g., Krifka 2006; Szabolcsi 2017). A similar semantics is claimed for Hungarian as well (see Szabolcsi 2017), proposing a uniform formal semantic analysis of additive particles. However, in Hungarian sentences containing the additive particle is, focus marking is not directly transparent, at least not structurally (as shown in the previous section). Nevertheless, the Hungarian additive particle is claimed to be focus sensitive, with similar semantics to the corresponding English sentences (see Example 10).

| Péter | Vili-t | is | be-mutatta | Mari-nak. | (=9a) |

| Peter | Bill-acc | also | vprt-introduced | Mary-dat |

| Peter also introduced BILL to Mary. (= 2a) |

| for both: |

|

|

|

|

For such a uniform semantic analysis, the crucial question with respect to Hungarian is how to capture the focal status of the host of the particle is. As shown before, structural focus marking is not an option here. It is accepted that focus marking outside of the preverbal focus position also occurs in Hungarian. However most work on this issue concentrates on postverbal focus marking and the expression of two focus types considering the question whether exhaustivity involved (see, e.g., É. Kiss 1998; Surányi 2011).[9] The relevant distinction here is made by É. Kiss (1998) introducing the notions of identificational focus and information focus. The latter focus type expresses new information focus without identification and exhaustivity. It is not structurally marked but bears prosodic prominence. This notion could be a promising candidate in the analysis of is. However information focus is claimed to only appear postverbally (or “in situ”). This is explicitly stated in a recent characterization by Surányi (2015), referring to previous works by É. Kiss (1998, 2015) and Horváth (2007, 2010): “All and only identificational foci must be fronted to a dedicated left peripheral pre-verbal position, and all and only plain information foci must remain in situ.” (Surányi 2015: 432). Consequently, this distinction cannot account for the focus sensitivity of preverbal occurrences of is.

As shown in the previous section, the is-phrase cannot occur in the preverbal ‘focus position’, nor in the clause-initial ‘topic position’. In the preverbal field, it occupies a designated position between the structural ‘topic’ and ‘focus’ (11).[10]

| [Péter]TOP | Vili-t | is | [Mari-nak]FOC | mutatta | be. |

| Peter | Bill-acc | also | Mary-dat | introduced | vprt |

| ‘It is Mary whom Peter also introduced to BILL.’ | |||||

This position is not discussed in detail in relation to focus marking and focus types in the relevant literature on Hungarian. In some earlier syntactic and formal semantic accounts, the particle is is analyzed in terms of ‘focus’ (see, e.g., Brasoveanu and Szabolcsi 2013; Brody 1990; Szabolcsi 2017, 2018). However these authors merely stipulate the given focus structure, without discussing how to derive the focal status of the associate. In only a few places (e.g., Kálmán 1985b), has it been stated that the syntactic host of is has a focus accent, albeit without any further discussion on the matter. These works do not investigate the type of accent or the prosodic patterns of the various constructions with is nor do they discuss how it relates to the general issue of focus marking and focus types in Hungarian. With this study we aim to contribute to these questions.

In this article, we support the claim that additive particles are crosslinguistically focus sensitive and that a semantic analysis in terms of focus alternative is the appropriate one across languages. However, this claim needs further justification and grounding in Hungarian,[11] where focus marking (and information structure in general) behaves significantly differently than in English.

In Hungarian, investigations and analyses of the information structural notions topic and focus, or to be precise sub-types of these, mostly concentrate on the designated structural positions and their syntactic/semantic characterization. Analyses on the prosody-syntax interface (e.g., Kálmán 1985b; Szendrői 2001, 2003; Varga 2002) also mostly concentrate on the prosodic characteristics of the preverbal position. Although flexible focus marking is acknowledged to some degree, the construction with additive particles has not received special attention so far in terms of focus marking and the derivation of the focus structure. In this article, we propose such an analysis and argue for a more prominent role of prosody in the analysis of the Hungarian is ‘also, too’ in the interface of prosody and information structure.

2.3 The semantic associate and various uses

Besides the (syntactic) host (see Section 2.1), we need to refer to the semantic associate (or simply associate) of the particle, which is the element or constituent that is taken as the ‘focus’ and, as such, determines the alternatives and the additive presupposition of the sentence. An important issue is then how to derive the semantic associate, and what linguistic means mark the appropriate focus structure. We argue in this article that the prosodic patterns of sentences containing is determine the focus domain and consequently, contrary to what Surányi (2015) and É. Kiss (1998) assume, that certain focus types distinct from the preverbal, identificational focus can be found in the preverbal field. For a comprehensive analysis of the prosody-information structure interface of Hungarian is-phrases, two aspects are particularly significant: (1) the marking of the range of the focus domain and (2) the various uses of the particle is.

2.3.1 The range of the focus domain

In the frequently discussed cases, such as Example (7), the syntactic host and the semantic associate correspond. However, this is not necessarily the case. As already pointed out by Szabolcsi (2017), see Example (12), the additive particle is can take different scope, hence the range of the associated focus domain may vary. These different focus structures lead to different interpretations with respect to the additive presupposition of the sentence.

| Mary yawned. [BILL]F yawned, too. |

| Mari ásított. [BILL]F is ásított. |

| Mary was fidgeting. [BILL yawned]F, too. |

| Mari fészkelődött. [BILL is ásított]F. |

| (from Szabolcsi 2017: 457, Ex. 4–5) |

This claim holds both for English and Hungarian, despite the significant structural differences of additive-constructions in the two languages. Focus marking strategies in English (prosodic focus marking and focus projection) cannot be directly applied to Hungarian and need a more detailed investigation. There is indisputable evidence (i.e., language data) supporting the claim that different focus structures are available with the same construction with is ‘also, too’ (see also Szabolcsi 2017). It can further be confirmed by a wide range of data from guided elicitations, see, for example, (13), translation experiments (Balogh 2021) and data from the Hungarian National Corpus.

| local discourse context: So, he(=frog) sat angrily on a stone and waited for what would come out of all this. | ||||||||

| A | kisfiú | is | elég | dühös | volt | már | eddigre, | |

| the | boy | also | rather | angry | was | already | by.then | |

| ‘[The boy]SA was also pretty angry by then,’ | (SA = narrow) | |||||||

| local discourse context: And they(=boy+dog) went out to look for the frog. They went into the forest and called him aloud, | ||||||

| majd | pedig | [a | fák-ra | is | föl-mászt-ak]SA, | |

| then | and | the | trees-sub | also | vprt-climbed-3pl | |

| ‘then they also [climbed up the trees]SA,’ | (SA = predicate) | |||||

| local discourse context: Then he(=boy) began to look for what he was hearing behind a big tree. | ||||||

| [A | kutya | is | segített | neki]SA | ||

| the | dog | also | helped | him | ||

| ‘[The dog helped him]SA, too’ | (SA = sentence) | |||||

| (from own elicitation of the ‘Frog Stories’) | ||||||

The examples above show that the same surface configuration (with the is-phrase in the preverbal field) leads to different interpretations and different presupposition conditions depending on the range of focus the additive particle operates on. In the examples, we indicate the semantic associate (hence the range of focus) by [ ]SA.

Given the respective local discourse contexts of the target sentences above, we can determine the focus domain (narrow, predicate or sentence) of the sentences. Such a context-based analysis is proposed by Balogh (2021), which corresponds to Lambrecht’s (1994) notion of pragmatic focus, and his analyses of narrow, predicate and sentence focus respectively. A context-based analysis of the focus sensitivity of the additive particle is is appealing and suitable in many cases. However, as we will show later, it is not always sufficient. We will discuss examples where the context suggests the incorrect focus interpretation and argue that in such cases the prosodic structure of the sentence indicates the right semantic associate. Furthermore, a purely context-based analysis using Lambrecht’s (1994) notions represents a different view than the classical formal semantic accounts of additive particles. In the latter, independent means (e.g., prosody, syntax) determine the focus structure, which in turn determines the additive presupposition that postulates certain requirements to the context.

2.3.2 Various uses of is

In order to support a uniform, focus sensitive analysis of the additive particle is in Hungarian, we need to investigate the prosodic patterns of a broader range of language data, i.e., we need to look at various uses and constructions of is. As already argued by Forker (2016), additive particles can be used in a multi-functional way across languages. In Hungarian, next to the plain additive use, the particle is is also used in various other ways. In this article, we will discuss the readings:

where the particle is used as a plain additive particle meaning also, too (14a),

where it is interpreted as a scalar particle meaning even (14b),

in a special reiterated construction expressing coordination (14c), see also Brasoveanu and Szabolcsi (2013) and Szabolcsi (2017),

constructions used for listing (14d) and

a special use we call the ‘indeed-reading’ (14e).[12]

The reading in (v) is rather particular and has not received attention in the semantic-pragmatic literature so far. Also, the use of listing (14d) is under-represented in the literature. Our data represents all these different uses.[13] The examples in (14) are all from our own collected data.

| plain additive: | |||||||

| A | kisfiú | is | elég | dühös | volt | már | eddigre, |

| the | boy | also | rather | angry | was | already | by.then |

| ‘The boy was also pretty angry by then,’ | |||||||

| scalar additive: | ||||||

| és | még | a | teknősbéka | is | el-bújt | teknőc-é-be. |

| and | yet | the | turtle | also | vprt-hid | shell-3sg.ps-ill |

| ‘Even the turtle hid in his shell.’ | ||||||

| coordination: | |||||||

| A | kisfiú | is, | ő | is | ki-hajolt-ak | az | ablak-on. |

| the | boy | also, | he | also | vprt-leaned-3pl | the | window-sup |

| ‘The boy and the dog (both) leaned out of the window.’ | |||||||

| listing: | |||||||||

| egy | kutya, | egy | béka | és | egy | teknősbéka | is | kíváncsian | várja, |

| a | dog | a | frog | and | a | turtle | also | curiously | wait |

| ‘a dog, a frog and a turtle, are waiting for him curiously’ | |||||||||

| ‘indeed-reading’: | ||||

| local discourse context: He was thinking to go to their place, following the footsteps of the boy and the dog. | ||||

| Meg | is | érkezett | a | lakás-uk-ba. |

| vprt | also | arrived | the | flat-3pl.ps-ill |

| ‘And, indeed, he arrived in their place.’ | ||||

As for the structural distribution, the above readings occur in various constructions. As already discussed above, the syntactic host of the additive particle can either be an argument, an adjunct or the verb (or verbal complex). If it is attached to an argument or adjunct, it can equally appear in the preverbal and the postverbal field. Following the arguments by, for example, É. Kiss (2004) and Szabolcsi (1997), we conclude that the is-phrase cannot occupy the immediate preverbal position when it appears in the preverbal field. Postverbally, the is-phrase can appear in any position, as the linear order in the postverbal field is generally free. The particle can also cliticize to the verb if it has no verbal particle (or other verbal modifier[14]). Or in case of verbs with a verbal particle (or modifier), the additive particle appears between the verbal particle (or modifier) and the verb, cliticized to the former. This linearization occurs with the plain and the scalar additive readings when the focus is on the verbal complex (15), or with the indeed-reading (14e).

| local discourse context: | ||||||

| Péter vett egy facsemetét. | ||||||

| ‘Peter bought a sapling tree.’ | ||||||

| És | (Péter) | el | is | ültette | (a | facsemeté-t). |

| and | (Peter) | vprt | also | planted | (the | sapling.tree-acc) |

| ‘And he/Peter planted it/the sapling tree, too.’ | ||||||

The scalar additive reading (even) is expressed with the construction még X is ‘yet X also’ (14b), where még is not obligatory. Hence, in certain cases, the surface construction of the plain and scalar additive readings can be the same.

A special construction with reiterated is with an optional conjunction (és ‘and’, meg ‘plus’) is used for the coordination of constituents (14c) or verbs/verbal complexes (16). In this construction, the additive particle can be attached to the constituents, to the verbs or to the verbal particles in the coordination. This reading is restricted to this special construction with a reiterated is-phrase.

| Péter | is, | Anna | is | el-ment | a | fogadás-ra. |

| Peter | also | Anna | also | vprt-went | the | reception-sub |

| ‘Peter and Anna (both) went to the reception.’ | ||||||

| Péter | evett | is, | ivott | is | a | fogadás-on. |

| Peter | ate | also | drank | also | the | reception-sup |

| ‘Peter (both) ate and drank at the reception.’ | ||||||

| Péter | meg | is | vacsorázott, | le | is | feküdt, | mire | Bea hazaért. |

| Peter | vprt | also | dined | vprt | also | lay | by.when | Bea got.home |

| ‘Peter had dinner and went to bed by the time Bea got home.’ | ||||||||

Similarly to coordination, the additive particle can be used to mark the last element of a list (14d). In this construction, only the last element of the list is followed by is. Furthermore, as usual in listing constructions, coordination is overtly expressed, at least before the last element.

And finally, (14e) illustrates a special ‘indeed’-reading. For this reading, the particle can again attach to either a constituent or to a verb/verbal complex. In the latter case, the additive particle cliticizes to the verb or to the verbal particle, as before. This surface order is the same as in plain or scalar additive readings where the focus is on the verb.

| Jani | meg | akarta | hív-ni | Vili-t | a | fogadás-ra. | |

| John | vprt | wanted | invite-inf | Bill-acc | the | reception-sub | |

| John wanted to invite Bill to the reception. | |||||||

| És | Jani | meg | is | hívta | Vili-t | a | fogadás-ra. |

| and | John | vprt | also | invited | Bill-acc | the | reception-sub |

| ‘And John indeed invited Bill to the reception.’ | |||||||

With the same interpretation, the additive particle can also attach to a constituent. In this case, however, the host occupies the immediate preverbal position,[15] which goes against previous claims (e.g., É. Kiss 2004; Szabolcsi 1997).

| Jani | Vili-t | akarta | meg-hív-ni | a | fogadás-ra. | ||

| John | Bill-acc | wanted | vprt-invite-inf | the | reception-sub | ||

| It was Bill whom John wanted to invite to the reception. | |||||||

| És | Jani | Vili-t | is | hívta | meg | a | fogadás-ra. |

| and | John | Bill-acc | also | invited | vprt | the | reception-sub |

| ‘And indeed it was Bill whom John invited to the reception.’ | |||||||

Note that the availability of this particular reading is restricted to contexts where the identificational focus is already present, hence the host of is in the target sentence is a second occurrence focus. The reading of the second sentence in (18) receives the interpretation where the semantic associate of the additive particle is the whole sentence, including identificational focus:

| also [it was Bill whom John invited to the reception] |

We presume that this reading also expresses additivity and can be considered focus sensitive in the pragmatic sense. However, its focus sensitivity needs to be captured differently, presumably at a different level of semantic analysis.[16] In the Hungarian National Corpus, we can find various examples where the is-phrase appears in the immediate preverbal slot, seemingly occupying the structural focus position. However, further investigation must ascertain whether these examples actually involve a focus position or not. In many cases, these sentences have a progressive aspect or another reading that triggers the inversion of the verb and particle rather than a filled focus position.

To sum up the constructional observations above, Tables 1 and 2 summarize the surface constructions of the different readings under consideration. As for the syntactic host of the additive particle we find the following possibilities:

Readings and constructions with a constituent host.

| Reading | Construction (constituent host) | |

|---|---|---|

| No focus position | Focus position | |

| also, too | XP=is (vprt)-V | – |

| even | (még) XP=is (vprt)-V | – |

| indeed | – | XP=is V (vprt) |

| coordination | XP=is (and) XP=is | – |

| listing | XP, (XP*) and XP=is | – |

Readings and constructions with a verb host.

| Reading | Construction (verb host) | |

|---|---|---|

| No particle verb | Particle verb | |

| also, too | V=is | vprt=is V |

| even | (még) V=is | (még) vprt=is V |

| indeed | V=is | vprt=is V |

| coordination | V=is (and) V=is | vprt=is V (and) vprt=is V |

| listing | V, (V)* and V=is | vprt-V, (vprt-V)* and vprt=is V |

| a. | constituent: (még) XP is |

| b. | verb without particle: (még) V is |

| c. | particle verb: (még) VPRT is V |

In Section 4, we will examine the prosodic pattern of these various uses and constructions in order to support a uniform focus sensitive analysis of the Hungarian additive particle is.

3 Previous prosodic studies on Hungarian

The main aim of this article is to investigate the prosodic patterns of the above readings and constructions in order to provide a basis for and to complement contemporary focus sensitive semantic analyses of is. The principal questions of our discussion are: (i) What is the relation of the prosodic structure of the utterances and their information structure in terms of focus marking? and (ii) How can/should the focus domain, i.e., the range of focus, be determined?

In Section 4, we will discuss our data and findings in detail. Prior to that, in Sections 3.1 and 3.2, we summarize our basic assumptions on prosodic phrasing and stress in Hungarian, as proposed by prominent works on Hungarian prosody (Hamlaoui and Szendrői 2015; Kálmán et al. 1986; Kálmán and Nádasdy 1994; Kenesei 1998; Szendrői 2001, 2003; Varga 2002). As will be shown, one of the main difficulties of the investigation and discussion of prosodic issues in Hungarian is that certain aspects of prosodic and phonological phrasing are still debated. Nevertheless, as a starting point of the discussion of our findings, we take the points from the literature on which there is substantial agreement.

3.1 Stress in Hungarian

Analyses of Hungarian generally make a difference between neutral and non-neutral (focused or corrective) sentences which differ not only in their syntax but also in their characteristic prosodic patterns (see, e.g., Kálmán 1985a, 1985b; Kálmán et al. 1986; Kálmán and Nádasdy 1994; Kenesei 1998).

Neutral sentences, i.e., level prosody sentences (Kálmán et al. 1986), do not have a single prominent stress or pitch accent, but equal main stresses on every lexical word in the sentence. The intensity of these main stresses declines during the sentence, which is called downdrift (in Hungarian, see Kenesei 1998; Varga 2002). At the beginning of a new intonational phrase the intensity of the main stresses steps up again, but does not reach the same height as the first main stress of the utterance (Varga 2002). By the notion ‘neutral sentence’ it is common to refer to sentences without a preverbal focus constituent. Figure 1 shows Kálmán et al.’s (1986) schematic representation of the prosodic pattern of a neutral sentence. They divide the sentence into a preparatory section containing the topic and certain adjuncts and an essential section containing the ‘hocus’ position,[17] the verb and its postverbal arguments.

Prosodic scheme of a neutral sentence (Kálmán et al. 1986: 131).

In non-neutral sentences, one or more lexical words are main-stressed, while the others are deaccented. Figure 2 shows the schematic representation of the prosodic pattern of a non-neutral sentence with a single pitch accent on the focus position. Again, the sentence is divided into a preparatory section and an essential section starting with the pitch accent.

Prosodic scheme of a non-neutral sentence (Kálmán et al. 1986: 130).

It is widely accepted that non-neutral sentences with a single main stress have a narrow (identificational) focus interpretation of the stressed element (see, e.g., Varga 2002). For example, in (21) the main stress is on Mari-t, which occupies the preverbal focus position interpreted as contrastive/identificational focus.[18]

| ′Péter | ′Mari-t | várta | meg | a | klubban. |

| Peter-nom | Mary-acc | wait-ed | pref | the | club-in. |

| ‘It was Mary that Peter waited for at the club.’ | |||||

| (Kálmán et al. 1986: 130) | |||||

In these kind of sentences, the intensity of the pitch accent does not have to be stronger than a normal main stress, but the lexical words after the pitch accent are deaccented.[19] Even though the single pitch accent most often falls on the designated focus position in front of the verb, Kálmán (1985b) claims that this pre-verbal main stress can also fall, for example, on a quantifier or an is-phrase that cannot occupy this position. According to Kenesei (1998), elements preceding the focus (e.g., topic) keep their unreduced stresses because they form their own phonological phrase while elements between the focus and the verb (including the verb) are fully destressed.

Non-neutral sentences with multiple main stresses can either express that multiple constituents are contrasted or that they are new information and thus the sentence gets a broad focus interpretation (Kálmán 1985b; Varga 2002). According to Varga (2002) and Kenesei (1998), the only exception to this rule is that verbs are deaccented if the focus position is filled even if they are new information and part of the focus domain. As with the non-neutral sentences with a single main stress, the differences in intensity of the main accents do not play a role. Example (22c) illustrates multiple main stresses in a non-neutral sentence. The only difference between (22a), (22b) and (22c) is that mindig ‘always’ is new information in (22c) and thus accented.

| ′Kati | is | mindig | írt | Péter-nek. |

| Kati | also | always | wrote | Peter-dat |

| ′Kati | is | írt | Péter-nek | mindig. |

| Kati | also | wrote | Peter-dat | always |

| ′Kati | is | írt | Péter-nek | ′mindig. |

| Kati | also | wrote | Peter-dat | always |

| ‘Kati, too, always wrote to Peter.’ | ||||

| (Kálmán 1985b: 33 [the glosses are ours]) | ||||

3.2 Syntax-prosody mapping in Hungarian

Building upon previous work by Reinhart (1995, 2006) and Szendrői (2001, 2003), Hamlaoui and Szendrői (2015) propose a crosslinguistically applicable approach to the mapping of syntax and prosody. As widely accepted in contemporary phonological theory (e.g., Nespor and Vogel 1986; Selkirk 2011), speech is considered to be built up from hierarchically organized phonological domains: phonological words (ω), phonological phrases (φ) and intonational phrases (ι). Hamlaoui and Szendrői (2015) argue that while it is widely accepted that phonological words and phonological phrases are based on clear syntactic domains (mostly lexical XPs), identifying the basis for intonational phrases has been rather problematic. For the clause-level mapping of syntax and phonology, Hamlaoui and Szendrői (2015) propose six constraints, four of which determine the mapping from syntax to prosody and two of which the mapping from prosody to syntax. Based on these constraints, they predict that elements in a specifier position with accompanying verb movement will be within the core ι (23a), while elements occurring in a left-peripheral position without verb movement will prosodically be outside the core ι (23b) but still inside an outer ι containing the core ι. Hence, recursive intonational phrases are possible. The phrasing in (23a) occurs, for example, in Hungarian preverbal focus constructions, English wh-questions, as well as in German V2 clauses. The phrasing in (23b) occurs, for example, with the Hungarian topic position.

| a. | (XP j V i …t i … t j ) ι |

| b. | (XP i … (V … t i ) ι ) ι |

Beside the mapping rules, ranked stress-alignment constraints are also defined as given in (24). In Hungarian, the ranking of these constraints is Stress-ι ≫ EndRule-L ≫ EndRule-R.

| a. | Stress-ι: Every ι has a stressed phonological phrase. |

| b. | EndRule-L: Main stress is on the leftmost phonological phrase of ι. |

| c. | EndRule-R: Main stress is on the rightmost phonological phrase of ι. |

Given these constraints together with the ‘Stress-Focus Correspondence Principle’ (25), the phrasing of neutral and non-neutral sentences in Hungarian can be derived uniformly.

| Stress-Focus Correspondence Principle: |

| The focus of a clause is a(ny) constituent containing the main stress of the intonational phrase, as determined by the stress rule. |

| (Szendrői 2003: 47, based on Reinhart 1995 and 2006) |

Neutral sentences, i.e., without preverbal (identificational) focus, can be V-initial, expressing all-new or out-of-blue content, or they can contain left-peripherical topic constituents. This position is often referred to as the ‘topic position’ in Hungarian. The topic position can also be iterated.

| ( | )ι | |||

| [El-ütötte i [t i | az | igazgató-t | egy autó] VP | ] PredP |

| vprt-hit | the | director-acc | a | car |

| ‘A car hit the director.’ | ||||

| ( | ( | )ι | )ι | ||

| [az igazgató-t k | [el-ütötte i [t i t k | egy | autó] VP | ] PredP | ] TP |

| the director-acc | vprt-hit | a | car | ||

| ‘A car hit the director.’ | |||||

| ( | ( | )ι | )ι | |

| [az igazgató-t k | [egy autó j | [el-ütötte i [t i t j t k ] VP | ] PredP ] TP | ] TP |

| the director-acc | a car | vprt-hit | ||

| ‘A car hit the director.’ | ||||

| (following Hamlaoui and Szendrői 2015) | ||||

In neutral sentences, all phonological phrases (φs) are stressed, carrying pitch accents. The verbal particle and the verb form one morphological unit, its own phonological phrase (φ), and the unit bears φ-level accent. Following Szendrői (2001), the verbal complex (vprt-V) carries the main stress of the sentence.[20] The φ of the verbal complex is located at the left edge of the intonational phrase (ι).

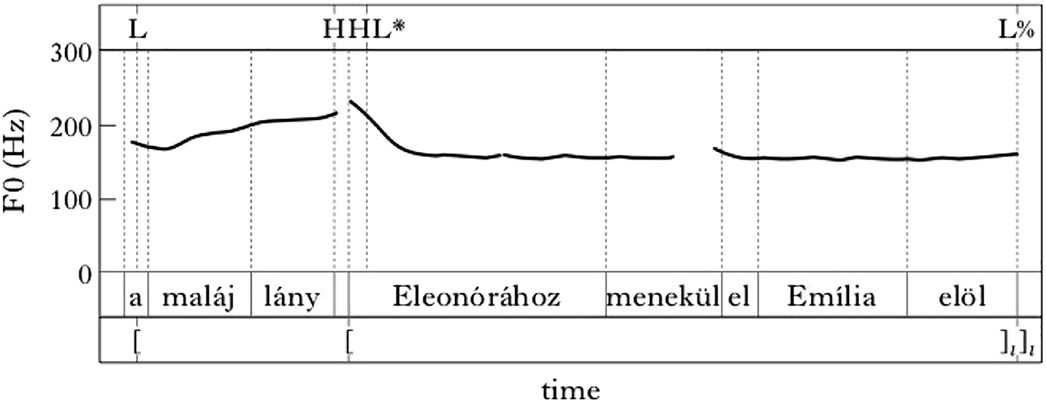

Non-neutral sentences with a filled preverbal focus position have a distinguished prosodic pattern, as illustrated in (27a).

| A | maláj | lány | Eleonórához | menekül | el | Emília | elöl. |

| the | Malay | girl | Eleonora-to | flees | away | Emilia | from |

| ‘The Malay girl escapes from Emilia to Eleonora.’ | |||||||

| (

|

|||||||

| ([A | maláj | lány k | ([Eleonórá-hoz j | menekül i | [el | [t i t j t k |

| the | Malay | girl | Eleonora-to | flees | away | |

| Emília | elöl] VP ] PrP ] FP ] TP ) ι ) ι | |||||

| Emilia | from | |||||

| (following Hamlaoui and Szendrői 2015) | ||||||

In non-neutral sentences with preverbal focus, the main stress falls on the focused constituent and post focal elements undergo stress reduction, indicating given information (see also Varga 2002). As the syntax-prosody mapping in (27b) shows, the focused constituent, and hence the main accent, occurs at the left-edge of the intonational phrase.

As illustrated above, in narrow focus constructions (with identificational semantics), the focused constituent bears an eradicating stress (Kálmán et al. 1986), where everything behind is destressed indicating given information status. Focus projection with the preverbal focus construction is only available with a distinguished intonation pattern, as shown by Kenesei (2006), with accents appearing after the constituent in the preverbal focus position. Based on these observations (and the syntactic properties discussed before), we hypothesize that focus marking in sentences with is ‘also, too’ is prosodic, where (a) the main accent falls on the syntactic host of the particle and (b) the prosodic pattern after the is-phrase indicates the range of focus (narrow, predicate or sentence). In the following section, we discuss our prosodic study of various uses of the particle is and investigate whether our hypothesis is correct and appropriate for all cases.

4 Data and prosodic patterns

In the following, we present the findings of a prosodic study of Hungarian sentences containing the additive particle is. The outcome of our investigation provides the necessary prosodic evidence for the focus-based analysis of the Hungarian additive particle (e.g., Balogh 2021; Szabolcsi 2017, 2018).

The core data of our study consist of spoken narratives acquired by guided elicitations. We recorded 18 short stories based on 6 picture books, often referred to as the ‘Frog Stories’ (Mayer 1967, 1969, 1973, 1974; Mayer and Mayer 1971, 1975), and elicited data based on materials from the Questionnaire on information structure (QUIS) (Skopeteas et al. 2006). The picture books of the ‘Frog Stories’ each tell a different story using exclusively pictures/illustrations, but no words. All data are narrated by monolingual native speakers of Hungarian between the ages of 22 and 53. In the collection of texts we found and analyzed 192 occurrences of the additive particle is. Other additive markers (e.g., szintén ‘as well’) occur sporadically, but these are not subject to this particular study.

4.1 Plain additive use

First we discuss the use of is as a plain additive particle (=also, too). Consider Example (28), presented together with its local discourse context.

| local discourse context: Így aztán dühösen ült egy kövön és várta, hogy mi lesz ebből az egészből. | |||||||

| ‘So, he (=frog) sat angrily on a stone and waited for what would come out of all this.’ | |||||||

| [A | kisfiú]SA | is | elég | dühös | volt | már | eddigre, |

| the | boy | also | rather | angry | was | already | by.then |

| ‘The boy was also pretty angry by then,’ | |||||||

The local discourse context contains the information that the frog is angry, hence the context suggests a narrow semantic associate of the particle. The additive presupposition/requirement that ‘someone different from the boy was angry’ is directly fulfilled. According to our hypothesis, we predict that with this interpretation the syntactic host of the particle bears the main stress and everything following it is destressed. This prediction is borne out:

| prosodic pattern of the target sentence in (28): |

|

As predicted, the prosodic pattern above shows that the host (a kisfiú ‘the boy’) of the additive particle bears the main accent (H*) of the sentence while none of the constituents after the is-phrase are accented.

Now take another example, presented in the clauses in (30a) and (30b) together with their immediate context.

| local discourse context: A pincér éppen próbálja felvenni a rendelést, amikor a béka úgy dönt, hogy körülnéz, hol is van pontosan, így aztán kiugrik a kisfiú zsebéből. Egyenesen bele a szaxofonos szaxofonjába, aki fújja, fújja, fújja, és nem érti, hogy miért nem jön ki a hang a szaxofonból. Megpróbálja megrázogatni a hangszert, hogy mi történhetett vele, az előbb még szólt, most pedig baja van. |

| ‘The waiter is trying to take the order when the frog decides to look around to see where he is exactly, so he jumps out of the little boy’s pocket. Directly into the saxophone of the saxophonist who is just blowing, blowing, blowing and does not understand why no sound is coming out of the saxophone. He is trying to shake the instrument to see what happened to it. It was working before and now it is broken.’ |

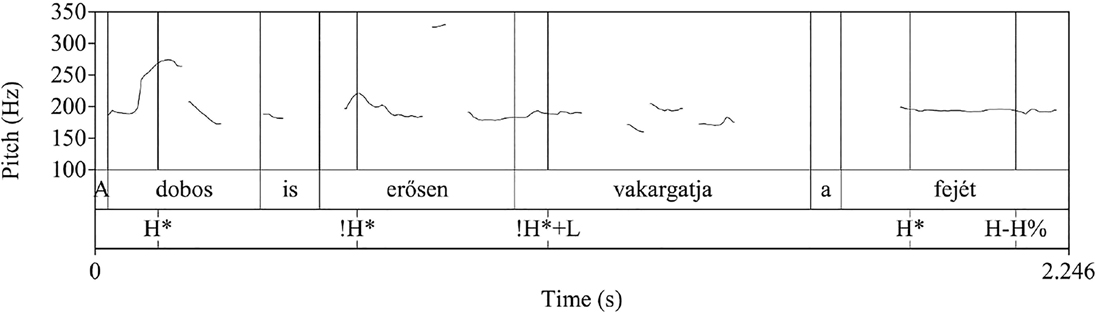

| [A | dobos | is | er˝osen | vakargat-ja | a | fej-é-t]SA, |

| the | drummer | also | heavily | scratch-3sg.def | the | head-3sg.ps-acc |

| ‘The drummer is heavily scratching his head, too,’ | ||||||

| [a | trombitás | is | nézi, | hogy | mi | történ-het-ett]SA. |

| the | trumpeter | also | looks | that | what | happen-mod-pst |

| ‘(and) the trumpeter is also looking to see what happened.’ | ||||||

The context suggests a broad focus interpretation in both (30a) and (30b), with a semantic associate that includes the whole sentence/the whole proposition. The additive presupposition/requirement of the broad interpretation is satisfied in both sentences, i.e., something different from ‘the drummer scratched his head’ happened before (for 30a) and something different from ‘the trumpeter was looking to see what happened’ (for 30b) was the case before: the context provides the information that ‘that saxofonist shook his instrument’. This is considered as an element of an elaboration list of the reactions of musicians after the frog jumped into the saxophone. The context does not contain the information that ‘someone different from the drummer is scratching his head’ or ‘someone different from the trumpeter is looking to see what happened’, which would license a narrow interpretation.

By our hypothesis, we expect that this broad semantic associate in (30a) and (30b) is marked prosodically, by accent placement after the is-phrase as well. Again, this prediction is borne out:

| prosodic pattern of (30a): |

|

| prosodic pattern of (30b): |

|

In Examples in (30a) and (30b), similarly to the Example (28), the main accent falls on the syntactic host of the particle: a dobos ‘the drummer’ and a trombitás ‘the trumpeter’ respectively. However, the stress pattern of the constituents following the is-phrase is different from that of a narrow focus reading. In (30a) every element after the is-phrase bears neutral stress. This indicates that the content of these elements is considered new information, hence not presupposed. Example (30b) is prosodically somewhat less clear-cut, since it contains a subordinate clause. However, the verb is accented here, which indicates again that it is not presupposed.

In our data, we found a significant number of examples with a broad focus reading, where all elements after the is-phrase, including the verb, bear accents. This finding is contrary to the claims that even in broad focus readings the verb is deaccented (Varga 2002) and that elements between the verb and the focus are destressed (Kenesei 1998). To settle this particular issue we need further prosodic investigations on a larger amount of data.

The narrow and broad semantic associate reading is also available in sentences where the additive particle is attached to the verb. The narrow interpretation corresponds to a focused verb with deaccented postverbal elements. In a broad focus interpretation (predicate focus or sentence focus), on the other hand, postverbal constituents receive stress, as before. Consider Example (32).

| local discourse context: [the turtle causes all kinds of trouble] A kisfiú sem tudta hirtelen, mi történt. De aztán, amikor meglátta, hogy mi történt, hogy megint csak a teknősbéka az, | |||||||

| ‘The boy did not know what had happened either. But when he saw what had happened, that it was the turtle again,’ | |||||||

| és | bele | is | húzta | a | kutyá-t | a | víz-be, |

| and | vprt | also | pulled | the | dog-acc | the | water-ill |

| ‘and he(=turtle) also pulled the dog into the water’ | |||||||

|

|||||||

Based on the prosodic patterns in our data we can generalize that the focus in is-constructions bears the main accent of the sentence. When the semantic associate is narrow, the elements after the is-phrase are deaccented, indicating that their information is given, and with a broad semantic associate they receive an accent, indicating that their information is new (or non-given). There are, however, some examples in our data that seem to show a mismatch between the prosody and the context. Take, for example, sentence (33).

| local discourse context: A kutya szegény alig tudott menni a szomorúságtól, | |||||

| ‘The poor dog could hardly walk from sadness,’ | |||||

| a | béka | is | csak | kullogott | utánuk. |

| the | frog | also | only | lag | behind.3pl |

| ‘the frog, too, was just lagging behind them.’ | |||||

|

|||||

At first sight, the context contains the information that someone other than the dog is lagging, given the semantic similarities of the verb lag and the expression walk sadly. Thus, only looking at the context, one could derive a reading with a narrow semantic associate. However, the prosody clearly indicates a broad associate, since the verb and the adverb behind the is-phrase both bear an accent. This can be explained if we look at the lexical semantics of the two verbs. The verb kullog ‘lag’ includes a manner component, which is missing in the expression in the preceding sentence. This meaning component is non-given, therefore we can argue that the verb kullog ‘lag’ expresses new information, hence confirming a broad focus reading. Another example of a possible mismatch is given in (34):

| local discourse context: A béka rémülten úszott utánuk, hogy vajon most mi történik, és aztán kimászva a szárazföldre mindenki úgy gondolta, hogy na most végre megkönnyebbülhetünk, és pihenhetünk együtt. | |||

| ‘The frog was swimming frightened after them, wondering what was happening now, and when the others climbed out onto the shore, they were all thinking: well, finally we can be relieved and rest together.’ | |||

| A | béka | is | ki-mászott, |

| the | frog | also | vprt-climbed |

| ‘The frog, too, climbed out’ | |||

|

|||

In this example, the context indicates even more strongly that ‘someone different from the frog climbed out’, given that the same verb is used in the target sentence and in the immediately preceding sentence. However, as before, the prosodic pattern shows a broad focus interpretation: the verbal complex ki-mászott ‘vprt out -climbed (= climbed out)’ is stressed in the target clause. A possible explanation for this example is that for the correct interpretation, which is indicated in the prosody, we need to look over the clause boundary in the target sentence see (35).

| A | béka | is | [ki-mászott, | és | próbált | csatlakoz-ni | a | csapat-hoz]SA. |

| the | frog | also | vprt-climbed | and | tried | join-inf | the | group-all |

| ‘The frog, too, climbed out and tried to join the group.’ | ||||||||

|

||||||||

The predication about the frog is more complex than simply ‘climbed out’, it should be taken as ‘climbed out and by this tried to join the others’, where the reason relation is crucial. This complex predication is taken as the semantic associate of the additive particle, so we can argue for a broad focus reading again, which is marked in the prosody.

4.2 Scalar additive use

Sentences with a scalar additive reading exhibit similar prosodic patterns with regard to the relation between the range of focus (i.e., the focus domain) and (de)accenting of the constituents after the is-phrase. Various instances in our data support the claim that with the scalar additive reading (= even reading) the broad semantic associate is also available. Take, for example, sentence (36) below.

| local discourse context: Egy hirtelen mozdulattal a béka újra lerúgja a kisbékát a tutajról, aki egy nagy placcsal beleesik a vízbe. | |||||||

| ‘With a sudden movement, the frog kicks the little frog off the raft again, who falls into the water with a big splash.’ | |||||||

| És | a | béka | még | a | nyelv-é-t | is | ki-nyújtja, |

| and | the | frog | yet | the | tongue-3sg.ps-acc | also | vprt-streches |

| ‘And the frog even stretches his tongue out,’ | |||||||

|

|||||||

Both the prosodic pattern and the context of (36) indicate a broad focus interpretation. In the context, it is described that the frog is annoyed that there is a new little frog in the family. Different actions of the frog against the little frog are mentioned and it is not presupposed that anything else was stretched out. As shown in the figure above, the verbal complex after the is-phrase also receives an accent, indicating its non-presupposed status. The relation of the prosodic pattern and the reach of the focus domain as illustrated above can also be shown in multi-word expression (or metaphoric expressions). Take, for example, the sentence in (37).

| local discourse context: [the frog ate a bee instead of a mosquito] Azt hiszi, hogy egy jó kis szúnyog, ami vacsorára vagy ebédre neki nagyon jól fog esni, de aztán nagyon meglepődik, amikor valami hatalmas dolog történik belül, | |||||

| ‘He(=frog) thinks that it is a mosquito, that will be great for lunch or dinner, but he is very surprised, when something happens inside his mouth,’ | |||||

| mert | még | [a | szem-e | is | ki-gúvadt] SA |

| and | yet | the | eye-3sg.ps | also | vprt-goggled |

| ‘because he was even looking with goggled eyes.’ | |||||

|

|||||

Example (37) contains the multi-word/metaphoric expression kigúvad a szeme ‘is very surprised [lit. his eyes are goggled]’. Given that the noun and the verb form a multi-word expression, the sentence cannot be interpreted with a narrow associate of the additive particle. This is confirmed by the prosodic pattern, suggesting that the verbal complex is part of the focus domain. The sentence with deaccenting after the particle is odd.

In Sections 4.1 and 4.2, we provided prosodic evidence for a focus sensitive analysis of two basic uses of the particle is: the plain additive and the scalar additive use. We found that the syntactic host of the additive particle generally bears the main accent of the clause, hence, following Szendrői (2001, 2003) and Hamlaoui and Szendrői (2015), it marks the left edge of the focus domain of the sentence. We show that differences in the prosodic pattern after the is-phrase are closely related to the range of the focus domain, suggesting either a narrow or a broad focus interpretation. In narrow focus readings, the constituents after the is-phrase are deaccented, indicating that the information they carry is presupposed. On the other hand, in the broad focus interpretation, the constituents after the is-phrase retain their accents, indicating that the information is not presupposed. In the coming sections, we discuss further uses of the particle is and investigate whether and how the prosody of these cases supports a uniform focus-based analysis.

4.3 Coordination and listing

The next constructions we look at in this section are the iterated is-phrase expressing coordination (38) and listing (39).

| A | kisfiú | is, | ő | is | ki-hajolt-ak | az | ablak-on. | (=14c) |

| the | boy | also, | he | also | vprt-leaned-3pl | the | window-sup | |

| ‘The boy and he(=the dog) both leaned out of the window.’ | ||||||||

| A | kutya | is, | a | gazdá-ja | is | szólongat-ja | a | béká-t, |

| the | dog | also | the | owner-3sg.ps | also | call-3sg.def | the | frog-acc |

| ‘The dog and his owner are both calling the frog,’ | ||||||||

| egy | kutya, | egy | béka | és | egy | teknősbéka | is, | kíváncsian | várja, | (=14d) |

| a | dog | a | frog | and | a | turtle | also | curiously | wait | |

| ‘a dog, a frog and a turtle, are waiting curiously,’ | ||||||||||

These constructions are unfortunately much less frequent in our data,[21] so further prosodic investigations are needed that concentrate on these particular uses. The two constructions are grouped together here, based on a common property of their prosodic patterns, namely that they have a special intonation contour with boundary tones (H-H%) after each item, which is a characteristic pattern for listing.

| prosodic pattern of (39)/(14d): |

|

Although we group the two readings together here, there are important structural differences between them that provide a reasonable ground for a distinction. In the coordination construction (e.g., Example 38), the use of és ‘and’ or meg ‘plus’ is optional, while the use of is ‘also’ is obligatory at each conjunct. In the listing construction (e.g., Example 39) on the other hand, the use of és ‘and’ is not optional and is ‘also’ can only appear at the last element of the list.[22] A list can also have two elements (such examples occur more in our data), which is very similar to the coordination use, but based on the above criteria we can make the necessary distinction.

The interpretation of the construction expressing coordination is discussed by Brasoveanu and Szabolcsi (2013) and Szabolcsi (2017, 2018) in a crosslinguistic setting. They propose a dynamic semantic approach, based on Kobuchi-Philip’s (2009) analysis where the two particles mutually satisfy their additive presupposition and Brasoveanu’s (2013) notion of ‘post-supposition’. What is relevant for our discussion is that their analysis is based on the claim that the particle is is uniformly focus sensitive, and both syntactic hosts in this construction are focal. Without showing the prosodic patterns, Szabolcsi (2018) posits that both syntactic hosts are focal, and bear a focus accent. The analysis of the prosodic patterns of this construction in our data confirms that each syntactic host bears a pitch accent.

| prosodic pattern of (38a): |

|

| prosodic pattern of (38b): |

|

In our proposal, however, not only the accent of the syntactic host but also the prosodic pattern after the is-phrase determines the focus. In this use of is, a broad semantic associate is possible, similarly to the plain and scalar additive uses.

| A | hó | is | esik, | a | szél | is | fúj, | a | gyerek | is | nyűgös. |

| the | snow | too | falls | the | wind | too | blows | the | child | too | cranky |

| ‘The snow is falling, likewise the wind is blowing, and likewise the child is cranky.’ | |||||||||||

| (from Szabolcsi 2018: 2, Ex. 2a) | |||||||||||

| A | szarvas | [dühös | is | volt]SA | és | [meg | is | ijedt]SA, |

| the | deer | angry | also | was | and | vprt | also | scared |

| ‘The deer was both angry and scared.’ | ||||||||

| (elicited data) | ||||||||

In our data, the variation of accenting/deaccenting after the is-phrases in the coordination use is neutralized, and is generally pronounced with the neutral stress pattern for both narrow and broad associates. This is problematic for our basic proposal on focus marking in this particular reading. We assume that the presence of the list intonation pattern plays a crucial role of the prosodic pattern here. However, we have too few sentences of this construction in our data, therefore we cannot draw hard conclusions on this particular issue. Further, directed experiments are necessary with regard to the prosody of this particular use of is.

To sum up our findings on the coordination use and listing, we found that in both constructions, (i) the syntactic host of the particle bears a pitch accent (high or low) and (ii) there is a special intonation contour specific to listing. Based on our findings, we can argue that the prosodic patterns partly support the semantic analysis by Brasoveanu and Szabolcsi (2013) and Szabolcsi (2017). The accent of the syntactic host can be related to focus marking, and the list intonation pattern can be related to the conjunction involved in the interpretation. This reflects the view of Szabolcsi (2017, 2018) in the interpretation of the coordination use, namely that is is responsible for the additive presupposition based on the focus semantics of its syntactic host, but not responsible for the conjunction. We see a similar division in the prosody, where accent on the host marks the focus as before, and the contribution of coordination, special for this construction, is marked by an additional list intonation contour, also only occurring in this particular use. The unresolved issue of the prosody after the is-phrase in this particular construction needs further investigation.

4.4 The ‘indeed’-reading

The last construction we discuss is the one that (to the best of our knowledge) has not been discussed before in the literature. As illustrated in (14e), the additive particle is can also be associated with a special interpretation, we call the ‘indeed-reading’, where additivity targets the intention or goal of the participant. With this reading, the semantic associate is broad, a full proposition, and the presupposition is that the proposition is true in an alternative world, representing the goal, wish or intention of an individual. Consider Example (14e) repeated here as (43):

| local discourse context: Úgy gondolta, hogy a fiú és a kiskutya lábnyomát követve elmegy hozzájuk. | ||||

| ‘He was thinking of going to their place, following the footsteps of the boy and the dog.’ | ||||

| [Meg | is | érkezett | a | lakás-uk-ba]SA. (=14e) |

| vprt | also | arrived | the | flat-3pl.ps-ill |

| ‘And indeed, he arrived in their place.’ | ||||

The semantic associate of is in (43) is the whole proposition ‘frog arrives in the flat’. This broad associate is reflected in the prosodic structure, the elements after the is-phrase retain their accents.

| prosodic pattern of (43): |

|

The syntactic structures of the sentences with the plain additive reading and the ‘indeed-reading’ are the same (see also Tables 1 and 2 before). We also found similar prosodic patterns to those in the plain/scalar additive use, hence the prosodic structure does not disambiguate between the ‘indeed’-reading and the others. The prosody only gives the information that the semantic associate must be broad (a sentence). The correct reading is derived based on the context that determines which possible presupposition is fulfilled.

As shown in Section 2.3.2, this special ‘indeed-reading’ is also available with a different linearization, licensed by a context where identificational focus is already present. Such examples were not present in our data set, so we recorded some constructed examples to investigate the prosodic structure in this construction, see (45), for example.

| local discourse context: A kisfiú a békát akarta elkapni a hálóval. | |||||||||

| ‘It was the frog that the boy wanted to catch with the net.’ | |||||||||

| És | a | kisfiú | a | béká-t | is | kapta | el | a | háló-val. |

| and | the | boy | the | frog-acc | also | caught | vprt | the | net-ins |

| ‘And, indeed, it was the frog that the boy caught with the net.’ | |||||||||

In the target sentence, the inverse order of the verb and the particle suggests that the particle is could associate with the structural focus, and that the whole is-phrase is in the immediate preverbal focus position.

| prosodic structure of (45): |

|

We argue, however, that the above structural analysis is incorrect. This construction only occurs with the special ‘indeed’-reading within a local discourse context where the preverbal/identificational focus (id-foc) is already present. The additive particle in (45) takes the sentence containing the preverbal/identificational focus as its semantic associate, not merely the constituent in the preverbal focus position (47). See also the discussion of Example (18) in Section 2.3.2.

| is (a kisfiú [a békát]ID–FOC kapta el a hálóval]) |

| also (it was [the frog]ID–FOC that the boy caught with the net) |

Based on its interpretation, we argue that it is not the whole is-phrase that is in the focus position, which needs to be represented in the syntactic structure. This challenging issue is left for further work.

5 Conclusions and outlook

In this article, we investigated the prosodic patterns in Hungarian sentences containing the additive particle is ‘also, too’ in its various uses and how the information structure in these uses determines the focus domain. We investigated data from spoken narratives collected through guided elicitations and discussed five distinct uses of the additive particle. We found clear prosodic evidence supporting a focus sensitive analysis of the additive particle is in Hungarian as proposed, for example, by Szabolcsi (2017, 2018) and Balogh (2021). The prosodic patterns provide a basis for analyzing the host of the particle as a focus rather than merely stating or stipulating focus sensitivity. Based on our findings, we need to acknowledge the importance of prosodic focus-marking in Hungarian, in particular the possibility of recognizing ‘information focus’ in the preverbal field.

Based on our prosodic findings, discussed in Section 4, we can generalize that in sentences with an is-phrase in the preverbal field, the syntactic host (the constituent it cliticized to) of the particle generally bears the main accent of the clause and marks the left edge of the focus domain. This is in line with the analysis of Szendrői (2001, 2003) and based on the Stress Rule for Hungarian and the Stress Focus Correspondence Principle (Reinhart 1995, 2006). The main accent falls on the leftmost phonological phrase of the intonational phrase (the is-phrase), and the focus aligns with this constituent containing the main accent. With these constraints, we can determine the beginning of the focus domain, which is left aligned with the intonational phrase in Hungarian.

Our analysis goes further, providing an extension to the relation of prosodic patterns and the range of the focus domain. As shown before, in its designated syntactic position in the preverbal field, the Hungarian additive particle can take both a narrow and a broad semantic associate, corresponding to the ‘pragmatic focus’ (Lambrecht 1994) of the utterance, which is reminiscent of ‘information focus’ as described by É. Kiss (1998). We argue that the stress patterns after the is-phrase disambiguate between narrow versus broad focus interpretations. In case of deaccenting after the is-phrase, the focus domain ends right before the first deaccented phonological phrase, and if the constituents after the is-phrase bear accents, then they are considered to be part of the focus domain. In order to determine the end of the focus domain, we propose an extension to the constraints by Hamlaoui and Szendrői (2015). The additional constraints in (48) determine the range of the focus domain.

| Focus sensitivity of the additive particle |

|

the additive particle is is cliticized to the first element of the focus domain; |

| the beginning of the focus domain is aligned with the leftmost phonological phrase within the intonational phrase; |

| the focus domain ends | |

| i. | before the first deaccented φ following the is, or |

| ii. | at the end of the intonational phrase. |

We argued, based on our data, that there is a clear correspondence between accent placement or deaccenting and the focus domain of the sentence. Deaccenting after the is-phrase corresponds to a narrow focus reading (narrow semantic associate of the particle) and accents after the is-phrase correspond to a broad focus (broad semantic associate of the particle). For the latter case, the focus domain can range over the whole proposition (sentence focus) or only over the predicate (predicate focus). With respect to the focus sensitivity of the additive particle, our main claim is that in the additive readings, deaccenting of the constituents behind the is-phrase marks their status as ‘given’, hence they are outside of the focus domain. Similarly, in the scalar additive reading, deaccenting/accenting determines whether unexpectedness is on the constituent (narrow) or on the event (broad). Our claim concerning the relation of the range of focus and prosodic structure (intonation contour) comes with the important theoretical consequence that both notions, focus by main accent and deaccenting, are necessary (as opposed to Wagner 2012).

As already pointed out above, there are important issues in our proposal that need further investigation. Our proposal above captures the empirical findings of the prosodic investigation of our data set. Next to the additional constraints we propose, we are currently working on the formal modeling of the prosody-syntax-semantics interface. A thorough introduction of this model goes beyond the scope and space limitations of this article, therefore, here we can merely indicate the approach we are working towards. We argue that the formalized version of Role and Reference Grammar [RRG] (Kallmeyer et al. 2013; Kallmeyer and Osswald 2017; Osswald and Kallmeyer 2018) with a compositional syntax-semantics interface provides the formalism for an elegant model of the interfaces in our analysis of is. The theoretical base in ‘classical’ RRG (Van Valin 2005; Van Valin and LaPolla 1997) is particularly suitable for interface analysis and modeling, as the interaction of syntax, semantics and pragmatics plays a primary role in its formal architecture and theoretical grounds. RRG does not assume the primacy of syntax, and the necessary pragmatic mechanisms are already present in the theory. The general architecture of RRG is modular, with various levels of representation (called ‘projections’) and well-defined linking relations between them. The center of the grammatical system of RRG is the bi-directional linking of syntax and semantics, capturing both language production and comprehension. This linking is influenced by information structure and prosody. A particularly important issue in the prosody-syntax interface is the order of the verb and the verbal particle, analyzed as verb movement in transformational generative approaches. Our data with additive particles showed similar prosodic patterns like sentences containing a structural focus position, immediately before the verb. We analyze these constructions in terms of different focus types. The crucial syntactic difference is that structural focus (‘identificational focus’) induces inversion of the verbal particle and verb, while the is-phrase (taken as the ‘pragmatic focus’ or ‘information focus’) does not. A proper analysis of the syntax-prosody interface needs to account for this structural difference.

Funding source: DFG Collaborative Research Center

Award Identifier / Grant number: Project D04

Acknowledgments

We would especially like to thank Kriszta Szendrői, Edgar Onea and the two anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments on our work and on the previous versions of this article, and Peter Sutton for proof reading the article. All remaining mistakes are ours.

-

Research funding: The research presented in this article was supported by the DFG Collaborative Research Center 991, project D04: ‘The role of information structure in sentence formation and construal: a frame-based approach’.

Abbreviations and glosses

- 1,2,3

-

first, second, third person

- acc

-

accusative case

- all

-

allative case

- comm

-

comment

- dat

-

dative case

- def

-

definite conjugation

- foc

-

focus (domain)

- FP

-

focus phrase

- id-foc

-

identificational focus

- ill

-

illative case

- inf

-

infinitive

- ins

-

instrumental case

- mod

-

modal

- nom

-

nominative case

- pl

-

plural

- PredP

-

predicative phrase

- ps

-

possessor

- pst

-

past tense

- sa

-

semantic associate

- sg

-

singular

- sub

-

sublative case

- sup

-

suppressive case

- top

-

topic

- TP

-

topic phrase

- VP

-

verbal phrase

- vprt

-

verbal particle

References

Arregi, Karlos. 2015. Focus projection theories. In Caroline Féry & Shinichiro Ishihara (eds.), The Oxford handbook of information structure, 185–202. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199642670.013.005Search in Google Scholar

Balogh, Kata. 2009. Theme with variations: A context-based analysis of focus (ILLC Dissertations Series DS-2009-07). Amsterdam: ILLC, University of Amsterdam dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

Balogh, Kata. 2021. Additive particle uses in Hungarian: A Role and Reference Grammar account. Studies in Language 45(2). 428–469. https://doi.org/10.1075/sl.19034.bal.Search in Google Scholar

Beaver, David I. & Brady Z. Clark. 2002. The proper treatments of focus sensitivity. In Line Mikkelsen & Christopher Potts (eds.), WCCFL 21: Proceedings of the 21st West Coast conference on formal linguistics, 15–28. Somerville, MA: Cascadilla Press.Search in Google Scholar

Beaver, David I. & Brady Z. Clark. 2008. Sense and sensitivity: How focus determines meaning (Explorations in Semantics). Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.10.1002/9781444304176Search in Google Scholar

Brasoveanu, Adrian. 2013. Modified numerals as post-suppositions. Journal of Semantics 30(2). 155–209. https://doi.org/10.1093/jos/ffs003.Search in Google Scholar

Brasoveanu, Adrian & Anna Szabolcsi. 2013. Quantifier particles and compositionality. In Maria Aloni, Michael Franke & Floris Roelofsen (eds.), The dynamic, inquisitive, and visionary life of φ, ?φ, and ◊φ. A festschrift for Jeroen Groenendijk, Martin Stokhof, and Frank Veltman. Amsterdam: ILLC, University of Amsterdam.Search in Google Scholar

Brody, Michael. 1990. Remarks on the order of elements in the Hungarian focus field. In Istvan Kenesei (ed.), Approaches to Hungarian, vol. 3, 95–123. Szeged: JATE Press.Search in Google Scholar

É. Kiss Katalin. 1978. A magyar mondatok egy szintaktikai modellje [A syntactic model of Hungarian sentences]. Nyelvtudományi Közlemények 80. 261–286.Search in Google Scholar

É. Kiss Katalin (ed.). 1995 Discourse configurational languages. New York & Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/oso/9780195088335.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

É. Kiss Katalin. 1998. Identificational focus versus information focus. Language 74. 245–273. https://doi.org/10.1353/lan.1998.0211.Search in Google Scholar

É. Kiss Katalin (ed.). 2004 The syntax of Hungarian. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Search in Google Scholar

É. Kiss Katalin. 2015. Discourse functions: The case of Hungarian. In Caroline Féry & Shinichiro Ishihara (eds.), The Oxford handbook of information structure, 663–685. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199642670.013.24Search in Google Scholar

Forker, Diana. 2016. Toward a typology for additive markers. Lingua 180. 69–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lingua.2016.03.008.Search in Google Scholar

Genzel, Susanne, Shinichiro Ishihara & Balázs Surányi. 2015. The prosodic expression of focus, contrast and givenness: A production study of Hungarian. Lingua 165. 183–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lingua.2014.07.010.Search in Google Scholar

Gyuris, Beáta. 2009. The semantics and pragmatics of the contrastive topic in Hungarian. Budapest: Lexica Ltd.Search in Google Scholar

Gyuris, Beáta. 2012. The information structure of Hungarian. In Manfred Krifka & Renate Musan (eds.), The expression of information structure, 159–186. Berlin & New York: Mouton de Gruyter.10.1515/9783110261608.159Search in Google Scholar

Halliday, Michael A. K. 1967. Intonation and grammar in British English. The Hague: Mouton de Gruyter.10.1515/9783111357447Search in Google Scholar

Hamlaoui, Fatima & Kriszta Szendrői. 2015. A flexible approach to the mapping of intonational phrases. Phonology 32. 79–110. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0952675715000056.Search in Google Scholar

Horváth Julia. 2007. Separating “focus movement” from focus. In Simin Karimi, Vida Samiian & Wendy K. Wilkins (eds.), Phrasal and clausal architecture, 108–145. Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins.10.1075/la.101.07horSearch in Google Scholar

Horváth, Julia. 2010. “Discourse-features”, syntactic displacement and the status of contrast. Lingua 120. 1346–1369.10.1016/j.lingua.2008.07.011Search in Google Scholar

Kallmeyer, Laura & Rainer Osswald. 2017. Combining predicate-argument structure and operator projection: Clause structure in Role and Reference Grammar. In Marco Kuhlmann & Tatjana Scheffler (eds.), Proceedings of the 13th international workshop on tree adjoining grammars and related formalisms, 61–70. Umeå: ACL Anthology. https://aclanthology. org/W17-6200/.Search in Google Scholar

Kallmeyer, Laura, Rainer Osswald & Robert D. Van ValinJr. 2013. Tree wrapping for Role and Reference Grammar. In Glynn Morrill & Mark-Jan Nederhof (eds.), Proceedings of formal grammar 2012 and 2013, 175–190. Berlin & Heidelberg: Springer.10.1007/978-3-642-39998-5_11Search in Google Scholar

Kálmán, László. 1985a. Word order in neutral sentences. In István Kenesei (ed.), Approaches to Hungarian, vol. 1, 25–37. Szeged: JATE Press.Search in Google Scholar

Kálmán, László. 1985b. Word order in non-neutral sentences. In István Kenesei (ed.), Approaches to Hungarian, vol. 1, 13–23. Szeged: JATE Press.Search in Google Scholar