Abstract

The article investigates the hypothesis that prominence phenomena on different levels of linguistic structure are systematically related to each other. More specifically, it is hypothesized that prominence relations in morphosyntax reflect, and contribute to, prominence management in discourse. This hypothesis is empirically based on the phenomenon of agentivity clines, i.e. the observation that the relevance of agentivity features such as volition or sentience is variable across different constructions. While some constructions, including German DO-clefts, show a strong preference for highly agentive verbs, other constructions, including German basic active constructions, have no particular requirements regarding the agentivity of the verb, except that at least one agentivity feature should be present. Our hypothesis predicts that this variable relevance of agentivity features is related to the discourse constraints on the felicitous use of a given construction, which in turn, of course, requires an explicit statement of such constraints. We propose an original account of the discourse constraints on DO-clefts in German using the ‘Question Under Discussion’ framework. Here, we hypothesize that DO-clefts render prominent one implicit question from a set of alternative questions available at a particular point in the developing discourse. This then yields a prominent question-answer pair that changes the thematic structure of the discourse. We conclude with some observations on the possibility of relating morphosyntactic prominence (high agentivity) to discourse prominence (making a Question Under Discussion prominent by way of clefting).

1 Introduction

The notion of prominence plays a major role in the descriptive and theoretical investigation of linguistic phenomena on most levels of linguistic analysis, including phonology, morphosyntax and discourse. In contrast, the question of whether and how prominence phenomena on one level can be systematically related to prominence phenomena on another level is hardly ever studied.[1] This article investigates the question of how agent prominence in syntax and semantics relates to prominence management in discourse, using DO-clefts in German as its main example. DO-clefts are a particular subtype of WH-clefts that contain tun ‘do’ in the WH-clause and a clefted infinitive (see Example 1 below; see e.g. Jackendoff 2007 for this definition).

Agent prominence pertains to the fact that agentive arguments tend to be syntactically privileged arguments (e.g. in many languages, agents are linked to subject position per default and in most languages, agents occur before non-agentive arguments as a default). More specifically, our starting point is the observation that the acceptability of agents varies depending on the lexical class of the verb and the construction in which it occurs. When investigating the acceptability of a particular construction such as DO-clefts with transitive verbs, it turns out that the acceptability varies depending on which and how many agent features a given verb class entails for its agentive argument. Thus, as will be discussed in detail in Section 2.1, the verbs beobachten ‘observe’, hassen ‘hate’, and aufweisen ‘exhibit’ in (1) form what we call an agentivity cline (cf. Kretzschmar and Brilmayer 2020; Kretzschmar et al. 2019), with beobachten being perfectly acceptable, aufweisen being hardly acceptable and hassen falling in between the two.

| DO-clefts with transitive verbs in German (examples from Kretzschmar et al. 2019) | |

| a. | Was die Biologin tat, war die Zellmutation zu beobachten. |

| ‘What the biologist did was observe the cell mutation.’ | |

| b. | Was die Steuerzahlerin tat, war die Steuererhöhung zu hassen. |

| ‘What the taxpayer did was hate the tax increase.’ | |

| c. | Was der Kranke tat, war den Grippevirus aufzuweisen. |

| ‘What the sick person did was exhibit (symptoms of) the influenza virus.’ | |

Agentivity clines are predicted by the proto-role approach to semantic roles (Dowty 1991; Primus 1999, 2012), which assumes that verbs differ with regard to which role-semantic features[2] such as volition, sentience and motion they entail for their arguments. The different acceptability ratings of different verb classes in a particular syntactic construction, which are usually mirrored by significant frequency differences in corpora, can then be explained with reference to the fact that verbs like beobachten are more agentive than hassen because they entail volition, sentience and motion, while hassen only entails sentience (and aufweisen does not entail any of these agentivity features).

The central observation for the current argument pertains to the fact that the relevance of agentivity features changes across different syntactic constructions. For example, while the acceptability of the different verbs mentioned above varies when they occur in DO-clefts, no significant differences arise when they are used in basic active clauses (i.e. active clauses with initial subjects such as dass mehrere die Zellmutation beobachteten ‘that many observed the cell mutation’; cf. Kretzschmar et al. 2019). This indicates that syntactic constructions may have different restrictions with respect to agentivity features. If this is so, it immediately raises the question as to why the relevance of agentivity features varies across constructions. As entailments of the verbal meaning, one would expect them to be present and relevant whenever a particular verb is used. One would not want to claim that beobachten entails volition, sentience and motion only when used in a cleft construction and not when occurring in a basic active construction.

A hypothesis that suggests itself in this regard is the assumption that the variable relevance of agentivity features in different constructions reflects the different discourse conditions for these constructions. The basic idea can be illustrated with the example of imperatives. Imperatives typically express commands and related speech acts such as invitations (Come to our party! example from Fox 2015: 315) or exhortations (Mind the steps!). They are normally only felicitous in speech acts of this kind with verbs that denote eventualities that involve control by a volitional agent (Fox 2015: 315). However, imperatives are also used for wishes or expressions of hope such as Live long and prosper! (example from Fox 2015: 314), Welcome to our festival! and Be happy! In such uses, there is no agent restriction on the use of the imperative, i.e. they do not require that the verb entails a volitional agent (Fox 2015: 315). In the case of (English) imperatives, the presence of an agent restriction in imperatives therefore appears to be linked to one of their main discourse functions. In command-like speech acts, the use of imperatives is restricted to predicates entailing a volitional agent. In other speech acts, no such restriction exists. This suggests that the agent restriction is not part of the constructional meaning of imperatives per se. Instead, the agent restriction appears to be part of the semantics of command-like speech acts that imperatives typically, but not necessarily, convey.

The link between discourse function and agentivity constraints may appear to be straightforward in the case of imperatives. However, it is not immediately obvious that, and how, the finding that DO-clefts privilege predicates entailing a volitional, sentient and motional agent such as beobachten in (1) is linked to the discourse function(s) of DO-clefts. In fact, before bringing in discourse functions, it would appear to be much more straightforward to claim that the agentivity constraint on DO-clefts, i.e. their strong preference for predicates with a volitional, sentient and motional agent, is determined by the meaning of the lexeme tun ‘do’ in German. If tun were restricted to actions involving a volitional, sentient and motional agent, this would be the most parsimonious explanation for the agentivity constraint of DO-clefts. However, as also demonstrated in Section 2.3, the verb tun in German does not necessarily require the presence of all three agentive features when used in simple statements such as yes she did, where do refer anaphorically to a preceding predicate (e.g. Did the biologist observe the cell mutation? Yes, she did). In this usage context, volitional agents are not privileged vis-à-vis non-volitional agents. In the case of tun, we observe the same variable relevance of agentivity features as for other predicates. In some constructions such as DO-clefts, the co-occurrence of the three features volition, sentience and motion is strongly preferred; in others, it does not lead to enhanced acceptability.

Our main goal in this article is therefore to lend plausibility to the hypothesis that the variable relevance of semantic role features that can be observed across different uses of the same verb relates to the discourse context in which a particular verb is used. More specifically, we propose that the notion of prominence provides the major link between morphosyntactic and discourse structure in this regard. In its most general terms, our hypothesis is that prominence relations in morphosyntax reflect, and contribute to, prominence management in discourse. German DO-clefts will be our central example because here, the link between morphosyntactic structure and discourse use is far from obvious.

The variable relevance of semantic role features is an instance of a more general structuring principle in language that applies on the prosodic, morphosyntactic, semantic, and discourse levels. This structuring principle is based on the fact that it is possible to observe prominence distinctions between elements of equal type and structure on all these levels. Such prominence structures are defined by three criteria. Firstly, prominence is a relation that singles out one element from a set of elements of equal type and structure. Secondly, prominent units are structural attractors. Thirdly, prominence status shifts in time as discourse unfolds. These three criteria are further discussed and illustrated in Section 2.5. A fuller discussion which, importantly, also addresses issues of delimitation (e.g. distinguishing the prominence relation from prototypicality, the head-dependent relation, etc.) is found in Himmelmann and Primus (2015), García García et al. (2018), and von Heusinger and Schumacher (2019).

Our argument is structured as follows: In Section 2, we summarize previous experimental work showing the variable relevance of semantic role features across a number of constructions, i.e. basic actives, passives, DO-clefts and anaphoric tun. The basic observation here is that classes of verbs sharing the same role features (e.g. a class of verbs that entail volition and motion vs. a class of verbs that only entail motion for one of their arguments) differ in their acceptability across the different constructions mentioned above; that is, each of these constructions is associated with a different agentivity cline. In addition, we provide new evidence from a corpus analysis that shows converging evidence for agentivity-related role restrictions in DO-clefts. We argue further that agentivity clines are best understood as instances of morphosyntactic role prominence: in one construction, one set of role features is ranked higher than another set of role features but in another construction, the ranking may be different. Finally, we hypothesize that within this context, construction is a proxy for discourse context, i.e. the different clines are not, strictly speaking, linked to the construction with which they occur. Instead, it is the discourse context in which a particular construction typically occurs that is the source of the variable relevance of semantic role features (cf. the observation regarding the variable relevance of volition in imperative constructions above).

If the argument so far is accepted, the question naturally arises as to how a link between the discourse function of a construction and the variable relevance of its semantic role features can be conceived. In order to answer this question, it is necessary to clarify what we mean by ‘discourse function of a construction’. In Section 3, we tackle this issue by developing a proposal for the discourse function of DO-clefts, phrased in the ‘Question Under Discussion’ (QUD) framework. In a nutshell, the proposal is that WH-clefts in general make explicit, and thereby highlight, one of a number of possible QUDs available at a particular point in the ongoing discourse and change the thematic direction of the discourse. To be felicitous, such highlighting has to satisfy a number of constraints, and these constraints vary for different types of WH-clefts. For DO-clefts, for example, one important constraint is the requirement that the subject of the cleft is a highly agentive sentence topic.

Having established a discourse function for DO-clefts in Section 3, we return to the problem of linking discourse function and variable relevance of semantic role features in Section 4. At this point, we are not in a position to offer a fully worked-out account for such a link. Instead, our primary goal in this section will be to provide support for the hypothesis that the notion of prominence as an overarching organizing principle for linguistic structures is of central importance for such an account.

2 The variable relevance of semantic role features in German

This section briefly reports on the empirical phenomenon that provides the basis for the current investigation. It begins in Section 2.1 with a survey of experimental work by Kretzschmar and colleagues that reveals varying acceptability clines in different constructions. In Section 2.2, this experimental evidence is complemented by an as yet unpublished corpus study comprising 611 verbs used in 523 DO-clefts in the German Reference Corpus (Institute for the German Language 2018). Together, the experimental and corpus results suggest that the relevance of semantic role features varies across constructions. In Section 2.3, we demonstrate that the agentivity cline for DO-clefts cannot simply be explained by the meaning of the verb tun ‘do’, which is the defining constituent of the WH-clause of DO-clefts. Section 2.4 summarizes the empirical evidence for agentivity clines. In Section 2.5, we conclude by developing the hypothesis that the variable relevance of semantic role features seen in the clines can be explained by the notion of semantic role prominence, which links this variability to the discourse contexts in which the different constructions occur.

2.1 The variable relevance of semantic role features in German: acceptability judgments

As already mentioned in the introduction, the core observation of relevance to the present undertaking is the fact that different verb classes vary in their acceptability depending on which construction they occur in. This is shown in detail in a number of experimental studies by Kretzschmar and colleagues. Here we will summarize the experiments for DO-clefts with transitive and intransitive verbs (Kretzschmar and Brilmayer 2020; Kretzschmar et al. 2019) and the experiment for the active versus passive voice formed with transitive verbs (Kretzschmar et al. 2019). These experiments all adhere to the same basic design regarding the selection of verb classes so that we can compare experimental findings across constructions. Each study compares four or five verb classes, with each class represented by six verbs as illustrated in Table 1 for transitive verbs and Table 2 for intransitive verbs. The classes are defined on the basis of the role features a given verb entails for one of its arguments. In order to be able to clearly identify and accumulate agentive features, both studies used verbs entailing volition, motion and/or sentience in different combinations for the subject argument. The WATCH class in Table 1, for example, includes verbs that entail volition, sentience and motion for their subject argument. Moreover, to minimize effects stemming from referential properties of the arguments themselves, the subject argument was always definite and human. For transitive verbs, intervening patient effects were minimized as far as possible by testing verbs with a uniform low number of patient entailments for the object argument, which was always definite and inanimate (see Kretzschmar et al. 2019 for more details).

Transitive verb classes with agentive features and verb lexemes for each verb class as used by Kretzschmar et al. (2019).

| WATCH [volition, sentience, motion] | SEE [sentience] | HATE [sentience] | KNOW [sentience] | EXHIBIT [∅] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| beobachten ‘observe’ anschauen ‘look at’ betrachten ‘look at’ betasten ‘feel (by touching)’ beschnuppern ‘sniff at’ verfolgen ‘follow (with the senses)’ |

sehen ‘see’ hören ‘hear’ riechen ‘smell’ spüren ‘sense’ vernehmen ‘perceive’ wahrnehmen ‘perceive’ |

hassen ‘hate’ lieben ‘love’ mögen ‘like’ fürchten ‘fear’ verabscheuen ‘detest’ verachten ‘despise’ |

beherrschen ‘master’ erahnen ‘conjecture’ glauben ‘believe’ kennen ‘know’ vermuten ‘suppose’ wissen ‘know’ |

aufweisen ‘exhibit’ haben ‘have’ dabeihaben ‘have sth. on/with one’ dahaben ‘have here/there’ bekleiden ‘hold/be in a position’ innehaben ‘hold, occupy (a function)’ |

Intransitive verb classes with agentive features and verb lexemes for each verb class as used by Kretzschmar and Brilmayer (2020).

| WORK [volition, sentience, motion] | FEAR [sentience] | SWEAT [motion] | GLITTER [∅] |

|---|---|---|---|

| arbeiten ‘work’ tanzen ‘dance’ tratschen ‘gossip’ flüstern ‘whisper’ turnen ‘do gymnastics’ reden ‘talk’ |

bangen ‘fear’ trauern ‘mourn’ zweifeln ‘doubt’ leiden ‘suffer’ frieren ‘be cold’ staunen ‘be astonished’ |

schwitzen ‘sweat’ niesen ‘sneeze’ zittern ‘shiver’ husten ‘cough’ bluten ‘bleed’ stottern ‘stutter’ |

glitzern ‘glitter’ schimmern ‘glimmer’ stinken ‘stink’ müffeln ‘smell musty’ leuchten ‘glow’ glänzen ‘glisten’ |

Dowty (1991) postulates two superordinate proto-roles: proto-agent and proto-patient. The roles are composed of bundles of features entailed by the verb’s meaning and apply to one of the verb’s arguments. For the proto-agent role, Dowty lists the following five features that may occur in isolation or in combination (Dowty 1991: 572): the participant (i) acts volitionally, (ii) is sentient of or perceives another participant, (iii) causes “an event or change of state in another participant”, (iv) is moving autonomously, and (v) “exists independently of the event named by the” predicate. As the study design of Kretzschmar and colleagues focused on volition (i), sentience (ii), and autonomous movement (iv), we will only provide definitions for these three features. Note that proto-agent features are not defined by Dowty but rather illustrated and described by means of examples. Regarding volition, Dowty (1991: 552) states that a volitional agent acts volitionally and intentionally: “x does a volitional act, […] x moreover intends this to be the kind of act named by the verb”. Also, volitional agents are necessarily sentient (but not vice versa, Dowty 1991: 607). Movement qualifies as a proto-agent feature only when a participant moves autonomously using its own source of energy. When a participant’s movement is caused by another participant, movement is a proto-patient feature. Dowty (1991: 554, 607) assumes that movement covers a wide range of forms of a participant’s activity, including the subtle mental activity entailed by volitional perception verbs (e.g. look at) or verbs denoting bodily processes (e.g. bleed) that were tested in the experiments of Kretzschmar and colleagues. Therefore, we will use the more general term ‘motion’ in the following. A sentient agent is sentient of, i.e. able to perceive, mentally represent or evaluate, “the state or event denoted by the verb” (1991: 573). It occurs, inter alia, with subject experiencer verbs, i.e. emotion (e.g. fear), cognition (e.g. know) and perception (e.g. see) predicates (examples from Dowty 1991: 573).

Returning to the acceptability experiments, the target verbs were presented in sentence contexts such as the ones illustrated in Table 3 for DO-clefts with transitive verbs and in Table 4 for DO-clefts with intransitive verbs.

Examples of tested DO-clefts with transitive verbs in Kretzschmar et al. (2019).

| Transitive verb classes grouped by number of features | Example sentence for DO-clefts per verb class and its English translation |

|

|

|

| WATCH [volition, sentience, motion] | Was die Schaulustige tat, war die Mondlandung anzuschauen. ‘What the spectator did was watch the moon landing.’ |

| SEE [sentience] | Was die Gutachterin tat, war den Sturmschaden zu sehen. ‘What the insurance inspector did was see the storm damage.’ |

| HATE [sentience] | Was die Steuerzahlerin tat, war die Steuererhöhung zu hassen. ‘What the taxpayer did was hate the tax increase.’ |

| KNOW [sentience] | Was der Tropenarzt tat, war die Impfvorschrift zu kennen. ‘What the tropical medicine doctor did was know the vaccination rule.’ |

| EXHIBIT [∅] | Was der Kranke tat, war den Grippevirus aufzuweisen. ‘What the sick person did was exhibit (symptoms of) the influenza virus.’ |

Examples of tested DO-clefts with intransitive verbs in Kretzschmar and Brilmayer (2020).

| Intransitive verb classes grouped by number of features | Example sentence for DO-clefts per verb class and its English translation |

|---|---|

| WORK [volition, sentience, motion] | Was viele Bergbauarbeiter taten, war zu arbeiten. ‘What many mine workers did was work.’ |

| FEAR [sentience] | Was viele Angehörige taten, war zu bangen. ‘What many relatives did was fear.’ |

| SWEAT [motion] | Was viele Passagiere taten, war zu schwitzen. ‘What many passengers did was sweat.’ |

| GLITTER [∅] | Was viele Säuglinge taten, war zu glänzen. ‘What many infants did was glisten.’ |

The participants in the experiment on DO-clefts with transitive verbs were 60 native speakers of German, all naïve to the purpose of the study. They rated sentences including DO-clefts with transitive verbs for acceptability on a 6-point scale, ranging from very acceptable to very unacceptable (Kretzschmar et al. 2019, their Experiment 1). Kretzschmar and Brilmayer (2020; their Experiment 2) used the same sentence context as given in Table 4 with four intransitive verb classes (see Table 2) and collected data from 50 further participants, with the task instruction and acceptability scale identical to Kretzschmar et al. (2019). Finally, in the experiment on active versus passive voice discussed further below, Kretzschmar et al. (2019, their Experiment 2) asked 69 participants to rate sentences with transitive verbs in either active or passive voice (see Table 6 below) for acceptability using the same scale as just described.

Results of the analysis of the 611 verbs used in 523 DO-clefts in our corpus.

| Verb classes grouped by number of features | Corpus example | Number of verb constructions | Verb classes in the experiments |

|---|---|---|---|

| [volition, sentience, motion] | Was wir als F.D.P.-Fraktion tun, ist, in die Zukunft zu schauen und Perspektiven aus unserer Sicht aufzuzeigen.a ‘What we, the Liberals’ parliamentary group, do is look into the future and identify options from our perspective.’ |

593 | WATCH, WORK |

| [motion] | Was Sie tun, ist, schlafzuwandeln in ein Desaster.b ‘What you do is sleepwalk into a disaster.’ |

11 | SWEAT |

| [volition]c | Was Sie tun, ist, genau diese Zahlen zu ignorieren.d ‘What you do is ignore exactly those numbers.’ |

4 | – |

| [causation] | Das Einzige, was der Finanzmarkt tut, ist, diese Erwartung sichtbarer zu machen.e ‘The only thing that the financial market does is make this expectation more visible.’ |

1 | – |

| [sentience] | Das einzige, was die Kunden tun, ist sich über den Vorschlag zu ärgern.f ‘The only thing that the clients do is get annoyed about the proposal.’ |

2 | SEE, HATE, KNOW, FEAR |

| [∅] | – | 0 | EXHIBIT, GLITTER |

-

aSource: PRP/W13.00116 Protokoll der Sitzung des Parlaments Landtag Rheinland-Pfalz am 13.09.2000. 116. Sitzung der 13. Wahlperiode 1996–2001. Plenarprotokoll, Mainz am Rhein, 2000. Note that FDP is the official name of the German Liberal Party (Free Democratic Party). bSource: U16/JUL.00740 Süddeutsche Zeitung, 06.07.2016, S. 7; Ratlos in Straßburg. Note that the capitalized 3rd person pronoun in the corpus example is the honorific form for the addressee (2nd person) in German. cVolition entails sentience (cf. Dowty 1991: 607), i.e. a mental representation of the intended situation. Accordingly, there is no verb that implies volition but excludes sentience. This verb type was not tested in the above-mentioned experiments because the number of such verbs (e.g. ignore, refrain from) is too small to fulfill methodological adequateness criteria. dSource: PTH/W05.00009 Protokoll der Sitzung des Parlaments Thüringer Landtag am 28.01.2010. 9. Sitzung der 5. Wahlperiode 2009-. Plenarprotokoll, Erfurt, 2010. eSource: PRF08/JUL.00146 profil, 14.07.2008, S. 48; “Ich habe keine Zauberbox”. fSource: NON07/MAR.07821 Niederösterreichische Nachrichten, 14.03.2007, S. 3; Urlaub steht über dem Klimaschutz.

Regarding the acceptability of DO-clefts, the ratings for transitive and intransitive verb classes showed comparable agentivity clines, as summarized in (2) below. The notation of clines in (2) incorporates statistically significant and non-significant effects, with a > b meaning that ‘a is rated significantly better than b’ and a = b meaning that there was ‘no statistically significant difference in acceptability ratings between a and b’. The clines for DO-clefts with transitive and intransitive verbs show that verb classes with a higher number of agentive features were rated significantly better than verb classes with a lower number of agentive features. This pattern held for contrasts of verb classes with three versus one agentive feature and for contrasts of verb classes with one versus none of the tested agentive features. The experiment for intransitive verbs demonstrates that for one-feature verbs the type of agentive feature, i.e. motion versus sentience, is also irrelevant.

| Acceptability clines for transitive verbs (a) and intransitive verbs (b) in DO-clefts (Kretzschmar and Brilmayer 2020; Kretzschmar et al. 2019) | |||||

| a. | WATCH | > | SEE = HATE = KNOW | > | EXHIBIT |

| [volition & | [sentience] | [ø] | |||

| motion & | |||||

| sentience] | |||||

| b. | WORK | > | FEAR = SWEAT | > | GLITTER |

| [volition & | [sentience or motion] | [ø] | |||

| motion & | |||||

| sentience] | |||||

In summary, based on quantitative acceptability estimates, we find that the DO-cleft preferably combines with verbs that assign all three agentivity features under discussion to their subject argument and repels verbs with fewer agentivity features. To what extent this empirical observation can be generalized to apply to authentic natural language data will be examined in the following section.

2.2 The variable relevance of semantic role features in German: corpus data

The experiments described above tested DO-clefts under experimental conditions in language comprehension. The preference of DO-clefts to refer to actions performed by a volitional, sentient and motional agent, however, is also manifest in authentic natural language production. We assessed this by conducting a corpus study using the German Reference Corpus DeReKo (Institute for the German Language 2018). DeReKo is a monitor corpus and the largest corpus on written Standard German with approximately 42 billion words (as of 03.02.2018) and comprises many different text genres (e.g. newspapers, parliamentary debates and internet sources). Our search was confined to the W-archive (version DeReKo-2018-I with more than 8.6 billion words), which is the largest publicly available archive of DeReKo and includes the widest range of text genres. Using the Cosmas II query tool (http://www.ids-mannheim.de/cosmas2/uebersicht.html), we searched for the basic sequence of DO-clefts was x tut, ist (,) y ‘what x does is y’. This search sequence began with was ‘what’ (including upper and lower case) and was followed by a span of up to four words to capture longer subject phrases before tun ‘do’. We searched for all inflectional word forms of tun ‘do’ and the copula sein ‘be’. For each lexical search item (was ‘what’, tun ‘do’ and sein ‘be’), we specified search parameters in Cosmas II so as to only search for their correct spelling. Our search included sequences in which there either was a comma or no comma following the copula as the comma can be optionally placed, depending on the type of the clefted constituent (baer infinitives and DPs, for instance, are used without a comma). Accounting for this variability in the use of the comma enabled us to consider hits in which other punctuation characters are used with the DO-cleft (cf. our discussion of the colon in Section 3.3).

This search resulted in 4,908 hits, many of which, however, did not match the DO-cleft structure we were interested in, i.e. they did not include a clefted infinitival verb. In a next step, we further manually annotated all hits for whether they matched the DO-cleft structure with a clefted VP constituent (see (9) below for further description) or some other type of clefted constituent such as a DP. We found 523 matches with a VP complement, which is a larger sample than what has been previously analyzed for German WH-clefts with clefted infinitival verbs in general (cf. Gast and Wiechmann 2012). Our sample of 523 DO-clefts contains 611 verbs in the clefted constituent. The higher number of verbs is explicable by verb coordination within the cleft, as shown in the first example in Table 5 below. We only took into account DO-clefts with a clefted infinitival verb. The verbs were then annotated for verb classes based on the classification of agentive features originally proposed by Dowty (1991; see above).

Overview of the verb class-by-construction design, including an example sentence for each construction.

| Construction | Example sentence and English translation |

|---|---|

| a. Active voice (only with transitives) | Dass manche die Mondlandung angeschaut haben, erfreute Max. ‘That some have watched the moon landing pleased Max.’ |

| b. Passive voice (only with transitives) | Dass die Mondlandung angeschaut wurde, erfreute Max. ‘That the moon landing was watched pleased Max.’ |

| c. DO-cleft (with transitives) | Was die Schaulustige tat, war die Mondlandung anzuschauen. ‘What the spectator did was watch the moon landing.’ |

| d. DO-cleft (with intransitives) | Was viele Bergbauarbeiter taten, war zu arbeiten. ‘What many mine workers did was work.’ |

Before reporting the results, a brief note on our method of analyzing verb meanings is in order. In Dowty’s (1991) approach, an agentivity feature is treated as an entailment of a verb with respect to one of its arguments. Strictly speaking, however, semantic role feature entailments depend on the whole construction of which a verb lexeme forms a part. Thus, for example, the verbs sweat and see refer to a non-volitional situation in most contexts of use. However, with certain argument types (see whether) or modal verbs (want to), volition is entailed, e.g. Go out and see whether it’s raining! We want to go and sweat in the sauna. Our corpus analysis therefore considered the entailments generated by the whole construction of which the verb forms a part.[3] Table 5 summarizes the results of the corpus study (see Supplementary Materials for further details: https://osf.io/dfhtg/?view_only=48214b2e26a744839f465fdf6abe7a61).

As shown in Table 5, the vast majority of the verb constructions used in the DO-clefts of our corpus entail all three agentivity features under discussion (volition, sentience and motion) for their implicit subject argument, which is always overtly realized as the subject of DO. This type of verb construction is analogous to the WORK and WATCH classes, which, in the above-mentioned experiments (Section 2.1), obtained the best acceptability ratings. In some cases, the active involvement of the participant, i.e. motion, refers to a course of action that is not specific to the verb lexeme but is nevertheless mandatory. Cf. diesen Prozess […] zu erleichtern ‘to facilitate this process’ in (3).

| Was wir auf Landesebene tun können und müssen, ist, diesen Prozess durch entsprechende Rahmenbedingungen zu begleiten und zu erleichtern. Es geht vor allem darum, Ressourcen zu mobilisieren. [4] |

| ‘What we can and must do at the federal state level is accompany and facilitate this process with appropriate underlying conditions. It is above all about mobilizing resources.’ |

One cannot facilitate a process without taking some course of action that may count as facilitation. In (3), Ressourcen zu mobilisieren ‘to mobilize resources’ explicitly refers to such a course of action.

Verb constructions entailing a smaller number of agentivity features are used far more rarely in DO-clefts in our corpus, as shown in Table 5. They were also rated less acceptable in the above-mentioned experiments (Section 2.1). We have found no verb construction that implies neither volition, nor sentience, nor movement for its subject argument (comparable to GLITTER or EXHIBIT in the experiments described in Section 2.1). Finally, we tested whether the probability of occurrence of verbs with three agentivity features differs significantly from the probability of occurrence of verbs with only one agentivity feature (collapsed across the kind of feature). A chi-squared test (performed in R v3.5.1 using the function chisq.test()) revealed that there is indeed a significant difference (χ2(1) = 541.12, p < 0.001). Hence, verbs with three agentivity features have a higher probability to occur in the DO-cleft than verbs with one feature compared to what would be expected purely by chance.

To summarize the argument so far, in the empirical investigations presented above, the clefted verb phrase in a DO-cleft preferentially refers to actions performed by a volitional, sentient, and motional agent. This preference is clearly manifest in both natural language production and under experimental conditions in language comprehension. Events entailing a smaller number of agentive properties also occur in our corpus and they are also judged as acceptable in the above-mentioned experiments but are much less frequent and less strongly acceptable. Events entailing none of the agentive properties under discussion do not occur and are hardly acceptable.

2.3 The correlation of high agentivity and DO-clefts cannot simply be attributed to the meaning of tun ‘do’

A possible explanation of the patterns reported in Sections 2.1 and 2.2 is that the strong tendency of DO-clefts to combine with actions performed by volitional, sentient and motional agents could simply be related to the lexical meaning of the verb tun ‘do’. If this were the correct explanation, one would predict to find the exact same acceptability cline reported for DO-clefts in (2) with other, non-clefted constructions where tun occurs. In order to investigate this possibility, we conducted an acceptability-rating study that paralleled the study of Kretzschmar et al. (2019) for DO-clefts with transitive verbs as closely as possible (see Supplementary Materials for details: https://osf.io/dfhtg/?view_only=48214b2e26a744839f465fdf6abe7a61). We took the sentence stimuli from each of the verb classes (WATCH, SEE, HATE, KNOW and EXHIBIT) and transformed them so that tun anaphorically referred to the critical verb that was included in a short question. Noun phrases were retained. Example items are presented in (4a)–(4e):

| Example items for anaphoric tun ‘do’ in a non-clefted structure in German | |

| a. | Betrachtete der Notar die Verfassungsurkunde? Ja, das tat er. |

| ‘Did the notary look at the constitutional charter? Yes, he did.’ | |

| b. | Hörte die Wanderin das Jagdhorn? Ja, das tat sie. |

| ‘Did the walker hear the hunting horn? Yes, she did.’ | |

| c. | Hasste die Witwe das Alleinsein? Ja, das tat sie. |

| ‘Did the widow hate being alone? Yes, she did.’ | |

| d. | Kannte der Autofahrer das Unfallrisiko? Ja, das tat er. |

| ‘Did the car driver know the accident risk? Yes, he did.’ | |

| e. | Wies die Neugeborene das Asperger-Syndrom auf? Ja, das tat sie. |

| ‘Did the newborn exhibit Asperger’s syndrome? Yes, she did.’ | |

We analyzed data from 59 native speakers of German who rated these question-answer pairs for acceptability on a 6-point rating scale, with 6 = very acceptable and 1 = very unacceptable (see Supplementary Materials for further details on methods and statistical modeling: https://osf.io/dfhtg/?view_only=48214b2e26a744839f465fdf6abe7a61). The statistically significant acceptability cline is given in (5). Recall that a > b means ‘a is rated significantly better than b’ and a = b means ‘no statistically significant difference in acceptability ratings between a and b’.

| Acceptability cline for anaphoric tun ‘do’ in a non-clefted structure, with mean ratings below each verb class | ||||||||

| WATCH | = | SEE | = | HATE | > | KNOW | > | EXHIBIT |

| 5.47 | 5.34 | 5.42 | 4.94 | 2.91 | ||||

Recall that the acceptability cline for DO-clefts with transitive verbs (see [2a] above) is WATCH > SEE = HATE = KNOW > EXHIBIT. Given the results in (5) and a descriptive comparison with the cline in (2a), the strong preference for volitional agents in DO-clefts cannot be explained by the meaning of tun alone.

2.4 Summary of the empirical evidence for the variable relevance of agentivity features across different constructions

Returning to our main concern, i.e. to provide evidence for the claim that the relevance of agentivity features changes across different syntactic constructions, Table 6 provides an overview of the German constructions that have been tested with the same set of verb classes and the same set of experimental procedures: active and passive voice with transitive verbs, and DO-clefts with both transitive and intransitive verbs.

Table 7 shows the clines that were found in these experiments. Recall that a > b means that ‘a received statistically better ratings than b’, while a = b means that there was ‘no statistically significant difference in acceptability ratings between a and b.

Overview of the acceptability clines per construction and verb class.

| Construction | Acceptability clines |

|---|---|

| a. Active voicea | WATCH = SEE = HATE = KNOW > EXHIBIT |

| b. Passive voicea | WATCH = SEE = HATE > KNOW > EXHIBIT |

| c. DO-cleft transa | WATCH > SEE = HATE = KNOW > EXHIBIT |

| d. DO-cleft intransb | WORK > FEAR = SWEAT > GLITTER |

-

aData source is Kretzschmar et al. (2019), bData source is Kretzschmar and Brilmayer (2020).

The clines in Table 7 clearly show that the role features that a verb entails for its argument(s) are associated with different degrees of relevance depending on the construction in which a verb occurs. This finding immediately raises the question as to why this is the case. As entailments of the verb meaning, one would expect role features to be present and relevant whenever a particular verb is used. One would not want to claim that beobachten ‘observe’ entails volition, sentience and motion only when used in a DO-cleft but not when occurring in a basic transitive active construction. In order to answer this question, we need to identify the basic organizing principle underlying the different clines. Kretzschmar et al.’s (2019) proposal is that this principle is provided by the notion of prominence.

2.5 Prominence as an organizing principle for linguistic structures

Prominence is often used in a pre-theoretical sense in linguistics, based on the assumption that its meaning is self-evident. Following Kretzschmar et al. (2019), we rely here on the more precise definition of prominence proposed by Himmelmann and Primus (2015). Importantly, this definition can be applied to different levels of linguistic structure, including the prosodic, morphosyntactic, semantic and discourse levels. In the following paragraphs, we briefly summarize this definition and show how it applies to semantic role prominence.

Himmelmann and Primus (2015: 40–45) propose three criteria for linguistic prominence. The first criterion is given in (6).

| Prominence is a relation that singles out one element from a set of elements of equal type and structure. |

Prominence relations establish a ranking among the members of a set of units of equal type. In our case, the semantic role features entailed by a verb for one of its arguments are of equal type. One particular role feature or set of role features is singled out to receive the status as the currently most prominent one. Thus, for example, in the case of DO-clefts in German, the feature sets constituted by volition, sentience and motion is singled out vis-à-vis the feature set containing only sentience or only motion. Given the variable relevance of role feature sets documented in Sections 2.1 and 2.2, it follows that the prominence relations between them are not given in advance, a point we will return to shortly.

The second criterion for linguistic prominence is given in (7):

| Prominent elements are structural attractors, i.e. they serve as anchors for the larger structures of which they are constituents and license more operations than their competitors. |

Thus, for example, the role prominence of agents licenses their use as subjects in active constructions. Semantically and syntactically prominent arguments such as agentive subjects furthermore tend to be ordered first, before other verbal arguments and adjuncts. Depending on the language, they may exhibit further properties that set them apart from other verbal arguments such as the ability to control the subject slot of a non-finite construction and so on. The distribution of these properties is best analyzed in terms of agentivity features because any one of them may not hold for all agentive subjects but only for those that accumulate a specific set of agentive features, e.g. volition, sentience and motion. Dowty’s (1991) subject selection principle and the role licensing condition for DO-clefts are pertinent examples.

Turning to the third criterion for linguistic prominence, it should be noted first that Dowty (1991) briefly considered a prioritization of role features. For example, he mentions in passing that “causation has priority over movement for distinguishing agents from patients” (1991: 574). However, Dowty’s feature prioritization is fixed: it is meant to hold for all constructions and languages based on the assumption that not only the role features themselves but also their prominence ranking is part of the semantics of the verbs. Given the evidence for the variable relevance of semantic role features briefly summarized above, it is clear that in our view, more flexibility is necessary in this regard. Specifically, we propose that the relative prominence of semantic role features is variable in the same way as the prominence status of other entities, as stated in Himmelmann and Primus’ third criterion:

| The prominence status of an entity shifts as discourse unfolds in time. |

This criterion ties prominence closely to the dynamicity of discourse. The prominence status of an entity is continuously updated when speakers engage in producing coherent discourse. The classic and most straightforward example is the prominence status of discourse referents: at any one time, there is exactly one referent that is the most prominent referent in the universe of discourse, but this status typically shifts among several referents co-present in the universe of discourse at a given time. Regarding semantic role features, the set of agentive features that is most prominent in DO-clefts is not the most prominent in the basic active or the passive constructions (see Table 7) because the discourse constraints on these constructions differ. This continuous update sets prominence asymmetries apart from other, not dynamically updated, asymmetries such as markedness and prototypicality.

Given these definitions, the changing relevance of semantic role features documented in this section would appear to be an example of linguistic prominence relations par excellence. Note that the continuous update of prominence relations in ongoing discourse is not invoked here specifically to explain the fact that the same verbs are associated with different agentivity clines when occurring in different constructions. Rather, the continuous update of prominence relations is considered here a necessary feature of all prominence relations, regardless of the structural level to which they apply. Note further that as stated in (8), the continuous update of prominence relations is not necessarily linked per se to prominence relations that hold on the discourse level (e.g. the currently most prominent referent in the universe of discourse). Rather, it is an additional hypothesis to assume that all linguistic prominence relations are motivated by discourse needs and thus support the management of prominence relations on the discourse level. It is the plausibility and feasibility of this additional hypothesis that we investigate in this article.

With regard to the phenomenon of variable agentivity clines, this hypothesis implies that it is possible to link the variable relevance of semantic role features to specific discourse conditions, which in turn requires a reliable and adequate analysis of these discourse conditions. As already noted in the introduction, specifying the discourse conditions is easier for some constructions than for others. Imperatives or passives, for example, have a long history of investigations into their discourse conditions on which one can draw. The discourse conditions on DO-clefts, on the other hand, are much less well understood and thus provide a particularly challenging test case for our overall argument.

3 Discourse conditions on DO-clefts

This section provides a brief review of the literature on the discourse conditions on DO-clefts – as a subtype of WH-clefts – and then explores the question as to whether and to what extent these have a role to play in prominence management in discourse. To the best of our knowledge, no previous work specifically deals with the discourse conditions on DO-clefts. We therefore very briefly summarize what is known about WH-clefts more generally and then specifically investigate DO-clefts.

Past research can be classified according to the main type of discourse conditions that it assumes to apply to WH-clefts. Most accounts focus on information structure in terms of given/new and topic/comment, oppositions that allow for a number of different interpretations that we clarify in Section 3.2. As further explained in 3.2, we distinguish here between sentence topics, discourse topics and thematic topics (or themes). In Section 3.3, we provide evidence for a constraint that specifically holds for DO-clefts, i.e. that the subject of a DO-cleft has to be a sentence topic and usually is a discourse topic. Following Carlson (1983), Gast and Wiechmann (2012), and Gast and Levshina (2014), we then argue that the idea that the WH-clause of WH-clefts can be analyzed as a thematic topic can be made more precise by using the ‘Question Under Discussion’ (QUD) framework (Section 3.4). Finally, we make an original proposal for extending the latter view by incorporating discourse prominence into the QUD framework as an additional organizing principle (Section 3.5).

It is not our goal here to present a comprehensive overview of past approaches to the analysis of discourse conditions on WH-clefts. Rather, our brief overview focuses on the connection between the information-structural and the discourse properties of DO-clefts. The question of a possible link between these properties of DO-clefts and the construction-dependent agentivity cline, as given in (2) above, is taken up again in Section 4. Before discussing the discourse conditions on WH-clefts, which are also known as ‘pseudo-clefts’, we introduce the terminology that we will be using in reference to the different subtypes of WH-clefts and their structure (Section 3.1).

3.1 A brief note on the structure of clefts

A simplified yet sufficiently explicit structural description of WH-clefts and the terminology used to describe them in this article are given in (9).

| | | Was ich auch noch gerne tue | | | ist | | | (zu) schwimmen |

| | | WH-clause | | | COPula | | | clefted constituent |

| ‘What I also like to do is (to) swim.’ | |||||

The literature has suggested different terms for the three parts of a WH-cleft as shown in (9), varying between purely descriptive and more theoretically motivated descriptions. Den Dikken (2006) uses precopula – copula – postcopula. while Prince (1978) describes the structure as wh-clause/presupposition – copula – focus. Hedberg (1990) and Weinert and Miller (1996) use cleft clause – copula – clefted constituent, and Collins (2006) speaks of relative clause – (be) – highlighted element. In (9) and in the following sections, we closely follow the terminology of Gast and Levshina (2014), W(H)-clause – COP – cleft constituent, as it is oriented towards the surface syntax and is transparent without further explanation.

Different subtypes of WH-clefts can be distinguished on the basis of the syntactic category of the clefted constituent. For the purposes of the present discussion, the three types of clefts given in (10)–(12) need to be distinguished.

| DP-cleft = clefted constituent is a DP as in |

| | Was ich vermisse | ist | mein Schlüssel . |

| ‘What I lack is my key.’ |

| DO-cleft = clefted constituent is a VP as in (9) above |

| HAPPEN-cleft = clefted constituent is a CP as in |

| | Was auch noch passiert ist | ist | dass mein Schlüssel weg ist . |

| ‘What also happened is that my key is gone.’ |

DO and HAPPEN are variables for the corresponding verbs in particular languages, for example tun ‘do’ and passieren ‘happen’ in German. They are also the defining constituents of the WH-clause in DO-clefts and HAPPEN-clefts, respectively. HAPPEN-clefts are a specific subtype of CP-clefts, i.e. clefts where the clefted constituent is a (finite) clause. DO- and HAPPEN-clefts are similar in that both refer to an event in the clefted constituent. The major difference between them, which is of central import for our discussion, is that in DO-clefts, the subject of the predicate in the clefted constituent is left unexpressed as it is co-referential with the overt subject of DO in the WH-clause.[5]

The syntactic category of the WH-clause is rarely explicitly addressed in the literature on this topic. The two main options that have been proposed are free relative clause (e.g. Altmann 2009; Carlson 1983) and indirect question (e.g. Faraci 1971). We do not take a position as to the syntactic nature of the WH-clause but we will argue below that it corresponds to an (implicit) question in the discourse structure.

For the following discussion, it is important to note that the literature mostly deals with WH-clefts in English (Biber et al. 1999; Collins 2006; Hedberg and Fadden 2007; Prince 1978). As Gast and Levshina (2014) make clear, there are already very significant differences between German and English with respect to the overall frequency and the motivation to use WH-clefts. It should therefore be clear that our analysis at this point specifically pertains to German DO-clefts.

3.2 Information-structural constraints on WH-clefts: different notions of topicality

In the literature, WH-clefts are often assumed to be constrained by information structure, which is characterized in terms of givenness/newness, theme/rheme, focus/background or topic/comment. In this short overview, we focus on givenness and topicality. Previous treatments have suffered from the well-known ambiguities associated with these terms, most importantly the ambiguities associated with different notions of topic and topicality. Therefore, we start with a brief characterization of three different notions of topic that in our view need to be clearly distinguished.

We make a distinction between i) (referential) sentence topics, ii) (referential) discourse topics, and iii) thematic topics or themes. The sentence topic is standardly defined as “the expression whose referent the sentence is about” (Reinhart 1981: 57). A discourse topic is a referent that is re-mentioned in several sentences and is an important referent during a particular span of a narration or conversational exchange. This notion is used in approaches that investigate topic continuity and topic shift (Givón 1983). Both of these notions are relevant for structuring a discourse in referential and topical chains. Often, discourse topics are also sentence topics, but this overlap is not necessary (for example, there can be two discourse topics in one sentence, only one of which can also be a sentence topic). The details of the interaction are quite complex. Centering Theory (e.g. Grosz et al. 1995; Joshi and Weinstein 1981) is one approach toward modeling the interaction.

The third notion of topic that is occasionally found in the literature is best conceived as the current theme to which the discourse contributes. We use the QUD framework as one way of making this notion more precise, as further discussed in Section 3.4. Finally, it should be noted that these different notions of topic and topicality are orthogonal to the information-structural bi-partition of the sentence into background (presupposition) and focus (assertion).

One of the most influential information-structural approaches to English WH-clefts is Prince (1978) who was primarily concerned with the question of how a WH-cleft has to be linked to the preceding discourse in order to be felicitous. Specifically, she proposed the following givenness condition (1978: 888): “A WH-cleft will not occur coherently in a discourse if the material inside the […] WH-clause” is not given, i.e. if it cannot be assumed to be “in the hearer’s consciousness at the time of hearing the utterance” (cf. Chafe 1974). In her central example, reproduced in (13), the WH-clause presupposes ‘John lost something’ and due to the close match between the notions of presupposition and givenness (Prince 1978: 887), presupposed material is also analyzed as given.

| What John lost was his keys. |

| (Prince 1978: 883) |

The piece of information may be given explicitly in the preceding context or it may be inferred or reconstructed from the linguistic context or from the situation (Prince 1978: 887–893).

Prince’s analysis has been taken up by many researchers and supplemented with additional aspects related to givenness (see also Biber et al. 1999; Collins 1991, 2006; Delin 1989; Gast and Wiechmann 2012; Hedberg and Fadden 2007). However, it has also been noted that an account in terms of givenness or inferability does not work for all WH-clefts. Importantly, Hedberg and Fadden (2007) observe that in examples like (14), a WH-clause need not be given or inferable, but that it is sufficient if the WH-clause qualifies as the ‘topic’ of the overall construction.

| What I think you have to appreciate about this program is that Pat does set the standard for civility. |

| (Hedberg and Fadden 2007: 61) |

In (14), the content of the WH-clause is indeed discourse new. Hedberg and Fadden explicate their topic notion in two ways. On the one hand, it seems to overlap with the background/focus distinction:

The initial element – the cleft clause [here: WH-clause] – in a WH-cleft always presents the topic of the sentence, and the clefted constituent always presents the focus, with the comment being the identification of the variable in the topic with the focus. (Hedberg and Fadden 2007: 50)

While the analysis of the WH-clause as background and the clefted constituent as focus is widely shared, the use of the topic terminology here is likely to create confusion. Here, we use background and focus to refer to the two parts of WH-clefts in terms of focus structure. Inside the background, there is a sentence topic (e.g. ich ‘I’ in Example [9] above), which is also the non-overt subject (PRO) of the clefted constituent in focus (e.g. schwimmen ‘swim’ in Example [9] above).

On the other hand, Hedberg and Fadden offer a modified characterization of their topic notion, i.e. the topic “must evoke a relevant question for the comment to make a contribution ‘about’” (2007: 50). This is similar to the notion of theme or thematic topic introduced above. We return to this characterization in Section 3.4, where we analyze the whole WH-clause as the thematic topic in the sense of the QUD or open question. Before this, we will now turn to an information-structural constraint that appears to be specific to DO-clefts.

3.3 A specific constraint on DO-clefts: subjects of DO-clefts are sentence (and discourse) topics

The argument developed so far holds for all kinds of WH-clefts: the content of the WH-clause is not restricted to given or inferable information but has to introduce a thematic topic to which the clefted constituent provides a comment. Regarding DO-clefts, this general condition can be further specified. The subject of the WH-clause of a DO-cleft must be a sentence topic and is usually also a discourse topic (i.e. has been mentioned before in the ongoing discourse). In order to support this claim, we constructed a subcorpus of 255 randomly selected DO-clefts from our larger corpus of 523 DO-clefts discussed in greater detail in Section 2. We analyzed (in)definiteness and givenness of the subject as indicators of topichood. In a first step, we extracted all personal pronouns such as I, he or we (193/255 = 75.69%) and definite noun phrases including proper names (49/255 = 19.22%), all of which can be classified as definite and given (adding up to 94.91%). A non-referential definite subject is absent in our subcorpus (e.g. The man Susan will marry has not been born yet).

In a second step, we analyzed the remaining indefinite subjects (e.g. bare plurals or indefinite pronouns): 13/255 = 5.09%. In the pertinent literature, indefinites are subclassified pairwise, inter alia, as follows: specific versus non-specific, existentially presupposed versus non-presupposed, generic versus existential, strong versus weak, referentially identifiable versus non-identifiable by the speaker.[6] Only the second element of each of the above pairs bars the respective noun phrase from topichood. In case of doubt, we used Reinhart’s (1981) paraphrase tests for sentence topichood. Consider, for example, the following non-specific indefinite in a typical context of use and in the underlined test construction for topichood: There is a fly in my soup. #As for a fly, it is in my soup. By contrast, the following specific indefinite passes a similar (underlined) test context: Students from our faculty skipped classes. √It was reported about students from our faculty that they skipped classes. With this method, we have found that the subject of DO is an obligatory sentence topic in DO-clefts in German. A corpus example with a generic indefinite noun phrase Künstler ‘artist’ is provided in (15).[7]

| Die Frau ist durch und durch Künstlerin und mag sich zur Politik gar nicht äußern. „Im Grunde ist das Problem so einfach, dass man es gar nicht erkennt. Es ist das Prinzip des Gebens. Was Künstler tun, ist, den Menschen etwas zu geben und sich ihnen dabei ganz zuzuwenden und zu öffnen. Wenn Politiker von so einem ähnlichen Prinzip angetrieben wären, würde es besser zugehen auf der Welt – im Idealfall.“ [8] |

| ‘The woman is an artist through and through and does not want to comment on politics at all. “Basically, the problem is so simple that one does not even notice it. It is the principle of giving. What artists do is give the people something and at the same time completely turn toward them and open up to them. If politicians were driven by a similar principle, the world would be better – ideally”.’ |

A chi-squared test confirmed that there is a significant difference in the probability of occurrence of definite (pronominal and definite NPs) versus indefinite subjects in the DO-cleft (χ2(1) = 205.65, p < 0.001). Table 8 compares the results of our corpus analysis for (in)definite subjects of DO-clefts with the results of a quantitative corpus study for the referential properties of subjects across constructions in German (Weber and Müller 2004).

Definite versus indefinite subjects in a subcorpus of DO-clefts and in Weber and Müller (2004).

| Definites incl. proper names & personal pronouns | Specific or generic indefinites | Non-specific indefinites or non-referential use | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Subject of DO in our study | 94.98% | 5.02% | – |

| Weber and Müller (2004) | 81.05% (SVO) | 18.95% (SVO) | |

| 86.70% (OVS) | 13.30% (OVS) | ||

Weber and Müller (2004) analyze a corpus of 625 sentences with subject-before-object (SVO) word order and 625 sentences with object-before-subject (OVS) word order for givenness and definiteness. Their results for definiteness (cf. their Table 2) clearly show that there are more indefinite subjects in both word order conditions than in our subcorpus of DO-clefts, where the word order is generally also SVO. Unfortunately, they do not distinguish between strong and weak indefinites. Hence it remains unclear to what extent weak indefinites, which we claim are not allowed in DO-clefts, occur in non-clefted sentences.

In conclusion, DO-clefts only allow for sentence topics as subjects in the WH-clause, which is necessarily identical to the (unexpressed) subject of the infinitive of the clefted constituent.

3.4 A new ‘Question Under Discussion’ account of DO-clefts

Very few analyses focus on the discourse function of WH-clefts in addition to investigating information-structural constraints, as done in the preceding sections. Weinert and Miller (1996: 173) are an exception in this regard. They observe that “WH-clefts are forward pointing and often introduce topics or mark an important starting point for the following discourse. IT-clefts are neutral with respect to forwards or backwards pointing.” In this section, we follow up on this observation and analyze the question raised by the WH-clause of a DO-cleft in the framework of the QUD discourse model (Büring 2003; Ginzburg 2012; Roberts 2012 [1996]; for an overview, cf. Onea 2016; Riester 2019; Velleman and Beaver 2016). The QUD discourse model has its predecessors in the dialog games of Carlson (1983) and the quaestio-approach of Klein and von Stutterheim (1987), von Stutterheim and Klein (1989) and van Kuppevelt (1995). One of the main motivations for QUD and the earlier approaches is that we should be able to derive the information structure of a particular sentence from its discourse structure (cf. Benz and Jasinskaja 2017). The main idea of QUD is that the declarative sentences in a discourse are answers to implicit questions, which are hierarchically structured. The goal of a discourse is to answer a very general question of the type What is the way things are?, which is then elaborated into a series of implicit sub-questions organized in stacks (Roberts 2012 [1996]) or in hierarchical trees or so-called D(iscourse)-trees (Büring 2003). The small discourse in (16) can be represented by the QUD or discourse tree in (17) with implicit sub-questions in curly brackets and the explicit assertions in bold.

| The music was great. The pasta was delicious. The pizza was not so good. |

| Discourse tree for (16) |

|

Note that implicit questions are different from explicit questions. The latter can change and update the discourse context with the material they contain. Implicit questions, however, do not update the discourse context. Rather, they motivate the particular information structure of the explicitly expressed assertions – as in the example above (cf. Riester 2019: 165 for discussion).

The connection between an implicit question and the overt assertion in the discourse tree is characterized by Roberts (2012 [1996]) as a ‘relevant discourse move’, as per (18):[9]

| A move m is relevant to the Question Under Discussion q […] if m either introduces a partial answer to q (m is an assertion) or is part of a strategy to answer q (m is a question). |

| (Roberts 2012 [1996]: 21) |

The concept of a relevant move to the superordinate QUD for a particular discourse segment helps to identify the utterances in a discourse that directly contribute to answering this QUD and thereby form the main structure of the discourse segment. Roberts assumes two ways of reacting to a question q: a partial/full answer or a subquestion showing a way in which the main question can be addressed. In (17), the assertion ‘The music was great’ is a full answer to the implicit question {How was the music?} and the assertion ‘The pasta was delicious’ is a partial answer to the question {How was the food?}. The subquestion {How was the pasta?} is a subquestion of the question {How was the food?}, which also counts as a relevant move in the discourse.

We can now implement the original observation by Carlson (1983: 225) that the WH-clause in a WH-cleft is associated with a question in the QUD model. Carlson notes that the WH-cleft in (19a) can be associated with the question-answer dialog in (19b, c), with the explicit question (19b) corresponding in form to the WH-clause in (19a). The answer to this explicit question is the clefted constituent his wallet (19c).

| a. | What David wants is his wallet. |

| b. | What does David want? |

| c. | his wallet |

Carlson’s insight can easily be implemented in a discourse tree, as in (20). The WH-clause is structurally identical to the implicit question (underlined). Additionally, the content of the WH-clause, i.e. the open proposition ‘David wants x’, corresponds to the content of the question ‘What does David want?’ (see Section 3.1). In a QUD approach,[10] the content of the WH-clause does not have to be previously mentioned. It is sufficient if it is thematically linked to the superordinate QUD and if, in this sense, it “arises naturally in th[e] context” (Carlson 1983: 226). Correspondingly, the clefted constituent is only acceptable as a relevant answer if it provides new information relative to the WH-clause. An indiscriminate, general ban on previously mentioned information, as in the approaches reviewed in Section 3.1 above, is not necessary and often inadequate (cf. (15) above). In sum, in a QUD approach, givenness and newness are always considered in connection with the discourse organization triggered by QUD-answer pairs.

|

DO-clefts have an additional restriction on the correspondence between the WH-clause and implicit question. The clefted constituent is a non-finite VP and the subject of the WH-clause must be identical to the subject of the clefted VP. In (21), for example, the DO-cleft Alles, was ich tue, ist, ihnen zuzuhören ‘All I do is listen to them’ includes ich ‘I’, which is also the subject of the infinitive ihnen zuzuhören ‘listen to them’. At the same time, it is also the sentence topic of the DO-cleft, since the implicit question is about this subject ich ‘I’, as we can see from the context in (21) and the corresponding discourse tree in (22).

| Denn Eduardo Sousa erklärt: “Ich füttere meine Gänse kaum. Sie fressen, was sie wollen und wie viel sie wollen. Sie leben frei. Alles, was ich tue, ist, ihnen zuzuhören. Dafür zu sorgen, dass sie haben, was sie brauchen.” [11] |

| ‘Because Eduardo Sousa explains: “I hardly feed my geese. They eat what they want and how much they want. They live free. All I do is listen to them. To make sure that they have what they need.”’ |

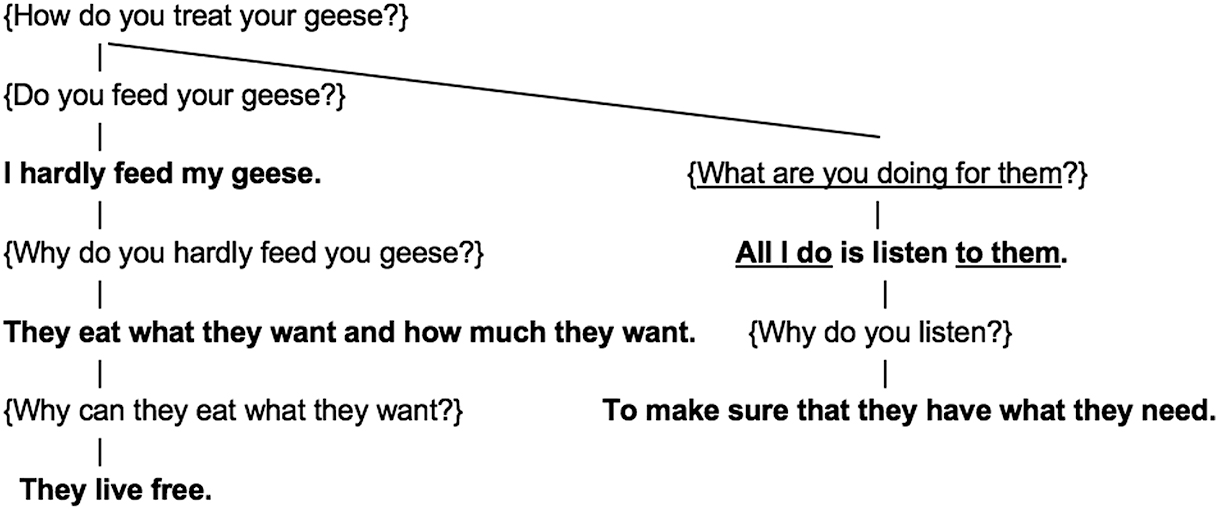

| Partial discourse tree for the DO-cleft in (21) |

|

We can now formulate the formal properties of a DO-cleft that license its use as a proper move in a discourse tree:

| Conditions on DO-clefts in discourse trees as relevant moves |

| A DO-cleft is a relevant move if: |

| (i) the DO-cleft is a full answer to an implicit question that can be recovered from the previous context; |

| (ii) the WH-clause corresponds to this implicit question; |

| (iii) the subject of DO in the WH-clause is co-referential with the subject of the clefted constituent that is left unexpressed; |

| (iv) the subject of the DO-cleft is also the sentence topic. |

In order to illustrate the function of DO-clefts in the organization of a discourse, we provide a preliminary analysis in the discourse tree in (24) that captures the entire discourse segment in (21). The discourse tree provides the implicit questions organizing the coherence of the assertions in the discourse. The main implicit question here is {How do you treat your geese?}. The discourse then develops into sub-questions about the treatment of the geese. We learn about how the speaker feeds the geese, etc. The DO-cleft All I do is listen to them brings us back to the main question of how he treats his geese. The DO-cleft raises a different subquestion of the main question, namely what (else) he is doing for the geese. The condition of the DO-cleft here is therefore that it connects to the main implicit question, fulfilling condition (23) for a relevant move.

| Extended discourse tree for (21) (preliminary version) |

|

To sum up the exposition so far, the QUD approach offers an explanation as to why the WH-clause denotes an open proposition and what the basic meaning contribution of the biclausal structure to the overall discourse organization is: the WH-clause corresponds to a (sub)QUD, and the whole WH-cleft corresponds to a response to that (sub)QUD. Moreover, the QUD notion opens the way toward a more appropriate and fine-grained analysis of the given-new constraint on WH-clefts. DO-clefts show an additional restriction in that their subject must be topical, i.e. it must be referential and familiar.

Still, the QUD approach in its current form cannot fully explain what is special about a WH-cleft in contrast to its non-clefted counterpart, which also has to answer an implicit QUD to function as a coherent contribution to a developing discourse. This characteristic property of WH-clefts has been informally characterized as follows: WH-clefts raise “a topical question worthy of interest” and provide a “main rheme” (Carlson 1983: 225). Other authors explicitly take “highlighting” as the special function of WH-clefts (Jones and Jones 1985: 3). Despite their intuitive appeal, such characterizations remain vague because they lack a coherent set of general criteria for the meaning of “worthy of interest”, “highlighting” or “attention-marking” when analyzing linguistic structures.

3.5 Extending the QUD framework by bringing in discourse prominence

In order to make more precise the highlighting property of WH-clefts mentioned in the quotes at the end of the preceding section, we again turn to the notion of prominence already introduced in Section 2 above and apply the three main criteria of prominence (Himmelmann and Primus 2015) to discourse organization with QUDs, along the lines suggested in von Heusinger and Schumacher (2019: 119).

At the discourse level, prominence relations apply to various kinds of entities, including, for example, discourse referents: at any given point in time in ongoing discourse, one of the discourse referents among the discourse referents available at this point in time is more prominent than the others. This prominence status licenses highly reduced anaphoric expressions (zero or an unstressed pronoun). Another example is (sentence) topics where prominence relations may arise whenever two or more topic chains run in parallel or cross each other.

Our proposal here is to also apply the notion of prominence to QUD structures, i.e. the QUD pairs consisting of the (usually implicit) question and its answer. Specifically, we propose that a WH-cleft construction makes explicit the question implicit in a QUD pair and thus renders this QUD pair more prominent than other QUD pairs available at a particular point in ongoing discourse, as stated in (25).

| A WH-cleft makes explicit the QUD-answer structure of a particular discourse contribution and highlights this QUD pair as prominent among other QUD pairs concurrently available in the ongoing discourse. |

We propose that together, (23) and (25) state the essential conditions for the felicitous use of a WH-cleft in discourse that have to be fulfilled necessarily, i.e. are part of the conventionalized utterance meaning of WH-clefts. By using a WH-cleft, the speaker automatically and necessarily makes explicit the QUD-answer structure of the respective utterance and highlights this QUD-answer pair as prominent among other relevant QUD-answer pairs.

In the following, we will provide some evidence for our claim that WH-clefts, including DO-clefts, establish prominence relations between QUD-answer pairs, using the three main criteria of linguistic prominence: a) singling out, b) attracting more operations and c) undergoing continuous update (cf. Section 2.5 above). Where possible, we will provide examples from our own corpus of DO-clefts. If not, we will review evidence from the literature on (WH-)clefts in general.

The prominence status of a QUD-answer pair singled out among other QUD-answer pairs is supported by a number of different prominence-lending properties. The most obvious prominence-lending property of a WH-cleft is the obligatory formal partitioning into a WH-clause and a clefted constituent. Clefting can be classified as a strategy of amplification and delay, which are more generally used attention-capturing devices (cf. Hopper 2001).

Another prominence-lending property that is connected to the strategy of delay in written discourse is the colon. It is used in 25 of the 523 DO-clefts (4.78%) in our corpus introduced in Section 2 above. This is a surprisingly high number given the fact that our corpus annotation excluded the colon before direct speech and before a list, which constitute its canonical contexts of use. The highlighting use is illustrated by the corpus examples in (26a)–(26c):

| The prominence-lending use of the colon in DO-clefts | |

| a. | Aber: Alles, was die drei tun, ist, für totale Verwirrung zu sorgen…[12] |

| ‘But: All those three do is cause total confusion…’ | |

| b. | Aber das Erste, was der rheinlandpfälzische Ministerpräsident tut, ist, eine Erfolgsstory zu predigen: Rheinland-Pfalz ist davongekommen.[13] |

| ‘But the first thing the Minister President of Rhineland-Palatinate does is preach a story of success: Rhineland-Palatinate got away.’ | |

| c. | Und was sie meistens tun, ist: tanzen.[14] |

| ‘And what they usually do is: dance.’ | |

Our analysis of the colon as a prominence-lending property in DO-clefts is based on its general function in written language. According to Bredel (2011: Ch. 7.4), the colon signals a bifurcation of the syntactic structure: the structure on the left side of the colon must be extended by the information on the right side. Hence, as in clefts, the information is delivered in two parts, very often in order to highlight or put emphasis on the material after the colon, as in The winner is: Mark Spencer!

In speech, prosody is a prominence-lending property. Previous research on the prosody of WH-clefts focused exclusively on intonational phrasing and pitch accents related to information structure (e.g. Gast and Levshina 2014; Gast and Wiechmann 2012; Hedberg and Fadden 2007; Prince 1978; Weinert 1995; Weinert and Miller 1996). However, increased loudness and deacceleration of speech tempo are closer to prosodic highlighting as a strategy of delay. In past research, there is only occasional mention of loudness as a prosodic trait of clefts. Consider David Crystal’s illuminating brief remarks about it-clefts such as It was Martha who…:

Cleft sentences are a very useful way of changing the emphasis in what you want to say or write. The part that comes to the front is the part that you really want to draw attention to. In speech it’s usually the loudest bit of the sentence.[15]

Prosodic loudness and deacceleration have been studied in greater detail in other types of data. Kohler and Niebuhr (2007) and Niebuhr (2010) studied these parameters in their project on emphasis, Braun (2019) used them in her study on verbal irony, and Braun and Schmiedel (2019) regarding word-play and jokes, just to name a few studies addressing the linguistic functions of loudness and deacceleration. What these diverse data domains have in common is that they involve a type of prosodic highlighting that is phonetically and functionally distinct from the type of prosodic prominence connected to information structure (cf. Kohler and Niebuhr 2007; Niebuhr 2010).

A further prominence-lending property, which is present in 48.37% of the DO-clefts in our corpus (253 DO-clefts out of 523), is the use of a pronominal or a superlative or ordinal type of adjective at the beginning of the WH-clause. It refers to the maximum value on a scale, e.g. das erste ‘the first’, das einzige ‘the only’, alles ‘all’ and das interessanteste ‘the most interesting’. One may argue that das erste ‘the first’ is used in a purely temporal meaning as in (26b) above. However, a WH-clause introduced by das erste is never followed by a discourse contribution introduced by das zweite ‘the second’ or das Weitere ‘the rest that follows’ in our corpus. This is indicative of highlighting as the main function of das erste ‘the first’ in such contexts.

Finally, another often attested prominence-lending element is aber ‘but’, as in the Examples (26a, 26b) above. Its adversative uses (i.e. ‘denial of expectation’, ‘contrast’, ‘correction’ and ‘cancellation’, cf. Blakemore 1989, 2002; Hall 2004) make it particularly suitable to lend additional prominence to DO-clefts in discourse.